Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Risk Factors

2.1. Smoking

2.2. Pulmonary Function

2.3. Socio-Economic Factors

3. Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

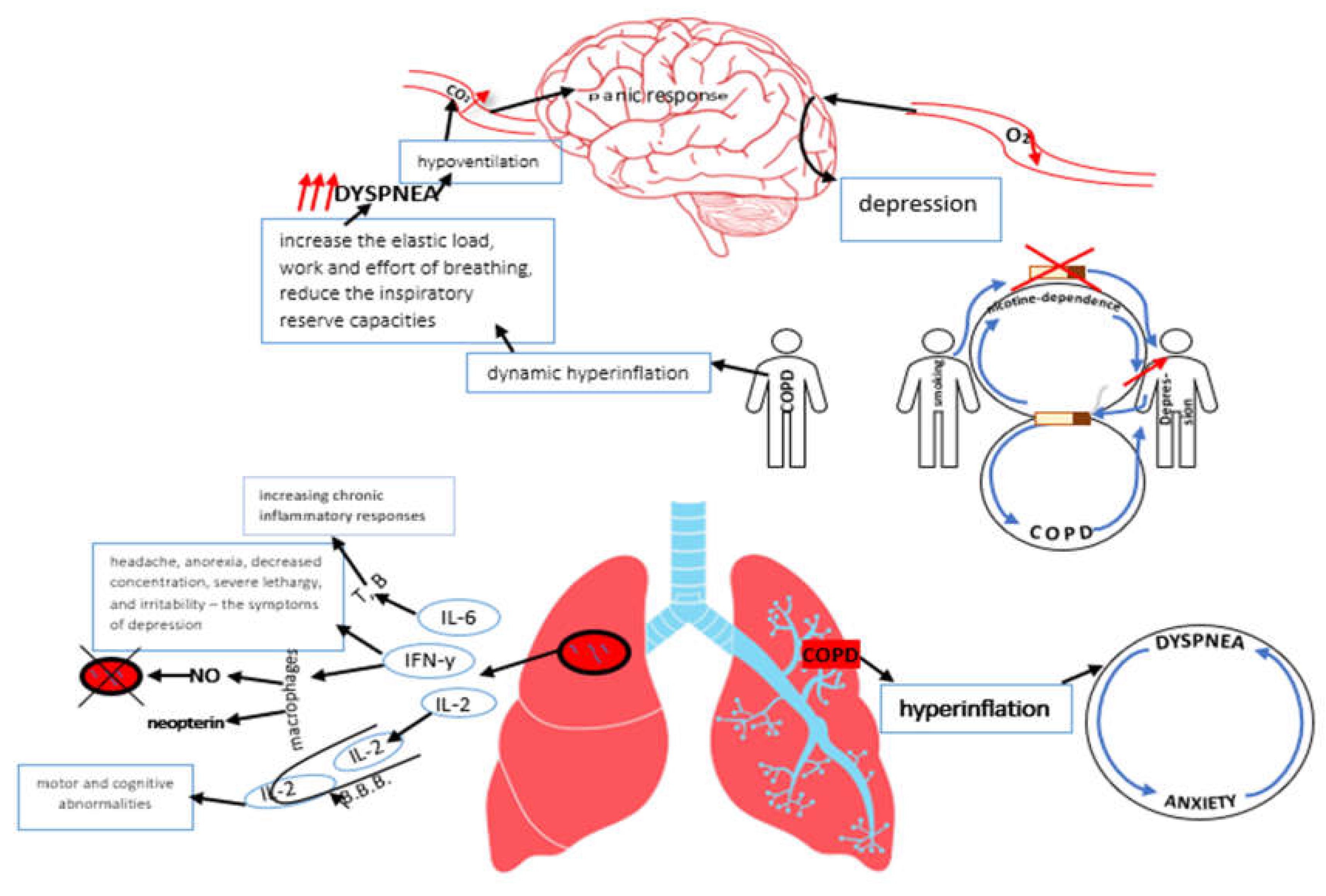

3.1. The Anxiogenic Effects of Hyperventilation. Misinterpretation of Respiratory Symptoms

3.2. Neurobiological Sensitivity to CO2, Lactate, and Other Suffocation Signals in COPD and Depression

3.3. The Role of Nicotine Dependence and Smoking in COPD and Depression

3.4. The Impact of Hypoxia on COPD and Depression

3.5. The Role of Inflammation in COPD and Depression

3.6. Oxidative Stress

4. Depression and COPD Exacerbations

5. Depression and COPD in the Elderly

6. COPD and Depression: Clinical Differences Between Men and Women

7. Screening for Depression in COPD

8. Scales/Scores for Assessment of Depression in COPD

| BDI | GDS | CES-D | HADS | |

| Number of questions/time for evaluation | -21 items -2 past weeks |

-30 items (long version) -15 items (short version) -current/past week |

-20 items [112] (and other versions) -1 past week |

-14 items (7-anxiety-related, 7-depression-related) |

| Are evaluated | patients with somatic, affective, cognitive and vegetative symptoms | normal community-dwelling elderly and elders hospitalized for depression | patients with positive/negative effect, somatic problems, evaluating their activity level | psychiatric and medical patients, including cancer, traumatic brain injury, cardiac, stroke, intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc., ages 16–65 years |

| Scale |

*a 4-point scale: 0-means not at all 3-extreme form of each symptom |

*a scale – «yes or no» |

*a 4-point scale: 0-rarely(<1/day) 1-some/little of the time (1-2 days) 2-occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3-4 days) 3-most or all of the time (5-7 days) |

*a 4 point Likert scale, ranging from 0-3 |

| Score interpretation | *minimal range= 0-13 *mild depression= 14-19 *moderate depression= 20-28 *severe depression= 29-63 |

*long form: 0-9-normal, 10-19-mild depression, 20-30-severe depression *short form: >5-suggestive for depression and >10-highly likely depression |

Easily hand scored. The items should be summed to obtain a total score. | *0-7-normal *8-10-mild *11-15-moderate *>=16-severe |

| Time to administer/complete | *self-administration= 5-10 min. *oral administration= 15 min. |

*long version – 5-10 min. *short version – 2-5 min. |

10 minutes | <=5 min. (1-2 min.) |

| Response format | 0-3 rating scale | «yes» or «no» | 4 point Likert scale | *0-3 rating scale |

| Sensitivity to change | *5-point difference=minimally important clinical difference *10-19points =moderate difference *>20 points =large difference [113] |

*the short form shows the sensitivity of 81.3% *the long form shows the sensitivity of 77.4% |

*ranges of 13-21 have been provided for detecting of 80-90% reliable change. | *sensitivity = 56-100 % |

| Restrictions/ limitations | Overlapping symptoms between other medical conditions and depression, cost and reading level | It is valid in younger samples. In needs caution when used with cognitively impaired individuals and severely cognitively impaired individuals | Response format can be difficult in original 20-item instrument, and is a contributing reason for the development of shorter versions | It is better to compare HADS to other measures of depression |

| Ease to use | time to complete – 5-15 min. | self-administered questionnaire | Time to interpret <10 min. Easily self-administered/ administered by interviewer. | self-administered questionnaire |

9. Impact of COPD Medication on Depression and Vice Versa

10. Future Perspective

11. Conclusions

References

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, P.; Celli, B.R.; Agustí, A.; Jensen, G.B.; Divo, M.; Faner, R.; Guerra, S.; Marott, J.L.; Martinez, F.D.; Martinez-Camblor, P.; et al. Lung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease- (accessed on day month year).

- Corlateanu, A.; Covantev, S.; Mathioudakis, A.G.; Botnaru, V.; Siafakas, N. Prevalence and burden of comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respir. Investig. 2016, 54, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareifopoulos, N.; Bellou, A.; Spiropoulou, A.; Spiropoulos, K. Prevalence, Contribution to Disease Burden and Management of Comorbid Depression and Anxiety in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Narrative Review. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2019, 16, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, Smith S. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest [Internet]. 2013 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jan 28];144(3):766–77. Available from: http://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012369213605929/fulltext.

- Pumar MI, Gray CR, Walsh JR, Yang IA, Rolls TA, Ward DL. Anxiety and depression—Important psychological comorbidities of COPD. J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jan 28];6(11):1615–31. Available from: https://jtd.amegroups.org/article/view/3329/html.

- van Manen, J.G.; E Bindels, P.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Ijzermans, C.J.; van der Zee, J.S.; Schadé, E. Risk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants. Thorax 2002, 57, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioanna, T.; Kocks, J.; Tzanakis, N.; Siafakas, N.; van der Molen, T. Factors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlations. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2011, 20, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy, E.L.; Beaulieu, N.U.; McHale, J.M.; Welland, T.R.; Plauschinat, C.A.; Swensen, A.; Duh, M.S. Treatment of COPD: Relationships between daily dosing frequency, adherence, resource use, and costs. Respir. Med. 2010, 105, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquart, J.B.; Le Rouzic, O.; Racil, G.; Wallaert, B.; Grosbois, J.-M. Real-life feasibility and effectiveness of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring medical equipment. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, ume 12, 3549–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, S.C.; Yawn, B.P. Improving adherence with inhaler therapy in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2010, 5, 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance With Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 2000 Jul 24 [cited 2025 Jan 28];160(14):2101–7. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/485411.

- van Boven, J.F.; Chavannes, N.H.; van der Molen, T.; Mölken, M.P.R.-V.; Postma, M.J.; Vegter, S. Clinical and economic impact of non-adherence in COPD: A systematic review. Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbeau J, Bartlett SJ. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax [Internet]. 2008 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jan 28];63(9):831–8. Available from: https://thorax.bmj.

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Seemungal, T.A.R. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet 2007, 370, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Gestoso, S.; García-Sanz, M.-T.; Carreira, J.-M.; Salgado, F.-J.; Calvo-Álvarez, U.; Doval-Oubiña, L.; Camba-Matos, S.; Peleteiro-Pedraza, L.; González-Pérez, M.-A.; Penela-Penela, P.; et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on the prognosis of copd exacerbations. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, N.A.; Müllerova, H.; Locantore, N.W.; Vestbo, J.; Watkins, M.L.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Rennard, S.I.; Sharafkhaneh, A. Determinants of Depression in the ECLIPSE Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, K.E.; Plaufcan, M.R.; Ford, D.W.; Sandhaus, R.A.; Strand, M.; Strange, C.; Wamboldt, F.S. The impact of age on outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease differs by relationship status. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 37, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson I. Depression in the patient with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 Jan 28];1(1):61–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18046903/.

- van Manen, J.G.; E Bindels, P.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Ijzermans, C.J.; van der Zee, J.S.; Schadé, E. Risk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants. Thorax 2002, 57, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagena, E.J.; Kant, I.; Huibers, M.J.; van Amelsvoort, L.G.; Swaen, G.M.; Wouters, E.F.; van Schayck, C.P. Psychological distress and depressed mood in employees with asthma, chronic bronchitis or emphysema: A population-based observational study on prevalence and the relationship with smoking cigarettes. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2003, 19, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, N.; Peterson, E.L.; Schultz, L.R.; Chilcoat, H.D.; Andreski, P. Major Depression and Stages of Smoking. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998, 55, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, A.; Kenny, P.J. Neuroadaptations to chronic exposure to drugs of abuse: Relevance to depressive symptomatology seen across psychiatric diagnostic categories. Neurotox. Res. 2002, 4, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Chen, P.; Zhang, P.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J. Effects of Smoking, Depression, and Anxiety on Mortality in COPD Patients: A Prospective Study. Respir. Care 2014, 59, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.; Mallow, J.; Theeke, L. Health-Related Quality of Life, Depression, and Smoking Status in Patients with COPD: Results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Data. Open J. Nurs. 2018, 08, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Shore, X.; Mohite, S.; Myers, O.; Kesler, D.; Vlahovich, K.; Sood, A. Association between Spirometric Parameters and Depressive Symptoms in New Mexico Uranium Workers. Southwest J. Pulm. Crit. Care 2021, 22, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Chung, K.S.; Song, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, E.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; Park, M.S.; Chang, J.; et al. Relationship between depression and lung function in the general population in Korea: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, ume 13, 2207–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Cao, J.; Cheng, P.; Shi, D.; Cao, B.; Yang, G.; Liang, S.; Su, N.; Yu, M.; Zhang, C.; et al. Moderate-to-Severe Depression Adversely Affects Lung Function in Chinese College Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schane RE, Woodruff PG, Dinno A, Covinsky KE, Walter LC. Prevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2008 Nov [cited 2025 Jan 29];23(11):1757–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18690488/.

- A Cleland, J.; Lee, A.J.; Hall, S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam. Pr. 2007, 24, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jácome, C.; Figueiredo, D.; Gabriel, R.; Cruz, J.; Marques, A. Predicting anxiety and depression among family carers of people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2014, 26, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gestoso, S.; García-Sanz, M.-T.; Carreira, J.-M.; Salgado, F.-J.; Calvo-Álvarez, U.; Doval-Oubiña, L.; Camba-Matos, S.; Peleteiro-Pedraza, L.; González-Pérez, M.-A.; Penela-Penela, P.; et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on the prognosis of copd exacerbations. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, D.L.; Pizzichini, M.M.; Hoepers, A.T.; Diaz, A.P.; Karloh, M.; Dias, M.; Pizzichini, E. Prevalence of depression in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Respir. Med. 2016, 117, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Otto MW, Rosenbaum JF, Kradin RL. Panic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease. Theoretical and clinical considerations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2025 Jan 29];154(1):6–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8680700/.

- Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2025 Jan 29];50(4):306–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8466392/.

- Patton GC, Hibbert M, Rosier MJ, Carlin JB, Caust J, Bowes G. Is smoking associated with depression and anxiety in teenagers? Am J Public Health [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2025 Jan 29];86(2):225. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1380332/.

- O'Donnell, D.E.; Banzett, R.B.; Carrieri-Kohlman, V.; Casaburi, R.; Davenport, P.W.; Gandevia, S.C.; Gelb, A.F.; Mahler, D.A.; Webb, K.A. Pathophysiology of Dyspnea in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Roundtable. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2007, 4, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, C.J.; Moxham, J. A physiological model of patient-reported breathlessness during daily activities in COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2009, 18, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, M.; Brannan, S.; Egan, G.; Shade, R.; Madden, L.; Abplanalp, B.; Robillard, R.; Lancaster, J.; Zamarripa, F.E.; Fox, P.T.; et al. Brain responses associated with consciousness of breathlessness (air hunger). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 2035–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.C.; Banzett, R.B.; Adams, L.; McKay, L.; Frackowiak, R.S.J.; Corfield, D.R. BOLD fMRI Identifies Limbic, Paralimbic, and Cerebellar Activation During Air Hunger. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 88, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey PH. The dyspnea-anxiety-dyspnea cycle - COPD patients’ stories of breathlessness: “It’s scary/when you can’t breathe.” Qual Health Res [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2025 Jan 29];14(6):760–78. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8506490_The_Dyspnea-Anxiety-Dyspnea_Cycle-COPD_Patients’_Stories_of_Breathlessness_It’s_Scary_When_you_Can’t_Breathe.

- McKenzie, D.K.; Butler, J.E.; Gandevia, S.C.; Lagerquist, O.; Walsh, L.D.; Blouin, J.-S.; Collins, D.F. Respiratory muscle function and activation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.B.; Telch, M.J.; Jaimez, T.L. Biological challenge manipulation of PCO₂ levels: A test of Klein's (1993) suffocation alarm theory of panic. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1996, 105, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohannes, A.M.; Roomi, J.; Baldwin, R.C.; Connolly, M.J. Depression in elderly outpatients with disabling chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Age and Ageing 1998, 27, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.F.S.; Kunik, M.E.; Molinari, V.A.; Hillman, S.L.; Lalani, S.; Orengo, C.A.; Petersen, N.J.; Nahas, Z.; Goodnight-White, S. Functional Impairment in COPD Patients: The Impact of Anxiety and Depression. Psychosomatics 2000, 41, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Dowson, C.; Town, G.; Frampton, C.; Mulder, R.T. Psychopathology and illness beliefs influence COPD self-management. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 56, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDF) Neuropsychiatric function in chronic lung disease: The role of pulmonary rehabilitation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23185128_Neuropsychiatric_function_in_chronic_lung_disease_The_role_of_pulmonary_rehabilitation.

- Graydon, J.E.; Ross, E. Influence of symptoms, lung function, mood, and social support on level of functioning of patients with COPD. Res. Nurs. Heal. 1995, 18, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, L.; Collins, C. The Poorly Coping COPD Patient: A Psychotherapeutic Perspective. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1982, 11, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau N, Marlyne Kilbey M, Andreski P. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry [Internet]. 1992 [cited 2025 Jan 29];149(4):464–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1554030/.

- Fergusson, D.M.; Lynskey, M.T.; Horwood, L.J. Comorbidity Between Depressive Disorders and Nicotine Dependence in a Cohort of 16-Year-Olds. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwood, R.J. A review of etiologies of depression in COPD. 2007, 2, 485–491.

- Van Dijk EJ, Vermeer SE, De Groot JC, Van De Minkelis J, Prins ND, Oudkerk M, et al. Arterial oxygen saturation, COPD, and cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2025 Jan 29];75(5):733. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1763550/.

- Campbell JJ, Coffey CE. Neuropsychiatric significance of subcortical hyperintensity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2025 Jan 29];13(2):261–88. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11449035/.

- El-Ad B, Lavie P. Effect of sleep apnea on cognition and mood. Int Rev Psychiatry [Internet]. 2005 Aug [cited 2025 Jan 29];17(4):277–82. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7569893_Effect_of_sleep_apnea_on_cognition_and_mood.

- zge C, Özge A, Ünal Ö. Cognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPD. Behav Neurol [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 Jan 29];17(2):121–30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16873924/.

- Aloia, M.S.; Arnedt, J.T.; Davis, J.D.; Riggs, R.L.; Byrd, D. Neuropsychological sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: A critical review. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004, 10, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M. Evidence for an immune response in major depression: A review and hypothesis. 2000, 19, 11–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-5846(94)00101-m. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.M.; Connor, T.J.; Harkin, A. Stress-Related Immune Markers in Depression: Implications for Treatment. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 19, pyw001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybka, J.; Korte, S.M.; Czajkowska-Malinowska, M.; Wiese, M.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K.; Kędziora, J. The links between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid depressive symptoms: role of IL-2 and IFN-γ. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 16, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther [Internet]. 2006 Jul [cited 2025 Jan 29];8 Suppl 2(Suppl 2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16899107/.

- Campbell, I.L.; Erta, M.; Lim, S.L.; Frausto, R.; May, U.; Rose-John, S.; Scheller, J.; Hidalgo, J. Trans-Signaling Is a Dominant Mechanism for the Pathogenic Actions of Interleukin-6 in the Brain. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 2503–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomarat, P.; Banchereau, J.; Davoust, J.; Palucka, A.K. IL-6 switches the differentiation of monocytes from dendritic cells to macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, C.; Widner, B.; Wirleitner, B.; Fuchs, D. Neopterin as a Marker for Immune System Activation. Curr. Drug Metab. 2002, 3, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Scharpé, S.; Meltzer, H.Y.; Okayli, G.; Bosmans, E.; D'Hondt, P.; Bossche, B.V.; Cosyns, P. Increased neopterin and interferon-gamma secretion and lower availability of L-tryptophan in major depression: Further evidence for an immune response. Psychiatry Res. 1994, 54, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. The Cytokine Network in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 41, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, T.J.; Leonard, B.E. Depression, stress and immunological activation: The role of cytokines in depressive disorders. Life Sci. 1998, 62, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvinen, M.; Campwala, H.; Kilty, I. The role of IFN-γ in regulation of IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) expression in lung epithelial cell and peripheral blood mononuclear cell co-cultures. Respir. Res. 2007, 8, 80–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2025 Jan 29];96:41–101. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17981204/.

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2025 Jan 29];284(20):2606–10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11086367/.

- Berlin, I.; Covey, L.S. Pre-cessation depressive mood predicts failure to quit smoking: the role of coping and personality traits*. Addiction 2006, 101, 1814–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torvinen, M.; Campwala, H.; Kilty, I. The role of IFN-γ in regulation of IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) expression in lung epithelial cell and peripheral blood mononuclear cell co-cultures. Respir. Res. 2007, 8, 80–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowler, R.P.; Barnes, P.J.; Crapo, J.D. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2004, 1, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRYOR WA, STONE K. Oxidants in cigarette smoke. Radicals, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrate, and peroxynitrite. Ann N Y Acad Sci [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2025 Jan 30];686(1):12–27. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8512242/.

- Langen, R.; Korn, S.; Wouters, E. ROS in the local and systemic pathogenesis of COPD. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 35, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunyer, J. Urban air pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 17, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeptar, A.R.; Scheerens, H.; Vermeulen, N.P.E. Oxygen and Xenobiotic Reductase Activities of Cytochrome P450. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1995, 25, 25–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Ü.; Ünlü, M.; Özgüner, F.; Sütçü, R.; Akkaya, A.; Delibaş, Ν. Lipid Peroxidation and Changes of Glutathione Peroxidase Activity in Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbation: Prognostic Value of Malondialdehyde. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Skwarska, E.; MacNee, W. Attenuation of oxidant/antioxidant imbalance during treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1997, 52, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- alikoǧlu M, Ünlü A, Tamer L, Ercan B, Buǧdayci R, Atik U. The levels of serum vitamin C, malonyldialdehyde and erythrocyte reduced glutathione in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in healthy smokers. Clin Chem Lab Med [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Jan 30];40(10):1028–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12476943/.

- Paredi P, Kharitonov SA, Leak D, Ward S, Cramer D, Barnes PJ. Exhaled ethane, a marker of lipid peroxidation, is elevated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2025 Jan 30];162(2 Pt 1):369–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10934055/.

- Montuschi, P.; Collins, J.V.; Ciabattoni, G.; Lazzeri, N.; Corradi, M.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J. Exhaled 8-Isoprostane as an In Vivo Biomarker of Lung Oxidative Stress in Patients with COPD and Healthy Smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 1175–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias JR, Díez-Manglano J, García FL, Peromingo JAD, Almagro P, Aguilar JMV. Management of the COPD Patient with Comorbidities: An Experts Recommendation Document. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 31];15:1015–37. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32440113/.

- Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. 2007 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jan 31];370(9589):765–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17765526/.

- Aggarwal, A.N. The 2022 update of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Noncommunicable Dis. 2022, 7, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gestoso, S.; García-Sanz, M.-T.; Carreira, J.-M.; Salgado, F.-J.; Calvo-Álvarez, U.; Doval-Oubiña, L.; Camba-Matos, S.; Peleteiro-Pedraza, L.; González-Pérez, M.-A.; Penela-Penela, P.; et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on the prognosis of copd exacerbations. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Zhou, A.; Ping, C.; Shuang, Q. CODEXS: A New Multidimensional Index to Better Predict Frequent COPD Exacerbators with Inclusion of Depression Score. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, D.R.; Lavoie, K.L. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, ume 12, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rábade Castedo C, de Granda-Orive JI, González-Barcala FJ. Incremento de la prevalencia del tabaquismo: ¿causas y actuación? Arch Bronconeumol [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Jan 31];55(11):557–8. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/113125541/Incremento_de_la_prevalencia_del_tabaquismo_causas_y_actuación.

- Nair, P.; Walters, K.; Aw, S.; Gould, R.; Kharicha, K.; Marta College Marta College Buszewicz,; Frost, R. Self-management of depression and anxiety amongst frail older adults in the United Kingdom: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0264603. [CrossRef]

- Bugajski, A.; Morgan, H.; Wills, W.; Jacklin, K.; Alleyne, S.; Kolta, B.; Lengerich, A.; Rechenberg, K. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with COPD: Modifiable Explanatory Factors. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 45, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Chang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, H. Unraveling the mediation role of frailty and depression in the relationship between social support and self-management among Chinese elderly COPD patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunque, A.; Li, G.; MacNeil, A.; Gulati, I.; Jiang, Y.; de Groh, M.; Fuller-Thomson, E. Breathless and Blue in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging: Incident and Recurrent Depression Among Older Adults with COPD During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 1975–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.G. Do Antidepressants Worsen COPD Outcomes in Depressed Patients with COPD? Pulm. Ther. 2024, 10, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, L.J.; Wroblewski, K.E.; Pinto, J.M.; Wang, E.; McClintock, M.K.; Dale, W.; White, S.R.; Press, V.G.; Huisingh-Scheetz, M. Beyond the Lung: Geriatric Conditions Afflict Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Self-Reported Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 814606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. https://doi.org/101164/rccm201204-0596PP [Internet]. 2013 Mar 22 [cited 2025 Jan 31];187(4):347–65. Available from: www.goldcopd.org.

- Mathers, C.D.; Loncar, D. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLOS Med. 2006, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gut-Gobert C, Cavaillès A, Dixmier A, Guillot S, Jouneau S, Leroyer C, et al. Women and COPD: do we need more evidence? Eur Respir Rev [Internet]. 2019 Feb 27 [cited 2025 Jan 31];28(151). Available from: https://publications.ersnet.org/content/errev/28/151/180055.

- Sheel, A.W.; Guenette, J.A.; Yuan, R.; Holy, L.; Mayo, J.R.; McWilliams, A.M.; Lam, S.; Coxson, H.O. Evidence for dysanapsis using computed tomographic imaging of the airways in older ex-smokers. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Curtis, J.L.; Sciurba, F.; Mumford, J.; Giardino, N.D.; Weinmann, G.; Kazerooni, E.; Murray, S.; Criner, G.J.; Sin, D.D.; et al. Sex Differences in Severe Pulmonary Emphysema. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi JS, Kwak SH, Son NH, Oh JW, Lee S, Lee EH. Sex differences in risk factors for depressive symptoms in patients with COPD: The 2014 and 2016 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Pulm Med [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jan 31];21(1). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351953327_Sex_differences_in_risk_factors_for_depressive_symptoms_in_patients_with_COPD_The_2014_and_2016_Korea_National_Health_and_Nutrition_Examination_Survey.

- Milne, K.M.; Mitchell, R.A.; Ferguson, O.N.; Hind, A.S.; Guenette, J.A. Sex-differences in COPD: from biological mechanisms to therapeutic considerations. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1289259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun, M.J.; Carter, B.D.; Feskanich, D.; Freedman, N.D.; Prentice, R.; Lopez, A.D.; Hartge, P.; Gapstur, S.M. 50-Year Trends in Smoking-Related Mortality in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrová, L.; Kuriplachová, G.; Ištoňová, M.; Nechvátal, P.; Mikuľáková, W.; Takáč, P. Assessment of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Kontakt 2014, 16, e203–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.L.R.S.; Conde, M.B.; Corrêa, K.d.S.; da Silva, C.; Prestes, L.d.S.; Rabahi, M.F. COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score as a predictor of major depression among subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and mild hypoxemia: a case–control study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2014, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res. 2011 Nov;63(SUPPL. 11).

- Rebbapragada, V.; Hanania, N.A. Can We Predict Depression in COPD? COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2007, 4, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Park, S.; Oh, Y.-M.; Lee, S.-D.; Park, S.-W.; Kim, Y.S.; In, K.H.; Jung, B.H.; Lee, K.H.; Ra, S.W.; et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test Can Predict Depression: A Prospective Multi-Center Study. J. Korean Med Sci. 2013, 28, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas [Internet]. 1977 [cited 2025 Feb 10];1(3):385–401. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/98561.

- Wada K, Yamada N, Suzuki H, Lee Y, Kuroda S. Recurrent cases of corticosteroid-induced mood disorder: clinical characteristics and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2025 Feb 10];61(4):261–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10830146/.

- Fletcher, C.; Peto, R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ 1977, 1, 1645–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, P.; E Chacko, E.; Wood-Baker, R.; Cates, C.J. Influenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, CD002733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale PA, Conway WA, Coates EO. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 1980 [cited 2025 Jan 31];93(3):391–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6776858/.

- Donohue, J.F.; van Noord, J.A.; Bateman, E.D.; Langley, S.J.; Lee, A.; Witek, T.J.; Kesten, S.; Towse, L. A 6-Month, Placebo-Controlled Study Comparing Lung Function and Health Status Changes in COPD Patients Treated With Tiotropium or Salmeterol. Chest 2002, 122, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A F, F M, K N, S P, R W, A R, et al. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2003 May 22 [cited 2025 Jan 31];348(21):2059–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12759479/.

- Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lacasse Y, editor. Cochrane database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2006 Oct 18 [cited 2025 Jan 31];(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17054186/.

- Effing, T.; Monninkhof, E.M.; van der Valk, P.D.; van der Palen, J.; van Herwaarden, C.L.; Partidge, M.R.; Walters, E.H.; Zielhuis, G.A. Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 4, CD002990–1. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Rasul, F.M. Steroid-induced psychosis treated with haloperidol in a patient with active chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1999, 17, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.S.; Suppes, T.; Khan, D.A.; Carmody, T.J. Mood Changes During Prednisone Bursts in Outpatients With Asthma. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 22, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis DA, Smith RE. Steroid-induced psychiatric syndromes. A report of 14 cases and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 1983 [cited 2025 Jan 31];5(4):319–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6319464/.

- Ciriaco M, Ventrice P, Russo G, Scicchitano M, Mazzitello G, Scicchitano F, et al. Corticosteroid-related central nervous system side effects Case Review. J Pharmacol Pharmacother [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jan 31]; Available from: www.jpharmacol.com.

- Keul, F.; Hamacher, K. Consistent Quantification of Complex Dynamics via a Novel Statistical Complexity Measure. Entropy 2022, 24, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, P.M.; Abdalla, M.; Bissell, B.; Malesker, M.A.; Santibañez, M.; Smith, Z. Theophylline for the management of respiratory disorders in adults in the 21st century: A scoping review from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Pulmonary Practice and Research Network. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2023, 43, 963–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Pharmacologic Treatment of Depression in Older Patients with COPD: Impact on the Course of the Disease and Health Outcomes. Drugs Aging [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Mar 6];31(7):483. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4522901/.

- ZuWallack, R. The Nonpharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Advances in Our Understanding of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2007, 4, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockley RA. Biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: confusing or useful? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis [Internet]. 2014 Feb 7 [cited 2025 Jan 31];9:163. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3923613/.

- Spruit, M.A.; Singh, S.J.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Rochester, C.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Man, W.D.-C.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Key Concepts and Advances in Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery CF, Schein RL, Hauck ER, MacIntyre NR. Psychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Psychol [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2025 Jan 31];17(3):232–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9619472/.

- Jácome, C.; Marques, A. Impact of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Subjects With Mild COPD. Respir. Care 2014, 59, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güell, R.; Resqueti, V.; Sangenis, M.; Morante, F.; Martorell, B.; Casan, P.; Guyatt, G.H. Impact of Pulmonary Rehabilitation on Psychosocial Morbidity in Patients With Severe COPD. Chest 2006, 129, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, R.L.; Middelboe, T.; Pisinger, C.; Stage, K.B. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A review. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2004, 58, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, Tzanakis N. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis [Internet]. 2015 Jan 7 [cited 2025 Jan 31];10:95. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4293292/.

- Anxiety: Management of anxiety (panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, and generalised anxiety disorder) in adults in primary, secondary and community care | Guidance | NICE.

- Nelson, D.R. The Cytochrome P450 Homepage. Hum. Genom. 2009, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Siraj, R.; E Bolton, C.; McKeever, T.M. Association between antidepressants with pneumonia and exacerbation in patients with COPD: a self-controlled case series (SCCS). Thorax 2023, 79, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarella, P.A.; Effing, T.W.; Usmani, Z.; Frith, P.A. Treatments for anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A literature review. Respirology 2012, 17, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.C. Respiratory depression with diazepam: potential complications and contraindications.. 1978, 25, 117–8.

- Man, G.; Hsu, K.; Sproule, B. Effect of Alprazolam on Exercise and Dyspnea in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chest 1986, 90, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan AG, Kaplan AG. Do Antidepressants Worsen COPD Outcomes in Depressed Patients with COPD? Pulm Ther [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Mar 6];10(4):411. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11574234/.

- Hegerl U, Mergl R. Depression and suicidality in COPD: understandable reaction or independent disorders? Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2014 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jan 31];44(3):734–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24876171/.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).