1. Introduction

Today’s world is grappling with numerous environmental issues, with water pollution being a significant concern. One of the contributors to water pollution is food dye colorants, which are utmost toxic and may pose cancer risks due to their aromatic ring structures. [

1,

2,

3].Despite the harmful effects of food dyes, we cannot avoid using them. As a result, extensive endeavors have been undertaken to eliminate food dyes from effluents through conventional methods, which tend to be expensive in terms of both implementation and maintenance. [

4,

5]. Classic treatment approaches, such as adsorption and oxidation, do not fully eradicate dyes from contaminated water. Consequently, it is crucial to implement and refine more efficient processes to achieve complete removal of various toxic and colorful pollutants.Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), including photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, photocatalysis, ozonation, sonolysis, electrochemical methods, and ionizing radiation, have shown significant effectiveness in degrading a wide range of pollutants during wastewater treatment.[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].Each of these methods focuses on producing strong oxidizing agents, particularly hydroxyl radical species which can oxidize organic compounds, causing them to degrade into water and carbon dioxide. Moreover, gamma radiolysis is a convenient, eco-friendly, clean and low-cost technique when compared to previously described methods [

19].

1.1. Rationale of the Investigation

This study aims to investigate the gamma radiation-induced degradation of erythrosine in aqueous solutions. Erythrosine is classified as a fluorone dye and is commonly found in various sweets, including candies and popsicles, as well as in cake-decorating gels. It is also used to color pistachio shells and is found in printing inks, biological stains, and dental plaque disclosing agents. Repeated or prolonged occupational exposure may lead to cumulative health effects that impact organs or biochemical systems. Some individuals may experience sensitization reactions upon skin contact with this dye. Long-term exposure to high concentrations of dust can cause changes in lung function, such as pneumoconiosis, due to particles smaller than 0.5 microns that penetrate and remain in the lungs. The primary symptom of this condition is breathlessness.

Erythrosine dye has been authorized as a food additive in the EU since 1973 and is still approved for food and pharmaceuticals. [

20,

21,

22,

23].While erythrosine is widely used as a water-soluble dye, its environmental impact is becoming a greater concern, as its degradation can produce aromatic amines that may be directly or indirectly associated with numerous diseases. Thus, it is standard practice to treat effluent containing such dyes before discharge. Recent research has reported methods for their removal, including electrochemical, photo-degradation, and bio-degradation techniques. [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].The research pertaining to gamma radiation induced degradation of erythrosine is not documented much.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials:

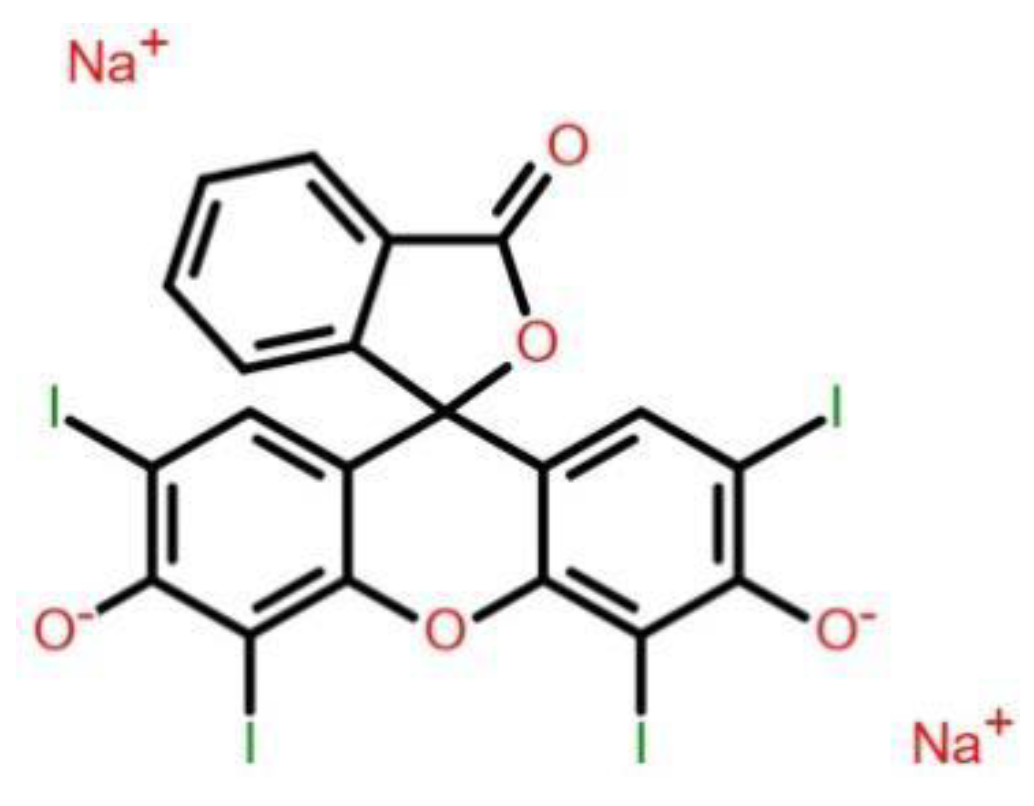

Erythrosine or Acid Red 51 is a synthetic xanthenes dye and oregano-iodine compound commonly used in food products. Its chemical structure features a conjugated π system, contributing to its strong red color due to significant light absorption. However, it is crucial to note that erythrosine is toxicand have possibility to exceed the standard daily intake (ADI) 0.1 mg/kg body weight/day. This highlights the importance of monitoring its usage in food to ensure safety and compliance with regulatory guidelines. [

22,

23].

Figure 1 shows the structure of Erythrosine dye. Its molecular formula is C

20H

6I

4Na

2O

5 and molecular weight is 879.84 g mol−1. The test samples of aqueous solution of erythrosine dye were obtained by appropriate dilutions from the stock solution which was prepared afresh before every study. All the studies were carried out at natural pH of the aqueous solutions. The desired

2.2. Irradiation of Samples:

The test solutions of desired strength were obtained by diluting stock solution. The predetermined volume (25ml) of test solutions was exposed to gamma radiations using Co-60 as a source available at the Department of Chemistry, Nagpur University, India (

Figure 2). The gamma irradiator's dosage rate was determined using Fricke dosimetry and the samples were irradiated at ambient temperature to different gamma doses.

2.3. Analytical Methods

The pH of the test samples was determined using an Elico make pH meter, while the Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was assessed following standard methodologies, providing a measure of organic matter in the samples. For the analysis of dye solutions, a double beam UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Spectronic D-20) was employed to quantify dye concentration before and after treatment. Double distilled water was used as the blank for calibration, ensuring precise spectrophotometric measurements.

3. Results

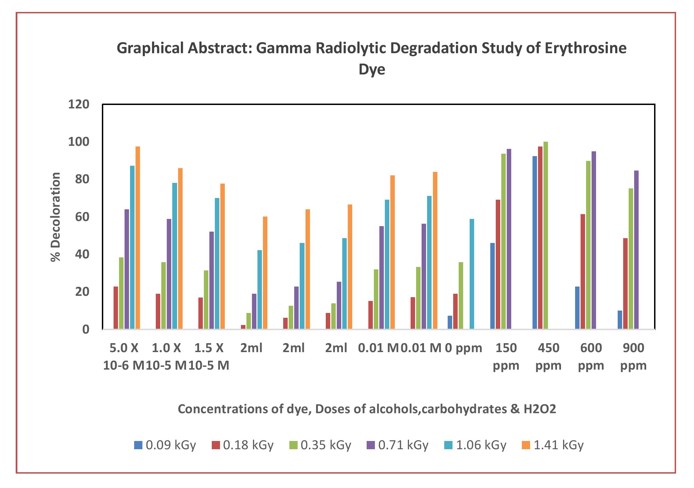

3.1. Decoloration Study:

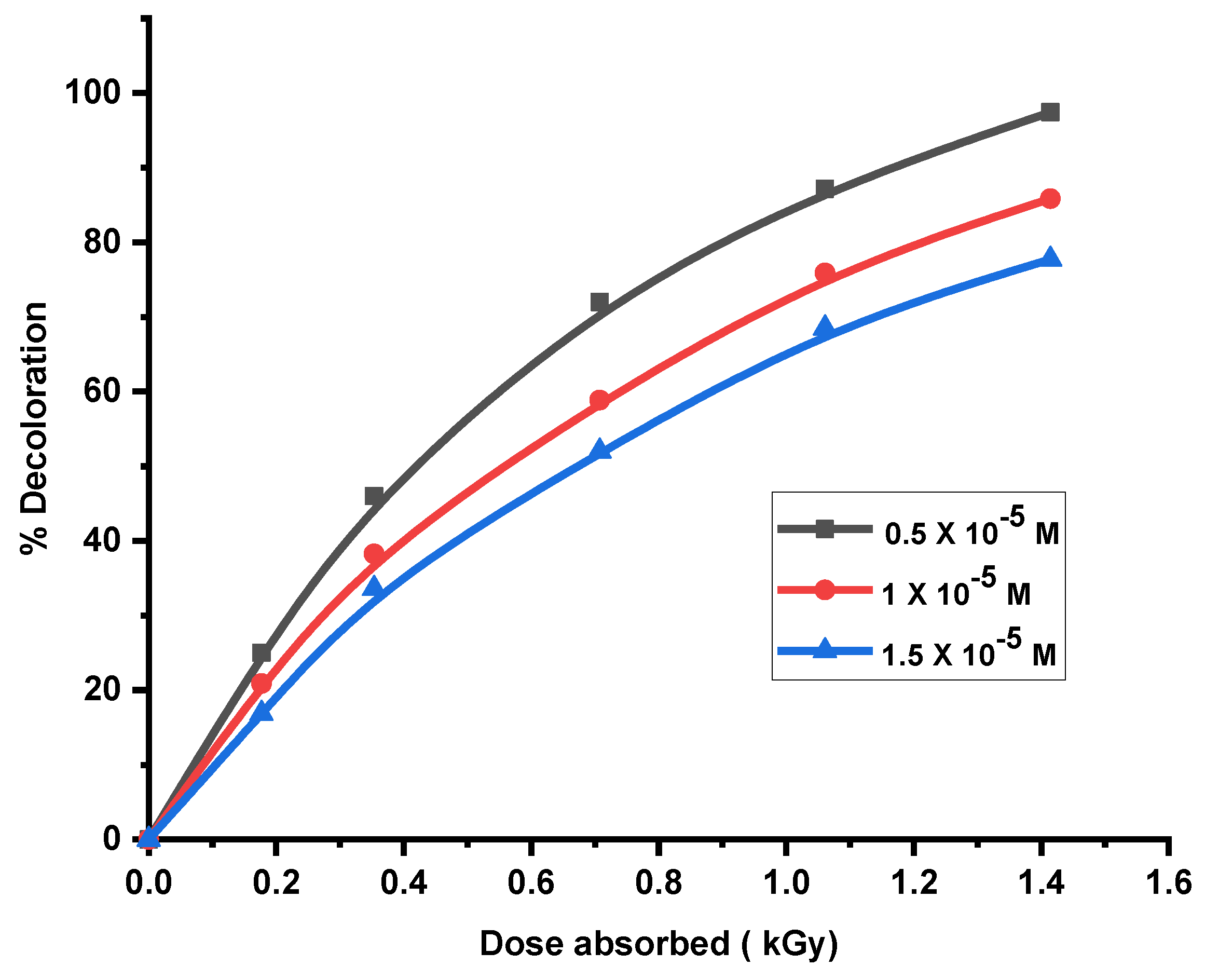

It was found that the extent and rate of decoloration increases with increase in the dose of gamma radiation. For a particular dye concentration decoloration increases with increase in absorbed gamma dose. The rate of decoration was high initially, but with increasing dose of gamma radiations, the rate of decoloration increased gradually and beyond a particular dose, it remained almost unaltered. It was seen that as the concentration of dye increases, dose of gamma radiations required to achieve the same extent of decolorizationalso increases.

The dose of gamma radiation required for complete decolorization directly depends on the strength of the dye solution. The significant decolorization achieved through gamma radiation may be outcome of the products of water radiolysis formed, such as hydroxyl and hydrogen ions, which attack the chromophoric groups of the dye molecules. Additionally, the energetic gamma radiation can directly destroy dye molecules. However, since the radicals produced were not isolated, the decomposition of the dyes was cumulative, making it challenging to attribute the color bleaching achieved to a specific radical or to determine the extent of its contribution.

3.2. Changes in Process Parameters

It was observed that, there were changes in some process parameters such as COD, pH and conductance of dye solutions upon irradiation.

3.2.1. Change in pH

The change in pH of test samples was observed upon irradiation. While the pH consistently decreased with increasing doses of γ-radiation, though the rate of decrease was not uniform. Initially, the pH of the sample solutions dropped gradually along with the extent of decoloration, but this change in pH began to slow down later. Previous studies have shown that organic acids of low molecular weight such as formic, oxalic, acetic, malonic, malefic, fumaric and succinic acids are produced during the gamma irradiation of dyes. Therefore, the significant decreases in solution pH are likely attributed to these organic and inorganic acids formed as degradation products of dye. Literature validate these findings, explaining that the observed results stem from reactions between the original dye molecules and various species generated from water radiolysis, such as hydrogen radicals, dihydrogen water, oxygen, hydrated electrons, and hydroxyl radicals according to the Equation (1) [

7,

19].

3.2.2. Change in Conductivity

The conductivity of the dye solution was found to increase progressively during the entire course of irradiation. For the smaller gamma absorbed doses the conductivity slightly increases however, as the degree of decolorization increased with dose, the conductance increased significantly.

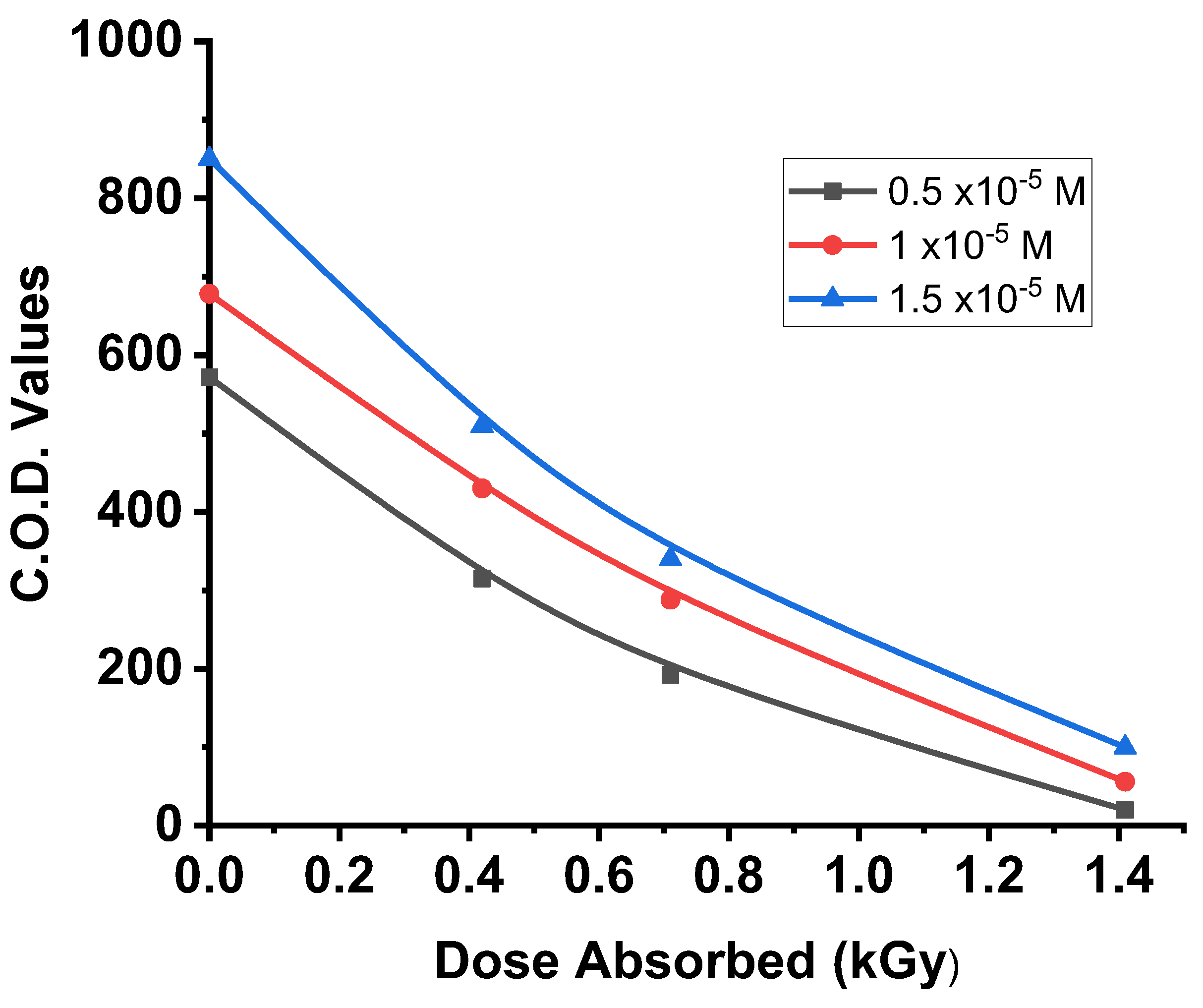

3.3. Effect of Radiolysis on COD

The Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) is a key metric for assessing water pollution, indicating the oxygen required to fully oxidize organic matter in a water sample. In your study, you investigated the impact of gamma irradiation on erythrosine by measuring COD values at various absorbed doses over time.

The results presented in

Figure 3, exhibit a clear relationship between the irradiation dose and the degradation of organic matter, with COD values decreasing exponentially over time. The degradation process consists of two distinct phases: an initial rapid phase (up to 0.5 kGy) followed by a slower phase (beyond 0.5 kGy). By 1.42 kGy, the COD elimination reached to 90%.

The rapid degradation in the first phase can be attributed to the fragmentation of the erythrosine molecule, resulting in aromatic intermediates as the dose absorbed increases. Conversely, the slower decrease in COD during the second phase may be linked to the formation of aliphatic carboxylic acids, which occur as a result of oxidative degradation of the aromatic rings.

These findings highlight the efficiency of gamma radiation in degrading organic pollutants and the complex mechanisms involved in the breakdown process. [

7,

19,

35,

41]

Previous studies have indicated that during advanced oxidation processes, hydroxyl radicals initially attack the chromophoric structure of dyes, followed by a series of subsequent reactions [

9,

28,

36]. Notably, research on xanthene dyes, which share similarities with erythrosine, provides a basis for hypothesizing the degradation tract of erythrosine.

It can be proposed that the degradation of Erythrosine begins with the breakdown of the target molecule, yielding two primary intermediate products: 2-(2-formylphenyl)-2-carboxylate and 2- (2- (3, 6- dihydro- 2H- pyran- 4- yl- phenyl)- 2- carboxylate [

33]. The so formed intermediates on subsequent hydroxylation, yields hydroxylated aromatic compounds. Ultimately, oxidative cleavage of the benzene ring occurs and to forms carboxylic acids. This process culminates in the mineralization of the organic matter into CO

2 and water H

2O.

This proposed pathway underscores the complexity of erythrosine degradation and the potential for complete mineralization through advanced oxidation processes.

3.4. The Effect of Additives on Radiolysis of Erythrosine

In this study, it was observed that certain substances can protect dye solutions by slowing down the decoloration process. Specifically, alcohols such as ethyl alcohol (primary), isopropyl alcohol (secondary), and tertiary butyl alcohol (tertiary), along with carbohydrates like dextrose (a monosaccharide) and sucrose (a disaccharide), were added in various amounts to dye solutions with selected concentrations. Simultaneously, the inclusion of oxidizing agents like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and Fenton's Reagent was found to enhance the degradation efficiency of the dye, thereby accelerating the decoloration process. This improvement is attributed to the generation of a higher quantity of highly reactive hydroxyl (.OH) radicals, which promote the breakdown of dye molecules. The study also investigated the effects of different amounts of H2O2 on the dye solutions, as well as the impact of varying concentrations of H2O2 and Fe2+ ions when using Fenton’s Reagent to further assess decoloration efficiency.

Addition of second solute to a solution can lead to competition with the first solute for radiolytic products such as hydroxyl radicals (.OH), hydrogen atoms (H•), and solvated electrons (e-aq). The effectiveness of the second solute in scavenging these radicals determines the extent of protection for the first solute, a phenomenon referred to as the "protection effect." The scavenging efficiency of a given radical depends on both the concentration of the scavenger and the rate constant for its reaction with the specific free radical. Scavengers interact with free radicals, effectively "intercepting" them and safeguarding other solutes in the solution. Certain compounds, including alcohols, carbohydrates, urea, and thiourea, have been shown to provide protective effects against dye degradation, likely due to their ability to scavenge e-aq, H•, and .OH radicals generated as primary products during the radiolysis of aqueous systems.

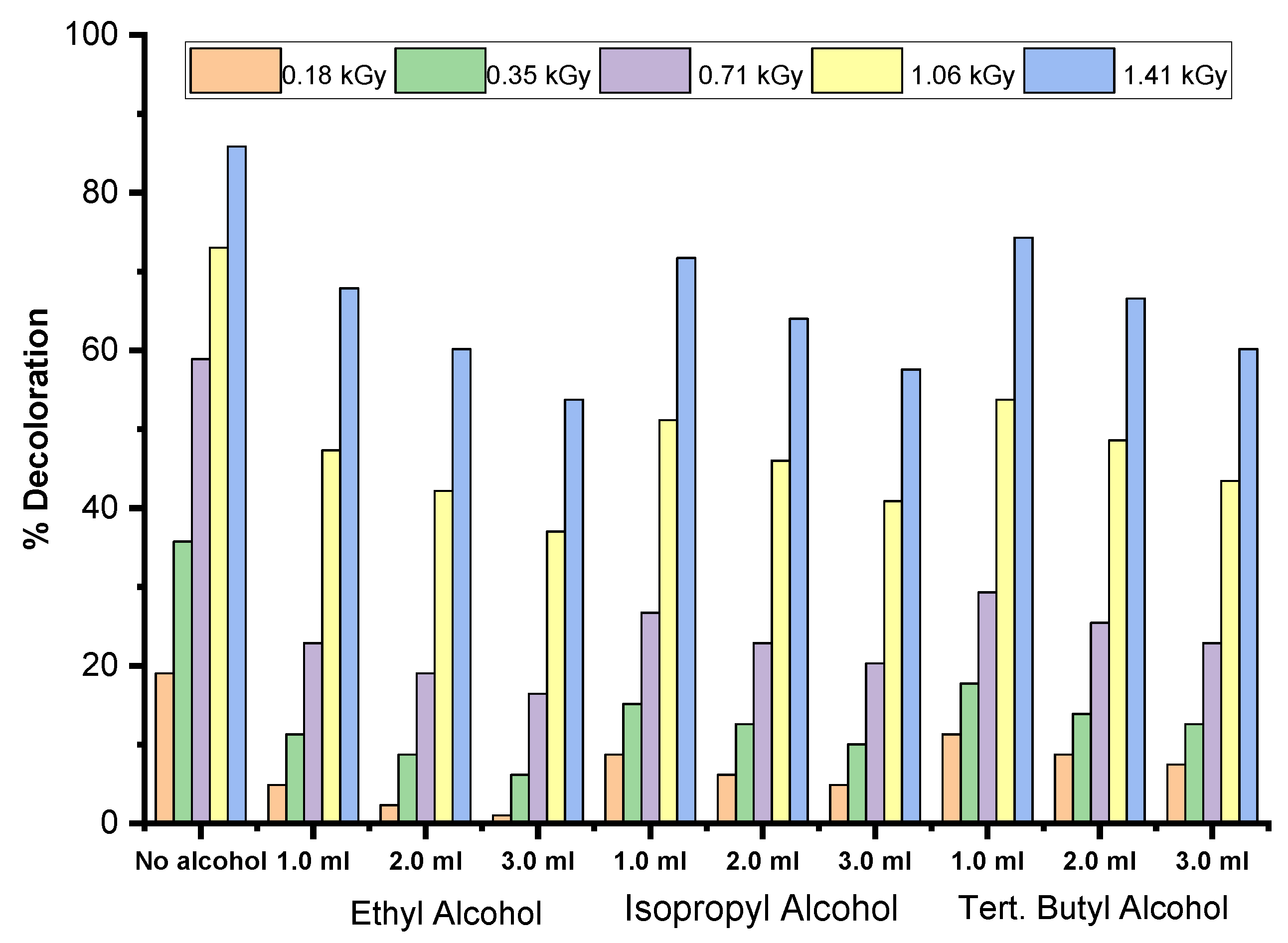

3.4.1. Effect of Alcohols

The addition of alcohols reduces dye decoloration by lowering the concentration of effective radicals responsible for dye degradation through an indirect mechanism. Alcohols obstruct decoloration by interacting with the radicals generated in the system. Once a certain concentration of alcohol is reached and subsequently depleted, the degradation of the dye can accelerate due to the availability of radicals.

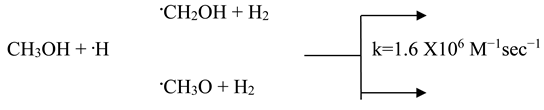

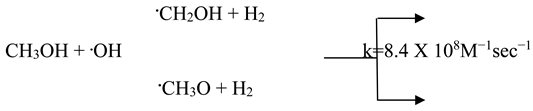

Methanol and most alcohols react with •OH and •H, primarily by detaching hydrogen atom from either oxygen or carbon atoms within their structure. This reaction further diminishes the pool of radicals available for degrading the dye molecules as shown in equations (2) and (3).

It is observed that lower molecular weight alcohols and lower dye concentrations enhance scavenging activity. This can be attributed to the ability of alcohols to interact with •OH and •H radicals yielded from water radiolysis, reducing the likelihood of these radicals interacting with dye molecules. In contrast, the hydrated electron (e-aq) reacts very slowly with alcohols under normal conditions. Additionally, all alcohols react similarly with the radicals, providing a protective effect for the dye molecules.

The data indicates that adding alcohols to dye solutions slows both the rate and extent of dye degradation, which is attributed to their radical scavenging ability.

The efficiency of alcohols in scavenging radicals and protecting the dye from degradation follows this order: Ethanol > 2-Propanol > Tertiary Butyl Alcohol. This suggests that ethanol is the most effective at inhibiting degradation, while tertiary butyl alcohol is the least effective among the three.

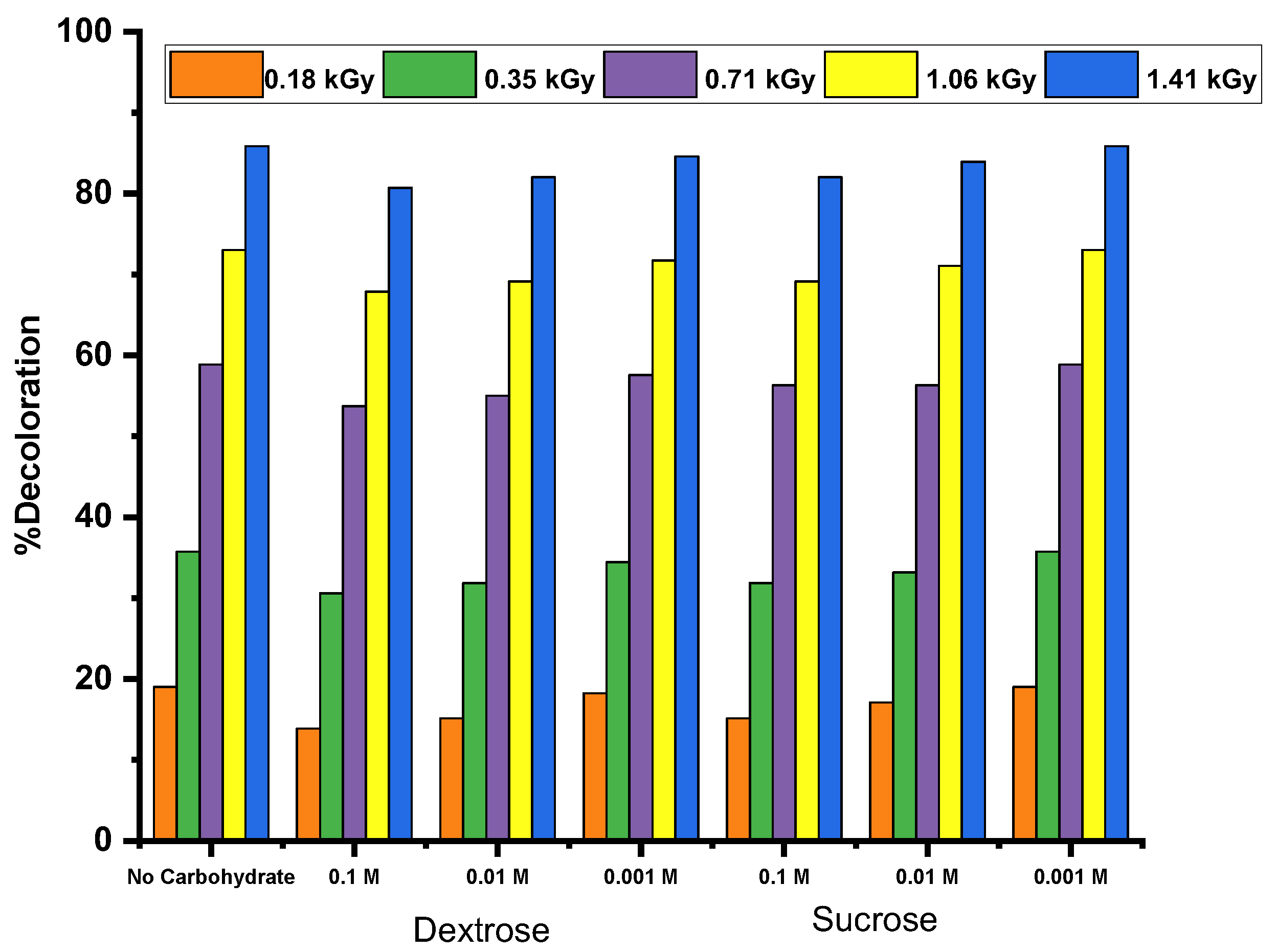

3.4.2. The Effect of Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates also have been reported to protect the synthetic dyes against the degradation during radiolysis due to scavenging ability like alcohols.

The reaction rates indicate that •OH radicals (k = 4 × 10^7 M⁻

1s⁻

1) and hydrogen atoms (k = 1.9 × 10^9 M⁻

1s⁻

1) react readily with carbohydrates, while solvated electrons (e-aq) react more slowly (k ≈ 3 × 10^5 M⁻

1s⁻

1). The radicals H• and •OH both primarily abstract hydrogen atoms from the α-carbon of carbohydrates. The slower reaction rate with e

-aq can be attributed to the fact that sugars are mostly in their cyclic hemiacetal form, rather than existing as aldehydes or ethers, which would be more reactive. In solution containing dissolved oxygen, e

-aq will form O

2-, the hydrogen atom also will be scavenged by oxygen as per equations(4) and(5).

The highly active

.OH radicals in case of monosaccharide, can abstract any of the carbon-bound hydrogen almost at random. It has been widely reported that acidic products are formed from glucose irradiated with

60Co [

37,

38].The scissor of glycosidic bond is dominant effect of irradiation on disaccharides. The disaccharides can indeed undergo oxidation, oxidative destruction, and form deoxy- and deoxy-keto compounds, just like their monosaccharide constituents, depending on the conditions and the specific functional groups in the molecule. The dissociation of glycosidic bond due to gamma irradiations a main characteristic of all disaccharides.

The effect of adding dextrose and sucrose on the gamma radiolysis of dyes is shown in

Figure 5. It reveals that, as the concentration of carbohydrates (dextrose or sucrose) increases, the rate of degradation decreases for all dyes, indicating a protective effect of carbohydrates. Notably, dextrose provides a better protective effect than sucrose, regardless of their concentrations.

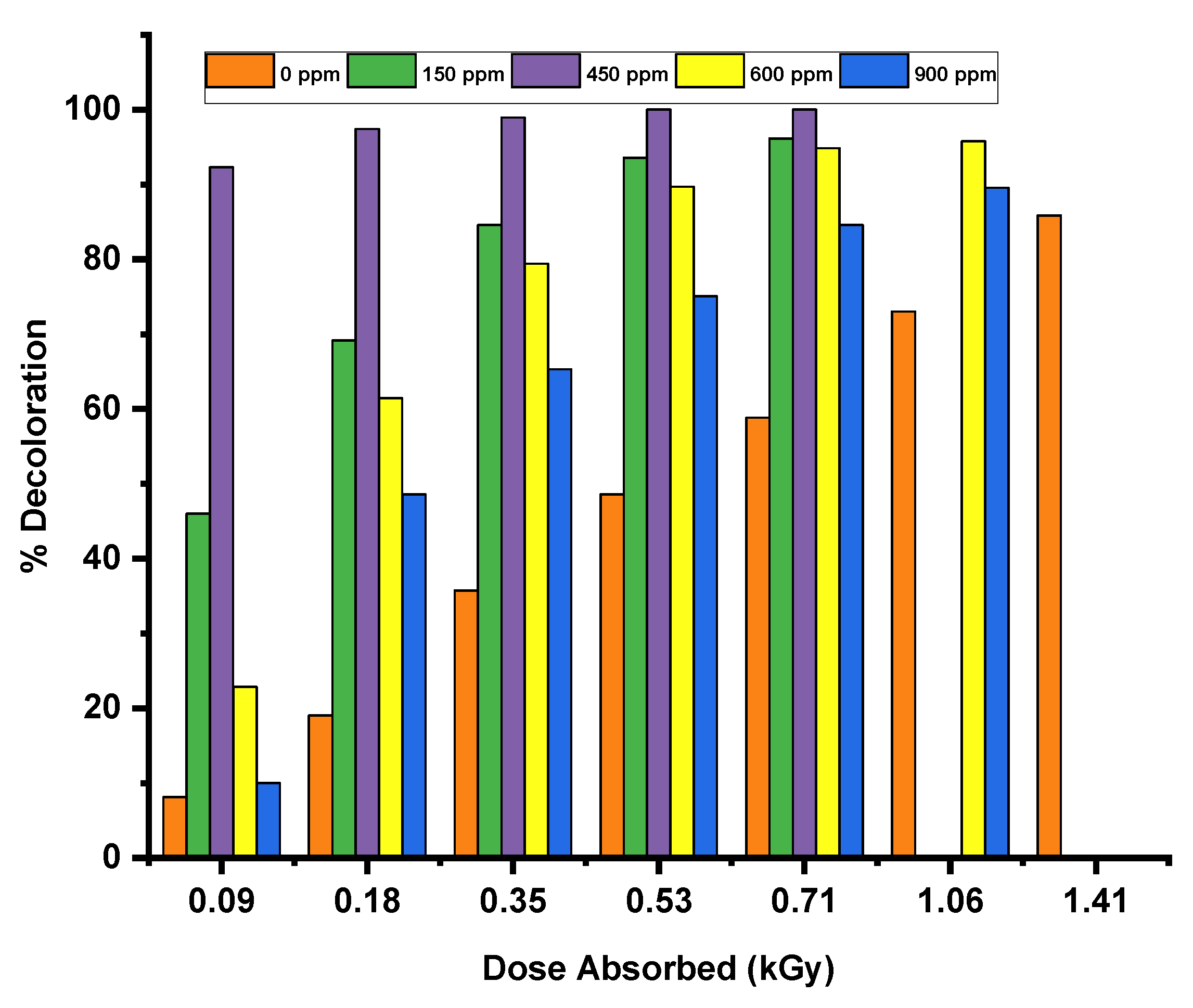

3.4.3. Effect of H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide, due to its chemical versatility, offers distinct advantages in oxidative processes compared to other oxidizing agents like sodium hypochlorite and ozone, which require more careful handling during application. The figure above illustrates the variation in the degree of decolorization as a function of H2O2 dosage for Erythrosine. The results indicate that the addition of hydrogen peroxide enhances the decolorization reaction.

This is because H

2O

2 interact quickly with hydrated electrons generated from water radiolysis, producing hydroxyl (

.OH) radicals as per equation (6) below.

Figure 7.

Effect of H2O2 addition on extent of decoloration.

Figure 7.

Effect of H2O2 addition on extent of decoloration.

The observed increase in decoloration with the addition of hydrogen peroxide is attributed to a higher concentration of •OH radicals produced during the reaction. This indicates that •OH radicals are more effective in degrading chromophores than hydrated electrons. Graphical data shows that decoloration increases as hydrogen peroxide concentration rises, reaching a peak at a specific concentration known as the "critical dose."However, the graphs indicate that when the H

2O

2 concentration exceeds the critical dose, efficacy of decoloration also decreases. This effect can be justified on the basis that some of the •OH radicals are scavenged by the excess hydrogen peroxide [

39,

40],generated as per (7),(8) and (9) equations, which reduces their availability for degradation of chromophore . This interaction limits the effectiveness of the decoloration process.

5. Conclusions

The colour removal of erythrosine food dye in aqueous solutions by ionizing gamma radiation was thoroughly investigated. The values of chemical oxygen demand (C.O.D) were found to be the function of applied gamma doses. Nearly 90 % reduction in C.O.D. values was obtained at the dose of 1.41kGy. The addition of alcohols and carbohydrates retarded the efficiency of degradation while hydrogen peroxide was favorable additive in terms of increased efficiency of degradation. The results obtained in present investigation, supports the use of high energy gamma irradiation treatment as an better option to supersede the conventionally used techniques. The employment of gamma radiation can be a potential and clean environment friendly treatment technique in the future, for treating the effluents coming from industries using the variety of synthetic dyes.

References

- Padhia, B. S. Pollution due to Synthetic Dyes: Toxicity and Carcinogenicity Studies and Remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 3, 940–955.

- Hassaan, A. M.; Nemr, E. L. Health and Environmental Impacts of Dyes: Mini Review. Am. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 64–67.

- Gezer, B. Adsorption Capacity for the Removal of Organic Dye Pollutants from Wastewater Using Carob Powder. Int. J. Agric. For. Life Sci. 2018, 2, 1–14.

- Gupta, V. K. Application of Low-Cost Absorbents for Dye Removal—A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2313–2342.

- Salleh, M. A. M.; Mahmoud, D. K.; Wan Abdul Karim, W. A.; Idris, A. Cationic and Anionic Dye Adsorption by Agricultural Solid Wastes: A Comprehensive Review. Desalination 2011, 280, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Audino, F.; Conte, L. O.; Schenone, A. V.; Pérez Moya, M.; Graells, M.; Alfano, O. M. A Kinetic Study for the Fenton and Photo-Fenton Paracetamol Degradation in an Annular Photoreactor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 25, 4312–4323.

- Zaouak, A.; Matoussi, F.; Dachraoui, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of Herbicide Bifenox Acid in Aqueous Medium Using Diamond Thin Film Electrode. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2013, 48, 878–884. [CrossRef]

- Rinku, B.; Rakshit, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Erythrosine by Using Manganese Doped TiO₂ Supported on Zeolite. Int. J. Chem. Sci. 2016, 14, 1768–1776.

- Alvarez-Martin, A.; Trashin, S.; Cuykx, M.; Covaci, A.; De Wael, K.; Janssens, K. Photodegradation Mechanisms and Kinetics of Eosin-Y in Oxic and Anoxic Conditions. Dyes Pigment. 2017, 145, 376–384. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Bhargava, M.; Sharma, N. Electrochemical Degradation of Erythrosine in Pharmaceuticals and Food Product Industries Effluent. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2005, 64, 191–197.

- Weng, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q. Electrochemical degradation of typical dyeing wastewater in aqueous solution: performance and mechanism. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 290–296. [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, K.V.; Subrahmanyam, M.; Boule, P. Photocatalytic transformation of dyes and by-products in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Technol. 2003, 24, 1025–1030. [CrossRef]

- Kamaljit, S.; Sucharita, A. Removal of synthetic textile dyes from wastewaters: a critical review on present treatment technologies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 807–878.

- Gultekin, I.; Nilsun, H.I. Degradation of reactive azo dyes by UV/H₂O₂: impact of radical scavengers. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 2004, 39, 1069–1081.

- Fartode , Anoop P etal. Synergistic effect of H2O2 addition on gamma radiolytic decoloration of some commercial dye solutions. IOPConf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021,1070, 1-8.

- Jhimili, P.; Naik, D.B.; Sabharwal, S. High energy induced decoloration and mineralization of Reactive Red 120 dye in aqueous solution: a steady state and pulse radiolysis study. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2010, 79, 770–776. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Mile, V.; Csay, T.; Takács, E.; Wojnárovits, L. Hydroxyl radical-induced degradation of fenuron in pulse and gamma radiolysis: kinetics and product analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 693–700. [CrossRef]

- Changotra, R.; Guin, J.P.; Dhir, A.; Varshney, L. Decomposition of antibiotic ornidazole by gamma radiation in aqueous solution: kinetics and its removal mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 32591–32602. [CrossRef]

- Zaouak, A.; Noomen, A.; Jelassi, H. Gamma-radiation induced decolorization and degradation on aqueous solutions of Indigo Carmine dye. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 317, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Apostol, L.C.; Smaranda, C.; Diaconu, M.; Gavrilescu, M. Preliminary ecotoxicological evaluation of erythrosin B and its photocatalytic degradation products. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2015, 14, 465–471. [CrossRef]

- Pathania, D.; Sharma, S.; Singh, P. Removal of methylene blue by adsorption onto activated carbon developed from Ficus carica bast. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S1445–S1451. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. F.; Utiger, R. D.; Schwartz, S. L.; Witorsch, P.; Meyers, B.; Braverman, L. E.; Witorsch, R. J. Effects of Oral Erythrosine (2′,4′,5′,7′-Tetraiodofluorescein) on Thyroid Function in Normal Men. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1987, 91, 299–304.

- Abdel Aziz, A. H.; Shouman, S. A.; Attia, A. S.; Saad, S. F. A Study on the Reproductive Toxicity of Erythrosine in Male Mice. Pharmacol. Res. 1997, 35, 457–462. [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, A. S.; Paras, T.; Rakshit, A.; Ameta, K. L. Photocatalytic Degradation of Erythrosine Using Nanoparticles of N, S-Codoped Titanium Dioxide. Sci. Rev. Chem. Commun. 2015, 5, 43–50.

- Jain, R.; Sikarwar, S. Semiconductor-Mediated Photocatalyzed Degradation of Erythrosine Dye from Wastewater Using TiO₂ Catalyst. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 1403–1410.

- De Jesus, G. J.; Corso, R. C.; De Campos, A.; Martins, M. S. F. Biodegradation of Erythrosin B Dye by Paramorphic Neurospora crassa 74A. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2010, 53, 473–480.

- Basfar, A. A.; Muneer, M.; Alsager, O. A. Degradation and Detoxification of 2-Chlorophenol Aqueous Solutions Using Ionizing Gamma Radiation. Nukleonika 2017, 62, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Sadique Rayhan, A. B. M.; Jahir Raihan, M.; Nargis, A.; Ismail, I. M. I.; Habib, A.; Mahmood, A. J. Kinetics of Degradation of Eosin Y by One of the Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs)–Fenton’s Process. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2016, 7, 863–887. [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, N.; Chair, K.; Bedoui, A. Efficient Degradation of Tannic Acid in Water by UV/H₂O₂ Process. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R. G.; Neto, S. A.; De Andrade, A. R. Electrochemical Degradation of Reactive Dyes at Different DSA® Compositions. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 126–131.

- Jain, R.; Bhargava, M.; Sharma, N. Electrochemical Degradation of Erythrosine in Pharmaceuticals and Food Product Industries Effluent. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2005, 64, 191–197.

- Ahmadi, M. F.; Bensalah, N.; Gadri, A. Electrochemical Degradation of Anthraquinone Dye Alizarin Red S by Anodic Oxidation on Boron-Doped Diamond. Dyes Pigment 2007, 73, 86–89.

- Vignesh, K.; Suganthi, A.; Rajarajan, M.; Sakthivadivel, R. Visible Light Assisted Photodecolorization of Eosin-Y in Aqueous Solution Using Hesperidin Modified TiO₂ Nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 4592–4600. [CrossRef]

- Carmen, L.; Gavrilescu, M. Erythrosine B in the Environment. Removal Processes. Food Environ. Saf. J. 2013, 3, 253–264.

- Zaouak, A.; Matoussi, F.; Dachraoui, M. Electrochemical Degradation of a Chlorophenoxy Propionic Acid Derivative Used as an Herbicide at Boron-Doped Diamond. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 1662–1668. [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M. A.; Ashraf, S. S. Radiation-Induced Degradation of Dyes—An Overview. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 6–16.

- Esterbaur, H.; Schubert, J.; Sanders, E. B.; Sweely, C. C. Nature 1977, 326, 315.

- Diehl, J. F.; Adam, S.; Delin Ce'e, H.; Jalcubick, V. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 15.

- Poulis, I.; Tsachpinis, I. Photodegradation of the Textile Dye Reactive Black 5 in Presence of Semiconducting Oxides. J. Chem. Tech. Biotech. 1999, 74, 349.

- Suzuki, N.; Nagai, H.; Hotta, H.; Washino, H. M. The Radiation-Induced Degradation of Azo Dyes in Aqueous Solution. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1975, 26, 726.

- Fartode, Anoop P., Fartode,S. A. and ShelkeTushar R. .Decoloration study of some synthetic dye solutions by photo Fenton advanced oxidation process.. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2024,01,2974.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).