Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

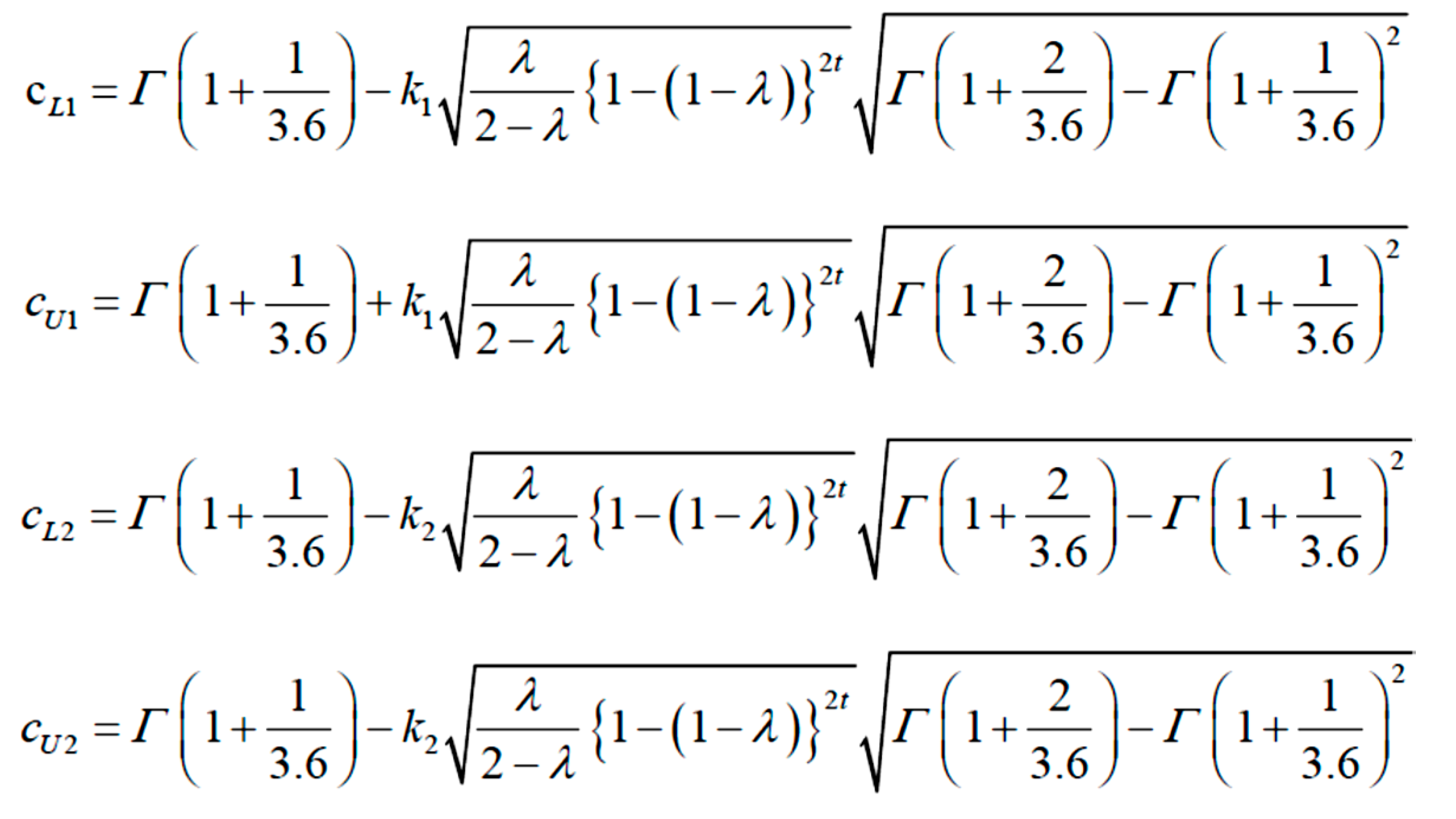

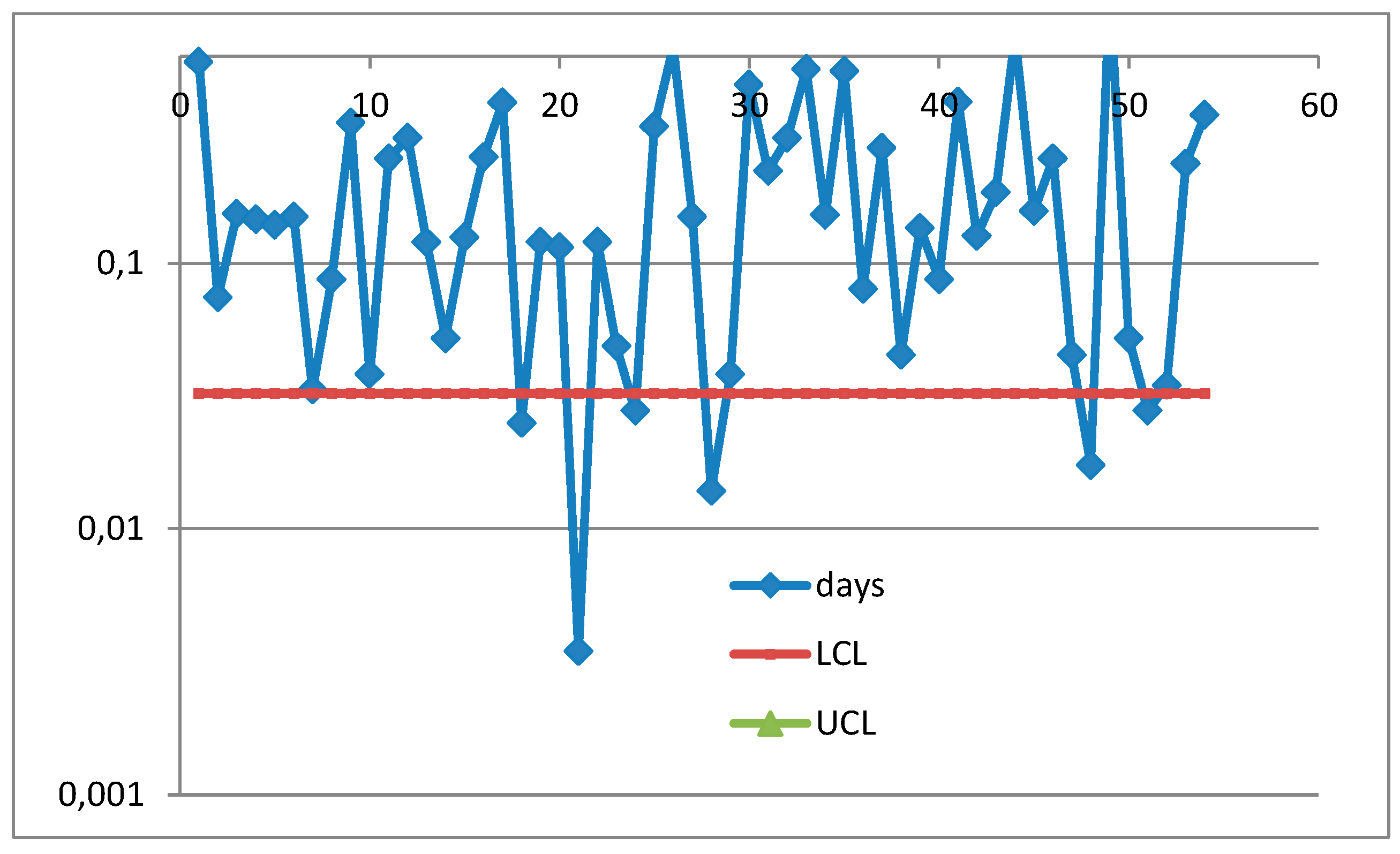

2. Materials and Methods

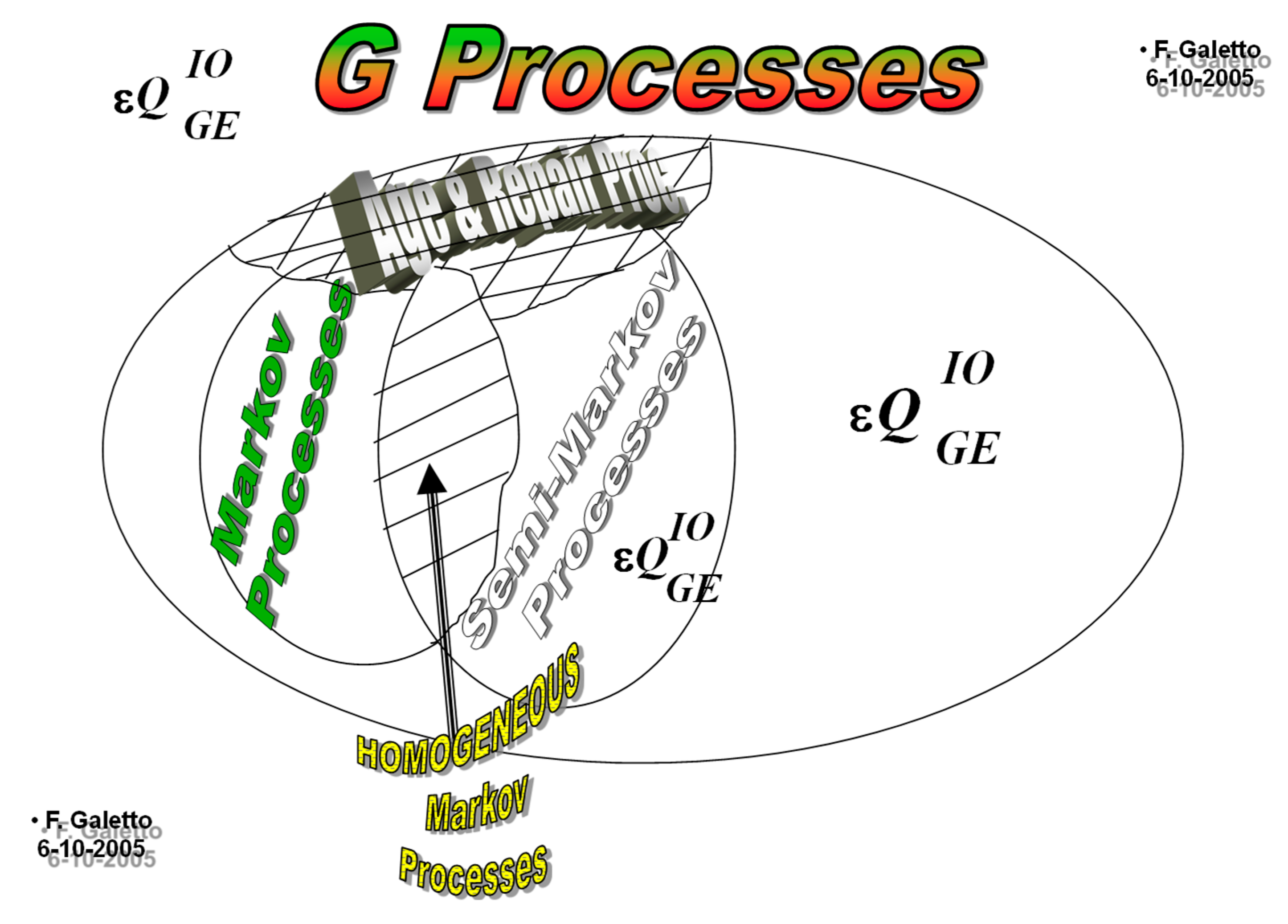

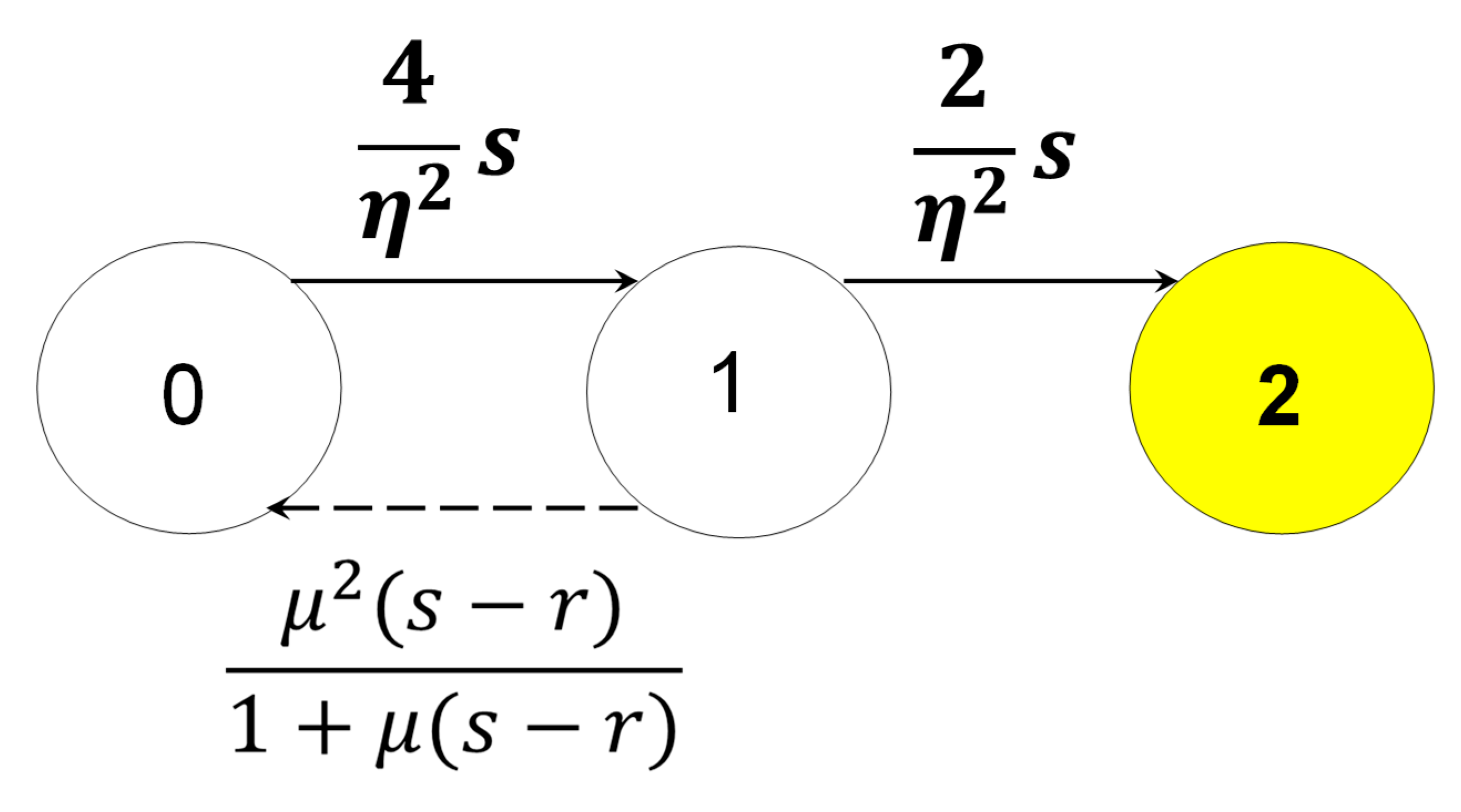

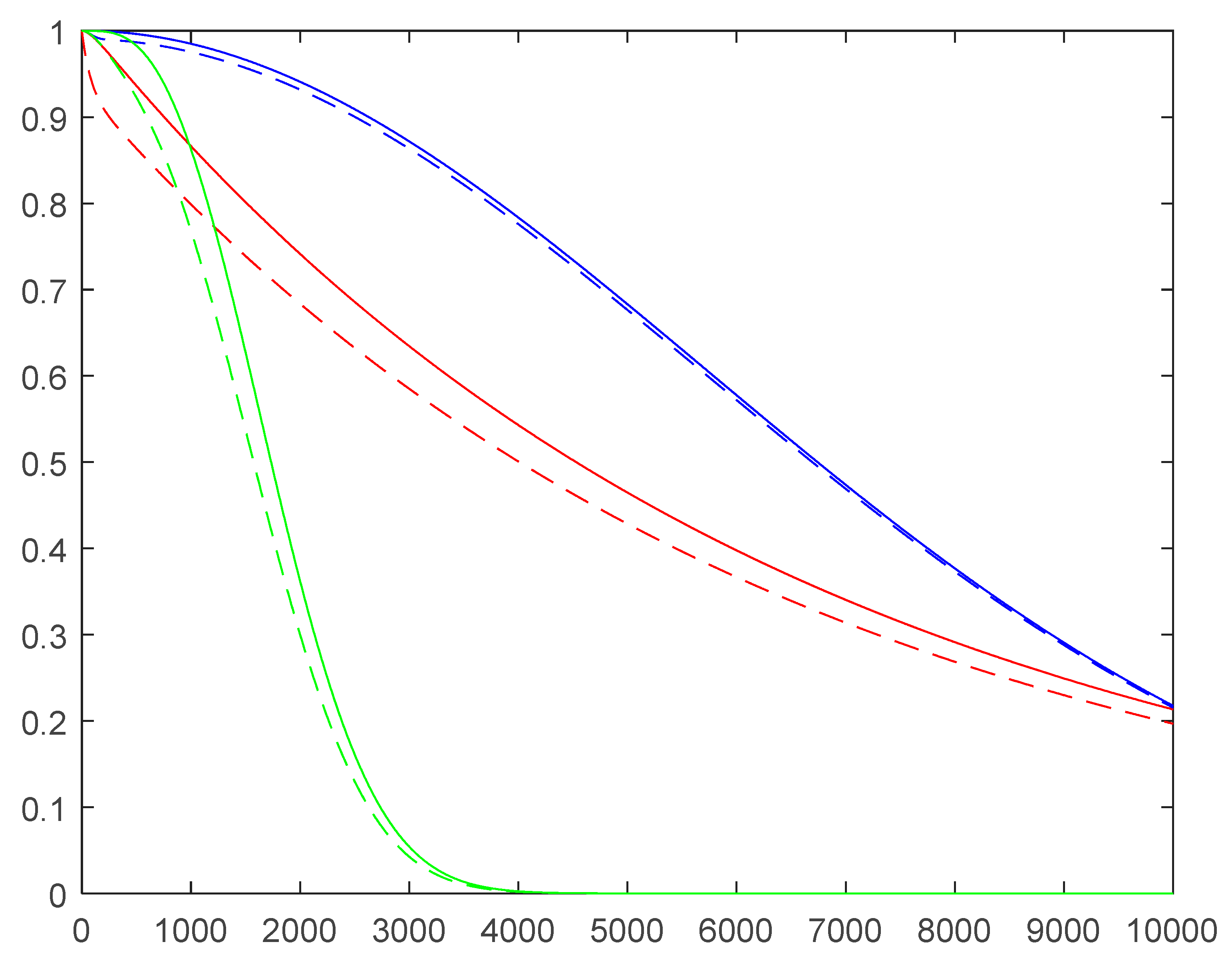

2.1. Reliability Integral Theory (RIT)

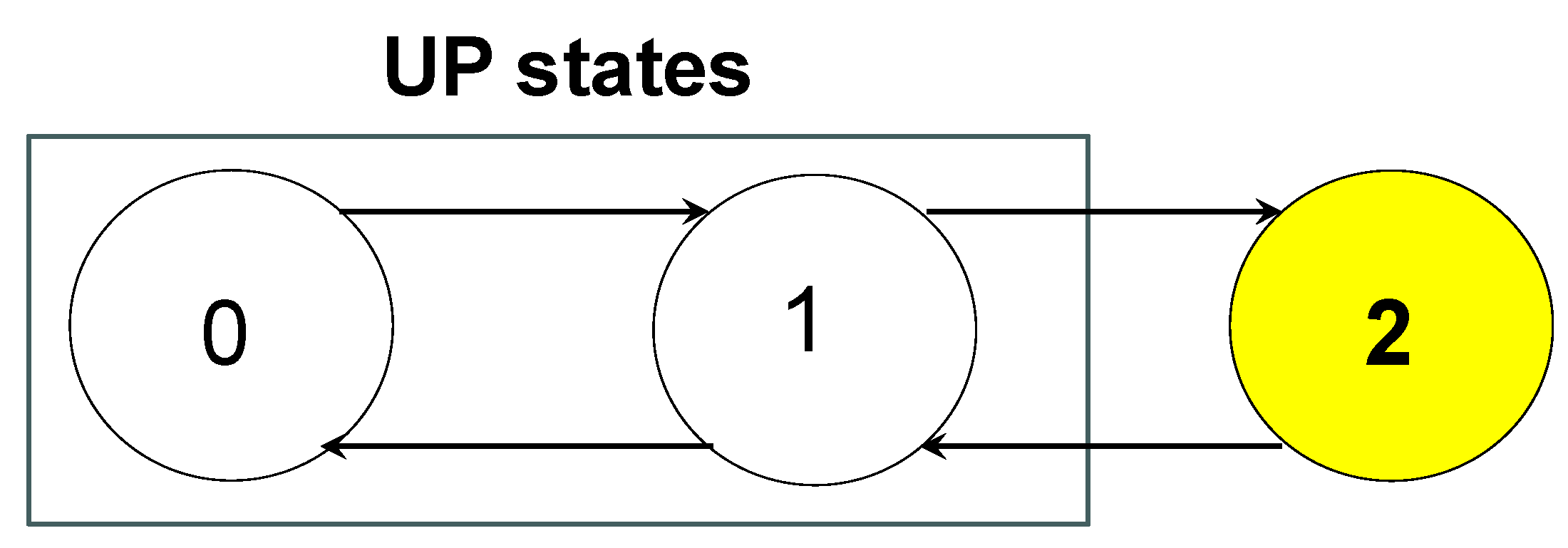

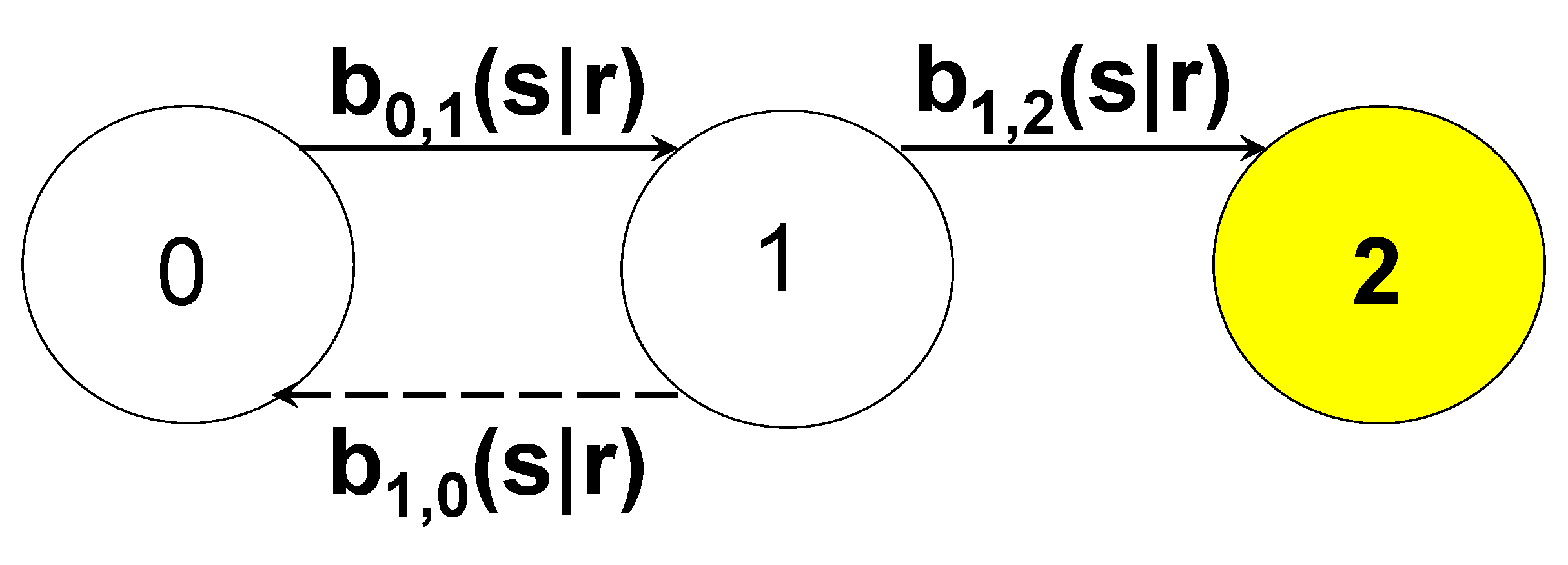

2.2. Availability Integral Theory (AIT)

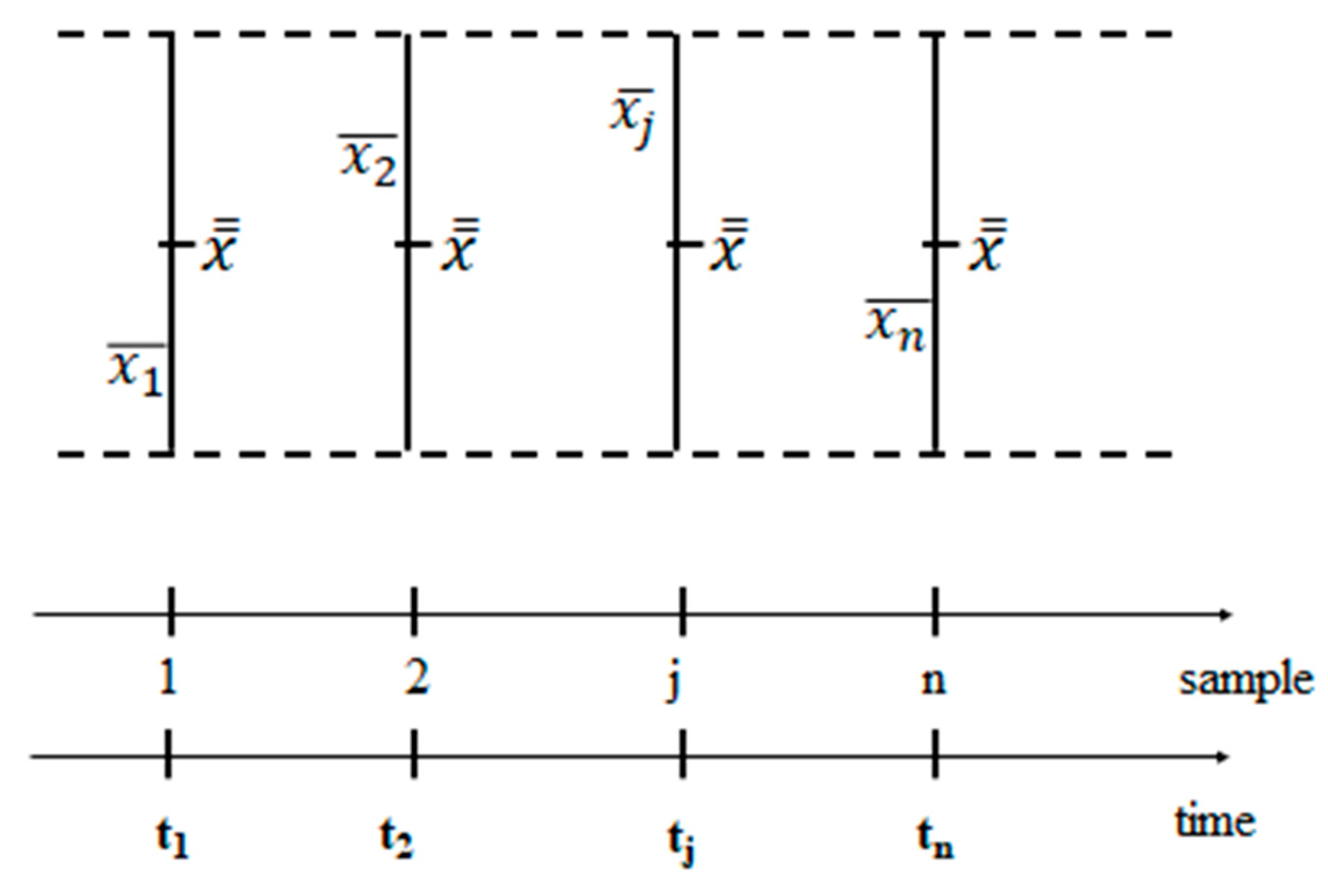

2.3. Statistics and RIT

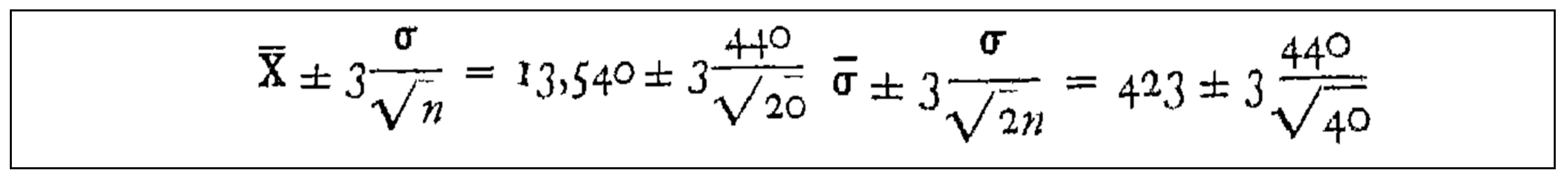

| 69.80 | 69.50 | 68.80 | 70.90 | 69.20 | 70.40 | 71.00 | 71.30 | 70.00 | 70.10 |

| 72.10 | 69.90 | 70.10 | 70.30 | 71.20 | 70.80 | 70.70 | 69.95 | 71.20 | 71.35 |

| 71.35 | 69.90 | 70.25 | 70.50 | 70.28 | 71.30 | 70.20 | 70.35 | 70.15 | 70.10 |

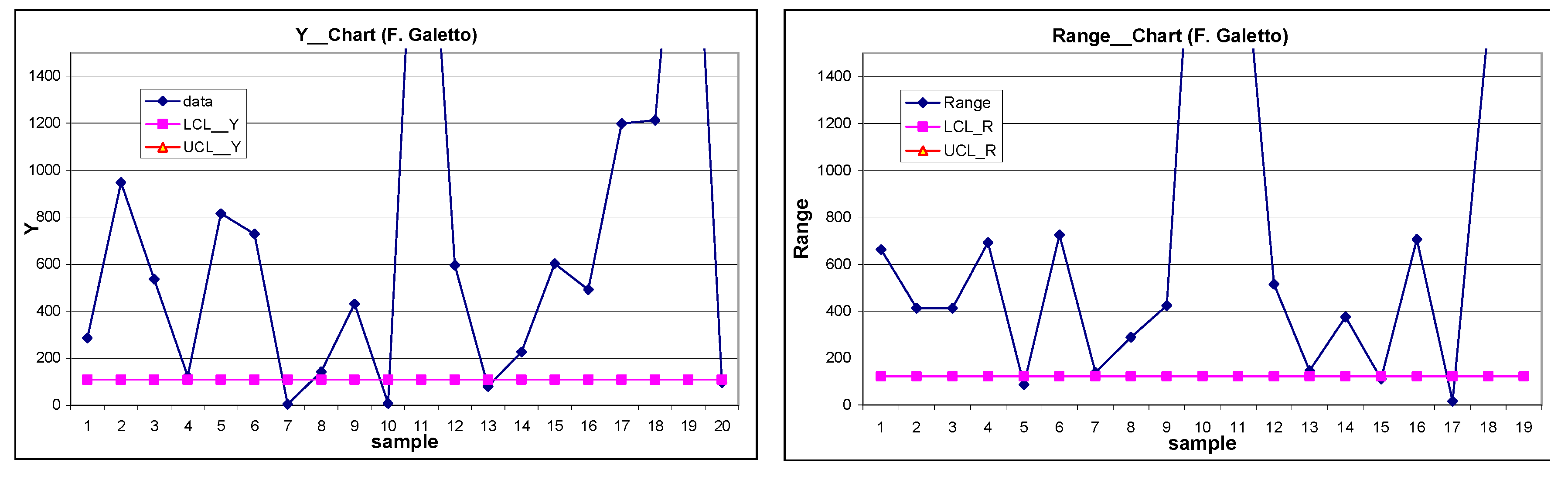

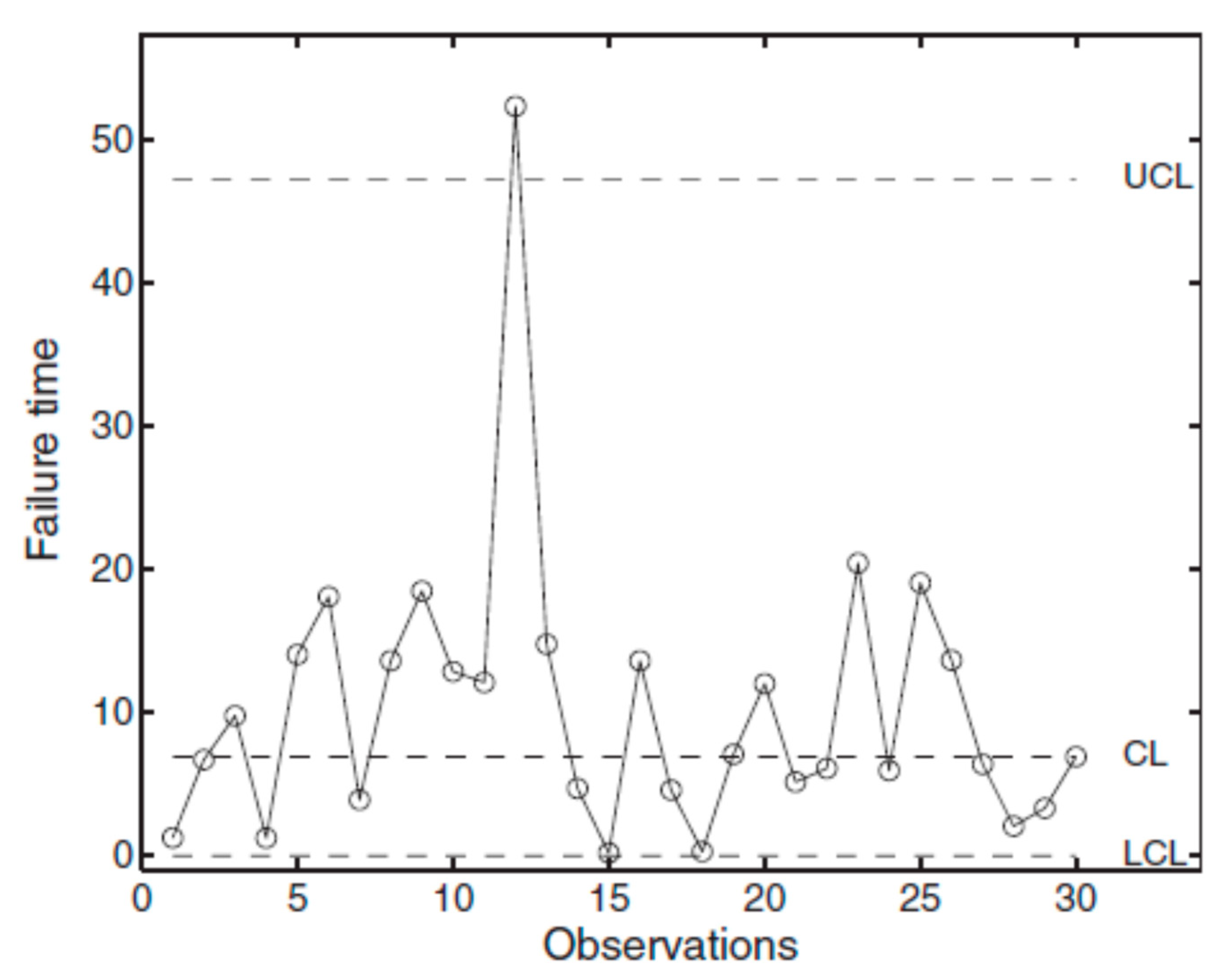

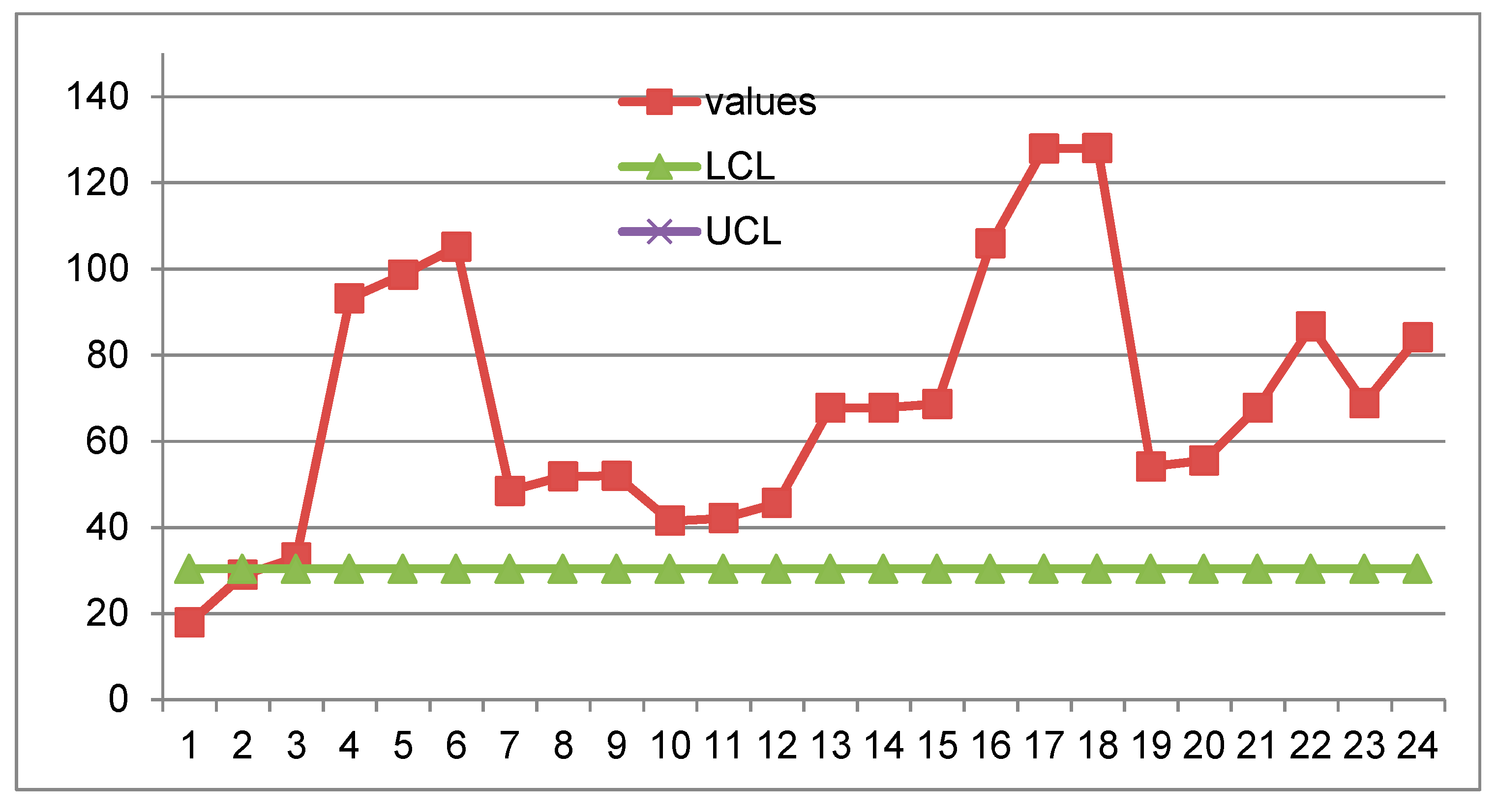

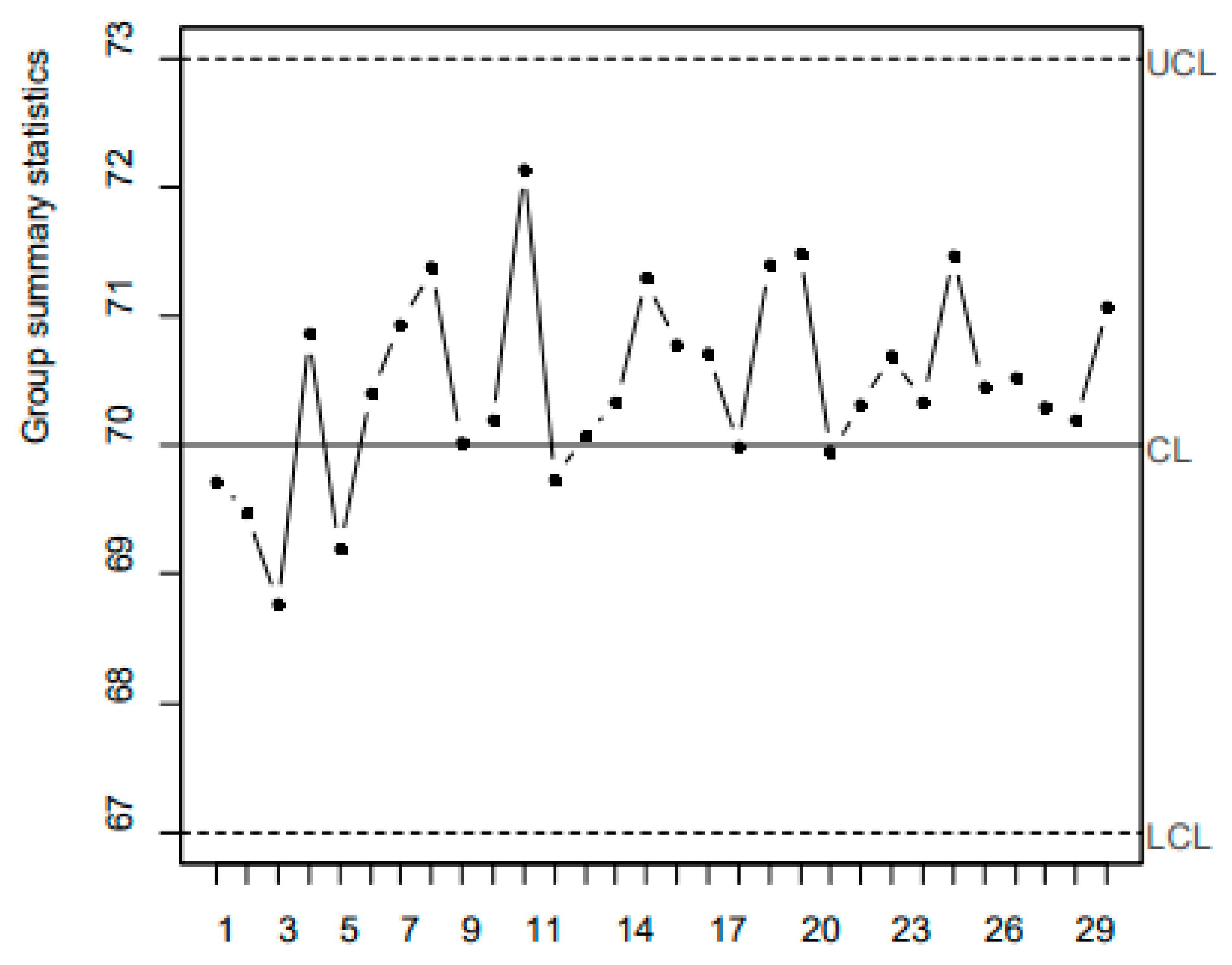

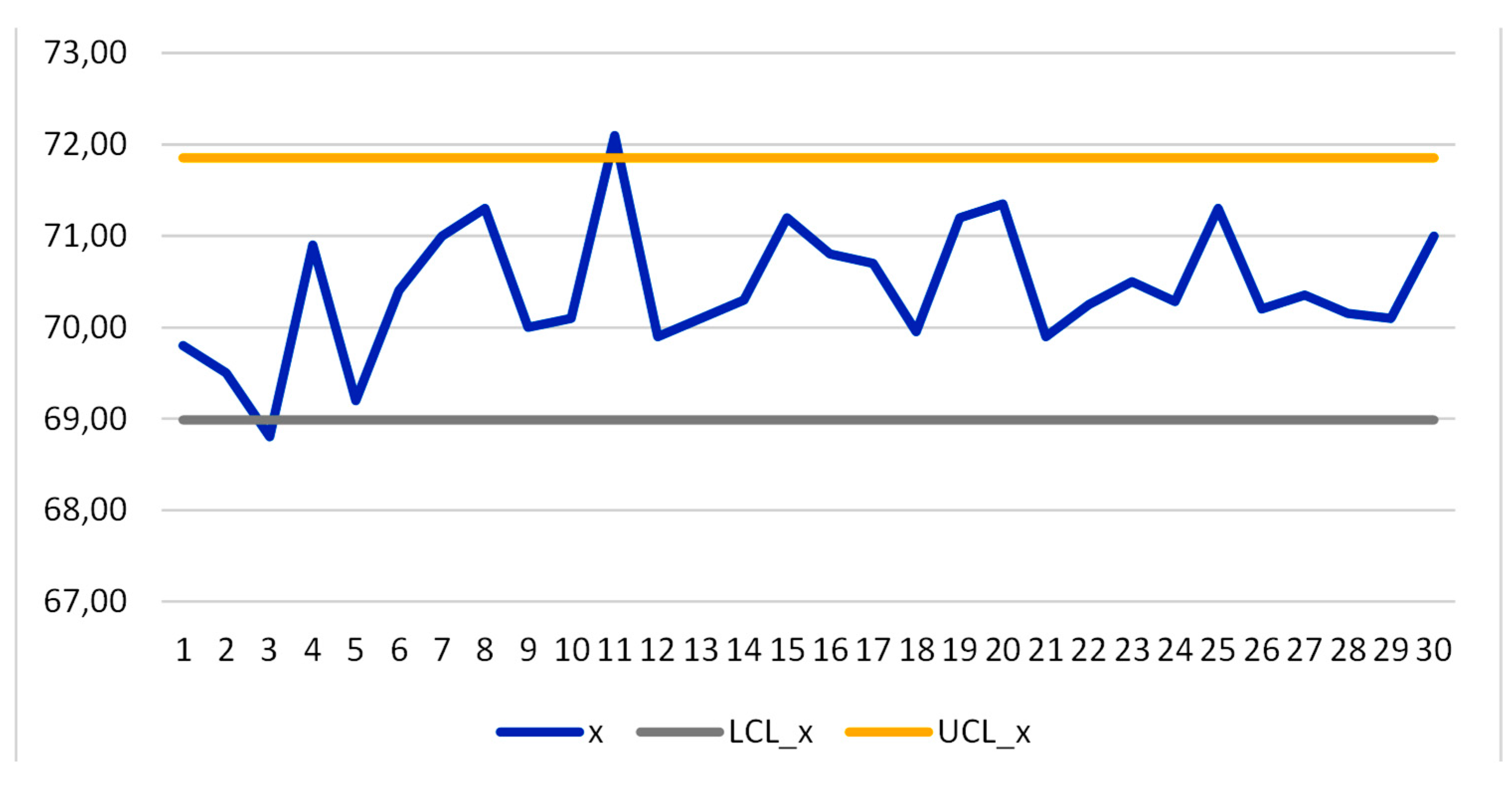

- a)

- Two points out of the Control Limits, and

- b)

- The points from 8 to 30 have a mean larger than the mean of the first seven points

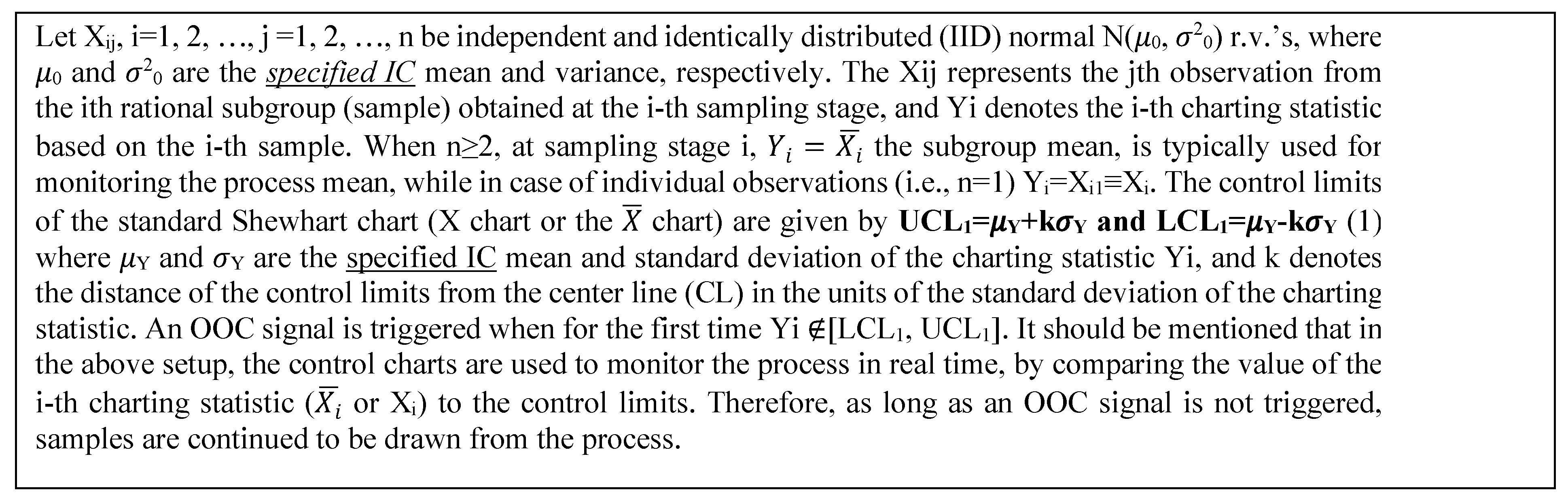

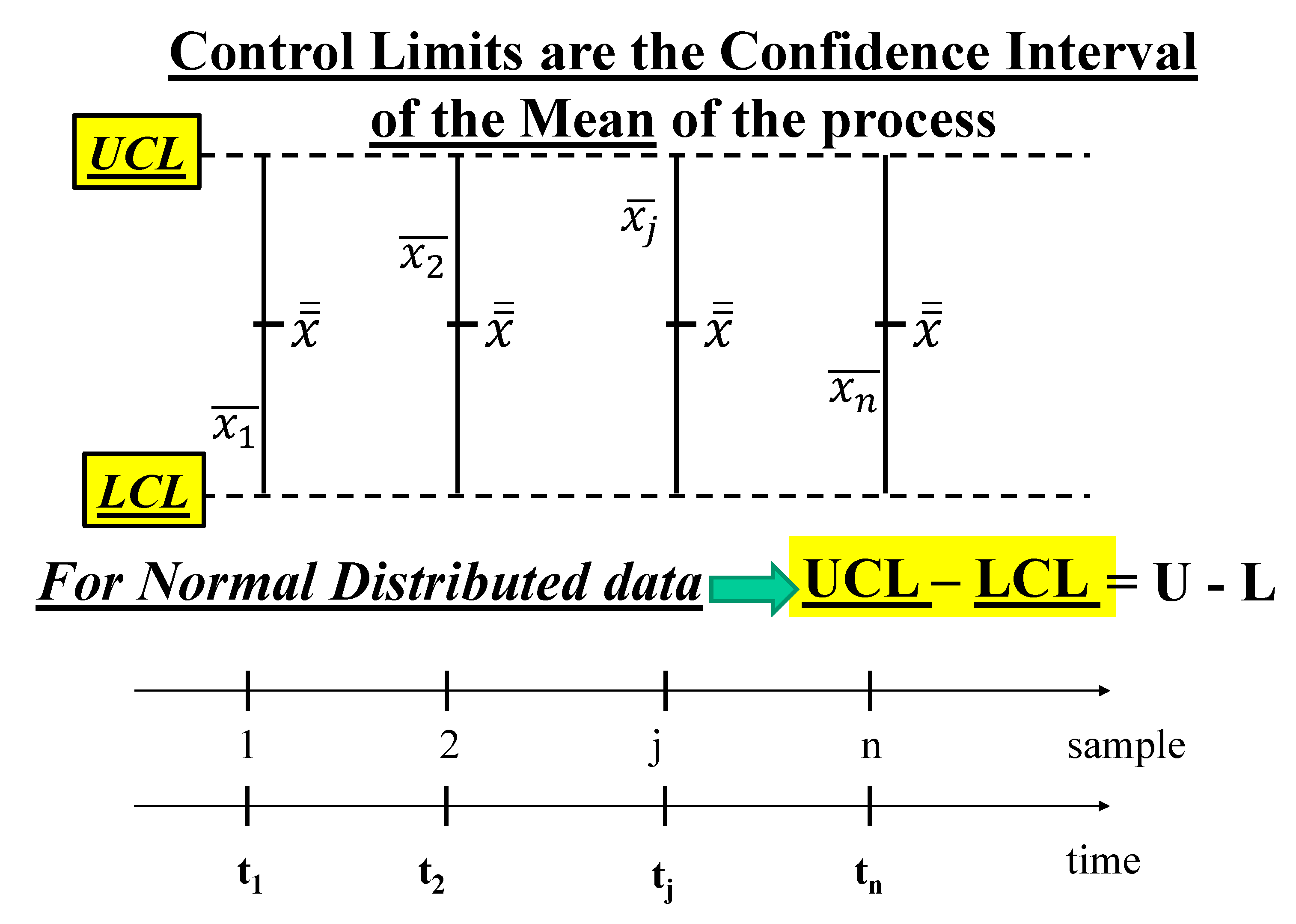

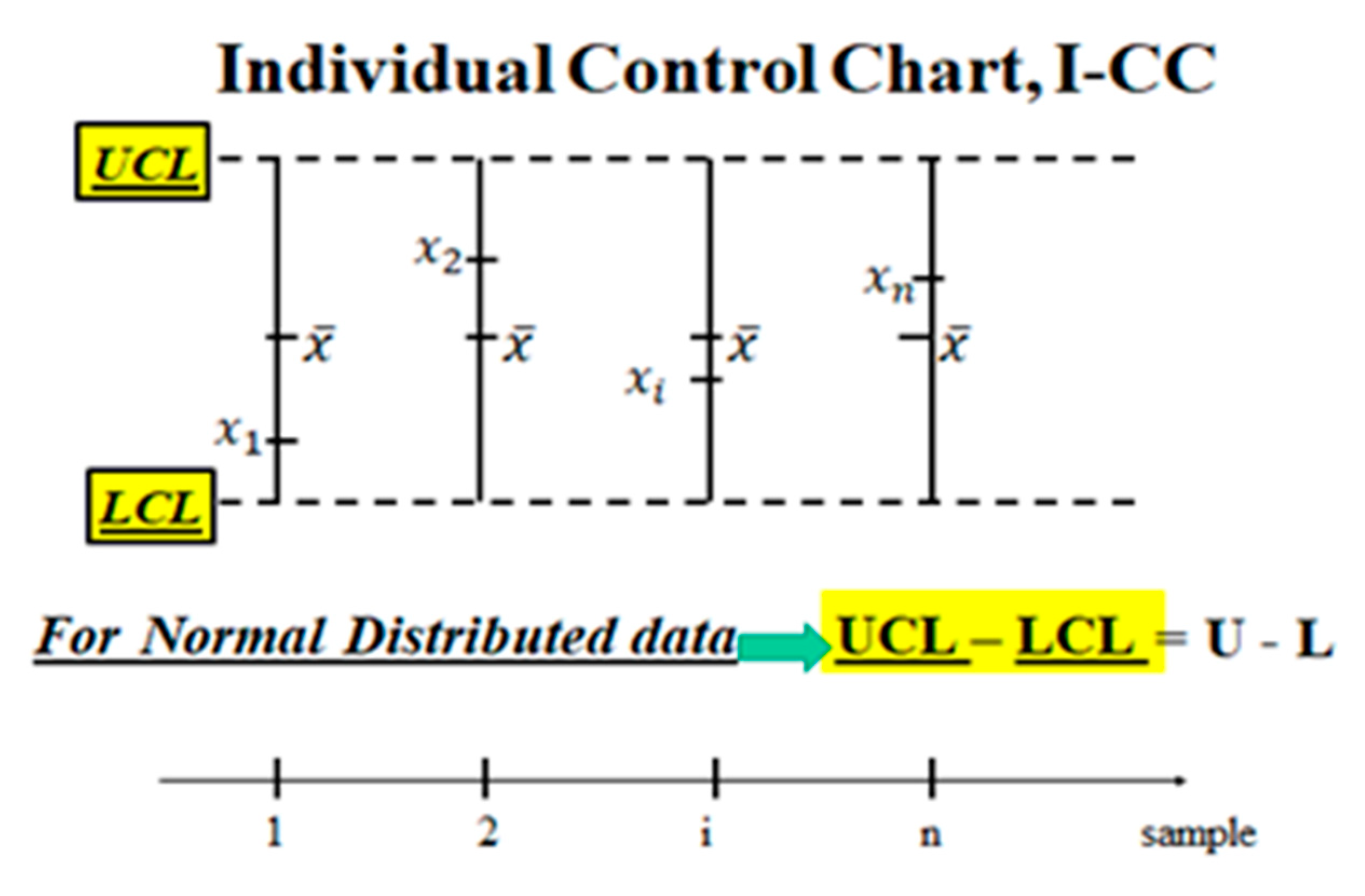

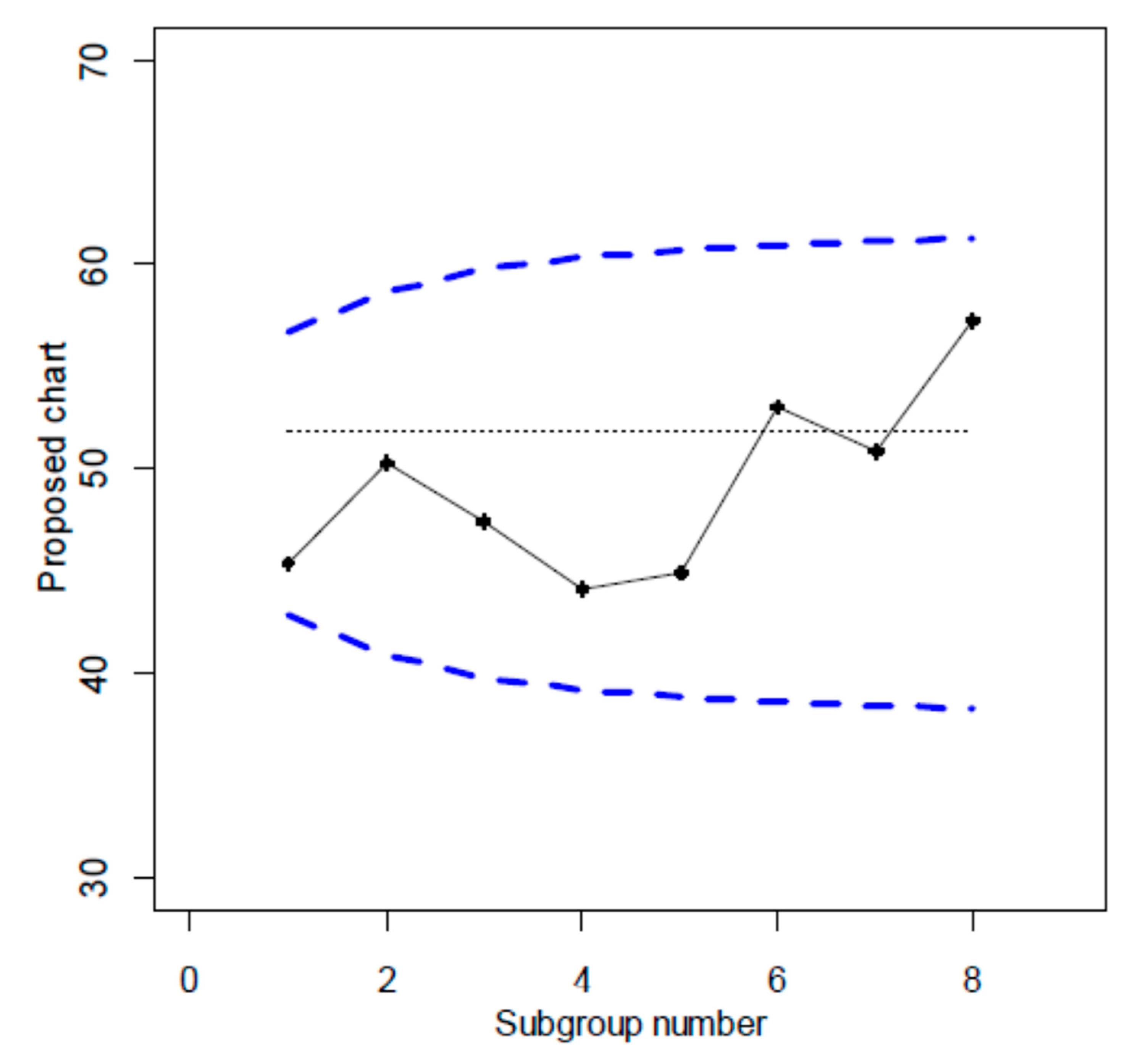

2.4. Control Charts for Process Management

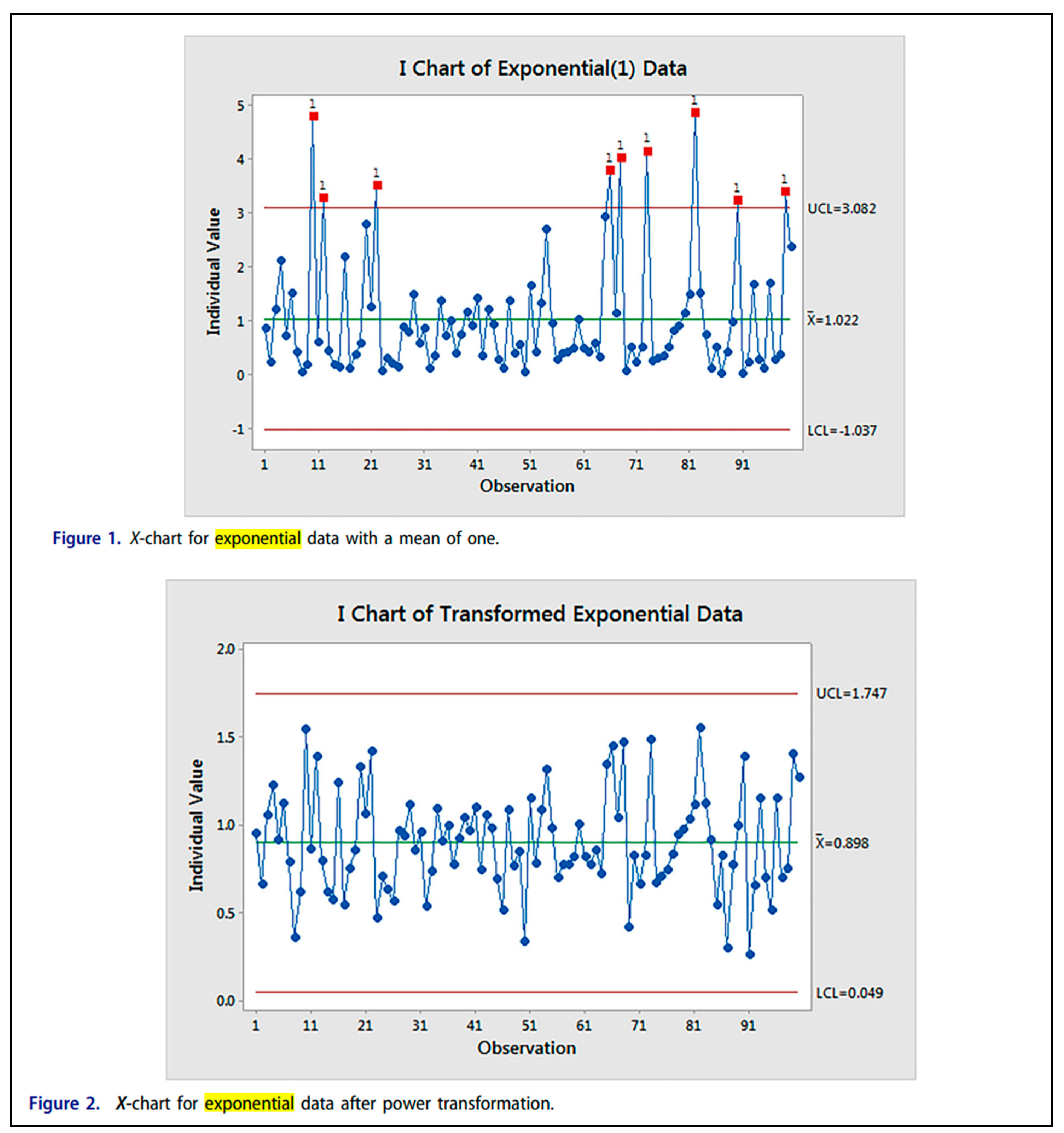

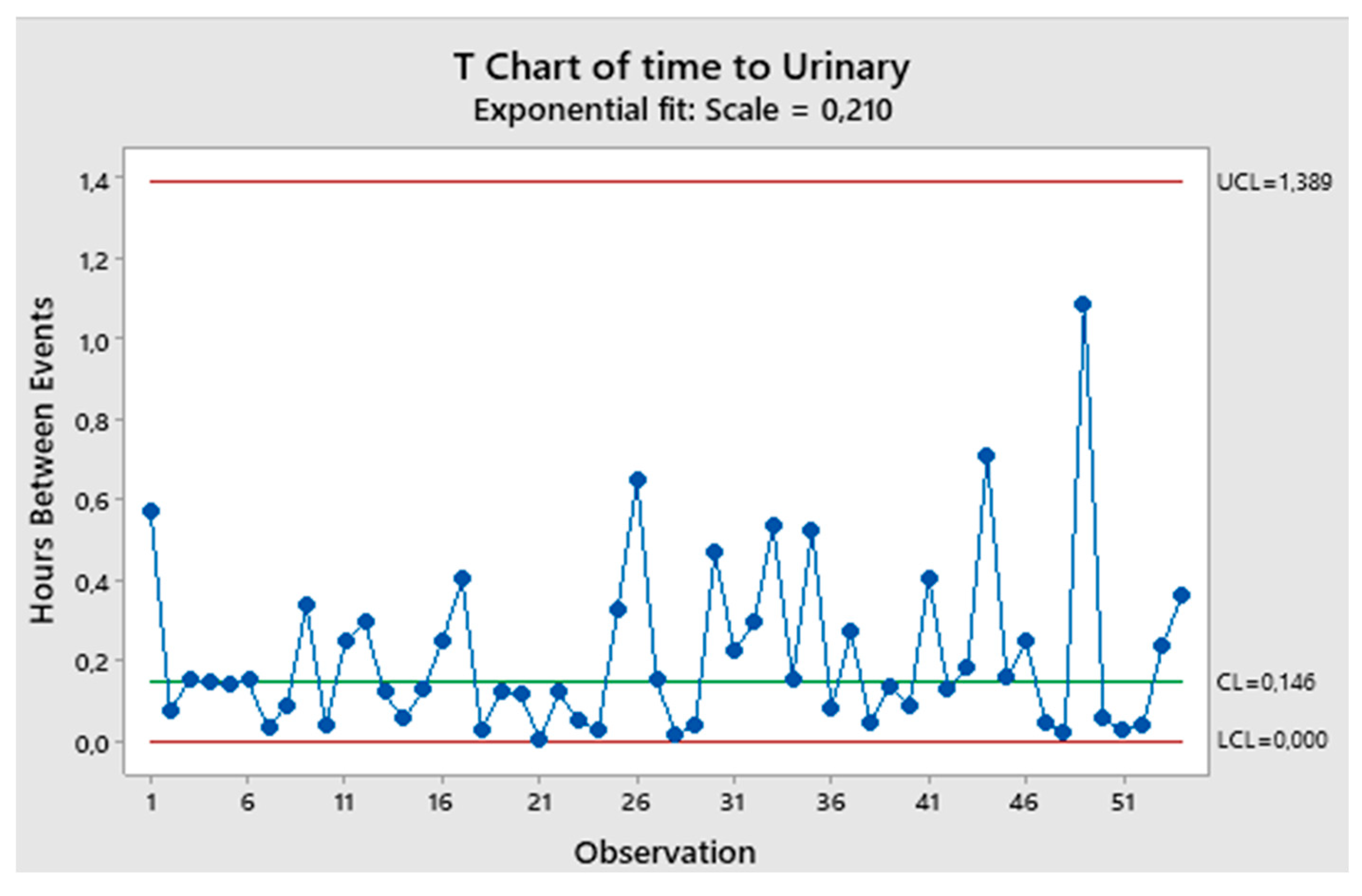

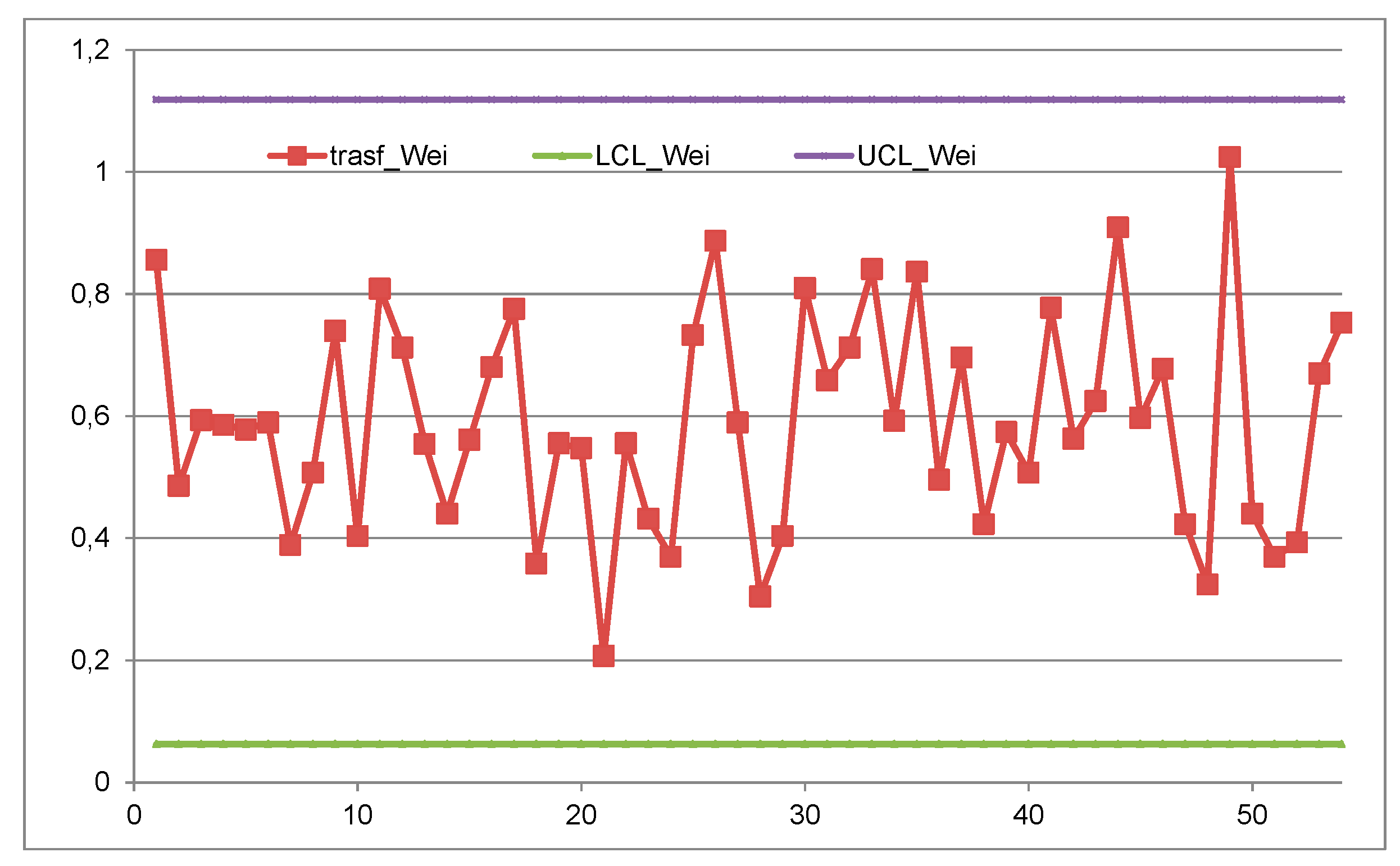

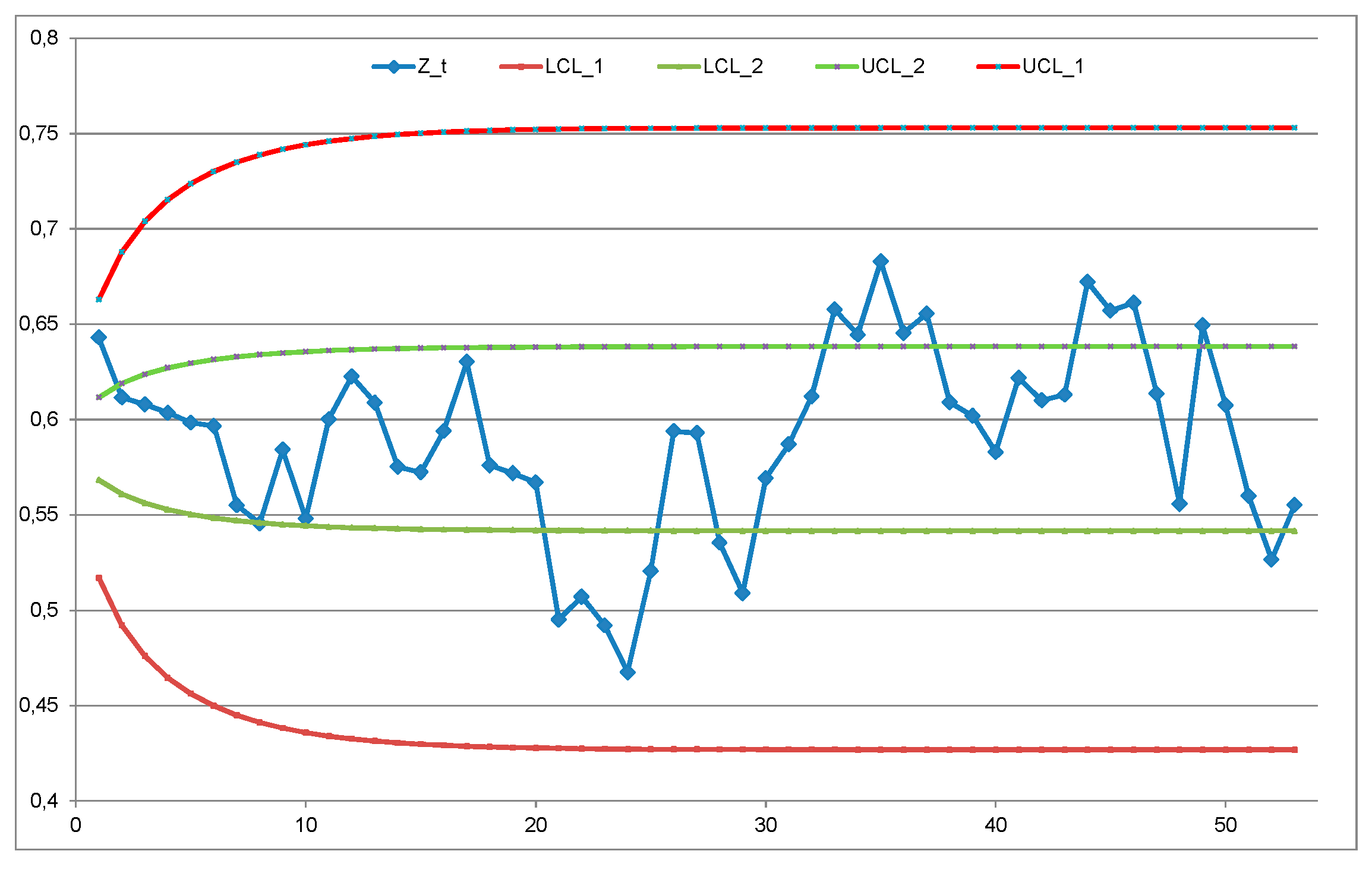

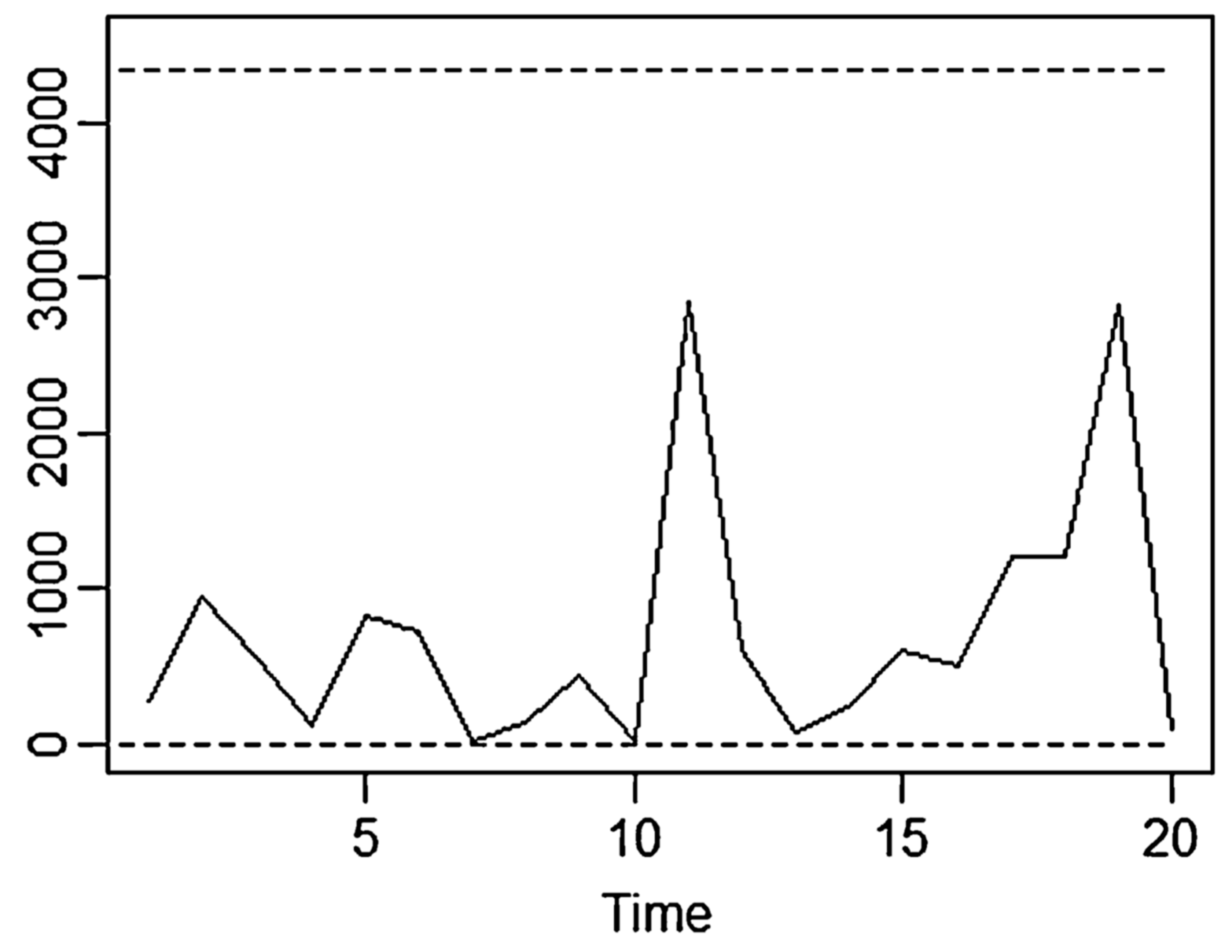

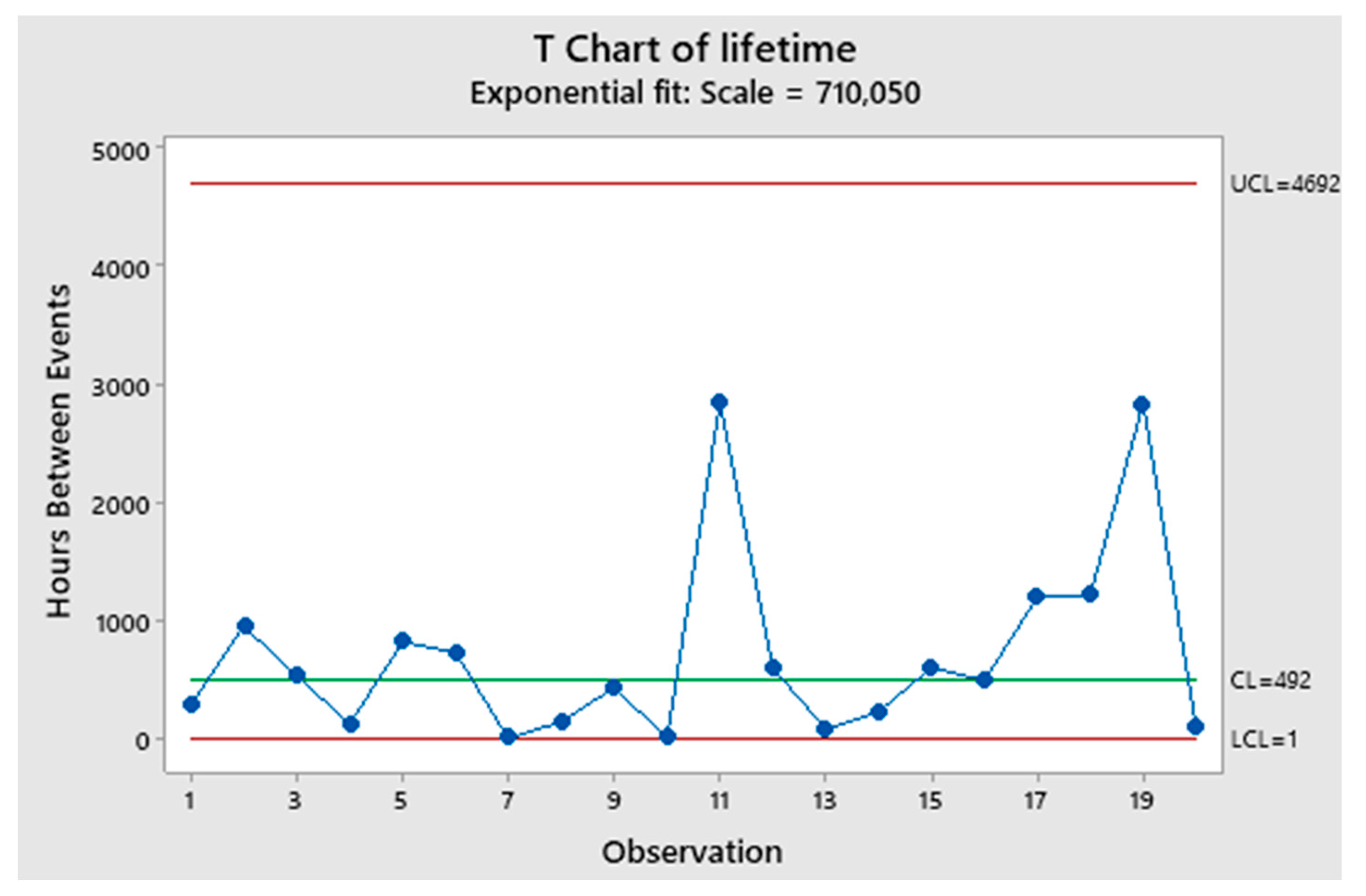

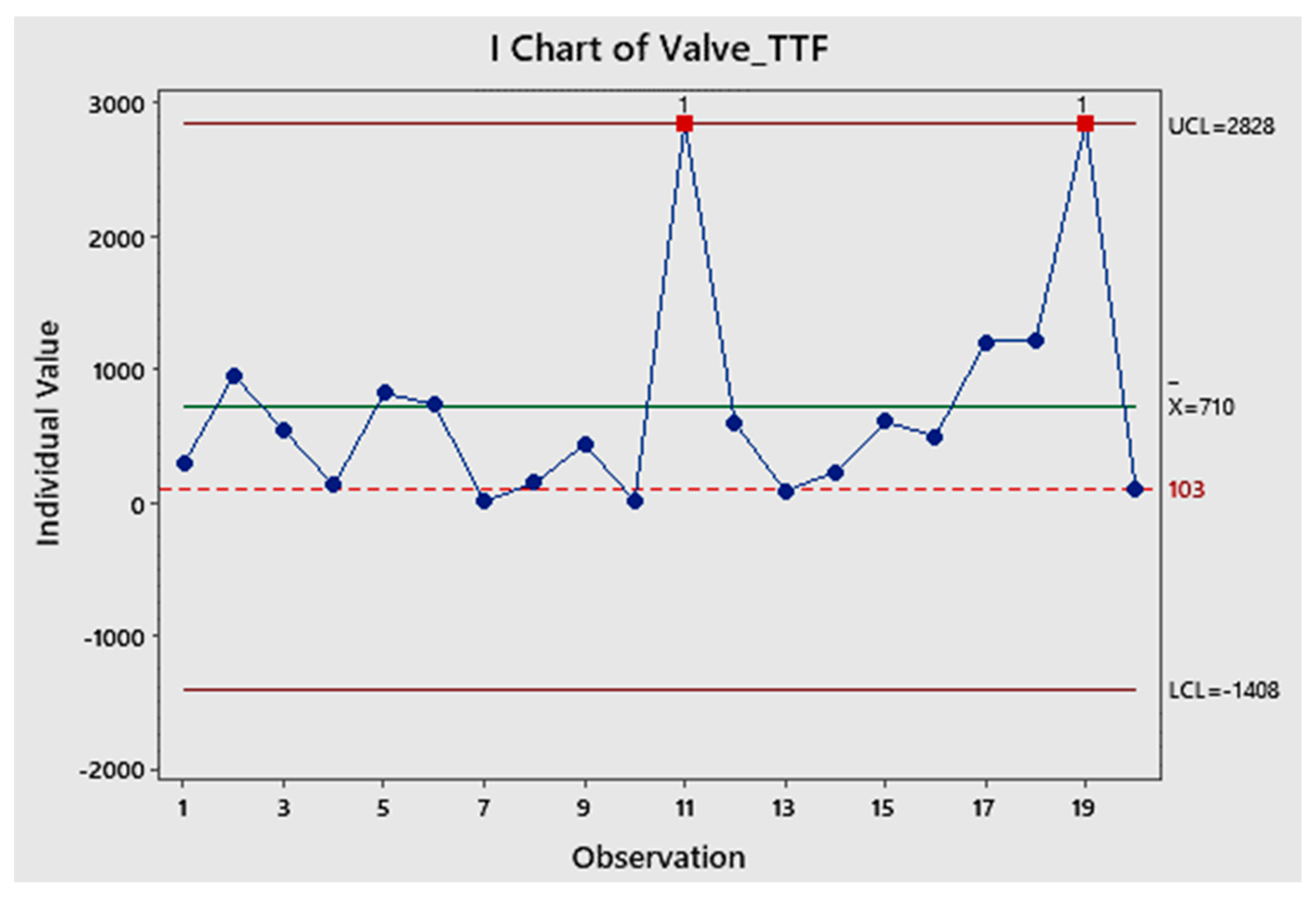

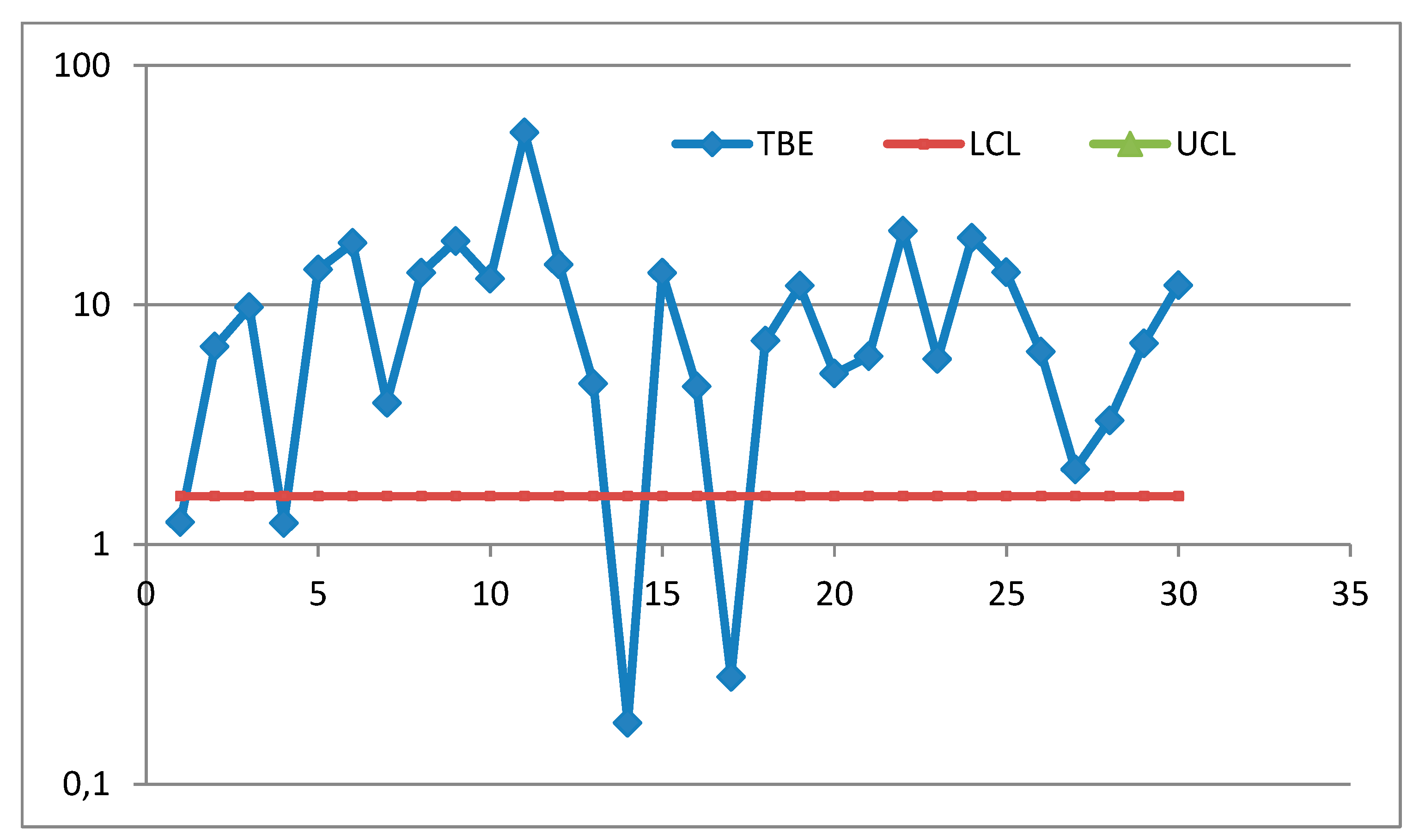

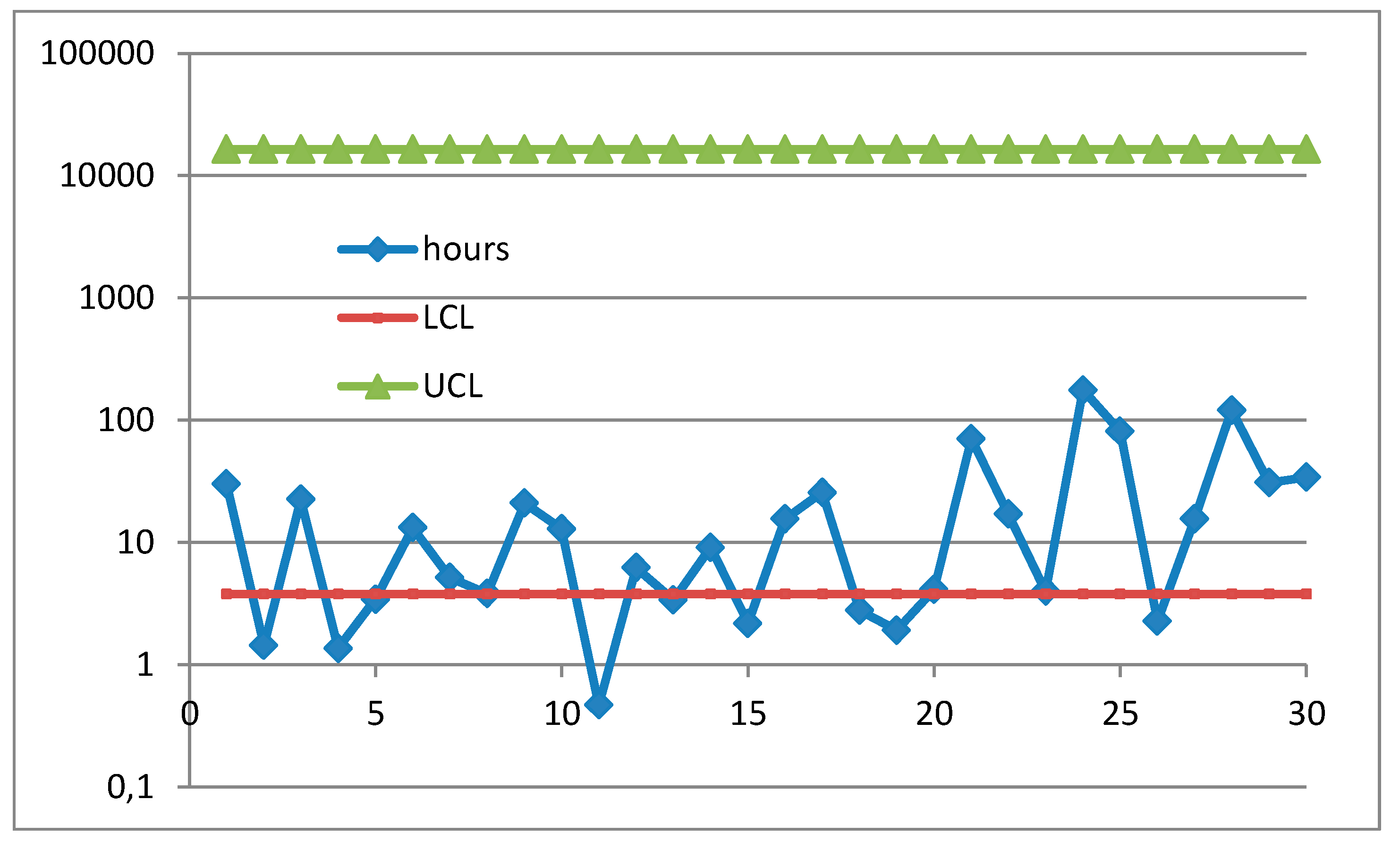

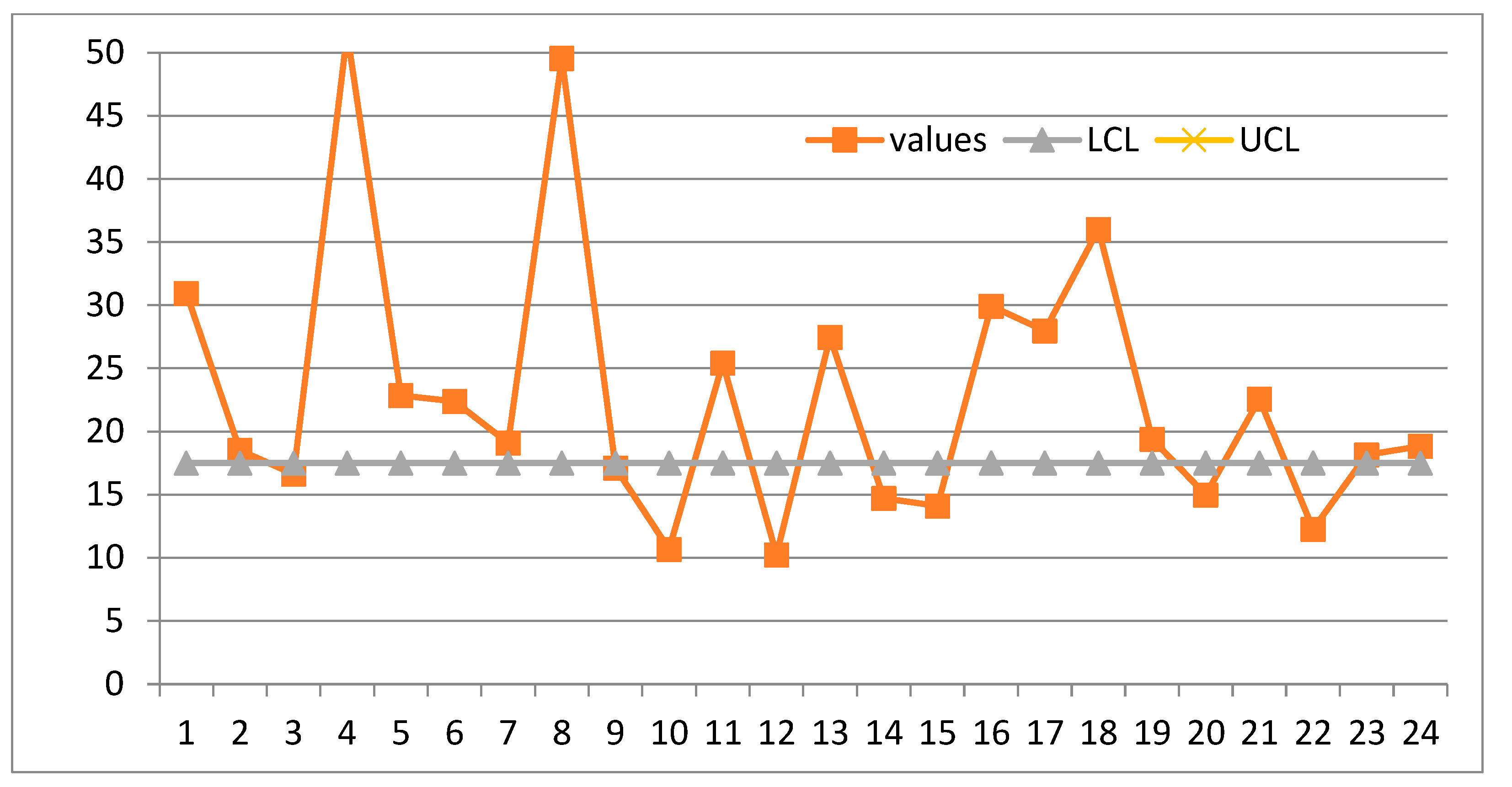

2.5. Control Charts for TBE Data

3. Results

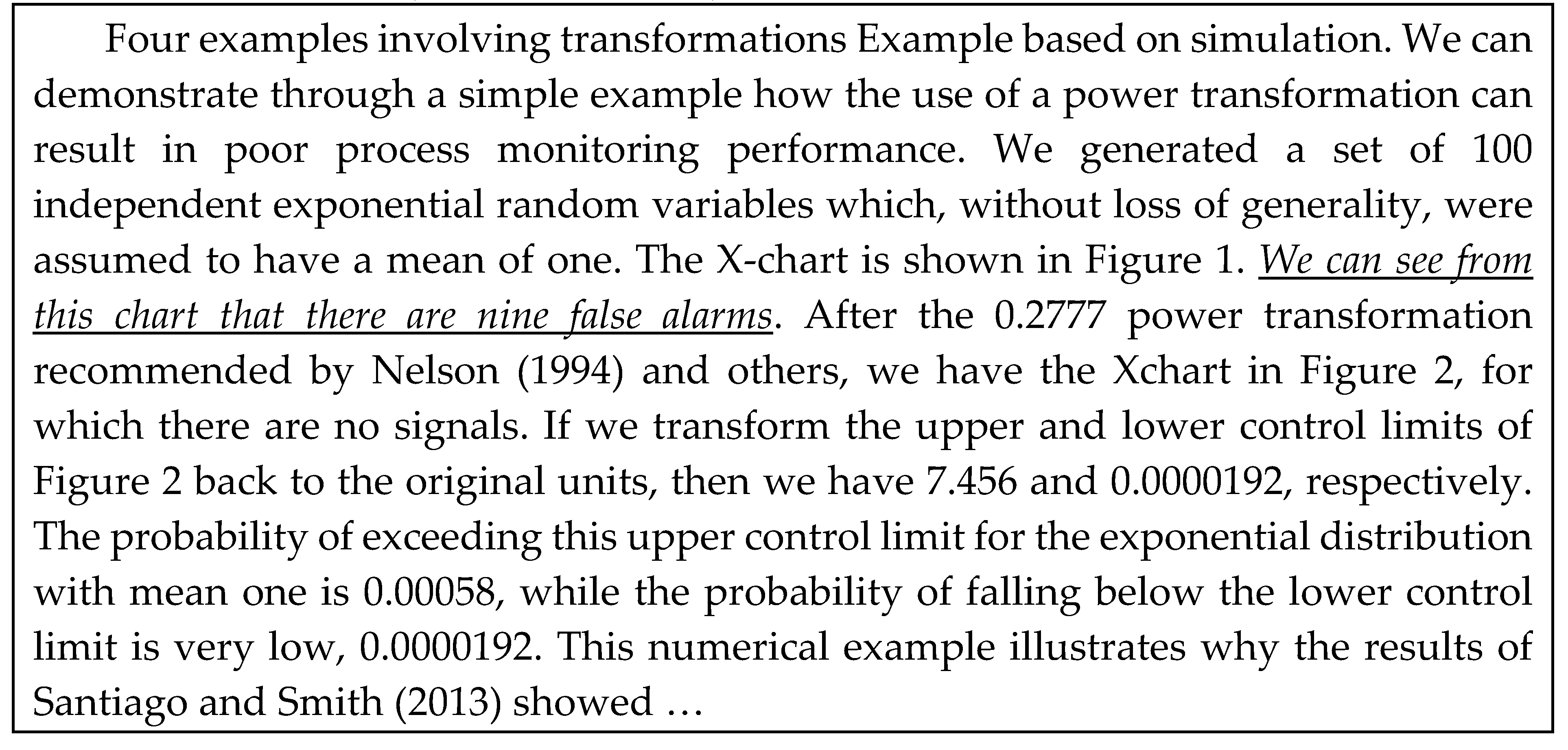

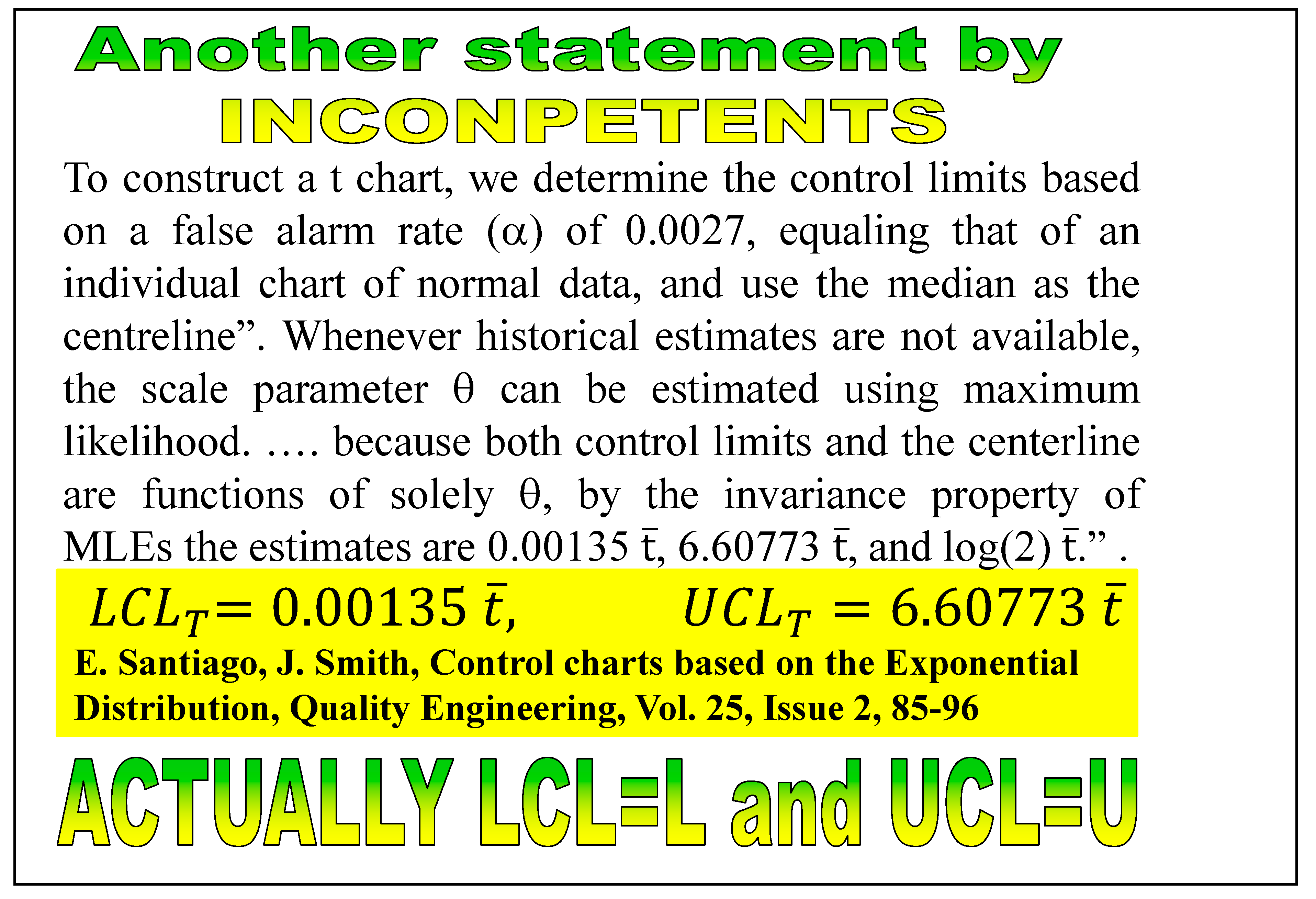

3.1. Some Papers from the “Garden …”

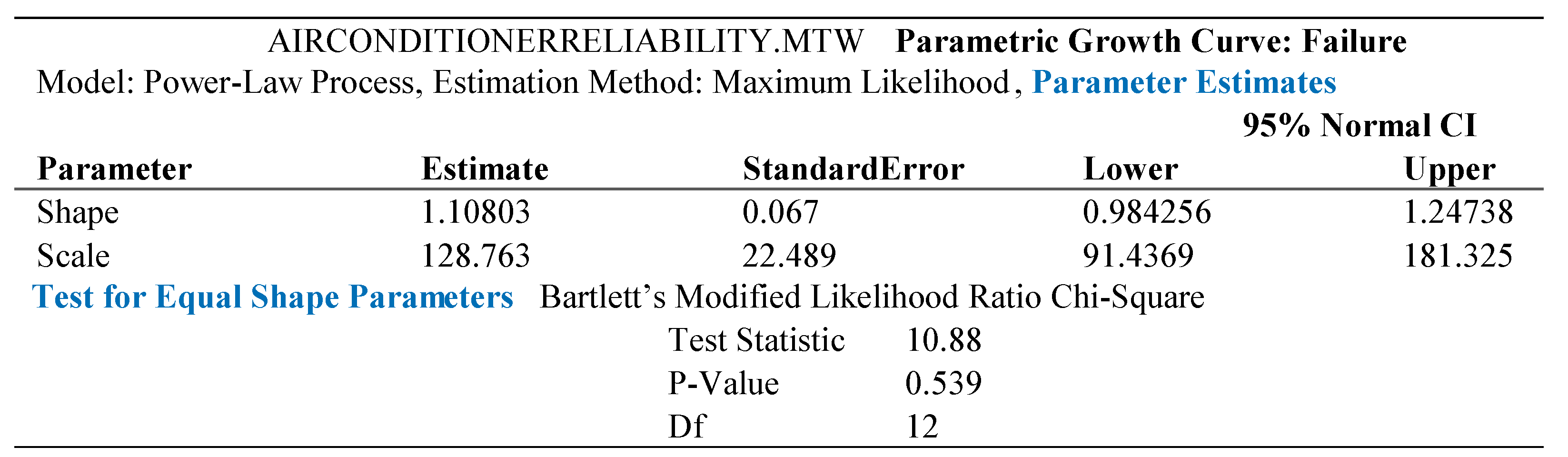

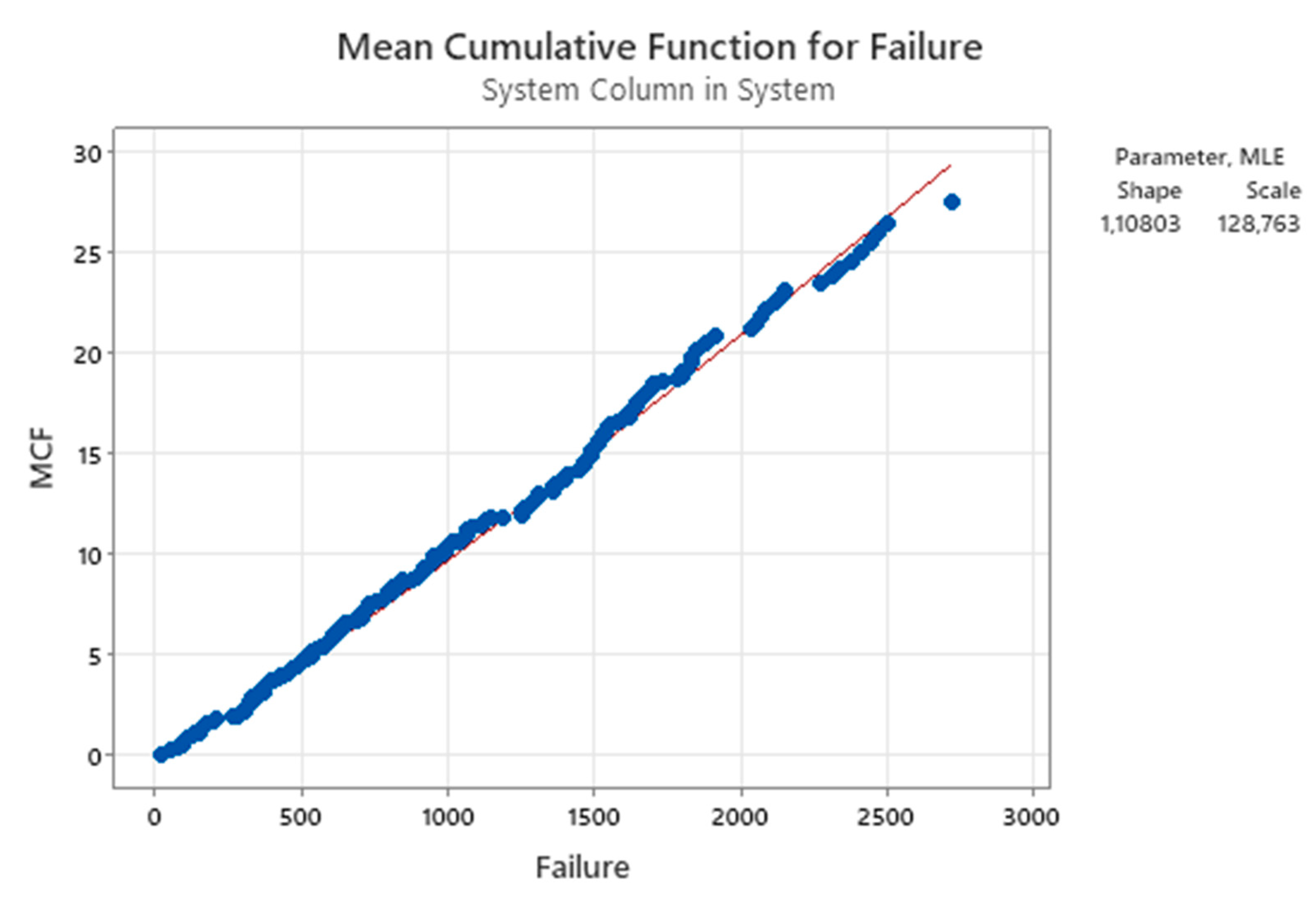

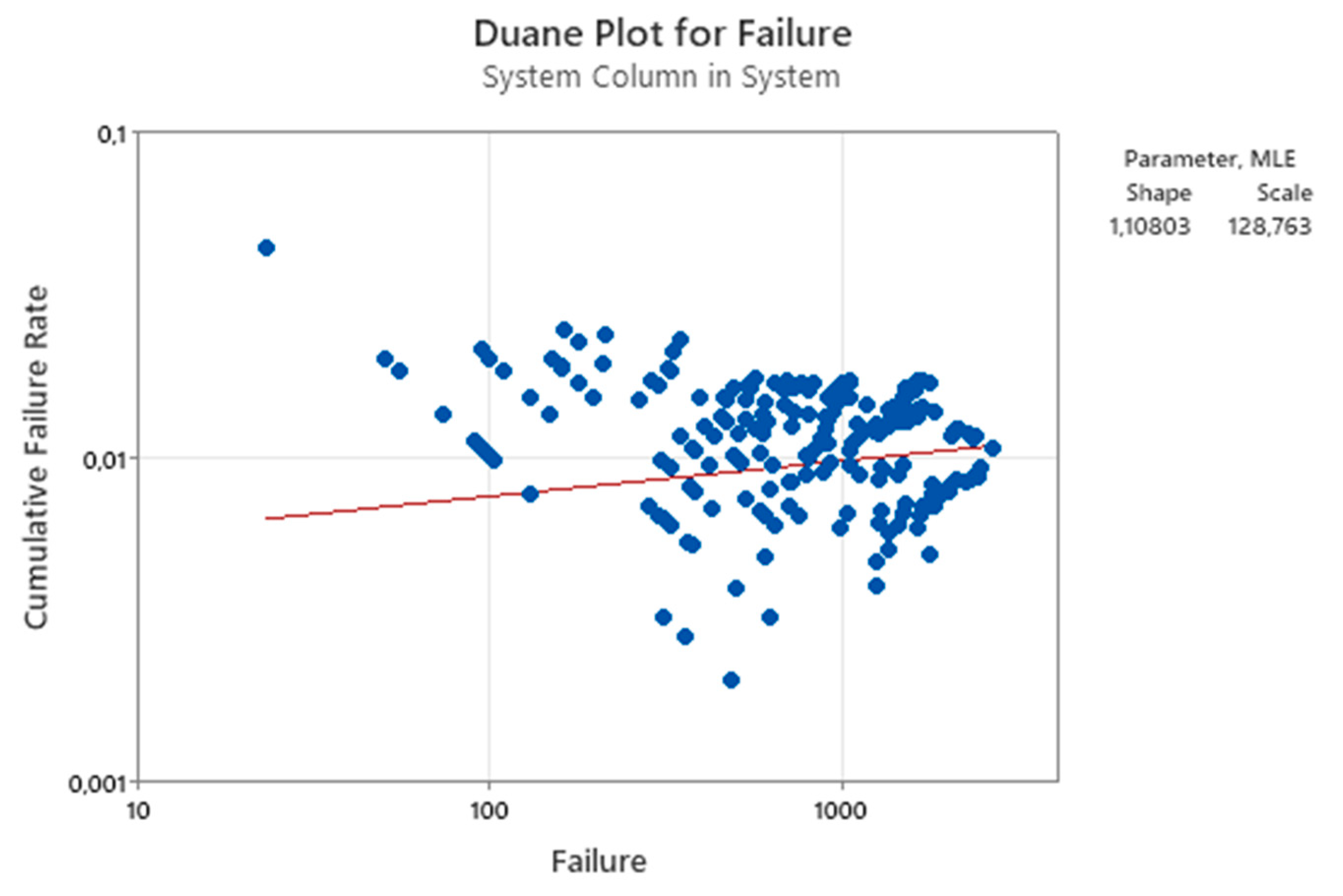

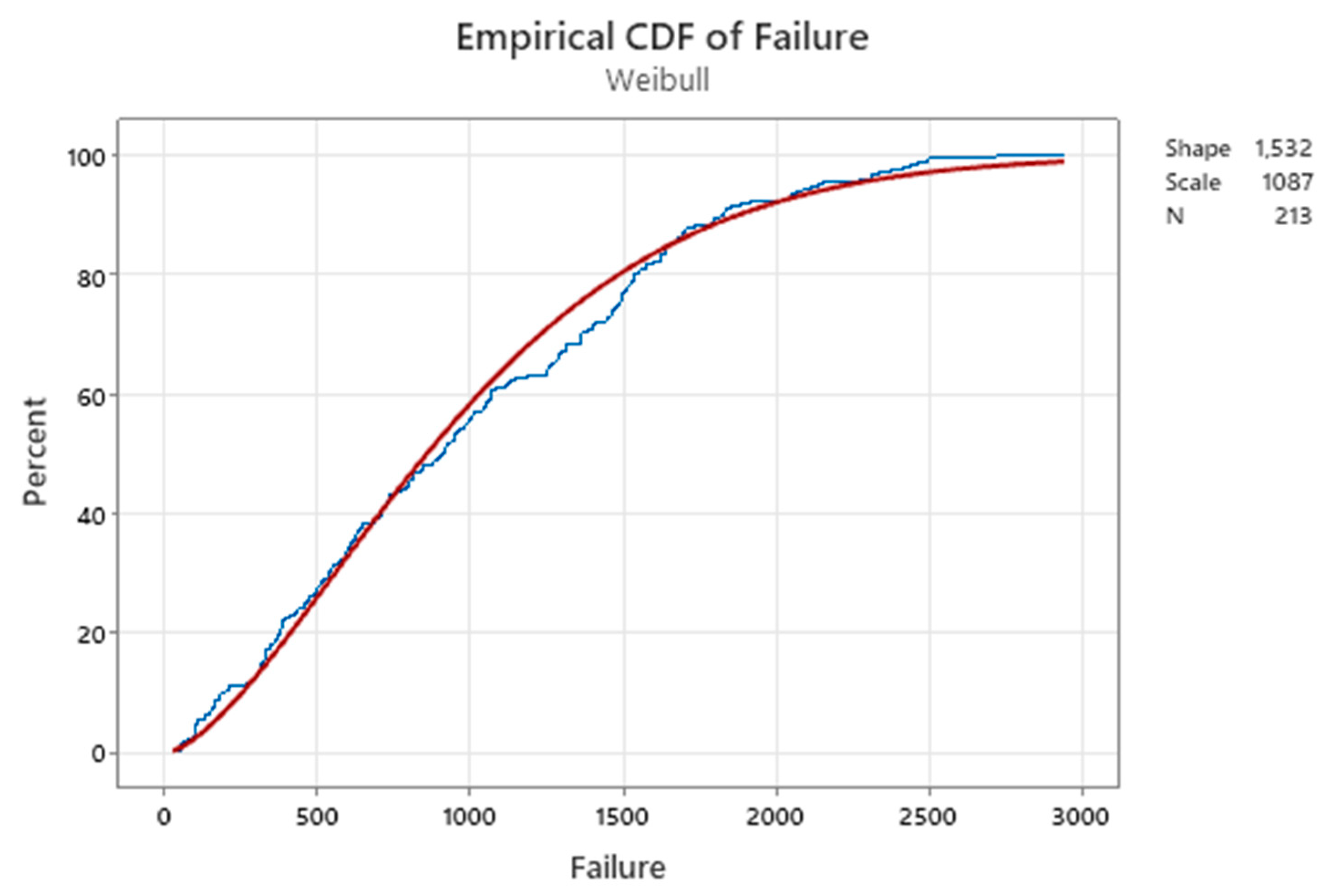

3.2. RIT and the Duane Method

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCL, UCL | Control Limits of the Control Charts (CCs) |

| L, U | Probability Limits related to a probability 1-α |

| θ | Parameter of the Exponential Distribution |

| θL-----θU | Confidence Interval of the parameter θ |

| RIT | Reliability Integral Theory |

Appendix A

References

- Feller, W. (1967) An Introduction to Probability Theory and its Applications, Vol. 1, 3rd Ed. Wiley.

- Feller, W. (1965) An Introduction to Probability Theory and its Applications, Vol. 2, Wiley.

- Parzen, E. (1999) Stochastic Processes, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Papoulis, A. (1991) Probability, Random Variables and Stochastic Processes, 3rd Ed. McGraw-Hill.

- Jones, P., Smith, P. (2018) Stochastic Processes An Introduction, 3rd Ed. CRC Press.

- Knill, O. (2009) Probability Theory and Stochastic Processes with Applications, Overseas Press.

- Shannon, Weaver (1949) The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press.

- Dore, P., (1962) Introduzione al Calcolo delle Probabilità e alle sue applicazioni ingegneristiche, Casa Editrice Pàtron, Bologna.

- Cramer, H., (1961) Mathematical Methods of Statistics, Princeton University Press.

- Kendall, Stuart, (1961) The advanced Theory of Statistics, Volume 2, Inference and Relationship, Hafner Publishing Company.

- Mood, Graybill, (1963) Introduction to the Theory of Statistics, 2nd ed., McGraw Hill.

- Rao, C. R., (1965) Linear Statistical Inference and its Applications, Wiley & Sons.

- Belz, M., (1973) Statistical Methods in the Process Industry, McMillan.

- Rozanov, Y., (1975) Processus Aleatoire, Editions MIR, Moscow, (traduit du russe).

- Ryan, T. P., (1989) Statistical Methods for Quality Improvement, Wiley & Sons.

- Casella, Berger, (2002) Statistical Inference, 2nd edition, Duxbury Advanced Series.

- Galetto, F., (1981, 84, 87, 94) Affidabilità Teoria e Metodi di calcolo, CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (1982, 85, 94) “Affidabilità Prove di affidabilità: distribuzione incognita, distribuzione esponenziale”, CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (1995/7/9) Qualità. Alcuni metodi statistici da Manager, CUSL, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2010) Gestione Manageriale della Affidabilità”, CLUT, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2015) Manutenzione e Affidabilità, CLUT, Torino (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2016) Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, Vol-1, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., (2016) Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, Vol-2, www.morebooks.de.

- Deming W. E., (1986) Out of the Crisis, Cambridge University Press.

- Deming W. E., (1997) The new economics for industry, government, education, Cambridge University Press,.

- Juran, J., (1988) Quality Control Handbook, 4th ed, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Juran, Godfrey (1998) Quality Control Handbook, 5th ed, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Shewhart W. A., (1931) Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Products, D. Van Nostrand Company.

- Shewhart W.A., (1936) Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control Graduate School, Washington.

- Galetto, F., (2015) Hope for the Future: Overcoming the DEEP Ignorance on the CI (Confidence Intervals) and on the DOE (Design of Experiments, Science J. Applied Mathematics and Statistics. Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 70-95. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Wheeler, “The normality myth”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Probability limits”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Are you sure we don’t need normally distributed data?” Online available from Quality Digest.

- D. J. Wheeler, “Phase two charts and their Probability limits”, Online available from Quality Digest.

- Galetto, F., 2019, Statistical Process Management, ELIVA press ISBN 9781636482897.

- Galetto, F., (1989) Quality of methods for quality is important, EOQC Conference, Vienna,.

- Galetto, F., (2015) Management Versus Science: Peer-Reviewers do not Know the Subject They Have to Analyse, Journal of Investment and Management. Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 319-329. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2015) The first step to Science Innovation: Down to the Basics., Journal of Investment and Management. Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 319-329. [CrossRef]

- Galetto F., (2021) Minitab T charts and quality decisions, Journal of Statistics and Management Systems. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2012) Six Sigma: help or hoax for Quality?, 11th Conference on TQM for HEI, Israel.

- Galetto, F., (2020) Six Sigma_Hoax against Quality_Professionals Ignorance and MINITAB WRONG T Charts, HAL Archives Ouvert, 2020.

- Galetto, F., (2021) Control Charts for TBE and Quality Decisions, submitted.

- Galetto F. (2022), “Affidabilità per la manutenzione Manutenzione per la disponibilità”, tab edezioni, Roma (Italy), ISBN 978-88-92-95-435-9, www.tabedizioni.it.

- Galetto F. (2021) ASSURE: Adopting Statistical Significance for Understanding Research and Engineering, Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Technology, ISSN: 2634 – 8853, 2021 SRC/JEAST-128. [CrossRef]

- Galetto F. (2023) Control Charts, Scientific Derivation of Control Limits and Average Run Length, International Journal of Latest Engineering Research and Applications (IJLERA) ISSN: 2455-7137 Volume – 08, Issue – 01, January 2023, PP – 11-45.

- Galetto, F., (1999) GIQA the Golden Integral Quality Approach: from Management of Quality to Quality of Management, Total Quality Management (TQM), Vol. 10, No. 1. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2004) Six Sigma Approach and Testing, ICEM12 –12th International Conference on Experimental Mechanics, 2004, Bari Politecnico (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2006) Quality Education and quality papers, IPSI, Marbella (Spain).

- Galetto, F., (2006) Quality Education versus Peer Review, IPSI, Montenegro.

- Galetto, F., (2006) Does Peer Review assure Quality of papers and Education? 8th Conference on TQM for HEI, Paisley (Scotland).

- Montgomery D., (1996, 2009, 2011) Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, Wiley & Sons (wrong definition of the term "Quality", and many other drawbacks in wrong applications).

- Montgomery D., (2019) “Introduction to Statistical Quality Control”, 8th Wiley & Sons.

- Galetto, F., “Design Of Experiments and Decisions, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach”, 2016, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., “The Six Sigma HOAX versus the versus the Golden Integral Quality Approach LEGACY”, 2017, www.morebooks.de.

- Galetto, F., “Quality Education on Quality for Future Managers”, 1st Conference on TQM for HEI (Higher Education Institutions), 1998, Toulone (France).

- Galetto, F., “Quality Education for Professors teaching Quality to Future Managers”, 3rd Conference on TQM for HEI, 2000, Derby (UK).

- Galetto, F., “Quality, Bayes Methods and Control Charts”, 2nd ICME 2000 Conference, 2000, Capri (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Looking for Quality in "quality books", 4th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2001, Mons (Belgium).

- Galetto, F., “Quality and Control Carts: Managerial assessment during Product Development and Production Process”, AT&T (Society of Automotive Engineers), 2001, Barcelona (Spain).

- Galetto, F., “Quality QFD and control charts: a managerial assessment during the product development process”, Conference ATA, 2001, Florence (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Business excellence Quality and Control Charts”, 7th TQM Conference, 2002, Verona (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Fuzzy Logic and Control Charts”, 3rd ICME 2002 Conference, Ischia (Italy).

- Galetto, F., “Analysis of "new" control charts for Quality assessment”, 5th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2002, Lisbon (Portugal).

- Galetto, F., “The Pentalogy, VIPSI, 2009, Belgrade (Serbia).

- Galetto, F., The Pentalogy Beyond, 9th Conference on TQM for HEI, 2010, Verona (Italy).

- Galetto, F., Papers and Documents in Academia.edu, 2015-2025.

- Galetto, F., Several Papers and Documents in the Research Gate Database, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).