1. Introduction

As Autonomous Unmanned Vehicles (AUVs) have become an essential technological advancement for marine activities, particularly in oceanographic research, the exploration of underwater shipwrecks, and the monitoring of submerged historical sites. As the demand for more efficient and flexible methods to monitor fisheries grows, AUVs offer a promising solution. Their ability to operate autonomously in challenging underwater environments offers significant advantages, particularly in industries like oceanography, marine archaeology, and aquaculture. AUVs provide a cost-effective alternative to traditional methods, eliminating the need for human presence on fish farms.

Furthermore, AUVs can autonomously detect potential issues with fish farm nets, such as net damage, overgrowth, and transmit real-time data to operators, thereby minimizing the need for human intervention. Weather conditions such as low temperatures, heavy rainfall, or cloud cover can limit human capabilities in marine environments, making AUVs a valuable asset in overcoming these challenges. These vehicles can operate under a range of adverse conditions, maintaining operational efficiency while ensuring the continuous monitoring of aquaculture sites. However, the successful deployment of AUVs requires reliable communication between the vehicle and an external server or operator, enabling remote control, as well as the processing of images and video data.

This paper presents the case study of the Kalypso AUV, developed specifically for the inspection of fish farm nets, and outlines the key design features, challenges encountered, and solutions implemented during its construction. During the development of the underwater robot discussed in this paper, several challenges emerged that required careful examination and problem-solving. The second section of this paper reviews relevant work involving various underwater robots. The third section outlines the challenges encountered during the development process and presents the solutions implemented. The paper concludes in the fourth section with a summary of the findings and suggestions for future work.

2. Related Work

The development of Kalypso [

1] marks a significant advancement in the application of autonomous underwater robotic vehicles in the fish farming industry. In recent years, several efforts have been made to design and deploy autonomous systems for monitoring and maintaining fish farm infrastructure, with a focus on improving efficiency, reducing operational costs, and enhancing sustainability. Kalypso's ability to autonomously distinguish between clean and damaged areas of fish farm nets plays a critical role in early detection of problems, thereby preventing net breakage. This section, examines relevant work in AUV development, including useful insights into design approaches, sensor integration, and control systems and further highlights the capabilities and advancements in AUV technology.

A number of similar underwater robots have been developed to perform inspection and monitoring tasks in aquaculture, leveraging advancements in sensor technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning algorithms. One such example is the hybrid autonomous underwater glider presented by Siregar et al. [

2], which features a torpedo-shaped design, approximately 2.3 meters in length and 24cm in diameter. This vehicle is engineered for a range of underwater applications, including search, mapping, monitoring, surveillance, and maintenance tasks. A relevant contribution is the work of Becker et al. [

3], who introduced a modular packaging platform for AUV sensor systems. This platform is designed to withstand the harsh conditions of marine environments, providing a robust and flexible solution for integrating a variety of sensors, such as those used for environmental monitoring, imaging, and navigation. Another notable contribution is the work by Fuad et al. [

4], which presents an AUV named "Aqualung" designed for underwater exploration and monitoring. Aqualung incorporates an innovative pressure sensor system that converts air pressure to underwater pressure, enabling more accurate depth measurements. This is particularly useful for ensuring the vehicle’s stable navigation in varying depths.

A paper by Chen et al. [

5] introduces an autonomous quadrotor vehicle capable of both aerial flight and underwater locomotion. This hybrid vehicle is designed for versatility, combining the advantages of aerial mobility with underwater capabilities. Another relevant contribution is the work of McCarter et al. [

6], which presents the Virginia Tech 690 AUV, designed for bathymetric surveys, capable of operating at depths of up to 500 meters while displacing less than 45 kg. The Virginia Tech 690 AUV emphasizes compactness and maneuverability, making it suitable for surveying underwater terrains, mapping seafloor topography, and conducting environmental assessments in deep-water areas. Another contribution is the development of Pirajuba, a low-cost AUV introduced by De Barros et al. [

7]. The Pirajuba AUV emphasizes affordability without compromising on performance, making it an attractive option for a variety of underwater applications. Key to its design are innovative hardware and software control architectures, which enable reliable operation while keeping costs low. The paper by Cruz et al. [

8] focuses on the development of a lightweight docking station for a hovering AUV, specifically designed to extend the mission duration of the Mares AUV. The Mares AUV is a hovering vehicle used in a variety of underwater applications, and the docking station is a key innovation that helps extend its operational time in the field.

Another contribution by Li and Wang [

9], presents an AUV specifically designed for water pollution monitoring. This AUV is equipped with a power supply system that supports mission durations of 10 to 15 hours, allowing it to cover routine patrol lines of up to 26 kilometers. A notable example is the work by Meng and Qingyu [

10], which presents an AUV designed for operation in a lake environment. This vehicle incorporates several passive safety systems, including a dual power supply system, a backup battery, and a rescue balloon designed to help the AUV return to the surface in the event of a malfunction. Another significant contribution to AUV technology is the work presented by Simplicio et al. [

11], which focuses on the UFRJ Nautilus AUV and the application of multisensor data fusion techniques. This AUV incorporates an echo localization algorithm based on traditional beamforming, which is optimized to be both fast and power-efficient. A notable work is presented by Abreu et al. [

12], who developed an automatic interface for AUV mission planning and supervision. This integrated application is specifically designed to automate the process of sea outfall discharges data acquisition using an AUV.

A Paper by Aras et al. [

13] describes the design and development of the AUV-FKEUTeM, an autonomous underwater vehicle created as a test bed platform for research in underwater technologies. The AUV is designed to facilitate a wide range of underwater experiments, providing a versatile platform for testing various sensors, propulsion systems, and control algorithms. The Paper by Manzanilla et al. [

14], outlines the development, modeling, and control of an AUV known as AUV-UMI. The vehicle is designed as a modular mini submarine, also referred to as a rover-type AUV, which offers flexibility in its configuration and application. The paper by Faidhon et al. [

15], describes the design of UNEXAR, a mini AUV, and its incorporation of artificial intelligence for improved autonomous operations. The paper outlines the process of designing and measuring the mechanical structure, electronics, and AI-based control systems of the AUV.

Overall, Kalypso [

1] represents a significant step forward in the development of autonomous AUVs for the aquaculture sector. Its combination of autonomous navigation, advanced sensor integration, and machine learning for damage detection holds the potential to improve both the efficiency and sustainability of fish farming operations. Additionally, the integration of ultrasonic sensors and environmental monitoring capabilities in Kalypso aligns with advancements in sensor fusion techniques, where multiple sensor inputs are combined to improve the accuracy and robustness of underwater robotic systems. The ability to monitor environmental parameters such as water temperature, depth, and leaks further enhances Kalypso’s operational effectiveness, ensuring that it can function reliably in a variety of underwater conditions.

3. Key Challenges and Solutions

This section outlines the key issues encountered in the design and implementation of Kalypso, along with the corresponding solutions that were developed to address them. One of the key challenges in developing Kalypso was ensuring its electronics remained waterproof to prevent water ingress and system failure. This was addressed through specialized waterproof connectors, sealed enclosures, and pressure relief valves, allowing the AUV to operate reliably in underwater environments. Additionally, a central relay system was implemented to facilitate efficient power control, overcoming initial limitations of manual activation and low-rated switches.

3.1. Waterproofing

One of the most critical challenges encountered during the development of Kalypso was ensuring the proper sealing and insulation of its internal electronics to prevent water ingress. Since the AUV is designed to operate in aquaculture environments, any water penetration could compromise the functionality of the sensors, motors, and control systems, leading to potential mission failure or damage to the robot’s internal components.

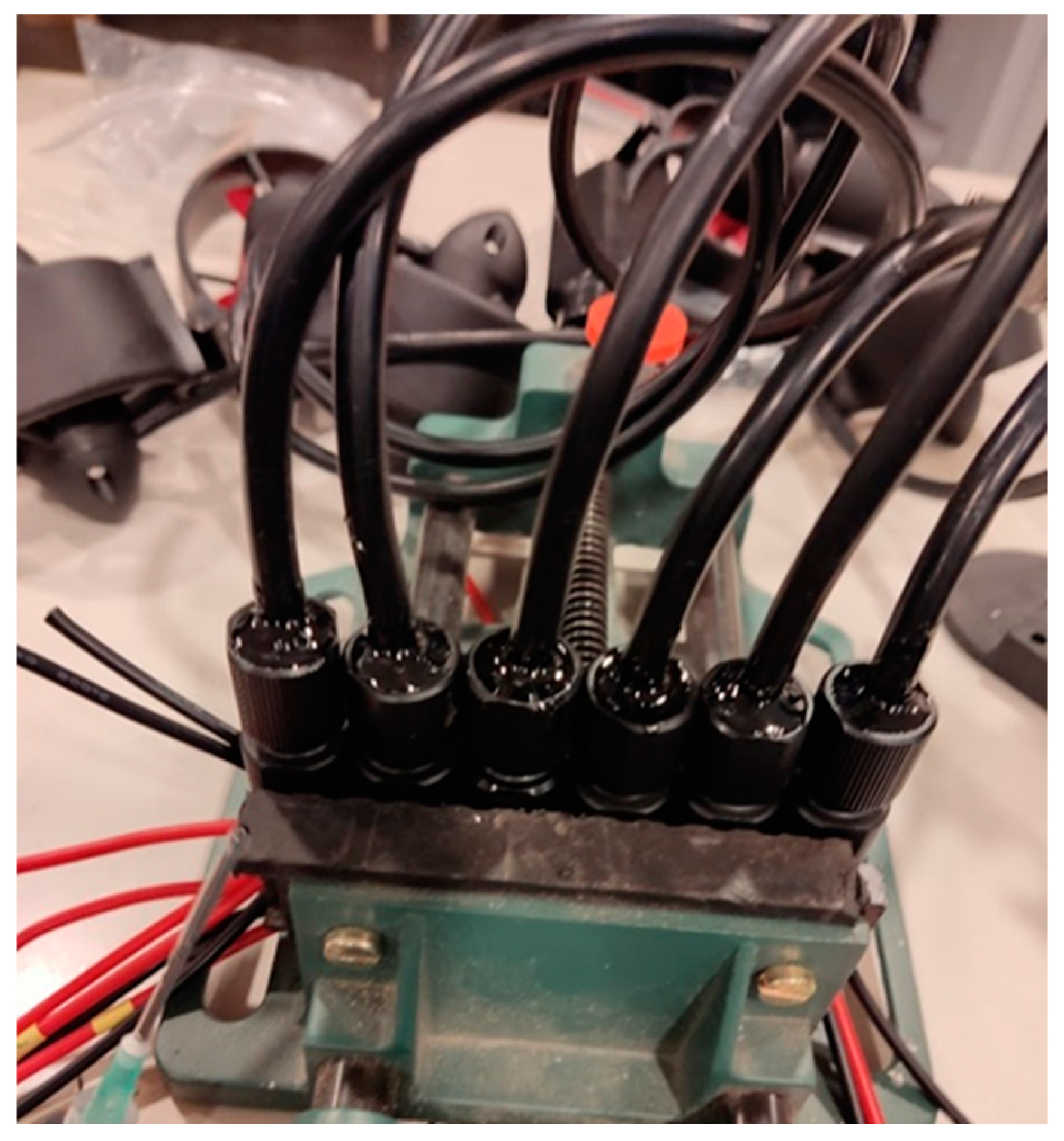

To address this issue, special attention was given to the waterproofing of the AUV’s electrical connections. The cables connected to the motors, sensors, and other critical components were fitted with waterproof plugs and connectors. These connectors were specifically chosen to meet the complex requirements of underwater operations, providing an airtight seal that prevents water from entering sensitive areas.

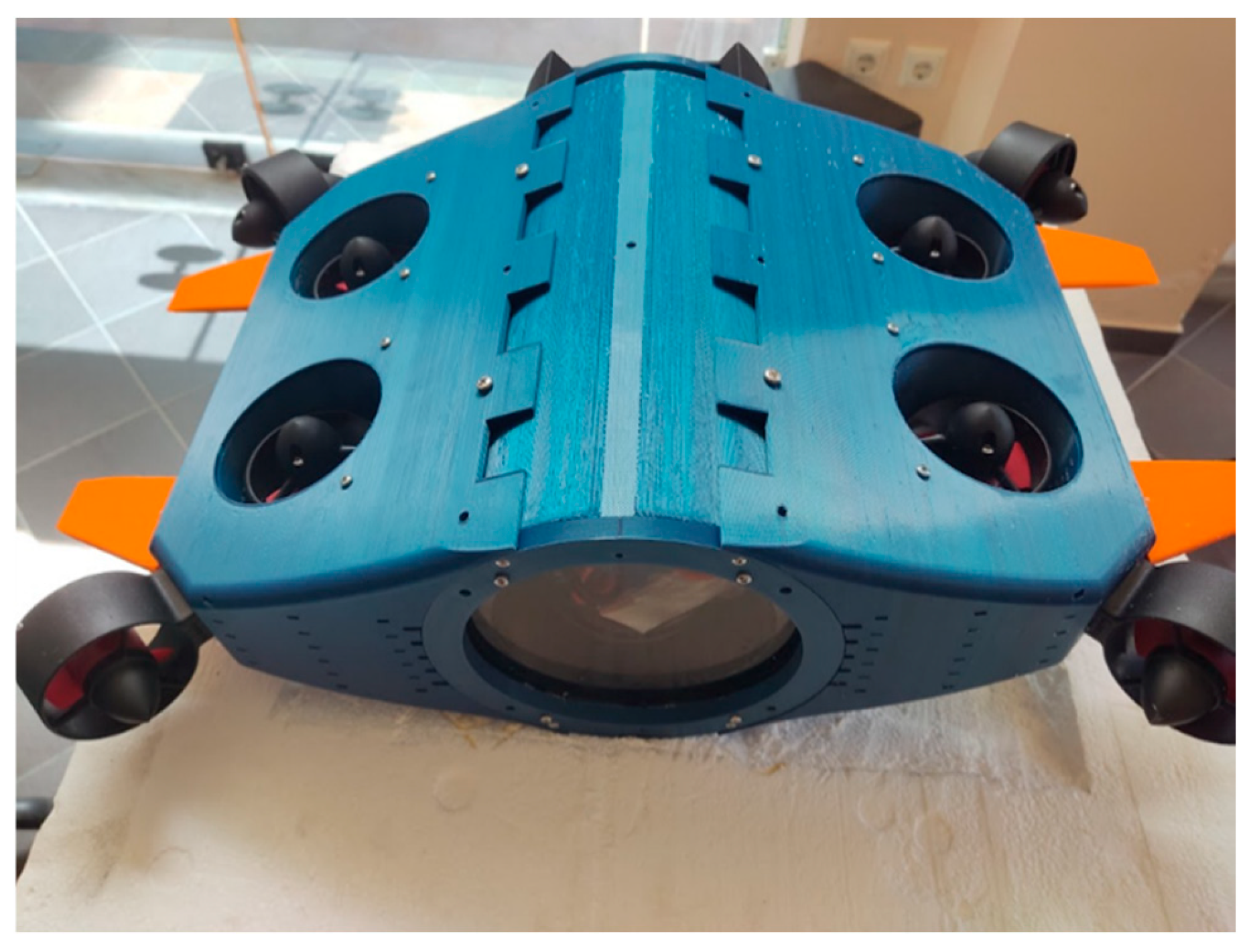

In addition to the waterproof plugs, the design incorporated sealed enclosures around the electronic components. The enclosures were constructed using durable materials resistant to corrosion and capable of withstanding the pressure of deep-water environments, as presented in the below

Figure 2. This step was essential to maintain the integrity of its electronic systems during extended underwater missions.

Another significant aspect of the waterproofing solution was the implementation of pressure relief valves in certain areas of the robot. These valves help to equalize the pressure inside the sealed compartments, preventing the buildup of internal pressure that could potentially damage the AUV's delicate electronics. This approach, in combination with the waterproof seals, ensures that Kalypso can operate reliably at various depths, from shallow water environments to deeper fish farm nets.

Overall, the waterproofing of Kalypso’s electronic components was one of the key challenges during its development. By using specialized waterproof connectors, sealed enclosures, and pressure relief valves, the team was able to successfully address these issues, ensuring that the AUV could operate autonomously in challenging underwater conditions without compromising its performance or reliability.

3.2. Power Relay

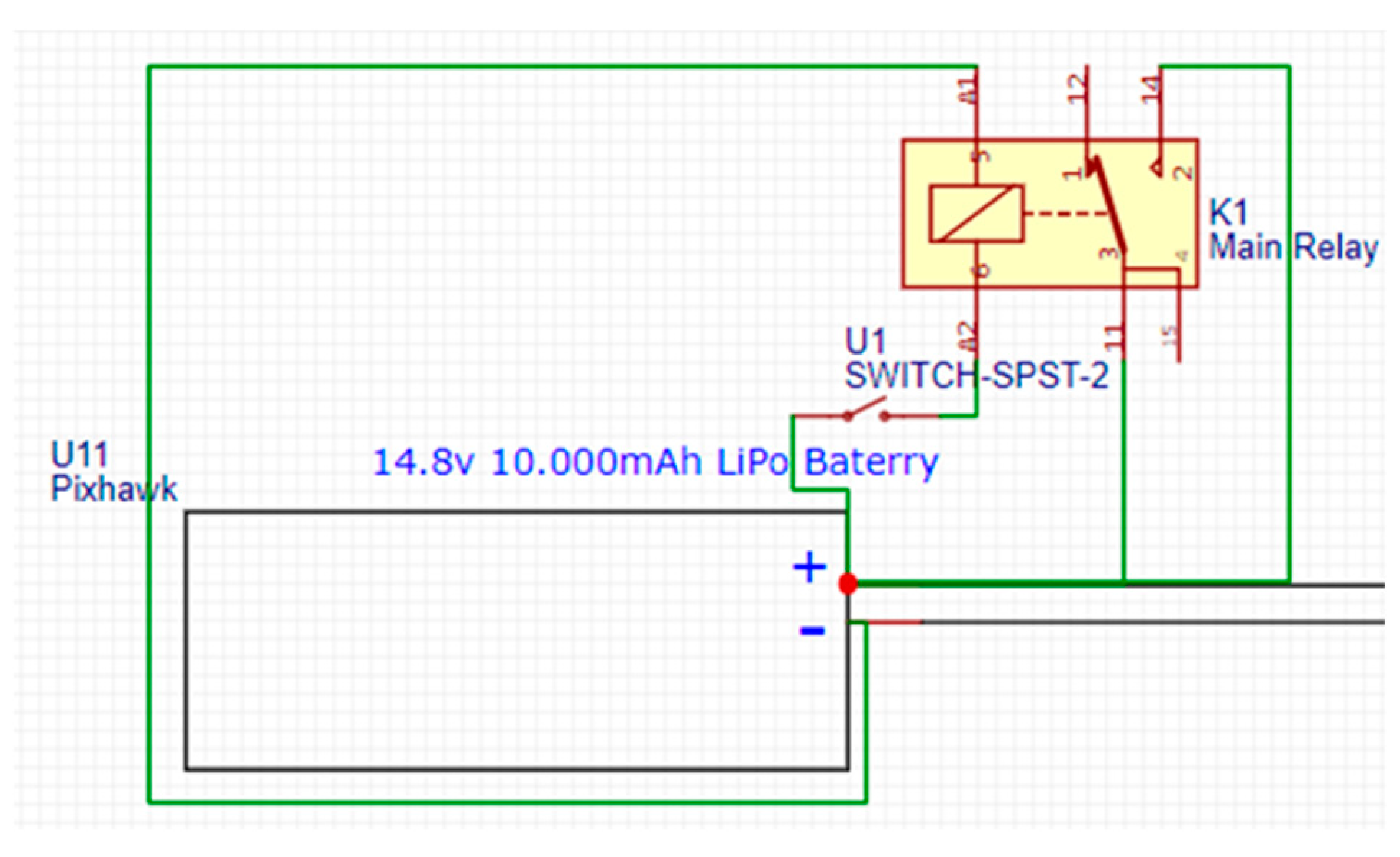

Another significant challenge encountered during the testing of Kalypso was the central activation and deactivation of the AUV without the need for direct intervention inside the robot. Initially, the activation process was achieved by manually connecting the positive terminal of the batteries to the main circuit, while deactivation was performed by disconnecting the battery terminal. However, this manual process proved to be inefficient and impractical for repeated operations, especially in the context of autonomous underwater missions.

To address this issue, a power switch was integrated into the design, mounted on the back of the robot, alongside connectors for the motors and sensors. This switch allowed for more convenient activation and deactivation from the exterior, eliminating the need for internal intervention. However, a limitation soon became apparent: the switch was rated for a maximum current of 5A, which was insufficient to handle the high current required for the robot's motors and electronics.

To resolve this additional limitation, the solution involved the introduction of a central relay system. The relay was connected to the power switch and designed to handle higher currents than the switch itself could manage. When the power switch was activated, it triggered the relay, which in turn connected the positive terminal of the batteries to the rest of the robot's circuit. This allowed for efficient power control without exceeding the current limitations of the initial switch. The relay system was integrated with appropriate wiring, ensuring that it could manage the required power loads while maintaining safe and reliable operation. The schematic of the power relay system, which illustrates the connection between the power switch, relay, and battery terminals, is shown

Figure 4.

Overall, the introduction of a central relay system allowed Kalypso to overcome the limitations of the initial power switch, enabling more reliable and efficient power management. This modification streamlined the process of activating and deactivating the AUV while maintaining the safety and integrity of its electrical components.

3.3. Balance Battery Charge

Another issue that emerged during the development of Kalypso was how to charge the AUV’s batteries efficiently without needing to open the robot’s internal compartments. This challenge was particularly important as it would allow the fish farm staff to perform routine charging without technical expertise or manual intervention. The solution required a method to enable fast and convenient charging while maintaining battery health and ensuring the correct charging procedure.

The key requirement was to facilitate balanced charging, which is critical for maintaining the longevity and efficiency of the lithium-ion batteries used in Kalypso. To achieve this, an internal conversion system was devised, which allowed the robot to connect to an external charger without requiring manual access to the internal components.

Internally, when the robot is powered off, the positive and negative terminals of the batteries are connected to a 4-pin connector. This allows for simple power connection when the robot is in operation. However, for balanced charging, a more complex setup was necessary. Out of the 5 pins required for balanced charging, two pins are used for the positive and negative connections, which are already supplied by the battery terminals. Therefore, there is no need for additional internal wiring to handle these connections during charging. The remaining 3 pins from the 5-pin connection are used to connect to a multi-pin charging plug, which is an 8-pin connector positioned externally on the robot. This connector facilitates a connection to the battery charger. During charging, the 8-pin plug is connected to the charger, with the 3 remaining pins used for the balanced charging function, ensuring that each cell within the battery pack is charged uniformly.

By using this setup, Kalypso’s batteries can be charged quickly and efficiently without the need to open the robot’s casing. This method also ensures that the battery pack is properly balanced during charging, which helps to maximize the life and performance of the batteries over time

Overall, the addition of an external charging port with a 4-pin internal connector and an 8-pin balanced charging interface resolved the issue of battery charging. It allowed the fish farm staff to easily connect Kalypso to a charger without needing to disassemble or open the robot, thus streamlining maintenance and ensuring optimal battery performance.

3.4. Space Constraints in the Electronics Compartment

A significant issue that arose during the construction of Kalypso was the lack of space within the electronics compartment as additional functions and components were integrated into the system. As the design evolved, new features such as the central activation relay and relay for LED lighting were added, which required additional space for wiring and components. The increasing complexity of the AUV’s electronics placed constraints on the available room inside the waterproof compartment.

To address this problem, the design team focused on optimizing the use of available space by reducing the cross-sectional area of the cables where possible. By using thinner, more compact cables that still met the necessary power and data transmission requirements, the overall volume of the electronics compartment was maximized. This allowed for the integration of all essential components while maintaining the integrity of the design and ensuring proper operation.

Additionally, careful routing of cables was employed to avoid any interference between different components, especially in tight spaces. This approach required meticulous planning to ensure that there was enough clearance for all components and that the wiring did not obstruct airflow or cause overheating.

In some cases, modular components were used to reduce the complexity of the wiring. For example, certain sensors and relays were designed as integrated modules, which minimized the need for multiple individual connections and helped to free up valuable space inside the compartment.

Overall, the combination of optimized cable routing, thinner cables, and modular components allowed the team to effectively address the challenge of limited space in the electronics section. These design adjustments ensured that Kalypso’s complex systems could be integrated within the available space while maintaining functionality, reliability, and ease of maintenance.

4. Experimental Results of the Kalypso AUV

The Kalypso AUV was developed and designed for the fisheries of Kefalonia, specialising in tasks such as object retrieval, dead fish removal, and net repair. Kalypso’s main processing board is open-source, ensuring interoperability with other components and its hardware includes a Raspberry Pi and a PC running Ubuntu with I2C communication protocol. The vehicle's design incorporates six degrees of freedom, enabling movement in all directions and orientations (forward/backward, left/right, up/down). Kalypso’s motors are enclosed within 3D-printed protective components, ensuring operational safety. The operational runtime of Kalypso is approximately 2.5 hours and the total cost of the vehicle is around €4,500.

Kalypso underwent testing for rotational maneuvers, including roll, pitch, and yaw, and achieved a maximum depth of 16.5 meters. During testing, Kalypso effectively performed complete clockwise and counterclockwise rotations around each axis within a reasonable time, showcasing its ability to execute precise rotational maneuvers. The vehicle is equipped with the appropriate connectors that enable the swapping of different cables without the need to open the waterproof enclosure. Kalypso was tested as a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), where an operator controlled its movements (stabilisation mode for maintaining direction and depth-hold mode) to inspect the nets using semi-autonomous functions. Furthermore, it was evaluated as an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), performing independent missions within the net to enclosures to record video.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the development of Kalypso highlights the significant potential of autonomous robotic technology in addressing critical challenges within the aquaculture industry. Through extensive testing, refinement, and experimentation, Kalypso has demonstrated its ability to perform a variety of tasks, particularly in the inspection and monitoring of fish farm nets, with increasing stability and reliability.

One of the standout features of Kalypso is its modular and customizable design, which leverages 3D printing and simple materials. This makes the AUV more accessible and cost-effective, allowing for easier assembly and potential for widespread adoption. As technology continues to evolve, it is expected that Kalypso AUVs will become even more affordable, versatile, and easier to maintain, with simpler, more efficient components.

The removable charging plug is a key design advantage of Kalypso compared to other AUVs in this category. It simplifies the process of recharging and enhances the robot’s usability, particularly for farm workers who require an easy-to-use solution. The inclusion of a bottom camera further strengthens Kalypso’s capabilities, allowing for high-quality imaging of the fish farm nets without the need for additional movements, thereby improving efficiency and reducing the complexity of operations.

There are several areas for future development, that could improve the overall capabilities, reliability, and versatility of Kalypso, making it an even more valuable tool for the aquaculture industry in terms of both productivity and sustainability. These include enhancing long-range communication capabilities, which would allow for better data transfer over longer distances, and improving the robotic navigation systems to allow for more precise and autonomous movement in complex underwater environments. With continuous improvements and refinements, Kalypso could become an indispensable tool for the aquaculture industry, providing a cost-effective, reliable, and efficient solution for monitoring and maintaining fish farm infrastructure.

References

- Vasileiou, M.; Manos, N.; Vasilopoulos, N.; Douma, A.; Kavallieratou, E. Kalypso Autonomous Underwater Vehicle: A 3D-Printed Underwater Vehicle for Inspection at Fisheries. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2024, 16, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, S.; Trilaksono, B.R.; Hidayat, E.M.I.; Kartidjo, M.; Habibullah, N.; Zulkarnain, M.F.; Setiawan, H.N. Design and Construction of Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Glider for Underwater Research. Robotics 2023, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.F.; Voitel, M.; Schütze, D.; Nguyen, T.D.; Spanier, M.; Hölck, O.; Schneider-Ramelow, M. Development of robust sensor packages for autonomous underwater vehicles. IMAPSource Proceedings 2023, 2022, 000470–000475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, A.M.; Islam, M.N.; Raihan, K.R.; Talha, M.; Tasin, M.M.H.; Ahmed, I.; Farrok, O. (2022, September). Implementation of the AQUALUNG: A new form of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. In 2022 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Symposium (AUV) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Chen, Y.H.; Shen, S.C.; Wu, Y.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Chen, Y.J. Design and Testing of Real-Time Sensing System Used in Predicting the Leakage of Subsea Pipeline. Sensors 2022, 22, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter, B.; Portner, S.; Neu, W. L. , Stilwell, D. J., Malley, D., & Mims, J. (2014, October). Design elements of a small AUV for bathymetric surveys. In 2014 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- De Barros, E.A.; Freire, L.O.; Dantas, J.L. Development of the Pirajuba AUV. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2010, 43, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N.A.; Matos, A.C.; Almeida, R.M.; Ferreira, B.M. (2017, February). A lightweight docking station for a hovering AUV. In 2017 IEEE Underwater Technology (UT) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Li, M.; Wang, M. (2010, July). AUV power supply system control and remote monitoring. In Proceedings of the 29th Chinese Control Conference (pp. 5037-5041). IEEE.

- Meng, L.; Qingyu, Y. (2010, May). Enhanced safety control and self-rescue system applied in AUV. In 2010 International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (Vol. 2, pp. 212-215). IEEE.

- Simplicio, S.; Ferreira, H.J.D.S.; Villela, G.; Costa, F.B.; Pavani, V.; Rodrigues, L.; de Farias, C.M. (2020, July). Development of the UFRJ Nautilus' AUV: A Multisensor Data Fusion case study. In 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION) (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

- Abreu, N.; Matos, A.; Ramos, P.; Cruz, N. (2010, September). Automatic interface for AUV mission planning and supervision. In OCEANS 2010 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Aras, M.S.M.; Kasdirin, H.A.; Jamaluddin, M.H.; Basar, M.F.; Elektrik, U. (2009, June). Design and development of an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV-FKEUTeM). In Proceedings of MUCEET2009 Malaysian Technical Universities Conference on Engineering and Technology, MUCEET2009, MS Garden, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysi.

- Manzanilla, A.; Garcia, M.; Lozano, R.; Salazar, S. Design and control of an autonomous underwater vehicle (auv-umi). Marine Robotics and Applications 2018, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Faidhon, N.; Agung, N.J.; Unang, S. (2015, August). UNEXAR—Mini AUV design & measurement UNEXAR—Desain dan Pengukuran Mini-AUV. In 2015 International Conference on Control, Electronics, Renewable Energy and Communications (ICCEREC) (pp. 203-207). IEEE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).