Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Dough Obtaining

2.3. Extrusion Process

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization of Extruded Products

2.5. Second-Generation Snack Optimization

Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

Sensory Analysis

Bromatology Analysis

Ellagic Acid Content in the Final Product

3. Results

3.1. Regression Coefficients and ANOVA

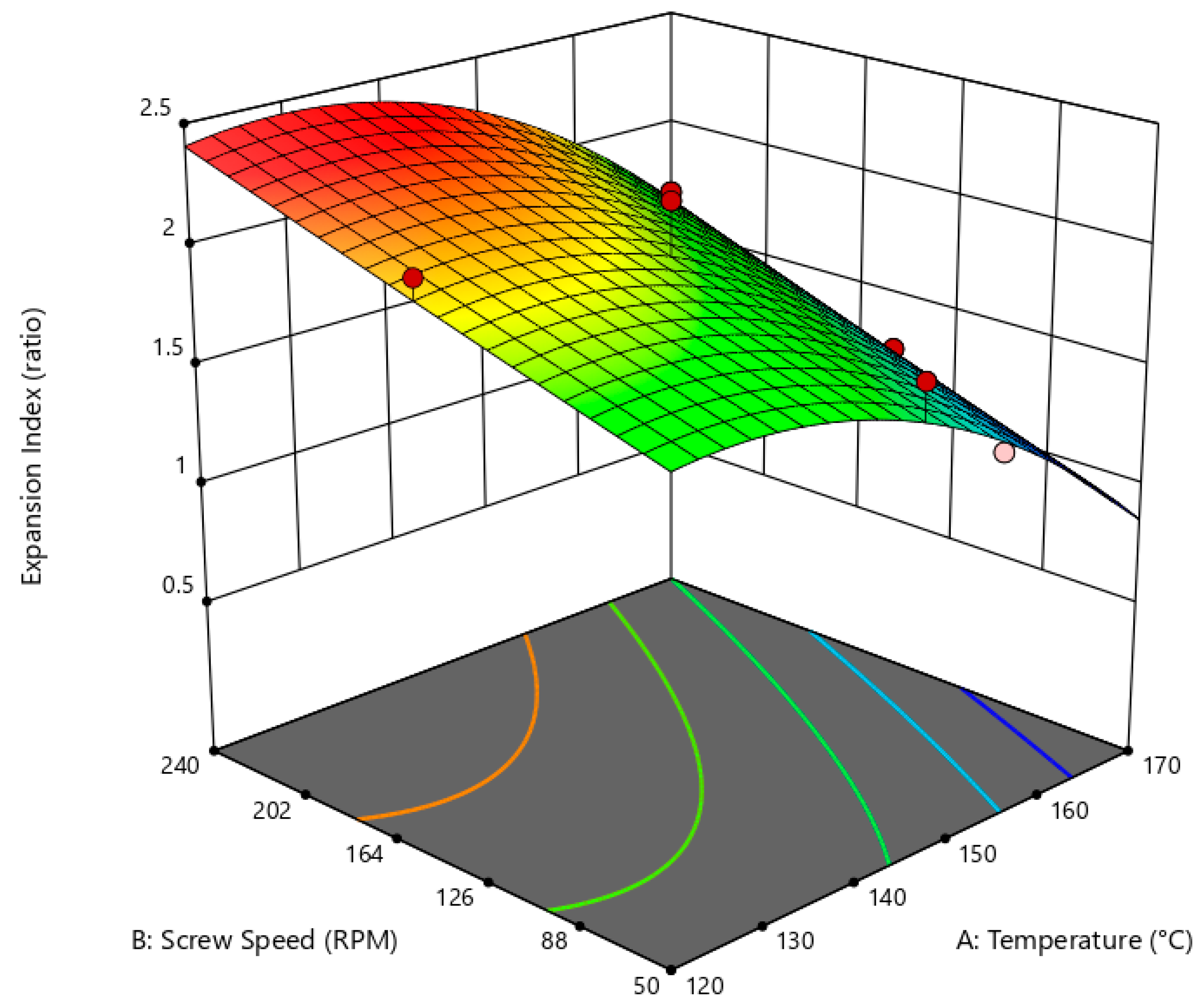

3.2. Expansion Index

3.3. Apparent Density

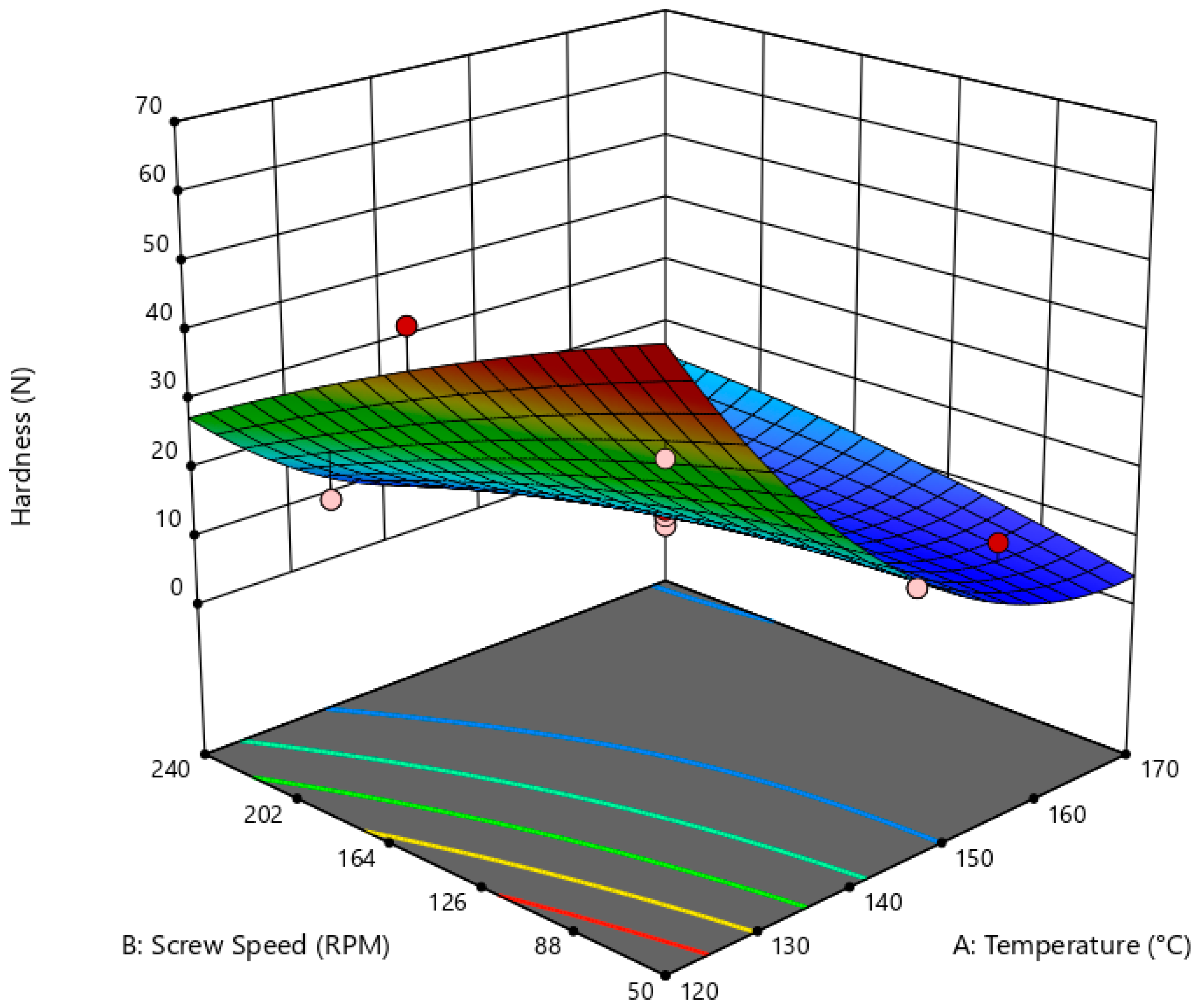

3.4. Penetration Force

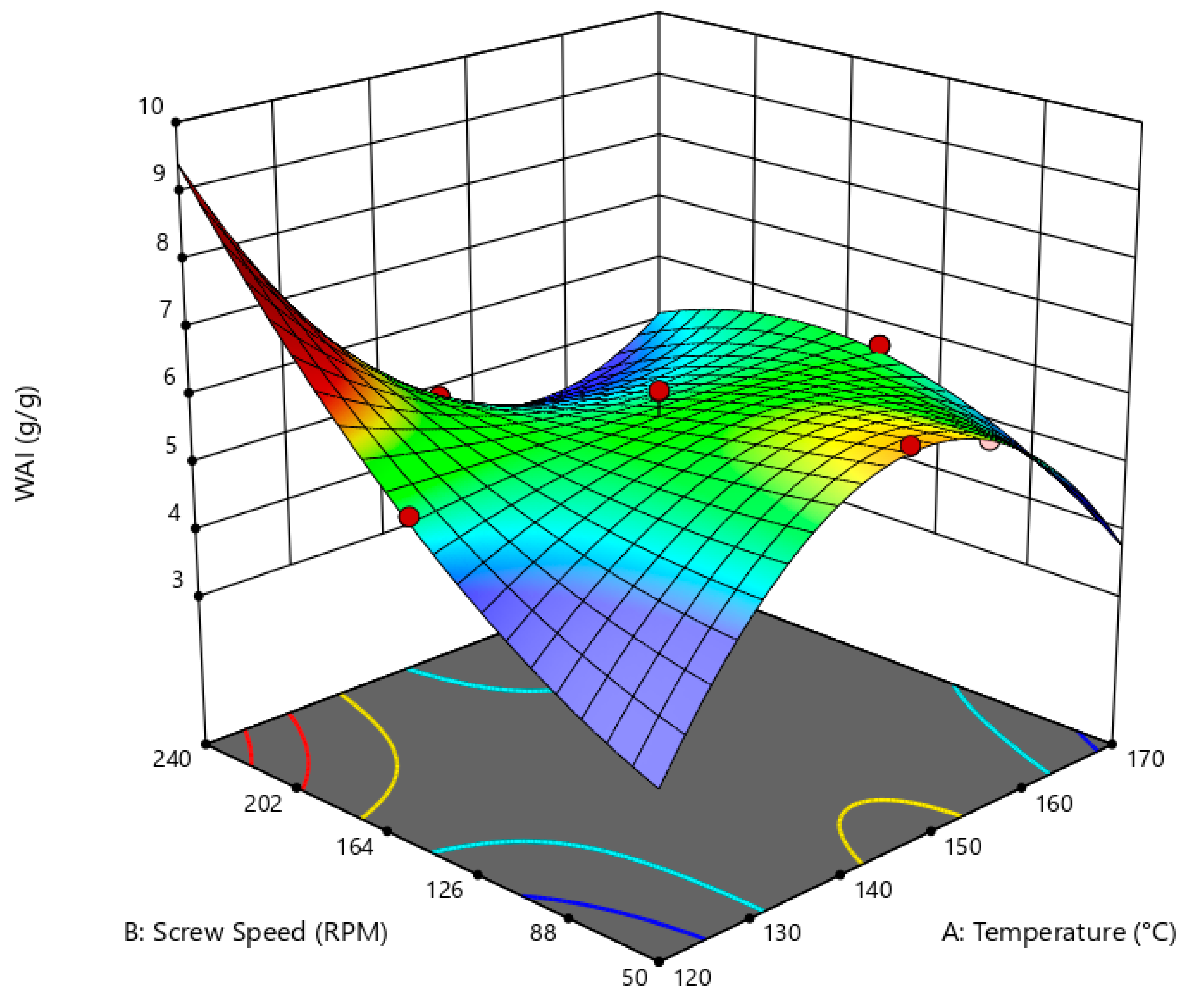

3.5. Water Absorption Index

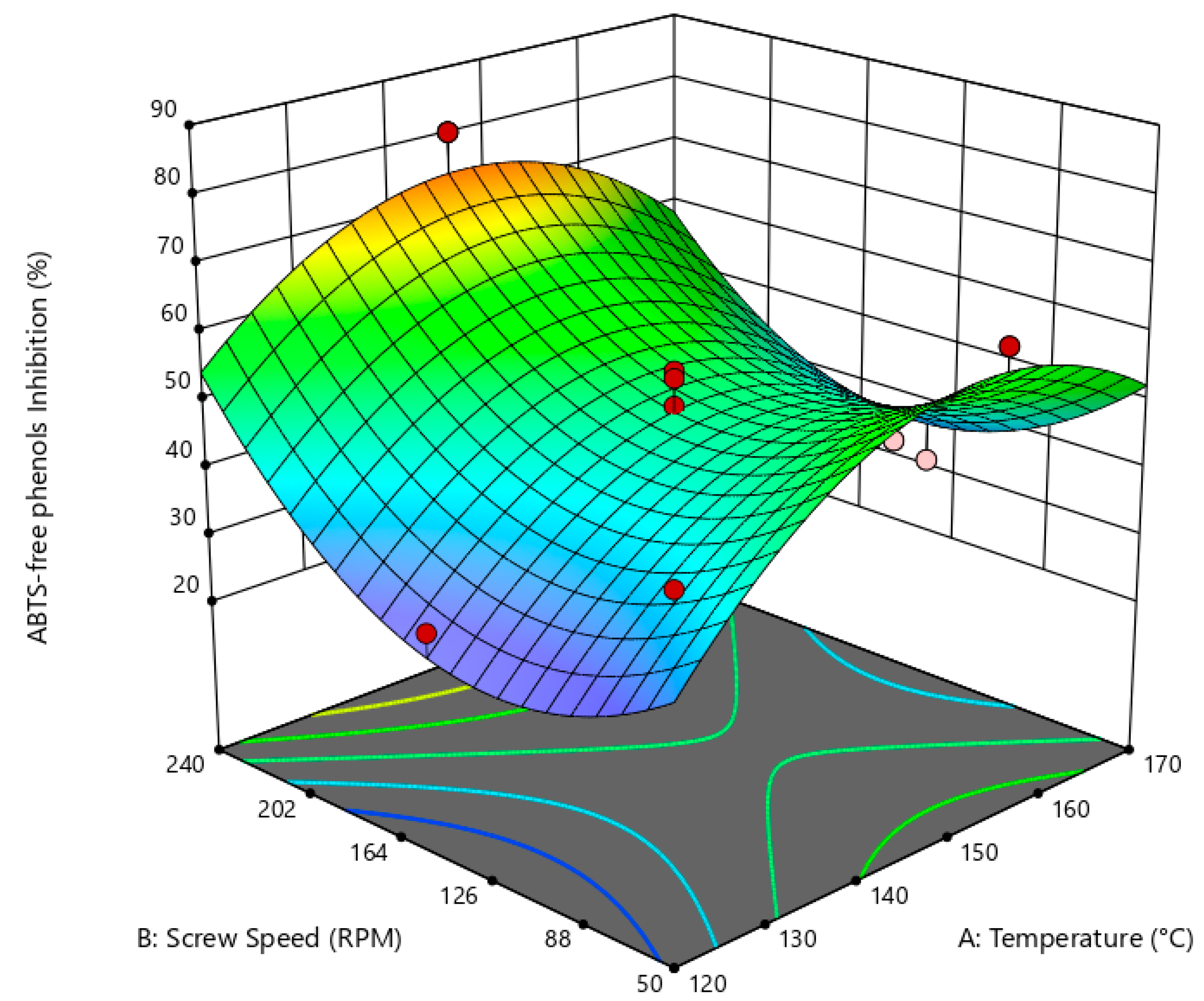

3.6. Free Phenols Inhibition of ABTS

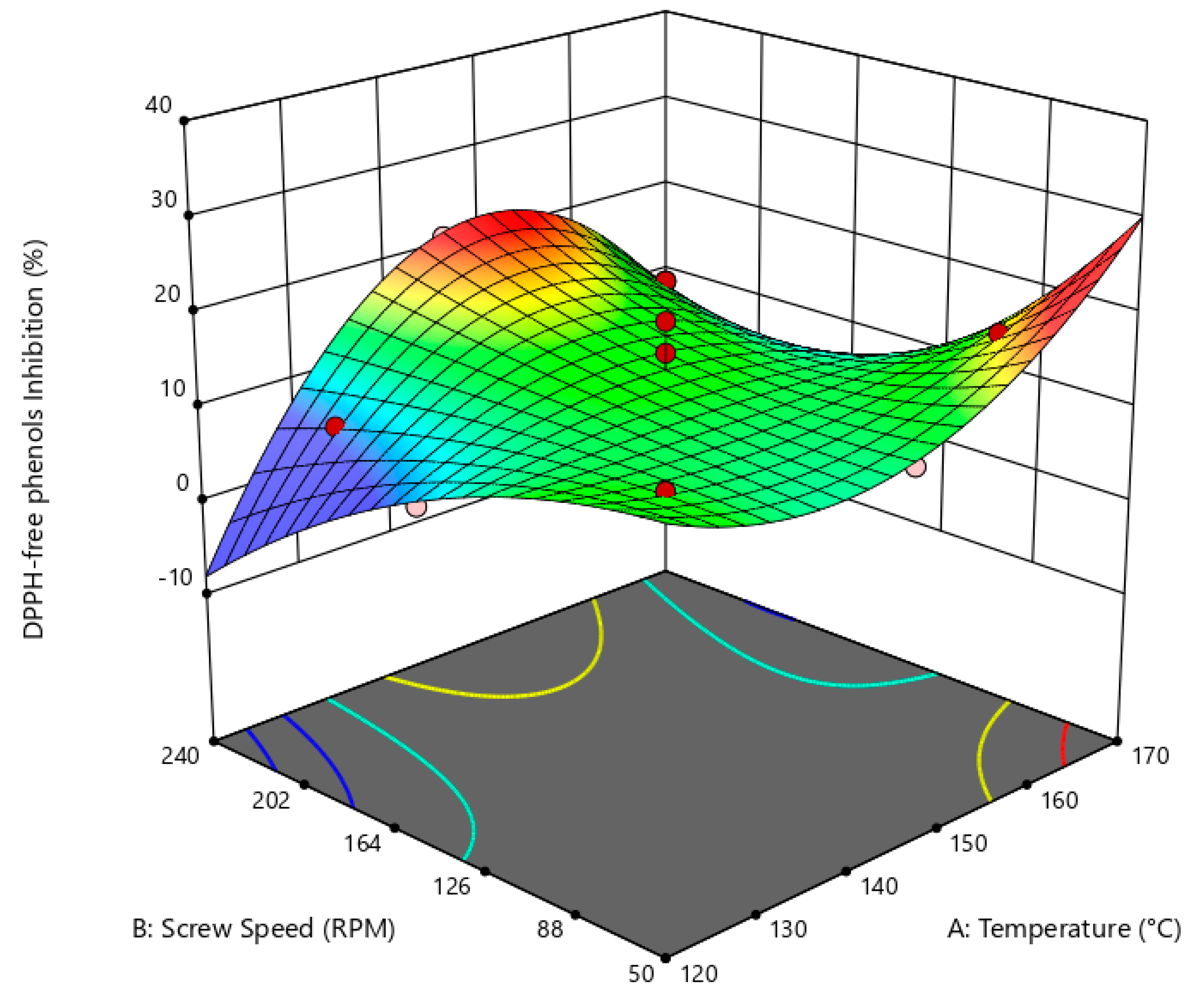

3.7. Free Phenols Inhibition of DPPH

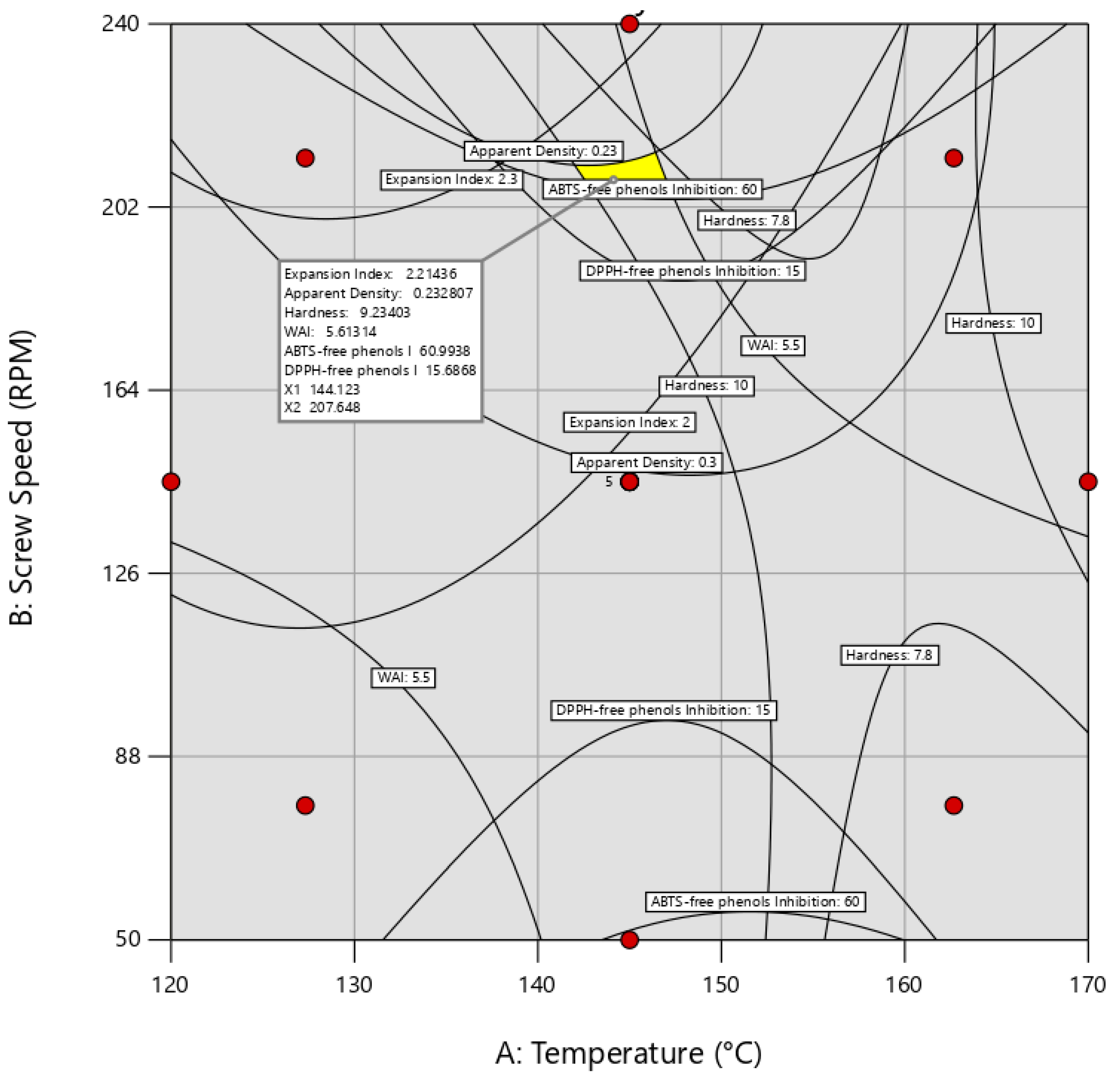

3.8. Optimum Design of Extruded Snacks

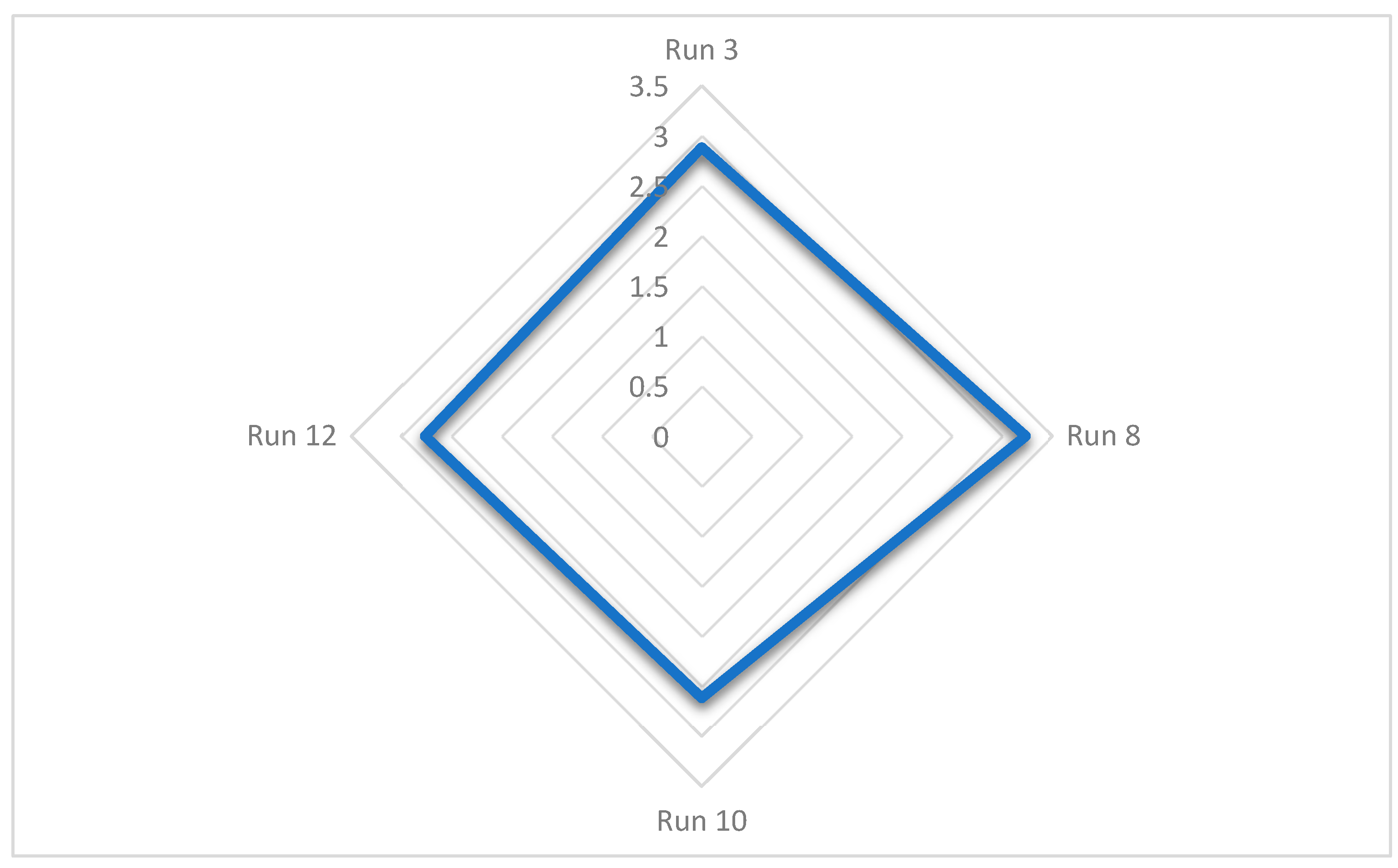

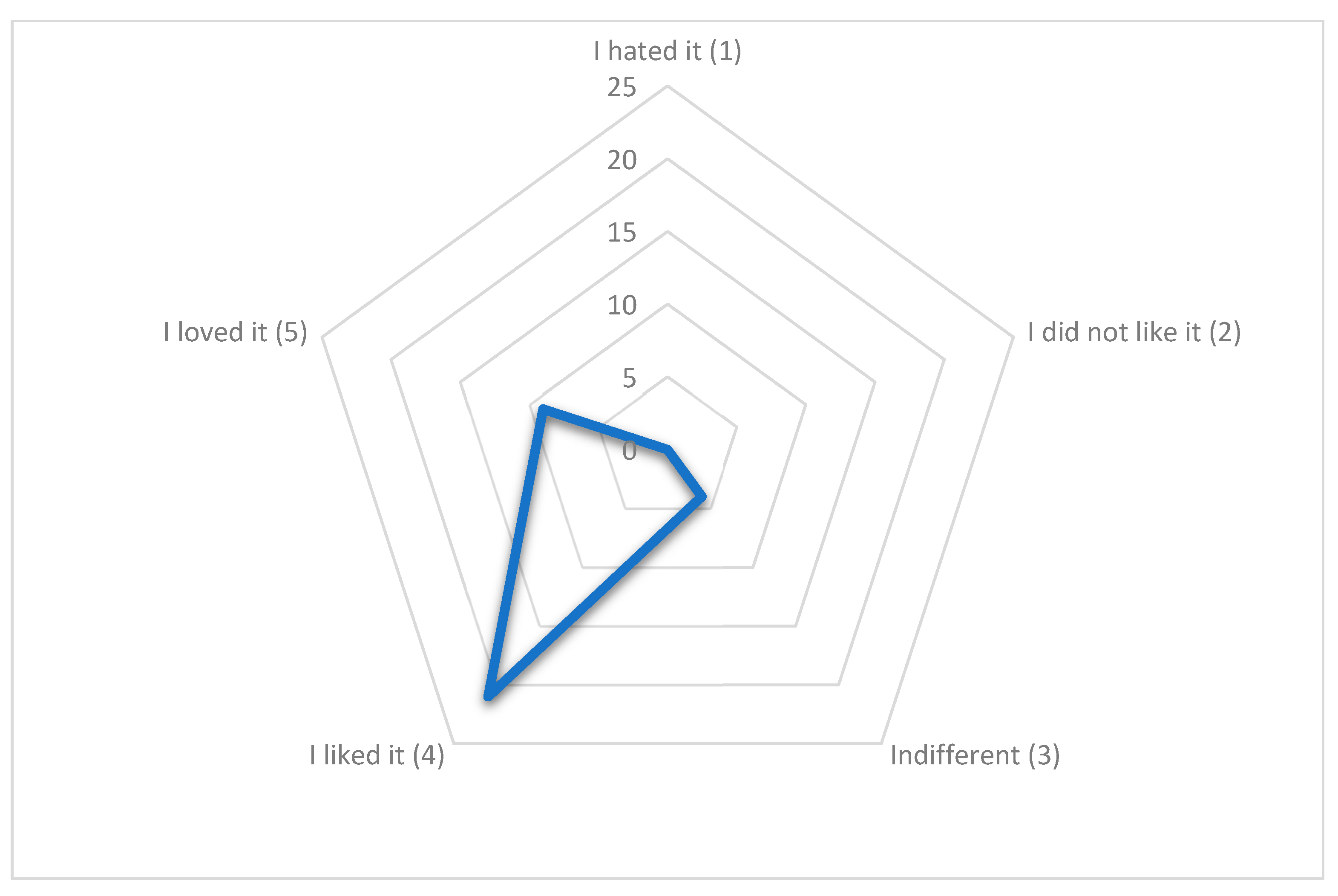

3.9. Sensory Analysis

3.10. Bromatological Characterization of Final Product

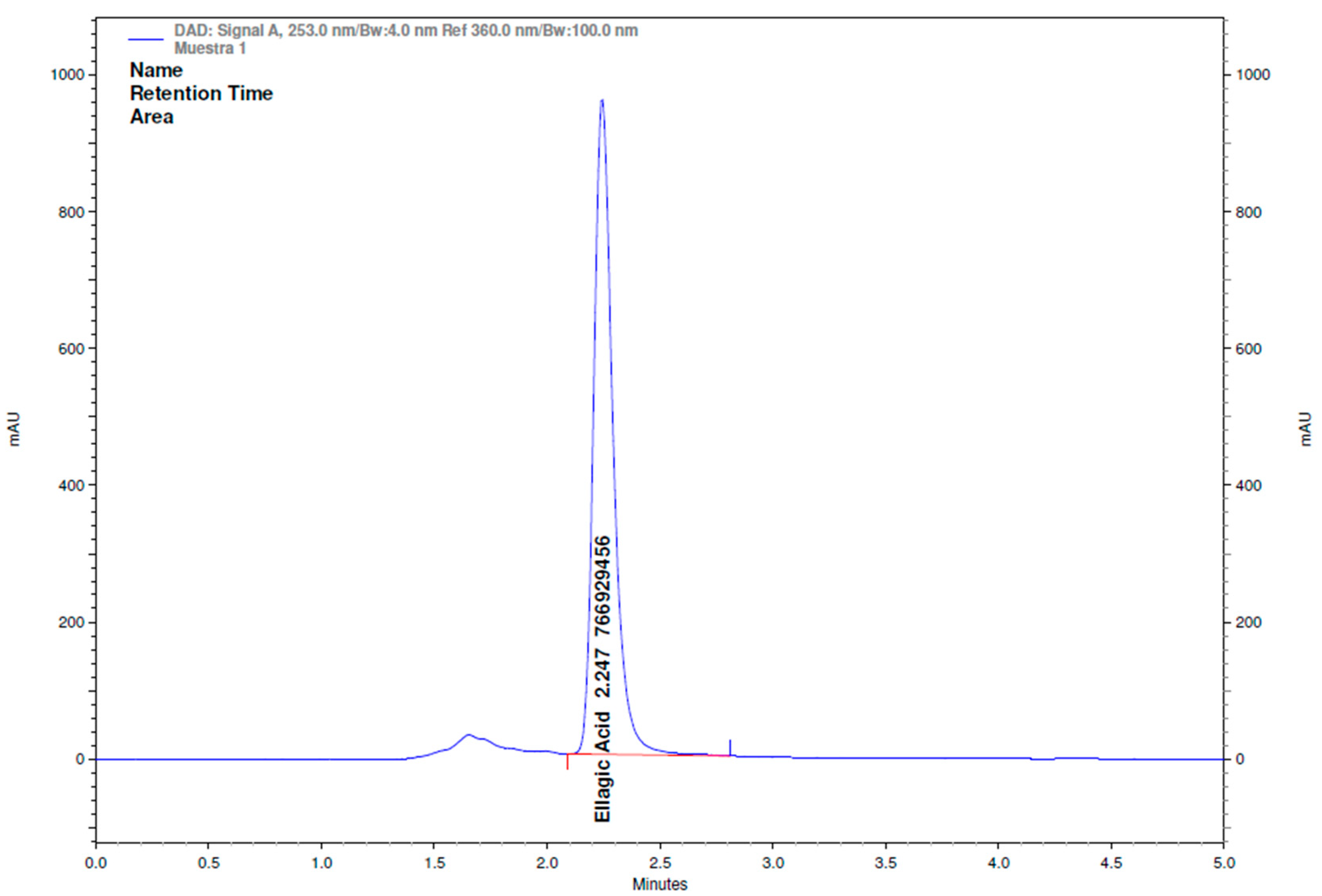

3.11. Ellagic acid Content Determination with HPLC-DAD in Reversed Phase

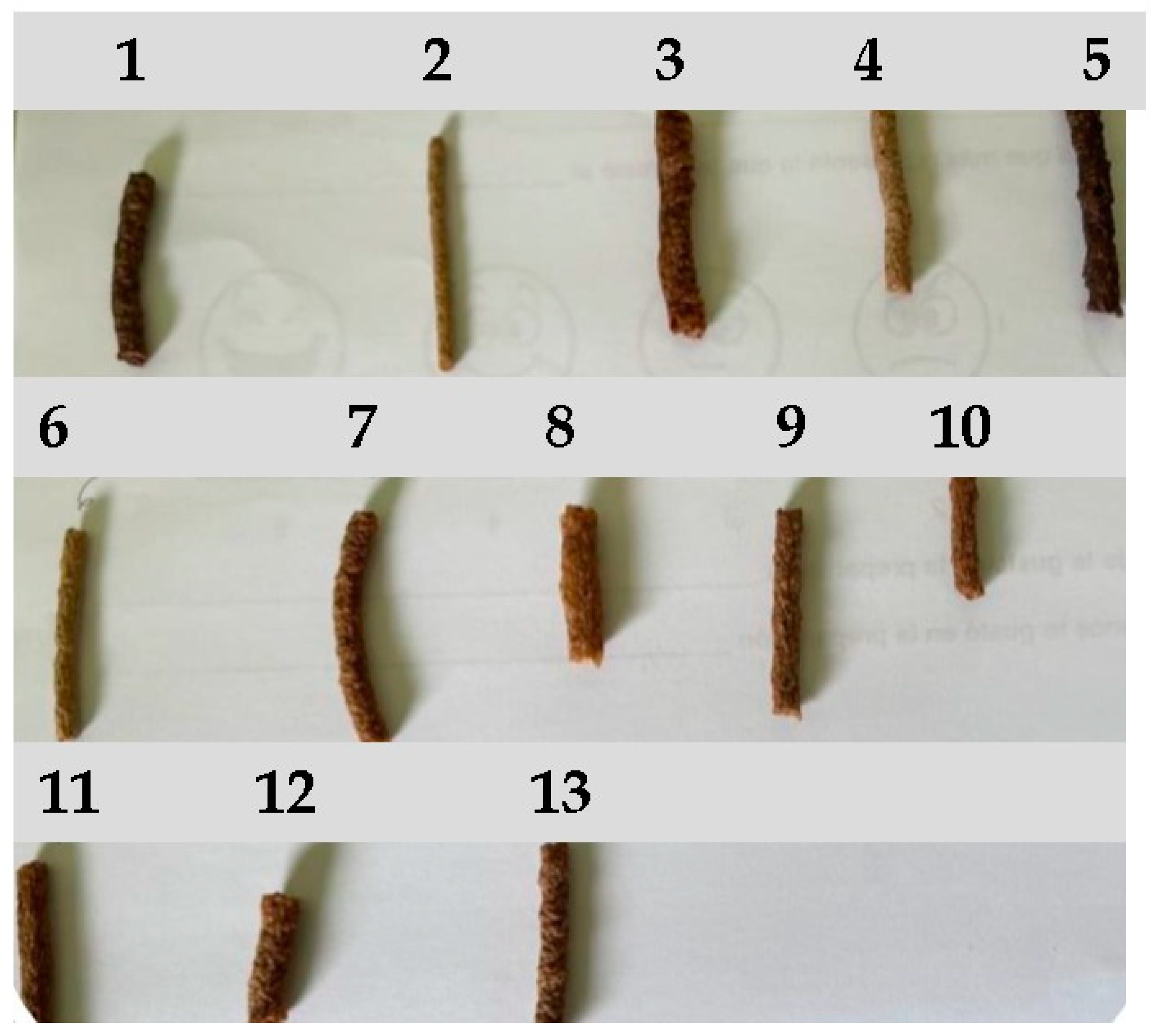

3.12. Appearance of Extruded Snacks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dable-Tupas, G.; Otero, M.C.B.; Bernolo, L. Functional Foods and Health Benefits. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals: Bioactive Components, Formulations and Innovations; Egbuna, C., Dable Tupas, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, K.M.; Francis, C.; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Functional Foods. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113(8), 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Nuño, Y.A.; Villarruel-López, A. Moléculas provenientes de alimentos con posibilidad de uso en el desarrollo de alimentos funcionales y nutracéuticos para el adulto mayor: una revisión narrativa. Aliment. Cienc. Los Aliment. 2025, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Santos-Zea, L. Editorial: Trends in the Design of Functional Foods for Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1393366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarruel-López, A.; Sánchez-Nuño, Y.A.; Herrejón-Vázquez, E.E.; Flores-García, E.E.; Orozco-Enríquez, C. Propiedades funcionales, aprovechamiento industrial y potenciales usos de la zarzamora (Rubus spp.) sobre la salud humana. Aliment. Cienc. Los Aliment. 2025, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. Guide to Functional Food Ingredients; Leatherhead Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Functional Food Ingredients Market: Trends, Opportunities & Forecast [Latest]. MarketsandMarkets. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/functional-food-ingredients-market-9242020.html (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Hasler, C.M. Functional Foods: Benefits, Concerns and Challenges—A Position Paper from the American Council on Science and Health. J. Nutr. 2002, 132(12), 3772–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TECH®, R.T.F. Alimentos funcionales ganan terreno en mercado mexicano. THE FOOD TECH - Medio de noticias líder en la Industria de Alimentos y Bebidas. Available online: https://thefoodtech.com/tendencias-de-consumo/alimentos-funcionales-ganan-terreno-en-mercado-mexicano/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Preciado-Saldaña, A.M.; Ruiz-Canizales, J.; Villegas-Ochoa, M.A.; Domínguez-Avila, J.A.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Aprovechamiento De Subproductos De La Industria Agroalimentaria. Un Acercamiento a La Economía Circular.

- Ferraz, D.; Pyka, A. Circular Economy, Bioeconomy, and Sustainable Development Goals: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P. de los Á. M.; Ortega, L.A.G.; López, G.B. Elaboración de una tortilla de maíz enriquecida con zanahoria (Daucus carota) y linaza (Linium usitatissimum) para controlar enfermedades cardiovasculares. UVserva 2024, No. 18, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Ashraf, M.; Kumar, R.; Khan, K.; Saqib, D.; Ali, S.S.; Khan, S. Role of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in Developing Sustainable Engineered Cementitious Composites. Front. Mater. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otalora Orrego, D.; Martin G, D.A. Técnicas Emergentes de Extracción de β-Caroteno Para La Valorización de Subproductos Agroindustriales de La Zanahoria (Daucus Carota L.): Una Revisión. Inf. Téc. 2021, 85, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Nuño, Y.A.; Zermeño-Ruiz, M.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.D.; Nuño, K.; Villarruel-López, A. Bioactive Compounds from Pigmented Corn (Zea Mays L.) and Their Effect on Health. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, O.P.; Lara, F.G.; Pérez, L.A.B. La nixtamalización y el valor nutritivo del maíz. Ciencias 2009, No. 092. [Google Scholar]

- Anayansi, E.-A.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; Torres-Chávez, P.I.; Barrón-Hoyos, J.M.; Figueroa-Cárdenas, J. de D.; López-Cervantes, J. La nixtamalización y su efecto en el contenido de antocianinas de maíces pigmentados, una revisión. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2013, 36(4), 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Lozada, G.M.; Villarruel-López, A.; Nuño, K.; García-García, A.; Sánchez-Nuño, Y.A.; Ramos-García, C.O. Clinically Effective Molecules of Natural Origin for Obesity Prevention or Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowshik, J.; Giri, H.; Kishore, T.K.K.; Kesavan, R.; Vankudavath, R.N.; Reddy, G.B.; Dixit, M.; Nagini, S. Ellagic Acid Inhibits VEGF/VEGFR2, PI3K/Akt and MAPK Signaling Cascades in the Hamster Cheek Pouch Carcinogenesis Model. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14(9), 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, A.J.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; Ortega, E.; Sala-Vila, A.; Lázaro, I. Ellagic Acid as a Tool to Limit the Diabetes Burden: Updated Evidence. Antioxidants 2020, 9(12), 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Lozada, G.M.; Villarruel-López, A.; Martínez-Abundis, E.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.; González-Ortiz, M.; Pérez-Rubio, K.G. Ellagic Acid Effect on the Components of Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Sensitivity and Insulin Secretion: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11(19), 5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Wang, X.; Cheng, M.; Wang, S.; Ma, K. The Multifaceted Mechanisms of Ellagic Acid in the Treatment of Tumors: State-of-the-Art. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.-B.; Ainsworth, P.; Plunkett, A.; Tucker, G.; Marson, H. The Effect of Extrusion Conditions on the Functional and Physical Properties of Wheat-Based Expanded Snacks. J. Food Eng. 2006, 73(2), 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Díaz, J.R.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; Barnard, J.; Balandrán-Quintana, R.R. Functional Properties of Extrudates Prepared with Blends of Wheat Flour/Pinto Bean Meal with Added Wheat Bran. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2007, 13(4), 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Espinoza, R.J.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mora-Rochín, S.; Gómez-Favela, M.A.; Perales-Sánchez, J.X.K.; Moreno-Espinoza, R.J.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mora-Rochín, S.; Gómez-Favela, M.A.; Perales-Sánchez, J.X.K. Alimento funcional para adultos mayores producido por extrusión a partir de granos integrales de maíz/frijol común. Acta Univ. 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Cortez, R.O.; Aguilar-Palazuelos, E.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Falfán Cortés, R.N.; Cadena Ramírez, A.; Delgado-Licon, E.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A. Physicochemical and Sensory Characterization of an Extruded Product from Blue Maize Meal and Orange Bagasse Using the Response Surface Methodology. CyTA - J. Food 2018, 16(1), 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO, Ed. ; The state of food and agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- mike. ¿Qué es una dieta sostenible en el siglo XXI?. nutricion clinica en medicina - gam. 2024. Available online: https://nutricionclinicaenmedicina.com/que-es-una-dieta-sostenible-en-el-siglo-xxi/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Dong, H.; Hou, H.; Zhang, X. Distribution of Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Activities of Different Bran Fractions from Three Pigmented Wheat Varieties. J. Chem. 2018, 2018(1), 6459243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Mazón, N.V.; Cevallos-Hermida, C.E.; Salazar-Yacelga, J.C.; Romero-Machado, E.R.; Gallegos-Murillo, P.L.; Cáceres-Mena, M.E. Uso de pruebas afectivas, discriminatorias y descriptivas de evaluación sensorial en el campo gastronómico. Dominio Las Cienc. 2018, 4(3), 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, D.T.; Assunção Botelho, R.B.; Ribeiro de Brito, R.; de Oliveira Pineli, L. de L.; Stedefeldt, E. Métodos Para Aplicar Las Pruebas de Aceptación Para La Alimentación Escolar: Validación de La Tarjeta Lúdica. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2013, 40(4), 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, A.; Wiessner, C.; König, I.R. Regression Analyses and Their Particularities in Observational Studies. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2024, 121(4), 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, C.; Patel, S.; Tripathi, A.K. Effect of Extrusion Parameters on Physical and Functional Quality of Soy Protein Enriched Maize Based Extruded Snack. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.C.V.; Damasceno-Silva, K.J.; Hashimoto, J.M.; Carvalho, C.W.P. de; Ascheri, J.L.R.; Galdeano, M.C.; Rocha, M. de M. Effect of Different Processing Conditions to Obtain Expanded Extruded Based on Cowpea. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2023, 26, e2022052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Gomez-Aldapa, C.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Ramirez-Wong, B.; Vivar-Vera, M.; Rosas, I.; Medrano Roldan, H.; Delgado, E. Effect of Extrusion Temperature, Moisture Content and Screw Speed on the Functional Properties of Aquaculture Balanced Feed. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2014, 26, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathad, G.N.; Gavahian, M.; Lin, J. Effects of Extrusion Parameters on the Physicochemical Properties of Mung Bean–Brown Rice Extrudate for New Product Development. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.O. Interaction of Starch with Some Food Macromolecules during the Extrusion Process and Its Effect on Modulating Physicochemical and Digestible Properties. A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 5, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, Y.; Mitchell, J.; Bhandari, B.; Prakash, S. Unlocking the Potential of Rice Bran through Extrusion: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2(3), 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Al-Attabi, Z.H.; Al-Habsi, N.; Al-Khusaibi, M. Measurement of Instrumental Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) of Foods. In Techniques to Measure Food Safety and Quality: Microbial, Chemical, and Sensory; Khan, M.S., Shafiur Rahman, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.M.; Forsido, S.F.; Kuyu, C.G.; Ahmed, E.H.; Andersa, K.N.; Chane, K.T.; Regasa, T.K. Effects of Extrusion Process Conditions on Nutritional, Anti-Nutritional, Physical, Functional, and Sensory Properties of Extruded Snack: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12(11), 8755–8761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Hu, H.; Chen, B.; Lin, Q.; Ji, H.; Jin, Z. Research Progress on the Physicochemical Properties of Starch-Based Foods by Extrusion Processing. Foods 2024, 13(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Development and Storage Study of Maize and Chickpea Based Extruded Snacks. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Valdez, L.C.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Perales-Sánchez, J.X.K.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mora-Rochín, S.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Gámez-Valdez, L.C.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Perales-Sánchez, J.X.K.; Milán-Carrillo, J.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mora-Rochín, S.; Reyes-Moreno, C. Effect of the Extruded Amaranth Flour Addition on the Nutritional, Nutraceutical and Sensory Quality of Tortillas Produced from Extruded Creole Blue Maize Flour. Biotecnia 2021, 23(2), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Batalla, L.; Hernández-Uribe, J.P.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Téllez-Jurado, A.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Pérez-Cadena, R.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A. Nutritional Characterization of Prosopis Laevigata Legume Tree (Mesquite) Seed Flour and the Effect of Extrusion Cooking on Its Bioactive Components. Foods 2018, 7(8), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, O., H.A. Efecto de la temperatura y velocidad de rotación del tornillo en el proceso de extrusión de maíz, quinua y avena para la elaboración de harina pregelatinizada, Zamorano: Escuela Agrícola Panamericana. 2016. Available online: https://bdigital.zamorano.edu/handle/11036/5765 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Córdoba Mesa, F.A. Evaluación del proceso de extrusión de doble tornillo a partir del modelamiento y simulación en Dinámica de Fluidos Computacionales (CFD) para la obtención de alimentos. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Chagman, G.; Santa-Cruz-Olivos, J.; Hidalgo, A.; Benavente, F.; Pérez-Camino, M.C.; Sotelo-Mendez, A.; Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Encina-Zelada, C.R. Aceite de Lupinus Mutabilis Obtenido Por Prensa Expeller: Análisis de Rendimiento, Caracterización Fisicoquímica, Capacidad Antioxidante, Ácidos Grados y Estabilidad Oxidativa. Sci. Agropecu. 2021, 12(2), 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cazares, L.A.; Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A. .; Campos-Vega, R.; Gaytán-Martínez, M. Influence of Extrusion Process on the Release of Phenolic Compounds from Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) Bagasse-Added Confections and Evaluation of Their Bioaccessibility, Intestinal Permeability, and Antioxidant Capacity. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Jayadeep, A. Impact of Extrusion on the Content and Bioaccessibility of Fat Soluble Nutraceuticals, Phenolics and Antioxidants Activity in Whole Maize. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyashan, N.; Perera, Y.S.; Xiao, R.; Abeykoon, C. Investigation of the Effect of Materials and Processing Conditions in Twin-Screw Extrusion. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2024, 7(3), 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Barrios, E.F.; Albis Arrieta, A.R.; Cervera Cahuana, S. Extrusión y calidad física en formulaciones de alimento para engorde de camarones: una revisión. Prospectiva 2024, 22(2). [Google Scholar]

- Maina, J.W. Analysis of the Factors That Determine Food Acceptability. Pharma Innov. J. 2018, 7(5), 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Ackbarali, D.; Maharaj, R. Sensory Evaluation as a Tool in Determining Acceptability of Innovative Products Developed by Undergraduate Students in Food Science and Technology at The University of Trinidad and Tobago. J. Curric. Teach. 2014, 3(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongi, R.J.; Gomezulu, A.D. Descriptive Sensory Analysis, Consumer Acceptability, and Conjoint Analysis of Beef Sausages Prepared from a Pigeon Pea Protein Binder. Heliyon 2022, 8(9), e10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A.S.; Delmore, B.; Chiu, E.S. High-Quality Dietary Protein: The Key to Healthy Granulation Tissue. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2024, 37(10), 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Ziani, K.; Mititelu, M.; Oprea, E.; Neacșu, S.M.; Moroșan, E.; Dumitrescu, D.-E.; Roșca, A.C.; Drăgănescu, D.; Negrei, C. Therapeutic Benefits and Dietary Restrictions of Fiber Intake: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2022, 14(13), 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients 2020, 12(10), 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Ugalde-Nicalo, P.; Welsh, J.A.; Angeles, J.E.; Cordero, M.; Harlow, K.E.; Alazraki, A.; Durelle, J.; Knight-Scott, J.; Newton, K.P.; Cleeton, R.; Knott, C.; Konomi, J.; Middleton, M.S.; Travers, C.; Sirlin, C.B.; Hernandez, A.; Sekkarie, A.; McCracken, C.; Vos, M.B. Effect of a Low Free Sugar Diet vs Usual Diet on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adolescent Boys: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321(3), 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, S. Extrusion Technology and Its Effects on Nutritional Values. Food Nutr. Sci. - Int. J. 45289, 07. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.; Yan, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Strategy for Sodium-Salt Substitution: On the Relationship between Hypertension and Dietary Intake of Cations. Food Res. Int. Ott. Ont 2022, 156, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Meng, X. Ellagic Acid and Its Anti-Aging Effects on Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(18), 10937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čižmáriková, M.; Michalková, R.; Mirossay, L.; Mojžišová, G.; Zigová, M.; Bardelčíková, A.; Mojžiš, J. Ellagic Acid and Cancer Hallmarks: Insights from Experimental Evidence. Biomolecules 2023, 13(11), 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polce, S.A.; Burke, C.; França, L.M.; Kramer, B.; de Andrade Paes, A.M.; Carrillo-Sepulveda, M.A. Ellagic Acid Alleviates Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Insulin Resistance in Diabetic Female Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marić, B.D.; Bodroža, S.M.I.; Ilić, N.M.; Kojić, J.S.; Krulj, J.A. Influence of Different Extrusion Temperatures on the Stability of Ellagic Acid from Raspberry Seeds. Food Feed Res. 2018, 45(1), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Buckner, T.; Shay, N.F.; Gu, L.; Chung, S. Improvements in Metabolic Health with Consumption of Ellagic Acid and Subsequent Conversion into Urolithins: Evidence and Mechanisms12. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7(5), 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded | Actual | |||

| Treatment | X1 | X2 | BT (°C) | SS (rpm) |

| 1 | +1.414 | 0 | 170 | 145 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 145 |

| 3 | -1 | +1 | 127.322 | 212.175 |

| 4 | +1 | -1 | 162.678 | 77.8249 |

| 5 | -1.414 | 0 | 120 | 145 |

| 6 | 0 | +1.414 | 145 | 240 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 145 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 145 |

| 9 | +1 | +1 | 162.678 | 212.175 |

| 10 | -1 | -1 | 127.322 | 77.8249 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 145 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 145 |

| 13 | 0 | -1.414 | 145 | 50 |

| Coefficients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Intercept | Linear | Quadratic | Interaction | ||||

| A | B | AB | A2 | B2 | A2B | AB2 | ||

| EI | +1.96 | -0.41*** | +0.36** | +0.03 | +0.29* | +0.006 | +0.43 | +0.14 |

| BD (AD) | +0.30 | -0.02 | -0.13** | +0.06 | +0.09 | +0.04 | -0.16 | -0.15 |

| PF (H) | +13.21 | -17.27*** | -5.48* | +10.86* | +15.31** | -1.69 | -13.03 | +15.9* |

| WAI | +5.72 | +0.09 | -0.80* | -1.23* | -0.22 | -0.13 | +2.72* | -0.99 |

| AFPI | +48.60 | +5.72 | +6.66 | -3.66 | -17.52* | +18.69* | -26.55 | +15.99 |

| DFPI | +14.22 | -0.91 | +4.22 | +0.37 | -5.99 | +3.16 | -16 | +8.29 |

| Response | R2 | Adequate Precision | CV (%) | F value | p of F (model) | Lack of fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.9057 | 11.3216 | 7.62 | 13.44 | 0.0018 | 0.3526 |

| BD (AD) | 0.8282 | 8.4050 | 15.47 | 6.75 | 0.0132 | 0.0298 |

| PF (H) | 0.9270 | 12.7868 | 26.30 | 17.79 | 0.0007 | 0.0015 |

| WAI | 0.8297 | 6.5469 | 7.14 | 3.48 | 0.0944 | 0.5344 |

| AFPI | 0.8123 | 9.7396 | 15.00 | 6.06 | 0.0176 | 0.2124 |

| DFPI | 0.7754 | 5.6930 | 23.99 | 2.47 | 0.1688 | 0.7033 |

| Response (dependent variable) | Low optimal range | High optimal range | Unit of measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 2.00 | 2.30 | Ratio |

| BD (AD) | 0.23 | 0.30 | g/cm3 |

| PF (H) | 7.80 | 10.00 | N |

| WAI | 5.50 | 6.70 | g/g |

| AFPI | 60.00 | 80.00 | % |

| DFPI | 15.00 | 21.00 | % |

| Determination | Result |

|---|---|

| Humidity | 6.5 g |

| Ashes | 2.4 g |

| Proteins | 8.9 g |

| Total fat | 2.0 g |

| Saturated fat | 2.0 g |

| Unsaturated fat | 0.0 g |

| Dietary fiber | 6.6 g |

| Total carbohydrates | 73.5 g |

| Total reducing sugars | 7.0 g |

| Energetic content | 348.3 kcal / 1457.3 kJ |

| Sodium | 83.0 mg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).