1. Introduction

The pollution of our atmosphere with toxic gases such as NO

2, NH

3, H

2S and SO

2 is an unfortunate side effect of industrialisation and traffic in the modern world, particularly in the urban environment, and may be particularly intense in some workplaces. For example, NO

2 is generated by high-temperature combustion in air (Diesel engines, gas cookers), but it is also an intermediate in the synthesis of nitric acid, which is produced on a large scale in the fertiliser industry. NO

2 is, therefore, a common urban and indoor air pollutant causing serious health effects by long-term exposure to lower concentrations, but also poses an imminent danger to life from leaks in fertiliser plants, with a ‘median lethal dose’ LC

50 for humans of 174 parts- per- million (ppm) for 1 hr. All major legislations therefore set ‘limiting values’ (LVs) or ‘maximum exposure limits’ (MELs) for NO

2 and other toxic gases. These differentiate between environmental air quality, and the permitted exposure of individuals in the workplace, and typically are graded according to the duration of exposure. For example, the EU sets standards for environmental air quality of 200 μg/m

3 = 106 ppb NO

2 for a maximum of 1 hr, and 40 μg/m

3 = 21 ppb for ‘1 year’, i.e. permanent exposure [

1]. For the workplace, the EU Occupational Safety and Health Agency (OSHA) defines LVs for CO, SO

2, H

2S, NH

3, NO

2, and NO in Commission directive 2017/164 [

2]; values are tabulated in supplementary material S1. US legislation sets short term ‘emergency exposure limits’ (EELs) to NO

2 in the workplace between a ‘5-minute EEL’ of 35 ppm, and a 60-minute EEL of 10 ppm [

3].

The common pollution of air with the aforementioned 4 gases (as well as others) calls for sensor technologies for their identification and quantification. Sensors require a ‘sensitiser’, i.e. a material that binds to the target analyte and changes (at least) one of its physical properties in response, and a ‘transducer’ that measures the change of this physical quantity. A family of materials that are known to bind and respond to toxic and chemically aggressive gases are organic dyes and semiconductors, i.e. organic materials with extended π- conjugated electronic orbitals. Air- and waterborne pollutants often interact with organic dyes and semiconductors and change their optical (e.g. [

4]) and/or electronic properties, making them potential sensitisers for such pollutants. Historically, organic semiconductor based sensors often were transduced by organic field effect transistors, known as OFETs or OTFTs, which change their electronic characteristics in line with the semiconductor’s electronic properties. When the OFET is actuated by a gate voltage, field effect enhances charge carrier concentration in the transistor’s channel and therefore its conductivity by many orders- of- magnitude. This is helpful for measurement as charge carrier mobility in organic semiconductors often is low. Also, OFET characteristics may reveal other parameters than carrier mobility, in particular threshold voltage, which may also be employed for the transduction of airborne gases. Examples for real- time and/or multiparametric OFET characterisation systems for gas sensing are e.g. in [

5,

6]. The poly(triaryl amine) (PTAA) organic semiconductor family has proved particularly sensitive to NO

2, leading to solution- processed OFET- based NO

2 sensors as reported by Das et al. [

7]. Cui et al. [

8] later reported a solution- processed copper phthalocyanine (CuPc) OFET sensor for NO

2, but the poor solubility of CuPc demands for a toxic perfluorinated organic acid as solvent, resulting transistors show very small saturated drain currents even at high gate voltages (~100 nA at 60 V), and the reported limit- of- detection of 300 ppb is not particularly low. Anisimov et al. [

9] have designed and tested a vacuum- evaporated OFET array for the analysis of ambient air with respect to identity and quantity of air pollutants NO

2, NH

3, H

2S and SO

2, based on OFETs using different metalloporphyrins (Cu/Zn/TiO- porphyrin) as organic semiconductors. .A review of OFET gas sensors is e.g. by Trul et al. [

10].

As impressive as some of these works are, the preparation and electric characterisation of OFET sensor devices require formidable skills and instrumentation. A far simpler approach to gas detection is based on ‘chemiresistors’, i.e. devices that are (only) characterised for electric resistance while exposed to potentially contaminated air. Such chemiresistor sensors have been realised by common insulating polymer matrices filled with conductive ‘carbon black’ (CB) particles. The response to airborne pollutants is not by a direct impact on the conductivity of CB, but by the somewhat selective swelling of different polymer matrices when exposed to airborne pollutants, and the consequential increase in the separation of CB particles leading to reduced conductivity. The only moderate selectivity of swelling calls for the use of sensor arrays with a wide range of polymer matrices, and the subsequent analysis of the array’s response pattern with sophisticated methods. The historic ‘breakthrough’ contribution to this field was the work of Lewis et al. [

11]. Such arrays are very useful for the identification and quantification of vapours rather than gases, i.e. molecules escaping into the headspace above a liquid that is thermodynamically stable at ambient pressure and temperature. Typical target analytes are saturated, unsaturated, and aromatic hydrocarbon vapours, chlorinated alkanes, alcohols, and ketones. A recent review is in [

12].

However, air pollutant gases like NO

2, NH

3, H

2S and SO

2 are harmful at concentrations too low to elicit a strong swelling response and are better sensed by materials that respond directly by their electronic transport properties, like the organic semiconductors in OFET gas sensors introduced above. These have so far not often been applied in the simpler chemiresistor setting due to the high resistances associated with ungated organic semiconductors, and the consequential difficulties with their measurement. However, thanks to the progress of bespoke integrated circuit (IC) voltage followers, the measurement of very high resistances has recently become practically viable: Special engineering methods raise the input resistance of the commercially available voltage buffer Analog Devices AD8244 to an ultra-high value 10 TΩ [

13]. This brings the measurement of resistances up to at least 100 GΩ into range with a small experimental footprint.

We therefore here study chemiresistor gas sensors based on copper(II)phthalocyanine, CuPc, a close chemical relative to the metalloporphyrins used by Anisimov et al. [

9]. Beyond its widespread use as blue pigment, CuPc has been used as hole- transporting organic semiconductor, e.g. in organic solar cells [

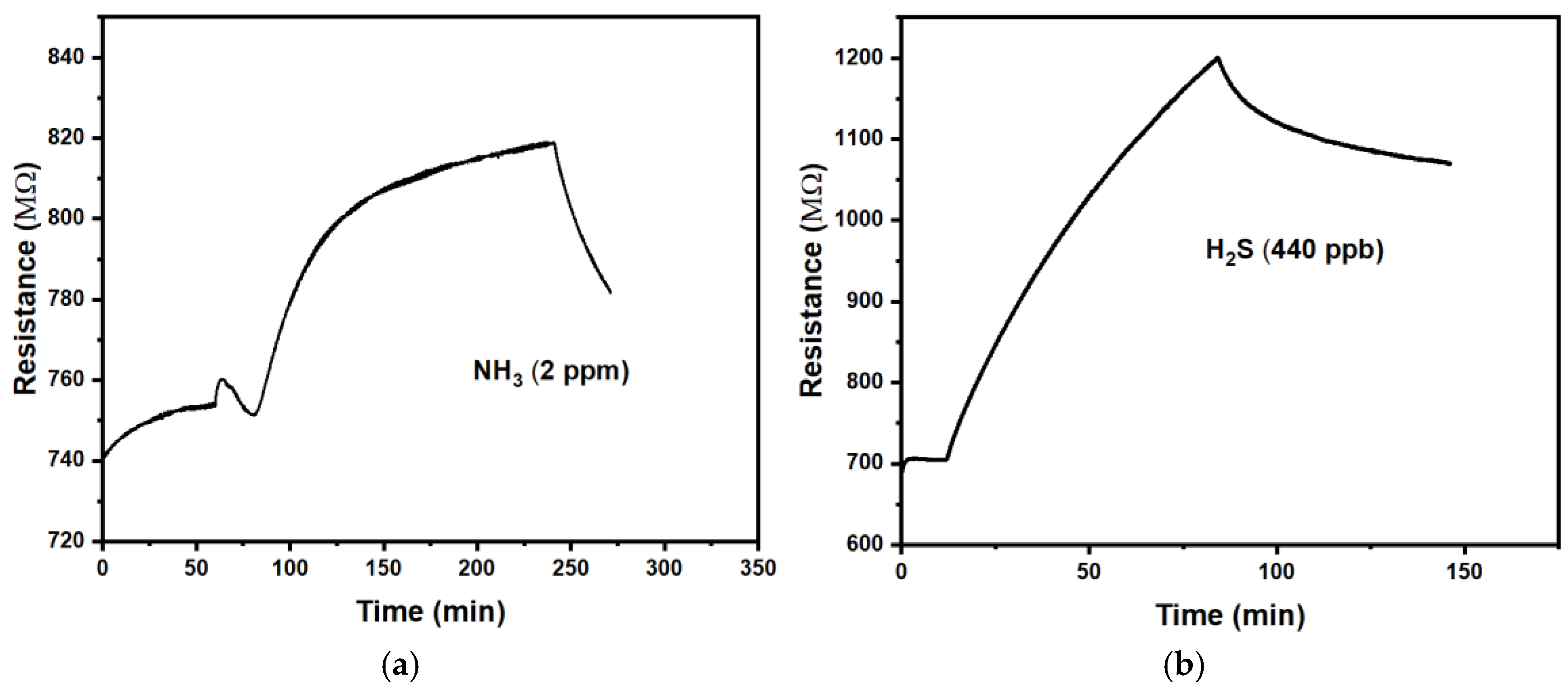

14]. We find that CuPc chemiresistors respond to a variety of harmful gases, including NH

3, H

2S and SO

2 at low to moderate concentrations. In some cases response is ‘positive’, i.e. chemiresistor resistance R increases under exposure. We find a ‘negative’ response, i.e. reduced resistance R, only under NO

2 and SO

2, making our sensor selective for different types of gases. While these findings qualitatively agree with a prior report by Chia et al. [

15], we find significant differences in the quantitative response to NO

2. Our chemiresistor shows almost no response to NO

2 in the concentration range of permitted environmental LVs (< 100 ppb), but responds very strongly above a threshold concentration of 87 ppb. This characteristic destins our sensor for workplace applications where there is a risk of NO

2 leakage.

4. Conclusions

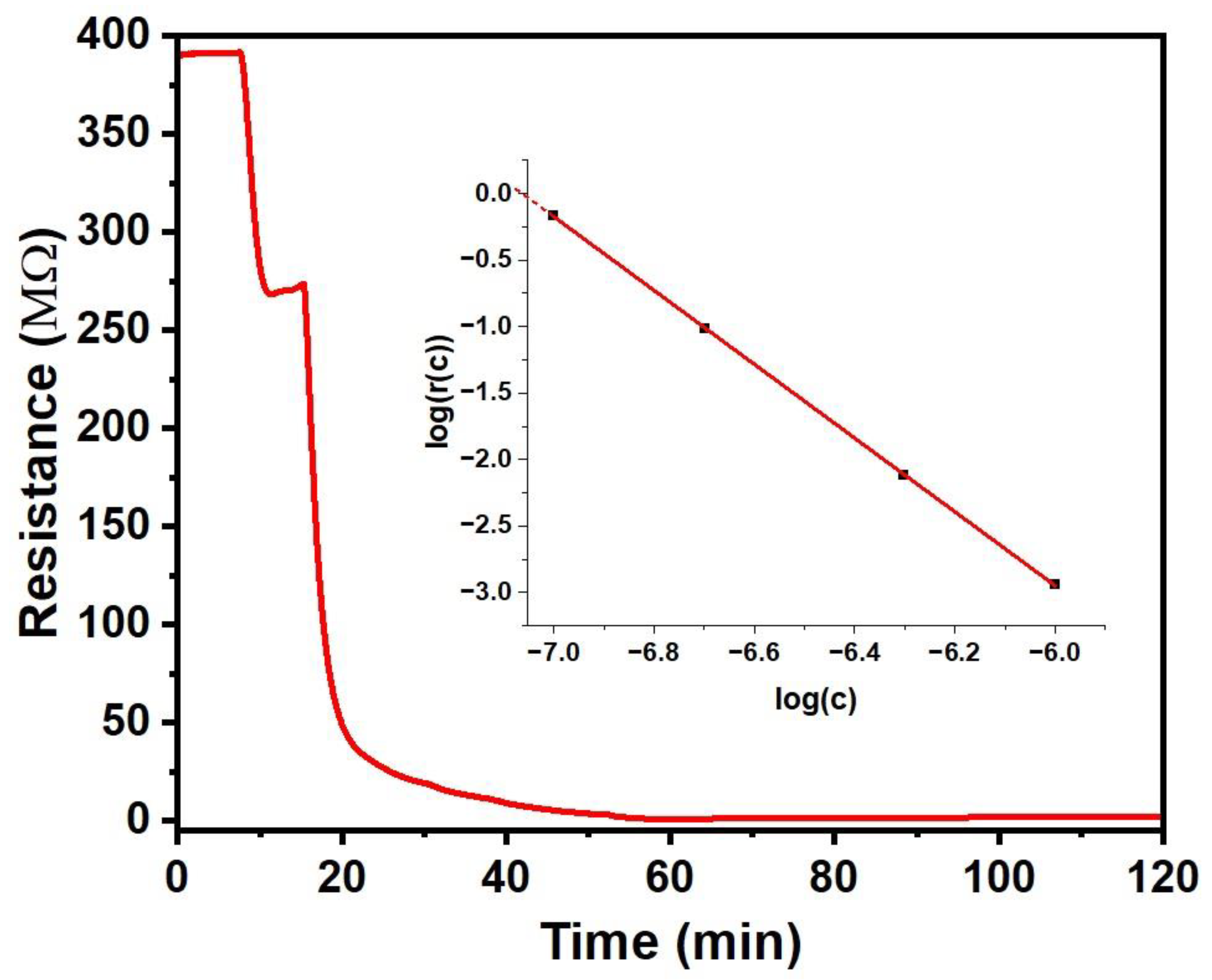

We here present a selective chemiresistor sensor for NO

2 based on a thin film of the organometallic semiconductor copper(II)phthalocyanine (CuPc). The sensor is easily manufactured, and can be read by a simple resistance (R) measurement. R is high but within the measurement range of modern voltage buffer ICs like the AD8244 [

13]. The CuPc film shows small to moderate response under exposure to several harmful gases. CuPc responds with an increase of resistance (‘positive’ response) to NH

3 and H

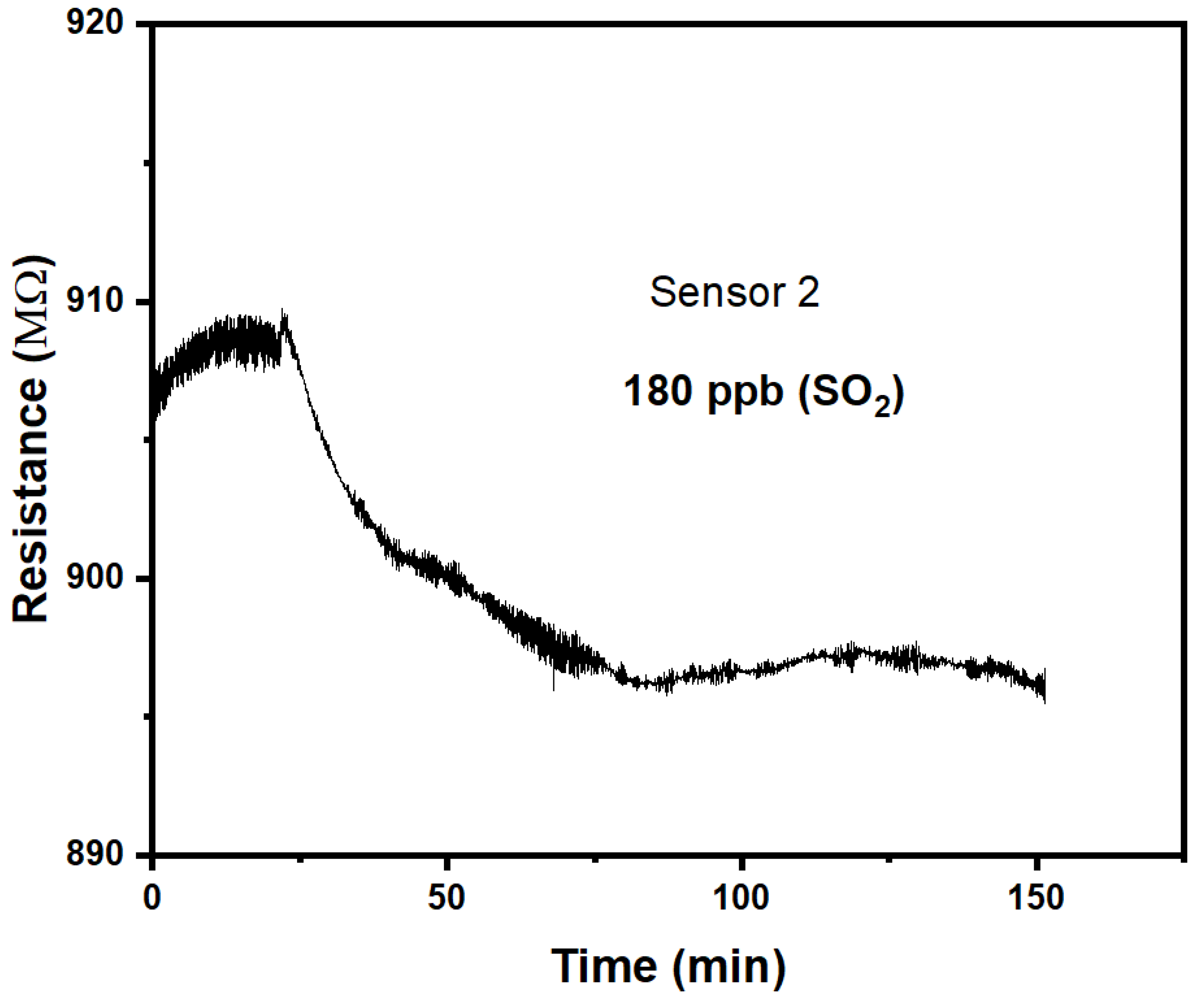

2S, and with a negative response to SO

2 and NO

2. This gives our sensor some selectivity as the sign of response allows us to discriminate between gases. The response to SO

2 is very low up to 180 ppb, r(180ppb) = 0.983, magnitude m = 0.0074, when 180 ppb is already significantly larger than permitted environmental SO

2 pollution levels. Common environmental pollutants will therefore not interfere with NO

2 detection. Sensitivity to NO

2 also is low or zero in the range of permitted long-term or permanent exposure limits, with a limit-of-detection (LoD) of ~ 87 ppb vs. EU permanent exposure limit of 21 ppb [

1]. Our sensor is therefore not well suited for environmental monitoring. However, 87 ppb NO

2 acts as a threshold above which sensitivity becomes very high, presumably due to the doping of CuPc by the strongly oxidising NO

2. Our sensor is therefore destined for industrial settings, particularly in the nitrogen fertiliser industry where NO

2 leakage to concentrations far above typical environmental pollution levels poses a clear and present danger. The response characteristic of our sensor is well adapted to warn of such leaks: There is near-zero response to typical and sometimes acceptable environmental ‘background’ NO

2 levels < 87 ppb. But in case of an NO

2 leak, there will be a ‘shrill’ warning: E.g. at 1 ppm NO

2, film resistance R is reduced ~ 870 times (response magnitude m = 2.94) vs. the un- exposed sensor within 50 min. While 1 ppm NO

2 is far above ‘background’ environmental pollution, it is still well below immediately life-threatening levels, e.g. the short-term NO

2 ‘emergency exposure limit’ (EEL) is 10 ppm for 1 hour [

3]. Therefore, our sensor gives a clear warning when there still is time for staff to evacuate. As such an alarm hopefully will be a rare event, recovery of sensors after such exposure is not required: Once exposed to ‘alarm’ levels, sensors shall be exchanged for pristine replacements.

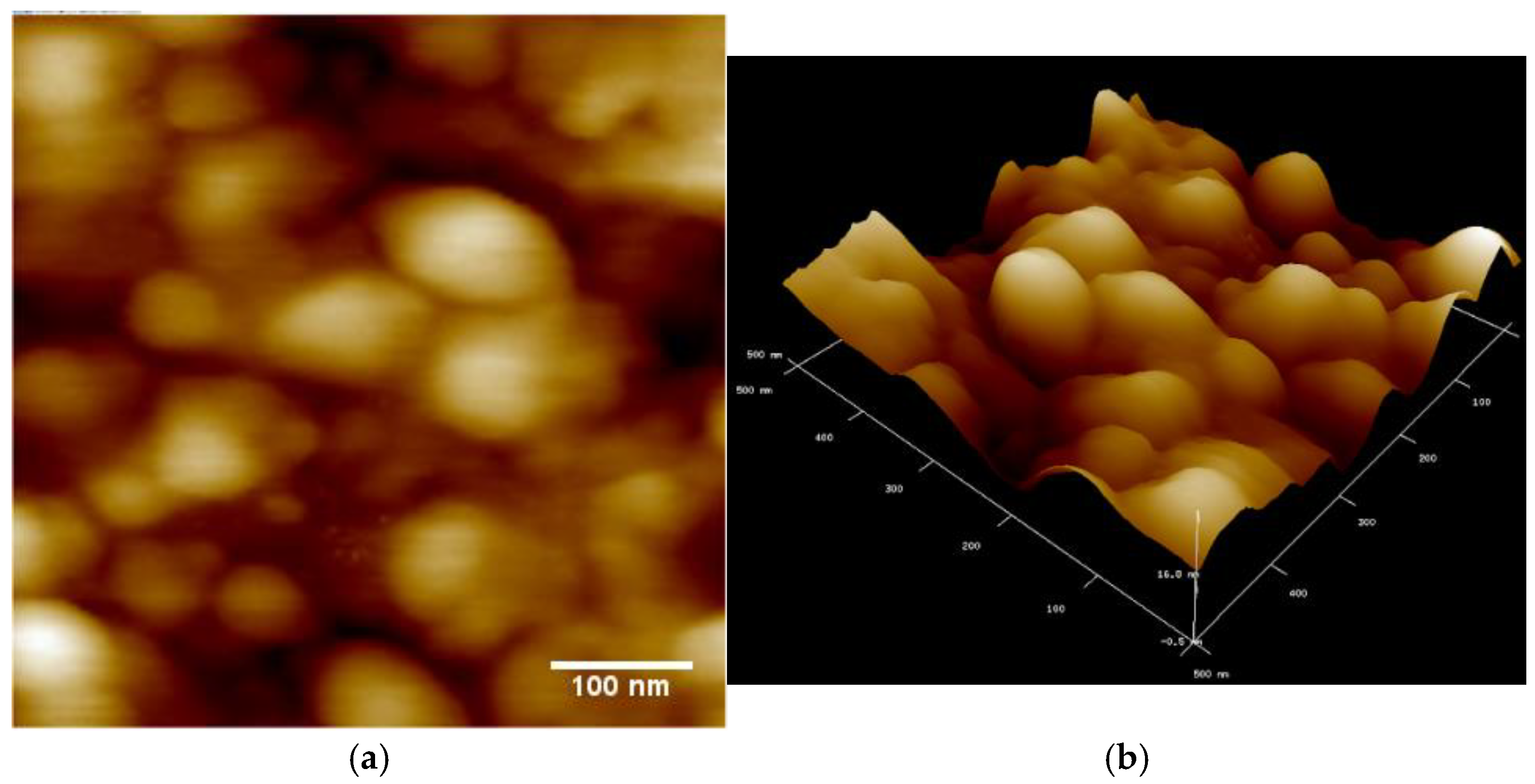

The response to NO

2 reported for our chemiresistors here are significantly larger than in the previous report by Chia et al. [

15], albeit they used the same organometallic semiconductor, CuPc. We note a few significant differences in the preparation of semiconducting films, with consequential differences in morphology between our films and those reported by Chia et al., cf. part 3a. While we can not give a detailed ‘cause- and- effect’ explanation for the much enhanced response observed by us, we conclude that our morphology enhances chemiresistor response. It is well established that charge transport (and other properties) in a given organic semiconductor strongly depend on its morphology, detailed reviews are e.g. in Stingelin et al. [

18] and Bi et al. [

19].