1. Introduction

Divorce is a significant life transition with profound implications for emotional stability, social integration, and economic security. Across diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts, studies have consistently shown that divorced women experience greater financial strain, emotional distress, and social isolation compared to their male counterparts (Amato, 2010; Mortelmans, 2020). While divorce rates have been rising globally, their impact varies based on legal frameworks, family structures, and socio-cultural expectations (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Leopold & Kalmijn, 2016; Forbes, 2022).

In conservative societies like the UAE, divorce often carries stronger financial and social consequences for women, influencing their well-being, mental health, and life satisfaction (Al Gharaibeh & Islam, 2024). However, research on post-divorce experiences in the Middle East remains limited, particularly regarding the economic, emotional, and social realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi.

Research suggests that financial independence is a key determinant of post-divorce well-being, yet many women face economic instability due to career disruptions, caregiving responsibilities, and limited access to financial resources (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Avellar & Smock, 2005). Similarly, emotional distress following divorce is well-documented, as divorced women are more likely to experience mental health struggles, sleep disturbances, and social withdrawal (Sbarra, 2015; Symoens et al., 2013). Co-parenting stress has also been identified as a major contributor to post-divorce dissatisfaction, particularly in cases of custody disputes and unequal parental responsibilities (Emery, 2011; Kelly & Johnston, 2001; Ahadi et al., 2021). Additionally, research highlights that divorced women often face difficulties in social reintegration and forming new relationships, particularly in societies where divorce carries social stigma (Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016).

This study aims to bridge this gap by analysing data from the 5th Cycle Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi, focusing on four major post-divorce challenges: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting difficulties, and challenges in forming new relationships. By examining these factors, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the well-being of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, offering valuable insights for policymakers, social workers, and researchers. Addressing these challenges requires multi-faceted interventions, including financial assistance programs, co-parenting support systems, mental health services, and social reintegration initiatives. Ultimately, this research contributes to a broader discussion on gender, family dynamics, and well-being in post-divorce life, particularly within the socio-cultural context of the UAE.

2. Literature Review

Divorce is a profound life transition with significant implications for economic stability, mental well-being, and social relationships. Research has consistently shown that women face greater economic and social hardships post-divorce, particularly in societies with strong cultural expectations regarding marriage and family structure (Amato, 2010; Mortelmans, 2020; Strizzi et al., 2022). In the UAE, recent studies highlight the complex interplay of financial, emotional, and familial factors influencing divorced women’s well-being (Badri et al., 2023A; Al Gharaibeh & Islam, 2024; Abdollahi et al, 2020). This review synthesizes existing literature through the lens of the key challenges identified in the Abu Dhabi study: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting struggles, and difficulty forming new relationships.

2.1. Financial Consequences of Divorce

One of the most widely documented impacts of divorce is economic instability, particularly for women (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Avellar & Smock, 2005). Women generally experience a steeper decline in income and financial security following marital dissolution due to reduced household income, limited workforce participation, and caregiving responsibilities (Mortelmans, 2020; Lin & Brown, 2021).

The Abu Dhabi study confirmed these patterns, with financial insecurity emerging as the most significant post-divorce struggle, especially for older divorcees and those without a college degree. In high-income societies, financial hardship is often mitigated by government assistance and equitable labor policies, but non-Emirati women in Abu Dhabi may face unique barriers, such as limited access to welfare systems and employment challenges (Badri et al., 2023B). The financial divide between Emirati and non-Emirati divorcees highlights the need for targeted social policies to address financial precarity in this demographic.

2.2. Emotional Well-Being and Mental Health Post-Divorce

Divorce is a known psychological stressor, often linked to increased depression, anxiety, and decreased life satisfaction (Sbarra, 2015; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Studies indicate that women tend to experience greater emotional distress than men, largely due to social stigma, loss of economic security, and caregiving burdens (Symoens et al., 2013; Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016).

Findings from the Abu Dhabi study reinforced these concerns, showing that divorced women facing emotional distress reported lower life satisfaction, poorer sleep quality, and higher digital reliance. The increase in online engagement among these women suggests that social isolation and digital coping strategies play a significant role in their post-divorce experience. Additionally, older divorced women reported greater difficulty forming new relationships, which may contribute to prolonged emotional distress and reduced trust in social networks.

2.3. Co-Parenting Challenges and Child Well-Being

A substantial body of research suggests that co-parenting stress is a major determinant of post-divorce well-being, particularly for women with primary custody of children (Emery, 2011; Kelly & Johnston, 2001; Akpan & Ezeume, 2020). The Abu Dhabi study confirmed that middle-aged women (35-49) reported the highest levels of co-parenting stress, reflecting the challenges of balancing work, childcare, and legal responsibilities.

Studies have also found that the psychological well-being of divorced mothers is strongly correlated with their children's adjustment outcomes (Abdalla & Al-Kaabi, 2021; Kelly & Emery, 2003). In this context, divorced Emirati women reported significantly higher co-parenting stress than non-Emirati women, which may be linked to stronger cultural and familial expectations regarding motherhood. These findings suggest that targeted co-parenting programs and legal reforms could alleviate some of these burdens.

2.4. Social Reintegration and the Challenge of New Relationships

Social reintegration post-divorce remains a significant challenge for many women, especially in conservative societies where divorce carries stigma (Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000). Research has shown that women face greater barriers in forming new relationships due to social norms, self-esteem issues, and economic dependency (Slanbekova et al., 2017; Greene et al., 2015; Kaleta & Mróz, 2023).

The Abu Dhabi study highlighted that difficulty in starting a new relationship was particularly pronounced for older divorcees, suggesting that age, financial independence, and social perceptions significantly influence post-divorce dating opportunities. Additionally, the study found increased religious engagement among women facing social stigma and emotional distress, possibly as a coping mechanism. Similar findings in Western and Middle Eastern contexts suggest that religion plays a critical role in post-divorce identity reconstruction (Kalmijn, 2018; Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016; Badri et al., 2024).

2.5. Divorce and Well-Being in the Abu Dhabi Context

Existing research on well-being in Abu Dhabi has shown that financial stability, mental health, and social trust are key determinants of overall quality of life (Badri et al., 2023A, 2023B; Bianchi & Spain, 2020). These studies reinforce the results of this research, which demonstrated that financial pressures, emotional distress, and social isolation significantly lower life satisfaction among divorced women.

The impact of divorce on well-being is not uniform and varies significantly based on demographic factors such as gender, age, education, and parental status. Research has consistently shown that women experience greater financial and emotional hardships post-divorce than men, largely due to economic dependency, caregiving responsibilities, and societal expectations (Mortelmans, 2020; Kalmijn & Uunk, 2007). Studies in the Middle East further emphasize that divorced women often face stronger social stigma and fewer economic opportunities, compared to their male counterparts, which exacerbates their post-divorce challenges (Al Gharaibeh & Islam, 2024; Badri et al., 2023).

Age also plays a crucial role in post-divorce adaptation. Younger divorcees (20-34) often exhibit greater resilience and social reintegration capacity, as they are more likely to re-enter the workforce or form new relationships (Amato, 2010; Lin & Brown, 2021). In contrast, older divorced individuals (50+) experience heightened financial strain and social isolation, particularly if they were financially dependent on their spouses before the divorce (Kim & DeVaney, 2003; Badri et al., 2024). Findings from Abu Dhabi reinforce this pattern, as financial insecurity and relationship difficulties were more pronounced among older divorced women.

Education serves as a key protective factor in post-divorce well-being. Higher educational attainment is associated with better financial independence, stronger coping mechanisms, and increased life satisfaction post-divorce (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Leopold & Kalmijn, 2016). The Abu Dhabi study found that women without a college degree were significantly more affected by financial pressures and co-parenting difficulties, reinforcing global findings that higher education serves as a buffer against post-divorce instability (Avellar & Smock, 2005; Badri et al., 2023).

Another critical factor is parental status, particularly the number of children. Divorce research highlights that women with multiple children experience higher stress levels, greater financial burdens, and more difficulties in post-divorce social and romantic reintegration (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Symoens et al., 2013, Apata et al., 2023). The Abu Dhabi study supports these findings, showing that women with five or more children reported the lowest life satisfaction scores, particularly when dealing with financial insecurity. Co-parenting stress was most pronounced among middle-aged women (35-49) with multiple children, reflecting the dual burden of economic survival and childcare responsibilities (Emery, 2011; Kelly & Johnston, 2001).

Badri et al. (2024) emphasized that mental well-being in Abu Dhabi is strongly shaped by socio-cultural factors, particularly family structure and financial independence. This aligns with the current study’s findings that financial insecurity and co-parenting challenges were the strongest predictors of low well-being among divorced women. Furthermore, Badri et al. (2023) found that trust in social networks was a key determinant of subjective happiness in Abu Dhabi, a factor that was also evident in this study, where divorced women with lower social trust reported lower life satisfaction.

This literature review integrates global research with findings from the Abu Dhabi study to provide a context-specific understanding of post-divorce well-being. While divorce impacts economic security, mental health, and social integration across different cultures, the severity of these challenges varies depending on socio-cultural norms, financial systems, and legal structures. The Abu Dhabi study highlights the need for financial policies, mental health support, and co-parenting assistance to address the key challenges faced by divorced women in the region.

Future research should explore longitudinal changes in well-being post-divorce and examine gender differences in divorce outcomes, particularly regarding economic independence, emotional resilience, and remarriage trends. By refining legal and social policies, Abu Dhabi can create a more supportive environment for divorced women, enabling them to rebuild their lives with financial security, social belonging, and emotional stability.

3. Methods and Analysis

3.1. Survey Instrument and Items

The study is based on data from the 5th Cycle Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi, a comprehensive survey conducted to assess well-being indicators across multiple domains. The dataset includes responses from divorced women residing in Abu Dhabi, providing insights into their economic, social, and emotional challenges post-divorce. The survey employs a structured questionnaire covering key well-being determinants, including:

Life Satisfaction (0-10 scale, where 0 = Not at all satisfied, 10 = Completely satisfied)

Happiness (0-10 scale, where 0 = Not at all happy, 10 = very happy)

Subjective Health (1-5 scale, where 1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent)

Financial Security (composite of three items (Ability to pay for necessary expenses, satisfaction with household income, and income comparisons with other families). All rated on a 1-5 scale. The computed reliability Alpha is (0.8681)

Mental Health and Emotional Well-Being (Composite score derived from indicators such as stress levels, sleep quality, and frequency of negative emotions). The computed reliability Alpha is (0.8926).

Relations with the family and friends (both items use a satisfaction scale (1-5: not satisfied at all to highly satisfied)

Practicing religion (1-5 scale, where 1 = not at all, 5 = Always)

Social trust (trust in others) 1-5 scale, where 1 = not trusted at all, 5 = high trusted.

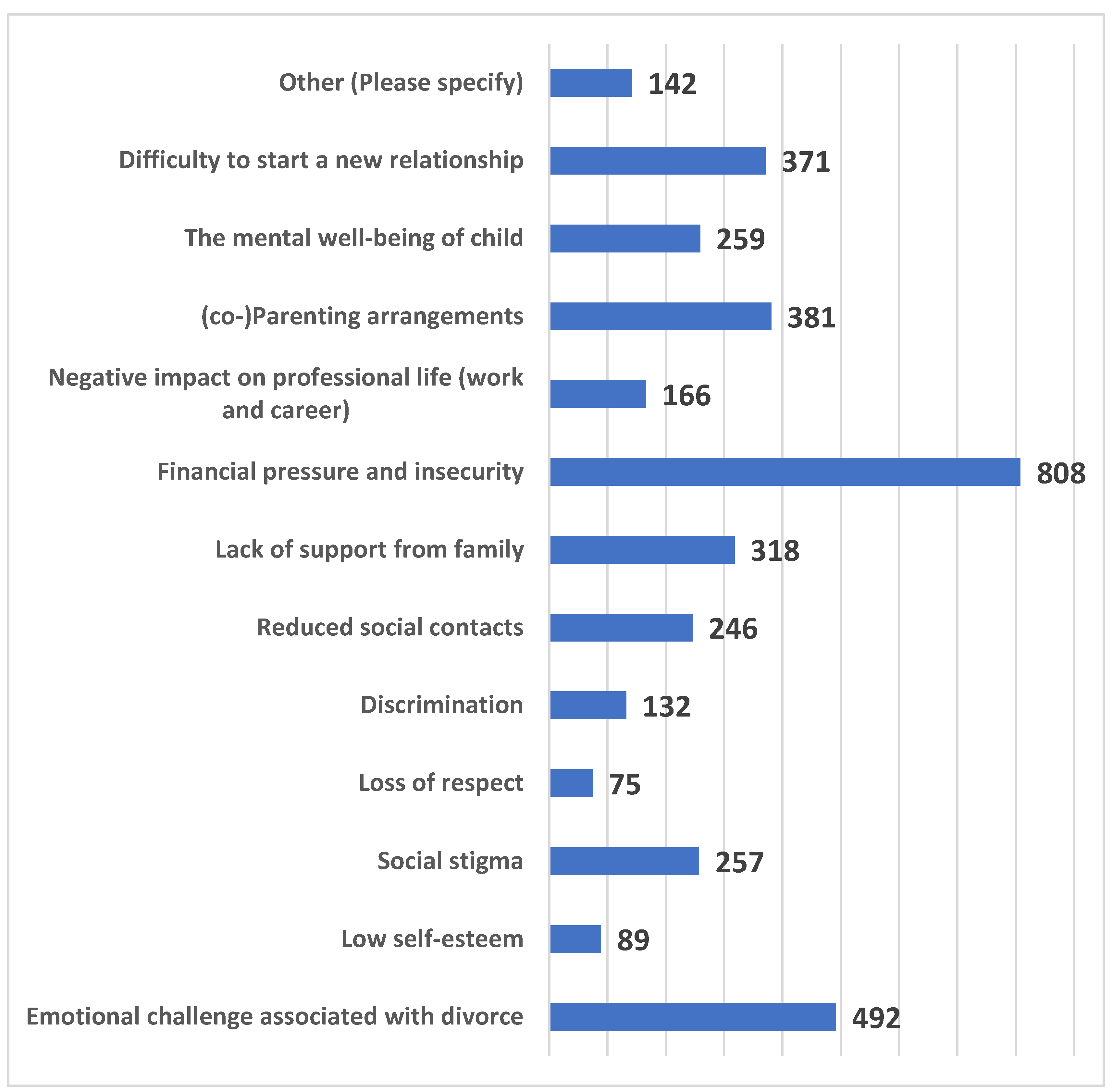

Post divorce challenges (divorced women were asked to select five biggest challenges that you have faced in your post-divorce life? Please see figure 1 for the choices)

Housing (residence) satisfaction (scale 1-5: not satisfied at all, to very satisfied).

Hours spent online (self-writing - hours spent online).

To enhance comparative analysis, respondents were also categorized by age groups (20-24, 25-29, etc.), educational attainment (college degree or not), nationality (Emirati vs. Non-Emirati), and number of children (0, 1-2, 3-4, etc.). The dataset includes demographic controls such as employment status, housing conditions, and digital engagement.

3.2. Analytical Methods

To analyse the relationship between divorce-related challenges and well-being outcomes, the study employs a combination of descriptive statistics, ANOVA tests, and regression analysis. Mean scores are reported for key well-being indicators across different subgroups. One-way ANOVA is used to examine statistically significant differences in life satisfaction, mental well-being, and financial security across demographic categories (age, education, nationality, number of children). Post hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD) are applied where significant differences are detected to identify which groups differ from each other.

3.3. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in the Stress Process Model (Pearlin et al., 1981), a widely used framework for understanding how stressors, coping mechanisms, and socio-economic resources shape well-being outcomes. The model posits that life transitions such as divorce act as primary stressors, which can lead to secondary stressors (e.g., financial instability, social disconnection, co-parenting difficulties) that exacerbate negative well-being outcomes. According to Pearlin et al. (1981), the extent to which individuals adapt to stressors depends on personal resources (education, financial independence), social support (trust in others, social integration), and coping strategies (religion, digital engagement, or therapy). This framework is particularly relevant to the Abu Dhabi study, as the findings reveal that:

Financial insecurity serves as a primary stressor, leading to reduced life satisfaction and mental well-being.

Co-parenting stress functions as a secondary stressor, significantly affecting middle-aged women (35-49 years old).

Emotional distress is exacerbated by social stigma and difficulty forming new relationships, reinforcing feelings of isolation.

Religious engagement and digital interaction emerge as coping mechanisms, particularly for women experiencing social exclusion.

The Stress Process Model provides a valuable lens through which the multi-dimensional impacts of divorce can be understood, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis of the emotional, social, and economic challenges faced by divorced women in Abu Dhabi.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents

The 5th Cycle Quality of Life Survey in Abu Dhabi received responses from 100,048 individuals, of whom 4,347 were divorced women, accounting for 4.3% of the total sample (

Table 1). The sample of divorced women in the Quality-of-Life Survey includes a diverse range of respondents in terms of age, nationality, region, and education level. Most divorced women fall within the 40-44 age group (923 respondents), followed by 35-39 (768 respondents) and 45-49 (811 respondents). Fewer respondents were aged 20-24 (32 respondents), indicating that divorce is less common among younger women. The numbers gradually decline after 50, reflecting lower divorce rates or potential remarriage among older age groups. Emirati women (3,271 respondents) make up most of the sample, while non-Emirati women (1,076 respondents) account for a smaller proportion. This suggests that cultural and legal factors in Abu Dhabi may influence the likelihood of divorce among Emirati and non-Emirati women differently. The sample is almost evenly split between women with a college degree or higher (2,141 respondents) and those with education below a college degree (2,206 respondents). This indicates that educational attainment does not significantly differentiate divorced women in this study, meaning that both highly educated and less-educated women experience divorce at similar rates.

4.2. Divorce Challenges Reported by Women

Figure 1 illustrates the biggest challenges faced by divorced women in Abu Dhabi, as reported in the Quality-of-Life Survey. Respondents were asked to select up to five of their most significant post-divorce difficulties. The data highlights four key challenges that had substantially higher response rates compared to others. Financial pressure and insecurity (808 respondents) were the most frequently cited challenge, indicating that economic struggles are a major stressor for divorced women, affecting their ability to meet daily expenses and maintain financial stability. Emotional challenges associated with divorce (492 respondents) reflects that divorce takes a significant emotional toll, with nearly one in ten divorced women in the survey reporting emotional distress, stress, and mental health struggles as a primary issue. Co-Parenting arrangements (381 respondents) focuses on managing child custody and responsibilities post-divorce that presents a major challenge, highlighting the complications of shared parenting, legal arrangements, and child well-being. Difficulty starting a new relationship (371 respondents) reflects that a considerable number of women expressed challenges in forming new relationships, possibly due to social stigma, emotional readiness, or lack of trust post-divorce.

These four challenges were reported by far more respondents than other difficulties (e.g., discrimination, loss of respect, low self-esteem, etc.), making them the most relevant for analysis. These challenges span financial, emotional, social, and familial aspects, covering the core dimensions of well-being. Addressing financial insecurity, mental health, co-parenting struggles, and social reintegration can lead to meaningful policy recommendations for supporting divorced women in Abu Dhabi. By focusing on these four challenges, the study will provide a clearer, more impactful analysis, ensuring that the results are both statistically strong and practically relevant.

4.3. Well-Being Determinants Among Divorced Respondents

Table 2 presents the descriptive means of well-being determinants for divorced women in Abu Dhabi, categorized by the four key challenges they reported: emotional challenges, financial pressures and insecurity, co-parenting arrangements, and difficulty starting a new relationship. Financial struggles have the most negative impact on well-being. Women facing financial pressures reported the lowest life satisfaction (5.63) and lowest satisfaction with household income (2.34) compared to the other groups. Their ability to pay for necessary expenses (1.91) was also significantly lower, highlighting the direct impact of economic hardship post-divorce. The results in the table also show that mental health is significantly affected. For example, composite mental health scores were highest (3.09) for those experiencing financial pressures, meaning these women had worse mental well-being than others. Isolation was also notable, with higher scores among those facing low self-esteem (3.11) and emotional challenges (2.84), reinforcing the connection between mental health and social interactions. We note that life satisfaction and happiness vary by challenge type. Women facing financial insecurity had the lowest life satisfaction (5.63), whereas those with less severe post-divorce struggles reported higher scores (6.94). Similarly, happiness scores were lowest among those experiencing financial pressures (7.28) compared to higher happiness scores (7.77) in the general Abu Dhabi divorced population. We also note that religious practice and digital engagement trends are affected. Women who felt social stigma or discrimination reported higher religious practice (4.65), suggesting that religion may serve as a coping mechanism for some. Hours spent online (6.87) were highest among those struggling with low self-esteem, social stigma, and difficulty starting new relationships, indicating increased reliance on digital spaces for social or emotional support.

4.4. Divorce Impacts, Well Beings and Age

Table 3 presents ANOVA results, examining life satisfaction differences across age categories of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, based on the four key challenges they faced. Only statistically significant outcomes (p < 0.05) are shown, highlighting where age-related variations are meaningful. Financial pressures have the strongest negative impact, especially on older divorcees. Life satisfaction was significantly lower (p < 0.001) among divorced women aged 50 and above who reported financial insecurity. This might suggest that older women face greater economic difficulties post-divorce, likely due to limited work opportunities and financial dependence before divorce. Meanwhile, Emotional challenges are more severe for younger and middle-aged women. We note that women aged 30-44 who reported emotional challenges had significantly lower life satisfaction scores (p = 0.004) than older age groups. This indicates that younger and middle-aged divorced women may struggle more with emotional distress, possibly due to higher social expectations, parenting pressures, and career disruptions. Results also show that co-parenting challenges impact middle-aged women most (35-49 years old). Women aged 35-49 had the lowest life satisfaction (p = 0.002) among those struggling with co-parenting responsibilities. This reflects the heightened stress of balancing work, custody arrangements, and family responsibilities during these prime parenting years. Finally, difficulty in starting a new relationship affects women across all age groups, but more for older women (50+). Older women (50+) reported significantly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.007) when struggling with starting new relationships. This may be due to limited social opportunities, cultural expectations, and reduced confidence in re-entering the dating world post-divorce.

4.5. Divorce Impacts and Number of Children

Table 4 presents ANOVA results, examining how life satisfaction varies based on the number of children among divorced women in Abu Dhabi. The scale ranges from zero children to seven or more children. Overall impact is less pronounced compared to age-based differences. The number of children has a weaker influence on life satisfaction compared to age-related differences observed in

Table 3. However, certain statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) do emerge, particularly regarding financial pressures and co-parenting challenges. For example, financial pressures are more severe for women with more children (5 or More). Women with five or more children reported the lowest life satisfaction scores (p = 0.021) when facing financial insecurity. This highlights the economic burden of raising multiple children post-divorce, particularly in terms of housing, education, and daily expenses. We also note that co-parenting challenges are more impactful for women with 3-6 children. Women with 3-6 children reported significantly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.039) when dealing with co-parenting difficulties. This suggests that balancing custody arrangements and parenting responsibilities becomes more complex as the number of children increases. Interestingly, women with only one or two children were less affected, possibly due to simpler custody and caregiving arrangements. We also note that emotional challenges and relationship difficulties show no strong trends. Unlike financial and co-parenting issues, emotional distress and difficulties in starting new relationships did not show significant differences based on the number of children. This suggests that emotional struggles and social reintegration may be more universally experienced among divorced women, regardless of their number of children.

4.6. Divorce Impacts for Emiratis and Non-Emirati Divorced Women

Results in

Table 5 show that financial pressures have a greater negative impact on Non-Emirati Women. Non-Emirati divorced women reported significantly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.017) when experiencing financial insecurity. This might suggest that non-Emirati women may have fewer economic safety nets, as they are less likely to have access to social benefits, family support, or long-term financial security in the UAE. We also note that co-parenting challenges have a stronger impact on Emirati women. Emirati women reported significantly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.032) when dealing with co-parenting difficulties. Such outcomes may be due to greater social expectations regarding parental roles and the complexity of custody arrangements within Emirati family structures. Emotional challenges and relationship difficulties show no major differences. Emotional struggles and difficulties in starting new relationships did not significantly vary between Emirati and non-Emirati women. This suggests that psychological and social adjustment post-divorce is a universal challenge, regardless of nationality.

Table 7 presents ANOVA results, examining how life satisfaction varies between divorced women with and without a college degree in Abu Dhabi. The table includes only statistically significant findings (p < 0.05), highlighting key differences in well-being based on educational background. Results show that financial pressures have a greater negative impact on women without a college degree. Divorced women without a college degree reported significantly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.009) when experiencing financial insecurity. This suggests that higher education provides better financial stability and career opportunities, reducing the economic burden post-divorce. Women with college degrees may have more access to jobs, financial independence, and social mobility, helping them cope better with financial pressures. Results also show that co-parenting challenges affect both groups but are slightly more stressful for less educated women. We note that women without a college degree had lower life satisfaction scores (p = 0.031) when facing co-parenting difficulties. This may be due to fewer resources or support networks available for handling custody, childcare, and co-parenting arrangements. Results also show that emotional challenges and relationship difficulties show some differences. Women without a college degree reported slightly lower life satisfaction (p = 0.044) when struggling with emotional challenges, though the gap was smaller than for financial issues. Difficulty in starting new relationships was also more pronounced among less-educated women (p = 0.027), possibly due to lower self-confidence, social stigma, or economic constraints limiting opportunities for social engagement.

While this study primarily focused on four key post-divorce challenges—financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting difficulties, and struggles in starting new relationships—other significant findings emerged across multiple well-being determinants. Several additional well-being indicators demonstrated statistically significant variations, reinforcing the complex and multi-dimensional impact of divorce on women in Abu Dhabi. Notably, subjective health varied significantly among divorced women, with those experiencing financial insecurity and emotional distress reporting lower self-rated health scores (p < 0.05). Similarly, sleep quality was negatively affected, particularly for women struggling with co-parenting challenges and financial pressures, suggesting that economic and parental stress contribute to poorer rest and recovery. Social trust and interactions were also impacted, as women facing emotional struggles and difficulties in starting new relationships were more likely to report lower levels of trust in others (p < 0.05) and reduced frequency of social meetings. Furthermore, religious practice emerged as a significant factor for certain subgroups. Women who reported social stigma or difficulty forming new relationships were more likely to engage in religious activities more frequently, possibly as a form of coping mechanism or spiritual support. Online engagement also varied, with women struggling with emotional distress and social isolation spending significantly more time online (p < 0.05), potentially reflecting increased digital reliance for socialization and emotional escape.

These findings highlight the broad and interconnected nature of post-divorce well-being determinants, demonstrating that financial, emotional, and social factors interact in shaping the overall life satisfaction of divorced women. While the study primarily focuses on the four main challenges, these additional significant results provide a deeper understanding of how divorce affects various dimensions of well-being.

5. Discussions

This study provides an in-depth examination of the emotional, social, and economic realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, focusing on four major post-divorce challenges: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting difficulties, and struggles in forming new relationships. The findings highlight the complex interplay between economic status, mental well-being, social networks, and demographic factors, underscoring the diverse and multifaceted consequences of divorce.

The economic consequences of divorce are well-documented in global research (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Mortelmans, 2020), and the findings from Abu Dhabi reinforce this trend. Financial insecurity emerged as the strongest predictor of lower life satisfaction, with women facing financial struggles reporting poorer subjective health, increased emotional distress, and reduced social engagement. This aligns with economic dependency theory, which argues that individuals who lack financial autonomy suffer greater post-divorce disadvantages (Avellar & Smock, 2005). In this study, non-Emirati women were disproportionately affected by financial insecurity, suggesting that limited access to social safety nets and fewer employment opportunities exacerbate their economic vulnerability. Conversely, Emirati women may have stronger family-based financial support mechanisms, mitigating some economic hardships.

Divorce is often associated with higher stress levels, increased anxiety, and lower self-esteem (Sbarra, 2015; Symoens et al., 2013). The results of this study confirm that women experiencing emotional distress post-divorce reported lower life satisfaction, poorer sleep quality, and greater reliance on digital engagement likely as a coping mechanism. Interestingly, age played a significant role in emotional adjustment. Middle-aged women (30-44) exhibited the highest levels of emotional distress, possibly due to balancing career pressures, childcare responsibilities, and societal expectations. Older women (50+) reported lower distress levels, though they faced greater struggles with social reintegration and financial pressures. This supports prior research suggesting that younger individuals are more likely to experience psychological distress immediately after divorce, while older divorcees struggle with long-term adjustment issues (Lin & Brown, 2021).

A notable finding was the increased religious engagement among emotionally distressed women, particularly those struggling with social stigma and relationship difficulties. Similar trends have been observed in divorce studies, where religious involvement serves as a coping mechanism, providing emotional stability and social belonging (Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016; Badri et al., 2024). This suggests that community-based mental health and counseling programs that incorporate cultural and religious dimensions could be effective in supporting divorced women.

Consistent with research on co-parenting stress (Kelly & Johnston, 2001; Emery, 2011), this study found that middle-aged women (35-49) reported the greatest difficulty in balancing co-parenting responsibilities, reflecting the strain of custody arrangements, financial dependence, and childcare obligations. The stress of co-parenting was more pronounced among Emirati women, suggesting that cultural expectations regarding maternal responsibility contribute to post-divorce burdens. This aligns with findings from Middle Eastern studies indicating that custodial mothers often bear a disproportionate caregiving and financial burden after divorce (Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2000; Al Gharaibeh & Islam, 2024).

The findings suggest that divorced women face significant challenges in re-entering social life and forming new relationships, particularly older women and those with multiple children. This is consistent with research indicating that social stigma, self-esteem issues, and economic concerns limit women’s ability to establish new romantic relationships (Slanbekova et al., 2017; Greene et al., 2015). Women facing difficulty in starting new relationships also reported lower trust in others, reinforcing the idea that social disconnection contributes to prolonged emotional distress. Notably, non-Emirati women reported fewer relationship struggles, possibly due to greater social flexibility in their cultural backgrounds compared to Emirati women, who may face stronger social and familial expectations regarding remarriage.

Age has been identified as a major determinant of post-divorce adjustment, with younger women typically exhibiting greater resilience and older women experiencing more economic and social difficulties (Amato, 2010; Lin & Brown, 2021). Older divorced women (50+) faced greater financial struggles and social reintegration difficulties, consistent with research highlighting lower workforce participation and reduced remarriage prospects among older divorcees (Kim & DeVaney, 2003). Younger divorced women (20-34) exhibited higher emotional distress, which may be due to adjustment struggles, social stigma, or lack of financial independence (Sbarra, 2015).

Education is widely recognized as a protective factor that enhances financial independence and coping mechanisms post-divorce (McManus & DiPrete, 2001; Leopold & Kalmijn, 2016). The study found that women without a college degree were significantly more affected by financial pressures and co-parenting challenges, aligning with research suggesting that lower educational attainment limits post-divorce economic opportunities (Avellar & Smock, 2005). In Abu Dhabi, higher education appears to act as a financial buffer, with college-educated women reporting better financial stability and slightly lower emotional distress than their less-educated counterparts. However, the study also highlights that even college-educated women face social reintegration challenges, reinforcing findings that divorce stigma and relationship difficulties persist across educational levels (Greene et al., 2015).

Nationality emerged as a key differentiator in post-divorce experiences, particularly in financial security and co-parenting challenges. Non-Emirati women faced greater financial insecurity, likely due to limited access to social safety nets and employment protections, a trend also observed in studies on migrant divorcees in the Gulf region (Al Gharaibeh & Islam, 2024). Emirati women, on the other hand, reported significantly higher co-parenting stress, possibly due to stronger cultural expectations around maternal responsibility (Badri et al., 2023). The study aligns with international findings that migrant divorcees often struggle with weaker legal protections and economic security, requiring tailored support policies to address these disparities (Slanbekova et al., 2017).

Parental responsibilities play a critical role in shaping post-divorce life satisfaction, with greater caregiving demands often translating into higher financial and emotional stress (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Symoens et al., 2013). Women with five or more children reported the lowest life satisfaction, particularly in relation to financial pressures and co-parenting difficulties, reinforcing findings that greater parental burdens increase post-divorce economic vulnerability (Emery, 2011). Women with 3-4 children had the highest co-parenting stress, likely due to custody disputes and the challenge of balancing work and childcare (Kelly & Johnston, 2001). Interestingly, women with one or two children experienced fewer financial and emotional struggles, suggesting that lower parental responsibilities may ease the post-divorce transition.

In general, the results strongly align with Pearlin et al.'s (1981) Stress Process Model, which posits that life stressors (e.g., financial instability, emotional distress, co-parenting struggles) are mediated by personal and social resources. The findings support this theory in multiple ways. First, financial insecurity functions as a primary stressor, with education and employment status acting as moderating factors. Second, co-parenting stress serves as a secondary stressor, especially for middle-aged women, increasing overall emotional burden. Third, religious engagement and digital interactions emerge as coping mechanisms to mitigate stress and enhance emotional well-being. This confirms that divorce outcomes are not uniform but rather shaped by individual circumstances, cultural context, and access to coping resources.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth examination of the emotional, social, and economic realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, focusing on four major post-divorce challenges: financial insecurity, emotional distress, co-parenting difficulties, and struggles in forming new relationships. The findings reveal that these challenges significantly impact various well-being determinants, with financial pressures emerging as the most detrimental factor. Women facing financial insecurity reported the lowest life satisfaction scores, poorer subjective health, and increased mental distress, particularly among older divorcees and those without a college degree.

Age and education level played a notable role in shaping post-divorce experiences. Middle-aged women (35-49 years old) struggled the most with co-parenting responsibilities, balancing child-rearing with career obligations. Older divorcees (50+) reported the greatest financial struggles and the lowest likelihood of forming new relationships, indicating potential social and economic vulnerabilities in later life. Additionally, non-Emirati women were disproportionately affected by financial insecurity, likely due to fewer social safety nets and legal protections, while Emirati women faced greater co-parenting stress, reflecting the complex family dynamics within the local cultural context.

Beyond economic and parenting difficulties, emotional well-being and social connectedness were significantly impacted. Women struggling with emotional distress and relationship difficulties reported lower life satisfaction, reduced social trust, and greater reliance on digital platforms for engagement. Interestingly, religious practices appeared to be a coping mechanism, with women facing social stigma and relationship difficulties engaging more frequently in religious activities. These findings highlight the multi-dimensional nature of post-divorce adjustment, where economic, social, and psychological factors interact in shaping overall well-being.

The study's insights provide a critical foundation for understanding the unique struggles of divorced women in Abu Dhabi and emphasize the need for comprehensive social, economic, and psychological support systems to assist them in navigating post-divorce life.

Despite providing valuable insights into the emotional, social, and economic realities of divorced women in Abu Dhabi, this study has several limitations. First, the findings are based on self-reported survey responses, which may be influenced by subjective perceptions and response biases. Second, the study focuses only on divorced women, meaning that comparisons with divorced men or those in different marital statuses were not explored. Additionally, while the research highlights key well-being determinants, it does not account for longitudinal changes in post-divorce adjustment over time.

From a policy perspective, the findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to support divorced women in Abu Dhabi. Financial assistance programs, job training initiatives, and affordable housing solutions could help mitigate the negative economic impact of divorce, particularly for those without a college degree. Psychosocial counselling services and community-based support networks are also critical to addressing emotional well-being and social reintegration. Furthermore, reforming co-parenting policies and legal frameworks could ease the burden of custody arrangements and improve the quality of life for divorced mothers.

For future research, several directions can be pursued to deepen the understanding of post-divorce well-being. Comparative studies examining the experiences of divorced men and women could provide a gender-based perspective on post-marital challenges. Additionally, longitudinal research tracking well-being indicators over time would help identify long-term adaptation patterns post-divorce. Further exploration into cultural and legal factors influencing post-divorce experiences in the UAE and similar societies could provide context-specific policy recommendations. By expanding the scope of research, policymakers and scholars can develop more effective and inclusive support systems for individuals navigating post-divorce life.

Funding

This work has been conducted and supported by research offices in the Department of Community Development and Statistics Centre Abu Dhabi. There was no funding provided to conduct this research.

Informal consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the Quality-of-Life Survey in Abu Dhabi. The survey was conducted in accordance with ethical research guidelines, and respondents were informed about the purpose of data collection, confidentiality, and their right to withdraw at any time. For adolescent participants (aged 15-19), consent was also obtained from their legal guardians where applicable.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Abu Dhabi Department of Community Development. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Committee of the Department of Community Development, United Arab Emirates has granted approval for this study (Ref. No. OUT/065/2024). The research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable when human participants are involved (Declaration of Helsinki).

Use of AI Assistance

This research paper benefited from the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to support the drafting, editing, and refinement of text. AI assistance was used under the supervision of the lead researcher to enhance clarity, consistency, and organization of content. All data analysis, interpretation, and intellectual insights remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

References

- Abdalla, F. M., & Al-Kaabi, A. A. (2021). Divorce and its psychological impacts in the UAE: An exploratory study. Arabian Journal of Social Studies, 8(2), 15-35.

- Abdollahi, A., Ahadi, H., Tajeri, B., & Haji Alizadeh, K. (2020). Analysis of the experience of divorce from the perspective of divorced couples in Tehran. Women's Strategic Studies, 23(89) (Autumn 2020), 143-162.

- Ahadi, H., Tajeri, B., & HajiAlizadeh, K. (2021). Developing a conceptual model of the factors forming divorce in the first five years of life: a grounded theory study. Journal of psychological science, 20(97), 1-12.

- Akpan, I. J., & Ezeume, I. C. (2020). The challenges faced by parents and children from divorce. Challenge, 63(6), 365-377.

- Al Gharaibeh, F., & Islam, M. R. (2024). Divorce in the Families of the UAE: A Comprehensive Review of Trends, Determinants, and Consequences. Marriage & Family Review, 60(4), 187–209. [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, A., & Graham, J. R. (2000). Culturally sensitive social work practice with Arab clients in mental health settings. Health & Social Work, 25(1), 9-22.

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on Divorce: Continuing Trends and New Developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650-666.

- Apata, Olukayode Emmanuel, Oluwakemi Elizabeth Falana, Uyok Hanson, Eseoghene Oderhohwo, and Peter Oluwaseyi Oyewole. 2023. “Exploring the Effects of Divorce on Children’s Psychological and Physiological Wellbeing”. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies 49 (4):124-33. [CrossRef]

- Avellar, S., & Smock, P. J. (2005). The Economic Consequences of Divorce for Women and Children. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 295-315.

- Badri et al., 2024.

- Badri et al., 2023A.

- Badri et al., 2023B.

- Bianchi, S. M., & Spain, D. (2020). Divorce and economic outcomes: The effects of marital dissolution on financial well-being. Population Research and Policy Review, 39(3), 537-559.

- Emery, R. E. (2011). Renegotiating Family Relationships: Divorce, Child Custody, and Mediation. Guilford Press.

- Forbes (2022). The Financial Impact of Divorce. Retrieved in 2024 from https://www.forbes.

- Greene, S.M.; Anderson, E.R.; Forgatch, M.S.; DeGarmo, D.S.; Hetherington, E.M. Risk and resilience after divorce. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity; Walsh, F., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For Better or for Worse: Divorce Reconsidered. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Kaleta, K., & Mróz, J. (2023). Posttraumatic Growth and Subjective Well-Being in Men and Women after Divorce: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Self-Esteem. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3864.

- Kalmijn, M. (2018). The social consequences of divorce for adults: Social integration and support. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 399-424.

- Kalmijn, M., & Uunk, W. (2007). Regional Value Differences in Europe and Divorce Risk. European Journal of Population, 23(2), 141-168.

- Kelly, J. B., & Johnston, J. R. (2001). The Alienated Child: A Reformulation of Parental Alienation Syndrome. Family Court Review, 39(3), 249-266.

- Kelly, Joan B., Emery, Robert E., (2003). Children’s Adjustment Following Divorce: Risk and Resilience Perspectives. Family Relations, 52, 352-362.

- Kim, H., & DeVaney, S. A. (2003). The Determinants of Outstanding Balances among Credit Card Revolvers. Financial Counseling and Planning, 14(1), 67-79.

- Kołodziej-Zaleska, A., & Przybyła-Basista, H. (2016). Psychological well-being of individuals after divorce: the role of social support. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 4(4), 206–216.

- Leopold, T., & Kalmijn, M. (2016). Is Divorce More Painful When Couples Have Children? Demography, 53(6), 1717-1742.

- Lin, I.-F., & Brown, S. L. (2021). The Emotional and Economic Consequences of Gray Divorce. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(6), 1162-1172.

- McManus, P. A., & DiPrete, T. A. (2001). Losers and Winners: The Financial Consequences of Separation and Divorce for Men. American Sociological Review, 66(2), 246-268.

- Mortelmans, D. (2020). Economic Consequences of Divorce: A Review. Annual Review of Sociology, 46(1), 471-490.

- Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337-356. [CrossRef]

- Sbarra, D. A. (2015). Divorce and Health: Current Trends and Future Directions. Psychosomatic Medicine, 77(3), 227-236.

- Slanbekova, G.; Chung, M.C.; Abildina, S.; Sabirova, R.; Kapbasova, G.; Karipbaev, B. The impact of coping and emotional intelligence on the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder from past trauma, adjustment difficulty, and psychological distress following divorce. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strizzi, J.M., Koert, E., Øverup, C.S., Cipri´c, A., Sander, S., Lange, T., Schmidt, L., Hald, G.M., 2022. Examining gender effects in postdivorce adjustment trajectories over the first year after divorce in Denmark. J. Fam. Psychol. 36 (2), 268–279.

- Symoens, S., Van de Velde, S., Colman, E., & Bracke, P. (2013). Divorce and the Multidimensionality of Men and Women’s Mental Health. Social Science & Medicine, 92, 122-129.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).