Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

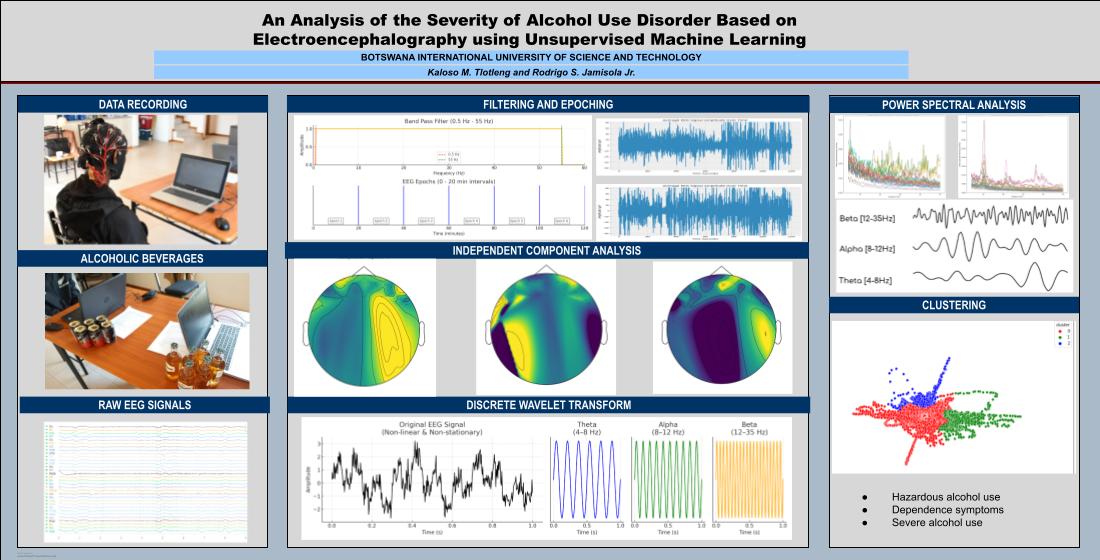

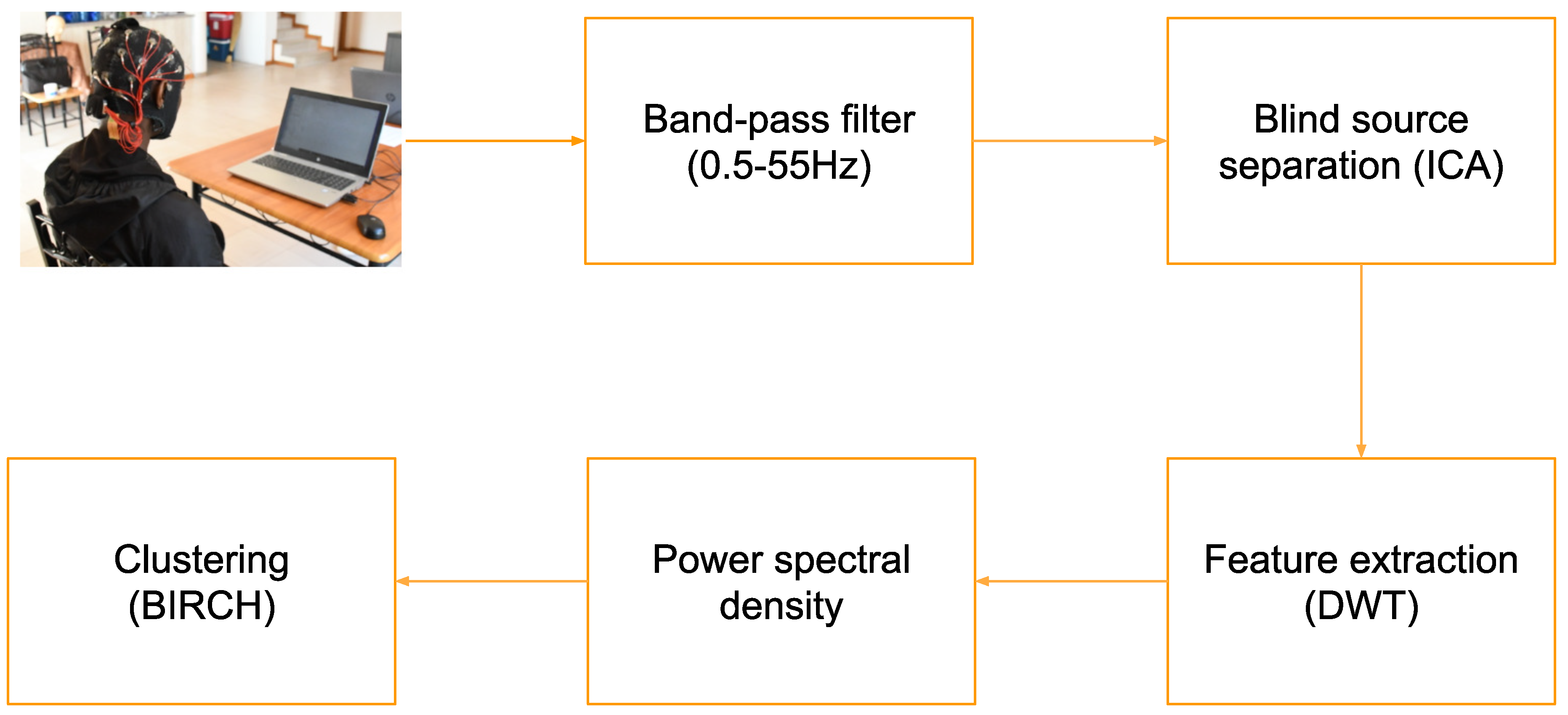

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Gathering with Participants

- Have you ever consumed 2 liters of 6% alcohol or more in two hours?

- Do you have any alcohol allergies?

- Have you ever had a bad reaction to alcohol?

- Do you suffer from any liver disease?

- Do you suffer from diabetes?

- Do you have any history of diabetes?

- Do you suffer from kidney disease?

- Do you have any history of kidney disease?

- Have you ever been diagnosed with Alcohol dehydrogenase deficiency?

2.1.1. Self Assessment

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Importing Raw Data

2.2.2. Filtering

2.2.3. Epoching

2.2.4. ICA

2.2.5. Discrete Wavelet Transform

2.3. Data Presentation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Power Spectral Density Analysis

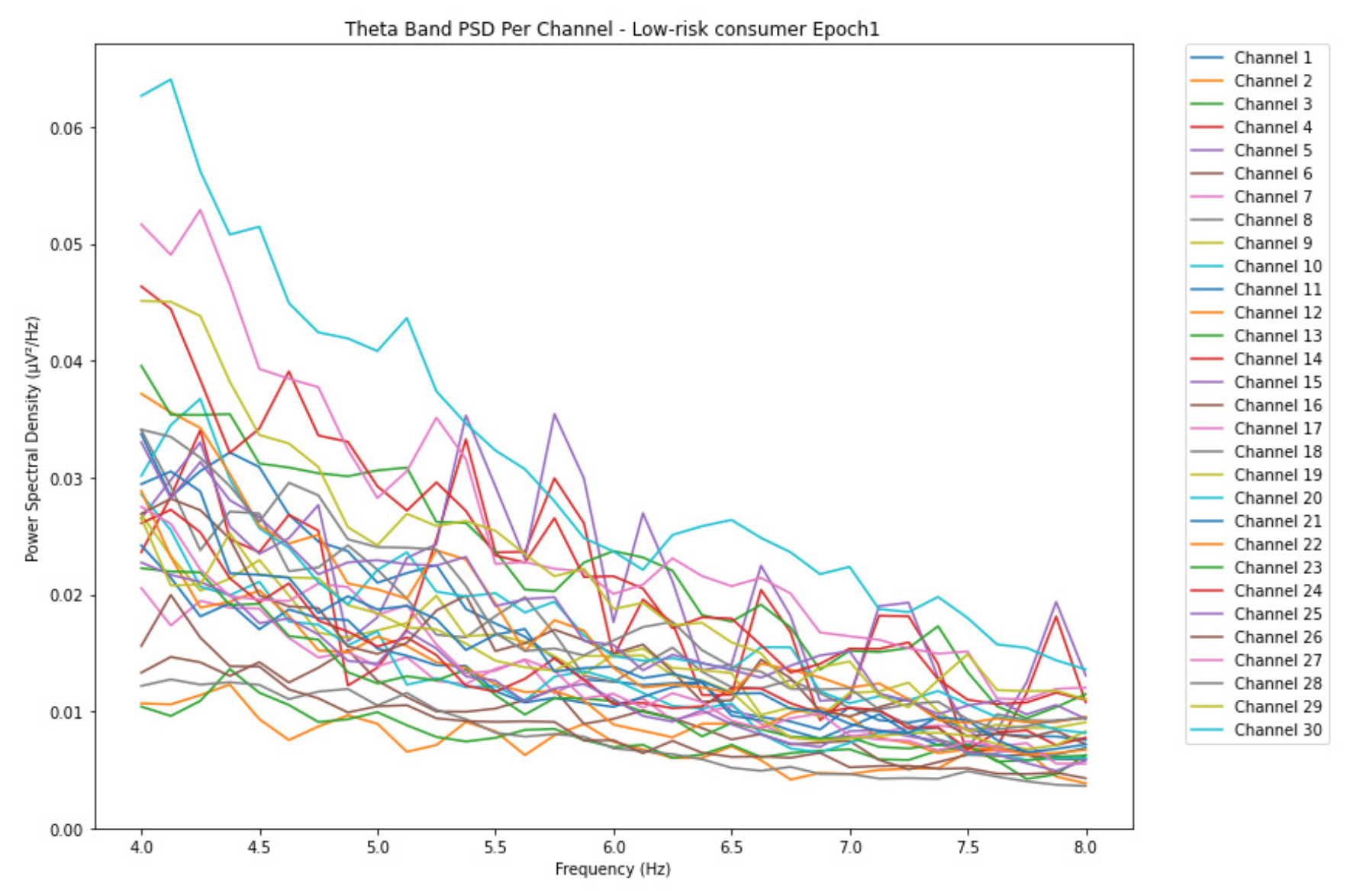

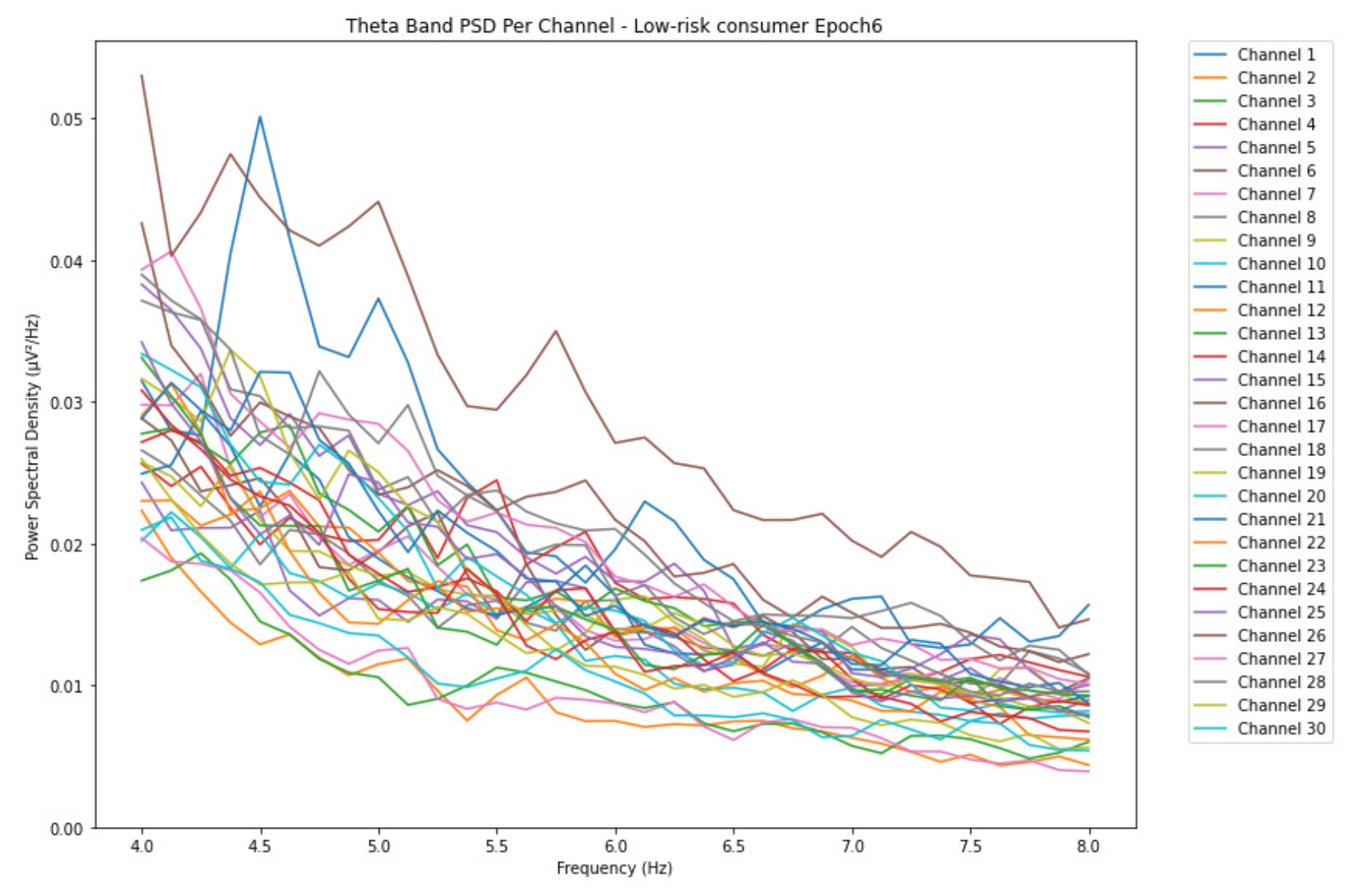

3.1.1. Theta Band

-

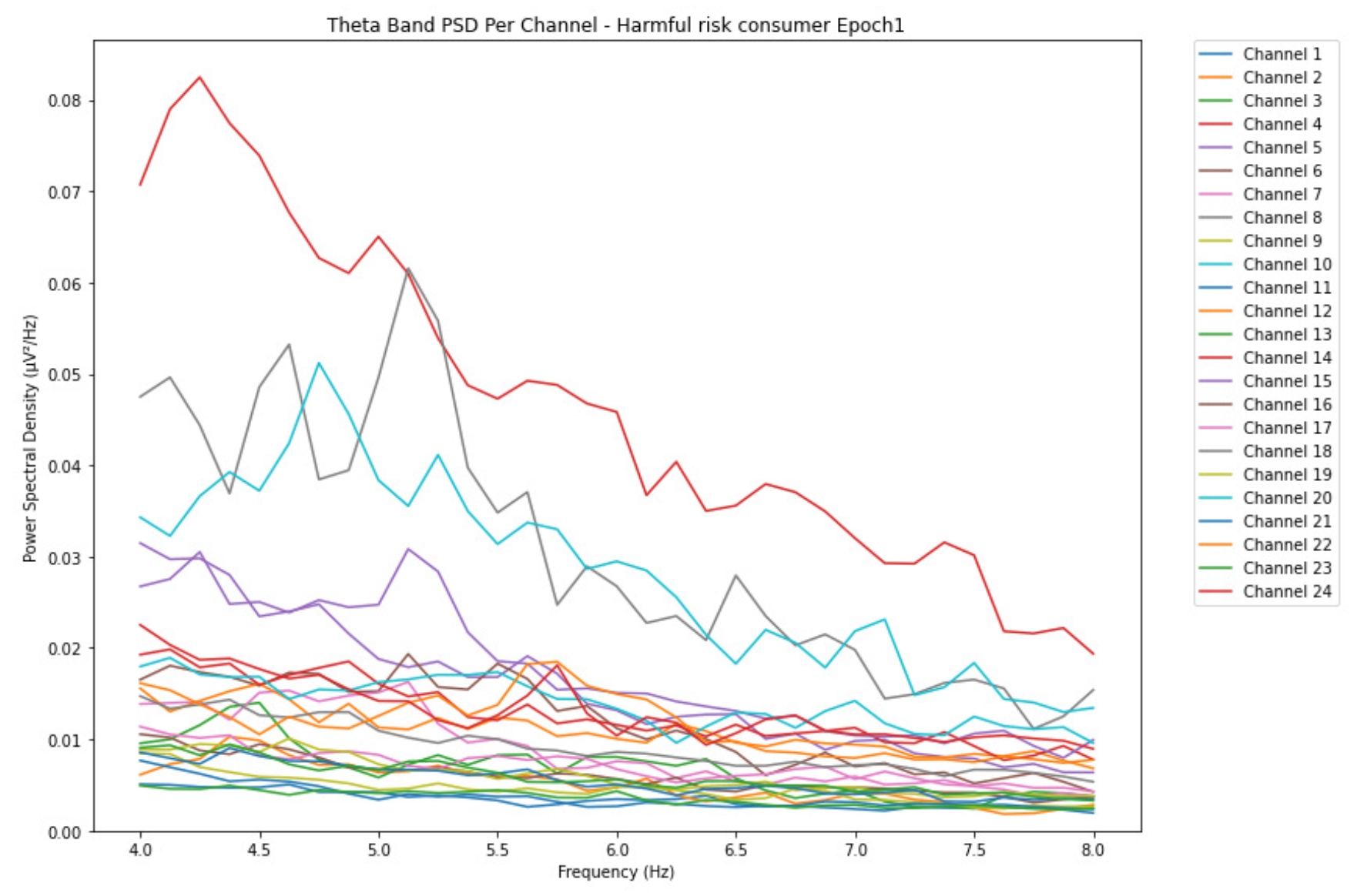

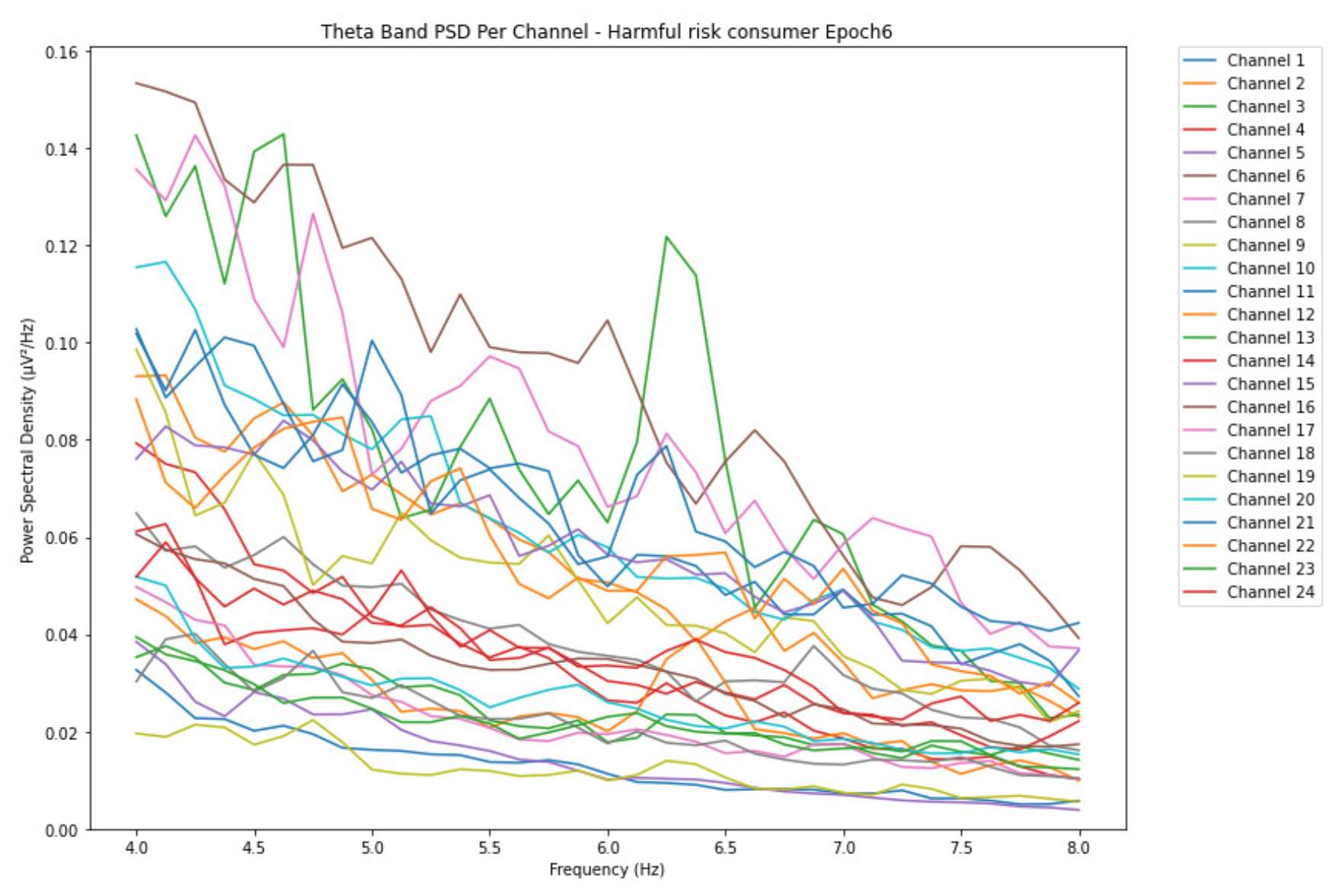

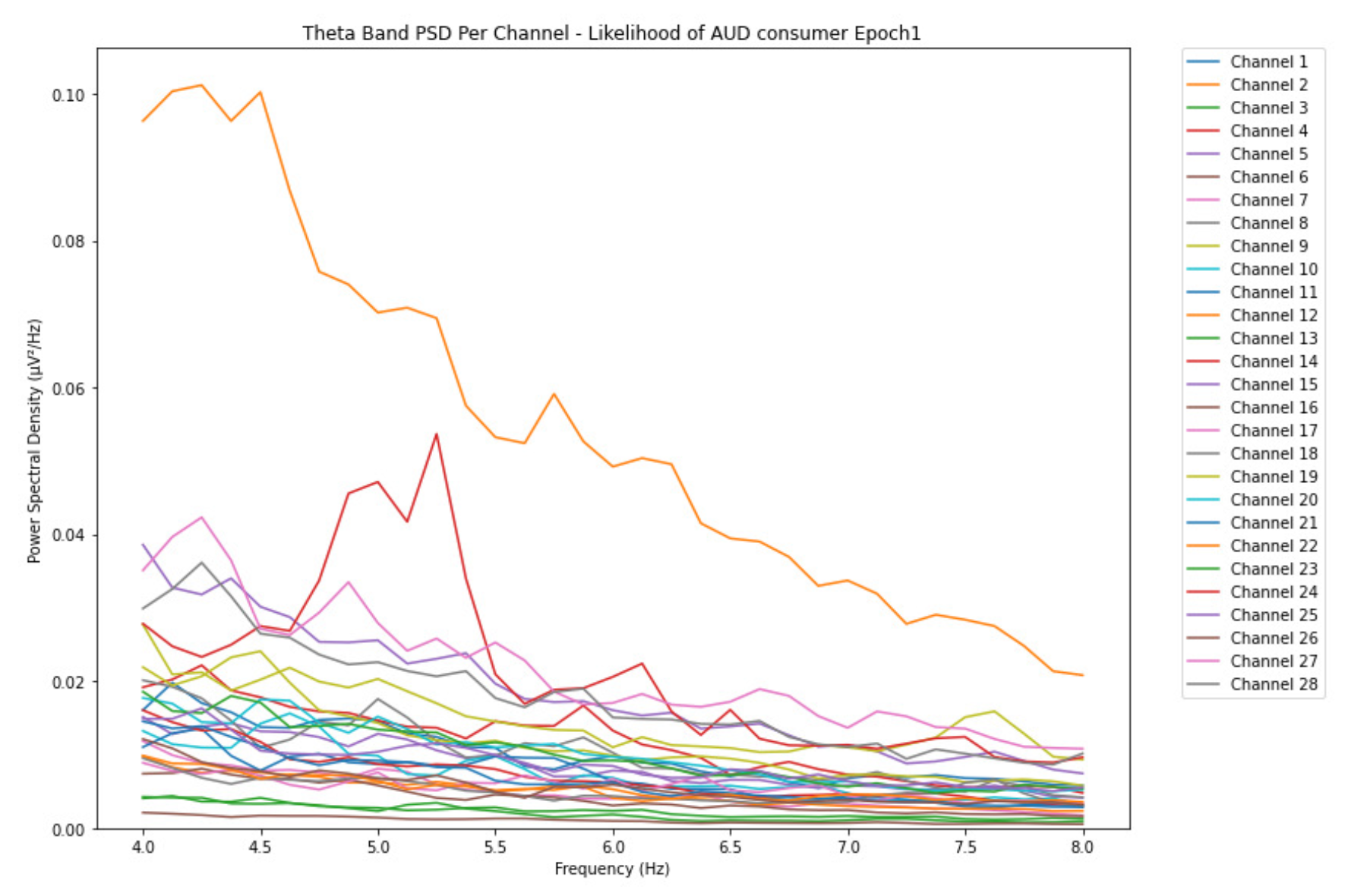

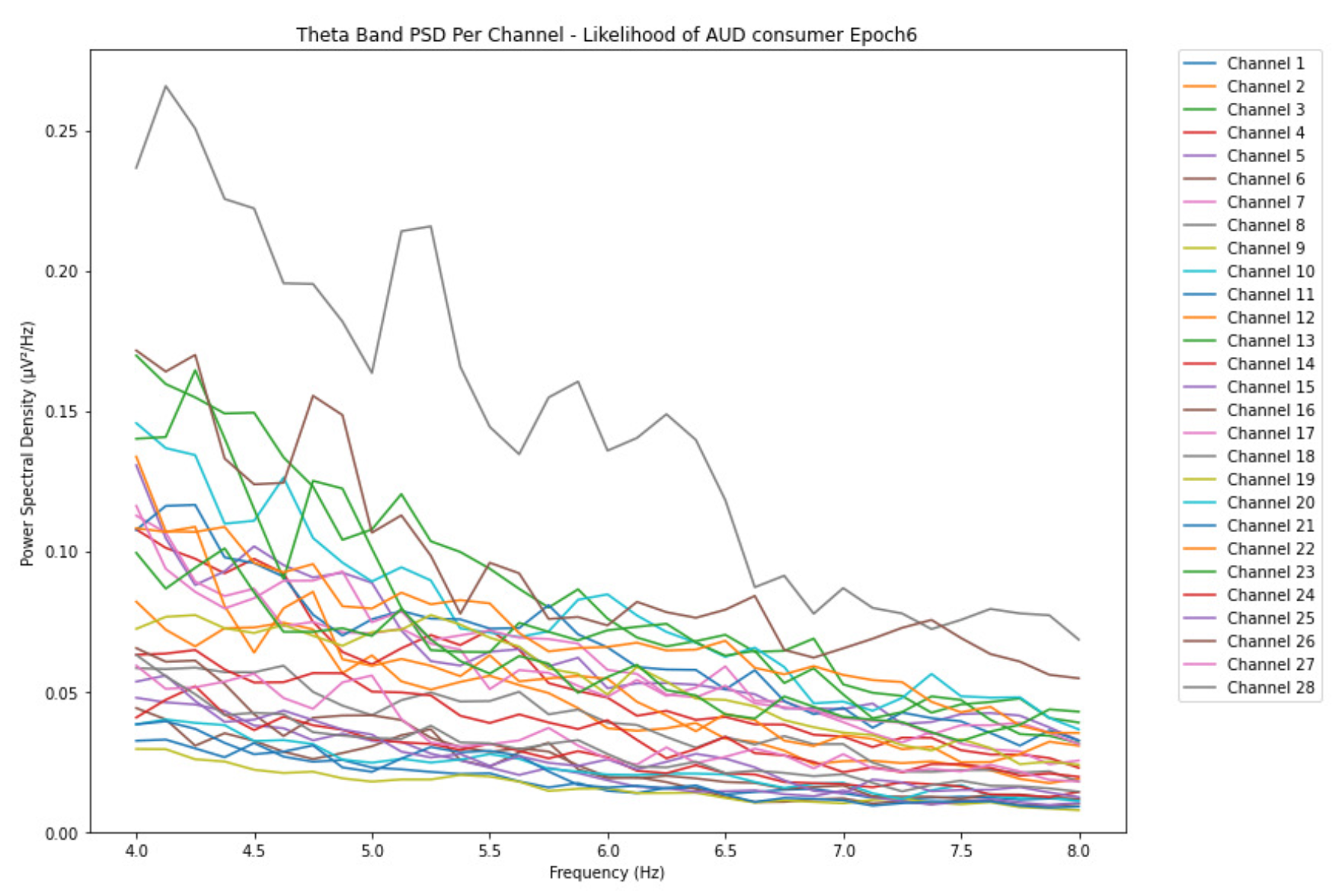

ObservationsWe can observe the PSD of a low-risk consumer ranging from 0.005 to 0.065 V²/Hz in Figure 2 and from 0.005 to 0.055 V²/Hz in Figure 3. We can also observe the PSD of the harmful or hazardous consumer ranging from 0.005 to 0.09 V²/Hz in Figure 4 and from 0.005 to 0.15 V²/Hz in Figure 5. Finally, we can observe the PSD of a participant with the likelihood of AUD ranging from 0.00 to 0.10 V²/Hz in Figure 6 and from 0.001 to 0.28 V²/Hz in Figure 7. The participant with low-risk consumption has a higher degree of signal entanglement in epoch 1, followed by the one with harmful or hazardous consumption, and lastly, the subject with the likelihood of AUD. On the contrary, in epoch 6, we can observe a higher degree of signal entanglement for harmful consumer, followed by the one with low-risk consumption, and lastly, the subject with the likelihood of AUD. Based on these results, during the first phase of alcohol intake, the participant with the likelihood of AUD has the highest range of theta power, followed by the harmful consumer, and lastly, the low-risk consumer. Similarly, during the last phase of alcohol intake, the subject with the likelihood of AUD has the highest range of theta power, followed by harmful or hazardous consumer and lastly low-risk consumer.

-

InterpretationsIn general, for the theta band, more alcohol consumption results in more spectral power. This is true for all types of alcohol consumption. However, for people with a lesser frequency of consumption, the level of activation is much higher compared to the highest frequency of consumption. For the data gathered in this experiment, the highest frequency of consumption has five times more spectral power than the lowest frequency of consumption. This means that people with higher alcohol consumption are more coherent in their level of concentration thus, they tend to be more functional in performing normal tasks compared to those with less consumption. The high degree of signal entanglement results from the activation of inhibitory and motor responses caused by alcohol consumption as these are regulated by the theta band [33]. The level of activation is much higher for people with a lesser frequency of use because they project more acute performance impairment symptoms due to higher alcohol consumption. In most people, mild intoxication can be observed after two standard drinks [42].

3.1.2. Alpha Band

-

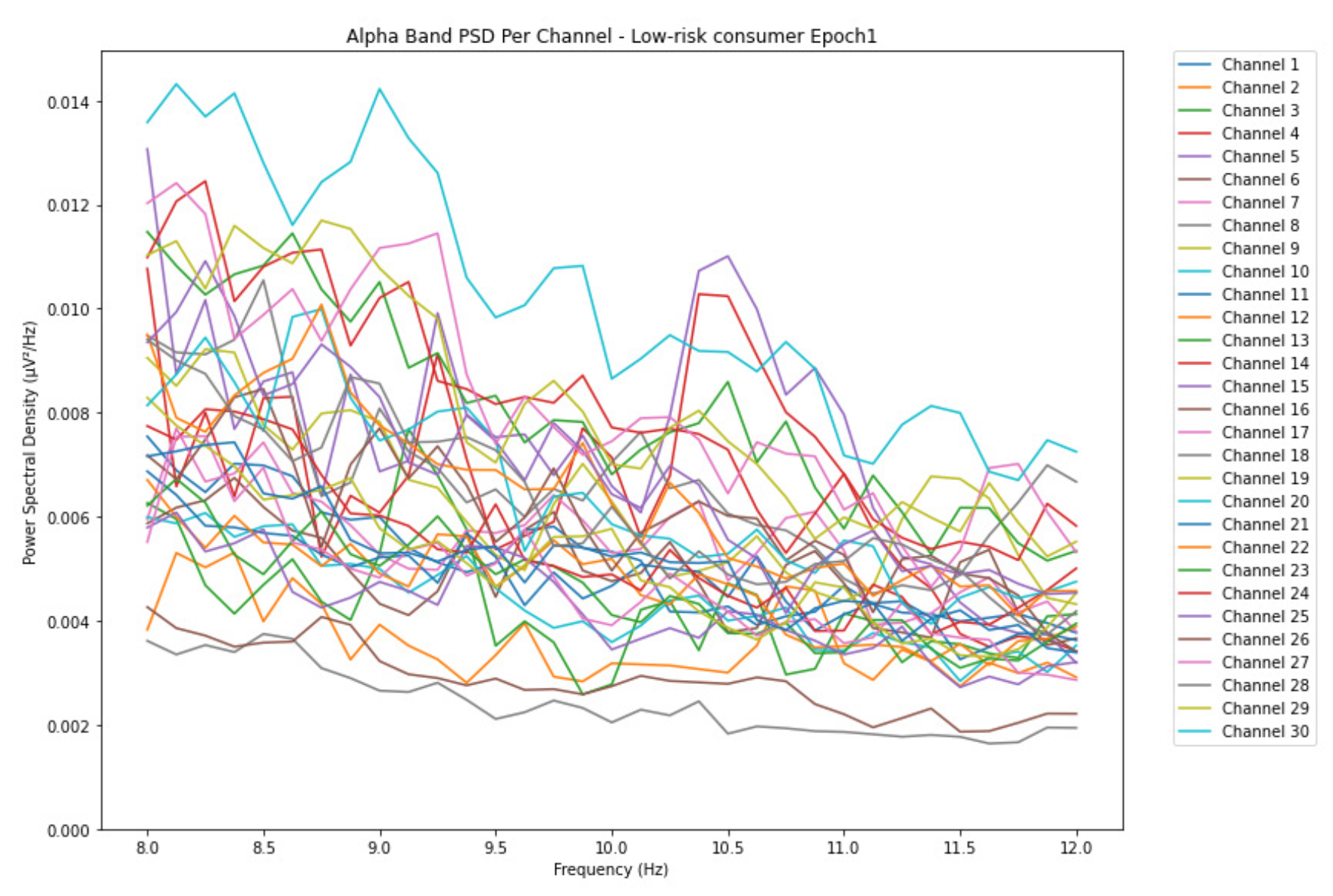

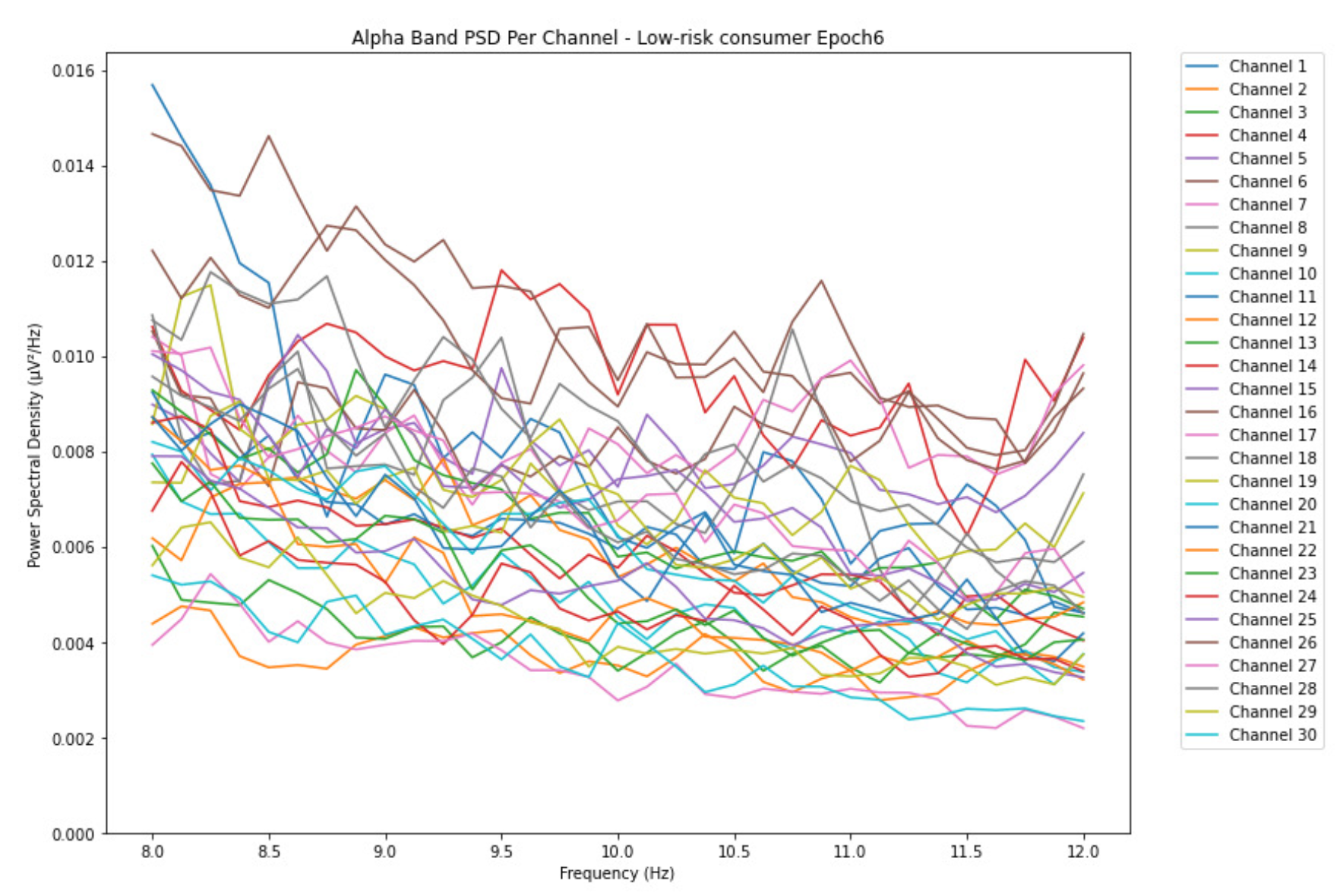

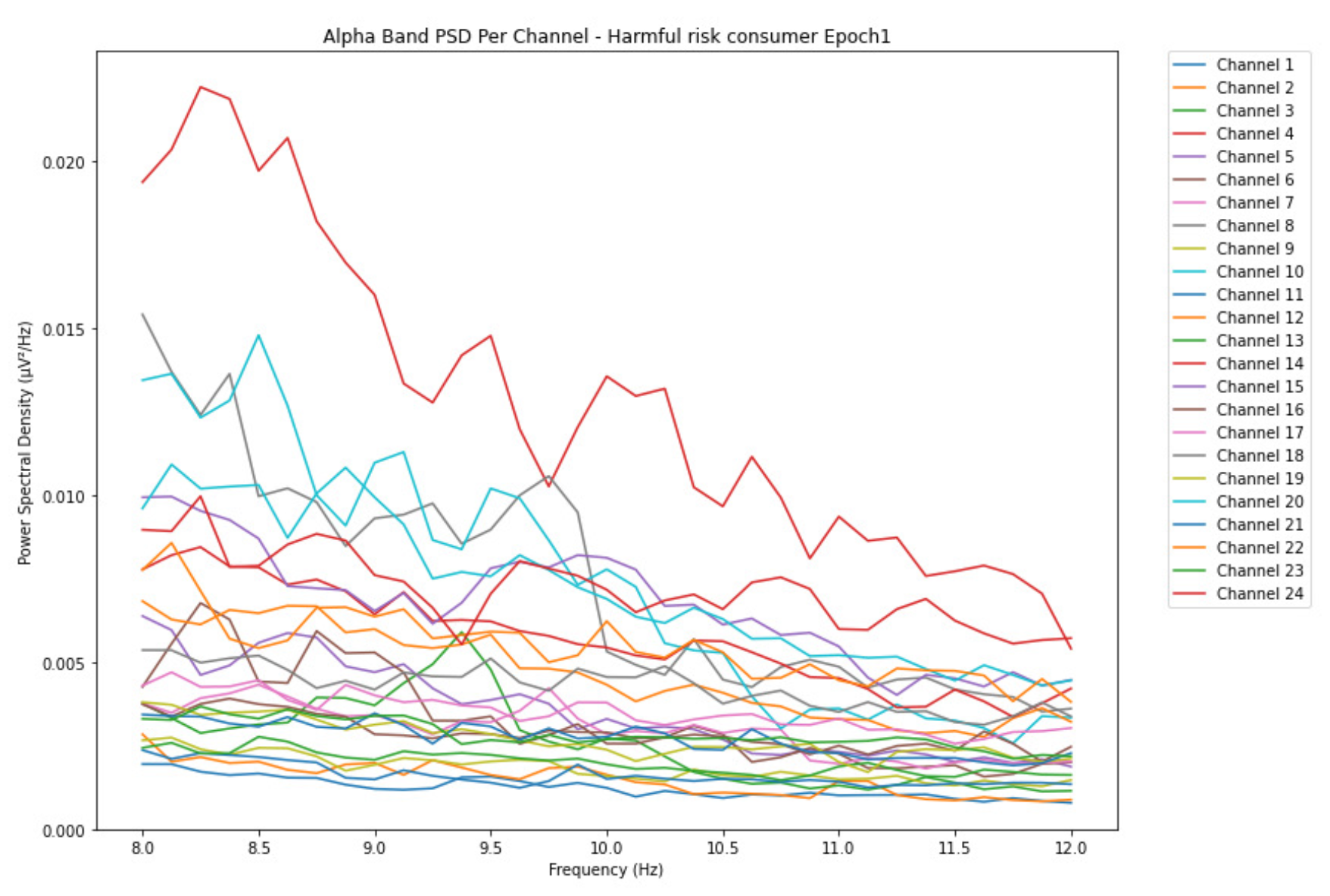

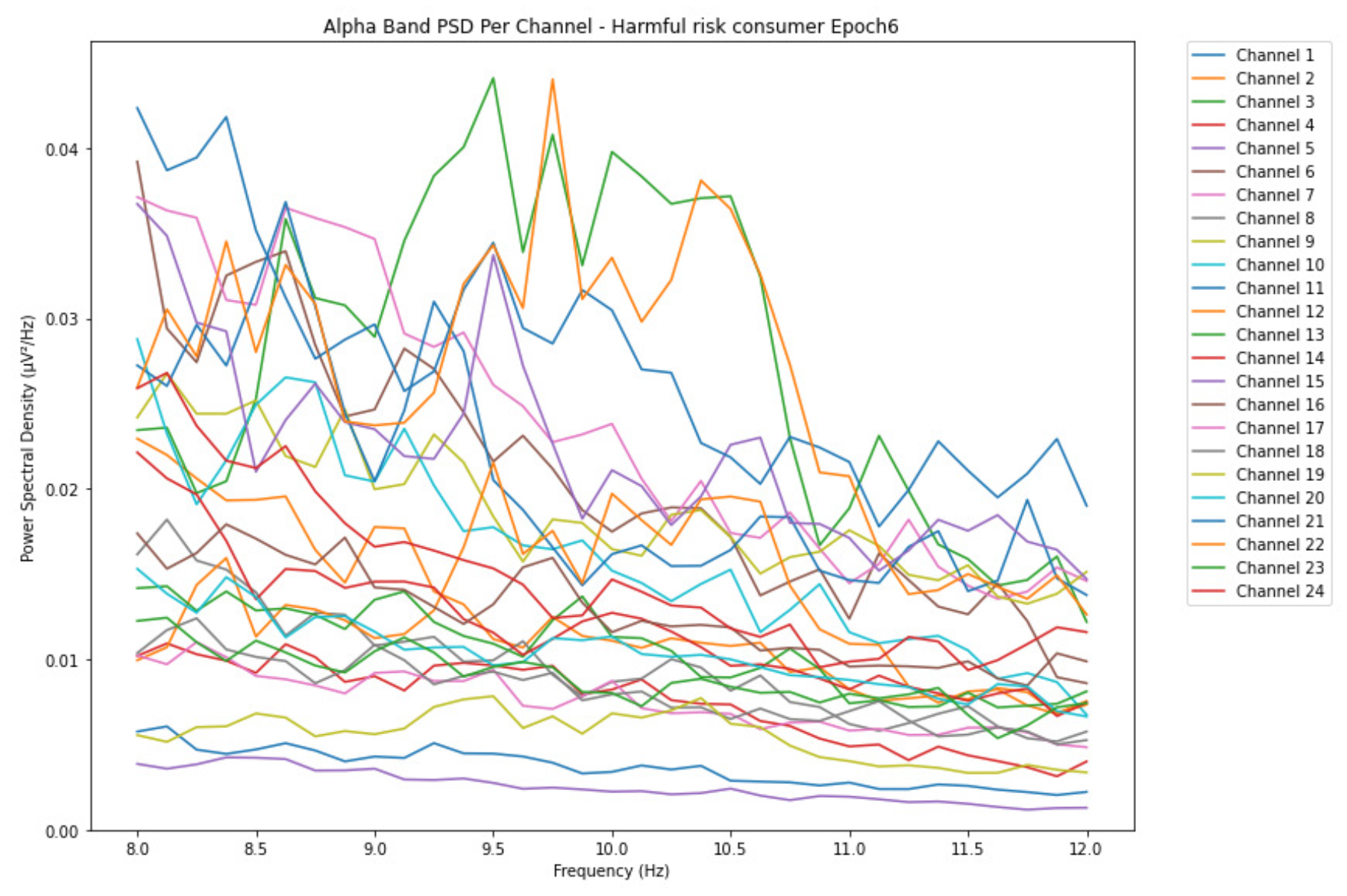

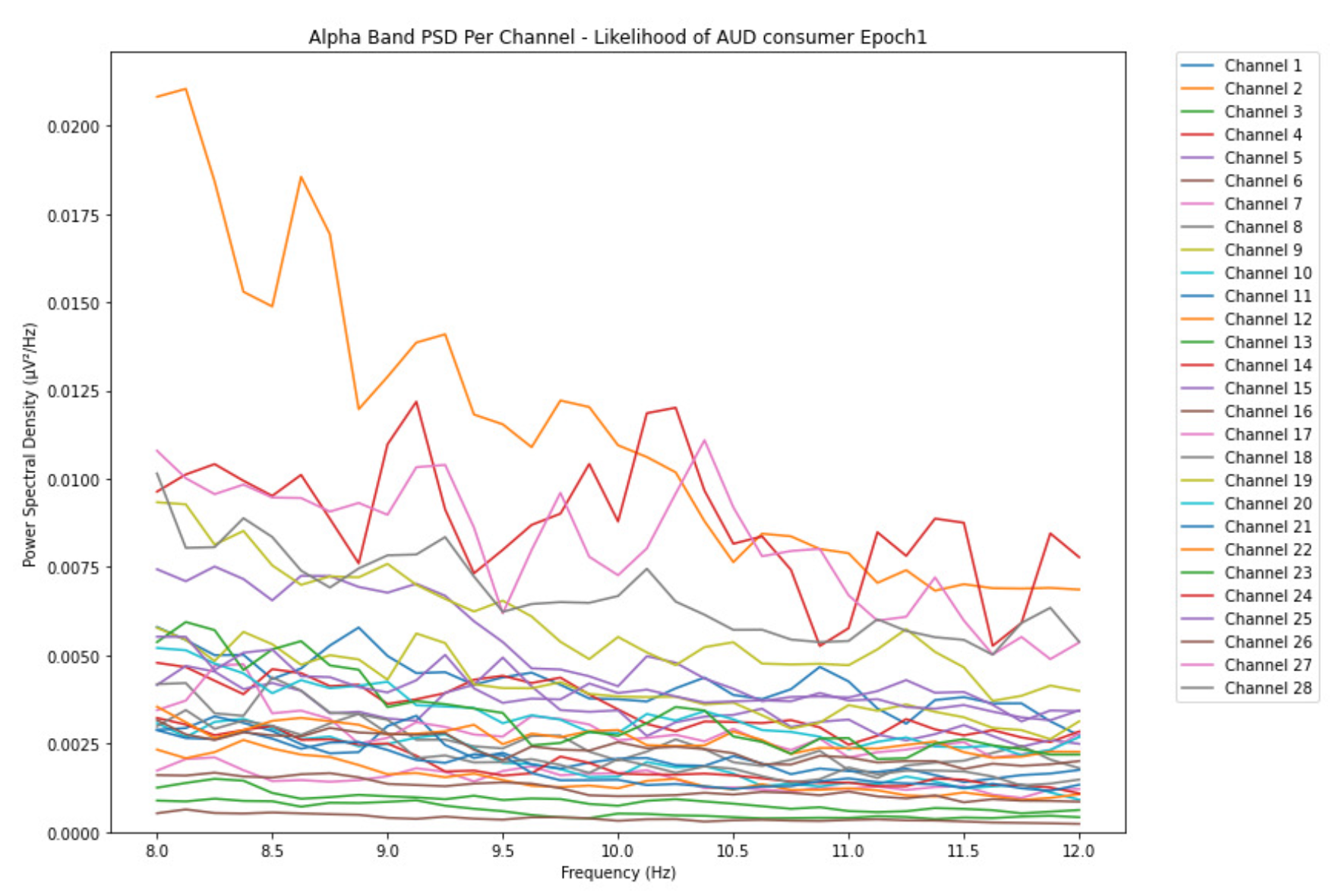

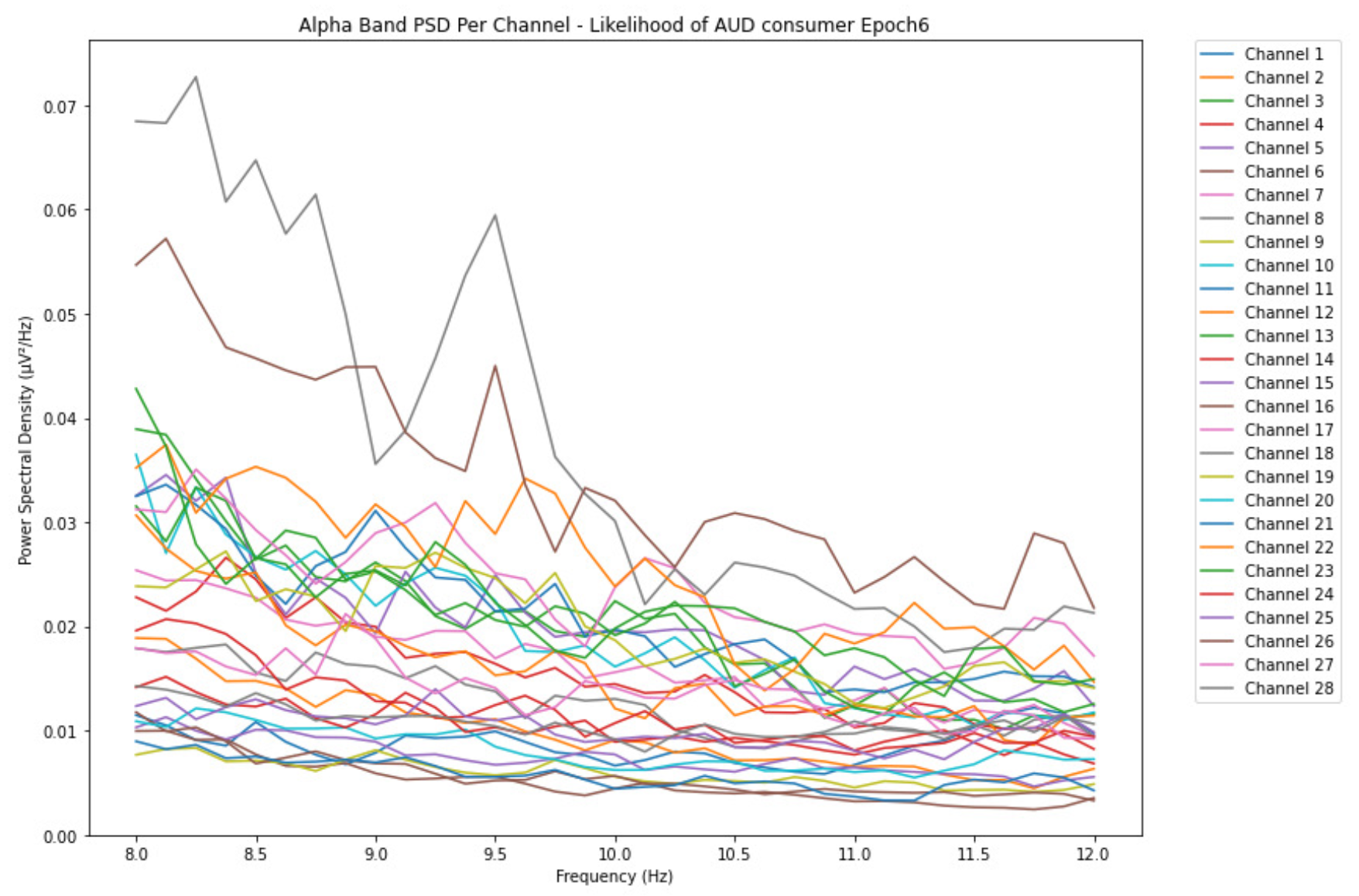

ObservationsCompared to the results of the theta band, we can observe some significant decrease of alpha in the range of the PSD for all the subjects in all the epochs. Although the results of the alpha band are lesser than theta, there is an increase in the average PSD between epochs 1 and 6 for all three types of consumption. We can observe the PSD of low-risk consumer ranging from 0.002 to 0.014 V²/Hz in Figure 8 and from 0.002 to 0.0158 V²/Hz in Figure 9. The PSD for harmful or hazardous consumer in Figure 10 ranges from 0.002 to 0.024 V²/Hz and from 0.005 to 0.48 V²/Hz in Figure 11. Lastly, the PSD for an individual with the likelihood of AUD in Figure 12 ranges from approximately 0.000 to 0.0225 V²/Hz in epoch 1 and from 0.005 to 0.075 V²/Hz in Figure 13. Similar to the theta band, we can observe a higher degree of signal entanglement for the subject with low-risk consumption, followed by the harmful or hazardous consumer, and lastly for the subject with the likelihood of AUD in epoch 1. For epoch 6, we can observe a higher degree of signal entanglement in the subject with harmful or hazardous consumption, followed by the low-risk consumer, and lastly, one with the likelihood of AUD.

-

InterpretationsIn the alpha, the same trend of activation is observed as in the theta band. However, the value of the spectral power is lesser because it is mostly suppressed during body activities with eyes wide open. A higher alpha power is more prominent at the resting state, and thus, more alcohol consumption results in less relaxation and more agitation [35]. People with lesser alcohol consumption can be easily disturbed by outside stimuli compared with people with higher consumption, as they can be calmer. Increasing the amount of alcohol consumption results in cortical activations and alert mechanisms and thus causes less relaxation [43].

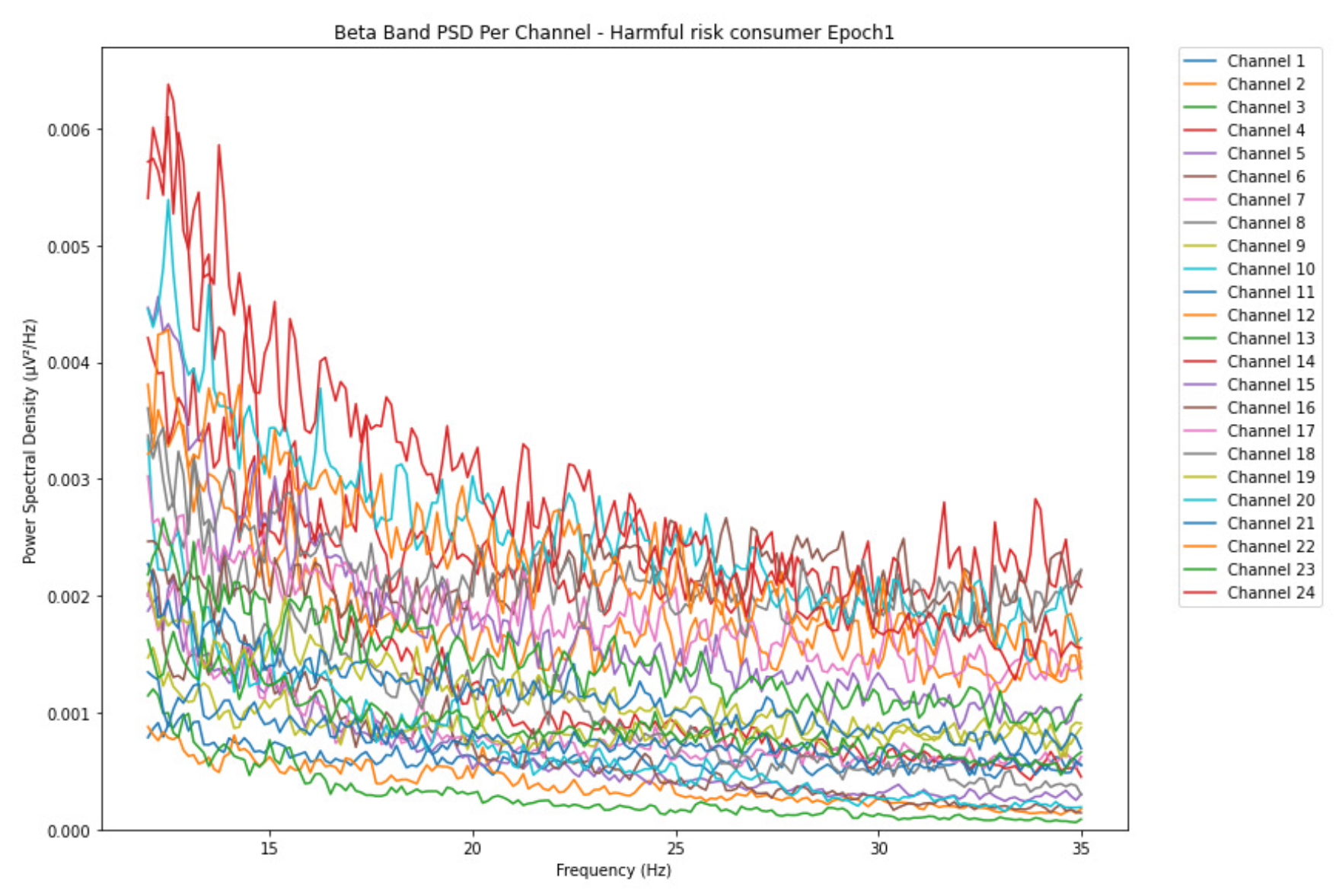

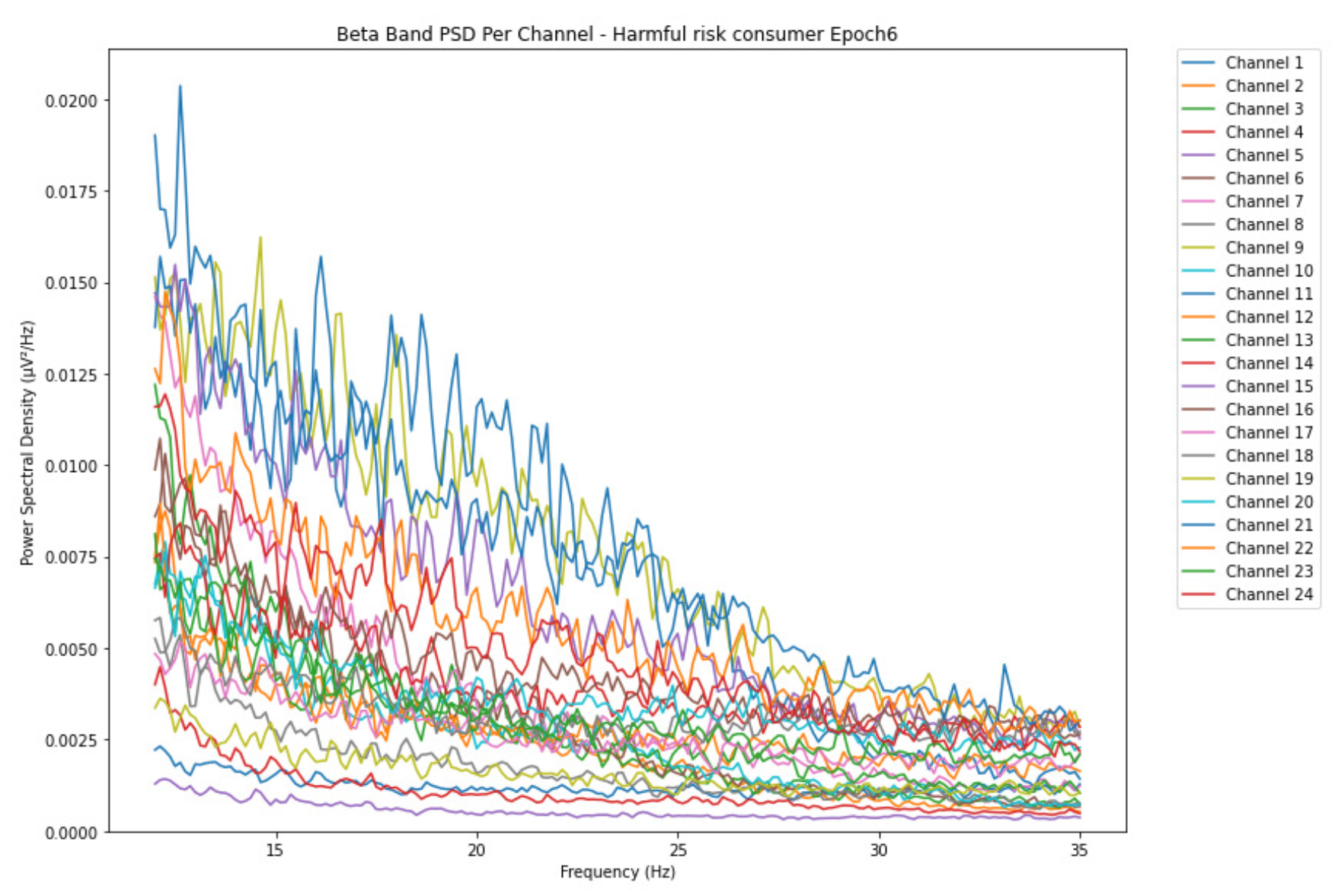

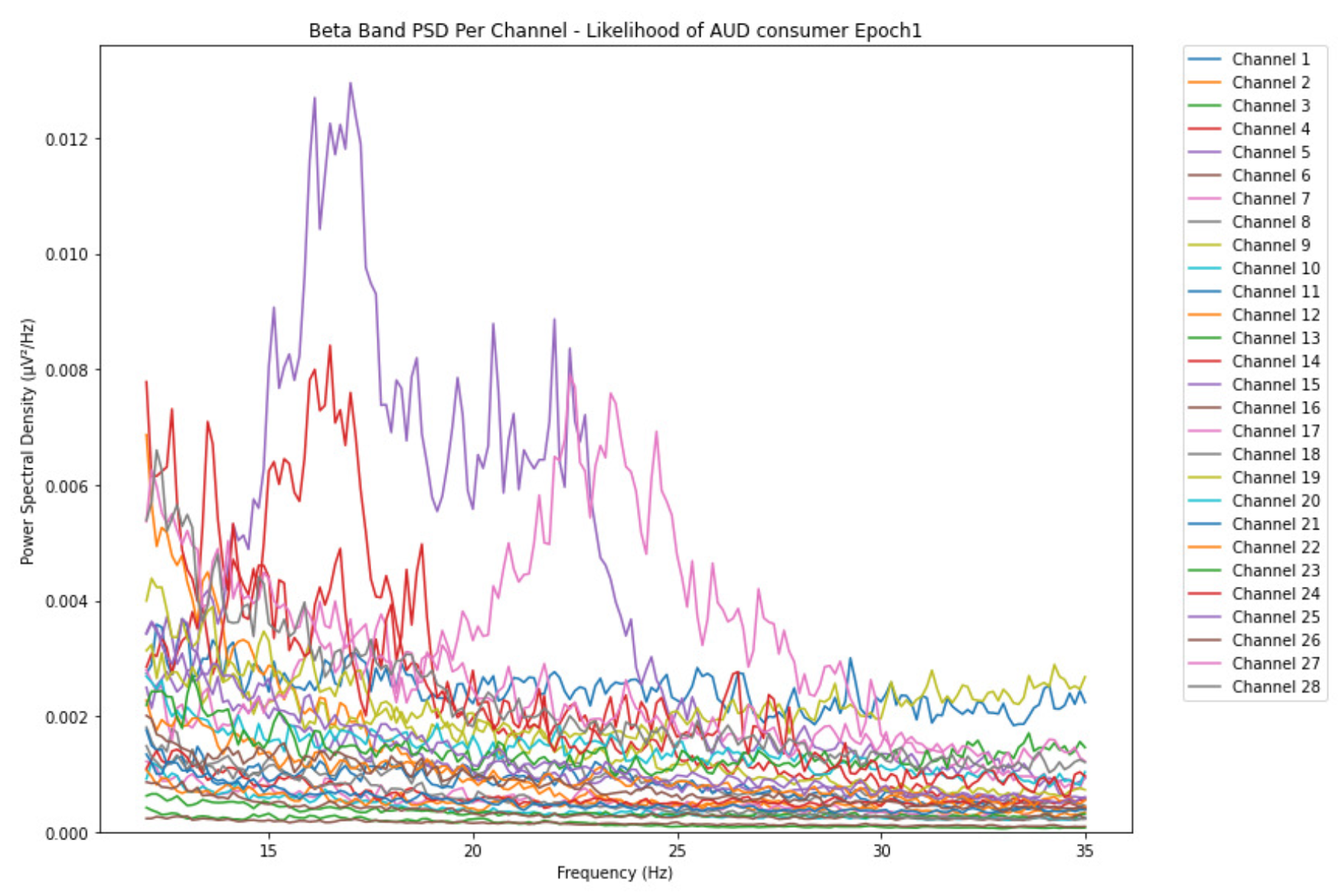

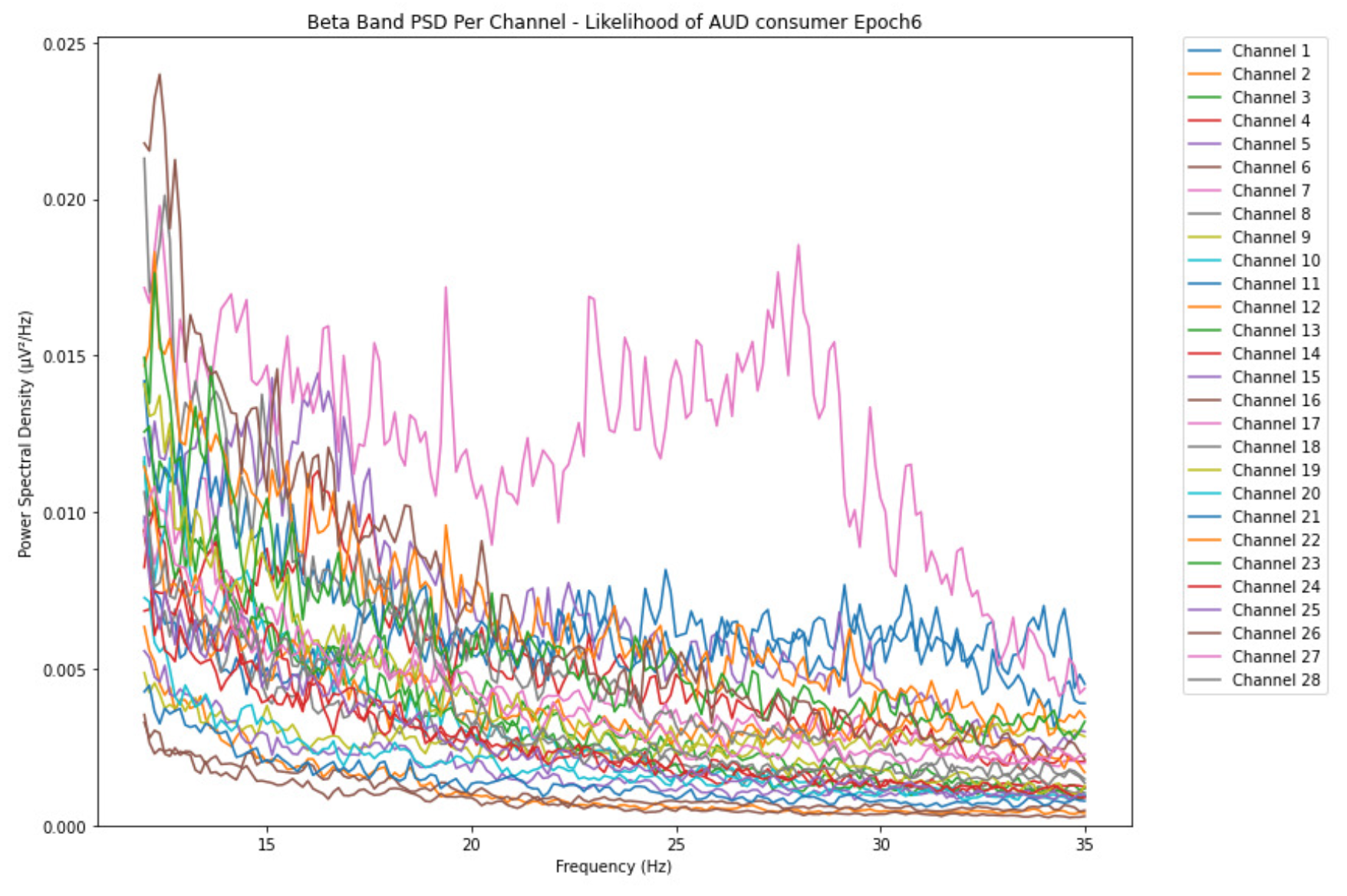

3.1.3. Beta Band

-

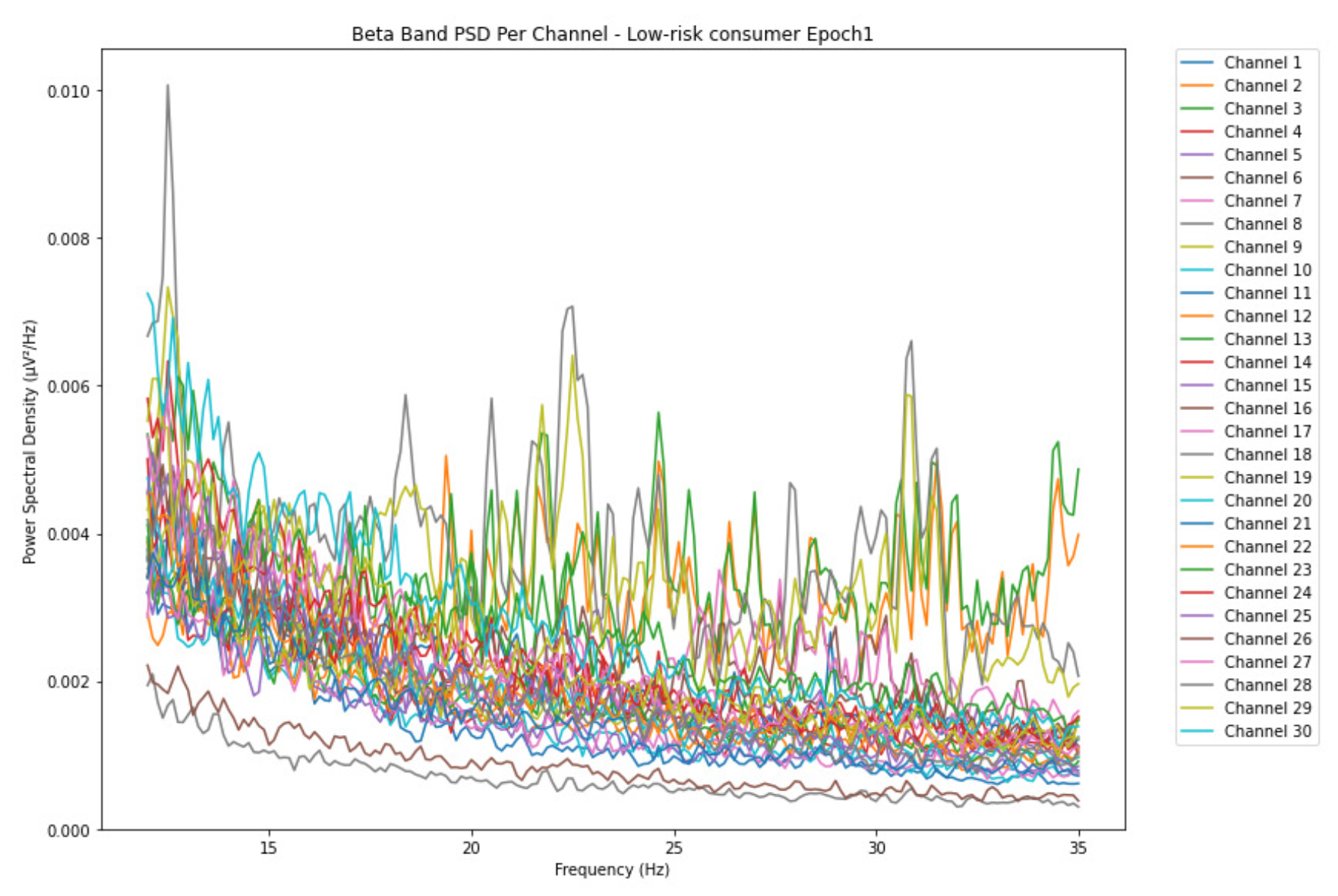

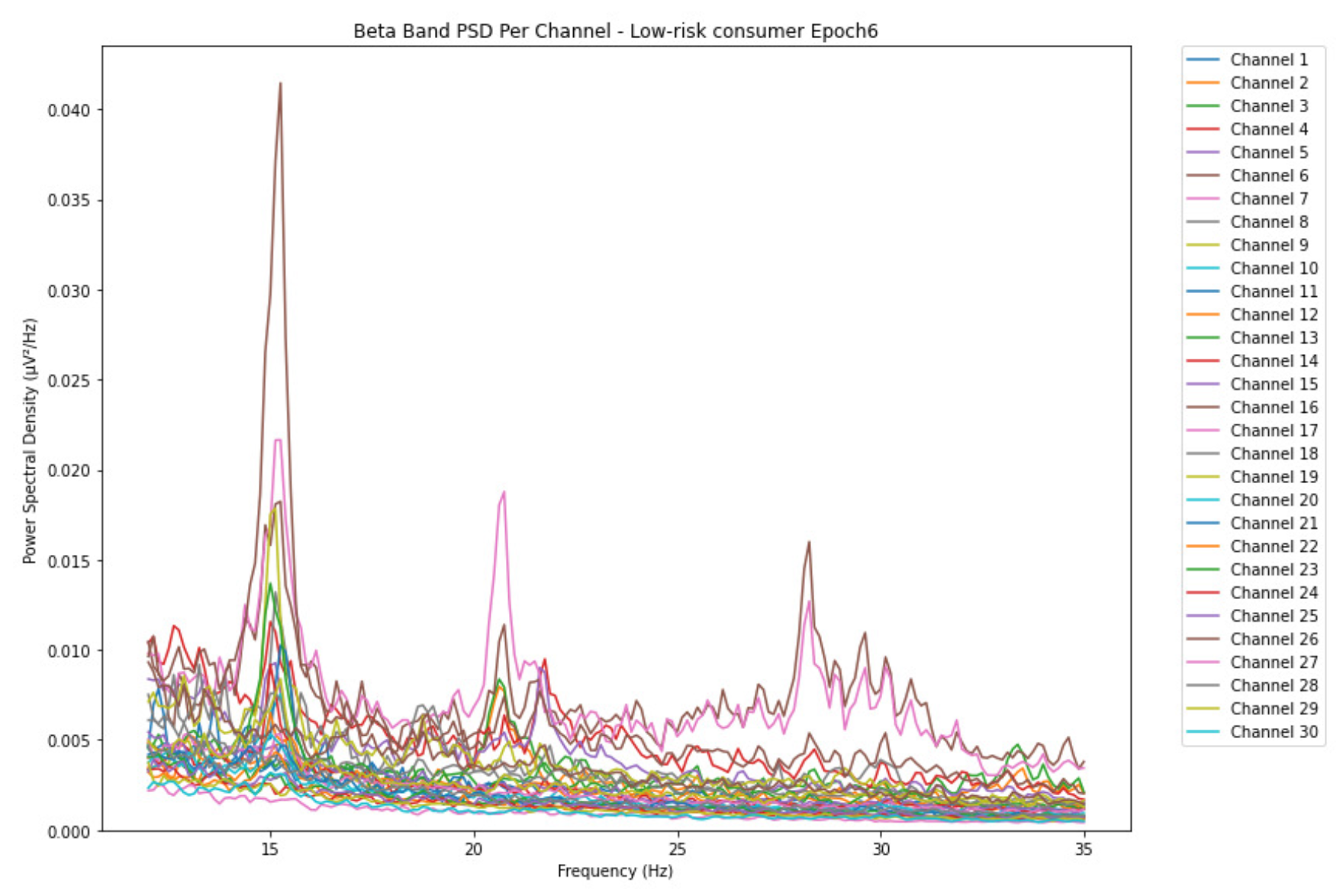

ObservationsThe PSD of low-risk consumer ranges from 0.0005 to 0.01 V²/Hz in Figure 14 and from 0.000 to 0.045 V²/Hz in Figure 15. For harmful or hazardous consumer in Figure 16, the PSD ranges from approximately 0.000 to 0.0065 V²/Hz and approximately 0.000 to 0.02 V²/Hz in Figure 17. Lastly, the PSD for the subject with the likelihood of AUD in Figure 18 ranges from 0.000 to 0.013 V²/Hz and from 0.000 to 0.024 V²/Hz in Figure 19. The signals appear to fluctuate independently, but the degree of signal entanglement is more significant in the low-risk consumer, followed by harmful or hazardous consumer, and lastly, the subject with the likelihood of AUD. We can also observe that some signals have peaks at certain frequencies, with the low-risk consumer having more pronounced peaks, followed by harmful consumer, and lastly, the subject with the likelihood of AUD in epoch 1. In epoch 6 of the low-risk consumer, we can observe a significant peak at 15Hz.

- Interpretations

3.2. Transition-Based Clustering Results

-

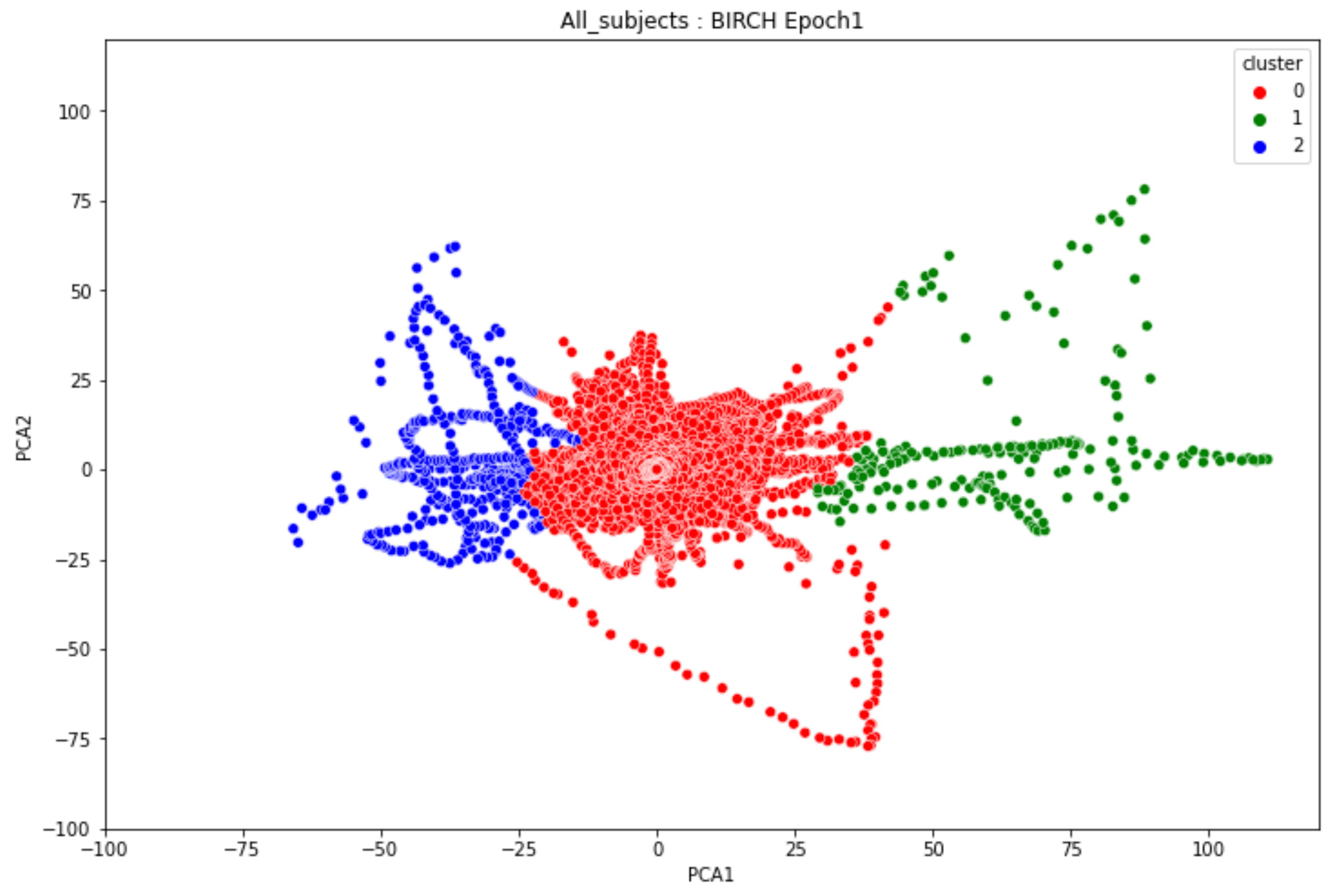

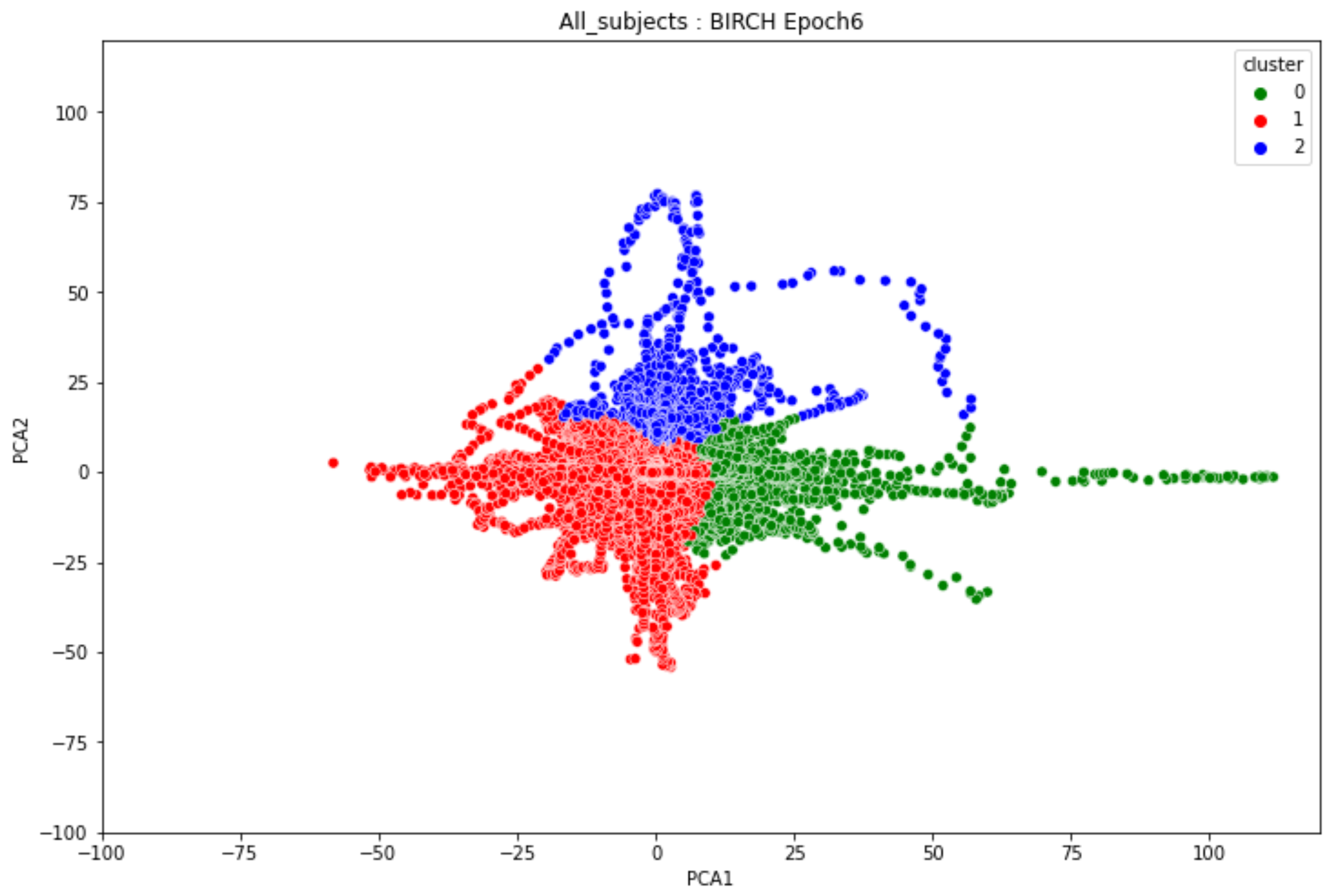

ObservationsIn Figure 20, the clustering results indicate the three major clusters that represent the brain activity of participants at the first instance of alcohol intake. We can observe more dispersed data points for the green cluster, followed by the red cluster, and lastly the red cluster. The red cluster is dense than the blue and green clusters and covers a wider range than the other two. The data points in the red cluster fall between the blue and the green clusters. In Figure 21, we can also observe three major clusters that represent the brain signals of participants at the last instance of alcohol intake. Compared to the epoch 1 cluster results, the data points are more confined and less dispersed. We can also observe that the data points in the blue and green clusters intersect towards the larger values of the PCA1 axis. Similarly, some data points in the green cluster overshoot towards the larger values of the PCA1 axis.

-

InterpretationsThe three major clusters in Figure 20 and Figure 21 represent the brain activity of people with low-risk alcohol consumption, hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption, and the likelihood of AUD. The blue cluster in Figure 20 represent the brain activity of people with the likelihood of AUD, the red cluster represents those with harmful or hazardous consumption and lastly, the green cluster represents those with low-risk consumption. The dispersion of the data points in Figure 20 indicates the neurophysiological changes and the brain activation induced by alcohol consumption. In addition, individuals experience more brain activation and a higher degree of signal entanglement for lesser alcohol consumption compared to higher alcohol consumption. The brain activity of people with low-risk consumption and the likelihood of AUD in Figure 21 intersect because according to [46], these consumers may project similar characteristics during binge drinking. The data overshoot in Figure 21 of the green cluster indicates the higher spectral power that is mostly associated with the activation of the inhibitory and motor responses caused by increasing amounts of alcohol for individuals with low consumption. An increase in alcohol consumption causes an increase in the cause an increase in the spectral power of the theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands. Lastly, the brain activity of people who have moderate to high alcohol consumption projects less motor control impairment compared to those with low-risk consumption [46] and thus are calmer for the same amount of alcohol consumption.

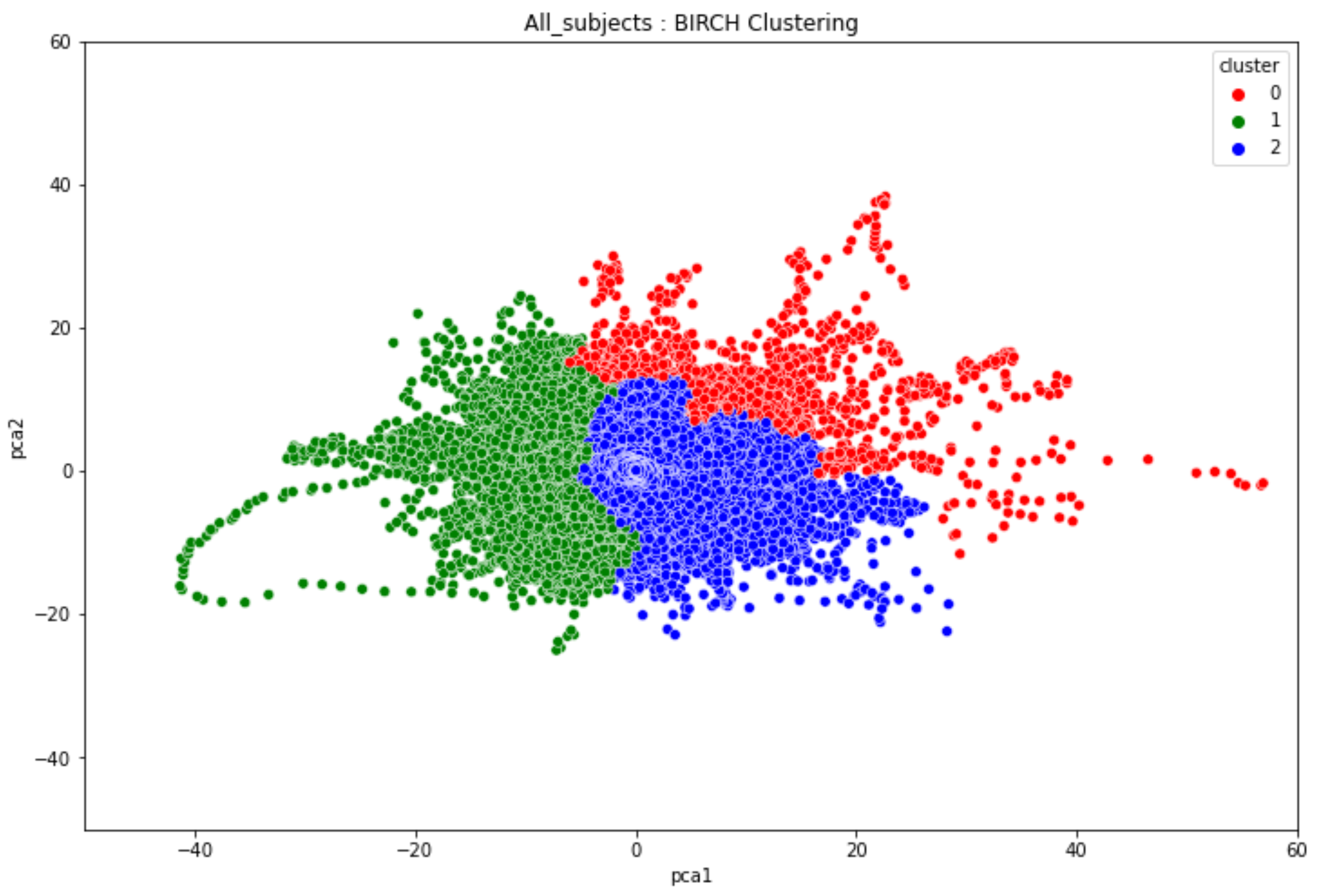

3.3. Overall Clustering Results

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mumtaz, W.; Vuong, P.L.; Malik, A.S.; Rashid, R.B.A. A review on EEG-based methods for screening and diagnosing alcohol use disorder. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2018, 12, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, W.; Vuong, P.L.; Xia, L.; Malik, A.S.; Abd Rashid, R.B. Automatic diagnosis of alcohol use disorder using EEG features. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 105, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Anuragi, A.; Sisodia, D.S. Alcohol use disorder detection using EEG signal features and flexible analytical wavelet transform. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2019, 52, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, W.; Kamel, N.; Ali, S.S.A.; Malik, A.S. An EEG-based functional connectivity measure for automatic detection of alcohol use disorder. Artif. Intell. Med. 2018, 84, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, M.K.; Liu, Y.; Esser, M.B.; Mesnick, J.B.; Lu, H.; Pan, Y.; Greenlund, K.J. Binge drinking among adults, by select characteristics and state—United States, 2018. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 4084–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcohol Research and Staff. Drinking patterns and their definitions. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2018, 39, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Yang, R.; Huang, M.; Zeng, N.; Liu, X. A review on transfer learning in EEG signal analysis. Neurocomputing 2021, 421, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Chugh, N. Review of machine learning techniques for EEG based brain computer interface. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 3001–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.C.; Rebouças Filho, P.P.; Peixoto Jr, E.; Kumar, A.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Classification of EEG signals to detect alcoholism using machine learning techniques. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2019, 125, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, D.; Chudiwal, R.; Rajput, J.; Nalbalwar, S.; Nandgaonkar, A.; Wagh, A. Detection of Alcoholism from EEG signals using Spectral and Tsallis Entropy with SVM. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Communication Information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), Mumbai, India, 25–27 June 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-H.; Muhammad, K.; Hong, J.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Zhang, Y.-D. Alcoholism identification via convolutional neural network based on parametric ReLU, dropout, and batch normalization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, S.; Bajaj, V. Rhythm-based identification of alcohol EEG signals. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2018, 12, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, S.K.; Rajaguru, H. Alcoholic EEG signal classification with Correlation Dimension based distance metrics approach and Modified Adaboost classification. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Källmén, H.; Elgán, T.H.; Wennberg, P.; Berman, A.H. Concurrent validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in relation to Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) severity levels according to the brief DSM-5 AUD diagnostic assessment screener. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Administration. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohutsiwa, L.O.; Jamisola, R.S. EEG-Based human emotion classification using combined computational techniques for feature extraction and selection in six machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 6–8 May 2021; pp. 1095–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.; Sharma, T.; Mahmud, M. Improving alcoholism diagnosis: comparing instance-based classifiers against neural networks for classifying EEG signal. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Brain Informatics, Padua, Italy, 19–21 September 2020; pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoog, S.; Dopmeijer, J.M.; De Jonge, J.M.; Van Der Heijde, C.M.; Vonk, P.; Bovens, R.H.L.M.; De Boer, M.R.; Hoekstra, T.; Kunst, A.E.; Wiers, R.W. The use of the alcohol use disorders identification test—Consumption as an indicator of hazardous alcohol use among university students. Eur. Addict. Res. 2020, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler, H.R.; Soyka, M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: a review. JAMA 2018, 320, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramfort, A.; Luessi, M.; Larson, E.; Engemann, D.A.; Strohmeier, D.; Brodbeck, C.; Goj, R.; Jas, M.; Brooks, T.; Parkkonen, L.; Hämäläinen, M.S. MEG and EEG Data Analysis with MNE-Python. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leske, S.; Dalal, S.S. Reducing power line noise in EEG and MEG data via spectrum interpolation. Neuroimage 2019, 189, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, P.; Yaacob, S.; Krishnan, A.P.; Rizon, M.; Ang, C.K. EEG based Drowsiness Detection using Relative Band Power and Short-time Fourier Transform. J. Robot. Netw. Artif. Life 2020, 7, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A. Independent component analysis: An introduction. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2021, 17, 222–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Asl, B.M. Automatic seizure detection using orthogonal matching pursuit, discrete wavelet transform, and entropy based features of EEG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 131, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, F.A.; AlSharabi, K.; Abdurraqeeb, A.M.; Aljalal, M. EEG signal analysis for diagnosing neurological disorders using discrete wavelet transform and intelligent techniques. Sensors 2020, 20, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSharabi, K.; Salamah, Y.B.; Abdurraqeeb, A.M.; Aljalal, M.; Alturki, F.A. EEG signal processing for Alzheimer’s disorders using discrete wavelet transform and machine learning approaches. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 89781–89797. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qerem, A.; Kharbat, F.; Nashwan, S.; Ashraf, S.; Blaou, K. General model for best feature extraction of EEG using discrete wavelet transform wavelet family and differential evolution. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2020, 16, 1550147720911009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D.; Brucher, M.; Perrot, M.; Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Lian, J.; Hou, S. Feature dimensionality reduction: a review. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 2663–2693. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, B.M.S.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A review of principal component analysis algorithm for dimensionality reduction. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2021, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhani, F.; Zarlis, M.; Suwilo, S. Improve BIRCH algorithm for big data clustering. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2020; Volume 725, p. 012090. [Google Scholar]

- Pscherer, C.; Mückschel, M.; Summerer, L.; Bluschke, A.; Beste, C. On the relevance of EEG resting theta activity for the neurophysiological dynamics underlying motor inhibitory control. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 4253–4265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz, H.; Cid, F.M.; Otárola, J.; Rojas, R.; Alarcón, O.; Cañete, L. EEG Beta band frequency domain evaluation for assessing stress and anxiety in resting, eyes closed, basal conditions. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scally, B.; Burke, M.R.; Bunce, D.; Delvenne, J.-F. Resting-state EEG power and connectivity are associated with alpha peak frequency slowing in healthy aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 71, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Son, K.L.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, J.; Park, S.M.; Lim, J.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.N.; Oh, S.; Kim, D.J.; Kwon, J.S. Neurophysiological features of Internet gaming disorder and alcohol use disorder: a resting-state EEG study. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e628. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Barba, R.; Sion, A.; Martínez-Maldonado, A.; Domínguez-Centeno, I.; Prieto-Montalvo, J.; Navarrete, F.; García-Gutierrez, M.S.; Manzanares, J.; Rubio, G. Neuropsychophysiological measures of alcohol dependence: can we use EEG in the clinical assessment? Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 523188. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.M.; Hasan, N.; Alsubaie, M.S.A.; Komol, M.M.R. Diagnosis of tobacco addiction using medical signal: An EEG-based time-frequency domain analysis using machine learning. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. 2021, 6, 842–849. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, N.A.; Bauer, L.O.; Houston, R.J. Recent EEG and ERP findings in substance abusers. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2009, 40, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsi, L.; Siuly, S.; Kabir, E.; Wang, H. Classification of alcoholic EEG signals using a deep learning method. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 3552–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, H.; Qaisar, S.M.; Zaguia, A. Deep convolutional neural network regularization for alcoholism detection using EEG signals. Sensors 2021, 21, 5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, , Text Revision (DSM-5-TR™), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rangaswamy, M.; Porjesz, B. Understanding alcohol use disorders with neuroelectrophysiology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 125, 383–414. [Google Scholar]

- Didier, N.; Vena, A.; Feather, A.R.; Grant, J.E.; King, A.C. Holding your liquor: Comparison of alcohol-induced psychomotor impairment in drinkers with and without alcohol use disorder. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 47, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Caneda, E.; Cadaveira, F.; Correas, A.; Crego, A.; Maestú, F.; Rodríguez Holguín, S. The brain of binge drinkers at rest: alterations in theta and beta oscillations in first-year college students with a binge drinking pattern. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Antunes, N.; Crego, A.; Carbia, C.; Sousa, S.S.; Rodrigues, R.; Sampaio, A.; López-Caneda, E. Electroencephalographic signatures of the binge drinking pattern during adolescence and young adulthood: a PRISMA-driven systematic review. NeuroImage Clin. 2021, 29, 102537. [Google Scholar]

| Author & Year | EEG Experimentsused | Type ofdisorder | Machine LearningModel Used | Dataset used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Son et al.,2015 [36] | Resting stateEEG | IGDAUD | Statistical analysisGeneralized estimatingequation Naive bayes classifierKNNLogistic regression | 34 males with IGD17 males with AUD25 Healthy controls |

| Mumtaz et al.,2016 [2] | Resting stateEEG 10 minutes EC 10mins EO conditions | AUD | Linear Discriminant AnalysisSVM Multilayer back-Propagation Network Logistic Model Trees | 12 alcohol abusers 18 alcoholics 15 healthy controls |

| Mumtaz et al.,2021 [4] | Resting stateEEG | AUD | SVMNaive BayesLogistic regression | 30 AUD patients 30 age-matchedhealthy controls |

| Rodrigues et al.,2019 [9] | Online EEG dataset | Alcoholism | SVMOPFNaive BayesKNNMLP | UCI KDD EEGdataset45 normal subjects and77 alcoholic patients |

| Anuragi et al.,2020 [3] | Online EEG dataset | AUD | LS-SVMSVMNaive Bayes | UCI KDD EEGdataset45 normal subjects and77 alcoholic patients |

| Mukhtar et al.,2020 [41] | Online EEG dataset | Alcoholism | CNN | UCI KDD EEGdataset45 normal subjects and77 alcoholic patients |

| Farsi et al.,2020 [40] | Online EEG dataset | Alcoholism | ANNLSTM | UCI KDD EEGdataset45 normal subjects and77 alcoholic patients |

| Domains | Questions | Item Content | Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazardous alcohol use | 1 | Frequency of drinking | 31 |

| 2 | Typical quantity | 45 | |

| 3 | Frequency of heavy drinking | 38 | |

| Dependence symptoms | 4 | Impaired control over drinking | 21 |

| 5 | Increased salience of drinking | 13 | |

| 6 | Morning drinking | 25 | |

| Severe alcohol use | 7 | Guilt after drinking | 28 |

| 8 | Blackouts | 28 | |

| 9 | Alcohol-related injuries | 9 | |

| 10 | Others concerned about drinking | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).