Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

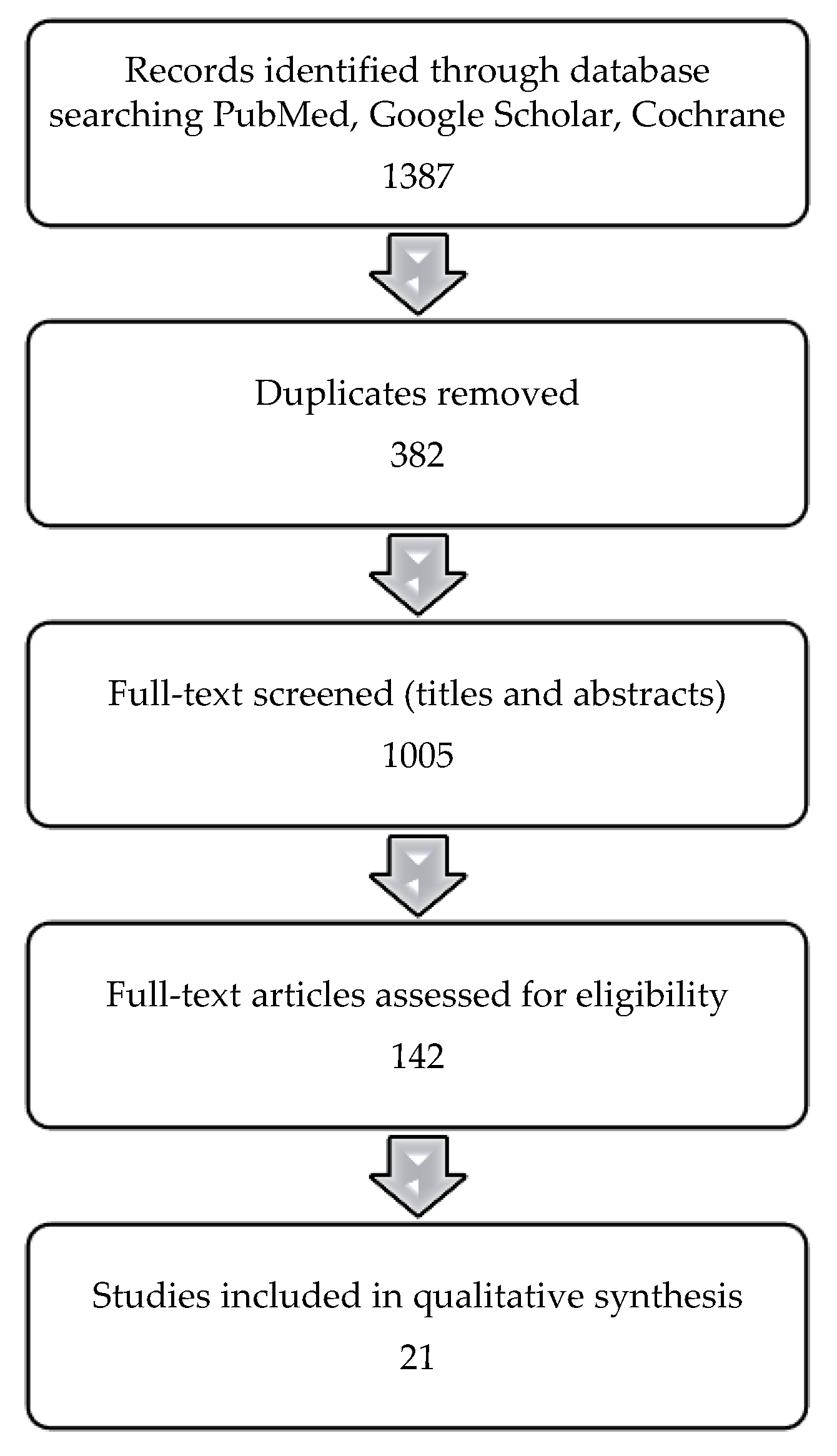

2. Materials and Methods

- Peer-reviewed articles published between January 2004 and February 2024

- Adult populations aged 18 years and above

- Studies investigating the association between thyroid function (hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, subclinical dysfunction) and T2DM

- Observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) and interventional studies

- Clinical guidelines from internationally recognized endocrinology and diabetes organizations

- Non-English language publications

- Pediatric or adolescent populations (<18 years)

- Studies focused exclusively on type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes

- Animal experiments or in vitro research

- Case reports, editorials, letters to the editor, or opinion pieces without original research data

- Articles lacking a clear diagnostic definition for thyroid dysfunction

3. Results

3.1. Unravelling the Prevalence of Thyroid Dysfunction in T2DM

3.2. Thyroid Hormones and Glucose Metabolism: Insights into T2DM Pathogenesis

3.3. Thyroid Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance: Partners in T2DM Pathogenesis?

3.4. Hypothyroidism and T2DM: Is There a Link Between T2DM and Hypothyroidism?

3.5. Effects of Hyperthyroidism on Glucose Metabolism

3.6. Genetic Influences on Thyroid Function and Glucose Metabolism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NHANES III | Third United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| NHIRD | National Health Insurance Research Database |

| UCP-3 | Uncoupling Proteins |

| GLUT | Glucose Transporter in the plasma membrane |

| NEFA | Noesterified Fatty Acids |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| TSH | Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

| TH | Thyroid Hormones |

| SHR | Sublinical Hyperthyroidism |

| FT4 | Free Thyroxine |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| TD | Thyroid Disorders |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| T3 | Triiodothyronine |

| IR | Insulin Resistance |

| HR | Hyperthyroidism |

References

- Committee ADAPP, ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Bannuru RR, Beverly EA, Bruemmer D, et al. Summary of Revisions: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024;47:S5–10. [CrossRef]

- IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition. n.d.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:301–16. [CrossRef]

- Chiovato Flavia Magri Allan Carlé L. Hypothyroidism in Context: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going. Adv Ther n.d.;36. [CrossRef]

- Han C, He X, Xia X, Li Y, Shi X, Shan Z, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10. [CrossRef]

- Roa Dueñas OH, Van Der Burgh AC, Ittermann T, Ligthart S, Ikram MA, Peeters R, et al. Thyroid Function and the Risk of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2022;107:1789–98. [CrossRef]

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Dana Flanders W, Harry Hannon W, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. Serum TSH, T4, and Thyroid Antibodies in the United States Population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489–99. [CrossRef]

- Khassawneh AH, Al-Mistarehi AH, Alaabdin AMZ, Khasawneh L, Alquran TM, Kheirallah KA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients: A case–control study. Int J Gen Med 2020;13:803–16. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari S, Ali G, Memom M, Sandeelo N, Alvi H, Talib A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction amongst patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Pakistan. J Family Med Prim Care 2022;11:2739. [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna SU, Ezeani IU, Okafor CI, Chinenye S. Association between glycemic status and thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2019;12:1113–22. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha B, Rai CK. Hypothyroidism among Type 2 Diabetic Patients Visiting Outpatient Department of Internal Medicine of a Tertiary Care Centre: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association 2023;61:325–8. [CrossRef]

- Ishay A, Chertok-Shaham I, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in women with type 2 diabetes. n.d.

- Raghuwanshi PK, Rajput DPS, Ratre BK, Jain R, Patel N, Jain S. Evaluation of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients. Asian J Med Sci 2014;6:33–7. [CrossRef]

- Mehalingam V, Sahoo J, Bobby Z, Vinod K. Thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with diabetic complications. J Family Med Prim Care 2020;9:4277. [CrossRef]

- Elgazar EH, Esheba NE, Shalaby SA, Mohamed WF. Thyroid dysfunction prevalence and relation to glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 2019;13:2513–7. [CrossRef]

- Chubb SAP, Peters KE, Bruce DG, Davis WA, Davis TME. The relationship between thyroid dysfunction, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. Acta Diabetol 2022;59:1615–24. [CrossRef]

- Subekti I, Pramono LA, Dewiasty E, Harbuwono DS. Thyroid Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. vol. 49. 2017.

- Pramanik S, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay P, Bhattacharjee R, Mukherjee B, Mondal SA, et al. Thyroid status in patients with Type 2 diabetes attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Eastern India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2018;22:112–5. [CrossRef]

- Eom YS, Wilson JR, Bernet VJ. Links between Thyroid Disorders and Glucose Homeostasis. Diabetes Metab J 2022;46:239–56. [CrossRef]

- Venditti P, Reed TT, Victor VM, Di Meo S. Insulin resistance and diabetes in hyperthyroidism: a possible role for oxygen and nitrogen reactive species. Free Radic Res 2019;53:248–68. [CrossRef]

- Mullur R, Liu YY, Brent GA. Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Metabolism. Physiol Rev 2014;94:355. [CrossRef]

- Rong F, Dai H, Wu Y, Li J, Liu G, Chen H, et al. Association between thyroid dysfunction and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. BMC Med 2021;19. [CrossRef]

- Biondi B, Kahaly GJ, Robertson RP. Thyroid Dysfunction and Diabetes Mellitus: Two Closely Associated Disorders. Endocr Rev 2019;40:789–824. [CrossRef]

- Solá E, Morillas C, Garzón S, Gómez-Balaguer M, Hernández-Mijares A. Association between diabetic ketoacidosis and thyrotoxicosis. Acta Diabetol 2002;39:235–7. [CrossRef]

- Hage M, Zantout MS, Azar ST. Thyroid disorders and diabetes mellitus. J Thyroid Res 2011;2011. [CrossRef]

- Jali M V., Kambar S, Jali SM, Pawar N, Nalawade P. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 2017;11:S105–8. [CrossRef]

- Demitrost L, Ranabir S. Thyroid dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A retrospective study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2012;16:334. [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi PK, Rajput DPS, Ratre BK, Jain R, Patel N, Jain S. Evaluation of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients. Asian J Med Sci 2014;6:33–7. [CrossRef]

- Jun JE, Jee JH, Bae JC, Jin SM, Hur KY, Lee MK, et al. Association Between Changes in Thyroid Hormones and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Seven-Year Longitudinal Study. Https://HomeLiebertpubCom/Thy 2017;27:29–38. [CrossRef]

- de Vries TI, Kappelle LJ, van der Graaf Y, de Valk HW, de Borst GJ, Nathoe HM, et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels in the normal range and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 2019;56:431–40. [CrossRef]

- Chang CH, Yeh YC, Shih SR, Lin JW, Chuang LM, Caffrey JL, et al. Association between thyroid dysfunction and dysglycaemia: a prospective cohort study. Diabetic Medicine 2017;34:1584–90. [CrossRef]

- Al-Geffari M, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Youssef AM, Alnaqeb D, Al-Rubeaan K. Risk factors for thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients in a highly diabetes mellitus prevalent society. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Park SY, Choi CS. Insulin Resistance: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Diabetes Metab J 2021;46:15. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A, Atkinson RL. Obesity | Complications. Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition 2005:406–13. [CrossRef]

- Gupta A. Etiopathogenesis of insulin resistance. Understanding Insulin and Insulin Resistance 2022:231–73. [CrossRef]

- Insulin Resistance - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics n.d. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/insulin-resistance (accessed April 26, 2025).

- Courtney CH, Olefsky JM. Insulin Resistance. Mechanisms of Insulin Action: Medical Intelligence Unit 2023:185–209. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, Lian F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1149239. [CrossRef]

- Kocatürk E, Kar E, Küskü Kiraz Z, Alataş Ö. Insulin resistance and pancreatic β cell dysfunction are associated with thyroid hormone functions: A cross-sectional hospital-based study in Turkey. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 2020;14:2147–51. [CrossRef]

- Gierach M, Gierach J, Junik R. Insulin resistance and thyroid disorders. Endokrynol Pol 2014;65:70–6. [CrossRef]

- Maratou E, Hadjidakis DJ, Kollias A, Tsegka K, Peppa M, Alevizaki M, et al. Studies of insulin resistance in patients with clinical and subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol 2009;160:785–90. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzu K, Segade F, Wong M, Clark OH, Perrier ND, Bowden DW. Glucose transporters in the thyroid. Thyroid 2005;15:545–50. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein SP, Haber RS. Differential regulation of glucose transporter isoforms by thyroid hormone in rat heart. BBA - Molecular Cell Research 1992;1136:302–8. [CrossRef]

- Matthaei S, Trost B, Hamann A, Kausch C, Benecke H, Greten H, et al. Effect of in vivo thyroid hormone status on insulin signalling and GLUT1 and GLUT4 glucose transport systems in rat adipocytes. Journal of Endocrinology 1995;144:347–57. [CrossRef]

- Santalucía T, Palacín M, Zorzano A. T3 strongly regulates GLUT1 and GLUT3 mRNA in cerebral cortex of hypothyroid rat neonates. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2006;251:9–16. [CrossRef]

- Torrance CJ, Devente JE, Jones JP, Dohm GL. Effects of Thyroid Hormone on GLUT4 Glucose Transporter Gene Expression and NIDDM in Rats. Endocrinology 1997;138:1204–14. [CrossRef]

- Lyu J, Imachi H, Yoshimoto T, Fukunaga K, Sato S, Ibata T, et al. Thyroid stimulating hormone stimulates the expression of glucose transporter 2 via its receptor in pancreatic β cell line, INS-1 cells. Scientific Reports 2018 8:1 2018;8:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis G, Mitrou P, Lambadiari V, Boutati E, Maratou E, Panagiotakos DB, et al. Insulin Action in Adipose Tissue and Muscle in Hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4930–7. [CrossRef]

- Sotak S, Felsoci M, Lazurova I. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease: A two-sided analysis. Bratislava Medical Journal 2018;119:361–5. [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez V, Salazar J, Añez R, Rojas M, Estrella V, Ordoñez M, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Subclinical Hypothyroidism: A Type 2 Diabetes-Dependent Association. J Thyroid Res 2018;2018. [CrossRef]

- Alsolami AA, Alshali KZ, Albeshri MA, Alhassan SH, Mohammed A, Qazli, et al. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism: A case–control study. Int J Gen Med 2018;11:457–61. [CrossRef]

- Chiovato Flavia Magri Allan Carlé L. Hypothyroidism in Context: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going. Adv Ther n.d.;36. [CrossRef]

- Nair A, Jayakumari C, Jabbar PK, Jayakumar R V., Raizada N, Gopi A, et al. Prevalence and Associations of Hypothyroidism in Indian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Thyroid Res 2018;2018. [CrossRef]

- Fang T, Deng X, Wang J, Han F, Liu X, Liu Y, et al. The effect of hypothyroidism on the risk of diabetes and its microvascular complications: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Talwalkar P, Deshmukh V, Bhole M. Prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension in india: A cross-sectional observational study. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2019;12:369–76. [CrossRef]

- Brenta G, Caballero AS, Nunes MT. Case finding for hypothyroidism should include type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome patients: A Latin American Thyroid Society (LATS) position statement. Endocrine Practice 2019;25:101–5. [CrossRef]

- Martinez B, Ortiz RM. Thyroid hormone regulation and insulin resistance: Insights from animals naturally adapted to fasting. Physiology 2017;32:141–51. [CrossRef]

- Majeed S, Hussein M, Abdelmageed RM. The Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Related Thyroid Diseases. Cureus 2021;13:e20697. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tana J. Insulin Resistance, Secretion and Clearance –Taming the Three Effector Encounter of Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:741114. [CrossRef]

- Althausen TL, Stockholm M. INFLUENCE OF THE THYROID GLAND ON ABSORPTION IN THE DIGESTIVE TRACT. Https://DoiOrg/101152/Ajplegacy19381233577 1938;123:577–88. [CrossRef]

- Hussein SMM, AbdElmageed RM. The Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Related Thyroid Diseases. Cureus 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis G, Parry-Billings M, Bevan S, Leighton B, Krause U, Piva T, et al. The effects of insulin on transport and metabolism of glucose in skeletal muscle from hyperthyroid and hypothyroid rats. Eur J Clin Invest 1997;27:475–83. [CrossRef]

- Rohdenburg GL. THYROID DIABETES. Endocrinology 1920;4:63–70. [CrossRef]

- Singh I, Srivastava MC. Hyperglycemia, keto-acidosis and coma in a nondiabetic hyperthyroid patient. Metabolism 1968;17:893–5. [CrossRef]

- Chambers TL. Coexistent coeliac disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperthyroidism. Arch Dis Child 1975;50:162–4. [CrossRef]

- Mitrou P, Raptis SA, Dimitriadis G. Insulin action in hyperthyroidism: A focus on muscle and adipose tissue. Endocr Rev 2010;31:663–79. [CrossRef]

- Maratou E, Hadjidakis DJ, Peppa M, Alevizaki M, Tsegka K, Lambadiari V, et al. Studies of insulin resistance in patients with clinical and subclinical hyperthyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol 2010;163:625–30. [CrossRef]

- Butterfield WJH, Whichelow MJ. Are thyroid hormones diabetogenic?. A study of peripheral glucose metabolism during glucose infusions in normal subjects and hyperthyroid patients before and after treatment. Metabolism 1964;13:620–8. [CrossRef]

- Orsetti A, Collard F, Jaffiol C. Abnormalities of carbohydrate metabolism in experimental and clinical hyperthyroidism: Studies on plasma insulin and on the A- and B-chains of insulin. Acta Diabetologia Latina 1974;11:486–92. [CrossRef]

- Seino Y, Taminato T, Kurahachi H, Ikeda M, Goto Y, Imura H. Comparative insulinogenic effects of glucose, arginine and glucagon in patients with diabetes mellitus, endocrine disorders and liver disease. Acta Diabetol Lat 1975;12:89–99. [CrossRef]

- Gierach M, Gierach J, Junik R. Insulin resistance and thyroid disorders. Endokrynol Pol 2014;65:70–6. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis GD, Raptis SA. Thyroid hormone excess and glucose intolerance. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2001;109 Suppl 2. [CrossRef]

- Mendez DA, Ortiz RM. Thyroid hormones and the potential for regulating glucose metabolism in cardiomyocytes during insulin resistance and T2DM. Physiol Rep 2021;9:e14858. [CrossRef]

- Mitrou P, Raptis SA, Dimitriadis G. Insulin Action in Hyperthyroidism: A Focus on Muscle and Adipose Tissue. Endocr Rev 2010;31:663–79. [CrossRef]

- Salleh M, Ardawi M, Khoja SM. Effects of hyperthyroidism on glucose, glutamine and ketone-body metabolism in the gut of the rat. International Journal of Biochemistry 1993;25:619–24. [CrossRef]

- Wang C. The Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Related Thyroid Diseases. J Diabetes Res 2013;2013:390534. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadis G, Koufakis T, Kotsa K. Epidemiological, Pathophysiological, and Clinical Considerations on the Interplay between Thyroid Disorders and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina 2023, Vol 59, Page 2013 2023;59:2013. [CrossRef]

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:301–16. [CrossRef]

- Duntas LH, Orgiazzi J, Brabant G. The interface between thyroid and diabetes mellitus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hussein SMM, AbdElmageed RM. The Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Related Thyroid Diseases. Cureus 2021;13:e20697. [CrossRef]

- panicker V. Genetics of Thyroid Function and Disease. Clin Biochem Rev 2011;32:165.

- Sterenborg RBTM, Steinbrenner I, Li Y, Bujnis MN, Naito T, Marouli E, et al. Multi-trait analysis characterizes the genetics of thyroid function and identifies causal associations with clinical implications. Nature Communications 2024 15:1 2024;15:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Biondi B, Kahaly GJ, Robertson RP. Thyroid Dysfunction and Diabetes Mellitus: Two Closely Associated Disorders. Endocr Rev 2019;40:789–824. [CrossRef]

- Eom YS, Wilson JR, Bernet VJ. Links between Thyroid Disorders and Glucose Homeostasis. Diabetes Metab J 2022;46:239. [CrossRef]

- Medici M, Visser TJ, Peeters RP. Genetics of thyroid function. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;31:129–42. [CrossRef]

- Zuanna TD, Pitter G, Canova C, Simonato L, Gnavi R. A systematic review of case-identification algorithms based on italian healthcare administrative databases for two relevant diseases of the endocrine system: Diabetes mellitus and thyroid disorders. Epidemiol Prev 2019;43:17–36. [CrossRef]

- Lee SA, Choi DW, Kwon J, Lee DW, Park EC. Association between continuity of care and type 2 diabetes development among patients with thyroid disorder. Medicine (United States) 2019;98. [CrossRef]

- Chen RH, Chen HY, Man KM, Chen SJ, Chen W, Liu PL, et al. Thyroid diseases increased the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A nation-wide cohort study. Medicine (United States) 2019;98. [CrossRef]

- Jun JE, Jee JH, Bae JC, Jin SM, Hur KY, Lee MK, et al. Association between Changes in Thyroid Hormones and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Seven-Year Longitudinal Study. Thyroid 2017;27:29–38. [CrossRef]

| First Author, Title | T2DM Participants |

Hypothyroidism (Subclinical + Overt) |

Hyperthyroidism (Subclinical + Overt) |

| Khassawneh AH, “Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients: A case-control study”[8] | 998 | 220 (22,04%) |

46 (4,61%) |

| Bukhari S, “Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction amongst patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Pakistan”[9] |

317 |

82 (25,8%) |

35 (11%) |

| Ogbonna SU, “Association between glycemic status and thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”[10] | 354 | 44 participants – thyroid dysfunction (12.4 %) |

|

| Shrestha B, “Hypothyroidism among Type 2 Diabetic Patients Visiting Outpatient Department of Internal Medicine of a Tertiary Care Centre: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study”[11] | 384 | 127 (33.07%) |

No data |

| Ishay A, “Prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in women with type 2 diabetes”[12] | 410 (women) |

37 (9%) *just subclinical |

No data |

| Raghuwanshi PK, “Evaluation of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients”[13] | 40 | 10 (25%) |

1 (2,5%) |

| Mehalingam V, “Thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with diabetic complications”[14] | 331 | 46 (13,9%) |

12 (3,6%) |

| Essmat HE, “Thyroid dysfunction prevalence and relation to glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”[15] |

200 | 40 (20%) |

18 (9%) |

| Chubb SAP, “The relationship between thyroid dysfunction, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II”[16] |

1250 | 76 | 3 |

| Subekti I, “Thyroid Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients”[17] | 303 | 23 (7,6%) |

7 (2,3%) |

| Pramanik S, “Thyroid Status in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Eastern India”[18] | 100 | 26 (26%) |

0 (0%) |

| First Author, Title | Publication Year | Type | Key Findings |

| Shrestha B, “Hypothyroidism among Type 2 Diabetic Patients Visiting Outpatient Department of Internal Medicine of a Tertiary Care Centre: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study”[11] |

2023 |

A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study |

A total of 384 subjects with T2DM participated in the study using convenience sampling. Hypothyroidism prevalence was 33.07% (95% CI: 28.36-37.78) among patients, with 56 (44.09%) males and 71 (55.90%) females. Mean age was 55.17±7.53 years. Hypothyroidism prevalence exceeded rates from similar studies in comparable studies [11]. |

| Bukhari S, “Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction amongst patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Pakistan”[9] | 2022 | Descriptive cross-sectional study | TD, especially hypothyroidism, is more common in individuals with T2DM, with a higher prevalence observed in women [9]. |

| Chubb SAP, The relationship between thyroid dysfunction, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II[16] |

2022 | Original article | In the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II, involving 1,250 individuals with T2DM and no prior TD, subclinical hypothyroidism emerged as the most frequent thyroid dysfunction (77.2%). Over a 6.2–6.7 year follow-up, subclinical hypothyroidism was not significantly associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events or mortality (p > 0.05), despite correlations with risk factors such as lower eGFR and higher systolic blood pressure [16] |

| Rong F, “Association between thyroid dysfunction and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies”[22] |

2021 | Research Article | This meta-analysis has demonstrated an association between TD and an elevated risk of developing T2DM. However, the evidence does not support an association between thyroid dysfunction and CVD events or overall mortality in individuals with T2DM. Consequently, measurement of TSH levels in individuals with risk factors for diabetes may assist in the further assessment of T2DM risk [22]. |

| Khassawneh AH, “Prevalence and predictors of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients: A case-control study”[8] | 2020 | Case-Control Study | In patients with T2DM, TD was observed in 26.7% of cases, higher than the 13.7% seen in non-diabetic controls (p < 0.001). Subclinical hypothyroidism was the most prevalent form of pathology. The condition was more likely in individuals over 50 years old (p < 0.001), women (p = 0.013), among those with goiter (p = 0.029) and in patients with poor glycemic control [8]. |

| Mehalingam V, “Thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with diabetic complications”[14] |

2020 | Original article | The prevalence TD among 331 patients with T2DM was found to be 17.5%. Hypothyroidism was observed in 13.9% of participants, while hyperthyroidism was noted in 3.6%. Thyroid dysfunction was more prevalent among female patients. The study did not find a significant association between TD and diabetic complications such as nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, or cardiovascular disease (p > 0.05)[14] |

| Ogbonna SU, “Association between glycemic status and thyroid dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”[10] |

2019 | Original Research | In this study, the mean HbA1c was significantly higher in T2DM patients with TD compared to those without (8.1 ± 1.9% vs 5.1 ± 1.2%, p = 0.001). Additionally, a positive linear relationship was observed between HbA1c levels and the presence of TD (regression coefficient = 1.89, p = 0.001). It suggests that poor glycemic control may be associated with an increased risk of TD in individuals with T2DM [10]. |

| Zuanna TD, “A Systematic Review of Case-Identification Algorithms Based on Italian Healthcare Administrative Databases for Two Relevant Diseases of the Endocrine System: Diabetes Mellitus and Thyroid Disorders”[86] |

2019 | Systematic Review | This systematic review examined algorithms for identifying cases of DM and TD using Italian healthcare administrative databases. The authors concluded that while numerous algorithms exist for identifying DM using healthcare administrative databases, the literature on TDs is relatively sparse, and further validation and implementation of these algorithms are needed. [86]. |

| Elgazar EH, “Thyroid dysfunction prevalence and relation to glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus”[15] |

2019 | cross-sectional study | A cross-sectional study of 200 T2DM patients and 200 controls found significantly elevated TSH and T3 levels in diabetics (P < 0.001). Thyroid dysfunction was more common in those with poor glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 8%) and longer diabetes duration. Subclinical hypothyroidism was the most frequent thyroid disorder observed [15]. |

| Chen RH, “Thyroid diseases increased the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus A nation-wide cohort study”[88] |

2019 | Research Article | In a nationwide cohort study, patients with TD had higher cumulative incidence T2DM compared to the control group, with a log-rank p-value < 0.0001. The development between TD and T2DM was strongest within the first year after TD diagnosis. Female patients and those aged 18–64 years exhibited higher incidence of T2DM compared to controls (p < 0.0001) [88]. |

| Pramanik S, “Thyroid Status in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Eastern India”[18] |

2018 | Original article | In this study of 100 diabetes patients, thyroid function was assessed. Subclinical hypothyroidism was found in 23% of patients, overt hypothyroidism in 3%, and positive thyroid autoantibodies in 13.1%. All patients were iodine sufficient. About one in four diabetes patients had TD. Routine thyroid screening is recommended. The success of the salt iodination program in this region is noted[18]. |

| Alsolami AA, “Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism: a case–control study”[51] |

2018 | A case-control study | It analyzed 121 cases and 121 controls. The study found higher risk rates of hypothyroidism in patients with T2DM. Multivariate analysis revealed a stronger association between T2DM and hypothyroidism, with an odds ratio (OR) of 4.14 (P<0.001). The results suggest that T2DM patients are at an elevated risk for developing hypothyroidism. Improved management of T2DM may help mitigate this risk [51]. |

| Jun JE, “Association between changes in thyroid hormones and incident type 2 diabetes: A seven-year longitudinal study”[89] | 2017 | Research Article | In a cohort of 6,235 euthyroid individuals without DM, monitored annually between 2006 and 2012, variations in TH levels were evaluated in relation to incident T2DM. Over 25,692 person-years of follow-up, 229 new T2DM cases were identified. After adjusting for confounders, individuals in the highest tertile of TSH change (2.5–4.2 μIU/mL) demonstrated an increased risk of developing T2DM (p for trend=0.027) compared to those with smaller TSH changes. Notably, baseline TH levels were not predictive of diabetes risk. These findings indicate that even subtle changes in thyroid function, within the normal range, can influence the risk of developing T2DM [89]. |

| Raghuwanshi PK,“Evaluation of thyroid dysfunction among type 2 diabetic patients”[13] |

2014 | Original Article | In a cohort of 80 subjects, TD was significantly more prevalent in T2DM patients than in controls (p < 0.05). Hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism were observed in 10% and 15% of diabetic patients, respectively, compared to 2.5% and 7.5% in non-diabetic individuals [13]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).