Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

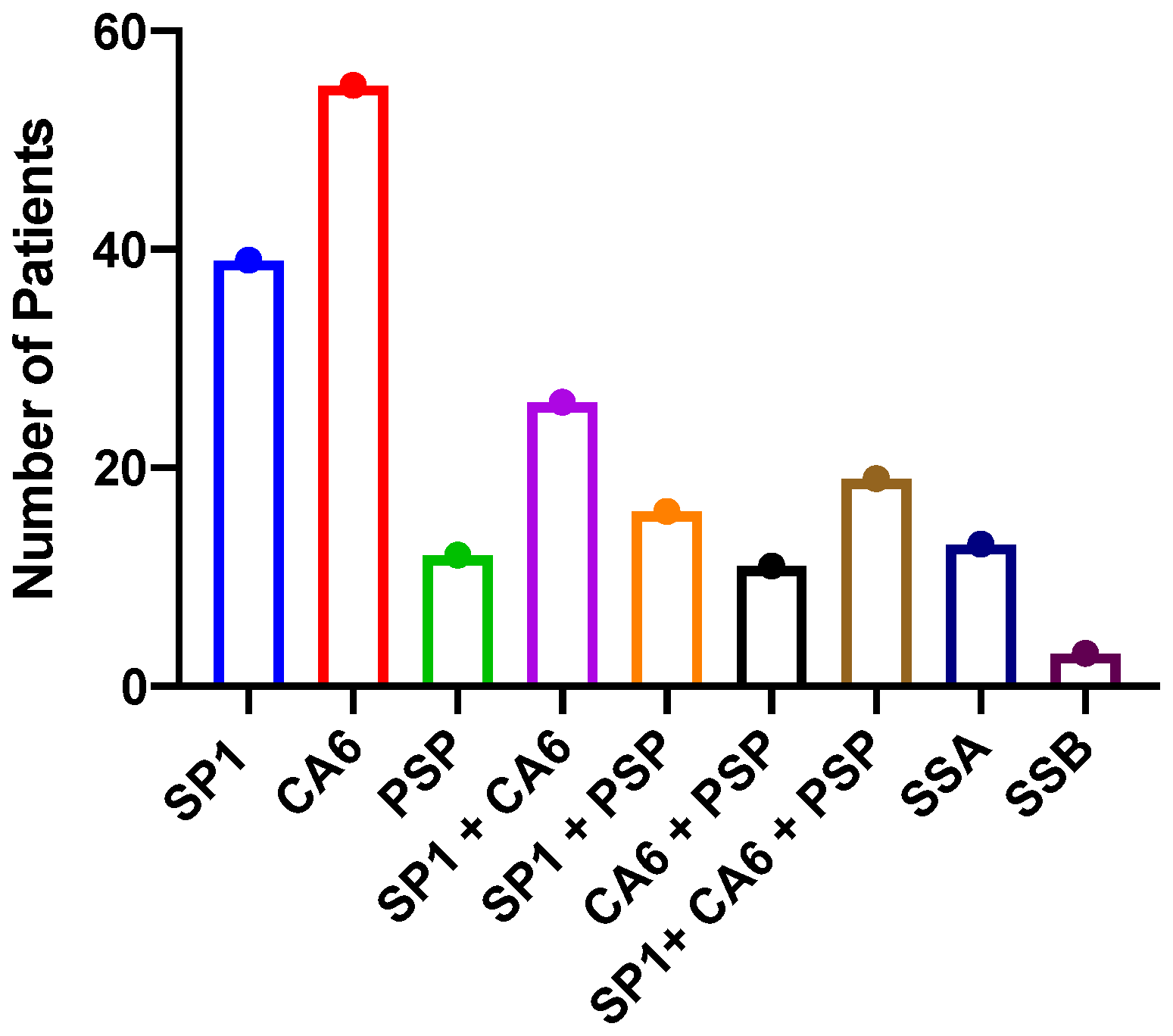

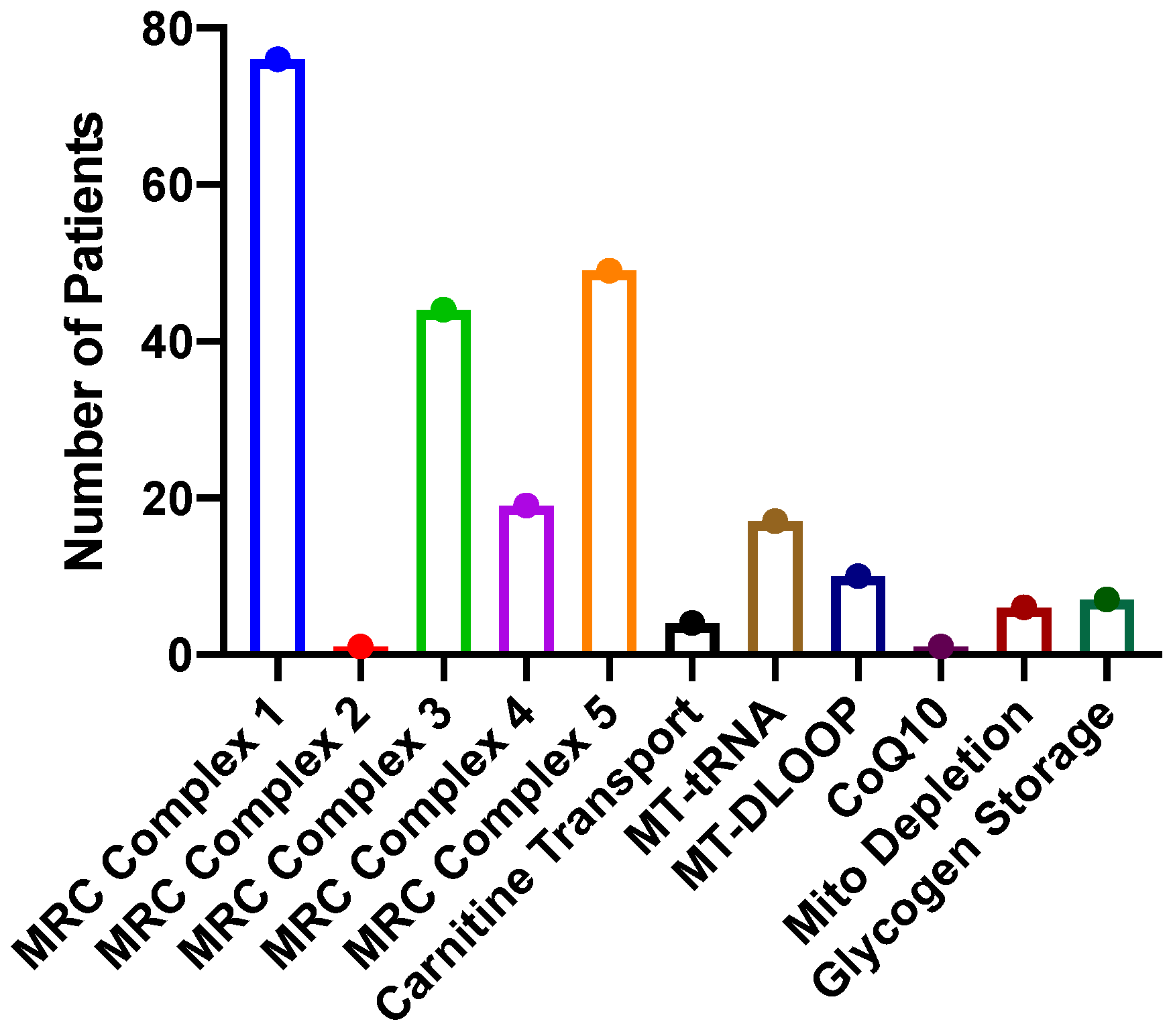

4.1. Patients

4.2. Genetic Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Blanco, L. P., and M. J. Kaplan. 2023. Metabolic alterations of the immune system in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Plos Biology 21: 13. [CrossRef]

- Chavez, M. D., and H. M. Tse. 2021. Targeting Mitochondrial-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species in T Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in immunology 12: 14. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. A., L. MacDonald, M. Kurowska-Stolarska, and A. R. Clark. 2021. Mitochondria as Key Players in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in immunology 12. [CrossRef]

- Freitag, J., L. Berod, T. Kamradt, and T. Sparwasser. 2016. Immunometabolism and autoimmunity. Immunology and Cell Biology 94: 925-934. [CrossRef]

- Huang, N., and A. Perl. 2018. Metabolism as a Target for Modulation in Autoimmune Diseases. Trends in Immunology 39: 562-576. [CrossRef]

- Mubariki, R., and Z. Vadasz. 2022. The role of B cell metabolism in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity reviews 21: 5. [CrossRef]

- Perl, A. 2017. Metabolic Control of Immune System Activation in Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis & Rheumatology 69: 2259-2270. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. C., A. A. Titov, R. Sivakumar, W. Li, and L. Morel. 2016. Immune Cell Metabolism in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep 18: 66. [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, Y. L., L. P. Blanco, and M. J. Kaplan. 2017. Metabolic abnormalities and oxidative stress in lupus. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 29: 442-449. [CrossRef]

- Monteith, A. J., J. M. Miller, J. M. Williams, K. Voss, J. C. Rathmell, L. J. Crofford, and E. P. Skaar. 2022. Altered Mitochondrial Homeostasis during Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Impairs Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation Rendering Neutrophils Ineffective at Combating Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Immunology 208: 454-463. [CrossRef]

- Morel, L. 2017. Immunometabolism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 13: 280-290. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G. A., M. G. L. Wilkinson, and C. Wincup. 2022. The Role of Immunometabolism in the Pathogenesis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Frontiers in immunology 12: 9. [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, A., and G. C. Tsokos. T cell metabolism: new insights in systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis and therapy. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y., Y. Iwasaki, K. Fujio, and K. Yamamoto. 2019. Metabolism as a key regulator in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 48: 1142-1145. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. X., H. Y. Wang, L. Yin, Y. Y. Mao, and W. Zhou. 2020. Immunometabolism in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 3: 10. [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S., E. Simoncelli, R. Priori, and M. Bombardieri. 2023. The pathogenic role of metabolism in Sjögren's syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 41: 2538-2546. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D. Y., L. Li, Y. C. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. L. Ye, J. W. Hu, Y. M. Gao, N. Y. Zeng, X. C. Fei, N. Li, and L. T. Jiang. 2023. Mitochondria-related genes and metabolic profiles of innate and adaptive immune cells in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Frontiers in immunology 14: 16. [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, H., C. K. Bicer, E. F. Yurt, M. A. Serdar, I. Dogan, and S. Erten. Elevated Kynurenine Levels in Patients with Primary Sjogren's Syndrome. Lab. Med.: 7.

- Blokland, S. L. M., M. R. Hillen, C. G. K. Wichers, M. Zimmermann, A. A. Kruize, T. Radstake, J. C. A. Broen, and J. A. G. van Roon. 2019. Increased mTORC1 activation in salivary gland B cells and T cells from patients with Sjogren's syndrome: mTOR inhibition as a novel therapeutic strategy to halt immunopathology? RMD Open 5: e000701. [CrossRef]

- Katsiougiannis, S., A. Stergiopoulos, K. Moustaka, S. Havaki, M. Samiotaki, G. Stamatakis, R. Tenta, and F. N. Skopouli. 2023. Salivary gland epithelial cell in Sjogren?s syndrome: Metabolic shift and altered mitochondrial morphology toward an innate immune cell function. Journal of Autoimmunity 136: 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, N., Y. Li, J. Hu, Y. Wu, J. Yang, H. Fan, L. Li, D. Luo, Y. Ye, Y. Gao, H. Xu, W. Hai, and L. Jiang. 2022. A Link Between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and the Immune Microenvironment of Salivary Glands in Primary Sjogren's Syndrome. Front Immunol 13: 845209. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G., G. Castello, and F. V. Pallardo. 2013. Sjogren's syndrome-associated oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: prospects for chemoprevention trials. Free Radic Res 47: 71-73. [CrossRef]

- Wadan, A. S., M. A. Ahmed, A. H. Ahmed, D. E. Ellakwa, N. H. Elmoghazy, and A. Gawish. 2024. The Interplay of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Oral Diseases: Recent Updates in Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Mitochondrion 78: 21. [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, J. L., A. Jacob, G. A. Weisman, and J. He. 2018. Metabolic changes in the evolution of Sjogren's syndrome in a mouse model. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 36: S301-S301.

- Suresh, L., J. Ambrus, L. Shen, and S. Vishwanath. 2014. Metabolic Disorders Causing Fatigue in Sjogren's Syndrome. Arthritis & Rheumatology 66: S1113-S1113.

- Bax, K., P. J. Isackson, M. Moore, and J. L. Ambrus. 2020. Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase Deficiency in a University Immunology Practice. Current rheumatology reports 22. [CrossRef]

- De Langhe, E., X. Bossuyt, L. Shen, K. Malyavantham, J. L. Ambrus, and L. Suresh. 2017. Evaluation of Autoantibodies in Patients with Primary and Secondary Sjogren's Syndrome. Open Rheumatol J 11: 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Everett, S., S. Vishwanath, V. Cavero, L. Shen, L. Suresh, K. Malyavantham, N. Lincoff-Cohen, and J. L. Ambrus, Jr. 2017. Analysis of novel Sjogren's syndrome autoantibodies in patients with dry eyes. BMC Ophthalmol 17: 20. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., J. Li, J. Chen, M. Shao, R. Zhang, Y. Liang, X. Zhang, X. Zhang, Q. Zhang, F. Li, Y. Cheng, X. Sun, J. He, and Z. Li. 2019. Tissue-Specific Autoantibodies Improve Diagnosis of Primary Sjogren's Syndrome in the Early Stage and Indicate Localized Salivary Injury. J Immunol Res 2019: 3642937. [CrossRef]

- Karakus, S., A. N. Baer, and E. K. Akpek. 2019. Clinical Correlations of Novel Autoantibodies in Patients with Dry Eye. Journal of Immunology Research. [CrossRef]

- Tarnopolsky, M. A. 2008. The mitochondrial cocktail: rationale for combined nutraceutical therapy in mitochondrial cytopathies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60: 1561-1567. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Maraver, J., M. D. Cordero, M. Oropesa-Avila, A. F. Vega, M. de la Mata, A. D. Pavon, E. Alcocer-Gomez, C. P. Calero, M. V. Paz, M. Alanis, I. de Lavera, D. Cotan, and J. A. Sanchez-Alcazar. 2014. Clinical applications of coenzyme Q10. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 19: 619-633.

- Nicolson, G. L. 2014. Mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic disease: treatment with natural supplements. Altern Ther Health Med 20 Suppl 1: 18-25.

- Glover, E. I., J. Martin, A. Maher, R. E. Thornhill, G. R. Moran, and M. A. Tarnopolsky. 2010. A RANDOMIZED TRIAL OF COENZYME Q(10) IN MITOCHONDRIAL DISORDERS. Muscle & Nerve 42: 739-748. [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, I., E. Shadiack, R. D. Ganetzky, and M. J. Falk. 2020. Mitochondrial medicine therapies: rationale, evidence, and dosing guidelines. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 32: 707-718. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A., S. K. Prasad, O. Banerjee, S. Singh, A. Banerjee, A. Bose, S. Pal, B. K. Maji, and S. Mukherjee. 2018. Targeting mitochondria with folic acid and vitamin B-12 ameliorates nicotine mediated islet cell dysfunction. Environmental Toxicology 33: 988-1000. [CrossRef]

- Avula, S., S. Parikh, S. Demarest, J. Kurz, and A. Gropman. 2014. Treatment of Mitochondrial Disorders. Current Treatment Options in Neurology 16. [CrossRef]

- Ezerina, D., Y. Takano, K. Hanaoka, Y. Urano, and T. P. Dick. 2018. N-Acetyl Cysteine Functions as a Fast-Acting Antioxidant by Triggering Intracellular H2S and Sulfane Sulfur Production. Cell Chemical Biology 25: 447-+. [CrossRef]

- Cruzat, V., M. Macedo Rogero, K. Noel Keane, R. Curi, and P. Newsholme. 2018. Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients 10. [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R., M. T. Mulholland, M. Sedensky, P. Morgan, and S. C. Johnson. 2023. Glutamine metabolism in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 126: 12. [CrossRef]

- Hannah, W. B., T. G. J. Derks, M. L. Drumm, S. C. Gruenert, P. S. Kishnani, and J. Vissing. 2023. Glycogen storage diseases. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 9: 23. [CrossRef]

- Kishnani, P. S., A. A. Beckemeyer, and N. J. Mendelsohn. 2012. The new era of Pompe disease: Advances in the detection, understanding of the phenotypic spectrum, pathophysiology, and management. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C-Seminars in Medical Genetics 160C: 1-7.

- Kley, R. A., M. A. Tarnopolsky, and M. Vorgerd. 2008. Creatine treatment in muscle disorders: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79: 366-367. [CrossRef]

- Llavero, F., A. A. Sastre, M. L. Montoro, P. Galvez, H. M. Lacerda, L. A. Parada, and J. L. Zugaza. 2019. McArdle Disease: New Insights into Its Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20. [CrossRef]

- Meena, N. K., and N. Raben. 2020. Pompe Disease: New Developments in an Old Lysosomal Storage Disorder. Biomolecules 10. [CrossRef]

- Vissing, J., and R. G. Haller. 2003. The effect of oral sucrose on exercise tolerance in patients with McArdle's disease. N Engl J Med 349: 2503-2509. [CrossRef]

- Raben, N., A. Wong, E. Ralston, and R. Myerowitz. 2012. Autophagy and mitochondria in Pompe disease: Nothing is so new as what has long been forgotten. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C-Seminars in Medical Genetics 160C: 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K., and O. Kakhlon. 2024. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Glycogen Storage Disorders (GSDs). Biomolecules 14: 24. [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, J. J., P. J. Isackson, M. Moore, J. Butsch, and L. Balos. 2020. Investigating Fatigue and Exercise Inotolerance in a University Immunology Clinic. Archives of Rheumatology and Arthritis Research 1: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M. J., S. Aguilera, I. Castro, P. Carvajal, D. Jara, C. Molina, S. Gonzalez, and M. J. Gonzalez. 2021. Dysfunctional mitochondria as critical players in the inflammation of autoimmune diseases: Potential role in Sjo & uml;gren & rsquo;s syndrome. Autoimmunity reviews 20: 12.

- Ryo, K., H. Yamada, Y. Nakagawa, Y. Tai, K. Obara, H. Inoue, K. Mishima, and I. Saito. 2006. Possible involvement of oxidative stress in salivary gland of patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Pathobiology 73: 252-260. [CrossRef]

- Norheim, K. B., S. Le Hellard, G. Nordmark, E. Harboe, L. Goransson, J. G. Brun, M. Wahren-Herlenius, R. Jonsson, and R. Omdal. 2014. A possible genetic association with chronic fatigue in primary Sjogren's syndrome: a candidate gene study. Rheumatology International 34: 191-197. [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Uribe, L., M. Rojas, G. Azizi, J. M. Anaya, and M. E. Gershwin. 2019. Primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autoimmunity 99: 52-72. [CrossRef]

- Maslinska, M., and K. Kostyra-Grabczak. 2022. The role of virus infections in Sjogren's syndrome. Frontiers in immunology 13: 18. [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, G., S. Cappelli, and R. Consolini. 2021. Autoimmunity in Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders: An Updated Review on Pathogenic and Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10: 20. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X. Q., and A. H. Sawalha. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Epigenetic Changes Underlying Autoimmunity. Antioxidants & redox signaling: 18. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., R. M. Smolkin, P. Chowdhury, K. C. Fernandez, Y. Kim, M. Cols, W. Alread, W. F. Yen, W. Hu, Z. M. Wang, S. Violante, R. Chaligne, M. O. Li, J. R. Cross, and J. Chaudhuri. 2023. Distinct metabolic requirements regulate B cell activation and germinal center responses. Nature Immunology: 33. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewicz, M., A. Ronowska, M. Zielinski, A. Jankowska-Kulawy, and P. Trzonkowski. 2023. T regulatory cells metabolism: The influence on functional properties and treatment potential. Frontiers in immunology 14: 11. [CrossRef]

- Abboud, G., S. C. Choi, X. J. Zhang, Y. P. Park, N. Kanda, L. Zeumer-Spataro, M. Terrell, X. Y. Teng, K. Nundel, M. J. Shlomchik, and L. Morel. 2023. Glucose Requirement of Antigen-Specific Autoreactive B Cells and CD4+T Cells. Journal of Immunology 210: 377-388. [CrossRef]

- Dimeloe, S., A. V. Burgener, J. Grahlert, and C. Hess. 2017. T-cell metabolism governing activation, proliferation and differentiation; a modular view. Immunology 150: 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y., S. C. Choi, Z. Xu, D. J. Perry, H. Seay, B. P. Croker, E. S. Sobel, T. M. Brusko, and L. Morel. 2015. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med 7: 274ra218. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Y., N. Jacquelot, and G. T. Belz. 2022. Metabolic features of innate lymphoid cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 219: 15. [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, A. K., E. J. Panther, and C. M. Reilly. 2022. Altered Germinal-Center Metabolism in B Cells in Autoimmunity. Metabolites 12: 16. [CrossRef]

- Buck, M. D., D. O'Sullivan, and E. L. Pearce. 2015. T cell metabolism drives immunity. Journal of Experimental Medicine 212: 1345-1360.

- Sarkar, A., D. Chakraborty, S. Malik, S. Mann, P. Agnihotri, M. Monu, V. Kumar, and S. Biswas. 2024. Alpha-Taxilin: A Potential Diagnosis and Therapeutics Target in Rheumatoid Arthritis Which Interacts with Key Glycolytic Enzymes Associated with Metabolic Shifts in Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes. Journal of Inflammation Research 17: 10027-10045. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L., L. Suresh, K. Malyavantham, P. Kowal, J. X. Xuan, M. J. Lindemann, and J. L. Ambrus. 2013. Different Stages of Primary Sjogren's Syndrome Involving Lymphotoxin and Type 1 IFN. Journal of Immunology 191: 608-613. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L., C. Gao, L. Suresh, Z. Xian, N. Song, L. D. Chaves, M. Yu, and J. L. Ambrus, Jr. 2016. Central role for marginal zone B cells in an animal model of Sjogren's syndrome. Clin Immunol 168: 30-36. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A., J. He, A. Peck, A. Jamil , V. Bunya, J. Alexander, and A. J. JL. 2025. Metabolic changes during evolution of Sjogren’s in both an animal model and human patients. Heliyon 11: e41082. [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C. H., S. C. Shiboski, R. Seror, L. A. Criswell, M. Labetoulle, T. M. Lietman, A. Rasmussen, H. Scofield, C. Vitali, S. J. Bowman, X. Mariette, and W. Int Sjogren's Syndrome Criteria. 2017. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjogren's Syndrome A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis & Rheumatology 69: 35-45.

- Sheppard, J. D., M. C. Jasek, K. Malyavantham, L. Suresh, J. L. Ambrus, and D. Pardo. 2015. Two Year Results with IgG, IgA and IgM Antibody Specific to SP-1, PSP and CA-6 early Novel Antigens Compared to Classic Biomarkers in 2306 Dry Eye Patients. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 81: 348-349.

- Suresh, L., K. Malyavantham, L. Shen, and J. L. Ambrus. 2015. Investigation of novel autoantibodies in Sjogren's syndrome utilizing Sera from the Sjogren's international collaborative clinical alliance cohort. Bmc Ophthalmology 15. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L., E. K. Kapsogeorgou, M. X. Yu, L. Suresh, K. Malyavantham, A. G. Tzioufas, and J. L. Ambrus. 2014. Evaluation of salivary gland protein 1 antibodies in patients with primary and secondary Sjogren's syndrome. Clinical Immunology 155: 42-46. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).