2. The Two Major Challenges of AI and Two Types of Response

The current technological supercycle, as Amy Webb puts it (2024), based on the combination of artificial intelligence, connected ecosystems of things and biotechnology, promises the accelerated expansion of an economy heavily based on them, which will undoubtedly be a challenge for our current way of life. In an interview conducted in 2023, the CEO of Mercedes Benz points out a series of major changes in all sectors of society: - Rapid legal advice, with 90% accuracy (compared to 70% for human lawyers); - Self-driving cars: when we need them, freeing up traffic on urban roads; - In healthcare, a device (like the “Tricorder” from the Star Trek series) that will work on a mobile phone and analyze 54 biomarkers, preventing health-related actions; - In education, 70% of all human beings are expected to own a smartphone: which will give them access to world-class education; - In agriculture, affordable agricultural robots will emerge: even in the least developed countries, farmers will be able to manage their own production. The interview shows that the interviewee has a fantastically positive view of the truly radical changes that, in his opinion, are coming. But the change may not be so positive Kai-Fu Lee (2018), a well-known AI expert, describes the four waves in which AI is evolving and occupying more and more spaces: internet AI, business AI, perception AI and finally, autonomous AI. It is the fourth wave, that of autonomous AI, that interests us in this case: when AI systems have learned to see and hear people, they will be able to identify them and define behaviors that correspond to each person’s expectations. Scholars of this problem consider that the expansion of AI systems in the field of productive activities places us before a bifurcation with two contexts:

- Context A: the decrease in human employment will be limited (20% to 30% of the current number), maintaining the idea that we will work in collaboration with AI systems.

- Context B: an extreme reduction in human employment, with only 10% to 20% of the current number of jobs remaining in human hands, with the majority of human operators left without a defined productive occupation.

The two contexts create situations that naturally require different responses. But both require a proactive, intelligent response, since either of them require significant changes in socioeconomic structures and processes and in the multiple contexts of human life. Context A, however, is less of a departure from current socioeconomic structures and processes than seems inevitable in context B; since the response to the challenges will be the development of the skills and attitudes essential for the effectiveness of mixed teams, humans and AI systems, while at the same time reducing the anxiety of human operators. Many scholars even believe that this attitude and the skills that accompany it are the most effective means of putting AI systems at the service of humanity.

Context A: Developing the essential skills and attitudes for the effectiveness of mixed teams - humans and AI systems Several studies have shown that mixed teams of humans and AI systems achieve better results than those obtained by teams consisting solely of robotics or solely of humans (Christian, 2020; Klumpp et al., 2019; Woo and Kubota, 2016). DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) itself has programs in this sense, seeking to build algorithms that, in addition to approaching human decision-making methods and thus facilitating interaction with human operators, respond to their concerns and reduce their anxiety and stress (DARPA, 2023). The objective of this perspective is to prepare human beings for the challenges of the complexity of the current and future world, through comprehensive training, which is not limited to preparing ultra-specialized technicians in a single technology, but rather human operators capable of a global vision and interdisciplinary reasoning. Those responsible for complex democracies will promote educational programs that increase knowledge across the full range of physical, social and behavioral sciences, integrating technical and organizational innovations into a reflection committed to the search for an increasingly human meaning of life.

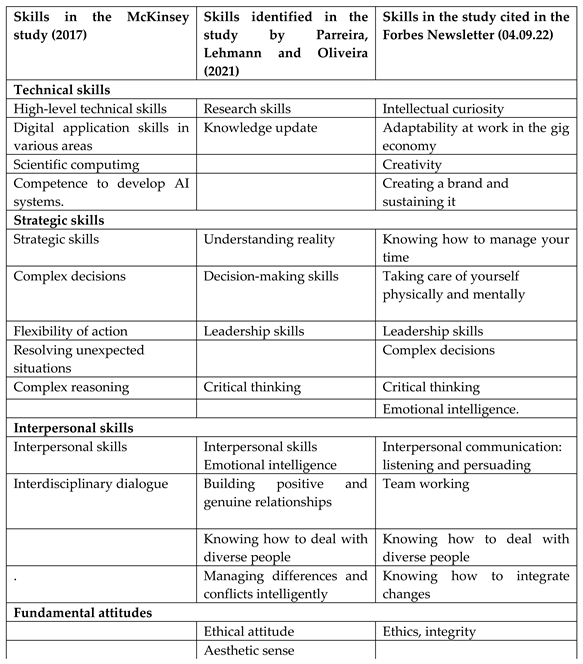

Table 1 lists these skills and attitudes obtained in three studies on the subject.

It is certainly interesting that three completely independent studies have identified, roughly speaking, the same set of skills and attitudes that will enable us to deal with the expansion of AI systems in the economy of the future. And it is the acquisition of these skills and attitudes that will be facilitated by the constitutive factors of a culture of trust, as we hope to show with the research carried out.

What if things do not go so well and employment is reduced to 10 or 20% of what it is today?

We will fall into context B and we will have no choice but to start by keeping in mind Harari’s (2018) desire, expressed in writings and interviews on the subject:

To face the unprecedented economic and technological disruptions taking place in this century, we need to develop new economic and social models as quickly as possible, guided by the principle of protecting humans, not jobs... Our focus must be on protecting people’s needs, their well-being and their social status.

Context B: an extreme reduction in human employment In the case of context B, more than developing the appropriate skills, it is necessary to invent innovative solutions, sufficiently complex and creative to adapt to the structures and processes of a radically new context. This is the second line of response that we will have to put into practice if we want to safeguard the quality of human life contexts: increasing our cognitive flexibility and our level of interdisciplinary knowledge of reality. Our previous studies (Parreira and Lorga da Silva, 2021) have shown that the practice of the Complex Reasoning Paradigm (PARC) and its translation into technologies based on in-depth interdisciplinary knowledge of the physical sciences and social sciences is essential for raising the cognitive level. PARC is first based on Kurt Gödel’s (1931) studies on undecidables (propositions that are true but undemonstrable within the system of which they are an essential part); was complemented by theoretical contributions from prominent authors, such as Prigogine (Prigogine & Stengers, 1984), with the idea of bifurcation, to give rise to new social structures, or based on power or based on information; and Morin (who developed the fundamental data of the Complexity Paradigm (Morin, 1967; 1984; 1990; 2011). PARC raises our level of knowledge and interdisciplinary vision of reality, increases our emotional intelligence in facing and seeking solutions to problems, and allows us to act with an objectivity as rich in information as possible, as established in PARC postulate 4: To understand a system or solve a problem with a certain level of informational complexity, a cognitive complexity of a level equal to or greater than the informational complexity of that system or problem is required. It is at this level of cognitive complexity that the preventive and intervention actions required to effectively face emerging problems in context B must be situated. And in this case too, a culture of trust appears as a solid support for the learning of these attitudes and skills.

Context B: Preventive Actions

First: to analyze in depth the contribution of the various facets of work to maintaining our quality of life: not only as a source of subsistence, but as a context for learning skills, establishing personal relationships and an activity that co-defines the meaning of our lives, to name just the main ones.

Second: given the likely reduction in human work in companies, it would be sensible to reduce weekly working hours, in order to minimize the stress of the people affected and safeguard their quality of life.

Intervention Actions

The intervention measures would aim to directly help the affected people overcome the condition of unemployment, keeping them in diverse activities, as would be normal if they had a job. Various activity profiles may coexist, but the central core of all of them will be skills development programs that favor different types of social integration, from carrying out occasional work to training as entrepreneurs, who are expected to play a relevant role in knowledge societies.

In order to verify to what extent a culture of trust can be a favorable instrument for implementing the measures set out for contexts A and B, research was conducted on the construct of trust, in an effort to integrate into a single, comprehensive concept the contributions of the various authors who dedicated themselves to its study. This concept was then subjected to empirical research on the factors that constitute it and generate trust behavior, thus answering the research question that is the origin of the research carried out in this article.

The Multiple Facets of Trust: The Interpersonal, Institutional and Societal Planes

Trust can be public or private, reflect a moral commitment or be the result of a simple arrangement of circumstances, or be seen as a public good, a “hidden wealth” (Halpern, 2010) or a true “invisible tax” when absent (Fukuyama, 1996). It is this multiplicity of planes that we will review, in search of the unifying concept of the different perspectives.

The Interpersonal Dimension of Trust

Psychologists have approached trust primarily as an individual characteristic (Rotter, 1967; Novelli, Fisher and Mazzon, 2006). From this perspective, Hardin (1992) observes that the rational interpretation of trust includes two central elements: knowledge of the other, which allows one to trust him/her; and the incentives of the trusted person (Finuras, 2013), by showing that he/she will honor the trust placed in him/her. Kuo and Yu (2009) also assert that the development of trust is strongly based on interpersonal relationships; and Cruz et al. (2018) point out that inclusion is a very strong attribute of trust, measured based on interactions established between people. A study carried out by Marina Barros (Barros, Formiga and Vasconcelos, 2021) confirms this result, making it quite clear that emotional closeness is a relevant psychological factor in the emergence of trust: trust is greater between family members (91% of respondents), then between friends (78%), then between neighbors and between coworkers (67%). Baier (2004) also assumes that goodwill is the crucial element for interpersonal trust; and Nooteboom (1992) and Putnam (2001) point out, in addition to goodwill, trust in competence, that is, the ability to act according to expectations, as a complement to good faith and rectitude of intentions. In this way, the interpersonal dimension of trust seems to be well established.

Trust from the Perspective of Social Processes

Economists, sociologists and political scientists have studied trust as an institutional phenomenon with extrinsic value and with a real impact on the economy and transaction costs. Zand (1972), for example, states that trust is a way of regulating our dependence on others, and Luhmann (1995) confirms that, in situations of interdependence, it allows for the reduction of uncertainty. Anthropologists have analysed it as a cultural phenomenon, indicating that in societies with more ‘individualistic’ and ‘universalist’ cultural values there seems to be more trust than in societies with more ‘collectivist’ or ‘exclusivist’ cultural values (Hofstede Hofstede and Minkov, 2010; Minkov, 2011; Uslaner, 2002). an economic perspective, trust is identified as “having faith in the ability and intention of a buyer to pay in the future for goods provided without payment in the present” (Sabourian and Anderlini, 1992); and Fukuyama (1996) insists that the greater the trust in institutions and relationships, the lower the transaction costs. McAllister, (1995), in turn, suggests that trust is a fundamental element for the development of economies, social relations and society in general. Fukuyama (2002), finally, argues that the formation of trust is inherent to the environment and the culture that shapes it, elevating trust to the position of a driving factor in cycles of social and economic development. In the field of politics, Almond and Verba (1963, p. 211) showed that a culture conducive to democracy presupposes a feeling of “trust and confidence” in the social environment; and, therefore, Power and Jamison (2005) argue that the design of the institutions themselves is a factor to consider: if the design of a political institution makes citizens see authorities as distant and, consequently, impossible to be held accountable, or even scrutinized, trust in these institutions diminishes. Therefore, a more complete understanding of trust requires a deeper understanding of the various expressions of the phenomenon itself, since empirical evidence supports that they are facets of trust that form a coherent construct of the phenomenon.

Barbara Misztal (1996) suggests that three dimensions should be distinguished in the analysis of trust: 1) stability (which represents the predictability, reliability and legibility of social reality); 2) cohesion (which can be seen as a dynamic of normative integration); and 3) collaboration (which refers to social cooperation). Nooteboom (2006), in turn, proposes, in agreement with Misztal, that two major dimensions should be distinguished: trust (an attitude of felt trust) and confidence (a calculated level of trust). And although there is a certain tendency among social scientists to merge both terms, many recall the German proverb Vertrauen ist gut, Sicherheit noch besser (trust is good, certainty is better), to distinguish the cognitive and emotional states of the constructo

Towards an Integrative Concept of the Core Dimensions of Trust

The contribution of these authors leads us to propose a synthesis that integrates the topics highlighted by each one into two specific types of trust:

- trust as an attitude, based on emotional expectation, created in a personal relationship with a positive tone;

- trust as creditation or accreditation, with various levels of certainty, based on the assessed probability of certain behavior,

The first type of trust - trust as an attitude based on an intersubjective relationship - is more emotional and characteristic of human interactional contexts, between actors who have the identity of subjects, of people, aware of their own motivations and objectives, drivers of a self-constructed destiny. The second type of trust - trust as accreditation - is more cognitive and allows for two levels of security, which are part of the structural security: the techno-scientific level, specifically the responsibility of experts; and the user level, whose trust is much more subjective and is based on the probability of obtaining responses that facilitate the achievement of their objectives and the results that the user wants. The two dimensions of trust are present every time we express it in relation to someone or some entity. What varies, depending on the situation, is the proportion of each component in the trust that we express, a proportion that may be more or less appropriate to the moment and the context. The choice of an appropriate combination of the two dimensions will be a useful tool if we know how to characterize the type of actor with whom we are establishing a relationship: we will be able to face more intelligently the various types of problems encountered in the socioeconomic contexts of today’s complex societies.

It is this theme of trust that was the subject of the empirical research presented below, with the aim of evaluating whether the factors that promote trust, at the interpersonal, institutional and societal levels, and the impact of trust patterns on the quality of social relations will be a good support for facing the challenges posed by the accelerated expansion of artificial intelligence systems.

3. Empirical Research; Factors of a Culture of Trust and Their Impact on Responding to AI Challenges

The empirical research on the topic of trust had two phases: bibliographic exploration of texts on the topic, aiming to create a theoretical support that would ensure a correct interpretation of the data obtained and support the development of a questionnaire with construct validity; and the development of the questionnaire - QUEST-CONF - with the aim of obtaining responses that identify the factors that promote trust, at the interpersonal, institutional and societal levels, and assess the impact of trust patterns on the quality of relationships, at these three levels.

Research Question

To what extent do the structuring factors of a culture of trust favor the learning of attitudes and skills that ensure the consistent practice of the two lines of action necessary to effectively face the challenges of the two contexts (A and B) that the expansion of AI systems in the economy and in life in general pose to human agents.

Based on this question, two guiding hypotheses were defined:

H1 - A culture of trust creates an environment favorable to the development of appropriate skills to respond to the challenges of an economic context of type A.

H2 - A culture of trust creates the appropriate environment for the development of the attitudes and skills necessary for the construction of structures and processes required by the current socioeconomic conditions in a context of type B.

Methodological Analysis Procedures

Qualitative analysis of the data and its interpretation, based on the criteria of the trust model, on the criteria defining complex democracy and its implications for the regulation of the various types of market; and statistical analysis of the variables and factors of trust, with Stata (StataCorp. 2023).

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire used has two parts: the first, in the form of a semantic differential (Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1957), on the factors that can contribute to the creation of a culture of trust in today’s societies (33 items); the second, on the impact of trust on social processes (16 items). The items of the two parts of the scale are evaluated based on an interval scale, created and validated in previous studies (Parreira, 2003; Parreira and Lorga da Silva, 2014; 2016). The questionnaire was sent and answered online, through Google Forms.

The Sample

For the purposes of applying the questionnaire interviews, an intentional sample was used consisting of qualified respondents in Brazil and Portugal (university professors and technicians working in activities related to the Social Sciences), totaling 106 respondents (

Table 2).

The characteristics of the sample allow us to assume that the responses on the role of trust are well-informed. They will thus allow us to consider that the behavioural patterns identified by the respondents as constituting a culture of trust facilitate the adoption of intelligent measures to respond to the challenge posed by AI systems: - first, to the accelerated development of human skills necessary for the adoption of collaborative practices with AI systems and, consequently, favourable to the sustainability of human employment (context A, pp. 6-8) - second, to the innovative effort required to creatively adapt to an extreme scenario of drastic reduction in productive human work, developing and consolidating behavioural patterns that may be even more favourable to the quality of human life.

The Culture of Trust and Dealing with the Innovations That Will Shape Our Future

The techno-social innovations currently underway will tend to create one of two contexts (A and B) identified above as the two probable lines of socio-economic reorganization of current societies. The first question in this regard is to know to what extent a culture of trust favors the acquisition of diversified competence patterns that enable human operators to deal with AI systems, first in the productive activities of context A, in which the reduction of human employment will be limited and the economy will be based on extensive collaboration between human operators and AI systems.

The Role of a Culture of Trust in Building Adaptive Responses to Context A

Table 1 highlights the skills identified in three studies for this type of context; and

Table 3 highlights the factors of a culture of trust that appear to be most conducive to the adoption of attitudes and skills conducive to the creation of collaborative teams of human operators and AI systems. High averages in the factors conducive to a culture of trust indicate greater support for the idea that a culture of trust provides a context conducive to the development of the attitudes and skills necessary for a positive response to the expansion of AI systems.

The averages achieved in these factors are all very high: the amplitude of the scale is between 0.37 (not at all) and 9.49 (extremely), i.e., 9.12; as all the factors are above (and almost all very above) the mathematical average of the scale (4.56), we consider the result to confirm H1, especially since the sample data are consistent with the interpretation of the results. Only one of the variation coefficients is slightly superior to 0,3 and other concerning “The greater the trust, the less waste of material and human resources” is superior to 0,3 (both bold signaled), showing a elevate dispersion concerning this last response ≈0,5.

The second guiding hypothesis of the research concerns context B, characterized by an extreme reduction in human employment in economic activities. It is a context radically different from the current one, which requires a set of large-scale changes in structure and social behavior, implemented in incremental but also radical innovations (Laranja, 1996). The actions to respond to these changes were described above as preventive and intervention actions (pp.10-13): they require, mainly from leaders, but also from citizens, an attitude and a range of skills that are less linked to the operational level and more to the strategic level, such as complex critical thinking; creativity, individual and collective resilience; the ability to improvise and high citizenship behavioural patterns, particularly in the factors of altruism, initiative and conscientiousness.

In relation to these attitudes and behavioural patterns, the culture of trust can be an even more sustainable support, as can be inferred from the content of the factors presented in

Table 4: they show that a culture of trust among citizens and in society in general will be one of the greatest factors impacting the capacity to adapt to the conditions of context B (extreme reduction in employment).

- The free circulation of information will certainly be an extremely fertile ground for innovative solutions, especially if accompanied by transparency in decisions and easy contact between different people; and the promotion of innovative decisions is all that is needed when problems are complex.

- The prompt ‘confrontation of problems and the rapid implementation of important decisions’ (item 11) is another factor that is highly favorable to the effectiveness of the response to complex challenges with risky consequences, as Beck (1992) highlighted; and we know that this is the case with the problems associated with the expansion of AI systems in the most diverse areas of the Economy.

- Avoiding mistakes (item 36) and making more objective decisions (item 49) are undoubtedly crucial factors for intelligent responses to the challenges to be faced, in any of the contexts, but particularly in context B. These results are such as to validate H2, since they contribute to increasing the quality of decisions and the confrontation of challenges and problems, thus contributing to the acceptance and implementation of measures capable of responding to the problems created in context B, if this materializes in the near future.