1. Introduction

Economic inequality and healthcare disparities remain critical challenges affecting the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Economic inequality refers to the uneven distribution of income and wealth across a population, leading to disparities in access to essential resources, including healthcare services (Ametoglo et al., 2018; Shrivastava et al., 2016). In ECOWAS, significant income gaps persist, resulting in limited healthcare access for low-income populations, disproportionately affecting marginalized groups (Bognini et al., 2021; Palacios et al., 2020). These inequalities have been linked to poor health outcomes, higher disease burdens, and lower life expectancy, with healthcare accessibility being primarily determined by income, geographic location, and financial inclusivity (Gordon et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). Access to healthcare is a fundamental determinant of well-being, yet in ECOWAS, systemic barriers hinder equitable health service provision. Studies have shown that individuals in the lowest income brackets are less likely to seek medical care due to financial constraints, inadequate insurance coverage, and high out-of-pocket expenses (Harikrishnan & Hiremath, 2024; Johar et al., 2018). The absence of universal health coverage (UHC) further exacerbates disparities, as wealthier individuals can afford private healthcare while low-income groups rely on underfunded public health facilities (Dickman et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2023). In some ECOWAS nations, socio-economic inequalities have contributed to discrepancies in curative healthcare-seeking behavior, particularly among vulnerable populations, such as women and children (Brinda et al., 2016).

Financial inclusivity is crucial in reducing healthcare disparities by ensuring individuals can access the financial resources needed for medical services. Financial inclusion refers to the availability and accessibility of affordable financial services which allow individuals to manage healthcare expenses effectively (Aluko & Ibrahim, 2020; Olaniyan et al., 2022). A well-structured financial system enhances healthcare affordability, prevents catastrophic health expenditures, and encourages preventive care, which is critical for long-term health sustainability (Al-Hanawi et al., 2020; Hunter & Murray, 2019). In many ECOWAS countries, financial exclusion remains a significant barrier to healthcare access, particularly for individuals in rural areas with limited banking infrastructure (Alimi et al., 2019; Lokossou et al., 2021). Research has shown that improving digital financial inclusion helps bridge the gap between economic disparity and healthcare access (Iheonu et al., 2020; Seddon & Currie, 2017). Countries that have implemented inclusive financial policies have improved healthcare utilization rates among low-income populations (Zouri, 2020). Moreover, financial inclusion can enhance the efficiency of government-subsidized healthcare programs by ensuring that funds are directly transferred to beneficiaries, reducing inequality and inefficiencies (Nwoko, 2021; Uneke et al., 2020). For instance, Sierra Leone's Free Healthcare Initiative (FHCI) provides empirical evidence of the positive impact of financial inclusivity. Following the introduction of FHCI, which eliminated user fees for maternal and child healthcare services, healthcare-seeking behavior among low-income households increased significantly, reducing inequalities in service utilization (Choi, 2018; Sulemana & Dramani, 2020).

However, despite such progress, challenges remain, as many ECOWAS nations continue to experience financial exclusion, which perpetuates economic barriers to healthcare (Manasseh et al., 2019; Weinrich, 2023). Economic disparities significantly limit access to quality healthcare, particularly in the ECOWAS region, where income inequality remains a pressing issue. Individuals in lower-income brackets often face multiple barriers to healthcare, including affordability constraints, lack of financial protection, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure (Kamdar et al., 2024). Out-of-pocket healthcare expenses constitute a significant financial burden for the poor, discouraging timely medical consultations and treatment, leading to worsening health conditions and higher mortality rates (Aglina et al., 2016; Maduekwe et al., 2019). The uneven distribution of healthcare resources exacerbates disparities, as wealthier individuals can access well-equipped private health facilities. In contrast, the underprivileged rely on public hospitals that are often underfunded and overstretched (Ridge et al., 2019). Additionally,

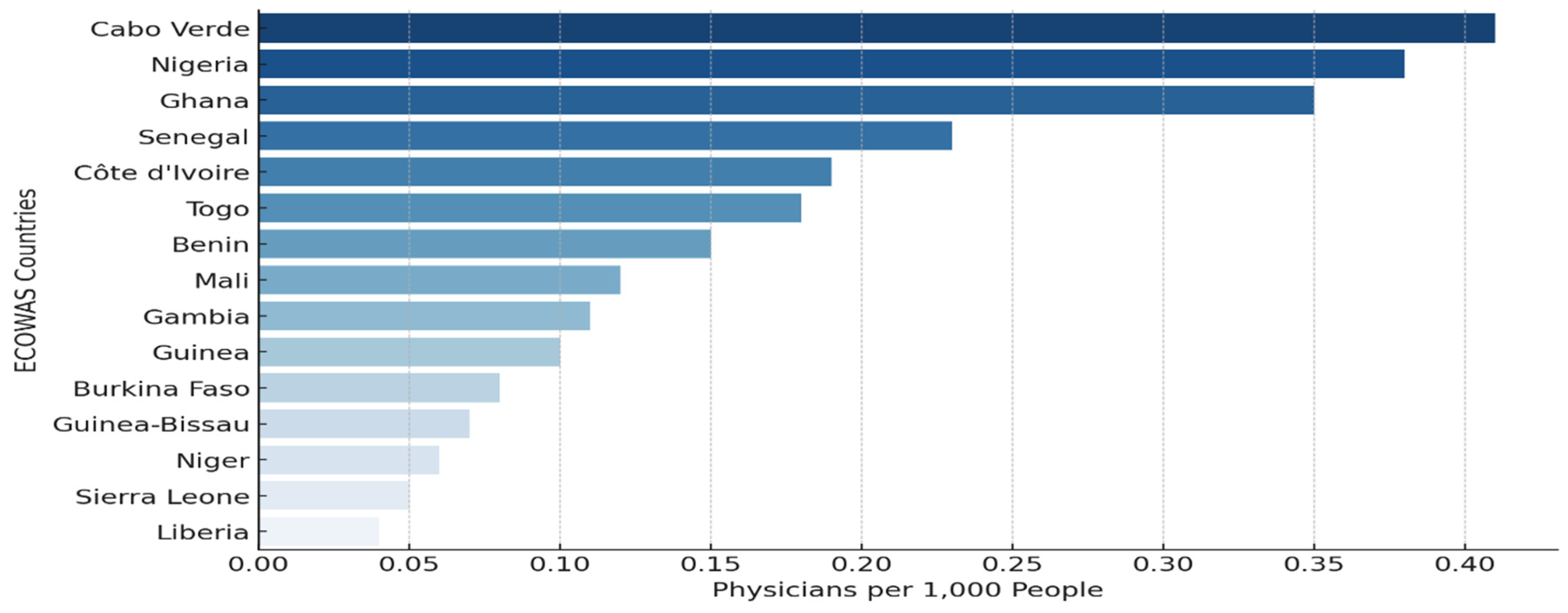

Figure 1 highlights the distribution of physicians per 1,000 people across ECOWAS nations, suggesting the disparities in healthcare accessibility, where few countries like Cabo Verde, Nigeria, and Ghana showcase the highest physician density, suggesting better healthcare infrastructure and workforce availability. In contrast, other countries are relatively low, underscoring severe shortages that may hinder medical service delivery, particularly in rural and underserved areas. These disparities reinforce the need for strategic health workforce policies, including improved funding for medical training, incentivized rural healthcare deployment, and international support to bridge healthcare gaps.

This study investigates the relationship between inequality and healthcare accessibility in ECOWAS, identifying how much disparities in income, wealth, and expenditure on health infrastructure contribute to health outcomes. The findings of this research have implications for policymakers, international organizations, and healthcare practitioners. Understanding the dynamics between economic inequality and healthcare access will provide empirical evidence to inform policy interventions to promote inclusive health financing strategies, as evidenced in the works of (Ametoglo et al., 2018; Olaniyan et al., 2022). The study also offers insights into the need for regulatory frameworks that encourage equitable health funding allocation (Al-Hanawi et al., 2020; Johar et al., 2018). It also highlights that the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank, and ECOWAS can leverage the study's findings to design targeted interventions and funding mechanisms that reduce health inequities. Moreover, the research contributes to the academic discourse on economic inequality and healthcare accessibility, offering a comprehensive analysis that can serve as a foundation for further studies and policy innovations in low- and middle-income countries.

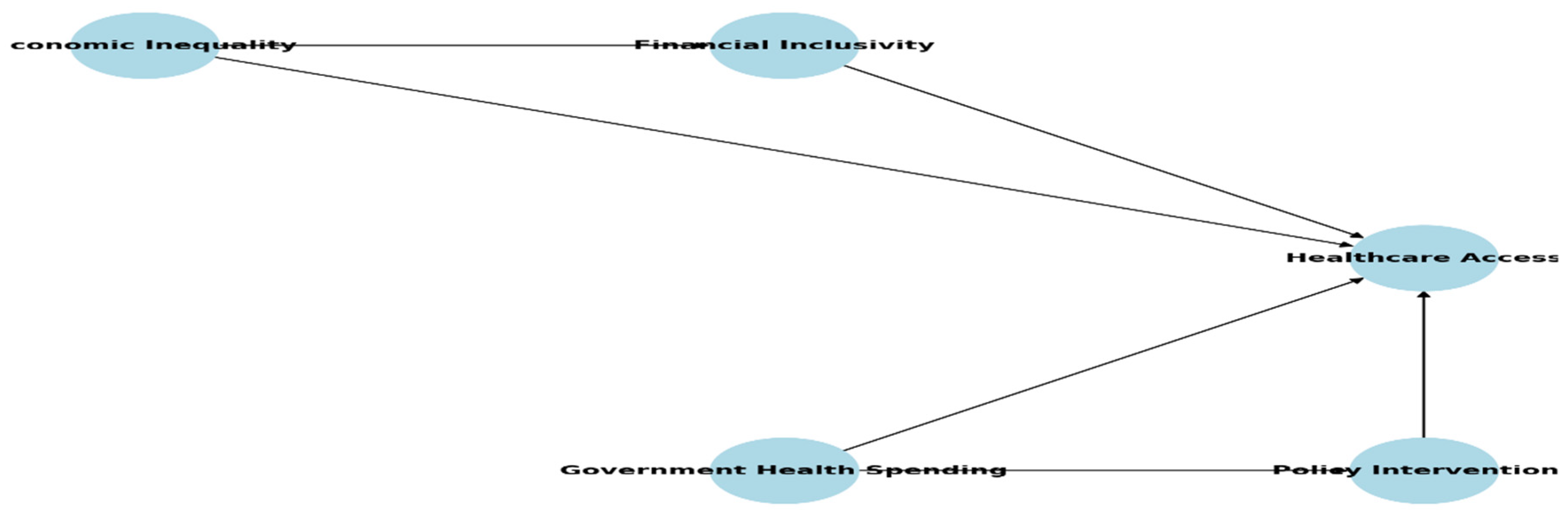

Figure 2 illustrates the interconnected relationship between economic inequality, financial inclusivity, healthcare access, government health spending, and policy interventions in the ECOWAS region. Economic inequality limits financial access, thereby restricting healthcare affordability and utilization. However, financial inclusivity through mechanisms like government health spending can mitigate these effects by improving healthcare accessibility, ensuring that targeted public health investments bridge disparities in physician availability and service affordability. Policy interventions reinforce these linkages by driving reforms that enhance equitable healthcare distribution. This framework underscores the importance of integrating government health spending, addressing disparities, and improving healthcare outcomes in ECOWAS.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 focuses on the background of the study. The details of the literature review are in section 2, while section 3 focuses on methodology. The results and discussion of findings were presented in section 4, and the conclusion, policy implications, and suggestions for further studies in section 5.

2. Literature Review

Economic inequality and healthcare disparities in ECOWAS are deeply rooted in structural and systemic factors that can be understood through various theoretical frameworks. This study draws upon the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) Model, which posits that health outcomes are significantly influenced by socioeconomic and environmental conditions rather than solely by medical factors (Brinda et al., 2016; Woldemichael et al., 2019). This model emphasizes the role of wealth distribution, education, employment, housing, and social capital in shaping healthcare access and overall well-being (Donahoe & Mcguire, 2020). In ECOWAS, the disparities in healthcare access are closely linked to economic inequalities, where lower-income populations experience inadequate healthcare due to financial constraints and limited social safety nets (Bognini et al., 2021; Palacios et al., 2020). Recent studies have highlighted that public health policies focusing on SDH can significantly improve health outcomes by targeting economic and social inequities (Donahoe & Mcguire, 2020; Yang et al., 2023). The model suggests that increasing access to financial resources, improving education, and addressing socioeconomic disparities can reduce healthcare inequities (Ametoglo et al., 2018; Gugushvili & Reeves, 2021). Furthermore, the SDH framework underscores that economic instability exacerbates poor health conditions, necessitating comprehensive policy interventions to address structural health determinants (Alimi et al., 2019; Harikrishnan & Hiremath, 2024). Public health economics highlights the importance of cost-effectiveness in healthcare financing and equitable resource distribution (Gordon et al., 2020; Langnel et al., 2021). Countries with strong institutional mechanisms can achieve better health outcomes by implementing universal health coverage (UHC) policies and ensuring adequate financial risk protection measures (Cui et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2023). Empirical evidence suggests that policy interventions promoting fiscal responsibility, corruption control, and efficient resource allocation can significantly reduce healthcare inequities and enhance service accessibility (Manasseh et al., 2019). By leveraging these theoretical frameworks, this study aims to contribute to policy development, evidence-based interventions, and practical solutions for enhancing healthcare inclusivity and reducing economic inequality in the ECOWAS region.

Economic inequality has been identified as a significant determinant of disparities in healthcare access, particularly in low- and middle-income regions such as ECOWAS. Research indicates that individuals in the lowest income quintiles often face limited access to quality healthcare services due to financial constraints, lack of health insurance coverage, and geographic inaccessibility (Ahmed & Mahapatro, 2023; Gordon et al., 2020; Woldemichael et al., 2019). The affordability of healthcare services remains a key challenge, as out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures constitute a significant portion of total health spending in many ECOWAS countries, disproportionately affecting the poor (Brinda et al., 2016; Johar et al., 2018). Empirical studies have demonstrated that income disparities correlate with healthcare utilization patterns, where wealthier individuals are more likely to seek medical treatment promptly, while low-income groups often delay or forgo necessary care due to financial barriers (Saito et al., 2016). In many ECOWAS nations, publicly funded healthcare services remain inadequate, and the burden of healthcare financing is shifted to private expenditure, further exacerbating inequality (Alimi et al., 2019; Arruda et al., 2018). This lack of equitable healthcare financing mechanisms calls for policy interventions that promote universal health coverage (UHC) and financial inclusivity to bridge the existing gaps.

Financial inclusivity is critical in mitigating economic barriers to healthcare access by providing individuals with the means to afford medical services through insurance schemes, microfinance programs, and digital banking solutions (Folayan et al., 2024; Tong et al., 2022). Studies indicate that financial inclusion, particularly mobile banking, and digital payment solutions, has improved healthcare affordability by reducing reliance on cash transactions and enabling access to health micro-insurance services in developing regions (Lokossou et al., 2021; Tong et al., 2022; Yu & Meng, 2022). Empirical evidence further suggests that countries with higher financial inclusion rates exhibit better healthcare financing mechanisms, leading to improved access to essential health services and lower rates of catastrophic health expenditures (Asaria et al., 2016; Harikrishnan & Hiremath, 2024). For example, implementing a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Ghana significantly increased healthcare utilization, yet financial constraints still limit participation among the poorest populations (Asaria et al., 2016). This highlights the need for targeted financial policies integrating healthcare financing with broader economic inclusion strategies.

Healthcare financing in ECOWAS remains highly fragmented, with a heavy reliance on OOP payments, donor funding, and insufficient government health expenditure. Research indicates that less than 30% of total health spending in many low-income countries within ECOWAS comes from government sources, compared to nearly 80% in high-income countries (Lokossou et al., 2021; Maduekwe et al., 2019). This results in significant disparities in healthcare access, particularly for marginalized populations. In contrast, developed economies with universal health coverage models, such as those in Europe, demonstrate the benefits of government-led health financing, where risk pooling and social insurance mechanisms reduce financial barriers to healthcare (Harikrishnan & Hiremath, 2024). The redistribution of health financing resources in these models ensures that low-income groups receive equitable healthcare services without the burden of catastrophic expenditures (Mulenga & Ataguba, 2017; Tandon & Reddy, 2021). Global perspectives on health financing suggest that low- and middle-income countries need to implement hybrid models that incorporate both public and private sector funding while ensuring financial sustainability (Behera & Dash, 2019; McGuire et al., 2019). Innovative financing strategies, such as performance-based funding and community health insurance schemes, have proven effective in expanding healthcare access in countries like Rwanda and Thailand, offering a blueprint for ECOWAS nations to adapt to their unique socio-economic contexts (Asante et al., 2020; Gomez-Gonzalez & Reyes, 2017; McGuire et al., 2019). The empirical evidence reviewed underscores the strong link between economic inequality and healthcare disparities in ECOWAS. Policymakers must consider these insights to develop sustainable health financing strategies that promote equitable healthcare access and financial protection for vulnerable populations.

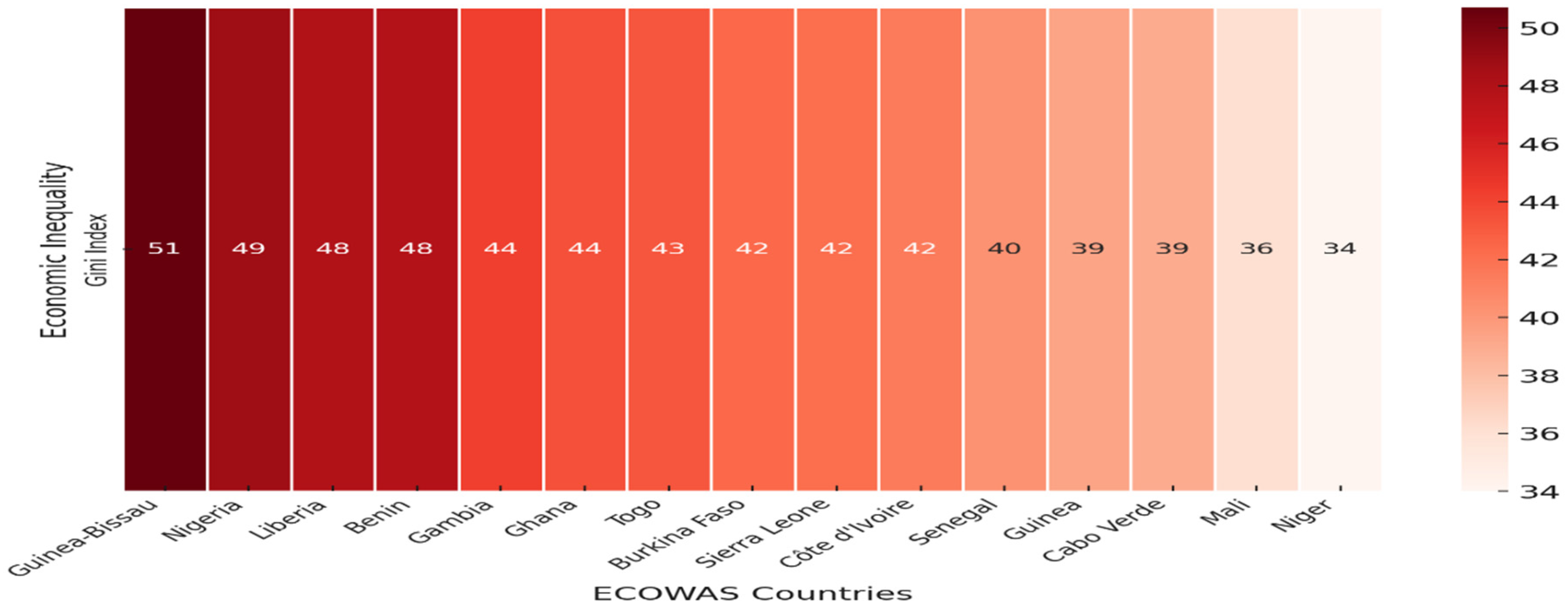

Figure 3 showcases the economic inequality across ECOWAS nations, measured by the Gini Index. Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, Liberia, and Benin revealed the highest rate of inequality compared to other nations, suggesting that these countries experience high levels of income disparities among the citizens, as this often hinders equitable healthcare access. However, Niger and Mali are the countries with lower inequality rates, implying an economic balance system. This shows that most of the ECOWAS nations experience high rates of income inequality, which highlights the urgent need to address income disparities and improve healthcare accessibility. This visualization effectively supports the discussion on how economic inequality influences healthcare disparities across the region.

Despite extensive research on economic inequality and healthcare access, significant gaps remain, particularly concerning the ECOWAS region. Existing studies have predominantly focused on high-income and middle-income countries, with limited region-specific analyses that address the unique socio-economic factors influencing healthcare disparities in ECOWAS (Ataguba, 2021; Oburota & Olaniyan, 2020; Shamu et al., 2017). One critical gap is the limited examination of financial inclusivity in healthcare spending and economic inequality within ECOWAS. Although financial inclusion has been shown to improve healthcare accessibility in some developing regions, there is little empirical research assessing its direct impact on healthcare financing, affordability, and service utilization in ECOWAS (Falco et al., 2023; Molla & Chi, 2017). This gap highlights the need for region-specific research that examines how health expenditure can mitigate healthcare disparities in economically diverse ECOWAS nations (McGuire et al., 2019; Rivillas et al., 2020; Sheinman & Terentieva, 2015). This study seeks to bridge the knowledge gap by providing a region-specific examination of economic growth and inequality and healthcare spending in ECOWAS, analyzing the relationships between economic inequality, economic growth, and health financing. This will contribute to developing tailored policy solutions that enhance healthcare accessibility, promote economic equity, and strengthen financial inclusivity in the region.

3. Methodology

This study employs an econometric approach to analyze Economic Inequality and Access to Healthcare: A Study of Economic Growth and Health Spending in ECOWAS. The study utilizes secondary panel data from global databases, like World Development Indicators (WDI), 2025. The dataset spans 24 years (2001–2024) and covers all 15 ECOWAS nations. The variables used were selected based on their relevance to the research objectives and their empirical significance from the previous studies. The study adopts two econometric models, each addressing specific research objectives, ensuring a comprehensive examination of inequality, economic growth, and healthcare access across the ECOWAS region.

The first model evaluates the impact of economic growth and inequality on healthcare accessibility within ECOWAS nations. Physicians per 1,000 people (PHC) is the dependent variable, reflecting healthcare system performance (Shaltynov et al., 2022; Yamada et al., 2015). The Gini Index (GIN) is included as an independent variable to measure income inequality and its effects on healthcare access (Langnel et al., 2021), while GDP per capita (GPC) determines economic capacity for healthcare investment (Aiyar & Ebeke, 2020). Government Health Expenditure (GHE) is analyzed to assess public spending's role in improving healthcare delivery (Alimi et al., 2019), and Population Density (PPD) is incorporated to evaluate the pressure on healthcare infrastructure in highly populated areas (Zhao et al., 2020). This model provides insights into the relationship between economic inequality, healthcare funding, and service accessibility, offering evidence-based guidance for policymakers in ECOWAS. The econometric specification is as follows:

The second model was the expansion of the first model, where the study introduced the interaction terms of government expenditure on health and income inequality to examine the extent of how government expenditure moderates or mitigates the presence of the income inequality (GHE*GIN) on Physicians per 1,000 people (PHC) which represents the availability of healthcare professionals as a key measure of healthcare system performance in the ECOWAS region. The econometric specification is as follows:

The study conducted several diagnostic tests, such as summary descriptive and correlation tests, to describe and ascertain the relationship among the study variables. Further, considering two different advanced econometric techniques to ensure reliability and minimize potential econometric issues, the study first used heteroskedasticity panel-corrected standard errors (HPCSE) to account for cross-sectional dependencies in ECOWAS nations' healthcare financing and economic structures (Moundigbaye et al., 2020; Umar et al., 2024). The study further validates the initial result with Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS), which was applied to control for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation, ensuring robustness in the estimations (Bai et al., 2019; Miller & Startz, 2018). Using these methodologies ensures that the findings are reliable, addressing potential estimation biases and enhancing the validity of the econometric analysis.

4. Results and discussion

The summary of descriptive statistics provides insights into key economic and healthcare-related variables within ECOWAS. The availability of physicians remains low, with an average of 0.135 physicians per 1,000 people, reflecting limited healthcare access. At the same time, population density varies widely across the region, with an average of 87.173 people per square km but reaching as high as 260.861. Government health expenditure as a percentage of GDP is low, averaging 1.156%, which may contribute to inadequate healthcare services. Economic inequality, represented by the Gini index with a mean of 39.365, suggests moderate income disparity. At the same time, GDP per capita shows substantial variation, with an average of $1,088.29, highlighting economic heterogeneity within ECOWAS nations. These findings underscore the structural weaknesses in ECOWAS healthcare systems, emphasizing the necessity for enhanced fiscal allocations, improved financial inclusivity, and equitable resource distribution to bridge healthcare disparities.

The correlation matrix provides valuable insights into the relationships between healthcare resources, economic inequality, financial inclusivity, and health expenditure in ECOWAS. Physician density (PHC) shows a strong positive correlation with GDP per capita (GPC) (0.836, p=0.000), suggesting that wealthier nations tend to have better healthcare infrastructure, reinforcing the link between economic development and healthcare accessibility. Additionally, PHC is moderately correlated with government health expenditure (GHE) (0.390, p=0.000), indicating that higher public investment in health correlates with improved availability of healthcare professionals. The Gini index (GIN) has a weak positive correlation with PHC (0.203, p=0.000), implying that higher income inequality does not necessarily translate into fewer physicians, although the relationship is not strong. Interestingly, GIN positively correlates with GHE (0.308, p=0.000), suggesting that governments may attempt to counteract inequality with increased health spending, albeit insufficiently. The results emphasize the crucial role of economic growth and targeted health investment in improving healthcare access. At the same time, inequality persists as a structural challenge requiring policy intervention to ensure more equitable healthcare distribution across ECOWAS.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix.

| VARIABLES |

PHC |

GIN |

GPC |

GIN*GHE |

PPD |

GHE |

| PHC |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GIN |

0.203 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| |

0.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GPC |

0.836 |

0.248 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

|

| GIN*GHE |

0.066 |

0.020 |

0.139 |

1.000 |

|

|

| |

-0.219 |

-0.706 |

-0.010 |

|

|

|

| PPD |

0.421 |

0.264 |

0.464 |

0.030 |

1.000 |

|

| |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

-0.581 |

|

|

| GHE |

0.390 |

0.308 |

0.338 |

0.118 |

0.116 |

1.000 |

| |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

-0.028 |

-0.032 |

|

The first objective is to examine the impact of Economic growth and Inequality on Healthcare Access in ECOWAS. The results indicate a significant negative relationship between economic inequality (GIN) and healthcare access, as measured by the number of physicians per 1,000 people (PHC), with a coefficient value of -0.003 and a p-value of less than 1%, suggests that higher levels of income inequality is correlated with lower availability of healthcare professionals. The result aligns with numerous previous scholars that demonstrated how economic disparities exacerbate healthcare access issues, most especially in countries or regions with poor or underfunded healthcare systems and overreliance on out-of-pocket expenditures (Hailu et al., 2021; Jakovljevic et al., 2022). GDP per capita (GPC) indicates a positive relationship with PHC, with a coefficient of 0.0002 and a p-value of less than 1%; this implies the role of economic growth in expanding healthcare infrastructure. This corroborates with the previous studies that emphasized that higher-income countries tend to invest more in healthcare resources, further fostering physician availability and overall healthcare access (Behera & Dash, 2019). Population density (PPD) also revealed a strong positive correlation with PHC, with a coefficient value of 0.0002 and a p-value of 1%; this suggests that urban areas with higher population densities benefit from better healthcare access. The findings are consistent with the studies that stated that this does not necessarily reflect improved health outcomes in rural areas, where physician shortages remain a challenge (Gordon et al., 2020). The overall findings of this objective underscore the importance of targeted policies addressing economic disparities through improved healthcare financing, especially in rural and underserved areas.

The second objective of this study included the moderating effect of government health spending on healthcare access in ECOWAS. Government health expenditure (GHE) revealed a positive and significant correlation with PHC, where the coefficient is 0.0313, with a p-value of 1%. This indicates that higher government spending on health fosters healthcare accessibility by increasing the number of available physicians. The findings align with several studies that emphasized the role of public expenditure on health as a key determinant of health infrastructure (Erlangga et al., 2023; Mulcahy et al., 2021). The results indicate a significant negative relationship between economic inequality (GIN) and healthcare access, as measured by the number of physicians per 1,000 people (PHC), with a coefficient value of -0.003 and a p-value of less than 1%, suggests that higher levels of income inequality is correlated with lower availability of healthcare professionals. The result aligns with previous scholars who demonstrated how economic disparities exacerbate healthcare access issues, especially in countries or regions with poor or underfunded healthcare systems and overreliance on out-of-pocket expenditures (Dwivedi & Pradhan, 2017). GDP per capita (GPC) indicates a positive relationship with PHC, with a coefficient of 0.0002 and a p-value of less than 1%; this implies the role of economic growth in expanding healthcare infrastructure. This corroborates with the previous studies that emphasized that higher-income countries tend to invest more in healthcare resources, further fostering physician availability and overall healthcare access (Erlangga et al., 2023; Kaur et al., 2024).

Population density (PPD) also revealed a strong positive correlation with PHC, with a coefficient value of 0.0002 and a p-value of 1%; this suggests that urban areas with higher population densities benefit from better healthcare access. The findings are consistent with the studies that stated that this does not necessarily reflect improved health outcomes in rural areas, where physician shortages remain a challenge (Bai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020). The interaction term of (GIN*GHE) is also positively significant with a coefficient of 0.002 with a p-value of less than 5%, indicating that government health expenditure has the potential to mitigate the adverse effects of economic inequality on healthcare access. This suggests that targeted public health investments can play a critical role in narrowing healthcare disparities. This is corroborated by several studies that have shown that countries with adequate financial inclusivity frameworks, such as mobile banking and microfinance-linked health insurance, have been able to improve healthcare affordability and reduce economic barriers to access (Rahman et al., 2018; Usman et al., 2019; Wang & Tao, 2019). The findings of this objective reaffirm the significant impact of economic inequality on healthcare access and highlight the critical role of public health spending in mitigating healthcare disparities, as government health expenditure plays a crucial role in improving and enhancing healthcare accessibility across the ECOWAS region.

Table 3.

Heteroskedasticity Panel-Corrected Standard Errors (HPCSE).

Table 3.

Heteroskedasticity Panel-Corrected Standard Errors (HPCSE).

| VARIABLES |

PHC |

PHC |

| GIN |

-0.0030*** |

-0.003*** |

| |

(0.0011) |

(0.001) |

| GPC |

0.0002*** |

-0.078** |

| |

(5.751) |

(0.037) |

| GHE |

0.0313*** |

0.002** |

| |

(0.0065) |

(0.001) |

| GIN*GHE |

|

0.002** |

| |

|

(0.001) |

| PPD |

0.0002*** |

0.000*** |

| |

(5.5810) |

(0.000) |

| Constant |

0.0852* |

0.153*** |

| |

(0.0437) |

(0.044) |

| Observations |

360 |

360 |

| Number of countries |

15 |

15 |

| R-squared |

0.731 |

0.904 |

| Wald Chi2 |

2011.83*** |

493.89*** |

The Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) robustness test confirms the reliability of the initial findings, reinforcing the link between economic inequality, government expenditure on health, and economic growth on healthcare access in ECOWAS. The negative and significant impact of income inequality (GIN) on physician availability (PHC) remains consistent, affirming that unequal income distribution limits healthcare access. GDP per capita (GPC) positively influences healthcare access, but its effect is constrained by governance and financial accessibility barriers. Government health expenditure (GHE) improves physician availability, and its interaction with GIN (GIN*GHE) is now statistically significant, indicating that public health investments can reduce inequality-driven healthcare disparities if effectively managed. However, population density (PPD) now has a negative impact, highlighting the strain urban overcrowding places on healthcare infrastructure. Policymakers should prioritize financial inclusivity, optimize healthcare spending, and address urban healthcare challenges to improve accessibility in ECOWAS.

Table 4.

Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS).

Table 4.

Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS).

| VARIABLES |

PHC |

PHC |

| GIN |

-0.001** |

-0.003*** |

| |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

| GPC |

0.000** |

-0.078** |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.038) |

| GHE |

0.006* |

0.002** |

| |

(0.014) |

(0.001) |

| GIN*GHE |

|

0.000*** |

| |

|

(0.000) |

| PPD |

0.000*** |

-0.0030*** |

| |

(0.000) |

(0.00110) |

| Constant |

0.044* |

0.153*** |

| |

(0.046) |

(0.054) |

| |

|

|

| Observations |

360 |

360 |

| Number of Countries |

15 |

15 |

| Wald Chi2 |

1242.02*** |

417.48*** |

5. Conclusion, Policy Implications, and Limitations

This study confirms that economic inequality significantly reduces healthcare access in ECOWAS, while financial inclusivity and government health expenditure play crucial roles in mitigating these disparities. The findings highlight that higher GDP per capita and increased public health spending improve physician availability, but their impact is constrained by institutional inefficiencies and governance challenges. Additionally, the interaction between government health expenditure and inequality suggests that targeted financial policies can reduce healthcare disparities. These results underscore the need for comprehensive healthcare financing reforms that integrate economic policies with equitable health service distribution to enhance regional healthcare access.

Policymakers should prioritize financially inclusive strategies, such as expanding digital banking, microfinance, and health insurance coverage, to bridge economic gaps in healthcare access. Governments must increase healthcare funding, ensuring that spending is effectively allocated to underserved areas, particularly rural and densely populated regions. Strengthening institutional frameworks and governance mechanisms is crucial to reducing inefficiencies, corruption, and mismanagement of health funds. Adopting hybrid financing models, including public-private partnerships and performance-based funding, can enhance resource mobilization and healthcare delivery across ECOWAS.

While the study provides robust insights, data limitations and potential measurement errors in health expenditure and inequality indicators may affect result precision. The cross-sectional nature of the analysis limits the ability to capture long-term healthcare dynamics. Additionally, unobserved country-specific factors such as political instability, informal healthcare markets, and cultural health-seeking behaviors were not explicitly modeled, which may influence healthcare accessibility. Future research should explore longitudinal studies and qualitative approaches to provide deeper insights into the evolving relationship between economic inequality, financial inclusivity, and healthcare outcomes in ECOWAS.

Declaration of AI use

While preparing this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the English language and readability. After using it, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication's content.

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Aglina, M., Agbejule, A., & Nyamuame, G. Y. (2016). Policy framework on energy access and key development indicators: ECOWAS interventions and the case of Ghana. Energy Policy, 97, 332–342. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., & Mahapatro, S. (2023). Inequality in Healthcare Access at the Intersection of Caste and Gender. Contemporary Voice of Dalit, 15, 75–85. [CrossRef]

- Aiyar, S., & Ebeke, C. (2020). Inequality of opportunity, inequality of income, and economic growth. World Development. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M. K., Chirwa, G., Kamninga, T., & Manja, L. P. (2020). Effects of Financial Inclusion on Access to Emergency Funds for Healthcare in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 13, 1157–1167. [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O., Ajide, K., & Isola, W. (2019). Environmental quality and health expenditure in ECOWAS. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22, 5105–5127. [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O., & Ibrahim, M. (2020). Institutions and financial development in ECOWAS. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 11, 187–198. [CrossRef]

- Ametoglo, M., Guo, P., & Wonyra, K. O. (2018). Regional Integration and Income Inequality in ECOWAS Zone. Journal of Economic Integration. [CrossRef]

- Arruda, N. M., Maia, A. G., & Alves, L. C. (2018). [Inequality in access to health services between urban and rural areas in Brazil: A disaggregation of factors from 1998 to 2008]. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 34 6. [CrossRef]

- Asante, A., Wasike, W., & Ataguba, J. (2020). Health Financing in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Analytical Frameworks to Empirical Evaluation. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 18, 743–746. [CrossRef]

- Asaria, M. , Ali, S., Doran, T., Ferguson, B., Fleetcroft, R., Goddard, M., Goldblatt, P., Laudicella, M., Raine, R., & Cookson, R. (2016). How a universal health system reduces inequalities: Lessons from England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70, 637–643. [CrossRef]

- Ataguba, J. (2021). The Impact of Financing Health Services on Income Inequality in an Unequal Society: The Case of South Africa. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 19, 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J., Choi, S., & Liao, Y. (2019). Feasible generalized least squares for panel data with cross-sectional and serial correlations. Empirical Economics, 60, 309–326. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q., Ke, X., Huang, L., Liu, L., Xue, D., & Bian, Y. (2022). Finding flaws in the spatial distribution of health workforce and its influential factors: An empirical analysis based on Chinese provincial panel data, 2010–2019. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Behera, D. K., & Dash, U. (2019). Effects of economic growth towards government health financing of Indian states: An assessment from a fiscal space perspective. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 12, 206–227. [CrossRef]

- Bognini, J., Samadoulougou, S., Ouédraogo, M., Kangoye, T. D., Malderen, C. V., Tinto, H., & Kirakoya-Samadoulougou, F. (2021). Socioeconomic inequalities in curative healthcare-seeking for children under five before and after the free healthcare initiative in Sierra Leone: Analysis of population-based survey data. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20. [CrossRef]

- Brinda, E., Attermann, J., Gerdtham, U., & Enemark, U. (2016). Socio-economic inequalities in health and health service use among older adults in India: Results from the WHO Study on Global AGEing and adult health survey. Public Health, 141, 32–41. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. (2018). Experiencing Financial Hardship Associated With Medical Bills and Its Effects on Health Care Behavior: A 2-Year Panel Study. Health Education & Behavior, 45, 616–624. [CrossRef]

- Cui, B., Boisjoly, G., Serra, B., & El-geneidy, A. (2022). Modal equity of accessibility to healthcare in Recife, Brazil. Journal of Transport and Land Use. [CrossRef]

- Dickman, S. L., Himmelstein, D., & Woolhandler, S. (2017). Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. The Lancet, 389, 1431–1441. [CrossRef]

- Donahoe, J., & Mcguire, T. (2020). The vexing relationship between socioeconomic status and health. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 9. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R., & Pradhan, J. (2017). Does equity in healthcare spending exist among Indian states? Explaining regional variations from national sample survey data. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16. [CrossRef]

- Erlangga, D., Powell-Jackson, T., Balabanova, D., & Hanson, K. (2023). Determinants of government spending on primary healthcare: A global data analysis. BMJ Global Health, 8. [CrossRef]

- Falco, P. R. D., Hodgson, L. T. F., McConnell, J. M., Ahmed, P. A. K., & De, R. (2023). Assessing the Human Rights Framework on Private Health Care Actors and Economic Inequality. Health and Human Rights, 25, 125–139.

- Folayan, A., Fatt, Q. K., Cheong, M., & Su, T. T. (2024). Healthcare cost coverage inequality and its impact on hypertension and diabetes: A five-year follow-up study in a Malaysian rural community. Health Science Reports, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gonzalez, J. E., & Reyes, N. R. (2017). Patterns of global health financing and potential future spending on health. The Lancet, 389, 1955–1956. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S., Gao, Y., Zhang, F., Mu, L., Kang, C., & Liu, Y. (2021). Evaluating healthcare resource inequality in Beijing, China, based on an improved spatial accessibility measurement. Transactions in GIS, 25, 1504–1521. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T. , Booysen, F., & Mbonigaba, J. (2020). Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: The case of South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20. [CrossRef]

- Gugushvili, A. , & Reeves, A. (2021). How democracy alters our view of inequality—And what it means for our health. Social Science & Medicine, 283. [CrossRef]

- Hailu, A. , Gebreyes, R., & Norheim, O. (2021). Equity in public health spending in Ethiopia: A benefit incidence analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 36, 4–13. [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, K. , & Hiremath, G. (2024). Inequality in Public Provision of Healthcare: Do Fiscal Transfers Matter? Journal of Public Affairs. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B. M. , & Murray, S. (2019). Deconstructing the Financialization of Healthcare. Development and Change. [CrossRef]

- Iheonu, C. O. , Asongu, S., Odo, K. O., & Ojiem, P. K. (2020). Financial sector development and Investment in selected countries of the Economic Community of West African States: Empirical evidence using heterogeneous panel data method. Financial Innovation, 6. [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M. , Pallegedara, A., Vinayagathasan, T., & Kumara, A. S. (2022). Editorial: Inequality in healthcare utilization and household spending in developing countries. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Johar, M., Soewondo, P., Pujisubekti, R., Satrio, H. K., & Adji, A. (2018). Inequality in access to health care, health insurance and the role of supply factors. Social Science & Medicine, 213, 134–145. [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, D. , Hossein, Y., Al-Alewi, T., Abdulrahim, N., & Kayyali, R. (2024). Exploring experiences and perspectives of inclusivity amongst community pharmacists in their practice: A survey study. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S. , Kiran, R., & Sharma, R. (2024). Healthcare Expenditure, Health Outcomes and Economic Growth: A Study of BRICS Countries. Millennial Asia. [CrossRef]

- Langnel, Z., Amegavi, G. B., Donkor, P., & Mensah, J. (2021). Income inequality, human capital, natural resource abundance, and ecological footprint in ECOWAS member countries. Resources Policy, 74. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , Tang, C., & Wang, H. (2020). Investigating the association of health system characteristics and health care utilization: A multilevel model in China's aging population. Journal of Global Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lokossou, V. K. , Atama, N. C., Nzietchueng, S., Koffi, B. Y., Iwar, V., Oussayef, N., Umeokonkwo, C. D., Behravesh, C. B., Sombie, I., Okolo, S., & Ouendo, E.-M. (2021). Operationalizing the ECOWAS regional one health coordination mechanism (2016–2019): Scoping review on progress, challenges and way forward. One Health, 13, 100291. [CrossRef]

- Maduekwe, M. , Morris, E., Greene, J., & Healey, V. (2019). Gender Equity and Mainstreaming in Renewable Energy Policies—Empowering Women in the Energy Value Chain in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports, 6, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Manasseh, C. O. , Ihedimma, G. I., Abada, F. C., Nwakoby, I. C., Njoku, B., Kesuh, J. T., Okeke, C. G., Alio, F., & Onwumere, J. (2019). DID GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS WORSEN OIL PRICE VOLATILITY AND BANKING SECTOR NEXUS IN SELECTED ECOWAS AND G-7 MEMBER COUNTRIES? International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, F. , Vijayasingham, L., Vassall, A., Small, R., Webb, D., Guthrie, T., & Remme, M. (2019). Financing intersectoral action for health: A systematic review of co-financing models. Globalization and Health, 15. [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. , & Startz, R. (2018). Feasible generalized least squares using support vector regression. Economics Letters. [CrossRef]

- Molla, A. , & Chi, C. (2017). Who pays for healthcare in Bangladesh? An analysis of progressivity in health systems financing. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16. [CrossRef]

- Moundigbaye, M., Messemer, C., Parks, R. W., & Reed, W. R. (2020). Bootstrap methods for inference in the Parks model. Economics, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, P. , Mahal, A., McPake, B., Kane, S., Ghosh, P., & Lee, J. (2021). Is there an association between public spending on health and choice of healthcare providers across socioeconomic groups in India? - Evidence from a national sample. Social Science & Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, A., & Ataguba, J. (2017). Assessing income redistributive effect of health financing in Zambia. Social Science & Medicine, 189, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, K. C. (2021). ECOWAS responses to the COVID-19 pandemic under its peace and security architecture. South African Journal of International Affairs, 28, 29–46. [CrossRef]

- Oburota, C. , & Olaniyan, O. (2020). Health care financing and income inequality in Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics. [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, T. O. , Ijaiya, M. A., & Kolapo, F. T. (2022). Remittances, Financial Sector Development, Institutions and Economic Growth in the ECOWAS Region. Migration Letters. [CrossRef]

- Palacios, A. , Espinola, N., & Rojas-Roque, C. (2020). Need and inequality in the use of health care services in a fragmented and decentralized health system: Evidence for Argentina. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. , Khanam, R., & Rahman, M. (2018). Health care expenditure and health outcome nexus: New evidence from the SAARC-ASEAN region. Globalization and Health, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ridge, L., Dickson, V., & Stimpfel, A. W. (2019). The Occupational Health of Nurses in the Economic Community of West African States: A Review of the Literature. Workplace Health & Safety, 67, 554–564. [CrossRef]

- Rivillas, J. C. , Devia-Rodriguez, R., & Ingabire, M.-G. (2020). Measuring socioeconomic and health financing inequality in maternal mortality in Colombia: A mixed methods approach. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19. [CrossRef]

- Saito, E., Gilmour, S., Yoneoka, D., Gautam, G. S., Rahman, M. M., Shrestha, P., & Shibuya, K. (2016). Inequality and inequity in healthcare utilization in urban Nepal: A cross-sectional observational study. Health Policy and Planning, 31, 817–824. [CrossRef]

- Seddon, J., & Currie, W. (2017). Healthcare financialisation and the digital divide in the European Union: Narrative and numbers. Inf. Manag., 54, 1084–1096. [CrossRef]

- Shaltynov, A. , Rocha, J., Jamedinova, U., & Myssayev, A. (2022). Assessment of primary healthcare accessibility and inequality in north-eastern Kazakhstan. Geospatial Health, 17 1. [CrossRef]

- Shamu, S., January, J., & Rusakaniko, S. (2017). Who benefits from public health financing in Zimbabwe? Towards universal health coverage. Global Public Health, 12, 1169–1182. [CrossRef]

- Sheinman, I., & Terentieva, S. (2015). International comparison of the effectiveness of fiscal and insurance models of healthcare financing. Economic Policy, 6. https://consensus.app/papers/international-comparison-of-the-effectiveness-of-fiscal-sheinman-terentieva/e7d8f276f07651b18d7a918e3b4b98b1/.

- Shrivastava, S. , Shrivastava, P., & Ramasamy, J. (2016). Inequality in Health for Women, Infants, and Children: An Alarming Public Health Concern. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 7. [CrossRef]

- Sulemana, M., & Dramani, J. B. (2020). Effect of financial sector development and institutions on economic growth in SSA. Does the peculiarities of regional blocs matter? Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12, 1102–1124. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A., & Reddy, K. (2021). Redistribution and the health financing transition. Journal of Global Health, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y. , Tan, C.-H., Sia, C., Shi, Y., & Teo, H. (2022). Rural-Urban Healthcare Access Inequality Challenge: Transformative Roles of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Umar, U. H. , Baita, A. J., Hamadou, I., & Abduh, M. (2024). Digital finance and SME financial inclusion in Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies. [CrossRef]

- Uneke, C. J. , Sombie, I., Johnson, E., Uneke, B. I., & Okolo, S. (2020). Promoting the use of evidence in health policymaking in the ECOWAS region: The development and contextualization of an evidence-based policymaking guidance. Globalization and Health. [CrossRef]

- Usman, M. , Ma, Z., Zafar, M. W., Haseeb, A., & Ashraf, R. U. (2019). Are Air Pollution, Economic and Non-Economic Factors Associated with Per Capita Health Expenditures? Evidence from Emerging Economies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. , & Tao, C. (2019). Research on the Efficiency of Local Government Health Expenditure in China and Its Spatial Spillover Effect. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, A. (2023). Regional citizenship regimes from within: Unpacking divergent perceptions of the ECOWAS citizenship regime. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 61, 117–138. [CrossRef]

- Woldemichael, A. , Takian, A., Sari, A. A., & Olyaeemanesh, A. (2019). Availability and inequality in accessibility of health centre-based primary healthcare in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T., Chen, C.-C., Murata, C., Hirai, H., Ojima, T., Kondo, K., & Harris, J. R. (2015). Access Disparity and Health Inequality of the Elderly: Unmet Needs and Delayed Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 1745–1772. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Katumba, K., & Griffin, S. (2021). Incorporating health inequality impact into economic evaluation in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 22, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. , Zhong, Q., Liao, Z., Pan, C., & Fan, Q. (2023). Socioeconomic deprivation, medical services accessibility, and income-related health inequality among older Chinese adults: Evidence from a national longitudinal survey from 2011 to 2018. Family Practice. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., & Meng, S. (2022). Impacts of the Internet on Health Inequality and Healthcare Access: A Cross-Country Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Gallifant, J., Pierce, R. L., Fordham, A., Teo, J., Celi, L., & Ashrafian, H. (2023). Quantifying digital health inequality across a national healthcare system. BMJ Health & Care Informatics, 30. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P., Li, S., & Liu, D. (2020). Unequable spatial accessibility to hospitals in developing megacities: New evidence from Beijing. Health & Place, 65, 102406–102406. [CrossRef]

- Zouri, S. (2020). Business cycles, bilateral trade and financial integration: Evidence from Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). International Economics. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).