Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

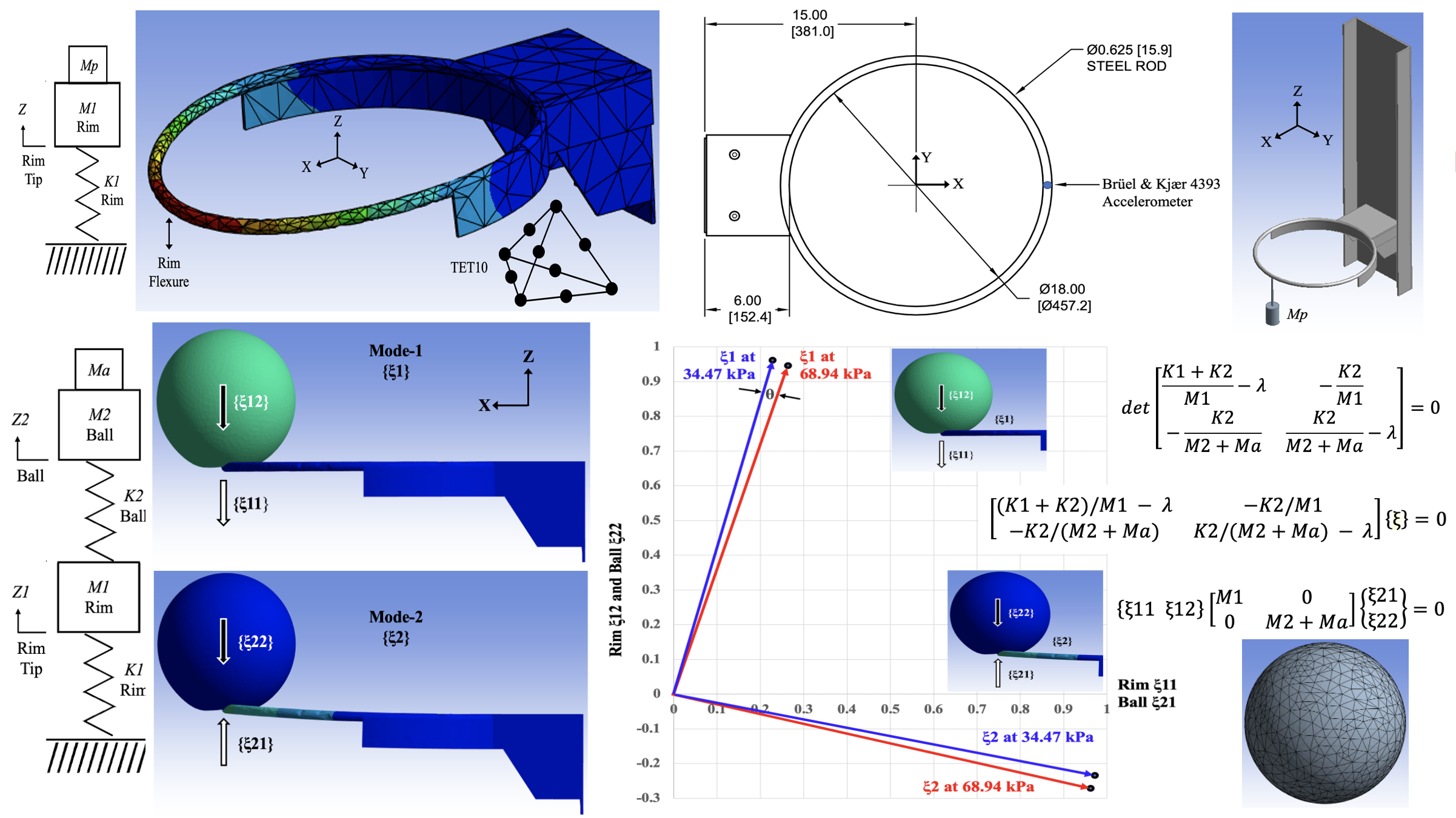

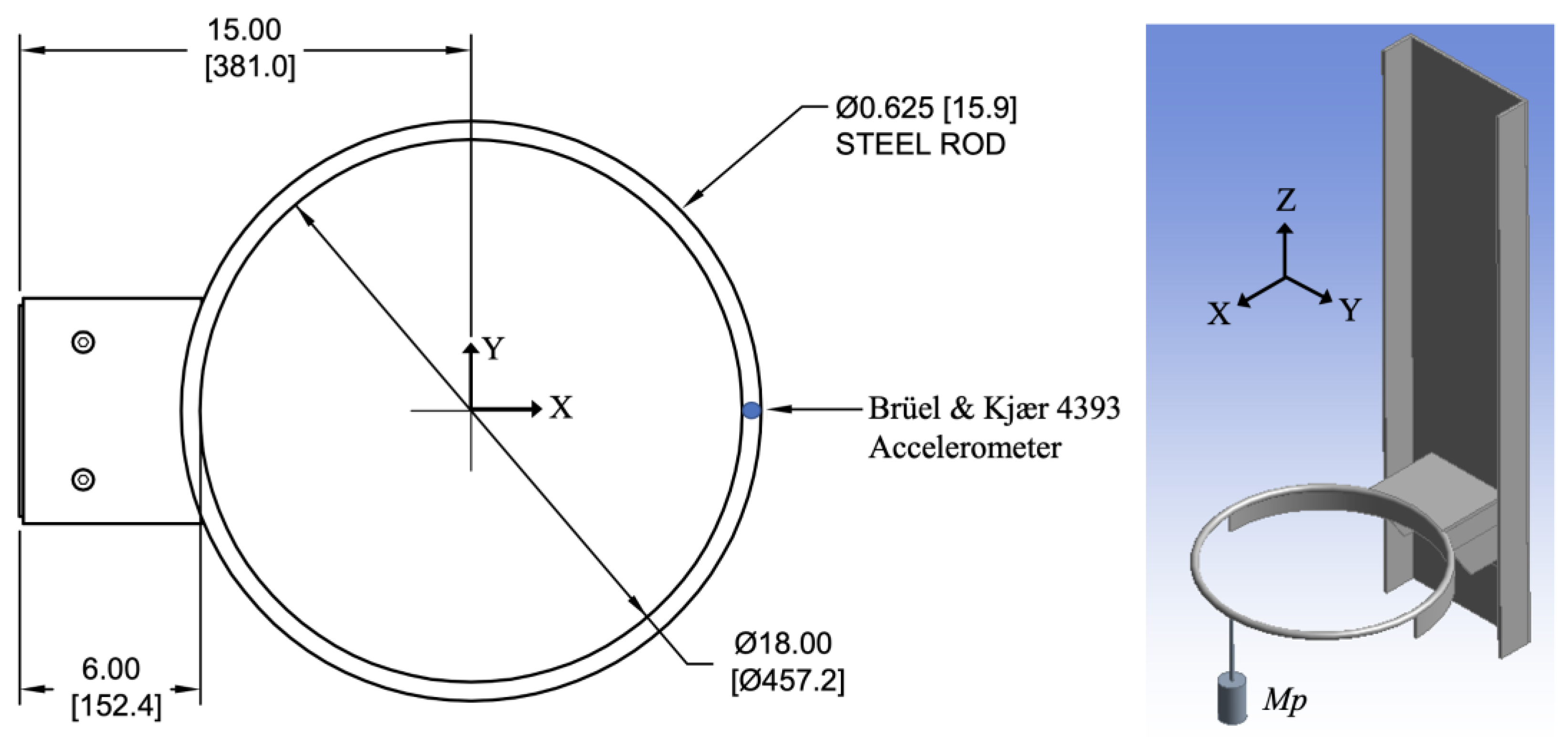

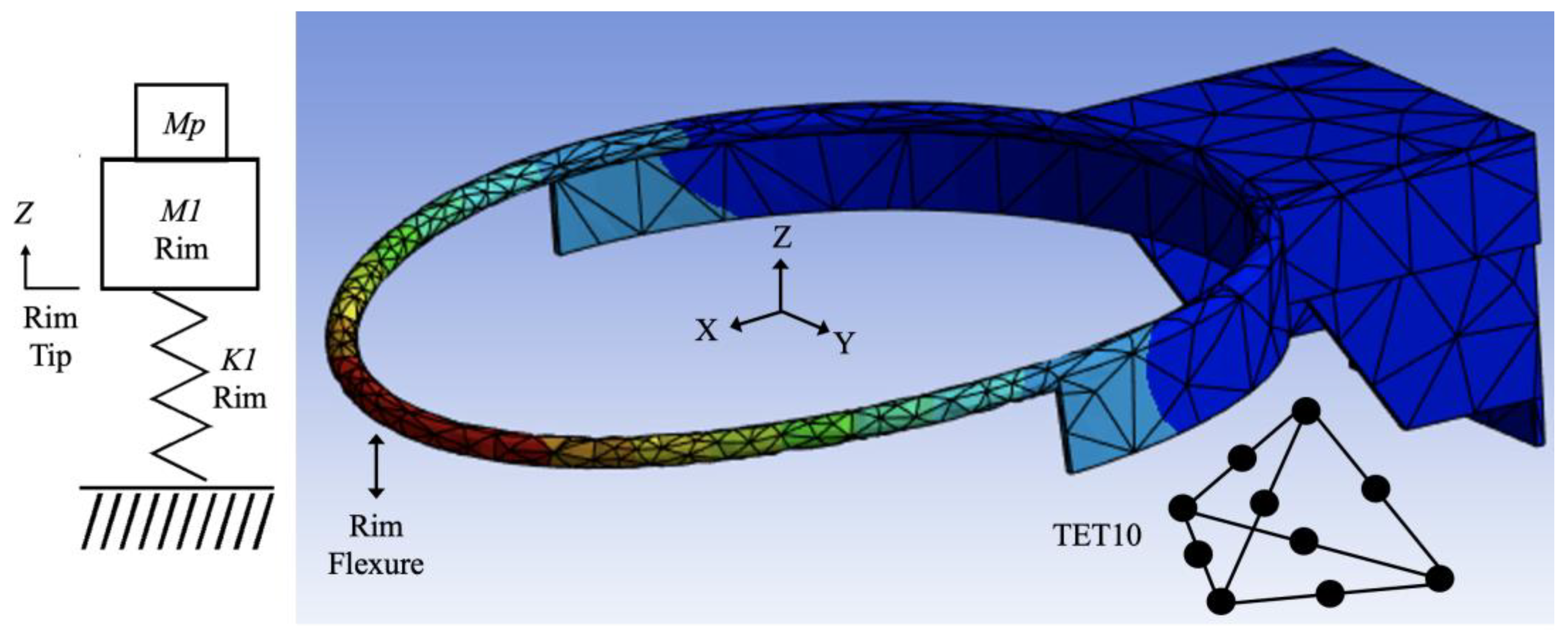

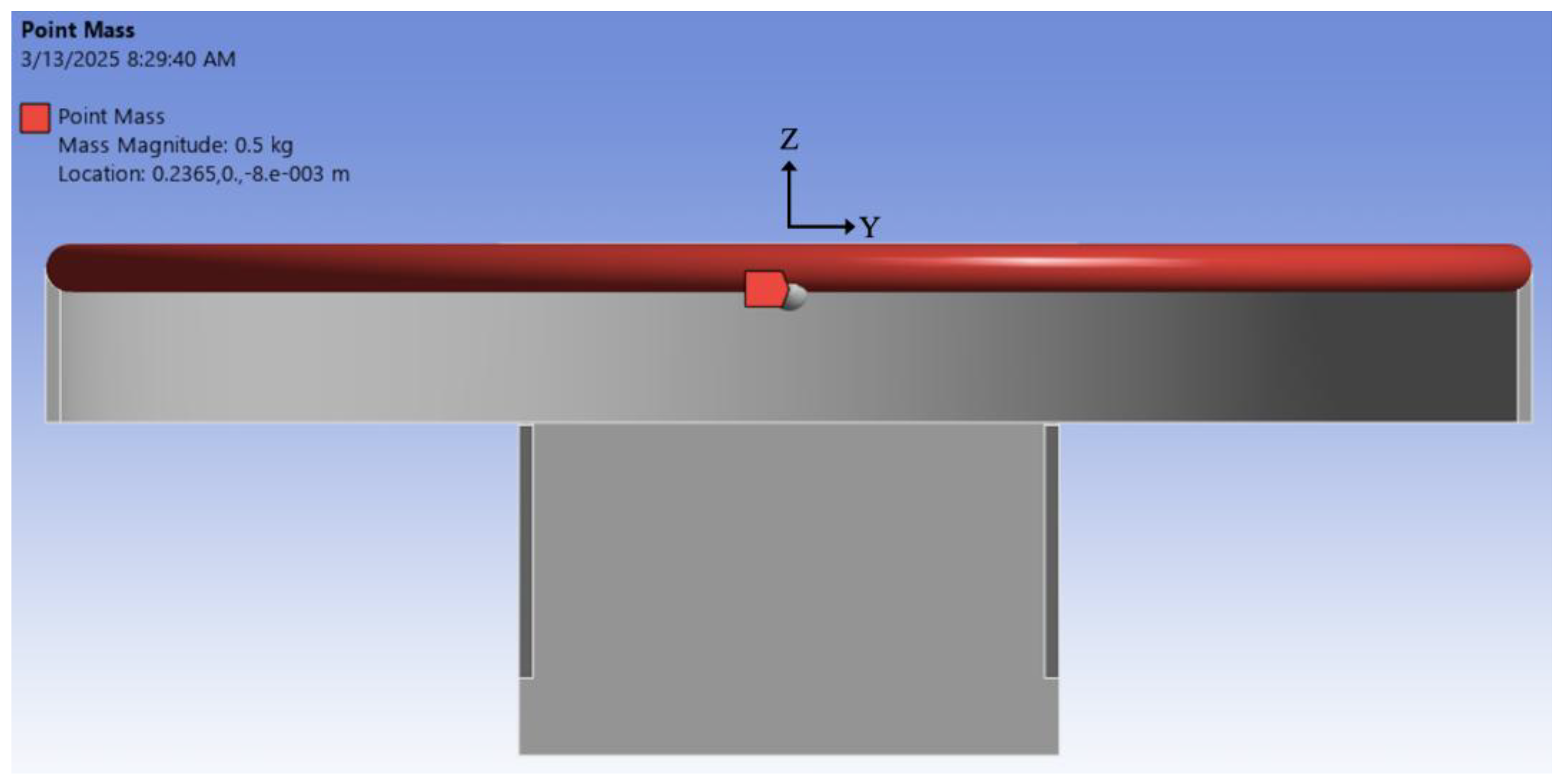

2. Modal Analysis of Gared Rim in Isolation

3. Gared Rim and A12N Basketball

4. Variation of Radial Spring Rate and Damping Ratio of A12N Basketball versus Pressure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

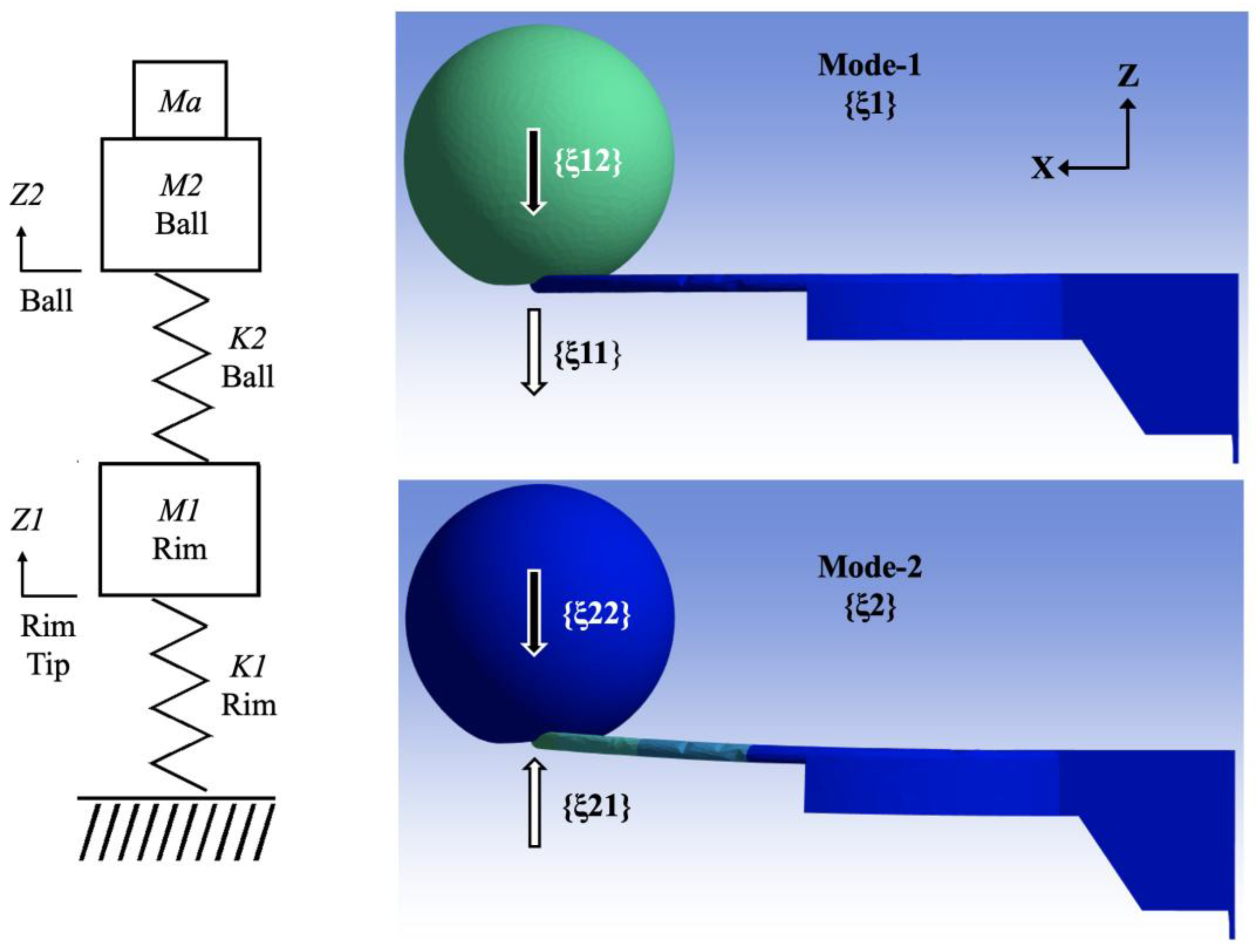

| [K] | Spring Matrix |

| K1 | Dynamic Spring Rate of the Gared Rim, N/m |

| K2 | Dynamic Radial Spring Rate of the A12N Basketball, N/m |

| [M] | Mass Matrix |

| M1 | Dynamic Mass of the Gared Rim, kg |

| M2 | Dynamic Mass of the A12N Basketball, kg |

| Ma | Added Mass to top of A12N Basketball, kg |

| Mp | Perturbation Mass added to Gared Rim, kg |

| P | Inflation Pressure of A12N Basketball, kPa |

| Eigenvalue, square of natural frequency, radians2/second2 | |

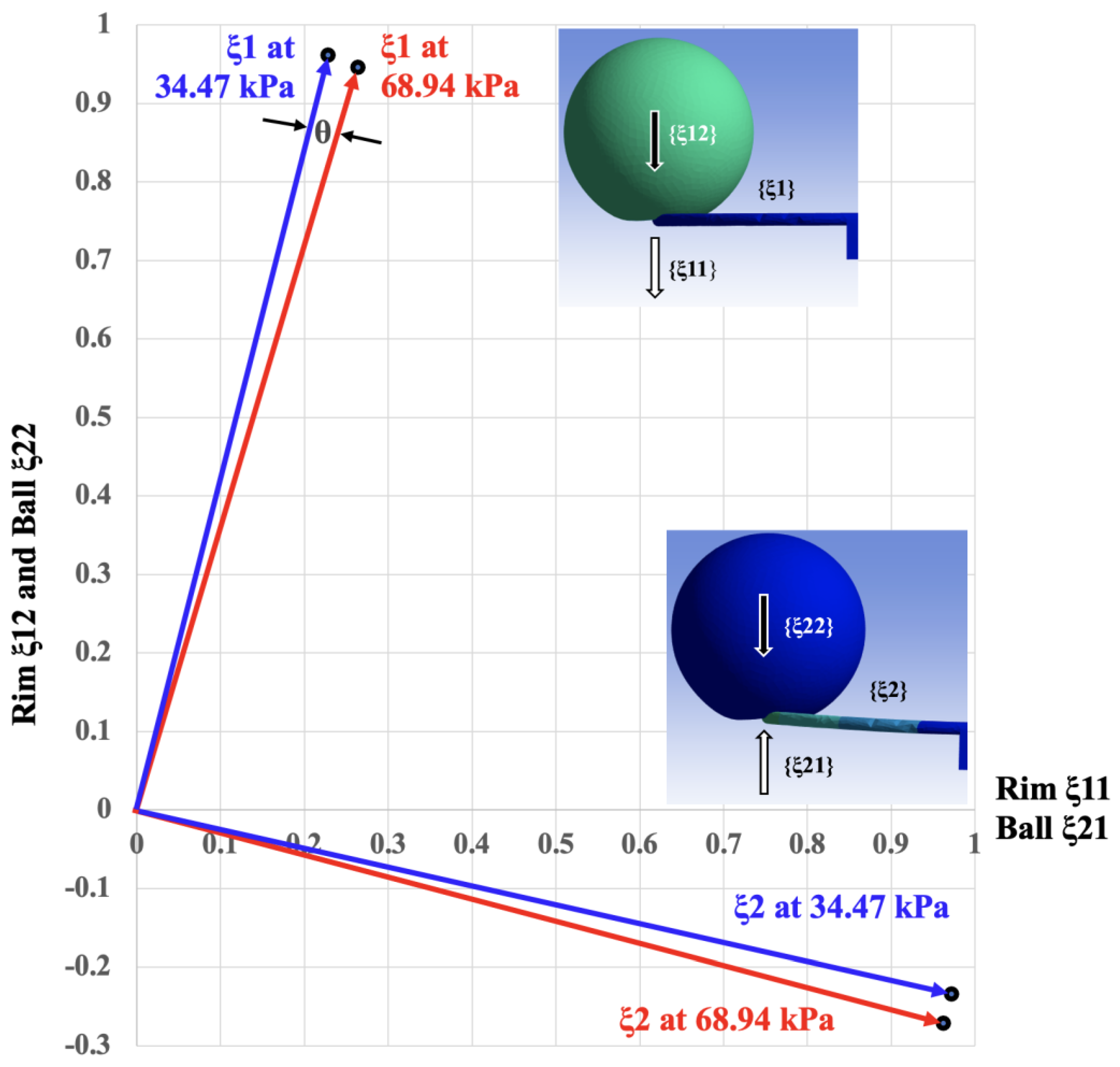

| {ξ1} | Orthonormal Eigenvector, describing vibration directions of mode-1 |

| {ξ2} | Orthonormal Eigenvector, describing vibration directions of mode-2 |

| ζ | Damping Ratio |

| θ | Rotation angle of Eigenvectors due to Inflation Pressure P, milliradians |

| ω | Natural Frequency, Hertz |

| ωd | Damped Natural Frequency, Hertz |

References

- Okubo, Hiroki, and Mont Hubbard. "Identification of basketball parameters for a simulation model." Procedia Engineering 2, no. 2 (2010): 3281-3286. (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Okubo, H., Hubbard, M. Dynamics of basketball-rim interactions. Sports Eng 7, 15–29 (2004) (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Okubo, H., and M. Hubbard. "Dynamics of the basketball shot with application to the free throw." Journal of sports sciences 24, no. 12 (2006): 1303-1314. (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Okubo, Hiroki, and Mont Hubbard. "Rebounds of basketball field shots." Sports Engineering 18 (2015): 43-54. (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Okubo, Hiroki, and Mont Hubbard. "Analysis of Arm Joint Torques at Ball-Release for Set and Jump Shots in Basketball." In Proceedings, vol. 49, no. 1, p. 4. MDPI, 2020. (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Okubo, Hiroki, and Mont Hubbard. "Kinematic differences between set-and jump-shot motions in basketball." In Proceedings, vol. 2, no. 6, p. 201. MDPI, 2018. (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tanaka: K.; Sekizawa, K. Construction of a finite element model of golf clubs and influence of shaft stiffness on its dynamic behavior. Proceedings 2018, 2, 247.

- Matsuda, A.; Nakui, M.; Hashiguchi, T. Simulation of Mechanical Characteristics of Tennis Racket String Bed Considering String Pattern. Proceedings 2018, 2, 264.

- Takizawa, M.; Matsuda, A.; Hashiguchi, T. A Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of String Planes of Badminton Racquets by Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis. Proceedings 2020, 49, 42.

- Yin, S.-R.; Chang, H.-C.; Cheng, K.B. Impact Characteristics of a Badminton Racket with Realistic Finite Element Modeling. Proceedings 2020, 49, 106.

- Javorski, M.; Čermelj, P.; Boltežar, M. Characterization of the Dynamic Behaviour of a Basketball Goal Mounted on a Ceiling. J. Mech. Eng./Stroj. Vestn. 2010, 56. Available online: https://www.sv-jme.eu/?ns_articles_pdf=/ns_articles/files/ojs3/1513/submission/1513-1-2001-1-2-20171103.pdf&id=5958 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Nkounhawa, Pascal Kuate, et al. "Analysis of the Behavior of a Square Plate in Free Vibration by FEM in Ansys." World Journal of Mechanics 10.02 (2020): 11-25.

- Guguloth, Ganesh Naik, Baij Nath Singh, and Vinayak Ranjan. "Free vibration analysis of simply supported rectangular plates." Vibroengineering Procedia 29 (2019): 270-273.

- Irvine, T. The Natural Frequency of a Rectangular Plate Point-Supported at Each Corner, Revision C. 1 August 2011. Available online: http://www.vibrationdata.com/tutorials2/plate_point_corner.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Dumond, P.; Monette, D.; Alladkani, F.; Akl, J.; Chikhaoui, I. Simplified setup for the vibration study of plates with simply- supported boundary conditions. Methods X 2019, 6, 2106–2117.

- Anđelić, N., M. Čanađija, and Z. Car. "Determination of Natural Vibrations of Simply Supported Single Layer Graphene Sheet using Non-Local Kirchhoff Plate Theory." IN-TECH 2017 International Conference on Innovative Technologies. 2017, p.5.

- Geveci, Berk, and J. D. A. Walker. "Nonlinear resonance of rectangular plates." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 457.2009 (2001): 1215-1240.

- Covill, D.; Drouet, J.-M. On the Effects of Tube Butting on the Structural Performance of Steel Bicycle Frames. Proceedings 2018, 2, 216.

- Model 3500 Positive Lock Breakaway Goal. Updated 21 January 2010. Gared Holdings, LLC. Available online: https://www. garedsports.com/sites/default/files/import/files/3500I%2520spec%2520-revA.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- 2024-2025 NCAA Men’s Basketball Rules Handbook, August 2024. Manuscript Prepared By: Jeff O’Malley, Secretary-Rules Editor, NCAA Men’s Basketball Rules Committee. Edited By: Andy Supergan, Associate Director of Playing Rules and Officiating. https://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/BK25.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Product Data: Piezoelectric Charge Accelerometer Types 4393 and 4393-V. Copyright 2018-08 by Brüel & Kjaer. Downloaded from: https://www.bksv.com/media/doc/bp2043.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- ANSYS 2025 R1 Student Edition: Available online: https://www.ansys.com/academic/students/ansys-student (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Winarski, Daniel, Kip P. Nygren, and Tyson Winarski. 2024. "Finite Element Analysis versus Empirical Modal Analysis of a Basketball Rim and Backboard" Vibration 7, no. 2: 582-594. Available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2571-631X/7/2/30. [CrossRef]

- Technical Documentation: Impact Hammer Type 8202. Copyright May, 1993 by Brüel & Kjaer. Available online: https://media. hbkworld.com/m/7a8ee3f9bea9db2b/original/Impact-Hammer-Type-8202.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Serridge, M.; Licht, T. Piezoelectric Accelerometers and Vibration Preamplifiers: Theory and Application Handbook; Brüel & Kjær: Naerum, Denmark, 1987. Available online: https://www.bksv.com/media/doc/bb0694.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Winarski, Daniel, Kip P. Nygren, and Tyson Winarski. 2023. "Modes of Vibration in Basketball Rims and Backboards and the Energy Rebound Testing Device" Vibration 6, no. 4: 726-742. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2571-631X/6/4/45. [CrossRef]

- Davis, Chandler. "The rotation of eigenvectors by a perturbation." Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications (US) 6 (1963). (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Davis, Chandler. "The rotation of eigenvectors by a perturbation. II." J. Math. Anal. Appl 11, no. 2 (1965): 27. (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Davis, Chandler, and William Morton Kahan. "The rotation of eigenvectors by a perturbation. III." SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 7, no. 1 (1970): 1-46. (accessed on 1 April 2025).

| Pertubation Mass Mp | Flexural Frequency ωd | Damping Ratio ζ |

|---|---|---|

| 0 kg (none) | 40.25 Hz | 0.19327% |

| 0.5 kg | 31.55 Hz | 0.16007% |

| Dynamic Mass M1 | Damping C1 | Spring Rate K1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.797 kg | 0.779 Ns/m | 50,960 N/m |

| A12N Ball Pressure |

Added Mass Ma |

Mode-1 ωd Frequency |

Mode-1 ζ Damping Ratio |

Mode-2 ωd Frequency |

Mode-2 ζ Damping Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68.94 kPa | 0.4658 kg | 18.88 Hz | 2.72% | 49.65 Hz | 1.48% |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.4658 kg | 17.73 Hz | 4.07% | 47.63 Hz | 2.29% |

| 68.94 kPa | 0.8658 kg | 16.43 Hz | 2.25% | 49.21 Hz | 1.52% |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.8658 kg | 15.07 Hz | 3.58% | 47.34 Hz | 1.84% |

| A12N Ball Pressure |

Added Mass Ma |

Mode-1 Frequency |

Mode-2 Frequency |

Eigenvalue |

Eigenvalue |

Ball Mass M2 |

Ball Spring Rate K2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68.94 kPa | 0.4658 kg | 18.88 Hz | 49.65 Hz | 14072.2 s-2 | 97319.0 s-2 | 0.503 kg | 20,748 N/m |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.4658 kg | 17.73 Hz | 47.63 Hz | 12410.1 s-2 | 89561.3 s-2 | 0.481 kg | 16,457 N/m |

| 68.94 kPa | 0.8658 kg | 16.43 Hz | 49.21 Hz | 10657.0 s-2 | 95601.7 s-2 | 0.454 kg | 21,029 N/m |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.8658 kg | 15.07 Hz | 47.34 Hz | 8965.73 s-2 | 88474.0 s-2 | 0.489 kg | 16,812 N/m |

| Component | TET10 Elements | Nodes | Corner Nodes | Mid Nodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gared Rim | 1827 | 3861 | 685 | 3176 |

| A12N Basketball | 6955 | 14053 | 2374 | 11679 |

| Total | 8782 | 17914 | 3059 | 14855 |

| A12N Ball Pressure P |

Added Mass Ma |

Mode-1 {ξ1} Eigenvector |

Mode-2 {ξ2} Eigenvalue |

{ξ1}T[M]{ξ2} |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68.94 kPa | 0.4658 kg | {0.2641, 0.9459}T | {0.9624, -0.2716}T | 0.0 |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.4658 kg | {0.2282, 0.9614}T | {0.9722, -0.2341}T | 0.0 |

| 68.94 kPa | 0.8658 kg | {0.2569, 0.9493}T | {0.9806, -0.1961}T | 0.0 |

| 34.47 kPa | 0.8658 kg | {0.2224, 0.9636}T | {0.9869, -0.1609}T | 0.0 |

| Added Mass Ma |

A12N Ball Pressure P |

Ball Spring Rate K2 |

A12N Ball Pressure P |

Ball Spring Rate K2 |

ΔK2/ΔP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4658 kg | 68.94 kPa | 20,748 N/m | 34.47 kPa | 16,457 N/m | 0.124 m |

| 0.8658 kg | 68.94 kPa | 21,029 N/m | 34.47 kPa | 16,812 N/m | 0.122 m |

| Added Mass Ma |

Mode | A12N Ball Pressure P |

Damping Ratio ζ |

A12N Ball Pressure P |

Damping Ratio ζ |

Δζ/ΔP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4658 kg | 1 | 68.94 kPa | 2.72% | 34.47 kPa | 4.07% | -0.0392 %/kPa |

| 0.4658 kg | 2 | 68.94 kPa | 1.48% | 34.47 kPa | 2.29% | -0.0235 %/kPa |

| 0.8658 kg | 1 | 68.94 kPa | 2.25% | 34.47 kPa | 3.58% | -0.0386 %/kPa |

| 0.8658 kg | 2 | 68.94 kPa | 1.52% | 34.47 kPa | 1.84% | -0.0093 %/kPa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).