Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Major Root Zone Diseases in Hydroponics and Soilless Substrate-Based (CEA) Plant Production System

| Diseases | Relevant Pathogens | Crops | Impacts | References |

| Pythium Root Rot | Pythium spp. | Strawberries, lettuce, basil | Significant yield loss, plant death | [19,20] |

| Fusarium Wilt | Fusarium oxysporum | Strawberries, tomato | Reduced growth, wilting, plant death | [21,22] |

| Rhizoctonia Root Rot | Rhizoctonia solani | Lettuce, tomato, ornamental plants, barley, canola | Root rot, reduced yield | [23,24,25] |

| Phytophthora Root Rot | Phytophthora spp. | Strawberries, lettuce | Severe root rot, plant collapse | [26,27] |

| Bacterial Wilt | Ralstonia solanacearum | Tomato | Rapid wilting, plant death | [28,29] |

| Verticillium Wilt | Verticillium dahliae | Strawberries | Stunted growth, leaf chlorosis, yield loss | [30] |

4. Oxygenated Nanobubbles Production Techniques and Their Significance in CEA-Based Crop Productions

| Nanobubble Generation Techniques | Diameter of Nanobubble | Principle of methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| Mechanical Stirring | 150-200 nm | Introducing gas into a liquid to generate bubbles | Simple to implement, cost-effective | For a small amount of nanobubble production | [40,45] |

| Nanoscale Pore Membrane | 360-720 nm | Imposing gas flow across nanoporous membranes | Precise control in size and distribution | Membrane clogging | [41,46] |

| Microfluidic Method | Highly controllable < 500 nm | Gas and liquid combined in microchannels to produce controlled bubbles | High precision in size, integrated with other processes | Complex and expensive | [42] |

| Acoustic Cavitation | 200-301 nm | Utilizing ultrasonic waves to generate bubbles by rapid compression and expansion. | Rapid production of nanobubbles, energy-efficient | Requires specialized equipment and limited size control | [43] |

| Hydrodynamic Cavitation | < 200-301 nm | Changes in pressure inside a fluid induce cavitation, resulting in the formation of bubbles. | Simple to implement and low-cost | Flow rate and pressure could impact the production | [43,44] |

| Dissolved Gas Release | Depending on gas solubility | Dissolving gas at elevated pressure, followed by pressure release to generate bubbles | Simple, inexpensive | Limited size control | [12] |

| Periodic Pressure Variation | Size decreases with exposure. | Periodically adjusting pressure to facilitate the dissolution and precipitation of bubble. | Precise control in uniform bubble production | Small-scale production | [47] |

| Hydraulic Air Compression | Increases in outlet pipe height | Gas is hydraulically compressed and combined with liquid to generate bubbles. | Cost-effective production of nanobubbles at low cost | Limited control size, distribution | [48] |

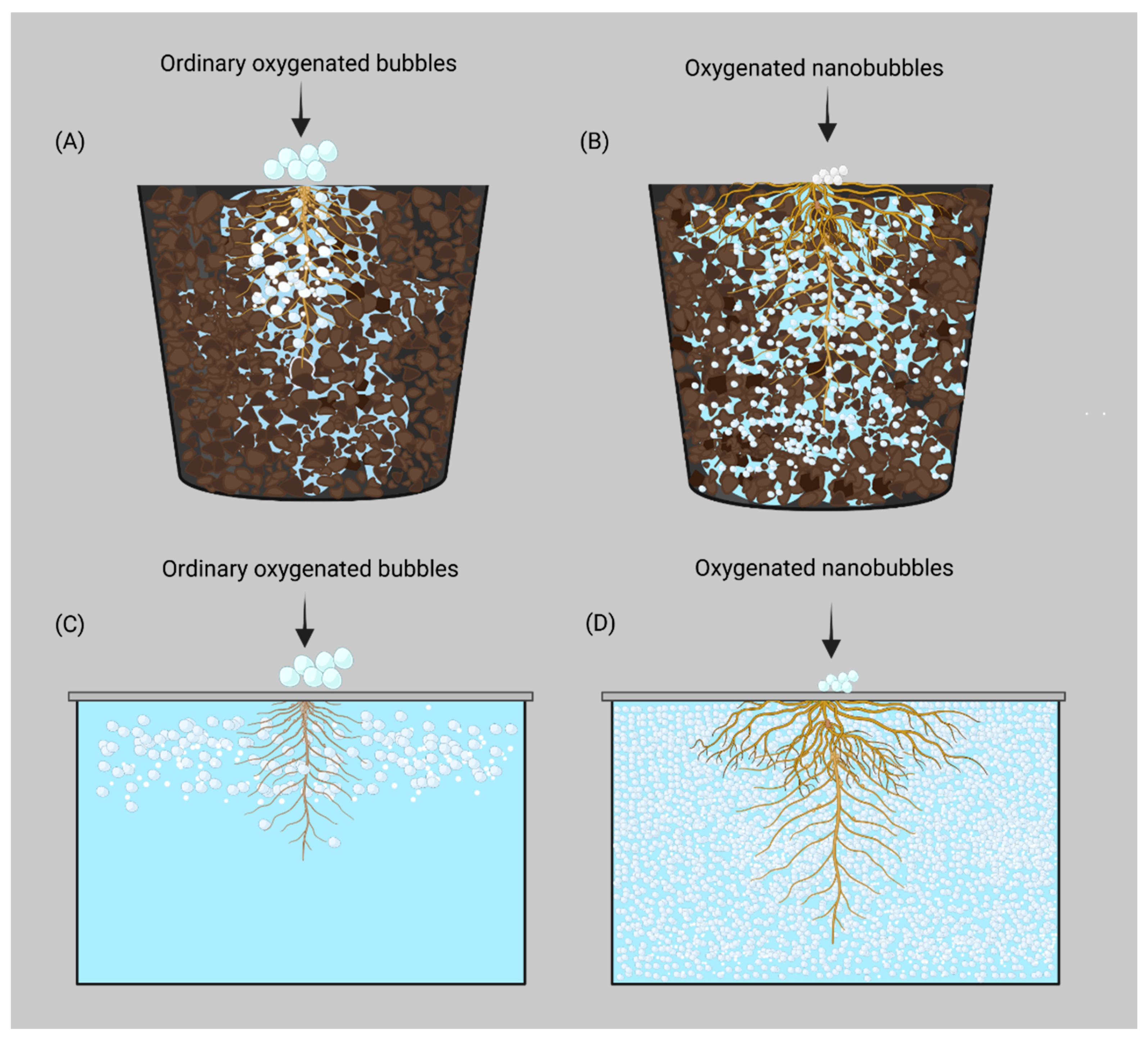

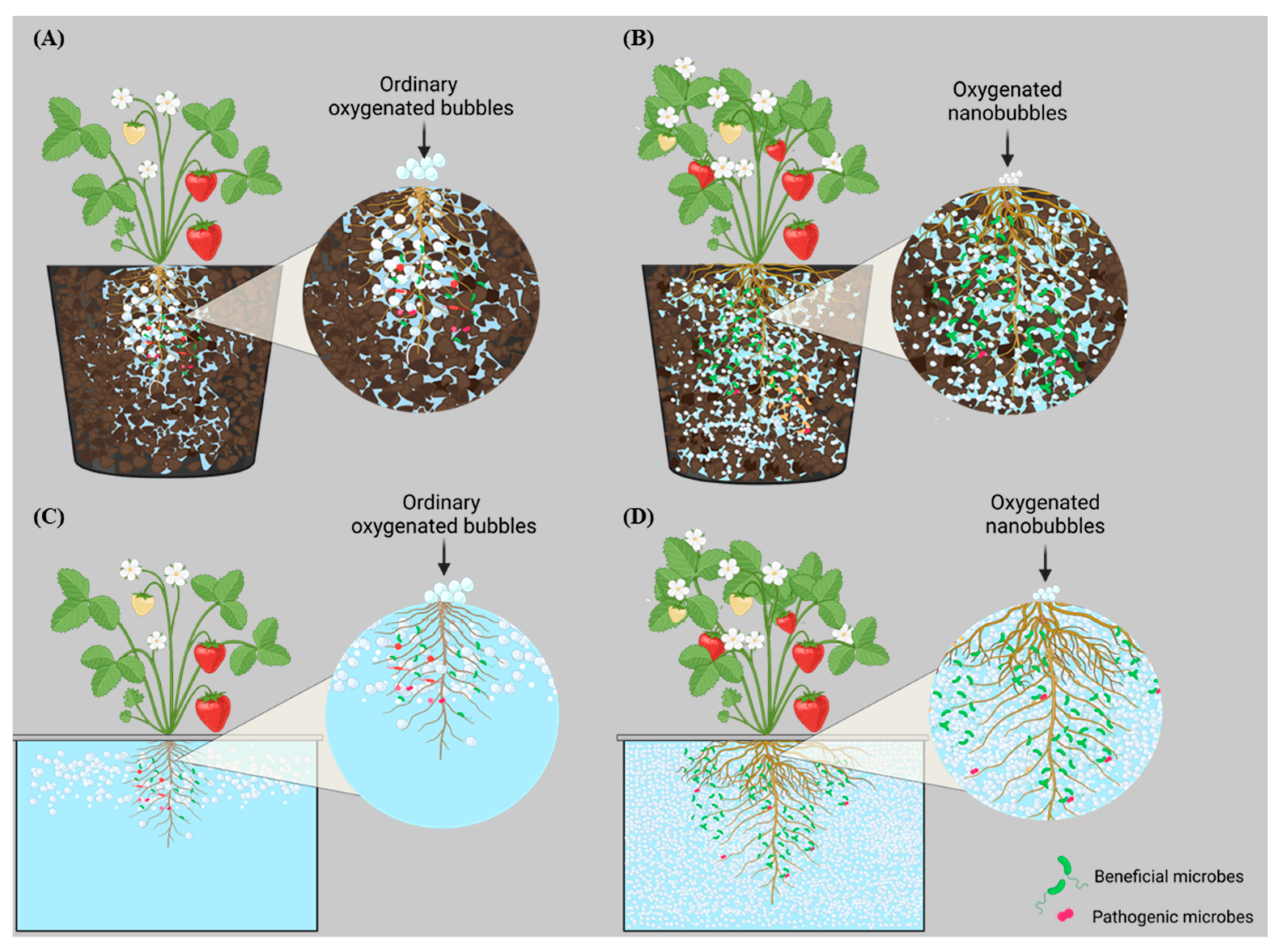

5. The Impact of Dissolved Oxygen and Beneficial Microbes in Root Zone Diseases

6. Integration between oxygenated nanobubbles and beneficial microbes

7. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez, C.; Currey, C.J.; Dickson, R.W.; Kim, H.J.; Hernández, R.; Sabeh, N.C.; Raudales, R.E.; Brumfield, R.G.; Laury-Shaw, A.; Wilke, A.K.; et al. Controlled Environment Food Production for Urban Agriculture. HortScience 2019, 54, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, W.; Minner, J. Will the Urban Agricultural Revolution Be Vertical and Soilless? A Case Study of Controlled Environment Agriculture in New York City. Land use policy 2019, 83, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, K.; Tomkins, B. Future Food-Production Systems: Vertical Farming and Controlled-Environment Agriculture. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 2017, 13, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. The State of Food and Agriculture 2021 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, A.; Newman, L.; Graham, T.; Fraser, E.D.G. Exploring the Landscape of Controlled Environment Agriculture Research: A Systematic Scoping Review of Trends and Topics. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. The Role of Beneficial Microorganisms in Soil Quality and Plant Health. Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 5358 2022, 14, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Jha, D.K. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): Emergence in Agriculture. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2011 28:4 2011, 28, 1327–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, V.; Mall, A.K.; Singh, D. Rhizoctonia Root-Rot Diseases in Sugar Beet: Pathogen Diversity, Pathogenesis and Cutting-Edge Advancements in Management Research. The Microbe 2023, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, S.M.; Achouak, W.; Abrouk, D.; Heulin, T.; Nesme, X.; Haichar, F. el Z. Diversifying Anaerobic Respiration Strategies to Compete in the Rhizosphere. Front Environ Sci 2018, 6, 427325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K. Understanding Dissolved Oxygen. Available online: https://www.growertalks.com/Article/?articleid=22058 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Bonachela, S.; Vargas, J.A.; Acuña, R.A. Effect of Increasing the Dissolved Oxygen in the Nutrient Solution to Above-Saturation Levels in a Greenhouse Watermelon Crop Grown in Perlite Bags in a Mediterranean Area. Acta Hortic 2005, 697, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Dai, H.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, W.; Hu, Z.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W. Nanobubbles Promote Nutrient Utilization and Plant Growth in Rice by Upregulating Nutrient Uptake Genes and Stimulating Growth Hormone Production. Sci Total Environ 2021, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Zhou, L.; Yang, C.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Tomato Fusarium Wilt and Its Chemical Control Strategies in a Hydroponic System. Crop Protection 2004, 23, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Duffy, B.; Nowak, J.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Use of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria for Biocontrol of Plant Diseases: Principles, Mechanisms of Action, and Future Prospects. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bastida, F.; Zhou, B.; Sun, Y.; Gu, T.; Li, S.; Li, Y. Soil Fertility and Crop Production Are Fostered by Micro-Nano Bubble Irrigation with Associated Changes in Soil Bacterial Community. Soil Biol Biochem 2020, 141, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T. Preparation Method and Application of Nanobubbles: A Review. Coatings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1510 2023, 13, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Domalachenpa, T.; Arora, H.; Li, P.; Sharma, A.; Rajauria, G. Hydroponics: Exploring Innovative Sustainable Technologies and Applications across Crop Production, with Emphasis on Potato Mini-Tuber Cultivation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Cáceres, G.P.; Pérez-Urrestarazu, L.; Avilés, M.; Borrero, C.; Lobillo Eguíbar, J.R.; Fernández-Cabanás, V.M. Susceptibility to Water-Borne Plant Diseases of Hydroponic vs. Aquaponics Systems. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, Y.; Otsubo, K.; Watanabe, H.; Suzuki, M.; Nakayama, K.; Fukuda, T.; Fujinaga, M.; Suga, H.; Kageyama, K. Root and Crown Rot of Strawberry Caused by Pythium Helicoides and Its Distribution in Strawberry Production Areas of Japan. Journal of General Plant Pathology 2014, 80, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S. PYTHIUM WILT: MAIN ROOT ROT DISEASE OF LETTUCE | Trical Diagnostics. Available online: https://www.tricaldiagnostics.com/2018/10/26/pythium-wilt-main-root-rot-disease-of-lettuce/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Hao, J.; Wuyun, D.; Xi, X.; Dong, B.; Wang, D.; Quan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H. Application of 6-Pentyl-α-Pyrone in the Nutrient Solution Used in Tomato Soilless Cultivation to Inhibit Fusarium Oxysporum HF-26 Growth and Development. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.T.; Gordon, T.R. Management of Fusarium Wilt of Strawberry. Crop Protection 2015, 73, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijst, G.; Schneider, J.H.M. Flowerbulbs Diseases Incited by Rhizoctonia Species. Rhizoctonia Species: Taxonomy, Molecular Biology, Ecology, Pathology and Disease Control 1996, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson-Benavides, B.A.; Dhingra, A. Understanding Root Rot Disease in Agricultural Crops. Horticulturae 2021, Vol. 7, Page 33 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewoldemedhin, Y.T.; Lamprecht, S.C.; McLeod, A.; Mazzola, M. Characterization of Rhizoctonia Spp. Recovered from Crop Plants Used in Rotational Cropping Systems in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. 2007, 90, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, D.G.; Forsberg, L.I. Phytophthora Root Rot in Hydroponically Grown Lettuce. Australasian Plant Pathology 1991, 20, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimoto, K. SELECTION IN STRAWBERRY WITH RESISTANCE TO PHYTOPHTHORA ROOT ROT FOR HYDROPONICS. Acta Hortic 1992, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Iwasaki, Y. Control of Ralstonia Solanacearum in Tomato Hydroponics Using a Polyvinylidene Fluoride Ultrafiltration Membrane. Acta Hortic 2018, 1227, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, T.R.; Jacquiod, S.; Nour, E.H.; Sørensen, S.J.; Smalla, K. Biocontrol of Bacterial Wilt Disease Through Complex Interaction Between Tomato Plant, Antagonists, the Indigenous Rhizosphere Microbiota, and Ralstonia Solanacearum. Front Microbiol 2020, 10, 484496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerton, H.M.; Li, B.; Vickerstaff, R.J.; Eyre, C.A.; Sargent, D.J.; Armitage, A.D.; Marina-Montes, C.; Garcia-Cruz, A.; Passey, A.J.; Simpson, D.W.; et al. Identifying Verticillium Dahliae Resistance in Strawberry through Disease Screening of Multiple Populations and Image Based Phenotyping. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 442989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Ma, Y.; Bao, S.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Lu, X.; Ran, J. Exploring the Impact of Coconut Peat and Vermiculite on the Rhizosphere Microbiome of Pre-Basic Seed Potatoes under Soilless Cultivation Conditions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L. Rhizoctonia Root Rot: Symptoms And How To Control | PT Growers and Consumers. Available online: https://www.pthorticulture.com/en-us/training-center/rhizoctonia-root-rot-symptoms-and-how-to-control (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Benti, E.A. Control of Bacterial Wilt (Ralstonia Solanacearum) and Reduction of Ginger Yield Loss through Integrated Management Methods in Southwestern Ethiopia. Open Agric J 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliar, Y.; Asi Nion, Y.; Toyota, K. Recent Trends in Control Methods for Bacterial Wilt Diseases Caused by Ralstonia Solanacearum. Microbes Environ 2015, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N.; Guidot, A.; Vailleau, F.; Valls, M. Ralstonia Solanacearum, a Widespread Bacterial Plant Pathogen in the Post-Genomic Era. Mol Plant Pathol 2013, 14, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, K.; Ogden, A.B.; Pandey, S.; Sandoya, G. V; Shi, A.; Nankar, A.N.; Jayakodi, M.; Huo, H.; Jiang, T.; Tripodi, P.; et al. Improvement of Crop Production in Controlled Environment Agriculture through Breeding. Front Plant Sci 2025, 15, 1524601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Quality Solutions Team Nanobubble Aeration Explained – Water Quality Solutions. Available online: https://waterqualitysolutions.com.au/nanobubble-aeration-explained/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Chen, W.; Bastida, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Song, P.; Kuang, N.; Li, Y. Nanobubble Oxygenated Increases Crop Production via Soil Structure Improvement: The Perspective of Microbially Mediated Effects. Agric Water Manag 2023, 282, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboer, E.J.; Richardson, M.D.; Gentimis, T.; McCalla, J.H. Analysis of Nanobubble-Oxygenated Water for Horticultural Applications. Horttechnology 2024, 34, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchepare, R.; Oliveira, H.; Nicknig, M.; Azevedo, A.; Rubio, J. Nanobubbles: Generation Using a Multiphase Pump, Properties and Features in Flotation. Miner Eng 2017, 112, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukizaki, M.; Goto, M. Size Control of Nanobubbles Generated from Shirasu-Porous-Glass (SPG) Membranes. J Memb Sci 2006, 281, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Salari, A.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Kerr, L.; Darbandi, A.; de Leon, A.C.; Exner, A.A.; Kolios, M.C.; Yuen, D.; et al. Microfluidic Generation of Monodisperse Nanobubbles by Selective Gas Dissolution. Small 2021, 17, 2100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, H.S.; Sutikno, P.; Soelaiman, T.A.F.; Sugiarto, A.T. Bulk Nanobubbles: Generation Using a Two-Chamber Swirling Flow Nozzle and Long-Term Stability in Water. J Flow Chem 2022, 12, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Song, H.; Liang, X.; Huang, N.; Li, X. Generation of Micro-Nano Bubbles by Self-Developed Swirl-Type Micro-Nano Bubble Generator. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2022, 181, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, G.; Purusothaman, M.; Rameshkumar, C.; Joy, N.; Sachin, S.; Siva Thanigai, K. Generation and Characterization of Nanobubbles for Heat Transfer Applications. Mater Today Proc 2021, 43, 3391–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.K.A.; Sun, C.; Hua, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Marhaba, T. Generation of Nanobubbles by Ceramic Membrane Filters: The Dependence of Bubble Size and Zeta Potential on Surface Coating, Pore Size and Injected Gas Pressure. Chemosphere 2018, 203, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Qi, N.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Generation and Stability of Size-Adjustable Bulk Nanobubbles Based on Periodic Pressure Change. Scientific Reports 2019 9:1 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tsai, P.; Kooij, E.S.; Prosperetti, A.; Zandvliet, H.J.W.; Lohse, D. Electrolytically Generated Nanobubbles on Highly Orientated Pyrolytic Graphite Surfaces. Langmuir 2009, 25, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, N.; Ferrier, L.; Spears, B.; Drewer, J.; Reay, D.; Skiba, U. CEA Systems: The Means to Achieve Future Food Security and Environmental Sustainability? Front Sustain Food Syst 2022, 6, 891256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, D. Why Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) Is the Future of Farming. Available online: https://www.danthermgroup.com/uk/insights/why-controlled-environment-agriculture-cea-is-the-future-of-farming (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Peters Ben The Correct Oxygen Content in the Roots of a Plant. Available online: https://royalbrinkman.com/knowledge-center/technical-projects/correct-oxygen-in-roots-plant (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Moleaer Oxygen Uptake by Roots Is Critical for Plant Respiration. Available online: https://www.moleaer.com/blog/horticulture/high-plant-yields-oxygen-uptake-by-roots-is-critical-for-plant-respiration (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Ben-Noah, I.; Friedman, S.P. Review and Evaluation of Root Respiration and of Natural and Agricultural Processes of Soil Aeration. Vadose Zone Journal 2018, 17, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tian, J.; Yan, X.; Shen, H. Effects of Different Concentrations of Dissolved Oxygen or Temperatures on the Growth, Photosynthesis, Yield and Quality of Lettuce. Agric Water Manag 2020, 228, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyantohadi, A.; Kyoren, T.; Hariadi, M.; Purnomo, M.H.; Morimoto, T. Effect of High Consentrated Dissolved Oxygen on the Plant Growth in a Deep Hydroponic Culture under a Low Temperature. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2010, 43, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Q.; Xiukang, W.; Haider, F.U.; Kučerik, J.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Holatko, J.; Naseem, M.; Kintl, A.; Ejaz, M.; Naveed, M.; et al. Rhizosphere Bacteria in Plant Growth Promotion, Biocontrol, and Bioremediation of Contaminated Sites: A Comprehensive Review of Effects and Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M. Al; Lee, B.R.; Park, S.H.; Muchlas, M.; Bae, D.W.; Kim, T.H. Interactive Regulation of Immune-Related Resistance Genes with Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid Signaling in Systemic Acquired Resistance in the Xanthomonas–Brassica Pathosystem. J Plant Physiol 2024, 302, 154323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemelyanov, V. V.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Shishova, M.F. Plant Life with and without Oxygen: A Metabolomics Approach. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moleaer Root Respiration: Why Plants Need Oxygen to Thrive. Available online: https://www.moleaer.com/blog/horticulture/root-respiration (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Deguine, J.P.; Aubertot, J.N.; Flor, R.J.; Lescourret, F.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Ratnadass, A. Integrated Pest Management: Good Intentions, Hard Realities. A Review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2021 41:3 2021, 41, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jian, Q.; Yao, X.; Guan, L.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Tang, H.; Lu, L. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Improve the Growth and Quality of Several Crops. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, T.; Mafrica, R.; Bruno, M.; Vescio, R.; Sorgonà, A. Root Architectural Traits of Rooted Cuttings of Two Fig Cultivars: Treatments with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Formulation. Sci Hortic 2021, 283, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Muhammad, S.; Jin, W.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Munir, R.; et al. Modulating Root System Architecture: Cross-Talk between Auxin and Phytohormones. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1343928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Bastida, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Song, P.; Kuang, N.; Li, Y. Nanobubble Oxygenated Increases Crop Production via Soil Structure Improvement: The Perspective of Microbially Mediated Effects. Agric Water Manag 2023, 282, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Gui, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Guo, J.; Niu, D. Induced Systemic Resistance for Improving Plant Immunity by Beneficial Microbes. Plants 2022, 11, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, C. Development of Plant Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Rhizobacteria: Recognition, Initiation, Elicitation and Regulation. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 952397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Regulating Growth, Enhancing Productivity, and Potentially Influencing Ecosystems under Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Plants 2023, Vol. 12, Page 3102 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten Bruce and Pasini Federico Breathing Oxygen into Roots - Greenhouse CanadaGreenhouse Canada. Available online: https://www.greenhousecanada.com/breathing-oxygen-into-roots/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Balliu, A.; Zheng, Y.; Sallaku, G.; Fernández, J.A.; Gruda, N.S.; Tuzel, Y. Environmental and Cultivation Factors Affect the Morphology, Architecture and Performance of Root Systems in Soilless Grown Plants. Horticulturae 2021, Vol. 7, Page 243 2021, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).