Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

20 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

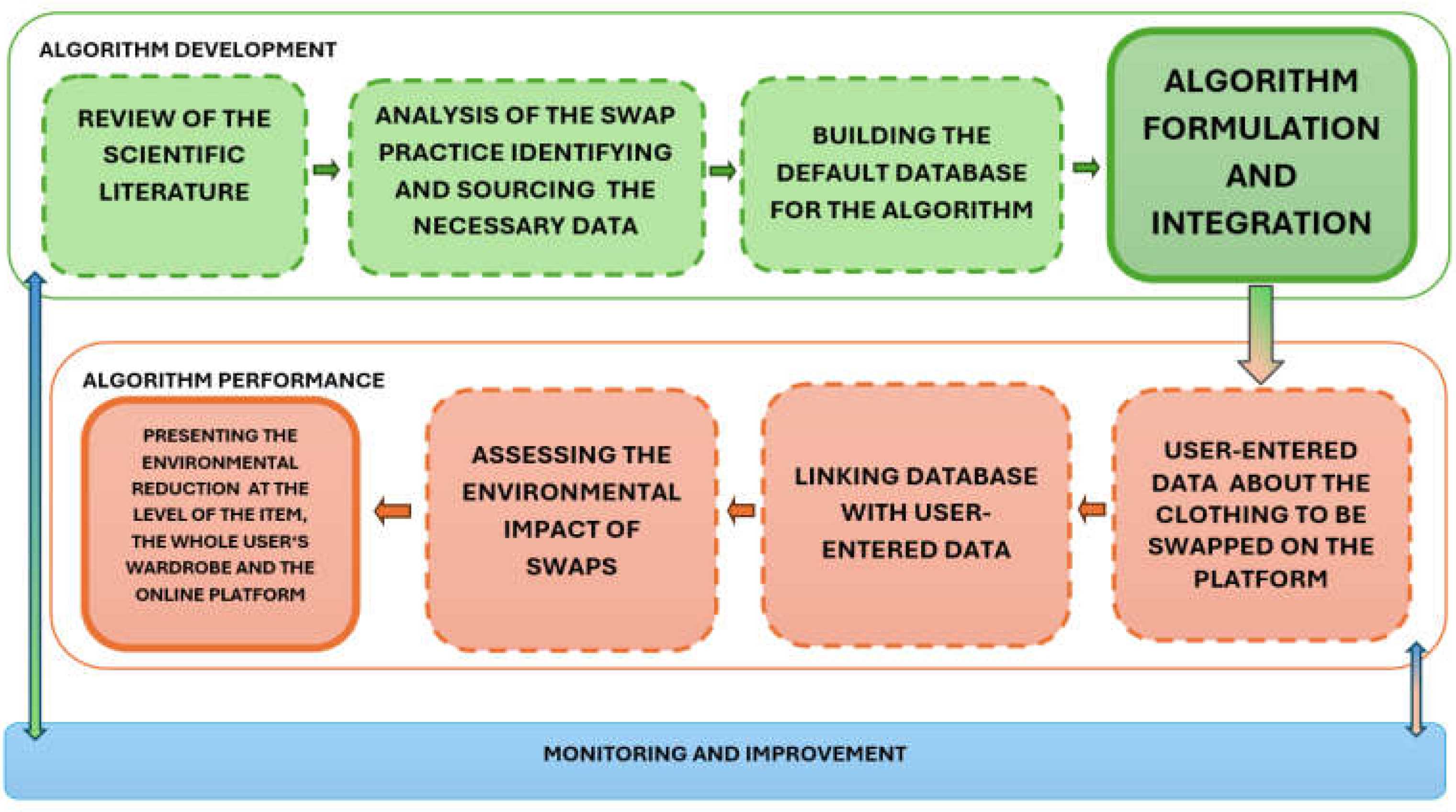

2.1. Algorithm Development

2.1.1. Review of Scientific Literature

2.1.2. Analysis of the Swapping Practice

2.1.3. Development of Algorithm Database with Default Data

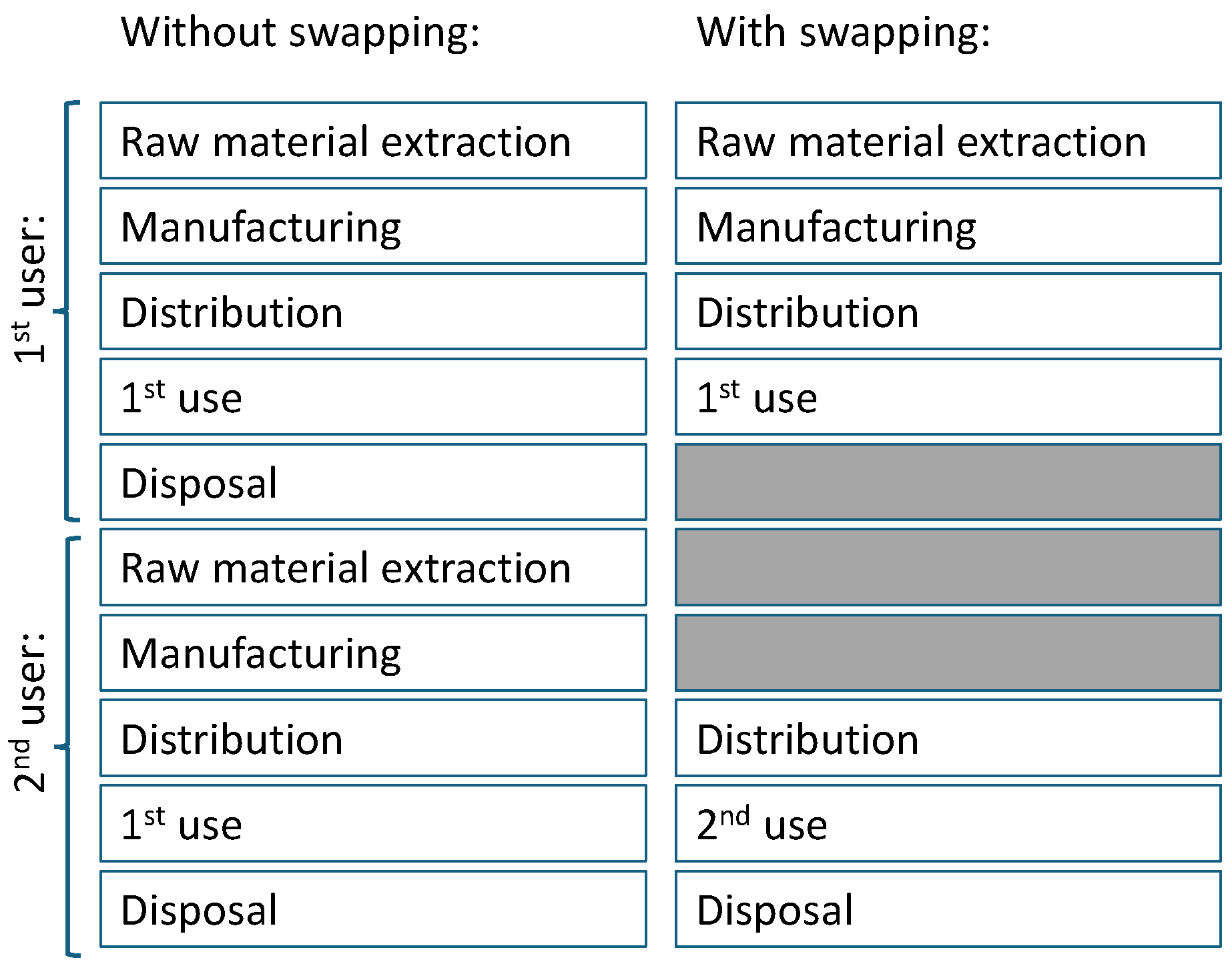

- Data were collected for the default database based on scientific literature;

- o

- the environmental impact of 1 kg of new fabrics (covering raw materials extraction, production, distribution and retail, first use, and EOL lifecycle stages);

- o

- the environmental impact of 1 kg of swapped fabrics during their use stage. The environmental impact of the swapped garment occurs only during its secondary use stage, and with each new owner, the wear time decreases by 33 percent, which also reduces the frequency of washings [49];

- o

- clothing transportation back and forth to the store or swapping point and home is included into the first and second use lifecycle stages; distribution and retail include transportation to retail store;

- o

- the use, in addition to the mentioned transportation to and from the store or swap, includes washing, drying and ironing.

2.1.4. Algorithm formulation

2.2. Algorithm Performance

3. Results

3.1. The Development and Implementation of Algorithm

3.1.1. Review of Scientific Literature

- Carbon Footprint: Production processes, particularly those using fossil fuels, significantly contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Materials like polyester, but also conventional cotton, are notable for their high carbon outputs during manufacturing and processing phases;

- Water Consumption: The textile industry is water-intensive, especially in the cultivation of cotton and the processing phases like dyeing and finishing or home washing which can lead to water scarcity and pollution;

- Energy Consumption: From manufacturing to consumer care, energy demand is substantial. Synthetic fibers and inefficient laundering practices increase the energy footprint dramatically;

- Land Use: Cultivation of natural fibers like cotton and viscose production requires considerable land, impacting land availability and health through pesticide and fertilizer use.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Swapping Practice

- The clothing category and weight – the weight depends on the category, and the amount of fabric in the garment depends on the weight;

- The number of wear cycles for both new and used clothing – this affects the number of washes, ironing, and drying cycles, which in turn impacts the environmental effect during the use phase of the life cycle;

- The condition of the cloth being swapped – both unused and used clothes could be swapped;

- How the swapped clothing was acquired – whether it was purchased new or used. If purchased new, after the swap, it is passed to the second owner; if purchased second-hand, it is passed to at least the third owner;

- The environmental impact assessment results of the fabrics to evaluate the environmental savings in both new and used clothing contexts.

3.1.3. The Developed Algorithm Database

3.1.4. The Formulated Algorithm

(IRawMat+IManuf+IDistr+INewUse+IEOL) – (ISwappedDistr+ISwappedUse) = INW – ISW

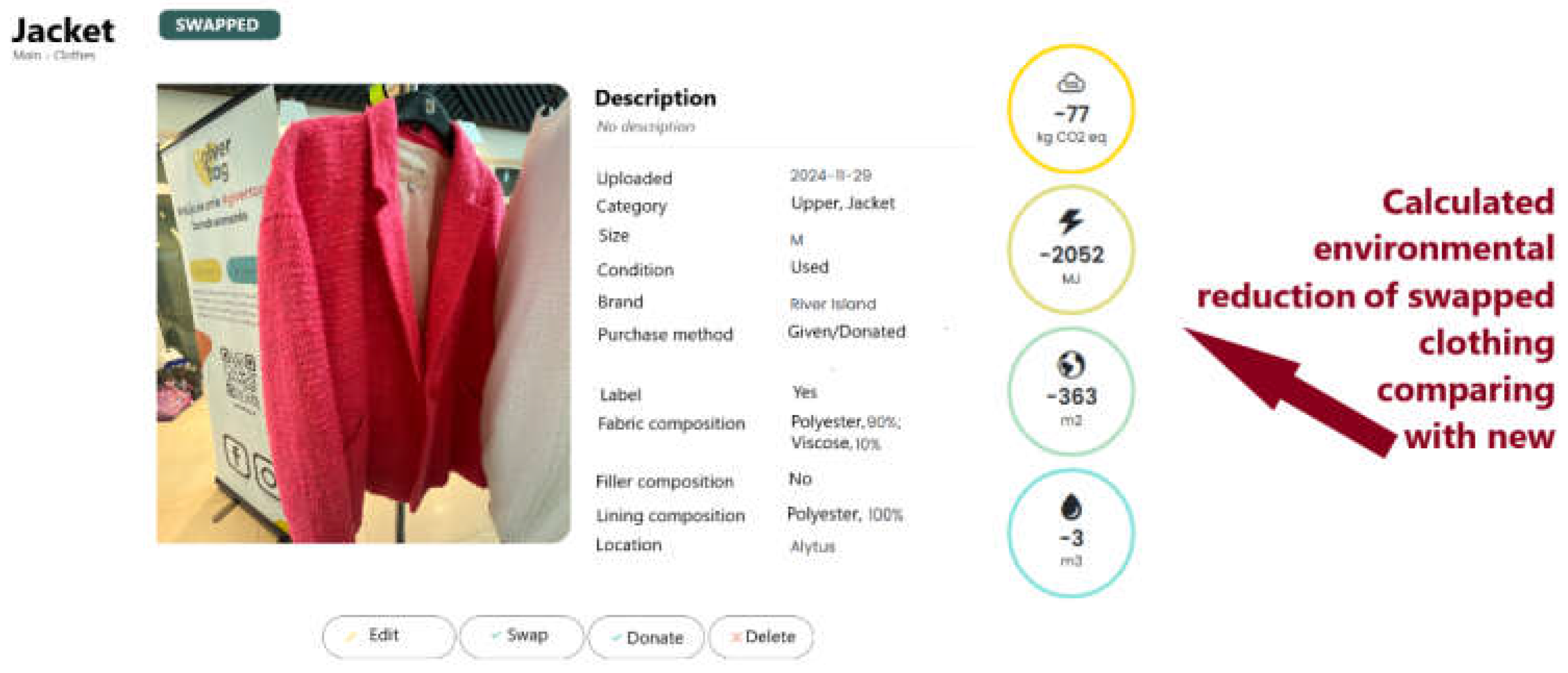

3.2. Algorithm Performance to Calculate Environmental Impact Using the Developed Algorithm Implemented at an Online Clothing Swapping Platform

4. Discussion

- Carbon footprint: a cotton dress saves 98 kg CO2 eq;

- Energy consumption: a silk dress saves 2858 MJ;

- Land occupation: silk and natural leather dresses save 1750 m2a crop eq and 5000 m2a crop eq, respectively;

- Water consumption: a cotton and silk dresses save 10 m3 and 9 m3, respectively.

- Carbon footprint: wool and silk dresses save 1 kg CO2 eq and 64 kg CO2 eq, respectively;

- Energy consumption: natural leather dress saves 507 MJ;

- Land occupation: wool dress saves 84 m2a crop eq;

- Water consumption: wool (2 m3), viscose (3 m3), polyester (3 m3), and linen (4 m3) dresses.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CED | Cumulative Energy Demand |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| EOL | End of Life |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

References

- ETC/CE. Textiles and the Environment The Role of Design in Europe’s Circular Economy, 2022. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-ce/products/etc-ce-products/etc-ce-report-2-2022-textiles-and-the-environment-the-role-of-design-in-europes-circular-economy (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Yılmaz, K.; Aksu, I.O.; Göçken, M.; Demirdelen, T. Sustainable Textile Manufacturing with Revolutionizing Textile Dyeing: Deep Learning-Based, for Energy Efficiency and Environmental-Impact Reduction, Pioneering Green Practices for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakantonaki, S.; Kiskira, K.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Chronis, I.; Coelho, F.; Togiani, A.; Kalkanis, K.; Priniotakis, G. A Review of Sustainability Standards and Ecolabeling in the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzem, S.; Crossin, E.; Daver, F.; Wang, L. Environmental Impact of Apparel Supply Chain and Textile Products. Environ Dev Sustain 2022, 24, 9757–9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.G.; Biggs, L.; Nebel, B.; Bauch, K.; Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Swan, P.G.; Watson, K. Environmental Impacts Associated with the Production, Use, and End-of-Life of a Woollen Garment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2020, 25, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofeast. Lifecycle Impact on the Environment of Textiles and Garments [Analysis], 2023. Available online: https://www.sofeast.com/resources/green-manufacturing/lifecycle-impact-on-environment-of-textiles-garments/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Gonzalez, V.; Lou, X.; Chi, T. Evaluating Environmental Impact of Natural and Synthetic Fibers: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, G.; Ciliz, N.; Mammadov, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton Textile Products in Turkey. Resour Conserv Recycl 2015, 104, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, H.; Hou, H.; Shao, · Shuai; Sun, X.; Qin, C.; Zhang, S. Improved Design for Textile Production Process Based on Life Cycle Assessment. Clean Technol Environ Policy 2018, 20, 1355–1365. [CrossRef]

- Kishor, R.; Purchase, D.; Saratale, G.D.; Saratale, R.G.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Bilal, M.; Chandra, R.; Bharagava, R.N. Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Persistent Coloring Pollutants of Textile Industry Wastewater and Treatment Approaches for Environmental Safety. J Environ Chem Eng 2021, 9, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; An, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, B.; Ding, J.; Ye, C.; Xu, Y. Microfiber Pollution in the Earth System. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2022, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Subramanian, R.B. Synthetic Textile and Microfiber Pollution: A Review on Mitigation Strategies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 41596–41611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, J.K.; Friot, D.; Jolliet, O.; Erkman, S. A Spatially Explicit Life Cycle Inventory of the Global Textile Chain. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2009, 14, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, S.S. Environmental Impacts of the Use Phase of the Clothing Life Cycle. In Handbook of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Textiles and Clothing, Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, Muthu, S.S., Eds.; Elsevier / Woodhead Publishing, 2015, pp. 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, X.; Ding, X. Environmental Impacts of Textiles in the Use Stage: A Systematic Review. Sustain Prod Consum 2023, 36, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koligkioni, A.; Parajuly, K.; Sørensen, B.L.; Cimpan, C. Environmental Assessment of End-of-Life Textiles in Denmark. Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Goel, A. Design of the Supply Chain Network for the Management of Textile Waste Using a Reverse Logistics Model under Inflation. Energy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, D.S.; Bosomoiu, M.; Stefan, M. Methods for Natural and Synthetic Polymers Recovery from Textile Waste. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubik, F.; Nebel, K.; Klusch, C.; Karg, H.; Hecht, K.; Gerbig, M.; Gärtner, S.; Boldrini, B. Textiles on the Path to Sustainability and Circularity—Results of Application Tests in the Business-to-Business Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummino, M.L.; Varesano, A.; Copani, G.; Vineis, C. A Glance at Novel Materials, from the Textile World to Environmental Remediation. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 2826–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, T.; Li, Z.; Hong, J. Carbon–Water–Energy Footprint Impacts of Dyed Cotton Fabric Production in China. J Clean Prod 2024, 467, 142898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Ramalho, E.; Gouveia, A.; Henriques, R.; Figueiredo, F.; Nunes, J. Systematic Insights into a Textile Industry: Reviewing Life Cycle Assessment and Eco-Design. Sustainability 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abagnato, S.; Rigamonti, L.; Grosso, M. Life Cycle Assessment Applications to Reuse, Recycling and Circular Practices for Textiles: A Review. Waste Manag 2024, 182, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Hasan, A.K.M.M.; Bhuiyan, M.A.R.; Bhat, G. Evaluation of Environmental Impacts of Cotton Polo Shirt Production in Bangladesh Using Life Cycle Assessment. Sci Total Environ 2024, 172097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM(2022) 141 final EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0141 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- COM/2020/98 final Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A New Circular Economy Action Plan For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1583933814386&uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Gray, S.; Druckman, A.; Sadhukhan, J.; James, K. Reducing the Environmental Impact of Clothing: An Exploration of the Potential of Alternative Business Models. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furferi, R.; Volpe, Y.; Mantellassi, F. Circular Economy Guidelines for the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, P.; Scheffer, M.; Bos, H. Textiles for Circular Fashion: The Logic behind Recycling Options. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.; Biggs, L.; Nguyen, Q. Van; Clarke, S.J.; Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Reducing Environmental Impacts from Garments through Best Practice Garment Use and Care, Using the Example of a Merino Wool Sweater. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Henry, B. Does Use Matter? Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Clothing Based on Fiber Type. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwozdz, W.; Steensen Nielsen, K.; Müller, T. An Environmental Perspective on Clothing Consumption: Consumer Segments and Their Behavioral Patterns. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Jacobs, B.; Taljaard-Swart, H. I Rent, Swap or Buy Second-Hand – Comparing Antecedents for Online Collaborative Clothing Consumption Models. Int J Fash Des Technol Educ 2023, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Lang, C.; Kujala, S. A Use-Oriented Clothing Economy? Preliminary Affirmation for Sustainable Clothing Consumption Alternatives. Sustainable Development 2016, 24, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, H.; Fahy, F. Unlocking Insights in the Everyday: Exploring Practices to Foster Sustainable Maximum Use of Clothing. Clean Respons Consum 2023, 8, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I. Clothing Reuse: The Potential in Informal Exchange. Clothing Cultures 2017, 4, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Lynes, J.; Young, S.B. Fashion Interest as a Driver for Consumer Textile Waste Management: Reuse, Recycle or Disposal. Int J Consum Stud 2017, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RREUSE CO2 Emissions Calculator. Available online: https://rreuse.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Charitable Reuse Australia Consumer Donations Calculator. Available online: https://www.charitablereuse.org.au/reusecalculator/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- TEXCYCLE Textile Eco Calculator. Available online: https://texcycle.bg/en/eco-calculator/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- ThreadUP TreadUp. Available online: https://www.thredup.com/fashionfootprint/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- GreenStitch. Personal Fashion GHG Footprint Calculator. Available online: https://greenstitch.io/personal-footprint-calculator (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Selfless Clothing Sustainability Rank. Available online: https://www.selflessclothes.com/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Givertag Apie Mus Available online:. Available online: https://givertag.lt/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- ISO. Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Requirements and Guidelines. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- SimaPro About Us. Available online: https://simapro.com/meet-the-developer/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Ecoinvent Ecoinvent Version 3.8. Available online: https://support.ecoinvent.org/ecoinvent-version-3.8 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I. Clothing Longevity: The Relationship Between the Number of Users, How Long and How Many Times Garments Are Used. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352993692 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- ECOS. Durable, Repairable and Mainstream: How Ecodesign Can Make Our Textiles Circular, 2021. Available online: https://ecostandard.org/publications/report-durable-repairable-and-mainstream-how-ecodesign-can-make-our-textiles-circular/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- ETC/WMGE. Textiles and the Environment in a Circular Economy, 2019. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-wmge/products/etc-wmge-reports/textiles-and-the-environment-in-a-circular-economy (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Sandin, G.; Roos, S.; Spak, B.; Zamani, B.; Peters, G. Environmental Assessment of Swedish Clothing Consumption-Six Garments, Sustainable Futures, 2019. Available online: https://research.chalmers.se/en/publication/514322 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Nguyen, Q. Van; Wiedemann, S.; Simmons, A.; Clarke, S.J. The Environmental Consequences of a Change in Australian Cotton Lint Production. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Worrell, E.; Patel, M.K. Environmental Impact Assessment of Man-Made Cellulose Fibres. Resour Conserv Recycl 2010, 55, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velden, N.M.; Patel, M.K.; Vogtländer, J.G. LCA Benchmarking Study on Textiles Made of Cotton, Polyester, Nylon, Acryl, or Elastane. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2014, 19, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, G.; Som, C.; Schmutz, M.; Hischier, R. Environmental Consequences of Closing the Textile Loop—Life Cycle Assessment of a Circular Polyester Jacket. Applied sciences 2021, 11, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Liakh, O.; Paço, A. do; Dennis, K.; Shollo, F.; Sidsaph, H. Reducing the Carbon Footprint of the Textile Sector: An Overview of Impacts and Solutions. Text Research J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETC/WMGE. Plastic in Textiles: Potentials for Circularity and Reduced Environmental and Climate Impacts, 2021. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-wmge/products/etc-wmge-reports/plastic-in-textiles-potentials-for-circularity-and-reduced-environmental-and-climate-impacts (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. What Affects Garment Lifespans? International Clothing Practices Based on a Wardrobe Survey in China, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the USA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Kettlewell, R.; Wiedemann, S. Laundry Care Regimes: Do the Practices of Keeping Clothes Clean Have Different Environmental Impacts Based on the Fibre Content? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.G.; Clarke, S.J.; Nguyen, Q. Van; Cheah, Z.X.; Simmons, A. Strategies to Reduce Environmental Impacts from Textiles: Extending Clothing Wear Life Compared to Fibre Displacement Assessed Using Consequential LCA. Resour Conserv Recycl 2023, 198, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.; Hill, H.; Kinmouth, J.; Townsend, K.; Hughes, M. Design for Longevity: Guidance on Increasing the Active Life of Clothing, 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313479112_Design_for_Longevity_Guidance_on_Increasing_the_Active_Life_of_Clothing (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- ReCiPe 2016 LCIA: The ReCiPe Model. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/life-cycle-assessment-lca/recipe (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- SimaPro. SimaPro Database Manual. Available online: https://support.simapro.com/s/article/SimaPro-Methods-manual (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- WRAP. How to Use the Clothing Longevity Protocol, 2014. Available online: https://www.wrap.ngo/resources/guide/extending-clothing-life-protocol (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- WRAP. Citizen Insights - Clothing Longevity and CBM Receptivity in the UK, 2023. Available online: https://www.wrap.ngo/resources/report/citizen-insights-clothing-longevity-and-circular-business-models-receptivity-uk (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Bianco, I.; Picerno, G.; Blengini, G.A. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Worsted and Woollen Processing in Wool Production: ReviWool® Noils and Other Wool Co-Products. J Clean Prod 2023, 415, 137877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, N.; Puig, R.; Raggi, A.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Tassielli, G.; Camillis, C.; Rius, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Italian and Spanish Bovine Leather Production Systems. Afinidad -Barcelona- 2011, 68(553), 167–180. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248707414_Life_Cycle_Assessment_of_Italian_and_Spanish_Bovine_Leather_Production_Systems (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Torres, C.B. Life Cycle Assessment of Raw White, Dyed and Pigmented Acrylic Fibres and Proposals for the Improvement of Environmental Performance. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10362/109862 (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Gottfridsson, M.; Zhang, Y. Environmental Impacts of Shoe Consumption Combining Product Flow Analysis with an LCA Model for Sweden. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12380/218968 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Gomez-Campos, A.; Vialle, C.; Rouilly, A.; Hamelin, L.; Rogeon, A.; Hardy, D.; Sablayrolles, C. Natural Fibre Polymer Composites - A Game Changer for the Aviation Sector? J Clean Prod 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, M.F.; Thalwitz, G.; Vollrath, F. Life Cycle Assessment of Indian Silk. J Clean Prod 2014, 81, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armouch, F.; Paulin, M.; Laroche, M. Is It Fashionable to Swap Clothes? The Moderating Role of Culture. J Consum Behav 2024, 23, 2693–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, T.S. Share, Don’t Shop: Exploring Value, Sociality and the “alternative” at Clothing Swaps. JOMEC Journal 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Algurén, P.; Bergman, E.; Blomqvist, E.; Friedl, H.; Hennessy, J.; Johansson, A.; Linder, M.; Mcallister, I. Second-Hand Is [Currently] Bad for Global Sustainability, 2024. Available online: https://www.misolutionframework.net/publications/second-hand-is-currently-bad-for-global-sustainability (accessed on 12 December 2024).

| Swapped*, units | Share of the category out of all swapped clothing units*, % | Swapped*, kg | Share of the category out of all swapped clothing units, mass %* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swapped overall | 532 | 100 | 197,523 | 100 | ||

| Labeled clothing | 464 | 87 | 165,901 | 84 | ||

| Single-fiber fabric composition | 262 | 56 % of which | Polyester – 37.5% Cotton – 29.9% Acrylic – 10.9% Wool – 5.5% Viscose – 4.9% Other** – 11.3 % |

117,483 | 71 | |

| Blended-fiber fabric composition (average composition of all blended clothing) | 202 | 44 % of which | Polyester – 31.6% Cotton – 29.8% Viscose – 15.1% Acrylic – 5.5% Wool – 4.0% Other** – 14.0 % |

48,418 | 29 | |

| Unlabeled | 68 | 13 | 29,616 | 15 | ||

| Clothing categories (28) | Jumper, jeans, trousers, waistcoat, T-shirt, tunic, sweater, blouse, skirt, dress, shorts, jacket, leggings, outdoor vest, raincoat, coat, jacket, underwear, footwear, belt, hat, swimsuit, swimwear, sleepwear, gloves, handbag, scarf, socks. | |||||

| User entered/ default | Data needs |

|---|---|

| User entered data | Composition of clothing fabric, %; Clothing category; Garment condition (unused, worn); Purchase method (purchase as new or worn, gifted/swapped). |

| Default data entered into the database | Average clothing weight depending on category, kg; Frequency of wear, number of times during ownership; Frequency of washing, number of times during ownership; 11 fabrics LCA (new and used) data per 1 kg in four impact categories. |

| Average environmental impact of SWAPPED fabrics during the second use*, for 1 kg | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact | ACRYLIC | COTTON | LEATHER | POLYESTER | WOOL | VISCOSE | |||||

| Global warming, kg CO2 eq | 22.8 | 22.8 | 4 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 22.8 | |||||

| Water consumption, m3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |||||

| Energy demand, MJ | 608 | 608 | 84.76 | 608 | 608 | 608 | |||||

| Land use, m2a crop eq | 107.5 | 107.5 | 0.08 | 107.5 | 107.5 | 107.5 | |||||

| *Average laundering (washing, drying, ironing) time per second user 9.5 times. Leather use includes just cleaning with appropriate cleaners. Use includes also transportation to and from the swap. | |||||||||||

| Average environmental impact of NEW fabrics, during raw material extraction, production, retail and distribution, first use**, and EoL stages, for 1 kg | |||||||||||

| Impact | ACRYLIC | COTTON | LEATHER | POLYESTER | WOOL | VISCOSE | |||||

| Global warming, kg CO2 eq | 64 | 85.2 | 469.4 | 73.2 | 136.3 | 65.5 | |||||

| Water consumption, m3 | 1.9 | 15 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2 | |||||

| Energy demand, MJ | 1549.4 | 1911 | 1358.4 | 1626.4 | 2161.9 | 1592 | |||||

| Land use, m2a crop eq | 224.1 | 1102.9 | 10460.6 | 224.7 | 552.1 | 225.3 | |||||

| **Average laundering (washing, drying, ironing) time per first user 19.4 times. Leather use includes just cleaning with appropriate cleaners. Use includes also bringing the garment home. | |||||||||||

| Average environmental impact reduction due to clothing swapping, by fabric type, for 1 kg | |||||||||||

| Impact | ACRYLIC | COTTON | LEATHER | POLYESTER | WOOL | VISCOSE | |||||

| Global warming, kg CO2 eq | -41.2 | -62.4 | -465.4 | -50.4 | -113.4 | -42.7 | |||||

| Water consumption, m3 | -1.1 | -14.2 | -2.1 | -1.1 | -1.4 | -1.2 | |||||

| Energy demand, MJ | -941.5 | -1303 | -1273.7 | -1018.4 | -1553.9 | -984 | |||||

| Land use, m2a crop eq | -116.6 | -995.3 | -10460.6 | -117.2 | -444.6 | -117.8 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).