1. Introduction

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was a wake-up call for the scientific community and global society, resulting in more than 777 million infected individuals and 7 million deaths worldwide [

1]. Very rapidly, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) was isolated, and its genome was sequenced and identified as the cause of COVID-19 [

2]. Intensive research has been conducted to establish the origin of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Various hypotheses have been proposed, including the claims of contaminated bats or pangolins at a seafood market in Wuhan [

3], China, to the potential escape of SARS-CoV-2 from the laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology [

4]. However, the aim of this review was not to confirm the origin of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, epidemics occurred in various parts of the world in 2002-2003 for SARS-CoV [

5]. The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) showed a more local appearance in 2012 [

6]. However, neither SARS-CoV nor MERS-CoV have achieved the same global presence and persistence as SARS-CoV-2 and, therefore, have received less attention. The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 on all continents required drastic action, leading to severe lockdown procedures worldwide. There has also been enormous demands for the development of novel drugs and vaccines against COVID-19. The unprecedented development of vaccines has drastically changed the course of COVID-19, leading to the emergency use authorization (EUA) of vaccines based on mRNA [

7,

8], DNA [

9], proteins or peptides [

10], viral vectors [

11,

12], and whole viruses [

13]. After two years of mass vaccinations, the pandemic was downgraded to an endemic status [

13], allowing life to return to a normal pre-pandemic status.

Unsurprisingly, novel mutant SARS-CoV-2 variants started to emerge within a year of the onset of the pandemic. This was foreseen as SARS-CoV-2 like other RNA viruses are prone to mutate [

14], although the mutation frequency for SARS-CoV-2 is modest compared to many other RNA viruses [

15]. In any case, the emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, have been categorized as variants of concern (VoC), variants of interest (VoI), and variants under monitoring (VuM) [

16]. Typically, the variants can affect infectivity and pathogenicity, which will certainly have an impact on vaccine efficacy, as demonstrated in numerous studies [

14,

15,

17]. For this reason, several approved vaccines have been re-engineered to better suit the modified SARS-CoV-2 variants. In this context, re-engineered vaccines have been designed to target variants such as alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and particularly, the more recent omicron variant [

16]. Recently, a subvariant of omicron, XEC [

16], has emerged, which is the focus of this review.

2. Genomic Landscape

The XEC variant was first identified in Germany in 2024 [

18]. It originates from the recombination of the KS.1.1 and KP3.3 variants, descendants of the omicron variant, which are closely related to the globally dominant JN.1 variant [

19]. The XEC variant has been characterized by its enhanced relative effective reproduction (Re), making it a potential candidate for outcompeting other SARS-CoV-2 lineages [

20]. The XEC variant carries a relatively rare T22N mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein from KS.1.1 and the Q493E mutation from KP3.3 [

20]. Although the T22N mutation has not been thoroughly investigated, the Q493E mutation has been associated with enhanced binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor, rendering XEC potentially more infectious. The combination of Q493E with other mutations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) can potentially contribute to enhanced evasion of immune responses [

20].

In attempts to establish phylogenetic aspects, all available genomes of XEC variants from GISAID showed a genetic makeup closely related to the parenteral donor KP.3.3, including the highest number of mutations [

21]. Furthermore, the application of the FUBAR algorithm for selection pressure tests indicated that the sites under selection were predominantly located in the S protein, providing a significant portion of the genetic variability [

22]. Therefore, it is anticipated that new mutations will modify the genetic makeup of the XEC variant, resulting in new variants replacing the most common JN.1 variant (

https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-171). For the above-mentioned reasons, the phylogeny of parental lineages and the XEC strain can be considered an evolutionary dead-end phenomenon, which most likely does not have the capacity to threaten to result in a wider global presence. Although XEC may show superior infectivity, there is no indication that it causes enhanced symptoms or lethality. Moreover, elevated genomic diversity is not indicative of increased severity or danger of a virus. Even if new variants emerge, T-cells continue to provide significant protection. Despite this, genome-based surveillance is necessary to monitor the evolutionary processes of viruses to correctly respond to any potential threat. According to another study, XEC has the potential to outcompete other major SARS-CoV-2 lineages [

22]. For instance, XEC has shown higher pseudovirus infectivity and immune evasion than KP.3.

3. Epidemiological Dynamics

Transmission and Prevalence: XEC has demonstrated a notable growth advantage over previous sub-variants, leading to its rapid spread across multiple global regions. By late 2024, it accounted for approximately 45% of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the United States, surpassing the prevalence of other strains. In Germany, XEC was responsible for 21% of the infections shortly after its emergence [

23]. The heightened transmissibility is attributed to genetic recombination, which may enhance their ability to evade immune responses.

Clinical Manifestations: The clinical presentation of XEC infections remains consistent with that of previous Omicron variants. Common symptoms include fever, cough, nasal congestion, headaches, and fatigue. Notably, there is no current evidence to suggest that XEC causes more severe illnesses than its predecessors.

Public Health Implications: The emergence of XEC underscores the importance of continuous genomic surveillance for monitoring SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Public health authorities should maintain robust influenza-like illnesses and severe acute respiratory syndrome surveillance systems to promptly detect and respond to such variants. Although the XEC variant exhibits increased transmissibility, the current data do not indicate heightened disease severity. Ongoing monitoring and vaccination efforts are crucial for managing its spread and impact. The key variants of SARS-CoV-2 circulating worldwide are JN.1, BA.2.86, KP.3, KP.2, and XEC, all of which are Omicron descendants [

23]. XEC was identified in May 2024 in Italy. In September 2024, the WHO designated it among VuM [

24]. From the time XEC was detected until epidemiological week 37 of 2024, it had spread to over 27 nations across North America, Europe, and Asia. As of mid-September, the utmost records of XEC cases have been identified in Germany, the United States, France, Denmark, and the UK.

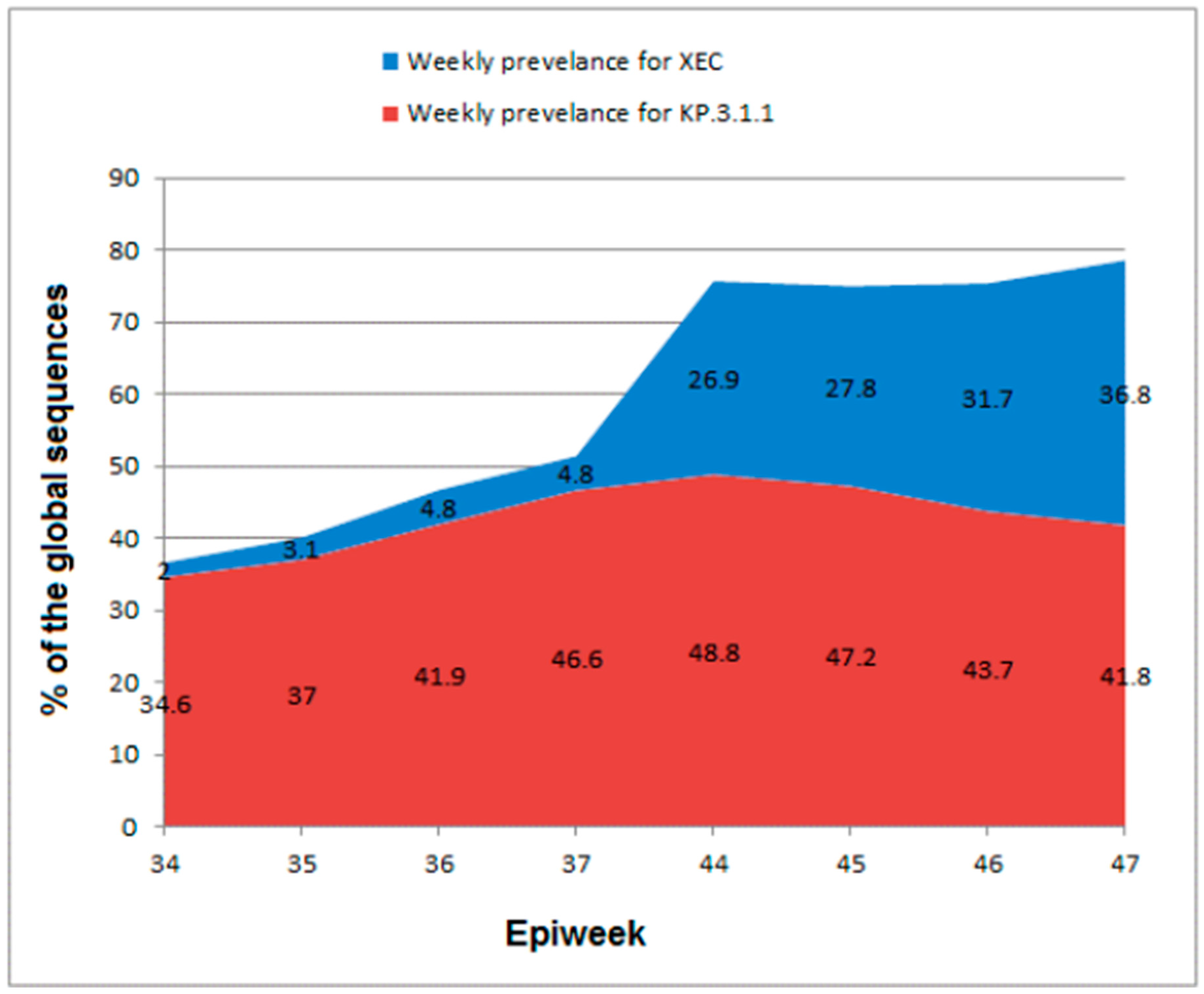

Currently, the WHO is tracking numerous VuM such as JN.1.18, JN.1.7, KP.2, KP.3.1.1, KP.3, and XEC. Among them, XEC is currently the only VuM of SARS-CoV-2, with an increasing prevalence worldwide. Both Omicron sub-variants, XEC and KP.3.1.1, exhibited increasing prevalence globally until the epidemiological week (Epiweek) 44 of 2024, even though at diverse rates, whereas all the other VuM are diminishing (

Table 1). XEC represented 4.8% of the globally submitted sequences to GISAID in Epiweek 37 of 2024 compared to 2.0% in Epiweek 34, but KP.3.1.1 represented 46.6% of the sequences in Epiweek 37 compared to 34.6% in Epiweek 34 (

Table 1).

In Epiweek 47 (November 18–24, 2024), 50 countries submitted 13,331 XEC sequences to GISAID [

24], which accounted for 36.8% of the global sequences. These data suggest a noteworthy increase in the prevalence from 4.8% in week 37 to 26.9% in week 44 (October 28 to November 3, 2024), as illustrated in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. In contrast, KP.3.1.1 declined in prevalence from 48.8% in week 44 to 41.8% in week 47 (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). On November 1, 2024, the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases of the CDC announced that XEC will increase as KP.3.1.1 decreases [

25]. XEC and KP.3.1.1 epidemiological dynamics also displayed remarkable regional variances [

26]. XEC increased more gradually between weeks 34 and 37, mainly in the Americas and Europe. On the contrary, KP.3.1.1 demonstrated robust growth within the same weeks in the Western Pacific and the Americas, although both sub-variants exhibited only an insignificant presence in Southeast Asia (

Table 2).

| VUMs |

Region |

Epiweek 34*

|

Epiweek 37*

|

| XEC |

Europe |

5.3 |

12.0 |

| The Western Pacific |

0.2 |

2.0 |

| The Americas |

0.9% |

2.8% |

| Eastern Mediterranean region, Africa, Southeast Asia |

Not reported |

Not reported |

| KP.3.1.1 |

Europe |

48.2 |

50.4 |

| The Western Pacific |

13.5 |

24.2 |

| The Americas |

34.1 |

49.2 |

| Southeast Asia |

A single reported sequence |

A single reported sequence |

The noteworthy increase in the prevalence of XEC between weeks 44 and 47, along with the steady decrease in KP.3.1.1 prevalence (formerly the most prevalent variant) globally predicts that XEC will soon become the world’s predominant sub-variant of SARS-CoV-2. However, XEC still has a minimal antigenic advantage in escaping preceding immunity, which maintains a low overall risk evaluation for this sub-variant [

26].

3.1. Global Distribution Patterns

After being identified in August 2024 in Berlin, Germany, among COVID-19 samples , XEC emerged in the UK on September 18. On October 26, XEC was spreading in the UK at a high rate (approximately 7% of cases), as stated by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) [

27]. On September 20, 2024, GISAID data pointed out that more than 600 XEC cases have been identified across 27 countries and that XEC is most prevalent in Europe, identified in no less than 13 nations [

28]. This subvariant was the most widespread in France, involving approximately 21% of the sequenced cases of COVID-19. In contrast, approximately 1% of XEC cases were detected in the United States in a week [

29].

In Germany, XEC was first detected in June and was identified two months later. However, it did not appear on the COVID-19 Dashboard of the RobertKoch Institute yet [

30]. It is expected that it will probably never appear, as it is difficult to determine how individual variants can spread. It was not even mentioned by the Robert Koch Institute in its weekly COVID-19 assessment, which was published on September 18, 2024. In Germany, attention is still paid to the most dominant variant, KP.3.1.1, which is considered more transmissible than previous variants. However, by October 2024, XEC had its highest concentration in Germany, with a genomic prevalence of approximately 13% [

30].

By mid-October 2024, XEC had been detected in no less than 29 countries across the globe and 24 states in the United States [

31]. This rapid spread between nations around the world validates the highly contagious potential of this sub-variant (

Table 3). On October 10, 2024, it was stated that XEC, which has already been reported worldwide, also hit Australia [

32]. The Australian Respiratory Surveillance Report announced that there has been an increased percentage of recently sequenced XEC. Approximately 329 sequences of SARS-CoV-2 were collected from August 26 to September 22 and uploaded to the national genomics surveillance platform of Australia (AusTrakka) for COVID. It turned out that 91.5% of these were KP.2, KP.3, and 8.5% were recombinant sublineages of Omicron, including XEC [

33]. The African CDC published a statement on the XEC subvariant on November 4, 2024, revealing that one XEC case was reported in Botswana from a hospitalized traveler from Europe [

34]. The agency also declared that limited sequencing and testing, compared to previous levels, make it challenging to identify the XEC spread in Africa [

35]. It was stated that XEC is a recombinant sub-variant under monitoring by the African CDC in addition to the WHO [

36].

On December 23, 2024, the Ontario COVID-19 Genomics Network revealed in its weekly epidemiological summary on whole genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 that 811 cases were sequenced between December 1 and December 7, 2024, 34.6% of which were XEC and 25.2% were KP.3.1.1 [

37]. The report also demonstrated that XEC remained steady at 34.9% (November 24–30) and 34.6% (December 1–7), whereas KP.3.1.1 declined from 30.8% (November 24–30) to 25.2% (December 1–7) [

21].

3.2. Transmission Efficiency

Although XEC is still a minority variant of SARS-CoV-2 worldwide, it seems to exhibit more growth than other circulating variants. Reports have demonstrated that it spreads more easily than other variants [

26]. It has spread persistently across the world in 2024. Hence, it is predicted that XEC can outpace others in the coming months. Unquestionably, XEC seems to have an advantage compared to other variants at present, explaining its increased percentage of cases. Nonetheless, XEC does not resemble Omicron, which significantly altered the trajectory of the pandemic in ways that were not fully understood at the time. XEC surpasses the other two Omicron sub-variants, KP2 and KP3, which are already more transmissible or superior at escaping the immune system due to the slight differences in their S proteins [

25].

Initial investigational records proposed that XEC displayed distinctive mutations and improved transmissibility, which may participate in comparatively greater evasion of the immune system than KP.3 (parent lineage) [

38,

39,

40]. Nevertheless, there has been no confirmation of a more severe infection than seen for preceding variants of Omicron. The CDC in the United States noted that XEC can escape immunity, and it is more immune-evasive [

30].

Antigenic drift or mutations result in new SARS-CoV-2 variants that appear to alter the immune system. As XEC is primarily based on the recombination between two JN.1 descendant variants it can escape immunity and causes disease. What makes this sub-variant of Omicron more transmittable are the Q493E and T22N mutations in its S protein [

20]. Investigation of pseudoviruses revealed that XEC enhanced evasion of humoral immunity, which is thought to arise from the conformational dynamics in the RBD prompted by the T22N mutation [

20,

41]. Additionally, studies on live viruses confirmed a substantial antibody titer decline from XBB.1.5 and B.1 to XEC and KP.3.1.1 in 68-82-year-old individuals from Norway [

42].

3.3. Comparative Transmissibility Metrics

Regarding growth advantage, the WHO considers XEC as a high level of risk, since this sub-variant is spreading considerably across all regions with steady sharing of sequence data of SARS-CoV-2, while KP.3.1.1 (a previously most prevalent variant) is beginning to decline [

24]. Between weeks 44 and 47, XEC demonstrated an increase from 37.0% to 48.0% in Europe, 14.3% to 35.6% in the Western Pacific region, and from 22.7% to 32.8% in the Americas. On the other hand, only four XEC sequences were detected in the East Mediterranean and the African Regions, and 17 sequences in the Southeast Asia region [

24]. In August 2024, XEC's Re of XEC was 1.13-fold greater than that of KP.3.1.1 [

43]. As of September 3, KP.3.1.1 was detected 14,396 times worldwide, KP.3.3 9 157 times, K.S.1.1 2,650 times , and XEC 95 times (according to data provided by GISAID [

44]. This reflects the dominance of KP.3.1.1. Genomic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario revealed that the lowest percentage of XEC cases were detected in the age group 5-11, while for KP.3.1.1 in the age group 12-19 (

Table 4)

4. Clinical and Immunological Insights

4.1. Symptom Profile Variations

XEC, a recombinant of the Omicron subvariants KS.1.1 and KP3.3, has demonstrated a growth advantage over prior strains, raising concerns about its potential to surpass dominant variants. Notably, its T22N and F59S mutations in the N-terminal domain of the S protein (NTD) may enhance immune evasion, with T22N creating a possible N-linked glycosylation site similar to the DelS31 mutation in KP.3.1.1 [

45]. These evolutionary changes could impact transmissibility and severity [

46].

The symptom profile linked with the XEC subtype of SARS-CoV-2 has raised curiosity, as it emerges amid continued SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although detailed clinical data on XEC have not yet been acquired, preliminary findings indicate that its symptoms may be similar to those of previous Omicron variants. Experts have stated that there is no proof that XEC produces distinct symptoms compared to other circulating SARS-CoV-2 lineages. Although most people infected with XEC recover within a few weeks, there is evidence that some may take longer. This is consistent with prior research revealing differences in symptom intensity and duration across SARS-CoV-2 variants [

47]. Although the symptom profile is similar, some experts believe that the XEC variant may have more severe flu-like symptoms than its predecessors. According to reports, patients may experience increased intensity of symptoms, such as bodily pain and weariness, which might lead to exhaustion. However, there is no compelling evidence that XEC produces more severe illness than previous strains such as Alpha or Delta variants, which have been associated with greater hospitalization rates and lethal outcomes. Patients recovering from Omicron infections have also reported long-term COVID symptoms, such as chronic tiredness and cognitive impairment [

48].

4.2. Immune Response Characteristics

Li et al. [

46] determined that XEC shows a higher infectivity than the parental KP.3 variant, although it is still lower than for the KP.3.1.1 variant in both HEK293T-ACE2 and Calu-3 cells. This conclusion is consistent with the findings from other studies, who found that XEC variant showed reduced infectivity compared to the KP.3.1.1 variant in HOS-ACE2-TMPRSS2 [

49] and Calu-3 cells [

50], as well as comparable infectivity in Vero cells. They also discovered that the single mutation F59S in the NTD accounts for most of the enhanced infectivity, but the T22N mutation in the same domain has no substantial influence, which is supported by other studies [

49]. Deep mutational scanning of the XBB.1.5 S protein indicated that the F59S mutation might provide a moderate increase in ACE2 binding [

51]. However, other studies have shown comparable ACE2 binding across the KP.3, KP.3.1.1, and XEC variants [

50,

52].

Mutations in the NTD that produce additional glycosylation sites are common for both XEC and KP.3.1.1. The DelS31 mutation in KP.3.1.1 is projected to result in a glycosylation site at residue N30, whereas the T22N mutation in XEC is likely to result in a glycosylation site at residue N22. According to Li et al. [

46], ablating the glycosylation site in KP.3.1.1 significantly reduced infectivity while partially restoring, particularly in bivalent vaccines in BA.2.86/JN.1 patient cohorts. These findings are supported by Liu et al., who found that glycosylation in XEC can be inhibited by soluble ACE2 and RBD-targeting monoclonal antibodies [

52]. These results suggest that NTD glycosylation plays a significant role in spike stability, viral infectivity, and neutralizing antibody (nAb). The NTD has no direct contact with the ACE2 receptor but is critical for maintaining the shape and dynamics of the spike protein. Homology modeling revealed that T22N and F59S mutations in the NTD of the XEC S protein may influence spike stability and viral infectivity; however, the precise mechanisms require additional experimental confirmation. The T22N mutation creates an N-linked glycosylation site at position 22, which may impair antibody identification and promote immune evasion [

46].

According to recent research, the XEC variant posesses mutations in its S protein, including F59S and Q493E, which are critical for infectivity. The Q493E mutation is particularly significant because it is associated with a higher binding affinity for the ACE2 receptor, allowing for more viral entry into host cells. This mutation, along with others acquired from its parental lineages, enables XEC to avoid neutralizing antibodies produced by previous infections or immunizations [

53]. Studies have shown that XEC is much less neutralized by antibodies generated from patients previously infected with KP.3.1.1, but is more resistant to sera from KP.3.3 [

54]. This suggests a strong immune evasion capability since mutations in the RBD can synergistically improve both binding affinity and immunological escape [

54]. Furthermore, the concentration of genetic diversity in the S protein implies that lasting evolution may continue to favor such mutations, potentially increasing XEC's frequency and its presence over other variations [

55].

4.3. Potential Impacts on Vaccine Effectiveness

Arora et al. [

50] described the virological characteristics of the XEC lineage and investigated the effect of JN.1-booster vaccination on KP.3.1.1 and XEC neutralization. They discovered that the XEC S protein engaged ACE2 with the same efficacy as the JN.1 and KP.3.1.1 S proteins. The cell entrance was analyzed using S protein-bearing pseudovirus particles, which is a well-established surrogate method for studying SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and neutralization. Pseudovirus particles containing JN.1 (JN.1pp), KP.3.1.1 (KP.3.1.1pp), or XEC S proteins (XECpp) entered Vero kidney cells with equal efficiency, whereas KP.3.1.1pp and XECpp had a lower entry rate into Calu-3 lung cells [

56]. In the same study, the JN.1-adapted mRNA vaccine, bretovameran (developed by Pfizer-BioNTech), enhanced neutralization against the SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC. In a group of 33 vaccinated individuals, neutralization increased dramatically after the booster, with geometric mean titers (GMT) of 2430 for JN.1, 1300 for KP.3.1.1, and 840 for XEC, respectively. Nevertheless, neutralization by KP.3.1.1 and XEC was lower than that by JN.1. In a second cohort of newly infected people without the booster, JN.1 neutralization was similarly more successful than against other variants, demonstrating that vaccination effectiveness against emerging strains is challenging [

56]. Overall, Arora et al. demonstrated that XEC shows stronger pseudovirus infectivity and immune evasion than KP.3. XEC demonstrated stronger immunological resistance to KP.3.3 BTI sera than KP.3.1.1, implying that the greater Re of XEC than KP.3.1.1 is due to this feature and that XEC will soon be the most common SARS-CoV-2 variant worldwide.

Notably, the T22N mutation in the N-terminal domain (NTD) and the Q493E mutation in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the XEC spike (S) protein are associated with immune evasion. In general, mutations within the RBD can alter the structural conformation required for neutralizing antibody recognition, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the immune response. As a result, vaccinated individuals may show reduced protection against infection, although they may still show some immunity against severe COVID-19 [

57].

The ability of XEC to partially escape immune responses raises concerns about the growth of breakthrough infections. As vaccination coverage expands globally, the possibility of encountering variants, such as XEC, may increase the rates of reinfection among vaccinated persons. This scenario has already been described with other variants, in which increased transmissibility mixed with immunological escape increased in the population , despite high vaccination rates. Given the decreased neutralizing efficacy of XEC, there is an urgent need for ongoing research on next-generation vaccines that can elicit broader immune responses capable of combating novel variants.

5. Research Horizons

The emergence of the XEC variant has caused considerable concern in the scientific community owing to its potential impact on public health related to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a new variant, XEC presents unique challenges that require a more in-depth understanding of its genomic and virological properties, modes of transmission, mechanisms of immune evasion, and clinical consequences. Such challenges become more complex in response to questions regarding the long-term consequences of infections caused by XEC, its potential effects on vaccine efficacy, and its psychosocial impact on vulnerable groups [

19,

58].

Here, we attempt to define knowledge gaps, describe new areas of research, and determine potential intervention approaches to mitigate the burden of XEC. By collating evidence on mutations linked to variants, mechanisms of immune evasion, and clinical consequences, researchers and health policymakers can design evidence-based strategies to better monitor surveillance, maximize treatment options, and facilitate vaccine distribution globally. Overall, such priorities are crucial for protecting public health and improving our basic knowledge of the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 [

28,

46].

5.1. Critical Knowledge Gaps

5.1.1. Variant-Specific Virological Characteristics

The mutational pattern of the XEC variant raises questions regarding its biological behavior. S protein mutations, especially in the RBD, the furin cleavage site, and the NTD, are thought to increase ACE2 binding affinity, alter cell tropism, and potentially facilitate syncytia formation ([Li et al., 2024]). Mutations at glycosylation sites in the NTD can potentially affect immune evasion and infectivity, although the exact mechanisms are poorly understood [

54,

59].

Structural characterization through cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography remains limited, and the major antigenic epitopes of XEC are poorly characterized. It also remains unknown whether XEC arose through recombination events between circulating lineages or prolonged intra-host evolution, and it is necessary to clarify its evolutionary history for predictive modeling of emerging variants [

60].

5.1.2. Immune Evasion Dynamics

A central concern with XEC is its potential to evade preexisting immunity. While early data indicate reduced neutralization by previously induced infection or vaccine antibodies, the extent of escape from hybrid immunity (post-vaccination and infection) and next-generation vaccines for Omicron subvariants, such as XBB.1.5, needs to be elucidated [

61,

62]. Furthermore, T-cell responses may be compromised if XEC carry mutations that annihilate the conserved epitopes. Recent studies have also indicated that NTD glycosylation alterations can confer additional immune escape advantages [

46]. However, detailed examinations of the protective thresholds for neutralizing antibodies, mucosal IgA responses, and T-cell cross-protection remain incomplete.

5.1.3. Pathogenesis and Clinical Impact

The pathogenicity of XEC compared to earlier variants is a continuing line of research. There are open questions regarding whether it shows increased replication in lower respiratory tissue, which would aggravate disease severity, or whether it expresses neurotropic tendencies that would be responsible for the neurological complications observed in some cases of COVID-19. In addition, its association with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) or Long COVID has yet to be explored [

63]. There is evidence of a shift in the clinical presentation and severity of disease caused by variants of the Omicron lineage [

64]. The extent to which these changes apply to XEC requires new clinical indicators and biomarkers remains unclear. The established clinical indicators may be invalid, indicating the need for new diagnostic and prognostic tools.

5.1.4. Transmission and Epidemiologic Fitness

XEC appears to have a reproductive advantage in some places; however, the mechanisms of its rapid spread are not fully understood. These include aerosol stabilization, heightened aerosol transmissivity during asymptomatic or presymptomatic carriage, and super-spreader events facilitated by specific social behaviors. Accurate measurement of its reproduction number (Rt) and identification of transmission hotspots are crucial for the design of evidence-based containment strategies [

59,

65].

5.1.5. Geographic and Host-Specific Heterogeneity

Discrepancies in surveillance hinder the construction of a complete picture of the global distribution of XEC. Low-resource areas, immunocompromised patients, and suspected reservoirs of wildlife and domesticated animals continue to be insufficiently sampled [

66]. The process of reverse spillovers to wildlife can lead to secondary reservoirs, making eradication even more challenging. The different patterns of immunity across various human populations underscore the need for analysis in each context to facilitate fair healthcare planning [

67].

5.1.6. Long-Term Sequelae and Psychosocial Impact

The long-term effects of XEC infection, especially in patients with underlying health conditions, should be carefully monitored. Recent disease variants have been linked to long-term COVID-19 and post-acute sequelae, sparking fears that XEC produces similar or even more serious aftereffects [

63]. In addition, the emergence of new variants often brings heightened public concerns, making it even more crucial to address the psychosocial aspects of XEC using evidence-informed communication strategies and mental health support programs [

68].

5.2. Emerging Research Priorities

5.2.1. Enhanced Molecular Surveillance

The worldwide expansion of genomic surveillance networks, most critically in low-resource settings, is crucial for tracking the dissemination of XEC and detecting new sublineages [

69]. Wastewater surveillance is an affordable supplement to clinical diagnosis, enabling early detection of community outbreaks. The combination of AI-based predictive modeling with up-to-date sequencing data can greatly enhance situational awareness and allow for timely public health action [

70].

5.2.2. In Vitro and In Vivo Models

There is a need to define sufficient experimental models to study the infectivity and pathogenicity of XEC. Pseudovirus-neutralizing assays using sera of vaccine recipients, convalescents, and booster recipients can yield estimates of protection efficacy provided by antibodies. Human airway organoids, in conjunction with other models, such as hamsters and ACE2-transgenic mice, are crucial for investigating replication kinetics, tropism to different tissues, and concomitant clinical presentations [

71,

72].

5.2.3. Immune Correlates of Protection

There is a need to define neutralizing antibody protection thresholds and mucosal IgA immunity to assess vaccine efficacy. In parallel, the identification of conserved CD8+ T-cell-defined epitopes in response to S protein mutations will help to define the role of cellular immunity in averting severe disease. Such observations will sharpen the immunological correlates of protection and inform the design of next-generation vaccines [

73,

74].

5.2.4. Antiviral and Therapeutic Resistance

Assessment of the efficacy of current antiviral drugs against XEC requires careful analysis. Mutations in the primary protease (3CLpro) or RNA-dependent RNA polymerase can result in resistance to drugs such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (paxlovid) or remdesivir [

75]. Broad-spectrum protease inhibitors and cellular or conserved process-based therapies hold promise; however, careful validation via phase I to IV clinical studies is required [

76].

5.2.5. Longitudinal Clinical Studies

Population-based cohort studies are paramount in defining the clinical course of XEC in various groups of patients, including children and patients with comorbidities (e.g., diabetes or COPD). Monitoring patterns of recovery and chronic outcomes will define the wide health consequences, contribute to clinical management strategies, and improve the quality of patient counseling programs [

77,

78].

5.2.6. Integrating Computational Approaches

Sophisticated computational systems and informative graphs hold great promise to deepen our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of XEC, facilitate the expedited identification of drug targets, and predict evolutionary patterns. Using big data analysis, researchers can identify key intervention points for treatment and quickly adapt to constantly evolving patterns of viral behavior [

79].

5.3. Potential Intervention Strategies

5.3.1. Optimized Vaccine Development

Modification of mRNA vaccines to use XEC-specific S protein antigens or conserved pan-coronavirus epitopes is a logical next step. In addition, intranasal vaccine strategies, such as protein nanoparticles or adenoviral vectors, provide the added benefit of inducing mucosal immunity, which is the first line of defense against respiratory infection. Further use of self-replicating RNA-based vacccines will allow the administration of reduced vaccine doses potentially decreasing adverse events and lowering vaccine production costs[

80]. Proper regulation and robust manufacturing infrastructure will be crucial for enabling quick deployment [

80,

81].

5.3.2. Next-Generation Antivirals

Broad-spectrum protease inhibitors targeting highly conserved viral enzymes such as 3CLpro, when combined with host-targeted pharmacological drugs such as TMPRSS2 inhibitors, can help curtail resistance developed against variants [

75]. The use of direct-acting antivirals in combination with drugs that affect host factors can greatly reduce resistance, especially in immunocompromised patients receiving protracted treatment regimens [

82].

5.3.3. Monoclonal Antibody Therapies

There is a need to engineer monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with activity against emerging variants to reduce the severity of disease and mortality. Targeted approaches, such as yeast or phage display libraries, can identify mAbs against structurally constrained and less mutation-prone regions of the S protein. Periodic updating of therapies to match the XEC mutational profile is the basis for long-term efficacy [

83,

84].

5.3.4. Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs)

Physical distancing, masking, and improved indoor air quality via ventilation and filtration are effective in preventing respiratory transmission [

85]. High-filtration masks (N95 and KF94) offer additional protection in high-risk settings. NPIs can be adapted to the specific features of XEC, including its transmissibility and immune escape potential, to optimize public health gains [

86]. The NPIs played an important role during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the time when now vaccines were available. It is therefore absolutely necessary that NPIs are developed and rapidly available in case of emerging new variants or pandemics.

5.3.5. One Health Approach to Understanding the XEC Mutation of COVID-19

The exploration of potential reservoirs of zoonosis and reverse spillover events is key to preventing further adaptation of viruses and the resulting pandemics. Routine surveillance of wildlife, domestic animals, and ecological interfaces can help identify areas at high risk for interspecies transfer. This requires interdisciplinary cooperation between virologists, epidemiologists, veterinarians, and ecologists [

87,

88].

5.3.6. Global Equity Initiatives and Rapid-Response Systems

The XEC variant serves as yet another example of the almost never-ending adaptability of SARS-CoV-2 and presents a challenge to global public health to stem and manage the pandemic [

28,

30]. Filling the critical knowledge gaps from variant-specific virological properties to longer-term clinical sequelae will necessitate collective efforts across multiple disciplines, including virology, immunology, epidemiology, computational modeling, and social sciences [

20,

25]. Importantly, the combination of robust enhanced genomic surveillance, next-generation vaccine platforms, and integrated therapeutic strategies can all reduce the morbidity, mortality and socioeconomic determinants of XEC [

28,

31].

Researchers and policymakers should not allow uncertainty to paralyze but instead leverage equitable healthcare measures and international collaboration to turn uncertainty into actionable insights while its advancements are deployed to the populations — including those outside their geographic or socioeconomic backgrounds [

89]. The insights gained from XEC will not only enhance our current response to COVID-19 but also lay the groundwork for more robust systems capable of addressing future variants and novel emerging infectious agents. These systems will be better prepared to combat emerging pathogens and adapt to evolving health challenges [

90].

6. Conclusions

The emergence of the XEC variant underscores the continued capability of SARS-CoV-2 to evolve and adapt, even during a global trend toward endemicity. Higher reproduction rates, adaptations of the S protein to enable immune evasion, and instances of recombination, such as the Q493E mutation, pose a challenge to vaccine and treatment efficacy. There is currently no evidence to link XEC to increased severity or mortality, yet resistance to neutralizing antibodies combined with potential chronic reservoirs in human hosts and animals require close surveillance and quick response mechanisms.

From a clinical point of view, the associated symptomatology of XEC is largely identical to that of other subvariants of Omicron, yet new evidence suggests that new glycosylation sites and altered receptor-binding interfaces affect infectivity, pathogenicity, and long-term effects. Such aspects highlight the continued need for longitudinal cohorts that can illuminate the entire range of clinical implications of XEC, especially in vulnerable groups such as those with compromised immunity and underlying health status. In addition, the psychosocial impact of emerging variants in the form of heightened anxiety and changed health-seeking behavior underscores the need to enact risk communication approaches that are tailored to different demographic groups. In the future, pandemic readiness at a global scale will require a unifying effort that encompasses large-scale molecular surveillance, novel vaccine design, and more expansive studies of antiviral drugs and monoclonal antibodies. Significantly, a "One Health" approach that addresses human, animal, and environmental health can help to avert zoonotic spillovers and manage consequent outbreak events. By capitalizing on knowledge gained during the XEC experience and encouraging multidisciplinary cooperation between virologists, immunologists, epidemiologists, clinicians, and policymakers, the scientific community can build stronger healthcare infrastructures. In the end, such preventive efforts not just mitigate the health threats of XEC but also provide a roadmap to a more resilient and equitable response to future public health challenges.

Authors contribution

A.A.A.A. and K.L. conceptualized the study and designed the review framework. A.H.-J. and N.A.E.-B. conducted the literature search and curated relevant data. D.N. and S.S.H. contributed to data analysis and synthesis of key findings. A.R.-C. and E.M.R. critically revised the manuscript and ensured methodological rigor. V.N.U. provided expert insights and contributed to final manuscript editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

No new data was generated from this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have nothing to declare.

References

- Organization: W.H. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 12/02/2025).

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The lancet 2020, 395, 565-574. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature medicine 2020, 26, 450-452. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.C.; Goldstein, S.A.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Robertson, D.L.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Wertheim, J.O.; Anthony, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; Boni, M.F.; Doherty, P.C. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review. Cell 2021, 184, 4848-4856.

- Anderson, R.M.; Fraser, C.; Ghani, A.C.; Donnelly, C.A.; Riley, S.; Ferguson, N.M.; Leung, G.M.; Lam, T.H.; Hedley, A.J. Epidemiology, transmission dynamics and control of SARS: the 2002–2003 epidemic. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2004, 359, 1091-1105.

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. New England Journal of Medicine 2012, 367, 1814-1820. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1211721.

- Food; Drug, A. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. FDA News Release 2021.

- Administration, U.S.F.a.D. FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid (accessed on 24/01/2025).

- Mallapaty, S. India’s DNA Covid vaccine is a first—more are coming. Nature 2021, 597, 161-162.

- Yu, D. China grants emergency use of new vaccines as it eases COVID-19 policy. BioWorld 2022, 13.

- Covid, E.M.A. Vaccine AstraZeneca. 2021.

- Eua, E.U.A.; Covid, M. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine (vaccination providers).

- Taylor, A. WHO grants emergency use authorization for Chinese-made Sinopharm coronavirus vaccine. The Washington Post 2021, 1.

- Lundstrom, K. Role of Nucleic Acid Vaccines for the Management of Emerging Variants of SARS-CoV-2. In SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Global Population Vulnerability; Apple Academic Press: 2023; pp. 285-316.

- Callaway, E. Making sense of coronavirus mutations. Nature 2020, 585, 174-177.

- Choi, J.Y.; Smith, D.M. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Yonsei medical journal 2021, 62, 961.

- Wiegand, T.; Nemudryi, A.; Nemudraia, A.; McVey, A.; Little, A.; Taylor, D.N.; Walk, S.T.; Wiedenheft, B. The rise and fall of SARS-CoV-2 variants and ongoing diversification of omicron. Viruses 2022, 14, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP. 3.1. 1 variant. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, e609.

- Li, P.; Faraone, J.N.; Hsu, C.C.; Chamblee, M.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Xu, Y.; Carlin, C.; Horowitz, J.C.; Mallampalli, R.K. Immune Evasion, Cell-Cell Fusion, and Spike Stability of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC Variant: Role of Glycosylation Mutations at the N-terminal Domain. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-2011.

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Genetic variability of the recombinant SARS-CoV-2 XEC: Is it a new evolutionary dead-end lineage? New Microbes and New Infections 2024, 62, 101520.

- Gangavarapu, K.; Latif, A.A.; Mullen, J.L.; Alkuzweny, M.; Hufbauer, E.; Tsueng, G.; Haag, E.; Zeller, M.; Aceves, C.M.; Zaiets, K. Outbreak. info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nature Methods 2023, 20, 512-522. [CrossRef]

- Murrell, B.; Moola, S.; Mabona, A.; Weighill, T.; Sheward, D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Scheffler, K. FUBAR: a fast, unconstrained bayesian approximation for inferring selection. Molecular biology and evolution 2013, 30, 1196-1205. [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. World Health Organization Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants.

- World Health, O. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Epidemiological Updates and Monthly Operational Updates. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 13/02/2025).

- CDC. SARS-CoV-2 Variant XEC Increases as KP.3.1.1 Slows. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncird/whats-new/sars-cov-2-variant-xec-increases-as-kp-3-1-1-slows.html (accessed on 12/02/2025).

- World Health, O. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update, 9 March 2021. 2021.

- Souza, U.J.B.d.; Spilki, F.R.; Tanuri, A.; Roehe, P.M.; Campos, F.S. Two Years of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Genomic Evolution in Brazil (2022–2024): Subvariant Tracking and Assessment of Regional Sequencing Efforts. Viruses 2025, 17, 64. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, F.; Branda, F.; Ceccarelli, G.; Romano, C.; Locci, C.; Pascale, N.; Azzena, I.; Fiori, P.L.; Casu, M.; Pascarella, S. SARS-CoV-2 XEC: A Genome-Based Survey. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 253. [CrossRef]

- Tracker, C.D. COVID Data Tracker. Center for Disease Control and Prevention [online] https://covid. cdc. gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home (accessed 12 June 2022) 2022.

- Rubin, R. What to Know About XEC, the New SARS-CoV-2 Variant Expected to Dominate Winter’s COVID-19 Wave. JAMA 2024, 332, 1961-1962.

- Rizzo-Valente, V.S.; Oliveira, J.S.; Vizzoni, V.F.; Rizzo-Valente, V.S.; do Brasil, M.; Oliveira, J.S. XEC: international spread of a new sublineage of Omicron SARS-CoV-2. 2024.

- Seemann, T.; Lane, C.R.; Sherry, N.L.; Duchene, S.; Gonçalves da Silva, A.; Caly, L.; Sait, M.; Ballard, S.A.; Horan, K.; Schultz, M.B. Tracking the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia using genomics. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Gao, G.F.; Shi, W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 600, 408-418. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.K. Genesis of Recombinant XEC Variant and Comparable SWISS-Modelling of Spike of LB. 1.7 and KP. 3.1. 1 Subvariants Coronaviruses. SunText Rev Virol 2024, 5, 152. [CrossRef]

- Tegally, H.; San, J.E.; Cotten, M.; Moir, M.; Tegomoh, B.; Mboowa, G.; Martin, D.P.; Baxter, C.; Lambisia, A.W.; Diallo, A. The evolving SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Africa: Insights from rapidly expanding genomic surveillance. Science 2022, 378, eabq5358. [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.A.; Simons, L.M.; Adewumi, O.M.; Fowotade, A.A.; Omoruyi, E.C.; Adeniji, J.A.; Olayinka, O.A.; Dean, T.J.; Zayas, J.; Bhimalli, P.P. Multiple expansions of globally uncommon SARS-CoV-2 lineages in Nigeria. Nature communications 2022, 13, 688. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.C. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants: circulation of omicron lineages—United States, January 2022–May 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023, 72.

- Hussain, A.; Hussain, A.; Eldaif, W.A.H.; Rashid, M. The XEC COVID-19 Variant: A Global Threat Demanding Immediate Action. 2024.

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. On the new SARS-CoV-2 variant KP. 3.1. 1: focus on its genetic potential. Infectious Diseases 2024, 56, 903-906.

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Features of the SARS-CoV-2 KP. 3 variant mutations. Infectious Diseases 2024, 56, 894-896. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Mellis, I.A.; Wu, M.; Mohri, H.; Gherasim, C.; Valdez, R.; Purpura, L.J.; Yin, M.T.; Gordon, A. Antibody evasiveness of SARS-CoV-2 subvariants KP. 3.1. 1 and XEC. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-2011. [CrossRef]

- Fossum, E.; Vikse, E.L.; Robertson, A.H.; Wolf, A.-S.; Rohringer, A.; Trogstad, L.; Mjaaland, S.; Hungnes, O.; Bragstad, K. Low levels of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 KP. 3.1. 1 and XEC in serum from seniors in May 2024. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-2011.

- Kaku, Y.; Uriu, K.; Kosugi, Y.; Okumura, K.; Yamasoba, D.; Uwamino, Y.; Kuramochi, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Asakura, H. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP. 2 variant. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, e416. [CrossRef]

- GISAID. Tracking of hCoV-19 Variants. Available online: https://gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/ (accessed on 13/02/2025).

- Waafira, A.; Subbaram, K.; Faiz, R.; Naher, Z.U.; Manandhar, P.L.; Ali, S. A new and more contagious XEC subvariant of SARS-CoV-2 may lead to massive increase in COVID-19 cases. New Microbes and New Infections 2024, 62, 101517. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Faraone, J.N.; Hsu, C.C.; Chamblee, M.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.M.; Xu, Y.; Carlin, C.; Horowitz, J.C.; Mallampalli, R.K.; et al. Immune Evasion, Cell-Cell Fusion, and Spike Stability of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC Variant: Role of Glycosylation Mutations at the N-terminal Domain. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Byrd, J.B.; Yu, H.; Ye, X.; He, Y. Differential COVID-19 Symptoms Given Pandemic Locations, Time, and Comorbidities During the Early Pandemic. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Omori, T.; Hanafusa, M.; Kondo, N.; Miyazaki, Y.; Okada, S.; Fujiwara, T.; Kuramochi, J. Specific sequelae symptoms of COVID-19 of Omicron variant in comparison with non-COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study in Japan. J Thorac Dis 2024, 16, 3170-3180. [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Kawakubo, S.; Uriu, K.; Chen, L.; Kosugi, Y.; Uwamino, Y.; Begum, M.M.; Leong, S.; Ikeda, T.; et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC variant. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, e736. [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Happle, C.; Kempf, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Stankov, M.V.; Dopfer-Jablonka, A.; Behrens, G.M.N.; Pöhlmann, S.; Hoffmann, M. Impact of JN.1 booster vaccination on neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, e732-e733. [CrossRef]

- Dadonaite, B.; Brown, J.; McMahon, T.E.; Farrell, A.G.; Figgins, M.D.; Asarnow, D.; Stewart, C.; Lee, J.; Logue, J.; Bedford, T.; et al. Spike deep mutational scanning helps predict success of SARS-CoV-2 clades. Nature 2024, 631, 617-626. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Song, W.; Wang, P.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Enhanced immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC through N-terminal domain mutations. Lancet Infect Dis 2025, 25, e6-e7. [CrossRef]

- Waafira, A.; Subbaram, K.; Faiz, R.; Naher, Z.U.; Manandhar, P.L.; Ali, S. A new and more contagious XEC subvariant of SARS-CoV-2 may lead to massive increase in COVID-19 cases. New Microbes New Infect 2024, 62, 101517. [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Genetic variability of the recombinant SARS-CoV-2 XEC: Is it a new evolutionary dead-end lineage? New Microbes New Infect 2024, 62, 101520. [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; Robertson, D.L. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162-177. [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Happle, C.; Kempf, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Stankov, M.V.; Dopfer-Jablonka, A.; Behrens, G.M.N.; Pöhlmann, S.; Hoffmann, M. Impact of JN.1 booster vaccination on neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, e732-e733. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chuang, C.H.; Shen, T.F.; Lin, C.S.; Yang, H.P.; Li, H.C.; Chen, C.L.; Lin, I.F.; Chiu, C.H. Risk reduction analysis of mix-and-match vaccination strategy in healthcare workers during SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant predominant period: A multi-center cohort study in Taiwan. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023, 19, 2237387. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sarkar, M.; Yurkina, M.F.; Gnanaraj, R.; Martínez, D.J.G.; Pisfil-Farroñay, Y.A.; Chaudhary, L.; Agrawal, P.; Kaushal, G.P.; Mbwogge, M. Impact of Emerging COVID-19 variants on psychosocial health: A Systematic Review. medRxiv 2023, 2023-2007. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Uriu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 LP. 8.1 variant. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S.C.; Ando, N. X-rays in the Cryo-Electron Microscopy Era: Structural Biology's Dynamic Future. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 277-285. [CrossRef]

- Link-Gelles, R. Early estimates of updated 2023–2024 (monovalent XBB. 1.5) COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection attributable to co-circulating Omicron variants among immunocompetent adults—Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, September 2023–January 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2024, 73.

- Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Ma, W.; Li, X.; Wei, K.; Xie, F.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Li, C. Enhanced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variant BA. 2.86 and XBB sub-lineages by a tetravalent COVID-19 vaccine booster. Cell host & microbe 2024, 32, 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Elneima, O.; Hurst, J.R.; Echevarria, C.; Quint, J.K.; Walker, S.; Siddiqui, S.; Novotny, P.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Brown, J.S.; Shankar-Hari, M. Long-term impact of COVID-19 hospitalisation among individuals with pre-existing airway diseases in the UK: a multicentre, longitudinal cohort study–PHOSP-COVID. ERJ Open Research 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacharya, M.; Nag, S.; Dhama, K.; Chakraborty, C. A Detailed Overview of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron: Its Sub-Variants, Mutations and Pathophysiology, Clinical Characteristics, Immunological Landscape, Immune Escape, and Therapies. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. Risk evaluation of for SARS-CoV-2 Variant Under Monitoring: XEC. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/risk-evaluation-of-for-sars-cov-2-variant-under-monitoring-xec (accessed on 12/02/2025).

- St. Louis, M.E.; Walke, H.; Perry, H.; Nsubuga, P.; White, M.E.; Dowell, S. 357Surveillance in Low-Resource Settings: Challenges and Opportunities in the Current Context of Global Health. Principles & Practice of Public Health Surveillance 2010, 0. [CrossRef]

- Mack, A.; Choffnes, E.R.; Sparling, P.F.; Hamburg, M.A.; Lemon, S.M. Global Infectious Disease Surveillance and Detection: Assessing the Challengesâ¬" Finding Solutions: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: 2007.

- Adesola, R.O.; Idris, I. Global health alert on the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2024, 48, 131. [CrossRef]

- Esonova, G.; Abdurakhimov, A.; Ibragimova, S.; Kurmaeva, D.; Gulomov, J.; Mirazimov, D.; Sohibnazarova, K.; Abdullaev, A.; Turdikulova, S.; Dalimova, D. Complete genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 strains that were circulating in Uzbekistan over the course of four pandemic waves. PloS one 2024, 19, e0298940. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E.; Medicine. Wastewater-based disease surveillance for public health action. 2023.

- Bocharov, G.; Volpert, V.; Ludewig, B.; Meyerhans, A. Modelling of Experimental Infections; Mathematical Immunology of Virus Infections. 2018 Jun 13:97-152. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, S.A.; Blaizot, S.; Hens, N. Mathematical models used to inform study design or surveillance systems in infectious diseases: a systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases 2017, 17, 775. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, D.S.; Schlub, T.E.; Cromer, D.; Steain, M.; Fong, Y.; Gilbert, P.B.; Subbarao, K.; Triccas, J.A.; Kent, S.J.; Davenport, M.P. Correlates of Protection, Thresholds of Protection, and Immunobridging among Persons with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 381-388. [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Cai, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, A.; Li, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; et al. In vivo determination of protective antibody thresholds for SARS-CoV-2 variants using mouse models. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2025, 14, 2459140. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Casner, R.G.; Yu, J.; Nair, M.S.; Ho, J.; Reddem, E.R.; Tzang, C.C.; Huang, Y.; Shapiro, L. Optimizing a Human Monoclonal Antibody for Better Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-2012.

- Hashemian, S.M.R.; Sheida, A.; Taghizadieh, M.; Memar, M.Y.; Hamblin, M.R.; Bannazadeh Baghi, H.; Sadri Nahand, J.; Asemi, Z.; Mirzaei, H. Paxlovid (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir): A new approach to Covid-19 therapy? Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114367. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Upshur, R.; Donnelly, P.; Bharmal, A.; Wei, X.; Feng, P.; Brown, A.D. A population-based approach to integrated healthcare delivery: a scoping review of clinical care and public health collaboration. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 708. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kattan, M.W. Cohort Studies: Design, Analysis, and Reporting. Chest 2020, 158, S72-S78. [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Fernández, D.; Baksi, S.; Schultz, B.; Gadiya, Y.; Karki, R.; Raschka, T.; Ebeling, C.; Hofmann-Apitius, M.; Kodamullil, A.T. COVID-19 Knowledge Graph: a computable, multi-modal, cause-and-effect knowledge model of COVID-19 pathophysiology. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1332-1334. [CrossRef]

- Vasireddy, D.; Vanaparthy, R.; Mohan, G.; Malayala, S.V.; Atluri, P. Review of COVID-19 Variants and COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy: What the Clinician Should Know? J Clin Med Res 2021, 13, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Forchette, L.; Sebastian, W.; Liu, T. A Comprehensive Review of COVID-19 Virology, Vaccines, Variants, and Therapeutics. Curr Med Sci 2021, 41, 1037-1051. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vargas, J.; Worrall, L.J.; Olmstead, A.D.; Ton, A.-T.; Lee, J.; Villanueva, I.; Thompson, C.A.H.; Dudek, S.; Ennis, S.; Smith, J.R.; et al. A novel class of broad-spectrum active-site-directed 3C-like protease inhibitors with nanomolar antiviral activity against highly immune-evasive SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2023, 12, 2246594. [CrossRef]

- Büyükköroğlu, G.; Şenel, B. Chapter 16 - Engineering Monoclonal Antibodies: Production and Applications. In Omics Technologies and Bio-Engineering, Barh, D., Azevedo, V., Eds.; Academic Press: 2018; pp. 353-389.

- Stone, C.A.; Spiller, B.W.; Smith, S.A. Engineering therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024, 153, 539-548. [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.; Akl, E.A.; Duda, S.; Solo, K.; Yaacoub, S.; Schünemann, H.J.; El-Harakeh, A.; Bognanni, A.; Lotfi, T.; Loeb, M. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet 2020, 395, 1973-1987.

- Um, S.; Lee, R.S. Effects of KF94 Face Mask on Cardiopulmonary Function and Subjective Sensation During Graded Exercise: A Comparison of KF94 2D and 3D Face Masks. 2024; pp. 302-312.

- Bhatia, B.; Sonar, S.; Khan, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Pandemic-Proofing: Intercepting Zoonotic Spillover Events. Pathogens 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pauciullo, S.; Zulian, V.; La Frazia, S.; Paci, P.; Garbuglia, A.R. Spillover: Mechanisms, Genetic Barriers, and the Role of Reservoirs in Emerging Pathogens. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.T.; Larson, J.C.; Buckingham, S.L.; Maton, K.I.; Crowley, D.M. Bridging the research-policy divide: Pathways to engagement and skill development. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 434-441. [CrossRef]

- Françoise, M.; Frambourt, C.; Goodwin, P.; Haggerty, F.; Jacques, M.; Lama, M.-L.; Leroy, C.; Martin, A.; Calderon, R.M.; Robert, J.; et al. Evidence based policy making during times of uncertainty through the lens of future policy makers: four recommendations to harmonise and guide health policy making in the future. Archives of Public Health 2022, 80, 140. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).