1. Introduction

Avian influenza A viruses (AIVs), particularly the high pathogenicity AIV (HPAIV) H5 subtype, pose a persistent threat to animals and human health worldwide [

1,

2]. The ongoing H5N1 epidemic in North America, marked by substantial avian mortality and an increasing number of human cases, urgently demands improved surveillance and control strategies [

3]. As of October 2024, the U.S. was facing a severe HPAIV outbreak, evidenced by a 7% seroprevalence among farm workers and the first identification of a severe human case, which was linked to exposure to infected poultry and dairy cows [

4,

5]. In response, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other groups have expanded their wastewater surveillance systems to include AIVs [

6,

7]. While they successfully detected AIVs in wastewater, the limited number of wastewater treatment plants processing animal waste and the unclear coverage of dairy farm effluent present significant limitations.

AIVs infects aquatic bird populations, especially migratory waterfowl, which serve as natural reservoirs [

8]. These birds can shed large amounts of viruses via their feces and respiratory secretions, contaminating surface waters and facilitating transmission via the fecal–oral route [

9]. AIVs’ environmental persistence plays a crucial role in the ecology and transmission dynamics of viruses. Recent research has shown that colony-breeding seabirds are taking an increasing role as reservoirs, extending the period of virus circulation to include summer months [

10]. Despite the recognized importance of environmental surveillance for AIVs, conventional techniques often lack the sensitivity and efficiency needed to provide a comprehensive understanding of viral persistence and transmission dynamics in aquatic environments. This limitation hinders our ability to accurately assess risks, predict outbreaks, and implement timely interventions.

The present study addresses this critical gap by developing and evaluating a novel and highly sensitive workflow for AIV surveillance with environmental water. Our approach includes two innovative technologies: QuickConc, a cationic-assisted nucleic acid concentration method [

11], and COPMAN, a highly sensitive and efficient nucleic acid extraction technique. It also makes use of reverse transcription (RT)-preamplification (Preamp)-quantitative PCR (qPCR), which is optimized for wastewater samples [

12]. We hypothesize that this workflow will significantly enhance AIV detection, compared to conventional methods, enabling the more effective monitoring of viral presence and distribution in aquatic ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Japan’s Ministry of the Environment conducts surveys on the migration status of birds with the aim of contributing to the effective and swift implementation of preventive measures against HPAIVs by local governments through the centralized collection, organization, and provision of information on the migration timing and number of migratory birds in the country. In this study, sampling was conducted at the Futatsudate Retention Basin (32°03'37"N latitude, 131°49'53"E longitude), which is one of the 52 national migratory bird observation sites in Japan, on January 15 and 29, March 4, and September 4, 2024 [

13]. All samples were collected from surface water via grab sampling and stored at 4 °C until processing in the laboratory. All samples except those used for chicken-derived red blood cell (RBC) binding-based virus concentration received 10 w/v % OSVAN S (Nihon Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) as a benzalkonium chloride source, which was added at a final concentration of 0.01% on site immediately after water sampling for preservation against RNA degradation [

14].

2.2. Virus Preparation

A/duck/Miyazaki/CAD-1/2016(H4N2) strain (Accession number: LC415031-8) was used in this study The copy number was determined by RT-qPCR [

15]. In virus-spiked experiments, the virus was added into 300 mL of each water sample, all of which were confirmed to be negative for the M gene, in a range of 2.56 to 6.56 log

10 copies/L at 10-fold dilutions.

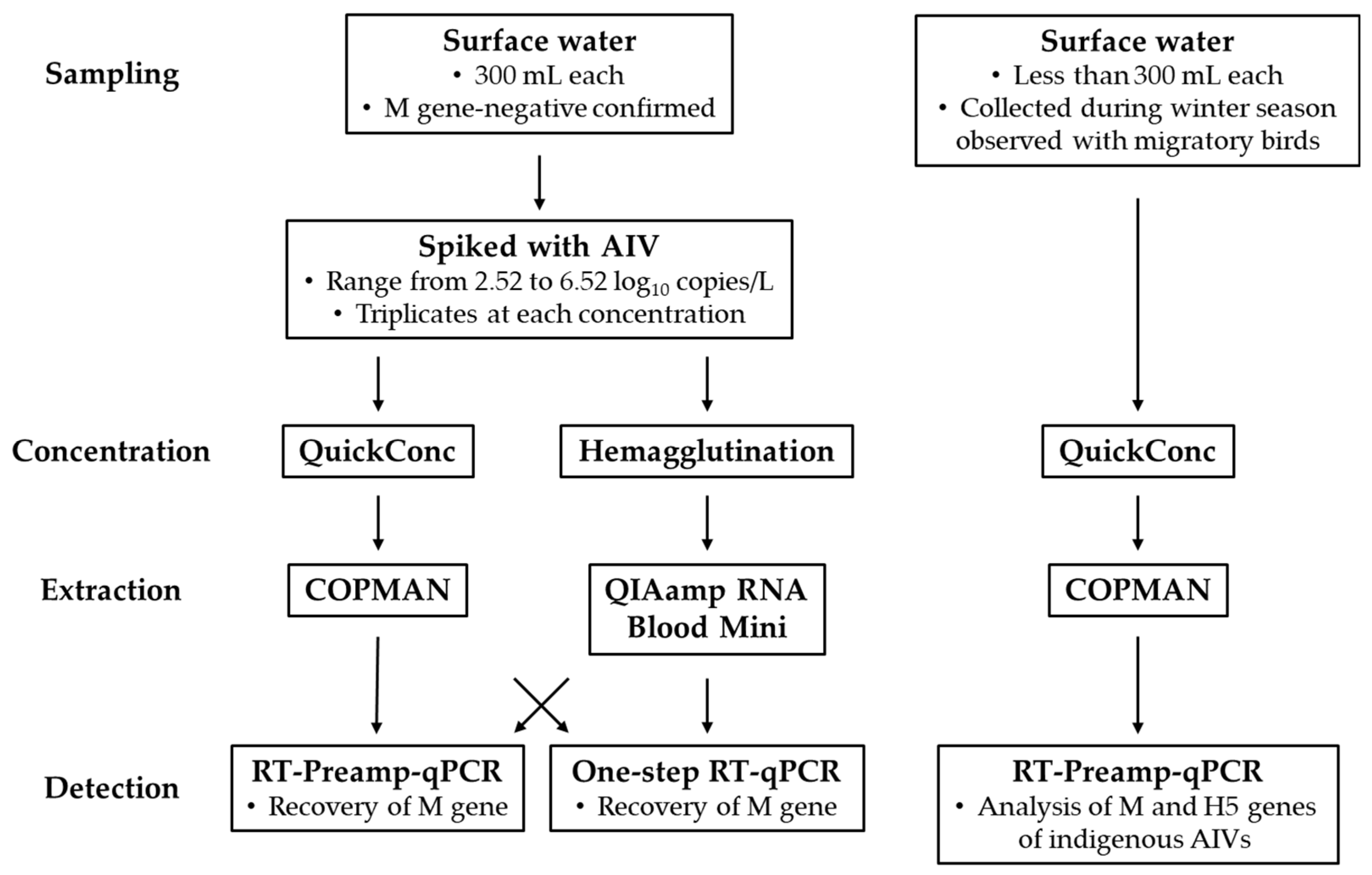

2.3. Outline of AIV Detection Workflows

The series of operations for gene detection in environmental water is typically divided into four steps: sampling, concentration, extraction, and detection. In our original workflow, we adopted QuickConc for the concentration step, a COPMAN kit for the extraction step, and the RT-Preamp-qPCR method was used in the COPMAN for the detection step [

11,

12]. By contrast, the hemagglutination assay, spin column technique, and one-step RT-qPCR methods were used for the concentration, extraction, and detection steps, respectively, as controls [

16,

17,

18].

2.4. Concentration and RNA Extraction

A combination of QuickConc (AdvanSentinel, Osaka, Japan) and a COPMAN DNA/RNA extraction kit (AdvanSentinel) was used, with slight modifications, as described previously [

11,

12]. Briefly, one piece of glass fiber sheet (1 cm square) was added to a 2-liter bag filled with a water sample, followed by vigorous stirring and a 1-minute resting period. The dispersed glass fibers were then collected using a mesh filter and transferred to a 2 mL tube, where 350 μL of Lysis buffer with 2mM DTT and 20 μL of proteinase K were added, following its incubation at 56 °C for 10 min. Crude RNA of 200 μL was extracted from the samples with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), which was then purified with magnetic beads to obtain a final extract volume of 60 μL. The combination of a hemagglutination assay and a QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was also used, with some modifications [

16,

17]. Briefly, 5 mL of 10× concentration of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 1.2 mL of 10% RBCs (Japan Bioserum, Fukuyama, Japan) were added to 43.8 mL of environmental water. The mixture was rotated for 3 hrs at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the RBC pellet was resuspended in 1.2 mL of PBS, followed by RNA extraction from 1 mL of RBC suspension by adding 600 µL of Buffer RLT to the pellet. Subsequent operations were performed according to the manufacturers' protocols, and 60 µL of nucleic acids were obtained.

2.5. Detection of Viral Genes

qPCR analyses were conducted to quantify the RNA derived from water samples using primers specific to influenza A viruses with the M gene and subtype H5. The primers and TaqMan probe designs were aligned with previous studies (

Table 1) [

19,

20], ensuring specificity and reliability (

Table 2). Since we previously reported that the Preamp reaction effectively increased the target gene copy numbers without any major effects on qPCR’s quantitative performance, the same reaction conditions were employed in this study, with slight modifications [

12]. Briefly, the RNAs of the M and H5 segments were converted to cDNA using a Reliance Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules. CA. USA) with a 14 μL template and then amplified with Biotaq HS (Bioline Reagents, London, UK), followed by TaqMan Environmental Master Mix 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. As a control method for detecting AIV genes, a one-step RT-PCR assay was also adopted [

18,

19]. Briefly, the M gene was amplified using One step PrimeScript Ш RT-qPCR Mix (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Results

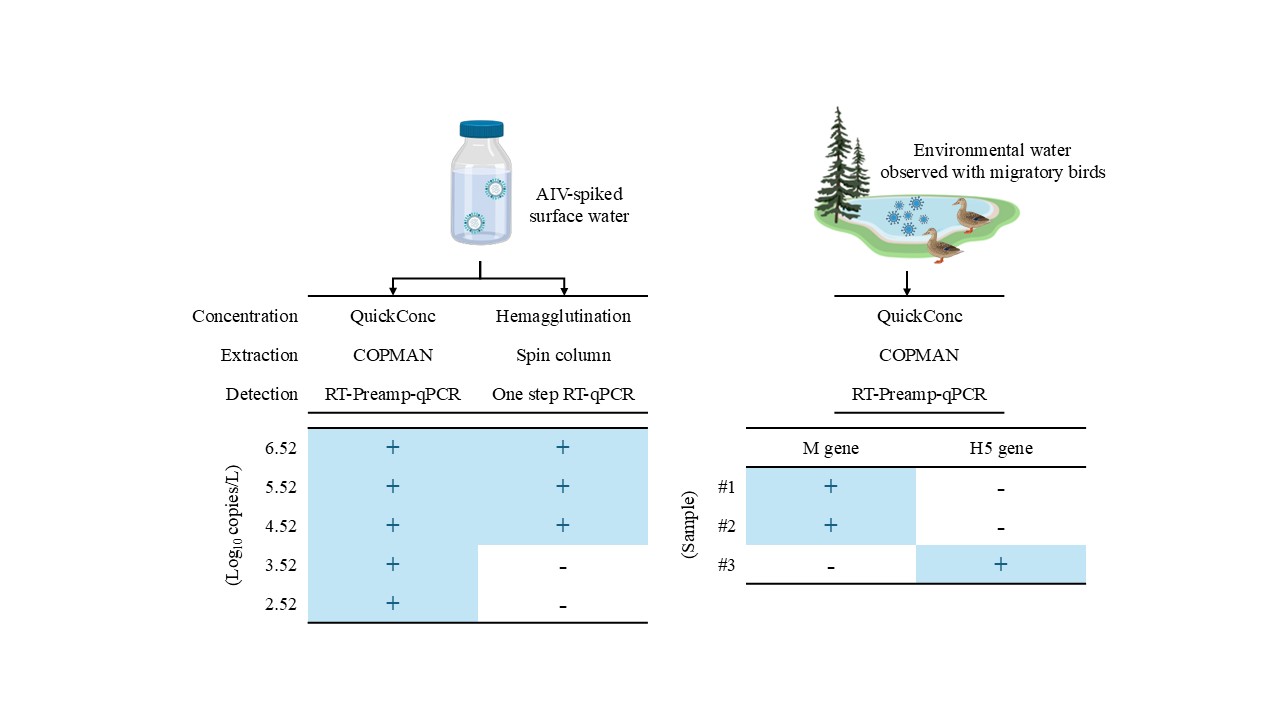

The objective of this study was to establish a workflow capable of detecting AIV genes from environmental water with high sensitivity using qPCR technology. To accomplish this, two approaches were employed. First, since both the efficient recovery and purification of minute amounts of viral RNA from the samples and efficient amplification of the specific genes contained therein was crucial, the process was systematically deconstructed into concentration–extraction and detection, so as to conduct a comparative analysis of detection sensitivity between our workflow and the control workflow that combined conventional methodologies. Second, a proof of concept validation of our workflow was performed using samples collected from natural aquatic environments (

Figure 1).

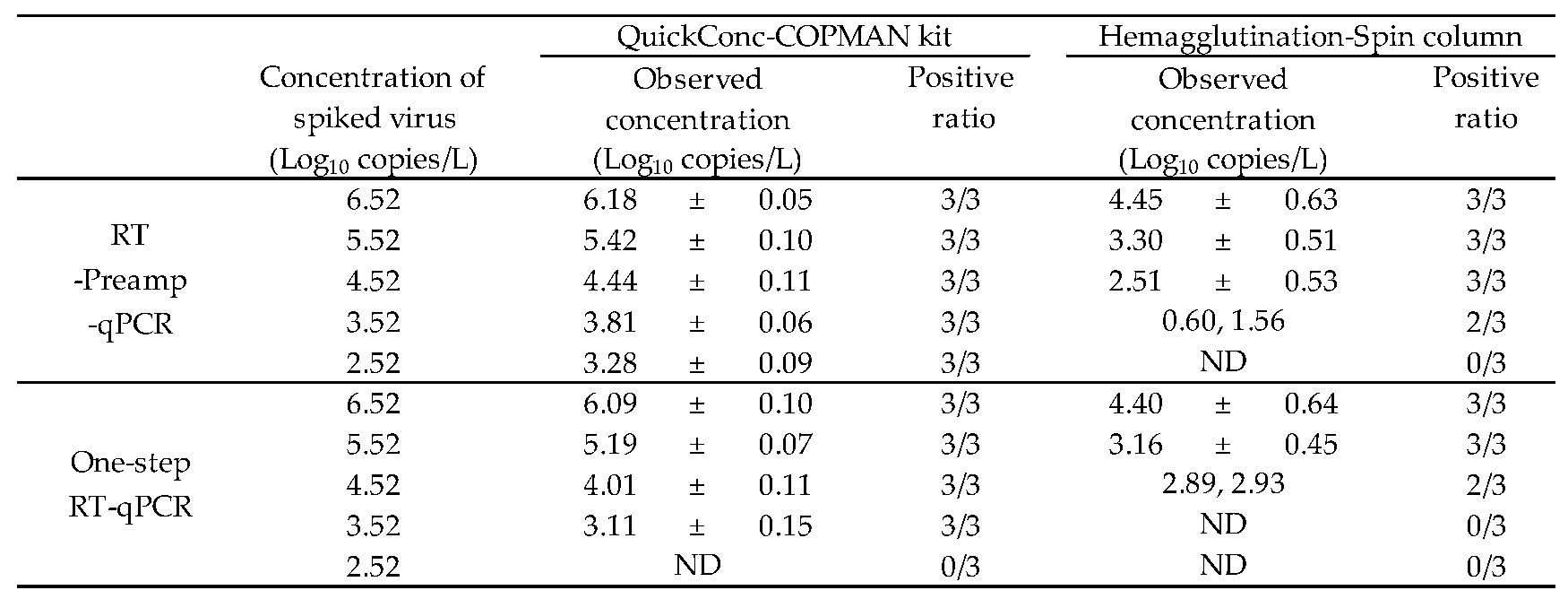

To evaluate the first approach, water samples spiked with cultured H4N2 virus were prepared. As shown in

Table 3, with the combination of the Hemagglutination-Spin column and one-step RT-qPCR as the control workflow, H4N2 RNA was detected from all tested samples with a concentration of 5.52 log10 copies/L, from 67% of those with a concentration of 4.52 log10 copies/L, and never from those with a concentration of 3.52 log10 copies/L. Compared to this workflow, when the concentration–extraction step was altered to employ the QuickConc-COPMAN kit, H4N2 RNA was detected from all tested samples with a concentration of 3.52 log10 copies/L, indicating a 10-fold increase in the sensitivity, relative to the control workflow. In addition, when only the detection step was altered to the RT-Preamp-qPCR, H4N2 RNA was detected from all tested samples with a concentration of 4.52 log10 copies/L, from 67% of those with a concentration of 3.52 log10 copies/L, and never from those with a concentration of 2.52 log10 copies/L. These data indicated that the modification of the detection step also resulted in a 10-fold increase in sensitivity. Further, with the combination of the QuickConc-COPMAN kit and RT-Preamp-qPCR, H4N2 RNA was detected from all tested samples with a concentration of 2.52 log10 copies/L, demonstrating that our workflow was two orders of magnitude more sensitive than the control workflow. This difference led to a resulting 10-fold increase in sensitivity in both the concentration–extraction step and in the detection step. The results showing the amount of recovered H4N2 RNA expressed in Ct values relative to the actual number of spiked copies added to the water samples are shown in

Table S1.

To verify the functionality of our workflow for the detection of indigenous AIVs from environmental water, surface water was collected during the 2023-24 winter season, when the presence of migratory birds was confirmed. RNA derived from water samples ranging from 200 to 400 mL was used as a template, allowing the universal M gene to be quantitively detected in two out of three specimens. Notably, the H5 subtype gene was also successfully quantified in one out of three specimens (

Table 4). We used Sanger sequencing to confirm that these amplified genes were not artifacts (data not shown). These data indicated that our workflow allowed the detection of indigenous AIVs from surface water samples collected from the body of water visited by migratory birds.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated a novel workflow for investigating AIV genes from environmental water. Our workflow incorporates two critical factors that contribute to its enhanced sensitivity: the efficient recovery and purification of nucleic acids from small volumes of environmental water, during the concentration–extraction step, and the increment of input RNA, by adopting the RT-Preamp-qPCR method in the detection step. Some other studies have been successful in detecting AIV genes in water bodies using samples of several tens of liters to examine the presence of the AIV genes [

21,

22]. This is because the concentration of AIV genes in bodies of water is expected to be extremely low. By contrast, our streamlined approach would enable more frequent and comprehensive sampling regimens, potentially facilitating more widespread implementation of AIV monitoring.

As shown in

Table 4, we succeeded in detecting both M and H5 genes using less than 500 mL of environmental water. We employed QuickConc and a COPMAN kit in the concentration–extraction step of our workflow. QuickConc has demonstrated superior performance in recovering environmental DNA from water samples and exhibited a marked improvement over conventional methods such as Sterivex filtration. Concurrently, COPMAN kits have proven highly effective for purifying nucleic acids from wastewater samples with high levels of contaminants [

11,

12]. In addition, total RNA was extracted from water samples to obtain a final RNA extract volume of 60-μL solution. Of these extracts, 14 μL of RNA extract (i.e., 23% of 60 μL) is used for the amplification reaction in a 20-μL mixture. Theoretically, in the case of preparing a 500 mL water sample, an equivalent water volume of 63 mL (12.6% of 500 mL) could be analyzed using our detection methodology. In contrast, 2 μL of RNA extract (3.3% of 60 μL) is used for one-step RT-qPCR, and only 13.9 mL (2.8% of 500 mL) is analyzed in this method. This difference in input RNA volume enabled a reduction in the detection limit (

Table 3, comparing detection technologies). We suggest that the combination of these novel approaches allows us to detect AIV genes with high sensitivity, despite dramatically decreasing the volume of the water samples. Furthermore, our spike experiments demonstrated a virus recovery rate of over 43% calculated by a linear scale (

Table 3), whereas a previous paper reported an average virus recovery rate of just 1.9%, indicating that our workflow is able to more accurately measure the concentration of AIV genes in environmental water [

21].

This study presents several limitations that warrant consideration. First, there is a paucity of AIV-detected environmental samples. To comprehensively evaluate the efficacy of our workflow in water surveys, it is imperative to conduct longitudinal analyses with an increased number of samplings across multiple water bodies frequented by migratory birds. Second, while our study has successfully validated the triad of concentration, extraction, and detection steps, the sampling step remains unexamined. The implementation of AIV gene surveys necessitates the establishment of criteria for optimal water bodies and specific sampling locations within them. Third, although our workflow effectively confirms the presence of the H5 gene, it lacks the ability to differentiate between HPAIV and low pathogenicity AIV (LPAIV). To elucidate its pathogenicity, the ideal approach would involve the direct sequencing of the HA cleavage site using AIV RNA obtained through our workflow.

Taken together, the novel workflow reported here offers an efficient and highly sensitive method for investigating AIVs in water bodies. The ability to prove the presence of the virus in samples by genetic testing without virus growth using embryonated chicken eggs or cultured cells could promise to improve biosafety in the handling of samples and eliminate the need for protection and training at the level required for handling infectious HPAIVs. This, in turn, could promote the spread of environmental surveillance of HPAIVs. The findings of this study will deepen our understanding of AIV ecology, improve risk assessments, and inform targeted interventions to mitigate the spread of HPAIV threats around the world. Furthermore, the adaptability of this workflow for detecting other waterborne pathogens highlights its potential contribution to a comprehensive One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health surveillance efforts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Ct values of recovered viral RNA against various amount of spiked H4N2 virus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., R.I. and Y.A.; methodology, T.K., Y.M., K.Y., R.I. and Y.A.; validation, T.K., Y.M. and Y.A.; investigation, T.K., Y.M. and Y.A.; resources, K.Y., H.M. and R.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K. and Y.A.; writing—review and editing, T.K., Y.M., K.Y., H.M., R.I. and Y.A.; visualization, T.K. and Y.A.; supervision, K.Y. and R.I.; project administration, Y.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AdvanSentinel Inc.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miho Kuroiwa and Miya Haruna, from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., for validating specific primers and probes against M and H5 genes.

Conflicts of Interest

T.K., R.I. and Y.A. are employees of Shionogi & Co., Ltd. T.K. and R. I. are the inventors of patents for QuikConc. K.Y. received research funding from AdvanSentinel Inc.

References

- Kenmoe, S.; Takuissu, G.R.; Ebogo-Belobo, J.T.; Kengne-Ndé, C.; Mbaga, D.S.; Bowo-Ngandji, A.; Ondigui Ndzie, J.L.; Kenfack-Momo, R.; Tchatchouang, S.; Lontuo Fogang, R.; et al. A Systematic Review of Influenza Virus in Water Environments across Human, Poultry, and Wild Bird Habitats. Water Res. X 2024, 22, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charostad, J.; Rezaei Zadeh Rukerd, M.; Mahmoudvand, S.; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A.; Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A Comprehensive Review of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1: An Imminent Threat at Doorstep. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC CDC A(H5N1) Bird Flu Response Update October 11, 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/h5n1-response-10112024.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Mellis, A.M.; Coyle, J.; Marshall, K.E.; Frutos, A.M.; Singleton, J.; Drehoff, C.; Merced-Morales, A.; Pagano, H.P.; Alade, R.O.; White, E.B.; et al. Serologic Evidence of Recent Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5) Virus among Dairy Workers - Michigan and Colorado, June-August 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC CDC Confirms First Severe Case of H5N1 Bird Flu in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/m1218-h5n1-flu.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Tisza, M.J.; Hanson, B.M.; Clark, J.R.; Wang, L.; Payne, K.; Ross, M.C.; Mena, K.D.; Gitter, A.; Javornik Cregeen, S.J.; Cormier, J.; et al. Sequencing-Based Detection of Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Wastewater in Ten Cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, M.K.; Duong, D.; Shelden, B.; Chan, E.M.G.; Chan-Herur, V.; Hilton, S.; Paulos, A.H.; Xu, X.-R.S.; Zulli, A.; White, B.J.; et al. Detection of Hemagglutinin H5 Influenza A Virus Sequence in Municipal Wastewater Solids at Wastewater Treatment Plants with Increases in Influenza A in Spring, 2024. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.G.; Yakhno, M.; Hinshaw, V.S.; Bean, W.J.; Murti, K.G. Intestinal Influenza: Replication and Characterization of Influenza Viruses in Ducks. Virology 1978, 84, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Evidence for Water-Borne Transmission of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 896469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, D.; Jahangir, A.; Ruenphet, S.; Takehara, K. Persistence of Avian Influenza Viruses in Various Artificially Frozen Environmental Water Types. Influenza Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 912326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroita, T.; Iwamoto, R.; Wu, Q.; Minamoto, T. QuickConc: A Rapid, Efficient, and Power-Free EDNA Concentration Method with Cationic-Assisted Capture. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Adachi Katayama, Y.; Hayase, S.; Ando, Y.; Kuroita, T.; Okada, K.; Iwamoto, R.; Yanagimoto, T.; Kitajima, M.; Masago, Y. COPMAN: A Novel High-Throughput and Highly Sensitive Method to Detect Viral Nucleic Acids Including SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikawa, G.; Fujii, Y.; Abe, M.; Mai, N.T.; Mitoma, S.; Notsu, K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Elhanafy, E.; Daous, H.E.; Kabali, E.; et al. Meteorological Factors Affecting the Risk of Transmission of HPAI in Miyazaki, Japan. Vet. Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, T.; Taguchi, J.; Yamagishi, S.; Doi, H.; Ogata, S.; Yamanaka, H.; Minamoto, T. Suppression of Environmental DNA Degradation in Water Samples Associated with Different Storage Temperature and Period Using Benzalkonium Chloride. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2020, 18, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, W.; Makino, R.; Nagao, K.; Mekata, H.; Tsukamoto, K. New Micro-Amount of Virion Enrichment Technique (MiVET) to Detect Influenza A Virus in the Duck Faeces. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.; Kojima, I.; Fukunaga, W.; Okajima, M.; Mitarai, S.; Fujimoto, Y.; Matsui, T.; Kuwahara, M.; Masatani, T.; Okuya, K.; et al. Improved Method for Avian Influenza Virus Isolation from Environmental Water Samples. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e2889–e2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovas, C.I.; Papanastassopoulou, M.; Georgiadis, M.P.; Chatzinasiou, E.; Maliogka, V.I.; Georgiades, G.K. Detection and Quantification of Infectious Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus in Environmental Water by Using Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Ji, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; Dai, H.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Diversity of Genotypes and Pathogenicity of H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus Derived from Wild Bird and Domestic Poultry. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1402235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, K.E.; Ahrens, A.K.; Ali, A.; El-Kady, M.F.; Hafez, H.M.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Beer, M.; Harder, T. Improved Subtyping of Avian Influenza Viruses Using an RT-QPCR-Based Low Density Array: “Riems Influenza a Typing Array”, Version 2 (RITA-2). Viruses 2022, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakauchi, M.; Yasui, Y.; Miyoshi, T.; Minagawa, H.; Tanaka, T.; Tashiro, M.; Kageyama, T. One-Step Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assays for Detecting and Subtyping Pandemic Influenza A/H1N1 2009, Seasonal Influenza A/H1N1, and Seasonal Influenza A/H3N2 Viruses. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 171, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deboosere, N.; Horm, S.V.; Pinon, A.; Gachet, J.; Coldefy, C.; Buchy, P.; Vialette, M. Development and Validation of a Concentration Method for the Detection of Influenza A Viruses from Large Volumes of Surface Water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3802–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, L.E.; Givens, C.E.; Stelzer, E.A.; Killian, M.L.; Kolpin, D.W.; Szablewski, C.M.; Poulson, R.L. Environmental Surveillance and Detection of Infectious Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus in Iowa Wetlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023, 10, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).