Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of “Candidates” for the Optimal Index

2.2. Logistic Regression Model

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Existing Indices

3.2. Selection of the Optimal Index

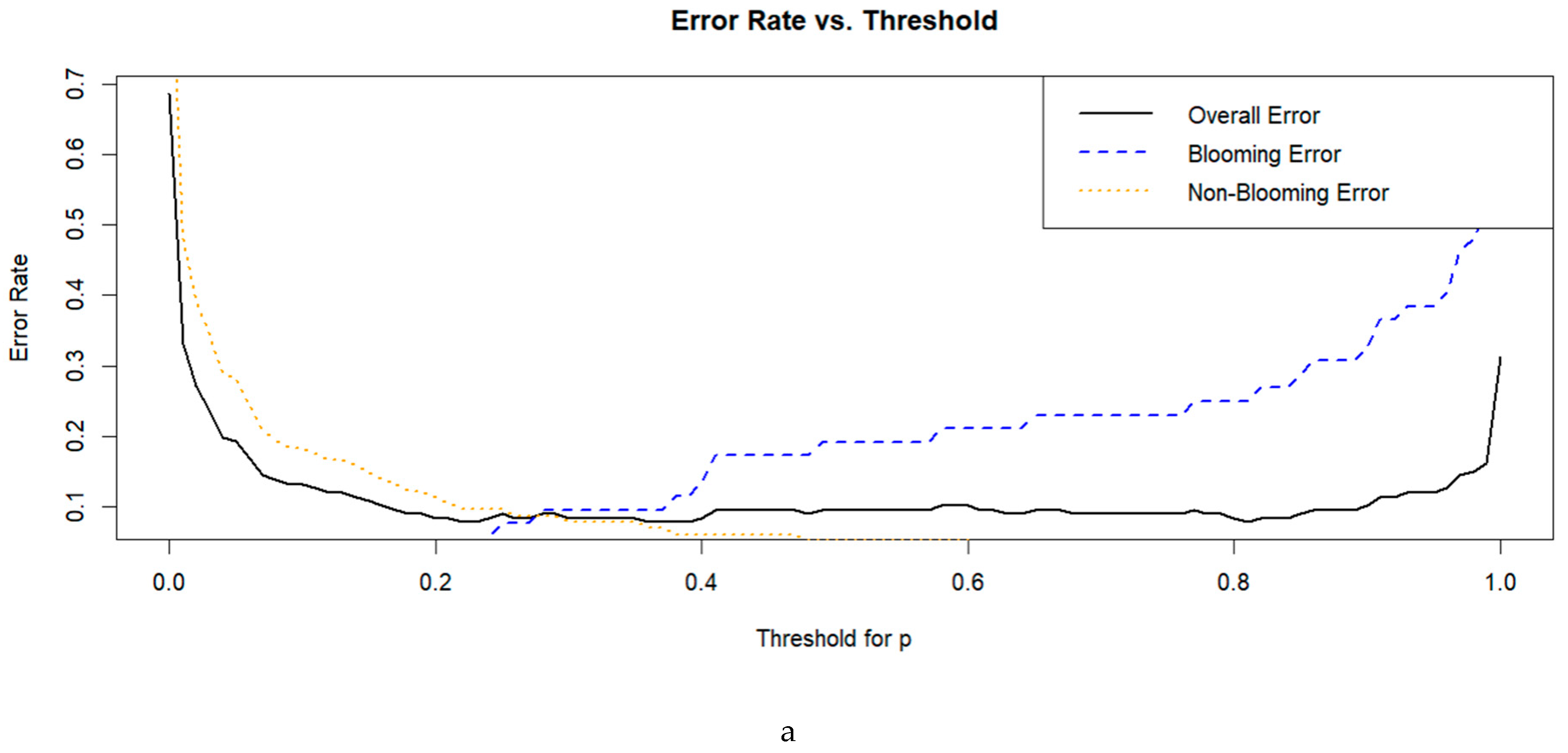

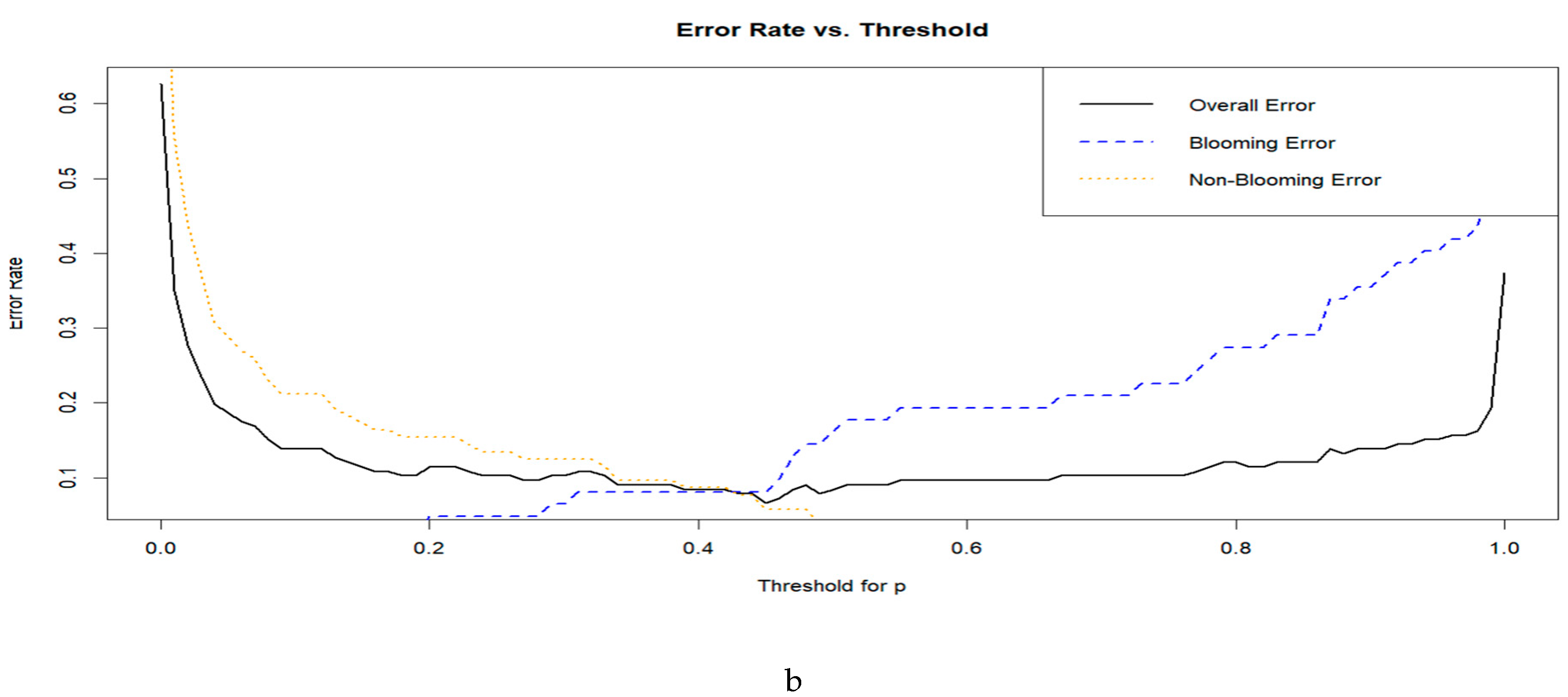

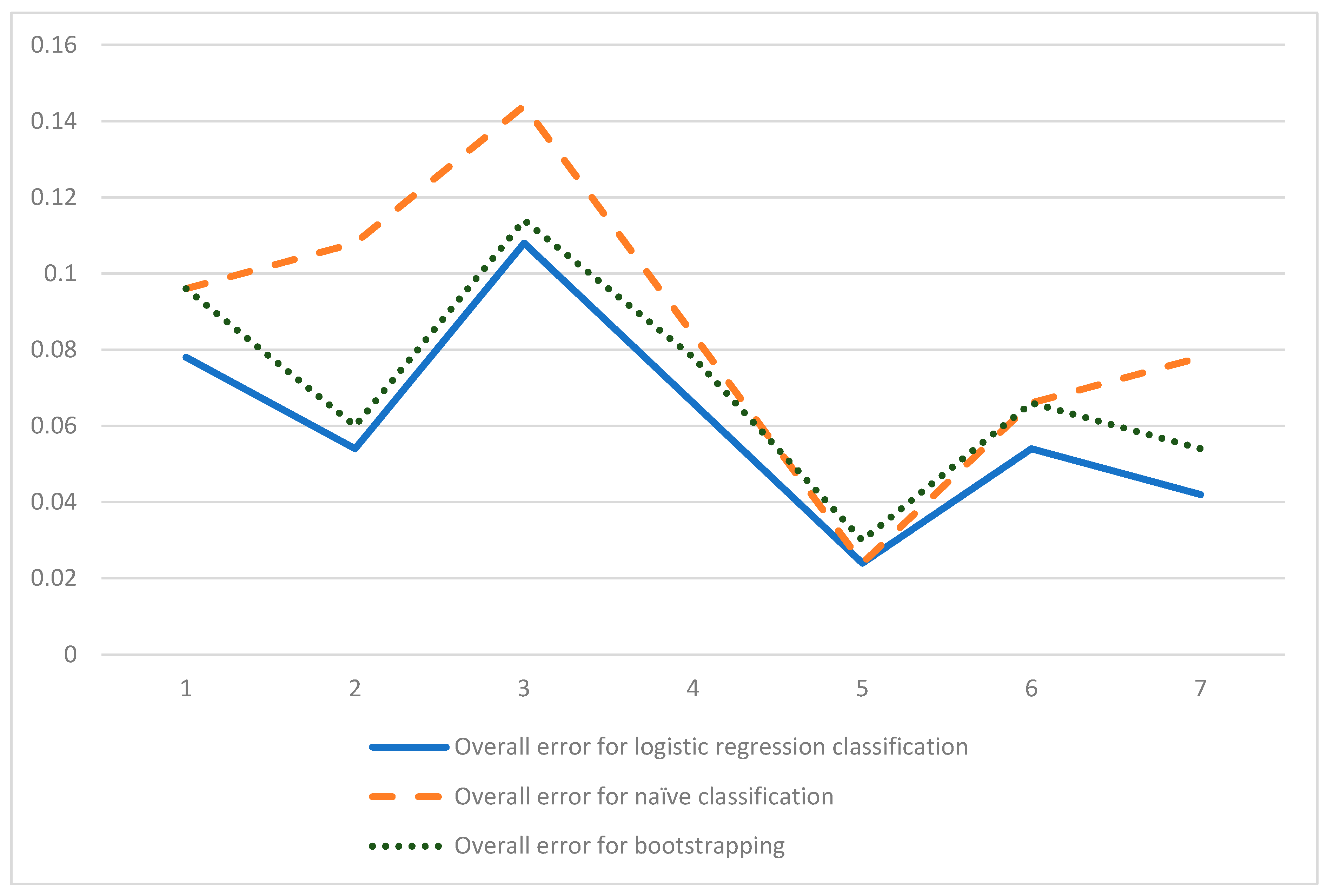

3.3. Model Training and Cross-Validation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Authors Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Alawadi F (2010) Detection of surface algal blooms using the newly developed algorithm surface algal bloom index (SABI) Proc. SPIE 7825, Remote Sensing of the Ocean, Sea Ice, and Large Water Regions, 782506.

- Albornoz, V.M., Araneda, L.C. & Ortega, R. (2022) Planning and scheduling of selective harvest with management zones delineation. Ann Oper Res 316, 873–890.

- Alharbi B (2022) Remote sensing techniques for monitoring algal blooms in the area between Jeddah and Rabigh on the Red Sea Coast. Remote Sensing Applications, Society and Environment 30, 100935.

- Batley GE, Body DN, Cook BG, Dibb L, Fleming PM, Skyring GW, Boon PI, Mitchell DS, Sinclair RL (1990) The ecology of the Tuggerah Lakes System: a review: with special reference to the impact of the Munmorah Power Station. Stage 1: hydrology, aquatic macrophytes, heavy metals, nutrient dynamics. Report prepared for the Electricity Commission of New South Wales, Wyong Shire Council and the State Pollution Control Commission [consultancy report].

- Binding CE, Greenberg TA, Bukata RP (2013) The MERIS Maximum Chlorophyll Index; its merits and limitations for inland water algal bloom monitoring. J Great Lakes Res 39, 100-107.

- Buschmann C, Lenk S, Lichtenthaler HK (2012) Reflectance spectra and images of green leaves with different tissue structure and chlorophyll content. Isr J Plant Sci 60:1-2, 49-64.

- Cao M, Qing S, Jin E, Hao Y, Zhao W (2021) A spectral index for the detection of algal blooms using Sentinel-2 Multispectral Instrument (MSI) imagery: a case study of Hulun Lake, China, Int J Remote Sens 42:12, 4514-4535.

- Cohen R (2002) The effects of runoff on the physiology of Enteromorpha intestinalis: implications for use as a bioindicator of freshwater and nutrient influx to estuarine and coastal areas. UC Office of the President: UC Marine Council.

- Croft H, Chen JM (2017) Leaf Pigment Content. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- Cummins SP, Roberts DE, Zimmerman KD (2004) Effects of the green macroalga Enteromorpha intestinalis on microbenthic and seagrass assemblages in shallow coastal estuary. Mar Ecol Progr Ser Vol.266: 77-87.

- Da Silva e Souza G, Gomes EG, and de Andrade Alves ER. (2022) Two-part fractional regression model with conditional FDH responses: an application to Brazilian agriculture. Ann Oper Res 314, 393–409.

- Deng X, Liu T, Liu CY, Liang SK, Hu YB, Jin YM, Wang XC (2018) “Effects of Ulva prolifera blooms on the carbonate system in the coastal waters of Qingdao”. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 605:73-86.

- Garcia RA, Fearns P, Keesing JK, Liu D (2013) Quantification of floating macroalgae blooms using the scaled algae index. JGR Oceans, Vol. 118, Issue 1, 26-42.

- Gitelson AA, Buschmann C, Lichtenthaler HK (1999) The Chlorophyll Fluorescence Ratio F735/F700 as an Accurate Measure of the Chlorophyll Content in Plants. Remote Sens Environ Vol. 69, Issue 3, 296-302.

- Gordon HR, Wang M (1994) Retrieval of water-leaving radiance and aerosol optical thickness over the oceans with SeaWiFS: A preliminary algorithm. Appl Optics 33: 443-452.

- Gower JFR, Brown L, Borstad GA (2004) Observation of chlorophyll fluorescence in west coast waters of Canada using the MODIS satellite sensor. Can J Remote Vol. 30, No. 1, 17-25.

- Horler DNH, Dockray M, Barber J (1983) The red edge of plant leaf reflectance. Int J Remote Sens 4:2, 273-288.

- Hu C, (2009) A novel ocean colour index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens Environ 113, 2118–2129.

- Hu, L. Hu C. Ming-Xia HE (2017) Remote estimation of biomass of Ulva prolifera macroalgae in the Yellow Sea. Remote Sens Environ Vol. 192, 217-227.

- Joniver C, Moore P, Woolmer A, Adams J (2019) Is sustainable harvesting of opportunistic macroalgae blooms an ecological, social and economic solution? International Seaweed Symposium, 10.13140/RG.2.2.30406.11849.

- Keith DJ (2009) Estimating Chlorophyll Conditions in Southern New England Coastal Waters from Hyperspectral Aircraft Remote Sensing. Remote sensing of Coastal Environments, ed. Weng Q, Indiana State University, 151-172.

- Larcher W (1980) Physiological Plant Ecology. 2nd ed. Springler: Berlin.

- Lavery PS, Lukatelich RJ, McComb AJ (1991) Changes in the Biomass and Species Composition of Macroalgae in Eutrophic Estuary. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 33, 1-22.

- Lee Z, Carder KL, Steward RG, Peacock TG, Davis CO, Mueller JL Remote sensing reflectance and inherent optical properties of oceanic waters derived from above-water measurements, in Ocean Optics XIII 2963, S. G. Ackleson and R. J. Frouin, Eds., 160-166 (1997).

- Lewis NS, DeWitt TH (2017) Effect of Green Macroalgal Blooms on the Behaviour, Growth, and Survival of Cockles (Clinocardium nuttallii) in Pacific NW Estuaries. Mar Ecol Progr Ser. 582: 105-120.

- Li S, Ganguly S, Dungan JL, Wang WL, Nemani RR (2017) Sentinel-2 MSI Radiometric Characterization and Cross-Calibration with Landsat-8 OLI. Advances in Remote Sensing 6, 147-159.

- Lillesand TM, Kiefer RW, Chipman JW (2015) Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation. 7th ed. Wiley, USA.

- Lyons DA, Mant RC, Bullen F, Kotta J, Rilov G, Crowe TP (2012) What are the effects of macroalgal blooms on the structure and functioning of marine ecosystems? A systematic review protocol. Environ Evid 1:7.

- Matthews MW, Bernard S, Lain LR (2012) An algorithm for detecting trophic status (chlorophyll-a), cyanobacterial-dominance, surface scums and floating vegetation in inland and coastal waters', Remote Sens Environ 124, 637-652.

- Medina-Lopez E, Navarro G, Santos-Echeandia J, Bernardes P, Caballero I (2023) Machine Learning for Detection of Macroalgal Blooms in the Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon Using Sentinel-2. Remote Sens 15, 1208.

- Miyashita H, Ikemoto H, Kurano N, Adachi K, Chihara M, Miyachi S (1996) Chlorophyll d as a major pigment. Nature 383, 402.

- Morton AM (1975) Biochemical Spectroscopy. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley and Sons.

- Paulimer A, Tatlian T, Reveillac E, Le Luherne E, Ballu S, Lepage M, Le Pape O (2018) Impacts of green tides on estuarine fish assemblages. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 213: 176-184.

- Raffaelli DG, Raven JA, Poole LJ (1998) Ecological Impact of Green Macroalgal Blooms. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 36, 97-125.

- Richardson LL (1996) Remote sensing of algal bloom dynamics, Bioscience, 46, 492-501.

- Rouse Jr JW, Haas RH, Schell JA, Deering DW (1974) Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In: NASA. Goddard Space Flight Center 3d ERTS-1 Symposium, Vol. 1/A, 309–317.

- Scanlan CM, Foden J, Wells E, Best MA (2007) The monitoring of opportunistic macroalgal blooms for the water framework directive. Mar Pollut Bull 55, 162-171.

- Scott A (1999) Ecological History of the Tuggerah Lakes. CSIRO Land and Water, Canberra.

- Shen L, Xu H, Guo X (2012) Satellite remote sensing of harmful algal blooms (HABS) and a potential synthesized framework. Sensors, 12 (6), 7778-7803.

- Shi W, Wang M (2009) Green macroalgae blooms in the Yellow Sea during the spring and summer of 2008. J Geophys Res 114, p. C120010.

- Sukhinov A, Belova Y, Chistyakov A, Beskopylny A, Meskhi B. Mathematical Modeling of the Phytoplankton Populations Geographic Dynamics for Possible Scenarios of Changes in the Azov Sea Hydrological Regime. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3025.

- Valiela I, McClelland J, Hauxwell J, Behr PJ, Hersh D, Fereman K (1997) Macroalgal blooms in shallow estuaries Controls and ecophysiological and ecosystem consequences. Limnol Oceanogr 42/5, p. 2, 1105-1118.

- Wang C, Yu R, Zhou MJ (2012) Effects of the decomposing green macroalga Ulva (Enteromorpha) prolifera on the growth of four red-tide species. Harmful Algae, 16. 12–19.

- Wang XH, Qiao F, Lu J, Gong F (2011) The turbidity maxima of the northern Jiangsu shoal-water in the Yellow Sea, China, Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 93, 202- 211.

- Xing Q, Hu C (2016) Mapping macroalgal blooms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea using HJ-1 and Landsat data: Application of a virtual baseline reflectance height technique. Remote Sens Environ 178, 113–126.

- Zhang H, Qiu Z, Devred E, Sun D, Wang S, Yu Y (2019) A simple and effective method for monitoring floating green macroalgae blooms: a case study in the Yellow Sea. Optics Express, Vol. 27, No. 4, 4528 – 4548.

| Index | FAI | VB-FAH | MCI | ABDI | NDVI | SABI |

| True Positive | 170 | 172 | 157 | 130 | 183 | 183 |

| True Negative | 525 | 399 | 330 | 300 | 194 | 194 |

| False Positive | 270 | 372 | 442 | 495 | 601 | 601 |

| False Negative | 13 | 6 | 25 | 53 | 0 | 0 |

| Accuracy | 0.711 | 0.602 | 0.510 | 0.440 | 0.385 | 0.385 |

| . | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| TP | 43 | 49 | 52 | 52 | 9 | 18 | 37 |

| FP | 9 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| TN | 107 | 99 | 90 | 100 | 153 | 137 | 116 |

| FN | 7 | 15 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Overall Classification Error: (FP+FN)/(FP+TP+FN+TN) | 0.0963855 | 0.1084337 | 0.1445783 | 0.0843373 | 0.0240963 | 0.066265 | 0.0783132 |

| Sensitivity | 0.9386 | 0.8684 | 0.8411 | 0.9615 | 0.9808 | 0.9448 | 0.9134 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| TP | 50 | 44 | 47 | 57 | 9 | 13 | 34 |

| FP | 2 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| TN | 103 | 113 | 101 | 98 | 153 | 144 | 125 |

| FN | 11 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Overall Classification Error: (FP+FN)/(FP+TP+FN+TN) | 0.0783132 | 0.0542169 | 0.108433 | 0.066265 | 0.0240963 | 0.0542169 | 0.0421686 |

| Sensitivity | 0.9035 | 0.9912 | 0.9439 | 0.9423 | 0.9808 | 0.9931 | 0.9843 |

| Sample point number | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| -0.2268212 | -1.541815 | -0.9437874 | -0.0013445 | -1.673069 | -1.42642 | -1.921111 | |

| 0.04458782 | 0.03542325 | 0.03794499 | 0.0367267 | 0.0248626 | 0.02434152 | 0.0313547 | |

| po | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.54 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| TP | 43 | 44 | 47 | 57 | 8 | 16 | 34 |

| FP | 9 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| TN | 107 | 112 | 100 | 96 | 153 | 139 | 123 |

| FN | 7 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Overall Classification Error: (FP+FN)/(FP+TP+FN+TN) | 0.09638554 | 0.06024096 | 0.114457 | 0.0783132 | 0.0301204 | 0.066265 | 0.54216 |

| Sensitivity | 0.9386 | 0.9825 | 0.9346 | 0.9231 | 0.9808 | 0.9586 | 0.9685 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| -0.1870363 | -1.600238 | -0.972799 | 0.0372666 | -3.437035 | -1.490092 | -2.935952 | |

| 0.04724447 | 0.03808789 | 0.03936414 | 0.0391434 | 0.110245 | 0.02668866 | 0.0487624 | |

| po | 0.41243 | 0.54342 | 0.52528 | 0.43889 | 0.23194 | 0.4202 | 0.40988 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).