1. Introduction

Deafness or hearing loss is the partial or total loss of the ability to hear sounds in one or both ears. The World Health Organization’s most recent World Hearing Report [

1] estimates that more than 1.5 billion people have some degree of hearing loss. Approximately 430 million people have moderate or greater hearing loss in the better ear, and it is expected to increase to 700 million people by 2050.

According to the Ministry of Health [

2], approximately 2.3 million people in Mexico have hearing disabilities. This vulnerable group faces significant levels of discrimination and limited employment opportunities. Additionally, this health condition restricts access to education, healthcare, and legal services, further exacerbating social inequalities and limiting opportunities for integration. One of the primary challenges faced by the deaf community is communication with hearing individuals, as linguistic differences hinder social and workplace interactions. While technology has proven useful in reducing some of these barriers, deaf individuals often rely on the same technological tools as the hearing population, such as email and text messaging applications. However, these tools are not always effective, as not all deaf individuals are proficient in written Spanish.

In the Americas, the most widely studied sign languages are the American Sign Language (ASL) and the Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS), which have facilitated research and technological advancements aimed at improving communication with the deaf community. An example of such innovation is SLAIT [

3], a startup that emerged from a research project at Aachen University of Applied Sciences in Germany. During this research, an ASL recognition engine was developed using MediaPipe and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Similarly, [

4] announced an innovative project in Brazil that uses computer vision and artificial intelligence to translate from LIBRAS to text and speech in real time. Although this technology is still undergoing internal testing, the developers claim that after four years of work, the system has reached a significant level of maturity. This technology was developed by Lenovo researchers in collaboration with the Center for Advanced Studies and Systems in Recife (CESAR), which has already patented part of this technology [

5]. The system is capable of recognizing the positions of arm joints, fingers, and specific points on the face, similar to SLAIT. From this data, it processes facial movements and gestures to identify sentence flow and convert it from sign language into text. CESAR and Lenovo consider that their system has the potential to become a universally applicable tool.

Compared to speech recognition and text translation systems, applications dedicated to sign language (SL) translation remain scarce. This is partly due to the relatively new nature of the field and the inherent complexity of sign language recognition (SLR); which involves visual, spatial, and gestural elements. Recognizing sign language presents a significant challenge, primarily due to limited research and funding. This highlights the importance of promoting research in the development of digital solutions that improve the quality of life of the deaf community (c.f. [

6]). However, researchers agree that the key factor for developing successful machine learning models is data (c.f. [

7]). In this regard, for SLs as the LSM, existing databases are often inadequate in terms of both size and quality, which hinders the advancement of these technologies. Also, the sensing technology has a fundamental role, in the reliability of the incoming data. This is the main reason that SLR is broadly divided into two branches: contact sensing and contactless sensing.

Sign data acquisition with contact depend on gloves [

8], armbands [

9], wearable inertial sensors [

10,

11], or Electromyographic (EMG) Signals [

12]. In contrast,

contactless sign data acquisition is mainly divided into two types, depending on the kind of hardware: simple hardware (color or infrared cameras) vs specialized hardware (depth sensors, optical 3D sensors [

13], commercial WiFi devices [

14], ultrasonic devices [

15]).

This classification is similar to the one presented by ([

16], Fig. 1), except that their sign data acquisition approaches are divided into sensor-based approaches and vision-based approaches. We present several examples of sign language research and related work, along with various approaches to sign data acquisition, as detailed in

Table 1.

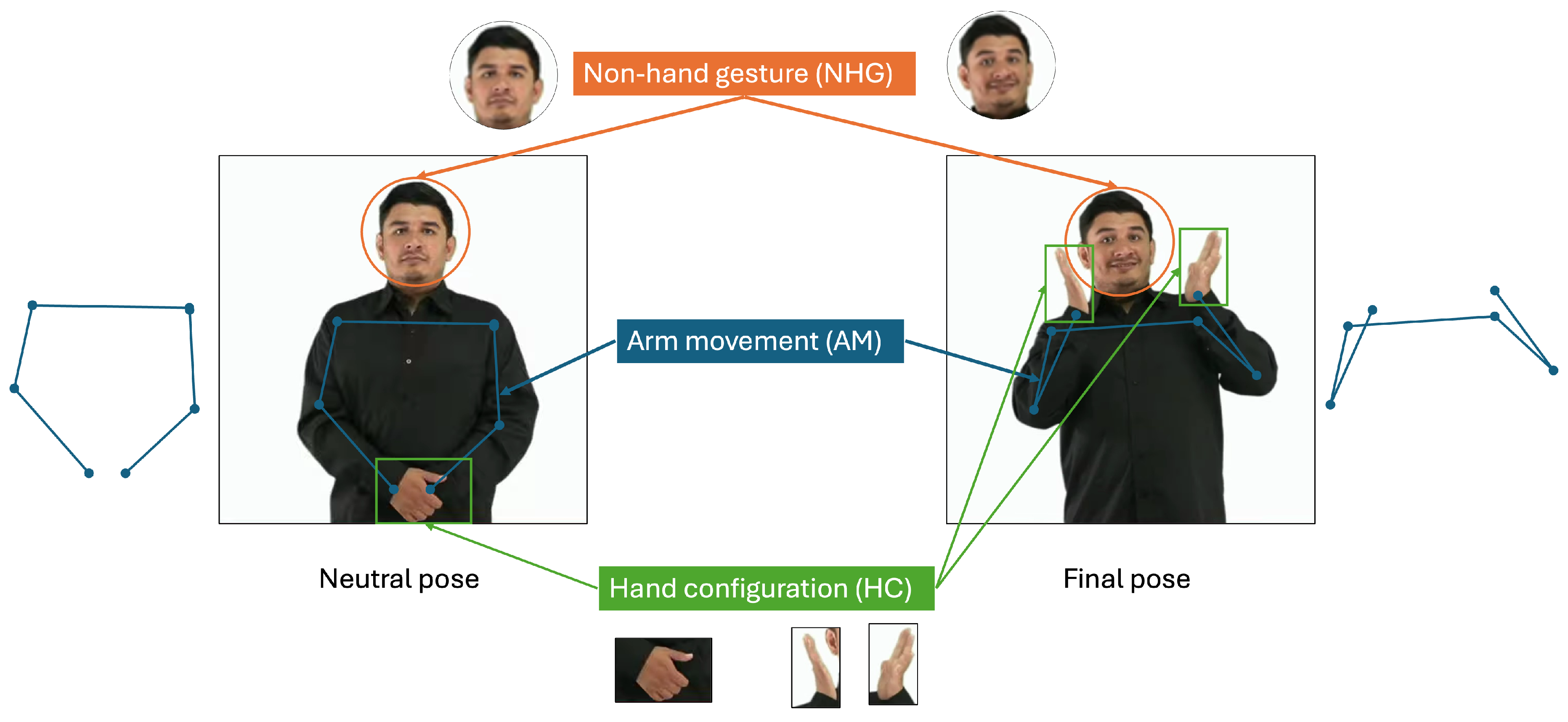

In

Table 1, we have included information regarding the features of signs that are included in the sign data acquisition, for each reported work. Instead of using the separation employed by [

22] (facial, body and hand features), we propose our own decomposition into hand configurations (HC), arm movement (AM) and non-hand gestures (NHG), see

Figure 1. This is a fundamental concept of our research, so this decomposition is discussed in more detail in

Section 1.1.2. The facial, body and hand features separation is a concept commonly seen in pose estimators —such as MediaPipe [

24]– that are also common in SL research, as presented in

Table 1. It is also possible to observe, that most SL research is focused on the HC features.

We will now present the scientific context of the LSM research. First, we present the known datasets and then studies about LSM recognition and analysis.

The LSM is composed by two parts: dactylology (fingerspelling) and ideograms ([

26], p.12). Dactylology is a small subset of the LSM and basically consists of letters of the alphabet, where the most part are static signs. A few signs for numbers are also static. Due to the small, nevertheless important, role of dactylology, we are interested in LSM ideograms datasets. To the best of our knowledge, there are three public available ideogram-focused datasets. Two of them are visual: (i) the MX-ITESO-100 preview [

27] with videoclips of 11 signs from 3 signers (out of 100 signs, but not all are currently available), and (ii) the Mexican sign language dataset [

28,

29] with image sequences of 249 signs from 11 signers. The third dataset, consisting in keypoints, is provided by [

30]; this dataset has 3000 samples of 30 signs from 4 signers (8 letters, 20 words and 2 phrases). This was constructed by processing the RGBD data into keypoints by means of MediaPipe [

24] tool, but the unprocessed visual data is not provided. A comparison of these datasets, along with LSM glossaries are provided in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Regarding LSM studies, most of the SLR research of the LSM focuses mainly on classifying static letters and numbers using classical machine learning techniques and convolutional neural networks (CNN) [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Using the classification provided by [

16], there are four classes of signs: (i) continuous signs, (ii) isolated signs, (iii) letter signs and (iv) number signs. In the LSM, most of the signs in the three last categories are static signs. But signing in the LSM is generally highly dynamic and continuous, since most signs are ideograms, as mentioned before.

In terms of dynamic sign recognition, early studies focused on classifying letters and numbers with motion. For example, [

42] used the CamShift algorithm to track the hand trajectory, generating a bitmap that captures the pixels of the hand path, these bitmaps are then classified using a CNN. Another approach, presented in [

43], is to obtain coordinates (

x,

y) of 22 key points of the hand using Intel RealSense sensor, which are used as training data for a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network. Finally, in [

44], 3D body cue points obtained with MediaPipe are used to train two recurrent neural network models (RNN): LSTM and GRU.

In more recent research, in addition to letters and numbers, some simple words and phrases have been included. Studies such as that of [

45,

46,

47], continue to use MLP-type neural networks. While others, such as [

30], use more advanced RNN models. In the case of [

27], CNNs are used to extract features from the frames of a series of videos, which will be the input data of an LSTM model.

On the other hand, the work of [

48] presents a method for the classification of dynamic signs, which involves the extraction of a sequence of frames, which go through a segmentation process using neural networks based on color, resulting on the skin of hands and face. To classify the signs, four classical machine learning algorithms are compared: bayesian classifier, decision trees, SVM and NN.

Although research on LSM recognition has been conducted for several years, progress in this area has been slow and limited compared to other SLs. A common approach is to use computer vision techniques such as CNNs to build automatic sign recognition systems. However, with the recent emergence of pose recognition models such as MediaPipe and YOLOv8, there is a trend in both LSM and other sign languages to use these tools to train more complex models such as RNNs or more sophisticated architectures such as Transformers. A comparison of the studies mentioned here, with additional details, is shown in

Table 4.

1.1. Towards a Recognition System for the LSM

We present the sign data acquisition, the hardware selected and the fundamental concepts of our research towards a recognition system for the LSM.

1.1.1. Contactless Sign Data Acquisition with Simple Hardware

Due to the socioeconomic conditions of the main users of the LSM, this research uses contactless simple hardware for the sign data acquisition; i.e. a pure vision-based approach, since color cameras are widely accessible and available in portable devices, that are very common in Mexico. One important remark is —as presented in

Table 4— that only one LSM research work [

51] uses contact sensing for sign data acquisition.

1.1.2. Sign Features

From a Linguistics perspective, LSM signs present six documented parameters: basic articulatory parameters that simultaneously combine to form signs [

31,

56,

57,

58]. We propose a simplified Kinematics perspective, already shown in

Figure 1, that combines four of those parameters into Arm Movement (AM):

Hand configuration (HC): the shape adopted by one or both hands. As seen in

Table 1 and

Table 3, most research focuses on the HC only. Hand segmentation [

59] and hand pose detectors are very promising technologies for this feature. The number of HCs required to perform a sign is variable in the LSM, some examples regarding the number of HCs required for a sign are: number "

1" (1 HC), number "

9" (2 HCs), number "

15" (2 hands, 1 HCs), "

grandmother" (2 hands, 3 HCs). See

Appendix A, for samples these signs.

Non-hand gestures (NHG): refers to facial expressions (frowning, raising eyebrows), gestures (puffing out cheeks, blowing) and body movements (pitching, nodding). While most signs do not require non-hand gestures, some of the LSM signs do. Some signs that require one or more NHG are: "

How are you?", "

I’m sorry", "

Surprise!" (two NHGs of this sign are shown in

Figure 1). See

Appendix A, for links to samples of these signs.

-

Arm movement (AM): it can be characterized by tracking the joint movements of wrists, shoulders and elbows. It is enough to obtain the following basic articulatory parameters [

31,

56,

57,

58]:

- (a)

Articulation location: the location on the signer’s body or space where the signs are executed.

- (b)

Hand movement: the type of movement made by the joints from one point to another.

- (c)

Direction of movement: the trajectory followed by the hand when making the sign.

- (d)

Hand orientation: orientation of the palm of one or both hands, with respect to the signer’s body when making the manual configuration.

This part can be studied from pose-based approaches (c.f. [

21,

23] with pose estimation using AlphaPose).

Other decompositions have been proposed, in order to simplify sign analysis, such as ([

60], Fig. 1) were a LSM sign is decomposed into

fixed postures and

movements. We consider that this approach could loose important information, since transitions in hand postures are also important as documented in the Hamburg Notation System (

HamNoSys) [

61].

The use of pose estimators, in particular the use of MediaPipe, allow having information of face, hands and body features, c.f [

22,

30]. While, the use of pose estimator is quite frequent in SL research, there are still areas of improvements (c.f. [

17], Fig. 8) where they designed a PhBFC to improve mediapipe hand pose estimation) and complementary approaches like bimodal frameworks [

22] that show the current limitations of those estimators.

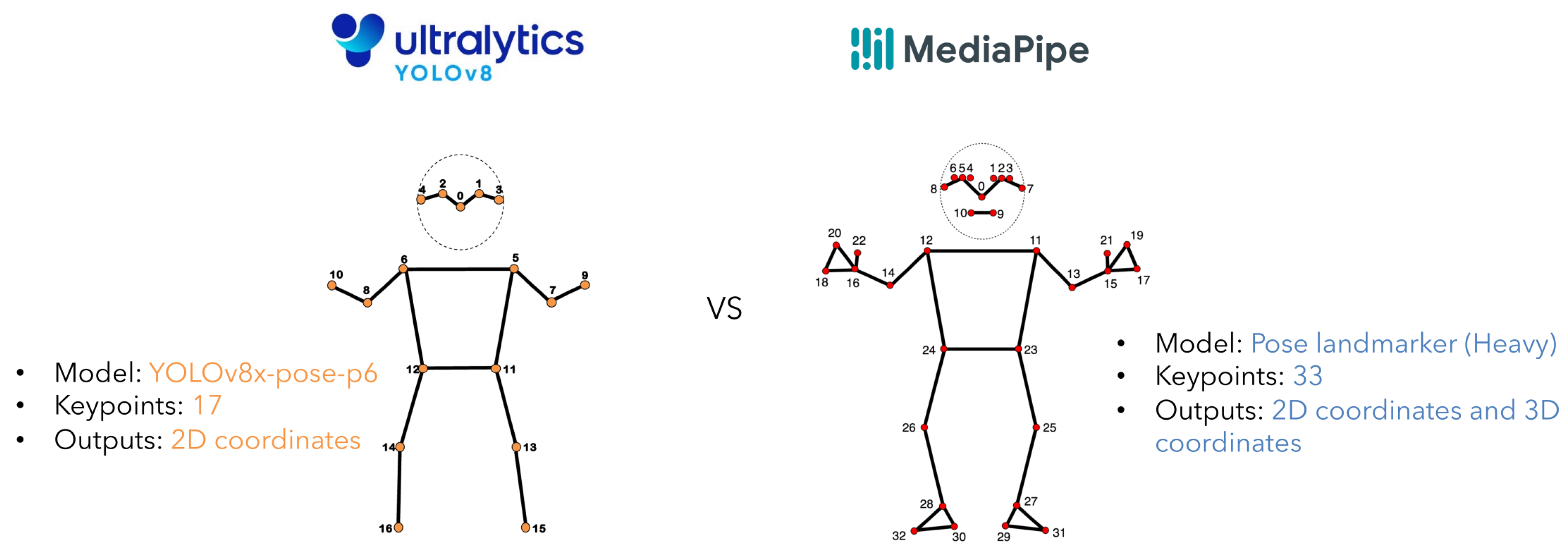

We consider that focusing on a single element to describe the LSM would not be adequate given their meaning and contribution to the sign. But covering everything at the same time is also very complex, as seen in most LSM research. Since most of the LSM work focused on HC, this paper focuses on the AM part and reports the approach created to analyze visual patterns in arm joint movements. Our current work uses YOLOv8 [

62,

63] for pose estimation. While it is 2D, and MediaPipe is better for 3D; we discuss our decision in

Section 2.3.1.

The main contribution of this work is the use of arm movement keypoints, particularly wrist position, as a partial feature for sign language recognition. This is motivated by the observation in [

30] that wrist location plays a crucial role in distinguishing similar signs. For instance, the same hand configuration used at different vertical positions (e.g., near the head to indicate headache, or near the stomach to indicate stomachache) conveys different meanings. By isolating and analyzing this spatial feature, we aim to better understand its discriminative power in sign recognition tasks.

An overview of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 describes the custom dataset, the experimental design, software and hardware, data processing and methodologies.

Section 3 describes the results from the analysis of two case studies. The conclusions and the limitations of our approach are presented in

Section 5.

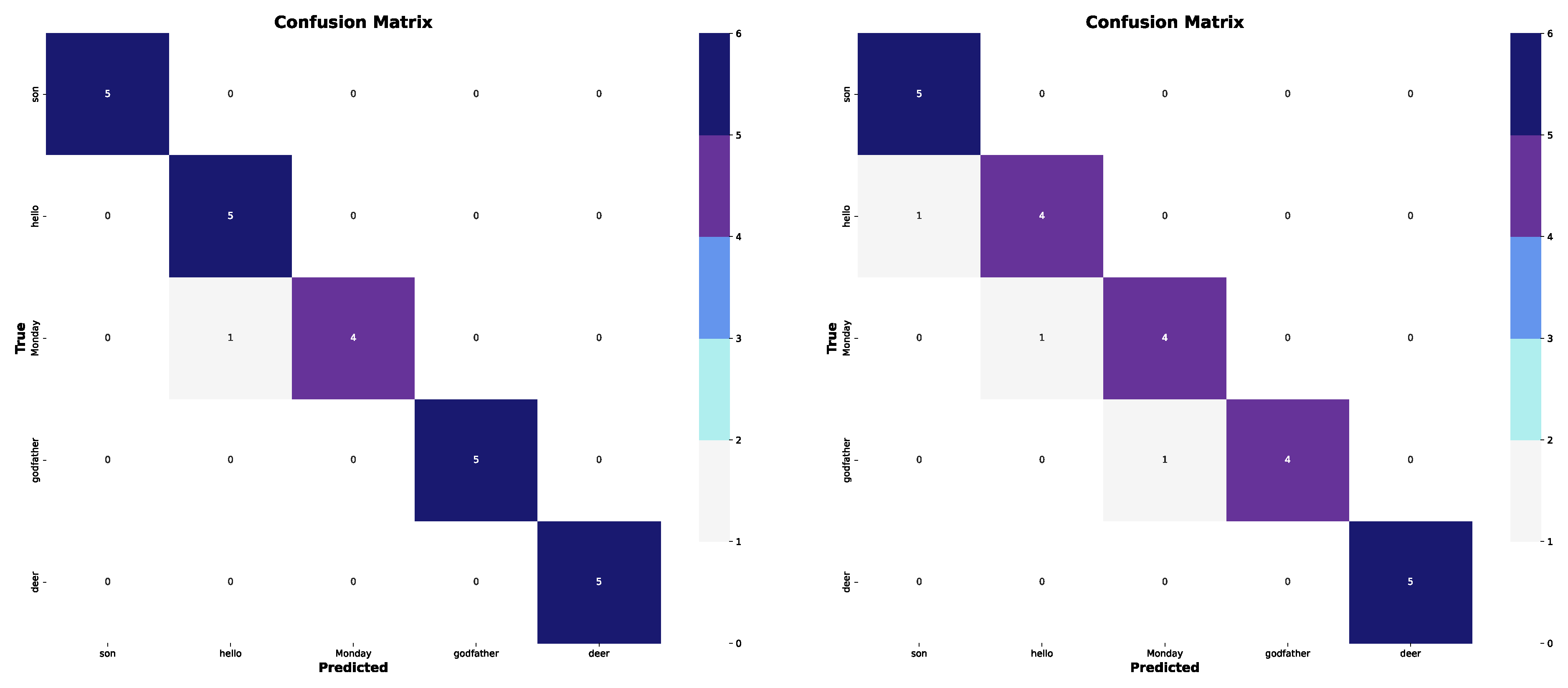

4. Discussion

Table 12 presents the accuracy values based on the Top-1 Accuracy metric obtained using the YOLOv8 model. The results indicate that including elbow coordinates led to better performance in two out of the three experiments. Although the improvement was modest (ranging from 3% to 4%), it suggests that incorporating additional joint information can contribute to more accurate classifications.

The experiments with various datasets allowed us to observe the behavior of the convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the input data. It became evident that the network’s performance is heavily influenced by the selection of classes. Using all available classes from the database is not always ideal, as this tends to yield suboptimal results. Therefore, a more focused approach, where only relevant classes are included, is recommended for improving model classification.

Despite certain limitations —such as the small number of examples per class, the presence of variants, and the high similarity between some signs— the neural network was still able to classify a significant number of signs correctly and recognize patterns in the movement data. This demonstrates the potential of the YOLOv8 model for this type of task.

In comparison to other CNNs, YOLOv8 stands out due to its optimized architecture, which allows for the use of pre-trained models on large datasets like ImageNet. This enables the model to achieve high accuracy and efficiency, making it suitable for real-time applications. However, as with any model, performance is largely dependent on the quality and quantity of the input data. In this case, the limited number of examples (17 per class) restricts the network’s ability to achieve optimal accuracy.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the ongoing work towards the creation of a recognition system for the LSM. A sign features decomposition is proposed into HC, AM and NHG. Contactless simple hardware was selected for sign signal acquisition. A custom proprietary dataset of 74 signs (70 words, 4 phrases) was constructed for this research. In contrast to most of the LSM research, this paper reports the analysis focused on the AM part of signs, instead of HC focused or a holistic approach (HC + AM + NHG).

The analysis were conducted through a series of classification experiments using YOLOv8, aimed at identifying visual patterns in the movement of key joints: wrists, shoulders, and elbows. A pose detection model was used to extract joint movements, followed by an image classification model (both integrated into YOLOv8) to classify the shapes generated by these movements.

The results, discussed in the previous section, highlight both the potential and the limitations of our approach. The experiments demonstrated that it is possible to classify a considerable number of signs, indicating that this dataset and strategy could serve as a useful tool for training a convolutional neural network (CNN), such as YOLOv8. However, the analysis also reveals that the current structure of the dataset, characterized by a limited number of examples, variations between classes, and high similarity among some signs, presents challenges that must be addressed through alternative approaches.

These experiments are the first stage of a larger project. For now, we are focusing on the analysis of arm movement (shoulders, elbows, and wrists) because it is a less studied feature and information can be extracted from it using a relatively simple methodology.

The comparison between the two case studies was intended to assess whether the inclusion of a greater number of keypoints improves the performance of the model. This seems to indicate that this assumption is correct. The next immediate step is to optimize these results, either by using a different convolutional neural network (CNN) or by exploring different architectures, such as recurrent neural networks (RNN), but keeping the focus on the use of keypoints; i.e. using pose-based approaches.

Later, the goal will be to integrate other essential components of sign language, such as manual configuration and non-hand gesture, to develop a more complete system. Ultimately, this will allow progress towards automatic sign language recognition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H.-A., K.O.-H. and M.C.; methodology, G.H.-A., K.O.-H. and M.C.; software, G.H.-A. and K.O.-H.; validation, G.H.-A.; formal analysis, G.H.-A., K.O.-H. and M.C.; investigation, G.H.-A., K.O.-H. and M.C.; resources, K.O.-H. and M.C.; data curation, G.H.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H.-A., K.O.-H. and I.L-J.; writing—review and editing, G.H.-A., K.O.-H., M.C. and I.L-J.; visualization, G.H.-A.; supervision, K.O.-H., and M.C.; project administration, K.O.-H.; funding acquisition, G.H.-A. and I.L-J.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Sign Features: hand configurations (HC), arm movement (AM) and non-hand gestures (NHG). "

Surprise!" sign images were taken from screenshots of the corresponding YouTube video of the GDLSM [

25], see

Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Sign Features: hand configurations (HC), arm movement (AM) and non-hand gestures (NHG). "

Surprise!" sign images were taken from screenshots of the corresponding YouTube video of the GDLSM [

25], see

Appendix A.

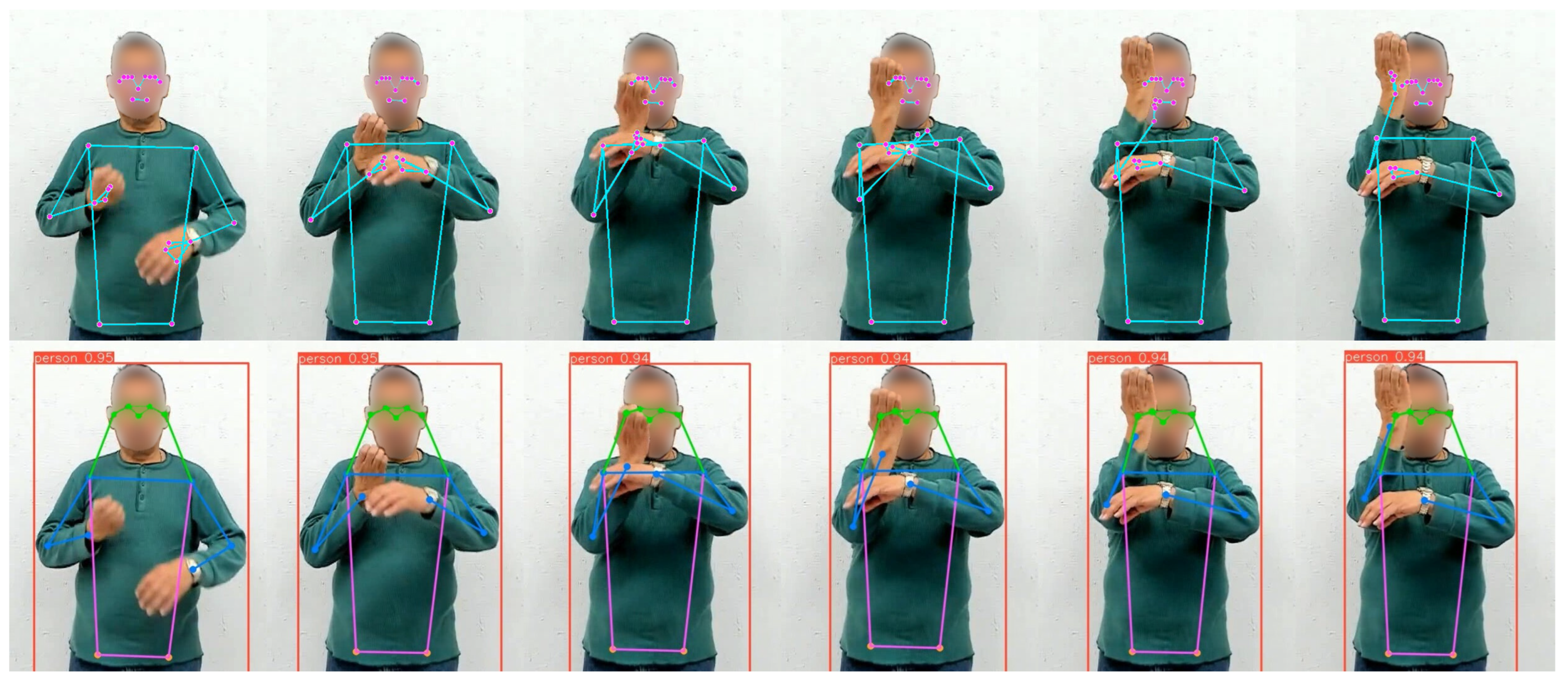

Figure 2.

Keypoints in YOLOv8 and MediaPipe.

Figure 2.

Keypoints in YOLOv8 and MediaPipe.

Figure 3.

Comparison in wrist joint tracking between YOLOv8 vs MediaPipe. Example with the "state" sign. Top row: MediaPipe. Bottom row: YOLOv8 pose detector. Four inner frames: MediaPipe loses track of the wrist joint; while YOLOv8 keeps track of the AM in all frames.

Figure 3.

Comparison in wrist joint tracking between YOLOv8 vs MediaPipe. Example with the "state" sign. Top row: MediaPipe. Bottom row: YOLOv8 pose detector. Four inner frames: MediaPipe loses track of the wrist joint; while YOLOv8 keeps track of the AM in all frames.

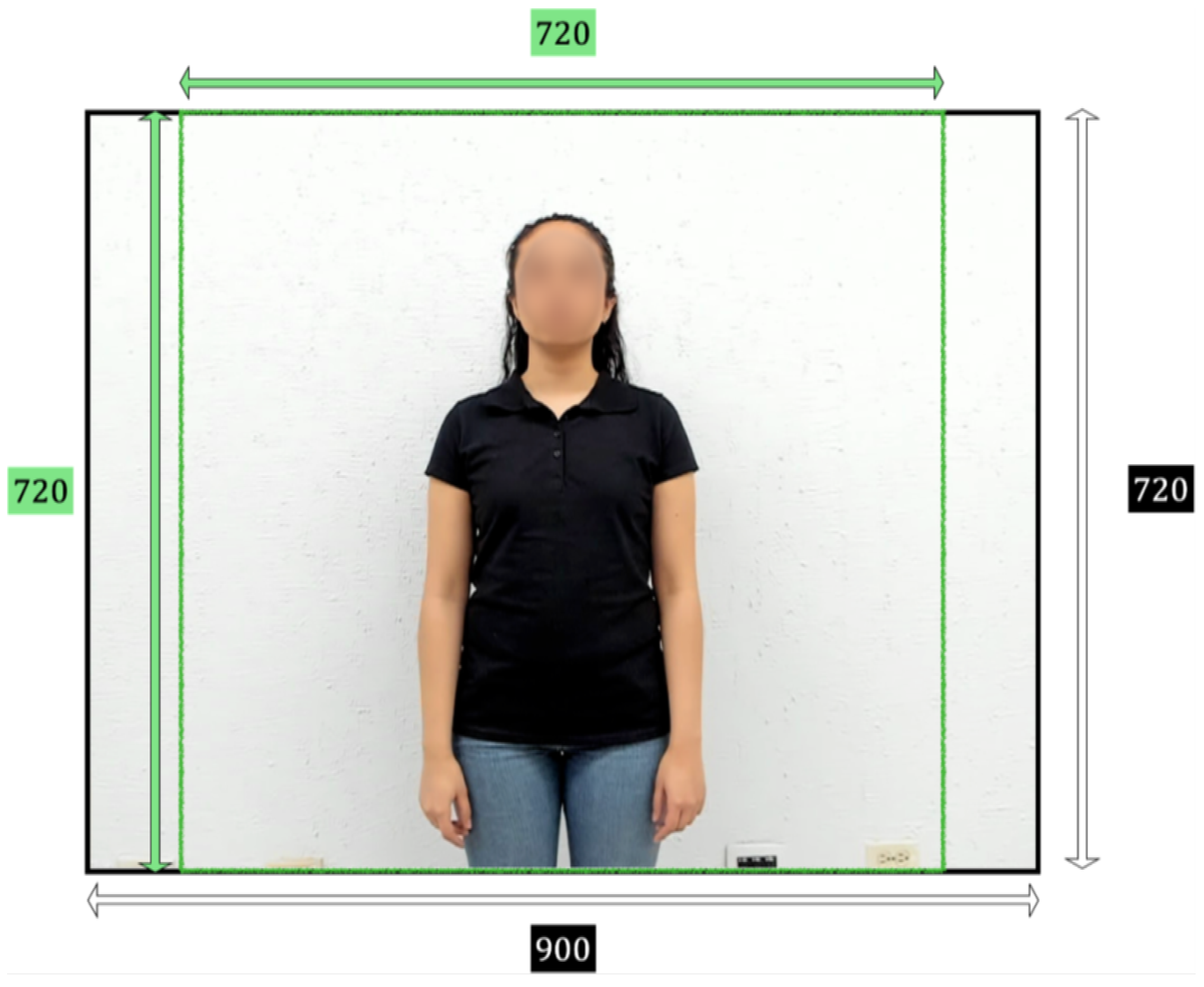

Figure 4.

Dimensions of original and cropped frames.

Figure 4.

Dimensions of original and cropped frames.

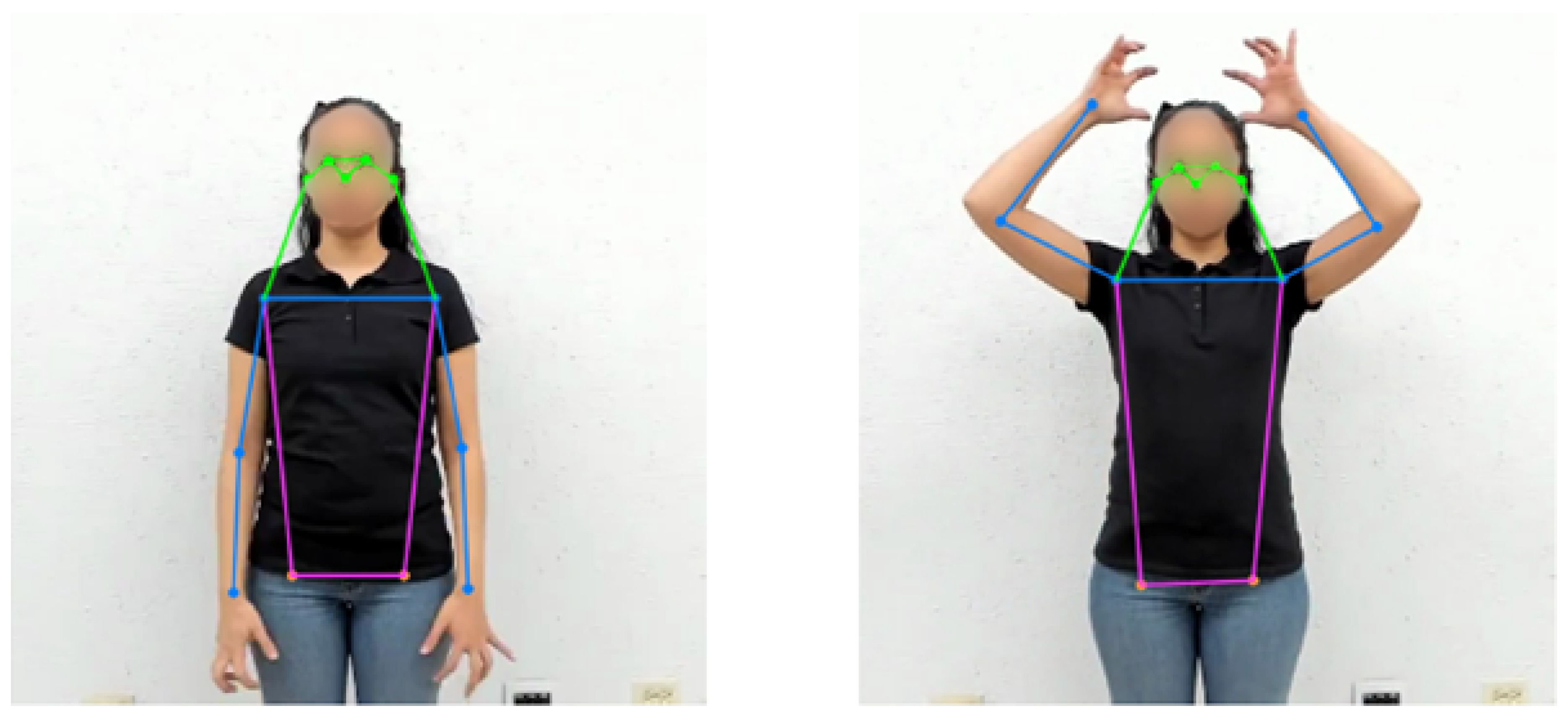

Figure 5.

Pose detection in the "deer" sign. Left: neutral pose. Right: final pose.

Figure 5.

Pose detection in the "deer" sign. Left: neutral pose. Right: final pose.

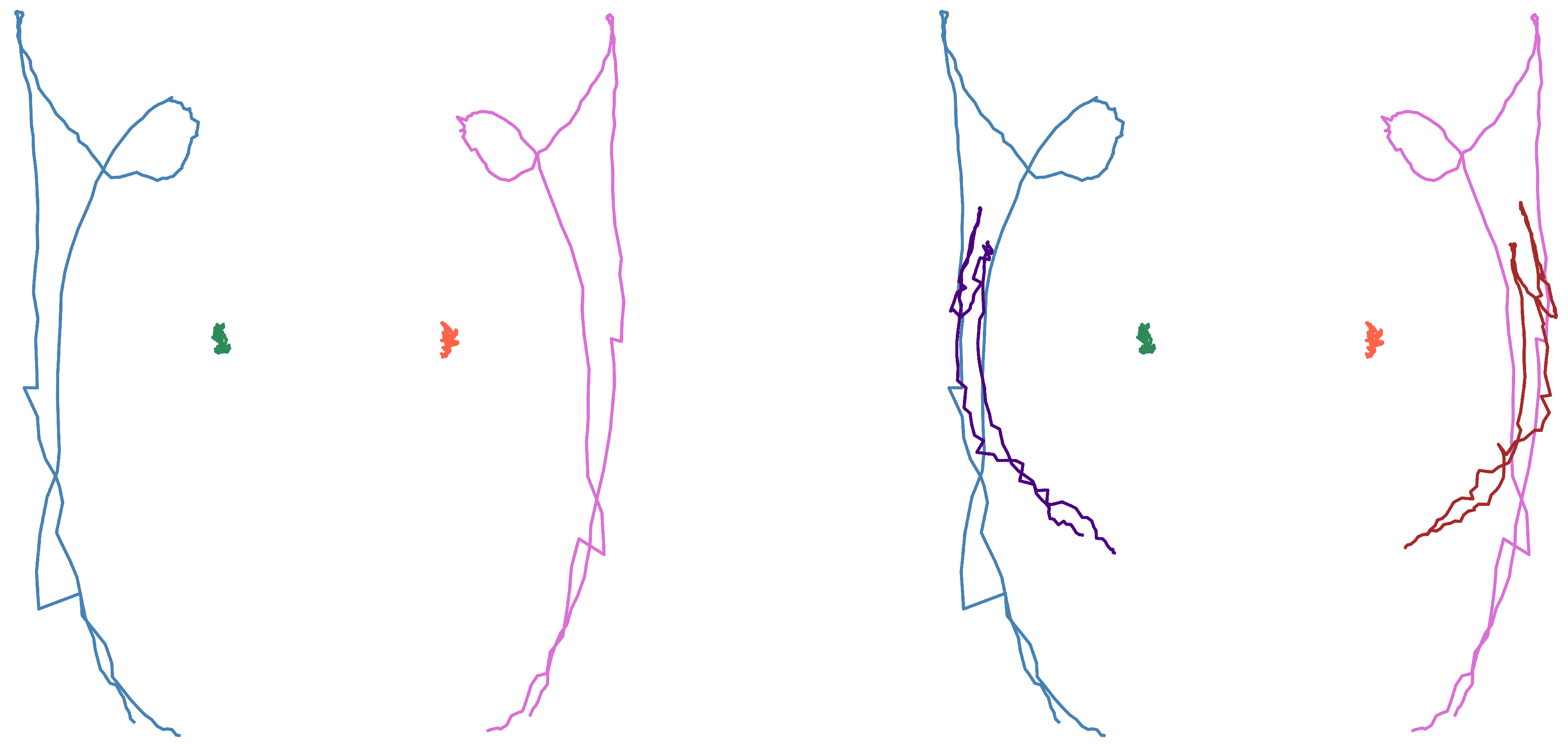

Figure 6.

Movement shapes for the "deer" sign. Left: only wrists and shoulder. Right: also elbows.

Figure 6.

Movement shapes for the "deer" sign. Left: only wrists and shoulder. Right: also elbows.

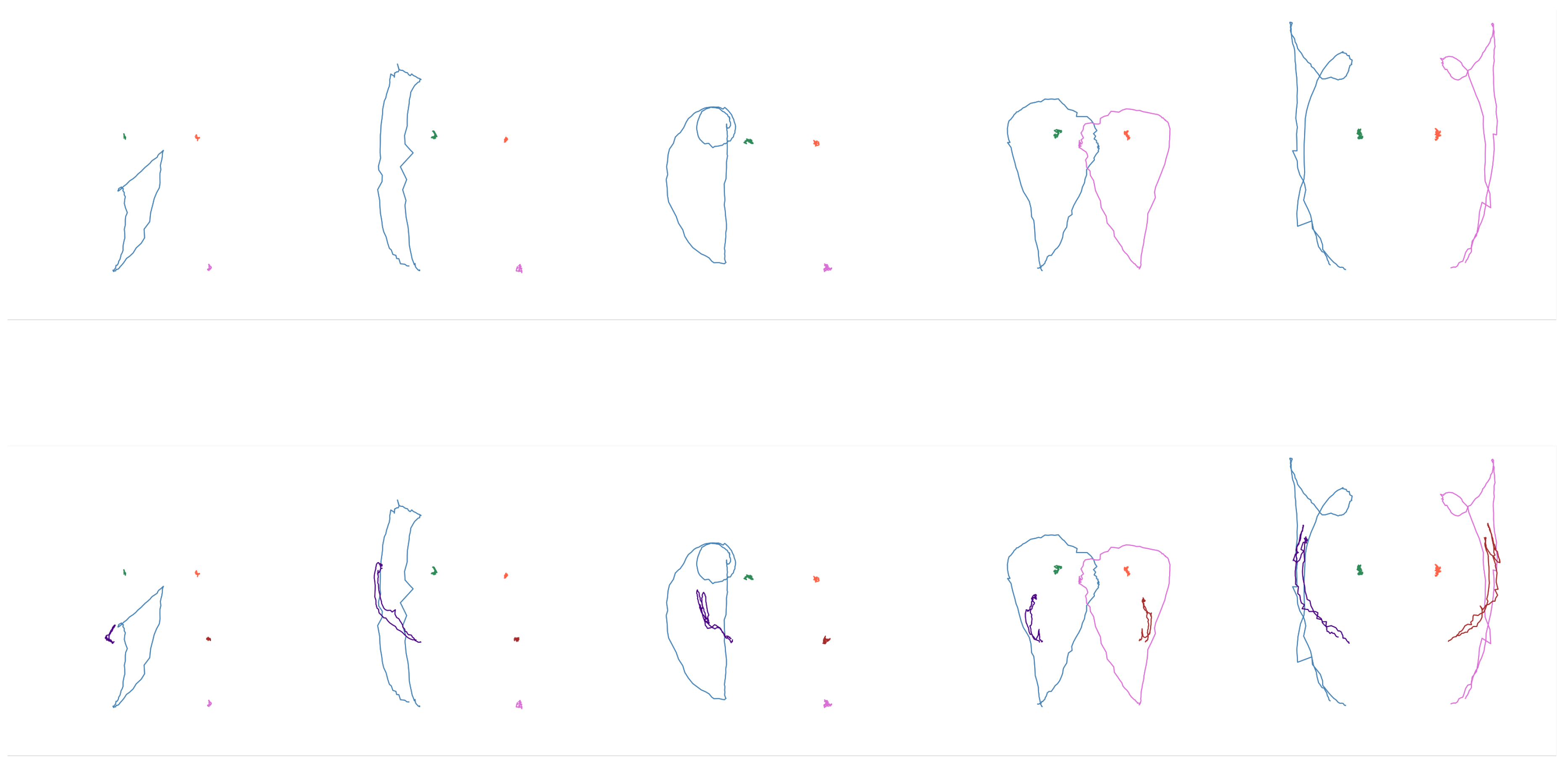

Figure 7.

Shapes of the first subset (see words in

Table 5). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

Figure 7.

Shapes of the first subset (see words in

Table 5). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

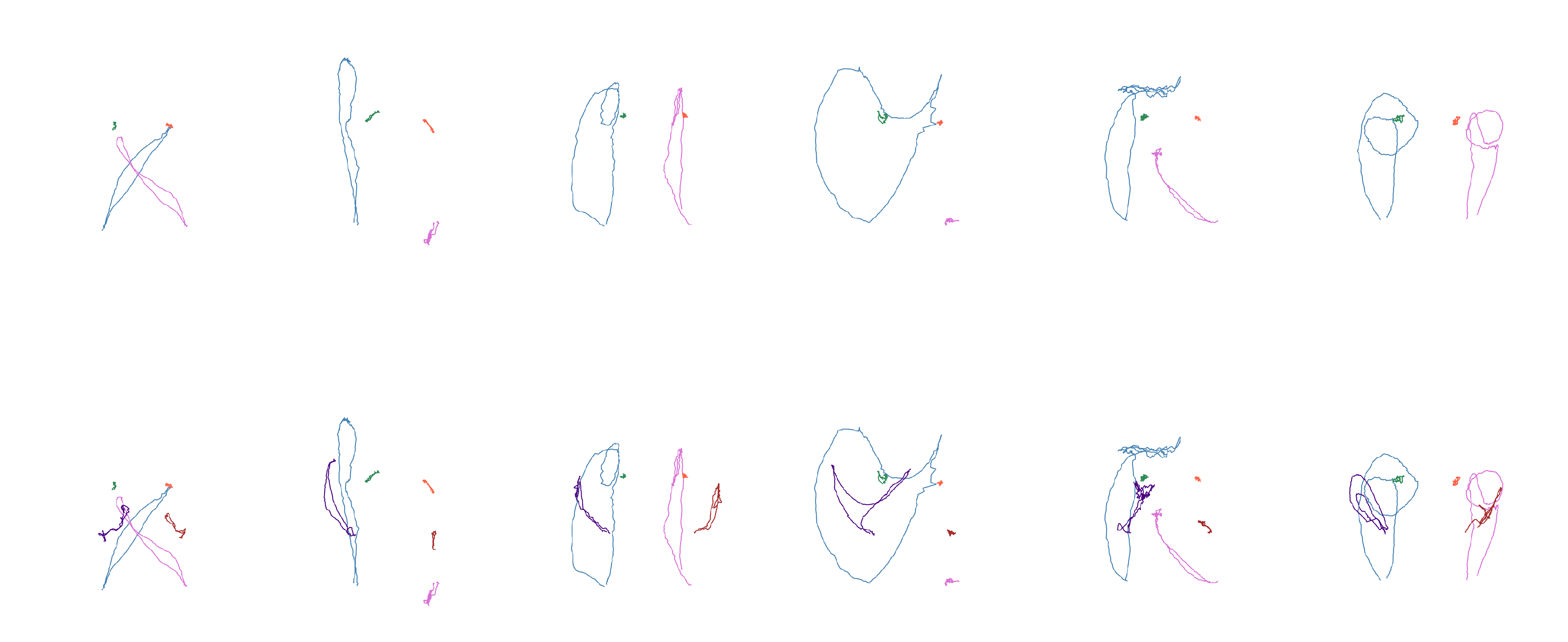

Figure 8.

Shapes examples of the second subset ("hug", "tall", "atole", "airplane", "flag" and "bicycle"). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

Figure 8.

Shapes examples of the second subset ("hug", "tall", "atole", "airplane", "flag" and "bicycle"). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

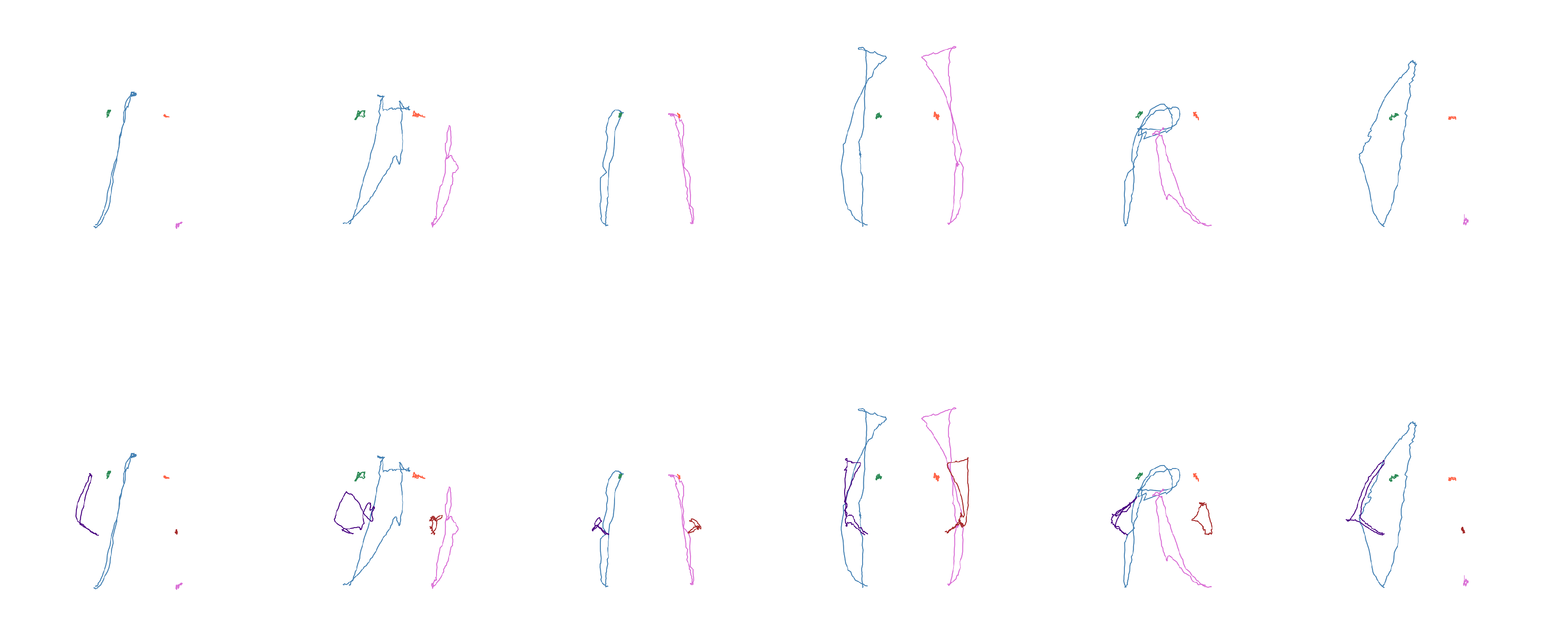

Figure 9.

Shapes examples of the third subset ("garbage", "trash can", "house", "curtains", "electricity" and "stairs"). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

Figure 9.

Shapes examples of the third subset ("garbage", "trash can", "house", "curtains", "electricity" and "stairs"). Top: only wrists and shoulders. Bottom: also elbows.

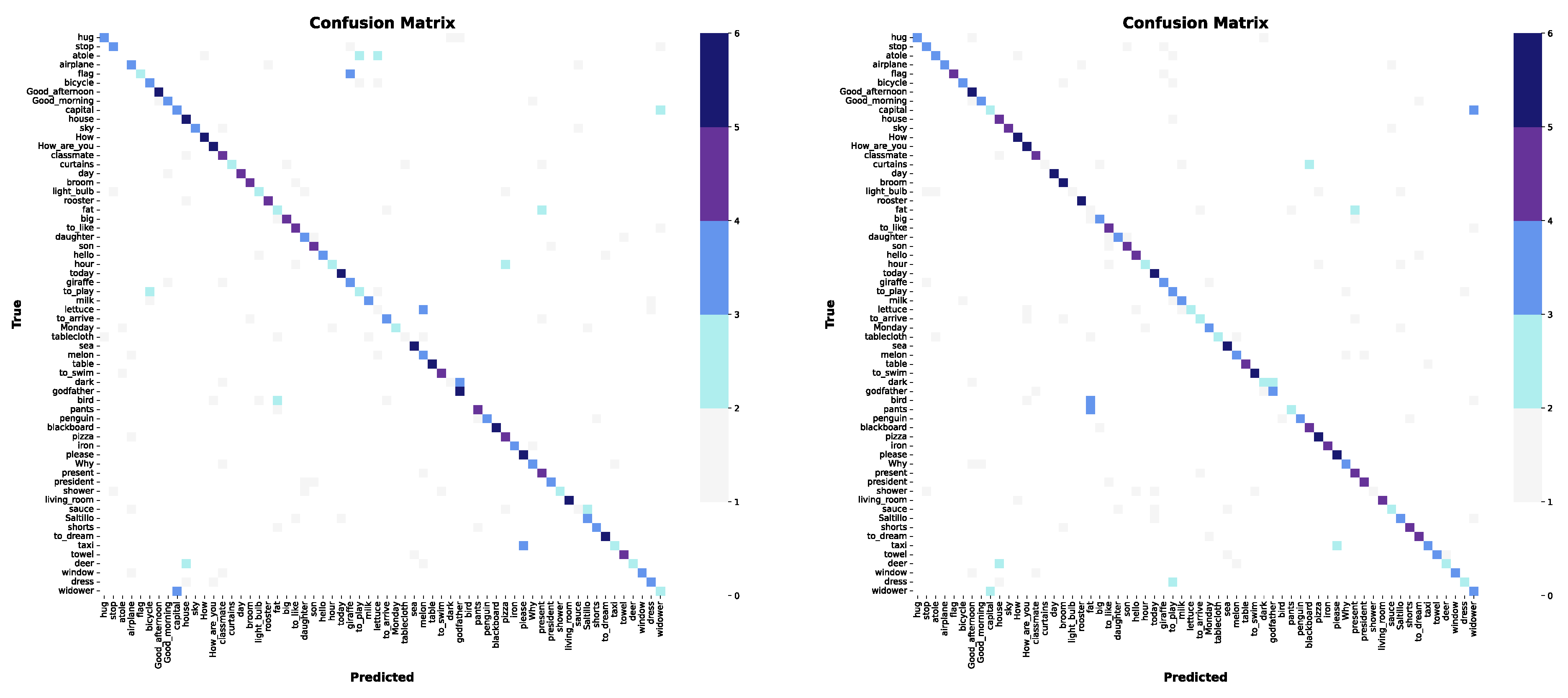

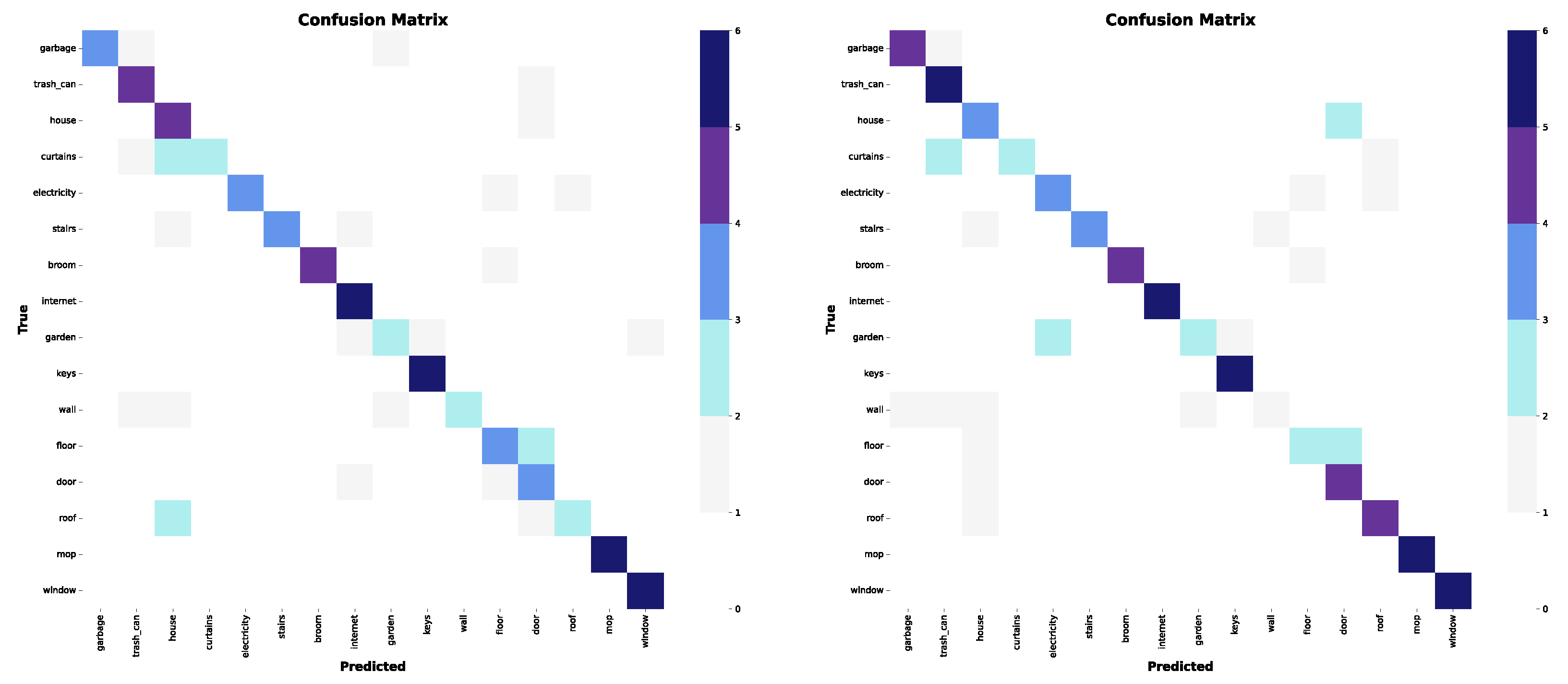

Figure 10.

Confusion matrices for the first subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrices for the first subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

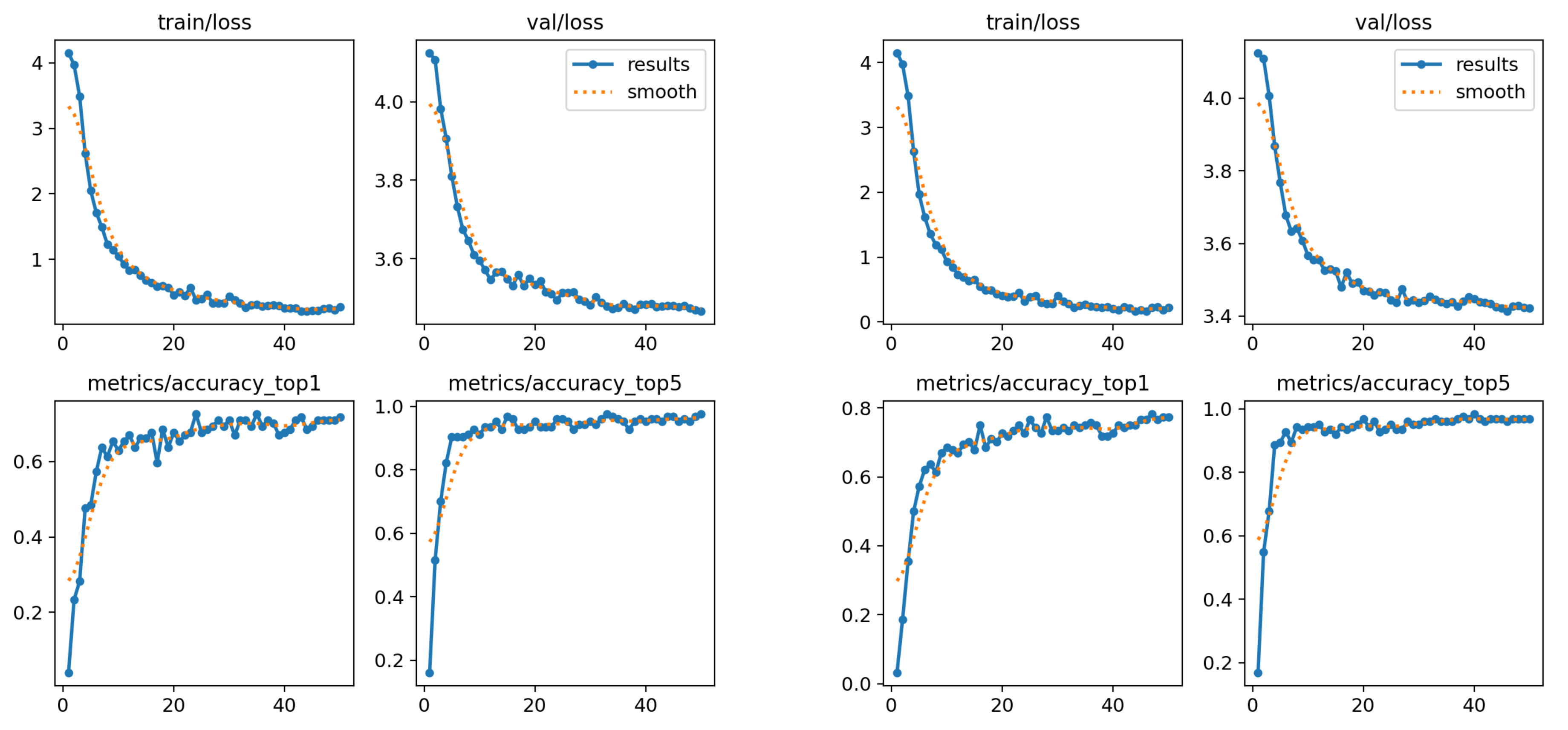

Figure 11.

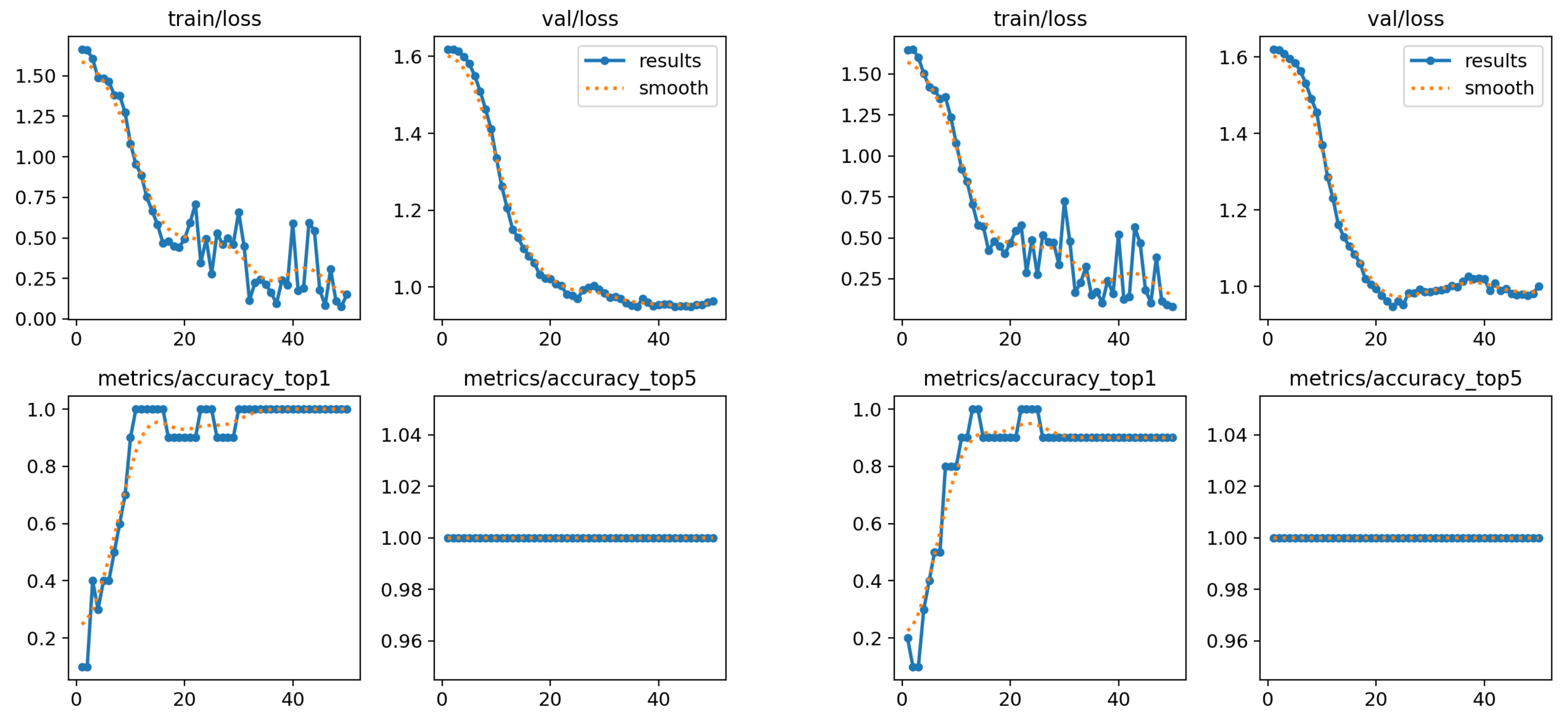

Performance charts for the first subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Figure 11.

Performance charts for the first subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrices for the third subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrices for the third subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

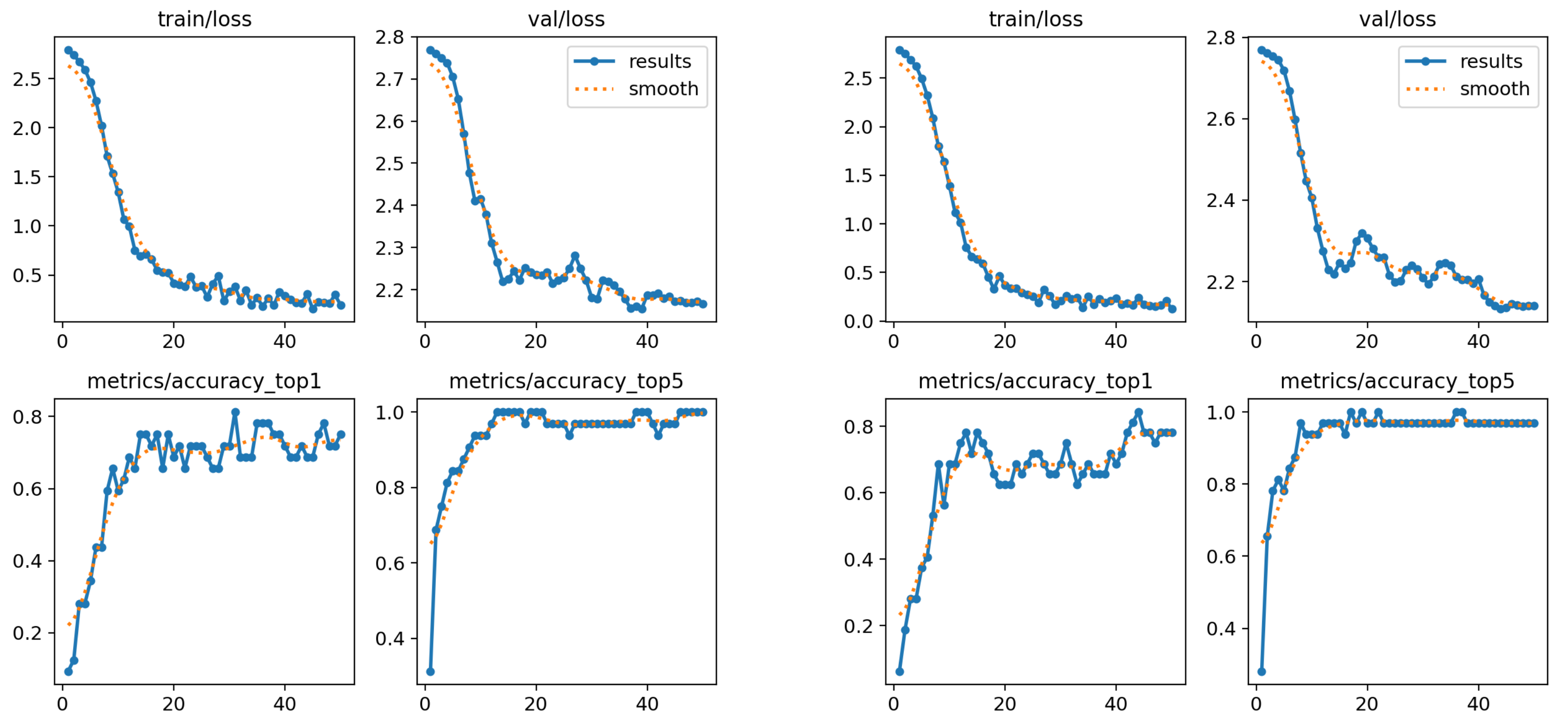

Figure 15.

Performance charts for the third subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Figure 15.

Performance charts for the third subset. Left: only wrists and shoulders. Right: also elbows.

Table 1.

Sign Language research and related work.

Table 1.

Sign Language research and related work.

| Ref. |

SL |

Sign group* |

Sign type |

Sign features†

|

Sensor/Tool |

| Chiradeja et al. (2025) [8] |

- |

S |

Dynamic |

HC |

Gloves |

| Rodríguez-Tapia et al. (2019) [10] |

ASL |

W |

Dynamic |

HC |

Myoelectrical bracelets |

| Filipowska et al. (2024) [12] |

PSL |

W |

Dynamic |

HC |

EMG |

| Umut and Kumdereli (2024) [9] |

TSL |

W |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

Myo armbands (IMU + sEMG) |

| Gu et al. (2024) [11] |

ASL |

W, S |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

IMUs |

| Urrea et al. (2023) [17] |

ASL |

L, W |

Static |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Al-Saidi et al. (2024) [16] |

ArSL |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Niu (2025) [18] |

ASL |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera |

| Hao et al. (2020) [14] |

- |

W |

Dynamic |

HC |

WiFi |

| Galván-Ruiz et al. (2023) [13] |

LSE |

W |

Dynamic |

HC |

Leap motion |

| Wang et al. (2023) [15] |

CSL |

W, P |

Dynamic |

HC |

Ultrasonic |

| Raihan et al. (2024) [19] |

BdSL |

L, N, W, P |

Dynamic |

HC |

Kinect |

| Woods and Rana (2023) [20] |

ASL |

W |

Dynamic |

AM, NHG |

Camera/OpenPose |

| Eunice et al. (2023) [21] |

ASL |

W |

Dynamic |

HC, AM, NHG |

Camera/Sign2Pose, YOLOv3 |

| Gao et al. (2024) [22] |

ASL, TSL |

W |

Dynamic |

HC, AM, NHG |

Camera, Kinect |

| Kim and Baek (2023) [23] |

DGS, KSL |

W, S |

Dynamic |

HC, AM, NHG |

Camera/AlphaPose |

| Current study |

LSM |

W, P |

Dynamic |

AM |

Camera/YOLOv8 |

Table 2.

LSM Datasets and Glossaries.

Table 2.

LSM Datasets and Glossaries.

| Ref. |

Type |

Sign group* |

Sign Signal |

Samples |

| DIELSEME 1 (2004) [31] |

Glossary†

|

535 W |

Visual |

1 video per sign |

| DIELSEME 2 (2009) [32] |

Glossary†

|

285 W |

Visual |

1 video per sign |

| GDLSM (2024) [25] |

Glossary |

27 L, 49 N, 667 W, 4 P |

Visual |

1 video per sign‡

|

| MX-ITESO-100 (2023) [27] |

Dataset |

96 W, 4 P |

Visual |

50 videos per sign |

| Mexican sign language dataset (2024) [29] |

Dataset |

243 W, 6 P |

Visual |

11 image sequences per sign |

| Mexican Sign Language Recognition (2022) [30] |

Dataset |

8 L, 20 W, 2 P |

Keypoints |

100 samples per sign |

Table 3.

LSM Datasets and Glossaries: Sign and signal properties.

Table 3.

LSM Datasets and Glossaries: Sign and signal properties.

| Ref. |

Sign Features |

Signal Properties |

File Format |

Comments |

| DIELSEME 1 (2004) [31] |

HC, AM*, NHG |

320×234 @ 12 fps |

SWF videos |

|

| DIELSEME 2 (2009) [32] |

HC, AM, NHG |

720×405 @ 30 fps |

FLV videos |

|

| GDLSM (2024) [25] |

HC, AM, NHG |

1920×1080 @ 60 fps |

videos |

Hosted on a streaming platform; c.f. Appendix A

|

| MX-ITESO-100 (2023) [27] |

HC, AM, NHG |

512×512 @ 30 fps |

MP4 videos |

Preview only‡

|

| Mexican sign language dataset (2024) [29] |

HC, AM* |

640×480 |

JPEG images |

Blurred faces |

| Mexican Sign Language Recognition (2022) [30] |

HC, AM, NHG |

20×201 array |

CSV files |

One row per frame, 67 keypoints |

Table 4.

LSM research.

| Ref. |

Sign group* |

Sign type |

Sign feature |

Sensor/Tool |

| Solís et al. (2016) [34] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera |

| Carmona-Arroyo et al. (2021) [35] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Leap Motion, Kinect |

| Salinas-Medina and Neme-Castillo (2021) [36] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera |

| Rios-Figueroa et al. (2022) [37] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Kinect |

| Morfín-Chávez et al. (2023) [38] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Sánchez-Vicinaiz et al. (2024) [39] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| García-Gil et al. (2024) [40] |

L |

Static |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Jimenez et al. (2017) [41] |

L, N |

Static |

HC |

Kinect |

| Martínez-Gutiérrez et al. (2019) [43] |

L |

Both |

HC |

RealSense f200 |

| Rodriguez et al. (2023) [44] |

L, N |

Both |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Rodriguez et al. (2025) [49] |

L, N |

Both |

HC |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Martinez-Seis et al. (2019) [42] |

L |

Both |

AM |

Camera |

| Mejía-Peréz et al. (2022) [30] |

L, W |

Both |

HC, AM, NHG |

OAK-D/MediaPipe |

| Sosa-Jiménez et al. (2022) [50] |

L, N, W |

Both |

HC, body but not NHG |

Kinect |

| Sosa-Jiménez et al. (2017) [45] |

W, P |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

Kinect/Pose extraction |

| Varela-Santos et al. (2021) [51] |

W |

Dynamic |

HC |

Gloves |

| Espejel-Cabrera et al. (2021) [48] |

W, P |

Dynamic |

HC |

Camera |

| García-Bautista et al. (2017) [46] |

W |

Dynamic |

AM |

Kinect |

| Martínez-Guevara and Curiel (2024) [52] |

W, P |

Dynamic |

AM |

Camera/OpenPose |

| Martínez-Guevara et al. (2019) [53] |

W |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

Camera |

| Trujillo-Romero and García-Bautista (2023) [47] |

W, P |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

Kinect |

| Martínez-Guevara et al. (2023

) [54] |

W, P |

Dynamic |

HC, AM |

Camera |

| Martínez-Sánchez et al. (2023) [27] |

W |

Dynamic |

HC, AM, NHG |

Camera |

| González-Rodríguez et al. (2024) [55] |

P |

Dynamic |

HC, AM, NHG |

Camera/MediaPipe |

| Current study |

W, P |

Dynamic |

AM |

Camera/YOLOv8 |

Table 5.

Signs for the first subset.

Table 5.

Signs for the first subset.

| No. |

Semantic field |

Sign |

| 1 |

family |

son* |

| 2 |

greetings |

hello* |

| 3 |

days of the week |

Monday* |

| 4 |

family |

godfather* |

| 5 |

animals |

deer* |

Table 6.

Signs for the second subset.

Table 6.

Signs for the second subset.

| No. |

Semantic field |

Sign |

No. |

Semantic field |

Sign |

| 1 |

verbs |

hug |

32 |

verbs |

to arrive |

| 2 |

adjectives |

tall |

33 |

days of the week |

Monday* |

| 3 |

drinks |

atole |

34 |

kitchen |

tablecloth |

| 4 |

transport |

airplane |

35 |

miscellaneous |

sea |

| 5 |

school |

flag |

36 |

fruits |

melon |

| 6 |

transport |

bicycle |

37 |

kitchen |

table |

| 7 |

greetings |

Good afternoon! |

38 |

verbs |

to swim |

| 8 |

greetings |

Good morning! |

39 |

colors |

dark |

| 9 |

cities |

capital |

40 |

family |

godfather* |

| 10 |

house†

|

house |

41 |

animals |

bird |

| 11 |

miscellaneous |

sky |

42 |

clothing |

pants |

| 12 |

questions |

How? |

43 |

animals |

penguin |

| 13 |

questions |

How are you? |

44 |

school |

blackboard |

| 14 |

school |

classmate |

45 |

food |

pizza |

| 15 |

house |

curtains†

|

46 |

room |

iron |

| 16 |

days of the week |

day |

47 |

miscellaneous |

please |

| 17 |

house |

broom†

|

48 |

questions |

Why? |

| 18 |

living room |

light bulb |

49 |

time |

present |

| 19 |

animals |

rooster |

50 |

professions |

president |

| 20 |

adjectives |

fat |

51 |

bathroom |

shower |

| 21 |

adjectives |

big |

52 |

living room |

living room |

| 22 |

verbs |

to like |

53 |

food |

sauce |

| 23 |

family |

daughter |

54 |

cities |

Saltillo |

| 24 |

family |

son* |

55 |

clothing |

shorts |

| 25 |

greetings |

hello* |

56 |

verbs |

to dream |

| 26 |

time |

hour |

57 |

transport |

taxi |

| 27 |

time |

today |

58 |

bathroom |

towel |

| 28 |

animals |

giraffe |

59 |

animals |

deer* |

| 29 |

verbs |

to play |

60 |

house |

window†

|

| 30 |

drinks |

milk |

61 |

clothing |

dress |

| 31 |

vegetables |

lettuce |

62 |

person |

widower |

Table 7.

Signs for the third subset.

Table 7.

Signs for the third subset.

| No. |

Semantic field |

Sign |

| 1 |

house |

garbage |

| 2 |

house |

trash can |

| 3 |

house |

house* |

| 4 |

house |

curtains* |

| 5 |

house |

electricity |

| 6 |

house |

stairs |

| 7 |

house |

broom* |

| 8 |

house |

internet |

| 9 |

house |

garden |

| 10 |

house |

keys |

| 11 |

house |

wall |

| 12 |

house |

floor |

| 13 |

house |

door |

| 14 |

house |

roof |

| 15 |

house |

mop |

| 16 |

house |

window* |

Table 8.

Custom dataset.

| Feature |

Description |

| Signs* |

70 W, 4 P |

| Signers |

17 |

| Samples |

73 signs with 17 samples, 1 sign with 16 samples |

| Sign features |

HC, AM, NHG |

| Sign signal |

Visual |

| Signal properties |

900×720 @ 90 fps |

| File format |

MKV videos |

| Samples for training |

10 samples |

| Samples for validation |

2 samples |

| Samples for testing |

5 samples |

Table 9.

Software and Hardware Specifications.

Table 9.

Software and Hardware Specifications.

| Software/Hardware |

Version/Model |

| Operating System |

Ubuntu 22.04.2 |

| Graphics card |

NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti |

| CUDA |

12.4 |

| Python |

3.11.8 |

| PyTorch |

2.2.2 |

| Ultralytics YOLO |

8.1.47 |

Table 10.

Training parameters and their descriptions.

Table 10.

Training parameters and their descriptions.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| epochs |

50 |

Number of epochs or training cycles. |

| batch |

16 |

Number of images processed in each iteration. |

| imgsz |

224 |

Size of the images input into the model. |

| patience |

100 |

Number of epochs without improvement before stopping the training. |

| lr0 |

0.01 |

Initial learning rate. |

| pretrained |

True |

Indicates that the model uses pre-trained weights (ImageNet). |

| single_cls |

False |

If set to True, the model classifies into a single class. |

| dropout |

0.0 |

Dropout rate. This is a regularization technique used to reduce overfitting in artificial neural networks. |

Table 11.

Image augmentation parameters and their descriptions.

Table 11.

Image augmentation parameters and their descriptions.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| hsv_h |

0.015 |

Hue of the image in the HSV color space. |

| hsv_s |

0.7 |

Saturation of the image in the HSV color space. |

| hsv_v |

0.4 |

Brightness of the image in the HSV color space. |

| degrees |

0.0 |

Random rotation applied to the images. |

| translate |

0.1 |

Random translation of the images. |

| scale |

0.5 |

Random scaling factor applied to the images. |

| shear |

0.0 |

Random shear angle applied to the images. |

| perspective |

0.0 |

Perspective transformation applied to the images. |

| flipud |

0.0 |

Probability of flipping the image vertically. |

| fliplr |

0.5 |

Probability of flipping the image horizontally. |

| bgr |

0.0 |

BGR to RGB color space correction factor. |

| mosaic |

1.0 |

Probability of using the mosaic technique to combine images. |

| mixup |

0.0 |

Probability of mixing two images. |

| copy_paste |

0.0 |

Technique of copying and pasting objects between images. |

| auto_augment |

randaugment |

Type of data augmentation used. |

| erasing |

0.4 |

Probability of erasing parts of the image to simulate occlusions. |

| crop_fraction |

1.0 |

Proportion of the image to be cropped. A value of 1.0 indicates no cropping. |

Table 12.

Comparative table with the values of Top-1 Accuracy.

Table 12.

Comparative table with the values of Top-1 Accuracy.

| Dataset |

No. clases |

Description |

With elbows |

Without elbows |

| 1 |

5 |

More distinguishable |

0.8799 |

0.9599 |

| 2 |

62 |

More or less distinguishable |

0.6537 |

0.6375 |

| 3 |

16 |

group house

|

0.7125 |

0.6875 |