Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

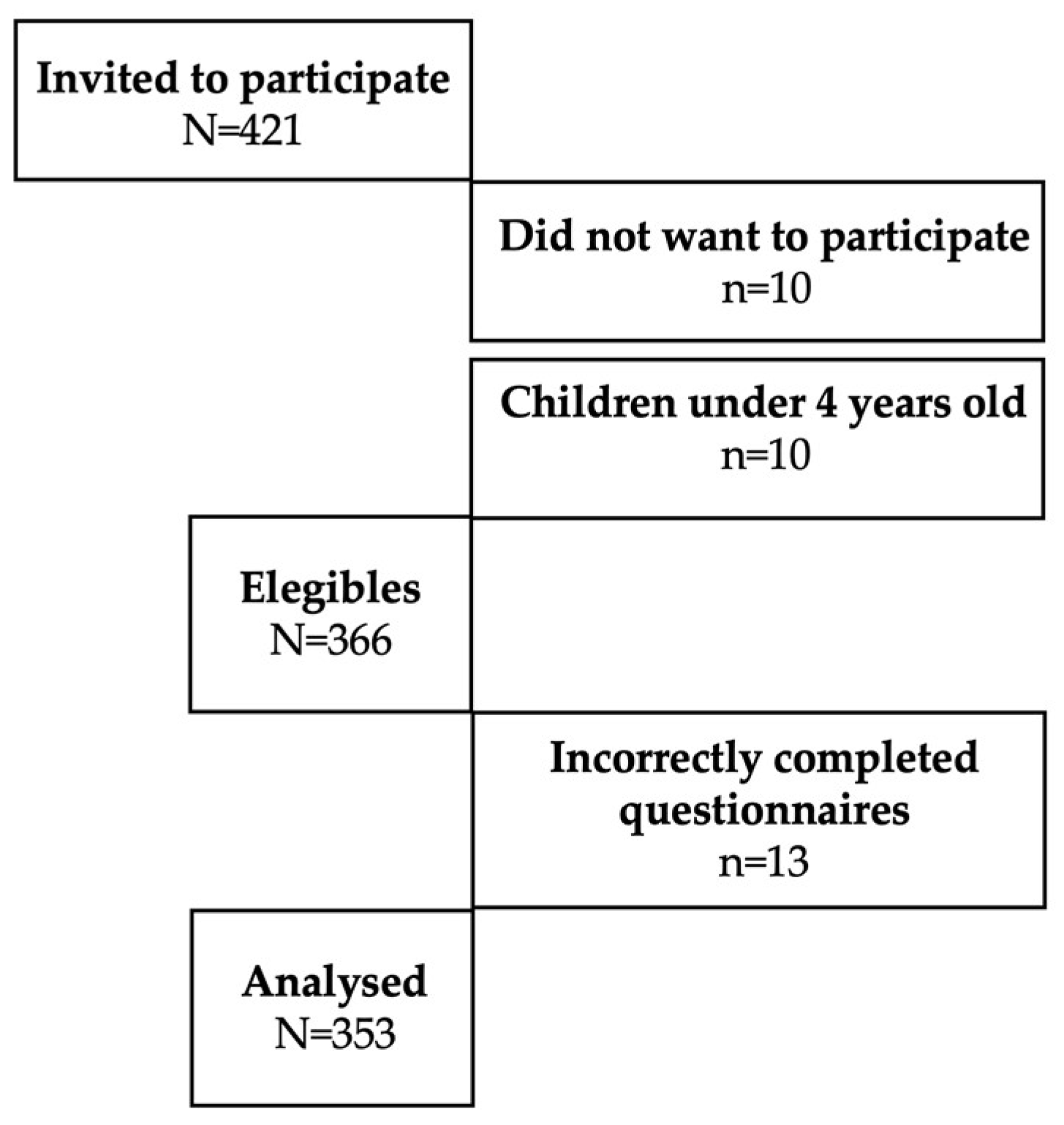

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

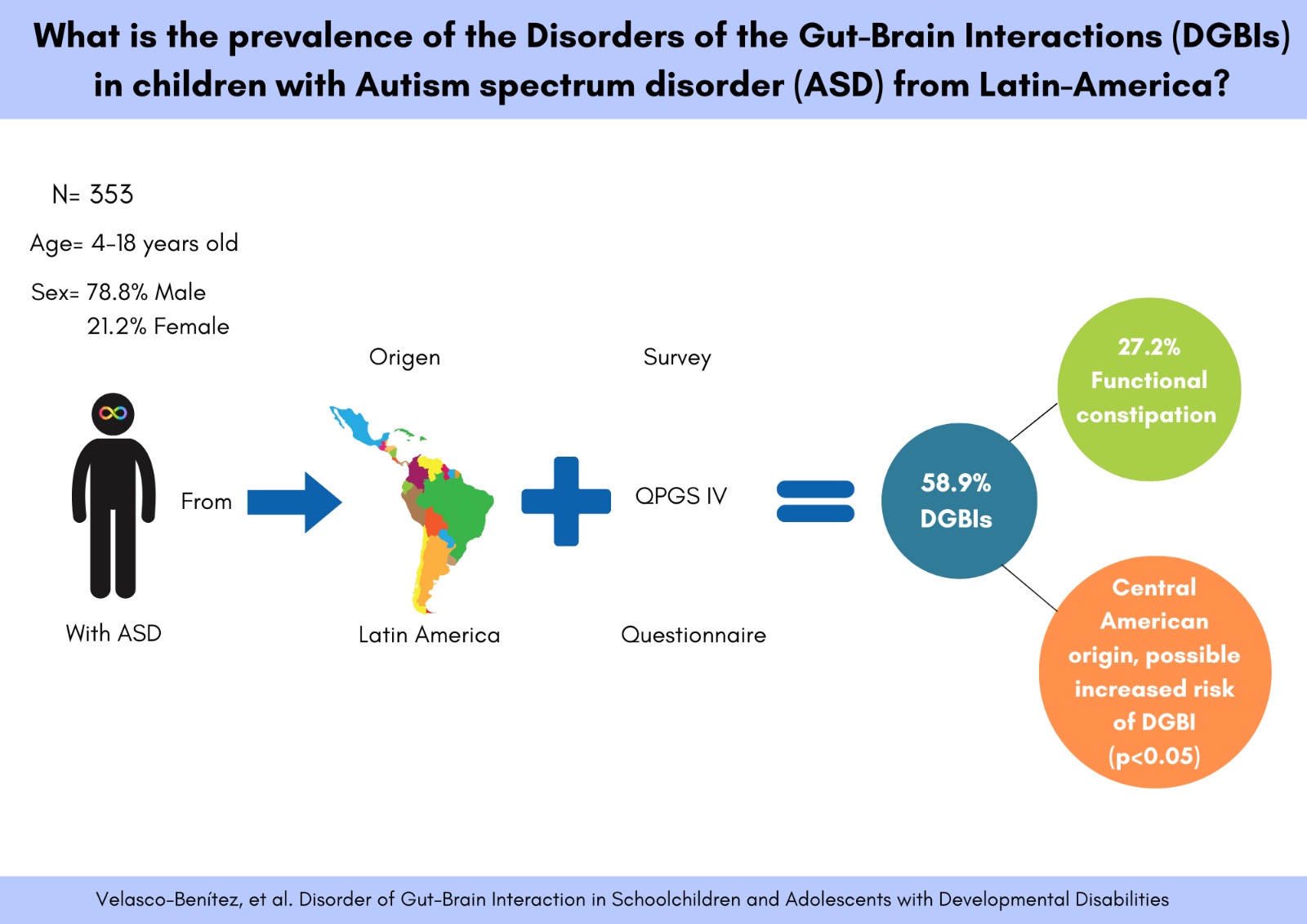

3.1. Prevalence

3.2. Possible Associations

3.3. Validation and Internal Consistency of the QPGS IV in Spanish for ASD.

3.4. Main Digestive Symptoms Identified

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGBIs | Disorders Gut-Brain Interaction |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| SA | South America |

| CA | Central America |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FC | Functional Constipation |

| QPGS IV | Questionnaire for Pediatric Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rome IV |

| FINDERS | Functional International Digestive Epidemiological Research Survey |

| DSM-V | Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| LASPGHAN | Latin America Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition |

| FD | Functional Dyspepsia |

| FAP | Functional Abdominal Pain |

References

- Kasarello, K.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Communication of gut microbiota and brain via immune and neuroendocrine signaling. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Collazos-Saa, L.I.; García-Perdomo, H.A. A systematic review and meta-analysis in schoolchildren and adolescents with functional gastrointestinal disorders according to Rome IV criteria. Arq Gastroenterol 2022, 59, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossman, D.A. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, S0016-5085, 00223-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Castellaneta, S.; De Giacomo, A.; Laguardia, M.; Schettini, F.; Francavilla, R.; Cristofori, F. Intestinal barrier dysfunction and microbiota-gut-brain axis: Possible implications in the pathogenesis and treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington 2014, United States of America.

- Lasheras, I.; Real-López, M.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2023, 99, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.T.; Jin, D.-M.; Mills, R.H.; Shao, Y.; Rahman, G.; McDonald, D.; Zhu, Q.; Balaban, M.; Jiang, Y.; Cantrell, K.; et al. Multi-level analysis of the gut-brain axis shows autism spectrum disorder-associated molecular and microbial profiles. Nat Neurosci 2023, 26, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Ortíz-Rivera, C.J.; Sánchez-Pérez, M.P.; Játiva-Mariño, E.; Villamarín-Betancourt, E.A.; Saps, M. Utilidad de los cuestionarios de Roma IV en español para identificar desórdenes gastrointestinales funcionales en pediatría. Grupo de trabajo de la Sociedad Latinoamericana de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (SLAGHNP). Acta Gastroenterológica Latinoamericana 2019, 49, 259–296. [Google Scholar]

- Saps, M.; Nichols-Vinueza, D.X.; Mintjens, S.; Pusatcioglu, C.K.; Velasco-Benítez, C.A. Construct validity of the pediatric Rome III criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014, 59, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.M. Research Design and Methods; Elsevier Inc.: Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 419–429. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, E.Y. A neurodidactic model for teaching elementary EFL students in a college context. English Lang. Teach. 2021, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaleman, D.F.; Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Méndez-Guzmán, L.M.; Benninga, M.A.; Saps, M. Can we rely on the Rome IV questionnaire to diagnose children with functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Benítez, C. Trastornos Digestivos Funcionales En Pediatría, 1st ed.; Grupo Distribuna: Bogota, Colombia, 2022; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, S.G.; Keller, C.; Zwiener, R.; Hyman, P.E.; Nurko, S.; Saps, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Shulman, R.J.; Hyams, J.S.; Palsson, O.; et al. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the Rome IV criteria. J Pediatr 2018, 195, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selimović, A.; Mekić, N.; Terzić, S.; Ćosićkić, A.; Zulić, E.; Mehmedović, M. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: A single centre experience. Med Glas (Zenica) 2024, 21, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenni, S.; Pensabene, L.; Dolce, P.; Campanozzi, A.; Salvatore, S.; Pujia, R.; Serra, M.R.; Scarpato, E.; Miele, E.; Staiano, A.; et al. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in Italian children living in different regions: Analysis of the difference and the role of diet. Dig Liver Dis 2023, 55, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, Ö.G.; Baykara, H.B.; Akın, K.; Kahveci, S.; Şeker, G.; Güler, Y.; Öztürk, Y. Evaluation of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children aged 4-10 years with autism spectrum disorder. Turk J Pediatr 2024, 66, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurman, V.; Margolis, K.G.; Luna, R.A. Autism spectrum disorder as a brain-gut-microbiome axis disorder. Dig Dis Sci 2020, 65, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, R.M.P.; Machado, N.C.; Carvalho, M.A.; Graffunder, J.S.; Ortolan, E.V.P.; Lourenção, P.L.T.A. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in children and adolescents with functional constipation: A protocol for an interventional study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.T.; Song, J.M.; Qiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Weng, E.H.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation with pelvic floor exercises in the treatment of childhood constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2023, 118, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Nurko, S.; Hyams, J.S.; Rodriguez-Araujo, G.; Almansa, C.; Shakhnovich, V.; Saps, M.; Simon, M. Randomized controlled trial of linaclotide in children aged 6-17 years with functional constipation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Robert, J.; Rodriguez-Araujo, G.; Shakhnovich, V.; Xie, W.; Nurko, S.; Saps, M. Safety and efficacy of linaclotide in children aged 2-5 years with functional constipation: Phase 2, randomized study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 79, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Khlevner, J.; Rodriguez-Araujo, G.; Xie, W.; Huh, S.Y.; Ando, M.; Hyams, J.S.; Nurko, S.; Benninga, M.A.; Simon, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of linaclotide in treating functional constipation in paediatric patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 9, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.N.; Zhang, K.; Xiong, Y.Y.; Liu, S. The relationship between functional constipation and overweight/obesity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Res 2023, 94, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppen, I.J.N.; Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Benninga, M.A.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Saps, M. Is there an association between functional constipation and excessive bodyweight in children? J. Pediatr. 2016, 171, 178–182.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.; Hepsibah, P.E.V.; Niharika, M.K. Quality of life in parents of children with Autism spectrum disorder: Emphasizing challenges in the Indian context. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 69, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, A.; Manari, T.; Dioni, B.; Raffin, C.; Bravo, G.; Mariani, R.; Esposito, G.; Dimitriou, D.; Plazzi, G.; Franceschini, C.; et al. Parental Quality of Life and Involvement in Intervention for Children or Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodakis, J. An n=1 case report of a child with autism improving on antibiotics and a father's quest to understand what it may mean. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2015, 26, 26382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Vázquez, L.; Van Ginkel Riba, G.; Arija, V.; Canals, J. Composition of gut microbiota in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Zhu, M.; Fu, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, M.; Lou, X.; et al. A comparison between children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and healthy controls in biomedical factors, trace elements, and microbiota biomarkers: A meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1318637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, M.R.; Kain, J.N.; Chen, S.Y.; Kalanetra, K.; Lemay, D.G.; Rose, D.R.; Yang, H.T.; Tancredi, D.J.; German, J.B.; Slupsky, C.M.; et al. Pilot study of probiotic/colostrum supplementation on gut function in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patusco, R.; Ziegler, J. Role of probiotics in managing gastrointestinal dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorder: An update for practitioners. Adv Nutr 2018, 9, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossaji, Z.; Khattak, A.; Tun, K.M.; Hsu, M.; Batra, K.; Hong, A.S. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant on behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms in pediatric autism: A systematic review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F. The next generation fecal microbiota transplantation: To transplant bacteria or virome. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023, 10, e2301097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.Y.C.; Leung, P.W.L.; Hung, S.F.; Shea, C.K.S.; Mo, F.; Che, K.K.I.; Tse, C.Y.; Lau, F.L.F.; Ma, S.L.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Gastrointestinal problems in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2020, 16, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Su, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, G.; Lai, C.; Lv, Y.; Li, Y. Questionnaire-based analysis of autism spectrum disorders and gastrointestinal symptoms in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr 2023, 11, 1120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, B.; Angkustsiri, K.; Taylor, S.L.; Rogers, S.J.; Cabral, J.; Heath, B.; Hechtman, A.; Solomon, M.; Ashwood, P.; Amaral, D.G.; et al. Developmental-behavioral profiles in children with autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring gastrointestinal symptoms. Autism Res. 2020, 1, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holingue, C.; Poku, O.; Pfeiffer, D.; Murray, S.; Fallin, M.D. Gastrointestinal concerns in children with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative study of family experiences. Autism 2022, 26, 1698–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holingue, C.; Kalb, L.G.; Musci, R.; Lukens, C.; Lee, L.-C.; Kaczaniuk, J.; Landrum, M.; Buie, T.; Fallin, M.D. Characteristics of the autism spectrum disorder gastrointestinal and related behaviors inventory in children. Autism Res 2022, 15, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, L.G.; Curtin, C.; Phillips, S.; Anderson, S.E.; Maslin, M.; Must, A. Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2017, 47, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

All (N=353) |

4-10 Years old (n=242) |

11-18 Years old (n=111) |

|

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean SD | 9.0+/-3.7 | 6.8+/-1.8 | 13.7+/-2.4 |

| Range | 4-18 | 4-10 | 11-18 |

| Age groups (years) | |||

| Schoolchildren (8-12) | 290 (82.2) | 242 (100.0) | 48 (43.2) |

| Adolescents (13-18) | 63 (17.8) | 0 (0.0) | 63 (56.8) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 75 (21.3) | 47 (19.4) | 28 (25.2) |

| Male | 278 (78.8) | 195 (80.6) | 83 (74.8) |

| Race | |||

| White | 198 (56.1) | 132 (54.5) | 66 (59.5) |

| Mixed | 144 (40.8) | 100 (41.3) | 44 (39.6) |

| Afro-descendant | 7 (2.0) | 7 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Indigenous | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.9) |

| Country | |||

| South America | 148 (41.9) | 102 (42.1) | 46 (41.4) |

| Argentina | 82 (23.2) | 61 (25.2) | 21 (18.9) |

| Colombia | 66 (18.7) | 41 (16.9) | 25 (22.5) |

| Central America | 205 (58.1) | 140 (57.9) | 65 (58.6) |

| Costa Rica | 52 (14.7) | 33 (13.6) | 19 (17.1) |

| El Salvador | 47 (13.3) | 39 (16.1) | 8 (7.2) |

| Mexico | 50 (14.2) | 30 (12.4) | 20 (18.0) |

| Panama | 56 (15.9) | 38 (15.7) | 18 (16.2) |

| School (n=328) | (n=328) | (n=223) | (n=105) |

| Public | 48 (14.6) | 31 (13.9) | 17 (16.2) |

| Private | 280 (85.4) | 192 (86.1) | 88 (83.8) |

|

All (N=353) |

4-10 Years old (n=242) |

11-18 Years old (n=111) |

p | |

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Caesarean section | ||||

| No | 150 (42.5) | 98 (40.5) | 52 (46.9) | 0.158 |

| Yes | 203 (57.5) | 144 (59.5) | 59 (53.1) | |

| Prematurity | ||||

| No | 292 (82.7) | 202 (83.5) | 90 (81.1) | 0.341 |

| Yes | 61 (17.3) | 40 (16.5) | 21 (18.9) | |

| Level of autism | ||||

| Level I | (n=180) | (n=122) | (n=58) | |

| No | 99 (55.0) | 67 (54.9) | 32 (55.2) | 0.552 |

| Yes | 81 (45.0) | 55 (45.1) | 26 (44.8) | |

| Level II | (n=180) | (n=122) | (n=58) | |

| No | 110 (61.1) | 74 (60.7) | 36 (62.1) | 0.494 |

| Yes | 70 (38.9) | 48 (39.3) | 22 (37.9) | |

| Level III | (n=180) | (n=122) | (n=58) | |

| No | 151 (83.9) | 103 (84.4) | 48 (82.8) | 0.466 |

| Yes | 29 (16.1) | 19 (15.6) | 10 (17.2) | |

| Nutritional status | ||||

| According to Body Mass Index | ||||

|

Normal |

(n=318) 187 (58.8) |

(n=228) 135 (59.2) |

(n=90) 52 (57.8) |

0.456 |

| Malnutrition | 131 (41.2) | 93 (40.8) | 38 (57.8) | |

| According to Height for age | ||||

|

Normal |

(n=320) 274 (85.6) |

(n=228) 196 (86.0) |

(n=92) 78 (84.8) |

0.469 |

| Height altered | 46 (14.4) | 32 (14.0) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| No | 268 (75.9) | 188 (77.7) | 80 (72.1) | 0.156 |

| Yes | 85 (24.1) | 54 (22.3) | 31 (27.9) | |

| Family variables | ||||

| Only child | ||||

| No | 238 (67.4) | 158 (65.3) | 80 (72.1) | 0.127 |

| Yes | 115 (32.6) | 84 (34.7) | 31 (27.9) | |

| Firstborn | ||||

| No | 160 (45.3) | 113 (46.7) | 47 (42.3) | 0.259 |

| Yes | 193 (54.7) | 129 (53.3) | 64 (57.7) | |

| Separated/divorced parents | ||||

| No | 261 (73.9) | 193 (79.8) | 68 (61.3) |

0.000 |

| Yes | 92 (26.1) | 49 (20.2) | 43 (38.7) | |

| DGBIs intra-family | ||||

| No | 339 (96.0) | 232 (95.9) | 107 (96.4) | 0.536 |

| Yes | 14 (4.0) | 10 (4.1) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Autism in the family | ||||

| No | 335 (94.9) | 230 (95.0) | 105 (94.6) | 0.521 |

| Yes | 18 (5.1) | 12 (5.0) | 6 (5.4) | |

|

All (N=353) |

4-10 Years old (n=242) |

11-18 Years old (n=111) |

|

| DGBIs | |||

| No | 145 (41.1) | 99 (40.9) | 46 (41.4) |

| Yes | 208 (58.9) | 143 (59.1) | 65 (58.6) |

| Associated with nausea and vomiting | 10 (2.9) | 6 (2.4) | 4 (3.6) |

| Functional vomiting | 6 (1.7) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (3.6) |

| Cyclic vomiting | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Rumination | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Aerophagia | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Associated with abdominal pain | 100 (28.3) | 69 (28.5) | 31 (27.9) |

| Functional dyspepsia | 77 (21.8) | 55 (22.7) | 22 (19.8) |

| Postprandial | 74 (21.0) | 53 (21.9) | 21 (18.9) |

| Epigastric | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 5 (1.4) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| IBS with diarrhea | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| IBS with constipation | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Abdominal migraine | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Functional abdominal pain not otherwise specified | 16 (4.5) | 8 (3.3) | 8 (7.2) |

| Associated with defecation | 98 (27.8) | 68 (28.1) | 30 (27.0) |

| Functional constipation | 96 (27.2) | 67 (27.7) | 29 (26.1) |

| Non-retentive faecal incontinence | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| DGBIs |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

DGBIs |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||

| Sociodemographic variables | Clinical variables | ||||||||||

| Age groups | Caesarean section | ||||||||||

| Schoolchildren | 120 (82.8) | 170 (81.7) | 1.00 |

0.8040 |

No | 58 (40.0) | 92 (44.2) | 1.00 |

0.4289 |

||

| Adolescents | 25 (17.2) | 38 (18.3) | 1.07 | 0.59-1.95 | Yes | 87 (60.0) | 116 (55.8) | 0.84 | 0.53-1.32 | ||

| Sex | Prematurity | ||||||||||

| Female | 31 (21.4) | 44 (21.2) | 1.00 |

0.9594 |

No | 118 (81.4) | 174 (83.7) | 1.00 |

0.5782 |

||

| Male | 114 (78.6) | 164 (78.8) | 1.01 | 0.58-1.75 | Yes | 27 (18.6) | 34 (16.4) | 0.85 | 0.47-1.55 | ||

| Race | Level of autism (n=180) | ||||||||||

| White | Level I | (n=65) | (n=115) | ||||||||

| No | 64 (44.1) | 91 (43.8) | 1.00 |

0.9424 |

No | 37 (56.9) | 62 (53.9) | 1.00 |

0.6966 |

||

| Yes | 81 (55.9) | 117 (56.2) | 1.01 | 0.64-1.59 | Yes | 28 (43.1) | 53 (46.1) | 1.12 | 0.58-2.18 | ||

| Mixed | Level II | (n=65) | (n=115) | ||||||||

| No | 91 (62.8) | 118 (56.7) | 1.00 |

0.2569 |

No | 39 (60.0) | 71 (61.7) | 1.00 |

0.8182 |

||

| Yes | 54 (37.2) | 90 (43.3) | 1.28 | 0.81-2.03 | Yes | 26 (40.0) | 44 (38.3) | 0.92 | 0.47-1.82 | ||

| Afro-descendant | Level III | (n=65) | (n=115) | ||||||||

| No | 138 (95.2) | 208 (100.0) | n/a | No | 54 (83.1) | 97 (84.4) | 1.00 |

0.8237 |

|||

| Yes | 7 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | Yes | 11 (16.9) | 18 (15.6) | 0.91 | 0.37-2.30 | ||||

| Indigenous | Nutritional status | ||||||||||

| No | 142 (97.9) | 207 (99.5) | 1.00 |

0.1655 |

According to Body Mass Index | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.22 | 0.004-2.89 | Normal |

(n=132) 53 (40.2) |

(n=186) 78 (41.9) |

1.00 |

0.7501 |

||

| School (n=328) | (n=134) | (n=194) | Malnutrition | 79 (59.8) | 108 (58.1) | 0.92 | 0.57-1.49 | ||||

| Public | 23 (17.2) | 25 (12.9) | 1.00 |

0.2813 |

According to Height for age | ||||||

| Private | 111 (82.8) | 169 (87.1) | 1.40 | 0.71-2.71 | Normal |

(n=134) 18 (13.4) |

(n=186) 28 (15.1) |

1.00 |

0.6835 |

||

| Origin | Altered H/A | 116 (86.6) | 158 (84.9) | 0.87 | 0.43-1.73 | ||||||

| South America | Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| No | 70 (48.3) | 135 (64.9) | 1.00 |

0.0018 |

No | 112 (77.2) | 156 (75.0) | 1.00 |

0.6280 |

||

| Yes | 75 (51.7) | 73 (35.1) | 0.50 | 0.31-0.79 | Yes | 33 (22.8) | 52 (25.0) | 1.13 | 0.66-1.93 | ||

| Argentina | Family variables | ||||||||||

| No | 110 (75.9) | 161 (77.4) | 1.00 |

0.7358 |

Only child | ||||||

| Yes | 35 (24.1) | 47 (22.6) | 0.91 | 0.54-1.56 | No | 97 (66.9) | 141 (67.8) | 1.00 |

0.8604 |

||

| Colombia | Yes | 48 (33.1) | 67 (32.2) | 0.96 | 0.59-1.55 | ||||||

| No | 105 (72.4) | 182 (87.5) | 1.00 |

0.0003 |

Firstborn | ||||||

| Yes | 40 (27.6) | 26 (12.5) | 0.37 | 0.20-0.67 | No | 67 (46.2) | 93 (44.7) | 1.00 |

0.7813 |

||

| Central America | Yes | 78 (53.8) | 115 (55.3) | 1.06 | 0.67-1.66 | ||||||

| No | 75 (51.7) | 73 (35.1) | 1.00 |

0.0018 |

Separated/divorced parents | ||||||

| Yes | 70 (48.3) | 135 (64.9) | 1.98 | 1.25-3.12 | No | 110 (75.9) | 151 (72.6) | 1.00 |

0.4916 |

||

| Panama | Yes | 35 (24.1) | 57 (27.4) | 1.18 | 0.70-1.99 | ||||||

| No | 126 (86.9) | 171 (82.2) | 1.00 |

0.2359 |

DGBIs intra-familiar | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (13.1) | 37 (17.8) | 1.43 | 0.76-2.77 | No | 142 (97.9) | 197 (94.7) | 1.00 |

0.1273 |

||

| El Salvador | Yes | 3 (2.1) | 11 (5.3) | 2.64 | 0.67-14.98 | ||||||

| No | 123 (84.3) | 183 (88.0) | 1.00 |

0.3909 |

Familial autism | ||||||

| Yes | 22 (15.2) | 25 (12.0) | 0.76 | 0.39-1.49 | No | 138 (95.2) | 197 (94.7) | 1.00 |

0.8464 |

||

| Costa Rica | Yes | 7 (4.8) | 11 (5.3) | 1.10 | 0.37-3.43 | ||||||

| No | 130 (89.7) | 171 (82.2) | 1.00 |

0.0522 |

|||||||

| Yes | 15 (10.3) | 37 (17.8) | 1.87 | 0.95-3.83 | |||||||

| Mexico | |||||||||||

| No | 131 (90.3) | 172 (82.7) | 1.00 |

0.0425 |

|||||||

| Yes | 14 (9.7) | 36 (17.3) | 1.95 | 0.98-4.09 | |||||||

| Alpha de Cronbach | Interpretation | |

| Total questionnaire | 0.7818 | High |

| Section A | 0.7331 | High |

| Section B | 0.4706 | Moderate |

| Section C | 0.6535 | High |

| Section D | 0.6110 | High |

| Section E | 0.6367 | High |

| Symptom | n (%) |

| Flatus | 178 (50.4) |

| Painful Stool | 126 (35.7) |

| Large stools | 108 (30.6) |

| History of large fecal mass in rectum | 94 (26.6) |

| Hard stools | 84 (23.8) |

| Belching | 84 (23.8) |

| Stool Retention | 78 (22.1) |

| Soiling | 73 (20.7) |

| Abdominal pain around and below belly button | 68 (19.3) |

| Early satiation | 66 (18.7) |

| Abdominal pain above belly button | 53 (15.0) |

| Abdominal distention | 48 (13.6) |

| Watery stools | 28 (7.9) |

| Swallowing air | 26 (7.4) |

| Nausea | 25 (7.1) |

| Heartburn | 16 (4.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).