Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Contextual Overview

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Research Questions

- 1.

- What statistically significant differences occur in senior secondary students’ initial and final experiences of learning mathematics in flipped classroom environments?

- 2.

- What opportunities and challenges do senior secondary students identify in flipping their mathematics classrooms?

- 3.

- What improvement measures do senior secondary students suggest to maximize their flipped mathematics learning experiences?

1.4. Literature Review

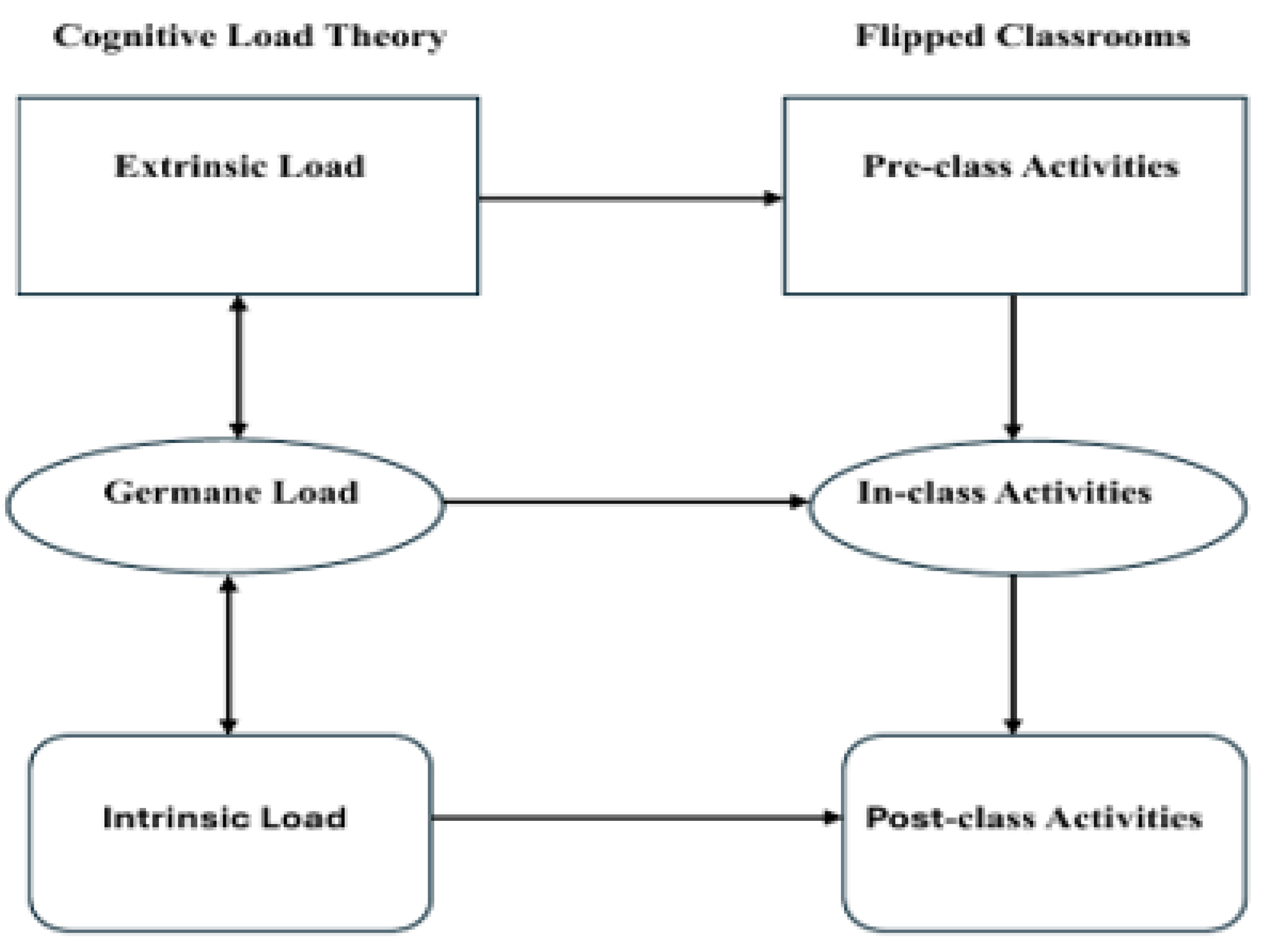

1.4. Theoretical Framework

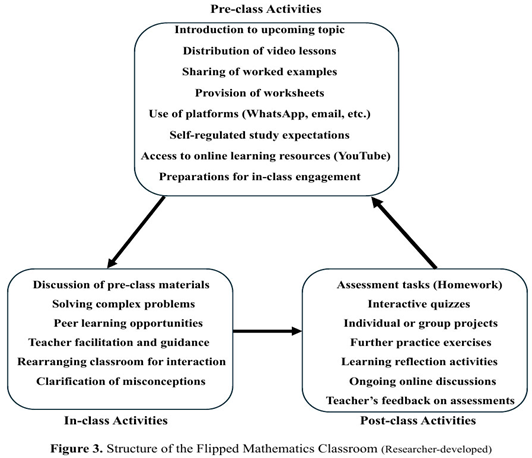

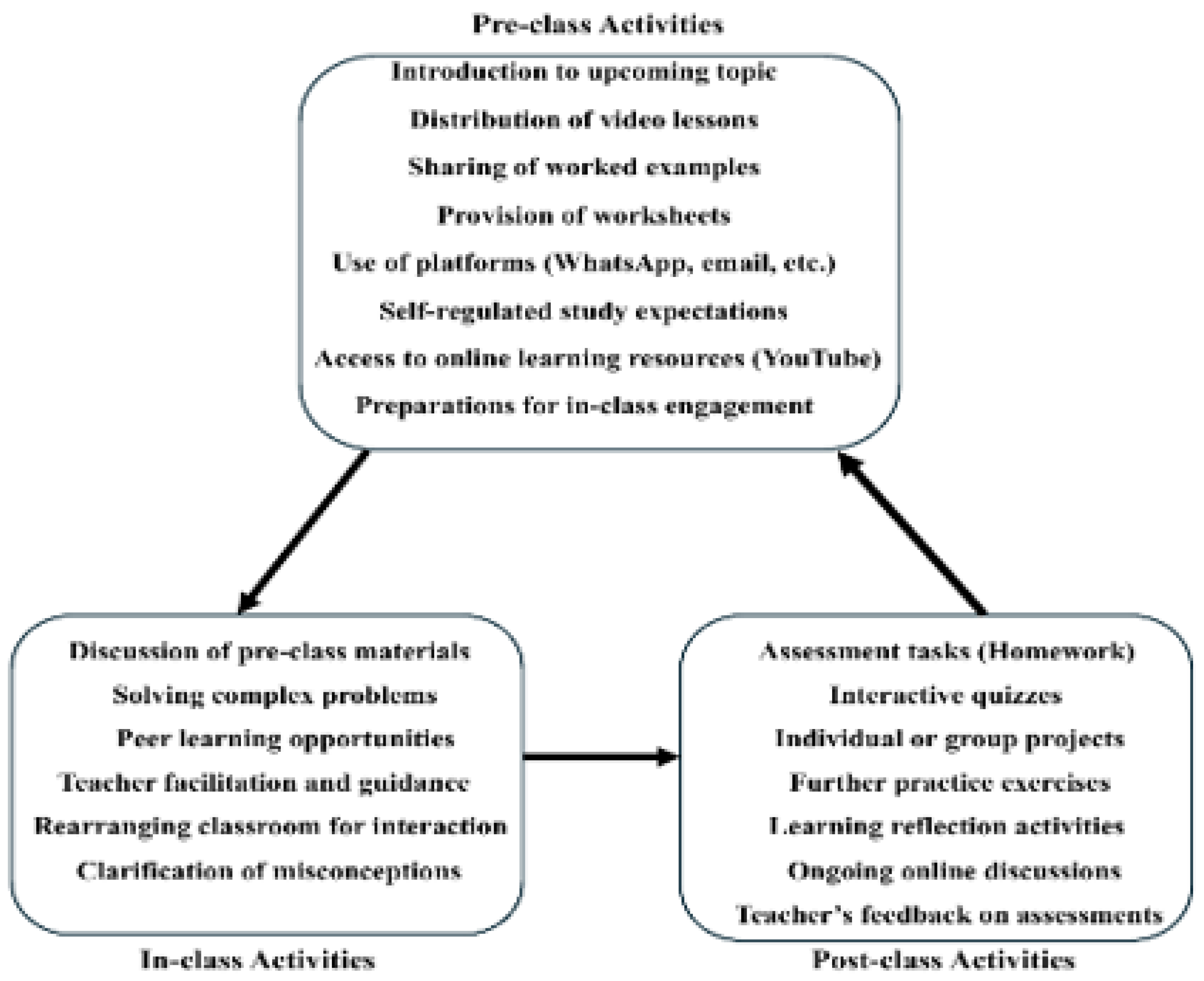

1.6. Overview of Strategies Applied while Learning Mathematics in the FC Environments

2. Methodology

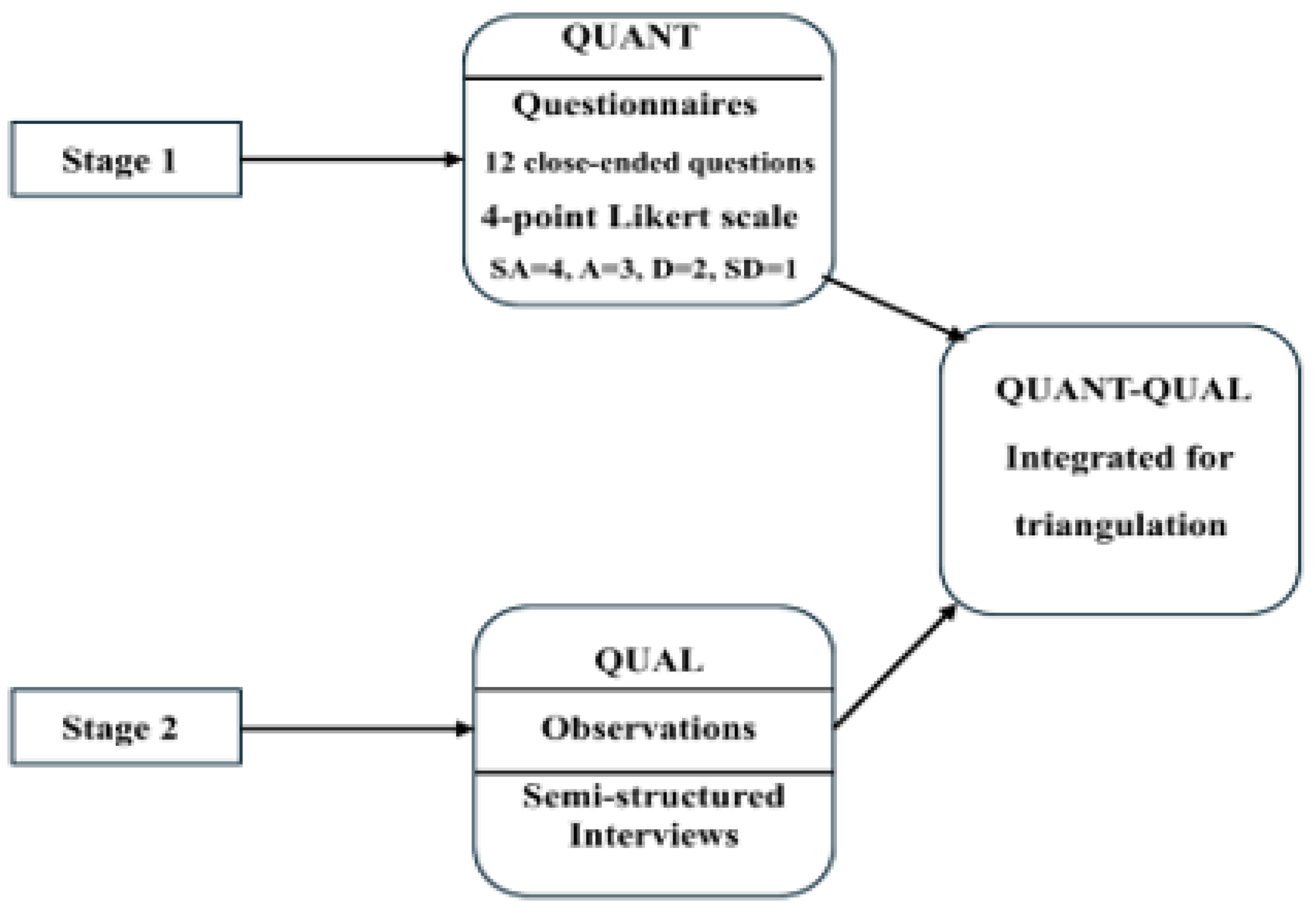

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participant Selection Process

| School | Q | R | S | T | Total | ||||||||||||

| Class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 16 |

| Student | 48 | 51 | 49 | 53 | 58 | 54 | 51 | 44 | 48 | 48 | 46 | 42 | 52 | 50 | 51 | 49 | 794 |

| Sample | Q = 67 | R = 55 | S = 76 | T = 68 | 266 | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 | 266 | |||||||||

|

Schools |

Number of Students | |||||||

| Gender | Ages |

Total |

||||||

|

M |

F |

Lower Ages | Upper Ages | |||||

| ≤ 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | ≥ 20 | ||||

| Q | 33 | 34 | 8 | 22 | 17 | 14 | 6 | 67 |

| R | 28 | 27 | 5 | 29 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 55 |

| S | 38 | 38 | 7 | 38 | 21 | 8 | 2 | 76 |

| T | 33 | 35 | 9 | 29 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 68 |

| Total | 132 | 134 | 29 | 118 | 70 | 32 | 17 | 266 |

2.3. Development and Validation of Instruments

2.4. Training the Teachers Prior to Implementation

2.5. Procedure for Capturing Participants’ FC Learning Experiences

2.6. Reducing Biases in the Study

2.7. Ethical Measures

3. Results

3.1. Flipped Classroom Performance Ratings across Schools

| Observation Criteria | Schools | ||||||||

| Q | R | S | T | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Section A: Classroom Environments | |||||||||

| 1. | Classroom arrangement for flipped learning | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 2. | Availability of relevant technological resources for in-class use | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| 3. | Evidence of pre-class materials brought to class for clarification and discussion | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Section B: Teaching Practices | |||||||||

| 4. | Usage of instructional videos for in-class lesson | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. | Teacher clarifies and guides students in solving unclear, complex pre-class tasks. | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Section C: Student Interaction | |||||||||

| 6. | Students ask and answer questions in class. | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. | Students collaborate and provide feedback on pre-class to their different groups. | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. | Teacher actively engages and motivates students in class. | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Section D: Overall Implementation | |||||||||

| 9. | Implementation of FCs is generally in line with best practices. | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Total (45) | 26 | 41 | 26 | 37 | 27 | 41 | 28 | 40 | |

| Percentage (%) | 58% | 91% | 58% | 82% | 60% | 91% | 62% | 89% | |

| Rating Description | Very Good | Good | Average | Below Average | Weak |

| Score | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

3.2. Analysis of Questionnaire Responses

3.2.1. Analysis of Participants’ Initial-FC Experiences

3.2.2. Analysis of Participants’ Post-FC Experiences

3.2.3. Descriptive Statistics for Participants’ Initial-FC and Post- FC Experiences

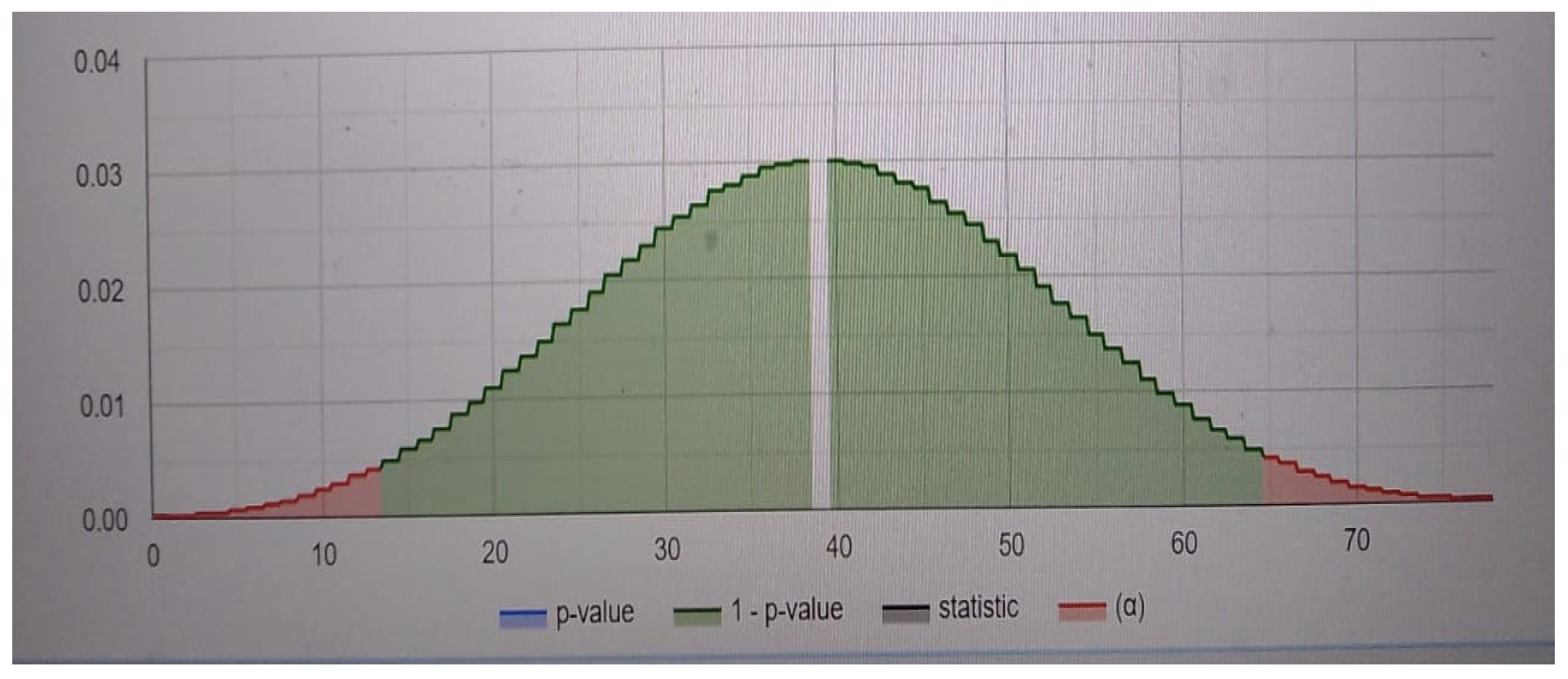

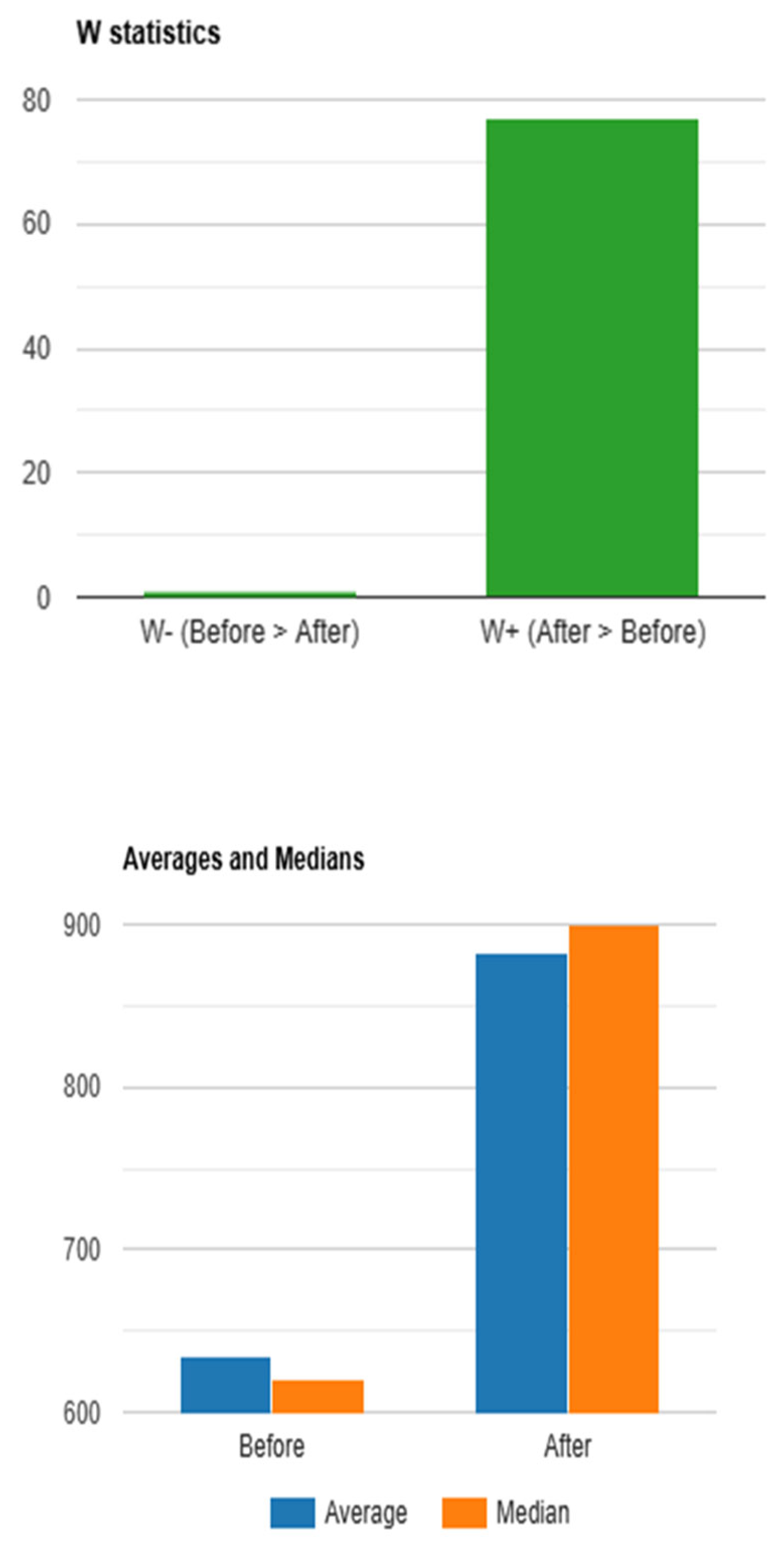

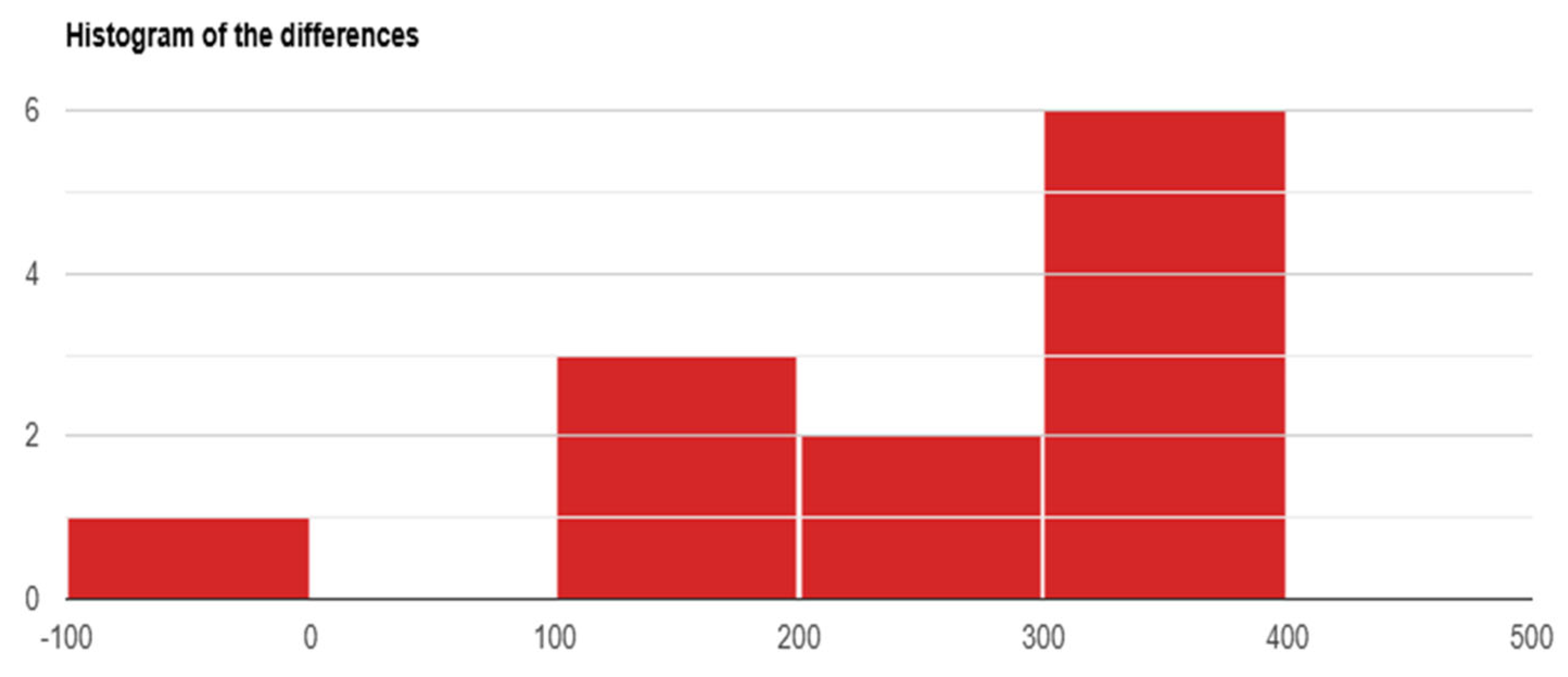

3.2.4. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for Two Dependent Samples

| Parameter | Value |

| P-value | 0.00001252 |

| t | 6.9249 |

| Sample size (n) | 12 |

| Average of differences | 248.3333 |

| SD of differences | 124.2266 |

| Normality p-value | 0.2737 |

| A priori power | 0.4919 |

| Post hoc power | 1 |

| Skewness | -0.7309 |

| Excess kurtosis | -0.3739 |

3.2.5. Interpretation of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

3.3. Thematic Analysis of the Semi-structured Interview Data

3.3.1. Opportunities and Challenges Participants Identified in Flipped Classrooms (FCs)

| S/N | Theme | Participants per Theme | n(Participants) |

| Opportunities | Stu- | ||

| 1. | Flexible learning | 2, 6, 9, 11, 1, 7, 10 | 7 |

| 2. | Active engagement | 4, 9, 1, 8, 5, 3, 6, 10, 12 | 9 |

| 3. | Peer collaboration | 2, 8, 3, 10, 12, 4, 7, 11 | 8 |

| Challenges | |||

| 1. | High self-discipline required | 3, 10, 6, 9, 5, 8, 9, 11 | 8 |

| 2. | Limited access to necessary resources | 5, 11, 2, 8, 4, 1, 3, 6, 7, 12 | 10 |

| 3. | Learning disparities | 7, 12, 5, 6, 9, 10 | 6 |

3.3.2. Improvement Measures for Optimal Flipped Classroom Learning Experiences

| S/N | Theme | Participants per Theme | n(Participants) |

| 1. | Need to enhance pre-class materials | 2, 6, 9, 11, 10, 5 | 6 |

| 2. | Providing additional support mechanisms | 3, 10, 5, 8, 1, 6, 7, 12 | 8 |

| 3. | Modification of in-class activities | 1, 4, 7, 12, 10, 2, 3 | 7 |

| 4. | Improving Feedback Practices: | 6, 9, 2, 11, 12, 7, 4, 5T | 8 |

| 5. | Greater focus on individual learning needs | 5, 8, 3, 10, 1, 6, 7 | 7 |

4. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Recommendations for Future Actions

- The study offers empirical evidence on the FC model’s capacity to improve student engagement and academic performance, aligning with findings from previous research that emphasize the benefits of active learning strategies in mathematics education.

- The study's insights into student perspectives on benefits and challenges in learning mathematics through the FCs may inform teachers and policymakers about best practices for effective application of the model to better meet students’ educational needs.

- By pinpointing specific areas for improvement based on student feedback, the research may guide curriculum development and instructional design to foster more engaging, student-centered learning experiences that boost conceptual understanding, technological accessibility, and overall academic performance in flipped mathematics classrooms.

- Furthermore, the findings may influence educational policy by advocating for increased training and resources for teachers to facilitate successful flipped mathematics classroom implementations.

- Overall, this study enriches the understanding of flipped mathematics instruction and its implications for improving educational outcomes in secondary education.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abah, J. A.; Anyagh, P. I.; Age, T. J. A flipped applied mathematics classroom: Nigerian university students' experience and perceptions. Abacus 2017, 42(1), 78-87. ffhal-01596571f. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi, T. O. Credit in mathematics in senior secondary certificate examinations as a predictor in educational management in universities in Ondo and Ekiti States. Nigeria. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 2010, 5, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Agah, M. P. The relevance of mathematics education in the Nigerian contemporary society: Implications to secondary education. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioral Science 2020, 33(5), 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, S. F.; Hafeez, M. Critical Review on Flipped Classroom Model Versus Traditional Lecture Method. International Journal of Education and Practice 2021, 9(1), 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, G.; Akçayır, M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education 2018, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaraju, S. The role of flipped learning in managing the cognitive load of a threshold concept in physiology. Journal of Effective Teaching 2016, 16(3), 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Akor, V. O.; Atuzie, C. Expository review of flipped classroom model: An innovative teaching approach for universities in Nigeria. Contemporary Journal of Education and Development 2023, 3(12). [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, L.; Alcubilla, P.; Leguízamo, L. Ethical considerations in informed consent. IntechOpen 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, F. D.; Navarro, M.; Elfanagely, Y.; Elfanagely, O. Biases in research studies. In Translational surgery; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asún, R. A.; Rdz-Navarro, K.; Alvarado, J. M. Developing multidimensional Likert scales using item factor analysis: The case of four-point items. Sociological Methods & Research 2016, 45(1), 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awidi, I. T.; Paynter, M. The impact of a flipped classroom approach on student learning experience. Computers & Education 2019, 128, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M. I.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Flipped classroom in higher education: a systematic literature review and research challenges. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2023, 20(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baingana, J. K. The impact of flipped classroom models on K-12 education in African countries, 2024.

- Bergmann, J.; Sams, A. Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day; International Society for Technology in Education, 2012; pp. 120–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J. L.; Verleger, M. A. The flipped classroom: A Survey of the research. In 120th ASEE National Conference and Exposition, Atlanta, GA (Paper ID 6219); American Society for Engineering Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C. R. Sample size for qualitative research. QM Research 2016, 19(4), 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevikbas, M.; Kaiser, G. Student engagement in a flipped secondary mathematics classroom. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 2022, 20(7), 1455–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, A. Data protection and anonymity considerations for equality research and data; Advance HE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. R.; Vealé, B. L. Strategies to enhance data collection and analysis in qualitative research. Radio. Tech. 2018, 89(5), 482CT–485CT. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research methods in education, 8th ed.; Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L. T. Using frequent, unannounced, focused, and short classroom observations to support classroom instruction . Doctoral Thesis, National Louis University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publication 2021, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, L.; Mohamed, H. B. Enhancing student motivation in a flipped classroom: An investigation of innovative teaching strategies to improve student learning. Education Administration: Theory and Practice 2023, 29(2), 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhlamini, J. J.; Mogari, D. Using a cognitive load theory to account for the enhancement of high school learners’ mathematical problem-solving skills. In Proceedings of the ISTE 2011 International Conference: Towards Effective Teaching and Meaningful Learning in MST; October 2011; pp. 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X. Application of flipped classroom in college English teaching. Creative Education 7 2016, 1335–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drijvers, P.; Sinclair, N. The role of digital technologies in mathematics education: Purposes and perspectives. ZDM–Mathematics Education 2024, 56(2), 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efiuvwere, R. A.; Fomsi, E. F. Flipping the mathematics classroom to enhance senior secondary students’ interest. International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology 2019, 65(2), 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egara, F. O.; Mosimege, M. Effect of flipped classroom learning approach on mathematics achievement and interest among secondary school students. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29(7), 8131–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egugbo, C. C.; Salami, A. T. Policy analysis of the 6–3-3–4 policy on education in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 2021, 23(1), 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ertesvåg, S. K.; Sammons, P.; Blossing, U. Integrating data in a complex mixed-methods classroom interaction study. British Educational Research Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperanza, P. J.; Himang, C.; Bongo, M.; Selerio, E., Jr.; Ocampo, L. The utility of a flipped classroom in secondary Mathematics education. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology 2023, 54(3), 382–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Estriegana, R.; Medina-Merodio, J. A.; Barchino, R. Analysis of competence acquisition in a flipped classroom approach. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 2019, 27(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, Y. N.; Chandler, K. L. Structured observation instruments assessing instructional practices with gifted and talented students: A review of the literature. Gifted Child Quarterly 2018, 62(3), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassett, K. T.; Wolcott, M. D.; Harpe, S. E.; McLaughlin, J. E. Considerations for writing and including demographic variables in education research. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 2022, 14(8), 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN) National Policy on Education, 6th ed.; NERDC Press, 2013.

- Gillmor, S. C.; Poggio, J.; Embretson, S. Effects of reducing the cognitive load of mathematics test items on student performance. Numeracy 2015, 8(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granström, M.; Kikas, E.; Eisenschmidt, E. Classroom observations: How do teachers teach learning strategies? In Frontiers in Education. In Frontiers Media SA; March 2023; Vol. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, D.; Wildavsky, A. The open-ended, semi-structured interview: An (almost) operational guide. In Craftways; Routledge, 2018; pp. 57–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W. K.; Chan, P. S. On the efficacy of flipped classroom: Motivation and cognitive load. In Developing 21st century competencies in the mathematics classroom: Yearbook 2016, Association of Math. Educators; 2016; pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. R.; Reinke, W. M.; Herman, K. C.; David, K. An examination of teacher engagement in intervention training and sustained intervention implementation. School Mental Health 2022, 14(1), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illowsky, B.; Dean, S. Introductory statistics; OpenStax College, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A. Reliability, Cronbach’s alpha. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of communication research methods; SAGE Publications, Inc, 2017; Vol. 4, pp. 1415–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G. B. Student perceptions of the flipped classroom. Master’s dissertation, University of British Columbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kissi, P. S. Proposed flipped classroom model for high schools in developing countries. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences 2017, 4(4), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. L.; Hwang, G. J. A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students’ learning performance in a mathematics course. Computers & Education 2016, 100, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, W.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory, resource depletion and the delayed testing effect. Educational Psychology Review 31 2019, 457–478. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-019-09476-2. [CrossRef]

- Lindorff, A.; Sammons, P. Going beyond structured observations: Looking at classroom practice through a mixed method lens. ZDM–Mathematics Education 50 2018, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K.; Hew, K. F. A critical review of flipped classroom challenges in K-12 education: Possible solutions and recommendations for future research. Research and Practice in Technology-Enhanced Learning 2017, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K.; Hew, K. F. Student engagement in mathematics flipped classrooms: Implications of journal publications from 2011 to 2020. Frontiers in Psychology 12 2021, 672610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Exploration of flipped classroom approach to enhance critical thinking skills. Heliyon 2023, 9(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi, D.; Berler, M. Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. K., Eds.; Semi-structured interviews. In Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences; Springer, 2020; pp. 4825–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, S. O. Impact of flipped classroom on mathematics learning outcome of senior secondary school students in Lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Teacher Education 2020, 9(2), 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, A. M.; Lawson, A. P.; Robinson, D. H. How scientific is cognitive load theory research compared to the rest of educational psychology? Education Sciences 2024, 14(8), 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenaghan, E. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test. Informatics. 14 May 2024. Available online: https://www.technologynetworks.com/informatics/articles/the-wilcoxon-signed-rank-test-370384.

- Modeste, S.; Giménez, J.; Lupiáñez Gómez, J. L.; Carvalho e Silva, J.; Nguyen, T. N. Coherence and relevance relating to mathematics and other disciplines. In Mathematics curriculum reforms around the world: The 24th ICMI study; Springer, 2023; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, T. Self-determination theory and the flipped classroom: A case study of a senior secondary mathematics class. Mathematics Education Research Journal 2021, 33(3), 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nooijen, C. C.; de Koning, B. B.; Bramer, W. M.; Isahakyan, A.; Asoodar, M.; Kok, E.; Paas, F. A cognitive load theory approach to understanding expert scaffolding of visual problem-solving tasks: A scoping review. Educational Psychology Review 2024, 36(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, L. Moore, E., Dooly, M., Eds.; Doing research with teachers. In Qualitative approaches to research on plurilingual education; 2017; pp. 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, D.; Davies, A.; Joubert, M.; Lyakhova, S. Exploring teachers’ and students’ responses to the use of a flipped classroom teaching approach in mathematics. Proceedings of the BSRLM, King’s College. London 2018, 38(3), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Olakanmi, E. E. The effects of a flipped classroom model of instruction on students’ performance and attitudes towards chemistry. Journal of Science Education and Technology 26 2017, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölmefors, O.; Scheffel, J. High school student perspectives on flipped classroom learning. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 2021, 31(4), 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; van Merriënboer, J. J. Cognitive-load theory: Methods to manage working memory load in the learning of complex tasks. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2020, 29(4), 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refugio, C. N.; Bulado, M. I. E. A.; Galleto, P. G.; Dimalig, C. Y.; Colina, D. G.; Inoferio, H. V.; Nocete, M. L. R. Difficulties in teaching senior high school general mathematics: Basis for training design. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences 2020, 15(2), 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, S. An Investigation into the Effects of Flipped Classroom Teaching Model on EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Knowledge. Master’s dissertation, Ministry of Higher Education, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, M. F.; Yahaya, L. A.; Adewara, A. A. Mathematics education in Nigeria: Gender and spatial dimensions of enrolment. International Journal of Embedded Systems 3 2011, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, H. Students' Experiences in a Mathematics Analysis Flipped Classroom. Master’s Dissertation, Chapman University, California, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Kingdom Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test Calculator. n.d. Available online: https://www.statskingdom.com/175wilcoxon_signed_ranks.html.

- Strohmyer, D. A. Student perceptions of flipped learning in a high school maths classroom. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S. W.; Evans, P.; Martin, A. J. Load reduction instruction: Exploring its applicability in a Chinese-speaking secondary school context. Teaching and Teacher Education 148 2024, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science 1988, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, C. A.; Nasri, N. M. The role of the flipped learning in the English language learning and students’ motivation: A systematic review. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 2022, 11(2), 1122–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarusha, F.; Bushi, J. The role of classroom observation, its impact on improving teacher’s teaching practices. European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences 2024, 2(2), 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Willig, C., W., S. Rogers, Eds.; Thematic analysis. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, L.; Evans, N. S.; Doyle, T.; Skamp, K. Are first year students ready for a flipped classroom? A case for a flipped learning continuum. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2019, 16(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpong, J. S.; Alabekee, C.; Ugwumba, E.; Ed, M. The challenges and prospects in the implementation of the National Education System: The case of 9-3-4. The Pacific Journal of Science and Technology 2023, 24(1), 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Unterhalter, E. Measuring education for the millennium development goals: Reflections on targets, indicators, and a post-2015 framework. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 2014, 15(2–3), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, N. H. A.; Tan, C. K.; Lee, K. W. Students' perceived challenges of attending a flipped EFL classroom in Viet Nam. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 2018, 8(11), 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Halili, S. Flipped classroom research and trends from different fields of study. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2016, 17(3), 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegenfuss, J. Y.; Easterday, C. A.; Dinh, J. M.; JaKa, M. M.; Kottke, T. E.; Canterbury, M. Impact of demographic survey questions on response rate and measurement: A randomized experiment. Survey Practice 2021, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

S/N |

Questionnaire Items |

Responses | |||

| SA | A | D | SD | ||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 1. | Each student got self-paced pre-class materials: video lessons, worked-out examples and worksheets. | 123 | 38 | 22 | 59 |

| 2. | I got sufficient, supportive instructions from my teacher that enabled me to engage well with the pre-class tasks. | 62 | 87 | 58 | 35 |

| 3. | I spent quality time studying pre-class learning materials at home before the in-class activities. | 64 | 91 | 26 | 61 |

| 4. | Seating arrangement and student grouping supported effective flipped classroom | 132 | 44 | 39 | 27 |

| 5. | I participated well in in-class tasks: discussions, group work, and collaborative problem solving. | 59 | 64 | 53 | 66 |

| 6. | The teacher elaborated on video lesson content and worked examples and clarified difficult mathematical concepts during in-class session. | 87 | 71 | 52 | 32 |

| 7. | The pre-class resources I explored at home facilitated my understanding of vital mathematics concepts during in-class discussions. | 54 | 38 | 83 | 67 |

| 8. | The flipped-classroom approach greatly engaged and motivated me to learn. | 57 | 48 | 64 | 73 |

| 9. | A flipped classroom allows efficient use of class time, improving students’ understanding. | 47 | 52 | 86 | 57 |

| 10. | Flipped learning of mathematics poses some challenges, e.g. it requires much effort and time. | 169 | 36 | 16 | 21 |

| 11. | Generally, my flipped mathematics classroom experience is more exciting and rewarding than that of traditional teaching methods that my class adopted in the past terms. | 51 | 27 | 78 | 86 |

| 12. | I recommend the use of the flipped classroom for future mathematics lessons. | 43 | 32 | 76 | 91 |

| S/N | Questionnaire Items | SA | A | D | SD | T |

| 1. | Each student got self-paced pre-class materials: video lessons, worked-out examples and worksheets. | 492 | 114 | 44 | 59 | 709 |

| 2. | I got sufficient instructions from my teacher that enabled me to engage well with the pre-class tasks. | 248 | 261 | 116 | 35 | 660 |

| 3. | I spent quality time studying the pre-class learning materials outside of class before the in-class activities. | 256 | 273 | 52 | 61 | 642 |

| 4. | Seating arrangement and student grouping supported effective flipped classroom | 528 | 132 | 78 | 27 | 765 |

| 5. | I participated well in in-class tasks: discussions, group work, and collaborative problem solving. | 236 | 192 | 106 | 66 | 600 |

| 6. | The teacher elaborated on video lesson content and worked examples and clarified difficult mathematical concepts during in-class session. | 348 | 213 | 104 | 32 | 697 |

| 7. | The pre-class resources I explored at home facilitated my understanding of vital mathematics concepts during in-class discussions. | 216 | 114 | 166 | 67 | 563 |

| 8. | The flipped-classroom approach greatly engaged and motivated me to learn. | 228 | 144 | 128 | 73 | 523 |

| 9. | A flipped classroom allows efficient use of class time, improving students’ understanding. | 188 | 156 | 172 | 57 | 573 |

| 10. | Flipped learning of mathematics poses some challenges, e.g. it requires much effort and time. | 676 | 108 | 32 | 21 | 837 |

| 11. | Generally, my flipped mathematics classroom experience is more exciting and rewarding than that of traditional teaching methods that my class adopted in the past terms. | 204 | 81 | 156 | 86 | 527 |

| 12. | I recommend the use of the flipped classroom for future mathematics lessons. | 172 | 96 | 152 | 91 | 511 |

|

Items |

Questionnaire-items |

Responses | |||

| SA | A | D | SD | ||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 1. | Each student got self-paced pre-class materials: video lessons, worked-out examples and worksheets. | 226 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. | I got sufficient, supportive instructions from my teacher that enabled me to engage well with the pre-class tasks. | 91 | 119 | 32 | 0 |

| 3. | I spent quality time studying the pre-class learning materials at home before the in-class activities. | 81 | 122 | 31 | 8 |

| 4. | Seating arrangement and student grouping supported effective flipped classroom | 206 | 30 | 6 | 0 |

| 5. | I participated well in in-class tasks: discussions, group work, and collaborative problem solving. | 212 | 24 | 6 | 0 |

| 6. | The teacher elaborated on video lesson content and worked examples and clarified difficult mathematical concepts during in-class session. | 218 | 16 | 6 | 2 |

| 7. | The pre-class resources I explored at home facilitated my understanding of vital mathematics concepts during in-class discussions. | 190 | 36 | 10 | 6 |

| 8. | The flipped-classroom approach greatly engaged and motivated me to learn. | 176 | 36 | 19 | 11 |

| 9. | A flipped classroom allows efficient use of class time, improving students’ understanding. | 196 | 21 | 15 | 10 |

| 10. | Flipped learning of mathematics poses some challenges, e.g. it requires much effort and time. | 108 | 134 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. | Generally, my flipped mathematics classroom experience is more exciting and rewarding than that of traditional teaching methods that my class earlier adopted. | 206 | 18 | 9 | 9 |

| 12. | I recommend the use of the flipped classroom for future mathematics lessons. | 200 | 28 | 8 | 6 |

| S/N | Questionnaire-items | SA | A | D | SD | Total |

| 1. | Each student got self-paced pre-class materials: video lessons, worked-out examples and worksheets. | 904 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 952 |

| 2. | I got sufficient, supportive instructions from my teacher that enabled me to engage well with pre-class tasks. | 364 | 357 | 64 | 0 | 785 |

| 3. | I spent quality time studying the pre-class learning materials at home before the in-class activities. | 324 | 366 | 62 | 8 | 760 |

| 4. | The seating arrangement and student grouping supported effective flipped classroom activities. | 824 | 90 | 12 | 0 | 926 |

| 5. | I participated well in in-class tasks: discussions, group work, and collaborative problem solving. | 848 | 72 | 12 | 0 | 932 |

| 6. | The teacher elaborated on video lesson content and worked examples and clarified difficult mathematics concepts during in-class session. | 872 | 48 | 12 | 2 | 934 |

| 7. | The pre-class resources I explored at home facilitated my understanding of complex mathematics concepts during in-class discussions. | 760 | 108 | 20 | 6 | 894 |

| 8. | The flipped-classroom approach greatly engaged and motivated me to learn. | 704 | 108 | 38 | 22 | 872 |

| 9. | A flipped classroom allows efficient use of class time, improving students’ understanding | 784 | 63 | 30 | 10 | 887 |

| 10. | Flipped learning of maths poses some challenges e.g. it requires much effort and time | 432 | 402 | 0 | 0 | 834 |

| 11. | Generally, my flipped mathematics classroom experience is more exciting and rewarding than that of traditional teaching methods that my class earlier adopted. | 824 | 54 | 18 | 9 | 905 |

| 12. | I recommend the use of the flipped classroom for future mathematics lessons. | 800 | 84 | 16 | 6 | 906 |

| Variable | n | Mean | Median | SD | Min. | Max. | Range | Q1 | Q3 | Coefficient of Variation. |

| Initial-FC Experience | 242 | 633.92 | 621 | 103.36 | 511 | 837 | 326 | 545 | 703 | 0.1631 |

| Post-FC Experience | 242 | 882.25 | 899.5 | 60.31 | 760 | 952 | 192 | 853 | 929 | 0.0684 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ids, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).