Introduction

The process of probiotication involves the inoculation of beneficial microorganisms into a liquid substrate to create functional beverages that subsequently add market value due to the numerous health benefits of probiotics (Moreira et al., 2025). Consumers have now accepted the notion of “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food” due to more consciousness nowadays for maintaining and taking care of their health, leading to increased life expectancy in developing and developed nations (Kechagia et al., 2013). The concept of functional foods initially focused on finding foods that are employed to treat diseases and provide health benefits. Functional foods are also referred as medicinal foods, nutraceuticals, prescriptive foods, therapeutic foods, superfoods, designer foods, foodiceuticals, and medifoods that can be consumed in different forms i.e. either as fermented products/beverages or non-fermented products/beverages, e.g fruit juices, beetroot, fortified juices, fermented milk etc. (Prado et al., 2007). Probiotic beverages have been an integral part of human diets for thousands of years as fermentation or supplementation of foods/beverages with probiotics enhances their nutritional value, taste, and shelf life along with numerous health benefits (Panda et al., 2021). Moreover, fermentation has long been recognized globally for its role in food processing and preservation, traditionally relying on microorganisms from natural microbiota. However, with the expansion of the functional food market, the use of starter cultures has become prevalent, ensuring greater consistency and efficiency in fermentation processes (Sangwan et al., 2014).

The term probiotic is derived from greek word and means “for life” as opposed to the term antibiotic (Hill et al., 2014). According to Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization guidelines defined probiotics as ‘live microorganisms, which, when administered in adequate amounts confer health benefits to the host’ (Mazziotta et al., 2023). More specifically, probiotics are commonly found both in fermented foods or dietary supplements and have been researched for their potential to modulate gut microbiome vis-à-vis immune system thereby alleviating various gastrointestinal disorders, due to which probiotics are also referred as “Gastrointestinal Interference Therapy”.

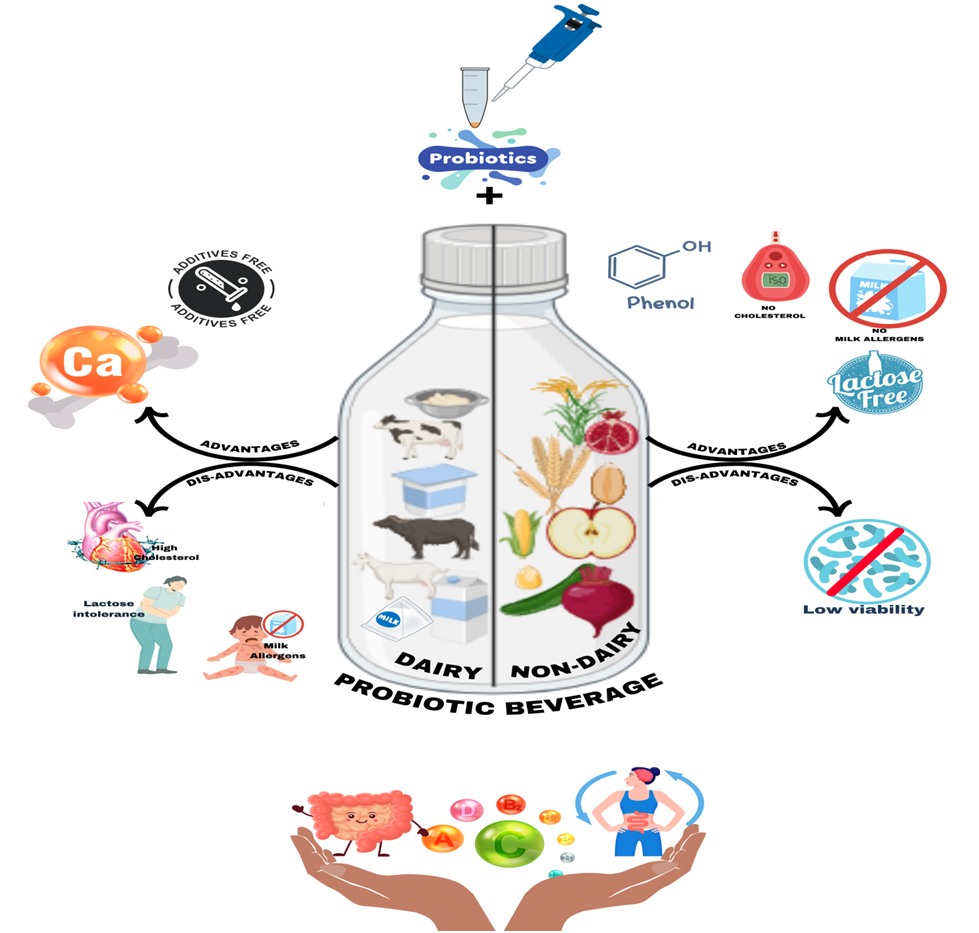

Fermented beverages are age-old products that serve as carriers of probiotics in the human diet. Probiotic beverages offer a convenient and effective alternative to probiotic-rich foods, providing an easy way to incorporate beneficial bacteria in one’s diet due to their gut-modulating potentiality mostly required for efficient digestion and nutrition absorption (Kandylis et al., 2016). The fermentation of milk, cereals, and various substrates with probiotics to create health-enhancing beverages is a traditional practice across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and South America. Probiotic beverages are mainly categorized as dairy-based probiotic beverages and non-dairy based probiotic beverages based on their source. These drinks, such as kefir, kombucha, and probiotic-infused juices, are typically fermented with live cultures that promote a healthy gut microbiome (Panda et al., 2021). Unlike solid probiotic foods, which may require more preparation or have specific dietary restrictions, probiotic beverages are often ready to consume. Additionally, non-dairy probiotic beverages like water kefir, kombucha, or other plant-derived beverages can be a great option for lactose intolerant or preferably vegan individuals. Fermented beverage like kombucha is normally produced by fermenting sweetened tea with a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) has gained popularity as natural sources of probiotics due to presence of beneficial microbes and organic acids leading to improved gut health and antioxidant properties (Jayabalan et al., 2014; Villarreal-Soto et al., 2018). The beverage industry has responded to the growing demand for probiotic products by developing various non-dairy options e.g. fruit juices, have been supplemented with probiotics to cater to consumers seeking dairy-free alternatives (Ranadheera et al., 2017; Reque & Brandelli, 2021; Natt and Katyal, 2022). Moreover, these probiotic beverages have been shown to alleviate symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and reduce the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea vis-á-vis strengthening the immune system (Fenster et al., 2019). Fenster et al (2019) have also indicated that regular consumption of probiotic-rich drinks can reduce the duration and severity of respiratory infections. In addition to gut and immune health, emerging research suggests that probiotic beverages may have positive effects on mental health and can alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, although more research is needed as efficacy of probiotic beverages are very much dependent on specific species and strains used, dosage, and individual health conditions (Laali et al., 2018; Fenster et al., 2019; Merkouris et al., 2024). Keeping the beneficial potential of probiotic beverages, this review summarizes different types of both dairy and non-dairy based probiotic beverages and their impact on human health along with their future prospects.

Traditional Fermented Beverages

Traditional fermented/preserved foods and beverages have long been intertwined with ethnic traditions and cultural heritage, serving as essential components of ancient diets (Flach et al., 2018). Moreover, historical records have indicated that between 2000 and 3000 BC, fermented milk products, including milk, butter, and cheese, were consumed widely across the various civilizations, i.e. Indians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans (Caramia et al., 2008). Further, archaeological evidence from pottery vessels suggests that fermented beverages were made either from rice, honey or fruits, in China as early as 7000 B.C. (Dufresne & Farnworth; 2000). Traditionally, beverages were prepared without an understanding of the scientific principles behind microbial involvement; but nowadays, modern food scientists have started harnessing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) with probiotic properties to transform indigenous foods and beverages into innovative formulations that align with evolving consumer demands (Behera et al., 2020).

Probiotic Beverages

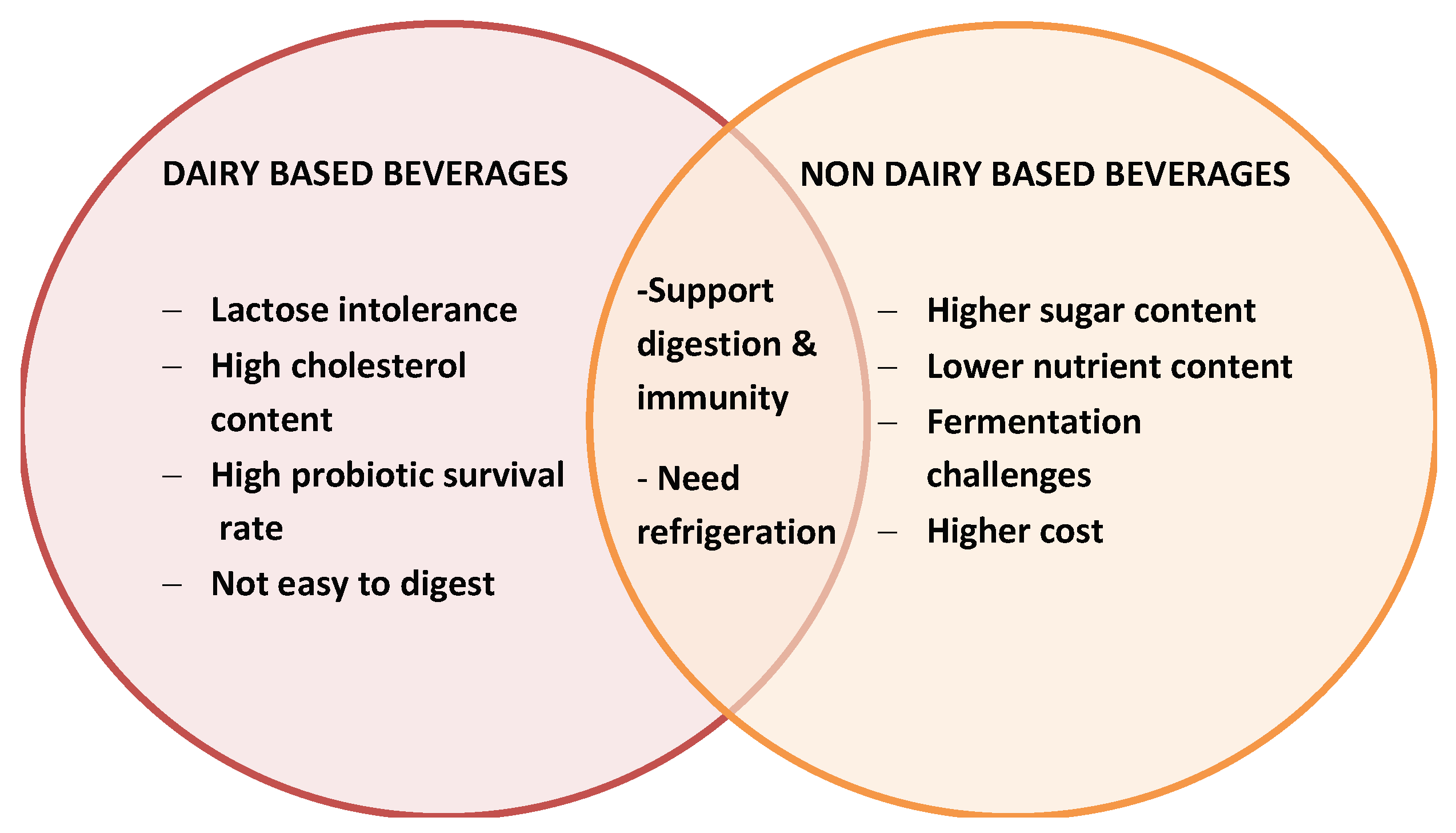

Functional drinks are among the most advanced products in the market and are widely valued by consumers for their health benefits particularly gut, liver, immune response and nutritional content. The global Probiotic Drinks Market size is estimated at USD 45.17 billion in 2025, and is expected to reach USD 72.15 billion by 2030, at a Compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.82% during the forecast period between 2025 and 2030. Conventionally probiotic beverages were prepared from dairy products that have traditionally served as the vehicles for probiotic bacteria in humans such as yogurt, kefir, acidophilus milk and butter milk, but due to high cholesterol level and lactose intolerance in some people its use was limited (Prado et al., 2008). To overcome such issues, non-dairy based probiotic beverages are taking over the market and diverse non-dairy based probiotic beverages from seeds, grains, legumes, fruits, vegetables etc have been developed, for example : oat milk, sesame milk probiotic, apple juice based probiotic beverage etc. (Tiwari et al., 2011). More specifically, increased awareness regarding health and fitness trends has prompted young consumers more due to low-calorie, high biotic compound potential and are safe for lactose intolerant population (Panghal et al., 2018).

To maximize the modulatory potential of probiotic beverages, fortification is being carried out with a group of nutrients that favors the growth of gut microbiota and is referred as prebiotics that may be present in both dairy and non-dairy products. These prebiotics may interact with probiotics to change their functional properties and majority of them are oligosaccharide such as inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides, isomalto-oligosaccharides, human milk oligosaccharides, xylo-oligosaccharides, xylan, lactulose, oat fiber (β-glucan), pectin, guar gum, resistant starch, stachyose, certain polyphenols, bacteriophages, omega-3 fatty acids, and yeast hydrolysate (Das

et al.,2019; Ansari

et al.,2020; Olson

et al.,2022). Prebiotics are naturally present in different dietary food products, including asparagus, sugar beet, garlic, chicory, onion, Jerusalem artichoke, wheat, honey, banana, barley, tomato, rye, soybean, human’s and cow’s milk, peas, beans, seaweeds and microalgae. Some of the prebiotics are produced by using lactose, sucrose, and starch as raw material (Varzakas

et al., 2018). Non-dairy probiotic beverages may contain prebiotics such as inulin that may interact with probiotics to change their functional properties (Ranadheera

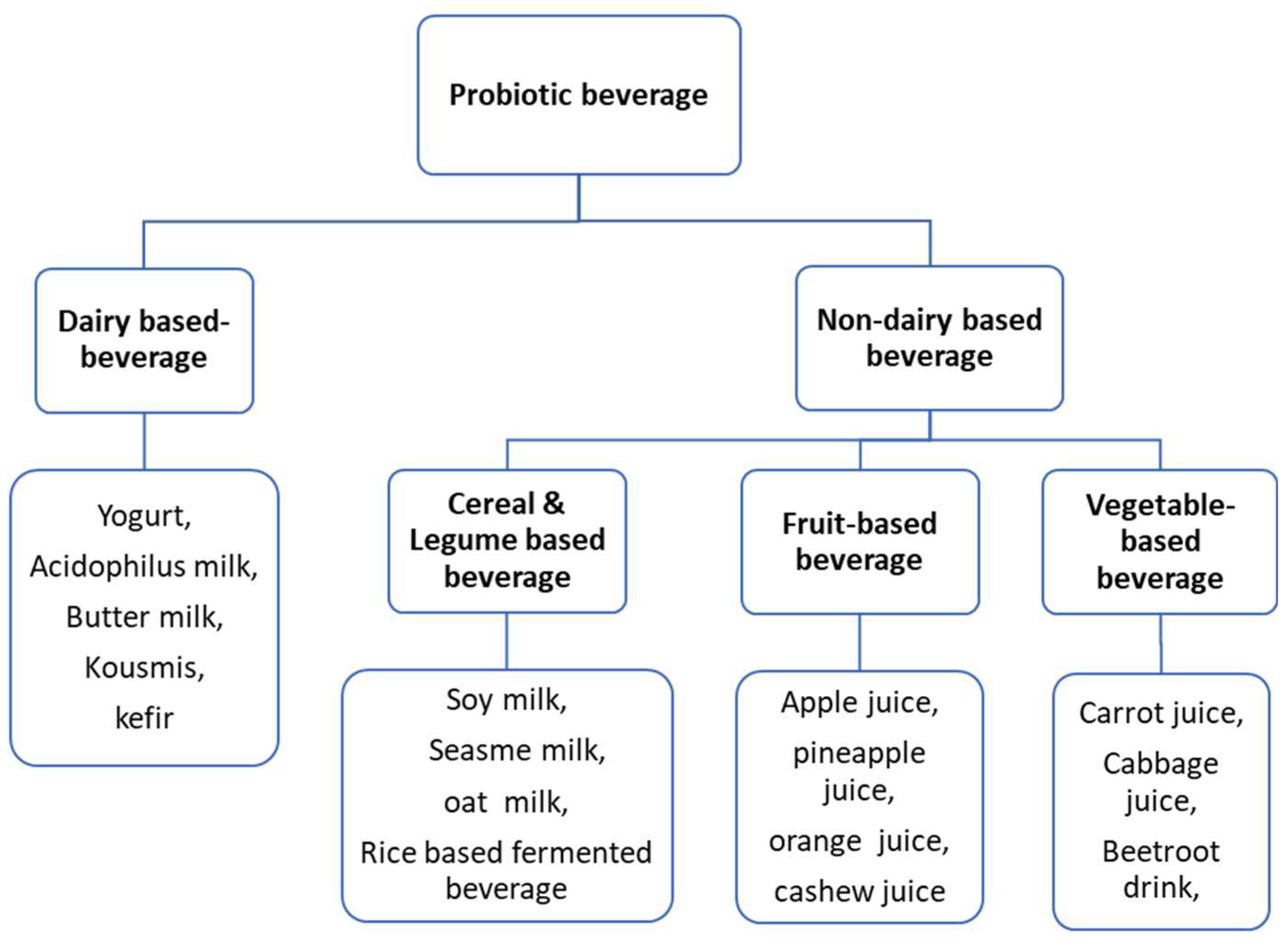

et al., 2017). So, the choice of having a dairy or non-dairy based probiotic beverage totally depends on the purpose of consumption (i.e the health concern) and the consumer’s preference. The various types of probiotic beverages with specific examples are summarized in

Figure 1.

Dairy Based Beverages

Probiotic dairy based beverages, serving as functional foods has long been in the market, accounting for over 40% of this market. As per Future Market insights the segment of dairy based probiotic beverage accounted for 55.4% of the global market in 2022. Since the probiotic growth is considered more favorable in fermented dairy or yogurt based beverages, the consumption or popularity of these probiotic drinks have increased exclusively, all over the world.

Fermented dairy product drinks commonly containing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as probiotics are becoming increasingly common in the dairy sector. The various types of commercial dairy based probiotic products and the microorganisms used are listed in

Table 1.

Yogurt, kefir, and acidophilus milk are typical examples of fermented dairy based probiotic drinks and the most frequently utilized probiotics are Bifidobacterium sp., Lactobacillus sp., Lacticaseibacillus sp., Limosilactobacillus sp., Lactiplantibacillus sp., Ligilactobacillus sp., and Lactobacillus sp.. The probiotics, L. plantarum and Bifidobacterium sp. are frequently used due to their strong antioxidant potential and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory effects caused by presence of proteins, minerals, and fermentation-produced bioactive compounds i.e short chain fatty acids (Meybodi et al., 2020).

Yogurt Beverages

Yogurt is made by fermenting milk with specific bacteria, mainly Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. Other ingredients like sweeteners, flavors, colors, thickeners, and vitamins A and D can also be added and is available in various forms, such as spoonable, drinkable, Greek (concentrated), dried, low-lactose, shelf-stable, and frozen (Olson et al., 2022; Gürakan et al.,2009). It can also be used as an ingredient in other foods e.g. coating or a snack. In addition to traditional varieties, the development of probiotic yogurt beverages is gaining momentum, driven by increasing consumer demand for functional and value-added products (Sarkar et al., 2018).

Koumiss (Kumiss)

Koumiss, also known as airag, a traditional fermented beverage widely consumed by nomadic cattle breeders in Asia and certain regions of Russia. It is prepared using mare's milk, which undergoes fermentation either through back-slopping or natural fermentation processes mainly with L. delbreuckii and K. marxianus (Kim et al., 2017). It has been traditionally recommended for the management of various health conditions, e.g. tuberculosis, asthma, pneumonitis, cardiovascular disorders, and gynecological diseases. Additionally, koumiss is recognized for its potential to promote weight gain, enhance energy levels, and improve overall robustness (Marsh et al., 2014).

Kefir

Kefir is a fermented milk product produced with kefir grains or mother cultures Kefir grains comprising of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), yeasts, casein, and complex sugars embedded within a polysaccharide matrix. They also include non-lactose-fermenting yeasts and acetic acid bacteria (AAB), forming a unique symbiotic microbial community. The composition of kefir microbiota varies depending on the substrate and production methods employed and probiotic potential of kefir include protection against toxins and inhibition of Helicobacter pylori (Arslan et al., 2015).

Acidophilus Milk

Traditionally, acidophilus milk is prepared using buffalo milk inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus (3%–5%) and incubated for 12–16 hours at 38°C–40°C. The process includes breaking the coagulum, cooling, packaging, and storing the product at 5°C. While primarily developed with L. acidophilus, it can also be produced using Bacillus acidophilus. Acidophilus milk has a very distinctive tangy flavor with short shelf-life as most strains of L. acidophilus produce more organic acids at low temperature. Acidophilus milk is recognized for its significant gastrointestinal health benefits (Hati et al., 2013). While L. acidophilus is the predominant strain used for prepration of acidophilus milk, there is potential for incorporating other beneficial strains, such as Bifidobacterium and Propionibacterium, having enhanced health benefits (Morya et al., 2022). As with sweet acidophilus milk, L .acidophilus and B. bifidum can be added to cold milk around 5 °C to produce unfermented Acidophilus–Bifidus milk (Özer & Kirmaci, 2010).

Bifidus Milk

Bifidus milk, first developed in 1948 in Germany, was the first infant formula to incorporate bifidobacteria. Heat-treated milk cooled to 37°C is inoculated with a 10% culture of either Bifidobacterium bifidum or Bifidobacterium longum and is used in the management of gastrointestinal, liver disorders and constipation (Shilby et al., 2013).

Acidophilus–Bifidus Milk

Acidophilus–Bifidus milk, also referred to as AB culture, is a fermented dairy product containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium species in 1:1 ratio. Inoculation is achieved at 37 °C using L. acidophilus and B. bifidum and the incubation is ended at pH 4.5–4.6 which usually takes 14–16 h and the end product is slightly acidic and viscous.

Drawbacks of Dairy Based Beverages

Dairy based probiotic drinks are consumed by people since long but due to major drawbacks of dairy based probiotic beverages such as lactose intolerance, presence of milk protein allergens and high cholesterol content, their use is limited.

Lactose Intolerance

Dairy products contain lactose which is digested by the enzyme lactase produced in our small intestine, but individual devoid of lactase are lactose intolerant, therefore, the lactose in the food rather than being processed or adsorbed, moves into the colon and interacts with colon’s normal flora leading to lactose intolerance characterized by diarrhea, bloating, vomiting etc (Deng et al., 2015).

Milk protein allergens

Cow’s milk allergy is among the most common food allergies in children, and about 15% of allergic children stay allergic due to two major allergens: casein (αs1-CN) and β-lactoglobulin besides, many other milk proteins. Therefore, presence of the milk protein allergens within the probiotics can trigger several allergies. Teitelbaum et al. 2024 have reported that a 13 year old female developed anaphylaxis after consuming cow’s milk protein, supporting the notion that children can be allergic to milk protein.

High cholesterol content

The fat level of milk varies based on it’s source, as it has been observed that cow milk contains about 4-5 % fat, whereas buffalo milk has roughly 7-8 % fat. However, an excessive intake of saturated fats and cholesterol causes an increase in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in the blood plasma, and the accumulation of these bad cholesterol leads to atherosclerosis, a condition where the artery experiences a blockage due to plaque formation, and the supply of oxygen to the heart is reduced leading to occurrence of heart attacks and, even death (Rafieian et al., 2017).

Non-Dairy Based Beverages

To overcome the adverse effects of dairy based probiotic beverages, nowadays non-dairy probiotic are preferred due to their health promoting properties and high nutritional value (Kumar

et al., 2015). The continuing trend in vegetarianism and the exorbitant pervasiveness of lactose sensitivity in broad societies across the world are the other reasons why non-dairy probiotic foods have acquired global prominence. Adding probiotics to fruit juices is inherently more challenging than incorporating them into dairy products due to specific intrinsic properties of fruit juices, such as low pH and high organic acid concentration, compounded by critical factors such as storage time and the probiotic viability. Furthermore, the high perishability and significant water content of fruit juices contribute to increased transportation and production costs (Gomes

et al., 2021). Fermented as well as fortified- probiotic beverage can also be prepared with non-dairy products. Traditional non-dairy fermented beverages come in a vast array of varieties and a large portion of them are non-alcoholic drinks made primarily from cereal grains (Prado

et al., 2008). Non-dairy probiotic beverages can be cereal based, vegetable based or fruit based as presented in

Figure 1. Various types of non-dairy based probiotic beverages and the microorganisms used are listed in

Table 2.

Fruit and Vegetable Based Beverage

Fruits and vegetables are naturally rich in carbohydrates, dietary fibers, vitamins, minerals, polyphenols, and phytochemicals, making them valuable components of a healthy diet (Sutton, 2007). Researchers have explored various fruit and vegetable juices, including tomato, mango, orange, apple, grape, peach, pomegranate, watermelon, carrot, beetroot, and cabbage, as potential raw materials for probiotic juice or beverage production. Fruit or vegetable sugar such as glucose, sucrose and fructose are converted into pyruvate and lactic acid. The d- or l-lactate dehydrogenase enzyme (aldolases enzymes) is a component of the metabolic pathway that converts 1 mol of glucose into 2 mol of lactic acid and 2 mol of ATP (Raj et al., 2022). This lactic acid is the main byproduct of fermentation carried out by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which are key probiotic organisms. Fruits not only provide fermentable sugars for LAB but also contain prebiotic fibers that enhance their growth and activity. Commonly used probiotics include various Lactobacillus species such as L. acidophilus, L. helveticus, L. casei, L. paracasei, L. johnsonii, L. plantarum, L. gasseri, L. reuteri, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, , L. fermentum, and L. rhamnosus, along with Bifidobacterium species like B. bifidum, B. longum, B. adolescentis, B. infantis, B. breve, and B. lactis. Other probiotics studied include Escherichia coli Nissle, Streptococcus thermophilus, Weissella spp., Propionibacterium spp., Pediococcus spp., Enterococcus faecium, Leuconostoc spp., and Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii (Nagpal et al., 2012). A probiotic beverage prepared from cashew apple juice has been shown to be a suitable substrate for probiotic growth without the preservatives or even heat treatment and was stable for up to 42 days under refrigeration with minimal viability and with intensified yellowness during fermentation and storage (Pereira et al., 2011). However, a key challenge in probiotic beverage production is that of maintaining bacterial viability throughout storage and consumption due to increased acid production resulting in a gradual decline in pH over time vis-à-vis loss in viability (Hossain et al., 2022).

Cereal and Legume Based Beverage

Cereals are a significant source of fiber, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals and have high content of oligosaccharides, carbohydrates, phenolic compounds, antioxidants, phytic acid and phytoestrogens, that can serve as prebiotic substances and encourage the growth of probiotic microbes in addition to being a significant source of nutrients (Riveria et al., 2010; Mridula et al., 2015; Salmeron., 2017).

Oat (Avena sativa L.) is rich in proteins, soluble fiber, and antioxidants, with β-glucan as a key prebiotic (Angelov et al., 2018). Oat β-glucans make up the majority of soluble fiber in oats and are widely recognized for their health benefits. Fermentation of oat enhances SCFA production, beneficial gut bacteria, antioxidant capacity, and polyphenols while improving sensory properties (Ninios et al., 2011). L. plantarum LP09 fermentation reduced the starch hydrolysis index and enhanced β-glucan (Kedia et al., 2009). As per the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), products containing β-glucans can be recommended for the regular consumption as β-glucan helps to maintain normal blood cholesterol levels (Luana et al., 2014). Funck et al (2019) have observed that oat beverages fermented with L. curvatus P99 had high probiotic viability (above 7 log CFU/mL) for 35 days when stored at 4 °C. Ghosh et al (2015) have found that rice (Oryza sativa L.) based fermented beverages, common in Asia, show strong antioxidant activity, increased enzyme (glucoamylase, α-amylase, phytase), mineral levels, and enhanced vitamin content. A probiotic rice beverage being fermentated by L. fermentum KKL1 and L. plantarum L7 had high probiotic survivility, antimicrobial potential, high amount of organic acids and minerals (Giri et al., 2015).

Maize (

Zea mays L.) is rich in starch, protein and fibres, scientists have also found that maize-fermented beverage too supports probiotic growth.

L. paracasei LBC-81 and

S. cerevisiae-fermented maize beverages maintained microbial viability (>7 log CFU/mL) at 4 °C for 28 days, producing lactic acid and other organic acids which maintained the low pH (around 4.0) that is important for the food safety, taste, and aroma of the beverages(Menezes

et al., 2012; Wacoo

et al., 2019). Freire et al (2017) have observed that rice–maize beverages fermented with

L. acidophilus LACA 4 and

L. plantarum CCMA 0743, supplemented with fructooligosaccharides (FOS), maintained probiotic levels (>10⁷ CFU/mL) at 4

oC for 28 days (after 24hrs fermentation) and showed high sensory acceptance. Ganguly

et al (2021) prepared probiotic composite beverage from whey-skim milk (60:40, v/v), germinated pearl millet flour (4.5%, w/v), liquid barley malt extract (3.0%, w/v) and fermented with

Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDC 13, had enhanced weight gain efficiency, improved protein quality, digestibility, and increased hemoglobin levels in murine model. Different probiotic starter cultures exert distinct influences on the flavor profile, sensory characteristics, and overall acceptability of the products in which they are incorporated. For instance, the presence of mild acidity, relatively high concentrations of acetaldehyde, and the inclusion of the human-derived strain

Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 8826 have been positively correlated with increased acceptability ratings of probiotic beverages formulated from barley and oats (Salmerón

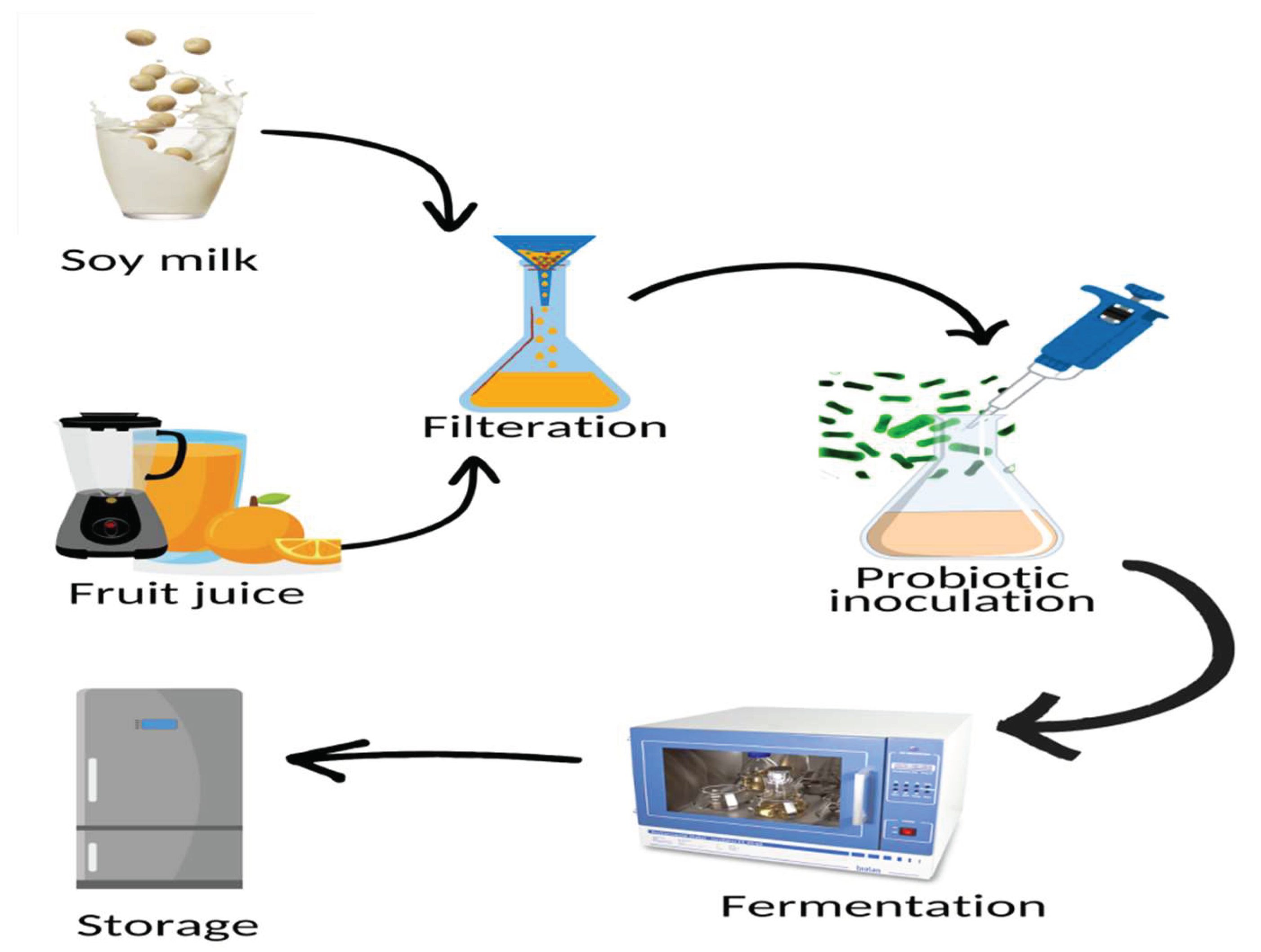

et al., 2015). The advantages and disadvantages of cereal based probiotic beverages and fruit, vegetable based probiotic beverages are summarized in

Table 3 and

Figure 2 illustrates the common procedure for preparation of non-dairy based probiotic beverages.

Drawbacks of Non-Dairy Beverages

The viability of probiotics in food products is influenced by several factors, including water activity, pH, and probiotic strain type. Among these, pH plays a critical role, particularly in fruit and vegetable juices, where high concentrations of organic acids and dissolved oxygen create a highly acidic environment that may hinder probiotic survival despite the presence of essential nutrients. Storage conditions further impact probiotic stability as these products are generally stored at room temperature, which can significantly compromise probiotic survival due to increased metabolic activity and potential thermal stress (Abu-Ghanna and Rajauria, 2015). To overcome these challenges and develop a stable non-dairy probiotic product, selection of strain and protective techniques are essential. Methods such as microencapsulation, the incorporation of prebiotic compounds, and optimizing formulation conditions can enhance probiotic survival, ensuring their retained health benefits throughout the product’s shelf life. The main characteristic features of dairy and non-dairy based probiotic beverages are described in

Figure 3.

Strategies to Improve Probiotic Survival in Fruit/Vegetable Juices

Fruit and vegetable juices contain essential nutrients, including minerals, vitamins, dietary fibers, and antioxidants. However, several critical factors can limit the survival of probiotics in juice matrices: (i) Food-related parameters: pH, titratable acidity, molecular oxygen levels, water activity, and the presence of salt, sugars, and various chemical compounds such as hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, artificial flavoring, and coloring agents; (ii) Processing parameters: heat treatment, incubation temperature, cooling rate, packaging materials, storage conditions, oxygen availability, and product volume (iii) Microbiological factors: the specific probiotic strains used, as well as the rate and proportion of inoculation (Tripathi and Giri.,2014). These factors collectively influence the viability and functionality of probiotics in juice formulations, making their consideration essential for the successful development of probiotic-enriched beverages. In order to enhance the viability of probiotics in fruit juices methods such as fortification, adaptation & induction to resistance, maintainance of storage conditions, use of antioxidants & microencapsulation techniques can be employed (Naseem et al., 2023).

Fortification with Prebiotics

Incorporating prebiotics such as dietary fibers and specific ingredients into fruit juices can bolster probiotic stability (Naseem et al., 2023). As it has been observed, enriching beetroot and carrot juices with brewer’s yeast autolysate before lactic acid fermentation with Lactobacillus acidophilus not only enhanced bacterial growth but also reduced fermentation time. Additionally, it enriched the juices with amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, thereby positively influencing probiotic survival (Rakin et al., 2007; Aspri et al., 2020).

Adaptation and Induction of Resistance

Exposing probiotics to sub-lethal stress such as mild heat, acidic pH, osmotic pressure, or oxidative stress, can induce adaptive responses that enhance their resilience (Gobetti et al., 2020). For instance, cultivating Lactobacillus reuteri in media containing red fruit juices or specific stressors prolonged its viability by several days (Bevilacqua et al., 2018). Similarly, generating acid-tolerant variants of Bifidobacterium breve through UV mutagenesis improved probiotic survival in blended juices (Saarela et al., 2021).

Storage Conditions and Use of Antioxidants

Maintaining appropriate storage temperatures is vital, as refrigeration can prolong probiotic viability, while higher temperatures may be detrimental (Sohail et al., 2012). Additionally, minimizing oxygen exposure during storage is essential, as oxygen can induce oxidative damage through reactive oxygen species (Varela-Pérez et al., 2022). Incorporating antioxidants, such as catechins from green tea extracts, has been shown to enhance the growth and survival of certain probiotic strains (Gaudreau et al., 2019). Fortifying juices with vitamin E has also been found to improve probiotic stability during storage (Gaudreau et al., 2019).

Microencapsulation Techniques

Microencapsulation involves encasing probiotic cells within protective matrices to shield them from adverse environmental conditions (Ding & Shah, 2009). Although probiotics naturally exhibit acid and bile tolerance, microencapsulation further enhances their survival by providing protection against environmental stressors, ensuring higher viability while incorporating them into food to their final destination in the human intestine (Khalil et al., 2020). Additionally, it creates an anaerobic environment for oxygen-sensitive probiotics while acting as a barrier against the high acidity of fruit juices.

Studies have demonstrated that encapsulated probiotics maintain higher viability in fruit juices compared to free cells. For instance, encapsulated Lactobacillus gasseri showed improved viability in apple juice, highlighting the protective effects of microencapsulation under simulated gastric and intestinal conditions (Varela-Pérez et al., 2022). Layer-by-layer (LbL) encapsulation is a promising method for delivering specific probiotic strains to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This approach improves probiotic survival by protecting against stomach acid and bile salts, enhancing adhesion and growth in intestinal tissues, and increasing overall survival in vivo (Anselmo et al., 2016). Therefore, implementing these strategies can significantly enhance the stability and efficacy of probiotic-fortified fruit juices, catering to the growing consumer demand for functional non-dairy beverages (Lillo-Pérez et al., 2021).

Probiotic Beverages & Human Health

Probiotics beverages play a critical role in alleviating various health conditions, including hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mental health disorders, oral health, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Valero-Cases et al., 2020). These beneficial microorganisms offer a wide range of therapeutic effects, positively influencing gut health and systemic inflammation.

Andriani et al. (2020) have shown that administration of probiotic fermented milk to male wistar rats reduced the cholesterol levels to 33.31%, compared with control rats. Angelov et al. (2006) used a probiotic starter culture with whole-grain oat substrate to create a symbiotic functional drink from the oats. The primary functional component of cereal fibers, β-glucan, is found in the highest concentration in barley and oats. According to studies, this chemical has a hypocholesterolemic action that lowers LDL cholesterol by 20–30% and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease overall, so introducing this probiotic oat beverage in our daily diet is a great option to lower cholesterol levels (Vasudha et al., 2013).

Modi et al. (2024) have demonstrated that a fermented turmeric beverage effectively reversed liver damage and lowered blood glucose levels in both alcohol induced liver damage and diabetic rat model, showing hepatoprotective effects comparable to Liv52 and hypoglycemic efficacy similar to glibenclamide. Interestingly, these scientists have also shown that fermented Amla beverage have hepatoprotective effects against chronic alcohol-induced toxicity by suppressing lipid peroxidation and elevating both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant levels in the liver.

Fermented milk exhibits antihypertensive properties, enhances immune function, lowers cholesterol levels, contributes to overall blood pressure reduction, manages irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and alleviates constipation (Tabbers et al., 2011). Hariri et al. (2015) have indicated that consuming probiotic soy milk containing Lactobacillus planetarium A7 for 8 weeks lowered blood pressure.

The impact of fermented Portulaca oleracea juice on a Caco-2 cell line have shown significantly reduced pro-inflammatory mediator levels and reactive oxygen species while preserving the integrity of Caco-2 cell monolayers exposed to inflammatory stimuli (Di Cagno et al., 2019).

In addition to benefiting gut health, fermented foods and beverages have been suggested to positively impact mental health by reducing inflammation, modulating oxidative stress associated with cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, and potentially lowering the risk of anxiety and depression (Mota et al., 2018). Cannavale et al. (2023) have indicated that consumption of a fermented dairy beverage over four weeks augmented hippocampal function and microbiota composition compared to an isocaloric control beverage in healthy young adults.

Furthermore, a commercially available probiotic beverage containing Lactobacillus casei Shirota has been shown to improve gastrointestinal parameters such as bowel movement frequency and stool consistency (Koebnik et al., 2023). Probiotic fruit-based beverages help reduce cholesterol by binding to it in the digestive system, preventing absorption and aiding its removal from the body which may support cardiovascular health and reduce disease risk (Khan et al., 2021). Mostafa et al (2020), have shown that probiotic - L. sakei fermented date juice exhibited 150–166% higher antioxidant activity than its unfermented counterpart and demonstrated greater overall acceptability during cold storage, additionaly probotic fermentation of date juice with combination of L. acidophilus and L. sakei showed even better antitumor effect against larynx cell line (Hep-2) compared with non-treated cells and control juice.

Conclusion

Probiotic beverages, a rapidly expanding segment of the functional food market, offer numerous health benefits, particularly in digestive health, immune support, and chronic disease management. Traditionally, dairy-based probiotic drinks have been consumed while non-dairy based probiotic beverages are increasingly preferred due to lactose intolerance, cholesterol concerns, and vegan dietary trends. Fermented drinks like kefir, yogurt-based beverages, kombucha, and probiotic-infused fruit juices provide diverse options to the consumers. Interestingly, emerging strategies such as microencapsulation, prebiotic fortification, and stress adaptation techniques have been able to enhance the probiotic survival in fermented beverages. With increasing awareness of gut health's role in overall well-being, the probiotic beverage industry is set for exponential growth, promising innovative, health-focused products in the near future.

Future Perspective

The future of probiotic beverages lies in the development of more stable, effective, and diverse formulations catering to varying consumer needs. No doubt, advancements in biotechnology and food processing techniques will lead to improved probiotic viability, extended shelf life, and enhanced health benefits. Further, personalized probiotic beverages, tailored to individual gut microbiome compositions, may emerge as a breakthrough in preventive healthcare. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and microbiome research could further refine probiotic recommendations for specific health conditions. As research continues to uncover the intricate connections between gut health and systemic diseases, probiotic beverages are poised to become a fundamental component of holistic nutrition and wellness. Moreover, the shift towards sustainable, plant-based alternatives will further drive innovation in non-dairy probiotic beverages, expanding accessibility and inclusivity in global markets.

Declaration of interest statement/Disclosure of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Author contribution statement

Nitika Sharma: Writing-original draft, Writing- review and editing. Siloni Patial: Writing- review and editing. Kamalakshi Sadana: Review. Geeta Shukla: Supervision, review and editing.

Acknowledgements

Department of Microbiology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India is highly acknowledged.

References

- Abd-Elsttar, H., & El Sayed, H. A. E. R. (2024). Quality Estimation of Probiotic Sesame Varieties Beverages. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry, 67(12), 485-502. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ghannam, N., & Rajauria, G. (2015). Non-dairy probiotic products. Advances in probiotic technology, 364-383.

- Ahmed, Z., Wang, Y., Ahmad, A., Khan, S. T., Nisa, M., Ahmad, H., & Afreen, A. (2013). Kefir and health: a contemporary perspective. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 53(5), 422-434.

- Andriani, R. D., Rahayu, P. P., & Apriliyani, M. W. (2020). The effect of probiotic in milk fermentation towards decreasing cholesterol levels: in vivo studies. Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Hasil Ternak (JITEK), 15(1), 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Angelov, A., Gotcheva, V., Kuncheva, R. and Hristozova, T. (2006). Development of a new oat-based probiotic drink. International Journal of Food Microbiology 112: 75–80.

- Angelov, A., Yaneva-Marinova, T., & Gotcheva, V. (2018). Oats as a matrix of choice for developing fermented functional beverages. Journal of food science and technology, 55, 2351-2360. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F., Pourjafar, H., Tabrizi, A., & Homayouni, A. (2020). The effects of probiotics and prebiotics on mental disorders: a review on depression, anxiety, Alzheimer, and autism spectrum disorders. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology, 21(7), 555-565. [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A. C., McHugh, K. J., Webster, J., Langer, R., & Jaklenec, A. (2016). Layer-by-layer encapsulation of probiotics for delivery to the microbiome. Advanced Materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.), 28(43), 9486.

- Arslan, S. (2015). A review: chemical, microbiological and nutritional characteristics of kefir. CyTA-Journal of Food, 13(3), 340-345. [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, A., Jalali, H., Azizi, M. H., & Mohammadi Nafchi, A. (2021). Production of oat bran functional probiotic beverage using Bifidobacterium lactis. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 15, 1301-1309. [CrossRef]

- Aspri, M., Papademas, P., & Tsaltas, D. (2020). Review on non-dairy probiotics and their use in non-dairy based products. Fermentation, 6(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S. S., & Panda, S. K. (2020). Ethnic and industrial probiotic foods and beverages: efficacy and acceptance. Current Opinion in Food Science, 32, 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A., Petruzzi, L., Perricone, M., Speranza, B., Campaniello, D., Sinigaglia, M., & Corbo, M. R. (2018). Nonthermal technologies for fruit and vegetable juices and beverages: Overview and advances. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17(1), 2-62. [CrossRef]

- Cannavale, C. N., Mysonhimer, A. R., Bailey, M. A., Cohen, N. J., Holscher, H. D., & Khan, N. A. (2023). Consumption of a fermented dairy beverage improves hippocampal-dependent relational memory in a randomized, controlled cross-over trial. Nutritional Neuroscience, 26(3), 265-274. [CrossRef]

- Caramia, G., Atzei, A., & Fanos, V. (2008). Probiotics and the skin. Clinics in dermatology, 26(1), 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Das, K., Choudhary, R., & Thompson-Witrick, K. A. (2019). Effects of new technology on the current manufacturing process of yogurt-to increase the overall marketability of yogurt. Lwt, 108, 69-80. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ribeiro, A. P., dos Santos Gomes, F., dos Santos, K. M. O., da Matta, V. M., de Araujo Santiago, M. C. P., Conte, C., ... & Walter, E. H. M. (2020). Development of a probiotic non-fermented blend beverage with juçara fruit: Effect of the matrix on probiotic viability and survival to the gastrointestinal tract. Lwt, 118, 108756. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., Misselwitz, B., Dai, N., & Fox, M. (2015). Lactose intolerance in adults: biological mechanism and dietary management. Nutrients, 7(9), 8020-8035. [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R., Filannino, P., Vincentini, O., Cantatore, V., Cavoski, I., & Gobbetti, M. (2019). Fermented Portulaca oleracea L. juice: A novel functional beverage with potential ameliorating effects on the intestinal inflammation and epithelial injury. Nutrients, 11(2), 248. [CrossRef]

- Ding, W. K., & Shah, N. P. (2009). Effect of various encapsulating materials on the stability of probiotic bacteria. Journal of food science, 74(2), M100-M107. [CrossRef]

- do Amaral Santos, C. C. A., da Silva Libeck, B., & Schwan, R. F. (2014). Co-culture fermentation of peanut-soy milk for the development of a novel functional beverage. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 186, 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, C., & Farnworth, E. (2000). Tea, Kombucha, and health: a review. Food research international, 33(6), 409-421.

- Fenster, K., Freeburg, B., Hollard, C., Wong, C., Rønhave Laursen, R., & Ouwehand, A. C. (2019). The production and delivery of probiotics: A review of a practical approach. Microorganisms, 7(3), 83. [CrossRef]

- Flach, J., van der Waal, M. B., van den Nieuwboer, M., Claassen, E., & Larsen, O. F. (2018). The underexposed role of food matrices in probiotic products: Reviewing the relationship between carrier matrices and product parameters. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 58(15), 2570-2584. [CrossRef]

- Freire, A. L., Ramos, C. L., & Schwan, R. F. (2017). Effect of symbiotic interaction between a fructooligosaccharide and probiotic on the kinetic fermentation and chemical profile of maize blended rice beverages. Food Research International, 100, 698-707. [CrossRef]

- Funck, G. D., Marques, J. D. L., Cruxen, C. E. D. S., Sehn, C. P., Haubert, L., Dannenberg, G. D. S., ... & Fiorentini, Â. M. (2019). Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus curvatus P99 and viability in fermented oat dairy beverage. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 43(12), e14286. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S., Sabikhi, L., & Singh, A. K. (2021). Evaluation of nutritional attributes of whey-cereal based probiotic beverage. LWT, 152, 112292. [CrossRef]

- García-Burgos, M., Moreno-Fernández, J., Alférez, M. J., Díaz-Castro, J., & López-Aliaga, I. (2020). New perspectives in fermented dairy products and their health relevance. Journal of Functional Foods, 72, 104059. [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, H., Champagne, C. P., Remondetto, G. E., Bazinet, L., & Subirade, M. (2019). Effect of green tea extracts and catechin derivatives on the survival of probiotic Lactobacillus helveticus in functional dairy products. Journal of Functional Foods, 58, 42-49.

- Ghosh, Kuntal, Mousumi Ray, Atanu Adak, Suman K. Halder, Arpan Das, Arijit Jana, Saswati Parua et al. "Role of probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum KKL1 in the preparation of a rice based fermented beverage." Bioresource technology 188 (2015): 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Giri, S. S., Sen, S. S., Saha, S., Sukumaran, V., & Park, S. C. (2018). Use of a potential probiotic, Lactobacillus plantarum L7, for the preparation of a rice-based fermented beverage. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, 473. [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, M., De Angelis, M., Di Cagno, R., & Minervini, F. (2020). Adaptation and stress response of probiotic bacteria in fruit juices. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 328, 108667.

- Gomes, I. A., Venâncio, A., Lima, J. P., & Freitas-Silva, O. (2021). Fruit-based non-dairy beverage: A new approach for probiotics. Advances in Biological Chemistry, 11(6), 302-330. [CrossRef]

- Gürakan, G. C., Cebeci, A., & Özer, B. (2009). Probiotic dairy beverages: microbiology and technology. Development and manufacture of yogurt and other functional dairy products, 165-197.

- Hariri, M., Salehi, R., Feizi, A., Mirlohi, M., Kamali, S., & Ghiasvand, R. (2015). The effect of probiotic soy milk and soy milk on anthropometric measures and blood pressure in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. ARYA atherosclerosis, 11(Suppl 1), 74.

- Hassan, A. A., Aly, M. M., & El-Hadidie, S. T. (2012). Production of cereal-based probiotic beverages. World Applied Sciences Journal, 19(10), 1367-1380.

- Hati, S., Mandal, S., & Prajapati, J. B. (2013). Novel starters for value added fermented dairy products. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal, 1(1), 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R., Merenstein, D. J., Pot, B., ... & Sanders, M. E. (2014). The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 11(8), 506-514. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. A., Das, R., Yasin, M., Kabir, H., & Ahmed, T. (2022). Potentials of two Lactobacilli in probiotic fruit juice development and evaluation of their biochemical and organoleptic stability during refrigerated storage. Scientific Study & Research. Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, Biotechnology, Food Industry, 23(2), 131-140.

- Jayabalan, R., Malbaša, R. V., Lončar, E. S., Vitas, J. S., & Sathishkumar, M. (2014). A review on kombucha tea—microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety, 13(4), 538-550. [CrossRef]

- Kandylis, P., Pissaridi, K., Bekatorou, A., Kanellaki, M., & Koutinas, A. A. (2016). Dairy and non-dairy probiotic beverages. Current Opinion in Food Science, 7, 58-63. [CrossRef]

- Kechagia, M., Basoulis, D., Konstantopoulou, S., Dimitriadi, D., Gyftopoulou, K., Skarmoutsou, N., & Fakiri, E. M. (2013). Health benefits of probiotics: a review. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013(1), 481651. [CrossRef]

- Kedia, G., Vázquez, J. A., & Pandiella, S. S. (2008). Fermentability of whole oat flour, PeriTec flour and bran by Lactobacillus plantarum. Journal of food engineering, 89(2), 246-249. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K. A. (2020). A Review on microencapsulation in improving probiotic stability for beverages application. Science Letters, 14(1), 49-61. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. M., Morya, S., & Chattu, V. K. (2021). Probiotics as a boon in Food diligence: Emphasizing the therapeutic roles of Probiotic beverages on consumers' health. Journal of Applied and Natural Science, 13(2), 700-714. [CrossRef]

- Khorshidian, N., Yousefi, M., & Mortazavian, A. M. (2020). Fermented milk: The most popular probiotic food carrier. In Advances in food and nutrition research (Vol. 94, pp. 91-114). Academic Press.

- Kim, D. H., Jeong, D., Song, K. Y., Chon, J. W., Kim, H., & Seo, K. H. (2017). Sensory profiles of Koumiss with added crude ingredients extracted from flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.). Journal of Dairy Science and Biotechnology, 35(3), 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Koebnick, C., Wagner, I., Leitzmann, P., Stern, U., & Zunft, H. F. (2003). Probiotic beverage containing Lactobacillus casei Shirota improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with chronic constipation. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(11), 655-659. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., Salminen, S., Verhagen, H., Rowland, I., Heimbach, J., Banares, S., ... & Lalonde, M. (2015). Novel probiotics and prebiotics: road to the market. Current opinion in biotechnology, 32, 99-103. [CrossRef]

- Laali, R., Pourahmad, R., & Mahdavi, R. (2018). Development of a functional beverage based on fermented coconut water with Lactobacillus plantarum and evaluation of its health benefits. Journal of Functional Foods, 40, 203-210.

- Li, Z., Teng, J., Lyu, Y., Hu, X., Zhao, Y., & Wang, M. (2018). Enhanced antioxidant activity for apple juice fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC14917. Molecules, 24(1), 51. [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Pérez, S., Guerra-Valle, M., Orellana-Palma, P., & Petzold, G. (2021). Probiotics in fruit and vegetable matrices: Opportunities for nondairy consumers. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 151, 112106. [CrossRef]

- Luana, N., Rossana, C., Curiel, J. A., Kaisa, P., Marco, G., & Rizzello, C. G. (2014). Manufacture and characterization of a yogurt-like beverage made with oat flakes fermented by selected lactic acid bacteria. International journal of food microbiology, 185, 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I., Kazakos, S., Terpou, A., Mallouchos, A., Kimbaris, A., Alexopoulos, A., ... & Plessas, S. (2018). Assessment of volatile compounds evolution, antioxidant activity, and total phenolics content during cold storage of pomegranate beverage fermented by Lactobacillus paracasei K5. Fermentation, 4(4), 95. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A. J., Hill, C., Ross, R. P., & Cotter, P. D. (2014). Fermented beverages with health-promoting potential: Past and future perspectives. Trends in food science & technology, 38(2), 113-124. [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, C., Tognon, M., Martini, F., Torreggiani, E., & Rotondo, J. C. (2023). Probiotics mechanism of action on immune cells and beneficial effects on human health. Cells, 12(1), 184. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A. G. T., Ramos, C. L., Dias, D. R., & Schwan, R. F. (2018). Combination of probiotic yeast and lactic acid bacteria as starter culture to produce maize-based beverages. Food research international, 111, 187-197. [CrossRef]

- Merkouris, E., Mavroudi, T., Miliotas, D., Tsiptsios, D., Serdari, A., Christidi, F., ... & Tsamakis, K. (2024). Probiotics’ Effects in the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression: A Comprehensive Review of 2014–2023 Clinical Trials. Microorganisms, 12(2), 411. [CrossRef]

- Meybodi, N. M., Mortazavian, A. M., Arab, M., & Nematollahi, A. (2020). Probiotic viability in yoghurt: A review of influential factors. International Dairy Journal, 109, 104793. [CrossRef]

- Modi, R., & Sahota, P. (2024). Lactic acid bacteria as an adjunct starter culture in the development of metabiotic functional turmeric (Curcuma longa Linn.) beverage. Food Science and Technology International, 30(7), 646-659. [CrossRef]

- Modi, R., Sahota, P., Singh, N. D., & Garg, M. (2023). Hepatoprotective and hypoglycemic effect of lactic acid fermented Indian Gooseberry-Amla beverage on chronic alcohol-induced liver damage and diabetes in rats. Food Hydrocolloids for Health, 4, 100155. [CrossRef]

- Moreira Terhaag, M., Sakai, O. A., Ruiz, F., Garcia, S., Bertusso, F. R., & Prudêncio, S. H. (2025). The Probiotication of a Lychee Beverage with Saccharomyces boulardii: An Alternative to Dairy-Based Probiotic Products. Foods, 14(2), 156. [CrossRef]

- Morya, S., Awuchi, C. G., Neumann, A., Napoles, J., & Kumar, D. (2022). Advancement in acidophilus milk production technology. In Advances in dairy microbial products (pp. 105-116). Woodhead Publishing.

- Mostafa, H. S., Ali, M. R., & Mohamed, R. M. (2020). Production of a novel probiotic date juice with anti-proliferative activity against Hep-2 cancer cells. Food Science and Technology, 41(suppl 1), 105-115. [CrossRef]

- Mota de Carvalho, N., Costa, E. M., Silva, S., Pimentel, L., Fernandes, T. H., & Pintado, M. E. (2018). Fermented foods and beverages in human diet and their influence on gut microbiota and health. Fermentation, 4(4), 90. [CrossRef]

- Mridula, D., & Sharma, M. (2015). Development of non-dairy probiotic drink utilizing sprouted cereals, legume and soymilk. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 62(1), 482-487. [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R., Kumar, A., & Kumar, M. (2012). Fortification and fermentation of fruit juices with probiotic lactobacilli. Annals of microbiology, 62, 1573-1578. [CrossRef]

- Naseem, Z., Mir, S. A., Wani, S. M., Rouf, M. A., Bashir, I., & Zehra, A. (2023). Probiotic-fortified fruit juices: Health benefits, challenges, and future perspectives. Nutrition, 115, 112154. [CrossRef]

- Natt, S. K., & Katyal, P. (2022). Current trends in non-dairy probiotics and their acceptance among consumers: A Review. Agricultural Reviews, 43(4), 450-456. [CrossRef]

- Ninios, A. I., Sibakov, J., Mandala, I., Fasseas, K., Poutanen, K., Nordlund, E., & Lehtinen, P. (2011). Enzymatic depolymerisation of oat beta-glucan. In Food process engineering in a changing world: Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on Engineering and Food (ICEF11) (pp. 2105-2106).

- Olson, D. W., & Aryana, K. J. (2022). Probiotic incorporation into yogurt and various novel yogurt-based products. Applied Sciences, 12(24), 12607. [CrossRef]

- Özer, B., & Kirmaci, H. A. (2010). Functional milks and dairy beverages. International Journal of Dairy Technology, 63(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. K., Kellershohn, J., & Russell, I. (Eds.). (2021). Probiotic beverages. Academic Press.

- Panghal, A., Janghu, S., Virkar, K., Gat, Y., Kumar, V., & Chhikara, N. (2018). Potential non-dairy probiotic products–A healthy approach. Food bioscience, 21, 80-89. [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Toledo, J. (2021). Roasted chickpeas as a probiotic carrier to improve L. plantarum 299v survival during storage. LWT, 146, 111471. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. L. F., Maciel, T. C., & Rodrigues, S. (2011). Probiotic beverage from cashew apple juice fermented with Lactobacillus casei. Food research international, 44(5), 1276-1283. [CrossRef]

- Prado, F. C., Parada, J. L., Pandey, A., & Soccol, C. R. (2008). Trends in non-dairy probiotic beverages. Food Research International, 41(2), 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Rafieian-Kopaei, M., Setorki, M., Doudi, M., Baradaran, A., & Nasri, H. (2014). Atherosclerosis: process, indicators, risk factors and new hopes. International journal of preventive medicine, 5(8), 927.

- Raj, T., Chandrasekhar, K., Kumar, A. N., & Kim, S. H. (2022). Recent biotechnological trends in lactic acid bacterial fermentation for food processing industries. Systems Microbiology and Biomanufacturing, 2(1), 14-40. [CrossRef]

- Rakin, M., Vukasinovic, M., Siler-Marinkovic, S., & Maksimovic, M. (2007). Contribution of lactic acid fermentation to increased antioxidant activity in vegetable juices enriched with brewer’s yeast autolysate. Food Chemistry, 100(2), 599-606. [CrossRef]

- Ranadheera, C. S., Vidanarachchi, J. K., Rocha, R. S., Cruz, A. G., & Ajlouni, S. (2017). Probiotic delivery through fermentation: Dairy vs. non-dairy beverages. Fermentation, 3(4), 67. [CrossRef]

- Reque, P. M., & Brandelli, A. (2021). Encapsulation of probiotics and nutraceuticals: Applications in functional food industry. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 114, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Espinoza, Y., & Gallardo-Navarro, Y. (2010). Non-dairy probiotic products. Food microbiology, 27(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M., Alakomi, H. L., Puhakka, A., & Mattila-Sandholm, T. (2021). Enhancing the stability of probiotic bacteria in fruit-based matrices through adaptation techniques. Food Microbiology, 95, 103699.

- Salmerón, I. (2017). Fermented cereal beverages: From probiotic, prebiotic and synbiotic towards Nanoscience designed healthy drinks. Letters in applied microbiology, 65(2), 114-124. [CrossRef]

- Salmerón, I., Thomas, K., & Pandiella, S. S. (2015). Effect of potentially probiotic lactic acid bacteria on the physicochemical composition and acceptance of fermented cereal beverages. Journal of Functional Foods, 15, 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S., Kumar, S., & Goyal, S. (2014). Maize utilisation in food bioprocessing: An overview. Maize: nutrition dynamics and novel uses, 119-134.

- Sarkar, S. (2019). Potentiality of probiotic yoghurt as a functional food–a review. Nutrition & Food Science, 49(2), 182-202. [CrossRef]

- Shangpliang, H. N. J., Rai, R., Keisam, S., Jeyaram, K., & Tamang, J. P. (2018). Bacterial community in naturally fermented milk products of Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim of India analysed by high-throughput amplicon sequencing. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1532. [CrossRef]

- Shiby, V. K., & Mishra, H. N. (2013). Fermented milks and milk products as functional foods—A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 53(5), 482-496. [CrossRef]

- Shori, A. B. (2015). The potential applications of probiotics on dairy and non-dairy foods focusing on viability during storage. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 4(4), 423-431. [CrossRef]

- Sohail, A., Turner, M. S., Coombes, A., Bostrom, T., Bhandari, B., & Hemar, Y. (2012). Effect of microencapsulation on the viability and storage stability of probiotic bacteria in fruit juices. Food Research International, 49(1), 304-311.

- Sutton, K.H. 2007. Considerations for the successful development and launch of personalised nutrigenomic foods. Mutation Research 622: 117–121. [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, S., Dsouza, J., Ragavan, M. L., & Das, N. (2018). Potential probiotic characterization and effect of encapsulation of probiotic yeast strains on survival in simulated gastrointestinal tract condition. Food Science and Biotechnology, 27, 745-753. [CrossRef]

- Tabbers, M. M., Chmielewska, A., Roseboom, M. G., Crastes, N., Perrin, C., Reitsma, J. B., ... & Benninga, M. A. (2011). Fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 in childhood constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 127(6), e1392-e1399. [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, J. E., Dallessio, J., Brunetto, J., & Ross, J. A. (2024). Anaphylaxis to cow's milk protein in a probiotic not detected by the electronic medical record. JPGN reports, 5(4), 505-507. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R., Tiwari, G., & Rai, A. (2011). Probiotic novel beverages and their applications. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 2(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M. K., & Giri, S. K. (2014). Probiotic functional foods: Survival of probiotics during processing and storage. Journal of functional foods, 9, 225-241. [CrossRef]

- Valero-Cases, E., Cerdá-Bernad, D., Pastor, J. J., & Frutos, M. J. (2020). Non-dairy fermented beverages as potential carriers to ensure probiotics, prebiotics, and bioactive compounds arrival to the gut and their health benefits. Nutrients, 12(6), 1666. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Pérez, A., Romero-Chapol, O. O., Castillo-Olmos, A. G., García, H. S., Suárez-Quiroz, M. L., Singh, J., ... & Cano-Sarmiento, C. (2022). Encapsulation of Lactobacillus gasseri: Characterization, probiotic survival, in vitro evaluation and viability in apple juice. Foods, 11(5), 740. [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T., Kandylis, P., Dimitrellou, D., Salamoura, C., Zakynthinos, G., & Proestos, C. (2018). Innovative and fortified food: Probiotics, prebiotics, GMOs, and superfood. In Preparation and processing of religious and cultural foods (pp. 67-129). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Vasudha, S., & Mishra, H. N. (2013). Non dairy probiotic beverages. International Food Research Journal, 20(1), 7.

- Villarreal-Soto, S. A., Beaufort, S., Bouajila, J., Souchard, J. P., & Taillandier, P. (2018). Understanding kombucha tea fermentation: a review. Journal of food science, 83(3), 580-588. [CrossRef]

- Wacoo, A. P., Mukisa, I. M., Meeme, R., Byakika, S., Wendiro, D., Sybesma, W., & Kort, R. (2019). Probiotic enrichment and reduction of aflatoxins in a traditional African maize-based fermented food. Nutrients, 11(2), 265. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Bao, Y., Wu, B., Lao, F., Hu, X., & Wu, J. (2019). Chemical analysis and flavor properties of blended orange, carrot, apple and Chinese jujube juice fermented by selenium-enriched probiotics. Food Chemistry, 289, 250-258. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Wittouck, S., Salvetti, E., Franz, C. M., Harris, H. M., Mattarelli, P., ... & Lebeer, S. (2020). A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology, 70(4), 2782-2858. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Lyu, F., Naumovski, N., Ajlouni, S., & Ranadheera, C. S. (2020). Functional efficacy of probiotic Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis in apple, orange and tomato juices with special reference to storage stability and in vitro gastrointestinal survival. Beverages, 6(1), 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).