Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Processing

2.2. Models Construction and Changes in Ecological Niches

2.3. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities

3. Results

3.1. Model Precision Assessment

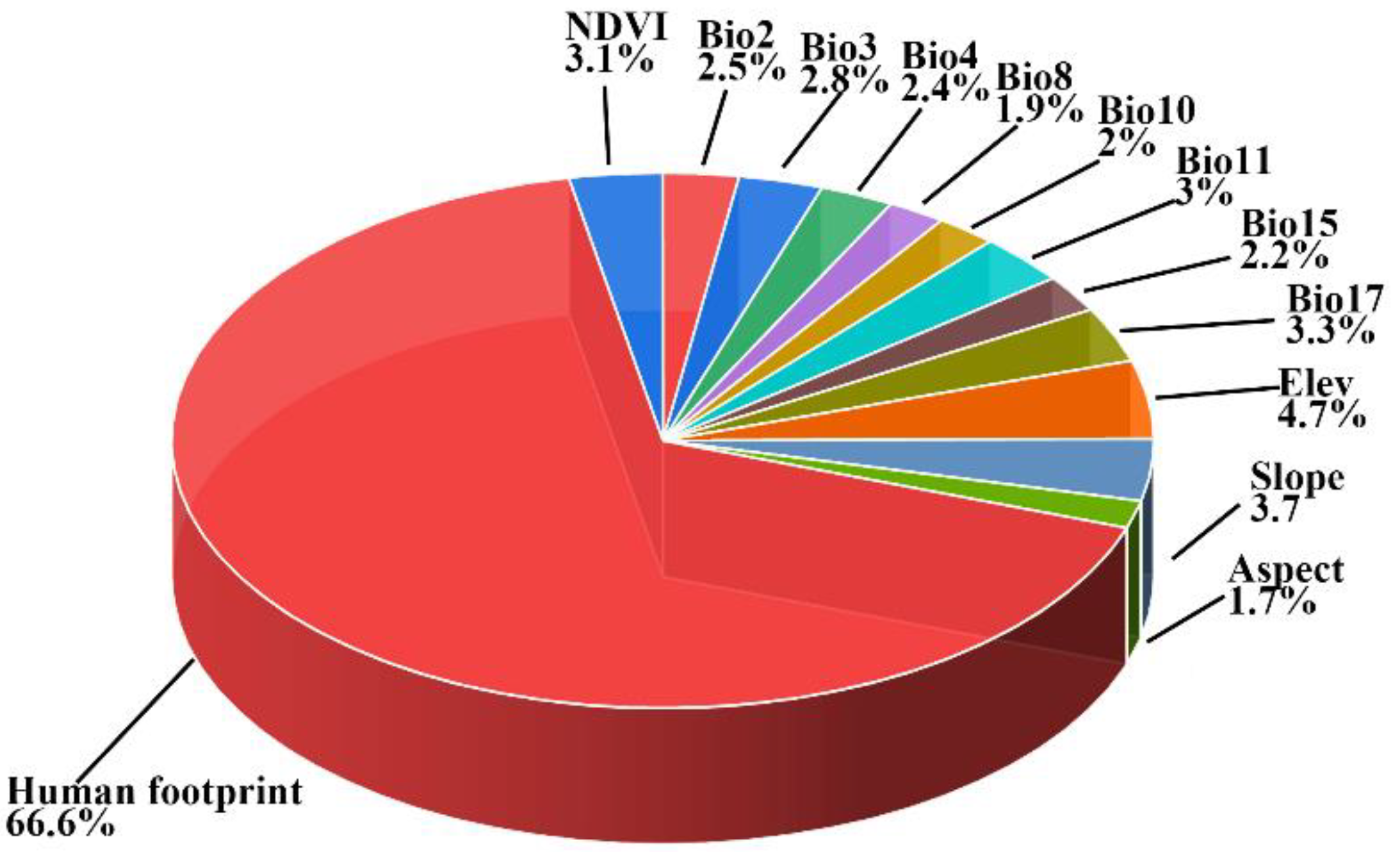

3.2. Bioclimatic Variable Contribution

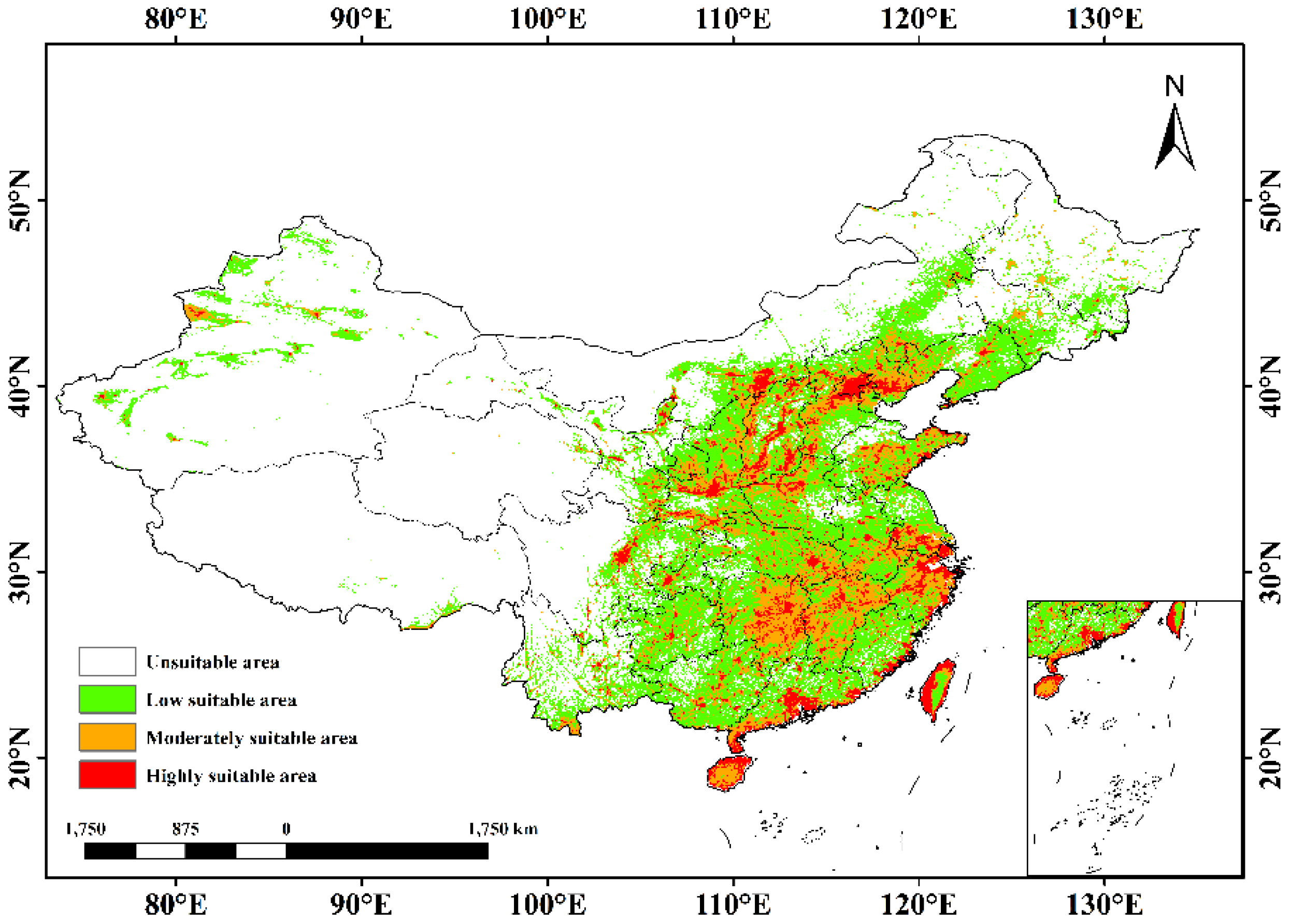

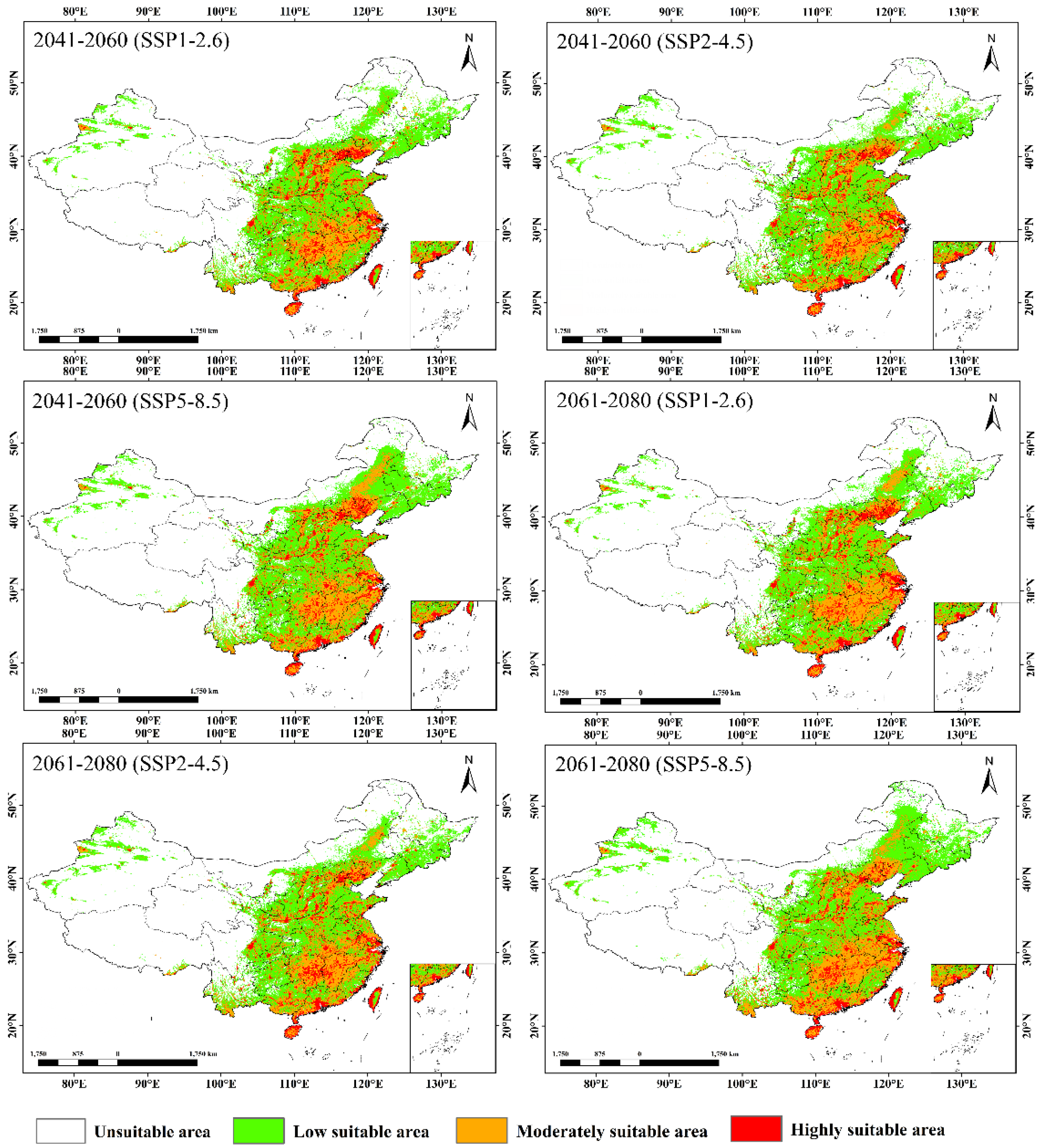

3.3. Present Potential Geographic Spread

3.4. Niche Dynamics

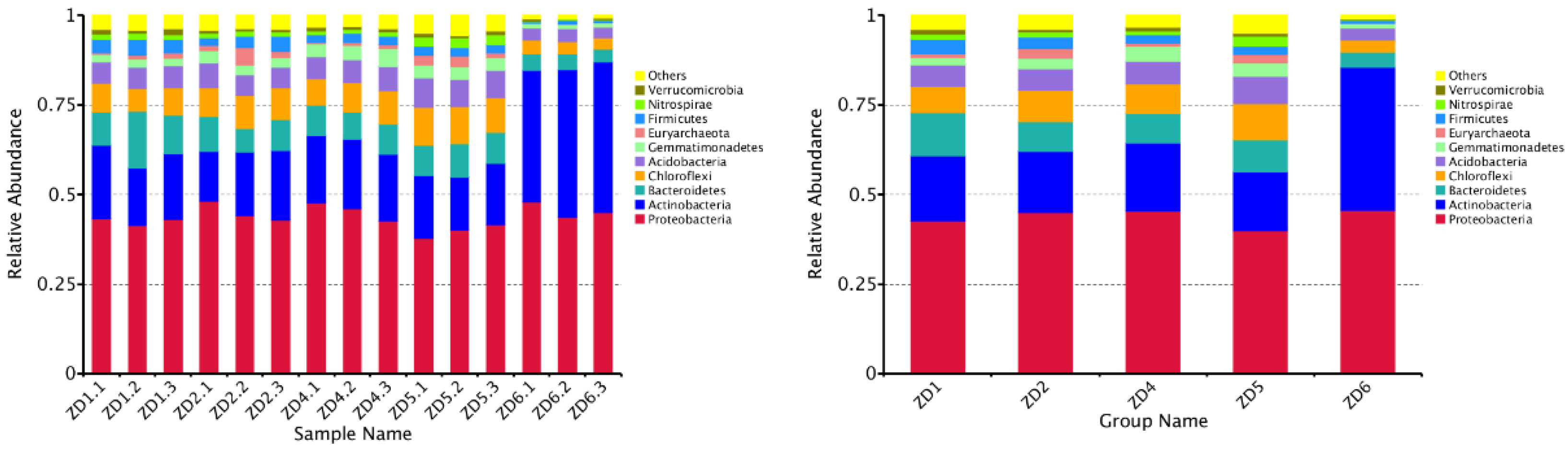

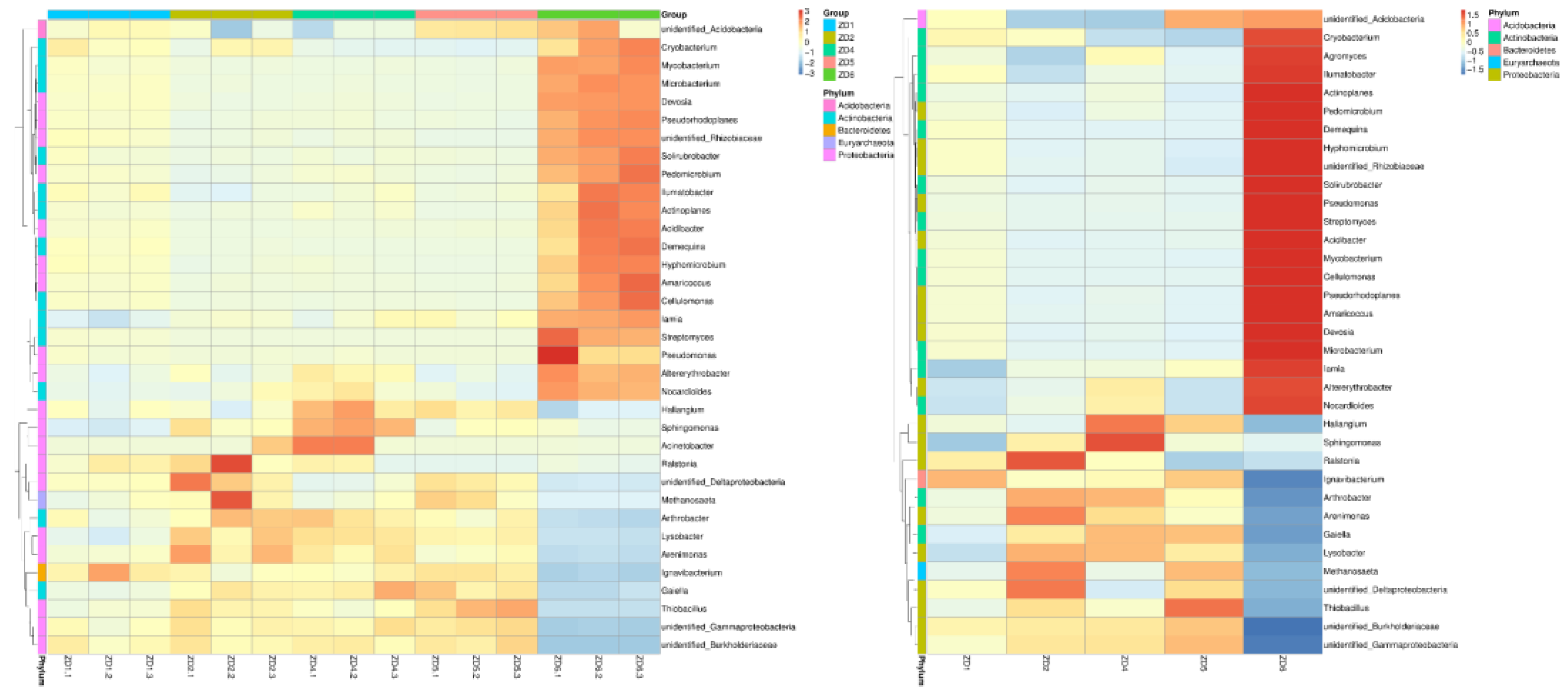

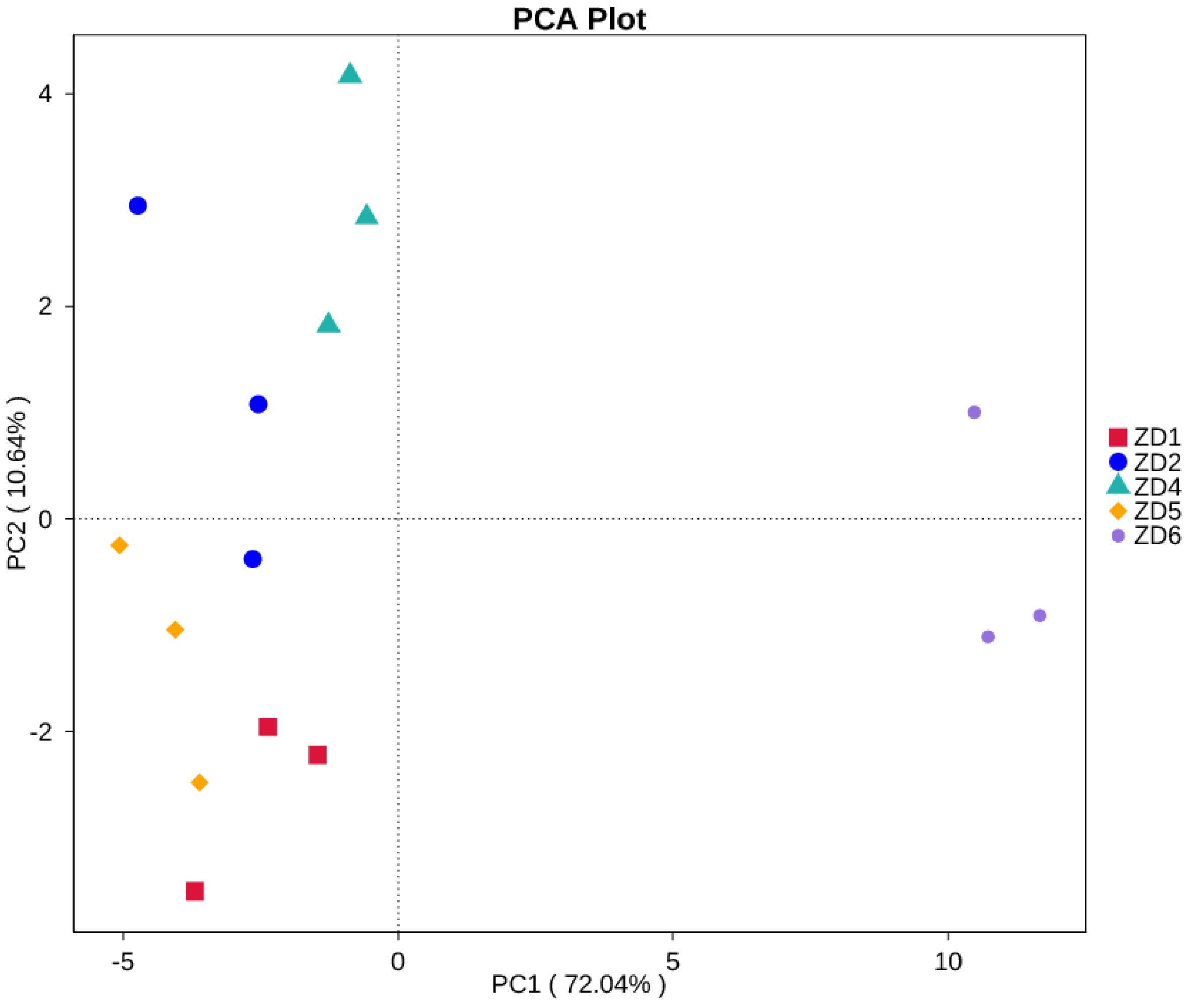

3.5. Rhizosphere Microbial Abundance in Xanthium strumarium Habitats

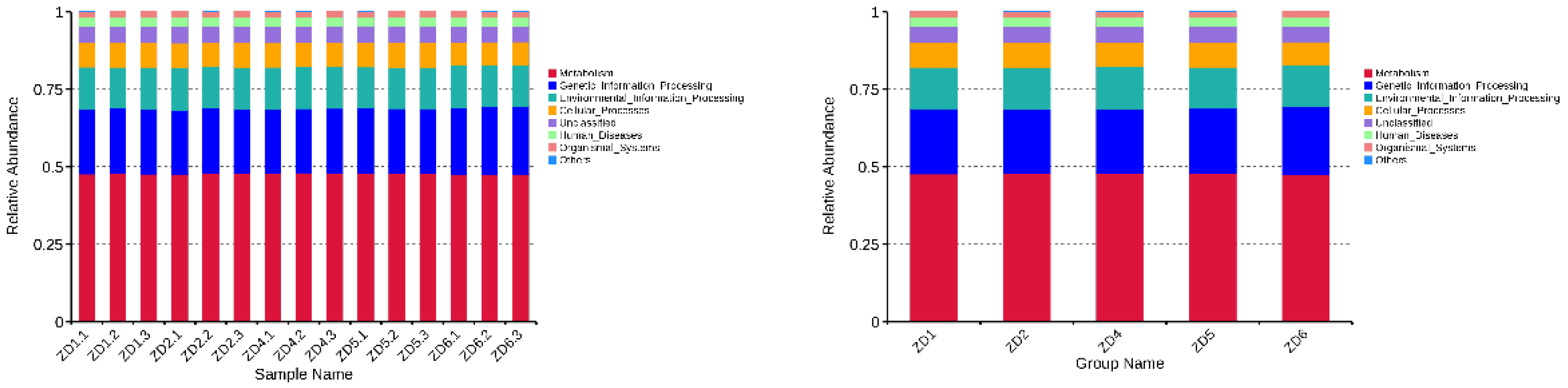

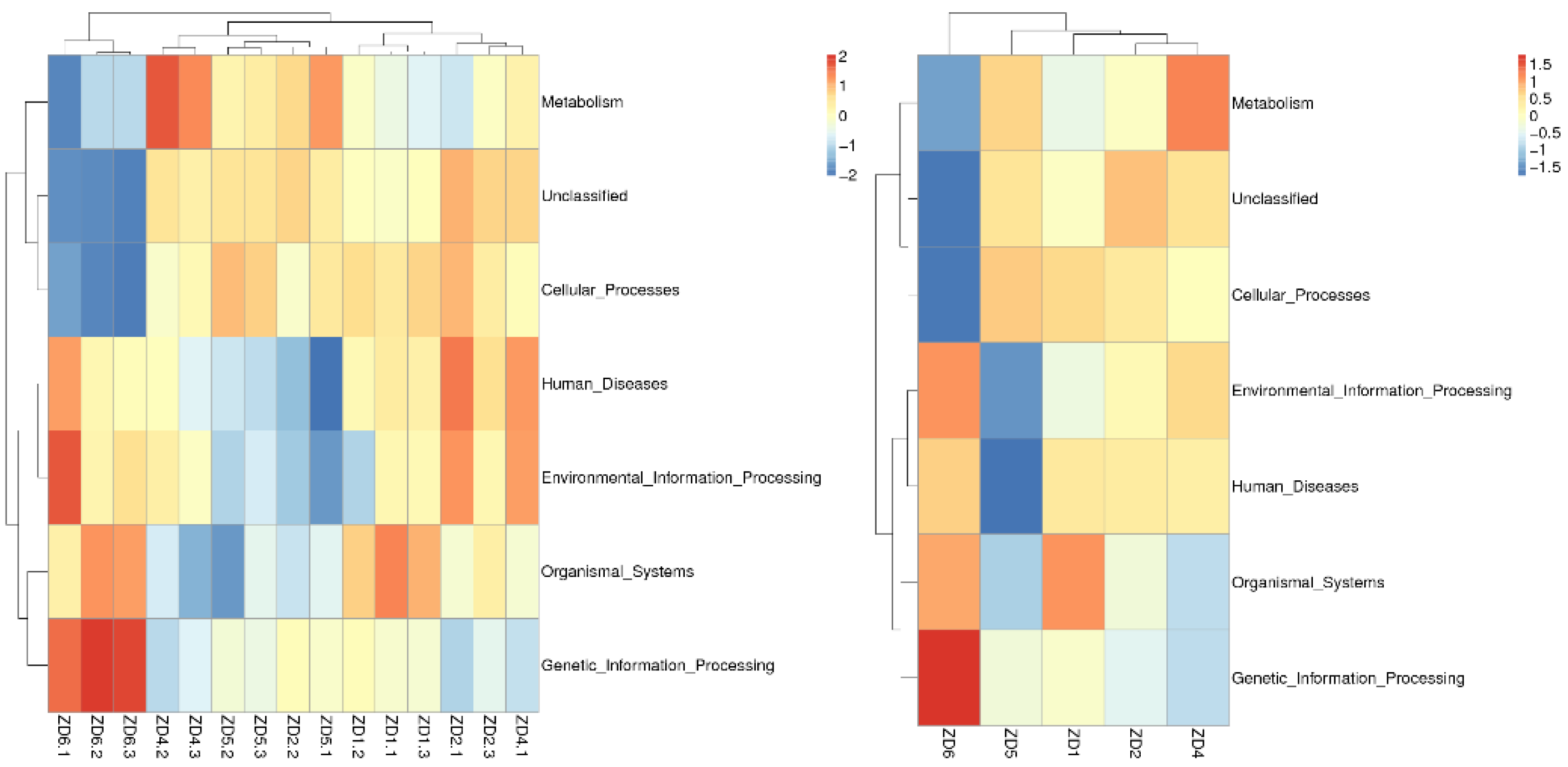

3.6. Functional Prediction of Soil Microorganisms

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Climate Change on Habitat Distribution of Xanthium strumarium

4.2. Role of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities in Adaptation

4.3. Uncertainties of the Present Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandh, S.A.; Shafi, S.; Peerzada, M.; Rehman, T.; Bashir, S.; Wani, S.A.; Dar, R. Multidimensional analysis of global climate change: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 24872–24888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Bruno, J.F. The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science 2010, 328, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.-C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, N. Enviornmental Challenges in the 21 St Century. Strategic Studies 2008, 28, 118–143. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Butt, N.; Maron, M.; McAlpine, C.A.; Chapman, S.; Ullmann, A.; Segan, D.B.; Watson, J.E. Conservation implications of ecological responses to extreme weather and climate events. Diversity and Distributions 2019, 25, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C.; Root, T.L.; Willig, M.R. Impacts of extreme weather and climate on terrestrial biota. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2000, 81, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Calder, W.J.; Cumming, G.S.; Hughes, T.P.; Jentsch, A.; LaDeau, S.L.; Lenton, T.M.; Shuman, B.N.; Turetsky, M.R.; Ratajczak, Z. Climate change, ecosystems and abrupt change: science priorities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2020, 375, 20190105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Timmis, J.; Verstraete, W.; Casadevall, A.; Ramos, J.L.; Sood, U.; Kumar, R.; Hira, P.; Dogra Rawat, C. Weaponising microbes for peace. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 1091–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.; Chan, K.M. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Terrer, C.; Zelfde, M.v.t.; McCallum, I.; Luke McCormack, M.; Fisher, J.B.; Brundrett, M.C.; de Sá, N.C.; Tedersoo, L. Global mycorrhizal plant distribution linked to terrestrial carbon stocks. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Fan, L.; Peng, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicology of Xanthium strumarium L.: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, C. Photoperiodic adaptation of Xanthium strumarium in Europe, Asia Minor, and northern Africa. Canadian Journal of Botany 1974, 52, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Khan, N.; Hewitt, N.; Ali, K.; Jones, D.A.; Khan, M.E.H. Invasive Species as Rivals: Invasive Potential and Distribution Pattern of Xanthium strumarium L. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.; Haq, S.M.; Arshad, F.; Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Bussmann, R.W.; Hashem, A.; Abd-Allah, E.F. Xanthium strumarium L., an invasive species in the subtropics: prediction of potential distribution areas and climate adaptability in Pakistan. BMC ecology and evolution 2024, 24, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Wu, B.; Han, J.; Tan, N. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Xanthium species: a review. Phytochemistry Reviews 2025, 24, 773–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.E.; Lechowicz, M.J. THE BIOLOGY OF CANADIAN WEEDS.: 56. Xanthium strumarium L. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 1983, 63, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiyeva, R.T.; Litvinskaya, S.A. Phytocenotic, bioecological and invasive activity of the invasive species Xanthium strumarium L. in some districts of Azerbaijan. Plant & Fungal Research 2020, 3, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Iram, A.; Liu, M.C.; Feng, Y.L. Competitive approach of invasive cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium) with native weed species diversity in Northeast China. BioRxiv 2001. BioRxiv:2020.2001. 2017.910208. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Sandoval, J. Xanthium strumarium (common cocklebur). Forest 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, H.; Anwar, T.; Arshad, M.; Osunkoya, O.O.; Adkins, S. Impacts of Xanthium strumarium L. invasion on vascular plant diversity in Pothwar Region (Pakistan). Annali di Botanica 2019, 9, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wapshere, A. An ecological study of an attempt at biological control of Noogoora burr (Xanthium strumarium). Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1974, 25, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.-X.; Fu, C.-X.; Comes, H.P. Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: tracing the genetic imprints of Quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 2011, 59, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Plant diversity and conservation in China: planning a strategic bioresource for a sustainable future. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2011, 166, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, X.; Feng, G.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Corlett, R.T.; Hughes, A.C.; Pimm, S.; Schmid, B.; Shi, S. The global significance of biodiversity science in China: An overview. National Science Review 2021, 8, nwab032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Caruso, T. Soil microbial community responses to climate extremes: resistance, resilience and transitions to alternative states. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2020, 375, 20190112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evidente, A. Specialized metabolites produced by phytotopatogen fungi to control weeds and parasite plants. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.-T.; Su, W.-H. Weed management methods for herbaceous field crops: A review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J Gundale, M.; Kardol, P. Multi-dimensionality as a path forward in plant-soil feedback research. Journal of Ecology 2021, 109, 3446–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.W.; Baumert, V.; Carminati, A.; Germon, A.; Holz, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Peth, S.; Schlüter, S.; Uteau, D.; Vetterlein, D. From rhizosphere to detritusphere–Soil structure formation driven by plant roots and the interactions with soil biota. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2024, 109396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Rawat, V.; Kaur, J.; Bhagwat, S.; Arora Pandit, M.; Dogra Rawat, C. Deploying microbes as drivers and indicators in ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology 2023, 31, e13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, R.; Rai, S.; Bano, A.; Pathak, N.; Fujita, M.; Kumar, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Mechanistic insights of plant growth promoting bacteria mediated drought and salt stress tolerance in plants for sustainable agriculture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, M.; Wani, S.P. Rhizobacterial-plant interactions: strategies ensuring plant growth promotion under drought and salinity stress. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2016, 231, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P. Does plant—microbe interaction confer stress tolerance in plants: a review? Microbiological research 2018, 207, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and salinity stress responses and microbe-induced tolerance in plants. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11, 591911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Prakash, G.; Sharma, S.; Sinha, D.; Mishra, R. Role of microbes in alleviating abiotic stress in plants. Plant Sci. Today 2023, 10, 160–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.R.; Lucero, M.E.; Reyes-Vera, I.; Havstad, K.M. Do symbiotic microbes have a role in regulating plant performance and response to stress? Communicative & Integrative Biology 2008, 1, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G.; Khadka, R.; Doni, F.; Uphoff, N. Benefits to plant health and productivity from enhancing plant microbial symbionts. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 11, 610065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.T.; Zhang, L.; He, S.Y. Plant-microbe interactions facing environmental challenge. Cell host & microbe 2019, 26, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Soen, Y. Environmental disruption of host–microbe co-adaptation as a potential driving force in evolution. Frontiers in genetics 2014, 5, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, I.R.; Sendek, A.; Brosse, M.; Bach, P.M.; Baity-Jesi, M.; Bolliger, J.; Bollmann, K.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Donati, G.; Gebert, F. Linking human impacts to community processes in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. Ecology Letters 2023, 26, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, D.; Šímová, I.; Smyčka, J.; Bohdalková, E.; Toszogyova, A.; Okie, J.G. Biodiversity dynamics in the Anthropocene: how human activities change equilibria of species richness. Ecography 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Wang, W.; Nakagawa, S.; Liu, S.; Miao, X.; Yu, L.; Du, Z.; Abrahamczyk, S.; Arias-Sosa, L.A.; Buda, K. Ecological filtering shapes the impacts of agricultural deforestation on biodiversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024, 8, 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, A.; Marull, J.; Tello, E.; Cattaneo, C.; Coll, F.; Pons, M.; Infante-Amate, J.; Urrego-Mesa, A.; Fernández-Landa, A.; Vargas, M. The impacts of agricultural and urban land-use changes on plant and bird biodiversity in Costa Rica (1986–2014). Regional Environmental Change 2021, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.S.; Ramachandran, R.M.; Paul, O.; Thakur, P.K.; Ravan, S.; Behera, M.D.; Sarangi, C.; Kanawade, V.P. Anthropogenic land use and land cover changes—A review on its environmental consequences and climate change. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 2022, 50, 1615–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.; Arshad, F. Adaptive convergence and divergence underpin the diversity of Asteraceae in a semi-arid lowland region. Flora 2024, 317, 152554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipomho, J.; Tatsvarei, S.; Parwada, C.; Mashingaidze, A.B.; Rugare, J.T.; Mabasa, S.; Chikowo, R. Weed Types and Dynamics Associations with Catena Landscape Positions: Smallholder Farmers’ Knowledge and Perception in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Agronomy 2022, 2022, 2743090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros Ruas, R.; Costa, L.M.S.; Bered, F. Urbanization driving changes in plant species and communities–A global view. Global Ecology and Conservation 2022, 38, e02243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.S.; Kalyan, S.; Pathak, B. Impacts of urbanization and climate change on habitat destruction and emergence of zoonotic species. In Climate change and urban environment sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S.J.; Piczak, M.L.; Singh, N.J.; Åkesson, S.; Ford, A.T.; Chowdhury, S.; Mitchell, G.W.; Norris, D.R.; Hardesty-Moore, M.; McCauley, D. Animal migration in the Anthropocene: threats and mitigation options. Biological Reviews 2024, 99, 1242–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordham, D.A. Identifying species traits that predict vulnerability to climate change. Cambridge Prisms: Extinction 2024, 2, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald-Mortensen, C. The Climate-Biodiversity Nexus Reviewed: Navigating Tipping Points, Science-Based Targets & Nature-Based Solutions. J of Agri Earth & Environmental Sciences 3 (6), 01 2024, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J.G.; Smith, A.C.; Cullingham, C.I. Genetic rescue often leads to higher fitness as a result of increased heterozygosity across animal taxa. Molecular Ecology 2024, 33, e17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delnevo, N.; Piotti, A.; Carbognani, M.; van Etten, E.J.; Stock, W.D.; Field, D.L.; Byrne, M. Genetic and ecological consequences of recent habitat fragmentation in a narrow endemic plant species within an urban context. Biodiversity and Conservation 2021, 30, 3457–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P. The Impact of Climate Change on the Environment, Water Resources, and Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. Clim. Environ. Agric. Dev. : A Sustain. Approach Towards Soc. 2024, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Coumar, M.V. Sustainable soil resource management for food and nutritional security under changing climate scenario. Indian Journal of Agronomy 2023, 68, 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Beery, S.; Cole, E.; Parker, J.; Perona, P.; Winner, K. Species distribution modeling for machine learning practitioners: A review. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, 2021; pp. 329–348.

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R. Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annual review of ecology, evolution, and systematics 2009, 40, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, G.; Kotiyal, P.B.; Singh, H.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, N.; Malik, A.; Sojitra, A.; Singh, S. Predicting future climate change effects on biotic communities: A species distribution modeling approach. In Forests and Climate Change: Biological Perspectives on Impact, Adaptation, and Mitigation Strategies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 137–168. [Google Scholar]

- Barewar, H.; Buragohain, M.K.; Lama, S. Mapping the impact of Climate Change on eco-sensitive hotspots using species distribution modelling (SDM): gaps, challenges, and future perspectives. In Ecosystem and species habitat modeling for conservation and restoration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, Z. Predicting the potential suitable distribution of Larix principis-rupprechtii Mayr under climate change scenarios. Forests 2022, 13, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosyan, V.; Dinets, V.; Osipov, F.; Dergunova, N.; Khlyap, L. Range dynamics of striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) in Northern Eurasia under global climate change based on ensemble species distribution models. Biology 2023, 12, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, Z.A.; Ahmad, R.; Khuroo, A.A. Ensemble modelling enables identification of suitable sites for habitat restoration of threatened biodiversity under climate change: A case study of Himalayan Trillium. Ecological Engineering 2022, 176, 106534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavi, R.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Elith, J. Predictive performance of presence-only species distribution models: a benchmark study with reproducible code. Ecological monographs 2022, 92, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Zheng, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Fan, S. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the geographic distribution of moso bamboo in China based on biomod2 model. European Journal of Forest Research 2024, 143, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y. Analysis of the Distribution Pattern of Phenacoccus manihoti in China under Climate Change Based on the Biomod2 Model. Biology 2024, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W.; Zimmermann, N.E. Habitat suitability and distribution models: with applications in R; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, A.S.; Nikkel, E.; Clements, D.R.; DiTommaso, A. Modeling and managing invasive weeds in a changing climate. In Invasive species and global climate change; CABI GB: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cola, V.; Broennimann, O.; Petitpierre, B.; Breiner, F.T.; d'Amen, M.; Randin, C.; Engler, R.; Pottier, J.; Pio, D.; Dubuis, A. ecospat: an R package to support spatial analyses and modeling of species niches and distributions. Ecography 2017, 40, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Wan, Y.; Qin, S.; Ma, F. Assessing the Potential Distribution and Ecological Niche Dynamics of Invasive African Giant Snails (Lissachatina Fulica) Using a Structural Portfolio Approach.

- Grover, M.; Ali, S.Z.; Sandhya, V.; Rasul, A.; Venkateswarlu, B. Role of microorganisms in adaptation of agriculture crops to abiotic stresses. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2011, 27, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.; Peukert, M.; Succurro, A.; Koprivova, A.; Kopriva, S. The role of soil microorganisms in plant mineral nutrition—current knowledge and future directions. Frontiers in plant science 2017, 8, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.A.; Lennon, J.T. Rapid responses of soil microorganisms improve plant fitness in novel environments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 14058–14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; Newberger, D.; Vivanco, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Plant–microbial interactions for resource acquisition. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2022, 133, 2864–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemiel, C.; Maron, P.-A.; Terrat, S.; Dequiedt, S.; Cottin, A.; Ranjard, L. Inferring microbiota functions from taxonomic genes: a review. GigaScience 2022, 11, giab090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemheuer, F.; Taylor, J.A.; Daniel, R.; Johnston, E.; Meinicke, P.; Thomas, T.; Wemheuer, B. Tax4Fun2: prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environmental Microbiome 2020, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aßhauer, K.P.; Wemheuer, B.; Daniel, R.; Meinicke, P. Tax4Fun: predicting functional profiles from metagenomic 16S rRNA data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2882–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/download/0008537-241126133413365 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International journal of climatology 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildlife Conservation Society-WCS; Center For International Earth Science Information Network-CIESIN-Columbia University. Last of the wild project, version 2, 2005 (LWP-2): Global human footprint dataset (Geographic); NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC): Palisades, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xin, X.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Jie, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. The Beijing climate center climate system model (BCC-CSM): The main progress from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geoscientific Model Development 2019, 12, 1573–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Ge, X.; Tong-Wen, W.; Jie ZHANG, F.Z.; Wei-Ping, L.; Yan-Wu ZHANG, Y.-X.L.; Yong-Jie, F.; Wei-Hua, J.; Li ZHANG, M.D.; Xue-Li, S.; Jiang-Long, L. Introduction of BCC models and its participation in CMIP6. Advances in Climate Change Research 2019, 15, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Park, D.S.; Liang, Y.; Pandey, R.; Papeş, M. Collinearity in ecological niche modeling: Confusions and challenges. Ecology and evolution 2019, 9, 10365–10376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchions, E.; Francis, I.; Knoblauch, V.; Weinhagen, C. Can species distribution modelling improve the climate threat assessment of at-risk mosses in Canada? The University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, T.; Elith, J.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Guillera-Arroita, G. Testing whether ensemble modelling is advantageous for maximising predictive performance of species distribution models. Ecography 2020, 43, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xian, X.; Li, J.; Huang, H.; Yu, W.; Liu, W.-x. Estimation of climate-induced increased risk of Centaurea solstitialis L. invasion in China: An integrated study based on biomod2. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 11, 1113474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jia, H.; Hua, Q. Predicting suitable habitats of parasitic desert species based on Biomod2 ensemble model: Cynomorium songaricum rupr and its host plants as an example. BMC Plant Biology 2025, 25, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, N.; Ribeiro-Silva, J.; Arenas-Castro, S. Shifts in climatic realised niches of Iberian species. Oikos 2022, 2022, e08505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Lucas, L.R.; Montor-Antonio, J.J.; Cortés-López, N.G.; del Moral, S. Strategies for the extraction, purification and amplification of metagenomic DNA from soil growing sugarcane. Advances in Biological Chemistry 2014, 4, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbe-Espinoza, P.; Brandt, B.W.; Braster, M.; Bonte, M.; Brown, D.M.; van Spanning, R.J. Effects of DNA preservation solution and DNA extraction methods on microbial community profiling of soil. Folia Microbiologica 2021, 66, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnaughton, S.; Stephen, J.R.; Chang, Y.-J.; Peacock, A.; Flemming, C.A.; Leung, K.; White, D.C. Characterization of metal-resistant soil eubacteria by polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis with isolation of resistant strains. Canadian journal of microbiology 1999, 45, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekeç, M.; Kadıoğlu, İ. İklim Değişikliğine Bağlı Olarak Xanthium strumarium L.’un Türkiye'de Gelecekte Dağılım Alanlarının Belirlenmesi. Turkish Journal of Weed Science 2020, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chikuruwo, C.; Masocha, M.; Murwira, A.; Ndaimani, H. Predicting the suitable habitat of the invasive Xanthium strumarium L. In southeastern Zimbabwe. Applied ecology and environmental research 2017, 15, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecours, V.; Brown, C.J.; Devillers, R.; Lucieer, V.L.; Edinger, E.N. Comparing selections of environmental variables for ecological studies: A focus on terrain attributes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Jo, H.Y.; Finneran, K.T.; Kwon, M.J. Diversity and composition of soil Acidobacteria and Proteobacteria communities as a bacterial indicator of past land-use change from forest to farmland. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 797, 148944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C. The rhizosphere microbiome and its influence on the accumulation of metabolites in Bletilla striata (Thunb.) Reichb. f. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Smalla, K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS microbiology ecology 2009, 68, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Dong, M.; Yu, L.; Kong, L.; Seviour, R.; Kong, Y. Compositional and functional profiling of the rhizosphere microbiomes of the invasive weed Ageratina adenophora and native plants. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.P.; Kiers, E.T.; Driessen, G.; Van Der HEIJDEN, M.; Kooi, B.W.; Kuenen, F.; Liefting, M.; Verhoef, H.A.; Ellers, J. Adapt or disperse: understanding species persistence in a changing world. Global Change Biology 2010, 16, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Albert, C.; Araújo, M.B.; Berry, P.M.; Cabeza, M.; Guisan, A.; Hickler, T.; Midgley, G.F.; Paterson, J.; Schurr, F.M. Predicting global change impacts on plant species’ distributions: future challenges. Perspectives in plant ecology, evolution and systematics 2008, 9, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate | Bio2 | Mean diurnal range | °C |

| Bio3 | Isothermality | \ | |

| Bio4 | Temperature seasonality | \ | |

| Bio8 | Mean temperature of wettest quarter | °C | |

| Bio10 | Mean temperature of warmest quarter | °C | |

| Bio11 | Mean temperature of coldest quarter | °C | |

| Bio15 | Precipitation seasonality | \ | |

| Bio17 | Precipitation of driest quarter | mm | |

| Topography | Elev | Elev | m |

| Aspect | Aspect | ° | |

| Slope | Slope | ° | |

| Human | Human footprint | Human footprint | \ |

| Vegetation | NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index | \ |

| Site | Location | Coordinates | Habitat Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZD1 | Yematu Village, Xincheng District, Hohhot | 111°51′48.194″E, 40°55′52.378″N | Farmland Edge |

| ZD2 | Hadamen National Forest Park | 111°35′18.977″E, 41°01′04.115″N | Montane Forest |

| ZD4 | Saihanwula National Nature Reserve | 118°39′40.185″E, 44°15′41.225″N | Temperate Steppe |

| ZD5 | East Campus, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University | 111°43′00.034″E, 40°49′03.373″N | Urban Green Space |

| ZD6 | Huanghuagou Grassland Cultural Resort | 112°32′06.128″E, 41°08′28.420″N | Grassland |

| Period | Climate Scenario | Low suitable area | Moderately suitable area | High suitable area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 198.70486 | 94.239585 | 36.871528 | |

| 2041-2060 | SSP1-2.6 | 214.12327 | 121.80209 | 47.453126 |

| SSP2-4.5 | 214.8698 | 122.04167 | 46.569445 | |

| SSP5-8.5 | 225.38889 | 134.07813 | 46.918404 | |

| 2061-2080 | SSP1-2.6 | 210.57292 | 127.92188 | 46.440973 |

| SSP2-4.5 | 209.90973 | 127.00695 | 46.953126 | |

| SSP5-8.5 | 228.59375 | 141.42361 | 46.119792 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).