1. Introduction

This article engages with an especially problematic kind of photography: anthropometric “types”, mostly elaborated by (sometimes self-declared) anthropologists who used these stereotypical and degrading pictures of human beings to support and develop theories of the so-called “scientific” racism – which from nowadays point of view has nothing scientific about it.1 In their majority, these anthropometric types display indigenous peoples (or Africans outside Africa - (Ermakoff 2004)). These types of photographs have been amply studied for different parts of the globe (Poole [1997] 2021; Justnik 2012; Hight and Sampson 2002; Blumauer 2014; Calvo and Semper-Puig 2023; Jordán 2016; Onken 2015; Reinert 2017; Jäger 2006) including the Philippines (Aloysius Ma. L. Cañete 2008; Rice 2014; Rohde-Enslin 1999; Vergara 1995; Fernandez 2023; Best 2023). This article focuses on another categorization in these photographs: “mestizos” and “mestizas”, i.e. people with assumed “mixed” ancestry. There is ample research about the mestizo as a colonial categorization in the Philippines (cf. below), but very little about its visual representation in the early twentieth century. Therefore, this article brings together the research about the colonial categorization mestizo/mestiza and photographic types, which have been largely analyzed separately until now.

Miscegenation played an important role in theories of racism, and therefore also the categorization of the mestizo/mestiza. In this article, I will first provide context by defining anthropometric types, then sketch out the meaning of the term mestiza/mestizo in the Philippines, followed by an analysis of the photographic examples which all stem from the collection Küppers-Loosen in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne, Germany. These examples will be used to explain some mechanisms which furthered the dissemination of ideas about racialization. How were the aesthetics of anthropometric types published, distributed and consumed by a broad audience? How did the distribution of forms of visual representation work on the ground? I will show that there is quite some heterogeneity as to the visual representation of mestizos and mestizas.

2. Analyzing Anthropometric Types

Types are portraits of people who were supposed not to represent specific individuals with their names (although of course they were representations of individuals), but they were intended to represent a specific populational group (Justnik 2020, p. 5). A type would thus typically depict either a certain profession or a cultural, ethnic or racialized group; sometimes both collapsed. Gender and age were crosscutting categorizations. As Burke (2001, p. 138) has put it, the authors or photographers of types “generally concentrated on traits which they considered to be typical, reducing individual people to specimens of types to be displayed in albums like butterflies. What they produced were what Sander Gilman calls ‘images of difference’.” Anthropometric types were typically elaborated of non-European, indigenous or Afrodescendant persons (Hight and Sampson 2002, p. 3) but also within Europe certain groups were similarly represented; especially in Eastern Europe (cf. e.g. (Hoyer and Röger 2023; Justnik 2012)).

Types have existed in a broad variety of media, but this article will focus on photographs. Photographic types were both taken in and outside the studio. Essential in the definition of types are captions and the use of the image. A picture taken of a certain individual in a photographic studio can theoretically be both: on the one hand the portrait of an individual whose name is known and whose portrait is destined for the album of family or friends or, on the other hand, a type, sold by the studio to national and international tourists. In fact, as Justnik (2020, p. 7) has shown, sometimes one and the same picture was used both as an individual portrait and as a type.2

The stereotypical representation of certain populational groups has a long tradition in European art, being the early modern costume books which focused mostly on the dress and profession of peoples in certain regions, the best known example (Mentges 2015). Similarly successful were the casta paintings in eighteenth-century New Spain, which categorized the represented couples with their offspring according to their degree of European-African-Indigenous miscegenation (Katzew 2004; Castañeda García 2020). At about the same time as the first casta paintings, a broad cultural phenomenon called costumbrismo emerged in the Hispanic world. A sub-genre of the costumbrismo were the tipos y costumbres, the types and customs which played an important role in the forging of nationalism and in debates about modernity, also in the Philippines which still continued to be subject to Spain until 1898. These types were conceived as typical for a certain nation or ethnic group, often with a focus on profession, in a highly gendered and racialized way. They were produced in an ample number of media: watercolors, lithographs, woodcut prints, ceramics and wax figurines, and, as the nineteenth century progressed, increasingly in photographs (Barros and Buenrostro 1994, pp. 20–21). These types are sometimes denominated as “tipos del país” (types of the country) or as “tipos populares” (popular types). Despite aiming at showing something typical of a certain place, sometimes the images were not produced locally, as the example of the production of Peruvian types in Chinese studios in the nineteenth century shows (Majluf 2006, pp. 40–41).

Photography was introduced to the Philippines in 1841 (Go 2014). Photographic types were first disseminated in the form of cartes de visites from the 1850s onwards (Uslenghi 2019, p. 520) and from the 1890s onwards, often as postcards (Onken 2019, pp. 28–29), as well as in scientific publications and magazines, such as National Geographic, where also Worcester published amply (Worcester 1913).

Anthropology, firmly established as an academic discipline in the nineteenth century and much inspired by the Illustration, also made use of the technology of photography to produce what could be called anthropometric types. Here, the focus was not so much on professions but more on the physical traits of the represented peoples. These types had precedents in other media and genres, most notably travel reports. Starting during the eighteenth century and experiencing a heyday during the nineteenth century, European illustrated travelers, most of them men, had set off to explore and measure the world, an intent to construct a “global-scale meaning through the descriptive apparatuses of natural history” (Pratt [1992] 2008, p. 15); being the zoological taxonomy developed by Linnaeus a key inspiration for human taxonomies (Hund 2010, p. 2193).

Examples for such images in travel reports from the Philippines are the illustrations accompanying Murillo Velarde’s 1749 history of the Jesuit province in the Philippines (Murillo Velarde 1749) or drawings such as the “Spanish-Tagalog mestiza” in the 1873 travel report by the German ethnographer Fedor Jagor (1873b, p. 184; van der Wall 2018). Also the Philippine painter José Honorato Lozano, trained in Chinese painting techniques, elaborated a broad number of tipos filipinos, Philippine types, including several depictions of mestizos and mestizas (Lozano 1847).

Though most of these illustrations are generally categorized as costumbrista images, the difference between anthropomorphic and costumbrista types is not categorical, but gradual. The aesthetic of anthropometric types is closer to criminal photography, typically portraying the persons both in frontal and profile view and sometimes although in posterior view; in some instances including the entire body, in others only head and shoulders. Often, the background is neutral or white, and sometimes some kind of improvised measuring stick is included in the photograph. Sometimes, the portrayed individuals are naked or half-naked. These characteristics were intended to ease anthropometric measurements of head and body, integral characteristics of the methodology of biologist racism which developed craniology, cephalometry and biometry as own subdisciplines (I. Hannaford 1996, pp. 260–62). As Sámano Verdura (2014, p. 41) has aptly pointed out, anthropometric types intended a racialized classification, costumbrista types a social one.3 Costumbrista types tended to focus more on profession and clothing than on the body and orchestrated the people in a supposed day-to-day setting, either staged in the studio or in apparent snap-shots (that were mostly not really spontaneous due to the limitations of technology) in city or countryside. Generally, they have been interpreted as constituting a key visual element in the construction of the newly formed or forming nations (Rojas Rabiela and Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba 2018, p. 24; Majluf 2006, p. 16; Conrad 2006; Justnik 2020, p. 7; Massé 2014, p. 45; Rodríguez Bolufé 2021, p. 140). However, racialization and nationalism as well as enduring colonial structures were not mutually exclusive, quite the contrary.

The overlapping in both aesthetics and use of anthropomorphic and costumbrista types can be seen in a variety of examples. For instance, anthropologists employed also costumbrista images for their research. As Poole (2021, pp. 134–35) has demonstrated for the Andes, several European and US-American scholars bought cartes de visites displaying Andean indigenous peoples and employed them for their taxonomic studies.4

As elsewhere in the world, the production and distribution of types obtained a boost in the Philippines with the introduction of photography. There is evidence of types produced in the form of daguerreotypes already in the 1840s (Sierra de la Calle, Blas 2022, pp. 252–53). Already in the 1860s, a significant number of photo studios existed in Manila, most of them located on the Escolta road, and their number continued to grow in the following decades; in Manila and in other cities and on other Islands. Many were run by foreigners, especially Europeans, but there were some run by Filipinos (Sierra de la Calle, Blas 2022). Some of the studios, such as M.A. Honis continuously sold photographic types, as can be seen in their advertisements in travel guides (Gonzalez Fernandez 1875, p. 669). One of the most famous Filipino photographers, Félix Laureano, published a book in Barcelona which contains several types from Ilo-Ilo (Laureano 1895).

Already during the US take-over of the Philippines, a lot of US photographers came to the Philippines; first to document the war and then the newly obtained colonies. Their photographs were distributed, among others, as postcards and in books (E. Hannaford 1900; Anonymous 1900; Landor 1904). Sometimes, the photographs were published together with photographs from Cuba and Puerto Rico which were also acquired as colonies/protectorates as a result of the war (Olivares 1899). US anthropologists joined the ranks of European anthropologists that had shown an interest in the Islands since the nineteenth century, many of them Germans. Some of them published photographic types in album-like books (Meyer and Schadenberg 1891; Reed 1904a; Scheerer 1905). Robert Bean (1910) even published a manual as to how to determine Filipino types according to the racist anthropometric methodology of the time. The Ortigas Foundation, which has hundreds of digitized photographic types from the turn of the century, many of them in the form of postcards, also contains photos of mestizas and some mestizos, mainly from the US colonial period (The Ortigas Foundation Library).

The best-known photographic types from the Philippines of that time are the ones elaborated by Dean Worcester and his crew. Like other travelers, administrators and anthropologists of the time, they used the photographs to legitimize racist taxonomies. Here, the photographs of mestizos/mestizas have been selected and contrasted with the depiction of mestizos/mestizas from a local photo studio. To fully comprehend the analysis, the meaning of the term mestizo/mestiza in the Philippines has to be explained.

I would like to remark that I employ the categorizations used in the captions of the photographs and in the sources more generally in quotation mark to distance myself from their oftentimes racist and derogatory character.

3. Mestizos and Mestizas in the Philippines

From their annexation by the Spaniards in 1565 until Mexico’s/New Spain’s independence from Spain in 1821, the Philippines were administered via the viceroyalty of New Spain. This meant that their economies and societies were entangled and that they had in principle a common legislation which was, however, casuistic in nature. One part of this legislation pertained to the colonial categorization of the mestizo. In New Spain (and Spanish America more generally), it came to denote some decades after the initial conquest, the offspring of Spanish and Indigenous parents. In the Philippines, this kind of individuals was denoted “Spanish mestizo” (mestizo de español) to separate them from the “Chinese” or “Sangley mestizos” (mestizos de sangley). The latter were the descendants of indigenous Filipinos and the Chinese, i.e. sangley population in the Philippines. In contrast to Indigenous people and (at least theoretically) free Afrodescendants, (Spanish) mestizos were exempted from tribute payments and labor corvée. Mestizos de sangley, however, were tribute payers, but did not have to do corvée labor (Albiez-Wieck 2021). The Philippines only gained Independence from Spain in 1898 as a result of the Spanish-US-American war, only to almost immediately become a US-colony, having suffered from several massacres by the US-army in the process (Wagner 2024). During the course of the nineteenth century, the colonial categorizations continued and, according to Abinales and Amoroso (2005, p. 89) mestizos de sangley continued to pay less taxes than sangleyes but more than rich, urbanized indios until tribute was abolished in 1884.

It has been stated that the mestizos de sangley or Chinese mestizos played an important role in the formation of the evolving Philippine middle class, however problematic this term might be (Tan 1986, p. 141; Coo 2019, p. 28). Undoubtedly, several mestizos (and mestizas) de sangley pertained to the group of Philippine intellectuals called ilustrados (“illustrated”) which played an important role in the process of the short-lived independence at the end of the nineteenth century (Tolliver 2019, p. 242), with José Rizal, the Philippine hero of Independence being the most famous example. However, as Abinales and Amoroso (2005, p. 99) have argued, “ethnic distinctions between Chinese and Spanish mestizos and indio elites had become anachronistic and were replaced by class-, culture-, and profession-based identities. The three groups gravitated toward a common identity and found it in the evolving meaning of ‘Filipino’.”

The US-colonial rule which quickly followed the Spanish one, encouraged Filipino participation in the colonial administration, at least in the lower echelons (Abinales and Amoroso 2005, p. 119). The US administration, like the Spanish one, continued to foster a hierarchical and deeply racialized social organization but with some important differences. It continued with the differentiation between Christian and non-Christian groups; with the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes being responsible for the administration of the latter. “Tribe” began to be used as term for the different groups inhabiting the Philippine Islands. With regard to mestizos, the US-administration abolished the former differentiation between “Spanish-Filipino” and “Chinese-Filipino” as census categorizations – but it maintained differentiating (and discriminating) the “Chinese” (Abinales and Amoroso 2005, p. 124); thereby following contemporary ideas of racialized inferiority of Chinese which were present in the USA (Volpp 2000). At the same time, and in line with policies in the US and elsewhere, many US administrators considered racialized “mixing” as something leading to degeneration. However, there were also voices in the US, such as that of Frederick Chamberlain, author of the book “the Philippine problem” (1913, p. 234) who thought that the “mixing” of Filipinos with Europeans and Chinese had had positive effects in the past since he considered the “mixed” children to be much better than their Filipino parent. But overall, these voices could not impose themselves. In the Jim-Crow-US, the one-drop-rule and a system of segregation was institutionalized and racialized “mixing” even became a felony (Hund and Emmerink 2018). Or, as Buscaglia-Salgado (2018, p. 115) has put it for the US: “miscegenation is the criminalization of mestizaje”.

In the following, I will take a closer look on how these ideas were communicated visually on the ground, focusing on the interactions between administration, academy and public sphere.

4. Dean Worcester’s Vision on Mestizos in the Philippines

The best-known US-administrator and researcher of the Philippines who fostered a racialized perception of the Filipino population was Dean Worcester. He had visited the Philippines under Spanish rule from 1887-1888 as a student, became member of the Schurmann and Taft commissions and was Secretary of the Interior from 1901 until 1913, as which he created in 1901 the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes as well as the Bureau of Science. In the meantime, he had resigned from his position of teaching zoology at the University of Michigan. He and his team produced more than 5,000 negatives of the Philippine’s population; mostly on trips that took place between 1900 and 1911. These photographs have been studied amongst others by Rice (2014, pp. 2–4, 2011), Vergara (1995), and Fernandez (2023) but with a focus on his representations of indigenous groups and especially in Luzón. Worcester took a very active role in distributing a considerable part of these photographs worldwide, though with a clear preponderance on the photographs of the indigenous group he called “Negritos” like the anthropologists and administrators of the time. Today they are known and self-identify as Aetas.

More than three thousand positives by Worcester are today in the collection of the ethnographic Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum (hereafter RJM) in Cologne, Germany and these were the ones consulted for this article; with special emphasis on those depicting mestizos and mestizas. In a letter to Küppers-Loosen, the collector who acquired the prints, Worcester stated that he sold a very similar collection to Mr. Ayer in the US (Worcester 1906a, pp. 3–5). Furthermore, a printed list of prices is included in the documentation; a print which would not have been made if there would not have been a considerable number of buyers.5 Rohde-Enslin who studied part of the RJM collection in the 1990s, tells us that 829 of the 3,477 photographs of the collection have been published 1167 times in total (Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 278).

These photographs were an important tool in the elaboration of a detailed racialized and hierarchical taxonomy of the population which is reflected in the organizational schemes of his various versions of the catalogues of these photographs.5 As Rice (2014, pp. 34–35) has shown, these lists were not completely concordant in their numeration, but their general racist logic was consistent. It intersected with religious discrimination – 90% of the photographs were taken of what he labelled as Non-Christian groups. The original list consisted of nineteen hierarchized categories, with a series of numbers not being filled. In a 1902 and 1905 Index and in the Archive of the University of Michigan of Ann Arbor, where most of the negatives of Worcester are preserved, the group he called “Negritos” was always labelled as belonging to the lowest category, no. 1, since he felt them to be the less civilized. Quite surprisingly, mestizos (numbered 31) and “mixed populations” (numbered 32) had the highest numbers and were therefore located at top of this hierarchy (Rice 2014, p. 29). In the Index of photographic positives which Worcester sold to Küppers-Loosen and which are preserved in the RJM, mestizos and “mixed populations” were both numbered 32. They come after the Japanese (number 30) and the Chinese as well as the Spanish who share number 31. “Pure Americans” are nowhere to be found in this list, but individual US-citizens are occasionally listed with their names and are photographed – but not as anthropometric types.

In the following, I will analyze how mestizos and “mixed” people are represented and described in the Philippine materials contained in the RJM. Most of the photographs whose author is being identified in the catalogue or the Index elaborated by Worcester were taken by Dean Worcester or a member of his crew; being C. Martin and J. Diamond two of them. There are, however, a few photographs with the label “Dyonisio Encinas” or “Piang Studios” (on the photographs and/or in the catalogue); seemingly a Filipino photographer and his studio which were located in Zamboanga, Mindanao. It is unclear from the pertaining documentation if they were sold by Worcester to Küppers-Loosen or if Küppers-Loosen, who visited the Philippines in 1906 (Englehard and Rohde-Enslin 1997, p. 34), did purchase them directly himself.5

In the digital inventory of the RJM, 82 prints refer to “mestizos” or person labelled as being of “mixed blood” (labelled as “Mischblut”5 in German). Mestizo, like many other categorizations and stereotypes, is a term which Worcester adopted from the Spanish colonial terminology (Cf. (Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 283). It is worth taking a closer look the subcategories of “mestizos” and “mixed populations” in the RJM collection. In the digital inventory, 26 entries refer to “mestizos”, 56 to “mixed populations”. The former, mestizos, are divided into “Spanish, Chinese, German, American”, i.e. “mixtures” of Filipinos with national groups outside of the Philippines. The latter, “mixed populations” were divided into “Ilocanos and God-Danes of Isabela” and “Tagalogs and Ilocanos, Nueva Ecija”, i.e. different groups original to the Philippines (Worcester, p. 37).

The separation of different types of “mixture” implied a hierarchization between the two. This becomes clear if one reads first the initial description of the Series 32:

The Mestizos

"Mestizo" is a word applied in the Philippine Islands to a person of mixed race. The most intelligent and highly educated and influential men in the Islands are Spanish mestizos. Many of the best business men are Chinese mestizos, and those two classes are numerically and in every other way by far the most important classes which exist.

There may be found a limited number of French and German mestizos, and since the American occupation many children have been born of American fathers (both white and black) and Filipinomothers (Worcester, p. 641).

Later on, in the same series, he differentiates the mestizos, from what he calls “mixed populations”:

In some provinces there is such a mixture of representatives of the different civilized tribes, that it is impossible to determine to which one of the many tribes any given individual or family probably belongs without actually inquiring, as there is nothing in dress, manner or customs to afford an unfailing index to the tribal relations of such people. This is especially the case in the Provinces of Cagayan, Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya, where Ilocano immigrants are inextricably confused with the old Gad-dan settlers. In the following small series of views no attempt has been made to distinguish between the two tribes (Worcester, p. 648).

Here, Worcester speaks of “mixtures” only among what he considered to be “civilized tribes”, which meant that they were Christianized. However, in other parts of the Index, he also speaks of persons of “mixed blood” (e.g. (Worcester, p. 111) among the “Negritos”/Aetas, the non-Christian group he labelled as less “civilized” and which occupied the lowest echelon in his racist taxonomy. In the descriptions, he seems to claim that he could tell apart degree of “mixtures”, as in the following description of the picture numbered 1-b 49: “Group of five Negrito men of mixed blood; indeed the man at the left seems to have no Negrito blood at all and the man at the right has very little” (Worcester, p. 111). This contrasts with the quote above where he said that he could not tell apart visual differences among the “civilized” peoples which intermarried with each other. This is in line with the conclusion of Enslin and Englehard who studied mainly the photographs of the “Non-Christian tribes”. They state that there is a certain degree of arbitrariness and manipulation in the captions which show us that the categorizations were not very convincing (Englehard and Rohde-Enslin 1997, p. 41; Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 283).

In the following, I will briefly analyze three photographs of people labelled as “mestizos” or of “mixed blood” in the RJM collection. All three images were donated to the RJM by Ms Küppers, as part of her late brother’s collection in May 1911. Only the first two bear the additional remark that they had been bought by Mr. Küppers-Loosen from the Bureau of Science in Manila in 1906. The first two photographs are good examples as how Worcester staged his photographs in order to exemplify his racist taxonomy. I hypothesize that the third one is probably not a photograph by Worcester or his crew but one made by a Filipino studio; possibly the already mentioned Piang studio and probably acquired directly by Küppers-Loosen during his stay in Manila. All three photographs are quite different from each other. Only the first one is a typical example of an anthropometric type. While the first one can be seen as paradigmatic of hundreds of similar photos in the collection, the second and especially the third one constitute rather exceptions. Photos like the first one were of the type which was distributed most widely through publications and lantern shows by Dean Worcester.

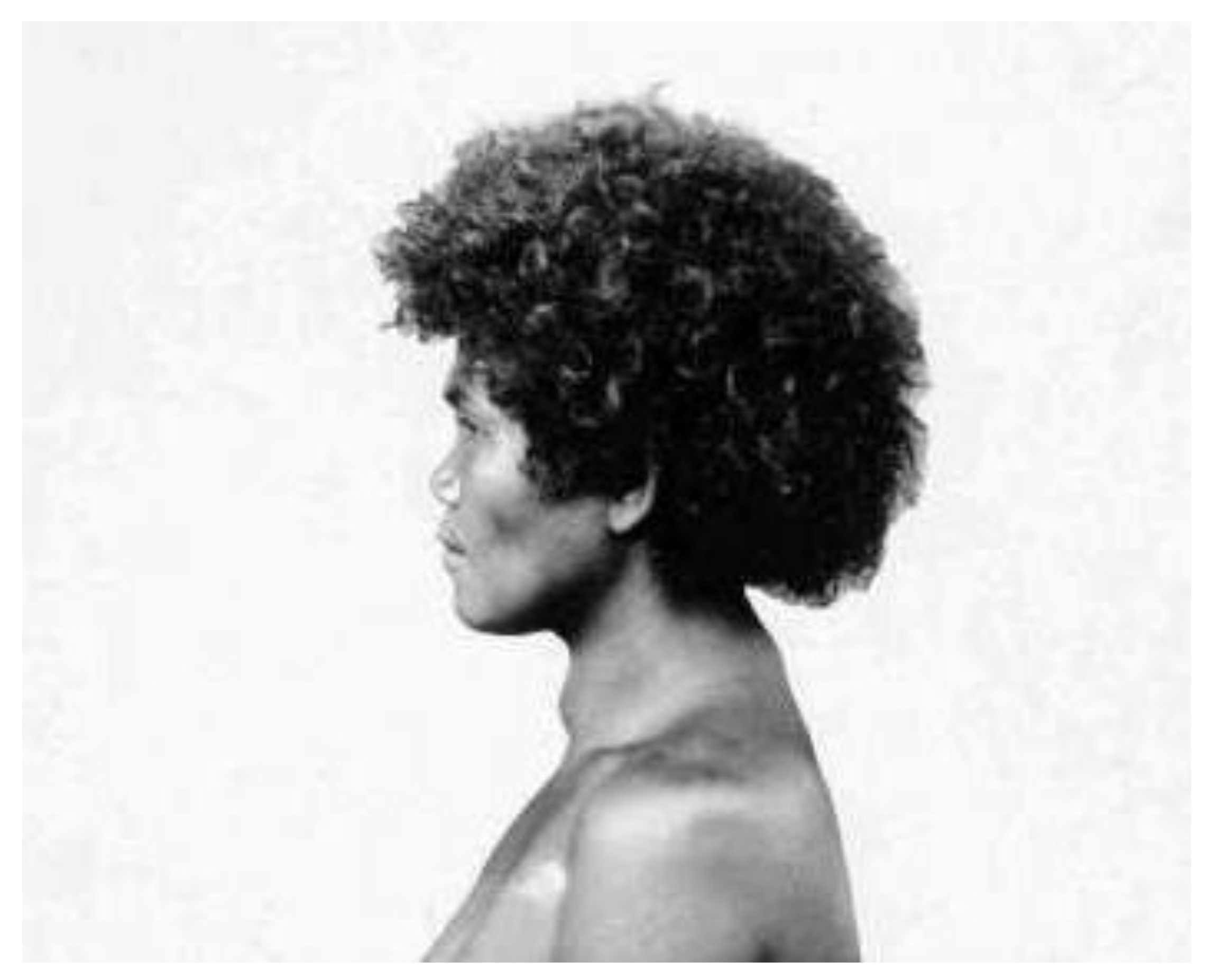

The first image (cf.

Figure 1) carries the inventory number 5806 in the RJM, but it also has an original number from the Index elaborated by Worcester/the Bureau of Science, which is 1b68. The number one attributes it to the “Negritos”/Aetas-series which occupied the lowest echelon in Worcester’s taxonomy. The letter „b“ is a geographic indication, referring to the province Zambales on the main Island Luzón. The number 68 results from the numeration of the photographs in this series. The representation of those “Negritos” categorized as being of “mixed blood” does not differ from the depiction of “Negritos” categorized by Worcester and his crew as “pure”. Everything labelled by him as “Negrito woman of mixed blood” (Worcester, p. 114) (“Negrito-Weib. Mischblut” in the German caption) tells us about Worcester’s depreciation for this group: From the derogatory name “Negrito” instead of Aeta to the “half length side view” (Worcester, p. 114) which was used for anthropometric measurements to the relatively short curly hair. None of the mestizos categorized as more civilized in the series 32 is photographed in this position – nor are they depicted with bare breasts, an element of eroticization typical in colonial contexts and which have already been pointed out for Worcester’s work and which I deliberately omitted here by cropping the image (McClintock 1995; Rohde-Enslin 1992, 238,287-290; Rice 2011). Also in the longer texts about the “Negritos” in the Index and in his publications, Worcester makes his contempt for the “Negritos” clear (Worcester, pp. 88–143). A contempt which can be summarized in the following quote by him: “They seem to be incapable of any considerable progress and cannot be civilized. Intellectually they stand close to the bottom of the human series” (Worcester 1914, p. 532).

This racist view of the “Negritos”/Aetas – categorized either as “mixed” or “pure” was not only distributed widely by the photographs Worcester employed in his publications and highly successful public talks with lantern shows, but also in publications by (former) members of Worcester’s crew (Rice 2014, pp. 19–21, 2011). In the RJM Index, Worcester mentions that several photographs were used in the publication “’The Negritos of Zambales’ by Mr. Wm A. Reed, formerly an employee of the Ethnological Survey” (Worcester, p. 109). And in fact, the photograph analyzed here is contained in that said publication with the caption “Negrito woman of Zambales (mixed blood). Photo by Diamond” (Reed 1904b). Here, and in the preface it becomes clear that the photographs from Zambales were not taken by Worcester himself but by the photographer J. Diamond, in an aesthetic which very closely resembles that of Worcester. Reed fully agrees with Worcester’s vision on the “Negritos”. Employing a terminology typical for the racism of the period, Reed concludes the following with regard to the “mixture” of the “Negritos”/Aetas:

After all, Blumentritt’s opinion of several years ago is not far from right. Including all mixed breeds having a preponderance of Negrito blood, it is safe to say that the Negrito population of the Philippines probably will not exceed 25,000. Of these the group largest in numbers and probably purest in type is that in the Zambales mountain range, western Luzon (Reed 1904b).

In another photograph, he suggests that “mixed” “Negritos” are higher in stature and therefore a little closer to what he considers civilization.

The Ferdinand Blumentritt quoted here was a Bohemian teacher and arm-chair-anthropologist, who never visited the Philippines but maintained correspondence with Philippine’s national hero José Rizal and based his publications also on Spanish reports from the Philippines (Rice 2014, pp. 24–25; Weston 2020, p. 52). Blumentritt is one example of several, including Küppers-Loosen, which show how German and German-speaking anthropologists equally contributed to the distribution of a vision of the racialized Filipinos as culturally and corporally inferior (Weston 2020).

Figure 2.

Portrait of a young woman categorized as “German mestiza” by Worcester (No. 9032 RJM - 32c3 Index).

Figure 2.

Portrait of a young woman categorized as “German mestiza” by Worcester (No. 9032 RJM - 32c3 Index).

Accordingly, German mestizos on the Philippines were esteemed as being completely different than those of “Negritos.” This can be seen in the second photograph, which bears the RJM inventory number 9032 and the original Index number 32c3. Therefore, it is attributed to the “Mestizo” series in the subgroup “German mestizos”. Only three pictures and no introductory text make up this series. All three show the same young woman, first with her father and then twice alone. The captions state that the father is German and that his daughter was born “by a Spanish mestizo wife” (Worcester, p. 647) The terminology regarding the posture implies a similar terminology of anthropometry as the posture is termed as “full length.” However, the aesthetic of the picture is very different from the one of the “Negrito” woman above. The neatly coiffed daughter poses with a smile and an elaborate dress in a garden, slightly reclining herself on a chair. The white, long embroidered dress has a train and long flowing angel sleeves, the latter, as well as the pañuelo possibly of piña fabric. It has many elements typical of wealthy mestizas of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; also called traje del país, ‘country’s costume’. This is described by Coo as consisting of “baro with wide, flowing angel sleeves, pañuelo, and saya with no tapís.”5 It is safe to assume that this photograph was taken in circumstances were much less power hierarchies were involved as in the previous one.

The photographs of this “German mestiza” circulated much less widely than the photographs by “Negritos”; in fact, until now, I have found no publication of this photo. But in his main publication, Philippines Past and Present, a photograph of “a typical Spanish mestiza” is included, who wears a similar hairdo and attire in black (Worcester 1914, 938, Vol. II). The photograph is similar to a photograph by the contemporary Filipino photographer Felix Laureano entitled “la mestiza” published at the end of the Spanish colonial period (Laureano 1895, p. 106)

5 and the abovementioned sketch of a Spanish mestiza by Jagor (1873a, p. 184); the latter yet again showing similarities between German and US-depictions of the inhabitants of the Philippines. That this type of dress was indeed worn by many well-to-do mestizas of varying ancestry can be seen in the third photograph (cf.

Figure 3 and also (Coo 2019)), in which the woman wears a similar dress but of a dark tone.

5. The Vision of a Mestiza by a Local Photo Studio

This third picture is different from the previous two. Here, the posing for the photographer is less apparent which gives it the appearance of a snapshot; something very difficult to obtain with the technical possibilities of that time (Lederbogen 1990, 26–27). The depicted woman is seated in a slight angle to the camera and does not look at the photographer; contrary to the “German mestiza” she does not smile. She seems to be playing distractedly with an object in her bosom which could be a purse. Similar to the unnamed German mestiza, she wears earrings and additionally a necklace which probably shows a certain wealth. She sits on a bench and in front of a wall which seems to be made of bamboo; on the side of a window which blurrily shows the interior of a room, maybe a shop. Contrary to the previous photographs, this one contains a caption written in white on its front; “Chinese mestiza” on the lower left side and the number “549” together with a stylized monogram containing the letter “E” and “B”. Several photographs with inventory numbers close to this one contain similar inscriptions on the front side. Some of them are clearly studio portraits and some of them contain the inscription “Piang Studios” or “Dionysio Encinas”. The inscriptions indicate that the picture belongs to a series of numbered postcards, produced by a professional photographer. That the inscription is in English seems to indicate that they were produced for foreigners, probably mainly US tourists and other travelers who collected these types of postcards for their private collections and sometimes with academic intentions – just like Küppers-Loosen.

In the Philippines, photo studios proliferated in Manila, as outlined above. Much less is known for the studios outside Manila and on other islands such as Mindanao. From Wagner’s (2024) study on the photograph of the Bud Dajo Massacre, we know that there were several foreign photographers present, and that an US photographer had established himself in Mindanao. Harry Whitfield Harnish, an US private established a photo studio in Zamboanga, together with his wife Josephine Peas Barnes. They took photos at least between 1898 and 1907. They advertised their work with the slogan “For First-Class Filipino and Moro Views got to Mrs. H.W. Harnish's Gallery, the ONLY experienced Photographer and The ONLY Gallery in Zamboanga” (University of the Philippines L 1972, o.S.).

We know little about Piang Studio(s), but its photographs circulated widely in the US colonial era.5 According to Zhuang (2016, p. 317), it was located in Dulawan (near Cotabato), capital of the Buayan Sultanate in Mindanao. Zhuang presents some indicators that the studio might have been owned by Datu Piang (born 1850, died 1933), a powerful Muslim ruler of Maguindanao, datu of Cotabato, himself a mestizo born of a Muslim mother and a Chinese father who had learned photography from the US-Americans. He was so influential that the town Dulawan was later on renamed after him as Datu Piang.

On the photographs themselves, both from the RJM collection and from the Ortigas Foundation, there are inscriptions pointing to Piang studios with the additional inscription Zamboanga5 – and not Dulawan. This applies also to the photographs by Dionisio Encinas in the RJM collection which often bear the date 1905. There is also a photo by Encinas of Datu Piang himself (“No. 216 Datto Piang, Chief of the Cottabato Valley”, No. 9982 in the RJM). So maybe Zhuang is mistaken about the location of the studio or there existed two studios or maybe branches with the same name.

So, wherever the studio o studios where actually located, the photo of the mestiza was taken by a local photographer and commercialized. Therefore, this photograph is a good example for the above-mentioned types as a form of commodity. The Küppers-Loosen collection in the RJM shows that both photographs taken for (racist) “scientific” ends and those taken to be sold to tourists could end up in museums where they showed Europeans, in this case the inhabitants of the German city of Cologne, a specific image of the Philippines. It is unclear if some of Küppers-Loosen photographs were exhibited in the opening exhibition of the RJM which took place in 1906 (Geschichte des RJM). Worcester wrote to Küppers-Loosen in July 1907: „I am very glad to know that some at least of the prints arrived in time for the opening of the museum at Cologne so that visiting scientists were able to see them” (Worcester 1907, p. 34). However, in the first catalogue of the Museum, dating from 1910, no photographs are mentioned. The racist terminology employed in the catalogue, however, is fully in line with the opinions of Worcester (Foy 1910, pp. 260–62).

6. Conclusion

We can conclude that the apparent aesthetic uniformity in the most widely circulated types is not observable if we have a closer look at a broader part of photographic collections; in this case those of mestizos and mestizas in the Küppers-Loosen-collection of the RJM. However, the selection and the staging of the photographs made by Worcester and his crew put forward their racist theories. They selected mostly photographs of indigenous peoples, especially Aetas, both categorized as mixed and not-mixed (Rohde-Enslin 1999; Rice 2014). This obsession with “Negritos”/Aetas was shared by other contemporary anthropologists and travelers (Blumentritt 1892; Meyer and Schadenberg 1891; Reed 1904b; Vanoverbergh 1925; Perez 1904).

In the Philippines, under Spanish and US rule, as well as elsewhere on the globe, anthropometric photographic types were an important tool for racism. In this article, I have shown how professional photographers, local and foreign, researchers and colonial administrators elaborated and distributed photographic types. Previous studies have focused mostly on the stereotyped representation of indigenous groups which were indeed those most often portrayed and most widely distributed. But as I have shown, also mestizos and mestizas were included both in the theoretical and the visual taxonomic hierarchical system of racialization. The visual representation of these mestizos and mestizas was far from being uniform. The proposed (visual) systems of classifications were often incoherent and the nuances only understandable for viewers familiar with the theories of racism of that time. Especially if we look at unpublished photographs we can see that some mestizos and mestizas were represented as being supposedly close to indigenous peoples – and in this case they were, analogously, shown as – in varying degrees – being backward and uncivilized. This was the case of the anthropometric types elaborated by Diamond of a “Negrito” woman categorized by the US-administrator and zoologist Dean Worcester as “mixed blood”.

But Worcester and his crew also shot photographs of (German) mestizas which he considered as being close to Europeans in his racist terminology and which he showed as superior and cultivated. The aesthetic of these photographs is rather that of bourgeois portraits. These types of photographs were much less chosen to be published or shown at popular lantern shows in the US. In the Philippines, photos of both Chinese and Spanish mestizas were quite often published with this label. The postcard with a Chinese mestiza, probably shot and sold by a local photo studio, is an example for that; though the aesthetic of that picture is not among the most typical. While the mestizo/mestiza as a colonial categorization began to disappear under US rule, apparently it still had not lost its fascination, especially for Non-Filipinos.

Notes

This is why I, following the argumentation by Schaub (2019, pp. 109–13), I will not speak of “scientific” racism. Instead, I will sometimes use the term biologist racism to refer to its specific expressions in the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century.

He mentions the example of the wedding portrait of Josef and Mitzi Maier which an ethnographer later re-used as type by adding the caption “Upper Austrian bridal couple” (“Oberösterreichisches Brautpaar”).

She calls them physical types (“tipos físicos”) and popular types (“tipos populares”).

As Cánepa Koch (2018, p. 97) arguments for the German anthropologist Brüning in Peru, scholars furthermore employed and exchanged cartes de visites for personal purposes with their acquaintances.

Price List of Philippine Photographs for Sale by the Bureau of Science, Manila, P.I. (Effective February 1, 1912) (RJM) Not all of the 3352 photographs listed in the Index (named “catalogue” in the letters) Worcester sent to Küppers-Loosen are contained in the RJM collection. This is probably due to the fact that the prints were sent in several shipments to Küppers-Loosen. In one letter, it is mentioned that Küppers-Loosen possessed an “old copy of the catalogue” (Worcester 1906b, p. 22) and that the photographic prints sent to him with this letter were not listed in the catalogue but that he would receive a new catalogue. It is unclear whether the Index contained in the RJM collection is the “old” or “new” one since it is not dated. And in any case, it does not fully coincide with the photographs contained in the collection. Küppers-Loosen paid for 3,716 photographs from the collection of the Bureau of Science and it is unclear how many reached him. According to Rohde-Enslin (1999, p. 281) some photographs, among them of naked women, were lost after inventory. According to the current list, the RJM collection contains today 3,787 photographs of the Philippines, 3,781 of which are part of the Küppers-Loosen collection. Within that, 3,476 photographic prints were acquired from Worcester and his Bureau of Science. These date between 1887 and 1907. The RJM, after having acquired the positives in the early twentieth century, inventoried them, pasted the photographs on cardboard and added a handwritten German subtitle on the front and extracts from the English catalogue on the back, which later on was partly standardized in typewritten form. The German subtitles are normally abbreviated translations of the English catalogue’s description. In the process of inventory, the structure of the collection did no longer fully respect the structure of the Index. Rohde-Enslin digitalized 3,777 photographs (hese are the ones I worked with for this research) and elaborated a digital inventory in Excel which contains the corresponding 3,777 entries of prints and, among other information, their German subtitles and parts of the original English captions (Rohde-Enslin 1999, p. 4). In this digital inventory, no difference is made between the prints acquired from the Bureau of Science and others. Both the identification and the origin of the 304 (delta between 3,781 and 3,476) photographs which are part of the Küppers-Loosen collection but were not acquired from the Bureau of Science are unclear. Englehard and Rohde-Enslin (1997, p. 34) mention 150 photographs which belonged to Küppers-Loosen and were not acquired from the Bureau of Science. They mention, that some of the photographs might have been taken by Küppers-Loosen himself. Mark Rice (personal communication, 2022), who thoroughly analyzed the Michigan collections of Worcester’s photos is not entirely sure about the provenience of these photographs, but thinks that possibly Küppers-Loosen acquired them himself. Several of them apparently are postcards which were produced with commercial aims. It would not have been the first time that postcards were acquired by scholars and resignified for (pseudo-)scientific goals. Cf. (Cánepa Koch 2018, pp. 80–81). It is worth mentioning that also Encinas produced photographic “types”. An example is the photo numbered 10033 in the RJM catalogue. On the front of the photograph, the following caption is contained in white color “No. 229. - Yacan (Male). Native of Basilan Island, P.I. Encinas, Photo” (Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, p. 10033). The online Filipinas Heritage Library contains several dozens of Encinas / Piang studio photographs (Filipinas Heritage Library) as well as the Image Bank Database of the Ortigas Foundation (The Ortigas Foundation Library). Until now, I have found no other photographs with the label “mestizo” explicitly labelled as elaborated by Encinas/Piang Studios. The Filipinas Heritage Library published online more than 200 pictures with the label “mestizo” or “mestiza” by different authors, including one from the Worcester collection (Spanish mestiza ca. 1895). In the RJM collection, it is numbered 9009. The situation is similar for the Ortigas Foundation as well as for the American Historical Collection at the Rizal Library of the Ateneo de Manila University. In the German captions, the words “Mischblut” and “Mischling” are used indiscriminately, the term “Mestize” is only used in a separate row in the Excel sheet, most probably added by Rohde-Enslin. Coo (2019, pp. 180–90) tells us that “toward the end of the nineteenth century, the traje de mestiza, also loosely referred to in the present as the Maria Clara dress, became the standard dress for females of various social classes. In the context of the nationalist struggle and eventual revolution, this began to be referred to as the Filipino dress or traje del país”. In the case of the German mestiza shown here, the dress seems to have been a single piece and not consisted of a separate baro and saya. Also one of the first photographs from the Philippines, taken by the Dutch photographer Francisco van Camp with the title “Indigena de clasa rica (Mestiza Sangley-Filipina)”, dating from the year 1875, shows a woman in a similar dress (Go 2014) A considerable number of them forms part of the photographic collection of the Ortigas Foundation (The Ortigas Foundation Library) However, neither there nor in other archives in Manila, did I find much information about the studio. This is the case, for example of the photograph titled “No. 279. Moro man & wife, Dansalan, Mind [Mindanao], P. I.” (The Ortigas Foundation Library) The same applies for the photograph No. 9949 of the RJM titled “No. 195, Moro Spear Dance”.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I would like to thank the staff of the photographic archives consulted for this study, namely Lucia Halder, Caroline Bräuer and Martin Malewski in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne, Germany; as well as the staff of the Ortigas Foundation Library, the University of the Philippines Diliman Special Collections Section University Library and the American Historical Collection of Ateneo’s Rizal Library. I also would like to appreciate the support of the Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics of the University of Münster which funded my research in Manila. Last but not least I would like to thank Mark Rice for comments on a previous version of this article.

References

- Abinales, Patricio N. , and Donna J. Amoroso. State and Society in the Philippines; State and society in East Asia series; Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Albiez-Wieck, Sarah. Taxing Calidad: the Case of Spanish America and the Philippines. E-Journal of Portuguese History 2021, 19, 110–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius Ma., L. Cañete. Exploring Photography: A Prelude Towards Inquiries into Visual Anthropology in the Philippines. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 2008, 36, 1–14. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792638 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Anonymous. 1900. Souvenir from the Philippine Islands. Manila.

- Barros, Cristina, and Marco Buenrostro. ¡Las Once y Serenooo! Tipos Mexicanos. Sección de obras de historia. México, D.F. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Siglo XIX. 1994.

- Bean, Robert Bennett. The Racial Anatomy of the Philippine Islanders, Introducing New Methods of Anthropology and Showing Their Application to the Filipinos with a Classification of Human Ears and a Scheme for the Heredity of Anatomical Characters in Man; J.B. Lippincott Co.: Philadelphia, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Jonathan. Philippine Colonial Photography of the Cordilleras, 1860-1930.; Vibal Foundation: Quezon City, Philippines, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blumauer, Reinhard. Die Fotosammlung des Wiener Museums für Volkskunde als Knotenpunkt einer typologisierenden Bilderproduktion zwischen 1895 und 1918. In Gestellt: Fotografie als Werkzeug in der Habsburger-Monarchie; erscheint als Nachschrift zur Ausstellung "Gestellt. Fotografie als Werkzeug in der Habsburgermonarchie", die vom 29. April bis 30. 14 im Österreichischen Museum für Volkskunde in Wien gezeigt wurde; Edited by Herbert Justnik. Kataloge des Österreichischen Museums für Volkskunde Bd. 100. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde; Löcker; 2014; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blumentritt, Ferdinand. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Negritos: Aus spanischen Missionsberichten zusammengestellt von Prof. Ferd. Blumentritt. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin 1892, 27, 63–68. Available online: https://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN391365657_1892_0027 (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Burke, Peter. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence; Picturing history series; Reaktion Books: London, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Buscaglia-Salgado, José F. 2018. Race and the Constitutive Inequality of the Modern/Colonial Condition. In Critical Terms in Caribbean and Latin American Thought: Historical and Institutional Trajectories. Edited by Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel, Ben Sifuentes-Jáuregui, and Marisa Belausteguigoitia, First softcover. New Directions in Latino American Cultures. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 109–24.

- Calvo, Luis, and Miguel Semper-Puig. Introduction: Science and Colonialism. Culture & History Digital Journal 2023, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánepa Koch, Gisela. . . Imágenes móviles: Circulación y nuevos usos culturales de la colección fotográfica de Heinrich Brüning. In Fotografía en América Latina: Imágenes e identidades a través del tiempo y el espacio; Edited by Gisela Cánepa Koch and Ingrid Kummels; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, 2018; pp. 78–123. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda García, Rafael. Las Pinturas de Castas: Resignificación para la historia social en Nueva España. In Africanos y Afrodescendientes en la América Hispánica Septentrional: Espacios de Convivencia, Sociabilidad y Conflicto; Edited by Rafael Castañeda García and Juan C. Ruiz Guadalajara. San Luis Potosí: El Colegio de San Luis; 2020; pp. 459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, Frederick. The Philippine Problem (1898-1913); Little, Brown, and company: Boston, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Deborah. “Reproducing Nations: Types and Customs in Asia and Latin America, ca. 1800–1860.” An Interview with Natalia Majluf. Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas 2006, 39, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coo, Stephanie. Clothing the Colony; Ateneo de Manila University Press: Manila, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Englehard, Jutta Beate, and Stefan Rohde-Enslin. Unterwegs mit dem Werkzeug des ‚bösen Blicks‘: Spurensuche im Historischen Photoarchiv des Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museums. Kölner Museums Bulletin 1997, 4, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ermakoff, George. O Negro na Fotografía Brasileira do Século XIX; 2004; Rio de Janeiro: G. Ermakoff Casa Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Juan. “From Savages to Soldiers”: Igorot Bodies, Militarized Masculinity, and the Logic of Transformation in Dean C. Worcester’s Philippine Photographs. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 2023, 71, 245–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipinas Heritage Library. Available online: https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/4106 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Foy, W. Führer durch das Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum (Museum für Völkerkunde) der Stadt Cöln: Von Dr. W. Foy, Direktor des Museums, 3rd ed.; Druck der Kölner Verlagsanstalt A.-G: Cöln, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Geschichte des RJM: Kulturen der Welt. Available online: https://rautenstrauch-joest-museum.de/Geschichte (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Go, Nicholai David. Origins of Filipino Photography: An investigation into the different photography methods used by the Americans during their colonial occupation of the Philippines. 2014. Available online: http://www.nicholaigo.com/blog/2014/10/29/origins-of-filipino-photography (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Gonzalez Fernandez, Don Ramon. Manual del Viajero en Filipinas; Imprenta de Santo Tomás: Manila, 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford, E. History and description of the picturesque Philippines, with entertaining accounts of the people and their modes of living, customs, industries, climate and present conditions … By Adjutant E. Hannaford. The Crowell & Kirkpatrick Co.: Springfield, Ohio, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford, Ivan. Race: The History of an Idea in the West; Woodrow Wilson Center Press; John Hopkins University Press: Washington D. C., 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hight, Eleanor M., and Gary D. Sampson. Introduction: Photography, "Race" and Post-Colonial Theory. In Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)Ing Race and Place; Edited by Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson; Routledge: London, 2002; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, Vincent, and Maren Röger, eds. Völker verkaufen: Politik und Ökonomie der Postkartenproduktion im östlichen Europa um 1900; Sandstein Verlag: Dresden, 2023; Visuelle Geschichtskultur 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, Wulf D. Rassismus. In Enzyklopädie Philosophie: In drei Bänden mit einer CD-ROM; Edited by Hans J. Sandkühler, Dagmar Borchers, Arnim Regenbogen, Volker Schürmann, and Pirmin Stekeler-Weithofer; Meiner: Hamburg, 2010; pp. 2191–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, Wulf D., and Malina Emmerink. Rassismus und Kolonialismus. In Deutschland postkolonial? Die Gegenwart der imperialen Vergangenheit; Edited by Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst and Joachim Zeller; Metropol: Berlin, 2018; pp. 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, Jens. Bilder aus Afrika vor 1918: Zur visuellen Konstruktion Afrikas im europäischen Kolonialismus*. In Visual history: Ein Studienbuch; Edited by Gerhard Paul; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, 2006; pp. 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jagor, Fedor. Reisen in den Philippinen: Mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und einer Karte; Weidmann: Berlin, 1873a. [Google Scholar]

- Jagor, Fedor. Reisen in den Philippinen: Mit zahlreichen Abbildungen und einer Karte. 1873b. Available online: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000384B00000000.

- Jordán, Pilar García. A visual representation of Chiriguano in Torino missionary exposition, 1898. Hispania sacra: revista de historia eclesiástica 2016, 68, 735–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justnik, Herbert. "Volkstypen" - Kategorisierendes Sehen und bestimmende Bilder. In Visualisierte Minderheiten: Probleme und Möglichkeiten der musealen Präsentation von ehtnischen bzw. nationalen Minderheiten; Edited by Petr Lozoviuk; Thelem: Dresden, 2012; pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Justnik, Herbert. Volkstypen. Typisierende Massenbilder: Identifikation und Differenz im 19. Jahrhundert. Nachrichten. Volkskundemuseum Wien 2020, 55, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Imaging of Race in 18th-Century Mexico. Yale University Press: New Haven, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Landor, Arnold Henry Savage. The Gems of the East: Sixteen Thousand Miles of Research Travel Among Wild and Tame Tribes of Enchanting Islands; with Numerous Illustrations, Diagrams, Plans, and Map by the Author; in Two Volumes 2. Macmillan: London, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Laureano, Felix. Recuerdos de Filipinas: Album-libro; util para el estudio y conocimiento de los usos y costumbres de aquellas islas 1; López Robert: Barcelona, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Lederbogen, Jan. Die Fototechnik zur Zeit Enrique Brünings. In Fotodokumente aus Nordperu von Hans Heinrich Brüning (1848-1928); Edited by Corinna Raddatz; Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde: Hamburg, 1990; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, José Honorato. Album Vistas de las Filipinas y Trages de sus Abitantes. o.O. o.A. 1847. [Google Scholar]

- Majluf, Natalia. Pattern-Book of Nations: Images of Types and Costumes in Asia and Latin America, Ca. 1800-1860. In Reproducing Nations: Types and Costumes in Asia and Latin America, Ca. 1800-1860; Edited by Natalia Majluf; Americas Society: New York, 2006; pp. 15–56. [Google Scholar]

- Massé, Patricia. La mexicanidad popular según Cruces y Campa. Alquimia 2014, 51, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, Anne. Imperial leather: Race, gender and sexuality in the colonial contest; Routledge: New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mentges, Gabriele. Mode, Städte und Nationen: Die Trachtenbücher der Renaissance. In Mode: Kleider und Bilder aus Renaissance und Frühbarock; Edited by Jutta Zander-Seidel; Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseum: Nürnberg, 2015; pp. 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Adolf Bernhard, and Alexander Schadenberg. Album de Tipos Filipinos, Luzon Norte: Negritos, Tinguianes, Bánaos, Guinaanes, Silípanes, Calingas, Apoyáos, Quianganes, Igorrotes y Ilocanos. Cincuenta láminas con más de 600 tipos etnográficos reproducidos por medio de la fototipia. 1891. Available online: https://bvpb.mcu.es/es/consulta/registro.do?id=577440 (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Murillo Velarde, Pedro. Historia de la provincia de Philipinas de la Compañia de Jesus: segunda parte … desde el año de 1616 hasta el de 1716: Reproducción digital del original conservado en la Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Manila: en la Imprenta de la Compañia de Iesus, por D. Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay. 1749. Available online: https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/historia-de-la-provincia-de-philipinas-de-la-compania-de-jesus-segunda-parte-desde-el-ano-de-1616-hasta-el-de-1716 (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Olivares, Jose de. Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil. St. Louis N. D, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Onken, Hinnerk. Indigene und Eisenbahnen, Ruinen und Metropolen. Fotos und Bildpostkarten aus Südamerika im Deutschen Reich, ca. 1880-1930; Leibniz-Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam (ZZF): Potsdam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Onken, Hinnerk. Ambivalente Bilder: Fotografien und Bildpostkarten aus Südamerika im Deutschen Reich (1880-1930). Histoire 137; transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, Fr. Angel, ed. Relaciones Agustinianas de las razas del norte de Luzon. Department of the Interior - Ethnological Survey, Publications 3. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing. 22 January 1904. Available online: https://ia800605.us.archive.org/32/items/atf7592.0001.001.umich.edu/atf7592.0001.001.umich.edu.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Poole, Deborah. (1997). Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2021; Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History 13. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. (1992). Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation; London, New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum. The Philippine Collection at the RJM.

- Reed, William Allan. Negritos of Zambales.; Bureau of Public Printing: Manila, 1904a; Volume 2, Ethnological Survey publications 2,1. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, William Allan. Negritos of Zambales: The Project Gutenberg EBook; Bureau of Public Printing: Manila, 1904b. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, Kathrin. Indianerbilder: Fotografie und Wissen in Peru und im La Plata-Raum von 1892 bis 1910, 1. Aufl. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Mark. U.S., Asia, and the World: 1620-1914: Dean Worcester’s Photographs and American Perceptions of the Philippines. Education About Asia 2011, 16, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Mark. Dean Worcester's Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- RJM. Anhang unzugeordneter Dokumente. Originalakten zur historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinnen. Beschreibung der Fotos und Bildersien. RJM.

- Rodríguez Bolufé, Olga María. Imaginarios Racializados: Impresos sobre tipos cubanos del español Víctor Patricio de Landaluze durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 2021, 48, 115–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde-Enslin, Stefan. 1992. Östlich des Horizonts. Zugl. Heidelberg, Univ., Diss. u.d.T. Rohde-Enslin, Stefan: Beiträge deutscher Gelehrter zur Erforschung der Philippinen in den Jahren 1850 - 1900, Wurf-Verl, 1992.

- Rohde-Enslin, Stefan. 1999. Sammlung, Stereotyp und Struktur: Fotografische Stereotypisierungen im Kontext lokaler Ethnografie. Die Fotodokumentation des Bureau of Science aus der Frühzeit der US-amerikanischen Kolonialverwaltung in den Philippinen. Manuskript.

- Rojas Rabiela, Teresa, and Ignacio Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba. La diversidad étnica mexicana a mediados del Porfiriato. In Catálogo de la Colección de Antropología del Museo Nacional (1895): Edición facsimilar conmemorativa. Edición de teresa Rojas Rabiela e Ignacio Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba. Edited by Herrera, Alonso L., and Ricardo E. Cicero. Mexico, D.F. Secretaría de Cultura, INAH, CIESAS. 2018; 11–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sámano Verdura, Karina. El Indígena en la Fotografía: Tipos Físicos y Populares en el Siglo XIX en México. Alquimia 2014, 17, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, Jean-Frédéric. Race Is About Politics: Lessons from History; Princeton University Press.: Princeton, NJ, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer, Otto. 1905. In The Nabaloi-Dialect: The Bataks of Palawan by Edward Y Miller; B; Volume 2, Department of the Interior Ethnological Survey Publications Vol. 2, P. 2 and 3. Manila: Bureau of Public Pr.

- Sierra de la Calle, Blas. La fotografía en Filipinas 1845-1898. Archivo Agustiniano 2022, 106, 247–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish mestiza: Reproduction: Photograph. ca. 1895. Available online: https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/16602/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Tan, Antonio S. The Chinese Mestizos and the Formation of the Filipino Nationality. Archipel 1986, 32, 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ortigas Foundation Library. Image Bank Database. Available online: https://www.ortigasfoundationlibrary.com.ph/collections/image-bank-database (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Tolliver, Joyce. 'Dalagas' and 'Ilustrados': Gender, Language, and Indigeneity in the Philippine Colonies. In Unsettling Colonialism: Gender and Race in the Nineteenth-Century Global Hispanic World; Edited by N. M. Murray and Akiko Tsuchiya. SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian thought and culture; State University of New York: Albany, 2019; pp. 231–53. [Google Scholar]

- University of the Philippines, L. The Harry Whitfield Harnish collection.; UP Library: Manila, 1972; Research Guide 24. [Google Scholar]

- Uslenghi, Alejandra. Cartes-de-visite: el inconsciente óptico del siglo XIX. Revista de Estudios Hispánicos 2019, 53, 515–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wall, Hidde. Incompetent Masters, Indolent Natives, Savage Origins. In Savage Worlds; Edited by Matthew P. Fitzpatrick and Peter Monteath; Manchester University Press, 2018; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Vanoverbergh, Morice. Negritos of Northern Luzon. Anthropos 1925, 20, 148–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, Benito M. Displaying Filipinos: Photography and colonialism in early 20th century Philippines, 2nd pr.; University of the Philippines Pr: Quezon City, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Volpp, Leti. American Mestizo: Filipinos and Antimiscegenation Laws in California. U.C. Davis Law Review 2000, 33, 795–835. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=259930 (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Wagner, Kim A. Massacre in the clouds: An American atrocity and the erasure of history, 1st ed.; PublicAffairs: New York NY, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, Nathaniel Parker. Constructing Race and Rehearsing Imperialism: German Anthropologies of the Philippines, 1859 to 1885. ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY 2020, 11, 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Worcester, Dean C. Index to Photographic Prints. Originalakten zur historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinnen. Beschreibung der Fotos und Bilderserien. Teil 1. RJM.

- Worcester, Dean C. Index to Photographic Prints. Originalakten zur historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinnen. Beschreibung der Fotos und Bilderserien. Teil 2. RJM.

- Worcester, Dean C. 1906a. Letter to Georg Küppers-Loosen. Originalaken zur Historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinen. Schriftverkehr zwischen Herrn Worchester (Department of Interior, Manila) und Herrn Küppers-Loosen, 40 Seiten. RJM.

- Worcester, Dean C. 1906b. Letter to Georg Küppers-Loosen. Originalaken zur Historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinen. Schriftverkehr zwischen Herrn Worchester (Department of Interior, Manila) und Herrn Küppers-Loosen, 40 Seiten. RJM.

- Worcester, Dean C. 1907. Letter to Mr. Georg Küppers-Loosen, Rautenstrauch Joest Museum, Coln a/ Rhein, Germany. Originalaken zur Historischen Fotosammlung. Region Philippinen. Schriftverkehr zwischen Herrn Worchester (Department of Interior, Manila) und Herrn Küppers-Loosen, 40 Seiten. RJM.

- Worcester, Dean C. The Non-Christian Peoples of the Philippine Islands: With 32 Pages of Illustrations in Eight Colors. The National Geographic Magazine 1913, 14, 1157–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Worcester, Dean C. The Philippines, Past and Present: In Two Volumes II; Macmillan: New York, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Wubin. Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey; NUS Press: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).