Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Disclosure

Funding

References

- Feldman, T.; Foster, E.; Glower, D.D.; Kar, S.; Rinaldi, M.J.; Fail, P.S.; Smalling, R.W.; Siegel, R.; Rose, G.A.; Engeron, E.; Loghin, C.; Trento, A.; Skipper, E.R.; Fudge, T.; Letsou, G.V.; Massaro, J.M.; Mauri, L. EVEREST II Investigators. Percutaneous repair or surgery for mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 1395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Lindenfeld, J.; Abraham, W.T.; Kar, S.; Lim, D.S.; Mishell, J.M.; Whisenant, B.; Grayburn, P.A.; Rinaldi, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Rajagopal, V.; Sarembock, I.J.; Brieke, A.; Marx, S.O.; Cohen, D.J.; Weissman, N.J.; Mack, M.J. COAPT Investigators. Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 2307–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Egorova, N.; Moskowitz, G.; Giustino, G.; Ailawadi, G.; Acker, M.A.; Gillinov, M.; Moskowitz, A.; Gelijns, A. Trends in MitraClip, mitral valve repair, and mitral valve replacement from 2000 to 2016. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021, 162, 551–562.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Ye, G.; Ding, C. Mortality and Clinical Predictors After Percutaneous Mitral Valve Repair for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 918712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedogni, F.; Testa, L.; Rubbio, A.P.; Bianchi, G.; Grasso, C.; Scandura, S.; De Marco, F.; Tusa, M.; Denti, P.; Alfieri, O.; et al. Real-World Safety and Efficacy of Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair With MitraClip: Thirty-Day Results From the Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology (GIse) Registry Of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve RegurgitaTiOn (GIOTTO). Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2020, 21, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, T.; Ricci, F.; Dangas, G.D.; Rana, B.S.; Ceriello, L.; Testa, L.; Khanji, M.Y.; Caterino, A.L.; Fiore, C.; Rubbio, A.P.; et al. Selection of the Optimal Candidate to MitraClip for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: Beyond Mitral Valve Morphology. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Finizio, F.; Ferraro, P.; Denti, P.; Rubbio, A.P.; Petronio, A.S.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Mongiardo, A.; De Felice, F.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of MitraClip in octogenarians: Evidence from 1853 patients in the GIOTTO registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 342, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Ferraro, P.; Finizio, F.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Denti, P.; Bedogni, F.; Rubbio, A.P.; Petronio, A.S.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Mongiardo, A.; Giordano, S.; DEFelice, F.; Adamo, M.; Montorfano, M.; Baldi, C.; Tarantini, G.; Giannini, F.; Ronco, F.; Monteforte, I.; Villa, E.; Ferrario, M.; Fiocca, L.; Castriota, F.; Tamburino, C. Implantation of one, two or multiple MitraClip™ for transcatheter mitral valve repair: insights from a 1824-patient multicenter study. Panminerva Med 2022, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Ferraro, P.; Finizio, F.; Cimmino, M.; Albanese, M.; Morello, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Denti, P.; Rubbio, A.P.; Bedogni, F.; et al. Incidence and Predictors of Cerebrovascular Accidents in Patients Who Underwent Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair With MitraClip. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 228, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Ferraro, P.; Finizio, F.; Corcione, N.; Cimmino, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Denti, P.; Rubbio, A.P.; Petronio, A.S.; Bartorelli, A.L.; et al. Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair With the MitraClip Device for Prior Mitral Valve Repair Failure: Insights From the GIOTTO-FAILS Study. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2024, 13, e033605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Pepe, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Corcione, N.; Finizio, F.; Ferraro, P.; Denti, P.; Popolo Rubbio, A.; Petronio, S.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Nestola, P.L.; Mongiardo, A.; DEFelice, F.; Adamo, M.; Montorfano, M.; Baldi, C.; Tarantini, G.; Giannini, F.; Ronco, F.; Monteforte, I.; Villa, E.; Ferrario Ormezzano, M.; Fiocca, L.; Castriota, F.; Bedogni, F.; Tamburino, C. Impact of coronary artery disease on outcome after transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system. Panminerva Med 2023, 65, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhatriwalla, A.K.; Vemulapalli, S.; Holmes DRJr Dai, D.; Li, Z.; Ailawadi, G.; Glower, D.; Kar, S.; Mack, M.J.; Rymer, J.; Kosinski, A.S.; Sorajja, P. Institutional Experience With Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair and Clinical Outcomes: Insights From the TVT Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 12, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatriwalla, A.K.; Vemulapalli, S.; Szerlip, M.; Kodali, S.; Hahn, R.T.; Saxon, J.T.; Mack, M.J.; Ailawadi, G.; Rymer, J.; Manandhar, P.; et al. Operator Experience and Outcomes of Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair in the United States. Circ. 2019, 74, 2955–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonow, R.O.; O'Gara, P.T.; Adams, D.H.; Badhwar, V.; Bavaria, J.E.; Elmariah, S.; Hung, J.W.; Lindenfeld, J.; Morris, A.; Satpathy, R.; et al. Multisociety expert consensus systems of care document 2019 AATS/ACC/SCAI/STS expert consensus systems of care document: Operator and institutional recommendations and requirements for transcatheter mitral valve intervention: A Joint Report of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the American College of Cardiology, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 95, 866–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, C.; Musumeci, G.; Saia, F.; Tarantini, F. Percutaneous approaches to mitral valve disease. Torino, 2019: Minerva Medica.

- Kolte, D.; Butala, N.M.; Kennedy, K.F.; Wasfy, J.H.; Jena, A.B.; Sakhuja, R.; Langer, N.; Melnitchouk, S.; Sundt, T.M., 3rd; Passeri, J.J.; Palacios, I.F.; Inglessis, I.; Elmariah, S. Association Between Hospital Cardiovascular Procedural Volumes and Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair Outcomes. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2022, 36, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, K.; Hobohm, L.; Schmidtmann, I.; Münzel, T.; Baldus, S.; von Bardeleben, R.S. Centre procedural volume and adverse in-hospital outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous transvenous edge-to-edge mitral valve repair using MitraClip® in Germany. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2021, 23, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, S.; Kuno, T.; Malik, A.; Briasoulis, A.; Inohara, T.; Kampaktsis, P.N.; Kohsaka, S.; Latib, A. Association between institutional volume of transcatheter mitral valve repair and readmission rates: A report from the Nationwide Readmission Database. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 383, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcione, N.; Ferraro, P.; Finizio, F.; Cimmino, M.; Albanese, M.; Morello, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Denti, P.; Rubbio, A.P.; Bedogni, F.; et al. Overall impact of tethering and of its symmetric and asymmetric subtypes on early and long-term outcome of transcatheter edge-to-edge repair of significant mitral valve regurgitation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 421, 132874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcione, N.; Ferraro, P.; Morello, A.; Cimmino, M.; Albanese, M.; Avellino, R.; Turino, S.; Polimeno, M.; Messina, S.; Maresca, G.; et al. A 25-year-long journey into interventional cardiology: looking back, and rushing forward. Minerva Medica 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Pawar, S.; Gupta, T.; Gilani, F.; Khera, S.; Kolte, D. Association Between Hospital Volume and 30-Day Readmissions After Transcatheter Mitral Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 203, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, G.; Rossini, G.; Schiavi, D.; Guicciardi, N.A.; Saccocci, M.; Buzzatti, N.; Godino, C.; Alfieri, O.; Agricola, E.; Maisano, F.; et al. Remote proctoring during structural heart procedures: Toward a widespread diffusion of knowledge using mixed reality. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nita, N.; Schneider, L.; Dahme, T.; Markovic, S.; Keßler, M.; Rottbauer, W.; Tadic, M. Trends in Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Mitral Valve Repair Over a Decade: Data From the MiTra ULM Registry. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 850356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W. Volume-Outcome Relationships for Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair: More Is Better. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019, 12, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 645 | 947 | 621 | - |

| Age (years) | 78 (72; 83) | 77 (70; 82) | 79 (70; 83) | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 211 (32.7%) | 586 (61.9%) | 380 (61.2%) | 0.039 |

| Body mass index | 24.9 (22.7; 27.6) | 24.8 (22.1; 27.8) | 23.4 (2.0; 25.6) | 0.356 |

| Smoking history | 72 (11.1%) | 88 (9.3%) | 163 (26.3%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 462 (71.6%) | 696 (73.5%) | 445 (71.7%) | 0.628 |

| Dyslipidemia | 212 (32.9%) | 256 (27.0%) | 267 (43.0%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 157 (24.3%) | 220 (23.2%) | 144 (23.2%) | 0.851 |

| Diagnosis | 0.002 | |||

| Degenerative MR | 176 (27.3%) | 330 (34.9%) | 198 (31.9%) | |

| Functional dilated MR | 199 (30.9%) | 277 (29.3%) | 180 (29.0%) | |

| Functional ischemic MR | 194 (30.1%) | 230 (24.3%) | 194 (31.2%) | |

| Mixed etiology | 76 (11.8%) | 110 (11.6%) | 49 (7.9%) | |

| New York Association class | <0.001 | |||

| I | 4 (0.6%) | 11 (1.2%) | 17 (2.8%) | |

| II | 110 (17.1%) | 215 (22.7%) | 196 (31.9%) | |

| III | 452 (70.1%) | 660 (69.7%) | 350 (57.0%) | |

| IV | 79 (12.3%) | 61 (6.4%) | 51 (8.3%) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.711 | |||

| None | 201 (63.8%) | 134 (60.1%) | 275 (64.0%) | |

| Single vessel disease | 49 (15.6%) | 42 (18.8%) | 67 (15.6%) | |

| Two vessel disease | 25 (7.9%) | 23 (10.3%) | 48 (11.2%) | |

| Three vessel disease | 22 (7.0%) | 13 (5.8%) | 22 (5.1%) | |

| Left main disease | 18 (5.7%) | 11 (4.9%) | 18 (4.2%) | |

| Prior pacemaker implantation | ||||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 213 (33.0%) | 312 (33.0%) | 194 (31.2%) | 0.735 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass grafting | 83 (12.9%) | 126 (13.3%) | 104 (16.8%) | 0.087 |

| Prior mitral valve intervention | 17 (2.6%) | 14 (1.5%) | 38 (6.1%) | <0.001 |

| Prior cerebrovascular event | <0.001 | |||

| None | 601 (93.2%) | 891 (94.1%) | 548 (88.2%) | |

| Transient ischemic attack | 12 (1.9%) | 14 (1.5%) | 31 (5.0%) | |

| Minor stroke | 17 (2.6%) | 22 (2.3%) | 12 (1.9%) | |

| Major stroke | 15 (2.3%) | 20 (2.1%) | 30 (4.8%) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 54 (8.4%) | 38 (4.0%) | 74 (11.9%) | <0.001 |

| Frailty | 116 (18.0%) | 118 (12.5%) | 418 (67.3%) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 15 (2.3%) | 18 (1.9%) | 9 (1.5%) | 0.521 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 10.5 (6.5; 16.4) | 10.4 (6.2; 19.5) | 3.9 (3.4; 4.5) | 0.007 |

| CHADS2 score | 2 (2; 3) | 2 (2; 3) | 2 (1; 3) | 0.004 |

| CHADS2Vasc score | 4 (3; 5) | 4 (3; 5) | 4 (3; 4) | 0.443 |

| Feature | First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 645 | 947 | 621 | - |

| LA AP diameter (mm) | 45 (40; 50) | 49 (44; 55) | 49 (45; 55) | 0.089 |

| LV EDD (mm) | 61 (54; 68) | 58 (52; 64) | 58 (50; 65) | <0.001 |

| LV ESD (mm) | 49 (38; 56) | 41 (33; 51) | 45 (35; 54) | <0.001 |

| LV EDV (mL) | 164 (120; 212) | 137 (105; 181) | 140 (100; 189) | <0.001 |

| LV ESV (mL) | 97 (55; 146) | 73 (48; 116) | 81 (47; 130) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 38 (30; 55) | 42 (31; 55) | 40 (30; 57) | 0.008 |

| Tenting area (cm2) | 3.0 (2.2; 3.7) | 2.3 (1.6; 3.0) | 1.9 (1.3; 2.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean mitral valve gradient (mm Hg) | 2 (1; 3) | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (2; 3) | 0.148 |

| Severe mitral regurgitation | 495 (76.7%) | 739 (78.0%) | 493 (79.4%) | 0.525 |

| Severe mitral calcification | 22 (3.4%) | 28 (3.0%) | 55 (8.9%) | <0.001 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 163 (25.3%) | 262 (27.7%) | 205 (33.0%) | 0.007 |

| Flail leaflet | 132 (20.5%) | 176 (18.6%) | 146 (23.5%) | 0.063 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | <0.001 | |||

| None or trace | 23 (3.6%) | 62 (6.6%) | 22 (3.5%) | |

| Mild | 282 (43.7%) | 324 (34.2%) | 234 (37.7%) | |

| Moderate | 273 (42.3%) | 458 (48.4%) | 239 (38.5%) | |

| Severe | 67 (10.4%) | 103 (10.9%) | 126 (20.3%) | |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 46 (40; 55) | 45 (37; 55) | 45 (35; 55) | 0.071 |

| Any ECG abnormality | 152 (23.6%) | 163 (17.2%) | 296 (47.7%) | <0.001 |

| Second-degree atrioventricular block | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 3 (0.5%) | 0.039 |

| Third-degree atrioventricular block | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 0.806 |

| Right bundle branch block | 17 (2.6%) | 20 (2.1%) | 18 (2.9%) | 0.577 |

| Left bundle branch block | 27 (4.2%) | 27 (2.9%) | 28 (4.5%) | 0.165 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 111 (17.2%) | 118 (12.5%) | 248 (39.9%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiography performed | 315 (48.8%) | 223 (23.6%) | 430 (69.2%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.711 | |||

| No | 201 (63.8%) | 134 (60.1%) | 275 (64.0%) | |

| 1-vessel disease | 49 (15.6%) | 42 (18.8%) | 67 (15.6%) | |

| 2-vessel disease | 25 (7.9%) | 23 (10.3%) | 48 (11.2%) | |

| 3-vessel disease | 22 (7.0%) | 13 (5.8%) | 22 (5.1%) | |

| Left main disease | 18 (5.7%) | 11 (4.9%) | 18 (4.2%) |

| Outcome | First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 645 | 947 | 621 | |

| Implantation of ≥2 MitraClip devices | 421 (65.3%) | 508 (53.6%) | 377 (60.7%) | <0.001 |

| Implantation on NT device | 433 (67.1%) | 499 (52.7%) | 308 (49.6%) | <0.001 |

| Implantation on NTr device | 98 (15.2%) | 178 (18.8%) | 92 (14.8%) | 0.062 |

| Implantation of XTr device | 160 (24.8%) | 358 (37.8%) | 249 (40.1%) | <0.001 |

| Device time (minutes) | 2.3 (1.5; 3.5) | 2.1 (1.5; 2.7) | 3.5 (2.1; 4.4) | <0.001 |

| Fluoroscopy time (minutes) | 0.8 (0.6; 1.7) | 1.3 (0.8; 1.9) | 0.4 (0.2; 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Device success | 641 (99.4%) | 942 (99.5%) | 620 (99.8%) | 0.513 |

| Procedural success | 600 (93.0%) | 926 (97.8%) | 593 (95.5%) | <0.001 |

| Procedural death | 3 (0.5%) | 0 | 2 (03%) | 0.104 |

| Mitral valve gradient at end of procedure | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (3; 5) | <0.001 |

| Mitral regurgitation at end of procedure | <0.001 | |||

| None | 386 (59.8%) | 561 (59.2%) | 453 (73.0%) | |

| Mild | 209 (32.4%) | 348 (36.8%) | 147 (23.7%) | |

| Moderate | 34 (5.3%) | 26 (2.8%) | 12 (1.9%) | |

| Severe | 16 (2.5%) | 12 (1.3%) | 9 (1.5%) | |

| Inhospital death | 18 (2.8%) | 20 (2.1%) | 24 (3.9%) | 0.123 |

| Inhospital stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Inhospital bleeding | 0.006 | |||

| None | 644 (99.8%) | 939 (99.2%) | 610 (98.2%) | |

| Minor | 0 | 5 (0.5%) | 7 (1.1%) | |

| Major | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.6%) | |

| Disabling | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0 | |

| Inhospital vascular complication | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | 10 (1.6%) | 0.008 |

| Days of hospitalization | 8 (5; 12) | 5 (4; 8) | 5 (4; 8) | <0.001 |

| Mitral regurgitation at discharge | 0.001 | |||

| None | 347 (55.3%) | 503 (54.3%) | 388 (65.0%) | |

| Mild | 226 (36.0%) | 354 (38.2%) | 171 (28.6%) | |

| Moderate | 39 (6.2%) | 59 (6.4%) | 27 (4.5%) | |

| Severe | 15 (2.4%) | 11 (1.2%) | 11 (1.0%) | |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 40 (32; 46) | 40 (35; 50) | 40 (30; 45) | <0.001 |

| Outcome | First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 645 | 947 | 621 | |

| Follow-up (months) | 12 (1; 24) | 21 (10; 36) | 13 (1; 25) | <0.001 |

| Death | 152 (23.6%) | 251 (26.5%) | 136 (21.9%) | 0.101 |

| Cardiac death | 86 (13.3%) | 125 (13.2%) | 75 (12.1%) | 0.764 |

| Hospitalization | 107 (16.6%) | 114 (12.0%) | 68 (11.0%) | 0.007 |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 82 (12.7%) | 86 (9.1%) | 65 (10.5%) | 0.070 |

| Death or hospitalization | 199 (30.1%) | 307 (32.4%) | 179 (28.8%) | 0.323 |

| Cardiac death or hospitalization for heart failure | 142 (22.0%) | 189 (20.0%) | 127 (20.5%) | 0.596 |

| Mitral valve surgery | 4 (0.6%) | 8 (0.8%) | 13 (2.1%) | 0.034 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 12 (1.9%) | 13 (1.4%) | 9 (1.5%) | 0.722 |

| New York Heart Association | 0.006 | |||

| I | 59 (14.0%) | 159 (21.3%) | 55 (13.3%) | |

| I | 270 (64.0%) | 425 (56.9%) | 254 (61.2%) | |

| III | 85 (20.1%) | 153 (20.5%) | 98 (23.6%) | |

| IV | 8 (1.9%) | 10 (1.3%) | 8 (1.9%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 124 (19.2%) | 135 (14.3%) | 258 (41.6%) | <0.001 |

| End-diastolic diameter (mm) | 60 (53; 67) | 57 (50; 64) | 56 (49; 62) | <0.001 |

| End-systolic diameter (mm) | 48 (38; 56) | 40 (31; 50) | 40 (35; 53) | <0.001 |

| End-diastolic volume (mL) | 159 (120; 220) | 131 (100; 180) | 133 (98; 187) | <0.001 |

| End-systolic volume (mL) | 90 (56; 138) | 73 (45; 115) | 85 (45; 130) | 0.004 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 38 (28; 51) | 42 (30; 55) | 38 (27; 52) | <0.001 |

| Mitral valve gradient (mm Hg) | 3 (3; 5) | 4 (3; 5) | 4 (3; 5) | 0.023 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 0.113 | |||

| None | 281 (44.7%) | 433 (46.7%) | 297 (49.8%) | |

| Mild | 250 (39.8%) | 365 (39.4%) | 219 (36.7%) | |

| Moderate | 66 (10.5%) | 103 (11.1%) | 53 (8.9%) | |

| Severe | 32 (5.1%) | 26 (2.8%) | 28 (4.7%) | |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 219 (52.4%) | 246 (33.1%) | 85 (22.3%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 34 (8.1%) | 77 (10.4%) | 41 (10.8%) | 0.367 |

| Betablockers | 348 (82.7%) | 362 (75.4%) | 299 (78.3%) | 0.015 |

| Ivabradine | 23 (5.5%) | 30 (4.0%) | 18 (4.7%) | 0.495 |

| Furosemide | 393 (92.7%) | 677 (90.6%) | 361 (90.5%) | 0.421 |

| Aspirin | 185 (44.2%) | 318 (42.5%) | 183 (48.3%) | 0.183 |

| Thienopyridines | 64 (15.4%) | 161 (21.6%) | 89 (23.5%) | <0.001 |

| Novel oral anticoagulants | 154 (24.8%) | 262 (28.6%) | 113 (18.7%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 167 (26.9%) | 221 (24.2%) | 148 (24.6%) | 0.455 |

| Intravenous inotropes | 11 (2.6%) | 3 (0.4%) | 6 (1.6%) | 0.003 |

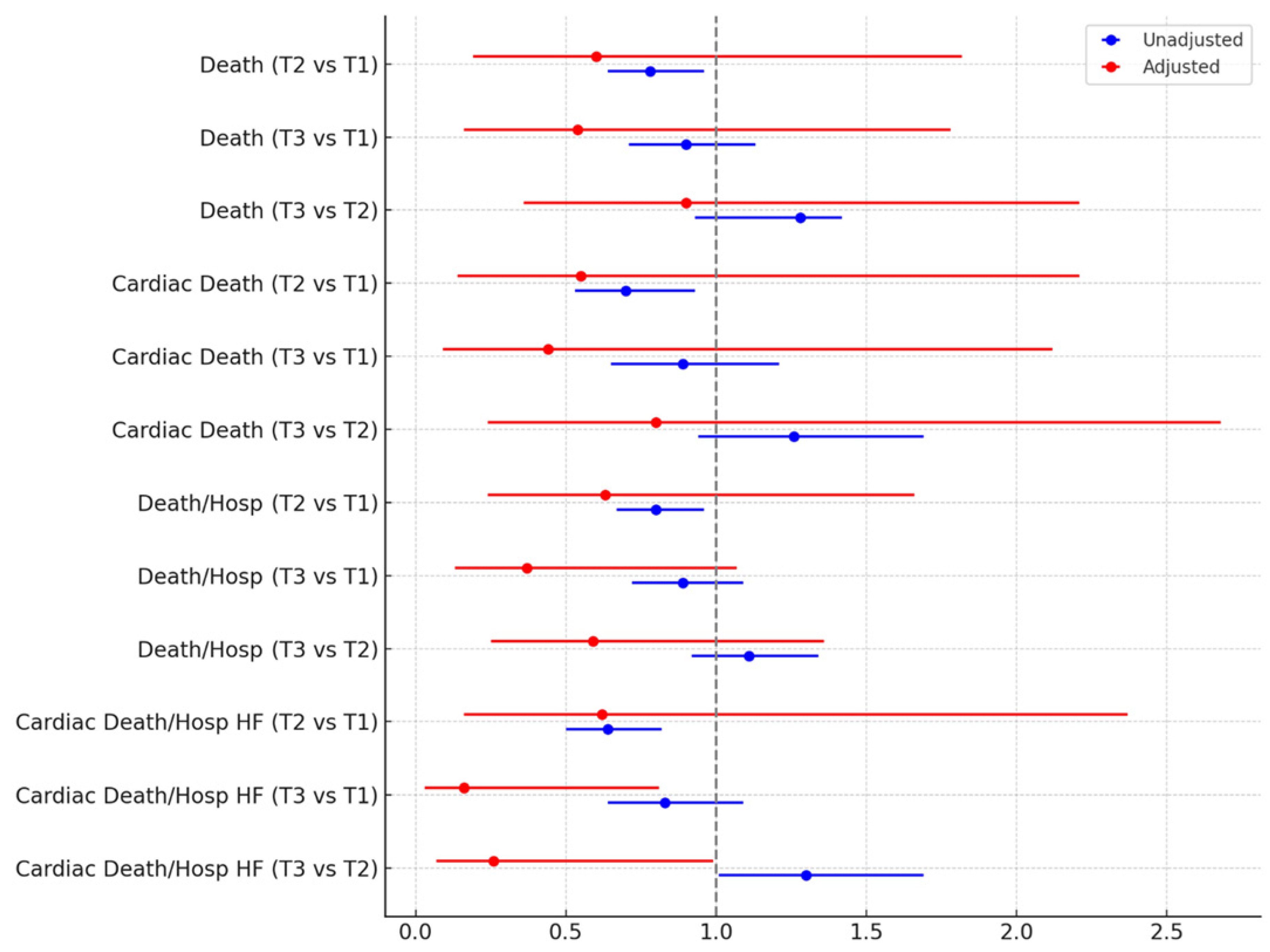

| Outcome | Unadjusted effect estimates | Adjusted effect estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Death | ||

| Tertile 2 vs 1 | 0.78 (0.64-0.96), p=0.018 | 0.60 (0.19-1.82), p=0.364 |

| Tertile 3 vs 1 | 0.90 (0.71-1.13), p=0.365 | 0.54 (0.16-1.78), p=0.308 |

| Tertile 3 vs 2 | 1.28 (0.93-1.42), p=0.191 | 0.90 (0.36-2.21), p=0.814 |

| Cardiac death | ||

| Tertile 2 vs 1 | 0.70 (0.53-0.93), p=0.015 | 0.55 (0.14-2.21), p=0.398 |

| Tertile 3 vs 1 | 0.89 (0.65-1.21), p=0.456 | 0.44 (0.09-2.12), p=0.304 |

| Tertile 3 vs 2 | 1.26 (0.94-1.69), p=0.117 | 0.80 (0.24-2.68), p=0.713 |

| Death or hospitalization | ||

| Tertile 2 vs 1 | 0.80 (0.67-0.96), p=0.014 | 0.63 (0.24-1.66), p=0.351 |

| Tertile 3 vs 1 | 0.89 (0.72-1.09), p=0.246 | 0.37 (0.13-1.07), p=0.065 |

| Tertile 3 vs 2 | 1.11 (0.92-1.34), p=0.265 | 0.59 (0.25-1.36), p=0.213 |

| Cardiac death or hospitalization for heart failure | ||

| Tertile 2 vs 1 | 0.64 (0.50-0.82), p<0.001 | 0.62 (0.16-2.37), p=0.488 |

| Tertile 3 vs 1 | 0.83 (0.64-1.09), p<0.001 | 0.16 (0.03-0.81), p=0.026 |

| Tertile 3 vs 2 | 1.30 (1.01-1.69), p=0.045 | 0.26 (0.07-0.99), p=0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).