1. Introduction

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and equitable opportunity to be as healthy as possible [

1]. In order to achieve health equity, everyone must have access to the conditions and resources that positively affect health, which are often referred to as the social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH refer to the living and working environments and their impact on health that are determined by people’s social status and resources rather than by disease itself[

2], including quality of education, public safety, access to health care, social support, residential isolation, etc. [

3]. These SDOH often interact with each other to create complex systems that influence long-term health outcomes [

4,

5].

Evidence from Web of science (WOS) suggests systematic disparities in adolescent health (health-promoting/undermining behaviors and health outcomes) [

6,

7]. Such inequitable health disparities are caused by social determinants, particularly the stratification of health status by social status, also known as the “Social Gradient in Health” [

8]. Even health disparities caused by lifestyles, such as smoking and drinking, are due to the social environment that disable adolescents from being in control of their lives, which ultimately force individuals to make choices that are not conducive to health [

9].

Adolescence, on the other hand, is recognized as a period that “provides important opportunities for prevention and intervention to support the healthy growth and development of young people, promote future health and well-being in adulthood, and thereby support the health of the next generation” [

10]. This is a period of significant physical, cognitive, emotional, and social change [

11,

12]. Adolescents are increasingly aware of social processes, and are highly susceptible to influences in the social environment that can lead to positive or negative health outcomes and ultimately to inequalities as adolescents age and transit into adulthood [

13,

14]. Therefore, identifying the social determinants of health behaviors (risks) and health outcomes in adolescents is is essential to advance our understanding of developmental health trajectories and developing targeted interventions. As emphasized by Viner et al., social factors that influence adolescent health include the individual, family, community, and national levels [

12].

Therefore, in order to understand how different dimensions of SDOH affect adolescents’ health, this scoping review combed through the existing evidence on the impact of SDOH on international adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes. First, based on the theoretical framework of the rainbow model, a framework for analyzing SDOH was constructed, and the WOS database was used to search and organize the literature by SDOH domains of health (inequality), socioeconomic status (SES), health care access and quality, and social and community context. Second, the CiteSpace software was used to analyze the relevant literature in terms of publication volume, major journal sources, study countries and keywords. Finally, existing evidence on the role of SDOH on adolescent health across a wide range of health indicators (health behaviors versus health outcomes) was assessed and summarized.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Using the WOS Core Collection as the data source, the search strategy was ((TS=((adolescent OR youth)* health inequity OR (adolescent OR youth)* health equity OR (adolescent OR youth)* health inequality OR (adolescent or youth)* health equality))) AND TS=(social determinants). Since 2000, there has been a steep increase in the amount of published articles related to adolescent health inequality and its social determinants, so the time span was set from 2000-01-01 to 2024-12-31, the type of literature was “article” or “review article”, and the language was “English”.

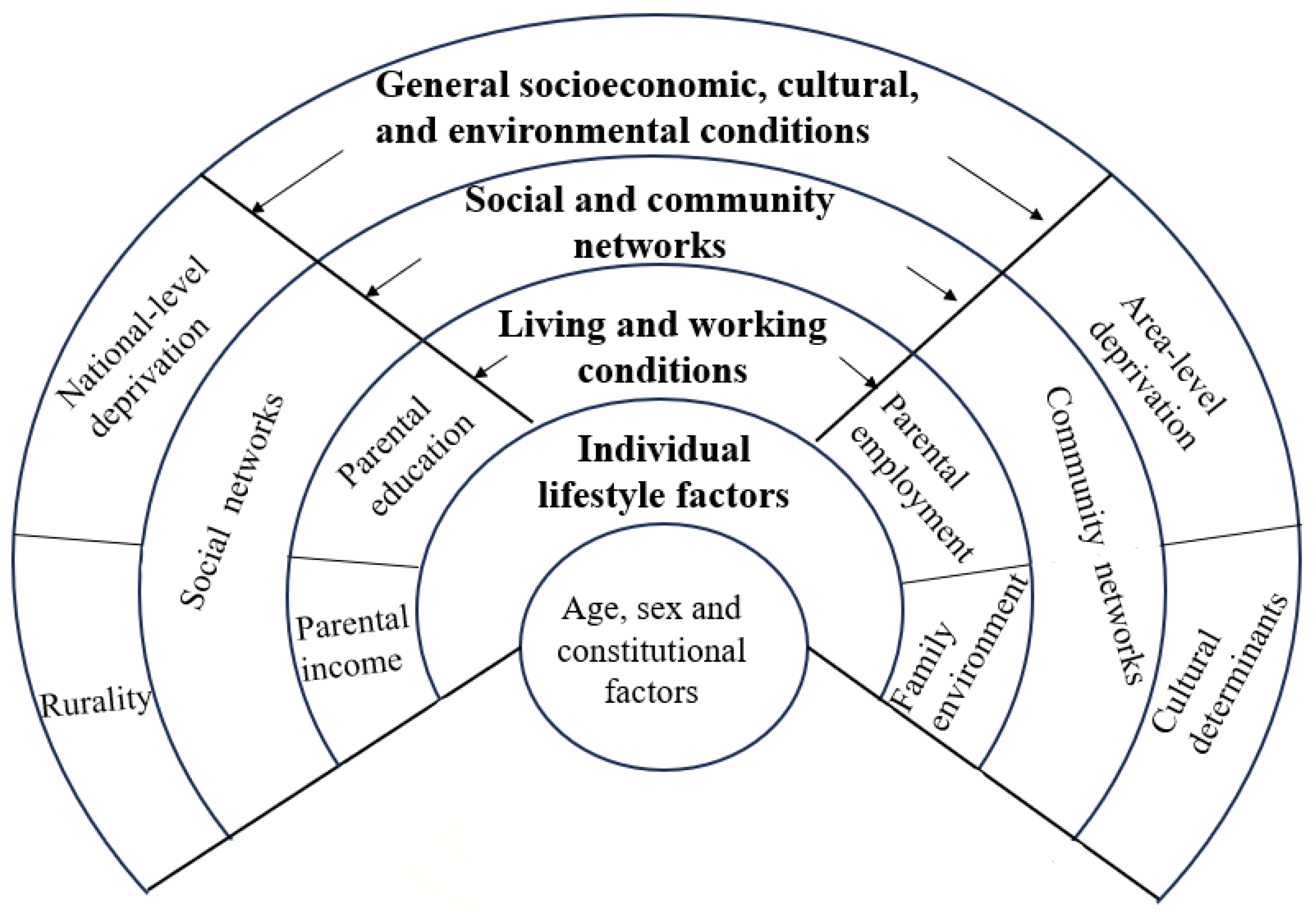

2.2. Theoretical Framework

In this study, a framework for modelling SDOH was constructed based on the Dahlgren and Whitehead model (often referred to as the “rainbow model”)[

15]. This model assumes that different SDOH can function simultaneously and there are often complex interactions between SDOH at the individual level, in the local context, and in society as a whole [

15]. Considering the specifics of the finalized 147 papers, SDOH factors were classified into five groups: (1) general socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions; (2) living and working conditions; (3) social networks; (4) community networks; and (5) individual lifestyle factors (

Figure 1).

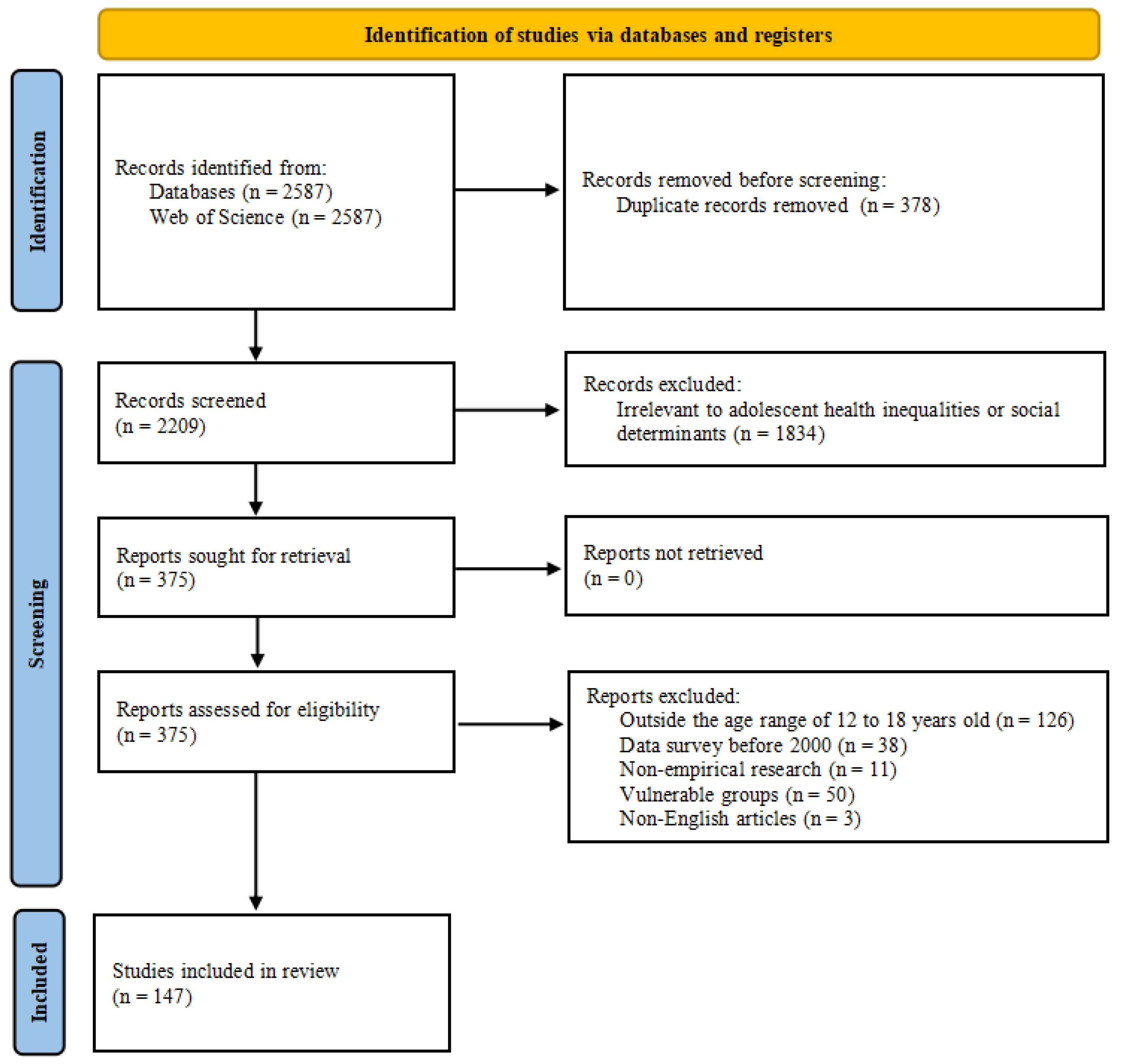

2.3. The Research Process

First, the retrieved literature was independently screened by two trained researchers and finalized by a third researcher, resulting in the inclusion of 147 papers. Selection criteria included: (1) research topic was related to adolescent health inequality and its social determinants; (2) were empirical studies; (3) were published in English; (4) were studies on adolescents (12-18 years old) in general; and (5) were published between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2024. Exclusion criteria included: (1) the research topic was not related to adolescent health inequalities or its determinants; (2) were non-empirical studies; (3) were not written in English; (4) the study population was a special group (e.g., people with AIDS, sexual minorities, or early pregnant adolescents, etc.); (5) age was younger than 12 or older than 18; and (6) the data were surveyed prior to the year 2000.

Second, two researchers independently combed through the identified 147 articles on international adolescent health inequities and their social determinants using CiteSpace 6.3.1 software, sorting them by the volume of literature releases, release dates, journals, major research countries, as well as detecting research hotspots from the keyword frequency analysis.

Finally, an analytical model of the SDOH for this study was developed based on the rainbow model to explore the social determinants of both health behaviors and health outcomes among adolescents worldwide, and to discuss and analyze the important factors that influence adolescent health.

2.4. Research Variables

The predictors were the SDOH, as shown in

Figure 1. The study outcome, the adolescent health indicators, included both health behaviors and health outcomes. Health behaviors broadly referred to a range of health-promoting (healthy diet, oral health, physical activity, sleep duration, etc.) and health-damaging (alcohol consumption, smoking, marijuana use, and sedentary behavior, etc.) behaviors. Health outcomes included perceived health indicators (health complaints, self-rated health), mental health (depression, anxiety, etc.), malnutrition, injuries, and communicable and non-communicable diseases.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Primary Literature

Of the initial 2209 records, 375 studies were selected for full-text screening, of which 147 studies (articles) were finally selected. No additional records were identified that met the inclusion criteria after checking all the references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 147 studies being included in the analysis (see

Figure 2). All studies were published between 2000 and 2024.

3.2. Quantitative Results of Citespace-Based Literature

3.2.1. Trend Analysis of Literature Releases

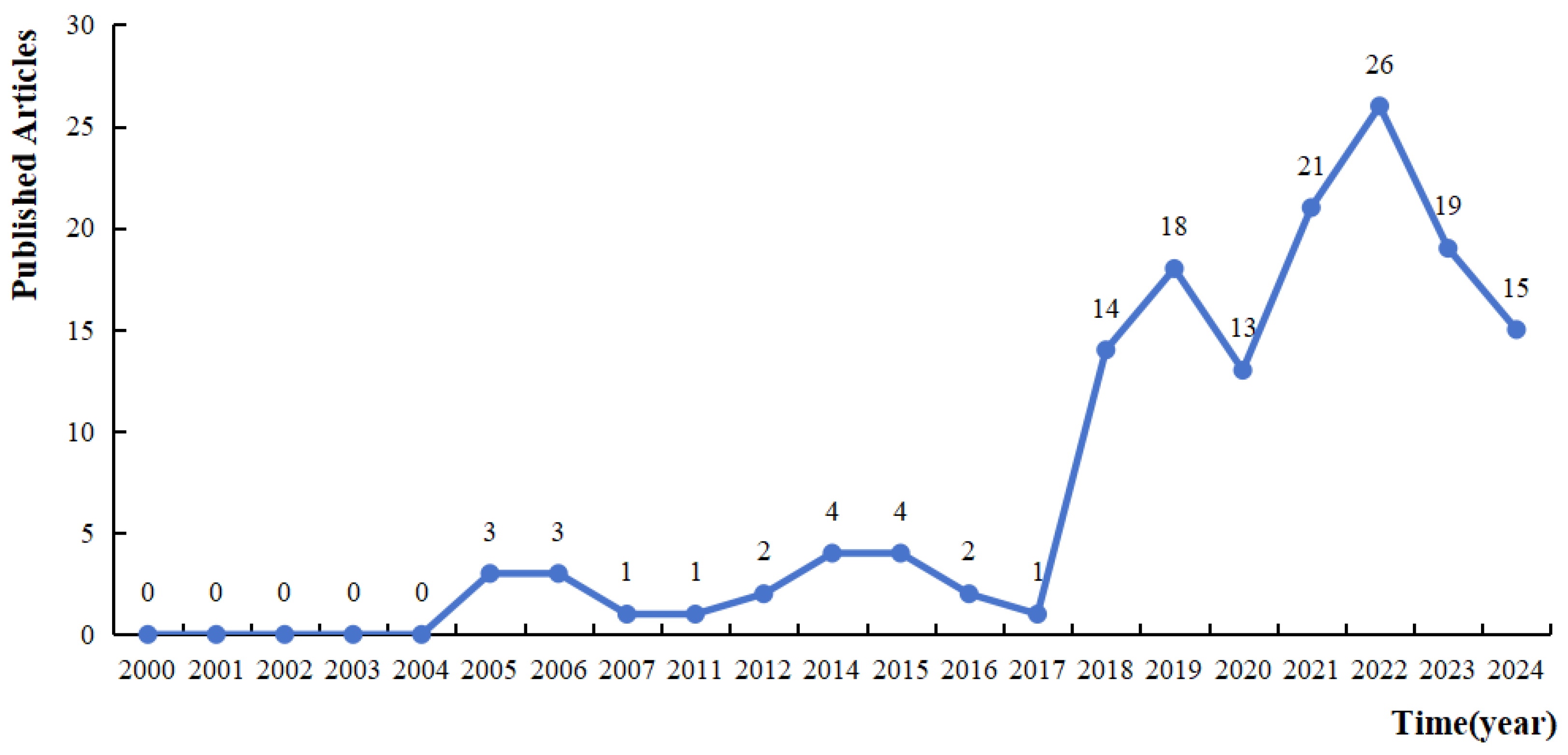

Trends in the number of publications in the field of research on adolescent health inequalities and their social determinants were analyzed through Microsoft Excel 2016 software. The results show that the amount of research literature on adolescent health inequality has shown a steady increasing trend. In particular, the number of literature releases has increased significantly since 2018, indicating that the field is increasingly receiving attention from the academic community.

Figure 3.

Trend analysis of the increase in the number of articles published in the study of social determinants of adolescent health, 2000-2024.

Figure 3.

Trend analysis of the increase in the number of articles published in the study of social determinants of adolescent health, 2000-2024.

3.2.2. Main Journal Sources

The international sample of social determinants of adolescent health was published in more than 90 journals, and the top 10 journals in terms of publications were mainly public health journals, with the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in the first place, followed by BioMed Central Public Health and Public Library of Science One. This is shown in

Table 1.

3.2.3. Main Research Countries

The top 5 countries in the field of adolescent health inequities research in terms of publications over the past 24 years were the United States (n=29), Canada (n=23), the United Kingdom (n=22), Australia (n=14), and Germany (n=13). Most of the research in this area was conducted in developed countries.

Table 2.

Top 10 Countries with the Strongest Citation Bursts.

Table 2.

Top 10 Countries with the Strongest Citation Bursts.

| ordinal number |

periodicals |

No. of documents/article |

Percentage/% |

| 1 |

USA |

29 |

19.73 |

| 2 |

Canada |

23 |

15.65 |

| 3 |

England |

22 |

14.97 |

| 4 |

Australia |

14 |

9.52 |

| 5 |

Germany |

13 |

8.84 |

| 6 |

Brazil |

12 |

8.16 |

| 7 |

Spain |

10 |

6.80 |

| 8 |

Finland |

10 |

6.80 |

| 9 |

Netherlands |

10 |

6.80 |

| 10 |

Sweden |

9 |

6.12 |

3.2.4. Keyword Analysis

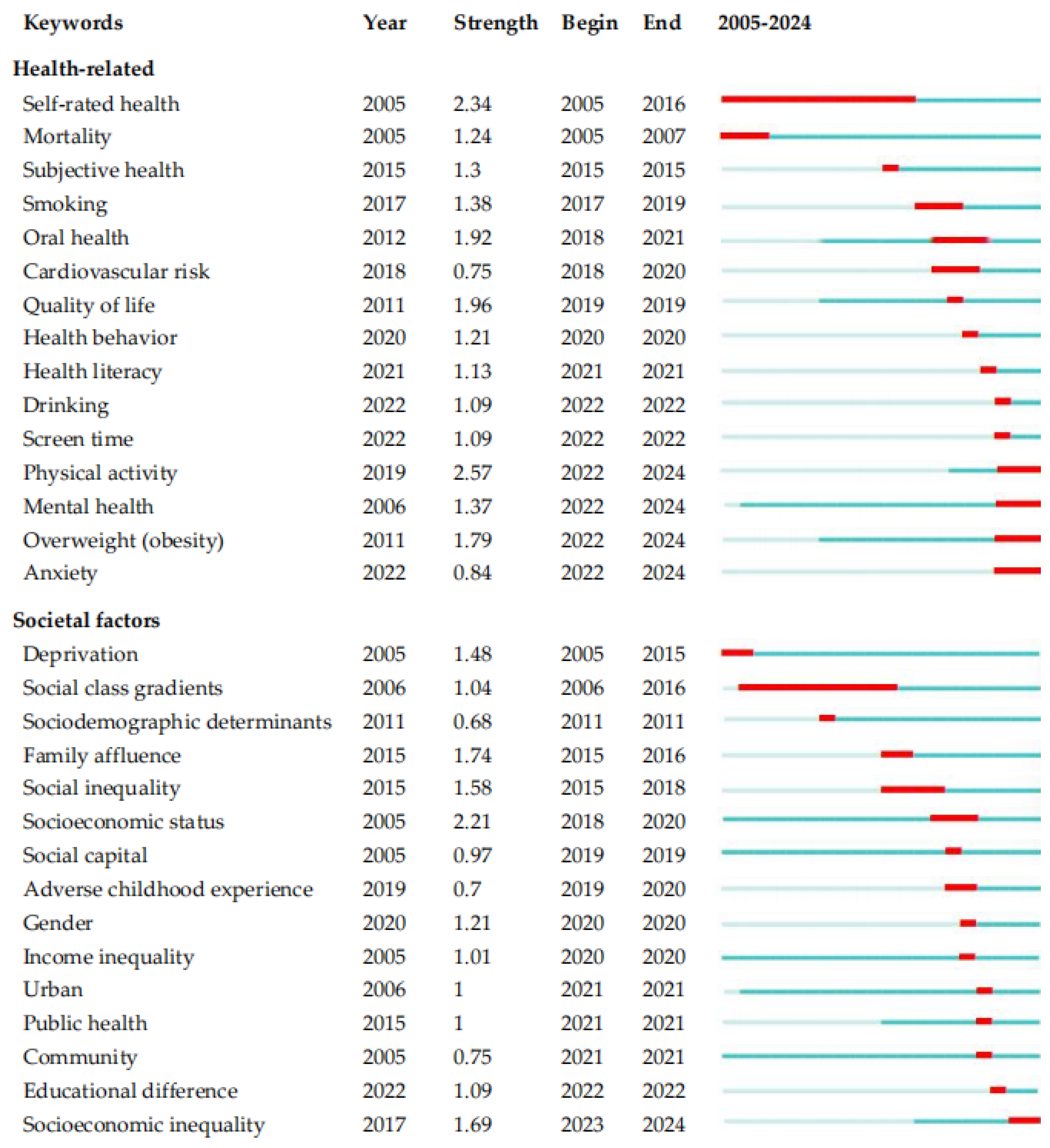

Keywords were obtained from the title, abstract and keyword part of these articles, and those with relatively high frequency can be regarded as the research hotspots in the field to a certain extent. Meanwhile, according to the keyword attributes of the sample literature, the research hotspots of adolescent health inequality and its social determinants were categorized into two major aspects: health-related and societal factors. See

Figure 4.

For health-related keywords, “self-rated health” was the first to become a research hotspot, starting in 2005, and remained a research hotspot for 11 years from 2005-2016. Since then, “oral health”, “quality of life”, and those related to health behaviors (e.g., “smoking”, “drinking”, and “screen time” etc.) had also begun to gain attention. Popularity of topics such as “physical activity”, “mental health”, and “overweight” continued to the present. In terms of strength (i.e., a sudden increase in the frequency of the keyword’s occurrence in a given time period), “physical activity”, “self-rated health”, and “quality of life” ranked as top three, scoring 2.57, 2.34, and 1.96, respectively.

For keywords related to societal factors, “social class gradients” was a hot topic in 2006-2016. “Demographic determinants”, “family affluence”, “social capital”, “adverse childhood experience”, and “educational difference” were also regarded as determinants of adolescent health. In terms of strength, “SES”, “family affluence”, and “social inequality” ranked as top three with 2.21, 1.74 and 1.58 respectively.

Figure 4.

Top 15 Keywords with the Strongest Citation Bursts.

Figure 4.

Top 15 Keywords with the Strongest Citation Bursts.

(The light blue color shows the year in which the keywords did not appear, the dark blue color shows the time that the keywords appeared until now, and the red line exhibits the stage in which the keywords became a hot topic of academic research. “Strength” is calculated algorithmically and indicates the burst strength of a keyword, i.e., a sudden increase in the frequency of the keyword’s occurrence in a given time period.)

3.3. Evidence of Social Determinants of Health Behaviors Affecting Adolescents

The evidence of the SDOH influencing adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes was summarized based on the rainbow model: from the individual level, family level, social and community level, to the general socioeconomic level. Seventy-six of the 147 articles included in the literature were related to adolescent health behaviors, and according to these 76 articles, the social determinants all positively or negatively influenced (either promoted or undermined) health behaviors (see

Table 4). The main adolescent health-promoting behaviors were physical activity, healthy diet, healthy oral habits (i.e., brushing teeth frequently, and eating fewer sweets), sleep status, use of sexual and reproductive health services, use of health care or mental health services, having a good vaccination status, and having a good health literacy and health perceptions [

16,

17]. Behaviors that impair the health of youth include alcohol and intoxication, tobacco use, marijuana use, bullying and violence, and unhealthy screen time habits [

18].

3.3.1. Individual Lifestyle Factors

Individual-level factors include age, gender, level of education (academic achievement), and ethnicity. Age, gender, and number of siblings were some of the factors that influence whether or not an adolescent receives good health care [

19]. Of these, gender was the strongest predictor of health behaviors among adolescents [

20]. Boys had significantly higher smoking rates [

21], breakfast eating rates [

22], and physical activity levels, as well as lower tooth brushing [

23] than girls; and they were more likely to avoid mentioning menstruation-related topics. Educational level was also an important predictor, with adolescents with poor academic performance being more likely to engage in smoking, alcohol consumption, and marijuana use [

24]. Additionally, ethnicity influenced adolescent health behaviors. Racial and ethnic minority adolescents, while being more likely to experience major depression (MDE), were less likely to use mental health (MH) services [

25]; and boys from ethnic minorities smoked cigarettes and used alcohol at higher rates than non-ethnic minorities [

26].

Table 3.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Individual-level.

Table 3.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Individual-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health behavior |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Age |

Mental health service utilization |

|

|

1 |

| Cigarette smoking |

|

|

1 |

| Gender |

Health literacy |

1 |

|

|

| Healthy diet |

2 |

|

|

| Oral health behavior |

1 |

|

|

| Sporting activity |

|

|

2 |

| Sexual and reproductive health awareness |

|

|

2 |

| Health care, mental health service utilization |

2 |

|

|

| Cigarette smoking |

1 |

|

|

| Race/ethnicity |

Healthy diet |

2 |

|

|

| Vaccinations |

1 |

|

|

| Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana use |

1 |

|

|

| Educational level |

Healthy diet |

|

|

3 |

| Oral health behavior |

|

|

2 |

| Sleep condition |

|

|

1 |

| Sporting activity |

|

|

2 |

| Smoking and drinking |

4 |

|

|

| Unhealthy screen time habits |

1 |

|

|

| Psychological asset |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors, physical activity, sleep status |

|

|

2 |

| Smoking and drinking |

1 |

|

|

3.3.2. Living and Working Conditions

Residential and living conditions of adolescents mainly refer to indicators of family SES, including family affluence, parental education, and parental occupation. There was a significant relationship between family SES and various adolescent health behaviors.

Specifically, in terms of family income, adolescents from more affluent families were likely to have increased odds of hazardous drinking [

27], intake of sugar-sweetened beverages [

28], but at the same time, healthier food intake [

29], and better oral health [

24]. In contrast, adolescents from poorer families were most likely to have long screen use time [

30], low breakfast frequency [

31], low vaccination prevalence [

32], and sedentary behaviors [

30].

In terms of parental education level, adolescents with less educated parents had lower vaccination rates [

33], physical activity levels [

29], and higher odds of sugary drink intake [

34]. In addition, parents’ occupation and employment status could negatively affect adolescent health [

35]. For example, full-time parental employment and low companionship were associated with problematic media use in adolescents [

36].

In terms of home environment, adolescents with poorer home environments also had lower utilization of health service interventions [

37], higher risk for passive smoking [

38], and were more likely to develop addictive social media use [

39]. In contrast, a good home environment and direct communication between family members could help adolescents reduce their intake of unhealthy foods [

29] and increase their sports participation [

24].

Table 4.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Family-level.

Table 4.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Family-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health behavior |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Family SES/wealth of the family |

Sporting activity |

|

|

11 |

| Healthy diet |

|

|

11 |

| Oral health behavior |

|

|

3 |

| Vaccinations |

|

|

2 |

| Health care, mental health service utilization |

|

|

2 |

| Sexual and reproductive health service utilization |

|

|

2 |

| Sleep condition |

|

|

1 |

| Health literacy |

|

|

2 |

| Unhealthy screen time habits |

3 |

|

|

| Cigarette smoking |

5 |

|

|

| Drinking and drunkenness |

6 |

|

|

| Parents’ employment status and level of education |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

5 |

| Vaccinations |

|

|

2 |

| Sexual and reproductive health awareness |

|

|

1 |

| Drinking |

2 |

|

|

| Family support |

Oral health behavior |

|

|

1 |

| Unhealthy screen time habits |

4 |

|

|

| Cigarette smoking |

2 |

|

|

3.3.3. Social and Community Networks

Social environment refers primarily to school-level SES. The lower the school SES and the poorer the environment (e.g., public school, poor sanitation, etc.), the greater the odds that adolescents were exposed to unhealthy diets as well as alcohol consumption in school [

40], and the poorer their oral health (e.g., low frequency of tooth brushing [

41,

42]. Schooling is also a strong predictor of adolescents’ use of health facilities to access sexual and reproductive health information and services [

43] and health literacy [

44,

45]. Peers are also an important part of the social environment, and peer support can directly influence the amount of time adolescents spend in physical activity [

46]. In addition, adolescents with lower peer status have lower oral health-related quality of life [

47].

Community SES was correlated with adolescent physical activity facility utilization [

48], injuries [

49], self-rated health [

50], and density of liquor stores [

51]. For example, poorer neighborhoods have a greater number of fast food restaurants, fewer indoor facilities, and adolescents from poorer neighborhoods were more likely to be overweight [

52].

Table 5.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Social-and-Community-level.

Table 5.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: Social-and-Community-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health behavior |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Community or neighborhood social capital |

Sporting activity |

|

|

3 |

| Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

6 |

| Violence |

1 |

|

|

| Smoking and drinking |

5 |

|

|

| School social capital |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

4 |

| Vaccinations |

|

|

1 |

| Health literacy |

|

|

1 |

| Sporting activity |

|

|

1 |

| Smoking and drinking |

1 |

|

|

| Peer social capital |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

2 |

| Sporting activity |

|

|

2 |

| Smoking and drinking |

1 |

|

|

| Unhealthy screen time habits |

1 |

|

|

3.3.4. General Socioeconomic, Cultural, and Environmental Conditions

General socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions include levels of social deprivation at the national (e.g., Gini coefficient, national income levels, etc.), regional level (area of residence, rural vs. urban), and cultural factors. The higher the income inequality at the national level, the more health-damaging behaviors adolescents are likely to engage in, such as smoking and drinking [

53,

54], pathological gaming [

55], problematic social media use [

56], low levels of physical activity [

57], and lower vaccination rates [

58].

At the regional level, the higher the poverty rate, the poorer the oral health status of adolescents in that region, and socioeconomic factors at the regional level were associated with dental visits and frequency of tooth brushing [

59]. Adolescents in rural areas also had lower utilization of sexual and reproductive health services compared to urban areas [

60]. In addition, more girls in rural areas were informed of serious menstrual contraindications [

61], and they were far less likely to use sanitary measures during menstruation than in urban areas [

62]. At the cultural level, there is a positive correlation between cultural capital and healthy food intake. For example, when adolescents engaged in elite cultural practices, healthy food intake increased [

29].

Table 6.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: the-general-socioeconomic-level.

Table 6.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Behaviors: the-general-socioeconomic-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health behavior |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Social income inequality (e.g., Gini coefficient) |

Sporting activity |

1 |

|

|

| Unhealthy screen time habits |

|

|

2 |

| Bullying and violence |

|

|

1 |

| Drinking and drunkenness |

|

|

1 |

| Area of residence |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

5 |

| Sexual and reproductive health service utilization |

1 |

|

|

| Vaccinations |

|

|

1 |

| Drinking and smoking, violent activities |

5 |

|

|

| Social mobility |

Smoking, unhealthy diet |

1 |

|

|

| Gender inequality |

Violence |

|

|

1 |

| National recommendations |

Healthy diet, oral health behaviors |

|

|

1 |

| Covid-19 |

Unhealthy screen time habits, unhealthy diet |

|

|

1 |

| Social class discrimination, socio-economic disadvantage |

Sleep condition |

1 |

|

|

| Social vulnerability index |

Vaccinations |

1 |

|

|

It is important to note that all five groups of SDOH had an impact on the following health behaviors including: physical activity, healthy diet, oral health behaviors, and tobacco and alcohol use, reflecting a hot area of research in the area of inequalities in adolescent health behaviors.

3.4. Social Determinants of Adolescent Health Outcomes

One hundred and five of the 147 articles included in the literature were related to adolescent health outcomes (see

Table 5), and the health outcome indicators covered adolescents’ self-reported health status, health complaints, injuries sustained, chronic mental health problems, depressed mood, overweight/obesity, thinness, and developmental delays, and suicidality [

63].

3.4.1. Individual Lifestyle Factors

Age, loneliness were common correlates of overweight/obesity and suicidal thoughts in adolescents [

64]. Gender was also associated with mental health problems in adolescents, with boys having significantly higher life satisfaction [

65] and probability of perceived good health [

66], as well as lower likelihood of cardio-metabolic dysfunction [

67] and health complaint rates [

68] than girls.

The correlation between individual SES, as measured by academic achievement, and adolescent health outcomes (e.g., overweight, self-rated health status, and number of health complaints) was also very strong [

69]. With poor academic achievement, adolescents were more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms and have suicide attempts [

70]. High early academic achievement was associated with lower youth homicide rates [

71]. Individuals with lower educational attainment or being Black had higher odds of developing chronic noncommunicable diseases across most risk factors [

72].

In terms of individual past experiences, adverse childhood experiences were associated with poorer health [

75], and cumulative socioeconomic disadvantage in adolescence was associated with poor oral health [

76]. Increased experiences of religious discrimination were associated with increased emotional problems and decreased sleep duration [

77]. Significant differences also existed between adolescents of different ethnicity in terms of their cardiovascular health [

78], or other health indicators. For example, South Asians or African descendants had a higher risk of diabetes than White Europeans, respectively [

79]; Filipino, Japanese/Korean, Southeast Asian, and South Asian adolescents were more likely to be obese than Chinese [

80]; White athletes were more likely to report concussions than Black athletes [

81]; Black students were at higher risk for chronic diseases; and young people from the Caribbean, of mixed-race, or with other racial backgrounds had a higher prevalence of mental health problems [

82].

Table 7.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Individual-level.

Table 7.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Individual-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health outcomes |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Age |

Self-assessed health status |

1 |

|

|

| Oral health |

1 |

|

|

| Health |

|

|

1 |

| Sickness |

|

|

1 |

| Suicide rate |

|

|

1 |

| Gender |

Self-assessed health status |

3 |

|

2 |

| Self-reported symptoms of depression |

1 |

|

|

| Life satisfaction |

2 |

|

|

| Oral health |

3 |

|

|

| Sexual |

1 |

|

|

| Suicide rate |

|

|

1 |

| Racist |

Self-assessed health status |

2 |

|

|

| Oral health |

2 |

|

|

| Clinical depression |

|

|

1 |

| Obese |

|

|

1 |

| Sexual |

|

|

1 |

| Sickness |

|

|

3 |

| Sleep health |

2 |

|

|

| Education level |

Self-assessed health status |

|

|

7 |

| Oral health |

|

|

1 |

| Clinical depression |

|

|

1 |

| Sickness |

2 |

|

|

| Homicide mortality rate |

1 |

|

|

| Substance use disorders |

1 |

|

|

| Being bullied |

Life satisfaction, physical and mental health |

1 |

|

|

3.4.2. Living and Working Conditions

Adolescents with lower SES had poorer periodontal health [

83] and were also more likely to be overweight [

68], have physical and mental health problems [

84], have high levels of perceived stress, and have low life satisfaction [

67]. In contrast, adolescents with high SES and family capital were more likely to have high life satisfaction [

85]. The status of specific indicators of family SES is shown below:

With respect to family income, in almost all countries, adolescents in low-income families tended to experience poorer quality of life [

86], report more violent behavior [

87], have poor oral hygiene [

88], and were also more likely to have mental health problems [

89]. Furthermore, low household incomes also contributed to more mental health problems in conjunction with perceived economic well-being disadvantages at the national level [

90,

91].

In terms of parental education level, adolescents from families with higher educational backgrounds had better quality of life in terms of physical health, mental health and oral health [

92], and lower prevalence of asthma [

93] and probability of obesity [

80]. In contrast, adolescents with less educated parents had a higher risk of hospitalization for violence, self-harm, and substance abuse [

94]. In terms of inter-generational educational level, adolescents with downward-intergenerational education had much poorer self-assessed health compared to their peers with consistently higher levels of inter-generational education [

95].

Adolescents from poorer family environments were also likely to have poorer self-rated health and freedom from peer violence [

96], and they also tended to lack family support and communication, and family cohesion. Health inequalities for adolescents from lower family economic backgrounds could also be somewhat mitigated if family cohesion was high [

97].

Table 8.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Family-level.

Table 8.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Family-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health outcomes |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Family SES/wealth of the family |

Physical and mental health complaints |

18 |

|

|

| Self-assessed health status |

|

|

12 |

| Life satisfaction |

|

|

7 |

| Oral health |

|

|

10 |

| Physical injury |

3 |

|

|

| Obese, overweight |

6 |

|

|

| Multiple psychological burdens |

1 |

|

|

| Health |

|

|

1 |

| Sickness |

5 |

|

|

| Mortality rate |

1 |

|

|

| Sleep health |

|

|

1 |

| Parental education level |

Mental health issues (depression, etc.) |

3 |

|

|

| Physical and mental health complaints |

3 |

|

|

| Oral health |

|

|

2 |

| Physical injury |

1 |

|

|

| Obese, overweight |

2 |

|

|

| Illness (asthma) |

1 |

|

|

| Family support |

Depressive symptom |

1 |

|

|

3.4.3. Social and Community Networks

School-level SES greatly influences the quality of oral health [

88]. Poorer school environments had a higher prevalence of periodontal unhealthiness in adolescents [

44]. School type is also an important predictor of mental health problems in adolescents [

22]. If adolescents grew up in a country with an above-average size of the private pre-school sector, they tended to have less socio-economic inequality in terms of multiple psychological burdens [

98]. Inequalities in adolescent health complaints were smaller in countries with more stratified education systems [

99].

Community SES is also associated with inequalities in adolescent health outcomes. Higher community SES was associated with a lower likelihood that adolescents had long-term conditions, being overweight, had fewer weekly health complaints, and better self-rated health [

84].

Table 9.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Social- and community-level.

Table 9.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: Social- and community-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health outcomes |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Community or neighborhood social capital |

Obese, overweight |

2 |

|

|

| Oral health |

|

|

4 |

| Physical injury |

1 |

|

|

| Substance use disorders |

1 |

|

|

| School social capital |

Physical and mental health complaints |

6 |

|

|

| Life satisfaction |

|

|

3 |

| Oral health |

|

|

3 |

| Peer social capital |

Physical and mental health complaints |

7 |

|

|

| Life satisfaction |

|

|

3 |

| Multiple psychological burdens |

|

|

1 |

3.4.4. General Socioeconomic, Cultural, and Environmental Conditions

Country-level economic development and income inequality factors are recognized as key determinants of adolescent health outcomes [

15], with large socioeconomic gradients across different health indicators in adolescents [

13]. For example, the higher the country’s income inequality (Gini coefficient), the higher the prevalence of adolescent obesity [

100], physical and mental health complaints [

98], depression scores [

101], oral problems [

102], chances of bullying victimization [

103], and suicidality[

104]. Notably, scholars have also found that closure (social mobility) during the Covid-19 epidemic was associated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in adolescents [

105]. The level of social deprivation at the district level is mainly measured by the area of residence (upper middle class areas, migrant/resettlement areas and urban slum areas). Adolescents in deprived areas had poorer oral hygiene [

106,

107], as well as higher cardio-metabolic risks [

108], and cancer incidence [

109].

Cultural factors mainly refer to the degree of gender equality and social cohesion. Boys in countries with higher levels of gender inequality had higher levels of fighting and assault, while physical injuries are more common in countries with lower levels of gender inequality [

110]. Adolescents living in more socially cohesive environments had higher levels of physical and mental health and higher levels of self-efficacy [

111].

Table 10.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: the-general-socioeconomic-level.

Table 10.

Analysis of Social Determinants of Inequalities in Health Outcomes: the-general-socioeconomic-level.

| Specific influencing factors |

Health outcomes |

Quantities |

| - |

0 |

+ |

| Socio-economic deprivation |

Perceived health |

2 |

|

|

| Adverse childhood experiences |

|

|

1 |

| Area of residence |

Oral health |

|

|

5 |

| Prevalence of heart disease |

1 |

|

|

| Mental health status |

|

|

1 |

| National income (e.g., GDP) |

Physical and mental health complaints |

1 |

|

|

| Obese, overweight |

1 |

|

|

| Suicide rate |

1 |

|

|

| Prevalence of heart disease |

1 |

|

|

| Internalization of symptoms |

1 |

|

|

| Social income inequality (e.g., Gini coefficient) |

Physical and mental health complaints |

|

|

2 |

| Suicide rate |

|

|

1 |

| Clinical depression |

|

|

3 |

| BMI, overweight, obese |

|

|

3 |

| Nutrition and health status |

1 |

|

|

| Gender inequality |

Physical injury |

|

|

1 |

| Stratification of the national education system |

Physical and mental health complaints |

1 |

|

|

| Religious discrimination |

Sleep health |

1 |

|

|

| Social cohesion |

Physical and mental health and self-efficacy |

|

|

2 |

| Perceived health |

|

|

1 |

| Clinical depression |

1 |

|

|

| Covid-19 |

Overweight, obese |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

This scoping review presents research findings during the past 24 years (2000-2024) that are related to the social determinants of adolescent health and explores research hotspots as well as important determinants of adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes, so as to provide some insights into practice.

4.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Literature

From the trend in the number of published articles, there is an overall gradual increase in the number of releases during the period of 2000-2024, which indicates that adolescents are now facing various health crisis, and how to maintain lifelong health and quality of life has become a critical research topic among scholars worldwide [

112]. In the 21st century, health has been emphasized more than ever before, and at the Millennium Summit of the United Nations (UN) held in September 2000, 189 member states signed the United Nations Millennium Declaration, which fully demonstrates that health is a comprehensive goal that can only be achieved by improving the social environment [

113].

In terms of major journal sources, in the first place is the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health and Wellness, which focuses on content related to health promotion and disease prevention, and is dedicated to bringing together the scientific community from a variety of disciplines to advance health promotion, well-being, and quality of life. The Biomedical Center for Public Health is a close second, which focuses on interdisciplinary research in disease epidemiology, social determinants of health, environmental and occupational health, health policy, and public health practice.

In terms of national distribution, the United States accounts for 19.73% of the world’s total research output from 2000-2024, and is committed to the systematic interpretation of the SDOH. This may be attributed to the 4th Healthy Citizens 2020 released by the United States in 2010, which covers more than 1,300 research topics in 42 areas including SDOH and the addition of the Youth Health Initiative[

114], and the further release of Healthy People 2030 in 2020, which raises awareness of the gap between actual health status and optimal health [

115]. The U.S. has captured changes in societal health issues and has led the world in the iterative development of related research.

In terms of the burst intensity of keyword, the hotspots for adolescent health indicators are “physical activity,” “mental health,” and “overweight,”. This may be due to their far-reaching and interrelated effects on adolescents’ health, with mental health problems being exacerbated by physical inactivity and obesity being closely related to sedentary behavior and lack of exercise [

114,

115]. The main research hotspots in SDOH are “SES” and “family affluence”. Numerous studies have shown that the lower the SES, the higher the incidence of health problems [

87,

116]. There is a link between household SES and health behaviors (e.g., diet and physical activity), with lower household SES generally having poorer eating habits [

117,

118]and lower levels of physical activity [

119]. In addition, adolescents with lower family SES perform relatively poorly in areas such as perceptions of well-being, and are prone to a form of “double disadvantage” in their physical and mental health [

120].

4.2. Important Social Determinants of Health Behaviors

SDOH at all levels have an impact on health behaviors, particularly healthy diet, oral health behaviors, and tobacco and alcohol use.

Important social determinants of inequalities in dietary behaviors are mainly SES, family environment, social environment and gender at the national level. First, countries with lower SES may be less endowed with material resources (increased food budgets and access to health-promoting goods and services) [

124] and psychosocial resources (nutritional knowledge, cooking skills, and positive attitudes toward healthy eating) [

125,

126]. Second, healthy eating behaviors are shaped by the family environment, which includes not only the food supply but also the eating behaviors of parents [

127]. Parents from the most disadvantaged families have a low frequency of conversations about healthy food consumption [

128]and a low level of concern for healthy eating. Third, the socio-cultural environment and peers also influence adolescents’ food consumption and eating habits. Focusing on the establishment of healthy eating behavior patterns among adolescents’ friend groups can help to promote healthy lifestyles among young people [

129]. Fourth, the frequency of breakfast is higher in boys than in girls, which may be due to the fact that girls reduce the frequency of breakfast to control their weight, or are influenced by their mothers’ attitudes and behaviors [

130], or by the media’s promotion of a model body [

131].

The most important predictor of oral health behavior is family SES. Adolescents’ frequency of tooth brushing is influenced by family SES, such as the level of parental education; well-educated parents are more concerned about their children’s oral health [

132]. In general, a higher level of education leads to more opportunities to develop healthier habits, use health services, and benefit from health promotion activities [

133].

Gender and cultural environment are the main factors influencing adolescents’ smoking and drinking. Smoking prevalence is higher among boys than girls, which may be influenced by gender role socialization (i.e., boys and girls are perceived or presented as more masculine or feminine because of their biological sex) [

131]. In many countries, smoking is considered part of the social construction of masculinity.

4.3. Important Social Determinants of Health Outcomes

Indicators of adolescent health outcomes (including obesity, mental health problems, and suicidal behavior) are more highly correlated with family SES than other levels of social determinants. Adolescents with lower family SES have higher rates of personal psychological burden and multiple mental disorders and poorer quality of life compared to their peers [

132]. Because of unequal or lower family income, it is difficult for adolescents to access good housing, school, and health care resources, which in turn reduces adolescents’ quality of life and well-being. Services that currently exist to provide assistance to low-income families (e.g., TANF, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, SNAP, and school lunches) all require very low incomes to qualify. Many low-income families either do not qualify for assistance or receive only limited assistance [

89].

An unfavorable home economic environment can also lead to an increased risk of suicidal and self-injurious behaviors among adolescents. First, adolescents in unfavorable situations in the home may be vulnerable to many stressors and more prone to mental health problems [

133]. Secondly, low SES may mean poor family functioning, mental and physical disorders due to unemployment, divorce or parental separation [

134], which in turn affects parenting. The third may be due to the adolescent’s self-rated lower family class status, which may lead to decreased self-esteem, loneliness, and depressive symptoms, including adolescent suicidal thoughts and self-harming behaviors [

135]. In contrast, the more family health assets an adolescent has, the lower the risk of poor health indicators [

136].

It is worth noting that SES disparities in adolescent health have deepened and that family SES alone (a single dimension) does not protect adolescents from health-risky behaviors or poor self-reported health [140]. Instead, having multidimensional health assets (including state, community, and school levels) can protect adolescents from risky behaviors and poor health status and promote good health outcomes [141].

4.4. Recommendations

The social determinants of adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes are complex and diverse. Based on summarizing relevant international research, this study proposes the following recommendations:

Deepening interdisciplinary research. Given that adolescent health is influenced by multidimensional SDOH, future research should further strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration and encourage longitudinal studies and large-scale survey projects to better understand changes in adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes over time and their dynamic relationship with the social environment.

Consider the impact of emerging social and environmental factors. Explore the impact of emerging social phenomena (e.g., social media use, digital environments, climate change, etc.) on adolescent health behaviors and health outcomes, and how these factors interact with traditional social determinants. Examine the specific pathways by which cultural and social factors, such as gender inequality and social cohesion, influence adolescent health.

Emphasize integrated interventions. Based on multidimensional social determinants, develop systematic and comprehensive intervention strategies covering the individual, family, school, community and national levels. For example, reduce adolescent health inequities by improving family SES, optimizing school environments, and strengthening community support; and conduct systematic evaluations of existing policies and interventions to analyze their effectiveness and limitations in reducing adolescent health inequities, so as to explore how to design and implement more targeted and comprehensive interventions. At the same time, there is a need to advocate for governments to develop and implement policies that are conducive to health equity, such as reducing socio-economic inequalities, improving public health services and enhancing equity in education.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

This scoping review has significant value in dissecting adolescent health inequalities and their social determinants, but some limitations remain. First, in terms of data sources, only English literature included in the Web of Science core collection was selected, which may omit relevant and important studies in other databases or written in other languages. Subsequent studies shall consider incorporating databases such as PubMed and Scopus into the scope of the study. Second, focusing on the literature since 2000, this review summarizes the SDOH inequalities among adolescents, but it lacks a more in-depth exploration of the mechanisms of the deeper interactions among the social determinants. Third, country-specific differences have been ignored, and discussing the situation in developed and developing countries together may obscure some key issues. There are differences in the level of development, social structure, allocation of health resources and cultural background of different countries, all of which have an impact on adolescent health inequalities. More studies are needed to explore the differences between developed and developing countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W., X.J.Z. and Z.Z.H.; searching & screening, X.J.Z. and Z.Z.H.; analysis, X.J.Z.; writing-original draft, Y.W., X.J.Z., Z.Z.H., and S.Y.W.; writing-review and editing, Y.W., X.J.Z., Z.Z.H., and S.Y.W.; visualization, X.J.Z.; supervision, Y.W. & S.Y.W.; project administration, Y.W.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Braveman, P. What Is Health Equity: And How Does a Life-Course Approach Take Us Further toward It? Matern Child Health J 2014, 18, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44489 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Washington, DC US Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ahnquist, J.; Wamala, S.P.; Lindstrom, M. Social Determinants of Health--a Question of Social or Economic Capital? Interaction Effects of Socioeconomic Factors on Health Outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2012, 74, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasinghe, S. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities: Towards a Theoretical Perspective Using Systems Science. Int J Equity Health 2015, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M. The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health. Int J Health Serv 1992, 22, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newacheck, P.W.; Hung, Y.Y.; Park, M.J.; Brindis, C.D.; Irwin, C.E. Disparities in Adolescent Health and Health Care: Does Socioeconomic Status Matter? Health Serv Res 2003, 38, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. Lancet 2015, 386, 2442–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.C.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Samdal, O.; Currie, D.B. Enhancing Understanding of Adolescent Health and Well-Being: The Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. J Adolesc Health 2020, 66, S3–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Adolescence, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0070575123. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, A. Adolescent Neurological Development and Implications for Health and Well-Being. Healthcare (Basel) 2017, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Mills, K.L. Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing? Annu Rev Psychol 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the Social Determinants of Health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M.; Dahlgren, G. What Can Be Done about Inequalities in Health? The Lancet 1991, 338, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, J.S.; Doshmangir, L.; Khoshmaram, N.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Abdolahi, H.M.; Khabiri, R. Key Factors Affecting Health Promoting Behaviors among Adolescents: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv Res 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Applying Lessons of Optimal Adolescent Health to Improve Behavioral Outcomes for Youth. Promoting Positive Adolescent Health Behaviors and Outcomes: Thriving in the 21st Century; Kahn, N.F., Graham, R., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2019; ISBN 978-0-309-49677-3. [Google Scholar]

- Runton, N.G.; Hudak, R.P. The Influence of School-Based Health Centers on Adolescents’ Youth Risk Behaviors. J Pediatr Health Care 2016, 30, e1-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, S.; Saade, M.; Abdalla, S.; AlBuhairan, F. Determinants of Adolescents’ Perceptions on Access to Healthcare Services in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Jeeluna National Survey Findings. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e035315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klanšček, H.J.; Ziberna, J.; Korošec, A.; Zurc, J.; Albreht, T. Mental Health Inequalities in Slovenian 15-Year-Old Adolescents Explained by Personal Social Position and Family Socioeconomic Status. Int J Equity Health 2014, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardani, N.; Tarigan, I.; Suparmi, null; Schlotheuber, A. Socio-Economic, Demographic and Geographic Correlates of Cigarette Smoking among Indonesian Adolescents: Results from the 2013 Indonesian Basic Health Research (RISKESDAS) Survey. Glob Health Action 2018, 11, 1467605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquius, L.; Aguilar-Martínez, A.; Bosque-Prous, M.; González-Casals, H.; Bach-Faig, A.; Colillas-Malet, E.; Salvador, G.; Espelt, A. Social Inequalities in Breakfast Consumption among Adolescents in Spain: The DESKcohort Project. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez de Grado, G.; Ehlinger, V.; Godeau, E.; Sentenac, M.; Arnaud, C.; Nabet, C.; Monsarrat, P. Socioeconomic and Behavioral Determinants of Tooth Brushing Frequency: Results from the Representative French 2010 HBSC Cross-Sectional Study. J Public Health Dent 2018, 78, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, J.M.; Paakkari, L.; Rimpelä, A.H.; Kulmala, M.; Richter, M.; Kuipers, M.A.G.; Kunst, A.E.; Lindfors, P.L. The Role of Health Literacy in the Association between Academic Performance and Substance Use. Eur J Public Health 2022, 32, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; DuPont-Reyes, M.J.; Hossain, M.M.; Chen, L.-S.; Lueck, J.; Ma, P. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Major Depressive Episode, Severe Role Impairment, and Mental Health Service Utilization in U.S. Adolescents. J Affect Disord 2022, 306, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumskas, L.; Zaborskis, A.; Aasvee, K.; Gobina, I.; Pudule, I. Health-Behaviour Inequalities among Russian and Ethnic Majority School-Aged Children in the Baltic Countries. Scand J Public Health 2012, 40, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradors-Rial, N.; Ariza, C.; Rajmil, L.; Muntaner, C. Socioeconomic Position and Occupational Social Class and Their Association with Risky Alcohol Consumption among Adolescents. Int J Public Health 2018, 63, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouche, M.; Lebacq, T.; Pedroni, C.; Holmberg, E.; Bellanger, A.; Desbouys, L.; Castetbon, K. Dietary Disparities among Adolescents According to Individual and School Socioeconomic Status: A Multilevel Analysis. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2022, 73, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, B.; Abel, T.; Moor, I.; Elgar, F.J.; Lievens, J.; Sioen, I.; Braeckman, L.; Deforche, B. Social Inequality in Adolescents’ Healthy Food Intake: The Interplay between Economic, Social and Cultural Capital. Eur J Public Health 2017, 27, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; Brown, W.J.; Ekelund, U.; Brage, S.; Gonçalves, H.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Menezes, A.M.; Hallal, P.C. Socioeconomic Position and Sedentary Behavior in Brazilian Adolescents: A Life-Course Approach. Prev Med 2018, 107, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Konlan, K.D. The Sequential Mediating Effects of Dietary Behavior and Perceived Stress on the Relationship between Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Multicultural Adolescent Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, B.; Quach, C.; Dubé, È.; Tuong Nguyen, C.; Zinszer, K. Social Inequalities in COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Uptake for Children and Adolescents in Montreal, Canada. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7140–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffroid, H.; Doglioni, D.O.; Chyderiotis, S.; Sicsic, J.; Barret, A.-S.; Raude, J.; Bruel, S.; Gauchet, A.; Michel, M.; Gagneux-Brunon, A.; et al. Can Physicians and Schools Mitigate Social Inequalities in Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Awareness, Uptake and Vaccination Intention among Adolescents? A Cross-Sectional Study, France, 2021 to 2022. Euro Surveill 2023, 28, 2300166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, T.; Papadopoulou, E.; Lien, N.; Andersen, L.F.; Pinho, M.G.M.; Havdal, H.H.; Andersen, O.K.; Gebremariam, M.K. Mediators of Parental Educational Differences in the Intake of Carbonated Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks among Adolescents, and the Moderating Role of Neighbourhood Income. Nutr J 2023, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, S.; Piko, B.F.; Fitzpatrick, K.M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Mental Well-Being among Hungarian Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Equity Health 2014, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Agostiniani, R.; Barni, S.; Russo, R.; Scarpato, E.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Stefano, A.V.; Caruso, C.; Corsello, G.; et al. The Use of Social Media in Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.; Salam, S.S.; Kabir, E.; Khanam, R. Identifying Social Determinants and Measuring Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Use of Four Different Mental Health Services by Australian Adolescents Aged 13-17 Years: Results from a Nationwide Study. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, D.; Schmied-Tobies, M.; Rucic, E.; Pluym, N.; Scherer, M.; Debiak, M.; Murawski, A.; Kolossa-Gehring, M. Urinary Cotinine and Exposure to Passive Smoke in Children and Adolescents in Germany - Human Biomonitoring Results of the German Environmental Survey 2014-2017 (GerES V). Environ Res 2023, 216, 114320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIsaac, M.A.; King, N.; Steeves, V.; Phillips, S.P.; Vafaei, A.; Michaelson, V.; Davison, C.; Pickett, W. Mechanisms Accounting for Gendered Differences in Mental Health Status among Young Canadians: A Novel Quantitative Analysis. Prev Med 2023, 169, 107451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, J.; Tolvanen, M.; Kankaanpää, R.; Lahti, S. School-Level Changes in Factors Related to Oral Health Inequalities after National Recommendation on Sweet Selling. Scand J Public Health 2019, 47, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, J.; Tolvanen, M.; Kankaanpää, R.; Lahti, S. Social Gradient in Intermediary Determinants of Oral Health at School Level in Finland. Community Dent Health 2018, 35, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, L.M.R.; Vasconcelos, D.N.; Moreira, R. da S.; Freire, M. do C.M. Individual and Contextual Determinants of Malocclusion in 12-Year-Old Schoolchildren in a Brazilian City. Braz Oral Res 2015, 29, S1806-83242015000100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, I.C.; Mbachu, C.O.; Ezenwaka, U.; Okeke, C.; Eze, I.; Arize, I.; Ezumah, N.; Onwujekwe, O. Variations in Utilization of Health Facilities for Information and Services on Sexual and Reproductive Health among Adolescents in South-East, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2021, 24, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, N.; Wackström, N.; Roos, E.; Suominen, S.; Välimaa, R.; Tynjälä, J.; Paakkari, L. Does Health Literacy Explain Regional Health Disparities among Adolescents in Finland? Health Promot Int 2021, 36, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, V.; Gragnano, A.; Gruppo Regionale Hbsc Lombardia, null; Vecchio, L.P. Health Literacy Levels among Italian Students: Monitoring and Promotion at School. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 9943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Hu, P.; Zhou, Y. How Parental Socioeconomic Status Contribute to Children’s Sports Participation in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Community Psychol 2020, 48, 2625–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorst, J.K.; Vettore, M.V.; Brondani, B.; Emmanuelli, B.; Paiva, S.M.; Ardenghi, T.M. Impact of Community and Individual Social Capital during Early Childhood on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life: A 10-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Dent 2022, 126, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Page, P.; Popkin, B.M. Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.; Janssen, I.; Craig, W.M.; Pickett, W. Multilevel Analysis of Associations between Socioeconomic Status and Injury among Canadian Adolescents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005, 59, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C.C.J.; Li, J.; Zubrick, S.R. Socioeconomic Disparities in Physical Health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Western Australia. Ethn Health 2012, 17, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Turrero, I.; Valiente, R.; Molina-de la Fuente, I.; Bilal, U.; Lazo, M.; Sureda, X. Accessibility and Availability of Alcohol Outlets around Schools: An Ecological Study in the City of Madrid, Spain, According to Socioeconomic Area-Level. Environ Res 2022, 204, 112323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, S.R.; Andersen, O.K.; Lien, N.; Gebremariam, M.K. Neighborhood Deprivation, Built Environment, and Overweight in Adolescents in the City of Oslo. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F.J.; Roberts, C.; Parry-Langdon, N.; Boyce, W. Income Inequality and Alcohol Use: A Multilevel Analysis of Drinking and Drunkenness in Adolescents in 34 Countries. Eur J Public Health 2005, 15, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmengler, H.; Peeters, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Kunst, A.E.; Delaruelle, K.; Dierckens, M.; Charrier, L.; Weinberg, D.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Vollebergh, W.A.M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Adolescent Health Behaviours across 32 Different Countries - The Role of Country-Level Social Mobility. Soc Sci Med 2022, 310, 115289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasante, E.; Pivetta, E.; Canale, N.; Vieno, A.; Marino, C.; Lenzi, M.; Benedetti, E.; King, D.L.; Molinaro, S. Problematic Gaming Risk among European Adolescents: A Cross-National Evaluation of Individual and Socio-Economic Factors. Addiction 2022, 117, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, M.; Elgar, F.J.; Marino, C.; Canale, N.; Vieno, A.; Berchialla, P.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Van Den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Lyyra, N. Can an Equal World Reduce Problematic Social Media Use? Evidence from the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Study in 43 Countries. Information, Communication & Society 2023, 26, 2753–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bann, D.; Scholes, S.; Fluharty, M.; Shure, N. Adolescents’ Physical Activity: Cross-National Comparisons of Levels, Distributions and Disparities across 52 Countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2019, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.S.; Siqueira, T.S.; Silva, J.R.S.; Gurgel, R.Q. Spatial Clustering of Low Rates of COVID-19 Vaccination among Children and Adolescents and Their Relationship with Social Determinants of Health in Brazil: A Nationwide Population-Based Ecological Study. Public Health 2023, 214, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunein, N.; Singh, A.; King, T. Associations between Individual-Level and Area-Level Social Disadvantage and Oral Health Behaviours in Australian Adolescents. Aust Dent J 2020, 65, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habte, A.; Dessu, S.; Bogale, B.; Lemma, L. Disparities in Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Utilization among Urban and Rural Adolescents in Southern Ethiopia, 2020: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundi, M.; Subramanyam, M.A. Menstrual Health Communication among Indian Adolescents: A Mixed-Methods Study. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chakrabarty, M.; Singh, S.; Chandra, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Singh, A. Menstrual Hygiene Practices among Adolescent Women in Rural India: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, S.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Blum, R.W. Trends in Adolescent Health: Successes and Challenges From 2010 to the Present. J Adolesc Health 2024, 75, S9–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, C.; Karamanos, A.; Dregan, A.; O’Keeffe, M.; Wolfe, I.; Sandall, J.; Morgan, C.; Cruickshank, J.K.; Gobin, R.; Wilks, R.; et al. Association of Macro-Level Determinants with Adolescent Overweight and Suicidal Ideation with Planning: A Cross-Sectional Study of 21 Latin American and Caribbean Countries. PLoS Med 2020, 17, e1003443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, N.; Azevedo Da Silva, M.; Elgar, F.J. Trends in Gender and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Adolescent Health over 16 Years (2002-2018): Findings from the Canadian Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2022, 42, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte-Salles, T.; Pasarín, M.I.; Borrell, C.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Rajmil, L.; Ferrer, M.; Pellisé, F.; Balagué, F. Social Inequalities in Health among Adolescents in a Large Southern European City. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011, 65, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.D.; Shenassa, E.D. Sex-Specific Associations Between Area-Level Poverty and Cardiometabolic Dysfunction Among US Adolescents. Public Health Rep 2020, 135, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.C.; Willis, M.; Mabelis, J.; Brown, J.; Currie, D.B. Inequalities in Health Complaints: 20-Year Trends among Adolescents in Scotland, 1998-2018. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1095117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivusilta, L.K.; Rimpelä, A.H.; Kautiainen, S.M. Health Inequality in Adolescence. Does Stratification Occur by Familial Social Background, Family Affluence, or Personal Social Position? BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, D.; Chung, U.S. Investigation of the Trend in Adolescent Mental Health and Its Related Social Factors: A Multi-Year Cross-Sectional Study For 13 Years. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.J.C.; Boulos, M.E.; Shi, G.; MacKrell, K.; Nestadt, P.S. Educational Achievement and Youth Homicide Mortality: A City-Wide, Neighborhood-Based Analysis. Inj Epidemiol 2020, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, C.F.; Pereira, C.C.; Cavalcante, A.M.R.Z.; Guimarães, R.A. Magnitude of Risk Factors for Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases in Adolescents and Young Adults in Brazil: A Population-Based Study. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0292612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.R.; Kia-Keating, M.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Barnett, M.L. Co-Occurring Youth Profiles of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Protective Factors: Associations with Health, Resilience, and Racial Disparities. Am J Community Psychol 2020, 65, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, R.S.; Marcenes, W.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Bernabé, E. Cumulative Socio-Economic Disadvantage and Traumatic Dental Injuries during Adolescence. Dent Traumatol 2021, 37, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.Z.; Truong, M.; Alam, O.; Dunn, K.; Nelson, J.; Kavanagh, A.; Paradies, Y.; Priest, N. The Association between Experiences of Religious Discrimination, Social-Emotional and Sleep Outcomes among Youth in Australia. SSM Popul Health 2021, 15, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, S.D.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Ning, H.; Marino, B.S.; Pool, L.R.; Perak, A.M. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Health in US Adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999 to 2014. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e026797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, S.; Elia, C.; Huang, P.; Atherton, C.; Covey, K.; O’Donnell, G.; Cole, E.; Almughamisi, M.; Read, U.M.; Dregan, A.; et al. Global Cities and Cultural Diversity: Challenges and Opportunities for Young People’s Nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 2018, 77, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.K.; Tseng, W. Associations of Asian Ethnicity and Parental Education with Overweight in Asian American Children and Adolescents: An Analysis of 2011-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Matern Child Health J 2019, 23, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.; Bretzin, A.; Beidler, E.; Hibbler, T.; Delfin, D.; Gray, H.; Covassin, T. The Underreporting of Concussion: Differences Between Black and White High School Athletes Likely Stemming from Inequities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021, 8, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, G.; McManus, S.; Bécares, L.; Hatch, S.L.; Das-Munshi, J. Explaining Ethnic Variations in Adolescent Mental Health: A Secondary Analysis of the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2022, 57, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfreddo, C.S.; Moreira, C.H.C.; Celeste, R.K.; Nicolau, B.; Ardenghi, T.M. Pathways of Socioeconomic Inequalities in Gingival Bleeding among Adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2019, 47, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plenty, S.; Mood, C. Money, Peers and Parents: Social and Economic Aspects of Inequality in Youth Wellbeing. J Youth Adolesc 2016, 45, 1294–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae, E.A. The Mediating Role of Social Capital in the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Wellbeing: Evidence from Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.; Vettore, M.V. Oral Clinical Status and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life: Is Socioeconomic Position a Mediator or a Moderator? Int Dent J 2019, 69, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.N.; Marques, E.S.; da Silva, L.S.; Azeredo, C.M. Wealth Inequalities in Different Types of Violence Among Brazilian Adolescents: National Survey of School Health 2015. J Interpers Violence 2021, 36, 10705–10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfreddo, C.S.; Moreira, C.H.C.; Nicolau, B.; Ortiz, F.R.; Ardenghi, T.M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents: A Cohort Study. Qual Life Res 2019, 28, 2491–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.; Ormsby, G.M.; Kabir, E.; Khanam, R. Estimating Income-Related and Area-Based Inequalities in Mental Health among Nationally Representative Adolescents in Australia: The Concentration Index Approach. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0257573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bøe, T.; Petrie, K.J.; Sivertsen, B.; Hysing, M. Interplay of Subjective and Objective Economic Well-Being on the Mental Health of Norwegian Adolescents. SSM Popul Health 2019, 9, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, S.; Kilty, K.M.; Loeffler, D. Family Structure as a Social Determinant of Child Health. Journal of Poverty 2021, 25, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rueden, U.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bisegger, C.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic Determinants of Health Related Quality of Life in Childhood and Adolescence: Results from a European Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006, 60, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinkrah, E.; Najand, B.; Young-Brinn, A. Parental Education and Adolescents’ Asthma: The Role of Ethnicity. Children (Basel) 2023, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, H.; Moustgaard, H.; Kestilä, L.M.; Martikainen, P. Parental Education and Adolescent Health Problems Due to Violence, Self-Harm and Substance Use: What Is the Role of Parental Health Problems? J Epidemiol Community Health 2019, 73, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhauer, J.; Kuntz, B.; Mauz, E.; Lampert, T. Intergenerational Educational Pathways and Self-Rated Health in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Results of the German KiGGS Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chzhen, Y.; Bruckauf, Z.; Toczydlowska, E.; Elgar, F.J.; Moreno-Maldonado, C.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Sigmundová, D.; Gariépy, G. Multidimensional Poverty Among Adolescents in 38 Countries: Evidence from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) 2013/14 Study. Child Ind Res 2018, 11, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae, E.A. Socioeconomic and Demographic Determinants of Familial Social Capital Inequalities: A Cross-Sectional Study of Young People in Sub-Saharan African Context. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, K.; Ottova, V.; Hurrelmann, K.; de Looze, M.; Levin, K.; Molcho, M.; Elgar, F.; Gabhainn, S.N.; van Dijk, J.P.; Richter, M. Macro-Level Determinants of Young People’s Subjective Health and Health Inequalities: A Multilevel Analysis in 27 Welfare States. Maturitas 2015, 80, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, B.; Strandh, M.; Petersen, S.; Johansson, K. Education System Stratification and Health Complaints among School-Aged Children. Soc Sci Med 2019, 220, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.A.J.; Hunter, S.; Patte, K.A.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Pabayo, R. Exploring the Longitudinal Associations between Census Division Income Inequality and BMI Trajectories among Canadian Adolescent: Is Gender an Effect Modifier? SSM Popul Health 2023, 24, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, C.; Patte, K.A.; Veugelers, P.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Pabayo, R. Income Inequality and Depression among Canadian Secondary Students: Are Psychosocial Well-Being and Social Cohesion Mediating Factors? SSM Popul Health 2022, 17, 100994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadi, M.A.M.; Vettore, M.V. Contextual Income Inequality and Adolescents’ Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life: A Multi-Level Analysis. Int Dent J 2019, 69, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabayo, R.; Benny, C.; Veugelers, P.J.; Senthilselvan PhD, A.; Leatherdale, S.T. Income Inequality and Bullying Victimization and Perpetration: Evidence From Adolescents in the COMPASS Study. Health Educ Behav 2022, 49, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaen-Varas, D.; Mari, J.J.; Asevedo, E.; Borschmann, R.; Diniz, E.; Ziebold, C.; Gadelha, A. The Association between Adolescent Suicide Rates and Socioeconomic Indicators in Brazil: A 10-Year Retrospective Ecological Study. Braz J Psychiatry 2019, 41, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhr, A.; Naper, L.R.; Samarawickrema, I.; Vesterbekkmo, R.K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Mental Well-Being of Norwegian Adolescents During the First Wave-Socioeconomic Position and Gender Differences. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 717747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.R.; Tsakos, G.; Parmar, P.; Millett, C.J.; Watt, R.G. Socioeconomic Inequalities and Determinants of Oral Hygiene Status among Urban Indian Adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2016, 44, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.R.; Tsakos, G.; Millett, C.; Arora, M.; Watt, R. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Dental Caries and Their Determinants in Adolescents in New Delhi, India. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.D.; Shenassa, E.; Slopen, N.; Rossen, L. Cardiometabolic Dysfunction Among U.S. Adolescents and Area-Level Poverty: Race/Ethnicity-Specific Associations. J Adolesc Health 2018, 63, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, G.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Cancer Incidence and Access to Health Services among Children and Adolescents in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet 2022, 400, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Looze, M.; Elgar, F.J.; Currie, C.; Kolip, P.; Stevens, G.W.J.M. Gender Inequality and Sex Differences in Physical Fighting, Physical Activity, and Injury Among Adolescents Across 36 Countries. J Adolesc Health 2019, 64, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolazio, D.; Terraneo, M.; Tognetti, M. Social Cohesion, Psycho-Physical Well-Being and Self-Efficacy of School-Aged Children in Lombardy: Results from HBSC Study. Health Soc Care Community 2021, 29, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, K.; Napp, A.-K.; Reiß, F.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Supporting Youths in Global Crises: An Analysis of Risk and Resources Factors for Multiple Health Complaints in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health 2025, 13, 1510355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranabhat, C.L.; Acharya, S.P.; Adhikari, C.; Kim, C.-B. Universal Health Coverage Evolution, Ongoing Trend, and Future Challenge: A Conceptual and Historical Policy Review. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1041459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, H.K.; Piotrowski, J.J.; Kumanyika, S.; Fielding, J.E. Healthy People: A 2020 Vision for the Social Determinants Approach. Health Educ Behav 2011, 38, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, N.D.; Moore, T.S. Healthy People 2030: Roadmap for Public Health for the Next Decade. Am J Pharm Educ 2020, 84, 8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]