1. Introduction

The significance of set theory as the foundational principle of modern mathematics is indisputable [

1,

2]. Since its inception by Cantor in the late 19th century, set theory has evolved into one of the most fundamental theories in mathematics, with almost all mathematical structures and concepts being defined and constructed through sets and their relations [

3,

4]. In the domain of mathematical analysis, for instance, the system of real numbers can be constructed through the framework of set theory. In the field of algebra, algebraic structures such as groups, rings, and domains can be regarded as sets with specific operations; in topology, the notion of a topological space is built based on sets and their subsets. Set theory plays a pivotal role in several fields of study and research, including computer science, logic, and philosophy, providing them with rigorous theoretical foundations and expressive tools, [

5,

6].

However, the emergence and development of modern set theory have had a long and challenging history [

1,

3]. The modern set theory was first proposed by the German mathematician Cantor in the 1870s [

7], who was interested in studying set theory from the “uniqueness of the expansion of a function into a trigonometric series”. Cantor thus gave a more complete theoretical system and studied the ordinal and cardinal numbers of infinite sets. Initially, the mathematical community of that era did not universally embrace the naive set theory, and it faced significant scrutiny. Although prominent mathematicians, such as Dedekind, endorsed the study of naive set theory, it faced considerable opposition from the constructivist school led by Kronecker. Nevertheless, due to its conceptual validity, the naive set theory gradually gained acceptance in the mathematical community and was widely and highly praised [

8,

9,

10]. Mathematicians regarded naive set theory as the cornerstone of modern mathematics on which all mathematical results could be built [

11,

13].

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, many mathematicians found some contradictions in simple set theory [

19,

20,

21]. Even Cantor himself posed a paradoxical question in 1899, “What is the cardinal number of a set consisting of all sets?” In 1902, the English mathematician Russel discovered one of the simplest paradoxes in naive set theory, called “Russel’s paradox”, “Whether a set consisting of all sets which do not contain the set itself contains itself?” Later, in 1919, Russel also gave a popular form of this paradox, “the barber’s paradox”, which pointed out the contradictions in naive set theory and caused a great shock in the mathematical world, shaking those who believed that the foundations of mathematics had been laid. A famous German mathematician, Hermann Weyl, said: “The question of the final foundations and ultimate meaning of mathematics is still unresolved, and we do not know in which direction to look for the final answer.” The discovery of paradoxes in set theory shook the foundations of mathematics and thus directly triggered the third mathematical crisis.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, mathematicians started the study of the axiomatization of set theory by restricting the definitions of simple set theory by axioms to solve the paradoxes in set theory [

22]. The starting point of axiomatizing set theory is to give a set of axioms that should be satisfied by a set and study the properties of sets on this basis [

23,

24]. Contemporary axiomatic set theory is predicated on three central axiomatic systems: Zermelo-Fraenkel system with the Axiom of Choice (ZFC) [

10,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], von Neumann-Bernays-Gödel system (NBG) [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], and Morse-Kelley system (MK) [

11,

12,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. 1908, German mathematician Zermelo first published an axiomatic system of set theory, which was later improved and modified by mathematicians Fraenkel and Skolem and formed the famous Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory . In 1920, the Hungarian-American mathematician von Neumann proposed another axiomatic system, which was modified by Bernays starting in 1937 and further simplified by Gödel in 1940, which is the NBG system. Since then, there have been a large number of axiomatic set theory systems, such as Morse-Kelley set theory, Tarski-Grothendieck set theory and so on. The idea of the Morse-Kelley axiomatic set theory was first proposed by Wang Hao in 1949. Kelley and Morse officially published their own versions in 1955 and 1965, respectively. Kelley explicitly stated in his paper that this axiomatic system is closer to the NBG system. The following list summarizes the characteristics, relationships, and historical development of the three major axiomatic systems.

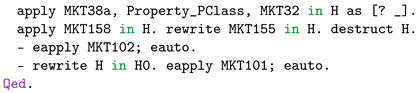

ZFC Set Theory: Establishing “set” as its fundamental concept, asserting that all mathematical objects are sets. It elegantly circumvents “Russell’s paradox” by prohibiting self-containing sets and excluding “proper classes” from its ontology. Comprising the Zermelo-Fraenkel system augmented with “the Axiom of Choice (AC)”, it is the predominant axiomatic foundation for contemporary mathematics.

NBG Set Theory: Conceived by von Neumann, systematically developed by Bernays, and refined by Gödel. It elevates “class” to its fundamental concept and averts paradoxes through carefully constructed structural constraints on classes. Distinguished by its finite axiomatization, it serves as a conservative extension of ZFC. Notably, Gödel employed this system to demonstrate the relative consistency of “the Axiom of Choice” and “the Continuum Hypothesis”.

MK Set Theory: Initially conceptualized by Wang Hao and subsequently formalized by Kelley and Morse. It adopts “class” as its foundational concept while embracing the existence of “proper classes” within an infinite axiomatic framework. This theory transcends both ZFC and NBG in expressive power, can establish consistency, and constitutes a proper extension of ZFC. Numerous mathematicians, including Mendelson, Monk, and Rubin, advocated its elegance and power, finding it more theoretically robust and practically applicable than its predecessors.

The following

Figure 1 shows the visualization of the relationships between ZFC, NBG, and MK set theories:

The appearance of axiomatic set theory avoids the known paradoxes of set theory and preserves the valuable contents of Cantor’s set theory. The axiomatic set theory provides a convenient and practical language and tools for mathematical research.

Developing alongside axiomatic set theory was formal mathematics [

20,

24,

43,

44,

45]. The background to the development of formal mathematics was the mathematical crisis that emerged in the 19th century, including the various paradoxes found in set theory and the questioning of the foundations of mathematics. Mathematicians realized that intuition and nonformal methods were insufficient to ensure mathematical rigor. At the same time, the development of logic, particularly the work of Russell in symbolic logic, provided the necessary tools for formalization. To resolve the logical paradoxes in Frege’s framework, Russell and Whitehead developed a new logical system that introduced the concept of “type”. This effort culminated in the publication of

Principia Mathematica [

21], which contains a thorough collection of various mathematical theorems. Gödel has remarked that as mathematics progresses towards increased precision, there will be a substantial amount of formalized mathematical work. It is possible to prove any mathematical theorem through the application of a small number of mechanized rules of inference. He identified

Principia Mathematica and “Zermelo-Fraenkel axiomatic set theory” as the two most comprehensive formal systems. Furthermore, Hilbert put forth a proposal for the advancement of diverse mathematical theories within the context of a formal system. He is credited with introducing the concept of “mathematical axiomatization”, which has led to his being regarded as the founder of the modern formalism. While Gödel’s First incompleteness theorem invalidates Hilbert’s proposed scheme, this does not diminish the significance of Hilbert’s contributions to the mechanization of mathematics.

The introduction of electronic computers in the 1940s made mathematical mechanization feasible. In 1950, Polish mathematician Tarski proposed an algorithm to prove or disprove theorems in elementary algebra and geometry, theoretically laying the foundation for mechanizing propositions in these areas [

46]. However, the algorithm’s complexity remained significant, even by modern computational standards. In 1954, logician Davis developed the first functional theorem-proving program using the tube computer “JOHNNIAC”, named in honor of von Neumann, to implement Presburger arithmetic. In 1959, Wang Hao created a mechanized approach that allowed the computer to prove hundreds of theorems in

Principia Mathematica in just nine minutes, making a notable impact on mathematics and logic for a period. Another important milestone was de Bruijn’s 1968 development of the computerized proof tool “Automath”, which eventually verified all the propositions in Landau’s

Foundations of Analysis.

The formalization method is a systematic approach in computer science using rigorous mathematical principles for specification, development, and verification of hardware and software systems [

47,

48,

49,

50]. The specification facilitates communication between designers and users, expressing the properties of the system. Verification assesses whether systems meet the required properties through techniques such as model check and theorem proving [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Model-checking validates properties via finite models using exhaustive search, while theorem-proving verifies systems by representing them as mathematical theorems using axioms and inference rules [

24,

43]. Theorem proving, central to mathematical mechanization, includes automatic theorem proving (ATP) and interactive theorem proving (ITP). It provides a rigorous logical language for mathematical definitions and proofs, verifying correctness computationally. Formal mathematics aims to formalize mathematical theories, verify theorem proving computationally, and establish formal libraries of definitions, theorems, and proofs, offering a new methodology for evaluating mathematical rigor [

47,

55,

56].

Currently, essential formal tools include Coq [

57,

58,

73], Isabelle/HOL [

59,

60,

61], Lean [

62,

63], Agda, Mizar [

64], etc. Coq is based on intuitionistic type theory and has been used to verify critical mathematical results such as “the Four-Colour Theorem” and “the Feit-Thompson Theorem”, while Isabelle/HOL is constructed on higher-order logic and has supported complex proofs such as “the Prime Number Distribution Theorem”. Lean, on the other hand, has rapidly gained popularity in the mathematical community thanks to its “Mathlib library”, which successfully formalizes advanced mathematical concepts such as graph theory. These tools have not only verified many classical mathematical results but also facilitated new mathematical discoveries. Formal tools have become an essential addition to modern mathematical research and education, providing unprecedented reliability of proofs and organization of mathematical knowledge [

46,

55,

56,

65,

66].

Formal mathematics is closely related to axiomatic set theory [

67,

68]. The axiomatic set theory provides the content of formalizations, and formalizations give the language and rules for expressing and manipulating that content [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Contemporary formal mathematical projects all rely on axiomatic set theory as their underlying theory to varying degrees [

78,

79]. The paper will detail each of the three axiomatic systems of axiomatic set theory and formalize them with Coq in the following sections.

2. Axiomatics of ZFC, NBG, and MK

This chapter discusses several major axiomatic set theories, including the background, development process, axiomatic content, characteristics of each, differences and connections between them.

2.1. ZFC Set Theory

2.1.1. From “Naive” to “Z” (1908)

Beginning in the 20th century, mathematicians began to seek an axiomatization of set theory to resolve the contradictions in naive set theory. In 1908 [

14], Ernst Zermelo proposed the first axiomatic system for set theory, which aimed to provide a solid foundation for set theory while avoiding paradoxes. Zermelo’s original system contained seven axioms: Axiom of Extensionality, Axiom of Empty Set, Axiom of Pairing , Axiom of Power Set, Axiom of Union, Axiom of Separation(finite form), Axiom of Choice and Axiom of Infinity. The detailed description of this version of the axioms is shown below:

-

Axiom of Extensionality: Two sets are equal if and only if they have exactly the same elements.

-

Axiom of Empty Set: There exists a set that contains no elements (the empty set).

-

Axiom of Pairing: For any two sets, there exists a set that contains exactly those two sets as its elements.

-

Axiom of Union: For any set of sets, there exists a set that contains all elements that belong to at least one set in the original collection.

-

Axiom of Power Set: For any set, there exists another set containing all possible subsets of the original set.

-

Axiom of Infinity: There exists an infinite set that contains the empty set and is closed under the operation of adding singleton sets.

-

Axiom of Separation: For any set and any “definite” property, there exists a subset containing exactly those elements that satisfy the property.

-

Axiom of Choice: For any collection of non-empty sets, it is possible to select one element from each set to form a new set.

This version marked the first axiomatic formulation of set theory. A distinctive feature was its formulation of “the Axiom of Separation” : Zermelo’s original separation axiom relied on the vague notion of a “definite property”, a concept he failed to define rigorously. The system incorporated “the Axiom of Choice”, though its inclusion was contentious even at the time due to its non-constructive nature. Separately, the absence of “the Axiom of Replacement” critically hindered the theory’s ability to formalize transfinite ordinals and build robust hierarchies of infinite sets.

2.1.2. From “Z” to “ZF” (1922-1923)

Following the revelation of logical deficiencies in Zermelo’s original axiomatic system, Fraenkel and Skolem independently proposed systematic refinements between 1922 and 1923, laying the foundation for the modern ZF (Zermelo-Fraenkel) framework [

10,

19,

25,

80]. Their contributions centred on three pivotal advancements: First, they rigorously replaced Zermelo’s ambiguous notion of “definite properties” with formalized “first-order logical formulas”, resolving semantic vagueness in axiom formulation. Second, Fraenkel introduced “the Axiom Schema of Replacement”, dramatically expanding the system’s constructive power and enabling rigorous definitions of transfinite ordinals and cardinals. Finally, they enhanced the system’s formal precision by reworking “the Axiom of Separation” into a formula-dependent “axiom schema”. The detailed description of this version of the axioms is shown below:

-

Axiom of Extensionality: Two sets are equal if and only if they have the same elements.

-

Axiom of Empty Set: There exists a set with no elements.

-

Axiom of Pairing: For any two sets, there exists a set containing exactly these two sets as its elements.

-

Axiom of Union: For any set of sets, there exists a set containing precisely all elements of those sets.

-

Axiom of Power Set: For any set, there exists a set containing all its subsets.

-

Axiom Schema of Separation: For any set and any first-order formula, there exists a set containing exactly those elements of the original set that satisfy the formula.

For any formula with free variables:

-

Axiom Schema of Replacement: If a first-order formula defines a function on a set, then the image of that set under the function is also a set.

For any formula that represents a function:

-

Axiom of Infinity: There exists an infinite set containing the empty set and closed under the successor operation.

Note: At this stage, “the Axiom of Choice” was considered separately from the basic ZF system.

-

Axiom of Choice: For any set of non-empty sets, there exists a function that selects one element from each set.

This version marked the first complete first-order axiomatization of set theory. By employing infinite axiom schemata (each tied to a first-order formula), the system gained the capacity to formalize transfinite recursion, large cardinals, and other advanced set-theoretic constructs, establishing a robust logical foundation for modern mathematical research.

2.1.3. von Neumann’s Foundational Contributions (1925–1929)

Between 1925 and 1929, von Neumann revolutionized set theory by addressing critical gaps in the ZF system’s logical foundations and structural hierarchy [

81]. He introduced “the Axiom of Regularity”, which prohibits infinite descending membership chains (

) and ensures the well-foundedness of all sets, thereby eliminating paradox-prone constructs like self-containing sets (

).

Concurrently, he redefined ordinal numbers as well-ordered transitive sets (), (), and formalized the cumulative hierarchy (), a universe constructed recursively by (). This framework stratified the set-theoretic universe into ordinal-indexed levels, rigorously excluding contradictions from impredicative definitions. Von Neumann’s work not only solidified the logical purity of ZF but also laid the structural groundwork for later breakthroughs like Gödel’s and Cohen’s work on “the Continuum Hypothesis” and so on.

2.1.4. From “ZF” to “ZFC” (1930s-1940s)

By the 1930s, the Zermelo-Fraenkel (ZF) axioms combined with the Axiom of Choice (AC) solidified into the Zermelo-Fraenkel-Choice (ZFC) system, which became widely accepted as the standard foundational framework for set theory and mathematics. Key developments during this period included:

Standardization of Axiomatic Formulations: Consensus emerged on the precise first-order logical formulations of all axioms, notably refining “the Axiom Schema of Separation”and “the Axiom Schema of Replacement” to eliminate earlier ambiguities like Zermelo’s vague “definite properties.”

Equivalents of “the Axiom of Choice”: AC’s independence spurred proofs of its equivalence to principles such as “Well-Ordering Theorem”, “Zorn’s Lemma”, and “Tychonoff’s Theorem”, cementing AC’s utility across diverse mathematical fields.

Metamathematical Breakthroughs: Gödel’s proof of the relative consistency of ZFC with “the Continuum Hypothesis” shows that if ZF is consistent, so is ZFC plus “the Continuum Hypothesis”.

The detailed description of this version of the axioms is shown below:

-

Axiom of Extensionality: Two sets are equal if and only if they have exactly the same elements.

-

Axiom of Empty Set: There exists a set that contains no elements (the empty set).

-

Axiom of Pairing: For any two sets, there exists a set that contains exactly those two sets as its elements.

-

Axiom of Union: For any set of sets, there exists a set that contains all elements that belong to at least one set in the original collection.

-

Axiom of Power Set: For any set, there exists another set containing all possible subsets of the original set.

-

Axiom of Infinity: There exists an infinite set that contains the empty set and is closed under the successor operation.

-

Axiom Schema of Separation: For any set and any first-order formula, there exists a subset containing exactly those elements that satisfy the formula.

-

Axiom Schema of Replacement: If a first-order formula defines a function-like relation, then the image of any set under this relation is also a set.

-

Axiom of Regularity: Every non-empty set contains an element that is disjoint from it.

-

Axiom of Choice: For any collection of non-empty sets, there exists a function that selects exactly one element from each set.

At this stage, ZFC became the dominant system of mathematical foundations. “The Axiom of Choice” was widely accepted, and although some controversy remained, its irreplaceability in proving the existence of theorems (such as “the Hahn-Barnach Theorem”) led to its widespread adoption.

Since the 1950s, the ZFC axiomatic system has undergone profound metamathematical refinement and interdisciplinary integration while retaining its foundational stability [

19,

80]. In 1963, Cohen’s invention of “forcing” demonstrated the independence of “the Continuum Hypothesis”from ZFC, ushering in a new era in the study of axiomatic independence. This breakthrough revealed ZFC’s inherent limitations, that is, its inability to prove“the Continuum Hypothesis”, the existence of large cardinals and other pivotal propositions. In some respects, these insights into ZFC’s limitations have also contributed to the progress of mathematics and enriched the field of set theory research [

13].

2.2. NBG Set Theory

2.2.1. Foundational Work by von Neumann (1925-1928)

As with ZFC, NBG axiomatic set theory was developed at the beginning of the 20th century to resolve the paradoxical crisis. The first phase of the NBG axiom system began with von Neumann’s foundational work between 1925 and 1928 [

26,

27]. Instead of taking sets with membership relation as primitive, von Neumann used two types of functions as the basic objects of his theory, where

Rather than writing for membership, von Neumann used function application notation. If A is a function and x is an argument, A(x) represented the “value” of A at x. Von Neumann allowed operations on classes (functions of second type) through:

Domain operations: Defining operations that modified the domains of functions.

Logical operations: Using logical conditions to define new functions.

Function composition: These could not be arguments to other functions.

A fundamental innovation was introduced in set theory: the introduction of “classes”. In von Neumann’s system, “the class of all sets” or “the class of all ordinals” were introduced to handle objects that are too large to be sets. This approach allowed mathematicians to work with these important classes without running into contradictions.

The key advantage of this first phase was that it provided a coherent framework for dealing with large classes in a way that avoided the paradoxes while maintaining much of the expressive power needed for mathematical foundations. This work represented a significant alternative approach to the ZFC system that was developing around the same time.

Von Neumann’s original formulation was more syntactic, focusing on formulas that define classes rather than treating classes as full-fledged objects. von Neumann’s formulation was technically complex and used notation and terminology that differed significantly from modern presentations. In addition, this system contained more than 20 axioms with some redundancy, and some can be merged or simplified.

2.2.2. Modified and Developed Work by Bernays (1930s)

Bernays made significant contributions to refining von Neumann’s system during the 1930s [

28,

29,

30], creating what would initially be called “Bernays Set Theory” before later becoming part of NBG. Bernays’ key contributions included:

Reformulation with Standard Notation: Bernays abandoned von Neumann’s functional approach in favor of a more accessible formulation using the standard membership relation (∈)

Explicit Treatment of Classes: While von Neumann’s approach treated classes somewhat implicitly, Bernays made classes explicit objects in the theory.

Axiom Schema of Class Comprehension: Allowing classes to be defined through first-order formulas.

Simplification of the Axiom System: Bernays created a more elegant and streamlined system with fewer and clearer axioms.

Conservative Extension: He demonstrated that his theory was a conservative extension of ZF, meaning that any theorem about sets provable in his system was also provable in ZF.

Bernays’ version was significantly more approachable for mathematicians and laid the groundwork for Gödel’s later refinements that would complete the NBG system.

2.2.3. Simplified and Completed Work by Gödel (1940s)

Gödel proposed the complete structure of NBG [

31,

32,

33]. He retained the core ideas of Berners and made the system more straightforward and more practical with the following key innovations:

Axioms of “the Existence of Classes”: Instead of using a single axiom schema, Gödel introduced a finite list of specific axioms that precisely determined which formulas could define classes.

Conservative Extension: The proof of “NBG is a conservative extension of ZF” was strictly provided.

Introducing “the Global Axiom of Choice”: This is a very strong form of the axiom of choice, since it provides for the simultaneous choice, by a single relation, of an element from each set of the universe under consideration.

The detailed description of the final version of the NBG axioms is shown below, where the symbols are selected to be consistent with those in the original work:

Group A

-

Axiom of Class Inclusion: Every set is a class.

-

Axiom of Set Membership: Every class which is a member of some class is a set.

-

Axiom of Extensionality: Two classes are equal if and only if they have exactly the same elements.

-

Axiom of Pairing: For any sets x and y, there exists a set containing exactly x and y as its elements.

Group B

-

Axiom of Membership Relation: There exists a class that contains all ordered pairs where the first element is a member of the second.

-

Axiom of Intersection: For any two classes, there exists a class containing exactly the elements common to both.

-

Axiom of Complement: For any class, there exists another class containing exactly the elements not in the first class.

-

Axiom of Domain: For any class, there exists a class containing exactly those elements that appear as the second component of some ordered pair in the original class.

-

Axiom of Direct Product: For any class A, there exists a class containing all ordered pairs whose second component is in A.

-

Axiom of Inversion: For any class of ordered pairs, there exists a class containing the same pairs with components reversed.

-

Axiom of Triple Permutation (Cyclic): For any class of ordered triples, there exists a class containing the same triples with a cyclic permutation.

-

Axiom of Triple Permutation (Transposition): For any class of ordered triples, there exists a class containing the same triples with the second and third components swapped.

Group C

-

Axiom of Infinity: There exists a non-empty set such that for every element, there is another element of which it is a proper subset.

-

Axiom of Sum Set: For any set, there exists a set that includes the union of all elements of the original set.

-

Axiom of Power Set: For any set, there exists a set containing all possible subsets of the original set.

-

Axiom of Substitution: For any set and any single-valued relation, there exists a set containing exactly the images of elements of the original set under that relation.

Group D

-

Axiom of Regularity: Any non-empty class has some element with which it has no members in common.

Group E

NBG is widely used in the study of the foundations of mathematics, especially in the study of independence, which results in large bases and set theory. It provides a tool that allows mathematicians to discuss concepts difficult to express in ZFC more directly.

2.3. MK Set Theory

2.3.1. Development of MK

The previous subsection stated that NBG introduced the notion of class, further enhancing the expressive power of set theory. While NBG set theory restricted the bound variables in the formula appearing in the axioms to range over sets alone, Morse–Kelley set theory allowed these bound variables to range over proper classes as well as sets, as first suggested by Quine in 1940 for his system ML [

36,

37,

38,

39]. After that, the idea of the Morse-Kelley axiomatic set theory was first proposed by Wang Hao [

12]. Kelley and Morse officially published their own versions in 1955 [

34] and 1965 [

35], respectively. Kelley explicitly stated in his paper that this axiomatic system is closer to the NBG system systematically described by Gödel. The system of Morse’s is equivalent to Kelley’s, but formulated in an idiosyncratic formal language rather than, as is done here, in standard first-order logic. Now, when we talk about MK axiomatic set theory, we generally mean Kelly’s version of it, which was in an appendix of his textbook

General Topology.

2.3.2. Axioms in MK

As described in that book, “constructing ordinals and cardinals, defining nonnegative integers and proving Peano’s axioms as theorems simultaneously”. Moreover, real numbers can also be constructed based on the facts that “the class of integers is a set” and “it is possible to define a function on the integers using induction” as well as the Peano’s axioms and the axiom of infinity. From Kelley’s point of view, the axiom system with a finite number of axioms is discarded. The whole theory is constructed based on eight axioms and an axiomatic schema, which means all statements in some specified form are recognised as axioms. Under this axiomatised system, a mathematical foundation that avoids obvious paradoxes can be established quickly and efficiently. This axiomatic system admits the existence of classes wider than sets and does not contradict the ZFC and NBG axiomatic systems. The axioms in MK are as follows:

-

Definition of Set:x is a set if, for some y, .

-

I. Axiom of Extent: For each x and each y, if and only if for each z, when and only when .

-

II. Axiom Schema of Classification: For each formula A and variables , , if if and only if is a set and B (where B is obtained from A by replacing each occurrence of with , provided does not appear bound in A).

-

III. Axiom of Subsets: If x is a set, there exists a set y such that for each z, if , then .

-

IV. Axiom of Union: If x and y are both sets, then is a set.

-

V. Axiom of Substitution: If F is a function and domain F is a set, then range F is a set.

-

VI. Axiom of Amalgamation: If x is a set, then is a set.

-

VII. Axiom of Regularity: If there is a member y of x such that .

-

VIII. Axiom of Infinity: There exists a set y, such that and whenever .

-

IX. Axiom of Choice: There exists a choice function c whose domain is the class of all non-empty sets.

It is worth pointing out that the objects appearing in the above axioms are “classes”, if not otherwise stated. Unlike NBG, MK set theory allows for bound variables in formulas appearing in “the axiom schema of classification” to quantify both sets and classes. This property allows MK to define classes that could not be described in NBG and thus have greater expressive power. By enabling the quantification of class variables, MK has the properties of second-order logic. This allows certain mathematical concepts that need to be expressed in second-order logic to be handled more naturally in MK [

82,

83].

2.4. Relationships and Comparative Analysis of Three Systems

The common goal of ZFC, NBG and MK is to provide a consistent and robust foundation for mathematics, avoiding paradoxes through an axiomatic approach. Although described in slightly different ways, they are highly consistent in their core axioms, such as “Axiom of Extension”, “Axiom of Infinity”, “`Axiom of Regularity” [

14,

15,

31,

34].

Although agreeing on core axioms and foundational goals, ZFC, NBG, and MK set theory differ significantly in their expressive power, that is, the range of mathematical propositions that can be formally described and proved. These differences are mainly in the way to handle classes, their quantification capabilities, and the formalization of higher-order mathematical objects. The ZFC system, as a standard framework for set theory, is based on first-order logic and quantifies only over “sets”. Its axioms ensure the construction and manipulation of sets, but cannot directly refer to objects such as “the totality of all sets”, which are beyond the scope of sets. This limitation stimulated the development of class theory. The NBG system introduces “classes” into its structure. The main advantage of NBG is that it generates classes through finite axioms while maintaining conservativity over ZFC theoretic statements, thus avoiding new risks. The MK system, extended by Morse and Kelley, allows quantification over classes, allowing higher-order propositions such as “there exists a class that satisfies a certain property”. This breakthrough allows MK to define more complex structures such as “classes of classes”.

The key difference between them lies in how sets and classes are constructed by axioms as well as the restricting comprehension of sets. In the language of ZFC, classes are not objects that can be discussed directly. NBG allows only the formation of finitely many classes from sets and formulas that do not quantify classes. In contrast, MK can fully quantify classes in “Axiom Schema of Classification” and generate new classes from them.:

Axiom Schema Separation in ZFC: For any first-order formula and any set A, there exists a set

Axioms of “the Existence of Classes” in NBG: For any first-order formula

that does not include quantification over class variables, there exists a class

(This proposition has transformed into a metatheory proved in Gödel’s version [

31]).

Axiom Schema of Classification in MK: For any first-order formula (which may include quantification over class variables), there exists a class

From the above, it can be further concluded that the famous “Russell paradox” is handled differently in each set theory:

In ZFC: The construction of is prevented through its “Axiom Schema Separation”, which requires that we must always start with an existing set and separate from it: .

In NBG: The Russell class becomes being a legitimate class in NBG. However, R itself is a class that is restricted to be a member of a class.

In MK: let . By by “Axiom Schema of Classification”, if and only if and R is a set. It follows that R is not a set. Observe that if the classifier axiom does not contain “is a set qualification ”, then an outright contradiction would result.

In practical application, the three set theories form a complementary ecosystem with distinct strengths. ZFC serves as the standard foundation for mainstream mathematics, offering sufficient power for most mathematical disciplines while maintaining relative simplicity, making it the preferred system for working mathematicians in fields from analysis to algebra. NBG, on the other hand, provides significant advantages in metamathematics and formal logic due to its finite axiomatization. Its convenient class notation, without adding complexity, makes mathematicians, researchers, and students interested in set theory and its applications feel facilitated in their work. With its substantially greater expressive power, MK excels in advanced metamathematical investigations, particularly when studying formal truth predicates, consistency statements, and theoretical computer science problems involving higher-order reflection principles. However, this power comes at the cost of greater complexity, limiting its everyday use primarily to mathematical logic and set theory research specialists who need to handle substantial mathematical structures or make statements about the entire set-theoretic hierarchy that exceed the expressive capabilities of the more economical systems. The following

Table 1 summarizes the differences between the three set theories:

3. Formalization Methodology and Coq

In this section, a brief introduction to the formalization methodology and Coq proof assistant will be proposed, which provides foundational support for the formalization of set theory.

3.1. Formalization Methodology

Formalization methodology constitutes a systematic framework in computer science rooted in rigorous mathematical principles aimed at specifying, developing, and verifying hardware and software systems. Central to this approach is a specification, which functions as a structured communication protocol between system designers and users, formally defining a system’s intended behaviors and constraints through mathematical languages [

47,

56]. These specifications are foundational blueprints, ensuring clarity and precision throughout the development lifecycle.

Verification employs mathematical methods to rigorously evaluate whether a system adheres to its specifications, primarily through two complementary techniques:

model checking and

theorem proving [

47]. Model checking operates by constructing finite-state representations of a system and exhaustively verifying logical assertions against these models. In contrast, theorem proving treats system correctness as a mathematical proposition, deriving proofs through axioms and inference rules to validate properties [

66].

The field of theorem proving, a cornerstone of mathematical mechanization, encompasses automated and interactive paradigms. Automatic theorem proving (ATP) relies on algorithms to autonomously generate proofs within predefined logical frameworks, while interactive theorem proving (ITP) combines human expertise with computational tools to guide and validate proof construction step-by-step [

47,

48]. These methodologies collectively enable the formalization of mathematical theories into computer-verifiable formats, creating structured libraries of definitions, theorems, and proofs [

47,

49].

Formal mathematics, underpinned by such frameworks, redefines mathematical rigor by integrating computational objectivity. Computer-aided verification enhances reproducibility and identifies subtle logical inconsistencies that traditional peer review might overlook, establishing new standards for certainty in mathematical discourse [

50]. For instance, formal tools can systematically trace dependencies between axioms and theorems, offering unprecedented transparency in complex proofs. This paradigm shift positions formalization not merely as a technical tool but as a transformative methodology for advancing theoretical and applied mathematics [

84,

85,

86].

3.2. Advances in Formal Verification

The evolution of computer-assisted proof systems has enabled the rigorous formal verification of historically significant mathematical theorems [

87,

88,

89,

90,

91]. These achievements highlight the growing synergy between computational methods and foundational mathematics, reshaping standards of proof rigor and reproducibility. Formal verification has yielded numerous seminal results, including the degree to which the:

Four Color Theorem (2005 [92]): Gonthier’s Coq-based formalization resolved decades of controversy stemming from Appel and Haken’s 1976 computer-assisted proof, which faced skepticism due to its opaque algorithmic approach. By contrast, Gonthier’s machine-verified work established this theorem as one of the most thoroughly scrutinized results in mathematics.

Feit-Thompson (Odd Order) Theorem (2012 [93]): A collaborative effort led by Gonthier culminated in a six-year Coq formalization, comprising 150,000 lines of code, 4,000 definitions, and 13,000 lemmas. This project exemplified the scalability of interactive theorem provers in addressing complex geometric-topological constructs.

Kepler Conjecture (2015 [94]):Hales and collaborators completed the Flyspeck project, formalizing the proof of this centuries-old optimization problem. The endeavor underscored the utility of theorem provers in resolving intractable combinatorial arguments.

3.3. Coq

The development of mechanical proving systems necessitates careful selection of theorem provers, a decision significantly influenced by evolving advancements in logic, computer science, and technological infrastructure [

58,

73,

95]. Modern theorem proving ecosystems feature diverse implementations such as Coq, Isabelle/HOL, Mizar, and Lean, each distinguished by foundational frameworks (type theory or set theory, classical logic or intuitionistic logic) and specialized application domains [

59,

60,

61,

62]. Among these, Coq has emerged as a preeminent interactive theorem prover in formal verification research [

63,

64,

96].

The theoretical underpinnings of Coq trace back to the Calculus of Constructions (CC) proposed by Coquand and Huet in 1984, which synthesized Martin-Löf type theory with the Automath framework, establishing the initial architecture for type verification of

-expressions. Subsequent evolution occurred through Mohring’s collaboration with Coquand, culminating in 1988 with the Calculus of Inductive Constructions (CIC) that expanded the system’s logical expressiveness [

97,

98,

99]. The 1991 release of Coq v5.6 marked a pivotal advancement, introducing a formal language for mathematical specification. This version significantly enhanced usability and collaborative potential [

100,

101,

102,

103,

104]. The publication of the seminal monograph

Coq’Art: The Calculus of Inductive Constructions in 2004 substantially accelerated Coq’s adoption within formal methods communities [

57].

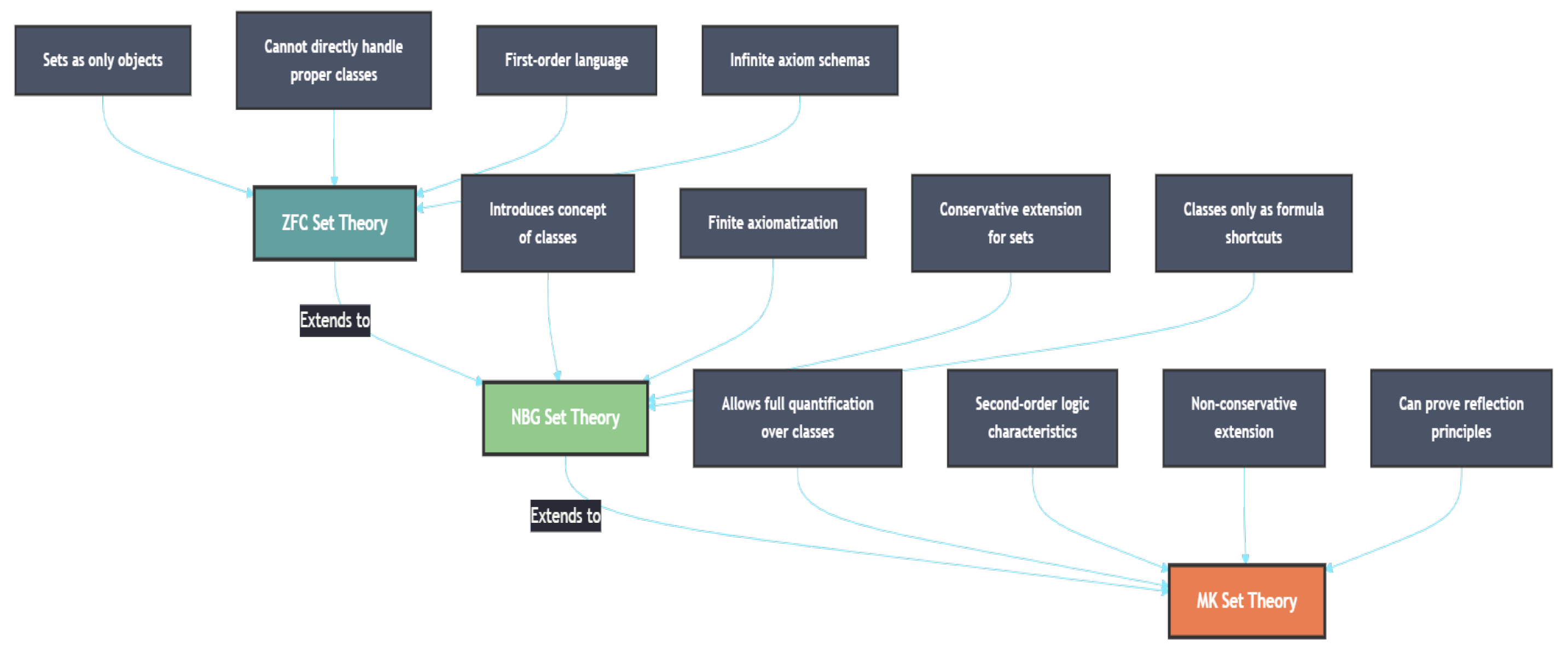

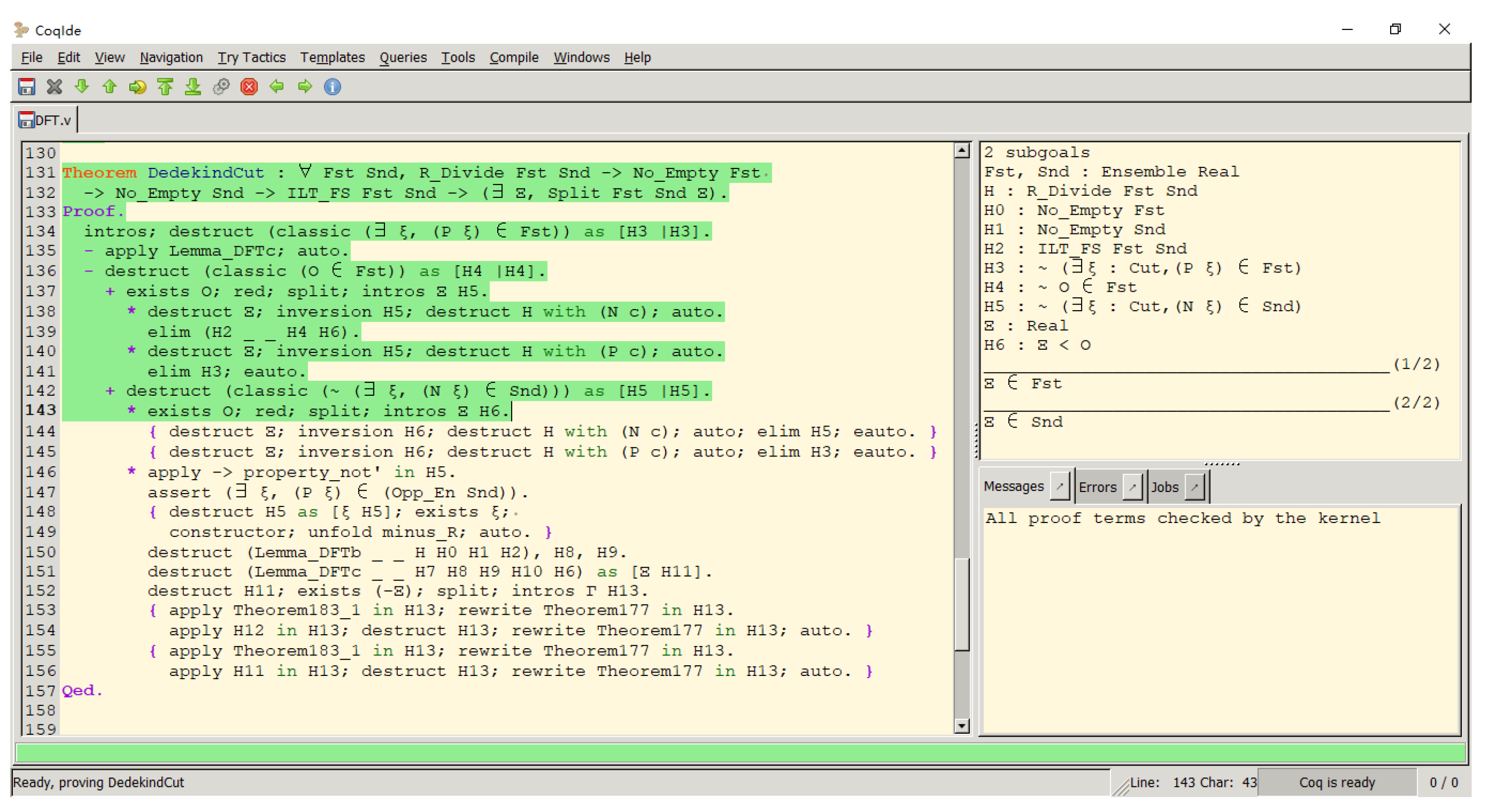

CoqIDE’s interactive proving environment allows users to write proofs on the left side of the IDE while dynamically tracking proof states (goals and assumptions) in the upper-right panel [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111]. The lower-right section provides real-time feedback on proof progress, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

This bidirectional interface architecture supports guided theorem development through continuous feedback, enabling users to maintain strict correspondence between proof objectives and tactical implementations. The visual separation of code entry, proof state visualization, and verification diagnostics optimizes the formalization workflow for complex mathematical proofs.

The use of Coq primarily revolves around definitions, proofs, and program verification. In terms of syntax, Coq has two main languages: Gallina (the specification language) for defining functions and properties, and Ltac (the tactics language) for constructing proofs. Basic definitions use the keywords Definition, Inductive, and Fixpoint, while axioms and theorems are declared using Axiom, Theorem, Lemma, or Corollary. Each proof begins with Proof. and ends with Qed.

Coq features numerous tactics and commands essential for formal theorem proving in its interactive proof assistant environment [

112]. The

Table 2 presents a concise overview of the most fundamental commands used to construct and manipulate proofs within the Coq system. More details about the Coq system can be obtained from the Coq reference manual.

Table 2.

Tactics and command in Coq.

Table 2.

Tactics and command in Coq.

| Command |

Syntax |

Description |

| intros |

intros x y z |

Moves hypotheses into context with names x, y, z |

| apply |

apply H |

Uses H to match and prove current goal |

| simpl |

simpl |

Performs computation in goal |

| rewrite |

rewrite H |

Substitutes using equation H |

| destruct |

destruct H |

Case analysis on inductive type H |

| induction |

induction n |

Proof by induction on n |

| reflexivity |

reflexivity |

Proves equality by term identity |

| unfold |

unfold def |

Expands definition of def |

| auto |

auto |

Automatic proof search |

| exact |

exact H |

Uses H that exactly matches goal |

4. Formalization of Three Axiomatic Systems in Coq

In this section, related work on formalization of three set theories will be introduced, respectively. Then, the corresponding axiomatic frameworks will be formalized using Coq, following which we will further interpret their strengths and limitations through code.

4.1. Formalization of ZFC

ZFC Set theory has become a focal point for formalization efforts due to its unique position in mathematical foundations. Its universality as the standard foundation of modern mathematics allows for the unified expression of virtually all mathematical theories, from analysis to algebraic structures, making it an ideal starting point for formalizing the entire mathematical corpus. The widespread acceptance of ZFC across academic disciplines has created a consensus platform where mathematicians, logicians, and computer scientists recognize its value as a formal foundation [

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119]. In addition, the structural characteristics of ZFC’s relatively concise axiom system, which has both powerful expressiveness for handling infinite sets and rigorous safeguards against paradoxes, provide a clear framework for formalization implementation.

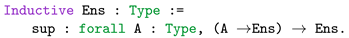

Werner presented two mutual encodings, respectively of the calculus of inductive constructions in Zermelo-Frankel set theory and the opposite way and then achieved an encoding into Coq as early as 1996, which has become a guide for many formalization researchers [

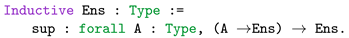

113]. In Werner’s formalization, sets are defined by the following induction: 1

This definition indicates that a set is composed of two parts: A type “A” (as a set of indices) and a function from “A” to Ens that maps each index to a set. The intuitive understanding of this definition is the set “sup A (A →Ens)” contains all elements of the form (A →Ens), where a takes all values in type “A”. On top of that, some basic definitions, such as “empty set”, “pair”, “union”, in ZFC set theory are represented using dependent types. In this formalization, the axioms of ZFC are not introduced as axioms but formalized through constructive definitions in type theory, and it is shown that these constructions satisfy the axioms. The following codes propose the formalization of “the axioms of the empty set” and “The separation axioms”. 1

The merits of this approach are manifold. It capitalizes on the constructive properties of type theory and provides a concrete realization of the axioms of set theory. Moreover, it ensures system consistency through formal proofs. The aforementioned example illustrates one instance of the formalized style. In a similar vein, he has formalized a comprehensive framework encompassing the axioms of ZFC set theory, ordinal numbers, cardinal numbers, and associated theories.

Another piece of work of very high theoretical value is prensented by Bruno [

114], who explores the formalization of set-theoretical models for various types of theories in the Calculus of Constructions family. The authors axiomatize set theories (ZF possibly with inaccessible cardinals, and HF, the theory of hereditarily finite sets) to develop a formal model of “the Calculus of Inductive Constructions”, proving soundness for multiple models including those with infinite universe hierarchies. This work provides significant insights into the theoretical foundations of Coq and its relationship to set theory.

In recent years, a system has been developed in “the Laboratory of Programming Systems” at Saarland University to formalize axiomatic set theory [

115]. The laboratory, which is named “Programming Systems” at Saarland University, has developed a system in which Kaiser, a member of the laboratory, formalizes the essential content of the “Tarski-Grothendieck set theory (ZFC with Grothendieck universes)” in his master’s thesis in 2012 by Coq and realizes the axiomatic set theory of pairs, functions, and finite ordinals from the axiomatic method. In addition, started from axioms for intuitionistic ZF set theory without axiom of infinity, an epsilon recursion principle is proven. The corresponding results have been formalized in Coq. Three forms of “axiom of replacement” (map replacement, total replacement and partial replacement). It is proved that partial replacement is equivalent to total replacement and separation. Also, total replacement is equivalent to map replacement and having a description operator.

Zhang [

120] implemented formal verification of the entire book in Coq using Enderton’s book Elements of Set Theory [

9] as a theoretical basis, and this work enabled the formal construction of ZFC axiomatic sets.

In addition, Various proof assistants have implemented formalizations of set theory. In the Mizar system [

121], the Tarski-Grothendieck axioms [

122], which is an extension of ZFC, are employed to prove the induction property for

demonstrated by Bancerek [

123]. Alejandro presented his formal work on ZFC set theory in Agda in 2017 and propose that it is possible to prove “the Principle of Mathematical Induction” on

just using the axioms in Z, not needing to resort to ZFC [

124]. A prover for ZFC in Coq has been developed to facilitate scenario teaching [

119]. The first-order logical reasoning system and the axiomatic set theory ZFC have been formalized, and several automated proof tactics specific to reasoning rules have been developed. These implementations demonstrate how different formal verification systems have approached the foundational challenge of representing set theory within computational frameworks. At the end of this section, we will give the complete coq code for all the axioms of ZFC. 1

4.2. Formalization of NBG

Compared to ZFC, NBG’s formalization efforts are comparatively deficient. A portion of the formalization process is conducted at the theoretical level, not through formal tools. A new clausal version of NGB set theory is presented in [

125], where a semiautomated proof that the composition of homomorphisms is a homomorphism is given to solve the problem in [

126]. A formalization of NBG set theory called “NBG

*” is presented in [

127], where the underlying logic of NBG, ordinary frst-order logic, is replaced with “Partial First-Order logic”and an axiomatization of “NBG

*” as well as the term constructors for function application are proposed. In this formalization, “NBG

*” has been proved that is has the same expressive power as ZF. In [

128], a Set of metrics for measuring interestingness of NBG’s theorems are proposed by using forward reasoning approach. Until now, there has not been much work on the formalization of NBG systems with tools such as Isabelle, Coq, etc. [

129] is one of them, in which NBG Set theory as presented in [

39] based on Isabelle’s “Higher Order Logic (HOL)” is formalized, including some basic axioms, definitions and theorems.

According to Gödel’s description in [

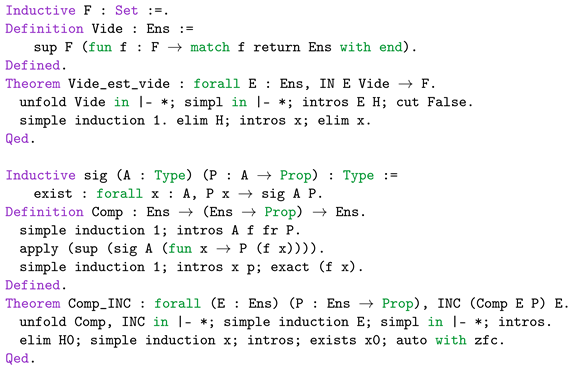

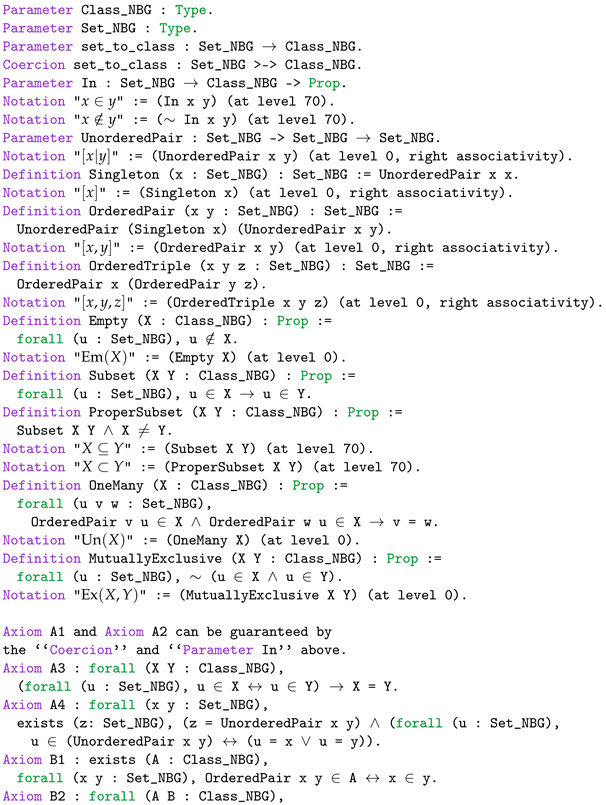

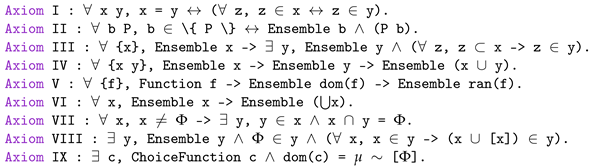

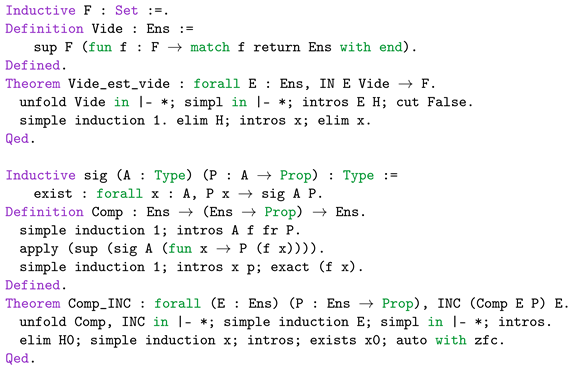

31], the entire axiomatic system of NBG is divided into five groups, of which group B is concerned with the existence of classes, which prescribe ways of constructing classes from known sets by means of eight formulas that do not quantify classes, but only sets. This is fundamental to the finiteness of the NBG system. In Gödel’s description, “sets” and “classes” are two primitive notions, with “∈” as the primitive binary predicate. “Every set is a class” and “every class which is a member of some class is a set” are guaranteed by the first two axioms. True to the original, we will complete the formalization of Gödel’s five groups of axioms using coq. 1

4.3. Formalization of MK

MK set theory is a further extension of NBG. It is most notably characterized by its “axiom scheme of classification”, which allows the quantification of class variables and further defines classes that cannot be defined in NBG, thus having greater expressive power. The development of the axiom system is based on eight axioms and one axiom scheme. In recent years, our team has been working on formalizing related mathematical theories in Coq [

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143]. In [

131]and [

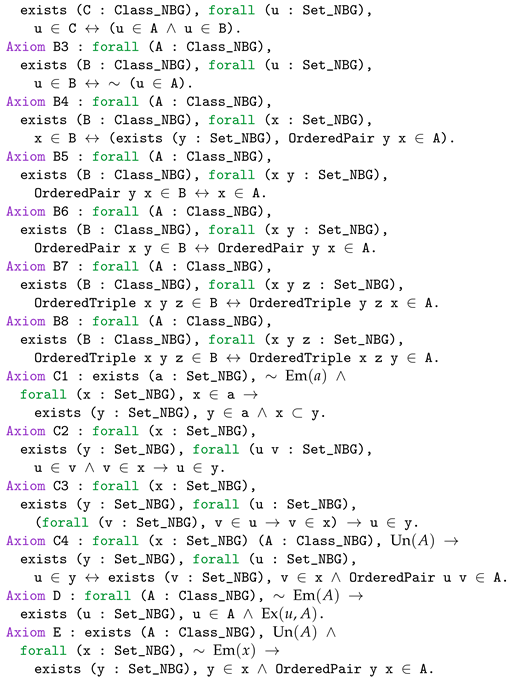

134], formalizations of the whole definitions in MK, including sets, functions, well-ordering, ordinal numbers, cardinal numbers, and all axioms, as well as theorems, are presented. Under this axiomatized system, a mathematical foundation that avoids apparent paradoxes can be established quickly and efficiently. The following code shows the corresponding formalization of primitive notions in MK.

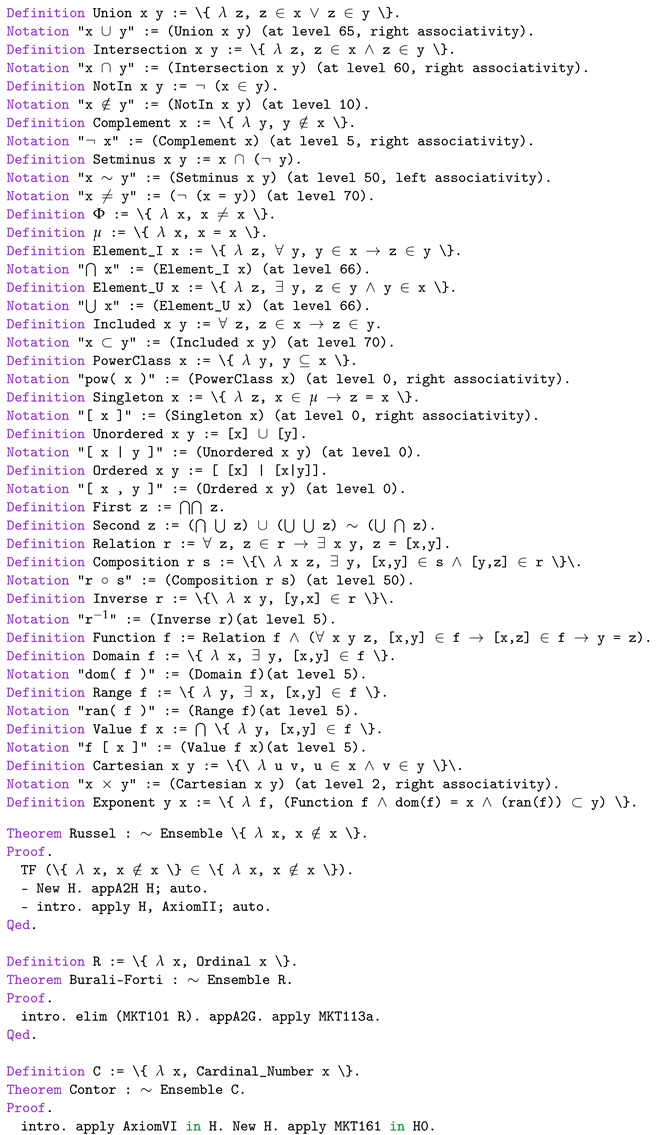

The class constructor “Classifier” is declared, which takes a predicate (about the properties of a class) and returns a class. This principle underlies the class construction in MK set theory, a framework that facilitates the construction of a class encompassing all objects satisfying a predicate P, for any predicate P. Based on the classifier, many important definitions can be be formalized as follows: 1

Due to space limitations, the code above only lists part of definitions in MK. Actually, We have implemented the formalization of MK, including ordinal number, integers, cardinal numbers, theorems and corresponding proofs. Now, the formalization of the eight axioms in the MK set theory is presented as follows: 1

Furthermore, the construction of MK set theory we formalized is free from “Russell’s paradox”, “Burali-Forti’s paradox” and “Cantor’s paradox”. 1

After the formalization of MK axiomatic set theory, related formalization work on “the foundations of analysis” [

134,

135,

136,

137,

138], “point set topology” [

140,

141], “propositional logic” [

142] and “end-extenstions of natural numbers” have been completed. Subsequently, we will systematically study and formalize the whole system of foundational principles of geometry, the functions of actual variables, logic, and a selection of practical applications of MK to engineering. Some results have already been achieved preliminarily.

4.4. Discussion on the Formalization of Three Set Theories

The three principal axiomatic systems of set theory, ZFC, NBG, and MK can be metaphorically interpreted as architectural spaces for mathematical construction, each offering distinct advantages and limitations in formalizing mathematical universes.

ZFC resembles a “lean” artisan toolkit, excelling in foundational precision but limited in handling ultra-large mathematical structures. Its preeminence in contemporary mathematics stems from its simplicity: it operates with a single type of object (sets) and avoids paradoxes through carefully designed axioms. However, this simplicity comes at the cost of reduced expressive power. For instance, ZFC cannot formally define a “class of all ordinals” within its object language, highlighting its constraints when dealing with higher-order concepts.

NBG extends ZFC by introducing proper classes, effectively adding an “attic” to the foundational workspace. This conservative extension transforms ZFC’s infinite axiom schema into a finite system, simplifying formalization while enabling limited class-based reasoning. Yet, when restricted to sets alone, NBG and ZFC prove equivalent theorems, which has led some scholars to view NBG as unnecessarily cumbersome. The contributions of Gödel and others in achieving this finite axiomatization remain a testament to their profound insight into set-theoretic foundations.

MK elevates this framework further, constructing a “skyscraper” of expressive power. Unlike NBG, MK permits quantification over classes, enabling the definition of new classes via arbitrary combinatorial formulas. This grants unparalleled flexibility in formalizing large-scale structures, but at a price: MK abandons finite axiomatization, reverting to an infinite axiom scheme. While MK’s full strength may exceed the needs of classical mathematics (where ZFC suffices), its potential for future foundational research remains an open and intriguing direction.

The formalizations of ZFC, NBG, and MK in proof assistants like Coq provide a concrete means to compare their strengths and weaknesses. These implementations verify their internal consistency and highlight practical trade-offs in usability, scalability, and expressive power. ZFC’s minimalism makes it a natural choice for most formalization efforts, while NBG’s layered structure offers organizational benefits. Although rarely employed in computational settings, MK represents a fascinating frontier for exploring the limits of formalized mathematics.

These systems form a spectrum balancing axiomatic economy, pragmatic utility, and theoretical ambition. ZFC remains the workhorse of modern mathematics, NBG provides a structured upgrade for class-based reasoning, and MK stands as a monument to the vast possibilities of foundational theory. As mathematical practice evolves—especially with advances in formal methods and computational tools—the interplay between these systems may yield new insights, reinforcing the enduring relevance of axiomatic set theory in shaping mathematics’ future.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we systematically study the development from simple set theory to axiomatic set theory and analyze the theoretical foundations, historical development, and expressiveness of the three major axiomatic set theory systems: ZFC, NBG, and MK. Through the comparative study, we find that these three set theories have their characteristics and complement each other: ZFC dominates the study of mathematical foundations with its simplicity; NBG extends the expressiveness by introducing the concept of“class” while retaining the advantages of finite axiomatic systems; MK further extends the expressiveness by allowing the definition of quantized classes but at the cost of giving up the finiteness of axiomatic systems. Formal methods, particularly the Coq proof assistant, provide a rigorous computer verification environment for these three theories. The formalization work we have done verifies the correctness of these theories and provides a reliable tool for further research and applications. Formalization verifies mathematics and is an important way of exploring and learning mathematics. Future development of formalization methods can be followed:

Improvement and integration of formalization libraries: Continue to improve the formalization libraries of ZFC, NBG, and MK in proof assistants such as Coq and promote interoperability between different formalization libraries.

Automation enhancement: Enhance proof automation capabilities, reduce the difficulty of formalization work, and make it more accessible to ordinary mathematicians.

Educational applications: Integrate formalization tools into mathematics education, especially set theory, to foster rigorous mathematical thinking and formalization skills.

Cross-system formalization: Establish a translation mechanism between different proof assistants (e.g., Coq, Isabelle/HOL, Lean, etc.) to facilitate collaboration and knowledge sharing in the formalization community.

Large language models (LLMs) and big data technologies are opening new possibilities for set theory research and formalization work: they can serve as “proof assistants” to help mathematicians generate proof drafts, suggest strategies, and identify potential errors—particularly valuable for complex set-theoretic proofs. These models can also lower the barrier to formalization by aiding in the translation of natural-language proofs into formal proofs [

144].

By leveraging big data techniques, researchers can construct knowledge graphs of set theory, mapping dependencies between theorems to uncover new research directions or simplify existing proofs. The integration of LLMs with symbolic reasoning may also facilitate breakthroughs in model discovery, counterexample construction, and independence proofs. Furthermore, building large-scale corpora of set-theoretic proofs—both formalized and in natural language—will provide a foundation for training more specialized mathematical AI models.

However, it is crucial to recognize the current limitations of LLMs in deep mathematical reasoning and their inability to fully replace formal verification systems in ensuring proof correctness. Therefore, a balanced approach—using LLMs as complementary tools alongside formal methods, rather than as complete substitutes—represents the most reasonable direction for progress.

Set theory, the foundation of modern mathematics, reflects mathematicians’ relentless pursuit of rigor and expressive power. The three axiomatic systems—ZFC, NBG, and MK—each with its own strengths collectively form a multi-layered framework for addressing fundamental mathematical questions. Formal verification tools provide unprecedented rigor in validating these theories, while large language model technologies open new possibilities for future research.

As mathematics and computer science continue to converge, axiomatic set theory will keep evolving, formal methods will become more widespread, and their integration will provide an even stronger foundation for mathematics. Future research should focus on refining the theories themselves and exploring their practical applications in mathematical practice and how emerging technologies can advance this ancient yet fundamental discipline.

Returning to the axiomatic roots of mathematics and rigorously verifying our knowledge systems through formal methods may be more crucial in this era of information explosion. This study represents but a small step toward this grand vision, and we look forward to more scholars joining this foundational work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and W.Y.; methodology, S.C. and W.Y.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C. and W.Y.; formal analysis, S.C. and W.Y.; investigation, S.C. and W.Y.; resources, S.C.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C.; supervision, W.Y.; project administration, S.C. and W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation (NNSF) of China under Grant No. 62476028.

Data Availability Statement

The source code referenced in this study is publicly available through the cited references in the manuscript. Our formalization of Morse-Kelley set theory has been published to the Coq Package Index (Rocq) to facilitate collaboration within the Coq community. These packages are accessible at the following URLs:

No additional datasets were generated during this study beyond what is publicly available in these repositories.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all researchers whose work has been cited in this review. We acknowledge their dedication, rigor, and creativity, without which this comprehensive review would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ZF |

Zermelo–Fraenkel |

| MK |

Morse–Kelley |

| NBG |

von Neumann-Bernays-Gödel |

References

- Katz, V.J. A History of Mathematics: An Introduction; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2009.

- Kline, M. Mathematical Thought From Ancient to Modern Times; Oxford Univ. Press: London, U.K., 1972.

- Aleksandrov, A.D.; Kolmogorov, A.N.; Lavrent’ev, M.A. Mathematics: Its Content, Methods, and Meaning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1963.

- Grattan-Guinness, I. Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Grattan-Guinness, I. From the Calculus to Set Theory, 1630–1910: An Introductory History; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1630.

- Grattan-Guinness, I. The Search for Mathematical Roots, 1870–1940: Logics, Set Theories and the Foundations of Mathematics From Cantor Through Russell to Gödel; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000.

- Cantor, G. Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1915.

- Li, W.L. An Introduction to History of Mathematics, 3rd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Enderton, H.B. Elements of Set Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1977.

- Fraenkel, A.A.; Bar-Hillel, Y.; Levy, A. Foundations of Set Theory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973.

- Morse, A.P. A Theory of Sets; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1965.

- Wang, H. On Zermelo’s and von Neumann’s axioms for set theory. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1949, 35, 150–155. [CrossRef]

- Jech, T. Set Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003.

- Zermelo, E. Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Mengenlehre I. Mathematische Annalen 65, 261-281, 1908.

- Hatcher, W. The Logical Foundations of Mathematics; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1982.

- Kunen, K. Set Theory: An Introduction to Independence Proofs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1980.

- Suppes, P. Axiomatic Set Theory; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1972.

- Tourlakis, G. Lectures in Logic and Set Theory, Vol. 2; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

- Fraenkel, A.A. Abstract Set Theory; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1966.

- Van Heijenoort, J. From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 1967.

- Russell, B.; Whitehead, A.N. Principia Mathematica; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, U.K., 1910.

- Frege, G. Begriffsschrift: Eine Der Arithmetischen Nachgebildete Formelsprache Des Reinen Denkens; Louis Nebert: Halle, Germany, 1879.

- Mendelson, E. Introduction to Mathematical Logic, 4th ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, U.K., 1997.

- Boole, G. An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which Are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2009.

- Bernays, P.; Fraenkel, A.A. Axiomatic Set Theory; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1958.

- von Neumann, J. Zur Einführung der transfiniten Zahlen. Acta Litt. Acad. Sc. Szeged X. 1, 199–208, 1923.

- von Neumann, J. Eine Axiomatisierung der Mengenlehre. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 154, 219–240, 1925.

- Bernays, P. A System of Axiomatic Set Theory—Part I. The Journal of Symbolic Logic 2, 65–77, 1937.

- Bernays, P. A System of Axiomatic Set Theory—Part II. The Journal of Symbolic Logic 6, 1–17, 1941.

- Bernays, P. Axiomatic Set Theory, 2nd Revised ed.; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Gödel, K. The Consistency of the Axiom of Choice and of the Generalized Continuum Hypothesis with the Axioms of Set Theory, Revised ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1940.

- Gödel, K. Collected Works, Volume 1: Publications 1929–1936; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1986.

- Gödel, K. Collected Works, Volume 2: Publications 1938–1974; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990.

- Kelley, J.L. General Topology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1955.

- Cohen, P. Set Theory and the Continuum Hypothesis; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Morse, A.P. A Theory of Sets; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965.

- Lemmon, E.J. Introduction to Axiomatic Set Theory; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1986.

- Lewis, D.K. Parts of Classes; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991.

- Mendelson, E. Introduction to Mathematical Logic; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1987.

- Monk, J.D. Introduction to Set Theory; Krieger: Malabar, FL, USA, 1980.

- Mostowski, A. Some impredicative definitions in the axiomatic set theory. Fundamenta Mathematicae 1950, 37, 111–124. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.E. Set Theory for the Mathematician; Holden Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1967.

- Davis, M. The Universal Computer: The Road From Leibniz to Turing; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Paulson, L.C. A machine-assisted proof of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems for the theory of hereditarily finite sets. Rev. Symbolic Log. 2014, 7, 484–498. [CrossRef]

- Paulson, L.C. A mechanised proof of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems using nominal Isabelle. J. Automated Reasoning 2015, 55, 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Tarski, A. A Decision Method for Elementary Algebra and Geometry; Univ. California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1951.

- Avigad, J. The mechanization of mathematics. Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 2018, 65, 681–690. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. Formalized mathematics. Technical Report 36, Turku Centre for Comput. Sci., Turku, Finland, 1996.

- Beeson, M.J. The mechanization of mathematics. In Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 77–134.

- Avigad, J.; Harrison, J. Formally verified mathematics. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.J.C.; Melham, T.F. Introduction to HOL: A Theorem-Proving Environment for Higher-Order Logic; Cambridge Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- Gordon, M.J.C. Mechanizing programming logics in higher order logic. In Current Trends in Hardware Verification and Automated Theorem Proving; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 387–439.

- Gordon, M.J.C. Why higher-order logic is a good formalism for specifying and verifying hardware. Technical Report UCAM-CL-TR-77, Dept. Computer Laboratory, Univ. Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K., 1985.

- Gordon, M.J.C. From LCF to HOL: A short history. In Proof, Language, and Interaction: Essays in Honour of Robin Milner; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 169–186.

- Chen, G.; Yu, L.Y.; Qiu, Z.Y. Logic-based formal verification methods: Progress and applications. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis 2016, 52, 363–373.

- Wang, J.; Zhan, N.J.; Feng, X.Y.; Liu, Z.M. An overview of formal methods. J. Softw. 2019, 30, 33–61.

- Bertot, Y.; Castéran, P. Interactive Theorem Proving and Program Development: Coq’Art: The Calculus of Inductive Constructions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004.

- Chlipala, A. Certified Programming With Dependent Types: A Pragmatic Introduction to the Coq Proof Assistant; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013.

- Nipkow, T.; Paulson, L.C.; Wenzel, M. Isabelle/HOL: A Proof Assistant for Higher-Order Logic; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002.

- Harrison, J. The HOL Light Theorem Prover. Available online: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~jrh13/hol-light/ (accessed on 2017).

- Harrison, J. The HOL Light System Reference. Available online: https://github.com/jrh13/hol-light/ (accessed on 2016).

- Avigad, J.; de Moura, L.; Kong, S. Theorem Proving in Lean (Release 3.23.0). Available online: https://leanprover.github.io(accessed on 2021).

- de Moura, L.; Kong, S.; Avigad, J.; Van Doorn, F.; von Raumer, J. The lean theorem prover (system description). In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Automated Deduction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 378–388.

- Bancerek, G.; Byliński, C.; Grabowski, A.; Korniłowicz, A.; Matuszewski, R.; Naumowicz, A.; Pąk, K.; Urban, J. Mizar: State-of-the-art and beyond. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Intell. Comput. Math.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 261–279.

- Hales, T.C. Formal proof. Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1370–1380.

- Wang, Z.M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.F. Automated theorem prover for pointer logic. J. Softw. 2009, 20, 2037–2050. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.J. Mathematics Mechanization; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2003.

- Wu, W.J. Review and prospect of research on mathematical mechanization. J. Syst. Sci. Math. Sci. 2008, 28, 898–904.

- De Bruijn, N.G. Checking mathematics with computer assistance. Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 1991, 38, 8–15.

- Milner, R. Implementation and applications of Scott’s logic for computable functions. In Proceedings of the ACM Conf. Proving Assertions Programs, 1972; pp. 1–6.

- Beeson, M. Mixing computations and proofs. J. Formalized Reasoning 2016, 9, 71–99.

- Nicely, T.R. How to make a Pentium divide by zero. IEEE Comput. 1994, 27, 101–102.

- Coq Develop. Team. The Coq Reference Manual (Version 8.9.1). Available online: https://coq.inria.fr/distrib/V8.9.1/refman/ (accessed on 2018).

- Klein, G.; Elphinstone, K.; Heiser, G.; Andronick, J.; Cock, D.; Derrin, P.; Elkaduwe, D.; Engelhardt, K.; Kolanski, R.; Norrish, M.; Sewell, T.; Tuch, H.; Winwood, S. SeL4: Formal verification of an OS kernel. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGOPS Symp. Oper. Syst. Princ. (SOSP), 2009; pp. 207–220.

- Choi, J.; Vijayaraghavan, M.; Sherman, B.; Chlipala, A. Kami: A platform for high-level parametric hardware specification and its modular verification. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2017, 1, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Bhargavan, K.; Delignat-Lavaud, A.; Fournet, C.; Gollamudi, A.; Gonthier, G.; Kobeissi, N.; Rastogi, A.; Sibut-Pinote, T.; Swamy, N.; Zanella-Beguelin, S. Short paper: Formal verification of smart contracts. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop Program. Lang. Anal. Secur., Vienna, Austria, 2016; pp. 91–96.

- Sun, T.; Yu, W. A formal verification framework for security issues of blockchain smart contracts. Electronics 2020, 9, 255. [CrossRef]

- Van Benthem Jutting, L.S. Checking Landau’s ’Grundlagen’ in the Automath System; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979.

- Brown, C.E. Faithful Reproductions of the Automath Landau Formalization. Available online: https://www.ps.uni-saarland.de/Publications/documents/Brown2011b.pdf (accessed on 2011).

- Devlin, K.J. The Joy of Sets: Fundamentals of Contemporary Set Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992.

- Landau, E. Foundations of Analysis: The Arithmetic of Whole, Rational, Irrational, and Complex Numbers, 3rd ed.; Chelsea: New York, NY, USA, 1966.

- Monk, J.D. Introduction to Set Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1969.

- Rubin, J.E. Set Theory for the Mathematician; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1967.

- Formalizing 100 Theorems. Available online: http://www.cs.ru.nl/~freek/100/ (accessed on Feb. 26, 2023).

- Archive of Formal Proofs. Available online: https://www.isa-afp.org/ (accessed on Mar. 19, 2004).

- TPChina, Theorem Proving Community of China. Available online: https://tpchina.github.io/ (accessed on Dec. 2021).

- Jiang, N.; Li, Q.A.; Wang, L.M. Survey on mechanized theorem proving. J. Softw. 2020, 31, 82–112.

- Castelvecchi, D. Mathematicians welcome computer-assisted proof in ’grand unification’ theory. Nature 2021, 595, 18–19. [CrossRef]

- Tao, T. Formalizing the Proof of PFR in Lean4 Using Blueprint: A Short Tour. Available online: https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2023/11/18/formalizing-the-proof-of-pfr-in-lean4-using-blueprint-a-short-tour/ (accessed on 2023).

- Harrison, J. Formalizing an analytic proof of the prime number theorem. J. Automated Reasoning 2009, 43, 243–261. [CrossRef]

- Avigad, J.; Hölzl, J.; Serafin, L. A formally verified proof of the central limit theorem. J. Automated Reasoning 2017, 59, 389–423. [CrossRef]

- Gonthier, G. Formal proof—The four-color theorem. Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1382–1393.

- Gonthier, G.; Asperti, A.; Avigad, J.; Bertot, Y.; Cohen, C.; Garillot, F.; Le Roux, S.; Mahboubi, A.; O’Connor, R.; Ould Biha, S.; Pasca, I.; Rideau, L.; Solovyev, A.; Tassi, E.; Théry, L. A machine-checked proof of the odd order theorem. In Proceedings of the Interact. Theorem Proving, Rennes, France, 2013; pp. 163–179.

- Hales, T.C.; Adams, M.; Bauer, G.; Dang, D.T.; Harrison, J.; Hoang, T.L.; Kaliszyk, C.; Magron, V.; McLaughlin, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Nipkow, T.; Obua, S.; Pleso, J.; Rute, J.; Solovyev, A.; Ta, A.H.T.; Tran, T.N.; Trieu, D.T.; Urban, J.; Vu, K.; Zumkeller, R. A formal proof of the Kepler conjecture. Forum Math., Pi 2017, 5, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, B.C.; Amorim, A.A.; Casinghino, C. Software Foundations (Version 6.1). Available online: https://softwarefoundations.cis.upenn.edu/ (accessed on 2021).

- Community, T.M. The lean mathematical library. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGPLAN Int. Conf. Certified Programs Proofs, 2020; pp. 367–381.

- Boyer, R. The QED manifesto. In Proceedings of the 12th Int. Conf. Automated Deduction; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 238–251.

- The QED Manifesto. Available online: http://www.cs.ru.nl/~freek/qed/qed.html (accessed on May 15, 1994).

- Wiedijk, F. The QED manifesto revisited. Stud. Log., Grammar Rhetoric 2007, 10, 121–133.

- Weiss, I. The QED manifesto—Version 2.0. In Proceedings of the Asia–Pacific World Congr. Comput. Sci. Eng., Nadi, Fiji, 2014; pp. 1–7.

- Hales, T.C. The Kepler conjecture. 1998, arXiv:math/9811078.

- Hales, T.C. Formalizing the proof of the Kepler conjecture. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Theorem Proving Higher Order Logics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; p. 117.

- Hales, T.C. Introduction to the flyspeck project. Technical Report 432, Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz Center for Informat., Dagstuhl, Germany, 2006.