Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

"[...] involves the process of systematic and professional help/support, through the use of educational and interpretative procedures with the aim of: improving self-knowledge; teaching how to solve problems of various kinds; teaching how to make prudent decisions; how to make responsible life project planning; and, finally, teaching how to relate fruitfully to the local and global environment" [10] (p. 40).

"[…] counseling is also a process of help, of a direct and interpersonal nature, which, through personal, face-to-face communication, aims to contribute to the solution and/or improvement of the person's problems" [10] (p.41).

- The main objectives are prevention and human development, understanding that the latter is culturally and socially mediate.

- Guidance action must be foreseen, planned and evaluated, and it is essential that it be proactive and systemic in nature.

- Guidance must reach all people in a generalized manner. For this reason, efficient mechanisms must be promoted, and it is advisable that guidance specialists do not intervene directly.

- Teachers are first order guidance agents, being the tutorial action the tool/space to develop guidance.

- The specialists work symmetrically and collaboratively with other educational, social and community agents.

2. Materials and Methods

- First phase: In this phase, the scope of the review was delimited with the advice of a group of 8 experienced colleagues. It was decided to focus on the analysis of theoretical models of educational guidance and psycho-pedagogical intervention.

- Second phase: Characterised by the search for sources in databases (Scopus, Dialnet, ERIC, Science Direct, Taylor & Francis, Google Scholar and InDICEs-CSIC) and in the Network of Spanish University and Scientific Libraries, in order to incorporate manuals and reference works in the field of educational guidance (Table 2).

- Third phase: In this phase, the sources were collected, analysed and organised, and the information extracted was synthesised in tables, as shown below. For this phase, the same criteria applied by Barbosa-Chacón et al. [20] in the hermeneutic phase of the reviews were used. For this purpose, four sub-stages were established: (1) classification and establishment of order of the sources of information and summary of data; (2) definition of categories (educational models or principles, content, methodology, agents involved); (3) search for central categories; (4) qualitative-interpretative analysis of the information; (5) analysis of the information and its interpretation; and (6) analysis of the information and its interpretation.

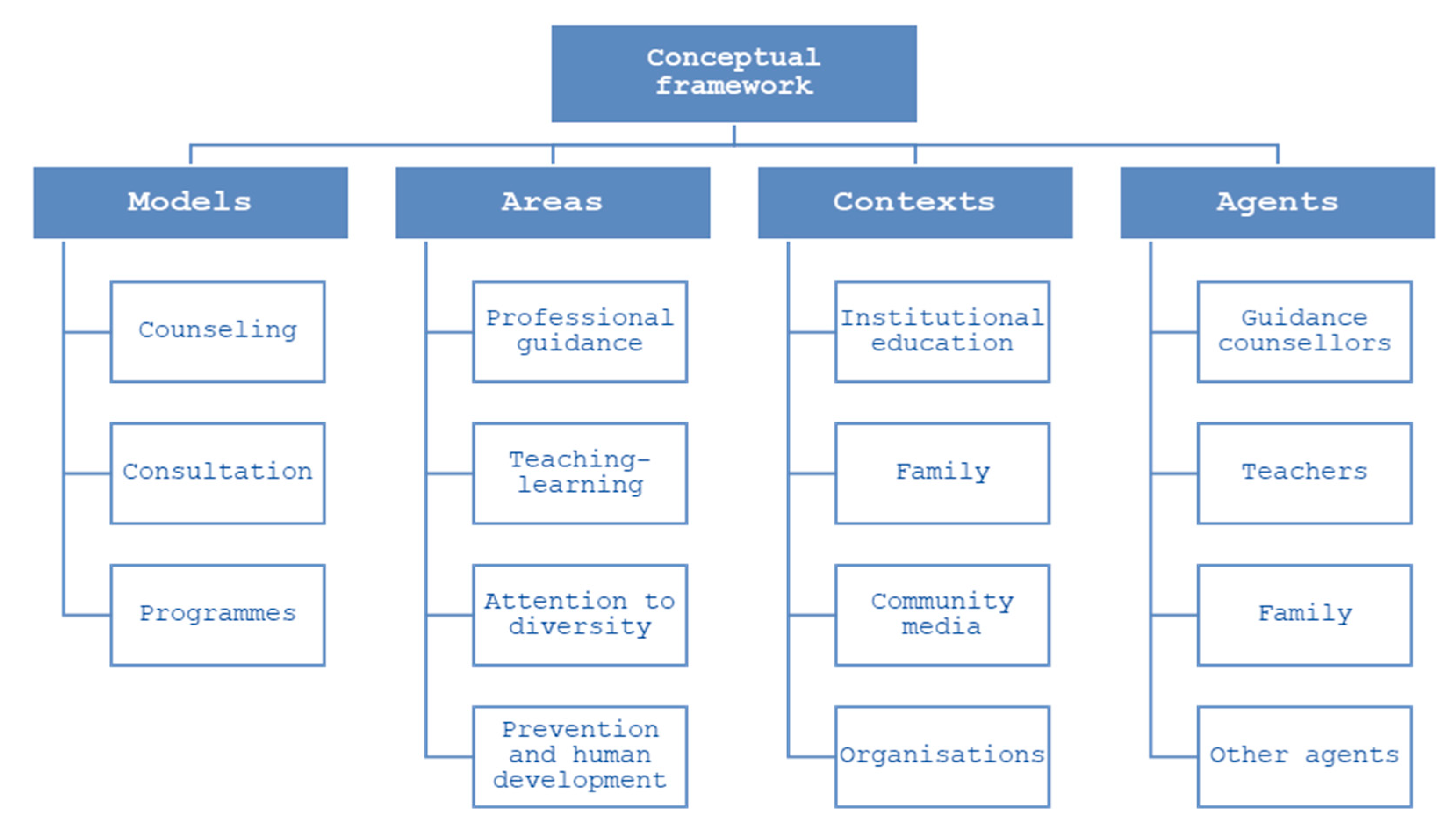

3. Results

3.1. Guidance Intervention Models

3.1.1. Counseling Model

- −

- Personal, direct and individual assistance relationship.

- −

- Dyadic character: counsellor and counselee.

- −

- Asymmetric relationship.

- −

- Therapeutic and reactive purposes.

"A communication process that acts on two levels (cognitive and emotional) and that takes place in three dimensions: interviewer-coach, interviewee-coachee and context (...). The purpose of the interview in the helping relationship is to help people to better understand and cope with their existential problems and to improve communication and interpersonal relationships by creating a facilitating climate (rapport) that favors the personal involvement of the person being helped in the process" [41] (p. 72).

- −

- Authenticity and sincerity. Ability of the interviewer to be free, genuine and sincere.

- −

- Empathy. Ability to perceive what the interviewee is experiencing, identify with him/her, share his/her feelings and communicate appropriately.

- −

- Closeness and understanding. Ability to be approachable, respecting the dignity of the person being interviewed and showing acceptance of the interviewee's decisions.

- −

- Concreteness. Ability to express in concrete and specific terms with feelings expressed by the interviewee.

- −

- Confrontation of incongruities. Ability to adequately show discrepancies be-tween what the interviewee thinks, feels, says and does.

- −

- Assertiveness. Ability of the interviewer to express opinions and thoughts in an appropriate manner and without denying, offending or demeaning the interviewee.

- −

- Personalization. Ability to help the oriented person to take ownership of his or her problem, accepting his or her degree of control and assuming responsibility for it.

- −

- Self-disclosure. Ability to share, in a measured and responsible manner, the interviewer's personal feelings and experiences for the benefit of the person being inter-viewed.

- −

- Acceptance of the person being interviewed. This is a fundamental attitude of the person being interviewed. In the words of Repetto "positive and unconditional acceptance, respect and cordiality" [37] (p. 271).

- −

- Self-realization. Ability to live autonomously, freely and openly, that is, to be self-directed.

- −

- Relationship to the moment. Ability of the interviewer to interpret the feelings of the interviewee and the relational situation between the interviewee and the interviewee in each moment, that is, in the here and now.

-

Initial phase: beginning of the helping relationship:Request for assistance from the person in need. An appropriate relationship is established between the counseling specialist and the person being counseled.

-

Phase one: diagnosis:Diagnosis of the situation posed by the person requesting help. Internalization and self-exploration by the person requesting help. Top-down character.

-

Phase two: treatment:Treatment is issued based on diagnosis. Construction and initiation of action. Self-concept, self-acceptance and self-esteem are enhanced. Bottom-up and constructive character.

-

Evaluation phase:Follow-up and evaluation of the intervention.

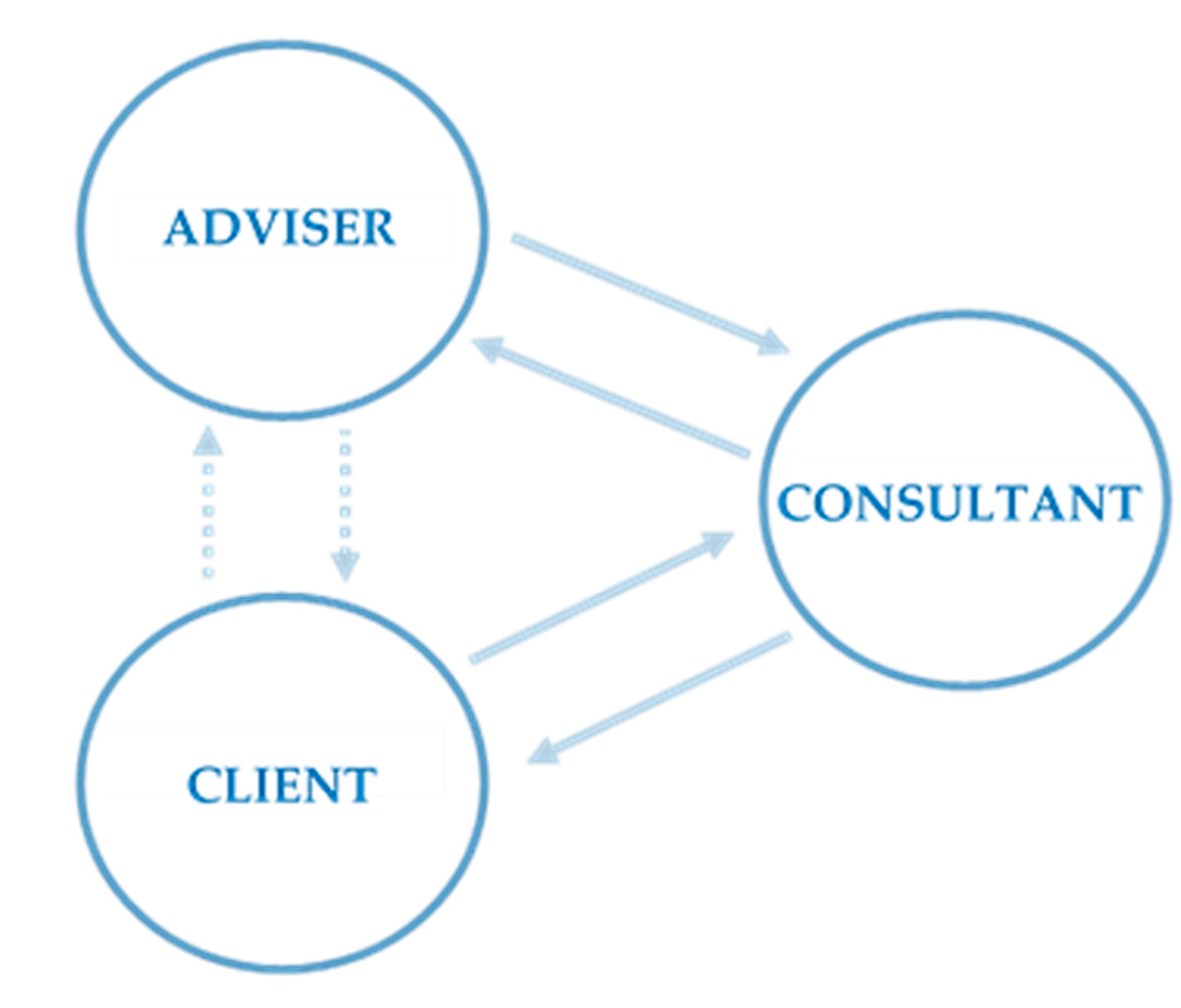

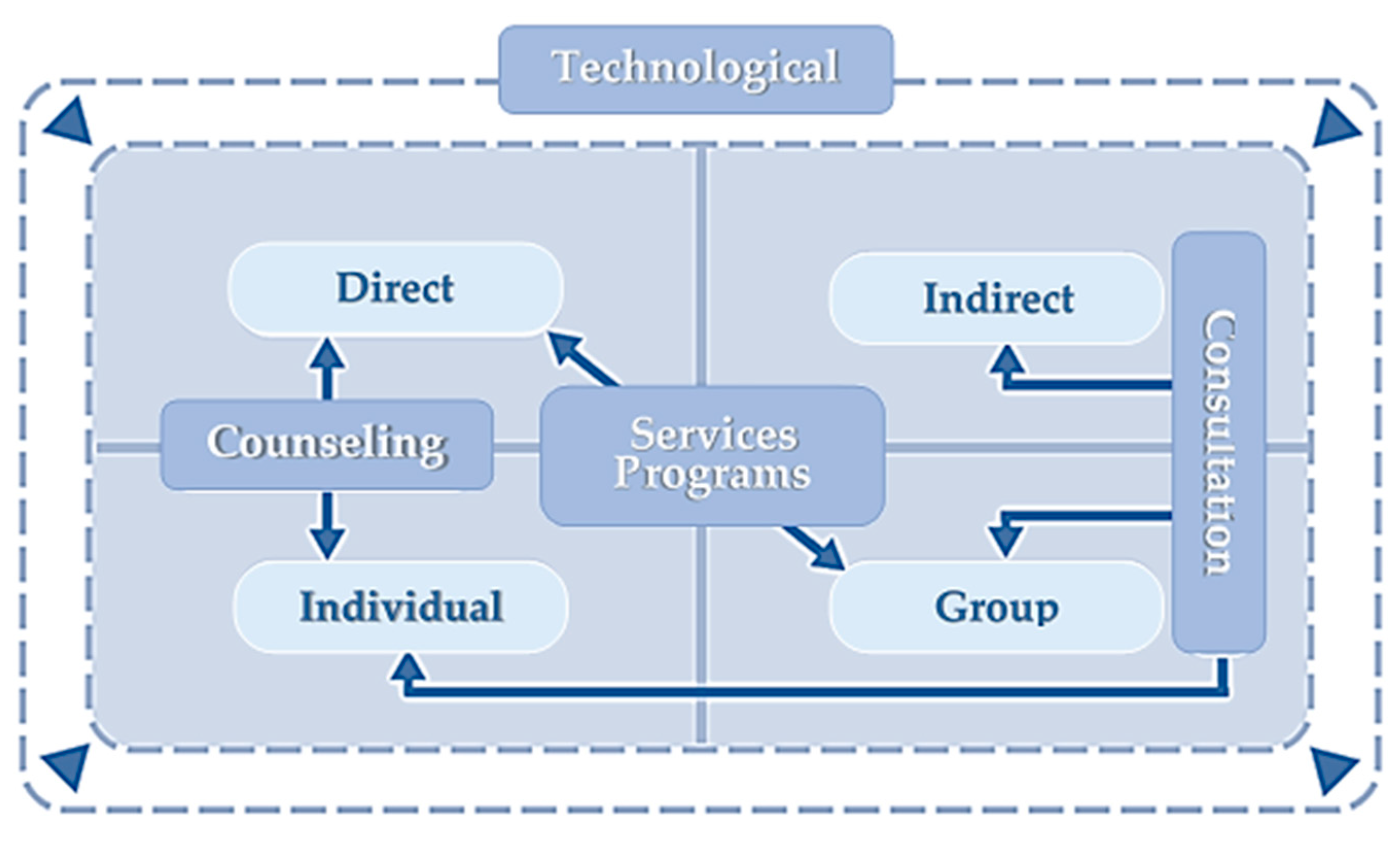

3.1.2. Consultation Model

- The consultation is a relational model, as it includes all the characteristics of the counseling relationship.

- It is a model that promotes information and training of professionals and for professionals.

- It is based on a symmetrical relationship between people or professionals with similar status, in which there is acceptance and respect that favors equal treatment (Figure 2).

- It is a triadic relationship involving three types of agents: consultant, consultant, client (Figure 2).

- The relationship can be established not only with individuals, but also with representatives of services, resources and programs.

- Its objective is to help a third party, which may be an individual or a group (Figure 2).

- It approaches the relationship from different approaches: therapeutic, preventive and developmental.

- The relationship is temporary, not permanent.

- The consultant intervenes indirectly with the client, although, extraordinarily, he may do so directly (Figure 2).

- The consultant acts as an intermediary and mediator between the consultant and the client (Figure 2).

- It is necessary to work with all persons substantially related to the client.

- −

- Adviser (specialist): Works in collaboration with the organization.

- −

- Consultant: Seeks help with the consultant through a systematic process of problem solving, social influence and professional support. In turn assists clients through the selection and application of interventions.

- −

- Clients: People who receive assistance indirectly.

- −

- Objective: to help a third party (person or group).

- −

- It follows the three principles of guidance.

- −

- The relationship is temporary.

- −

- The adviser intervenes indirectly.

- −

- The consultant is a mediator.

- −

- It requires working with all the people substantially related to the client.

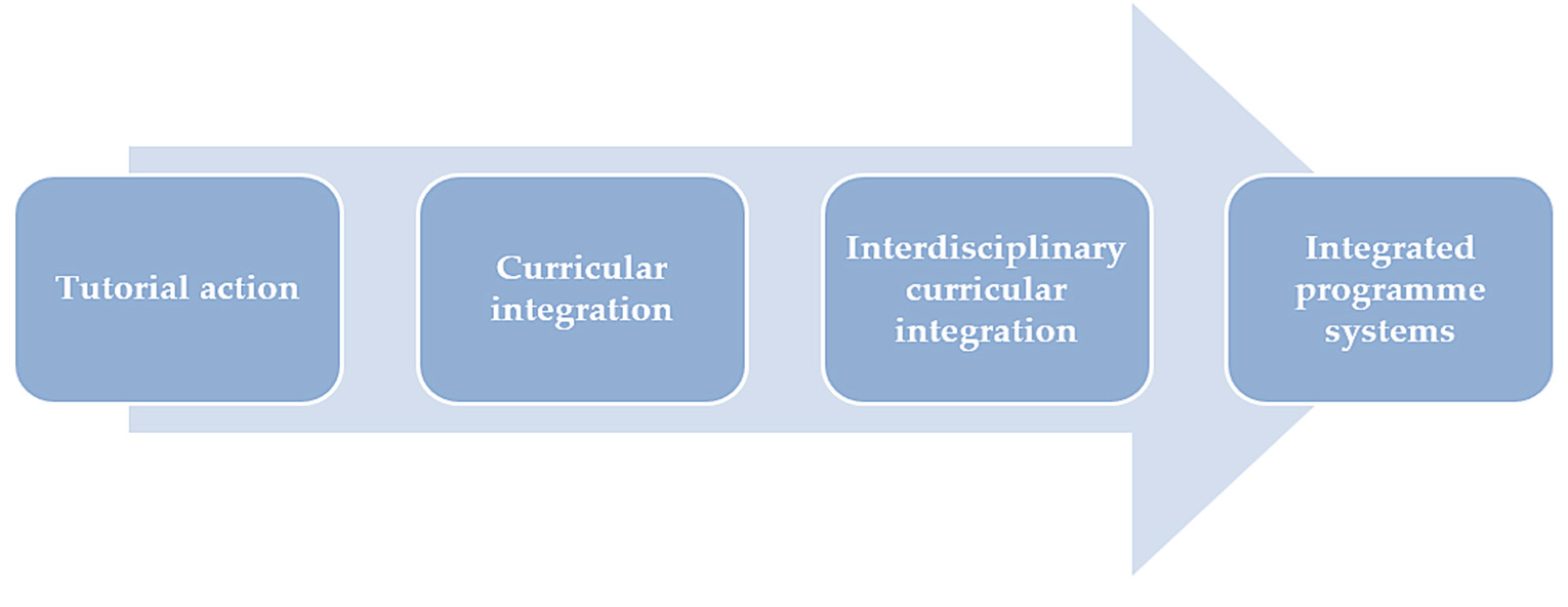

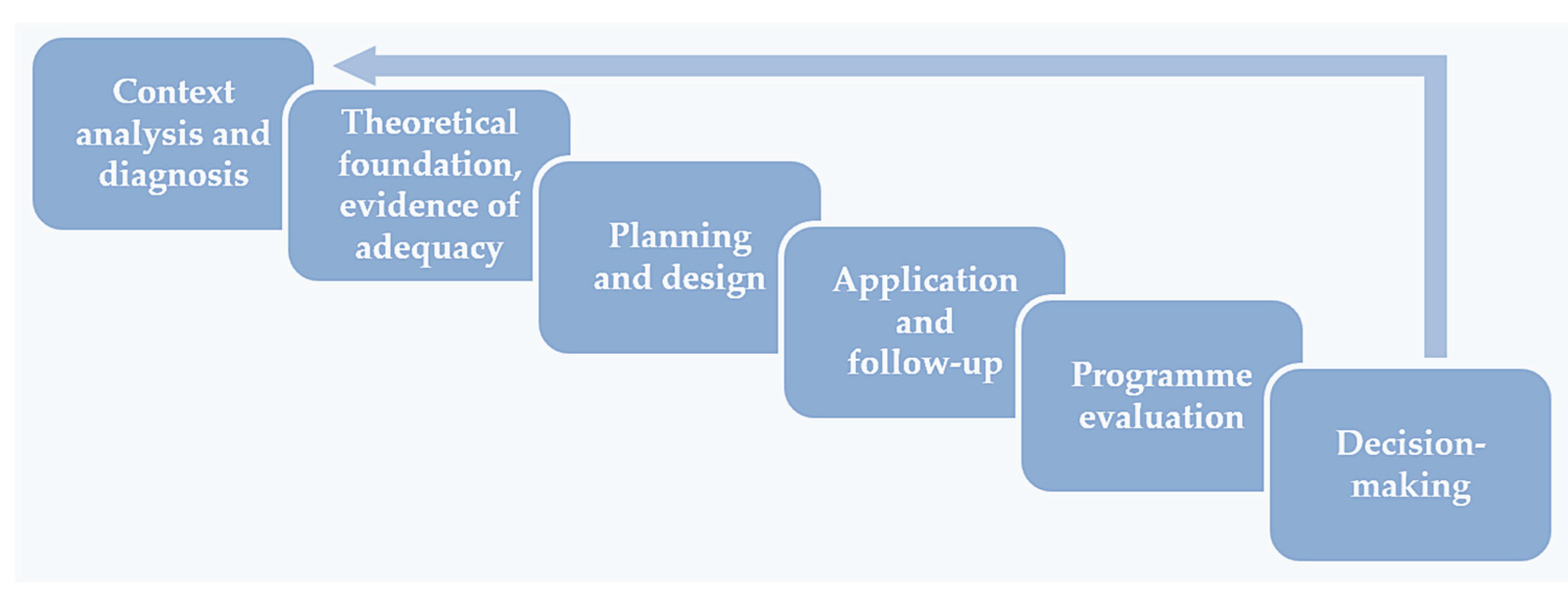

3.1.3. Model Programs

- −

- Analysis of the context, mainly environmental factors, organization, structure, attitudes, etc.

- −

- Identification of needs.

- −

- Formulation of objectives, these must be clear, concrete, concise and operational.

- −

- Program planning, mainly through the sequencing of activities.

- −

- Program development and implementation: of the proposed activities and strategies.

- −

- Evaluation of the program, both of the process and its effectiveness.

- −

- Assessment of program costs. To which could be added, decision making on the improvement, continuity or modification of the program.

3.1.4. Service Model and Service Model Acting by Programs

- −

- Direct intervention by specialists on subjects with a need, difficulty or at-risk situation, focusing on the problem.

- −

- External and sectorial in nature, as they are usually located in specific areas outside educational institutions.

- −

- Corrective intervention, mainly of a therapeutic nature.

- −

- They act mainly on the basis of functions (generally set by the Administration), although there may be objectives.

- −

- The functions of the specialist are mainly evaluation, diagnosis and psycho-pedagogical counseling, information on academic and professional itineraries, support for integration and design and implementation of curricular adaptations and attention to diversity, among others.

- −

- Little connection with the school institution, in addition to a certain lack of knowledge about it.

- −

- Little contextualization of the problems and their own interventions.

- −

- Broad and predefined functions set by the Administration (objectives are forgotten).

- −

- Its approach is mainly therapeutic, neglecting the principles of development and prevention.

- −

- Activities are often limited to diagnosis through the use of psychometric tests.

- −

- Limitations of time, schedule and resources to address the assigned functions and train the teachers who carry out the tutorial action. The timetable, moreover, does not facilitate work with the family and the community.

3.1.5. Technological Model

"This model based on systems and/or self-applicable programs does not eliminate the figure and functions of the counselor. The counselor will have to be present in the process playing the role of consultant, clarifying doubts, solving problems, commenting on some of the information provided and helping the subject in his work of synthesis and reflection. The purpose of these systems is to free the counselor in informative tasks and leave him/her freer to carry out his/her consultation and counseling functions. This model, fully realized, can contribute to the development of the functions of guidance interaction" [23] (p. 191-182).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| ASCA | American School Counselor Association |

References

- Artyukhov, A.; Vasylieva, T.; Artyukhova, N.; Wołowiec, T.; Bogacki, S. SDG 4, Academic Integrity and Artificial Intelligence: Clash or win-win cooperation? Sustainability 2024, 16, 8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Singh, H.; Singh, M.; Singh, J.; Sengupta, E. Sustainable Development Goal for Quality Education (SDG 4): A study on SDG 4 to extract the pattern of association among the indicators of SDG 4 Employing a Genetic Algorithm. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 28, 2031–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. Annual review of population law 1989, 16, 95–501.

- Ammentorp, J.; Ehrensvärd, M.; Uhrenfeldt, L.; Angel, F.; Carlsen, E.B.; Kofoed, P.-E. Can life coaching improve health outcomes? A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res 2013, 13, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdös, T.; Ramseyer, F.T. Change process in coaching: interplay of nonverbal synchrony, working alliance, self-regulation, and goal attainment. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 580351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Mirón, B.; Boronat Mundina, J. Coaching educativo: modelo para el desarrollo de competencias intra e interpersonales. Educación xx1 2014, 17, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. Career coaching in private practice a personal view. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling 2024, 30, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, E.; Nilsson, V.O.; Molyn, J. New findings on the effectiveness of the coaching relationship: time to think differently about active ingredients? Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 2020, 72, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélaz de Medrano, C. Orientación e intervención psicopedagógica. Concepto, modelos, programas y evaluación. Aljibe: Málaga, España; 1998.

- Santana Vega, L.E. Orientación educativa e intervención psicopedagógica. Cambian los tiempos, cambian las responsabilidades profesionales. Pirámide: Madrid, España; 2009.

- Bisquerra, R.; Álvarez González, M. Concepto de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica. En Modelos de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica 1ªed.; Bisquerra Alzina, R., Eds.; Ciss Praxis: Valencia, España; 1998, pp. 9–2.

- Álvarez González, M.; Bisquerra Alzina, R. Orientación educativa: modelos, áreas, estrategias y recursos. Wolters Kluwer: Madrid, España; 2012.

- De la Oliva, D.; Martín Ortega, E.; Vélaz de Medrano, C. Modelos de intervención psicopedagógica en centros de educación secundaria: identificación y evaluación. Infancia y aprendizaje, 2005, 28, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, I.; Martín, E. Un modelo educativo para la orientación y el asesoramiento. En Orientación educativa. Modelos y estrategias de intervención,; Martín Obregon, E., Solé i Gallart, I., Eds.; Grao, Barcelona, España, 2011; pp.13-32.

- Arfasa, A.J.; Weldmeskel, F.M. Practices and challenges of guidance and counseling services in Secondary schools. Emerging Science Journal, 2020, 4, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.G.; Van Esbrroeck, R. New skills for new futures: higher education guidance and counselling services in the European Union. VUBPress: Bruselas, Bélgica; 1997.

- Grañeras Pastrana, M.; Parras Laguna, A. Orientación educativa: fundamentos teóricos, modelos institucionales y nuevas perspectivas. CIDE, Madrid, España, 2009; págs. 123-140.

- Gasparyan, A.Y.; Ayvazyan, L.; Blackmore, H.; Kitas, G.D. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers and editors. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manterola, C.; Rivadeneira, J.; Delgado, H.; Sotelo, C.; Otzen, T. ¿Cuántos tipos de revisiones de la literatura existen? Enumeración, descripción y clasificación. Revisión cualitativa. International Journal of Morphology 2023, 41, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Chacón, J.W.; Barbosa Herrera, J.C.; Rodríguez Villabona, M. Revisión y análisis documental para estado del arte: una propuesta metodológica desde el contexto de la sistematización de experiencias educativas. Investigación Bibliotecológica: Archivonomía, bibliotecología e información, 2013, 27, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausela Herreras, E. Áreas, contextos y modelos de orientación en intervención psicopedagógica. Diálogos educativos, 2006, 12, 16–28, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2473883. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Diéguez, A. La búsqueda de un modelo integrado de Orientación. Revista electrónica de formación de profesorado en comunicación lingüística y literaria 2008, 24, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Espinar, S.; Álvarez, M.; Echeverría, B.; Martín, M.A. Teoría y práctica de la Orientación Educativa. PPV, Madrid, España, 1993, págs.451-478.

- Álvarez Rojo, V. Orientación educativa y acción Orientadora. EOS, Madrid, España, 1994, págs. 98-136.

- Álvarez González, M. Orientación Profesional.; CEDECs, Madrid, España, 1995, págs. 154-178.

- Jiménez, R.; Porras, R. Modelos de acción psicopedagógica entre el deseo y la realidad. Archidona, Sevilla, España 1997, págs. 45-69.

- Bisquerra, R.; Álvarez González, M. Los modelos en orientación. Modelos de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica.; Mc Graw Hill, Madrid, España, 1998, 55–65.

- Sampascual, G.; Navas, L.; Castejón, J.L. Funciones del orientador en primaria y secundaria.; Alianza, Madrid, España, 1999.

- Sobrado, L.; Ocampo, O. Evaluación Psicopedagógica y orientación educativa.; Estel, Valencia, España, 2000.

- Lázaro, A.J.; Mudarra, M.J. Análisis de los estilos de orientación en Equipos Psicopedagógicos. Contextos educativos: Revista de educación, 2000, 3, 253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz Oro, R. Evaluación de programas en orientación educativa.; Pirámide: Madrid, España, 2001; págs. 154-193. [Google Scholar]

- Repetto, E. Modelos de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica. UNED: Madrid, España, 2002; págs. 104-133.

- Martínez Clares, P. La orientación psicopedagógica: modelos y estrategias de intervención. EOS: Madrid, España, 2002; págs. 250-273.

- Martínez González, M.D.C.; Téllez, J.A.; Quintanal, J. La orientación escolar: fundamentos y desarrollo. Dykinson: Madrid, España 2002; pp. 87-121.

- Pantoja, A. La intervención psicopedagógica en la sociedad de la información. EOS Madrid, España, 2004; pp. 147-163.

- Hervás Avilés, R.M. Orientación e intervención psicopedagógica y procesos de cambio. Grupo Editorial Universitaria: Madrid, España, 2006; págs. 286-312.

- Repetto, E. Modelos de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica. UNED: Madrid, España, 2009; págs.163-187.

- Bisquerra, R. Orígenes y desarrollo de la orientación psicopedagógica. Narcea: Madrid, España, 2011; págs.113-140.

- Cano González, R. Orientación y tutoría con el alumnado y las familias. Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, España, 2013; págs. 95-126.

- González-Benito, A. Revisión teórica de los modelos de orientación educativa. RECIE. Revista Caribeña De Investigación Educativa 2018, 2, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavent, J.A.; Fossati, R. El modelo clínico y la entrevista. En Modelos de orientación e intervención psicopedagógica.; Benavent, J.A., Fossati, R., Eds.; EOS: Madrid, España, 1998; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, C.T.; Bedi, R.P. Counsellor behaviours that predict therapeutic alliance: from the client’s perspective. Counselling psychology quarterly 2010, 23, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Carthy, N. No Rapport, No Comment: The relationship between rapport and communication during investigative interviews with suspects. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling 2018, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Bedoya, M. Rapport in police interviews with victims: a linguistic comparison between UK and Spain. Journal of Criminal Psychology 2024, 15, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiniemi, S.; Halinen, A.; Pullins, E.B.; Hosoi, K. Rapport building in B2B sales interactions: the process and explananda. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 2023, 44, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, F.; Enjezab, B.; Ghadiri-Anari, A.; Dehghani, A.; Vaziri, S. The effectiveness of Counseling Based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Body Image and Self-Esteem in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An RCT. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine (IJRM) 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Z. Intervention effect of research-based psychological counseling on adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Psychiatria Danubina 2021, 33, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, G. The theory and practice of mental health consultation. Basic Books:New York, EEUU, 1970, págs. 205-231.

- Giorgi, G.; Arcangeli, G.; Alessio, F.; Mucci, N.; Lulli, L.G.; Bondanini, G.; Lecca, L.I.; Finstad, G.L. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Rey, E. Teorías y modelos explicativos de la Orientación en Educación. En Orientación educativa. Nuevas perspectivas, Sobrado Fernández, L., Fernández Rey, E., and Rodicio García, L., Coords.; ). Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, España, 2013; pp 43-62.

- Bruner, J.S. Desarrollo educativo y educación. Morata: Madrid, España, 1988; pp. 204-219.

- Durán Chacón, M.L. Diseño de una Propuesta Didáctica Basada en la Metodología del Curriculum en Espiral para el Desarrollo de la Competencia Comunicativa de los Estudiantes de Tercer Año de la Carrera de Medicina (Trabajo de Maestría). Universidad Industrial de Santander 2019.

- Heras-Sevilla, D.; Ortega-Sánchez, D.; Rubia-Avi, M. Conceptualización y reflexión sobre el género y la diversidad sexual. Hacia un modelo coeducativo por y para la diversidad. Perfiles educativos 2021, 43, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urruzola, M.J. Educación de las relaciones afectivas y sexuales, desde la filosofía coeducadora. Canal Editora Madrid, España, 1999.

- Tremblay, M.; Currie, C.; Davidson, R.; Burkholder, C.; Morley, K.; Stillar, A.; Baydala, L.; Khan, M. Primary Substance Use Prevention Programs for Children and Youth: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.Y.X.; Tam, W.; Shorey, S. Research Review: Effectiveness of universal eating disorder prevention in-terventions in improving body image among children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2019, 61, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, J.; Perez, J.K.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.L.; Engel, L.; Lee, Y.Y.; Le, P.H.; Le, L.K.-D. . Economic evidence for prevention and treatment of eating disorders: An updated systematic review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 57, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriuso-Ortega, S.; Fernández-Hawrylak, M.; Heras-Sevilla, D. Sex education in adolescence: A systematic review of programmes and meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 2024, 107926. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Liao, J.; He, N.; Hao, Y. Peer education for HIV prevention among high-risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases, 2020, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M.; Escribano, S.; Johnson, B.T.; Lightfoot, M. Interventions to reduce risk for sexually transmitted infections in adolescents: A meta-analysis of trials, 2008-2016. PloS one 2018, 13, e0199421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.C.; Silva, M.; Duarte, C. How is sexuality education for adolescents evaluated? A systematic review based on the Context, Input, Process and Product (CIPP) model. Sex Education 2022, 22, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Banyard, V.L.; Waterman, E.A.; Mitchell, K.J.; Jones, L.M.; Kollar, L.M.M.; Hopfauf, S.; Simon, B. Evaluating the Impact of a Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Program: Youth Leadership Retreat Outcomes. Prevention Science, 2022, 23, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.M.; Embry, V.; Young, B.-R.; Martin, S.L.; Macy, R.J.; Moracco, K.E.; Reyes, H.L.M. Evaluations of Prevention Programs for Sexual, Dating, and Intimate Partner Violence for Boys and Men: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 2019, 22, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Marcos, J.; Nardini, K.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Vives-Cases, C. Listening to stakeholders in the prevention of gender-based violence among young people in Spain: a qualitative study from the positivMasc project. BMC Women’s Health, 2023, 23, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Bonell, C.; Shaw, N.; Orr, N.; Chollet, A.; Rizzo, A.; Rigby, E.; Hagell, A.; Young, H.; Berry, V.; Humphreys, D.K.; Farmer, C. Are school-based interventions to prevent dating and relationship violence and gender-based violence equally effective for all students? Systematic review and equity analysis of moderation analyses in randomised trials. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2023, 34, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.S.; Bouchard, J.; Lee, C. The Effectiveness of College Dating Violence Prevention Programs: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 2021, 24, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, A. El modelo tecnológico de intervención psicopedagógica. REOP-Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 2002, 13, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requejo Fernández, E.; Raposo-Rivas, M.; Sarmiento Campos, J.A. El uso de tecnologías en la orientación profesional: Una revisión sistemática. REOP - Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 2022, 33, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Halili, S.H.; Razak, R.A. Investigating the factors affecting ICT integration of in-service teachers in Henan Province, China: structural equation modeling. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 2023, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Martínez, M.; Llanos-Ruiz, D.; Puente-Torre, P.; García-Delgado, M.Á. Impact of video games, gamification, and game-based learning on sustainability education in higher education. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Herrero, J. Evaluating Recent Advances in Affective Intelligent Tutoring Systems: A Scoping Review of Educational Impacts and Future Prospects. Education Sciences, 2024, 14, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, A.K.; Ilardi, S.S.; Punt, S.E.W.; Nelson, E.-L. Teletherapy Versus In-Person Psychotherapy for Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Telemedicine and E-Health, 2022, 28, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.A.; Zhao, F.; Janis, R.A.; Castonguay, L.G.; Hayes, J.A.; Scofield, B.E. Therapeutic alliance and clinical outcomes in teletherapy and in-person psychotherapy: A noninferiority study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 2023, 34, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, T.L.; Tzeng, J.; Gilbert, M.; Henretty, K.; Padwa, H.; Treiman, K. Addiction Treatment and Telehealth: Review of Efficacy and Provider Insights During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatric Services, 2021, 73, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CRITERIA/STARS | DIMENSIONS | POLES THAT MAKE UP THE PSYCHOPEDAGOGICAL INTERVENTION | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASICS (Theoretical principles) | Concept of human development | Maturation | Development | |

| Purpose of the intervention | Remedial | Development and preventive |

||

| Approach to reality | Linear-causal | Systemic | ||

| Relationship of the counsellor with other professionals or educators | Expert and directive |

Symmetrical and collaborative |

||

| SPECIFIC (specific to the intervention) | Relationship with the target groups of the intervention | Direct | Indirect | |

| Organisation of the intervention | Reactiva | Proactiva | ||

| Locating resources | External | Internal | ||

| Bibliographic search | |

| Review period |

|

| Terms |

|

| Information resources |

|

| Strategies |

|

| Review of documentary sources. | |

| Rules |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Extraction strategies |

|

| Authors/Year/Reference | Counseling | Consultation | Services | Programs | Services by program | Technological |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez Espinar et al. (1993) [23] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Álvarez Rojo (1994) [24] | X | X | X | |||

| Álvarez González (1995) [25] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Jiménez and Porras (1997) [26] | X | X | X | |||

| Bisquerra and Álvarez-González (1998) [27] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Vélaz de Medrano (1998) [9] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Sampascual et al. (1999) [28] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Sobrado and Ocampo (2000) [29] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Lázaro and Mudarra (2000) [30] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Sanz Oro (2001) [31] | X | X | ||||

| Repetto (2002) [32] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Martínez Clares (2002) [33] | X | X | X | |||

| Martínez González et al. (2002) [34] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pantoja (2004) [35] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Hervás Avilés (2006) [36] | X | X | X | |||

| Santana Vega (2009) [10] | X | X | X | |||

| Repetto (2009) [37] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Bisquerra (2011) [38] | X | X | X | |||

| Cano González (2013) [39] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| González Benito (2018) [40] | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Total | 17 | 18 | 11 | 17 | 6 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).