1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains one of the leading causes of death among women, despite significant advancements in breast imaging in recent years. In 2020, approximately 2.3 million cases of breast cancer and 685,000 deaths were recorded worldwide [

1].

Given the high incidence of this disease, it is essential to ensure effective diagnostic procedures that allow for early diagnosis and optimal treatment planning. Tumor size is a crucial parameter in both prognosis and surgical treatment.

Today, whenever possible, conservative surgical approaches are increasingly preferred over mastectomy due to their numerous advantages, including better aesthetic outcomes [

2,

3]. Therefore, an accurate diagnostic estimation of breast lesion size is fundamental for guiding patients toward the most appropriate therapeutic approach.

Breast MRI is known to be more accurate than first-line imaging techniques such as MG [

4,

5] and US [

6,

7] in assessing lesion size, particularly in large breasts with a high fibroglandular component and in evaluating lobular carcinomas [

8].

However, breast MRI has several limitations, including limited availability of equipment, resulting in long waiting lists, high costs, lengthy examination times, dependence on the menstrual cycle, and absolute contraindications such as the presence of metallic implants, as well as relative contraindications like claustrophobia [

9].

In recent years, Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) has emerged as an innovative breast imaging technique that involves contrast-enhanced mammography. CEM is based on the acquisition of both a low-energy (LE) and a high-energy (HE) image using a full-field digital mammography system in a dual-energy technique after intravenous administration of contrast medium [

10].

A subsequent spectral subtraction process generates a composite mammographic image, highlighting areas of tumor neovascularization (angiogenesis), similar to MRI [

11].

By leveraging this characteristic, CEM could serve as a valid and reliable alternative for the accurate estimation of breast lesion size, as well as a valuable tool for surgical planning, while avoiding the typical limitations of MRI [

9,

12].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the accuracy of CEM in estimating the dimensions of breast lesions scheduled for surgical intervention, using post-surgical histological examination as the gold standard, and to assess its effectiveness in comparison to first-line imaging methods such as MG and US. Furthermore, the study evaluates the impact of Additional Lesions (AL), which were missed by first-line breast imaging but detected by CEM, on surgical decision-making (mastectomy vs. conservative surgery).

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective, monocentric study was conducted at the Interventional Senology Unit (UOSD) of the P.O. ‘A. Perrino’ Hospital in Brindisi.

From May 2022 to June 2023, 314 patients (mean age: 56 years) underwent first-line diagnostic imaging (US and/or MG) in a clinical or screening setting, leading to a histologically confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer through ultrasound- or stereotactic-guided biopsy (

Table 1). These patients subsequently underwent Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) for preoperative staging.

All patients provided informed consent for the radiological examination and the intravenous administration of iodinated contrast medium.

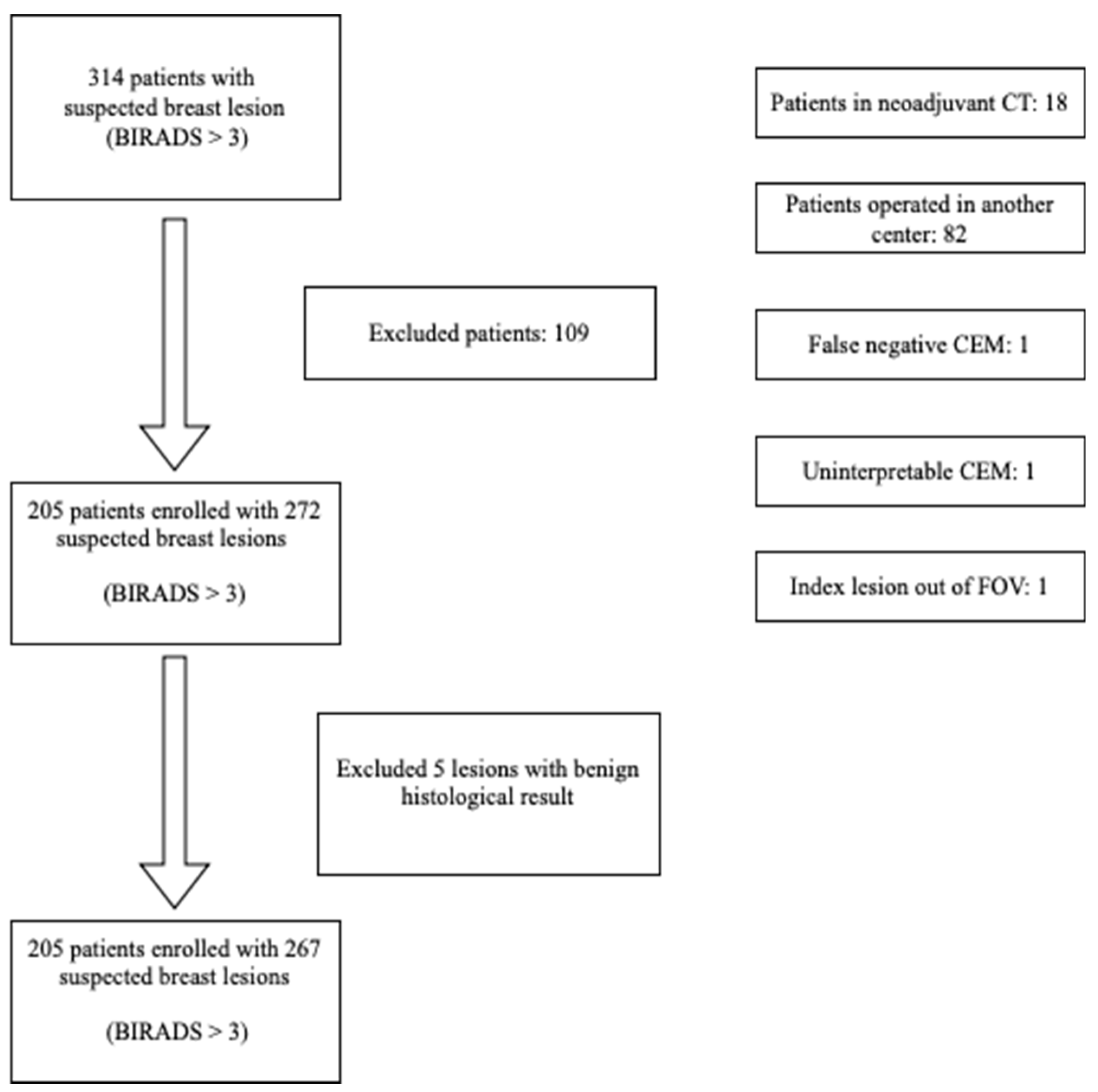

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the patient enrollment process.

Patients undergoing systemic therapy (Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy)

Patients previously operated on in another center

Cases in which the index lesion was outside the field of view of CEM

Cases of false-negative lack of contrast enhancement of the index lesion

Cases where CEM evaluation was not possible due to significant Background Parenchymal Enhancement (BPE)

Thus, 205 patients with 267 suspicious or indeterminate breast lesions (B3, B4, and B5) were included in the study.

Histological evaluation of the surgical specimen was conducted by two pathologists, each with 10 years of experience in breast pathology.

Examination Protocol

In all patients, a 20G peripheral venous access was placed and connected to a dual-syringe injector (contrast medium and saline solution). The contrast medium used was Iohexol 350 mg I/ml (Omnipaque®, GE Healthcare), administered at a dose of 1.5 ml per kg of body weight at an infusion rate of 3 ml/sec.

Each examination began with the injection of contrast medium, immediately followed by the administration of 20 ml of saline solution. Two minutes after the start of the contrast infusion, full-field digital mammography (Senographe Pristina with Seno Bright software, General Electric Healthcare®) was performed.

The image acquisition protocol included:

Compression of the healthy breast in the craniocaudal (CC) view, followed by acquisition of a low-energy (LE, 26–31 keV) and a high-energy (HE, 45–49 keV) image.

Compression of the affected breast in the CC view, with acquisition of LE and HE images.

Compression of the affected breast in the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view, with acquisition of LE and HE images.

Compression of the healthy breast in the MLO view, with acquisition of LE and HE images.

Compression of the affected breast in the mediolateral (ML) view, with acquisition of LE and HE images.

Compression of the healthy breast in the ML view, with acquisition of LE and HE images.

For each patient, a specific recombination algorithm was applied to subtract the LE and HE images, generating a single "subtracted" image for each projection.

No adverse effects were reported during the examinations.

Exposure parameters were adjusted based on breast size and glandular density, following a predefined value table. The images were analyzed using a high-resolution workstation (Barco, Belgium).

To assess the accuracy of CEM, US, and MG in estimating breast lesion size, the final histological specimen (Gold Standard) was used as the reference.

A paired t-test was performed to evaluate differences between lesion size measurements obtained using imaging modalities (US, MG, and CEM) and the Gold Standard.

All analyses were conducted using statistical software.

3. Results

The mean age at biopsy of the 205 patients, with a total of 267 breast lesions, was 56.7 years (SD 11.69). The most common lesion presentations were spiculated opacity (44.6%), nodules detected only on ultrasound (16.9%), microcalcifications (16.1%), and architectural distortions (5.6%). Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) identified 35 additional lesions (13.1%) not detected by ultrasound or mammography (

Table 2).

Lesion classification revealed: • BI-RADS 3: 18 lesions (6.5%) • BI-RADS 4: 2 lesions (0.7%) • BI-RADS 5: 247 lesions (92.5%)

Lesions were distributed between low (51.3%) and high (48.7%) glandular density patterns. Most CEM-detected lesions were in tissues with minimal Background Parenchymal Enhancement (BPE) (55.1%). The most common tumor subtype was Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC, 37%) (

Table 3). Of the 267 lesions, 196 were identified using US, 196 by MG, and all 267 by CEM.

Tumor size measurements: • CEM: 15 mm (10–21 mm) • Histological specimen: 14 mm (10–20 mm) (

Table 4)

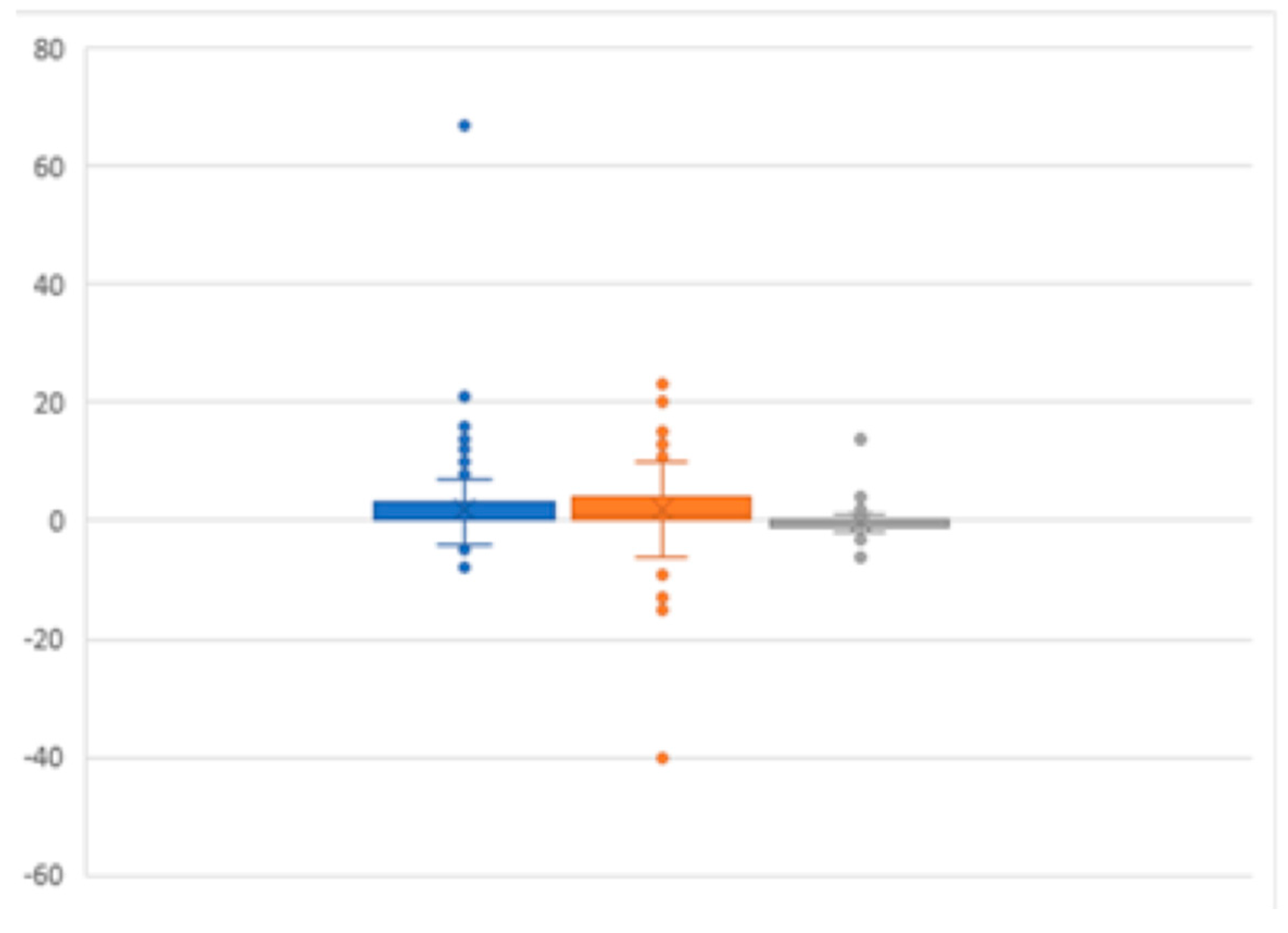

Statistically significant differences were observed between histological size and ultrasound (2.44 mm, p < 0.001) and mammography (2.79 mm, p < 0.001) (

Table 5).

Impact on Surgical Planning: • 93.6% of patients (192/205) had no change in surgical planning after CEM. • 13.7% (28/205) had 35 Additional Lesions (ALs) detected by CEM, with surgical planning remaining unchanged in 7.3% of cases (15 patients). • 6.4% of patients (13/205) experienced upgraded surgical management after CEM detected ALs.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the reliability of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) [

13,

14] compared to traditional imaging modalities (Mammography [MG] and Ultrasound [US]) in assessing breast lesion size, as well as its impact on surgical decision-making [

15]. The findings suggest that first-line imaging techniques often fall short in accurately delineating the extent of breast lesions, especially in patients with dense glandular breast tissue [

16,

17]. Similar challenges with MG and US in dense breast tissue, where tumor visibility is compromised, have been highlighted [

18,

19].

CEM has emerged as a valuable secondary imaging modality that addresses these shortcomings. Unlike MG and US, which can sometimes miss or underestimate the size of lesions, CEM offers superior sensitivity and a more precise assessment of tumor extent, particularly in cases where breast MRI is not an option [

20,

21,

22], such as in patients with pacemakers. Additionally, CEM’s reduced susceptibility to Background Parenchymal Enhancement (BPE) makes it less prone to false positives, a feature that was clearly demonstrated in our study where only six lesions were false positives [

23].

The diagnostic sensitivity of CEM in our study was 97%, which aligns closely with previous findings and slightly exceeds the sensitivity of contrast-enhanced MRI in certain cases. This reinforces the potential for CEM to provide more reliable measurements compared to MG and US (

Figure 2), as it accurately reflects lesion size and offers a stronger correlation with histopathological findings.

These results are consistent with studies that have confirmed CEM’s superiority over first-line imaging in measuring lesion size [

24].

A key objective of this study was to evaluate how the detection of Additional Lesions (ALs) by CEM influences surgical planning

The detection of ALs has significant implications for treatment decisions, particularly in distinguishing between unilateral and bilateral lesions, as well as multifocality and multicentricity. The impact of ALs on surgical planning was substantial, as demonstrated by the 13.7% of patients (28/205) in whom CEM identified lesions that were missed by MG and US. For most patients (86.3%), CEM did not alter surgical plans, confirming that its role is more focused on refining treatment strategies rather than radically changing them.

In the subgroup of patients with ALs (6.4%, 13/205), CEM led to an upgrade in surgical planning, particularly among those with ipsilateral ALs, where breast-conserving surgery plans were revised to mastectomy due to the detection of additional tumor foci. This finding aligns with studies showing that CEM demonstrated higher sensitivity than digital mammography and even when combined with ultrasound [

25,

26].

The implementation of a standardized protocol for preoperative imaging across all patients was a major strength of our study, as it allowed for a consistent approach to surgical decision-making. This approach has facilitated better surgical management, offering more targeted interventions based on CEM findings. CEM, therefore, plays a critical role in preoperative staging, as it provides a more accurate picture of tumor size and lesion extent compared to MG and US.

The results presented here also echo previous studies comparing CEM with MRI. Despite MRI being the gold standard for breast imaging, CEM has demonstrated comparable, if not superior, performance in certain aspects, such as lesion size estimation. CEM’s advantages over MRI, particularly in terms of cost, comfort, and accessibility, were emphasized in prior reports [

27]. Furthermore, CEM is more efficient, with shorter examination times, which translates into reduced waiting lists and better scheduling for surgical procedures, making it an attractive alternative to MRI in certain clinical scenarios [

28].

While our study has shown promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. The lack of a direct comparison between CEM and MRI for lesion size assessment on histopathological specimens is a notable limitation. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size for evaluating the impact of ALs on surgical upgrades warrants further research to confirm these findings in larger cohorts. Future studies should focus on long-term follow-up to assess the impact of CEM on oncological outcomes, as well as exploring the role of CEM-guided biopsy systems, which are still not widely available [

29].

In conclusion, CEM represents a valuable imaging modality for the accurate assessment of breast lesion size and the detection of additional lesions. It plays a crucial role in preoperative staging and can significantly influence surgical decision-making. CEM offers substantial benefits over traditional imaging techniques, and when considered alongside MRI, provides an effective, less invasive, and more accessible option for improving breast cancer management [

30]..

5. Conclusions

CEM demonstrated high sensitivity in loco-regional staging of patients scheduled for surgical intervention, showing strong correlation between lesion size measurements and histological dimensions from the final surgical specimen.

Even in our preliminary experience, CEM appears to be a promising alternative to MRI for surgical planning in breast cancer patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cisternino E. and Galiano A.; methodology, Di Grezia G; software, Cisternino E..; validation, Cuccurullo V, Gatta G. .; formal analysis, Di Grezia G..; investigation, Cisternino E..; resources, Baldari C..; data curation, Galiano A.; writing—original draft preparation, Di Grezia G..; writing—review and editing, Baldari C..; visualization, Cuccurullo V.; supervision, Gatta G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| • |

CEM – Contrast-Enhanced Mammography |

| • |

MG – Mammography |

| • |

US – Breast Ultrasound |

| • |

AL – Additional Lesions |

| • |

BPE – Background Parenchymal Enhancement |

| • |

IDC – Invasive Ductal Carcinoma |

| • |

DCIS – Ductal Carcinoma In Situ |

| • |

MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Sung, H.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, U.; et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahimi, M.S.; et al. Associated factors and survival outcomes for breast conserving surgery versus mastectomy among New Zealand women with early-stage breast cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, N.; et al. Breast Imaging Physics in Mammography (Part I). Diagnostics. 2023, 13, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fico, N.; et al. Breast Imaging Physics in Mammography (Part II). Diagnostics. 2023, 13, 3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatta, G. Automated 3D Ultrasound as an Adjunct to Screening Mammography Programs in Dense Breast: Literature Review and Metanalysis. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Angelo, A.; et al. Supine versus Prone 3D Abus accuracy in Breast Tumor Size evaluation. Tomography. 2022, 8, 1997–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardu, C.; et al. Pre-Menopausal Breast Fat Density Might Predict MACE During 10 Years of Follow-Up: The BRECARD Study. J Am Coll Cardiol Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 14, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast. 2020, 54, 13–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia, L.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography and tumor size assessment: a valuable tool for appropriate surgical management. Radiol Med. 2022, 127, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallenberg, E.; et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: Does mammography provide additional clinical benefits or can some radiation exposure be avoided? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014, 146, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalji, A.; et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography in recalls from the Dutch breast cancer screening program: validation of results in a large multireader, multicase study. Eur Radiol. 2016, 26, 4371–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Mucheru, M.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Digital Mammography in the Surgical Management of Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016, 23, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicki, M.; et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the breast: Advantages and limitations. Eur J Cancer. 2021, 144, 176–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; et al. Preoperative MRI for the evaluation of breast cancer: Predictive value of tumor size and subtype. Oncol Rep. 2010, 24, 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography: State of the Art. Radiographics. 2021, 41, 357–373. [Google Scholar]

- P√∂tsch, N.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography versus Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2022, 305, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, V.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography: A Review. Acta Radiol. 2018, 59, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, K.; et al. Contrast-enhanced mammography in breast cancer screening. Eur J Radiol. 2022, 156, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nijnatten, T.J.A.; Lobbes, M.B.I.; Cozzi, A.; et al. Barriers to Implementation of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography in Clinical Practice: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2023, 221, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbes, M.B.I.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography and Breast MRI: Friends or Foes? Radiology. 2023, 307, e221558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissan, N.; Comstock, C.E.; Sevilimedu, V.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Screening Contrast-Enhanced Mammography for Women with Extremely Dense Breasts at Increased Risk of Breast Cancer. Radiology. 2024, 313, e232580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.T.; Li, H.J.; Li, Y.Z.; et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced mammography for suspicious findings in dense breasts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, P.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; Kapetas, P.; et al. Low-Dose, Contrast-Enhanced Mammography Compared to Contrast-Enhanced Breast MRI: A Feasibility Study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2020, 52, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenberg, E.; Hemmendorff, M.; Cederstr√∂m, B.; Aslund, M.; Danielsson, M. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography with a photon-counting detector: Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography with a photon-counting detector. Med Phys. 2010, 37, 5922–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Lv, Y.; Sun, B.; et al. Diagnostic Value of Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography in Comparison to Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Breast Lesions. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2019, 43, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, M. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography: An Emerging Modality in Breast Imaging. Radiology. 2022, 302, 582–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.M.; Veldhuis, W.B. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography: Moving Ahead with Perfusion Imaging. Radiology. 2022, 305, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neeter, L.M.F.H.; Robbe, M.M.Q.; van Nijnatten, T.J.A.; et al. Comparing the Diagnostic Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography and Breast MRI: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2023, 14, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nijnatten, T.J.A.; Lobbes, M.B.I.; Cozzi, A.; et al. Barriers to Implementation of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography in Clinical Practice: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2023, 221, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).