Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Measurement of Cardiac Function and Infarct Size

2.2. Isolation of SSM and IFM

2.3. Assessing Calcium Retention Capacity (CRC) in the Isolated SSM

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

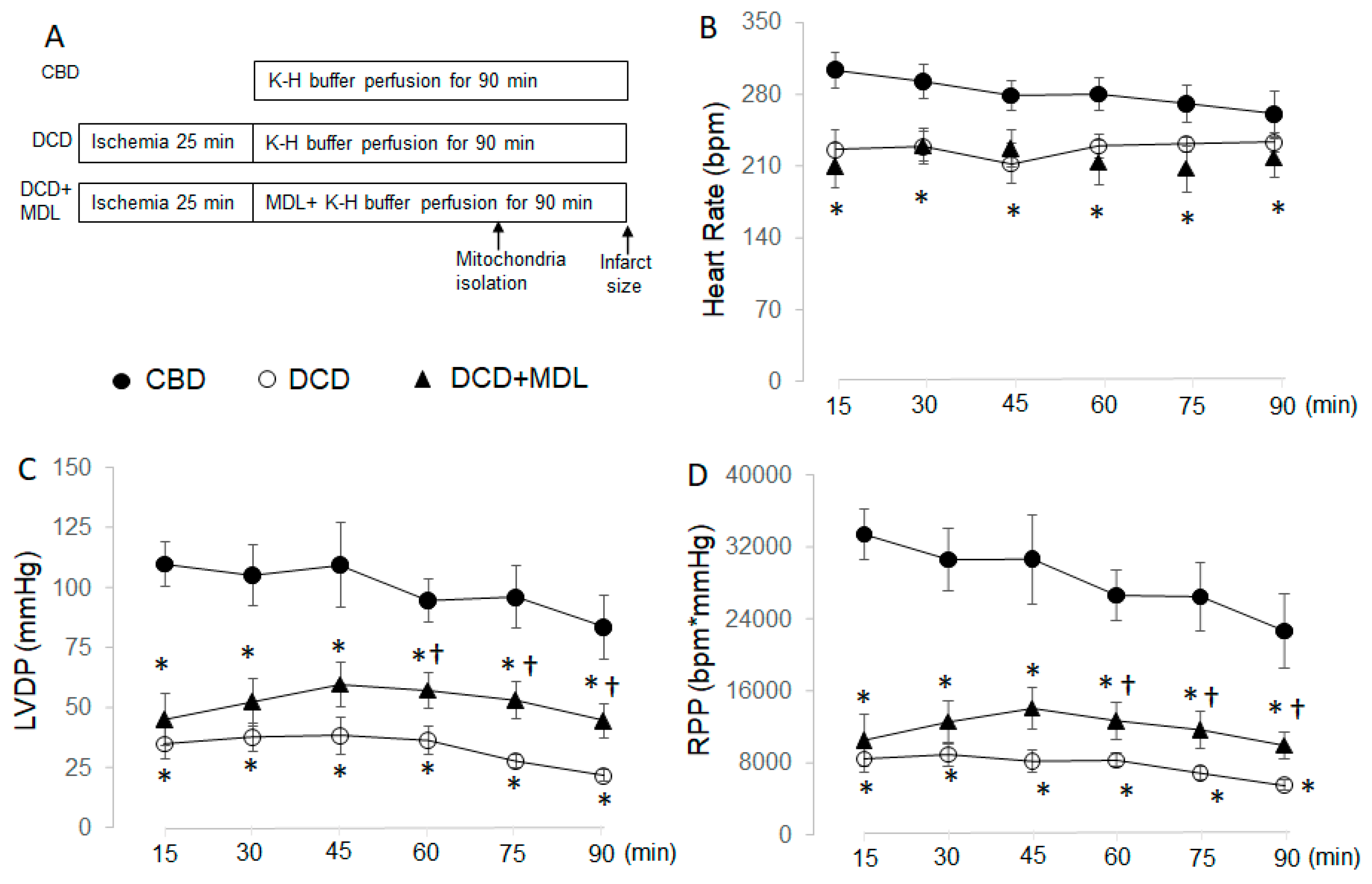

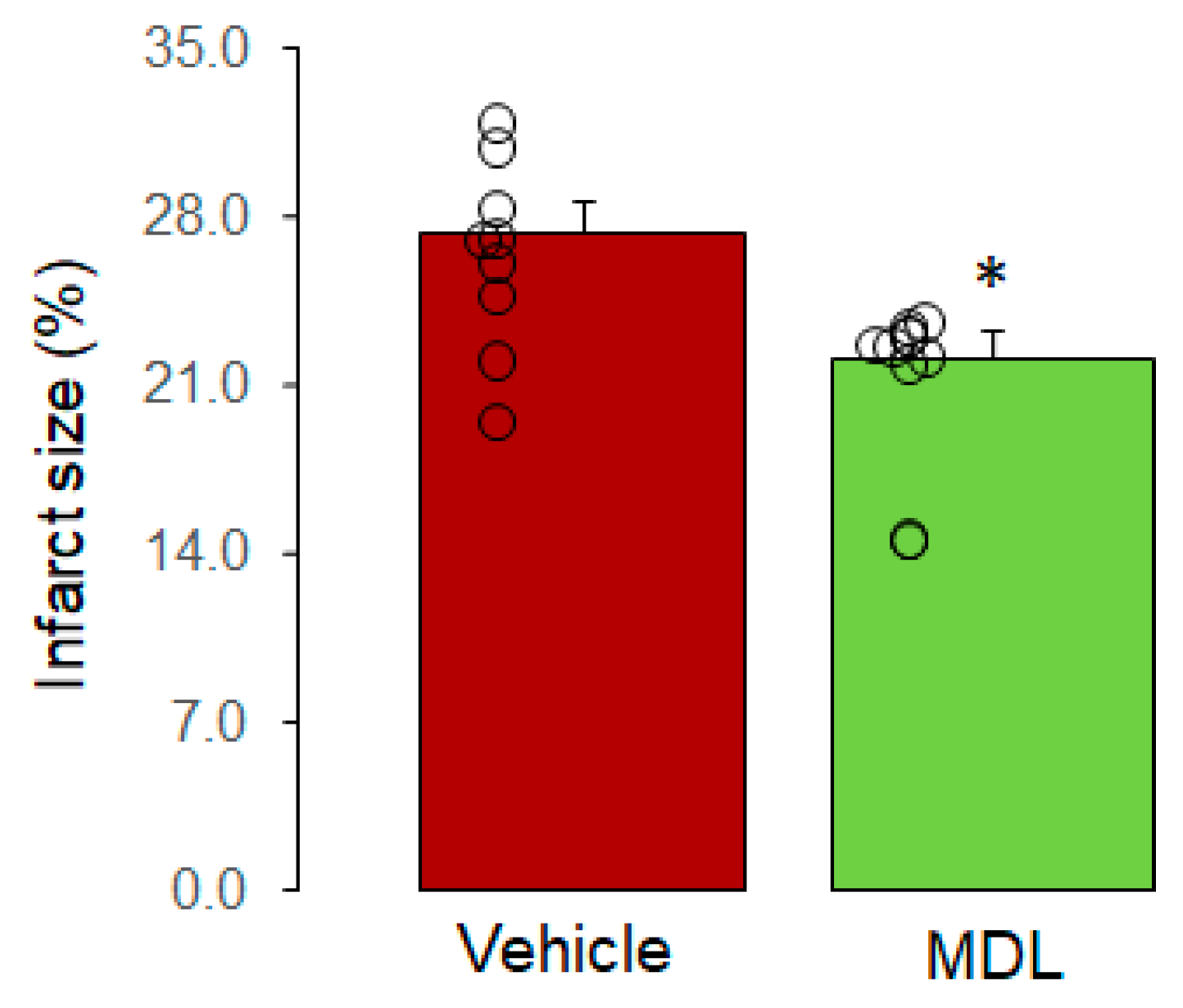

3.1. Inhibition of CPN1/2 Decreases Cardiac Injury in DCD Hearts

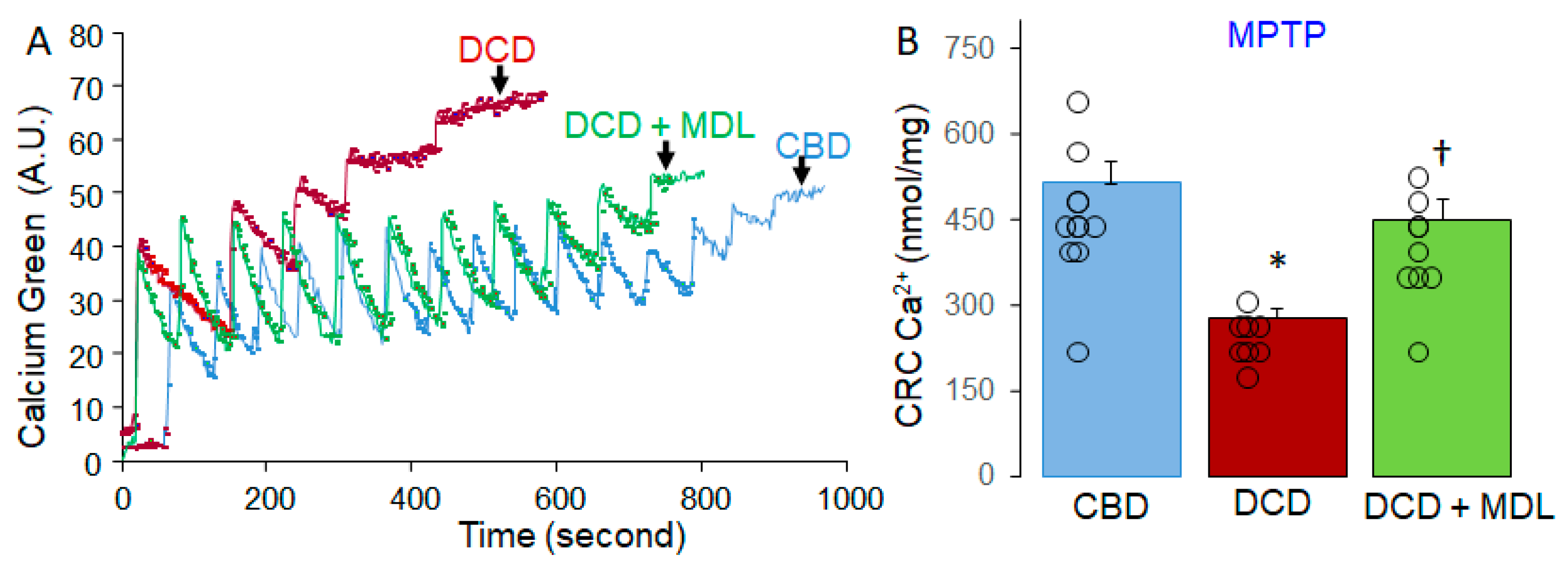

3.2. MDL Treatment Decreased MPTP Opening in DCD Hearts

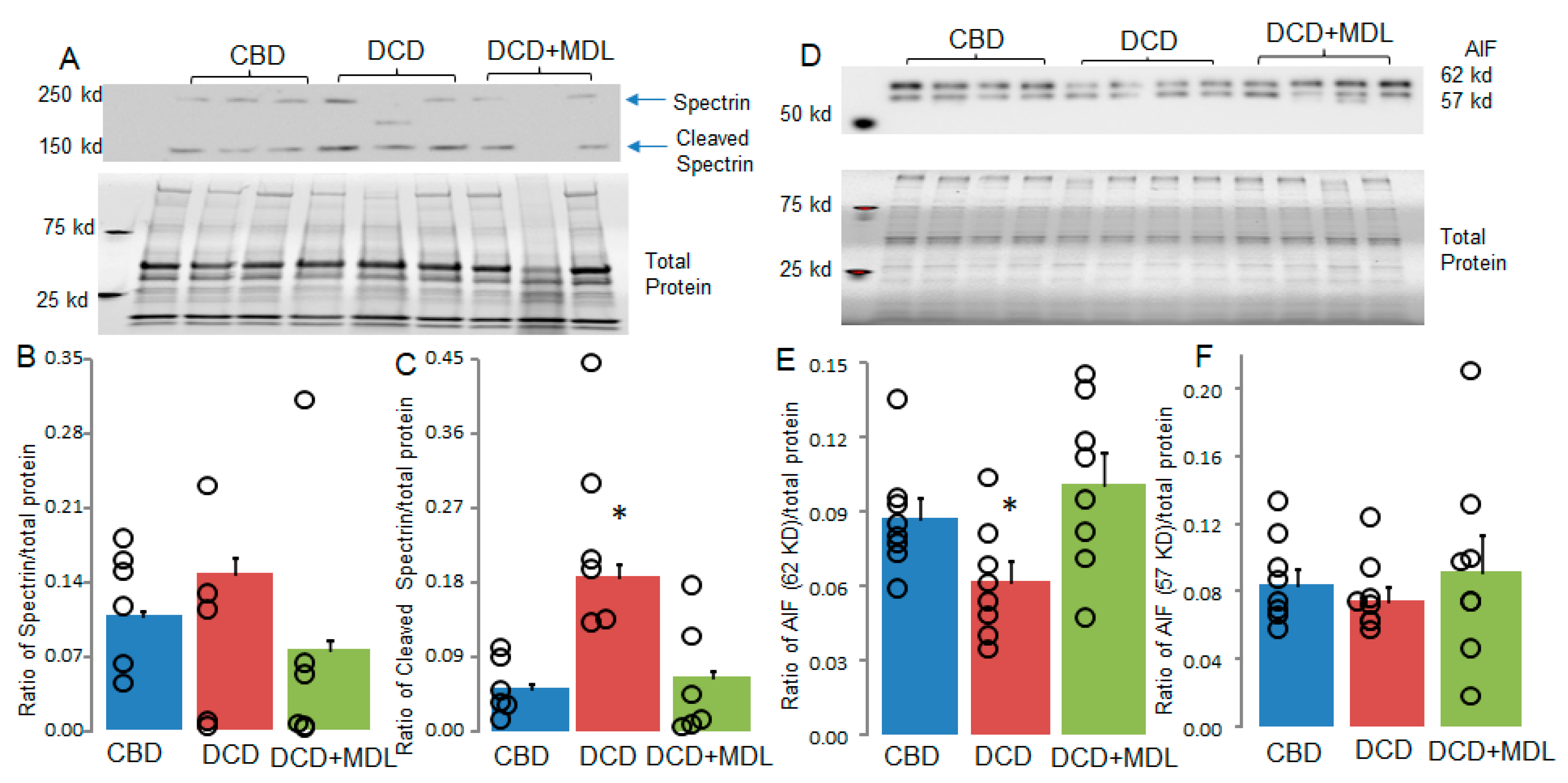

3.3. MDL Treatment Decreased the Activation of cCPN1/2 and mCPN1/2 in DCD Hearts

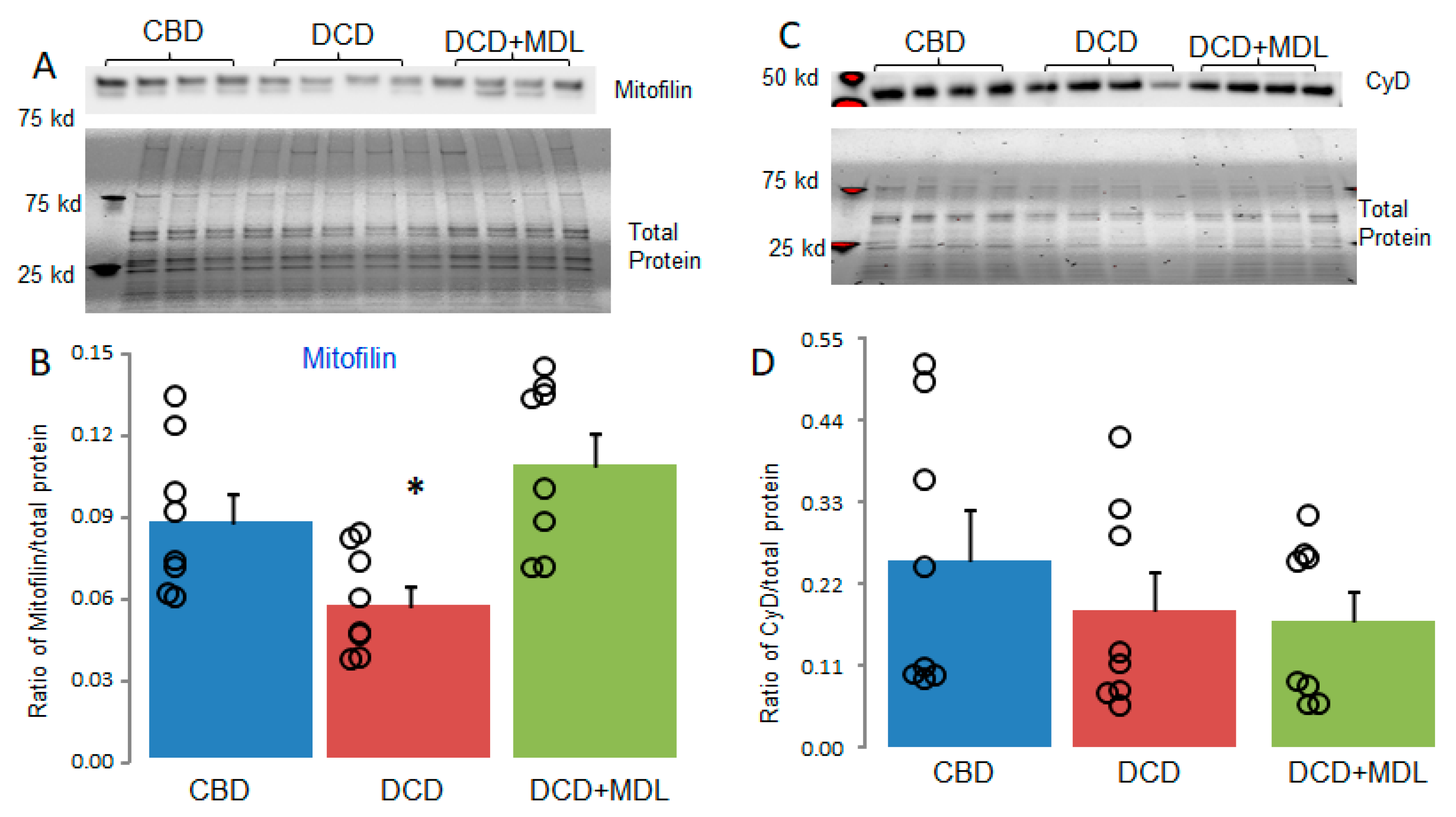

3.4. MDL Treatment Decreased the Degradation of Mitofilin in DCD Hearts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| AIF | Apoptosis-inducing factor |

| CBD | Control beating-heart donor |

| CPN1 | Calpain-1 |

| CPN2 | Calpain-2 |

| CPN1/2 | calpain-1 and calpain-2 |

| cCPN1/2 | cytosolic calpain-1 and calpain-2 |

| CRC | Calcium retention capacity |

| DCD | Donation after circulatory death |

| HR | Heart rate |

| IFM | interfibrillar mitochondria |

| LVDP | left ventricular developed pressure |

| MDL | MDL-28170 |

| mCPN1/2 | Mitochondria-localized calpain-1 and calpain-2 |

| MOPS | 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid |

| MPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| RPP | Rate-pressure product |

| SSM | Subsarcolemmal mitochondria |

| tAIF | truncated apoptosis-inducing factor |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quader, M.; Toldo, S.; Chen, Q.; Hundley, G.; Kasirajan, V. Heart transplantation from donation after circulatory death donors: Present and future. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawil, M.; Wang, W.; Chandiramani, A.; Zaqout, F.; Diab, A.H.; Sicouri, S.; Ramlawi, B.; Haneya, A. Survival after heart transplants from circulatory-dead versus brain-dead donors: Meta-analysis of reconstructed time-to-event data. Transplant. Rev. 2025, 39, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, M.; Akande, O.; Toldo, S.; Cholyway, R.; Kang, L.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Chen, Q. The Commonalities and Differences in Mitochondrial Dysfunction Between ex vivo and in vivo Myocardial Global Ischemia Rat Heart Models: Implications for Donation After Circulatory Death Research. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H.K.; Trahanas, J.; Xu, M.; Wells, Q.; Farber-Eger, E.; Pasrija, C.; Amancherla, K.; Debose-Scarlett, A.; Brinkley, D.M.; Lindenfeld, J.; et al. Outcomes of Heart Transplant Donation After Circulatory Death. Circ. 2023, 82, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akande, O.; Chen, Q.; Toldo, S.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Quader, M. Ischemia and reperfusion injury to mitochondria and cardiac function in donation after circulatory death hearts- an experimental study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0243504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Z.; Labate, G.; Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Quader, M. Infarct Size Reduction with Cyclosporine A in Circulatory Death Rat Hearts: Reducing Effective Ischemia Time with Therapy During Reperfusion. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2024, 17, e011846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akande, O.; Chen, Q.; Cholyway, R.; Toldo, S.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Quader, M. Modulation of Mitochondrial Respiration During Early Reperfusion Reduces Cardiac Injury in Donation After Circulatory Death Hearts. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 80, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, M.; Chen, Q.; Akande, O.; Cholyway, R.; Mezzaroma, E.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Toldo, S. Electron Transport Chain Inhibition to Decrease Injury in Transplanted Donation After Circulatory Death Rat Hearts. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 81, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, M.; Akande, O.; Cholyway, R.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Toldo, S.; Chen, Q. Infarct Size with Incremental Global Myocardial Ischemia Times: Cyclosporine A in Donation After Circulatory Death Rat Hearts. Transplant. Proc. 2023, 55, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, M.; Mezzaroma, E.; Wickramaratne, N.; Toldo, S. Improving circulatory death donor heart function: A novel approach. JTCVS Tech. 2021, 9, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Heart mitochondria and calpain 1: Location, function, and targets. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 2372–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Yamashita, T.; Ishiguro, S.-I. Mitochondrial m-calpain plays a role in the release of truncated apoptosis-inducing factor from the mitochondria. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2009, 1793, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Shi, Q.; Ciampa, G.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, G.; Weiss, R.M.; Peng, T.; Hall, D.D.; Song, L.-S. Preventing Site-Specific Calpain Proteolysis of Junctophilin-2 Protects Against Stress-Induced Excitation-Contraction Uncoupling and Heart Failure Development. Circulation 2025, 151, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, Y.; Hagihara, H.; Ohga, Y.; Nakajima-Takenaka, C.; Murata, K.-Y.; Taniguchi, S.; Takaki, M. Calpain inhibitor-1 protects the rat heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury: analysis by mechanical work and energetics. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H1690–H1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wei, M.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Lacefield, J.C.; Greer, P.A.; Karmazyn, M.; Fan, G.-C.; et al. Deficiency of Capn4 Gene Inhibits Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) Protein Signaling/Inflammation and Reduces Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 27480–27489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bi, X.; Baudry, M. Calpain-1 and Calpain-2 in the Brain: New Evidence for a Critical Role of Calpain-2 in Neuronal Death. Cells 2020, 9, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inserte, J.; Hernando, V.; Garcia-Dorado, D. Contribution of calpains to myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 96, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, V.; Inserte, J.; Sartório, C.L.; Parra, V.M.; Poncelas-Nozal, M.; Garcia-Dorado, D. Calpain translocation and activation as pharmacological targets during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 49, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Willard, B.; Chen, Q. Calpain-mediated protein targets in cardiac mitochondria following ischemia–reperfusion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Chen, Q. Activation of mitochondrial calpain and increased cardiac injury: beyond AIF release. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2016, 310, H376–H384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Cao, T.; Zhang, L.-L.; Fan, G.-C.; Qiu, J.; Peng, T.-Q. Targeted inhibition of calpain in mitochondria alleviates oxidative stress-induced myocardial injury. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 42, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, M.; Mezzaroma, E.; Kenning, K.; Toldo, S. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome to reduce warm ischemic injury in donation after circulatory death heart. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e14044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, M.; Mezzaroma, E.; Kenning, K.; Toldo, S. Modulation of Interleukin-1 and -18 Mediated Injury in Donation after Circulatory Death Mouse Hearts. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 257, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Aliagan, A.I.; Tombo, N.; Bopassa, J.C. Mitofilin Heterozygote Mice Display an Increase in Myocardial Injury and Inflammation after Ischemia/Reperfusion. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madungwe, N.B.; Feng, Y.; Lie, M.; Tombo, N.; Liu, L.; Kaya, F.; Bopassa, J.C. Mitochondrial inner membrane protein (mitofilin) knockdown induces cell death by apoptosis via an AIF-PARP-dependent mechanism and cell cycle arrest. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2018, 315, C28–C43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombo, N.; Aliagan, A.D.I.; Feng, Y.; Singh, H.; Bopassa, J.C. Cardiac ischemia/reperfusion stress reduces inner mitochondrial membrane protein (mitofilin) levels during early reperfusion. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 158, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurembo, A.I.; Xing, N.; Chanda, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.-J.; Fu, L.-D.; Huang, J.-Y.; Xu, Y.-J.; Deng, W.-H.; Cui, H.-D.; et al. Mitofilin in cardiovascular diseases: Insights into the pathogenesis and potential pharmacological interventions. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 203, 107164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, D.; Nichols, C.E.; Lewis, S.E.; Shepherd, D.L.; Jagannathan, R.; Croston, T.L.; Tveter, K.J.; Holden, A.A.; Baseler, W.A.; Hollander, J.M. Transgenic overexpression of mitofilin attenuates diabetes mellitus-associated cardiac and mitochondria dysfunction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 79, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillard, M.; Gomez, L.; Augeul, L.; Loufouat, J.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Ovize, M. Postconditioning inhibits mPTP opening independent of oxidative phosphorylation and membrane potential. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 46, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.R.; Bartos, J.A.; Tsangaris, A.; Shekar, K.C.; Olson, M.D.; Riess, M.L.; Bienengraeber, M.; Aufderheide, T.P.; Neumar, R.W.; Rees, J.N.; et al. Early Effects of Prolonged Cardiac Arrest and Ischemic Postconditioning during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation on Cardiac and Brain Mitochondrial Function in Pigs. Resuscitation 2017, 116, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Samidurai, A.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Willard, B.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Acute endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced mitochondria respiratory chain damage: The role of activated calpains. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Paillard, M.; Gomez, L.; Ross, T.; Hu, Y.; Xu, A.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Activation of mitochondrial μ-calpain increases AIF cleavage in cardiac mitochondria during ischemia–reperfusion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 415, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Dean, J.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Inhibition of the ubiquitous calpains protects complex I activity and enables improved mitophagy in the heart following ischemia-reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2019, 317, C910–C921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Reversing mitochondrial defects in aged hearts: role of mitochondrial calpain activation. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2022, 322, C296–C310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Tomita, H.; Tamai, M.; Ishiguro, S.-I. Characteristics of Mitochondrial Calpains. J. Biochem. 2007, 142, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani-Ishida, K.; Yoshida, K.-I. Mitochondrial m-calpain opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in ischemia–reperfusion. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 197, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, C.P.; Kaiser, R.A.; Purcell, N.H.; Blair, N.S.; Osinska, H.; Hambleton, M.A.; Brunskill, E.W.; Sayen, M.R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Dorn, G.W., II.; et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature 2005, 434, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, G.; Peng, T. Calpain-Mediated Mitochondrial Damage: An Emerging Mechanism Contributing to Cardiac Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Lesnefsky, E.J. The mitochondrial electron transport chain contributes to calpain 1 activation during ischemia-reperfusion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 613, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P.; Clarke, S.J.; Javadov, S.A. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening during myocardial reperfusion--a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 61, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, H.J.; Yang, M.; Heisner, J.S.; Camara, A.K.; Stowe, D.F. Modulation of peroxynitrite produced via mitochondrial nitric oxide synthesis during Ca2+ and succinate-induced oxidative stress in cardiac isolated mitochondria. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 2020, 1861, 148290–148290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, P.; Gerle, C.; Halestrap, A.P.; Jonas, E.A.; Karch, J.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Pavlov, E.; Sheu, S.-S.; Soukas, A.A. Identity, structure, and function of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: controversies, consensus, recent advances, and future directions. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlicher, R.; Drahota, Z.; Štefková, K.; Červinková, Z.; Kučera, O. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore-Current Knowledge of Its Structure, Function, and Regulation, and Optimized Methods for Evaluating Its Functional State. Cells 2023, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garciadorado, D.; Rodriguezsinovas, A.; Ruizmeana, M.; Inserte, J.; Agulló, L.; Cabestrero, A. The end-effectors of preconditioning protection against myocardial cell death secondary to ischemia–reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 70, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Akande, O.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Quader, M. Influence of sex on global myocardial ischemia tolerance and mitochondrial function in circulatory death donor hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2023, 324, H57–H66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.; Ray, S.K.; Banik, N.L. Calpain as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Parkinsons Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. - Drug Targets 2008, 7, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.R.; Baetz, D.; Ovize, M. Cyclophilin D and myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury: A fresh perspective. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 78, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrod, J.W.; Molkentin, J.D. Physiologic Functions of Cyclophilin D and the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. Circ. J. 2013, 77, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody name | Company | Catalog number | Concentration |

| AIF | Cell Signaling | 4642 | 1:1000 |

| Mitofilin | ThermoFisher Scientific | MA3-940 | 1:1000 |

| Spectrin | Santa Cruz | csc-46696 | 1:100 |

| VDAC | Abcam | 14715 | 1:2500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).