Result and Discussion

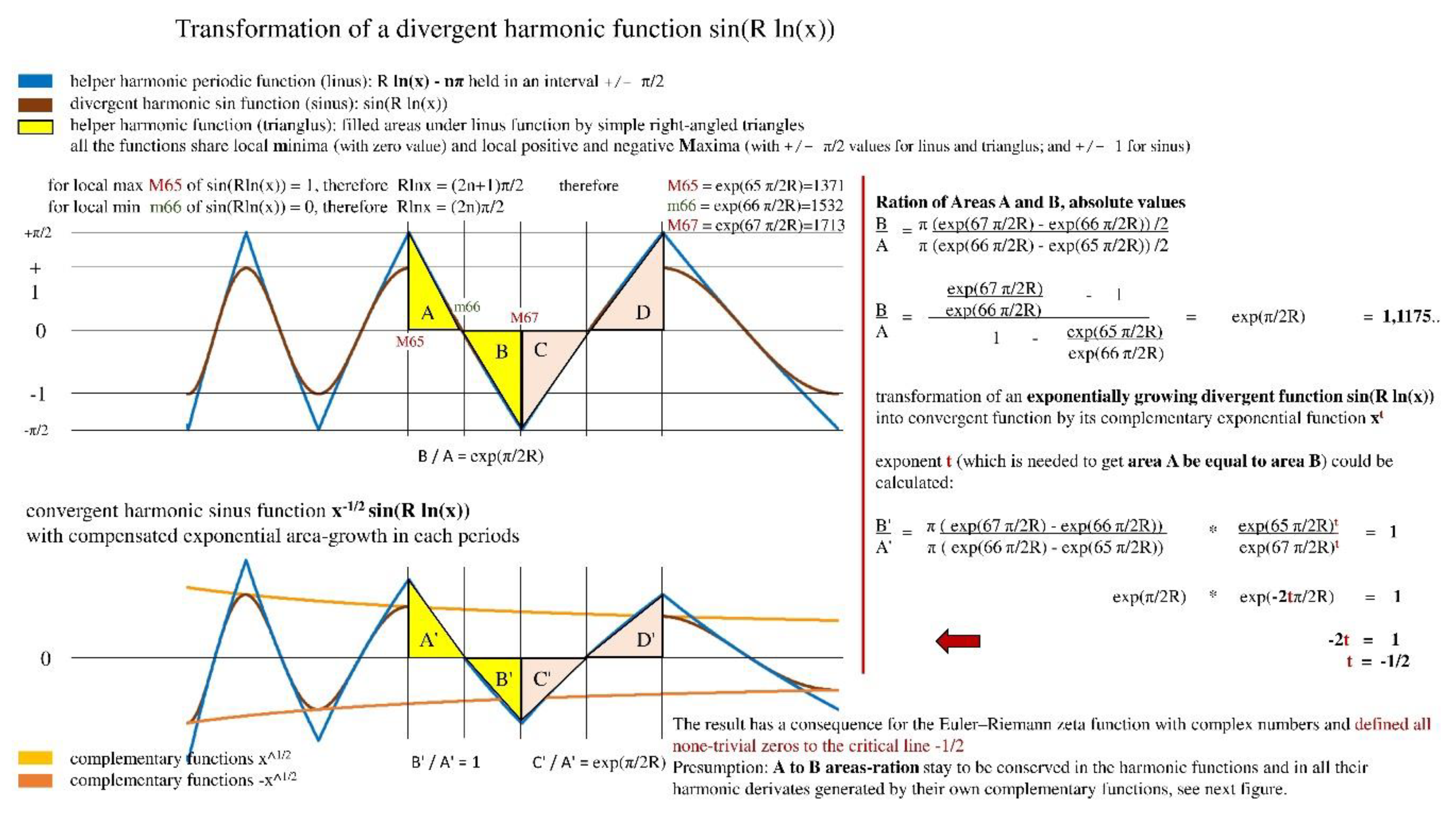

First, I created a helper harmonic periodic function above the sin(Rln(x)) curve using simplification, which I named linus (

Figure 2). The linus function was developed by subtracting nπ, which is equivalent to arcsin(sin(Rln(x)) function (which I termed assRln(x) function), where R is any real number over 10. This allowed linus values to be limited between an interval of -π/2 to +π/2.

I made further simplifications and created a another helper harmonic periodic function, which I named trianglus sustaining, from straightforward right-angled triangles filled under the linus function in order to perform exact and straightforward area computations under the linus curve (

Figure 2).

Local minima m, which have a value of zero, are shared by all the functions. Local positive and negative maxima M have values of ±π/2 for linus and trianglus and ±1 for sinus.

I assumed that the A to B areas-ration would remain constant between the sinus, linus, and triangle harmonic periodic functions as well as in their harmonic derivatives produced by their respective exponentially complementary functions (for evidence read further).

In order to calculate local maxima and minima, I first defined the following formulas: local max sin(Rln(x)) = 1, Rln(x) must equal (2n+1) π/2; local min sin(Rln(x)) = 0, Rln(x) must equal (2n) π/2. As an illustration, consider the following: local maximum M65 = exp(65 π/2R), local minimum M66 = exp(66 π/2R), and local minimum M67 = exp(67 π/2R). In conclusion, the distribution of the local maxima and minima is exponential.

Subsequently, I computed the triangular areas rations B to A, which are determined by the local maxima M65 and M67 and equal exp(π/2R) (

Figure 2). Similarly, C to A is equal to exp(2π/2R), and D to A is equal to exp(3π/2R). In conclusion, the areas in divergent periodic harmonic sin(Rln(x)) function grow exponentially.

At this point, using a complementary exponential function, I wanted to transform the divergent sin(Rln(x)) by complementary exponential function into convergent sin function, in which I would compensated area’s exponential growth in each periods and turn it to ration one-to-one between area par A and B.

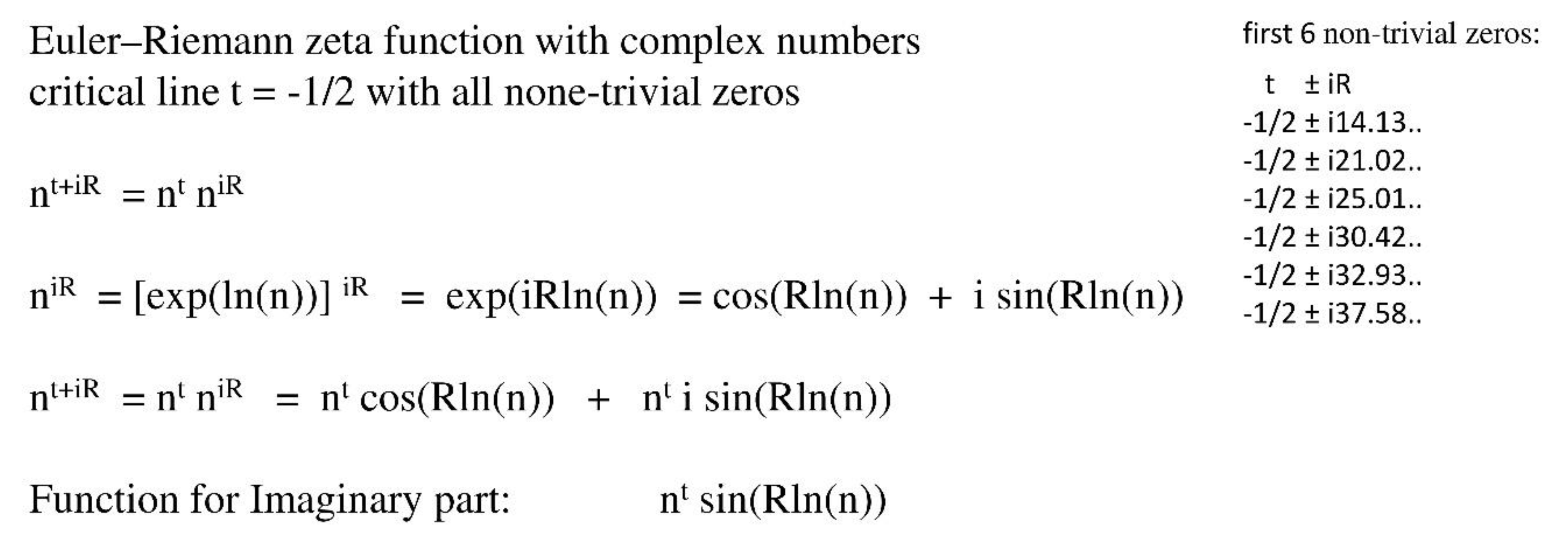

The conditions were satisfied by the simple exponential function x

t, which is also coherent with the imaginary function in the Euler-Riemann zeta function with complex numbers (

Figure 1). The exponent t for the A and B areas could be determined using the triangular simplification, and it was found to be equal to -1/2 (

Figure 2).

Finally, I examined the x

t exponential complementary function on sin(Rln(x)) with an exponent of -1/2. As I had assumed, sin(Rln(x)) could be treated using the output of the harmonic periodic function trianglus and linus. The area-ratio B to A under the x

-1/2sin(Rln(x)) curve is 1 (proven integral calculus)(

Figure 4). Nevertheless, in the x

-1/2sin(Rln(x)) function, the areas A to C continue to rise exponentially by exp(2π/2R).

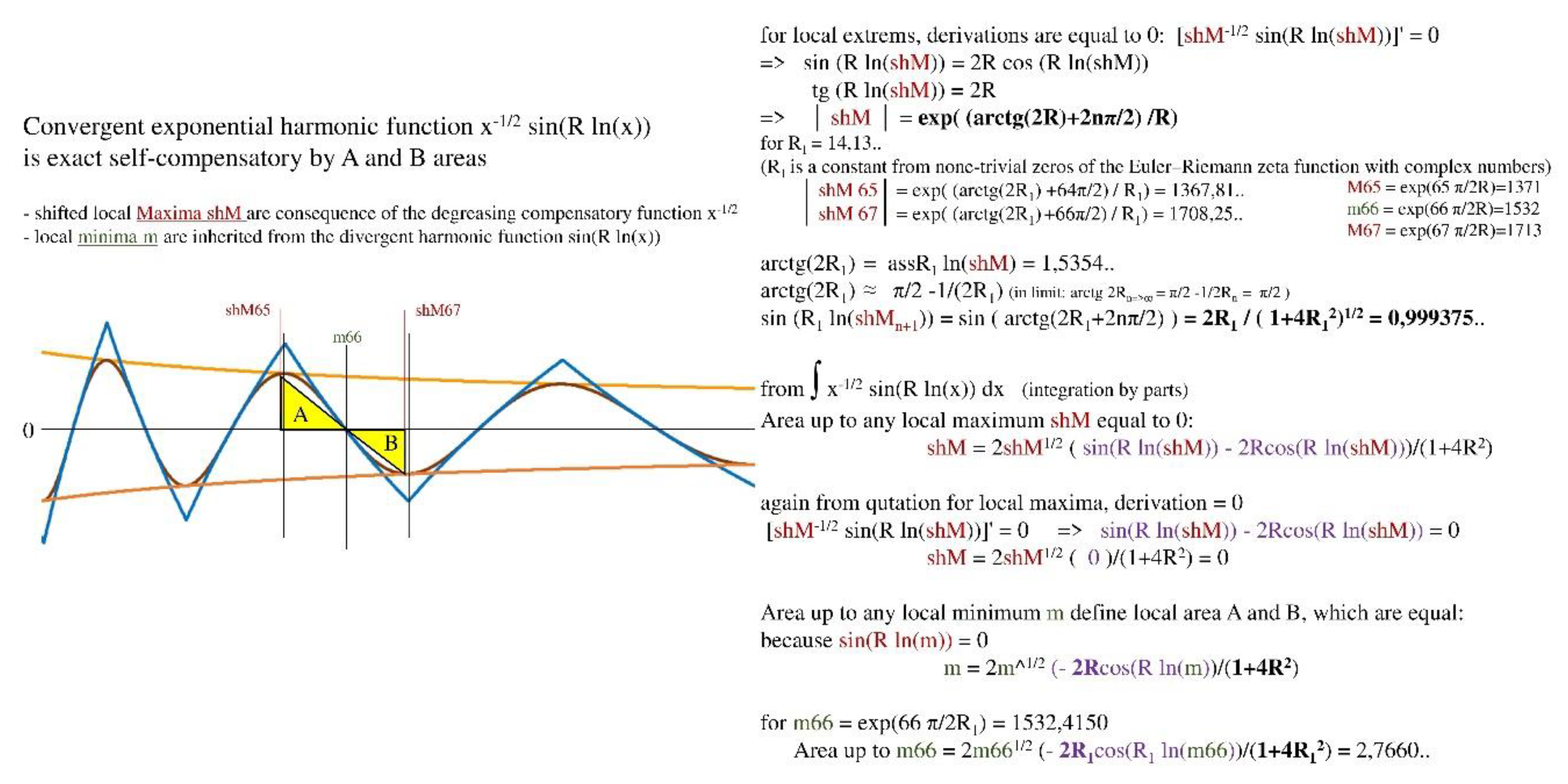

The degreasing compensating function x

-1/2 induces deformation of the sin curve through shifted local maxima shM. These can be calculated from derivation [x

-1/2sin(Rln(x))]' equal zero. That means that tg(Rln(shM)) = 2R and │shM│= exp((arctg 2R+2nπ/2) / R). As a result, the 2R value modifies the shape of the sinus curve x

-1/2sin(Rln(x)) by defining shift for local maxima. Nonetheless, the local minima m are inherited from the divergent sin function sin(Rln(x))(

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Self-compensatory property. Convergent exponential harmonic sin function x-1/2 sin(R ln(x)) has self-compensatory due its positive A and negative B areas.

Figure 3.

Self-compensatory property. Convergent exponential harmonic sin function x-1/2 sin(R ln(x)) has self-compensatory due its positive A and negative B areas.

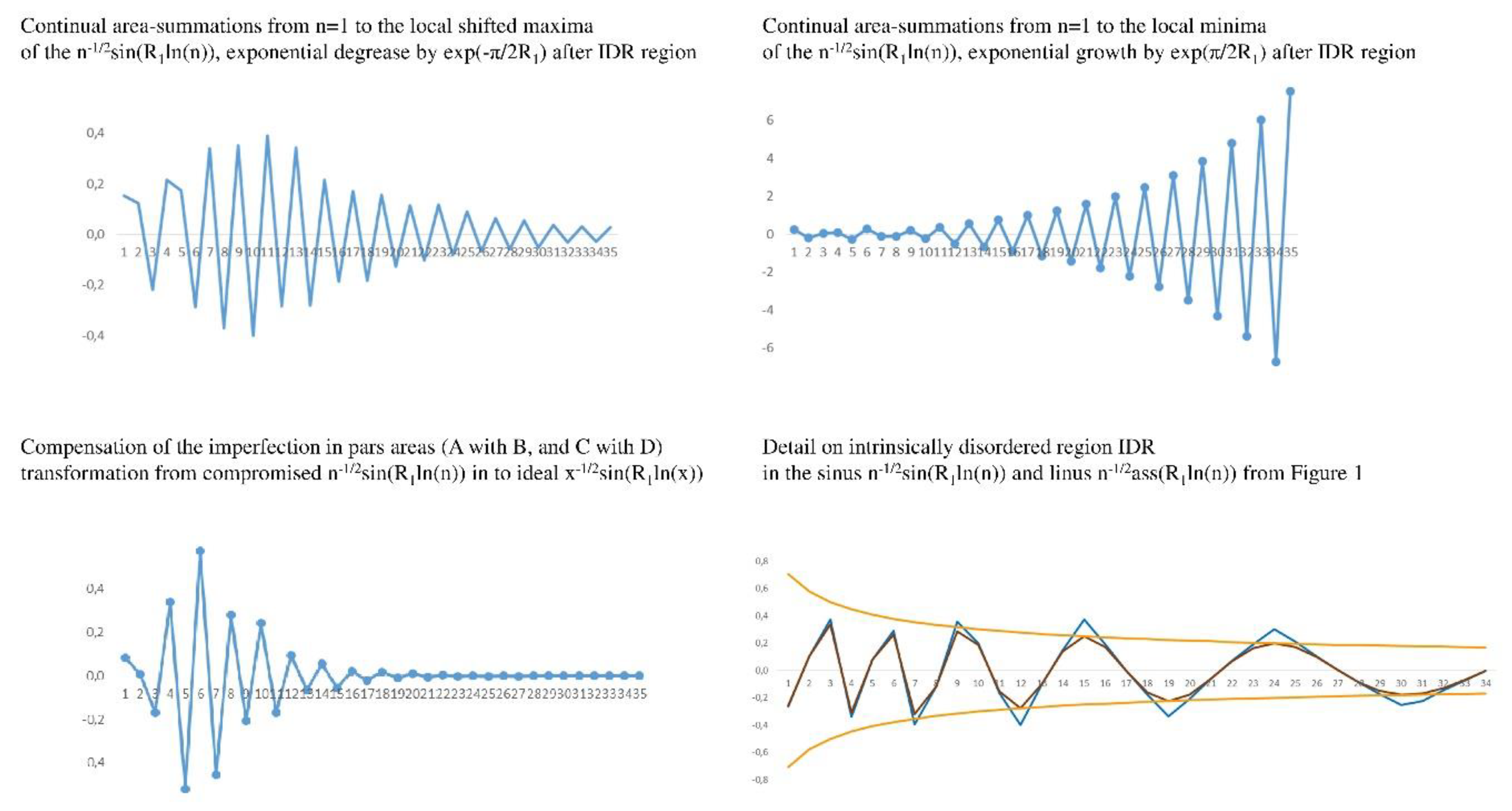

Due to the compensatory function, the transformed function x

-1/2sin(Rln(x)) is a periodic harmonic function that converges to zero (R was tested from 10 to 20, below 10 the values are too high, therefore not sure about validity for R below 10, not shown). This is only true for continuous functions, where the real numbers in the input are continuous. In contrast, an n

-1/2sin(Rln(n)) function, where n are natural numbers, the function became discontinuous and produced imperfections in the otherwise harmonic functions x

-1/2sin(Rln(x)) and x

-1/2ass(Rln(x)) (particularly with initial values in an intrinsically disordered region, IDR) (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Continual area-summations from n=1 to the local shifted maxima of the n-1/2sin(R1ln(n)).

Figure 4.

Continual area-summations from n=1 to the local shifted maxima of the n-1/2sin(R1ln(n)).

The position of the sinus curve n-1/2sin(Rln(n)) with regard to the natural numbers (the raster), influences how much volume is produced in the areas A and B under the sinus curve (strips formation under sin).

As a result, practically all of n

-1/2sin(Rln(n)) functions converge somewhere away from zero after accumulating random imperfections. The only functions that employ non-trivial zero constants R

x, accrue exactly the same volumes A and B under sinus including their imperfections, and converge to zero. The 2R

x define their shifted maxima; sinus shape deformation decreases as R value increases, whereas frequency increases as R value increases (

Figure 3).

Regions A and B have almost identical volumes (after IDR region), despite the fact that n

-1/2sin(Rln(n)) is still an exponentially expanding function and that the region A and B accommodate the exponentially growing counts of the natural numbers with their imperfections. Crucially, because of imperfection links to the natural numbers by both size and counts, the self-compensation effect applied on imperfection as well (

Figure 4).

Outside of the IDR region, the n

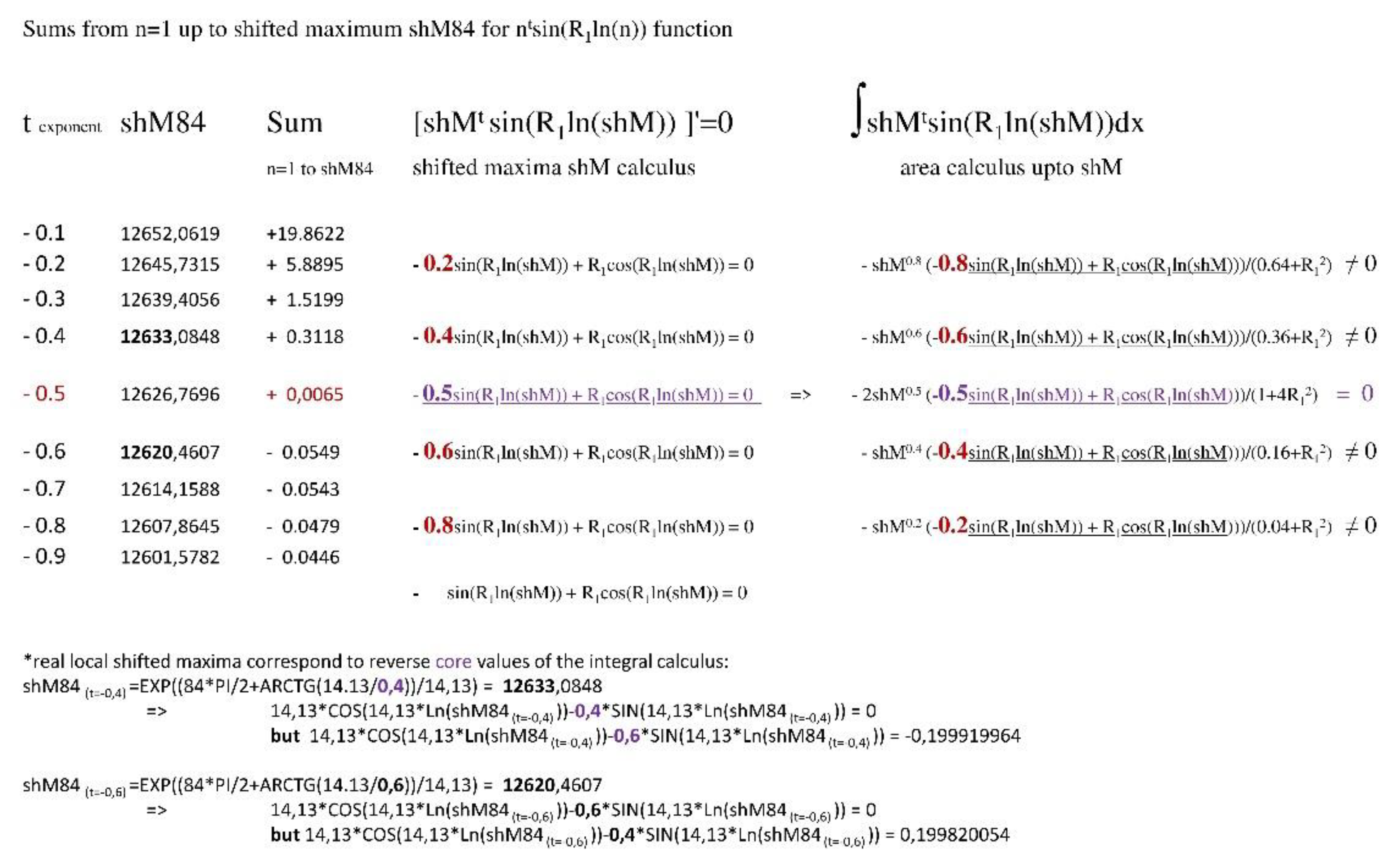

-1/2sin(Rln(n)) continual area-summations to the local minima grow exponentially by exp(π/2R), while the continual area-summations to the local maxima degrease exponentially by exp(-π/2R) and importantly, approach to the zero in the local maxima. This is definitively not truth for other exponents (

Figure 5).

In conclusion, a simple and rational explanation was found in this study for unique position of the Riemann critical line for all non-trivial zeros.

Limitations of This Study and Directions for Future Work

The values of R-constants in Euler–Riemann zeta function represent number distributions, which chaos and harmony reveal as a convergent function along both sin and cos functions at once. The observed mirror effect is an open question for the next.