1. Introduction

Deep brain stimulation was first shown to be effective as a therapeutic option in essential tremor and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) in 1987 [

1]. Since its initial use, the indications for DBS have expanded to include generalized dystonia, tremors, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders, and early PD leading to a growing number of procedures [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Advancements in DBS technology, such as enhanced battery life, adjustable stimulation parameters, and directional stimulation, have further improved its efficacy [

7]. In addition, ongoing developments, including closed-loop adaptive stimulation, continue to refine and expand its clinical applications [

7].

However, although DBS is generally considered a safe procedure [

8], complications can still occur. Previous studies found a mortality rate of 0.2% and a permanent morbidity rate of 0.6%, with 12.2% of patients having hardware complications [

2]. Adverse effects of DBS include cognitive decline [

9], ineffective stimulation/device dysfunction [

10], infection [

10], delirium [

11], and hemorrhage [

11] amongst others. In addition, with a cost of over

$22,000 USD for the medical care associated with explantation, early explant poses a significant burden to both patients and the healthcare system [

8]. Due to these factors, prior literature has identified explant rates of up to 5.6% [

12], suggesting a need to improved identification of risk factors for explant. While previous literature has identified risk factors for DBS complication including advanced age, male sex, and comorbidities such as dementia, hypertension, and coagulopathy, only elevated body mass index (BMI) has been demonstrated to be an risk factors for explantation itself [

13,

14]. As such, there remains a need to precisely determine which patients are at high risk for early explantation. To this end, we applied a novel approach using supervised machine learning to identify risk factors for DBS explant within the first two-years following placement.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was designed in accordance with TRIPOD-AI guidelines for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods.

2.1. Data

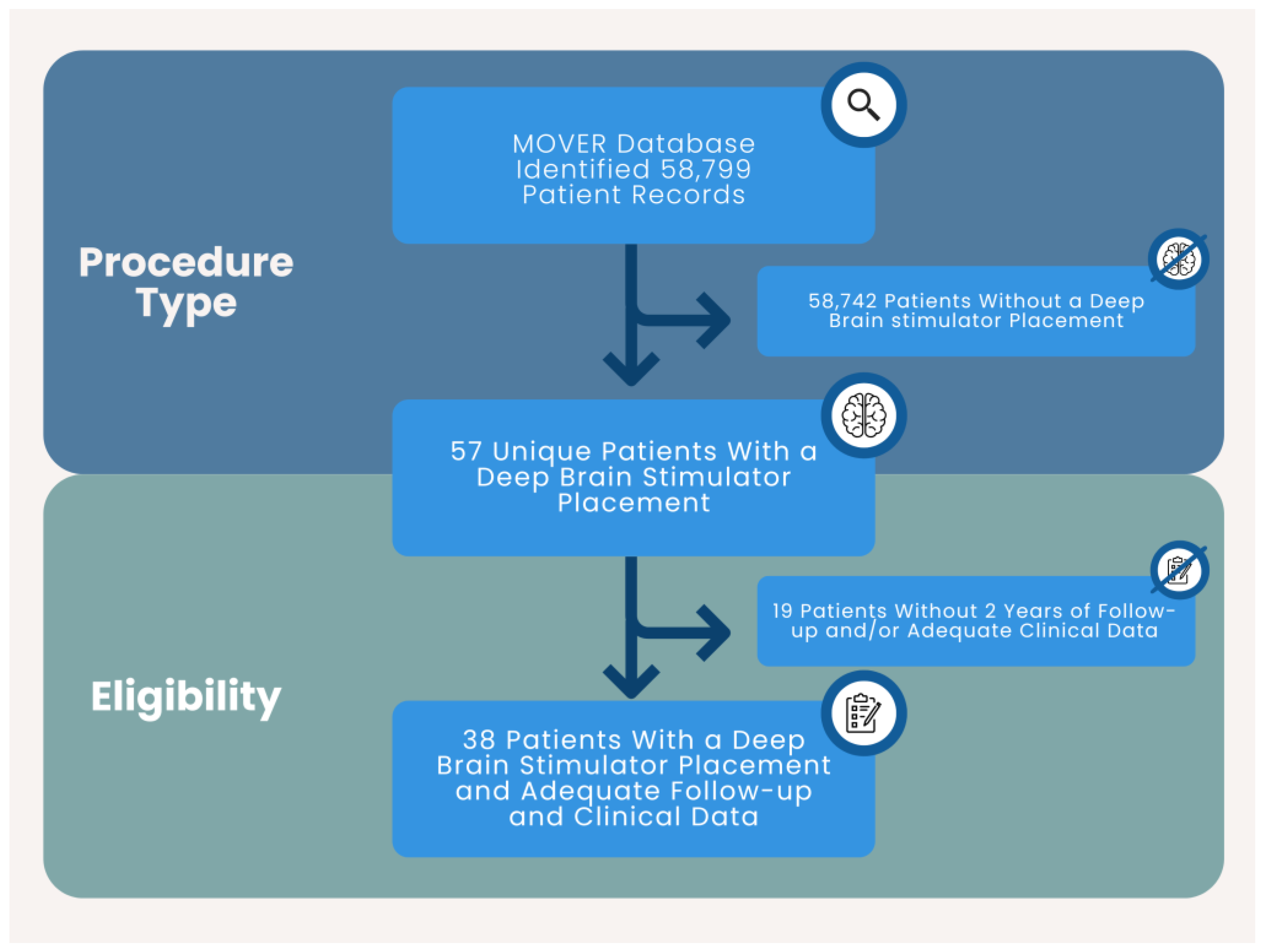

Data was obtained via a Data Use Agreement between the authors and University of California Irvine Medical Center. Data was collected from the Medical Informatics Operating room Vitals and Events Repository (MOVER) database [

15] which contains de-identified electronic health records data from 58,799 unique patients who underwent surgery at the University of California Irvine Medical Center. Data within the MOVER database is de-identified in accordance with HIPAA Privacy Rule, therefore patient consent was not obtained

2.2. Participants

Records included in the study involved patients with a DBS stimulator placement at a single academic center. Treatment consisted of DBS placement. Inclusion criteria: adult (≥18 years of age), DBS procedure, and at least two years of follow up. Exclusion Criteria: <18 years of age, <2 years of follow up, no DBS procedure. 38 unique patients were included in the study. (

Figure 1)

2.3. Data Preparation

Variables were created using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10-CM codes, patient demographics, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) score, anesthesia type, and postoperative events including hospitalizations, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions. The included codes and/or definitions for each of the study variables can be seen in

Table S1. Sex was encoded 1: female, 0: male. Medical comorbidities were encoded 1: present, 0: absent. Anesthesia type was encoded 1: monitored anesthesia care, 0: general anesthesia. ICU admission was encoded 1: yes, 0: no. LOS and ASA score was encoded as the numerical value.

2.4. Predictors

Predictors were chosen broadly, as the methodology using recursive factor elimination with cross validation would remove variables offering limited predictive value in a data-driven manner.

2.5. Sample Size

All patients meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria were included. The study cohort consisted of 38 patient records.

2.6. Missing Data

No records had missing data.

2.7. Analytical Methods

The data analysis plan was written prior to accessing the data. Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians ± interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as n-values and percentages. Initial analysis consisted of comparing patients with DBS explantation to those without explantation using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Next, the data was imported into Anaconda Version 2.3.1. (Anaconda Software Distribution. Austin, TX). The following add-ons were used for analysis: pandas [

16], numpy, sklearn [

17], scikit-learn-extra [

17], MatLab (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), and seaborn [

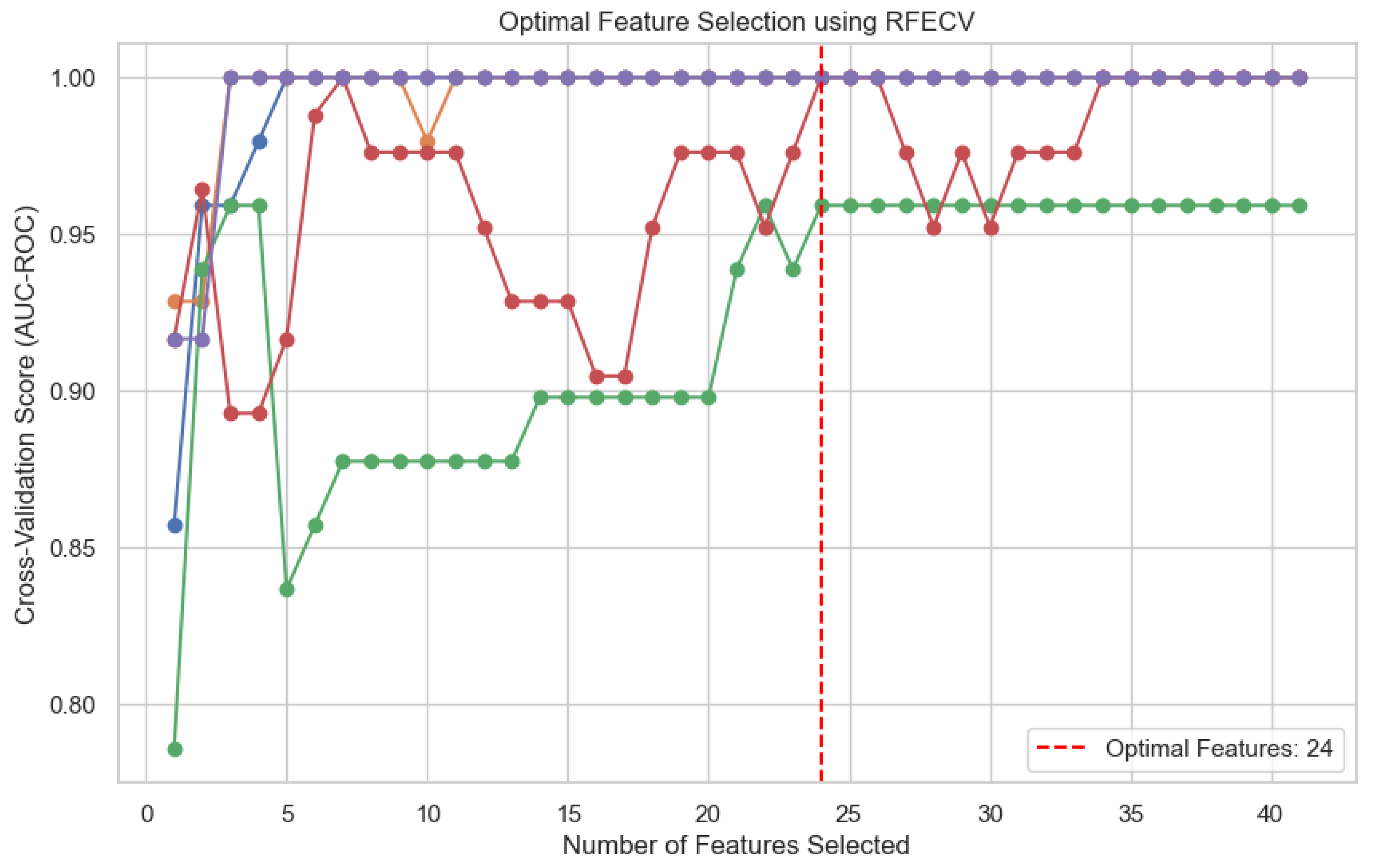

18]. The target variable (explantation or no explantation) was defined, the features were scaled, and Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to balance the classes. To define the optimal features to include in the model, recursive feature elimination with cross validation (RFECV) was imported from sklearn.feature_selection and cross_val_score was imported from sklearn.model_selection [

17]. Five iterations of RFECV with different data splits were performed and the ideal number of features (24) was defined using the optimal average area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) (

Figure 2). The data was then limited to the 24 selected features and random_state was used to split the data into training (80%) and testing (20%) using deterministic train-test sets. The test data was not used in training of the model. The logistic model was fitted, and performance was assessed using precision, recall, f1-score, and AUC. The model was then used to define odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each of the variables. The variables were considered to convey statistically significant increased risk if the odds ratio and entire 95% confidence interval was greater than 1.0.

2.8. Class Imbalance

Class imbalance was mitigated using SMOTE.

2.9. Fairness

Five iterations of recursive factor elimination with cross validation were applied to minimize inherent risk of overfitting.

2.10. Model Output

Output consisted of an odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. In rare outcomes, odds ratio approximates relative risk, making this an appropriate measure for the study. Statistical significance was based upon an odds ratio and 95% confidence interval > 1.0 or < 1.0.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Demographics

Baseline cohort characteristics can be seen in

Table 1. The study cohort was 65.8% male with an average age of 64.8 (+/- 11.6) years. 5 of the 38 included patients (13%) had DBS explantation. The most common indication was primary PD (78.9%), followed by dystonia (23.7%). Almost all cases were performed under general anesthesia (97.4%), with patients having a median ASA score of 3.0 (IQR: 3.0 – 3.0). Median length of stay was 1.0 (IQR 1.0 - 1.3) days, with most patients requiring ICU admission (94.7%). No statistically significant differences were noted for any of the demographic or perioperative variables. The most common medical comorbidities seen were hyperlipidemia (18.4%), sleep disorders (15.8%), dysautonomia (15.8%), obesity (15.8%), and personal history of malignancy (15.8%). Chronic pain was more frequently seen in patients with DBS explantation than those without (p = 0.0108), however no other statistically significant differences were noted. Amongst psychiatric and social comorbidities, tobacco use (31.2%), anxiety (21.1%), major depressive disorder (15.8%), and opioid use (5.3%) were present. However, only tobacco use was significantly higher in patients with explant (p = 0.0026). No other statistically significant differences were seen between the cohorts.

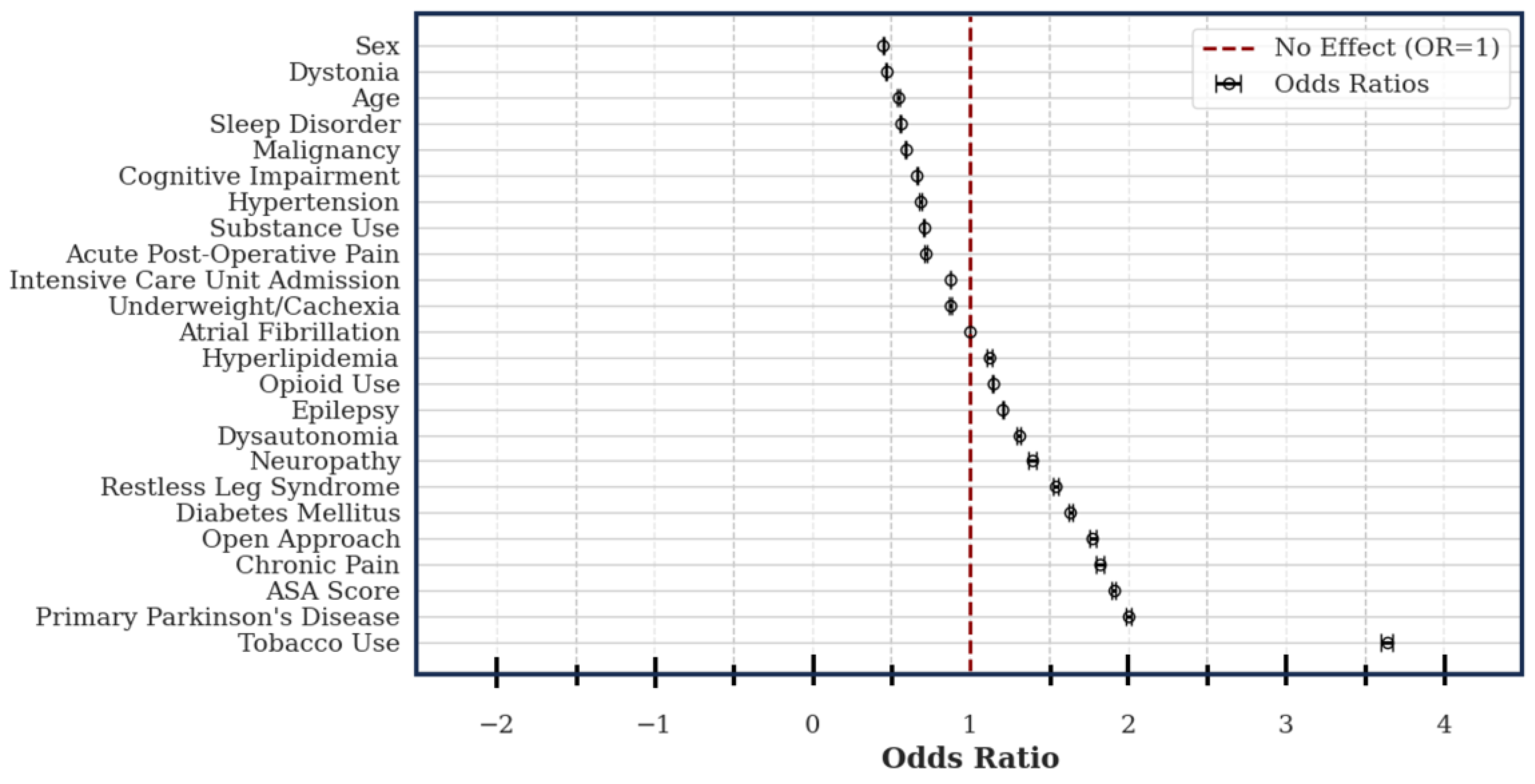

3.2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Model

As patient’s variables do not exist in isolation, we hypothesized a model which could account for the interaction between variables may more accurately uncover potential perioperative risk factors. To test this hypothesis, we applied supervised machine learning using RFECV and a multivariate logistic regression model. The logistic regression model displayed robust performance with an average precision of 0.89, an average recall of 0.86, an average f1-score of 0.86, and AUC-ROC of 1.0.

Amongst the assessed variables, 12 conveyed increased risk of explant: tobacco use (OR: 3.64; CI: 3.60 – 3.68), primary PD (OR: 2.01; CI: 1.99 – 2.02), ASA score (OR: 1.91; CI: 1.90 – 1.92), chronic pain (OR: 1.82; CI: 1.80 – 1.85), diabetes (OR: 1.63; CI: 1.62 – 1.65), restless leg syndrome (OR: 1.55; CI: 1.53 – 1.56), neuropathy (OR: 1.40; CI: 1.37 – 1.42), dysautonomia (OR: 1.31; CI: 1.30 – 1.32), epilepsy (OR: 1.21; CI: 1.20 – 1.21), a history of opioid use (OR: 1.14; CI: 1.14 – 1.15), and hyperlipidemia (OR: 1.12; CI: 1.11 – 1.14). Female sex (OR: 0.45; CI: 0.45 – 0.45), an indication of dystonia (OR: 0.47; CI: 0.46 – 0.47), patient age (OR: 0.55; CI: 0.54 – 0.55), sleep disorders (OR: 0.56; CI: 0.55 – 0.56), history of malignancy (OR: 0.59; CI: 0.59 – 0.60), cognitive impairment (OR: 0.66; CI; 0.66 – 0.67), hypertension (OR: 0.69; CI: 0.68 – 0.69), illicit substance use (OR: 0.71; CI: 0.70 – 0.71), acute post-operative pain (OR: 0.72; CI: 0.71 – 0.72), ICU admission (OR: 0.87; CI: 0.87 – 0.88), comorbid cachexia/underweight (OR: 0.88; CI: 0.87 – 0.88), and atrial fibrillation (OR: 1.00; CI: 1.00 – 1.00) were included in the model, however they all conveyed decreased or unchanged risk. (

Figure 3)

4. Discussion

Since it’s advent as a viable treatment for PD, deep brain stimulation has continued to grow in indications and number of procedures [3-6]. While significant advances have been made in increasing the precision of DBS technology itself, rates of hardware-related complications [

19] and explantation [

12] remain unacceptably high, suggesting a need to more precisely identify patients at risk of adverse outcomes. Here, we sought to address this challenge by taking a unique approach using supervised machine learning in the form of a multivariate logistic regression combined with recursive factor elimination with cross validation. In doing so, we identified a history of tobacco use, an indication of primary PD, increased ASA score, comorbid chronic pain, an open surgical approach, comorbid diabetes, comorbid restless leg syndrome, comorbid neuropathy, dysautonomia, comorbid epilepsy, a history of opioid use, and comorbid hyperlipidemia as potential risk factors for early DBS explantation.

A national study conducted in Korea identified older age, male sex, comorbid dementia, and comorbid fractures as factors predictive of morbidity following DBS placement [

14]. Similarly, Ward et al. identified ineffective stimulation (28%), lead dysfunction (30%), and infections (28%) as etiologies of DBS failure [

10]. A retrospective, single institution study using basic statistical analysis identified use of topical vancomycin (as opposed to intrawound) as a risk factor for DBS infection [

19]. A second single-center retrospective study identified use of general anesthesia, hypertension, heart disease, and depression as risk factors for increased postoperative length of stay [

20]. Furthermore, while associations with explant were limited, they did note an association with preoperative body mass index and risk of explant [

20]. A retrospective study by Deeb et al. assessing the association between psychiatric comorbidities and DBS explantation in a Tourette syndrome database found no statistically significant associations [

12].

Limitations of our study include the limited number of patients, the retrospective design, the use of ICD codes which limits the ability to capture granular clinical reasoning [

21], and the inclusion of a singular center. Furthermore, the rate of explant within the MOVER database was higher (13%) than typically reported in the literature [

12]. We hypothesize this may be a result of the small sample size. Strengths of the study include the robust number of assessed variables (40), the use of a supervised machine learning model allowing for the assessment of between variables interactions, and use of recursive factor elimination with cross validation to identify the optimal variables.

5. Conclusions

Identification of risk factors for DBS explant has proven challenging using basic statistical models, not well adapted for rare outcomes. Here, we offer a novel methodology using an optimized multivariable logistic regression which may offer a solution to this challenge. Further study, with larger number of patients are needed to validate the results of this small retrospective, pilot study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Detailed definitions of all study variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.M., P.J.M.; Methodology, Y.C.M. and P.J.M.; Formal Analysis, P.J.M. and A.S.P.; Resources, Y.C.M.; Data Curation, Y.C.M., P.J.M. and A.S.P; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.C.M., P.J.M., and A.S.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.C.M.; Validation, Y.C.M.; Visualization, Y.C.M. and P.J.M.; Supervision, Y.C.M.; Funding Acquisition, Y.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Y.C.M. receives grant support from the Saint Louis University Department of Anesthesiology. P.J.M. receives grant support from the American Academy of Neurology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to use of only data de-identified in accordance with HIPPAA Privacy Rule. Data was obtained via a data use agreement between the author’s and University of California Irvine.

Informed Consent Statement

Data within the database was de-identified in accordance with HIPPAA Privacy Rule, so patient consent was not required or obtained.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors are in debt to Daniel Roke and Shannon (Mick) Kilkelly for fostering an atmosphere conducive to research in the Saint Louis University Department of Anesthesiology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD |

Parkinson’s Disease |

| DBS |

Deep brain stimulation |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| RFECV |

Recursive factor elimination with cross validation |

| MOVER |

Medical Informatics Operating room Vitals and Events Repository |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CI |

95% confidence interval |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases |

| SMOTE |

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| LOS |

Length of stay |

References

- Benabid, A.L., et al., Combined (thalamotomy and stimulation) stereotactic surgery of the VIM thalamic nucleus for bilateral Parkinson disease. Appl Neurophysiol, 1987. 50(1-6): p. 344-6. [CrossRef]

- Servello, D., et al., Complications of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: a single-center experience of 517 consecutive cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2023. 165(11): p. 3385-3396. [CrossRef]

- Hacker, M.L., et al., Deep brain stimulation in early-stage Parkinson disease: Five-year outcomes. Neurology, 2020. 95(4): p. e393-e401. [CrossRef]

- Figee, M., et al., Deep Brain Stimulation for Depression. Neurotherapeutics, 2022. 19(4): p. 1229-1245. [CrossRef]

- Knotkova, H., et al., Neuromodulation for chronic pain. Lancet, 2021. 397(10289): p. 2111-2124. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., Efficacy and safety of combined deep brain stimulation with capsulotomy for comorbid motor and psychiatric symptoms in Tourette's syndrome: Experience and evidence. Asian J Psychiatr, 2024. 94: p. 103960. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.K., et al., Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol, 2021. 17(2): p. 75-87. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H., J.K. Yue, and D.D. Wang, Trends in safety and cost of deep brain stimulation for treatment of movement disorders in the United States: 2002-2014. Br J Neurosurg, 2021. 35(1): p. 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.M., et al., A brain network for deep brain stimulation induced cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease. Brain, 2022. 145(4): p. 1410-1421. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M., et al., Complications associated with deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a MAUDE study. Br J Neurosurg, 2021. 35(5): p. 625-628. [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.C., et al., Deep brain stimulation in PD: risk of complications, morbidity, and hospitalizations: a systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci, 2023. 15: p. 1258190. [CrossRef]

- Deeb, W., et al., Deep brain stimulation lead removal in Tourette syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2020. 77: p. 89-93. [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.H., et al., Complications After Deep Brain Stimulation: A 21-Year Experience in 426 Patients. Front Aging Neurosci, 2022. 14: p. 819730. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A., et al., Mortality of Deep Brain Stimulation and Risk Factors in Patients With Parkinson's Disease: A National Cohort Study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci, 2023. 38(3): p. e10. [CrossRef]

- Samad, M., et al., Medical Informatics Operating Room Vitals and Events Repository (MOVER): a public-access operating room database. JAMIA Open, 2023. 6(4): p. ooad084. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W., Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, 2010: p. 51-56.

- Fabian Pedregosa, G.V., Alexandre Gramfort, Vincent Michel, Bertrand Thirion, Olivier Grisel, Mathieu Blondel, Peter Prettenhofer, Ron Weiss, Vincent Dubourg, Jake Vanderplas, Alexandre Passos, David Cournapeau, Matthieu Brucher, Matthieu Perrot, Édouard Duchesnay, Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python, in Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2011. p. 2825-2830.

- Waskom, M.L., seaborn: statistical data visualization. The Journal of Open Source Software, 2021. 6: p. 3021. [CrossRef]

- Abode-Iyamah, K.O., et al., Deep brain stimulation hardware-related infections: 10-year experience at a single institution. J Neurosurg, 2019. 130(2): p. 629-638. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbach, J., et al., The Rate and Risk Factors of Deep Brain Stimulation-Associated Complications: A Single-Center Experience. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N. and T. Weaver, Response to the Letter to the Editor Regarding: "Identifying Predictors for Early Percutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulator Explant at One and Two Years: A Retrospective Database Analysis". Neuromodulation, 2023. 26(3): p. 710. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).