1. Introduction

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is a partial or complete obstruction of blood flow through the portal vein (PV) due to an intraluminal thrombus. The first case of PVT was described by Balour and Stewart in 1868. Portal circulation accounts for two-thirds of liver blood supply; the hepatic arteries provide the remainder [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In 70% of PVT cases, local risk factors, like malignancy, focal inflammation, abdominal trauma, surgery, and cirrhosis, are present. Systemic risk factors are responsible for 30% of cases [

1,

4,

5]. The mechanisms by which the liver compensates for the loss of the portal blood supply are vasodilatation of the hepatic artery and developing venous collaterals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6]. HCC represents 90% of primary liver neoplasms and is the cause of death of more than one million patients worldwide every year. HCC staging is an essential factor in the treatment and prognosis. Portal vein invasion is a significant risk factor for postoperative tumor recurrence, and it is, therefore, contraindicated to perform transplantation, surgical resection, or percutaneous ablation, even in cases of a solitary lesion smaller than 5 cm [

2,

4,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Sometimes, the only sign of HCC is tumor PVT [

5,

10,

11,

13,

14]. HCC is most diagnosed using non-invasive radiological imaging and tumor markers. However, 30% of patients show normal levels of AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) at the time of the diagnosis, which can be observed even in the advanced stages of HCC [

15,

16]. Diagnosing a tumor PVT is relatively simple in patients whose liver mass is suggestive of HCC and PVT and whose opacities in the arterial phase (neovascularization) on CT or MRI. MRI portography is irreplaceable for identifying PVT, abdominal collaterals, and visceral organ changes [

17]. Portal vein diameter increase, wall irregularities, and arterial Color Doppler (CD) phenomena occurring in PVT are all highly suspicious of a malignant PVT [

10,

15,

18]. Reliable epidemiological data about PVT is often missing or hard to obtain [

3,

19]. The presence of tumor PVT in cases of HCC in the literature varies between 20-72% [

5,

8,

10,

15]. Sometimes, a tumor PVT biopsy is necessary for a precise assessment [

5,

20]. Percutaneous transhepatic fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of a tumor PVT was first described by Joly et al. in 1993 [

5]. A CORE needle biopsy (CNB) is a procedure performed using a hollow needle through which a tissue slice is obtained. Pathohistological, immunohistochemical, and molecular examinations can then be performed on the samples. We have completed three percutaneous ultrasound guided CNBs of PVT. We aim to present our experiences using this technique, its safety and effectiveness, and its clinical application.

2. Case Series:

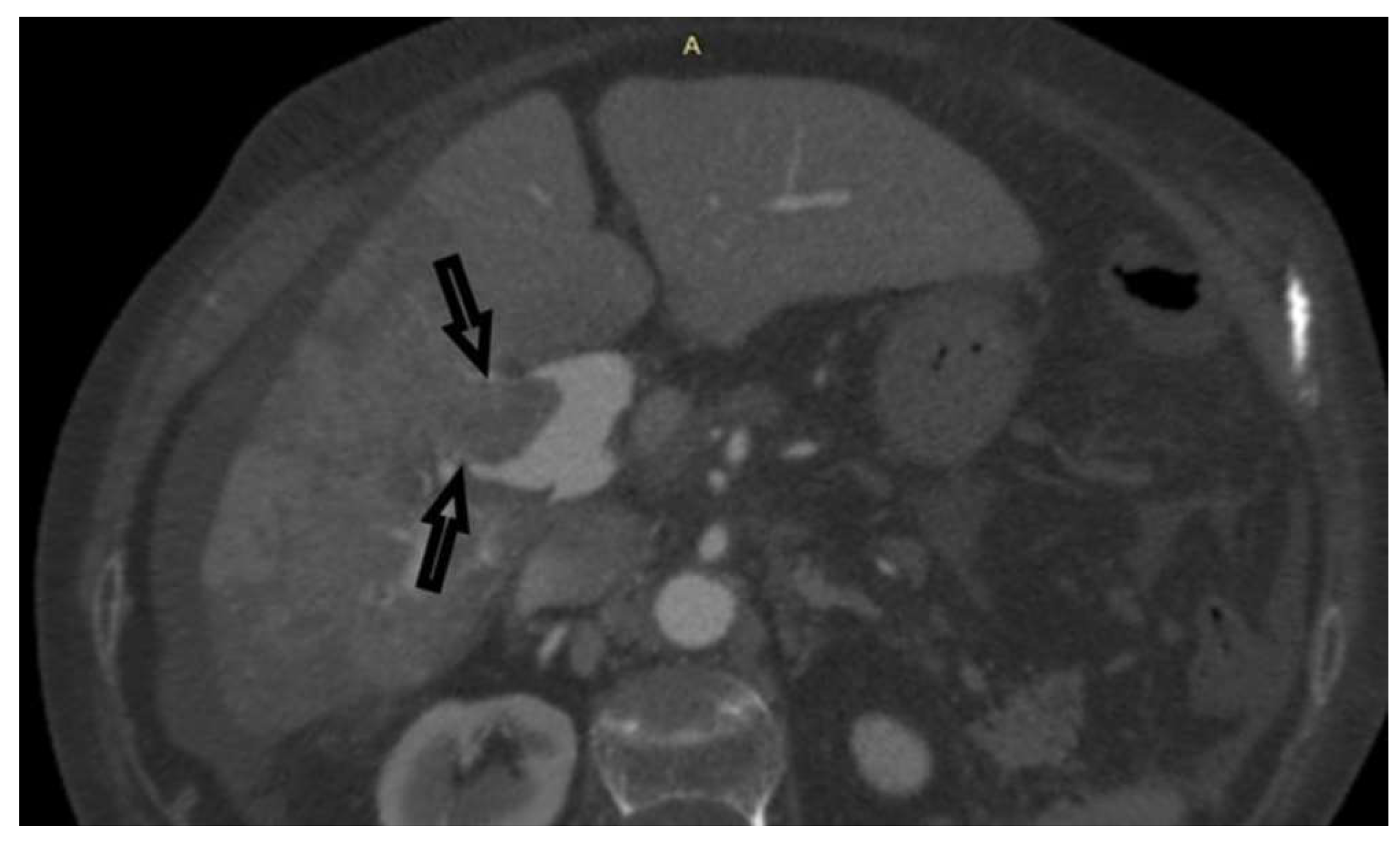

Case 1: A 72-year-old female, hospitalized for diarrhea and occasional abdominal pain for the last two months, followed by a loss of appetite and subsequent weight loss. PVT was detected ultrasonographically and in an enlarged, heterogeneous liver without a well-defined tumor mass. Abdominal MDCT has shown changes in the right liver lobe morphology, signs of PVT, ascites, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (

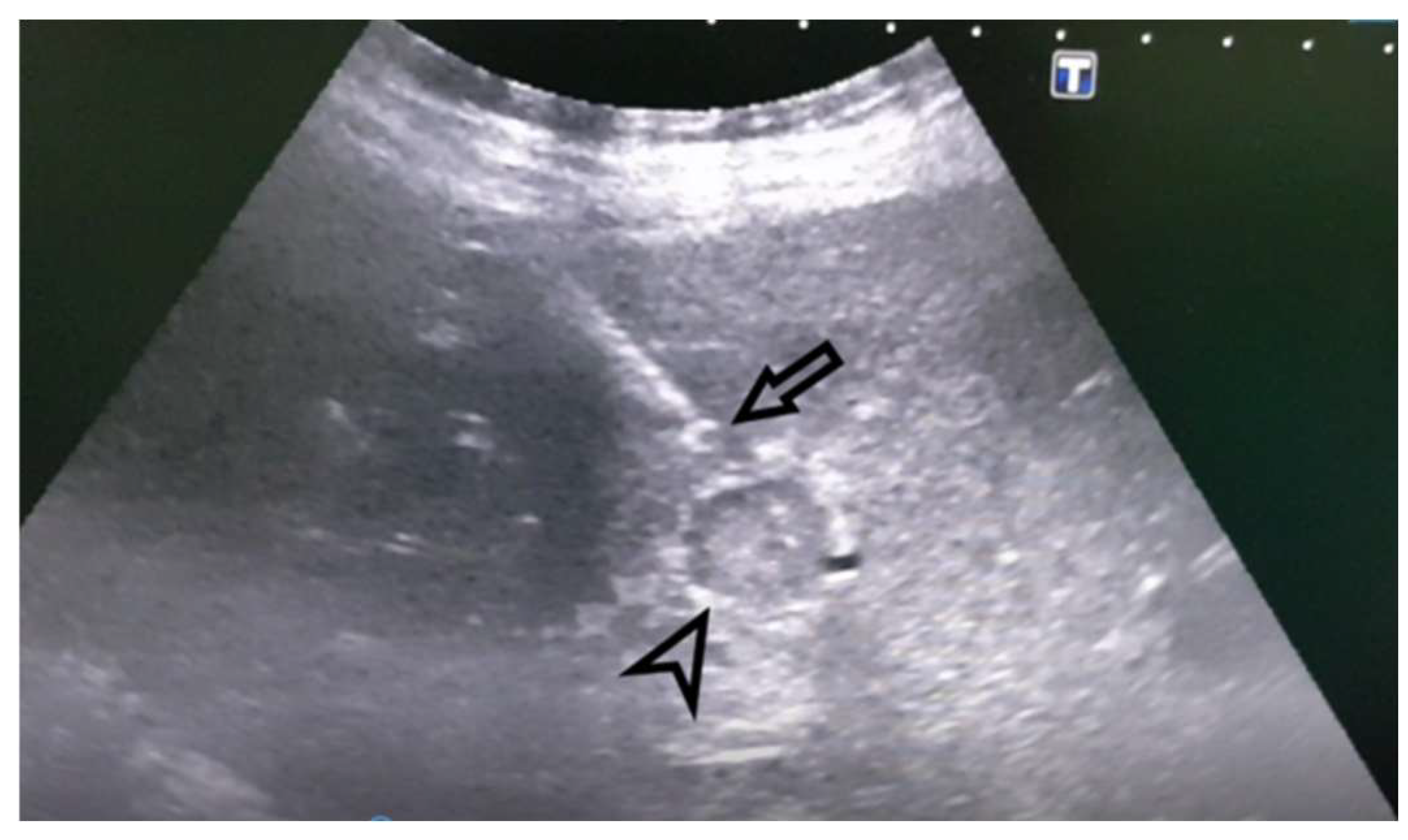

Figure 1). An MRI examination could not be performed due to the presence of the patient’s implants. AFP levels were significantly increased. A CNB was performed via the anterior abdominal wall, obtaining three samples from the right liver lobe, proximally to PV, and two pieces from the portal vein thrombus (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Pathohistological findings confirmed a poorly differentiated HCC in PVT samples. The other three samples did not provide any signs suggestive of HCC. Following a successful diagnosis, the oncological treatment could begin.

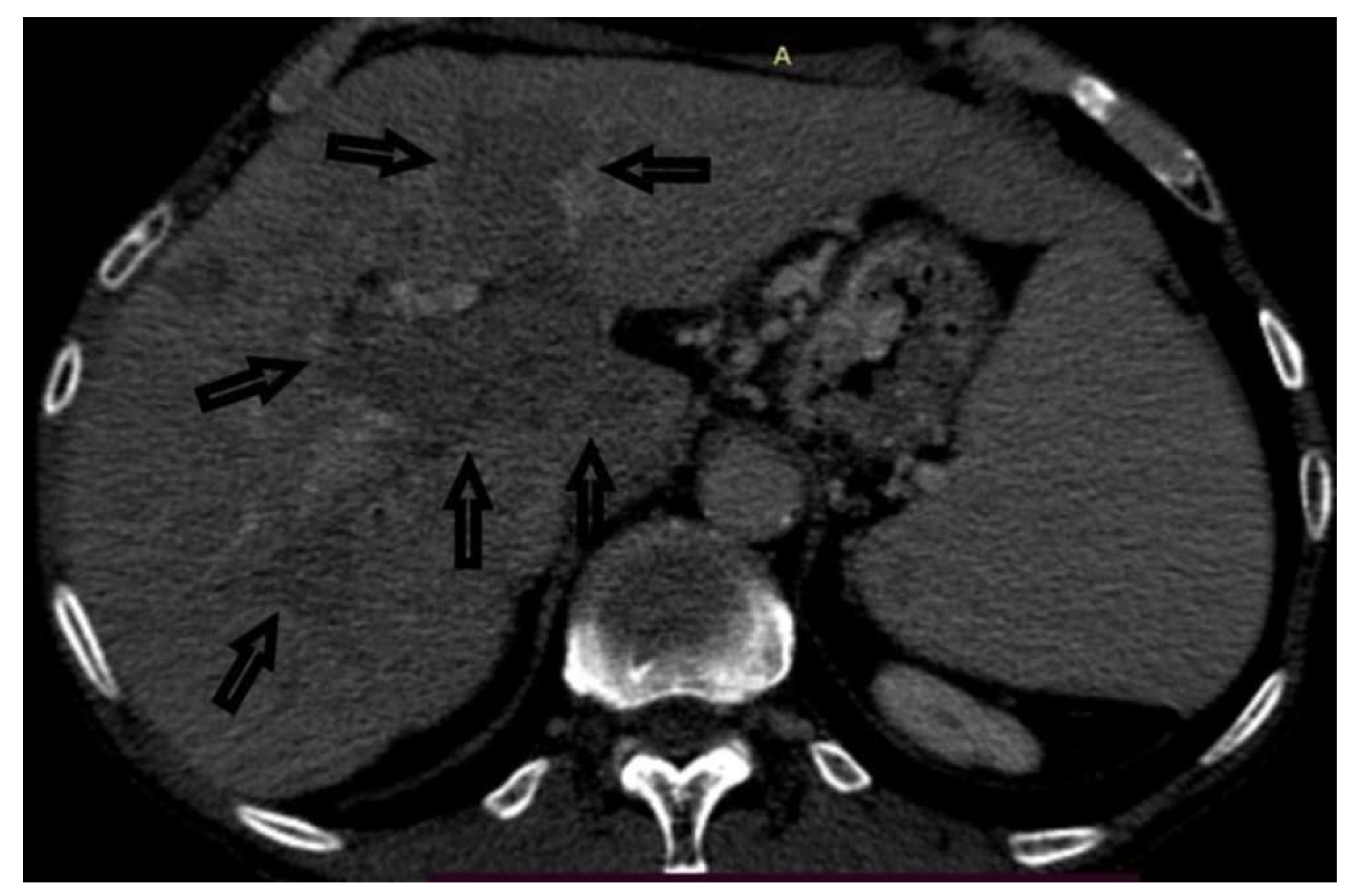

Case 2: A 66-year-old male was hospitalized to obtain a pathohistological verification of the existing liver lesions detected by an MDCT examination performed in a different institution. MDCT findings are dominated by a tumor PVT of the portal vein and its branches. No other signs of tumor masses could be detected. There was an apparent, intensive post-contrast enhancement in the arterial phase (a sign of neovascularization), followed by a rapid washout, highly suggestive of HCC (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). AFP levels were significantly increased. Ultrasonographically, the PVT was iso-hyperechoic compared to the surrounding liver parenchyma. Using Color Doppler imaging confirmed the absence of blood flow. A CNB was performed via the anterior abdominal wall, obtaining two samples from the tumor PVT in the left portal vein. Pathohistological findings were of a moderately-differentiated HCC-a typical histological subtype (

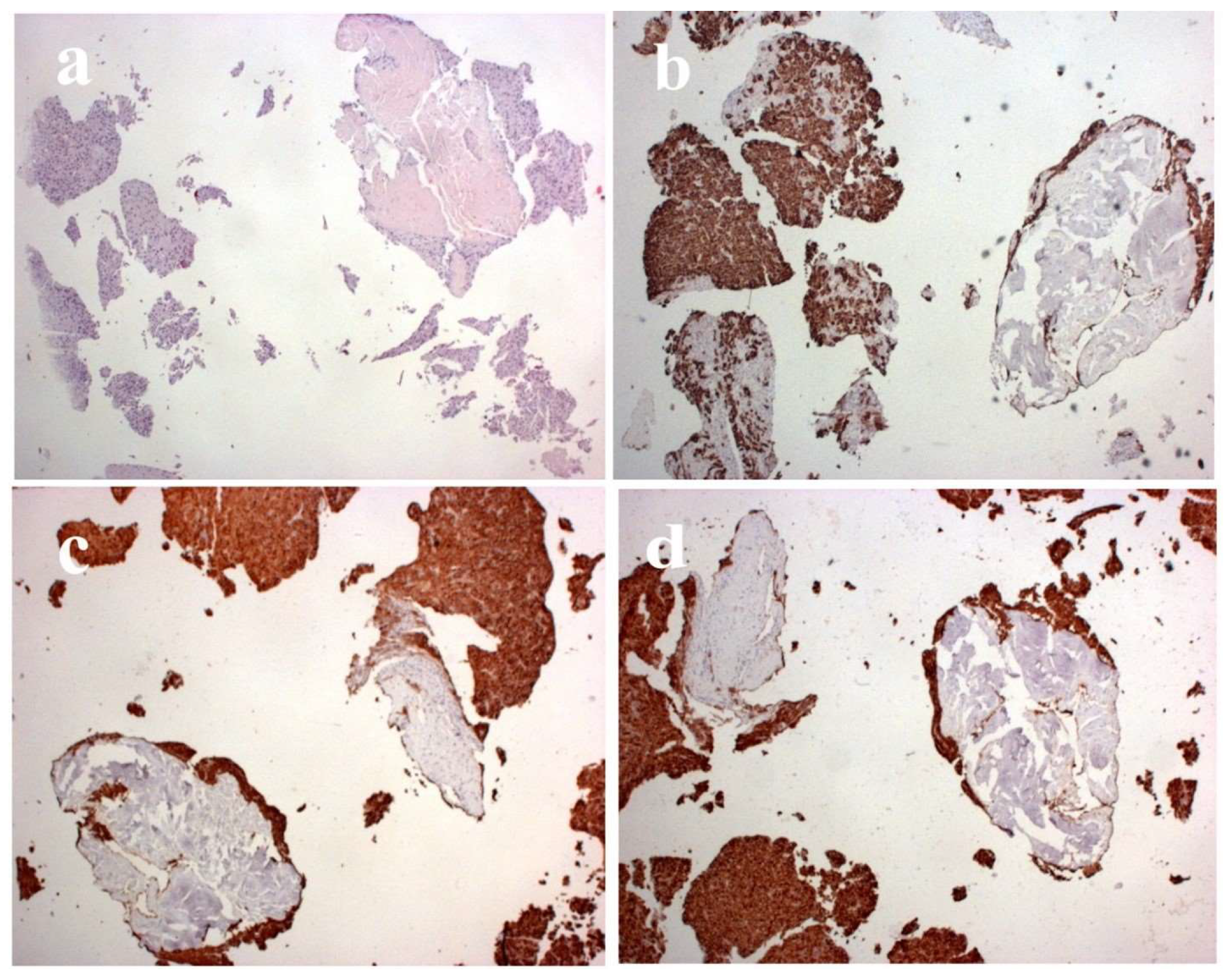

Figure 7).

Case 3: A female patient was hospitalized due to abdominal and leg swelling, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, appetite loss, and weight loss in the last month. Laboratory findings were non-specific: the levels of aspartate transaminase (AST), direct bilirubin, globulins, and C-reactive protein slightly increased. AFP levels were normal. Ascites and non-specific liver lesions were detected on the initial ultrasonography examination. An MDCT examination showed hypodense lesions in all phases, which are, in the arterial phase, surrounded by diffuse zones of transient attenuation differences (THAD). Ultrasonographically, PVT was iso-to-hypoechoic to the surrounding liver parenchyma. Two samples were obtained by performing a CNB of the left portal vein tumor PVT via the anterior abdominal wall (figure 6). A subsequent CNB of the left liver lobe was performed. Pathohistological analyses of the samples were performed, identifying an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC).

In these three cases, we have performed ultrasound-guided transhepatic CNB of the tumor PVT. All interventions were performed on the indications and technical principles from the available literature. All patients were hospitalized before the intervention. Informed consent was obtained from every patient for the performed procedures. Lidocaine was used for the local infiltrative anesthesia. 18G CNB needles were used for tumor PVT, 16G needles for other liver lesions, using CNB devices were BARD® MAGNUM® (United States of America) and Vigeo® V-Tek (Italy). Two needle passes were performed, obtaining two 1 mm thick, 5-10 mm long samples. The right PV was biopsied in one case, and the left PV in two cases. The models were adequate and conclusive for the pathohistological diagnosis. The patients tolerated the procedure well; there were no post-biopsy complications, no significant complaints regarding the policies, and all patients were hemodynamically stable. 12-18 hours after the intervention, follow-up ultrasound examinations were performed, showing no signs of complications. The diagnosis of HCC in two cases was confirmed, and ICC in one case. Following the pathohistological test, the palliative and chemotherapy of the patients were introduced.

3. Discussion

We have presented cases of patients with PVT whose clinical presentation was non-specific. Non-invasive imaging modalities were insufficient to provide a diagnosis. In one case, there were no liver lesions. In two cases, the lesions were non-specific and could not be visualized using ultrasound. For these reasons, the diagnosis was provided by a percutaneous PVT biopsy. CT sensitivity for PVT in patients with HCC varies between 68-100% [

10,

11]. HCC is an aggressive tumor that tends to grow through blood vessels, forming tumor thrombi in large containers [portal, hepatic vein]. Sometimes, a PVT is the only sign of tumor growth [

5,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14]. We could find only a single publication describing PVT core biopsies. In cases where imaging modalities cannot provide an accurate and reliable diagnosis, biopsy remains the only available diagnostic procedure, especially in the chances of a PVT being the only present sign or when the imaging findings are inconclusive or ambiguous, as presented in our case series [

5,

7,

10,

11,

14,

20].

Tumor PVT biopsy is different than other liver Core biopsies by the intentional puncture of the portal vein, which carries an increased risk of possible complications: portal vein or hepatic artery bleeding, bile duct laceration, biloma formation, biliary peritonitis, forming of a vasculobiliary or AV fistula, pseudoaneurysm. However, experience in other procedures in which the portal vein is accessed either intentionally or accidentally [percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, biliary drainage, percutaneous retrograde portography, percutaneous portal vein embolization, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt - TIPS], shows us that the portal vein and its surrounding structures could be punctured repeatedly and that the complications rarely occurred. It is logical, therefore, that it is possible to perform a tumor PVT biopsy without any significant complications. Careful planning of the needle route is necessary to avoid vital structures - the hepatic artery and other major blood vessels. To perform the biopsy safely, the patient's cooperation is essential; the coagulation parameters should be expected, using small-diameter biopsy needles, using a transhepatic route, and biopsying only the PVT [

8,

22].

There are arguments for performing a PVT biopsy, even in cases with a detectable liver mass, to minimize the difficulties of diagnosing a well-differentiated HCC. The presence of hepatocytes in a PVT sample is sufficient for diagnosing even a well-differentiated HCC [

7,

8,

22]. A tumor PVT Core biopsy should be performed in cases of complete PVT and distended tumor-filled portal vein. FNAB should be reserved for cases of incomplete PVT associated with small thrombi. Ultrasonographically, “coarse” or “nodular” images of the areas proximal to the tumor PVT could contain a “hidden” HCC [

5,

10], which we managed to prove in one case.

In the available literature, tumor PVT Core biopsy is rarely reported due to the procedure not being performed routinely, with FNAB being a more common biopsy method. Core biopsies are more dependent on the skill and experience of the operator. There are multiple reasons why this method did not become standard in diagnostics and staging of HCC with patients having tumor PVT: improvements in CT and MR diagnostics, shortage of well-trained interventional radiologists, and fear of possible complications [

7,

8,

16]. Complications during a transabdominal tumor PVT Core biopsy are more likely in obese patients if ascites are present or if there is a considerable distance between the skin and the lesion, sometimes exceeding 20-25 cm. In some cases, inadvertently sampling the surrounding liver tissue can be responsible for false positive results [

5]. False-negative results can be obtained if no malignant hepatocytes are in the tested thrombus part. To reduce the likelihood of false negatives, the samples are taken as close to the hepatic mass as possible [if it is detectable]; also, the most extended PVT segment should be chosen for the biopsy [

10,

22]. Due to its perpendicular orientation to the anterior abdominal wall, the left portal vein enables the largest possible segment of PVT to be sampled. To obtain a sample from the right portal vein, it is entered tangentially, and the model is obtained by increasing the needle puncture depth [

22]. In one case, the right portal vein was biopsied; the left portal vein was biopsied in the other two cases. Left portal vein biopsies were performed using a longer route through the PVT; right portal vein PVT was biopsied using the most tangential way. The sensitivity of FNAB in PVT differential diagnosis is 76-100% [

10]. In cases of a subcapsular lesion, a PVT is far safer than a biopsy of the primary lesion [

20]. Percutaneous tumor PVT biopsy is a reliable, quick, and well-tolerated procedure. The risks of a carefully performed procedure are comparable to the risks of an intrahepatic HCC biopsy. More publications are necessary to understand PVT better and to dispel doubts.

5. Conclusions

Our research indicates that percutaneous biopsy, as a minimally invasive procedure, provides a precise histological diagnosis, significantly contributing to improved diagnostic accuracy and appropriate therapeutic decision-making. This method has proven to be a useful tool in clinical practice, enabling timely identification of HCC even in the absence of obvious radiological signs, thereby improving prognosis and the possibility of adequate treatment for patients with tumor thrombus in the portal vein.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V., M.M.,,N.Z., and V.R; methodology, Dj.K., M.M. and M.V; software, C.I.,R.O.,K.D.,P.B. and G.J.; validation, M.B., Dj.K. and C.I.; formal analysis, C.I., P.M., R.I. and S.B,C.I.; investigation, J.J., Z.T., J.J. and V.M; resources, Z.J.,T.Z.,N.P. and V.M; data curation, S.B.,J.J. and M.B; writing—original draft preparation, V.M., M.M., and P.T. a writing—review and editing, V.M. and M.M.; visualization, R.I.,P.M.,S.S. and P.N; supervision, R.V.; project administration, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscriptFunding: This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained as a part of a routine procedure during the time of admission to our university hospital, for publishing future research purpose.

Data Availability Statement

All data can be found in University Clinical Centre Kragujevac, 34000, Kragujevac, Serbia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Campanale C, Rinninella E, Tortora A, Di Maurizio L, Bombardieri G, De Cristofaro R, De Gaetano AM, Landolfi R, Gasbarrini A. Portal vein thrombosis: insight into physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16(2):143-155. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Sharma P, Arora A. Review article: portal vein obstruction--epidemiology, pathogenesis, natural history, prognosis and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.2015; 41(3):276-292. [CrossRef]

- Wani ZA, Bhat RA, Bhadoria AS, Maiwall R. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and portal vein thrombosis in special situations: Need for a new classification. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21(3):129-138. [CrossRef]

- Hanafy AS, Tharwat EE. Differentiation of malignant from non-malignant portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis: the challenging dilemma. Egypt Liver J. 2021; 11:90. [CrossRef]

- Eskandere D, Hakim H, Attwa M, Elkashef W, Altonbary AY. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of portal vein thrombus in the diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Endosc. 2021; 54(5):745-753. [CrossRef]

- Arora A, Sarin SK. Multimodality imaging of primary extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EPHVO): what every radiologist should know. Be J Radiol. 2015; 88(1052):20150008. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami S, Rammohan A, Sathyanesan J, Palaniappan R. Ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of portal vein thrombus: a novel diagnostic and staging technique for occult hepatocellular carcinoma.Arch Clin Exp Surg.2014; 3(2):129-132. [CrossRef]

- Michael H, Lenza C, Gupta M, Katz DS. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of a portal vein thrombus to aid in the diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol.2011; 7(2):124-129.

- Gomez-Puerto D, Mirallas O, Vidal-González J, Vargas V. Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus extends to the right atrium and portal vein: A case report. World J Hepatol. 2020; 12(11):1128-1135. [CrossRef]

- Sparchez Z, Radu P, Zaharia T, Kacso G, Diaconu B, Grigorescu I, Badea R. B-mode and contrast enhanced ultrasound guided biopsy of portal vein thrombosis. Value in the diagnosis of occult hepatocellular carcinoma in liver cirrhosis. Med Ultrason. 2010; 12(4):286-294.

- Tarantino L, Ambrosino P, Di Minno MN. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in differentiating malignant from benign portal vein thrombosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol.2015; 21(32):9457–9460. [CrossRef]

- Vilana R, Bru C, Bruix J, Castells A, Sole M, Rodes J. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of portal vein thrombus: value in detecting malignant thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol.1993; 160(6):1285-1287. [CrossRef]

- Mutai J, Nebayosi T, Sande J, Shah MV. Isolated portal venous hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer.2017; 48(1):80-82. [CrossRef]

- deSio I, Castellano L, Calandra M, Falzarano IR, Zeppa P. Diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma by fine needle biopsy of portal vein thrombosis. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1992; 24(2):75-76.

- Kayar Y, Turkdogan KA, Baysal B, Unver N, Danalioglu A, Senturk H. EUS-guided FNA of a portal vein thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pan Afr Med J. 2015; 21:86. [CrossRef]

- Kantsevoy S, Thuluvath PJ. Utility and safety of EUS-guided portal vein FNA. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 7(2):123-131.

- Pargewar SS, Desai SN, Rajesh S, Singh VP, Arora A, Mukund A. Imaging and radiological interventions in extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. World J Radiol. 2016;8(6):556-570. [CrossRef]

- Tarantino L, Francica G, Sordelli I, Esposito F, Giorgio A, Sorrentino P, de Stefano G, Di Sarno A, Ferraioli G, Sperlongano P. Diagnosis of benign and malignant portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: color Doppler US, contrast-enhanced US, and fine-needle biopsy. Abdom Imaging. 2006; 31(5):537-544. [CrossRef]

- Rajani R, Björnsson E, Bergquist A, Danielsson A, Gustavsson A, Grip O, Melin T, Sangfelt P, Wallerstedt S, Almer S. The epidemiology and clinical features of portal vein thrombosis: a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 32(9):1154-1162. [CrossRef]

- Wachsberg RH, Handler BJ. Biopsy of portal vein thrombus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994; 162(4):1002. [CrossRef]

- De Sio I, Castellano L, Calandra M, Romano M, Persico M, Del Vecchio-Blanco C. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis: results in 15 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995; 10(6):662-665. [CrossRef]

- Dodd GD 3rd, Carr BI. Percutaneous biopsy of portal vein thrombus: a new staging technique for hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol.1993; 161(2):229-233. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).