Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

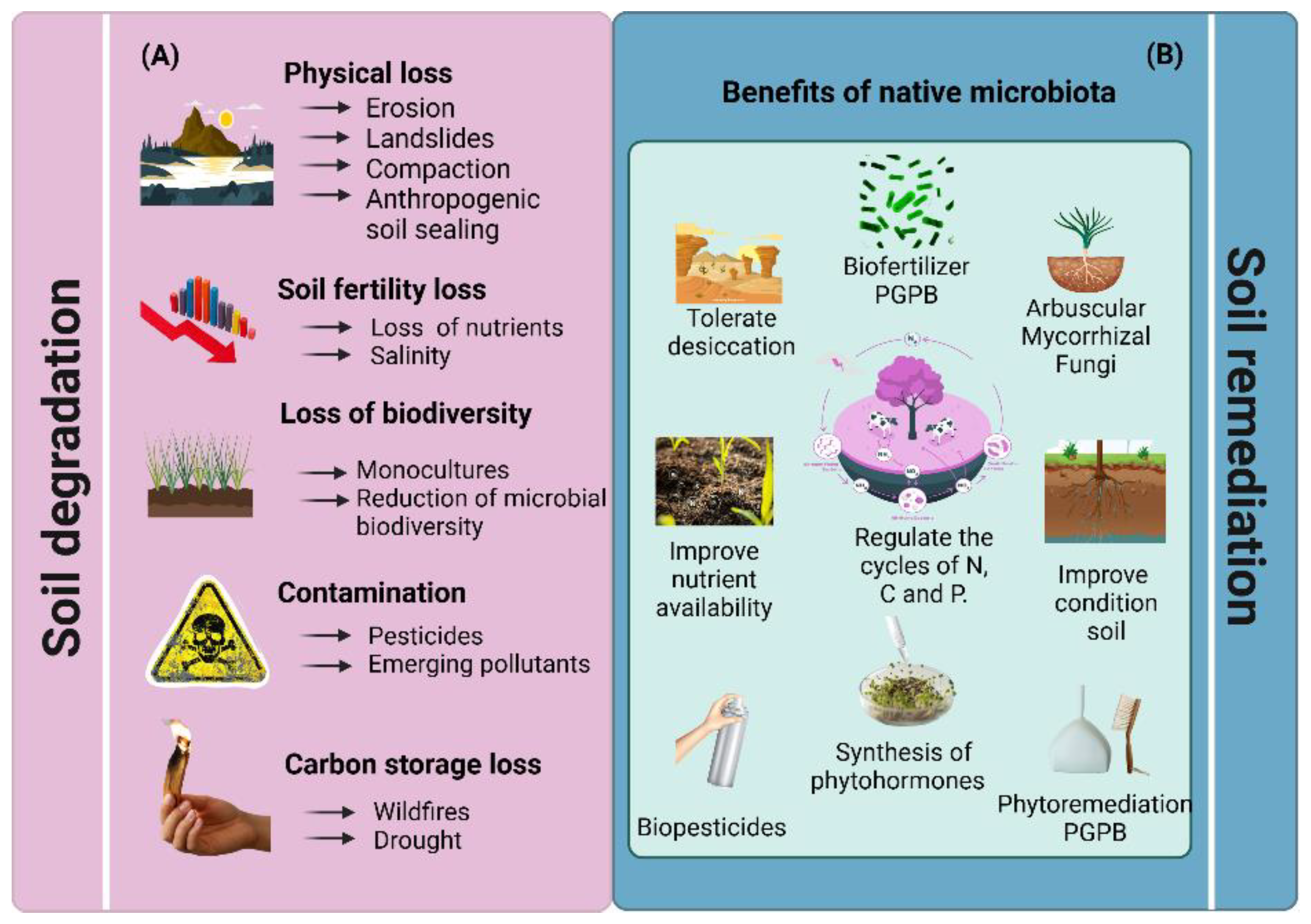

1. Soil Degradation Challenges Stemming from Excessive Agricultural Cultivation.

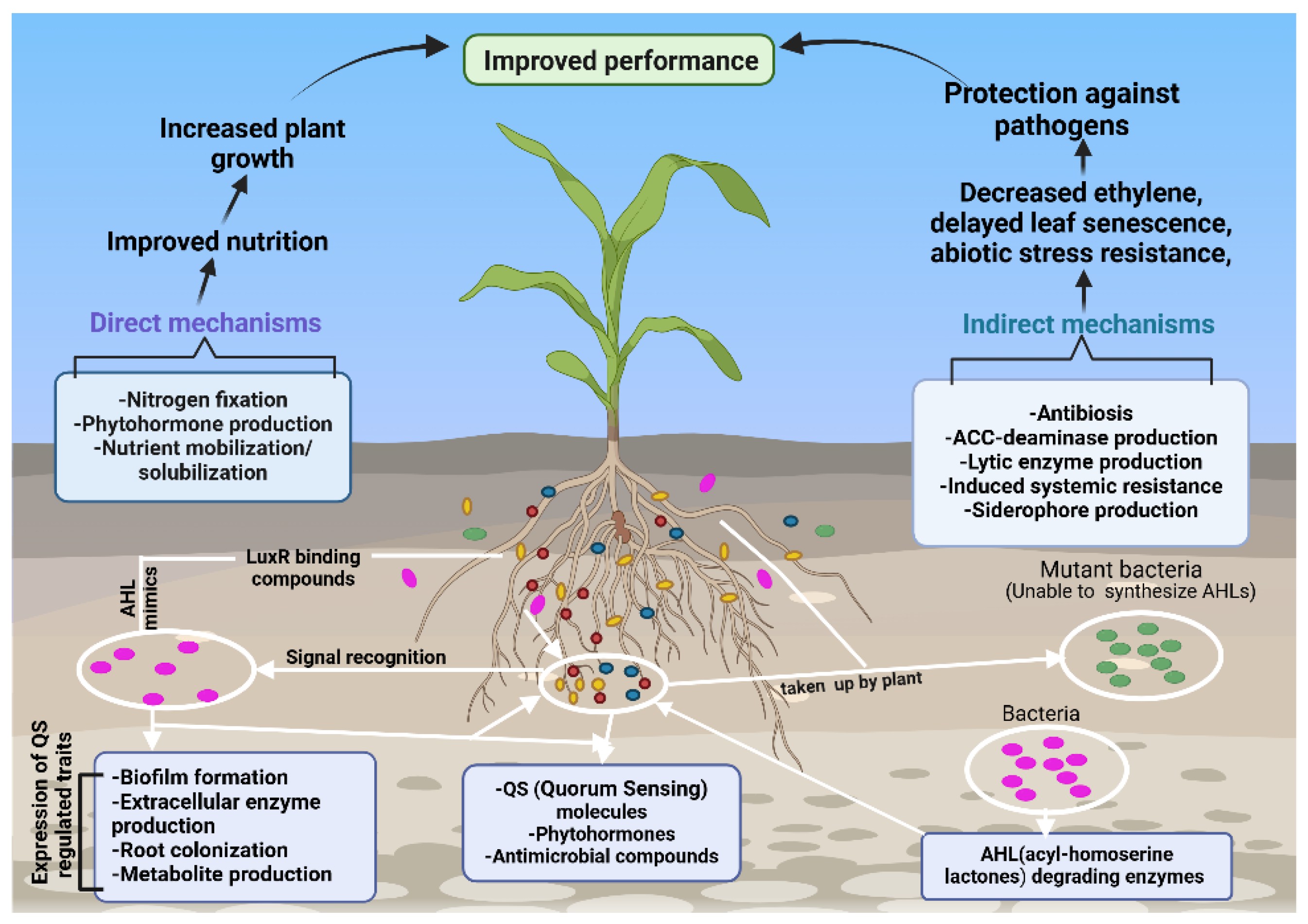

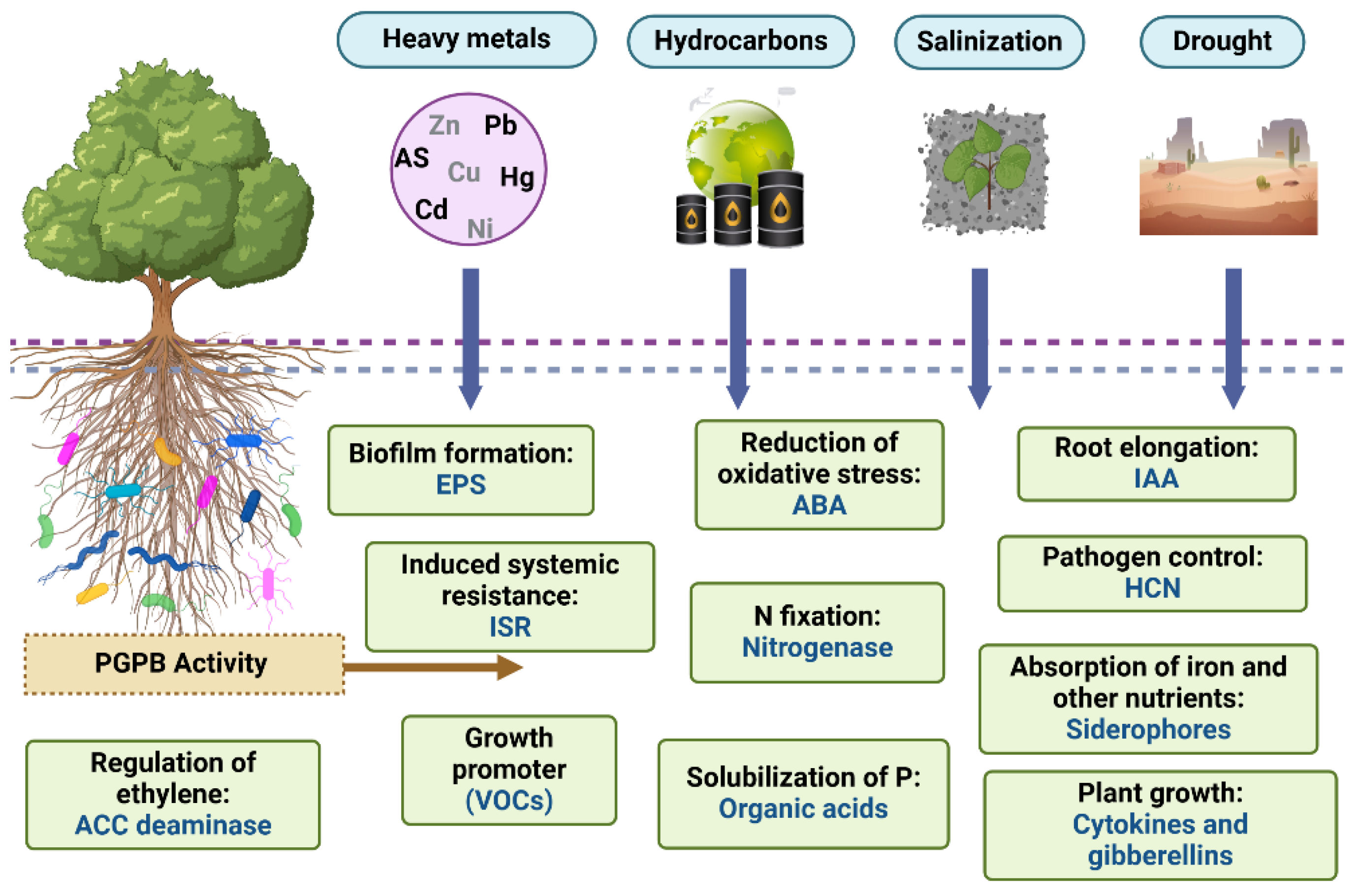

2. Direct and Indirect Mechanisms of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria

2.1. Indirect Mechanisms

2.1.1. Siderophores Production

2.1.2. Enzymatic Mechanisms in Indirect Plant Defense.

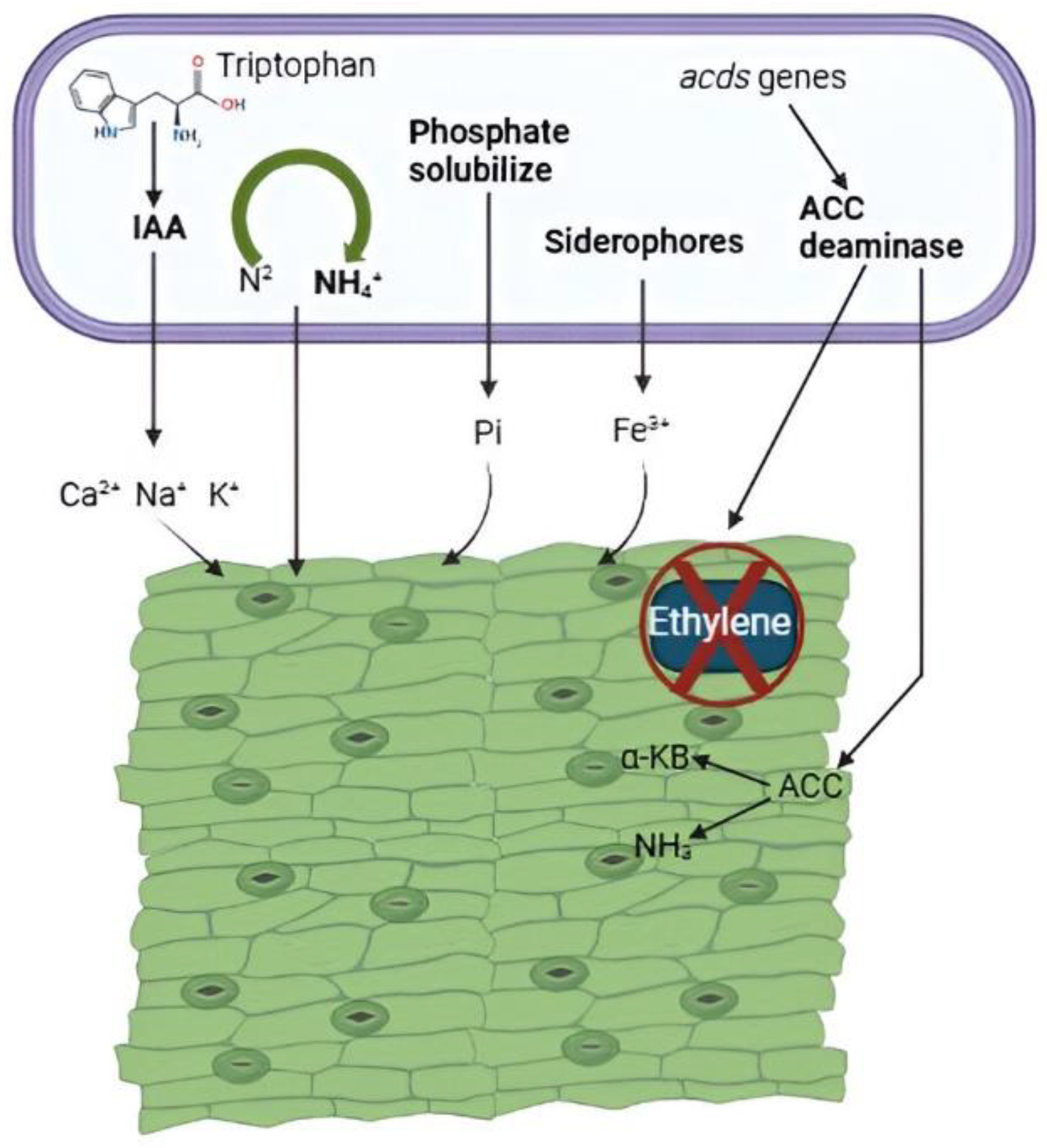

2.2. Direct Mechanisms

2.2.1. Plant Growth Regulators and Their Role in Plant Growth and Signaling

2.2.2. Contribution of Microbial Activity to Nutrient Solubilization and Plant Growth.

3. Physiological Mechanisms of Plant-Microorganism Interaction

3.1. Bacterial Contribution to Plant Nutrient Acquisition

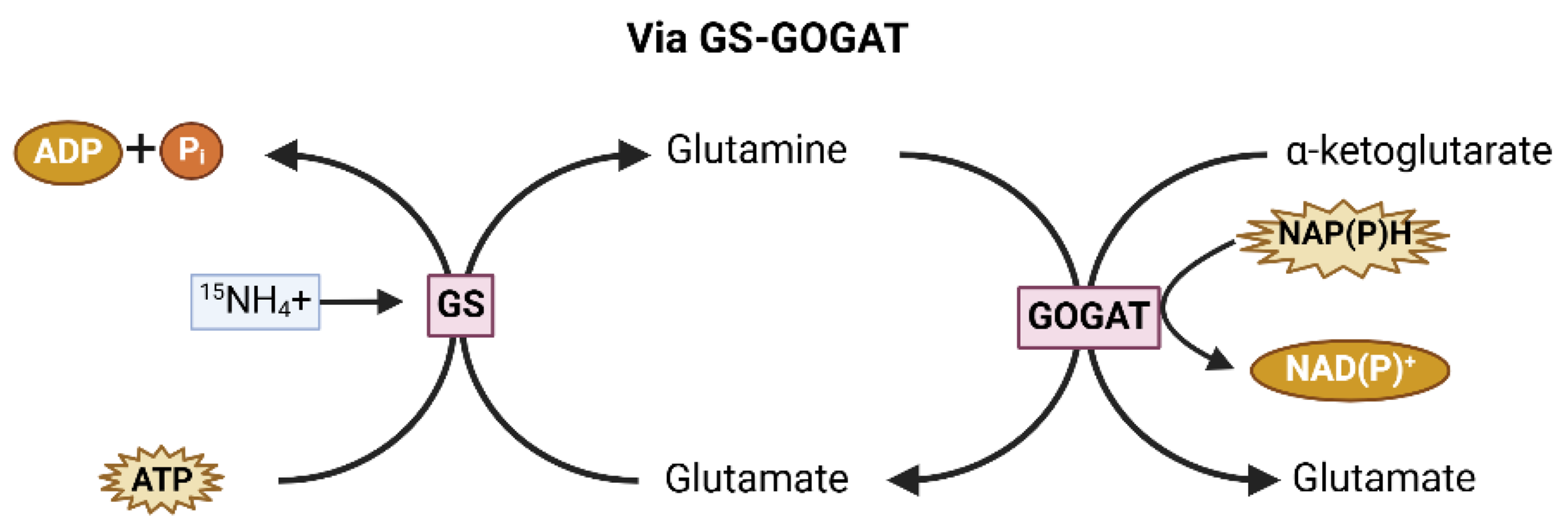

3.1.1. Nitrogen

3.1.2. Phosphorus

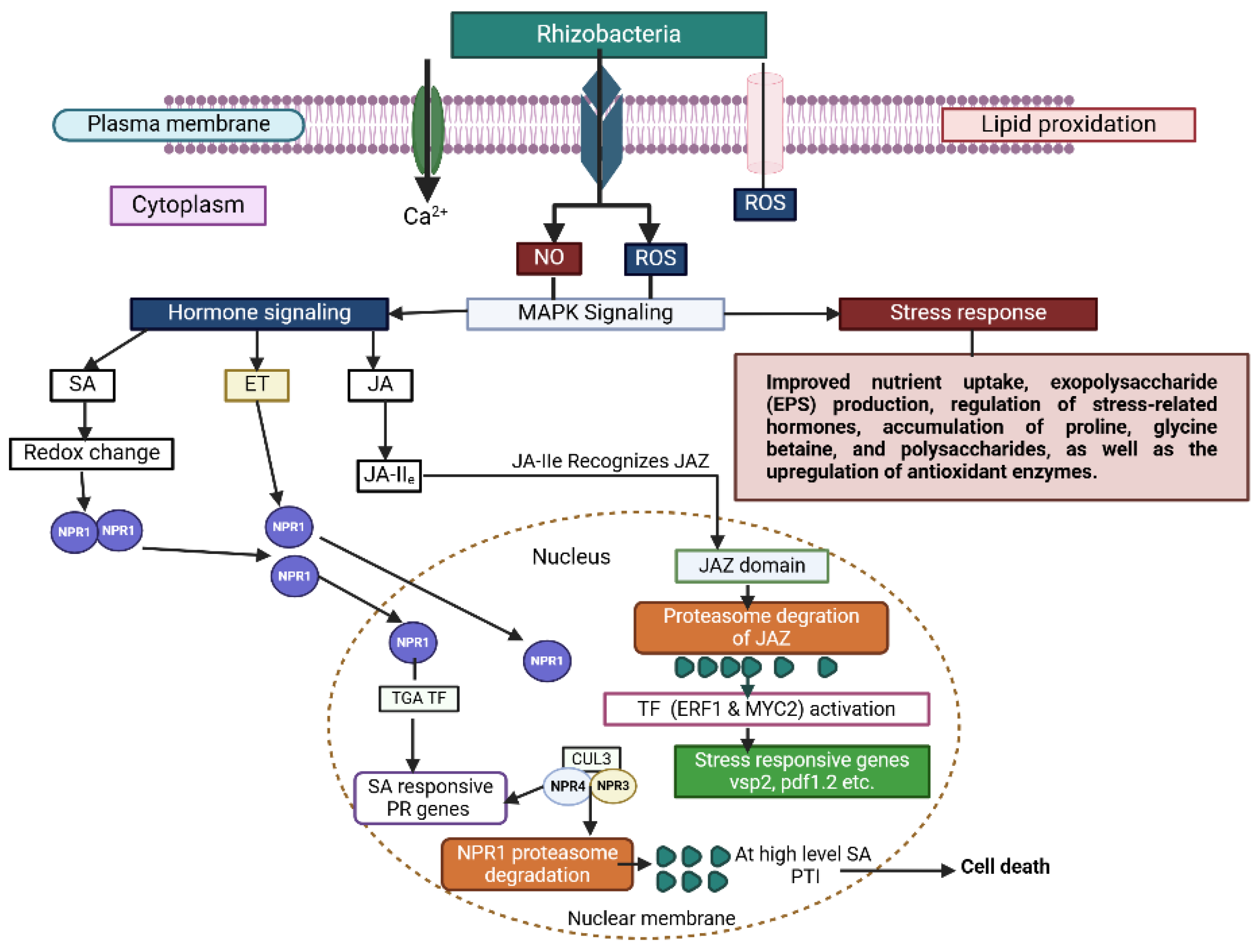

3.2. Bacterial Modulation of Plant Hormonal Pathways and Signaling Mechanisms

3.2.1. Plant Growth Regulators

3.2.2. Volatile Organic Compounds

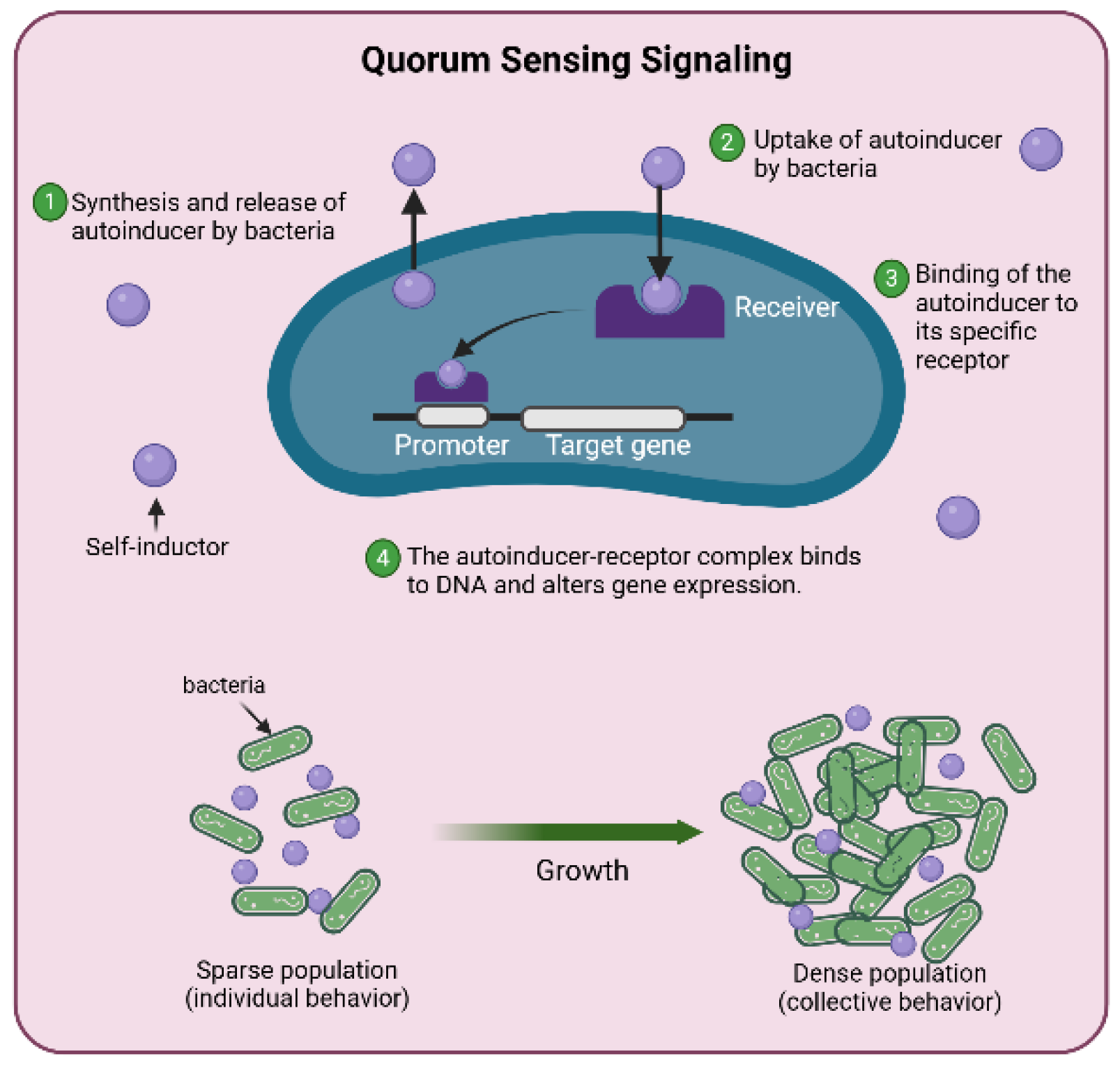

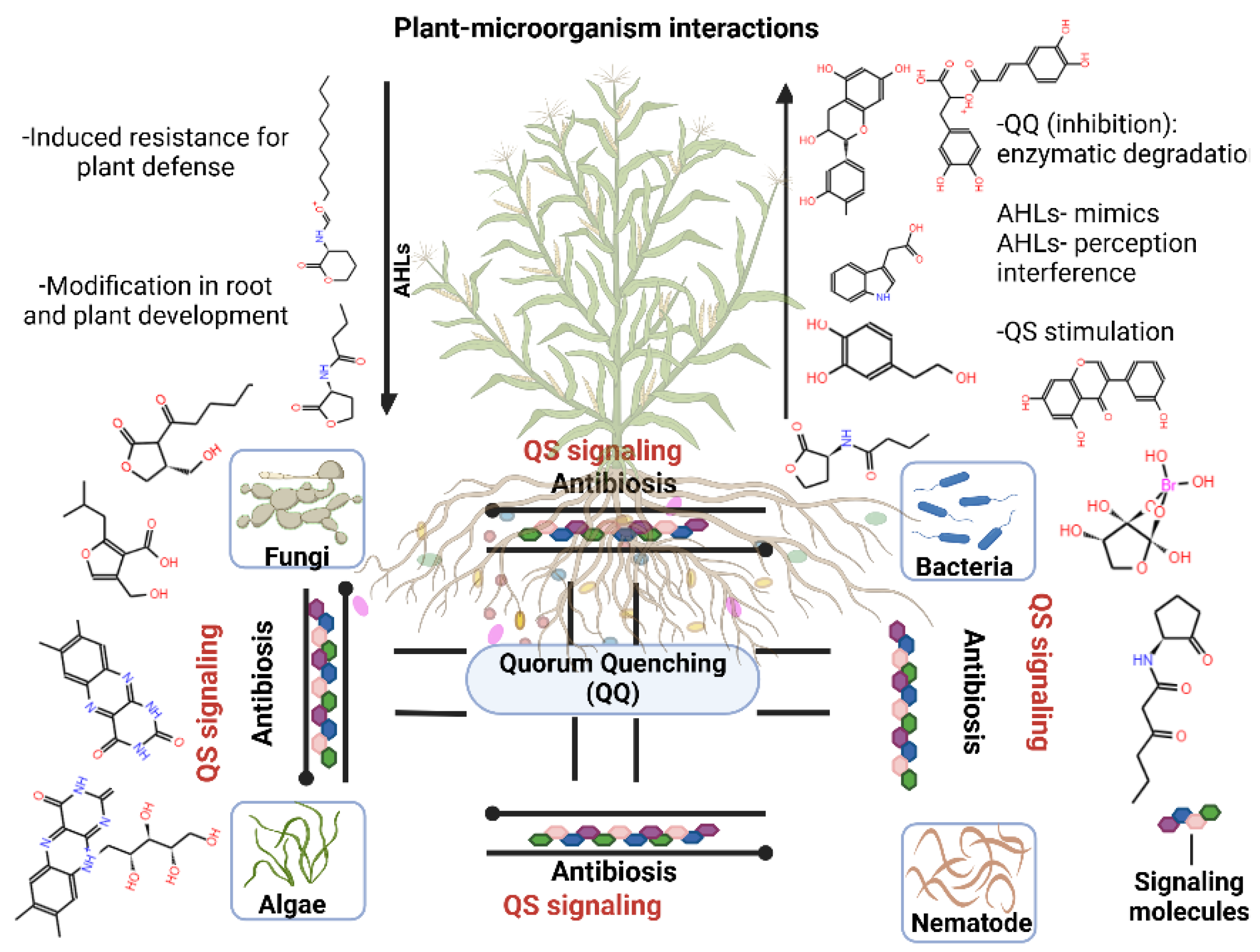

3.2.3. Quorum Sensing Detection

3.3. Plant Molecular Signaling and Microbial Communication in the Rhizosphere

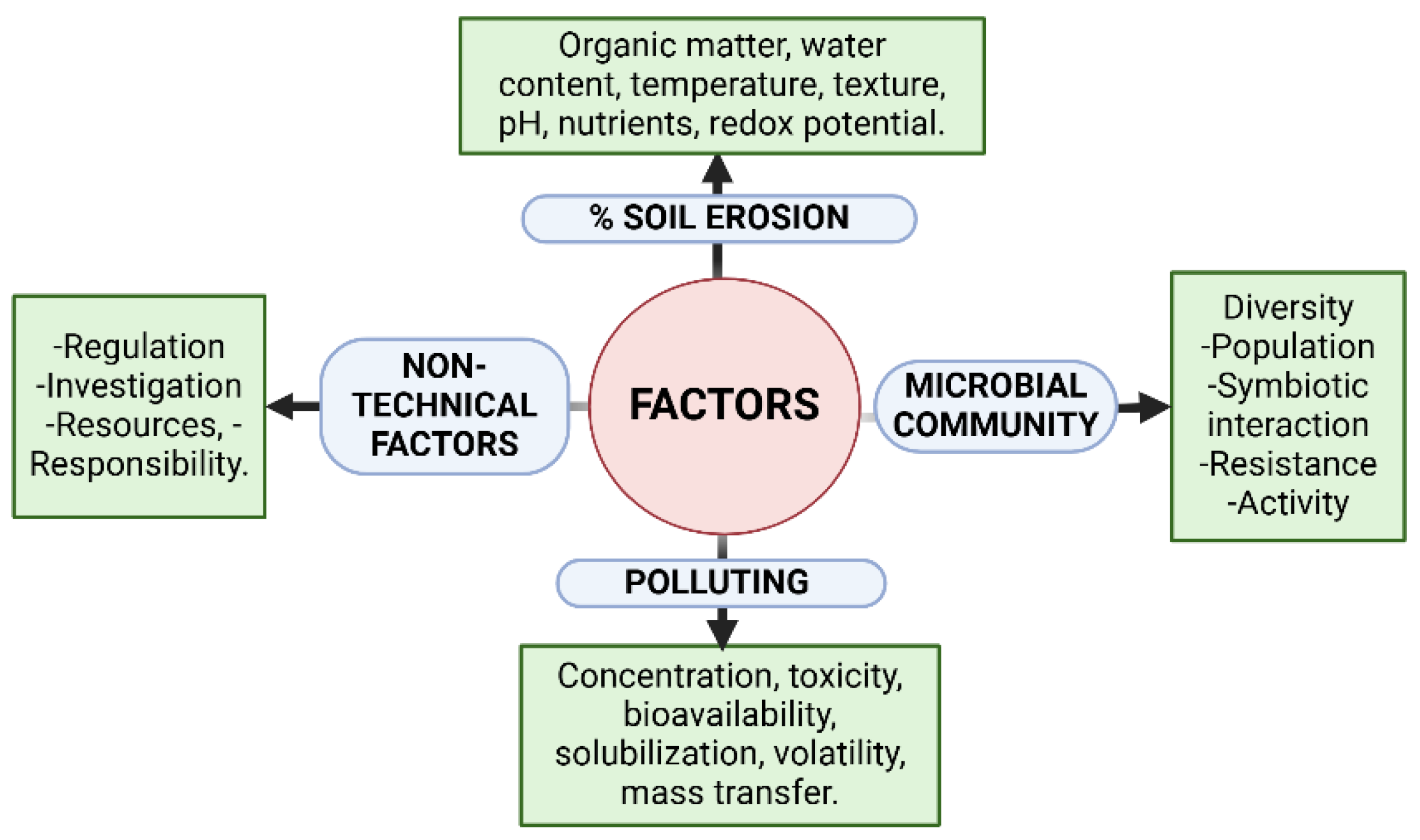

4. PGPB-Mediated Soil Restoration of Soils Degraded by Excessive Cultivation

4.1. Nutrient Dynamics in the Restoration of Degraded Soils

4.2. Biological Strategies for Mitigating Salt-Induced Stress in Degraded Soils

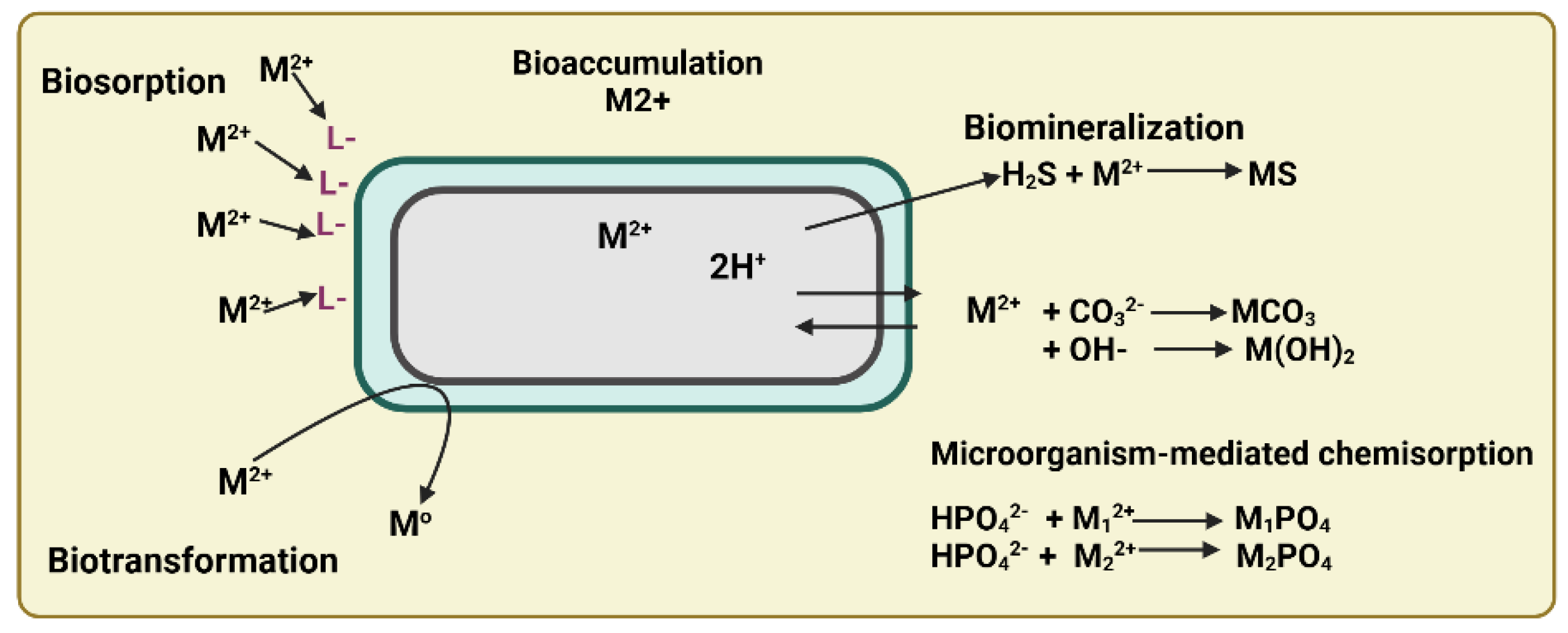

4.3. Bioremediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils Using PGPB.

5. Perspectives on Innovative Strategies for Soil Restoration Using PGPB in Overcultivated Lands

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGPB | Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria |

| PGRs | Plant Growth regulators |

| PSB | Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria |

| QS | Quorum Sensing |

| HM | Heavy Metals |

References

- Subramaniam, Y.; Masron, T.A. Food security and environmental degradation: evidence from developing countries. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, M.; Ferrari, E.; M'Barek, R.; Philippidis, G.; et al. Remaining loyal to our soil: A prospective integrated assessment of soil erosion on global food security. Ecological Economics 2024, 219, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, L.E.; Field, D.J. The science of Soil security and food security. Soil Security 2020, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Moldenhauer, W.C. Effects of soil erosion on crop productivity. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1987, 5, 303–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Espinosa, M.; Mendoza, M.E.; Medina-Orozco, L.; Prat, C.; García-Oliva, F.; López-Granados, E. Runoff, soil loss, and nutrient depletion under traditional and alternative cropping systems in the Transmexican Volcanic Belt, Central Mexico. Land Degrad. Develop. 2009, 20, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Liu, K. Cropping systems in agriculture and their impact on soil health: A review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visha Kumari, V.; Balloli, S.S.; Kumar, M.; Ramana, D.B.V.; et al. Diversified cropping systems for reducing soil erosion and nutrient loss and for increasing crop productivity and profitability in rainfed environments. Agricultural Systems 2024, 217, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, N.D.; Hill, J.D.; Liebman, M. Cropping system diversity effects on nutrient discharge, soil erosion, and agronomic performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Chaturvedi, P.; Kumar, S.; Soni, R.; Suyal, D.C. Editorial: Hazardous pollutants in agricultural soil and environment. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1411735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.T.; Kou, C.L.; Christie, P.; Dou, Z.X.; Zhang, F.S. Changes in the soil environment from excessive application of fertilizers and manures to two contrasting intensive cropping systems on the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 145, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Su, B.; Li, Z.; Shuai, Y.; Wang, J. Improved Salt Tolerance in Brassica napus L. Overexpressing a Synthetic Deinocuccus Stress-Resistant Module DICW. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Thomas Kurien, V.; Prabha, V.S.; Thomas, A.P. Monoculture vs mixed-species plantation impact on the soil quality of an ecologically sensitive area. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2020, 114, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhang, J.; Lisha, C. Impact of monoculture of poplar on rhizosphere microbial communities over time. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, J.L.A.; Vinces, L.M.G.; Murillo, D.M.S.; Chilán, G.R.M. The monoculture of corn (Zea mayz) and its impact on fertility soil. Int. J. Chem. Mater. Sci. 2021, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, H.; Fan, L.; Wang, D.; Yan, P.; et al. Variations in soil nutrient dynamics and bacterial communities after the conversion of forests to long-term tea monoculture systems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 896530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilampooranan, I.; Van Meter, K.J.; Basu, N.B. Intensive agriculture, nitrogen legacies, and water quality: intersections and implications. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, B. H.; Alam, S. Impact of intensive agricultural management on carbon and nitrogen dynamics in the humid tropics. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 66, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation agriculture as a sustainable system for soil health: A review. Soil Systems 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Inoue, H.; Mochizuki, H.; Miyamoto, T.; Asakura, M.; Shimizu, Y. Effect of hardpan on the vertical distribution of water stress in a converted paddy field. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 214, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dai, S.; Gul, S.; He, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, D. Effect of plow pan on the redistribution dynamics of water and nutrient transport in soils. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaka, S.; Ashraf, M.A. Impact of soil erosion and degradation on water quality: a review. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2017, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheb, M.R.; Venkatesh, R.; Shearer, S.A. A review on the effect of soil compaction and its management for sustainable crop production. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 46, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ojeda, P.R.; Acevedo, D.C.; Villanueva-Morales, A.; Uribe-Gómez, M. State of the essential chemical elements in the soils of natural, agroforestry and monoculture systems. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2016, 7, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Shahzad, B.; Yang, G.; et al. Soil compaction effects on soil health and crop productivity: an overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 10056-10067. [CrossRef]

- Haruna, S.I.; Anderson, S.H.; Udawatta, R.P.; Gantzer, C.J.; et al. Improving soil physical properties through the use of cover crops: A review. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20105. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.A.; Anderson, W.K. Soil compaction in cropping systems: A review of the nature, causes and possible solutions. Soil Till Res. 2005, 82, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu An, Le Wang, Mingye Zhang, Shouzheng Tong, Yifan Li, Haitao Wu, Ming Jiang, Xuan Wang, Yue Guo, Li Jiang, Synergies and trade-offs between aboveground and belowground traits explain the dynamics of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in wetlands undergoing agricultural management changes in semi-arid regions, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, Volume 381. [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, I.; Seehusen, T.; Bussell, J.; Vizitu, O.; et al. Opportunities for mitigating soil compaction in Europe—case studies from the soilcare project using soil-improving cropping systems. Land 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, C.K. Environmental pollution indices: a review on concentration of heavy metals in air, water, and soil near industrialization and urbanisation. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedolla-Rivera, H.I.; Negrete-Rodríguez, M.L.X.; Gámez-Vázquez, F.P.; Álvarez-Bernal, D.; Conde-Barajas, E. Analyzing the impact of intensive agriculture on soil quality: a systematic review and global meta-analysis of quality indexes. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiafouli, M. A.; Thébault, E.; Sgardelis, S. P.; De Ruiter, P. C.; et al. Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Srivastava, P.; Devi, R. S.; Bhadouria, R. Chapter 2: Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In: Narasimha, M., & Prasad, V. (Eds). Agrochemicals detection, treatment and remediation. Butterworth-Heinemann 2020, Pp:25-54. [CrossRef]

- Baweja, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, G. Fertilizers and pesticides: Their impact on soil health and environment. In: Giri, B., Varma, A. (eds) Soil health. Soil Biol. 2020, vol 59. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bourke, P.M.; Evers, J.B.; Bijma, P.; et al. Breeding beyond monoculture: Putting the “intercrop” into crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 734167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, C.; Li, S.; et al. Unraveling the impact of long-term rice monoculture practice on soil fertility in a rice-planting meadow soil: A perspective from microbial biomass and carbon metabolic rate. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reang, L., Bhatt, S., Tomar, R.S. et al. (2022). Plant growth promoting characteristics of halophilic and halotolerant bacteria isolated from coastal regions of Saurashtra Gujarat. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4699. [CrossRef]

- Tanya Morocho and Leiva-Mora, M. Efficient microorganisms, functional properties and agricultural applications. Ctro. Agr. 2019, vol.46, n.2 [citado 2025-03-04], pp. 93-103.

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Mechanisms and Impact of Rhizosphere Microbial Metabolites on Crop Health, Traits, Functional Components: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; et al. Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo-Santos, L.; Lopes-Olivares, F. Plant microbiome structure and benefits for sustainable agriculture. Curr. Plant Biol. 2021, 26, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Salas-González, I.; Conway, J.M.; Finkel, O.M.; et al. The plant microbiome: From ecology to reductionism and beyond. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Batista, B.D.; Bazany, K.E. y Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions under a changing world: responses, consequences and perspectives. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Berg, G.; Tack, A.J.M.; Carolina Lobato, C.; Wassermann, B. From seed to seed: the role of microbial inheritance in the assembly of the plant microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 346-355. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Romero, D.; Juárez-Sánchez, S.; Venegas, B.; Ortíz-González, C.S.; Baez, A.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. A bacterial consortium interacts with different varieties of maize, promotes the plant growth, and reduces the application of chemical fertilizer under field conditions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 616757. [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Acuña, C.; Almaraz-Suarez, J.J.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.; Ferrera-Cerrato, R.; Pineda-Mendoza, D.Y. Isolation, characterization and effect of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria on pine seedlings (Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl.). J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1727-1734. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Castillo, C.; Alatorre-Cruz, J.M.; Castañeda-Antonio, D.; et al. Potential seed germination-enhancing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for restoration of Pinus chiapensis ecosystems. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 2143–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J. S., Yadav, S. K., Bajpai, R., Teli, B., & Rashid, M. PGPR secondary metabolites: an active syrup for improvement of plant health. In: Molecular aspects of plant beneficial microbes in agriculture, Sharma, V., Salwan, R., Khalil, L. & Al-Ani, T (eds), Academic Press, 2020, pp. 195-208. [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Saha, N.; Donofrio, R.S.; Bestervelt, L.L. Microbial siderophores: a mini review. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, R.Z.; Chincholkar, S.B.; Reddy, M.S.; Gangurde, N.S.; Patel, P.R. Siderophore Producing PGPR for Crop Nutrition and Phytopathogen Suppression. In: Bacteria in Agrobiology: Disease Management, Maheshwari, D. (eds), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, B.; et al. Microbial siderophores and their potential applications: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 3984–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Rossano, S.; Trcera, N.; Verney-Carron, A.; Rommevaux, C.; Fourdrin, C.; Agnello, A.C. Direct and indirect impact of the bacterial strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa on the dissolution of synthetic Fe (III)-and Fe (II)-bearing basaltic glasses. Chem. Geol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloepper, J.W.; Leong, J.; Teintze, M.; Schroth, M.N. Enhanced plant growth by siderophores produced by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Nature 1980, 286, 885–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschat, S.; Bilitewski, U.; Blodgett, J.; Duhme-Klair, A.-K.; Dallavalle, S.; Routledge, A.; Schobert, R. Chemical and biological aspects of nutritional immunity-perspectives for new anti-infectives targeting iron uptake systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelak, A.; Napora, A.; Kacprzak, M. Using plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) to improve plant growth. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, Bernard. Beneficial Plant-Bacterial Interactions. Springer Nature 2015, 10.1007/978-3-319-13921-0. [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Glick, B.R.; Babalola, O.O. Microbial phosphorus solubilization and its potential for use in sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Fouda, A.; Attia, K.A.; et al. Isolation and characterization of plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria from desert plants and their application as bioinoculants for sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Shamsi, S.; Ali, A.; Ali, Q.; Sajjad, M.; Malik, A.; Ashraf, M. Microbial proteases applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 451237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumunang, E.; Babalola, O.O. Characterization of rhizobacteria from field grown genetically modified (GM) and non-GM maizes. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2014, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi Atouei, M.; Pourbabaee, A.A.; Shorafa, M. Alleviation of salinity stress on some growth parameters of wheat by exopolysaccharide-producing bacteria. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A: Sci. 2019, 43, 2725–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, F. Isolation of Pseudomonas flurescens from rhizosphere of faba bean and screen their hydrogen cyanide production under in vitro study, Ethiopia. Am. J. Life Sci. 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, A.; Sindhu, S.; Glick, B.R. Hydrogen cyanide production by soil bacteria: biological control of pests and promotion of plant growth in sustainable agriculture. Pedosphere 2022, 32, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.A.; Amin, M.A.; Eid, A.M.; et al. Comparative study between exogenously applied plant growth hormones versus metabolites of microbial endophytes as plant growth-promoting for Phaseolus vulgaris L. Cells 2021, 10, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, B.E.; Ahmadi, Y.; Khosroshahi, A.Y.; Dilmaghani, A. Microbial alpha-amylase production: progress, challenges and perspectives. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 10, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, C.P. Urea metabolism in plants. Plant. Sci. 2011, 180, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Teng, A.; Chu, J.; Cao, B. A quantitative, high-throughput urease activity assay for comparison and rapid screening of ureolytic bacteria. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejan, P.; Abdullah, R.; Khadiran, T.; Ismail, S.; Nasrulhaq Boyce, A. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in agricultural sustainability—a review. Molecules 2016, 21, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekureyaw, M.F.; Pandey, C.; Hennessy, R.C.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Liu, F.; Nybroe, O.; Roitsch, T. The cytokinin-producing plant beneficial bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens G20-18 primes tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) for enhanced drought stress responses. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 270, 153629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.J. The Plant Hormones: Their Nature, Occurrence, and Functions. In: Plant Hormones, Davies, P.J. (eds). Springer, Dordrecht, 1995, pp 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Li, C.; Li, J. Hormone Function in Plants. In: Hormone metabolism and signaling in plants, Li J., Li C. Smith S. (eds), Academic Press, 2017, pp 1-38. [CrossRef]

- Arc, E.; Sechet, J.; Corbineau, F.; Rajjou, L.; Marion-Poll, L. ABA crosstalk with ethylene and nitric oxide in seed dormancy and germination. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B.; Probanza, A.; Mehouachi, J.; Tadeo, F.R.; Talon, M. The plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus pumilus and Bacillus licheniformis produce high amounts of physiologically active gibberellins. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 111, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.; Kalsoom, M.; Adnan, M.; Toor, M.D.; Zulfiqar, A. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their mechanisms involved in agricultural crop production: a review. SunText Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 1, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Askari, K.; Kumari, M. Optimization of indole acetic acid production by isolated bacteria from Stevia rebaudiana rhizosphere and its effects on plant growth. J. Genet. Eng. & Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, S. and Friml J. Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell 2009, 136, 1005-1016. [CrossRef]

- Satyaprakash, M.; Satyaprakash, M.; Nikitha, T.; Reddi, E.U.B.; Sadhana, B.; Satya Vani, S. Phosphorous and phosphate solubilising bacteria and their role in plant nutrition. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 2133–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.P.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, S.; Curá, J.A. Consequence of phosphate solubilising microbes in sustainable agriculture as efficient microbial consortium: a review. Climate Change and Environmental Sustainability 2017. 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi, E.; Nosrati, R.; Owlia, P.; Malboobi, M.A.; Ghaseminejad, P.; GanjaliIranian, M.R. Zinc solubilization characteristics of efficient siderophore-producing soil bacteria. J. Microbiol. 2019, 11, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasim, F.; Ahmed, N.; Parsons, R.; Gadd, G.M. Solubilization of zinc salts by a bacterium isolated from the air environment of a tannery. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002; 213, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, F.T.; Alori, E.T.; Adekiya, A.O.; Ayorinde, B.B.; Daramola, F.Y.; Osemwegie, O.O.; Babalola, O.O. The use of soil microbial potassium solubilizers in potassium nutrient availability in soil and its dynamics. Ann. Microbiol. 2022; 72, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.; Pandey, N.; Saxena, J. Role of Potassium in Plant Photosynthesis, Transport, Growth and Yield. In: Role of Potassium in Abiotic Stress, Iqbal, N., Umar, S. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bukhat, S.; Imran, A.; Javaid, S.; Shahid, M.; Majeed, A.; Naqqash, T. Communication of plants with microbial world: Exploring the regulatory networks for PGPR mediated defense signaling. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 238, 126486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, N.R.; Haney, C.H. Mechanisms in plant-microbiome interactions: lessons from model systems. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 62, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahaya, S.M.; Mahmud, A.A.; Abdullahi, M.; Haruna, A. Recent advances in the chemistry of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as fertilizers in soil: A review. Pedosphere 2023, 33, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G.; Urtis-Flores, C.A.; Loeza-Lara, P.D.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Glick, B.R. Rhizosphere colonization determinants by Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR). Biology 2021, 10, 475. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumawat, K.C.; Kaur, S. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in nutrient enrichment: Current perspectives. In: Biofortification of Food Crops, Singh, U., Praharaj, C., Singh, S., Singh, N. (eds). Springer, New Delhi, 2016, pp263-289. [CrossRef]

- Geddes, B.A.; Oresnik, I.J. The Mechanism of Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. In: The Mechanistic Benefits of Microbial Symbionts. Advances in Environmental Microbiology vol 2. Hurst, C. (eds), Springer, Cham., 2016, pp 69-97. [CrossRef]

- Huergo, L.F. Huergo, L.F. Chandra, G.; Merrick, M. PII signal transduction proteins: nitrogen regulation and beyond. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 251-283. [CrossRef]

- Merrick, M. Post-translational modification of PII signal transduction proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Batista, M.; Dixon, R. Manipulating nitrogen regulation in diazotrophic bacteria for agronomic benefit. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, E.C.M.; Parize, E.; Gravina, F.; Pontes, F.L.D.; et al. The protein-protein interaction network reveals a novel role of the signal transduction protein PII in the control of c-di-GMP homeostasis in Azospirillum brasilense. mSystems 2020, 5, e00817-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, L.; Gao, Y.; Cui, L.; et al. Formation of NifA-PII complex represses ammonium-sensitive nitrogen fixation in diazotrophic proteobacteria lacking NifL. Cell Reports 2024, 43, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plunkett, M.H.; Knutson, C.M.; Barney, B.M. Key factors affecting ammonium production by an Azotobacter vinelandii strain deregulated for biological nitrogen fixation. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, N.; Ibhadon, A.O.; Fitzpatrick, P. A review of the existing and alternative methods for greener nitrogen fixation. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensif. 2015, 90, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, H.L.; Tezcan, F.A. Electron transfer in nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 5158–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Huang, K.; Wang, F.; Mei, Z. Molecular mechanism and agricultural application of the NifA–NifL system for nitrogen fixation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inomura, K.; Bragg, J.; Follows, M.J. A quantitative analysis of the direct and indirect costs of nitrogen fixation: a model based on Azotobacter vinelandii. ISME J. 2017, 11, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addo, M. A.; Dos Santos, P. C. Distribution of nitrogen-fixation genes in prokaryotes containing alternative nitrogenases. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2020, 21, 1749–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, H.; Abhijita, S. Nitrogen fixation and its improvement through genetic engineering. Journal of Global Biosciences 2013, 2, 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Einsle, O.; Rees, D.C. Structural enzymology of nitrogenase enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 4969–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanderban, M.; Hill, C.A.; Dhamad, A.E.; Lessner, D.J. Expression of V-nitrogenase and Fe-nitrogenase in Methanosarcina acetivorans is controlled by molybdenum, fixed nitrogen, and the expression of Mo-nitrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e01033-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lery, L.M.; Bitar, M.; Costa, M.G.; Rössle, S.C.S.; Bisch, P.M. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms of nitrogenase conformational protection against oxygen in diazotrophic bacteria. BMC Genom. 2010, 11 (Suppl 5), S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beato, V.M.; Rexach, J.; Navarro-Gochicoa, M.T.; Camacho-Cristóbal, J.J.; Herrera-Rodríguez, M.B.; González-Fontes, A. Boron deficiency increases expressions of asparagine synthetase, glutamate dehydrogenase and glutamine synthetase genes in tobacco roots irrespective of the nitrogen source. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 60, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: current status and future prospects. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzechowiak, M.; Sliwiak, J.; Link, A.; Ruszkowski, M. Legume-type glutamate dehydrogenase: Structure, activity, and inhibition studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Almagro, V.M.; Gates, A.J.; Moreno-Vivián, C.; Ferguson, S.J.; Richardson, D.J.; Roldán, M.D. Bacterial nitrate assimilation: gene distribution and regulation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1838–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhele, B.; Zhan, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X. Nitrogen assimilation in crop plants and its affecting factors. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Ye, X.Y.; Li, Z.G. Signaling role of glutamate in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1743. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, H.; Vandana Sharma, S.; Pandey, R. Phosphorus Nutrition: Plant Growth in Response to Deficiency and Excess. In: Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Oku, H., Nahar, K., Hawrylak-Nowak, B. (eds). Springer, Singapore, 2018, pp 171-190. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, E.; Zaidi, A.; Oves, M. Functional aspect of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: importance in crop production. In: Bacteria in agrobiology: Crop productivity, Maheshwari, D., Saraf, M., Aeron, A. (eds), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013, pp237-263. [CrossRef]

- Billah, M., Khan, M., Bano, A., Hassan, T. U., Munir, A., & Gurmani, A. R. Phosphorus and phosphate solubilizing bacteria: Keys for sustainable agriculture. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 36, 904-916. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Fraga, H. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotechnol. Adv. 1999, 17(4-5):319-339. [CrossRef]

- Bargaz, A.; Elhaissoufi, W.; Khourchi, S.; Benmrid, B.; et al. Benefits of phosphate solubilizing bacteria on belowground crop performance for improved crop acquisition of phosphorus. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 252, 126842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S. C. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms: Mechanism and their role in phosphate solubilization and uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Shah, Z.; Fahad, S.; et al. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria nullify the antagonistic effect of soil calcification on bioavailability of phosphorus in alkaline soils. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, A.; Pandey, P.; Mehra, S.; Singh, M.; Kaushik, S. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their efficiency on the growth of maize. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 379-391. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.; Borkar, S.; Garg, S. Chapter 11 - Phosphate solubilization by microorganisms: Overview, mechanisms, applications and advances. In: Advances in Biological Science Research, A Practical Approach, Meena, S.N & Naik, M.M (eds). Academic Press, 2019, pp161-176. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, P.; Gulati, A. Organic acid production in vitro and plant growth promotion in maize under controlled environment by phosphate-solubilizing fluorescent Pseudomonas. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.; Yasmin, S.; Rasul, M.; et al. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria with glucose dehydrogenase gene for phosphorus uptake and beneficial effects on wheat. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.; Shabanamol, S.; Rishad, K.S.; Jisha, M.S. Growth enhancement of rice (Oryza sativa) by phosphate solubilizing Gluconacetobacter sp. (MTCC 8368) and Burkholderia sp. (MTCC 8369) under greenhouse conditions. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; et al. Genome-based identification of phosphate-solubilizing capacities of soil bacterial isolates. AMB Expr. 2024, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Dong, X.Y.; Ma, J.F.; Shen, R.F. Secretion of gluconic acid from Nguyenibacter sp. L1 is responsible for solubilization of aluminum phosphate. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 784025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.S.; Park, R.D.; Kim, Y.W.; et al. PQQ-dependent organic acid production and effect on common bean growth by Rhizobium tropici CIAT 899. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 13, 955–959. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, G.; Senthilkumar, R.; Venkatesan, K.; et al. Halophilic phosphate-solubilizing microbes (Priestia megaterium and Bacillus velezensis) isolated from Arabian Sea seamount sediments for plant growth promotion. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Qin, Y.; Wu, H.; et al. Isolation and characterization of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria with multiple phosphorus sources utilizing capability and their potential for lead immobilization in soil. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: Advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms and microbial community effects. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Narayanan, M.; Shi, X.; et al. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: Their agroecological function and optimistic application for enhancing agro-productivity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 901, 166468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S.C. Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms: Mechanism and Their Role in Phosphate Solubilization and Uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 21, 49 - 68. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A.; Ahemad, M.; Oves, M.; Wani, P.A. Plant growth promotion by phosphate solubilizing fungi - current perspective. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2009, 56, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.L.; Yeung, P.; Cheng, C.; Hill, J.E. Distribution and diversity of phytate-mineralizing bacteria, ISME J. 2007, 1, 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M.; Suh, H.J.; Kim, J.M. Purification and properties of extracellular phytase from Bacillus sp. KHU-10. J. Protein Chem. 2001, 20, 287-292. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.; Green, D.M. Acid and alkaline phosphatase dynamics and their relationship to soil microclimate in a semiarid woodland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.C., Singdevsachan, S.K. Mishra, R.R., Dutta, S.K., Thatoi, H.N. Diversity, mechanism and biotechnology of phosphate solubilising microorganism in mangrove - A review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Panhwar, Q.A.; Naher, U.A.; Jusop, S.; Othman, R.; Latif, M.A.; Ismail, M.R. Biochemical and molecular characterization of potential phosphate-solubilizing bacteria in acid sulfate soils and their beneficial effects on rice growth. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M. A., Ahmad, Z. A., Akhtar, N., Iqbal, A., Mujeeb, F., & Shakir, M. A. Role of phosphate solubilizing bacteria (PSB) in enhancing P availability and promoting cotton growth. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012, 22, 204-210.

- Salsabila, N.; Fitriatin, B. N.; Hindersah, R. The role of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in soil health and phosphorus cycle: A review. IJLSAR 2023, 2, 281-287. [CrossRef]

- Alberton, D.; Valdameri, G.; Moure, V.R.; Monteiro, R.A.; et al. What did we learn from plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR)-grass associations studies through proteomic and metabolomic approaches. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 607343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Yan, J.; Xie, D. Comparison of phytohormone signaling mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drogue, B.; Combes-Meynet, E.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Wisniewski-Dyé, F.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Control of the cooperation between plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and crops by rhizosphere signals. In: Molecular microbial ecology of the rhizosphere, 1st ed., de Bruijn, F.J. (ed.), Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2013, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., pp 279-293. [CrossRef]

- Venturi, V.; Keel, C. Signaling in the rhizosphere. Trends Plant Sci. 2026, 21, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Morales, C.E.; Lerma, T.A.; Martínez, J.M.; Palencia, M.; Combatt, E.M. Phytohormones and plant growth regulators: A review. J. Sci. Technol. Appl. 2021, 10, 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz-Castro, R., Contreras-Cornejo, H. A., Macías-Rodríguez, L., & López-Bucio, J. The role of microbial signals in plant growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 701-712. [CrossRef]

- Emenecker, R.J.; Strader, L.C. Auxin-abscisic acid interactions in plant growth and development. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, V., Bhatt, I.D. y Nandi, S.K. Chapter 20 - Role and regulation of auxin signaling in abiotic stress tolerance. In: Plant signaling molecules, Khan, M.I.R., Reddy, P.S., Ferrante, A. & Khan, N.A. (Eds.). Woodhead Publishing, 2019, pp: 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Wilkinson, E.G.; Sageman-Furnas, K.; Strader, L.C. Auxin and abiotic stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 7000–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duca, D.; Lorv, J.; Patten, C.L.; et al. Indole-3-acetic acid in plant-microbe interactions. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 106, 85–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Hussain, S.; Bano, A.; et al. Potential role of phytohormones and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in abiotic stresses: consequences for changing environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4907–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, M.A. y Castro-Sowinski, S. The complex molecular signaling network in microbe-plant interaction. In: Plant microbe symbiosis: Fundamentals and advances, Arora, N. (eds), Springer, New Delhi, 2013, pp 169-199. [CrossRef]

- Di, D.W.; Zhang, C.; Luo, P.; et al. The biosynthesis of auxin: how many paths truly lead to IAA. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 78, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, M.A.; Giovannoni, J.J. Phytohormones in fruit development and maturation. Plant J. 2021, 105, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.W. The hormonal regulation of flower development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 30, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosjen, M.; Paque, S.; Weijers, D. Auxin response factors: output control in auxin biology. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.L.B.; Scortecci, K.C. Auxin and its role in plant development: structure, signalling, regulation and response mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.W. Auxin response factors. Plant, Cell & Environment 2015, 39, 1014-1028. [CrossRef]

- Bouzroud, S.; Gouiaa, S.; Nan Hu, N.; et al. Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) are potential mediators of auxin action in tomato response to biotic and abiotic stress (Solanum lycopersicum). PloS one 2018, 13, e0193517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.B.; Xie, Z.Z.; Hu, C.G.; Zhang, J.Z. A review of auxin response factors (ARF’s) in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Klink, S.; Rothballer, M. Plant growth promotion and induction of systemic tolerance to drought and salt stress of plants by quorum sensing auto-inducers of the N-acyl-homoserine lactone type: recent developments. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 683546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Negi, N.P. Pareek, S., Mudgal, G.; Kumar, D. Auxin response factors in plant adaptation to drought and salinity stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Chang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, Y. Advances in the study of auxin early response genes: Aux/IAA, GH3, and SAUR. Crop J. 2024, 12, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanai, A.; Bohia, B.; Lalremruati, F.; et al. Plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB)-induced plant adaptations to stresses: an updated review. Peer J. 2024, 12, e17882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, G.; Ozdemir-Kocak, F.; Unal, D. Chapter 15 - Hormonal signaling molecules triggered by plant growth-promoting bacteria. In: Phytohormones and Stress Responsive Secondary Metabolites, Ozturk, M., Bath R.A., Asharf M., Policarpo-Tonelli F.M., Unal B. T., Dar G. H. (eds). Academic Press, 2023, pp 187-196. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Khan, A. L., You, Y.-H., et al. Gibberellin production by newly isolated strain Leifsonia soli se134 and its potential to promote plant growth. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 106-112. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M.C.; Santoyo, G.; Glick, B.R. Recent advances in the bacterial phytohormone modulation of plant growth. Plants 2023, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Camba, R.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N.; Vielba, J.M. Plant development and crop yield: The role of gibberellins. Plants 2022, 11, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belimov, A.A.; Dodd, I.C.; Safronova, V.I.; et al. Abscisic acid metabolizing rhizobacteria decrease ABA concentrations in planta and alter plant growth. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 74, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.C.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P. Role of Abscisic Acid Producing PGPR in Sustainable Agriculture. In: Bacterial Metabolites in Sustainable Agroecosystem. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity vol 12, Maheshwari, D. (eds), Springer Cham., 2015, pp259-282. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bano, A.; Ali, S.; et al. Crosstalk amongst phytohormones from planta and PGPR under biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 90, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, B.M. Ethylene signaling in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 7710–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, A.; Shemansky, J.M.; Chang, C.; et al. History of research on the plant hormone ethylene. J Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Van de Poel, B.; Cooper, E.; et al. Conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone over 450 million years of evolution. Nature Plants 2015, 1, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.X.; Rossi, M.J.; Glick, B.R. Ethylene and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) in plant–bacterial interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, K., Fröhlich, K., García-Ramírez, G. X., Trapp, M. A., & Hirt, H. Ethylene: A master regulator of plant–microbe interactions under abiotic stresses. Cells 2023, 12, 31. [CrossRef]

- Ravanbakhsh, M.; Sasidharan, R.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; et al. Microbial modulation of plant ethylene signaling: ecological and evolutionary consequences. Microbiome 2018, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Cote, R.; Gavilanes-Ruiz, M.; Cruz-Ortega, R.; Huante, P. Importancia agrobiotecnológica de la enzima ACC desaminasa en rizobacterias, una revisión. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2013, 36, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Ma, Y.; Shadan, A. Perspective of ACC-deaminase producing bacteria in stress agriculture. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 352, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effmert, U.; Kalderás, J.; Warnke, R.; et al. Volatile mediated interactions between bacteria and fungi in the soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 665–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.W.; Hung, R.; Lee, S.; Padhi, S. 18 Fungal and Bacterial Volatile Organic Compounds: An Overview and Their Role as Ecological Signaling Agents. In: Hock, B. (eds) Fungal Associations. The Mycota 2012 vol 9. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Minerdi, D.; Maggini, V.; Fani, R. Volatile organic compounds: from figurants to leading actors in fungal symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Carrillo, R.; Guerra Ramírez, P. Pseudomonas spp. benéficas en la agricultura. Rev. Mexicana Cienc. Agric. 2022, 13, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Valencia, F.D.; Plascencia-Espinosa, M.Á.; Morales-García, Y.E.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. Selection and effect of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria on pine seedlings (Pinus montezumae and Pinus patula). Life 2024, 14, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabu, R.; Aswani, R.; Jishma, P.; et al. Plant growth promoting endophytic Serratia sp. zob14 protecting ginger from fungal pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., India, Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 89, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Kankariya, R.A.; Chaudhari, A.B.; Gavit, P.M.; Dandi, N.D. 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol: A novel biotech bioactive compound for agriculture. In: Microbial interventions in agriculture and environment, Singh, D., Gupta, V., Prabha, R. (eds). Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp491-452. [CrossRef]

- Jani, J.; Parvez, N.; Mehta, D. Metabolites of Pseudomonads: A new avenue of plant health management. In: New horizons in insect science: Towards sustainable pest management, Chakravarthy, A. (eds) Springer, New Delhi, 2015, pp61-69. [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Gafur, A.; Ansari, M.J.; Ray, R.R. PGPR in biofilm formation and antibiotic production. In: Antifungal metabolites of rhizobacteria for sustainable agriculture, Fungal Biology series, Sayyed, R., Singh, A., Ilyas, N. (eds) Springer, Cham., 2022, pp 65-82. [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Negi, R.; Khan, S.S.; et al. Microbes mediated induced systemic response in plants: A review. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A, Singh, & A.K. Role of bacterial Quorum Sensing in plant growth promotion. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 18. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Mulla, S.I.; Lee, K.J.; Chae, J.C.; Shukla, P. VOCs-mediated hormonal signaling and crosstalk with plant growth promoting microbes. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 1277–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Zhang, H. The effects of bacterial volatile emissions on plant abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laller, R.; Khosla, P.K.; Negi, N.; et al. Bacterial volatiles as PGPRs: Inducing plant defense mechanisms during stress periods. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 159, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyuta, V.; Lipasova, V.; Popova, A.; et al. Influence of volatile organic compounds emitted by Pseudomonas and Serratia strains on Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilms. APMIS 2016, 124, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Raza, W.; Jiang, G.; et al. Bacterial volatile organic compounds attenuate pathogen virulence via evolutionary trade-offs. ISME J. 2023, 17, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, M.I.; Piater, L.A.; Dubery, I.A. Profiling of volatile organic compounds from four Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria by SPME–GC–MS: A metabolomics study. Metabolites 2022, 12, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, A.; Schikora, A. AHL-priming for enhanced resistance as a tool in sustainable agriculture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamkhi, I.; El Omari, N.; Benali, T.; Bouyahya, A. Quorum sensing and plant-bacteria interaction: role of quorum sensing in the rhizobacterial community colonization in the rhizosphere. In: Quorum Sensing: Microbial Rules of Life, vol 1374, Dhiman S. S. (eds), ACS Publishers, Washington D.C. USA, 2020, pp. 139-153. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.; Handy, D.; Headlee, A.; et al. Quorum Sensing in the rhizosphere. In: Microbial cross-talk in the rhizosphere. Rhizosphere Biology, Horwitz, B.A., Mukherjee, P.K. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2022, pp 99-134. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A. Quorum sensing N-acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules of plant beneficial Gram-negative rhizobacteria support plant growth and resistance to pathogens. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.K.; Malik, K.A.; Hameed, S.; Saddique, M. J.; et al. Growth stimulatory effect of AHL producing Serratia spp. from potato on homologous and non-homologous host plants. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 238, 126506. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, G.; Sekar, J.; Ramalingam, P.V. Detection of diverse N-Acyl Homoserine Lactone signalling molecules among bacteria associated with rice rhizosphere. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3480–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.S.; Arshad, A.; Rajput, L.; Fatima, K.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.; Imran, A. Growth-stimulatory effect of quorum sensing signal molecule N-acyl-homoserine lactone-producing multi-trait Aeromonas spp. on wheat genotypes under salt stress. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 553621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mata, A.; Fernández-Domínguez, I.J.; Nuñez-Reza, K.J.; Xiqui-Vázquez, M.L.; Baca, B.E. Redes de señalización en la producción de biopelículas en bacterias: quorum sensing, di-GMPc y óxido nítrico. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2014, 46, 242-255. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Bhargava, P.; Goel, R. Quorum sensing molecules of rhizobacteria: A Trigger for developing systemic resistance in plants. In: Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for sustainable stress management. Microorganisms for Sustainability vol 12, Sayyed, R., Arora, N., Reddy, M. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp117-138. [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Gafur, A.; Ansari, M.J.; Ray, R.R. PGPR in biofilm formation and antibiotic production. In: Antifungal metabolites of rhizobacteria for sustainable agriculture. Fungal Biology Series, Sayyed, R., Singh, A., Ilyas, N. (eds) Springer, Cham., 2022, pp 65-82. [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, A.; Dailin, D.J.; Abo-Zaid, G.A.; et al. Biosynthesis of antibiotics by PGPR and their roles in biocontrol of plant diseases. In: Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for sustainable stress management. Microorganisms for Sustainability vol. 13, Sayyed, R. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp1-35. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Meng, G.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Fungal Quorum-Sensing molecules and inhibitors with potential antifungal activity: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, P.; Casadevall, A. Quorum sensing in fungi – a review. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, S.; et al. Bacterial-fungal interactions under agricultural settings: from physical to chemical interactions. Stress Biol. 2022, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S., Keller, N.P. Chemical signals driving bacterial–fungal interactions. "Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 1334-1347. [CrossRef]

- Khashi u Rahman, M.; Zhou, X.; Wu, F. The role of root exudates, CMNs, and VOCs in plant–plant interaction. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wenqing LI, W.; Binghai Du, B.; LI, H. Effect of biochar applied with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on soil microbial community composition and nitrogen utilization in tomato. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 872-881. [CrossRef]

- Jagodzik, P.; Tajdel-Zielinska, M.; Ciesla, A.; Marczak, M.; Ludwikow, A. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plant hormone signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalmi, S.K.; Sinha, A.K. ROS mediated MAPK signaling in abiotic and biotic stress-striking similarities and differences. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysan, P.J.; Colcombet, J. Cellular complexity in MAPK signaling in plants: Questions and emerging tools to answer them. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1674. [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.P.; Nicole, M.C.; Sritubtim, S.; et al. Ancient signals: comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plant signaling. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 301–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danquah, A.; De Zélicourt, A.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. The role of ABA and MAPK signaling pathways in plant abiotic stress responses. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigeard, J.; Hirt, H. Nuclear signaling of plant MAPKs. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogene, S. Tibor J. Zoltán M. Unveiling the significance of rhizosphere: Implications for plant growth, stress response, and sustainable agriculture, Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, Volume 206 108290. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, F.; Mukhtar, H.; Fouillaud, M.; Dufossé, L. Rhizosphere Signaling: Insights into Plant-Rhizomicrobiome Interactions for Sustainable Agronomy. Microorganisms 2022, Apr 25;10, 899. [CrossRef]

- Pardo Díaz, S.; Mazo Molina, D.C.; Rojas Tapias, D.F. Bacterias promotoras del crecimiento vegetal: filogenia, microbioma, y perspectivas. In: Rol de las bacterias promotoras de crecimiento vegetal en sistemas de agricultura sostenible. Bonilla Buitrago, R. González de Bashan, L. E., & Pedraza, R. O. (eds). Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria – AGROSAVIA, Cundinamarca, Colombia, 2021, pp 46-77. [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.S.; Ayangbenro, A.S.; Glick, B.R.; et al. Plant health: feedback effect of root exudates-rhizobiome interactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.U.H.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J.; Rehman, A.; Yasmeen, R. The impact of climate change and production technology heterogeneity on China's agricultural total factor productivity and production efficiency. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2024, 907, 168027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, Z. H., Iqbal, J., Zhang, Q., Chen, D., Wei, H., & Saleem, M. Continuous cropping alters multiple biotic and abiotic indicators of soil health. Soil Systems 2020, 4, 59. [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Mittler, R. Plant responses to multifactorial stress combination. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasri, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Satish, L.; et al. An overview of abiotic stress in cereal crops: Negative Impacts, regulation, biotechnology and integrated omics. Plants 2021, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Guzman, M.; Cellini, F.; Fotopoulos, V.; Balestrini, R.; Arbona, V. New approaches to improve crop tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshome, D. T.; Zharare, G. E.; Naidoo, S. The threat of the combined effect of biotic and abiotic stress factors in forestry under a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 601009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Xue, D.; et al. Enhanced plant growth through composite inoculation of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: Insights from plate and soil experiments. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.L.; Liu, J.; Jia, P.; et al. Novel phosphate-solubilizing bacteria enhance soil phosphorus cycling following ecological restoration of land degraded by mining. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Z.; Hamid, B.; Yatoo, A.M.; et al. Phosphorus solubilizing microorganisms: An eco-friendly approach for sustainable plant health and bioremediation. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6838–6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Xu, L. González-Hernández, A.I. Camañes, G. Vicedo, B. Scalschi, L. Llorens, E. Harnessing Green Helpers: Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria and Other Beneficial Microorganisms in Plant–Microbe Interactions for Sustainable Agriculture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 621. [CrossRef]

- Dobbelaere, S.; Vanderleyden, J.; Okon, Y. Plant growth-promoting effects of diazotrophs in the rhizosphere. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2003, 22, 107–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Sah, D.; Chakraborty, M.; Rai, J.P.N. Mechanism and application of bacterial exopolysaccharides: An advanced approach for sustainable heavy metal abolition from soil. Carbohydr. Res. 2024, 544, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaut, F., Urquiaga, M.C. d. O., Rosman, A. C., da Silva, M. L., & Hemerly, A. S. The impact of non-nodulating diazotrophic bacteria in agriculture: understanding the molecular mechanisms that benefit crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11301. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J., Daliakopoulos, I. N., del Moral, F., Hueso, J. J., & Tsanis, I. K. A review of soil-improving cropping systems for soil salinization. Agronomy 2019, 9, 295. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, B.S.; McGlinn, D.J.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; et al. Diazotrophs show signs of restoration in amazon rain forest soils with ecosystem rehabilitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00195-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Hanif, M.; Abideen, Z.; Sohail, M.; et al. Mechanisms and strategies of plant microbiome interactions to mitigate abiotic stresses. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Motos, J. R., Ortuño, M. F., Bernal-Vicente, A., Diaz-Vivancos, P., Sanchez-Blanco, M. J., & Hernandez, J. A. Plant responses to salt stress: Adaptive mechanisms. Agronomy 2017, 7, 18. [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil salinity and sodicity in drylands: A review of causes, effects, monitoring, and restoration measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, B.; Örçen, N. Soil salinization and climate change. In: Climate change and soil interactions. Prasad, M.N.V., Pietrzykowski, M. (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2020, pp 331-350. [CrossRef]

- Madline, A.; Benidire, L.; Boularbah, A. Alleviation of salinity and metal stress using plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria isolated from semiarid Moroccan copper-mine soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 67185–67202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Noori, F. Soil salinity as a challenge for sustainable agriculture and bacterial-mediated alleviation of salinity stress in crop plants. In: Saline soil-based agriculture by halotolerant microorganisms, Kumar, M., Etesami, H., Kumar, V. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Shultana, R., Zuan, A. T. K., Naher, U. A., et al. The PGPR mechanisms of salt stress adaptation and plant growth promotion. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2266. [CrossRef]

- Hnini, M., Rabeh, K., & Oubohssaine, M. (). Interactions between beneficial soil microorganisms (PGPR and AMF) and host plants for environmental restoration: A systematic review. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100391. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I., Sharma, S., Sharma, V., et al. (). PGPR-Enabled bioremediation of pesticide and heavy metal-contaminated soil: A review of recent advances and emerging challenges. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142678. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Khan, F.; Alqahtani, F.M.; et al. Plant Growth–Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) assisted bioremediation of heavy metal toxicity. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 2928–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobariu, D.L.; Fertu, D.I.T.; Diaconu, M.; et al. Rhizobacteria and plant symbiosis in heavy metal uptake and its implications for soil bioremediation. New Biotechnol. 2017, 39, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, S.J. What is a" heavy metal" Journal of chemical education 1997, 74, 1374. [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C.; Clark, R.B. Micronutrients in crop production. Adv. Agron. 2002, 77, 185–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banuelos, G. S., & Ajwa, H. A. Trace elements in soils and plants: an overview. J. Environ. Sci. Health 1999, Part A 34, 951-974. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, Y.; Lan, X.; et al. Comprehensive assessment of harmful heavy metals in contaminated soil in order to score pollution level. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Mukherjee, S.K.; Hossain, S.T. Exploration of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) for heavy metal bioremediation and environmental sustainability: Recent advances and future prospects. In: Modern approaches in waste bioremediation, Shah, M.P. (eds), Springer Cham., 2023, pp 29-55. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.; Dias, N.; Alvarado, R.; Soto, J.; et al. N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) type signal molecules produced by rhizobacteria associated with plants that growing in a metal (oids) contaminated soil: A catalyst for plant growth. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 281, 127606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A. R., Yin, Q., Oliveira, R. S., Silva, E. F., & Novo, L. A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils: Current knowledge and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156435. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Ghosh, P.K.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Role of heavy metal resistant Ochrobactrum sp. and Bacillus spp. strains in bioremediation of a rice cultivar and their PGPR like activities. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Franks, A.E. PGPR enhanced phytoremediation of petroleum contaminated soil and rhizosphere microbial community response. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riseh, R.S.; Vazvani, M.G.; Hajabdollahi, N.; et al. Bioremediation of heavy metals by rhizobacteria. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 4689–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitara, M.K.; Chauhan, S.; Singh, R.P. Bioremediation of polluted soil by using plant growth–promoting rhizobacteria. In: Microbial rejuvenation of polluted environment. Microorganisms for sustainability vol. 25, Panpatte, D.G., Jhala, Y.K. (eds), Springer, Singapore, 2021, pp203-226. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). El estado de los recursos de tierras y aguas del mundo para la alimentación y la agricultura - Sistemas al límite, Informe de síntesis. FAO, Rome, Italy, 2021, 1-86. [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Soil degradation, land scarcity and food security: Reviewing a complex challenge. Sustainability 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Organization. 2023 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Summit. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/2023/05/un-2023-sdg-summit/ (accessed on 22-05- 2024).

- Sharma, I.P.; Chandra, S.; Kumar, N.; Chandra, D. PGPR: Heart of soil and their role in soil fertility. In: Agriculturally important microbes for sustainable agriculture, Meena, V., Mishra, P., Bisht, J., Pattanayak, A. (eds). Springer, Singapore, 2017, pp 51-67. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Tabassum, B.; Hashim, M.; Khan, N. Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) as a plant growth enhancer for sustainable agriculture: A review. Bacteria 2024, 3, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Pellegrini, M.; Guerra-Sierra, B.E. Interaction between plants and Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) for sustainable development. Bacteria 2024, 3, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Patel, H. PGPR: A sustainable agricultural mitigator for stressed agro-environments. In: Plant growth promoting microorganisms of arid region, Mawar, R., Sayyed, R.Z., Sharma, S.K., Sattiraju, K.S. (eds). Springer, Singapore, 2023, pp303-318. [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, Y.E.; Juárez-Hernández, D.; Hernández-Tenorio, A.L.; et al. Inoculante de segunda generación para incrementar el crecimiento y salud de plantas de jardín. AyTBUAP 2020, 5, 136-154. [CrossRef]

- Menguala, C.; Schoebitz, M.; Azcón, R. y Roldán, A. Microbial inoculants and organic amendment improves plant establishment and soil rehabilitation under semiarid conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 134, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Ilyas, N.; Jayachandran, K.; Shabir, S.; et al. Advances in biochar and PGPR engineering system for hydrocarbon degradation: A promising strategy for environmental remediation. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbuganesan, V.; Vishnupradeep, R.; Bruno, L.B.; Sharmila, K.; Freitas, H.; Rajkumar, M. Combined Application of Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Improves Heavy Metal and Drought Stress Tolerance in Zea mays. Plants 2024, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, S.; Jebara, S.H.; Saadani, O.; Abid, G.; et al. In situ effects of Lathyrus sativus-PGPR to remediate and restore quality and fertility of Pb and Cd polluted soils. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 192, 110260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Hussain, I.; Khan, A.H.A.; Muhammad, Y.S.; et al. Combined application of biochar, compost, and bacterial consortia with Italian ryegrass enhanced phytoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 153, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Khan, M.I.; Bashir, S.; Azam, M.; et al. Biochar and Bacillus sp. MN54 assisted phytoremediation of diesel and plant growth promotion of maize in hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnikova, T.; Kolesnikov, S.; Minin, N.; Gorovtsov, A.; Vasilchenko, N.; Chistyakov, V. The influence of remediation with Bacillus and Paenibacillus strains and Biochar on the biological activity of petroleum-hydrocarbon-contaminated haplic chernozem. Agriculture 2023, 13(3):719. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, P.; et al. Biochar bacteria-plant combined potential for remediation of oil-contaminated soil. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1343366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, E.M.; Alsohim, A.S.; Farig, M.; Omara, A.E.D.; Rashwan, E.; Kamara, M.M. Synergistic effect of biochar and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on alleviation of water deficit in rice plants under salt-affected soil. Agronomy 2019, 9, 847. [CrossRef]

- Nehela, Y.; Mazrou, Y.S.A.; Alshaal, T.; Rady, A.M.S.; et al. The integrated amendment of sodic-saline soils using biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria enhances maize (Zea mays L.) resilience to water salinity. Plants 2021, 10, 1960. [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.; Sanaullah, M.; Mahmood, F.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, T. Co-application of biochar and salt tolerant PGPR to improve soil quality and wheat production in a naturally saline soil. Rhizosphere 2024, 29, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.R.; Gurr, G.M.; Wratten, S.D. Ecological restoration of farmland: progress and prospects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 831-847. [CrossRef]

- Gairola, S.U.; Bahuguna, R.; Bhatt, S.S. Native plant species: A tool for restoration of mined lands. J. Soil Sci. Plant. Nutr. 2023, 23, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, C.; Bonifacio, A.; Villca, M.; et al. Arbustos y pastos para restablecer la cobertura vegetal en zonas áridas del Sur de Bolivia. CIMMYT, Mexico, 2022, pp 1-12. https://hdl.handle.net/10883/22242.

- de-Bashan, L. E., Hernandez, J. P., & Bashan, Y. The potential contribution of plant growth-promoting bacteria to reduce environmental degradation – A comprehensive evaluation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 61, 171-189. Lopez-Lozano et al., 2016. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yao, T.; et al. Effects of PGPR microbial inoculants on the growth and soil properties of Avena sativa, Medicago sativa, and Cucumis sativus seedlings. Soil Till. Res. 2020, 199, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshru, B., Mitra, D.; Khoshmanzar, E., Myo, E. M., Uniyal, N., Mahakur, B., et al. Current scenario and future prospects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: an economic valuable resource for the agriculture revival under stressful conditions. J. Plant Nut. 2020, 43, 3062–3092. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Prasad, P.; Das, S.N.; Kalam, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) as green bioinoculants: Recent developments, constraints, and prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).