1. Introduction

Human beings naturally express emotions through diverse behavioral signals, including linguistic expressions and vocal characteristics [

1,

17]. Text, as one of the most prominent modalities, plays a vital role in encoding affective content via lexical choice, syntactic structure, and semantic nuance [

12]. Yet, the written or transcribed textual content often lacks the expressive prosody and nuanced delivery found in spoken language, which limits its capacity to fully convey emotional intent in isolation. As such, leveraging additional modalities like audio becomes essential.

Audio contributes a unique set of paralinguistic features that reflect speaker emotions through variations in pitch, loudness, speaking rate, and energy dynamics [

5,

18]. These features offer essential cues that help disambiguate emotionally ambiguous utterances. For instance, the phrase “Are you sure?” can carry drastically different sentiments—ranging from sarcasm to excitement—depending on the speaker’s tone and delivery. Audio thus provides the necessary disambiguation when textual information is inconclusive.

The synergistic fusion of text and audio has long been a goal of multimodal sentiment analysis. However, most existing fusion techniques are hindered by their reliance on temporally aligned multimodal inputs [

24]. In practice, spoken words and their corresponding audio signals often do not align perfectly at the word or frame level. This temporal misalignment disrupts crossmodal correspondence, thereby weakening the overall fusion process. Previous methods such as tensor-based fusion [

19] and low-rank multimodal decomposition [

7] have attempted to address multimodal integration, but they assume rigid synchrony and may overlook the distinct nature of each modality.

Further advances such as multistage fusion architectures [

6] have made strides by decomposing the interaction process into sequential stages. However, these methods still depend on pre-aligned sequences and tend to obscure unimodal identity during fusion. As a result, they may inadvertently suppress meaningful signals from individual modalities, especially when one modality is more expressive than the other in certain contexts.

To overcome these limitations, we introduce DIFERNet, a dynamic and interaction-focused representation network tailored for asynchronous text-audio fusion. DIFERNet is designed with the objective of (1) maximizing the exploitation of intermodal interactions while (2) preserving the integrity of unimodal streams. This dual objective ensures that the fused representation is not only informative but also resilient to misalignment artifacts. Our method diverges from rigid fusion schemes by incorporating a self-adjusting transformer module that iteratively refines fusion embeddings using unimodal guidance.

Our pipeline begins with projecting modality-specific features into a common latent space using a crossmodal alignment transformation. This step ensures dimensional homogeneity and semantic compatibility. Subsequently, we introduce an interaction-guided attention mechanism that enables mutual conditioning between text and audio. This attention computes interdependency matrices that weight the importance of tokens or acoustic segments relative to their crossmodal counterparts.

The heart of DIFERNet lies in the dynamic fusion adjustment transformer. This module treats each unimodal representation as a corrective signal, rebalancing the initial fusion to emphasize contextually dominant cues. Such a mechanism ensures that text and audio can independently reinforce or modulate the joint representation, leading to a more expressive embedding. As a theoretical foundation, we define the correction process via a weighted update.

We validate our model on the CMU-MOSI [

22] and CMU-MOSEI [

23] datasets, which are widely recognized benchmarks for multimodal sentiment analysis. DIFERNet demonstrates consistent superiority over competitive baselines, with gains ranging from

to

across evaluation metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, and mean absolute error. Additionally, error analysis reveals that DIFERNet excels in correctly classifying emotionally subtle or ambiguous samples by leveraging the rich interaction between modalities.

In summary, our contributions are threefold:

- –

We propose DIFERNet, a novel framework capable of learning robust fusion representations from unaligned text and audio inputs by emphasizing dynamic intermodal interaction.

- –

A new transformer-based correction mechanism is introduced to adaptively refine fusion features while preserving essential unimodal semantics.

- –

We conduct extensive evaluations on benchmark datasets, where DIFERNet achieves state-of-the-art performance and demonstrates superior capability in handling asynchronous multimodal data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Advancements in Multimodal Sentiment Analysis

Multimodal sentiment analysis (MSA) is a rapidly evolving subfield in artificial intelligence that endeavors to decode emotional signals by integrating information from various modalities such as text, audio, and video [

16]. The rationale behind multimodal fusion lies in the hypothesis that each modality carries complementary aspects of sentiment—text delivers explicit semantic content, audio reflects prosodic and paralinguistic cues, while video provides facial expressions and gestures. Harnessing the synergy among these modalities has the potential to provide machines with a more holistic emotional understanding. Given the increasing importance of empathetic AI systems, MSA has attracted considerable research interest.

Early approaches to MSA emphasized simple concatenation of modality-specific features. For example, Williams et al. [

15] adopted an early fusion strategy, combining feature vectors extracted from multiple modalities before feeding them into downstream models. This method yielded substantial performance gains over unimodal baselines, highlighting the benefits of multimodal learning. Nevertheless, early fusion often suffers from the heterogeneity of feature distributions and fails to exploit deeper intermodal dependencies.

To address this, more sophisticated frameworks have emerged. Zadeh et al. [

21] proposed a hybrid architecture that utilizes a multi-attention block along with long-short term memory units to discover latent interactions between modalities. Similarly, Pham et al. [

8] drew inspiration from machine translation and introduced the Multimodal Cyclic Translation Network (MCTN), which learns shared semantic representations by cyclically translating between modalities. This architecture not only improves generalization but also allows for robust unimodal testing using only text inputs, achieving state-of-the-art results at the time.

In parallel, researchers have aimed to model the temporal and contextual dynamics of emotional cues. Wang et al. [

14] presented RAVEN, a Recurrent Attended Variation Embedding Network, which dynamically adjusts word embeddings based on nonverbal features like pitch and facial expression intensity. This innovation captures the nuanced interplay between speech and prosody, enabling the network to better interpret subtle emotional shifts. However, a shared limitation of these methods is their dependency on strict temporal alignment at the word level, which can be impractical in real-world applications due to noise and asynchronous sampling rates across modalities.

With the growing popularity of attention mechanisms, attention-based fusion models have come to dominate the MSA landscape. These approaches are capable of identifying the most relevant segments across modalities, regardless of their relative alignment. For example, Zadeh et al. [

20] developed a delta-memory attention network that captures both crossmodal and temporal relationships through a dynamic memory system embedded in a System of LSTMs. Likewise, Ghosal et al. [

3] proposed a Multi-modal Multi-utterance Bi-modal Attention (MMMU-BA) model, which applies modality-specific attention weights to extract high-impact features across utterances.

In our proposed DIFERNet framework, we build on this attention-based tradition. A crossmodal collaboration attention mechanism is integrated into the fusion initialization phase, encouraging rich contextual alignment between text and audio. Furthermore, we employ a crossmodal adjustment transformer module—motivated by the work of Tsai et al. [

11]—to adaptively reshape fused representations using unimodal guidance. This allows our model to maintain the integrity of modality-specific signals while enhancing joint semantic interpretation, especially under conditions of sequence misalignment or sparse interaction.

2.2. Transformer Architectures in Multimodal Contexts

The transformer architecture, initially introduced by Vaswani et al. [

13], revolutionized natural language processing by replacing recurrence with multi-head self-attention mechanisms. By facilitating parallel computation and enhancing long-range dependency modeling, transformers have since become foundational to a broad spectrum of tasks. The encoder-decoder design introduced in the original paper laid the groundwork for subsequent advancements in large-scale language modeling and representation learning.

Building on this foundation, transformer-based models like GPT [

9] and BERT [

25] further advanced the field by pretraining on massive text corpora and capturing bidirectional contextual cues. These models achieved remarkable success across tasks such as question answering, sentence classification, and machine translation. However, their applicability remained largely confined to unimodal textual data, leaving open the question of how to extend their strengths to the multimodal domain.

Recent efforts have begun bridging this gap. One notable contribution is the Multimodal Transformer (MulT) introduced by Tsai et al. [

11], which leverages crossmodal attention blocks to directly attend to low-level representations from different modalities. By forgoing intermediate fusion steps, MulT enables deeper crossmodal interaction and surpasses previous models in predictive accuracy. However, despite its success, MulT primarily emphasizes intermodal attention and does not explicitly address the need to retain unimodal specificity. This often leads to overly homogenized representations where modality-unique information may be diluted or lost entirely.

Motivated by these insights, our DIFERNet framework adopts a more balanced approach. While we incorporate transformer-based attention mechanisms to strengthen modality interaction, we also introduce a novel crossmodal adjustment transformer. This component is specifically designed to preserve the distinct attributes of each modality while enabling their cooperative integration. Through recurrent updates and conditional modulation, DIFERNet achieves a dynamic equilibrium between intermodal fusion and unimodal preservation, which is crucial in cases of asynchronous input or modality-specific noise.

In conclusion, while the transformer architecture has been successfully adapted to multimodal learning, our work contributes a more nuanced perspective. By combining crossmodal collaboration with modality-specific refinement, DIFERNet represents a meaningful step toward emotionally intelligent AI systems that can process unaligned and heterogeneous input streams without sacrificing robustness or interpretability.

3. Proposed Methodology

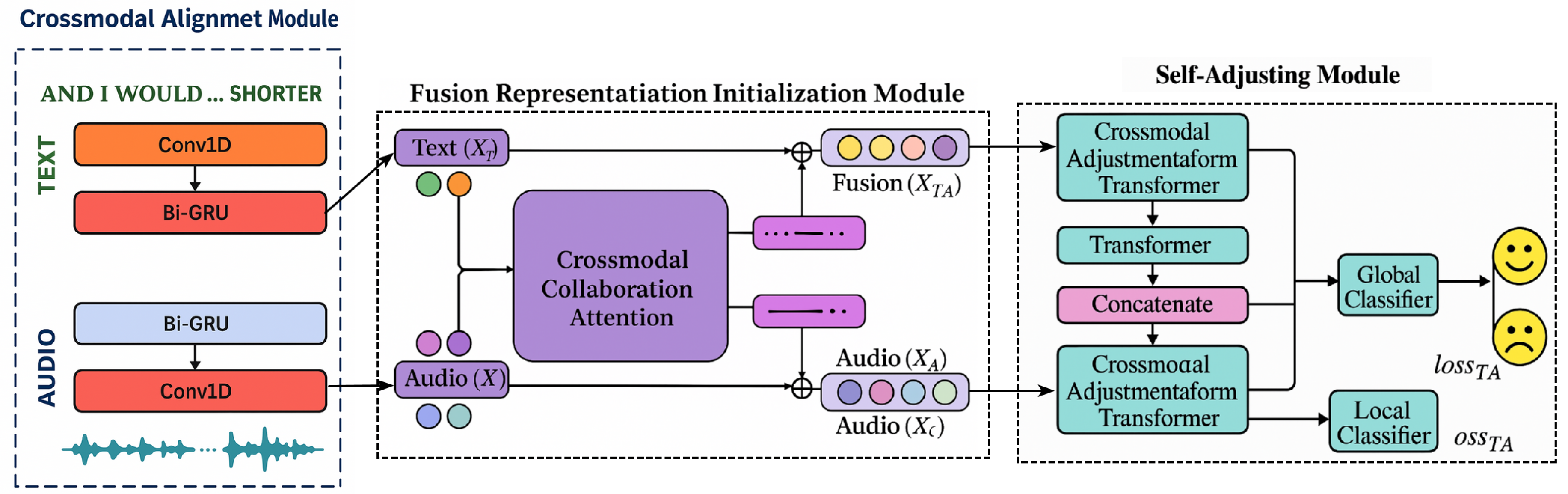

This section introduces the architectural components and technical design of our proposed Dynamic Interaction-Focused Emotion Representation Network (DIFERNet). As shown in

Figure 1, DIFERNet is designed to effectively fuse heterogeneous modalities, particularly unaligned text and audio streams, by dynamically modeling intermodal dependencies while preserving unimodal specificity. The entire framework is composed of three primary modules: (1) a crossmodal alignment module that standardizes the temporal and spatial dimensions of input features; (2) a fusion representation initialization module, which performs early-stage integration via attention-based interaction; and (3) a self-adjusting module that adaptively refines fusion representations using residual unimodal guidance.

We begin with a formal problem definition in

Section 3.1, followed by detailed explanations of each module in

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4. Each module is rigorously defined with its corresponding computational principles and equations to ensure reproducibility.

3.1. Problem Formulation

Let and denote the raw feature representations extracted from the text and audio modalities, where , are their respective sequence lengths and , are the feature dimensions. Given that and are inherently unaligned—due to asynchrony in modality sampling or semantic boundaries—the goal is to obtain rich joint representations that leverage both intra- and inter-modal dynamics.

To this end, we define a transformation function , where represents the sentiment prediction space (e.g., categorical sentiment classes or continuous emotion scores). DIFERNet aims to learn intermediate aligned representations , and their attentive counterparts , to construct fusion vectors and , which are subsequently adapted via interaction-aware refinement modules.

3.2. Crossmodal Alignment Module

The first step in DIFERNet is to harmonize the representational spaces of

and

, allowing effective interaction across modalities with differing feature formats. Following [

11], we apply 1D temporal convolutions with distinct kernel widths and strides to normalize the feature sequence lengths and dimensions. Formally:

where

and

denote kernel sizes and stride parameters, respectively. The output features are then fed into Bi-directional Gated Recurrent Units (Bi-GRU) to capture contextual dependencies:

The resulting (with l and d now unified) serve as aligned modality-specific embeddings for further crossmodal interaction.

3.3. Fusion Representation Initialization Module

To capture semantic correlations and modality interactions, we introduce a crossmodal collaboration attention mechanism. The attention operates bi-directionally, such that each modality queries the other for relevant features. Let the interaction matrices be:

We normalize these matrices using a soft-tanh combination:

Attention-based projections are then computed:

By element-wise interaction:

where ⊙ denotes Hadamard product. Fusion representations are constructed as:

with

being learnable weights and

denoting modality-specific biases.

3.4. Self-Adjusting Fusion Refinement Module

To preserve unimodal identity and adaptively refine fusion representations, we introduce a dual-path crossmodal adjustment mechanism. This is the core differentiator of DIFERNet, allowing and to be contextually rebalanced using unimodal cues.

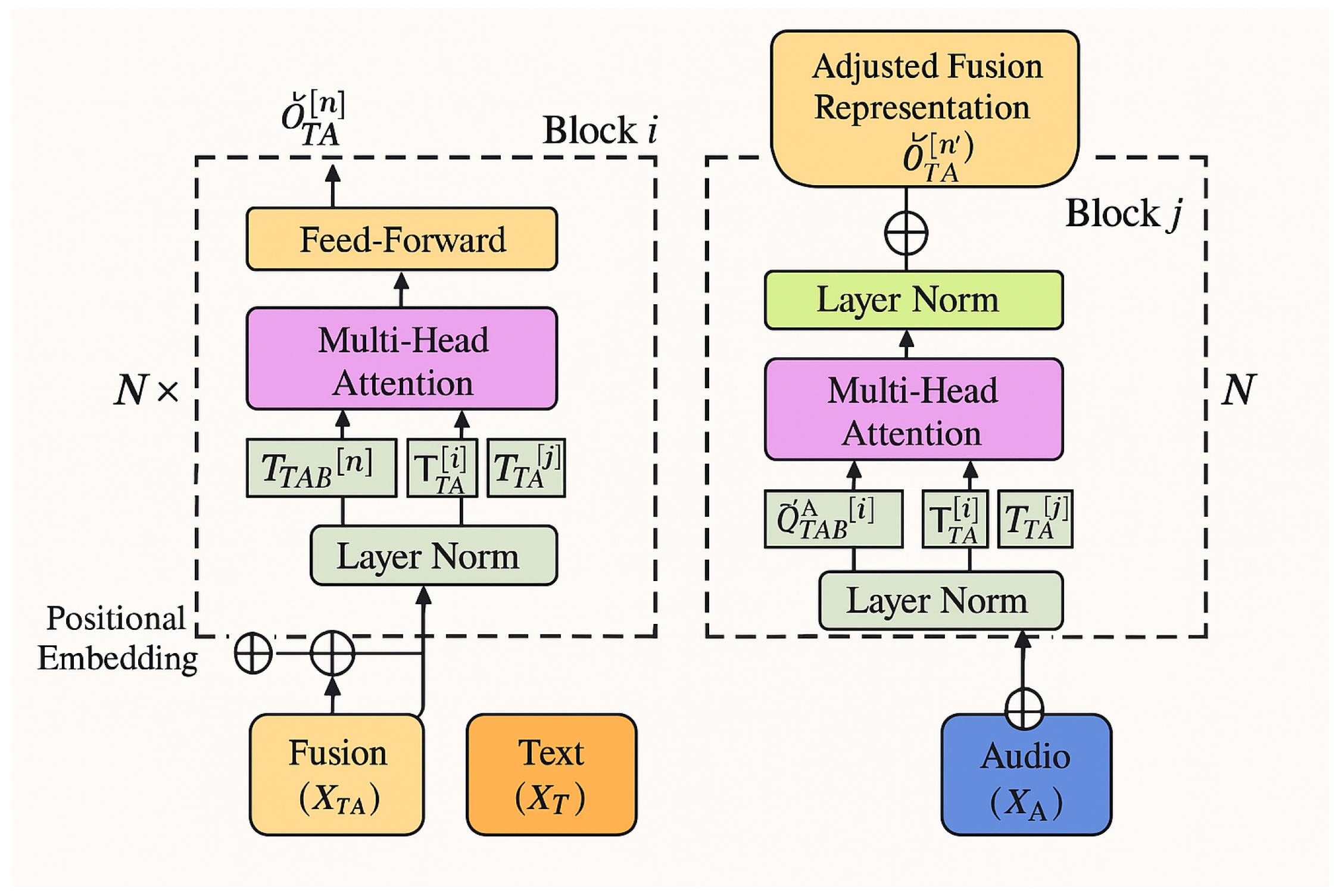

3.4.1. Crossmodal Adjustment Transformer

Each adjustment transformer receives the fusion input and one modality-specific guide.

Figure 2 shows the architecture. Prior to attention, we augment positional encoding

as in [

13]:

The inputs are enhanced as:

Let

,

, and

be the normalized inputs for fusion and unimodal streams. We define

N residual transformer layers where attention is defined as:

In each block, the fusion is updated with unimodal information:

where

denotes a position-wise feed-forward network. This process is repeated with both

and

for bi-guided refinement.

3.4.2. Global Fusion via Self-Attention

After refinement, both

and

are passed through self-attention transformers to extract temporal structure:

The final representation is formed by concatenation and classified globally:

where

denotes the global classifier.

In parallel, local classifiers

and

are applied:

3.4.3. Unified Loss Function

The complete loss function integrates predictions from global and local paths:

where

are tunable scalars, and each term is typically cross-entropy loss for classification:

with

being the true label and

the predicted probability for class

c.

This comprehensive architecture ensures that DIFERNet effectively captures both intermodal synergy and intramodal semantics, leading to enhanced performance in multimodal sentiment understanding.

4. Experiment

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed model, DIFERNet (Dynamic Interaction-Focused Emotion Representation Network), using two widely adopted multimodal sentiment analysis benchmarks: CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI. The evaluation framework encompasses multiple dimensions, including experimental configurations, feature extraction protocols, comparison with competitive baselines, and both quantitative and qualitative analyses. Our objective is to rigorously assess DIFERNet’s effectiveness in learning discriminative fusion representations from unaligned text and audio modalities.

4.1. Datasets and Configuration

We conduct experiments on two large-scale multimodal benchmarks: CMU-MOSI [

22] and CMU-MOSEI [

23].

CMU-MOSI contains 2199 opinion-labeled utterances across 93 video segments of online movie reviews. Each utterance is annotated on a continuous sentiment intensity scale ranging from (strongly negative) to (strongly positive). The audio stream is sampled at 12.5 Hz. The dataset is split into 52 training videos (1284 utterances), 10 validation videos (229 utterances), and 31 test videos (686 utterances), with no speaker overlap to avoid identity bias.

CMU-MOSEI comprises 23,454 labeled video clips from over 1000 speakers, providing a rich set of sentiment and emotion annotations. It is also annotated on a

scale and sampled at 20 Hz for audio. Following standard practice [

11], we adopt the official split and ensure the same evaluation settings as prior works to ensure comparability.

Model Configuration: For DIFERNet, we use 1D temporal convolution layers with 50 output channels, followed by Bi-GRU layers with 50 hidden units. Fully connected layers have 200 neurons with a dropout rate of 0.3. We use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and train using mini-batches of size 12 for 20 epochs. Loss functions are computed using a combined and cross-entropy formulation to accommodate both classification and regression subtasks.

4.2. Modality-Specific Feature Engineering

To ensure consistency with previous studies [

10,

11], we adopt standardized preprocessing techniques for extracting unimodal features.

4.2.1. Textual Embedding

We convert transcriptions into sequences of 300-dimensional vectors using GloVe embeddings pretrained on the 840B Common Crawl corpus. These embeddings provide rich semantic features and maintain high performance across a variety of NLP tasks.

4.2.2. Acoustic Features

We extract low-level acoustic descriptors using the COVAREP toolkit [

2]. Each utterance is represented as a 74-dimensional feature vector that includes MFCCs, fundamental frequency measures, glottal source parameters, peak slope, and maxima dispersion. The features are sampled at 100 Hz to capture fine-grained prosodic variations.

4.3. Metrics and Evaluation

To evaluate both classification and regression performance, we use five widely accepted metrics:

- : Accuracy for 7-class sentiment classification. - : Binary classification accuracy (positive vs. negative). - : F1-score for binary sentiment analysis. - : Mean Absolute Error for sentiment intensity prediction. - : Pearson correlation between predicted and ground-truth sentiment scores.

Higher scores are preferable for , , , and , whereas lower is better for . To ensure statistical stability, we average results over five independent runs using different random seeds.

4.4. Benchmarking Against Strong Baselines

We benchmark DIFERNet against several competitive multimodal models:

EF-LSTM: Early-fusion model concatenating inputs before feeding them into a shared LSTM.

LF-LSTM: Late-fusion model processes each modality independently and merges outputs via concatenation.

MCTN [

8]: Learns joint embeddings via cyclic modality translation.

RAVEN [

14]: Dynamically modulates word embeddings using nonverbal cues.

MulT [

11]: Transformer-based model with directional crossmodal attention.

DIFERNet: Our proposed model that combines crossmodal collaborative attention with unimodal-preserving refinement.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Quantitative Analysis

In this section, we present a comprehensive quantitative evaluation of our proposed architecture, DIFERNet, and benchmark its performance against a series of competitive baselines. The evaluation covers two datasets—CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI—and includes both classification and regression metrics. Additionally, we investigate the influence of the number of crossmodal blocks within DIFERNet to understand how architectural depth affects its discriminative power.

5.1.1. Performance Comparison with Baseline Models

Table 1 reports the experimental results on the CMU-MOSI dataset. Despite relying solely on two modalities—text and audio—our model significantly surpasses most existing methods that incorporate all three modalities (text, audio, and video). This observation highlights the effectiveness of DIFERNet’s dynamic adjustment mechanisms and its ability to extract rich sentiment information from asynchronous input streams.

In the binary sentiment classification task, our model achieves an score of and an score of , representing an absolute improvement of – over traditional recurrent-based models such as EF-LSTM and LF-LSTM, and a noticeable margin over advanced architectures like RAVEN and MCTN. Even compared to the transformer-based MulT model, which uses three modalities, DIFERNet delivers comparable or superior performance, which is especially remarkable given its lighter input modality setting.

For sentiment score classification (), DIFERNet achieves , exceeding the performance of most baseline systems by a margin of –. While the original MulT using three modalities reports a slightly higher score (), a fair comparison must consider the setting where only text and audio are used. Under this condition, DIFERNet outperforms MulT on all metrics, including an improvement of on , on binary accuracy (), and on .

In the regression setting, DIFERNet achieves a Mean Absolute Error () of and a Pearson correlation coefficient () of , indicating its capability to capture fine-grained sentiment intensity. Compared to MulT with text and audio, DIFERNet reduces error by approximately and boosts correlation by . These improvements suggest that the self-adjusting module effectively retains modality-specific nuances during the fusion process.

Table 2 shows the results on the CMU-MOSEI dataset, further demonstrating the generalizability of our approach. In binary classification, DIFERNet achieves

and

, outperforming most prior methods by

–

and also improving upon MulT (text+audio only) by

and

, respectively. The 7-class accuracy reaches

, a relative improvement of

over MulT and a significant gain over earlier methods like RAVEN and MCTN.

In the regression task, DIFERNet attains a of and a of . These results exceed all comparative baselines, including the full-modality version of MulT. The performance gap between our model and models using video suggests that effective dynamic modeling between unaligned text and audio modalities can compensate for the absence of visual features when done correctly.

Overall, DIFERNet consistently outperforms baseline systems on both datasets, validating the efficacy of its architecture. The results clearly demonstrate that (1) deep crossmodal attention enhances inter-modal synergy, and (2) preserving unimodal pathways during late-stage adjustment mitigates feature suppression and semantic dilution—a common issue in multimodal fusion.

5.1.2. Influence of Crossmodal Block Depth

To explore the sensitivity of DIFERNet to the number of crossmodal blocks, we conduct an ablation study on the CMU-MOSI dataset by varying the total number of transformer layers within the crossmodal adjustment module. As illustrated in

Table 2, we experiment with values of

, where each configuration assigns

blocks for text-to-fusion adjustment and

for audio-to-fusion refinement.

The results reveal a clear trend: performance (measured by ) improves steadily as the number of blocks increases from 2 to 10. This indicates that a deeper attention structure facilitates more expressive alignment between the modalities, enabling the network to learn complex temporal and semantic dependencies. The best performance is achieved when , suggesting a sweet spot between representation richness and overfitting risk.

Interestingly, further increasing the number of blocks beyond 10 leads to a marginal drop in accuracy. This decline is likely due to over-parameterization and gradient instability in deep attention stacks, especially when training data is relatively limited. These findings suggest that while deeper attention enables richer fusion, a controlled architecture depth is necessary to maintain generalization.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a novel architecture named DIFERNet (Dynamic Interaction-Focused Emotion Representation Network) that targets the challenge of modeling sentiment from unaligned multimodal sequences, specifically focusing on the interplay between text and audio signals. Unlike conventional multimodal fusion methods that either rely heavily on modality alignment or inadequately preserve modality-specific information, DIFERNet is uniquely designed to dynamically regulate inter-modal interactions while simultaneously maintaining the distinct expressive characteristics of each modality.

At the heart of our model lies the crossmodal adjustment transformer, which enables DIFERNet to adaptively refine its fusion representations based on unimodal semantic cues. By integrating both local modality-aware updates and a global interaction modeling mechanism, DIFERNet ensures that neither modality is suppressed during fusion and that the joint representations remain expressive, context-sensitive, and temporally coherent.

Extensive experiments on two benchmark datasets, CMU-MOSI and CMU-MOSEI, confirm the superior performance of our method across both classification and regression metrics. Even though DIFERNet utilizes only two modalities (text and audio), it consistently outperforms or matches state-of-the-art models that rely on all three modalities, including video. This highlights the strength of our dynamic fusion strategy and its ability to compensate for the lack of visual input by leveraging deeper semantic alignment and residual unimodal correction. Furthermore, qualitative analysis illustrates that DIFERNet can make sentiment predictions more aligned with human perception, particularly in cases where unimodal cues may be ambiguous or contradictory.

In addition to its quantitative advantages, the architecture of DIFERNet offers practical benefits: it is modular, interpretable, and computationally efficient. Each component—from the attention-based initialization to the adaptive refinement module—contributes to a more robust understanding of sentiment in realistic, noisy, and asynchronous multimodal scenarios.

Looking forward, we recognize that the rapid progress of large-scale pre-trained models offers new opportunities to enhance multimodal sentiment analysis. As part of our future work, we plan to investigate how powerful pretrained language models such as BERT, RoBERTa, or GPT can be extended beyond their unimodal origins to support dynamic crossmodal understanding. One promising direction involves initializing the textual backbone of DIFERNet with pre-trained language representations and then coupling it with crossmodal adaptation layers capable of fine-tuning jointly across modalities.

Moreover, another future extension could involve the integration of emotional commonsense knowledge and affective reasoning into the fusion pipeline. By allowing DIFERNet to reason about emotional causes and consequences, the model may achieve better generalization on more complex affective understanding tasks such as sarcasm detection, emotion cause identification, and context-sensitive sentiment analysis.

In summary, DIFERNet presents a principled and effective approach for modeling sentiment in the presence of unaligned multimodal input. It opens up promising avenues for future research that bridges pretraining, dynamic fusion, and symbolic emotion modeling in the realm of human-centric AI.

References

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; and Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Degottex, G.; Kane, J.; Drugman, T.; Raitio, T.; and Scherer, S. 2014. COVAREP—A collaborative voice analysis repository for speech technologies. In 2014 ieee international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (icassp), 960–964. IEEE.BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–4186.

- Ghosal, D.; Akhtar, M. S.; Chauhan, D.; Poria, S.; Ekbal, A.; and Bhattacharyya, P. Contextual inter-modal attention for multi-modal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018; pp. 3454–3466. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; and Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Wu, Z.; Jia, J.; Bu, Y.; Zhao, S.; and Meng, H. Towards Discriminative Representation Learning for Speech Emotion Recognition. IJCAI 2019, 5060–5066. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P. P.; Liu, Z.; Zadeh, A. B.; and Morency, L.-P. 2018. Multimodal Language Analysis with Recurrent Multistage Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 150–161.

- Liu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lakshminarasimhan, V. B.; Liang, P. P.; Zadeh, A. B.; and Morency, L.-P. 2018. Efficient Low-rank Multimodal Fusion With Modality-Specific Factors. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2247–2256.

- Pham, H.; Liang, P. P.; Manzini, T.; Morency, L.-P.; and Póczos, B. 2019. Found in translation: Learning robust joint representations by cyclic translations between modalities. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 33, 6892–6899.

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; and Sutskever, I. 2018. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. URL https://s3-us-west-2. amazonaws. com/openai-assets/researchcovers/languageunsupervised/language understanding paper. pdf.

- Rahman, W.; Hasan, M. K.; Lee, S.; Zadeh, A. B.; Mao, C.; Morency, L.-P.; and Hoque, E. 2020. Integrating Multimodal Information in Large Pretrained Transformers. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2359–2369.

- Tsai, Y.-H. H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P. P.; Kolter, J. Z.; Morency, L.-P.; and Salakhutdinov, R. 2019. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In Proceedings of the conference. Association for Computational Linguistics. Meeting, volume 2019, 6558. NIH Public Access.

- Turk, M. Multimodal interaction: A review. Pattern Recognition Letters 2014, 36, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A. N. ; Kaiser,.; and Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems; 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, P. P.; Zadeh, A.; and Morency, L.-P. Words can shift: Dynamically adjusting word representations using nonverbal behaviors. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 7216–7223. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Kleinegesse, S.; Comanescu, R.; and Radu, O. Recognizing emotions in video using multimodal DNN feature fusion. Proceedings of Grand Challenge and Workshop on Human Multimodal Language (Challenge-HML); 2018; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Mao, W.; and Chen, G. Multi-interactive memory network for aspect based multimodal sentiment analysis. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Xu, H.; and Gao, K. Cm-bert: Cross-modal bert for text-audio sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on multimedia; 2020; pp. 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Xu, H.; Meng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, J.; Zou, J.; and Yang, K. Ch-sims: A chinese multimodal sentiment analysis dataset with fine-grained annotation of modality. In Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics; 2020; pp. 3718–3727. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; and Morency, L.-P. Tensor Fusion Network for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2017; pp. 1103–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P. P.; Mazumder, N.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; and Morency, L.-P. Memory Fusion Network for Multi-view Sequential Learning. Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P. P.; Poria, S.; Vij, P.; Cambria, E.; and Morency, L.-P. 2018b. Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension. In Proceedings of the... AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 2018, 5642. NIH Public Access.

- Zadeh, A.; Zellers, R.; Pincus, E.; and Morency, L.-P. 2016. Multimodal sentiment intensity analysis in videos: Facial gestures and verbal messages. IEEE Intelligent Systems 2016, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A. B.; Liang, P. P.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; and Morency, L.-P. Multimodal language analysis in the wild: Cmu-mosei dataset and interpretable dynamic fusion graph. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018; pp. 2236–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; He, X.; and Deng, L. 2020. Multimodal intelligence: Representation learning, information fusion, and applications. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Endri Kacupaj, Kuldeep Singh, Maria Maleshkova, and Jens Lehmann. 2022. An Answer Verbalization Dataset for Conversational Question Answerings over Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.06734.

- Magdalena Kaiser, Rishiraj Saha Roy, and Gerhard Weikum. 2021. Reinforcement Learning from Reformulations In Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 459–469.

- Yunshi Lan, Gaole He, Jinhao Jiang, Jing Jiang, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2021. A Survey on Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering: Methods, Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 4483–4491. Survey Track.

- Yunshi Lan and Jing Jiang. 2021. Modeling transitions of focal entities for conversational knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers).

- Mike Lewis, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7871–7880.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2019. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Pierre Marion, Paweł Krzysztof Nowak, and Francesco Piccinno. 2021. Structured Context and High-Coverage Grammar for Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2021.

- Pradeep, K.; Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems 2010, 16, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1410.1090.

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2013; 1–6ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. [CrossRef]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556.

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024.

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions. TPAMI 2007, 39, 664–676.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2020; pp. 2151–2161.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022; pp. 11513–11521.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2022; pp. 4232–4241.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; pp. 7692–7699.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2022; pp. 9871–9881.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100, 101919.

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.09541.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2305.11719.

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.18357.

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.05179.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022; 2022; pp. 15460–15475.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics 2011, 37, 9–27.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023; pp. 2593–2608.

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.05250.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021a.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021b.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.11255.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi:10.18653/v1/N19-1423. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR 2023, abs/2309.05519.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024b.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024c.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022b.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023b.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024d.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning 2021, 11, 1–10.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.05127.

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022c.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2411.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management 2020, 57, 102311.

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2018, 22, 1–22.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023d.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2023, 41, 50:1–50:32.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023e.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 5544–5556.

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1502.03044.

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2012, 23, 1177–1193.

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).