1. Introduction

Hearing impairment is a condition that is increasingly common with age (Nieman and Oh, 2020). According to the World Health Organization in 2021, more than 1.5 billion people worldwide suffered from hearing impairment (WHO, 2021). By 2050, this number could rise to 2.5 billion (WHO, 2021). Hearing impairment can adversely affect an individual in many ways, such as reduced quality of life, limited employment opportunities, and increased risk of cognitive decline, dementia, loneliness, isolation, and depression (Collaborators, 2021). Identified risk factors associated with hearing impairment include age, genetic factors, noise exposure, modifiable lifestyle (e.g., smoking, and diet), and chronic diseases (e.g., obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease) (WHO, 2021). Importantly, many of the risk factors for hearing impairment are preventable, and altering modifiable risk factors can change the course of an individual's hearing trajectory and affect the extent of hearing impairment in later life (WHO, 2021). Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors to prevent hearing impairment is of great importance.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been reported to be associated with hearing impairment or sensorineural hearing loss in several previous observational studies (Aarhus et al., 2023; Bayat et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2021). The pathology of COPD is characterized by airway obstruction that is incompletely reversible, usually progressive, and associated with inflammation (Postma et al., 2015). Hypoxemia and chronic systemic inflammation have been hypothesized as underlying mechanisms in the association of COPD with hearing impairment (Aarhus et al., 2023; Bayat et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2021). However, causality remains uncertain, as the association between COPD and hearing impairment may be influenced by residual confounding or reverse causal association. In addition, there is a lack of studies investigating the association between lung function and hearing impairment. Given that the decline in lung function in adults may be preventable in some cases (Shrestha et al., 2023), establishing a causal association between lung function and hearing impairment may be important in preventing hearing impairment.

Compared to conventional observational studies, Mendelian randomization (MR) studies may provide more reliable evidence of causal relationships between lung function and COPD with hearing impairment. MR uses genetic variation as the instrumental variable (IV) for exposure to provide evidence of causal relationships between modifiable risk factors and diseases (Davies et al., 2018). The alleles of genetic variation are randomly assigned to sperm or egg cells during human gametogenesis, independently of potentially confounding environmental exposures (Sekula et al., 2016; Skrivankova et al., 2021). Additionally, the genetic variation is fixed in nature, which ensures a lifetime of exposure and mitigates concerns about reverse causality (Sekula et al., 2016). Therefore, MR can reduce the potential biases caused by confounding and reverse causality (Skrivankova et al., 2021).

This study aimed to investigate the associations of lung function and COPD with hearing impairment using large cross-sectional data from the UK Biobank cohort. In addition, two-sample MR was used to confirm potential causal associations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

The UK Biobank is a national prospective cohort that enrolled over half a million participants aged 40 to 69 years from 22 assessment centers across the UK between 2006 and 2010. This cohort was designed to study lifestyle, genetic, and environmental factors contributing to various diseases in middle and old age. A wide range of information was collected from participants, including questionnaires, physical measurements, biological samples, imaging, and follow-up on a variety of health-related outcomes. More details about the UK Biobank cohort are given elsewhere (Sudlow et al., 2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and ethical approval for UK Biobank was granted by the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

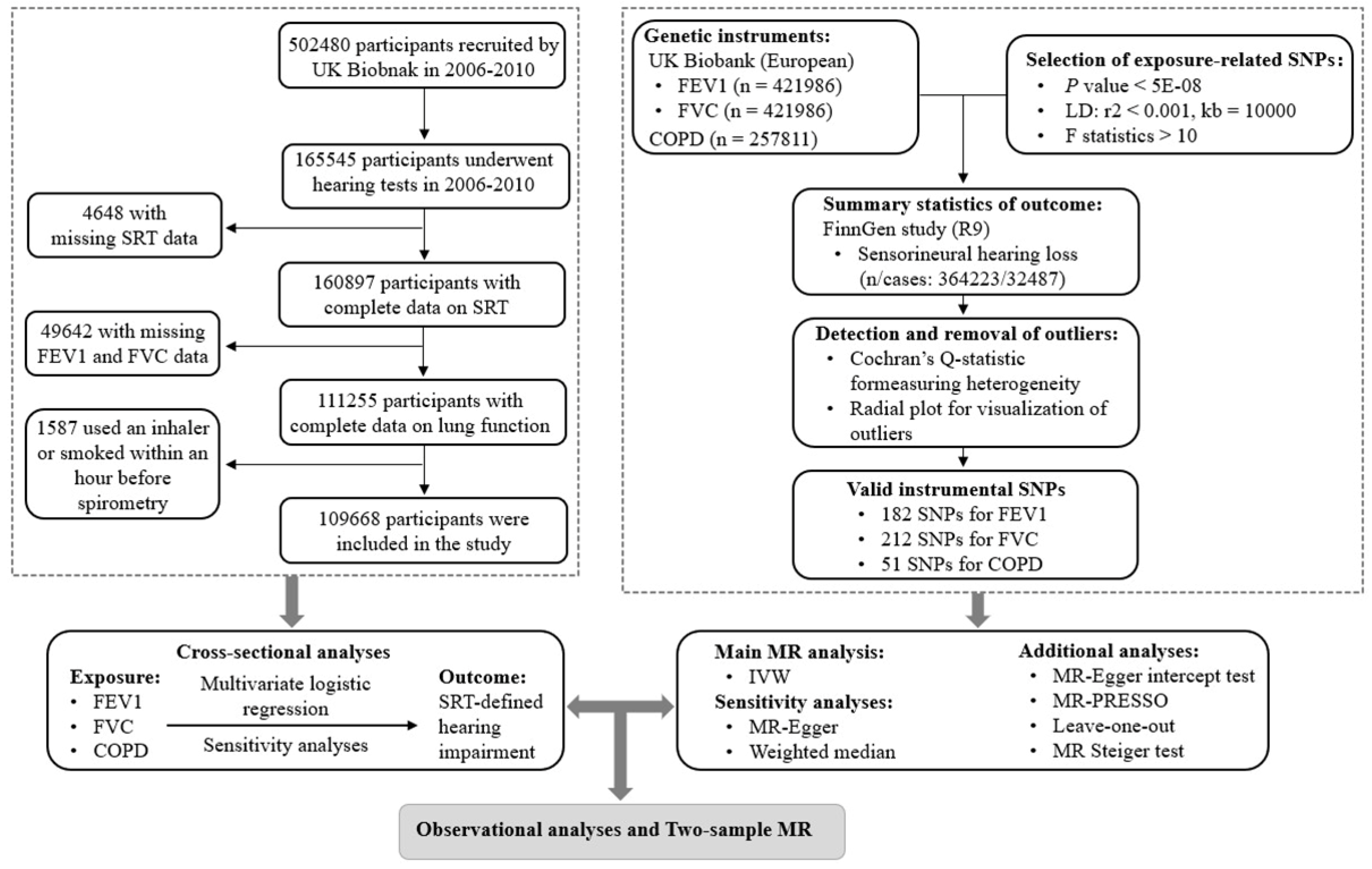

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the study participants. There were 165,545 participants in the UK Biobank cohort who underwent a hearing test at baseline. After excluding missing data for hearing tests (n = 4,648) and lung function (n = 49,642), followed by further exclusion of participants who smoked or used an inhaler within one hour before the spirometry (n = 1,587), a total of 109,668 white participants were included in the cross-sectional analyses.

2.2. Spirometry and Definition of COPD

At the 5th station of the assessment center visit of the UK Biobank, pre-bronchodilator spirometry (Vitalograph Pneumotrac 6800) was performed. Two to three breaths were recorded for each participant for approximately six minutes, with each blow lasting at least six seconds. The reproducibility of the first two blows was compared by computer. If the difference in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) was less than 5%, it was considered acceptable, indicating that a third blow was not required. The highest FVC and FEV1 values were used in this study.

According to the definition of COPD used in a previous study (Doiron et al., 2019), participants were defined as having COPD if the FEV1/FVC ratio was less than the lower limit of normal (LLN) calculated based on age, sex, race (Caucasian) and height using the Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 equations (Quanjer et al., 2012). In the sensitivity analysis, COPD was defined as the FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.7.

2.3. Definition of Hearing Impairment

A digit triplet test (DTT) was used for hearing tests in the UK Biobank. Fifteen sets of monosyllabic English digits were presented to the participants over background noise. An increase in the level of subsequent background noise would follow if participants correctly identified the triplet and a decrease if they did not. The signal-to-noise ratio with half of the speech delivered correctly understood was used to define the speech recognition threshold (SRT). The range of the SRT was from -12 to +8 dB, with the lower values representing better hearing ability. Using cut-off points established in a previous study (Dawes et al., 2014), participants in this study were divided into two groups based on the better ear: normal hearing (SRT < -5.5 dB) and hearing impairment (SRT ≥ -5.5 dB).

2.4. Covariates

A series of covariates (potential confounders) were used in this study according to previous studies. Covariates are described in more detail in Supplemental Text 1.

2.5. Data Sources and Genetic Instruments for MR Analyses

The two-sample MR using genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics was performed to estimate the causal effects of lung function and COPD (exposure) on sensorineural hearing loss (outcome).

Figure 1 outlines the study design for the two-sample MR. Valid genetic IVs in MR studies satisfy three key assumptions: (1) relevance: the IVs are strongly associated with the exposure; (2) independence: the IVs are not associated with confounding factors in the link between exposure and outcome; and (3) exclusion restriction: the IVs are exclusively associated with the outcome because of their effect on the exposure (Davies et al., 2018).

Details of the GWAS summary statistics were provided in

Table S1, with no overlap in the sample population for exposure and outcome. All GWAS summary data used in this study had received participants' informed consent and ethical approval in the original study. Details of the data sources and selection of genetic instruments were provided in the Supplemental Text 2.

Outliers were detected using radial plots and excluded before the primary MR analyses (

Figures S1–S3). The advantage of radial plots is that they improve the visual detection of influential data points and outliers (Bowden et al., 2018). As a result, 182 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with FVE1, 212 SNPs associated with FVC, and 51 SNPs associated with COPD were used for the MR analyses. More information on these SNPs was provided in

Tables S2–S4.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Details of statistical analyses were provided in the Supplemental Text 3.

2.6.1. Cross-Sectional Analyses

The associations of lung function and COPD with the risk of hearing impairment were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression models, with the results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

2.6.2. Two-Sample MR

In the primary MR analyses, an inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was used as the main method to assess the potential causal effects of lung function and COPD on hearing impairment (i.e., sensorineural hearing loss). If all IVs are valid, IVW yields the most precise estimate. MR-Egger regression and weighted median were used as sensitivity analyses.

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software R (version 4.2.3). The R packages TwoSampleMR, RadialMR, and MRPRESSO were used for the MR analyses. Two-sided P values below 0.05 were used as the statistical significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Associations of Lung Function and COPD with Hearing Impairment in UK Biobank

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the study population. A total of 109,668 participants were included in the cross-sectional analyses, including 10,900 (9.9%) participants with SRT-defined hearing impairment and 98,768 (90.1%) participants with normal hearing. The median (interquartile range) age was 58.00 (12.00) years, and 58,994 (53.8%) participants were female. Participants with hearing impairment were older, more likely to be male, and of lower socioeconomic status than those with normal hearing.

Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression analyses. After adjustment for potential confounders, lung function was associated with a reduced risk of hearing impairment, with ORs (95% CIs) for each interquartile range increase in FEV1 and FVC of 0.80 (0.77, 0.84) and 0.80 (0.76, 0.83), respectively. Results stratified by age and sex displayed similar associations (

P for interactions > 0.05) (

Table S5). Compared to participants without COPD, those with COPD (FEV1/FVC < LLN) had an increased risk of hearing impairment, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.10 (1.02, 1.18) (

Table 2). This significant association was observed in participants aged 60 years or older, but not in those under 60 years (

P for interaction > 0.05) (

Table S5). Besides, the association between COPD (FEV1/FVC < LLN) and increased risk of hearing impairment was observed in both men and women, but without statistical significance (

P for interaction > 0.05) (

Table S5).

In the sensitivity analysis, a similar result were observed for COPD, which was defined as an FEV/FVC ratio below 0.7 (

Table S6). In the restricted cubic spline models, the associations of FEV1 and FVC with hearing impairment were linear (

P for nonlinear > 0.05) (

Figure S4 and S5). When self-reported hearing difficulty was treated as a secondary outcome, the results for FEV1 and FVC remained significant, but no significant association was observed for COPD (

Tables S7 and S8).

3.2. Results for MR Analyses

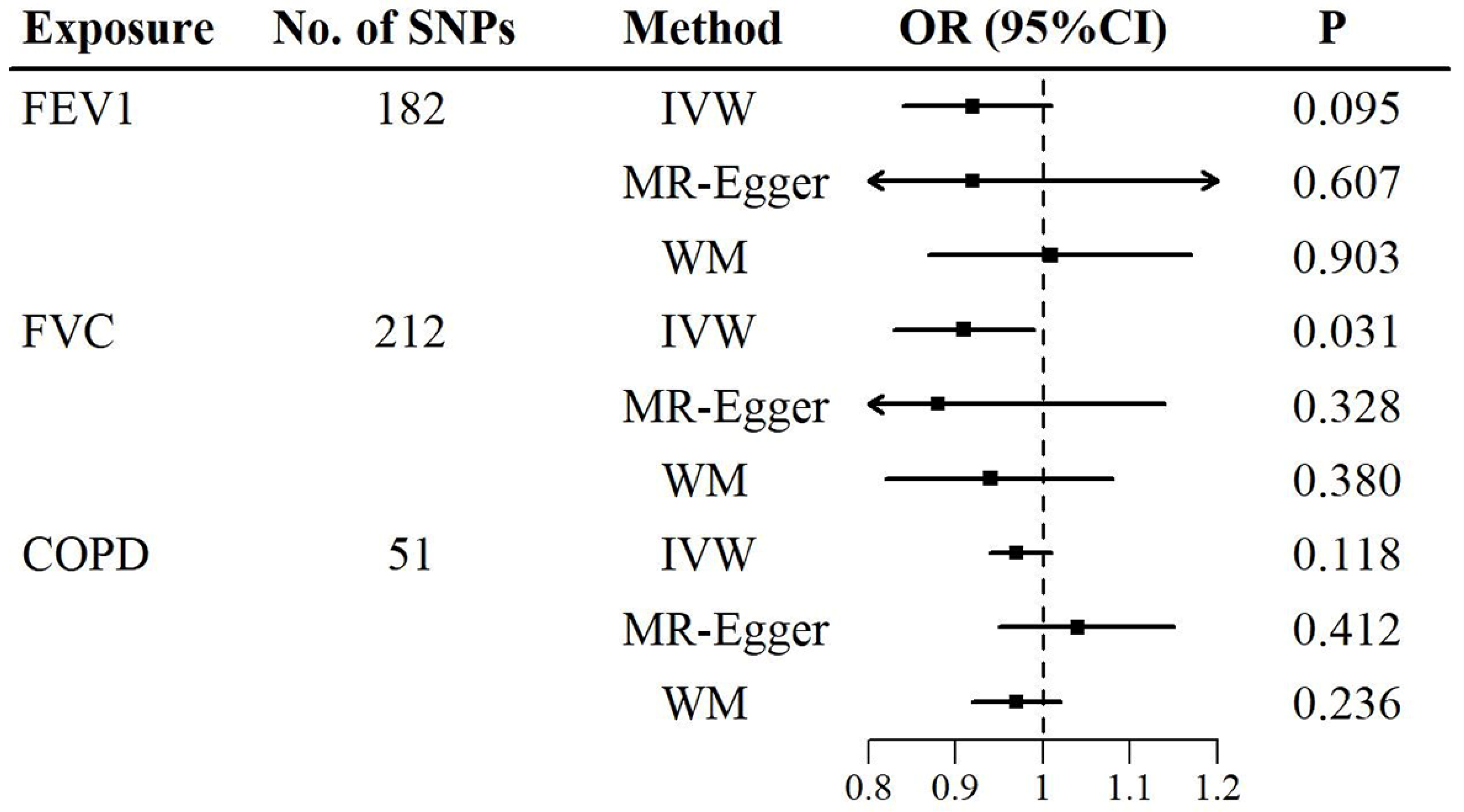

The causal associations of lung function and COPD with sensorineural hearing loss were determined using the two-sample MR (

Figure 2,

Tables S9 and S10). In the primary MR analyses (outliers were excluded), the IVW method showed a negative association between FVC and sensorineural hearing loss, with an OR (95% CI) of 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) per standard deviation increase in FVC (

Figure 2 and

Table S9). In the sensitivity analyses, the MR-Egger and weighted median methods were similar to the IVW method in direction and magnitude, with ORs (95% CIs) of 0.88 (0.68, 1.14) and 0.94 (0.82, 1.08) per standard deviation increase in FVC, respectively (

Figure 2 and

Table S9). However, no significant causal association was found between FEV1 and sensorineural hearing loss in either the IVW method or the sensitivity analyses (

Figure 2 and

Table S9). For COPD, there was also no evidence of a causal association (

Figure 2 and

Table S9).

The Cochran's Q statistic, scatter plots, and funnel plots suggested that no substantial heterogeneity was found in the primary MR analyses (

Table S11 and Figures S6). No evidence of horizontal pleiotropy was shown in the MR-Egger intercept or Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) test (

Tables S12 and S13). The leave-one-out plot showed that the estimate of the overall significance of FVC was not driven by any single SNP (

Figure S12). The results of the MR Steiger test did not support the reverse causal association between FVC and sensorineural hearing loss (

Table S14).

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional analyses of 109,668 middle-aged and older adults in the UK Biobank cohort, better lung function (including FEV1 and FVC) was associated with a reduced risk of hearing impairment, and this association showed a linear dose-response relationship. COPD was positively associated with hearing impairment. In addition, the primary MR analysis (IVW) found a significant negative association between FVC and sensorineural hearing loss, which was robust to sensitivity analyses, heterogeneity, and pleiotropy tests, indicating a potential protective effect. For FEV1 and COPD, however, there were no significant associations with sensorineural hearing loss in the MR analyses.

At present, data on the association between lung function and hearing impairment are lacking. In this study, the observational and primary MR analyses yielded consistent results of a significant negative association between FVC and hearing impairment, while no statistical significance was shown for FEV1 in the MR analyses. These findings suggested that FEV1 and FVC might differ in their associations with hearing impairment. The most common measures used in spirometry are FEV1 and FVC, which reflect different assessments of lung function (Au Yeung et al., 2018; Obeidat et al., 2015). FEV1 is used to measure airway obstruction, while FVC measures total lung capacity (Nowak, 2018). Age, gender, race, height, and smoking history were the most important predictors of lung function, with height highly linked with FVC and smoking history strongly associated with FEV1 (Au Yeung et al., 2018; Nowak, 2018). Therefore, one possible explanation for the discrepancy in the results could be a spurious association between FEV1 and hearing impairment due to residual confounding in observational studies that lacked complete information on the number, frequency, intensity, and cessation of smoking over the life course. In contrast, MR studies are based on the principle that genotypes in a population are generally independent of confounders, making the results less affected by confounding and providing more reliable evidence when MR assumptions are adequately met (Davies et al., 2018; Sekula et al., 2016; Skrivankova et al., 2021). For FVC instead of FEV1, similar magnitudes and consistent directions were estimated by the IVW, MR-Egger, and weighted median methods. This suggested a potential protective effect of FVC on hearing impairment.

Although many observational studies have found that impaired lung function (including FEV1 and FVC) is associated with mortality and multiple adverse health outcomes, FVC appears to be the more relevant determinant (Agustí et al., 2017; Godfrey and Jankowich, 2016; Guerra et al., 2017; Higbee et al., 2021; Melén et al., 2024). Even without chronic lung disease, the reduced FVC, a sign of lung function restriction, was a strong predictor of mortality (Burney and Hooper, 2011; Portas et al., 2020). Only FVC was still strongly associated with mortality when FEV1 and FVC were further adjusted for each other in the model (Burney and Hooper, 2011). Another study revealed true lung restriction in people who had only a low FVC trajectory (restrictive pattern only), with a risk of multiple diseases by middle age (Dharmage et al., 2023). Similarly, compared to the obstructive pattern (reduced FEV1/FVC), the restrictive pattern of impaired lung function (reduced percent predicted FVC) was a stronger predictor of incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease (Sumida et al., 2017). These were further supported by a recent MR study in which reduced FVC had an independent causal association with coronary artery disease (Higbee et al., 2021). Conversely, there was little evidence to support a causal link between FEV1 and the risk of cardiovascular disease (Higbee et al., 2021). In line with previous studies, this study found a causal association of FVC (rather than FEV1) with hearing impairment.

On the other hand, the underlying mechanism of the association between FVC and hearing impairment could possibly be explained by the independent and stronger association of FVC with multiple diseases (Ramalho and Shah, 2021), such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, which have been linked to hearing impairment (WHO, 2021). Furthermore, there is growing evidence that impaired lung function in adults may be due in part to poor growth and development and associated with various risk factors throughout the life course, such as maternal smoking, prematurity, low birth weight, physical inactivity, early smoking, or exposure to air pollution (Melén et al., 2024; Portas et al., 2020). As suggested by the restrictive-only pattern, poor lung development seemed to be linked to underdevelopment of other organ systems and subsequent multiple morbidities (Dharmage et al., 2023). This implied that a causal association between FVC and hearing impairment might involve common pathophysiological pathways. Mechanistically, the causal association between FVC and hearing impairment could be explained by hypoxia and chronic systemic inflammation. Specifically, impaired lung function may lead to hypoxia (Qian et al., 2024), triggering chronic systemic inflammation (Eltzschig and Carmeliet, 2011), thereby directly or indirectly resulting in hearing impairment (Kociszewska and Vlajkovic, 2022; Wong et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2024). However, the specific mechanisms behind this causal association remained unknown and required additional research.

An association between COPD and hearing impairment has been reported in several previous observational studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients with COPD had significantly prolonged auditory brainstem response waves and significantly elevated pure tone audiometry than controls (Bayat et al., 2018). In another cross-sectional study based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, an independent association between COPD and sensorineural hearing loss was found after adjustment for many confounders (Sharma et al., 2021). Moreover, a large cohort study reported that COPD was associated with low- and mid-frequency hearing decline (Aarhus et al., 2023). By contrast, the MR analyses in this study did not show that genetically predicted COPD was associated with an increased risk of hearing impairment, suggesting that the significant associations reported in the observational studies might be due to residual confounding or inverse associations. However, since the use of a limited number of genetic IVs might not provide sufficient statistical power, a causal effect of COPD on hearing impairment could not be completely excluded. This may be clarified by obtaining more genetic IVs for COPD in the future.

A strength of this study was the large sample size. Another strength was that the MR analyses provided causal inference, with sensitivity analyses, heterogeneity, and pleiotropy tests showing no violation of assumptions. In addition, the reverse causality risk was reduced by the MR Steiger test.

However, this study also had several limitations. First, lung function generally varies with time (Sumida et al., 2017). More insight may be provided by further investigation of the longitudinal association between lung function trajectories and hearing impairment. Second, the definition of COPD should be based on post-bronchodilator spirometry, but only pre-bronchodilator spirometry was carried out in the UK Biobank. Third, although MR analyses of lung function were performed with a sufficient set of genetic IVs, the number of genetic IVs was relatively small for COPD, which may reduce statistical power. Fourth, the definition of outcome in the observational study was not consistent with that in the MR analyses. The former was based on SRT obtained from DTT in the UK Biobank, and the latter was based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (sensorineural hearing loss) in the FinnGen study. Notably, the DTT is a signal-to-noise ratio test that can overcome conduction loss by turning up the volume of the stimuli, as allowed for participants in the UK Biobank (Taylor et al., 2020). That is, DTT is a sensorineural hearing loss test that detects hearing impairment with a cochlear origin only (Taylor et al., 2020). Finally, the study population was predominantly European ancestry, which limited the generalization of our results.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a linear negative association was found between FVC and hearing impairment in middle-aged and older adults in the UK Biobank. In addition, MR analyses confirmed a causal effect of FVC on hearing impairment, but not FEV1 and COPD. Given that spirometry is a non-invasive, simple, and reproducible method, early, especially in key age windows such as childhood and adolescence (Melén et al., 2024), and regular testing of lung function can help identify individuals at risk of hearing impairment, allowing for timely interventions and optimal management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lanlai Yuan, Ge Yin, Mengwen Shi , Aximu Nadida, Yaohua Tian and Yu Sun; Funding acquisition, Yu Sun; Methodology, Lanlai Yuan, Feipeng Cui, Ge Yin, Mengwen Shi , Aximu Nadida, Yaohua Tian and Yu Sun; Software, Lanlai Yuan and Feipeng Cui; Supervision, Yaohua Tian and Yu Sun; Visualization, Lanlai Yuan; Writing – original draft, Lanlai Yuan; Writing – review & editing, Lanlai Yuan, Feipeng Cui, Ge Yin, Mengwen Shi , Aximu Nadida, Yaohua Tian and Yu Sun.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82430035), the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of Hubei Province (No. 2023AFA038), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2021YFF0702303, 2023YFE0203200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071058), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2024BRA019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants and staff at UK Biobank. We would like to acknowledge the participants and investigators of the FinnGen study.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Ethics Statement: This research was conducted using UK Biobank resources (application number 69741). The ethical approval of the UK Biobank was from the North West Multi-center Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 16/NW/0274). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All GWAS summary data used in this study had received participants' informed consent and ethical approval in the original study.

Abbreviations

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI: confidence interval; CSEs: certificate of secondary educations; DTT: digit triplet test; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; GWAS: genome-wide association study; GCSEs: general certificate of secondary educations; HND: higher national diploma; HNC: higher national certificate; IV: instrumental variable; IQR: interquartile range; IVW: inverse variance weighted; LLN: lower limit of normal; MR: Mendelian randomization; MR-PRESSO: Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier; NVQ: national vocational qualification; OR: odds ratio; SRT: speech recognition threshold; SD: standard deviation; TDI: Townsend deprivation index

References

- Aarhus, L.; Sand, M.; Engdahl, B. COPD and 20-year hearing decline: The HUNT cohort study. Respiratory medicine 2023, 212, 107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustí, A.; Noell, G.; Brugada, J.; Faner, R. Lung function in early adulthood and health in later life: a transgenerational cohort analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2017, 5, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au Yeung, S.L.; Borges, M.C.; Lawlor, D.A. Association of Genetic Instrumental Variables for Lung Function on Coronary Artery Disease Risk: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Circulation. Genomic and precision medicine 2018, 11, e001952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, A.; Saki, N.; Nikakhlagh, S.; Mirmomeni, G.; Raji, H.; Soleimani, H.; Rahim, F. Is COPD associated with alterations in hearing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2018, 14, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Spiller, W.; Del Greco, M.F.; Sheehan, N.; Thompson, J.; Minelli, C.; Davey Smith, G. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the Radial plot and Radial regression. International journal of epidemiology 2018, 47, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burney, P.G.; Hooper, R. Forced vital capacity, airway obstruction and survival in a general population sample from the USA. Thorax 2011, 66, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, G.B.D.H.L. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990-2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.M.; Holmes, M.V.; Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 2018, 362, k601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Fortnum, H.; Moore, D.R.; Emsley, R.; Norman, P.; Cruickshanks, K.; Davis, A.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; McCormack, A.; Lutman, M. Hearing in middle age: a population snapshot of 40–69 year olds in the UK. Ear and hearing 2014, 35, e44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmage, S.C.; Bui, D.S.; Walters, E.H.; Lowe, A.J.; Thompson, B.; Bowatte, G.; Thomas, P.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Jarvis, D.; Hamilton, G.S.; Johns, D.P.; Frith, P.; Senaratna, C.V.; Idrose, N.S.; Wood-Baker, R.R.; Hopper, J.; Gurrin, L.; Erbas, B.; Washko, G.R.; Faner, R.; Agusti, A.; Abramson, M.J.; Lodge, C.J.; Perret, J.L. Lifetime spirometry patterns of obstruction and restriction, and their risk factors and outcomes: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2023, 11, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Fortier, I.; Cai, Y.; De Matteis, S.; Hansell, A.L. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. The European respiratory journal 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, M.S.; Jankowich, M.D. The Vital Capacity Is Vital: Epidemiology and Clinical Significance of the Restrictive Spirometry Pattern. Chest 2016, 149, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, S.; Carsin, A.E.; Keidel, D.; Sunyer, J.; Leynaert, B.; Janson, C.; Jarvis, D.; Stolz, D.; Rothe, T.; Pons, M.; Turk, A.; Anto, J.M.; Probst-Hensch, N. Health-related quality of life and risk factors associated with spirometric restriction. The European respiratory journal 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, D.H.; Granell, R.; Sanderson, E.; Davey Smith, G.; Dodd, J.W. Lung function and cardiovascular disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. The European respiratory journal 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewska, D.; Vlajkovic, S. Age-Related Hearing Loss: The Link between Inflammaging, Immunosenescence, and Gut Dysbiosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melén, E.; Faner, R.; Allinson, J.P.; Bui, D.; Bush, A.; Custovic, A.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Guerra, S.; Breyer-Kohansal, R.; Hallberg, J.; Lahousse, L.; Martinez, F.D.; Merid, S.K.; Powell, P.; Pinnock, H.; Stanojevic, S.; Vanfleteren, L.; Wang, G.; Dharmage, S.C.; Wedzicha, J.; Agusti, A. Lung-function trajectories: relevance and implementation in clinical practice. Lancet 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nieman, C.L.; Oh, E.S. Hearing Loss. Ann Intern Med 2020, 173, ITC81–ITC96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, C. Lung Function and Coronary Artery Disease Risk. Circulation. Genomic and precision medicine 2018, 11, e002137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, M.; Hao, K.; Bossé, Y.; Nickle, D.C.; Nie, Y.; Postma, D.S.; Laviolette, M.; Sandford, A.J.; Daley, D.D.; Hogg, J.C.; Elliott, W.M.; Fishbane, N.; Timens, W.; Hysi, P.G.; Kaprio, J.; Wilson, J.F.; Hui, J.; Rawal, R.; Schulz, H.; Stubbe, B.; Hayward, C.; Polasek, O.; Järvelin, M.R.; Zhao, J.H.; Jarvis, D.; Kähönen, M.; Franceschini, N.; North, K.E.; Loth, D.W.; Brusselle, G.G.; Smith, A.V.; Gudnason, V.; Bartz, T.M.; Wilk, J.B.; O'Connor, G.T.; Cassano, P.A.; Tang, W.; Wain, L.V.; Soler Artigas, M.; Gharib, S.A.; Strachan, D.P.; Sin, D.D.; Tobin, M.D.; London, S.J.; Hall, I.P. ; Paré; PD. Molecular mechanisms underlying variations in lung function: a systems genetics analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2015, 3, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portas, L.; Pereira, M.; Shaheen, S.O.; Wyss, A.B.; London, S.J.; Burney, P.G.J.; Hind, M.; Dean, C.H.; Minelli, C. Lung Development Genes and Adult Lung Function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020, 202, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, D.S.; Bush, A.; van den Berge, M. Risk factors and early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2015, 385, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Li, W.; Zhou, J.; Xie, S. RNA modifications in pulmonary diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.; Zheng, J.; Stocks, J. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. The European respiratory journal 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, S.H.R.; Shah, A.M. Lung function and cardiovascular disease: A link. Trends in cardiovascular medicine 2021, 31, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, P.; Del Greco, M.F.; Pattaro, C.; Köttgen, A. Mendelian Randomization as an Approach to Assess Causality Using Observational Data. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2016, 27, 3253–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Chern, A.; Begasse de Dhaem, O.; Golub, J.S.; Lalwani, A.K. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is a Risk Factor for Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A US Population Study. Otol Neurotol 2021, 42, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Zhu, X.; London, S.J.; Sullivan, K.J.; Lutsey, P.L.; Windham, B.G.; Griswold, M.E.; Mosley, T.H., Jr. Association of Lung Function With Cognitive Decline and Incident Dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. American journal of epidemiology 2023, 192, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrivankova, V.W.; Richmond, R.C.; Woolf, B.A.R.; Davies, N.M.; Swanson, S.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Timpson, N.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Dimou, N.; Langenberg, C.; Loder, E.W.; Golub, R.M.; Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Richards, J.B. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2021, 375, n2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudlow, C.; Gallacher, J.; Allen, N.; Beral, V.; Burton, P.; Danesh, J.; Downey, P.; Elliott, P.; Green, J.; Landray, M.; Liu, B.; Matthews, P.; Ong, G.; Pell, J.; Silman, A.; Young, A.; Sprosen, T.; Peakman, T.; Collins, R. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine 2015, 12, e1001779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumida, K.; Kwak, L.; Grams, M.E.; Yamagata, K.; Punjabi, N.M.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Coresh, J.; Matsushita, K. Lung Function and Incident Kidney Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2017, 70, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.; Shryane, N.; Kapadia, D.; Dawes, P.; Norman, P. Understanding ethnic inequalities in hearing health in the UK: a cross-sectional study of the link between language proficiency and performance on the Digit Triplet Test. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO World report on hearing. Geneva: World Health Organization 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/339913.

- Wong, E.; Yang, B.; Du, L.; Ho, W.H.; Lau, C.; Ke, Y.; Chan, Y.S.; Yung, W.H.; Wu, E.X. The multi-level impact of chronic intermittent hypoxia on central auditory processing. NeuroImage 2017, 156, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Miao, Z.; Chai, R.; Chen, W. Development of Chinese herbal medicine for sensorineural hearing loss. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B 2024, 14, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).