Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

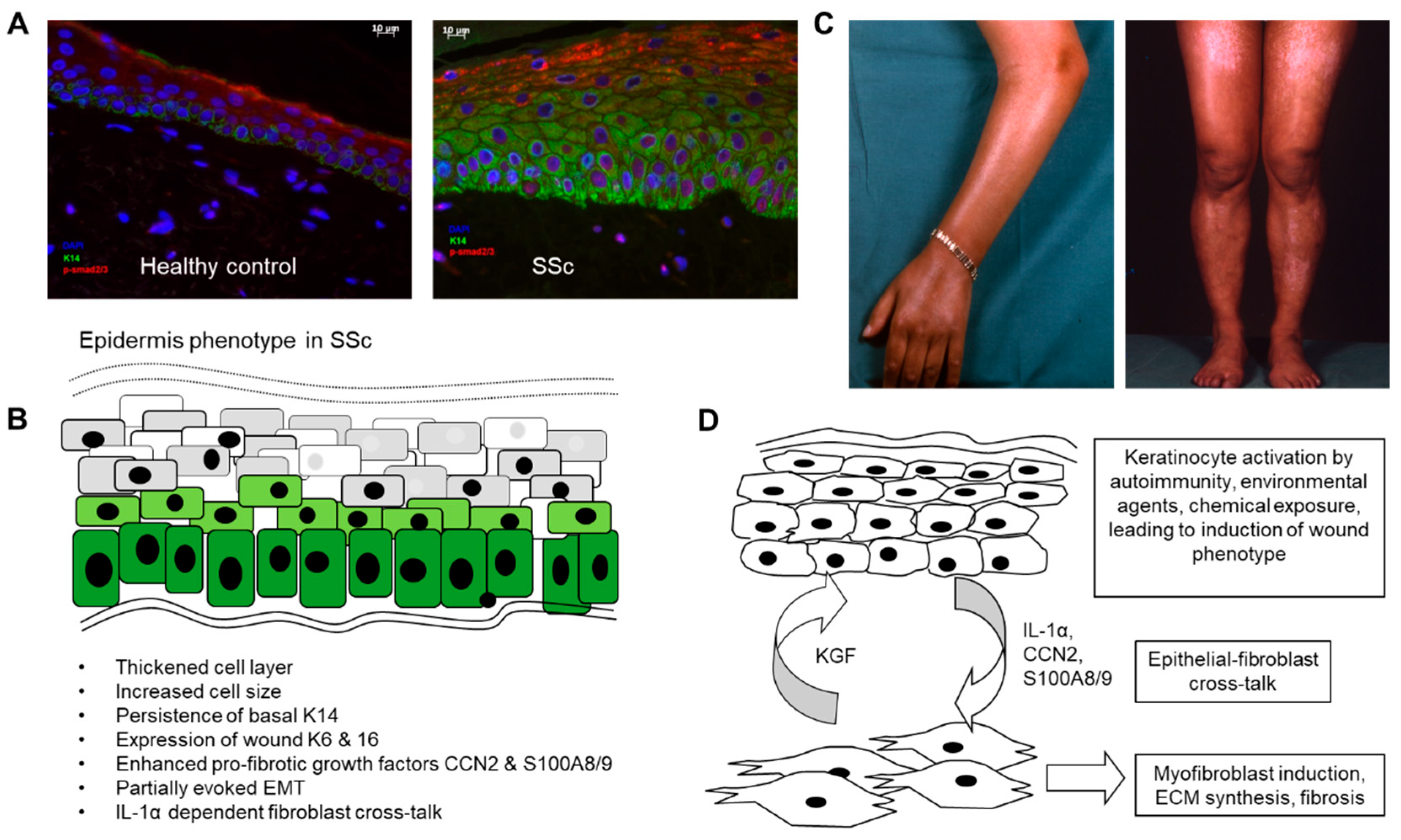

2. Altered Differentiation of the Epidermis in Scleroderma: Activated Wound Healing Phenotype

3. Release of Pro-Inflammatory and Pro-Fibrotic Factors by the SSc Epidermis

4. Cross-Talk and Transition Between Epithelial Cells and Mesenchymal Cells in SSc

References

- Denton, C.P.; Khanna, D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet (London, England) 2017, 390, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanore, Y.; Simms, R.; Distler, O.; Trojanowska, M.; Pope, J.; Denton, C.P.; Varga, J. Systemic sclerosis. Nature reviews Disease primers 2015, 1, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiwen, X.; Stratton, R.; Nikitorowicz-Buniak, J.; Ahmed-Abdi, B.; Ponticos, M.; Denton, C.; Abraham, D.; Takahashi, A.; Suki, B.; Layne, M.D.; et al. A Role of Myocardin Related Transcription Factor-A (MRTF-A) in Scleroderma Related Fibrosis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0126015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieb, G.; Bucala, R. Fibrocytes in Fibrotic Diseases and Wound Healing. Advances in wound care 2012, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, R.G.; Korman, B.D.; Wei, J.; Wood, T.A.; Graham, L.V.; Whitfield, M.L.; Scherer, P.E.; Tourtellotte, W.G.; Varga, J. Myofibroblasts in murine cutaneous fibrosis originate from adiponectin-positive intradermal progenitors. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 2015, 67, 1062–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsley, V. Adipocyte plasticity in tissue regeneration, repair, and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2022, 76, 101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, V.S.; Sundberg, C.; Abraham, D.J.; Rubin, K.; Black, C.M. Activation of microvascular pericytes in autoimmune Raynaud's phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and rheumatism 1999, 42, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, R.B.; Gilbane, A.J.; Trinder, S.L.; Denton, C.P.; Coghlan, G.; Abraham, D.J.; Holmes, A.M. Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition Contributes to Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. The American journal of pathology 2015, 185, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitorowicz-Buniak, J.; Denton, C.P.; Abraham, D.; Stratton, R. Partially Evoked Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Is Associated with Increased TGFbeta Signaling within Lesional Scleroderma Skin. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aden, N.; Shiwen, X.; Aden, D.; Black, C.; Nuttall, A.; Denton, C.P.; Leask, A.; Abraham, D.; Stratton, R. Proteomic analysis of scleroderma lesional skin reveals activated wound healing phenotype of epidermal cell layer. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2008, 47, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aden, N.; Nuttall, A.; Shiwen, X.; de Winter, P.; Leask, A.; Black, C.M.; Denton, C.P.; Abraham, D.J.; Stratton, R.J. Epithelial cells promote fibroblast activation via IL-1alpha in systemic sclerosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2010, 130, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitorowicz-Buniak, J.; Shiwen, X.; Denton, C.P.; Abraham, D.; Stratton, R. Abnormally differentiating keratinocytes in the epidermis of systemic sclerosis patients show enhanced secretion of CCN2 and S100A9. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2014, 134, 2693–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, J.S.; Tabib, T.; Xiao, H.; Sadej, G.M.; Khanna, D.; Fuschiotti, P.; Lafyatis, R.A.; Das, J. Cell Type-Specific Biomarkers of Systemic Sclerosis Disease Severity Capture Cell-Intrinsic and Cell-Extrinsic Circuits. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 2023. [CrossRef]

- Russo, B.; Borowczyk, J.; Boehncke, W.H.; Truchetet, M.E.; Modarressi, A.; Brembilla, N.C.; Chizzolini, C. Dysfunctional Keratinocytes Increase Dermal Inflammation in Systemic Sclerosis: Results From Studies Using Tissue-Engineered Scleroderma Epidermis. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 2021, 73, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, P.J.; Blackwell, T.S.; Eickelberg, O.; Loyd, J.E.; Kaminski, N.; Jenkins, G.; Maher, T.M.; Molina-Molina, M.; Noble, P.W.; Raghu, G.; et al. Time for a change: is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis still idiopathic and only fibrotic? The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2018, 6, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimon, T.; Yao, C.; Stripp, B.R.; Noble, P.W.; Chen, P. Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cells as Drivers of Lung Fibrosis in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. The role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2004, 82, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Krieg, T.; Smola, H. Keratinocyte-fibroblast interactions in wound healing. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2007, 127, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, F.M. Mammalian skin cell biology: at the interface between laboratory and clinic. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2014, 346, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, B.; Tewary, M.; Bremer, A.W.; Philippeos, C.; Negri, V.A.; Zijl, S.; Gartner, Z.J.; Schaffer, D.V.; Watt, F.M. A reductionist approach to determine the effect of cell-cell contact on human epidermal stem cell differentiation. Acta Biomater 2022, 150, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E.; Green, H. Changes in keratin gene expression during terminal differentiation of the keratinocyte. Cell 1980, 19, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yin, M.; Zhang, L.J. Keratin 6, 16 and 17-Critical Barrier Alarmin Molecules in Skin Wounds and Psoriasis. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, A.J.; Clark, R.A. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med 1999, 341, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, R.J.; Lantis, J.; Kirsner, R.S.; Shah, V.; Molyneaux, M.; Carter, M.J. Macrophages: A review of their role in wound healing and their therapeutic use. Wound Repair Regen 2016, 24, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Osumi, M.; Ohnishi, T.; Ichikawa, E.; Takahashi, H. Changes in cytokeratin expression in epidermal keratinocytes during wound healing. Histochemistry and cell biology 1995, 103, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, H.; Hara, N.; Otsuka, S.; Yamakage, A.; Yamazaki, S.; Koibuchi, N. Correlation between diffuse pigmentation and keratinocyte-derived endothelin-1 in systemic sclerosis. Int J Dermatol 2000, 39, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrot, P.; Pain, C.; Taieb, A.; Truchetet, M.E.; Cario, M. Dysregulation of CCN3 (NOV) expression in the epidermis of systemic sclerosis patients with pigmentary changes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2020, 33, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, J.S.; Gordon, J.K.; Steen, V.D. African American race associated with body image dissatisfaction among patients with systemic sclerosis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2016, 34 Suppl 100, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Abdi, B.; Lopez, H.; Karrar, S.; Renzoni, E.; Wells, A.; Tam, A.; Etomi, O.; Hsuan, J.J.; Martin, G.R.; Shiwen, X.; et al. Use of Patterned Collagen Coated Slides to Study Normal and Scleroderma Lung Fibroblast Migration. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piipponen, M.; Li, D.; Landen, N.X. The Immune Functions of Keratinocytes in Skin Wound Healing. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Quan, F.S.; Yoo, D.G.; Compans, R.W.; Kang, S.M.; Prausnitz, M.R. Improved influenza vaccination in the skin using vaccine coated microneedles. Vaccine 2009, 27, 6932–6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Smola, H. Paracrine regulation of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. Trends Cell Biol 2001, 11, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Shi-wen, X.; Abraham, D.J.; Leask, A. CCN2 is required for bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in mice. Arthritis and rheumatism 2011, 63, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafyatis, R. Transforming growth factor beta--at the centre of systemic sclerosis. Nature reviews. Rheumatology 2014, 10, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, S.S.; Reed, T.J.; Berthier, C.C.; Tsou, P.S.; Liu, J.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Khanna, D.; Kahlenberg, J.M. Scleroderma keratinocytes promote fibroblast activation independent of transforming growth factor beta. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2017, 56, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Tochimoto, A.; Ichikawa, N.; Harigai, M.; Hara, M.; Kotake, S.; Kitamura, Y.; Kamatani, N. Association of IL1A gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to and severity of systemic sclerosis in the Japanese population. Arthritis and rheumatism 2003, 48, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Harigai, M.; Suzuki, K.; Hara, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Ishizuka, T.; Matsuki, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Nakamura, H. Interleukin 1 receptor on fibroblasts from systemic sclerosis patients induces excessive functional responses to interleukin 1 beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993, 190, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantero, J.C.; Kishore, N.; Ziemek, J.; Stifano, G.; Zammitti, C.; Khanna, D.; Gordon, J.K.; Spiera, R.; Zhang, Y.; Simms, R.W.; et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of IL1-trap, rilonacept, in systemic sclerosis. A phase I/II biomarker trial. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2018, 36 Suppl 113, 146-149.

- Foell, D.; Wittkowski, H.; Vogl, T.; Roth, J. S100 proteins expressed in phagocytes: a novel group of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules. J Leukoc Biol 2007, 81, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 2009, 119, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, J.; Fitch, J.; Jacobsen, K.; Kumar, R.; Lafyatis, R.; Lemaire, R. Increased expression of Wnt2 and SFRP4 in Tsk mouse skin: role of Wnt signaling in altered dermal fibrillin deposition and systemic sclerosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2008, 128, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, I.; Mulipa, P.; Colato, C.; Abignano, G.; Ballarin, A.; Biasi, D.; Emery, P.; Ross, R.L.; Del Galdo, F. SFRP4 Expression Is Linked to Immune-Driven Fibrotic Conditions, Correlates with Skin and Lung Fibrosis in SSc and a Potential EMT Biomarker. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas-Szabowski, N.; Shimotoyodome, A.; Fusenig, N.E. Keratinocyte growth regulation in fibroblast cocultures via a double paracrine mechanism. Journal of cell science 1999, 112 ( Pt 12), 1843–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canady, J.; Arndt, S.; Karrer, S.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Increased KGF expression promotes fibroblast activation in a double paracrine manner resulting in cutaneous fibrosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2013, 133, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, D.; Savage, C.O.; Isenberg, D.; Pearson, J.D. IgG anti-endothelial cell autoantibodies from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or systemic vasculitis stimulate the release of two endothelial cell-derived mediators, which enhance adhesion molecule expression and leukocyte adhesion in an autocrine manner. Arthritis and rheumatism 1999, 42, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntyanu, A.; Milan, R.; Rahme, E.; Baron, M.; Netchiporouk, E.; Canadian Scleroderma Research, G. Organic solvent exposure and systemic sclerosis: A retrospective cohort study based on the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group registry. J Am Acad Dermatol 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; Denton, C.P.; Jahreis, A.; van Laar, J.M.; Frech, T.M.; Anderson, M.E.; Baron, M.; Chung, L.; Fierlbeck, G.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in adults with systemic sclerosis (faSScinate): a phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2016, 387, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).