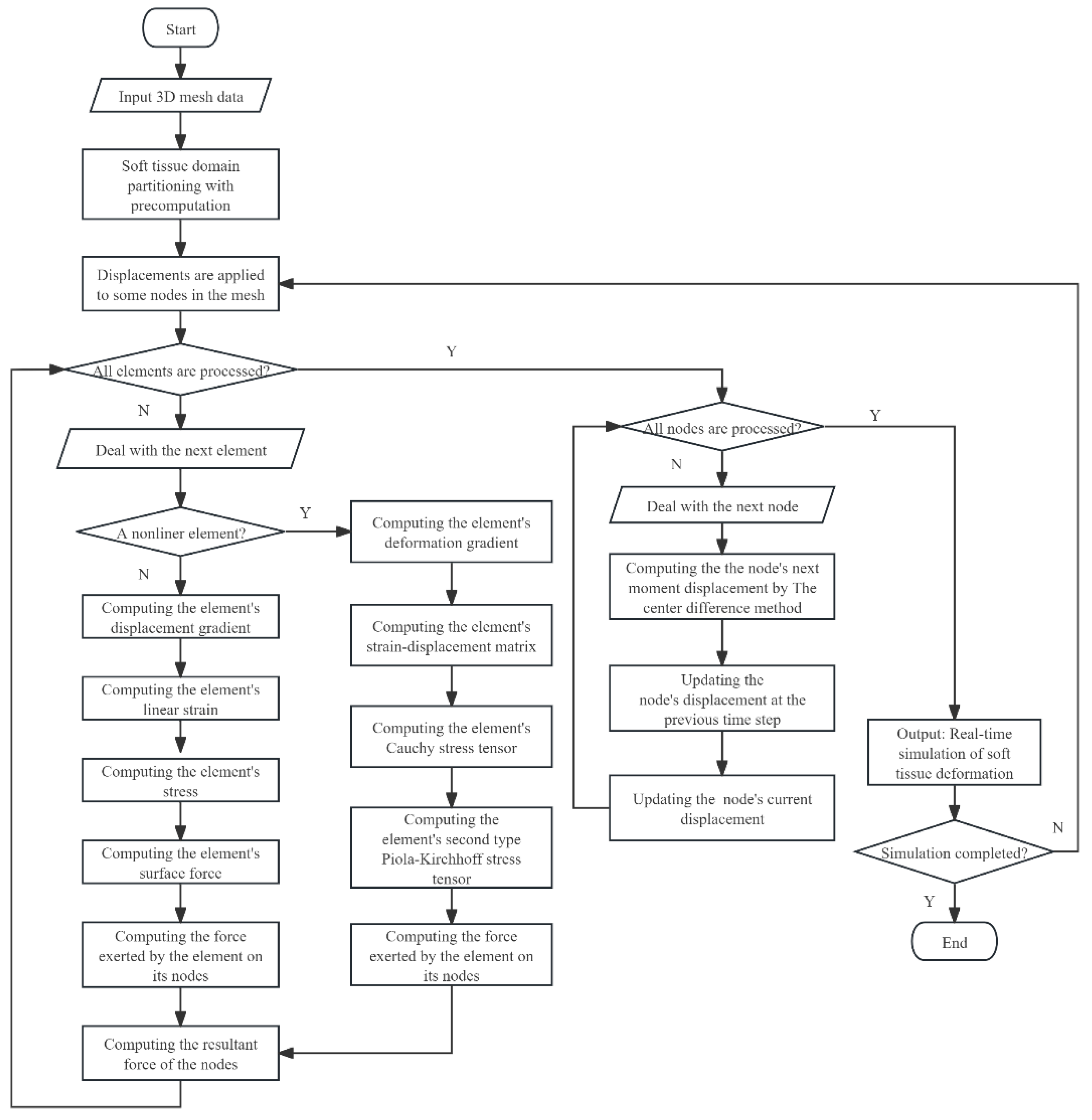

The DHD-FEA framework integrates four sequential stages: (1) soft tissue domain partitioning with precomputation, (2) subdomain-specific element stress analysis, (3) nodal resultant forces analysis, and (4) hybrid model-driven displacement resolution. Initially, the tissue geometry is partitioned into linear and nonlinear subdomains using biomechanical criteria, with tailored precomputation of domain-specific parameters (e.g., material properties and geometric invariants). During the element analysis phase, a hybrid finite element methodology is selectively applied to each subdomain, deriving critical mechanical metrics—including stress tensors, strain distributions, and nodal interaction forces—through subdomain-appropriate constitutive models. Following this, nodal force integration synthesizes all element-induced force contributions at each node via vector summation, yielding the resultant force field across the tissue mesh. Finally, explicit time integration is implemented to compute dynamic nodal displacements between successive timesteps, enabling deterministic reconstruction of vertex trajectories and tissue morphodynamics. This framework achieves an optimized balance between computational tractability and biomechanical realism through adaptive domain-specific computation and hybrid numerical formulation.

2.2.1. Soft Tissue Domain Partitioning with Precomputation

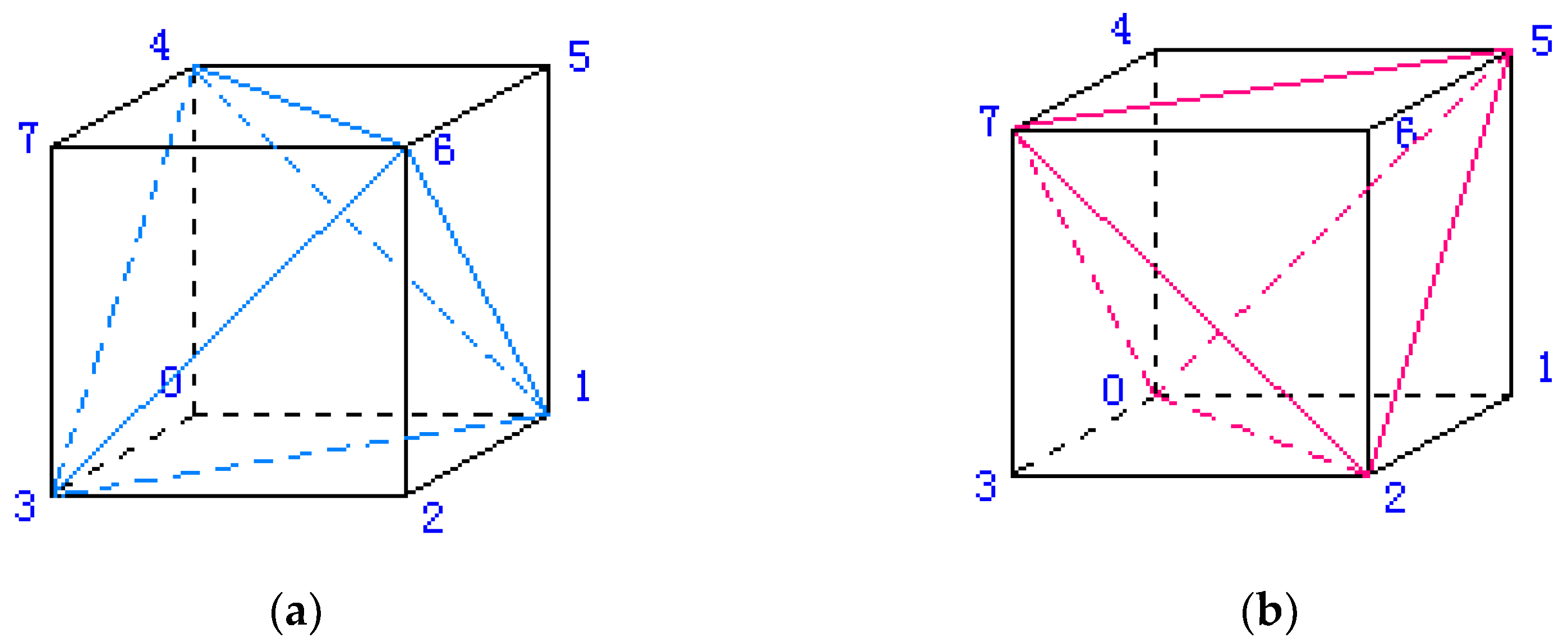

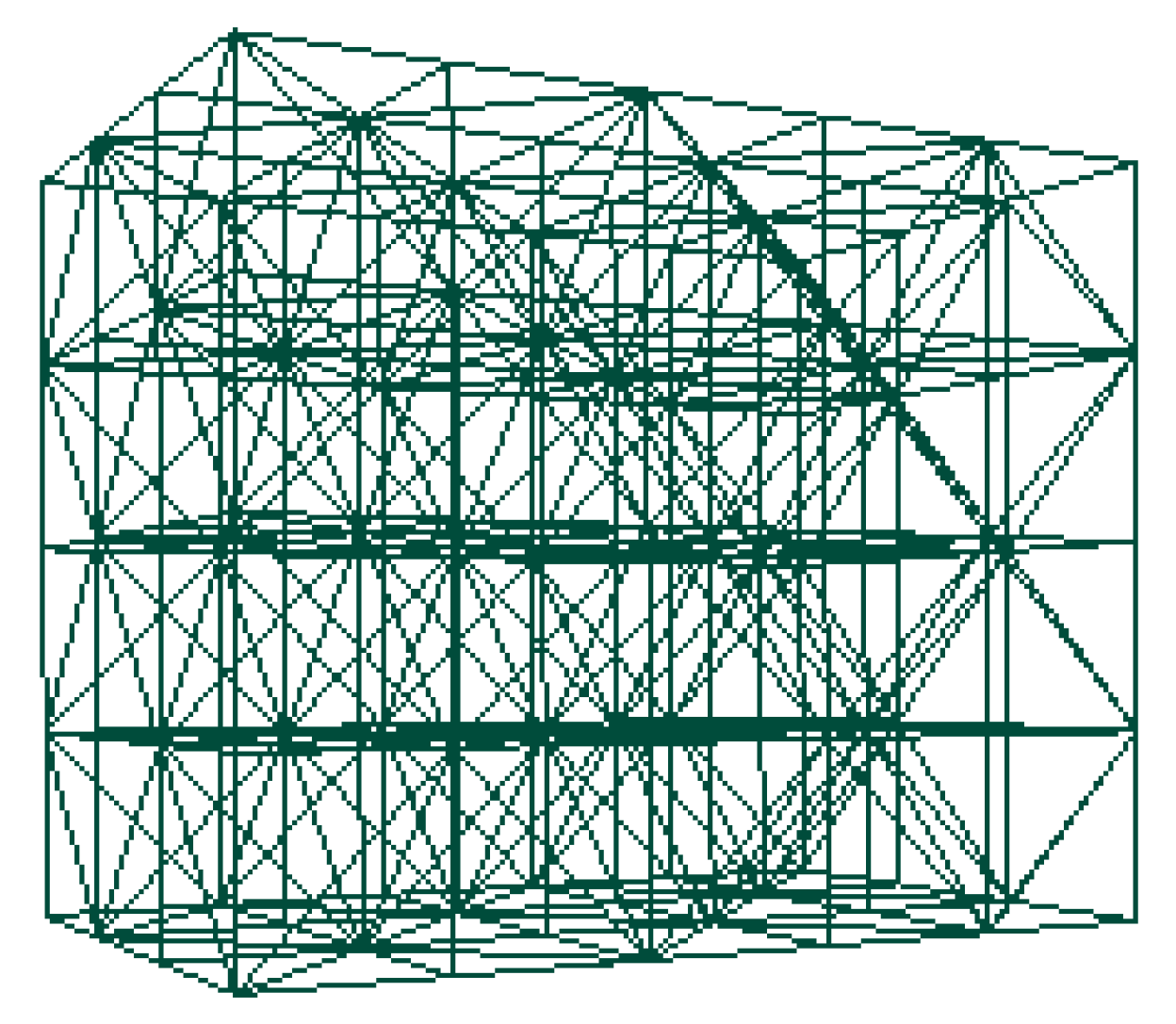

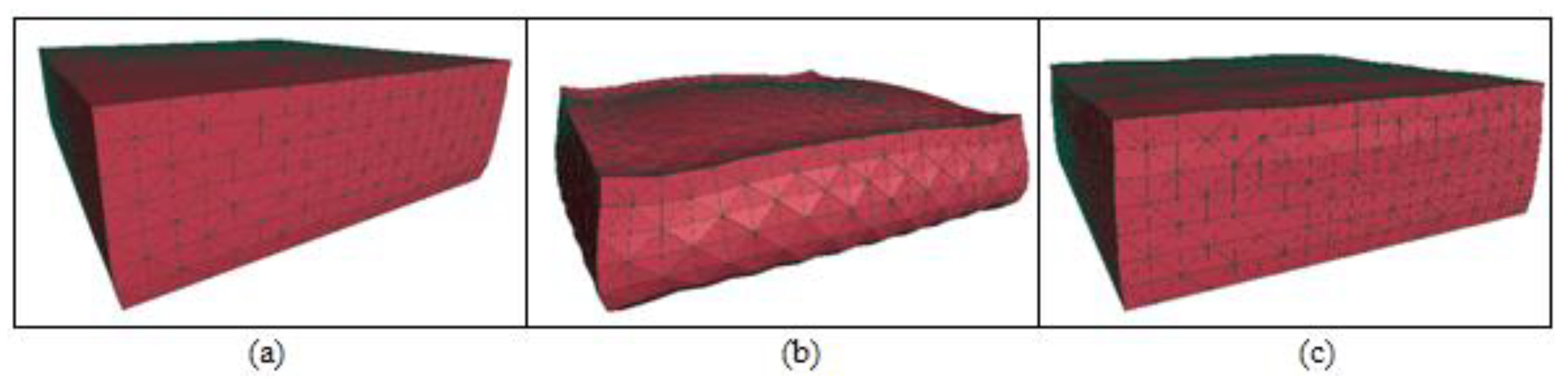

In the study, soft tissue structures are computationally modeled as 3D mesh data to serve as algorithm inputs. To enable systematic algorithmic control over mesh resolution, we implement a structured spatial discretization approach that partitions the regular cuboid domain into finite elements through systematic subdivision. The methodology initiates with volumetric decomposition of the bounding cuboid into uniform hexahedral elements, followed by subsequent refinement where each cubic element undergoes optimized partitioning into five tetrahedral sub-elements. This hierarchical discretization process generates a comprehensive set of finite elements and corresponding nodal coordinates, ensuring both geometric regularity and computational tractability for subsequent numerical analysis (

Figure 2).

The algorithm also enables precise control over the mesh density (number of elements), the geometric properties (shape and size) of individual elements, and the spatial distribution of the grid. Such programmatic adaptability provides critical flexibility for simulating soft tissue deformation, ensuring biomechanical accuracy (

Figure 3).

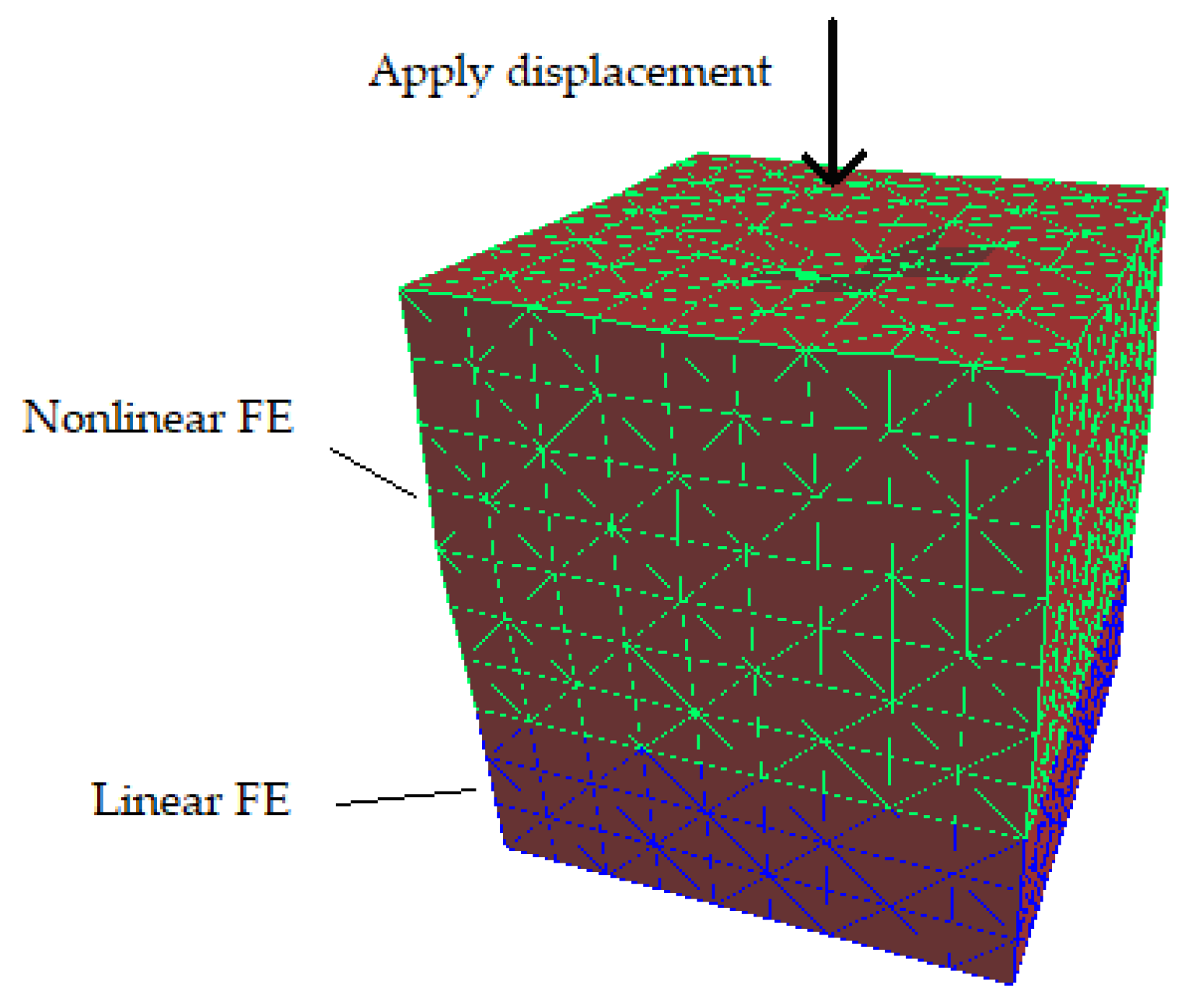

To solve soft tissue deformation using the DHD-FEA, the model's elements must be partitioned into two categories: linear and nonlinear elements. For complex anatomical structures or specific surgical maneuvers, the delineation of surgical zones can become nontrivial, requiring meticulous consideration of mesh geometry, the proportion of nonlinear finite elements, and their spatial distribution. Consequently, when applying this algorithm for surgical simulation, scenario-specific mesh configurations must be prepared for targeted operative contexts. In the simplest implementation, elements may be categorized hierarchically. For instance, as illustrated in

Figure 2, a mesh comprising five hierarchical layers can be configured by designating select layers as linear elements and the remainder as nonlinear. This study assumes surgical interactions occur on the top surface of a rectangular prism-shaped soft tissue mesh; accordingly, the upper portion of the prism is assigned nonlinear soft tissue properties, while the lower elements are treated as linear.

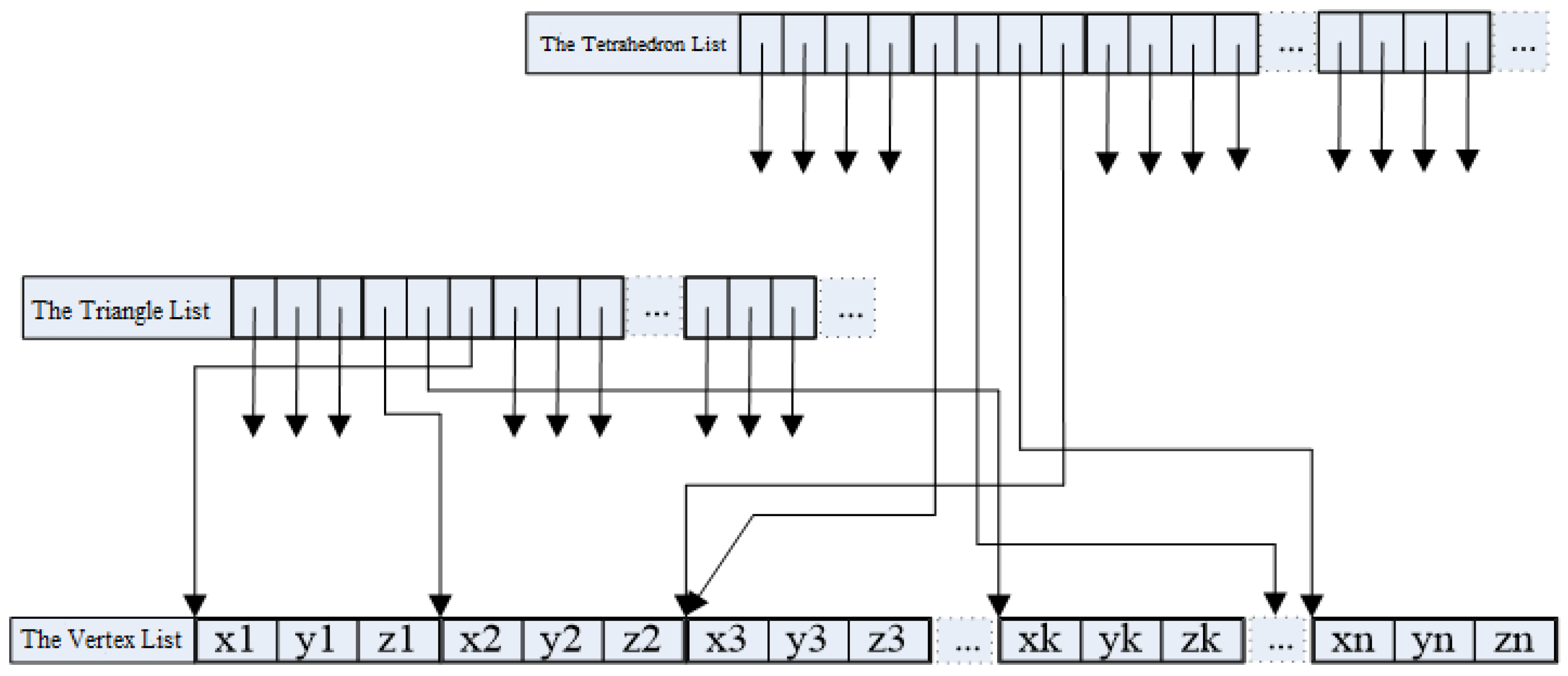

In deformation computation using FEM, the primary focus lies on mesh element attributes and their nodal connectivity relationships. Conversely, the graphics rendering pipeline prioritizes the object's surface mesh topology. This dichotomy necessitates the data structure architecture for deformation simulation programs, as schematically depicted in

Figure 4.

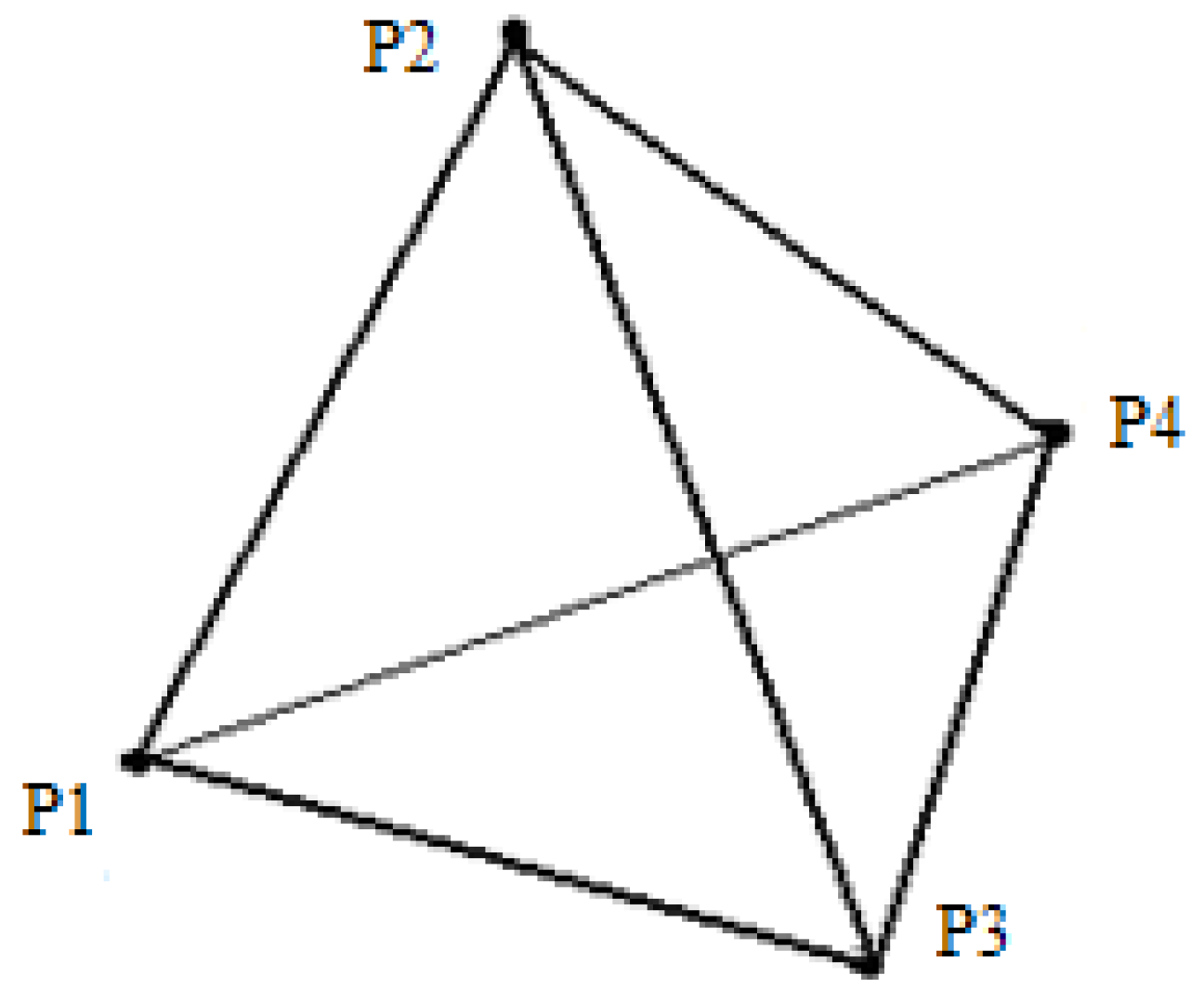

The entire object domain is discretized into tetrahedral elements, each comprising four nodes. The simulation employs preprocessed data for computational efficiency. Specifically, the element information encompasses precomputed physical quantities from Equation (18), precomputed data

tD

X from Equation (7), and the initial volume of each element. Additionally, the node information includes the nodal mass, the initial position of the node, the resultant force acting on the node due to internal and external forces, the displacement at the previous time step, the current displacement, and the predicted displacement for the next time step. We assume that there is a tetrahedral unit in the current target region with nodes P

1, P

2, P

3, and P

4 (as shown in

Figure 5).

The tetrahedral volume is calculated as shown in the equation as follow:

2.2.2. Subdomain-Specific Element Stress Analysis

The finite elements are divided into linear and nonlinear elements according to the location in DHD-FEA method, such as Equation (2) and Equation (3).

O is the Operational Region, N for the Non-Operational Region, and I for the common area of the two regions. The equations of the two parts are similar, but the finite element equations are different. This section mainly describes the element stress analysis methods of linear finite elements and nonlinear finite elements.

In this framework, the deformation of linear finite elements is constrained to less than 10%, enabling the use of the initial (reference) configuration to approximate the deformed geometry. The Cauchy strain tensor and Cauchy stress tensor are employed to characterize the material’s strain and stress states, respectively. Due to the fixed linear constitutive relationship between strain and stress—which remains invariant to deformation magnitude—the linear model achieves higher computational efficiency compared to nonlinear approaches. However, this simplification compromises simulation accuracy, as it neglects geometric and material nonlinearities inherent to large deformations.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, a tetrahedral element with nodes P₁, P₂, P₃, and P₄ has initial nodal positions

,

,

,

and deformed positions

,

,

,

. To compute the Cauchy strain tensor, the displacement field must be determined throughout the element, requiring derivation of the displacement gradient. For an arbitrary material point within the tetrahedron, let its initial coordinate be

and deformed position be

The weights governing this point’s spatial relationship to the others tetrahedral nodes remain invariant throughout the deformation process. The

and

of a point is calculated by the equations as follow.

are weights of a point, and

is calculated by the Equation (5) as follow.

In the same way, the

is calculated by:

are weights of a point, and

is calculated by the Equation (7) as follow.

Finally, the position of the point after deformation is calculated by:

is a 3 by 3 matrix representing the mapping of any point position inside the tetrahedron before and after the deformation, and the displacement of any point can be expressed as . And since remains constant throughout the simulation process, it is feasible to pre-calculate it.

Therefore, the displacement gradient of the point is calculated by the following equation.

where

I is the identity matrix, and the Cauchy strain tensor can be expressed by:

After calculating the Cauchy strain tensor, the Cauchy stress σ is obtained through the constitutive equation. The Cauchy stress σ is defined as shown in Equation (11).

where

df is the force acting on an infinitesimal surface in space,

dA is the area of that surface, and

n is the unit normal vector to the surface.

Therefore, the resultant force acting on each face of the tetrahedral element due to stress can be obtained from Equation (12).

where σ a denotes the Cauchy stress tensor,

n is the unit normal vector to the triangular face of the tetrahedral element, and

A represents the area of the triangular face. Since the tetrahedron is modeled as a linear finite element, the resultant surface force

f can be uniformly distributed to each node of the triangular face, thereby allowing the nodal forces

exerted by the tetrahedral element on all nodes to be determined.

- 2.

The nonlinear finite elements stress analysis method

The nonlinear model of the DHD-FEA in the surgical area employs the TLED algorithm. Due to the substantial deformations often exhibited by soft tissues in surgical regions, linear strain tensors such as the infinitesimal (Cauchy) strain tensor are inadequate for solving such nonlinear problems. Instead, the Green-Lagrange strain tensor is adopted as the nonlinear strain measure, and the stress tensor is correspondingly replaced by the Second Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor. Furthermore, the constitutive relationship between stress and strain in these materials is not fixed. A simplified yet effective nonlinear framework for modeling such behavior is the hyperelastic model, where many biological soft tissues can be approximated as hyperelastic materials characterized by strain energy density functions. The nodal forces exerted by nonlinear elements on their corresponding nodes can be calculated using Equation (13).

is the vector form of the Second Piola-Kirchhoff stress, is the Strain-displacement matrix, and 0V is the initial volume of an element. This equation performs force analysis at the element level, with all variable values obtainable from the local information of the element.

We employed the Neo-Hookean model to solve for the stress tensor

. The stress components

are derived by differentiating the neo-Hookean strain energy function W with respect to the Green strain tensor. [

17,

18] And the equation is as follow:

where

is the Right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor. And the

was calculated by:

Due to the Strain-displacement matrix

is relate to the geometry of the element, it changes with the geometry of the element. Because a tetrahedron contains four nodes, the

can be represented as a set of its submatrices by:

is the

I-th node of the corresponding element of the

I-th submatrix of

. And

is calculated by:

is the deformation gradient of the element. And

is calculated by the Equation (18).

To solve for the

, it is necessary to compute the derivatives of the shape functions with respect to the spatial coordinates

,

,

. And the spatial derivatives of shape functions are typically calculated using the isoparametric finite element formulation. The core principle of the isoparametric finite element formulation lies in relating the displacement at any point within an element to the nodal displacements through shape functions. In a tetrahedral isoparametric element, the shape functions

at the four nodes P

1, P

2, P

3, P

4 can be expressed as

, where the isoparametric coordinates

r, s, t are defined in the range [–1,1], as shown in Equation (19).

where

i denotes the local index of the corresponding vertex within the element.

According to the rules of partial differentiation, the relationship between the derivatives of the shape functions and the isoparametric coordinates is given in Equation (20).

Equation (20) derives the relationship between the partial derivatives of the shape functions with respect to the isoparametric coordinates and the partial derivatives of the shape functions with respect to the physical coordinates, as well as the partial derivatives of the physical coordinates with respect to the isoparametric coordinates, using the chain rule. Through a series of identity transformations, Equation (21) is obtained.

Therefore, we can proceed to compute the spatial derivatives of the shape functions (with respect to physical coordinates), as shown in Equation (22).

, , represent the derivatives of the shape functions with respect to the isoparametric coordinates in an isoparametric element. Since the isoparametric coordinates of points within each element remain invariant, the derivative values of the shape functions at the integration points are constant throughout the simulation.

For each tetrahedral element, the initial positions of its four nodes are , , , . Since these positions remain invariant throughout the deformation simulation, the spatial derivatives of the shape functions computed via Equation (22) is also constant during the entire deformation process. Thus, the matrix can be computed using Equation (18), and subsequently, the strain-displacement matrix for the element is obtained via Equation (16). With these matrices, the nonlinear internal forces acting on the element’s nodes can be further determined. Crucially, the matrix remains invariant throughout the entire deformation simulation, yet its computation is computationally intensive. Therefore, the matrix for each element is precomputed during the preprocessing stage, and the pre-computed data is directly reused in real-time simulations to significantly accelerate the deformation computation.

Following the mechanical analysis of linear and nonlinear zonal elements, it is necessary to apply all resultant forces to the interface nodes. The interfacial nodes connecting both zones, referred to as intermediate nodes, exhibit hybrid connectivity with both nonlinear and linear elements. Conventional Equation (2) and (3) typically require independent computation of these intermediate nodes followed by simultaneous solution of the coupled equation systems. However, the proposed algorithm eliminates the need for global stiffness matrix assembly, thereby enabling direct integration of intermediate nodes through a streamlined computational process. During element-level analysis, the forces exerted by each element on its connected nodes are computed without nodal type restrictions, ensuring comprehensive force transmission to all nodes –whether in nonlinear zones, linear zones, or intermediate positions. Subsequent nodal force analysis inherently incorporates all nodal points by calculating the resultant forces acting on each node through superposition of contributions from adjacent elements. This methodology naturally accommodates intermediate nodes within the standard computational framework, achieving systematic force equilibrium without necessitating special treatment for interfacial nodes.

2.2.3. Nodal Resultant Forces Analysis

Following the elemental stress analysis, the DHD-FEA has determined the nodal force vectors

exerted by tetrahedral elements on their corresponding nodes. The subsequent computational phase necessitates the evaluation of the resultant force at each node

through systematic superposition of contributions from all topologically connected elements. For each nodal point within the discretized mesh, let

denote the force exerted by an incident element

e connected to the node. The resultant force

acting on the node due to all incident elements is computed through vector superposition as prescribed in Equation (23):

When external forces (e.g., applied nodal loads, boundary tractions, or body forces) act on node v, the total resultant force is computed as .

In the DHD-FEA, the displacement field within an element is approximated through nodal displacement interpolation, while distributed external forces and internal interactions between adjacent elements are consistently as nodal forces. This framework enables the application of Newtonian mechanics for nodal equilibrium analysis. For static systems, nodes remain in a stationary state governed by the equilibrium relationship expressed in Equation (24).

For dynamic systems without damping effects, the nodal dynamic equilibrium equation is formulated as:

is the mass of a node, and

is the displacement of the node. The nodal acceleration

is the second derivative of the nodal displacement

with respect to time.

is the force exerted by the unit pair on the node, and

is the resultant force of the external forces acting on the node. For the nodes with damping effect, their dynamic equilibrium equations are as shown as Equation (26).

The damping term is added in the above Equation (26). And represents the damping factor of the node, and the node velocity is the first derivative of the node displacement with respect to time.

2.2.4. Hybrid Model-Driven Displacement Resolution

In static systems, all physical quantities remain independent of time. Static equilibrium equations can also be applied to quasi-static scenarios. In such scenarios, the system states evolve temporally, but at a sufficiently slow rate that inertial and damping effects become negligible. These formulations are applicable to analyses including foundation settlement and dam impoundment. However, their suitability diminishes in surgical contexts involving tissue deformation and incision operations, where rapid state variations occur–for instance, the viscoelastic rebound and oscillation of organs following instrument indentation. When temporal displacement variations exhibit significant rates, necessitating the consideration of inertial effects, dynamic system formulations become imperative. In such systems, acceleration terms manifest explicitly in the governing equations, accompanied by velocity-dependent damping effects. Compared to static systems, displacement variables attain heightened significance in dynamic analyses. The fundamental governing equations of dynamics derive from force equilibrium principles rooted in Newtonian mechanics, incorporating both inertial and dissipative forces.

In static analysis, an exact solution can typically be obtained. However, in dynamic analysis, achieving an exact solution is significantly more challenging due to the need to account for material distribution and damping effects [

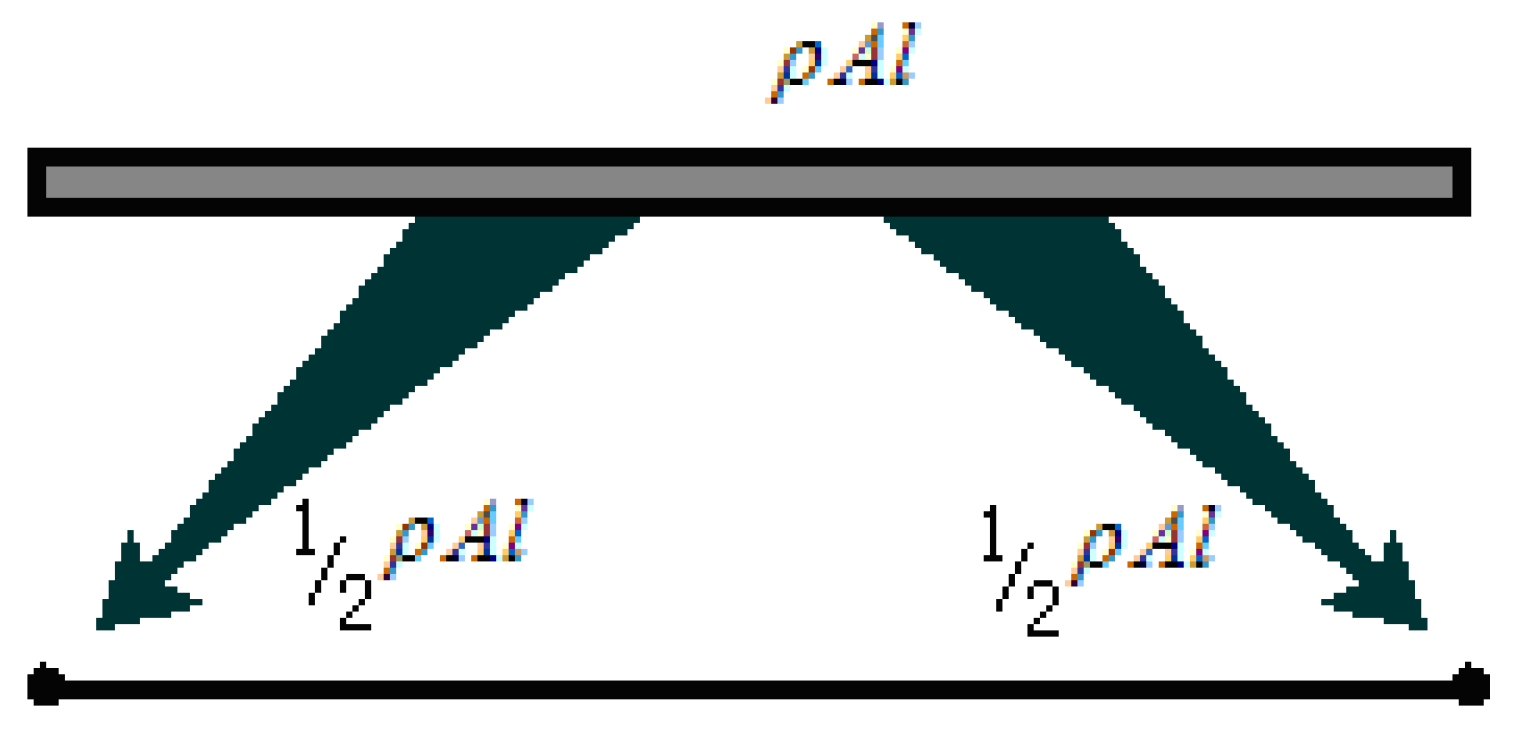

19]. In dynamic finite element analysis, it is necessary to generate at least a mass matrix to complement the stiffness matrix. The assembly procedures for the mass matrix M and stiffness matrix K can be executed concurrently within finite element frameworks. Element-level mass matrices are initially formulated in local coordinate systems before undergoing coordinate transformation to the global system, mirroring the assembly methodology employed for the global stiffness matrix. A fundamental distinction between these matrices lies in the diagonalization capability of the mass matrix via direct lumping techniques. This diagonalization confers critical computational advantages: (1) The inversion of diagonal matrices requires substantially fewer operations compared to full matrices, and (2) the diagonal structure enables explicit time integration schemes at the element level without coupled equation solutions. Consequently, mass lumping significantly optimizes computational efficiency in dynamic simulations.

The objective of direct mass lumping (DML) is to generate a diagonally-lumped mass matrix (DLMM) for dynamic systems. This technique allocates the total mass of element e to its nodal degrees of freedom by directly distributing mass contributions to individual nodes, thereby eliminating off-diagonal coupling terms associated with inter-nodal interactions. The simplest illustration of direct mass lumping involves a two-node prismatic bar element with length

l, uniform cross-sectional area

A and mass density

, as depicted in

Figure 6.

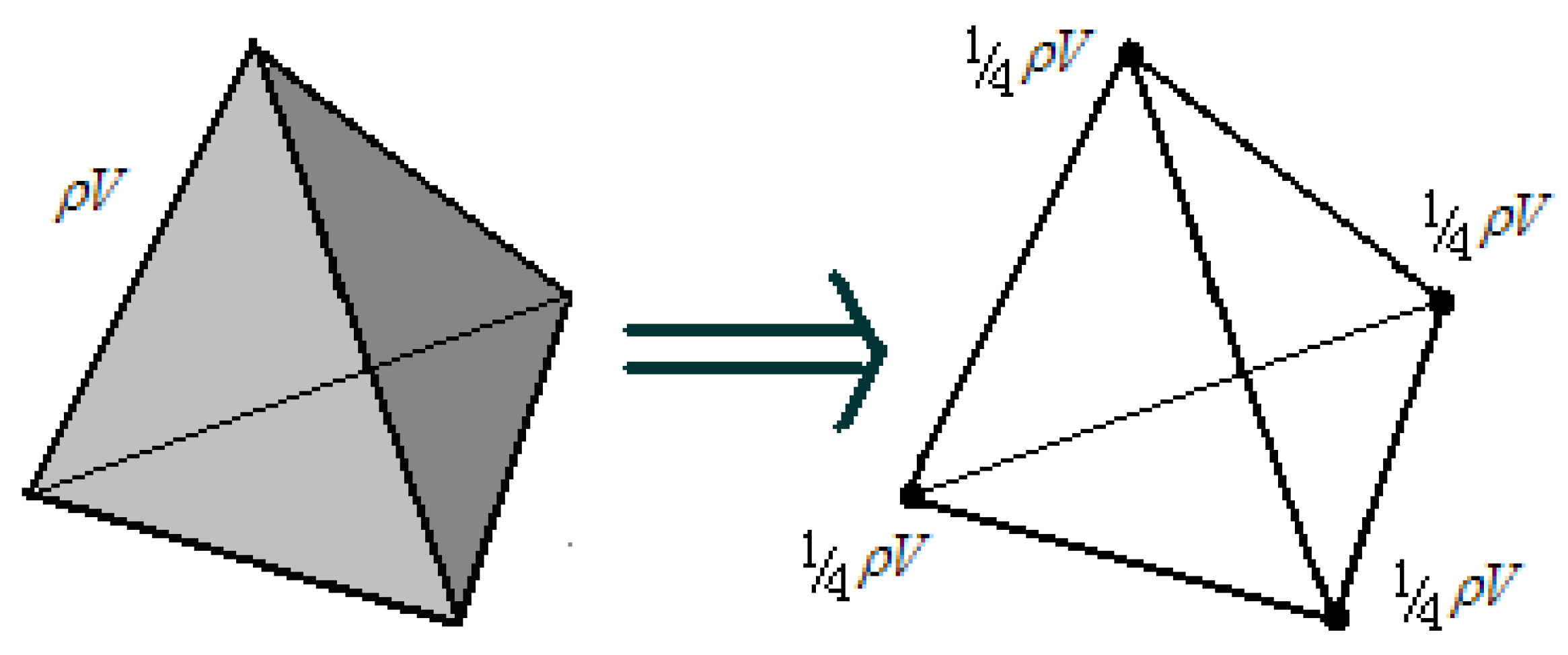

The total mass

of a tetrahedral element (where

is material density and

V denotes element volume) is distributed to its four nodes using the mass lumping method, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

The finite element mass matrix is transformed into a diagonal matrix via the direct mass lumping procedure, where elemental mass is redistributed to nodal degrees of freedom while preserving total mass conservation. Under the proportional damping assumption (

, where

is a material-dependent constant), the damping matrix inherits the diagonal structure from the lumped mass matrix. This formulation allows the stiffness term

to be expressed in the decoupled form of Equation (27):

e is the elements in the set, and is the force of an element on the node. Equation (27) describes that the internal forces acting on each node in a structural system can be calculated through the assembly of the global stiffness matrix followed by its multiplication with the nodal displacement vector. Alternatively, the second methodology involves conducting stress analysis at the element level, where individual unit contributions are resolved through constitutive relationships.

The diagonal configuration of both mass matrix

M and damping matrix

D indicates that nonzero elements exclusively populate their main diagonals, while off-diagonal entries remain 0. This structural property ensures that the mass and damping characteristics of each node operate independently, with no cross-coupling effects between distinct nodes in the system. The dynamic equilibrium Equation (28) governing node

i incorporates the combined effects of internal stress-induced resultant force

, its mass

, damping coefficient

, instantaneous displacement

, and externally applied load

.

The integration of governing equations with the inherent diagonal properties of mass and damping matrices establishes a hierarchical computational framework for deformation simulation. This methodology enables multi-level analysis by leveraging element-specific stress-strain relationships and nodal dynamic equilibrium principles, ensuring localized force interactions are systematically resolved while maintaining global system compatibility.

The DHD-FEA methodology addresses the challenge of real-time tissue/organ deformation simulation in surgical contexts by strategically partitioning computational domains: nonlinear FEM formulations govern the surgical region to capture complex biomechanical responses, while linear FEM approximations are applied to non-surgical zones to reduce computational overhead. This multi-resolution framework optimizes computational resource allocation while maintaining physiological fidelity. Additionally, domain-specific numerical integration strategies are implemented to efficiently solve equilibrium equations, enabling stable convergence under large deformation scenarios. The temporal discretization of governing equations can be implemented through explicit or implicit integration schemes, each offering distinct computational trade-offs. [

9] But implicit integration methods maintain unconditional stability but require iterative solutions to coupled nonlinear algebraic systems, resulting in significant computational demands. In contrast, explicit schemes achieve computational efficiency through non-iterative formulations, directly advancing solutions without solving coupled equations a feature particularly advantageous for dynamic systems governed by strict time-step constraints.

The central difference method is an explicit integration scheme designed to approximate solutions for second-order differential equations. [

2] In DHD-FEA, this approach is employed to solve Equation (28), leveraging its capability to compute state variables at subsequent time steps based entirely on current dynamic conditions. In computational dynamics simulations, the temporal progression follows discrete time intervals governed by a fixed time step. When initializing a simulation at

with a defined temporal resolution

, the current state at time

t inherently determines the subsequent time increment as

through explicit temporal discretization. Within the framework of Equation (28), the displacement vector

constitutes the primary unknown requiring numerical resolution. Concurrently, all other system parameters including but not limited to velocity vectors, acceleration profiles, and environmental constraints become computationally accessible through explicit state transitions during each stepwise calculation. This deterministic progression ensures temporal causality while maintaining numerical stability through fixed-interval updates.

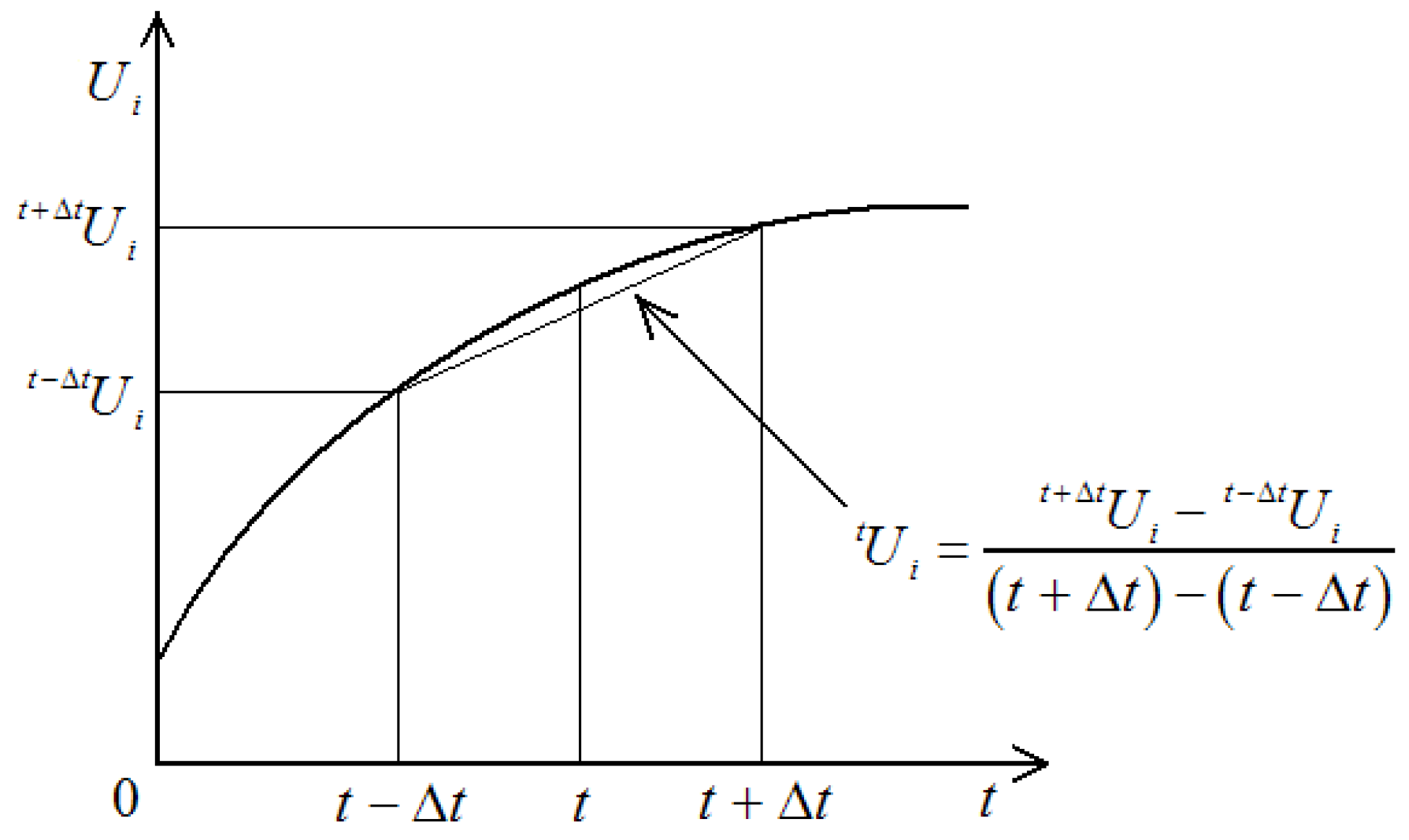

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the central difference method employs iterative temporal discretization to determine the unknown displacement function

at subsequent time instant

, where temporal superscripts systematically denote measurement instances. This explicit algorithm calculates first-order derivatives at time

through symmetric differencing principles, utilizing displacement states from adjacent time intervals to construct velocity approximations.

Therefore, the first and second order temporal derivatives of displacement function

at time

t are formulated as:

is the second derivative at time

t. The nodal equilibrium equations are derived by substituting Equations (29) and (30) into Equation (28), resulting in the governing formulation expressed as Equation (31).

The governing equations are algebraically transformed through identity operations, ultimately yielding the consolidated formulation expressed as Equation (32).

And the Equation (33) was obtained by simplifying the Equation (32).

Equation (33) provides an efficient computational framework for determining nodal displacements at subsequent time steps in DHD-FEA. This enables accurate reconstruction of object deformation characteristics through systematic time-domain integration.