1. Introduction

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) is a common thoracic disease affecting young adults, having an estimated annual incidence of 7.4 per 100,000 in males and 1.2 per 100,000 in females [

1,

2]. This condition is of significant concern due to its high recurrence rate after treatment, with reported rates ranging from 16% to 52% in several studies [

3]. The pooled 1-year and overall recurrence rates were 29.0% and 32.1%, respectively [

4]. Some reports even documented recurrence rates as high as 54.4% during a mean follow-up period of 54 months (42-62 months) [

5].

The surgical approach is the most effective treatment for PSP. The goals of surgery include resection of the portion of the lung containing these ruptured or/and unruptured bullae (bullectomy) and achieving mechanical pleurodesis to further decrease the risk of pneumothorax recurrence. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for the treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax was first reported by Levi et al. (1990) [

6]. This method has been proven to be highly effective in treatment, minimizing recurrence rates comparable to open surgery and significantly more effective than conservative treatment (p < 0.001) [

7]. In addition to facilitating the management of bullae, VATS allows for effective mechanical pleurodesis, with the most widely adopted surgical techniques being pleural abrasion and apical pleurectomy [

8,

9]. However, the effectiveness and superiority of each pleurodesis technique remain debated, requiring further clinical data to clarify [

9]. This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes and document the association of several factors with the recurrence rate of pneumothorax in the treatment of PSP using VATS bullectomy and mechanical pleurodesis.

2. Study Population and Methodology

2.1. Study Population

This study included 118 patients with PSP who underwent VATS and mechanical pleurodesis at Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, and Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam, between January 2007 and June 2013, with a postoperative follow-up of 120 months.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Patients meeting the following criteria were included: Patients diagnosed with PSP according to the British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010 [

10]. Patients undergoing VATS to bullectomy and achieve pleurodesis using either pleurectomy or pleural abrasion.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, patients who declined to participate in the study, and patients with incomplete medical records were excluded.

2.4. Methodology

This was a descriptive longitudinal follow-up study.

Subjects were selected using convenience sampling.

2.5. Surgical Procedure for Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

2.5.1. Anesthesia: General Anesthesia with Double-Lumen Endotracheal Intubation

2.5.2. Patient Positioning and Surgical Team:

The patient was placed in a 90° lateral decubitus position with the affected lung side up.

The surgical team consisted of 3 members: The surgeon stood on the patient's right side, the assistant surgeon, and the scrub nurse stood on the opposite side.

2.5.3. Surgical Steps:

Step 1: Trocar insertion:

- -

The first trocar (10 mm or 12 mm) was inserted at the 7th or 8th intercostal space in the midaxillary line.

- -

Additional trocars were typically placed at the 5th intercostal space in the anterior axillary line (10 mm trocar) and below the tip of the scapula (5 mm trocar) under endoscopic visualization.

Step 2: Injury identification and assessment:

- -

The number and location of bullae were recorded.

- -

Air leak sites were identified by insufflating 500 to 1000 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride into the pleural space, immersing the lung parenchyma in the fluid, and gradually re-inflating the lung. The location of air bubbles indicated the leak site.

Step 3: Management of air leaks and bullae:

- -

The air leaks site and bullae were wedge-shaped and resected by endostaplers. The cutting line in the remaining lung tissue was at least 1 cm away from the lesion. If more than one stapler was required, they were placed contiguously to ensure a continuous suture line and prevent postoperative air leaks at the junctions.

- -

For small (<10 mm), localized bullae (<3 in number), endoscopic clipping and excision followed by single-strand suture closure could be performed (

Figure 1).

Step 4: Mechanical Pleurodesis: One of the following two methods was used:

- -

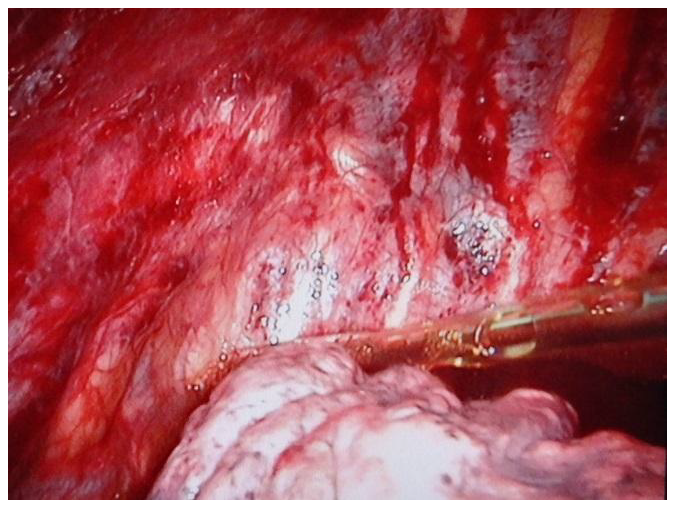

Pleural abrasion: The parietal pleura was scrubbed using an endoscopic suction tip across the entire parietal pleura from the apex to the 5

th intercostal space until petechial hemorrhage was observed (

Figure 2;

Figure 3). The anterior border of the abraded area was the internal mammary artery, and the posterior border was the paravertebral sulcus. After abrasion of the parietal pleura, 50 mL of 4% Iodopovidine solution was injected into the pleural cavity to enhance pleural adhesion.

- -

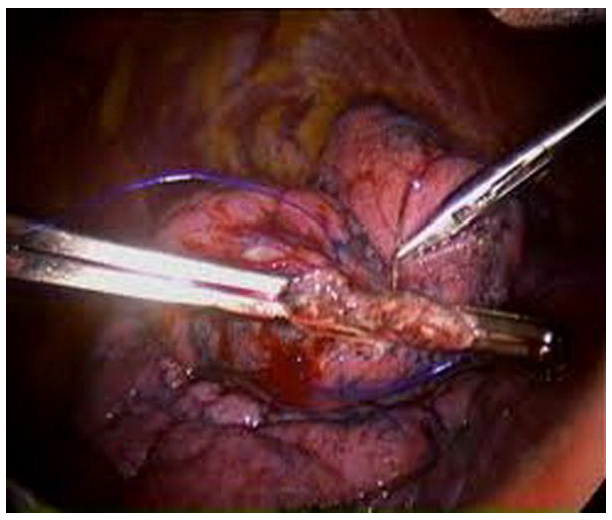

Pleurectomy (

Figure 4): The parietal pleura was dissected and resected from the apex down to the 5th intercostal space. The anterior border of the resected area was 1cm away from the internal mammary artery, and the posterior border was the intercostal muscles. Care was taken to preserve the subclavian vessels at the apex [

9].

Figure 2.

Pleural abrasion.

Figure 2.

Pleural abrasion.

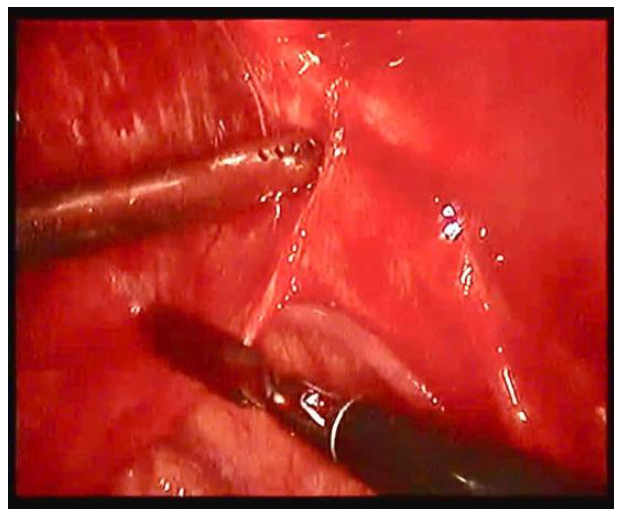

Figure 3.

Pleural abrasion.

Figure 3.

Pleural abrasion.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative view of pleurectomy in the right thoracic cavity.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative view of pleurectomy in the right thoracic cavity.

Step 5: End of surgery:

- -

All bleeding points were checked, and electrocautery was used for hemostasis. A 28Fr chest tube was inserted through the trocar site in the midaxillary line, with the tip placed superiorly near the apex and the tube body positioned along the paravertebral sulcus. The drainage tube was connected to a closed drainage system. The lung was gradually re-ventilated, and the presence of any residual air leaks was checked under camera visualization. Any remaining air leaks were addressed with additional sutures or electrocautery to ensure complete lung expansion and apposition of the visceral pleura to the chest wall.

- -

The chest drainage tube was secured, and the trocar insertion sites were closed with sutures.

2.5.4. Postoperative Care and Monitoring

- A closed, two-bottle drainage system was used for pleural drainage with a suction pressure of -10 to -20 cm H2O. The drainage fluid was assessed and recorded every 24 hr for quantity and characteristics. Postoperative pain management included intravenous paracetamol 1 gram every 8 hr for the first 24 hr. On the second day, the dose was reduced to 0.5 grams orally every 8 hr, with gradual dose reduction in the following days.

The chest tube was removed when there was no further air leakage for 24 hr, the drainage volume was less than 200 mL in 24 hr, the fluid was serosanguineous, and a chest X-ray showed full lung expansion.

- Patients were followed up regularly after discharge at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months in subsequent years postoperatively. The follow-up was concluded at 10 years from the date of surgery.

Pulmonary function tests (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC) were performed on patients presenting for direct examination at the hospital (results were assessed based on normal values for Vietnamese individuals: FEV1 ≥ 80%, FVC ≥ 80%, FEV1/FVC ≥ 70%).

2.5.5. Study Parameters

- Description of the general characteristics of the study group: age; gender; Body Mass Index (BMI); smoking habits; history of pneumothorax (yes/no); treatment before VATS (oxygen therapy/chest tube insertion); imaging findings on chest X-ray and CT scan (pneumothorax, bullae).

- Description of the indications, techniques for managing air leaks and bullae, and methods of pleurodesis.

- Assessment of early postoperative outcomes and the incidence of ipsilateral pneumothorax recurrence: surgical time; intraoperative blood loss; volume of pleural drainage on postoperative days 1 and 2; duration of chest tube drainage; postoperative complications; pain scale assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) on postoperative day 3; number of patients with ipsilateral pleural pneumothorax recurrence during the 120-month follow-up period.

Recurrence was defined as a further pneumothorax occurring more than 30 days after the end of treatment in patients who had achieved full lung expansion following initial pneumothorax [

5].

2.6. Data Analysis

The research records were standardized, and the collected variables were coded, then entered into a database and analyzed using SPSS 20.0 statistical software.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test. Categorical and ordinal variables are presented as percentages. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square (χ2) tests and Fisher's exact tests when cell sizes were less than five. Results were considered statistically significant at a P value <0.05.

3. Results

From January 2007 to August 2013, 118 patients who underwent VATS for PSP were enrolled in the study. This included 39 patients who underwent surgery from January 2007 to September 2010 and received pleurectomy and 79 patients who underwent surgery from October 2010 to June 2013 and received pleural abrasion. A total of 115 patients were followed up for a complete duration of 120 months post-surgery, including 38 patients in the pleurectomy group and 77 patients in the pleural abrasion group.

The age group under 40 years old accounted for the majority of cases, with a rate of 82.2%. Males were predominant, with a male-to-female ratio of 6.4:1. The indication for VATS in patients with spontaneous recurrent pneumothorax was high (70.3%). Among the 83 patients with spontaneous recurrent pneumothorax, 62 patients had a history of one episode of pneumothorax (74.7%), 15 patients had two episodes (18.1%), and 6 patients had three or more episodes (7.0%); patients with a first episode accounted for 29.7%. The majority of patients (92.4%) underwent chest tube placement for drainage and decompression before undergoing VATS. All patients had pneumothorax on chest X-ray and CT scan. The chest CT scan was superior in detecting bullae on both the affected and the contralateral side (

Table 1).

Recurrent pneumothorax and prolonged air leak after drainage were the surgical indications, with rates of 70.3% and 29.7%, respectively. The majority of cases were managed with a stapler (61.2%). The predominant pleurodesis technique was pleural abrasion (66.9%) (

Table 2).

Pleurectomy had a longer surgical time, greater intraoperative blood loss, and less drainage compared to the pleural abrasion group (p < 0.05). The postoperative pleural drainage duration was not statistically different between the two groups (p > 0.05) (

Table 3).

Pain level on postoperative day 3 was significantly lower in the pleural abrasion group compared to the pleurectomy group (p < 0.001). Postoperative complications included hemothorax (3.4%) and prolonged air leak > 5 days (4.2%). There was no significant difference in complication rates between the pleurectomy and pleural abrasion groups (p > 0.05) (

Table 4).

Mean respiratory function indices were all within normal limits at the recorded time points. Differences in mean respiratory function indices between the 3-6 month and >6 month - 1-year measurements were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (

Table 5).

115 patients were followed up for a full 120 months after surgery. In the pleural abrasion group, 3 patients had ipsilateral pneumothorax recurrence (3.89%) at 2 months, 8 years, and 10 years postoperatively. The patient with recurrence at 2 months had a small pneumothorax treated with oxygen therapy for 5 days. The other two patients underwent repeat VATS for suture repair of air leaks, bullectomy, and pleural abrasion. No recurrence was recorded in the pleurectomy group (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

Sadikot et al. (1997) studied 197 patients with spontaneous pneumothorax, of which PSP accounted for 77.66%. Most patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax had underlying obstructive airway disease, asthma, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The age ranged from 15 to 95 years, with a relatively high mean age of 36.8 ± 17.4 [

5]. Sawada S. (2005) studied 281 patients with PSP, with a male-to-female ratio of 9.8:1 (255 males and 26 females) and a mean age of 29.1 ± 13.6 (range 5 to 79 years) [

7]. These results are similar to our study, with a mean patient age of 28.2 ± 10.2 (16-55) and a male-to-female ratio of 6.4:1. However, some studies on spontaneous pneumothorax have been conducted exclusively in patients under 40 years of age [

9].

Recurrent pneumothorax is the most concerning issue in evaluating the effectiveness of a treatment method for spontaneous pneumothorax. Sadikot et al. (1997) reported recurrence rates as high as 54.2% in patients with spontaneous pneumothorax treated with minimally invasive methods (oxygen therapy, aspiration, or chest tube insertion). In the subgroup of patients who underwent chest tube insertion at the outset without prior air aspiration, the recurrence rate was 53.8%. Recurrence rates at 1 year, 2 years, and 4 years after drainage were 26.14%, 13.72%, and 14.38%, respectively [

5]. Similar results were obtained from a pooled analysis of 29 studies by Walker et al. (2018), which showed pooled 1-year and overall recurrence rates of 29.0% (95% CI 20.9–37.0%) and 32.1% (95% CI 27.0–37.2%), respectively [

11]. Thus, treatment of PSP with conservative methods, without pleurodesis, has limited effectiveness due to the high recurrence rate.

Medical pleurodesis helps reduce the recurrence rate. Comparing patients treated with aspiration or drainage alone with those who received additional pleurodesis with minocycline and followed up for 12 months, the recurrence rates were 49.1% and 29.2%, respectively (p = 0.003) [

12]. Similar results have been reported with autologous blood pleurodesis, with recurrence rates ranging from 0% to 29%, compared with 35-41% for drainage alone without pleurodesis [

13,

14]. However, guidelines do not recommend this as the initial treatment for PSP [

13].

VATS bullectomy and pleurodesis are often indicated in cases of spontaneous pneumothorax with prolonged air leak after drainage or recurrence, with the number of previous episodes ranging from one (56.1%), two (20.6%) or three or more (3.7%) [

9]. It is a safe procedure with a low complication rate and short postoperative hospital stay [

15]. Recurrence rates after VATS range from 0-12.6% [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Many studies have analyzed factors associated with recurrence after surgery. Pooled analysis of 72 reports (published until December 2023) with 23,531 patients by Huang et al. (2024) showed that factors increasing recurrence after surgery included male gender (OR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.41–0.92; p = 0.02), younger age [mean difference (MD): −2.01; 95% CI: −2.57 to −1.45; p < 0.001), lower weight (MD: -1.57; 95% CI: -3.03 to -0.11; p = 0.04), and lower BMI (MD: -0.73; 95% CI: -1.08 to 0.37; p < 0.001) [

17]. However, Brophy et al. (2021) reported that age, gender, smoking, number of previous surgeries, surgical technique, and pleurodesis technique were not associated with recurrence after surgery. The authors also reported that bullectomy combined with pleurectomy for pleurodesis was highly effective in preventing recurrence, with a recurrence rate of 0.0% [

14].

Many studies have compared the outcomes of the two pleurodesis techniques: pleural abrasion and pleurectomy. Studies have shown that pleural abrasion has several advantages over pleurectomy, such as shorter surgical time (78 min vs. 103 min, p = 0.001) [

15], shorter hospital length of stay (MD: -0.25; 95% CI: -0.51 to 0.00), postoperative chest tube duration (MD: -0.30; 95% CI: -0.56 to -0.03), operative time (MD: -13.00; 95% CI -15.07 to 10.92) and less surgical blood loss (MD: -17.77; 95% CI: -24.36 to -11.18). In general, pleural abrasion reduces the “burden” of surgery for patients [

8]. In addition, the reduced risk of bleeding complications with pleural abrasion compared to pleurectomy, especially in patients with coagulopathy, has been noted, whereas pleurectomy can cause Horner’s syndrome [

9]. Meanwhile, mid- and long-term results show no difference between the two mechanical pleurodesis techniques, with no difference in respiratory function and postoperative recurrence rates [

8,

9,

17].

This study used VATS to manage air leaks, bullae, and mechanical pleurodesis, indicated in cases of prolonged air leak for more than 5 days after drainage (29.7%) or recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax (70.3%), including patients with one, two, and three or more episodes (74.7%, 18.1%, and 7.0%, respectively). The results were auspicious, with a postoperative complication rate of 7.6% and a recurrence rate of 2.6% during the 10-year follow-up period. Analyzing the association between recurrence and factors such as gender, smoking, history of previous pneumothorax, technique for suturing air leaks and bullae (manual suturing or endoscopic stapler), and prolonged air leak after VATS for more than 5 days, we found no significant differences (p > 0.05). Comparing the results between patients who underwent pleural abrasion and pleurectomy showed that the two methods were equivalent in terms of postoperative pleural drainage duration (3.2 ± 3.3 vs. 3.1 ± 2.5 days), postoperative complication rate (10.2% and 6.3%), and postoperative recurrence rate (3.89% vs. 0%). However, pleural abrasion had several advantages, such as shorter surgical time (53.1 ± 16.5 vs. 78.1 ± 31.0 min), less intraoperative blood loss (78.9 ± 76.4 mL vs. 152.1 ± 362.6 mL), and less postoperative pain (mild pain 94.9%, moderate and severe pain 5.1% vs. 48.7% and 51.3%), p < 0.01. The main reason for the difference is the difficulty of the technique and the high degree of invasiveness in pleurectomy, causing damage to the intercostal muscles and even the intercostal arteries, increasing the risk of bleeding and blood loss, causing more damage to the sensory nerve branches located in the parietal pleura. Thus, based on the available results, we recommend using pleural abrasion instead of pleurectomy in the prevention of recurrence and treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax.

The study had several limitations: there were few follow-up indicators post-surgery, and the measurement of respiratory function indices after surgery was not comprehensively conducted for all patients. If this variable was fully recorded, it would be of great significance in evaluating and comparing the effects of pleurodesis techniques on the patient's respiratory function post-surgery.

5. Conclusions

VATS bullectomy and mechanical pleurodesis for the treatment of PSP exhibit auspicious results, with a low 10-year postoperative recurrence rate (2.6%). Smoking, history of previous pneumothorax, technique for suturing air leaks and bullae, and prolonged air leak after surgery for more than 5 days were not associated with recurrence (p > 0.05). Pleural abrasion and pleurectomy had similar pooled recurrence rates after 10 years (3.89% vs. 0%, p > 0.05), but pleural abrasion has several advantages over pleurectomy: shorter surgical time, reduced intraoperative blood loss, and reduced postoperative pain (p < 0.01).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.V.A., N.V.N., D.T.L., S.T.N., T.D.N., V.T.N. and H.D.H.; Data curation, H.V.A. and V.T.N.; Formal analysis, H.V.A., D.T.L., N.Q.T. and V.T.N.; Funding acquisition, H.V.A.; Investigation, H.V.A. and V.T.N.; Methodology, H.V.A., N.V.N., D.T.L., S.T.N., B.V.N., N.Q.T., T.D.N., T.T.T., V.T.N. and H.D.H.; Project administration, H.V.A.; Resources, H.V.A. and V.T.N.; Software, H.V.A., T.T.T. and V.T.N.; Supervision, H.V.A., T.D.N. and V.T.N.; Validation, H.V.A., T.T.T. and V.T.N.; Visualization, H.V.A., D.T.L. and V.T.N.; Writing—original draft, H.V.A., N.V.N., D.T.L., S.T.N., B.V.N., N.Q.T., V.T.N. and H.D.H.; Writing—review & editing, H.V.A., N.V.N., D.T.L., S.T.N., B.V.N., N.Q.T., T.D.N., V.T.N. and H.D.H.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for this article's research, authorship, and/or publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam (Reference 88A/2010/HĐĐĐ, date May 9th, 2010).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from subjects or all legal representatives of the patients before the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Assistance with the study: we would like to thank our patients and all the clinical and research staff in the Department of Anesthesia, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam who made the study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest to this article's research, authorship, and/or publication.

Abbreviations

BTS, British Thoracic Society; VATS, Video - Assisted Thoracic Surgery; BMI, Body Mass Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; FEV1, Forced Expiratory Volume in one second; FVC, Forced Vital Capacity.

References

- Melton, L.J., 3rd; Hepper, N.G.; Offord, K.P. Incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax in Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1950 to 1974. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979, 120, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendogni, P.; et al. Epidemiology and management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2020, 30, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramel, F.; Postmus, P.; Vanderschueren, R. Current aspects of spontaneous pneumothorax. European Respiratory Journal 1997, 10, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.P.; et al. Recurrence rates in primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Respiratory Journal 2018, 52, 1800864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadikot, R.T.; et al. Recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax 1997, 52, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, J.F.; et al. Percutaneous parietal pleurectomy for recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. Lancet 1990, 336, 1577–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Moriyama, S. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: evaluation of indications and long-term outcome compared with conservative treatment and open thoracotomy. Chest 2005, 127, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; et al. Pleural abrasion versus apical pleurectomy for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2023, 18, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.; et al. VATS Partial Pleurectomy Versus VATS Pleural Abrasion: Significant Reduction in Pneumothorax Recurrence Rates After Pleurectomy. World Journal of Surgery 2018, 42, 3256–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDuff, A.; Arnold, A.; Harvey, J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax 2010, 65, ii18–ii31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.P.; et al. Recurrence rates in primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-S.; et al. Simple aspiration and drainage and intrapleural minocycline pleurodesis versus simple aspiration and drainage for the initial treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: an open-label, parallel-group, prospective, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet 2013, 381, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How, C.-H.; Hsu, H.-H.; Chen, J.-S. Chemical pleurodesis for spontaneous pneumothorax. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 2013, 112, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, S.; Brennan, K.; French, D. French, Recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax following bullectomy with pleurodesis or pleurectomy: A retrospective analysis. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2021, 13, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; et al. Modified needlescopic video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax: the long-term effects of apical pleurectomy versus pleural abrasion. Surg Endosc 2006, 20, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.T.; et al. Chemical Pleurodesis Using Tetracycline for the Management of Postoperative Pneumothorax Recurrence. Journal of Chest Surgery 2023, 56, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, N.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for recurrent primary spontaneous pneumothorax after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2024, 16, 3696–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).