1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence has developed in recent years at a remarkable pace, a growth that has influenced and continues to influence many fields, education being no exception. In this article we highlight the practical potential of AI to revolutionize secondary and higher education, modifying and improving existing pedagogical approaches by creating motivating, effective and engaging learning environments.

In

Section 2 we study the current advances in teaching and evaluation methods, we assess the benefits of these enhanced methods and the reach in the real world as a proportion of the total student population. We found that less than 10% of the global education system is benefiting from these advanced techniques (see

Section 2.3).

We emphasize a major issue in education, the fact that most education institutions are lagging in adopting new technologies in their learning methods. While top universities are able to pioneer the newest education tools in their methods (for example most Ivy League universities take advantage of online courses and laboratories, AI assisted student assistants), this is not the case of the majority of 1.5 million secondary-level [

1] and 25k higher education institutions in the world. In this bulk percentage of educational institutions, which serve 90% of the world's students, the teaching and evaluation methods are still lagging.

At the same time, the majority of students nowadays prefer electronic support as course distribution support - in plain words, students would prefer to learn on a phone, tablet or computer (See

Section 2.) [

2,

3,

4]. But currently most course materials - main course, laboratory, seminar and exam questions - are mostly available as pdf, word documents, or printed books - formats that are not well-suited for direct use in computer or AI-assisted learning methods.

We assess the main causes/barriers to the introduction of these advanced methods, including low funding, lack of technical experience of the existing teaching corps and low student access to computing resources.

To address these major issues, we introduce in

Section 3 an open-source, one-click platform that enables teachers across all these universities to transform their traditional courses into an AI-enhanced learning experience, regardless of their technical expertise. Additionally, this platform is accessible to students from any browser on a computer, tablet or smartphone.

In

Section 4 we evaluate the proposed platform on two experiments: a) a pilot study on a population of teachers and students to assess application usability and correctness; b) human and automated tests on standard LLM benchmarks to assess the AI components performances

In

Section 5 we discuss the solution's benefits and the issues it solves, before presenting the closing thoughts in

Section 4.

2. Review of new methods used in Education

2.1. Computer aided methods in Education

Computer-Assisted Methods in Education (CAME) refer to instructional technologies and strategies that leverage computers to enhance teaching and learning. Emerging in the 2000s with the advent of the internet, these methods have since been extensively developed and widely adopted. They offer several benefits, including individualized learning, increased accessibility for students with disabilities, enhanced engagement, the opportunity for self-paced study, and the provision of immediate feedback [

5,

6].

CAME uses different teaching techniques and technological tools that seek to improve the instructional-educational process from which we discuss the most important: gamification, microlearning, virtual reality and more recently artificial intelligence (AI).

Virtual Reality (VR) combines with Augmented Reality (AR) in teaching to completely transform the educational experiences by providing dynamic and attractive contexts. AR enhances real-world experiences by superimposing digital data over the surrounding world, while VR lets students explore 3D worlds.

Another computer-based learning method is gamification, integrating specific game elements into the educational context. This approach has the effect of making learning activities more participatory and spectacular. The game-specific competition that gives students a sense of satisfaction is composed of simple elements such as leaderboards, points earned and badges [

7]. The market for gamification offerings in education has grown significantly, from

$93 million in 2015 to almost

$11.5 billion by 2020, demonstrating its growing acceptance in the industry [

6]. This upward trajectory has continued, with the market reaching approximately

$13.50 billion by 2024 and is projected to grow to

$42.39 billion by 2034 [

8].

Microlearning is about to become a major trend in the educational landscape, standing out by providing solutions to problems such as cognitive overload and teacher fatigue. This new method provides students with short and specific content when it suits them. According to some studies [

6,

9] microlearning segments of between two and five minutes are found to be very effective in terms of engagement and retention of new information Microlearning is also suitable for mobile, as it allows learners to interact "on the go" and access knowledge at the right moments [

6].

In recent years Artificial Intelligence has added to these modern methods of education especially in adaptive learning systems that provide content specific to the expectations of each student, thus improving the overall educational process [

9,

10]. This personalization improves the overall learning process and increases its effectiveness.

AI is already seen to play a significant role in education and is continually developing, resulting in intelligent learning guidance programs that adapt to the needs of each student and complex adaptive learning systems [

9,

10].

2.2. AI in Education

AI has significant potential to transform both teaching and learning in education. AI-solutions can automate administrative duties, tailor customized learning pathways, provide adaptive feedback, and overall create more engaging and efficient educational experiences.

In general education, AI was used to develop personalized learning platforms, intelligent tutoring systems, and even automated essay scoring although in incipient stages, such as Pearson's AI study tool [

11].

From kindergarten to university level, institutions are faced with the challenge of adapting to diverse student populations with varying learning styles and paces. Here AI can provide an answer by providing:

Personalized Learning/Adaptive Feedback: AI algorithms can personalize learning by assessing student performance, providing instant feedback, and adjusting the pace, content, and evaluation to cater to each learner's needs [

4,

5].

100% availability for answers from courses - similar to a teacher providing answers to students during main class, an AI solution can provide answers from the course materials to an unlimited number of students at 24/7.

Automated Grading: AI can automate tasks such as assignment grading and providing feedback to student inquiries, thus liberating faculty time for more in-depth student interactions.

Enhanced Research: In higher education, AI tools assist researchers [

6] in analyzing large datasets and phenomena, being an effective companion in extracting patterns and generating new ideas [

7,

9].

Improved Accessibility: AI-powered solutions can be enhanced with text-to-speech and speech-to-text features, providing support to students with disabilities.

There are five main directions in the domain of artificial intelligence (AI) application in education: assessment/evaluation, prediction, AI assistants, intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), and the management of student learning [

12] - each demonstrating potential for innovation in the education sector. We discuss below the ITS and AI assistants and AI evaluators.

An ITS is an AI system which provides personalized adaptive instruction, real-time feedback, and tailored learning experiences to support student progress [

13,

14]. An AI assistant is generally a simple chatbot which can answer student questions about the class in a similar way a teacher assistant would. The assessment/evaluation AI is basically able to grade the student test answers.

We can find in the existing literature different studies that presents the benefits and uses-cases for AI across various educational domains such as the social sciences [

15], engineering [

16], science [

17], medical [

18], life sciences [

19], language acquisition [

20], among others [

21,

22].

In recent years the applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in the educational sector were extensively explored, focusing on chatbots [

23], programming assistance [

24,

25], language models [

26,

27], and natural language processing (NLP) tools [

28]. More recently, the introduction of OpenAI's generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, ChatGPT [

28] and competitor models as Gemini [

29], Claude [

30] or LLAMA [

31] has attracted considerable interest [

32,

33]. These chatbots are based on large language models (LLM), trained on datasets of 100 billion words [

25] and have the capability to process, generate, and reason in natural languages [

26,

27,

28] at human-expert equivalent level. As a result of their high performance, AI chatbots gained widespread popularity [

34,

35] and they are now starting to benefit diverse fields, including research [

36,

37,

38] and education [

39].

In conclusion, both traditional algorithmic tools and AI technologies are used to improve the quality of the education process, including learning and evaluation.

2.3. Estimation of the usage of new methods in Education

Research on students' attitudes and behavior about paper vs digital learning has become a fascinating area of study. In this section we present an overview of the current split of the supports and tools used in education - and its evolution over time.

1. Paper-Based Materials (Textbooks and Print Handouts): Traditionally, nearly all instructional supports were paper-based. Meta-analyses in education [

40] indicate that in earlier decades printed textbooks and handouts could represent 70-80% of all learning materials. Over the past two decades, however, this share has steadily decreased (now roughly 40-50%) as digital tools have been integrated into teaching.

2. Computer-Based Supports (Websites, PDFs, and Learning Management Systems): Research [

41,

42] in the COVID-19 pandemic period demonstrate that Learning Management Systems (LMSs) and other computer-based resources (including websites and PDFs) have increased from practically 10% to about 40-50% of the educational supports in some settings. This evolution reflects both improved digital infrastructure and shifts in teaching practices.

3. Smartphones and Mobile Apps: Studies [

43] in the early 2010 reported very limited in-class smartphone use. Over time, however, as smartphones became ubiquitous, more recent research [

44] shows that these devices now grow to roughly 20-30% of learning interactions. This growth reflects both increased mobile connectivity and the rising popularity of educational apps.

4. Interactive Digital Platforms (Websites, Multimedia, and Collaborative Tools): Parallel to the growth in LMS and mobile use, digital platforms that incorporate interactive multimedia and collaborative features have also expanded. Meta-analyses [

45] indicate that while early 2000s classrooms saw digital tool usage on the order of 10-20%, today these platforms now comprise roughly 30-40% of the overall learning support environment. This trend underscores the increasing importance of online content and real-time collaboration in education.

These studies show an evolution from a paper-dominant model toward a blended environment where computer-based resources and mobile devices have grown significantly over the past two decades. Still, each mode of support plays a complementary role in modern education, and many studies also show that paper is still a preferred medium, especially from the reading experience point of view [

46].

For example, large-scale international surveys (10,293 respondents from 21 countries [

47] and 21,266 participants from 33 countries [

48]) have consistently indicated that most college students prefer to read academic publications in print. These same studies found a correlation between students’ age and their preferred reading modes, with younger students favoring printed materials. A qualitative analysis of student remarks reported in [

48] indicates that students' behavior is flexible. Students usually learn better when using printed materials, albeit this relies on several criteria, including length, convenience, and the importance of the assignments [

50].

2.4. The shift towards using AI tools

While the above papers showed a good percentage of students still prefer paper support, we see in the last 1-2 years a huge shift towards AI based tools, especially for school assignments and countries with greater access to tech.

Based on several recent studies and surveys, we can estimate that up to 40% of US students - across both secondary and higher education - have used AI-based educational tools. To illustrate this shift more concretely, several key surveys can be highlighted below: a) Global Trends: A global survey conducted by the Digital Education Council (reported by Campus Technology, 2024) [

2] found that 86% of students use AI for their studies. This study - spanning multiple countries including the US, Europe, and parts of Asia - highlights widespread global adoption; b) United States Surveys: In the United States, an ACT survey [

3] of high school students (grades 10-12) reported that 46% have used AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT) for school assignments. A survey by Quizlet (USA, 2024) [

51] indicates that adoption is even higher in higher education - with about 80-82% of college students reporting they use AI tools to support their learning; c) Additional Studies - Additionally, a quantitative study [

4] involving higher education institutions globally found that nearly two-thirds (approximately 66%) of students use AI-based tools for tasks such as research, summarization, and brainstorming.

Together, these findings suggest that while usage rates vary by education level and region (with higher rates in the US), there is a continuing global trend towards integrating AI-based educational tools in schools and universities.

2.5. Chatbots in education

2.5.1. Chatbots: Definition and Classification

A chatbot application is in simple terms any application, usually web-based, which can chat with a person in a similar way a human does, being able to answer user questions and follow the history of the conversation.

Chatbot applications can be classified [

52] on distinct attributes such as: domain of knowledge, services provided, objectives (goals) and response generation and responses generated [

53], as summarized in

Table 1. Each classification method highlights specific characteristics that determine how a chatbot operates and interacts with users, as detailed in

Table 1.

Based on the knowledge domain the apps can access, we classify the chatbots as open(general) and closed knowledge domain bots. Open chatbot applications address general topics and answer general questions (like Siri or Alexa). On the other hand, closed chatbots have specific knowledge domains to provide answers to questions from different domains [

53]. The specialized service type applications provide users with services in a friendly and fast way, such as online customer service, banking service, weather information service, etc.

Based on the services provided, chatbot applications can provide interpersonal, intrapersonal, and inter-agent services [

54].

Based on the fulfilled goal, bots can be split into informational, conversational, and activity-based services.

The last category includes chatbot applications that accept input, process, and generate responses [

55]. Other chatbot applications in this category are hybrid chatbot applications that use natural understanding and rules that process inputs and generate outputs [

53].

2.5.2. Chatbots: Structure and role in education

A chatbot is an application, implemented programmatically or leveraging Generative AI [55, 56], that understands and answers questions from human users (or chatbots) in natural language [

57] on a particular topic or general subject, by text or voice [58, 59].

Figure 1 illustrates the general workflow for interacting with a chatbot that integrates Natural Language Processing (NLP) with a knowledge base retrieval system. The process begins when the chatbot receives input from the user - whether as text, voice, or both. This input is then converted into text and forwarded to the NLP component, which processes and comprehends the query. The response area uses different algorithms to process the existing knowledge base, then provides a variety of responses to the response selector. In this data processing step, the answer selector uses machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms to be able to choose the most appropriate answer for the input [

60]. The current trend is to move towards a more streamlined system that consolidates the process into fewer steps (Question - AI Model - Response), albeit at a higher cost per question, as shown in

Figure 1b.

2.5.3. Educational Chatbots survey

In the subclass of specialized service-oriented applications [

57] we can include the Educational Chatbots. We present a short review of the most common educational chatbots in

Table 2.

As seen above, the reach of AI in education is high and increasing. Still, we face major barriers, such as:

- 6.

Insufficient training and digital literacy among educators - for instance, Ravšelj et al. (2025) [

4] found that many higher education teachers across several countries felt unprepared to fully leverage AI due to inadequate institutional training and support.

- 7.

High implementation costs, especially in institutions with lower resources [

68].

- 8.

Lack of clearly defined and easily applicable policies for the ethical adoption of AI components as well as concerns about data privacy and fears of algorithmic bias.

These obstacles foster skepticism, and they need to be addressed for the effective introduction of AI tools in education.

We reviewed the split of different supports in education and presented the benefits and challenges of computer-aided AI solutions for Education. These limitations can be overcome by the AI-enabled open-source framework we propose in

Section 3.

3. Materials and Methods

Proposed solution Description

Traditional educational approaches often struggle to address the diverse needs of individual learners, particularly in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) domain. Limited instructor availability, inconsistent feedback, and a lack of personalized learning experiences can hinder student progress and engagement [

69]. To address these challenges, we developed an AI-powered teaching Assistant designed to improve the learning process in university-level programming courses. This framework is open-source and can be used by any instructor and student without any technical skills required.

3.1 High Level Description

Our application consists of four student modules and two supervisor/teacher modules.

Student-facing modules

Module 1 - AI Teaching Assistant. In this module the student has access to the course material and to an AI-assistant (chatbot) who can answer questions related to the contents of the course material.

Module 2 - Practice for Evaluation. In this module students can prepare for the Final Assessment using "mock assessments", where the questions generated by the AI are similar to, but different from those of the Final Assessment. The student is tested on multiple-choice questions, open-text questions, and specific tasks (for example computer programming). The AI Evaluator provides immediate feedback on student's answers, suggesting improvements and providing explanations for correct answers. It is worth mentioning that the AI Evaluator can also redirect students to Module 1 to review the relevant course information and seek further clarification from the AI Assistant.

Module 3 - Final Evaluation. After students complete several Practice Evaluations, they have the option to take the Final Evaluation. The module is similar to the Practice for Evaluation module, but it represents the “real exam” - questions are created by the teacher (or AI generated and validated by the teacher), graded by the AI Evaluator, and the final grades are transcribed in the official student file. The feedback and grades can be provided instantly or be delayed until the teacher double-checks the evaluation results.

Module 4 - Feedback. This module allows students to provide optional feedback related to their experience using this AI application. This feedback is essential for further development and improvement of this framework.

Supervisor modules

Module 5 - Setup. Teachers are provided with a simple interface allowing them to:

- 9.

add a new course.

- 10.

drag-and-drop the Course Chapters documents (in PDF, DOC or OPT format)

- 11.

drag-and-drop a document containing Exam questions or opt for automatic exam question generation.

- 12.

optionally upload excel files with previous year's student results for statistical analysis.

Module 6 - Statistics. This module extracts statistics on the year-on-year variation of students' results. We use it to evaluate the efficiency of this teaching method vs the previous year’s results in the classical teaching system (See Section 4.13).

3.2. Description of the User Interface

The user interface of our application is presented below in

Figure 2:

The UI is divided in three frames as shown in

Figure 2 UI: the left frame for navigation, the center frame for displaying the course material (PDFs) or exam questions and the right frame for accessing the AI Assistant or AI Evaluator.

Depending on the module he chooses, the UI provide the following functionalities:

- Module 1 - AI Assistant: In this module the student selects in the left frame one of the course chapters which is displayed in the center frame. Then, the student can ask the AI Assistant questions about the selected chapter in the right frame.

- Modules 2 and 3 - Preparation for Evaluation/Final Evaluation: These modules share a similar UI and present students in the middle

frame exercises, questions, and programming tasks. In the right frame, the chatbot provides feedback on student responses or links to Module 1 so the student can review the Course documentation.

- Module 4 - Feedback Survey: The center frame displays a form for evaluating the application.

3.3. Architecture details of the platform

In this section we provide a detailed description of the architecture of our solution (See

Section 3.3.1) and details of the AI Components architecture (See

Section 3.3.2)

3.3.1. General Software Application Architecture and Flow

The application leverages a multi-layered architecture comprising a Frontend, a Backend, and external services, orchestrated within a containerized environment.

The architecture is highly modular, with clear separation of roles between Frontend, Backend, and LLM components. This allows for easy extension and modification (e.g., changing the LLM).

The solution can be deployed via Docker on any server, in our case being deployed on a Google Cloud CloudRun [

70] instance. Docker is a packaging concept which simplifies deployment and ensures consistent behavior across different environments.

To understand the architecture of the application, we exemplify in

Figure 3 the main components of the application and the usual dataflow in the case of the Module 1. Briefly, the students ask a question to the Frontend (UI) component of the Application which runs in a Docker Container in Google Cloud. The question is processed by Backend, augmented with the course relevant context, then processed by an external LLM, and the answer is sent back to the student.

3.3.2. AI Components / Modules Architecture

The AI components are implemented in Modules 1, 2 and 3 of the Backend components.

Module 1 - AI Assistant

To maintain its independence on any LLM provider, the backend architecture for Module 1 is centered around 3 base concepts:

- 1.

LLM Protocol - an interface which describes the minimal conditions that a LLM needs to implement to be usable - in this case it should be able to answer a question

- 2.

RAG Protocol - an interface which describes what the Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) pattern should implement. The main idea [

71] is to use a vector database to select possible candidates from the documentation (PDF course support) which are provided as context to an LLM so it can answer the student question. The objects implementing the Rag Protocol provides functions for:

- 13.

Retrieves-context - given a question is able to retrieve the possible context from the vector DB.

- 14.

Embedding Generation - helper function to convert (embed) text into vector representation.

- 15.

Similarity Search - performs similarity searches within the vector store database to find the most relevant chunks.

- 3.

LLM RAG - a class which contains:

- 16.

An object ‘rag’ which implements the RAGProtocol (for example RAGChroma) to store and retrieve relevant document chunks (content) for the question.

- 17.

A function to augment the question with the context recovered from the ‘rag’ object.

- 18.

An object ‘llm’ which implements the LLMProtocol (for example LLMGemini) to answer the augmented question.

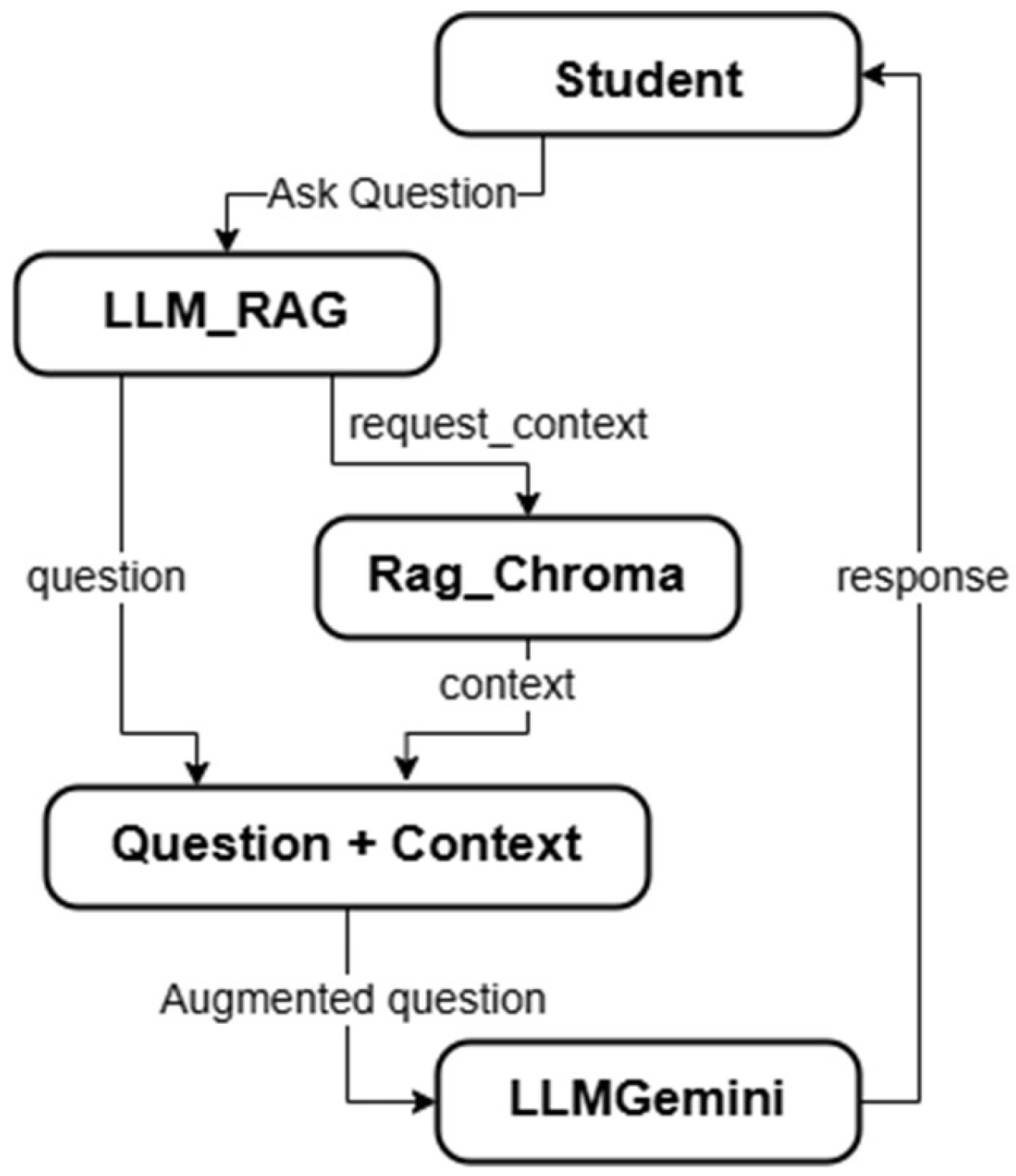

The flow of a question in LLM-RAG is shown in

Figure 5. The question from a student is sent to LLM_RAG. In turn, the LLM RAG calls the component RAG Chroma for context. The LLM_RAG then creates an augmented question in a format similar to "Please answer {question} in the context {context extracted by rag}". This question is sent to the LLMGemini component, and the answer is sent back to the student, eventually enhanced with snippets from the course material.

Module 2 - AI Practice for Evaluation and Module 4 - AI Evaluation

Both Modules 2 and 3 are implemented around the Evaluator Protocol concept - an interface which describes how an Evaluator (Judge) should grade 1 question and the feedback it should provide to the student, similar to the concept of LLM as a Judge presented in HELM, Ragas [72, 73].

The evaluator Protocol implementations are providing functions for evaluating user responses including:

- 19.

Evaluate Answer: Compares user's free text or single-choice answers with correct answers.

- 20.

Evaluate Code Answer: Executes user-provided code snippets and compares them against correct code.

- 21.

Calculate-Score: Calculates the overall score based on a list of responses.

3.4. Technical Implementation of the platform

We present the details of the technical implementation of our platform. As outlined in the general architecture

Section 3.3, the application is divided into Frontend and Backend which are packed in a Docker image deployed over Google CloudRun. We utilize an instance with 8GB of memory for tests, but 2GB should be enough for normal usage.

All components are a combination of standard Python code and LLMs prompted specially to be used in question / answer, evaluator, or assistant mode.

3.4.1 Front-end implementation

The Frontend is based on Streamlit, an open-source Python framework used for building and deploying data-driven web applications.

The frontend component implements the following:

- 22.

Session Management: Manages user sessions and state. This includes handling Google OAuth 2.0 authentication.

- 23.

User Interface: Provides the user interface for interaction, including chapter selection, course navigation, dialog with the AI, evaluation, and feedback surveys:

a. Navigation: Uses a sidebar for primary navigation, allowing users to select chapters/units and specific course materials.

b. Dialog Interaction: Renders a dialog zone where users interact with the AI Assistant. This includes input fields and display of AI responses.

c. Evaluation Display: Presents evaluation results to the user.

d. Styling: Streamlit themes and custom CSS.

3.4.2. Backend Implementation

The Backend is modular and implements all components described in 3.1, with differences between Modules 1-3 (AI) and 4-5-6 (Feedback, Setup and Statistics).

Modules 1-3 implement the AI components. To implement the LLM Protocol we used as backbone mainly Gemini versions 1.0, 1.5 Flash, 1.5 Pro, 2.0 Flash and 2.0 Pro [74, 75, 76] from Google Vertex AI [

77], but we also tested ChatGPT and Claude Sonnet [78, 79].

For the LLMRAG we used a Chroma DB implementation, but Microsoft Azure AI Search [

79] or Vertex AI Search [

80] could be substituted on preference.

The implementation of the Evaluator Protocol is also a custom-made class, similar to LLM-as-a-judge [

81], using Gemini 2.0 as a backbone.

Modules 4-5-6 (Feedback, Setup and Statistics) are implemented in python, with SQLite database for storing the course content, exam questions and student list, grades and feedback. Statistics graphs are generated using the plotly [

74] and pandas [

75] packages. Feedback is implemented with Google Forms, although any other similar option can be integrated.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Description of the experiments

We performed 2 types of experiments: a) In the first set of experiments, a cohort of students enrolled in 4 pilot courses (See

Section 4.1.1) and instructors (See Section acknowledgements) assessed the quality of the platform as an AI Assistant and Evaluator on a range of criteria described in

Section 4.2; b) In the second set of experiments we evaluated the correctness and faithfulness of the AI components answers on a set of classic LLM metrics, see

Section 4.3.

The statistics extracted from the results of the cohort of students will constitute a third experiment which will be reported in a new paper at the end of the courses.

4.1.1 Pilot Courses evaluated on our Solution

For our study we used the four courses presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Courses description.

Table 3.

Courses description.

| Course |

Semester |

ECTS |

hours |

Year |

| Databases (DB) |

4th |

4 |

56 |

2020-2025 |

| Database Programming Techniques (DBPT) |

5th |

5 |

56 |

2020-2025 |

| Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) |

3td |

6 |

70 |

2020-2025 |

| Designing algorithms (DA) |

2nd |

4 |

56 |

2021-2024 |

These courses are part of the Undergraduate program in Automatics and Applied Informatics offered by the Faculty of Engineering of the Constantin Brancusi University (CBU) of Targu-Jiu, located in Romania.

The first two courses are linked, as the first covers introductory SQL topics in the field of database design and administration and the second course extends to techniques for designing applications that process databases in PL/SQL language. In CBU's, these are the first contacts of the student with databases. In the third course students learn the Java programming language, and in the fourth course students focus on applied programming techniques for software development.

Throughout those courses, students receive both theoretical and practical learning materials and participate in practical laboratory activities where they work on hands-on tasks.

Our research presents the usability and reliability of the proposed AI framework when applied to these courses.

4.1.2 Sample

The cohorts of students enrolled in the Pilot courses in the new academic year and their distribution is summarized in the

Table 4 below:

Students who did not pass out these courses in previous years were not included in this research, so we ensured that the students in the sample had no prior knowledge of the subject.

4.1.3. Description of the classical teaching process

To establish a baseline, we will describe the traditional teaching process for the courses involved in this study.

Each course consists of weekly lectures and practical laboratory sessions, both lasting two hours over a 14-week period. After each lecture, in which theoretical notions are presented with useful examples, students participate in practical laboratory activities. During these sessions in the laboratory, they individually execute the code sequences demonstrated in the lecture and then solve additional tasks based on the presented concepts.

After seven weeks, students take a 60-minute mid-term assessment, with the goal of keeping them motivated on continuous learning and to be able to identify those struggling early.

The mid-term assessment has two parts: a) 15 minutes for ten single-choice questions; b) 45 minutes are allotted for two coding exercises directly on the computer.

The final exam, at the end of the 14 weeks of course, takes 120 minutes and is structured similarly: a) 40 minutes for 20 single-choice questions; b) 80 minutes for two coding exercises.

Following the final exam, students are asked to fill in a questionnaire on how they have used the teaching materials and also evaluate the teaching assistant. In this way the effects of these traditional teaching resources such as textbooks, books, problem books, both in print and on the web are to be highlighted.

It is worth mentioning that during this final assessment, students are monitored by the lecturer and the teaching assistant and are advised to use only the materials previously presented in the lectures and in the laboratory activities. The use of messaging applications and AI tools, such as ChatGPT, is not allowed during the classical assessment.

4.1.4. Description of the AI enhanced teaching process (Pilot)

In this pilot experiment, the AI-framework is added as an additional support to the existing classical teaching process. So, in addition to the lectures and laboratory, the students will have access to our platform. They will use it to reread the course, ask questions to the AI Assistant (Module 1) and prepare for the evaluations in Module 2 - Prepare for Evaluation. The mid-term and final evaluation will be passed and graded in Module 3 - Evaluation, and the student feedback will be recovered in Module 4 - Feedback.

4.2. Results – Evaluation of the platform by Instructors and Students

The experiment has been launched this year with the students enlisted in the 4 Pilot courses described in

Section 4.1.2 and a cohort of 7 High School and 10 University Teachers to assess the quality of the proposed learning platform. We present the summary of assessments of the students and instructors involved.

4.2.1 Perceived advantages and disadvantages for Instructors

In the first phase, the framework and the web application were evaluated by the instructors mentioned in the Acknowledgements section. They assessed the application based on the criteria listed in

Table 5 and were also asked to also provide open-ended feedback.

Below is the prevalent freeform feedback recorded from the teachers:

- 24.

This application greatly simplifies the migration of their existing course material to an online / AI-enhanced application - an obstacle which was insurmountable in their opinion before being presented to this framework.

- 25.

The ability to deploy the application on a university server or cloud account avoids many of the issues related to student confidentiality.

- 26.

They appreciate the reduction in the time for simple questions and grading which permits them to focus on more difficult issues.

4.2.2. Perceived advantages for the students

We used the feedback form to get initial student feedback to the questions in

Table 6:

Additionally, we extracted the following free-form feedback:

- 27.

Students consider that a major benefit of this platform is that they can ask any question they might hesitate to ask during class (so-called “stupid-questions”) while having the same confidence in the answer as if they were asking a real teacher.

- 28.

They appreciate that each answer highlights the relevant sections in the text, which increases their confidence in the AI Assistant answer.

- 29.

They appreciate that the application can be used on mobile phones – for example during commute or in small breaks.

4.3. Results – Testing of the AI components of the platform

To test the performance of the AI modules we used a dataset composed of:

16 single-choice questions from previous exams

40 free-answer questions

-

16 questions from previous exams (Manual Test1 & Test2) same as the single-choice from above, but we deleted the possible answers and asked the AI to answer in free form

-

24 questions generated with o3-mini-high with low, medium, high difficulty settings.

Table 7.

Test Data.

| Source |

Difficulty |

Questions No |

Type |

| Manual Test1 (2023 Exam) |

1 |

8 |

Single choice |

| Manual Test2 (2023 Exam) |

1 |

8 |

Single choice |

| O3-mini-high |

1 |

6 |

Free answer |

| O3-mini-high |

2 |

6 |

Free answer |

| O3-mini-high |

3 |

6 |

Free answer |

For single-choice answers obtain 100% answer correctness if the context was properly extracted by the RAG, so the rest of the analysis is focused on more difficult free answer questions.

4.3.1. AI Assistant (Module 1) Assessment

The Assistant was graded both manually and using Ragas [81, 82], a specialized library for evaluation of RAG type specialized assistants.

Manual tests. For the manual tests we evaluated only the final answer, with 2 human experts which were both familiar with the course material. We evaluate a single metric “answer_correctness”, in a binary mode (correct or incorrect). Incomplete answers were labeled as incorrect. Due to inherent subjectivity in interpreting answers, as well due to human error when handling large sets of data (250 rows), the initial evaluations on the same questions were different in about 5% of the cases (95% consistency). These inconsistencies were discussed and the agreed answers were considered correct.

Automated tests. The Assistant was evaluated automatically against 2 types of metrics [81, 82]:

- 1.

Retrieval (Contextual) Metrics, i.e. whether the system “finds” the right information from an external knowledge base before the LLM generates its answer. The metrics used were:

- 30.

Context Precision - measures whether the most relevant text “chunks” are ranked at the top of the retrieved list.

- 31.

Context Recall - evaluates whether all relevant information is retrieved.

- 2.

Generation Metrics i.e. whether the LLM must have an answer that is not only fluent but also grounded in the retrieved material. The metrics we employed are:

- 32.

Answer Relevancy - how well the generated answer addresses the user’s question and uses the supplied context. It penalizes incomplete users or unnecessary details.

- 33.

Answer Faithfulness - whether the response is factually based on the retrieved information, minimizing “hallucinations”, estimated either with ragas or human evaluation.

- 34.

Answer Text Overlap Scores (conventional text metrics BLEU, ROUGE, F1 [

82]) - compare generated answers against reference answers.

We compared the results using 5 different LLM backbones, from Gemini 1.0 to Gemini 2.0 Pro. All LLMs perform well in terms of answer correctness - matching or surpassing the human experts (

Table 8).

Further we present in

Figure 6 a split on Question Difficulty and the question generation (AI or Manual).

The analysis of the results (

Figure 6) leads to these main conclusions:

Correctness is very high for all LLMs, with results on par with 1 expert.

The Answer Relevancy results are very promising as well, having mostly scores above 80% relevancy, being observed by human raters in the HELM study [

83].

Context retrieval is very important - results are better when more context is provided - expected and natural [

82].

Faithfulness we extract 2 trends: a) The faithfulness is better for higher difficulty questions; b) Faithfulness increases for newer LLMs, Gemini 2.0 Pro being the best. Gemini 1.0 and 1.5 will sometimes ignore the instruction to answer only from context.

Older Metrics are not relevant: NLP (Non LLM) metrics like ‘ROUGE’, ‘BLUE’, ‘factual correctness’ are not any more suited for evaluation of assistant performance (see

Appendix A.1 with full results and [

83]). The main explanation is that two answers can correctly explain the same idea and obtain a high answer relevancy but use very different words which will put bleu. rouge and factual correctness to very low.

We will provide below a detailed discussion of the correctness, relevancy, faithfulness and context retrieval in the context of the AI Assistant.

Correctness and Relevancy.The correctness of the answers is on par or better than expert level, the relevance also is on par with HELM [

83] - we observe here just the fact known in the last 6 months → that LLM solutions are now on par or better with human Experts in most domains.

Faithfulness. The analysis of faithfulness helped us understand an initially puzzling result in the raw data, in which Gemini 1.0 was giving better results than Gemini 2.0, although only by a very small margin. After observing the faithfulness graphs, we noted that Gemini 1.0 and 1.5 generations of models are not as faithful as expected, the main reason being that they did not respect the instruction given in the prompt “Please do not answer if the answer cannot be deduced from the context received”, while Gemini 2.0 is way better at reasoning and respecting instructions. After closer analysis of the cases where Gemini 1.0 and 1.5 answered correctly, but Gemini 2.0 did not provide a response, we found that the information was not present in the retrieved context and actually Gemini 1.0 and 1.5 were responding from their own knowledge, without respecting the prompt to answer “only from the provided context”. Thus, the actual “correct” response in the given context was provided by Gemini 2.0.

We retested and confirmed this hypothesis by adding a set of questions which were not related to the given class document. While the RAG extracted no context, Gemini 1.0 and 1.5 gave answers to more than 60% of the questions which should have not been answered, while Gemini 2.0 correctly responded that “I am not able to answer in the context of this class”. We removed such cases from the rest of the analysis, but these cases are saved and can be found in the raw data (link in Annex 1).

Context retrieval. Context retrieval is very important for RAG LLMs, so we dedicated a small section to describe the result. It makes possible the utilization in specific context, and it reduces the costs because it includes only the relevant context in the prompt sent to the LLM.

We tested here with two methods: one with chunks limited to 3000 tokens and one with pages, usually limited at 500 tokens.

In our cases extraction of context with chunks of 3000 tokens with an overlap value of 300 tokens was always superior to pages. This outcome was most likely because we have 6 times more context and because sometimes ideas are split on two or more pages.

The results in

Figure 7 are showing: a) the correct answers of the system drop by 5-7%, with a higher drop on more difficult questions; b) the metric “context recall” measured by ragas drops drastically with smaller context.

We are aware that our RAG framework has room for improvements and we will update it constantly in the future. By improving it the results will be more satisfactory and the costs will be reduced as less but more relevant context is sent to the LLM.

4.3.2. AI Evaluator Assessment (Module 2 and 3)

To assess our AI Evaluator, similar to [

84] and following the best practices mentioned on [

85], we used the same 16 single-choice and 40 free-answer questions to which we added reference answers (ground truth) and student answers. With this setup built, we performed manual and automatic evaluation.

The results of the Evaluator grading:

In manual mode (using 2 human expert):

- 35.

Evaluator grading to free form questions: correctness 90%.

- 36.

Evaluator grading to single-choice questions: correctness 100%.

- 37.

Relevancy of Evaluator suggestions to wrong questions: relevance 99%.

In automatic mode (by using ChatGPT O1 as a judge)

- 38.

Comprehensiveness (whether the response covers all the key aspects that the reference material would demand): 75%.

- 39.

Readability (whether the answer is well-organized and clearly written): 90%.

4.3.3 Common benchmarks

Certain considerations, such as stability and language effect, apply to both the Assistant and Evaluator, so we present them separately.

Stability and faithfulness. The platform is finetuned to optimize: a) Answer quality – it is instructed to respond “I am not able to answer this question in the class context” if it is unsure about its answer; b) Stability and consistency – we set the LLM temperature to 0 and steps to 0 to reduce the variability in the LLM answer [

86].

We evaluate the stability by rerunning the same 10 questions 10 times. As all answers were equivalent, we estimated the instability to be below 1%.

Translation Effect. We observe a small effect on changing the languages (our first test was a class in Romanian. Still, this effect is almost nonexistent for newer LLM backbones (almost unmeasurable for Gemini 2.0), as these backbones are improving their multi-language ability [

87].

Still there are two important effects on the RAG Component: a) First, you need an embedding model which is multilanguage. We used distiluse-base-multilingual-cased-v2 embeddings [

88] to accommodate content in all languages; b) Second, if the Course documentation is in English, and the question is in French, the vector store would be unable to retrieve any relevant context.

To address this, we have a few options which can be implemented: 1) Require that the questions are in a fixed language (usually the same language as the course documentation) – configured by default; 2)Translate each question to the language the class documentation is in; 3) Have all the class documentation in the database translated in a few common languages at the setup phase.

4.3.4 Summary of LLM results

We obtained 100% correct answers on single-choice questions and 95-100% correct answers on free-form results, which surpass human-expert level. We observe that the performance is strongly influenced (>10%) by the context retrieval performance.

Based on the reported results of the application performance, we consider that this application can be used in the current state for high-school and University level.

Going forward, we can focus our improvements on three directions: 1) Improve RAG performance to ensure that the LLM receives all relevant context for the questions; 2) Reduce LLMs costs by providing only the relevant context; 3) Upgrade to better performing LLMs.

5. Discussion

From our review study we find that AI Assistants and AI Evaluators are a useful and needed addition to the classical teaching methods (See

Section 2).

The implementation’s accuracy/faithfulness of our proposed solution (See

Section 3) is more than satisfactory with current LLMs (See

Section 4.3) and its usefulness and ease of use was evaluated as excellent by both instructors and students (See

Section 4.2).

While the introduction of this framework as an extension to classical courses seems both beneficial and needed, we still have to consider the obstacles to adoptions (See

Section 2.5) - mainly the technical adoption barrier, costs, competing solutions and legal bureaucracy.

5.1. Technical adoption barrier

This application was designed to be very easy to use and adapted for any non-technical user, in particular because its deployment is a “One Click” process and its UI is designed with intuitiveness in mind. The feedback of the instructors and students (See

Section 4.2) confirm that we achieved this goal and that the application is easily accessible for even the least technical person.

5.2. Cost analysis

This app is open source and free to use by any university. Still, there are two main costs: for hosting the platform and for LLMs usage.

As shown in

Section 3.4 the app requires an instance with at least 2GB of memory. This can be found in almost any university and is usually offered in the free tier for most cloud providers.

To evaluate the LLMs cost we consider that in standard STEM courses we have 15 Chapters of lecture with 3 Evaluations for each one and roughly 50 students who might ask 10 questions per Chapter, adding up to ~10k questions. To answer each question, the RAG will augment each question (originally 50 tokens/word) to around 1000 tokens long and provide an answer of around 50 tokens long, resulting in ~10M input tokens and ~45k output tokens.

In Table 9 we present a detailed comparison table of the LLMs related cost for the main models on the market for the above case.

Table 9.

Estimated Costs for existing LLMs for 1 Course (10M input tokens, 45K Output tokens).

Table 9.

Estimated Costs for existing LLMs for 1 Course (10M input tokens, 45K Output tokens).

| Model Variant |

Cost per 1M Input tokens |

Cost per 1M Output tokens |

Cost for 10M Input tokens |

Cost for 45K Output tokens |

Total Estimated Cost |

| Gemini 1.5 Flash |

$0.15 |

$0.60 |

$1.50 |

$0.03 |

$1.53 |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro |

$2.50 |

$10.00 |

$25.00 |

$0.45 |

$25.45 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash |

$0.10 |

$0.40 |

$1.00 |

$0.02 |

$1.02 |

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet |

$3.00 |

$15.00 |

$30.00 |

$0.68 |

$30.68 |

| Chat GPT-4o |

$2.5 |

$20 |

$25.00 |

$0.2 |

$25.2 |

| DeepSeek (V3) |

$0.14 |

$0.28 |

$1.40 |

$0.01 |

$1.41 |

| Mistral (NeMo) |

$0.15 |

$0.15 |

$1.50 |

$0.01 |

$1.51 |

We see that one the best solutions we tested (Gemini 2.0) gives a cost/course of only 1

$. While this might still be a barrier in some demographics, these costs are only dropping exponentially, with the cost/token reduced in half every 6 months [

84]. Furthermore, we plan to establish a collaboration which will sponsor at least some of these costs.

5.3. Competing solutions

We investigated whether this solution can bring any benefit with respect to the existing solutions. We compare the most important existing Computer or AI assisted teaching solutions in

Table 10.

Compared to existing solutions, our framework advantages are low cost, ease of setup, facility of utilization, and the integration of AI Assistant / Evaluator. This space of low-cost, open source, AI educational solutions which our framework is targeting is practically not addressed by any of the existing applications which makes us think that the launch of our platform is both needed and beneficial.

5.4. Legal and Governance issues

There are still gaps in the legislation and policies related to the usage of AI in student education and the confidentiality of the student data. These gaps are being addressed in each country in the latest years, and should be reduced progressively in the near future. Still, we consider that most of these impediments are avoided in our application because the students are already enrolled in the high-school or university courses.

Therefore, we think our application has an advantage over all existing educational platforms, whether in cost, technical adoption, policy barriers or possible reach. We estimate that this framework can reach more than 90% of the world's students and instructors, including demographics otherwise unreachable by existing solutions.

As a next step we propose to give as much of an exposure to our proposed application, most probably in the form of a collaboration with public and private institutions, to make it available for free in any high-school and university. Results obtained at the end of the Pilot phase will help us better quantify the effect on the student results (improvement in grades, time spent learning, etc.) and will contribute to the adoption of the platform.

6. Conclusion

We evaluated the current status of computer-aided methods in education, including AI approaches. We AI methods offer significant benefits, but there are major barriers to their adoption related to costs and technical literacy of the instructors.

To address these challenges, we created an easy-to-use AI framework, composed of an AI Assistant and AI Evaluator. This platform enables instructors to migrate existing courses with a simple drag-and-drop operation, effectively overcoming the “technical literacy” barrier. It provides a wide range of advantages (See

Section 4.2) such as near 100% accuracy (See

Section 4.3), high consistency, low costs (estimated at 1

$/year/class) and fewer policy barriers as it is an open-source solution which can be fully controlled by the educational institution. From the student perspective, it has significant advantages such as 24/7 availability enabling a flexible learning schedule, mobile device accessibility, increased answer accuracy and consistency and a lowered teacher-student barrier.

Our solution compares positively with all existing solutions. The combination between the AI-enhanced learning experience, low-cost maintenance, open-source licensing and excellent performance makes us strongly believe that this application can see widespread adoption in the coming years, contributing significantly to the democratization of the educational system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and A.B.; methodology, A.R. and A.B.; software, A.R., A.B. and L.G.; validation, A.R., A.B. and L.G.; formal analysis, A.R. and A.B.; investigation, A.R., A.B., M.-M.N., C.C. and L.G.; resources, A.R., A.B. and L.G.; data curation, A.R., A.B. and L.G.; writing - original draft preparation, A.R., A.B., I.B., L.G. and A.B.; writing - review and editing, A.R., A.B., I.B., L.G., M.-M.N., C.C. and A.B.; visualization, A.R., A.B., M.-M.N., C.C. and L.G.; supervision, A.R., A.B., I.B., L.G. and A.B.; project administration, A.R., A.B. and L.G.; funding acquisition, A.R., A.B., I.B., L.G., M.-M.N., C.C. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

We thank the following instructors for their contribution in the evaluation of the framework: A.B., A.R., L.G., A.B., I.B. M.-A.R., L.-G.L., F.G. A.L., G.G., M.I., M. N., R.S., M.R., A.I., A.L. We thank the students involved in the 4 pilots described in Section 4.1.2.We acknowledge the help of Prof. Emanuel Aldea (Paris Sud University, FR) for his review and improvement suggestions on several versions of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AI

SQL |

Artificial Intelligence

Structure Query Language |

LLM

CAME

CAI |

Large Language Model

Computer-Assisted Methods in Education

Computer Assisted Instruction |

CEI

VR

AR |

Computer Enhanced Instruction

Virtual Reality

Augmented Reality |

LMS

NLP

ChatGPT

Gemini

Claude

LLAMA

LLMProtocol

RAG

RAGProtocol

LLMGemini

Claude Sonnet

VertexAI

ECTS |

Learning Management Systems

Natural Language Processing

Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer developed by OpenAI

generative artificial intelligence chatbot developed by Google

a family of large language models developed by Anthropic

a family of large language models (LLMs) released by Meta AI

Large Language Model Protocol

Retrieval Augmented Generation

Retrieval Augmented Generation Protocol

Large Language Model Gemini

Claude 3.5 Sonnet

Vertex AI Platform

European Credits Transfer System |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Full results from the Module 1 evaluation ob chunks and pages RAG strategy.

Table A1.

Full results from the Module 1 evaluation ob chunks and pages RAG strategy.

| Row Labels |

Average of corect |

context_recall |

faithfulness |

answer_relevancy |

bleu_score |

Rouge Score |

FactualCorrectness |

| chunks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| gemini-1.0-pro |

95.00% |

81.25% |

71.85% |

86.39% |

8.34% |

22.99% |

56.00% |

| gemini-1.5-flash |

97.50% |

82.50% |

74.13% |

87.09% |

14.85% |

31.00% |

57.11% |

| gemini-1.5-pro |

97.50% |

83.75% |

74.38% |

83.31% |

13.40% |

35.69% |

43.77% |

| gemini-2.0-flash |

100.00% |

77.50% |

82.92% |

84.82% |

15.08% |

35.93% |

46.85% |

| gemini-2.0-pro |

97.50% |

82.50% |

87.61% |

85.12% |

10.01% |

24.76% |

44.40% |

| pages |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| gemini-1.0-pro |

|

47.08% |

74.05% |

45.12% |

3.09% |

32.04% |

21.85% |

| gemini-1.5-flash |

|

47.08% |

57.83% |

74.76% |

7.81% |

20.64% |

47.13% |

| gemini-1.5-pro |

|

47.08% |

55.26% |

83.79% |

5.70% |

16.87% |

39.73% |

| gemini-2.0-flash |

|

47.08% |

88.79% |

69.63% |

4.35% |

17.42% |

33.75% |

| gemini-2.0-pro |

|

47.08% |

87.78% |

78.15% |

3.83% |

14.45% |

39.45% |

| Grand Total |

97.50% |

64.29% |

75.47% |

77.82% |

8.65% |

25.18% |

43.28% |

Appendix A.2

Full data used for tests can be found at:

References

- Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action, for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Survey: 86% of Students Already Use AI in Their Studies. Available online: https://campustechnology.com/articles/2024/08/28/survey-86-of-students-already-use-ai-in-their-studies.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Half of High School Students Already Use AI Tools. Available online: https://leadershipblog.act.org/2023/12/students-ai-research.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Dejan Ravšelj, Damijana Keržič, Nina Tomaževič, Lan Umek, & Nejc Brezovar (2025). Higher education students' perceptions of ChatGPT: A global study of early reactions. PLOS ONE. [CrossRef]

- How to Use the ADDIE Instructional Design Model – SessionLab. Available online: https://www.sessionlab.com/blog/addie-model-instructional-design/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- 2023 Learning Trends and Beyond - eLearning Industry. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/2023-learning-trends-and-beyond (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Learning management system trends to stay ahead in 2023 - LinkedIn. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/learning-management-system-trends-stay-ahead-2023-greenlms (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gamification Education Market Overview Source. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/gamification-education-market-31655?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- eLearning Trends And Predictions For 2023 And Beyond - eLearning Industry. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/future-of-elearning-trends-and-predictions-for-2023-and-beyond (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- AI Impact on Education: Its Effect on Teaching and Student Success. Available online: https://www.netguru.com/blog/ai-in-education (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Introducing AI-Powered Study Tool. Available online: https://www.pearson.com/en-gb/higher-education/products-services/ai-powered-study-tool.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: The State of the Field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ouyang, F. The application of AI technologies in STEM education: A systematic review from 2011 to 2021. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzhikoleva, S.; Rachovski, T.; Ivanov, I.; Hadzhikolev, E.; Dimitrov, G. Automated Test Creation Using Large Language Models: A Practical Application. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, T.N.; Halimah, L. The Value and Technology: Maintaining Balance in Social Science Education in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Social Sciences in Education, Bangkok, Thailand, 14–16 November 2024; Volume 1, pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez, J.M.; Lantada, A.D. Artificial intelligence aided engineering education: State of the art, potentials and challenges. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 36, 1740–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Darayseh, A.A. Acceptance of artificial intelligence in teaching science: Science teachers’ perspective. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, G.; Le Moine, O. Artificial intelligence in medicine: Today and tomorrow. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandlhofer, M.; Steinbauer, G.; Hirschmugl-Gaisch, S.; Huber, P. Artificial intelligence and computer science in education: From kindergarten to university. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Erie, PA, USA, 12–15 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edmett, A.; Ichaporia, N.; Crompton, H.; Crichton, R. Artificial Intelligence and English Language Teaching: Preparing for the Future. British Council. 2023.

- Hajkowicz, S.; Sanderson, C.; Karimi, S.; Bratanova, A.; Naughtin, C. Artificial intelligence adoption in the physical sciences, natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences and the arts and humanities: A bibliometric analysis of research publications from 1960–2021. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y.; Nakamura, K. A bidirectional LSTM language model for code evaluation and repair. Symmetry 2021, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollny, S.; Schneider, J.; Di Mitri, D.; Weidlich, J.; Rittberger, M.; Drachsler, H. Are we there yet?- A systematic literature review on chatbots in education. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 654924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y.; Rage, U.K.; Nakamura, K. A novel rule-based online judge recommender system to promote computer programming education. In Proceedings of the Advances and Trends in Artificial Intelligence. From Theory to Practice: 34th International Conference on Industrial, Engineering and Other Applications of Applied Intelligent Systems, IEA/AIE 2021, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26–29 July 2021; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y.; Nakamura, K. Source code assessment and classification based on estimated error probability using attentive LSTM language model and its application in programming education. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y.; Kiran, R.U.; Kabir, R. A stacked bidirectional lstm model for classifying source codes built in mpls. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases: International Workshops of ECML PKDD 2021, Virtual Event, 13–17 September 2021; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, D. Natural language processing for enhancing teaching and learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- ChatGPT. Available online: https://chatgpt.com, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gemini. Available online: https://gemini.google.com/app, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Claude. Available online: https://claude.ai/, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- LLAMA. Available online: https://www.llama.com, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Tian, S.; Jin, Q.; Yeganova, L.; Lai, P.-T.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Kim, W.; Comeau, D.C.; et al. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Xu, M.; Patros, P.; Wu, H.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, K.; Fuller, S.; Singh, M.; Arora, P.; Parlikad, A.K.; et al. Transformative effects of ChatGPT on modern education: Emerging Era of AI Chatbots. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 4, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, D.; Sun, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Kim, J.H. Analyzing behavioral intentions toward Generative Artificial Intelligence: The case of ChatGPT. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, L.P.; Busby, E.C.; Fulda, N.; Gubler, J.R.; Rytting, C.; Wingate, D. Out of one, many: Using language models to simulate human samples. Political Anal. 2023, 31, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. R.; Rice, C. The advantages and limitations of using ChatGPT to enhance technological research. Technol. Soc. 2024, 76, 102426.

- Hämäläinen, P.; Tavast, M.; Kunnari, A. Evaluating Large Language Models in Generating Synthetic Hci Research Data: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg Germany, 23–28 April 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Wang, Tianlong Xu, Hang Li, Chaoli Zhang, Joleen Liang, Jiliang Tang, Philip S. Yu, Qingsong Wen, Large Language Models for Education: A Survey and Outlook, https://arxiv.org/html/2403.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Available online: https://inspirasifoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/John-Hattie-Visible-Learning_-A-synthesis-of-over-800-meta-analyses-relating-to-achievement-2008.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani L, Seth KP. Factors influencing students' satisfaction with continuous use of learning management systems during the COVID-19 pandemic: An empirical study. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26(6):6787-6805. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33841029/. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Learning management system, EN. WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_management_system (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Studies on the impact of cellphones on academics, CACSD.ORG. Available online: https://www.cacsd.org/article/1698443 Available online: (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Lepp, A. , Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2015). The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of U.S. college students. Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 31, 343–350. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563213003993. [CrossRef]

- Junco, R. (2012). In-class multitasking and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 28, no. 6, pag. 2236–2243. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563212001926ISSN 0747-5632. [CrossRef]

- Clinton, V. Reading from paper compared to screens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Res. Read. 2019, 42, 288–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrachi, D.; Salaz, A.M.; Kurbanoglu, S.; Boustany, J. Academic reading format preferences and behaviors among university students worldwide: A comparative survey analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrachi, D.; Salaz, A.M.; Kurbanoglu, S.; Boustany, J. The Academic Reading Format International Study (ARFIS): Final results of a comparative survey analysis of 21,265 students in 33 countries. Ref. Serv. Rev. 2021, 49, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrachi, D.; Salaz, A.M. Beyond the surveys: Qualitative analysis from the academic reading format international study (ARFIS). Coll. Res. Libr. 2020, 81, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsen, S.; Wanatowski, D.; Zhao, D. Behavior of Science and Engineering Students to Digital Reading: Educational Disruption and Beyond. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quizlet's State of AI in Education Survey Reveals Higher Education is Leading AI Adoption. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/quizlets-state-of-ai-in-education-survey-reveals-higher-education-is-leading-ai-adoption-302195348.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- N. Sandu, E. N. Sandu, E. Gide, "Adoption of AI-Chatbots to Enhance Student Learning Experience in Higher Education in India," 2019 18th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Magdeburg, Germany, 2019. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. and M.A. Barlow, What are Conversational Bots?: An Introduction to and Overview of AI-driven Chatbots. 2016: O'Reilly Media.

- Shevat, A. , Designing bots: Creating conversational experiences. 2017: " O'Reilly Media, Inc.".

- Davenport, T.H. and P. Michelman, The AI advantage. 2018.

- M. Verleger and J. Pembridge, “A Pilot Study Integrating an AI-driven Chatbot in an Introductory Programming Course,” in Proceedings - Frontiers in Education Conference, FIE, 2019, vol. 2018-Octob.

- D. Duncker, “Chatting with chatbots: Sign making in text-based human-computer interaction,” Sign Syst. Stud., vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 79–100, Jun. 2020.

- P. Smutny and P. Schreiberova, “Chatbots for learning: A review of educational chatbots for the Facebook Messenger,” Comput. Educ., vol. 151, p. 103862, Jul. 2020.

- A. Miklosik, N. Evans, and A. M. A. Qureshi, “The Use of Chatbots in Digital Business Transformation: A Systematic Literature Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 106530–106539, 2021.

- S. Singh and H. K. Thakur, “Survey of Various AI Chatbots Based on Technology Used,” in ICRITO 2020 - IEEE 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions), 2020, pp. 1074–1079.

- Okonkwo, C.W., & Ade-Ibijola, A. (2021). Python-Bot: A Chatbot for Teaching Python Programming. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12(2), 202–208.

- Dan, Y., Lei, Z., Gu, Y., Li, Y., Yin, J., Lin, J., Ye, L., Tie, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, A., Zhou, Z., Chen, Q., Zhou, J., & He, L. (2023). EduChat: A Large-Scale Language Model-based Chatbot System for Intelligent Education. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.02773, Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.02773?utm_source=chatgpt.com, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- GPTeens, 2024, Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GPTeens?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Li, Y., Qu, S., Shen, J., Min, S., & Yu, Z., Curriculum-Driven EduBot: A Framework for Developing Language Learning Chatbots Through Synthesizing Conversational Data, 2023 arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16804. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.16804?utm_source=chatgpt.com, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- BlazeSQL, Available online: https://www.blazesql.com/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- 66. OpenSQL - From Questions to SQL. Available online: https://opensql.ai/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- 67. Chat with SQL Databases using Chat with SQL Databases using AI - Available online: https://www.askyourdatabase.com/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Mahapatra, S., Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students' academic writing skills: A mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learning Environments, 2024, Available online: https://slejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40561-024-00295-9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00129-1, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Pros And Cons Of Traditional Teaching: A Detailed Guide, accessed February 2, 2025, Available online: https://www.billabonghighschool.com/blogs/pros-and-cons-of-traditional-teaching-a-detailed-guide/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Google Cloud Run, Available online: https://cloud.google.com/run#features (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Yunfan Gao, Yun Xiong, Xinyu Gao, Kangxiang Jia, Jinliu Pan, Yuxi Bi, Yi Dai, Jiawei Sun, Meng Wang, Haofen Wang, Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey, 2024, 2312.10997, https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.10997.

- Lianmin Z., Wei-Lin C., Ying S., Siyuan Z., Zhanghao W., Yonghao Z., Zi L., Zhuohan Li, Dacheng Li, Eric P. Xing, Hao Z., Joseph E. Gonzalez, Ion Stoica}, Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena, 2023, eprint 2306.05685, Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.05685, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Liang, P., Bommasani, R., Lee, T., et al. (2023). Holistic Evaluation of Language Models. arXiv:2211.09110. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.09110, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gemini Team, “Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805, 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11805, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gemini Team, “Gemini 1.5: Unlocking Multimodal Understanding Across Millions of Tokens of Context,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.05530, 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.05530, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- S. N. Akter, Z. Yu, A. Muhamed, T. Ou, A. Bäuerle, et al., “An In-depth Look at Gemini’s Language Abilities,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11444, 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11444, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Google Cloud Vertex AI. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., et al. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv:2203.02155. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Bai, Y., et al. (2023). Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. arXiv:2303.08774. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Microsoft Search AI. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/search/search-overview, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Yang, Yixin, Li, Zheng, Dong, Qingxiu, Xia, Heming, Sui, Zhifang, Can Large Multimodal Models Uncover Deep Semantics Behind Images? Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.11281, 2024, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- RAG Evaluation - Available online: https://docs.confident-ai.com/guides/guides-rag-evaluation (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Yian Zhang, Yifan Mai, Josselin Somerville Roberts, Rishi Bommasani, Yann Dubois, Percy Liang, HELM Instruct: A Multidimensional Instruction Following Evaluation Framework with Absolute Ratings, 2024, Available online: https://crfm.stanford.edu/2024/02/18/helm-instruct.html, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Agustín Garagorry Guerra, Evaluating Students' Open-ended Written Responses with LLMs: Using the RAG Framework for GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Claude-3, and Mistral-Large, 2024, 2405.05444, Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.05444 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Best Practices for LLM Evaluation of RAG Applications - A Case Study on the Databricks Documentation Bot, Available online: https://www.databricks.com/blog/LLM-auto-eval-best-practices-RAG (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Matthew Renze, Erhan Guven, The Effect of Sampling Temperature on Problem Solving in Large Language Models, 2024, Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2402.05201v1, (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych, Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks, 2019, Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.10084, (accessed on 26 February 2025).