1. Introduction

Aviation, like any other industry, is profiting from current advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). However, unlike some other industries, aviation relies on numerous safety-critical systems, which are subject to strict certification processes. As such, AI-based systems for aviation have to be certified according to the same standards as traditional systems [

1]. To ensure the certification of AI-based systems, a transparent and structured development process is necessary. The current state-of-the-art and industry standard in aviation is the well-established V-model process for verification and validation (V&V) [

2]. It is, however, not suitable for the development process of AI-based systems, which cannot be understood as traditional software [

3,

4]. Typically, the V-model focuses on executing tests in a predetermined order, which does not align with the iterative and dynamic nature of the development of AI-based systems. Given the long history and general success of the V-model, any new standard for these AI-based systems should comply with the V-model to ease adoption. To address this issue, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) introduced processes for the development of AI-based systems, such as the W-shaped process [

5,

6]. The proposed W-shaped process is executed parallel to the V-model [

2], adding dedicated AI constituent requirements and certain tasks for data management and model training. Furthermore, it ensures sufficient generalization and robustness capabilities for AI-based systems. The W-shaped process supports an iterative process during the implementation phase, allowing for feedback loops in training and testing. Due to the iterative training, V&V, and testing, the W-shaped process ensures that the AI-based system is continually assessed and improved, ultimately leading to a more robust and trustworthy AI system [

6]. Still, in its current setup, the W-shaped process is only applicable for supervised learning, although including first ideas from unsupervised and self-supervised; reinforcement learning is not yet addressed in the W-shaped process [

6]. Due to its ability to combine classical development methods with novel requirements of AI-based systems, the W-shaped process has already been used in domains other than aviation [

7]. However, the EASA learning assurance process and thus the whole structure of the W-shaped process and the proposed extended W-shaped process are not without critique [

8]. It has been noted by other works, that, although the general process is indisputable, some objectives proposed by EASA can only be verified empirically while others are outright impossible to verify.

Nevertheless, the W-shaped process is not the only process currently undergoing standardization activities for the development of AI-based systems in aviation [

9]. Another proposed framework is currently being developed under the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group, a joint effort between EUROCAE and SAE, for the Machine Learning Development Lifecycle (MLDL) [

10]. The MLDL process aims to ensure comprehensive management and interoperability of model-based data throughout the development process, supporting the certification/approval process of AI-based systems in aviation [

10].

Applying the Development Operations (DevOps) cycle, which merges development and operations into a holistic process aiming for continuous improvement, is nowadays the state of the art in software development. By adopting continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) practices, DevOps enhances collaboration through rapid feedback and is an agile approach. This characteristic fits well with the complexity in the development of AI-based systems, which requires iterations early in the development phase in contrast with linear processes [

11]. Therefore, a process combining both the advantages of the W-shaped process and the DevOps cycle promises to ease the development of AI-based systems in aviation by streamlining the AI Engineering process. The possibility to continuously deploy updated ML models even after the first deployment offers a more flexible development framework. However, the increase in flexibility comes at the cost of a non-fixed requirements list. While software-based components can be updated iteratively, hardware components in aviation cannot. Thus, fully integrating DevOps in both software and hardware into the standard aviation development process is still subject to current research. In this work, several approaches for the development of AI-based systems, such as the W-shaped process and the proposed framework by the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group are investigated, and further advancements incorporating the DevOps cycle are outlined.

To efficiently capture all requirements, a Concept of Operations (ConOps) is created. The ConOps documentation outlines all stakeholder requirements based on their specific needs and expectations, helping with the communication between stakeholders [

12,

13]. Moreover, a fixed high-level requirements list is essential to ensure compatibility between independently developed subsystems, where each subsystem could potentially be an AI-based subsystem [

14]. Each subsystem, however, must have its own detailed but mutable requirements list, which can be updated throughout the development process. The requirements list for a subsystem is currently being derived by combining the ConOps documentation with more specific requirements derived from the W-shaped process’s requirements process. As the development progresses along the W-shaped process, the focus shifts to data gathering, analysis, and dataset preparation. In case of a required re-evaluation of the requirements, the W-shaped process already allows for this procedure to happen in the aforementioned steps. Thus, allowing for the requirements list to be updated iteratively. The AI Engineering framework presented here advances this process structure and puts more emphasis on a potential re-evaluation of the whole architecture based on monitoring feedback to enhance the AI-based (sub)system’s capabilities in each iteration. This integration is achieved by further deepening the incorporation of certain DevOps concepts into the W-shaped process-based framework.

As part of the ConOps, a clear definition of the expected operational environment is not only helpful but required by EASA for all future AI applications in aviation. This idea has been developed in the automotive domain, where methodologies for the development of safety-critical AI-based systems are further advanced, and has since been standardized [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Different terms describing different aspects of the environment have been defined. Starting with the Operational Domain (OD), in the automotive domain it is defined as the set of all possible operating conditions. Next, driven by the design of the Automated Driving System (ADS), is the Operational Design Domain (ODD). It defines the operating conditions for which the ADS has been designed. In the aviation domain, however, EASA proposed slightly different definitions which will be used from here on [

6]. What SAE and ISO define as an ODD, EASA defines as an OD, the operating conditions for the full system. The term ODD has been repurposed and under EASA definition describes the operating conditions of only the AI/ML constituent, that part of the full system that contains the artificial intelligence. It can be a subset, but also a superset of the OD and it might depend on the parameter in question whether the OD or ODD covers a broader range of values. The ODD being a superset of the OD helps in improving the performance of the AI/ML constituent by allowing a broader range of values and thus more variety, especially in the border regions. A more complete introduction to ConOps, OD, and ODD will be given in

Section 5.1.

The paper is structured as follows. First, in

Section 2, the current state of the art is discussed, focusing on both the evolution from the V-model to EASA’s W-shaped process as well as DevOps and traditional software development processes. For both topics, prior research concerning the expansion towards the development of AI-based systems is discussed. Based on those findings, the current challenges in AI Engineering focusing on the aviation domain are discussed in

Section 3. Following, in

Section 4, the extension potential of the W-shaped process is discussed. Here, the main focus is the missing operations phase from the DevOps framework, which is crucial for the continuous improvement of AI-based systems. Next, in

Section 5, a new framework is proposed that combines the strengths of the W-shaped process with ideas from DevOps. Besides the aforementioned operations phase, the new framework also starts earlier in the development process, with the creation of a ConOps document, and thus also counties further than the W-shaped process. After proposing this updated framework, a comparison to the Machine Learning Development Lifecycle defined by the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group is made in

Section 6. In this section, the focus is on the differences between the two frameworks and possible conflicts that arise from these differences. Examples of how the framework applies to specific AI-based systems are given. Finally, in

Section 7, the results of the paper are discussed, and in

Section 8 conclusions are drawn.

2. State of the Art

Clearly defined engineering frameworks are the basis for a safe development process. As such, they are crucial in the development and later certification in aviation, from small subsystems and parts up to the full aircraft. Here, the V-model [

19] is the current standard in the development of aircraft. However, it is not suitable for the new challenges that arise in the development of AI-based systems. Therefore, the W-shaped process [

6] has been developed while still being based on the same ideas and principles as the V-model. On the contrary, in modern software engineering, DevOps is the current default for AI-based systems as it offers shorter iterations and increased feedback. To better understand the history and reasoning of those two frameworks, the following section formally introduces both frameworks and highlights their differences.

2.1. The W-Shaped Process for AI-Based Applications

In February of 2020, EASA issued their first version of the Artificial Intelligence Roadmap for AI-based applications in aviation [

20] followed by the publication of a concept paper for level 1 machine learning applications [

21]. Therein proposed is the novel concept of learning assurance for providing means of compliance. To achieve compliance, learning assurance is the assurance that all actions of the AI-based systems that could result in an error have been identified and corrected [

21]. To help with the learning assurance, EASA proposed the W-shaped learning assurance process, covering dedicated AI/ML constituent requirements throughout the process. This W-shaped process stands in the longstanding line of different versions of the initial V-model. One of the first processes in the realm of software development was the waterfall model [

22,

23] in which the development process is divided into separate phases. Each phase needs to be finalized before the next phase can be started. Years later the V-model was developed and, in its various types and forms, became the standard process for safety-critical applications in aviation [

24]. The principal idea was to separate development and testing activities and track the required steps on all system levels [

25]. Later, the V-model was introduced to the verification and validation of software [

19]. However, the structure of the process allowed extensive testing of the developed software only after it had been finalized. This issue led to the development of a W-shaped adjustment of the classical V-model, the first mention of a W-model, similar to the W-shaped process [

25]. This model is also known as the VV-model, Double-V-model, or Two-V-model [

26,

27]. Since in software development 30% to 40% of the activities are related to testing, launching testing activities early is crucial [

25]. Therefore, the idea was to bridge the gap between development and testing for software applications by introducing an early testing phase which is illustrated by the second V-model placed on top. Consequently, testing starts parallel to the development process instead of after the finalization. It has also been mentioned, that models simplify reality but their simplifications make them successful in their applications [

25]. Aspects such as resource allocation seem to be equal in the W-model, however, depending on the application reality might be different.

Based on this early W-model, further adjustments to other applications took place. Later, the W-model was adjusted to testing software product lines [

28]. The left side of the W covers the domain engineering while the right side covers application engineering. In their work, several test procedures for variability and regression tests are addressed. Other works adjusted the W-model towards component-based software development using two conjoined V’s. One V is defined for the component development process while the other V stands for the system development process [

29]. By having a dedicated V-model for the component life-cycle, component V&V can be executed and pre-verified components are stored in the repository.

The most recent adjustment of the W-shaped process is EASA’s adaptation towards AI-based systems for aviation applications [

21]. Two years later, in 2023, the newly proposed W-shaped process was first applied to a use case outside the aviation domain [

7]. This study outlined an approach for the implementation of a reliable resilience model based on machine learning. Liquefied natural gas bunkering served as a use case to show, that the system can learn from incomplete data and still give predictions on the latent states and enhance system resilience.

Out of a joint project with EASA, Daedalean published two reports applying the W-shaped process to visual landing guidance [

30] and visual traffic detection [

31]. Based on both use cases, Daedalean went through the steps of the W-shaped process identifying points of interest for future research activities, standard developments, and certification exercises. The first report [

30] focused on the theoretical aspects of learning assurance only considering non-recurrent convolutional neural networks. Some of the main findings included that traditional development assurance frameworks are not adapted to machine learning, a lack of standardized methods for evaluating the operational performance of the ML applications, and the issue of bias and variance in ML applications. As an outlook for future work, the risks associated with various types of training frameworks and inference platforms were identified. However, the types of changes applied to a model after certification were not discussed. The second report [

31] aimed at software/hardware platforms for implementing neural networks and other tools in the development and operational environments. Regarding the safety assessment, out-of-distribution detection, filtering and tracking to handle time dependencies, and uncertainty prediction were investigated. Aspects, such as changes after the type certificate, proportionality, and non-adaptive supervised learning, were not covered by the report and remain topics for future investigation.

Initiated by EASA, the MLEAP project [

32] aimed at investigating the challenges and objectives of the W-shaped process and alleviating the remaining limitations on the acceptance of ML applications in aviation. Three aeronautical AI-based use cases, namely speech-to-text in air traffic control, drone collision avoidance (ACAS Xu), and vision-based maintenance inspection were used. One goal of the project was to identify promising methods and tools and preliminary testing them on toy use cases, followed by validation of those results on more complex aviation use cases. The report states that the OD definition is challenging as estimating the completeness and representativeness requires knowledge of the exact extent and distribution of certain phenomena. It further states that the currently publicly available set of tools and methods for the development of AI-based systems lack operationalizability. One of the main conclusions of the joint report is that data is the centerpiece of the development process as it severely influences the model’s performance [

32].

2.2. DevOps and Traditional Software Development

DevOps, a term combining the “development” and “operations” of a product, was developed by the software development domain to enable continuous delivery and integration of products. In conventional

heavyweight development methods, for example, the waterfall model, the process often leads to longer development times and poor communication between teams, resulting in delays and inefficiencies [

33,

34]. To address this problem, the Manifesto for Agile Software Development has been written [

35], promoting transparency and improving communication within teams. Nevertheless, some problems continued even after the introduction of Agile methods [

36,

37]. Conflicts arose between the development and operations teams, particularly during the deployment of new features [

38]. Additionally, maintaining and updating software as needed was not always straightforward [

39]. To solve this, the development and operations teams needed to collaborate more closely to streamline processes. As an extension of Agile methodology, DevOps was introduced to enhance collaboration and communication [

40]. It emphasizes continuous integration and delivery, ensuring more frequent software updates and improvements. Previous works [

41] outline four key requirements for DevOps in the context of software development within the automotive domain:

deployability,

modifiability,

testability, and

monitorability. These elements support the processes of continuous delivery, integration, and deployment. The authors also suggest that to enhance the effectiveness of DevOps, three additional principles should be considered:

modularity,

encapsulation, and

compositionality [

41].

Given its general success, DevOps has also been introduced into the aviation domain. It has helped to enhance the airline booking system by streamlining interactions between development and operations teams [

42]. Moreover, in Industry 4.0, the collaborative practices used in DevOps have proven beneficial in addressing the gaps between traditional industrial production environments and the requirements of Industry 4.0. As such, Industrial DevOps led to the development of a modular platform designed to integrate and monitor production systems [

43]. Apart from industry applications, DevOps and Agile methods have also gained attention in the scientific community [

44]. DevOps has been shown to enhance collaboration among researchers throughout the development cycle [

45].

Despite, or maybe because, of its overall positive adaption into many domains, new ideas for the DevOps cycle are still being developed. Integrating machine learning workflows into the DevOps cycle is also being considered to manage complex software components that involve ML components. Some advantages of using DevOps include streamlined ML artifact versioning, as well as support for testing and deploying ML models through continuous integration. Moreover, combining DevOps and ML workflows can enhance collaboration between data scientists and software engineers [

46]. The research for using DevOps in ML applications has also led to the development of the Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) framework [

47]. This DevOps derivate focuses on methodologies and development approaches aimed at operationalizing machine learning products by leveraging DevOps and adapting it for the specific needs of machine learning applications [

48]. MLOps integrates machine learning, software engineering, and data engineering to bridge the gap between development and operations [

49]. Although DevOps practices already provide continuous integration and delivery and enhance team collaboration, other derivations of DevOps put the focus more on the safety of the system. Thus, SafeOps has been developed, designed to improve the safety of autonomous systems through a model of “continuous safety” inspired by DevOps principles [

50]. SafeOps emphasizes continuous monitoring, feedback loops, and integration across development and operational phases, ensuring that autonomous systems remain compliant with safety standards during operation. The three pillars of SafeOps are

diagnosis,

measurement, and

modification, which provide continuous safety assurance and faster deployment [

50]. Similar to these safety considerations, security aspects in the software development lifecycle are addressed by yet another derivate, DevSecOps [

51]. It focuses on integrating Development, Security, and Operations. To ensure security, the team incorporates security-focused tools into the CI/CD pipeline. For faster development cycles, DevSecOps relies on automated security tools.

2.3. Differences in Philosophy Between the W-Shaped Process and the DevOps Cycle

Both EASA’s W-shaped process and the DevOps cycle aim at achieving reliable software and system development, but they approach the development lifecycle with different philosophies and goals. Historically, the W-shaped process was defined for safety-critical applications such as avionics and aircraft systems in the aviation sector, focusing on safety, regulatory compliance, and rigorous testing. In contrast, the DevOps cycle is a widely adopted approach for general software engineering. It is centered around continuous integration, delivery, and deployment to accelerate development cycles while maintaining high-quality output. Furthermore, it encourages collaboration between development and operations teams. Considering the process structure, one apparent difference between both methodologies is the sequential and structured phases of the W-shaped process compared to the cyclical, iterative, and constantly looping phases of the DevOps cycle. The W-shaped process progresses linearly from system requirements and moves through design and development before finishing with a well-documented testing and V&V phase. On the contrary, documentation during the DevOps cycle is kept to a required minimum focusing on code and release comments.

In the context of testing, the W-shaped process heavily focuses on formal verification and validation typical for safety-critical aviation applications. This includes exhaustive documentation as well as testing at each stage, thus ensuring each step meets compliance standards before moving to the next. Here, DevOps emphasizes the automation of tasks through CI/CD, allowing for faster and more frequent updates and thus releases. Automated testing is integrated throughout the process to identify issues as early as possible.

Feedback loops are key to identifying issues early on in the development phase. The W-shaped process emerged from the V-model to promote early feedback through predefined feedback loops. It allows for iterations during both the model training and implementation. On the contrary, the DevOps cycle features continuous feedback loops throughout the development. Arguably, this continuous feedback is one of the most important features of the DevOps cycle and therefore one core difference in comparison to the W-shaped process.

Furthermore, both methodologies differ in terms of typical cycle length. The W-shaped process defines the whole development process until the final product release after passing the AI/ML constituents requirement verification. The DevOps cycle is theoretically an ongoing, never-ending loop of continuous improvement and frequent deliveries compared to the one delivery of the W-shaped process. Thus, one single iteration of the DevOps cycle is shorter compared to the W-shaped process.

3. Current Challenges in AI Engineering for Aviation

AI Engineering is gaining significant attention due to the increase of AI-based functions in safety-critical areas such as aviation, robotics, and the automotive sector. At its core, AI Engineering focuses on systematically developing every aspect of an AI component or function throughout its entire lifecycle. Thereby, the development and V&V processes constitute a considerable amount of the entire challenge. In addition to the accompanying processes, other aspects such as requirements engineering, data generation, monitoring, and many others play a crucial role.

Specifically, the integration of AI in aviation systems poses a significant challenge because of the inherent risk that comes with deploying passenger aircraft. Therefore, AI engineers are required to be meticulous when using CI/CD processes. Updates, in particular, need to be executed in a safe, reliable, and transparent manner. Additionally, there are many aspects to consider due to the human-AI interaction in assistance systems that are developed right now. Ensuring applicable interactions between humans and AI-based systems will require additional engineering work. Especially when AI-based systems are being used as assistants, the interface between the human and the AI requires exhaustive investigation, commonly explored through research in the field of Human-in-the-Loop (HTL) [

52]. Here, different approaches to how an AI-based system and humans can complement each other prevail, from the strict separation of roles, e.g., human oversight performed by a human supervisor, to collaborating as equal teammates in either a cooperative or collaborative approach [

5,

53]. Thus, depending on the specific use case, different approaches may be preferable. In addition to the different concepts of how the human-in-the-loop approach is implemented in the individual use cases, there are also questions about human factors that need to be taken into account. For instance, the issue of human trust is also relevant to the safety of the overall system as overtrust or mistrust of the AI-based system can lead to potential errors that could compromise the safe operation of said system [

54].

As already mentioned, sufficient data to train and evaluate the model is essential in providing safe AI-based systems. In that context, sufficient not only compels to cover all relevant scenarios but also to provide them with the necessary quality. This challenging task can only be solved by combining different approaches for data generation to cover all requirements, for example by training only on virtual data and later fine-tuning using real data [

55]. To clearly define the system-under-test within the operational environment and its current development stage, concepts from the automotive industry [

56] were already transferred to the aviation sector [

57]. One potential starting point for the generation of synthetic data are simulations as they are often cheap to perform in comparison to real experiments and offer high availability. Simulation-Enabled Engineering is therefore the basis for creating a data set for the learning process of

Safety-by-Design AI-based systems. Although simulations have great potential, the obtainable data quality is limited. Thus, careful evaluation is required to identify the correct balance between the quantity of simulation-based data and other more realistic and therefore higher quality but lower quantity data, like hybrid or real data. To improve the quality of simulation-based data, generative AI might also be able to enhance the realism of simulations or increase their variation [

58,

59]. Altogether, a combination of approaches will provide the optimal balance between quantity and quality of data, necessary to develop Safety-by-Design AI-based applications.

4. Extension Potential of the W-Shaped Process

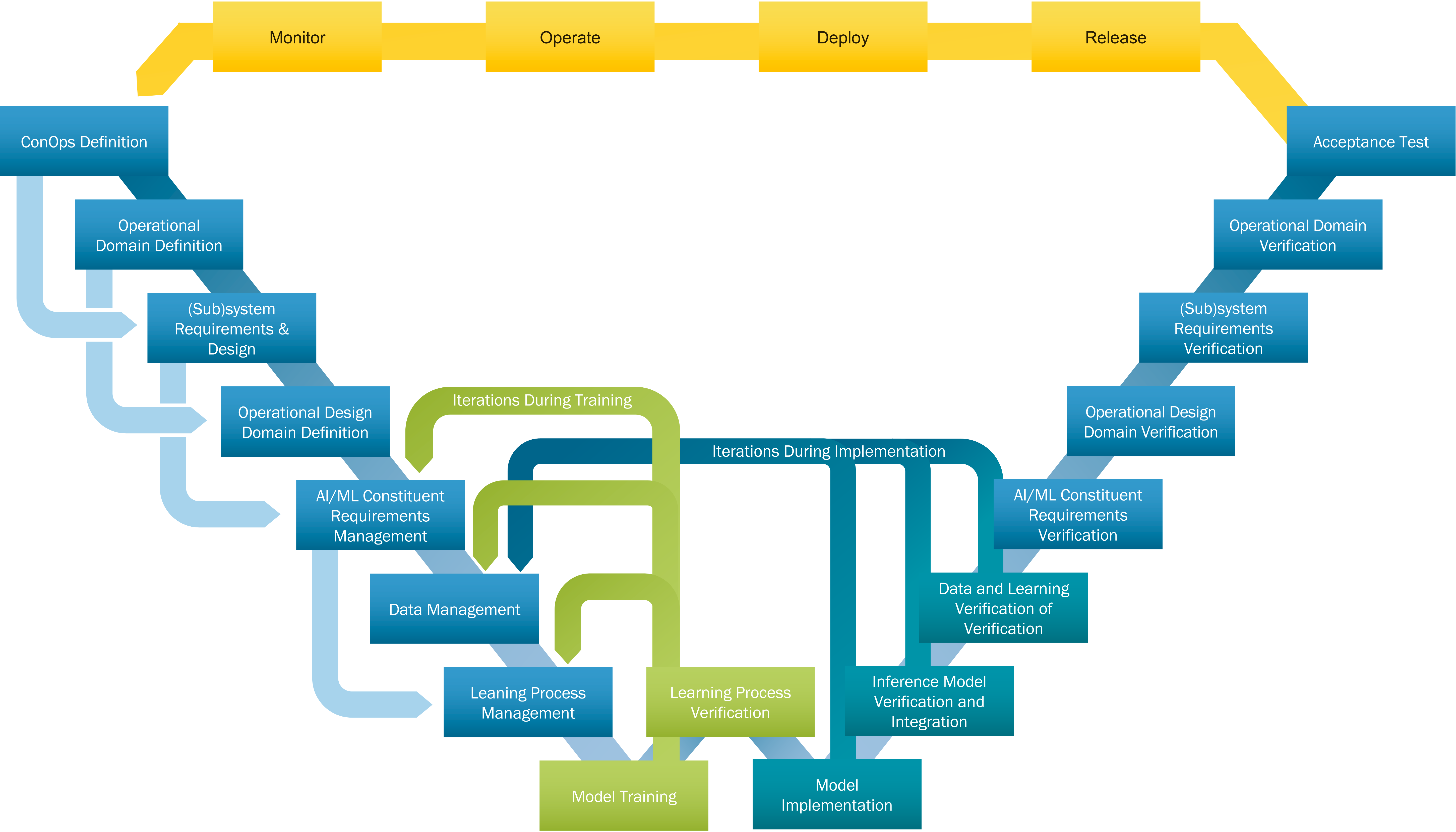

The W-shaped process, designed to run in parallel to the V-model, is required for the development assurance of AI/ML constituents [

6], see

Figure 1. As such, it brings some important changes to the V-model to adapt it to the specific needs of the development of AI-based systems. The W-shaped process emphasizes the importance of learning assurance as well as having iterative feedback loops early on in the development process. Both are crucial for the safe and secure development of AI-based systems allowing for a certification later on.

In Daedalean’s reports on design assurance [

30,

31] the W-shaped process was investigated. Based on the use case of visual landing and traffic detection, the general feasibility of the W-shaped process for level 1 ML applications was largely confirmed. The report found that future improvements are required, for example strengthening the link between learning assurance and data, required for improved AI explainability. However, the report was focused on the training phase and did not consider the implementation and inference phase verification. Therefore, this gap remains to be investigated. Especially with increasing algorithm complexity and higher levels of autonomy, the W-shaped process is potentially not as suitable for the development of AI-based systems as the also well-established DevOps cycle, which can be, to some extent, thought of as iterating over the W-shaped process multiple times [

57]. However, simply enforcing a purely DevOps-based approach in aviation is also not feasible, given the strict certification requirements. While it is understandable that the W-shaped process is based upon the well-established V-model, other, not less safety-critical domains, such as automotive, are already transitioning to the DevOps cycle. It has been shown that it better fits the iterative development process with which both traditional software and AI-based systems are developed [

41,

60]. As such, the W-shaped process is a good first step towards a more agile development process for AI-based systems in aviation. It lacks, however, some necessary elements from the DevOps approach to fully utilize the advantages of an iterative development process. At least some of those remaining extension potentials will be addressed in this section. The next section,

Section 5, will propose a new framework that further combines the strengths of the W-shaped process with the DevOps cycle.

Figure 1.

W-shaped process, based on [

6]. The arrows within the model from right to left already allow for an iterative approach during the development of an AI-based system.

Figure 1.

W-shaped process, based on [

6]. The arrows within the model from right to left already allow for an iterative approach during the development of an AI-based system.

A first and important constraint of the W-shaped process is that it is currently only applicable for supervised learning and not for self-supervised/unsupervised and reinforcement learning [

6]. As the authors of the W-shaped process are already well aware of this limitation, they plan to extend the guidance document to include these learning techniques in the future [

6]. Thus, it will not be part of the current discussion in this article.

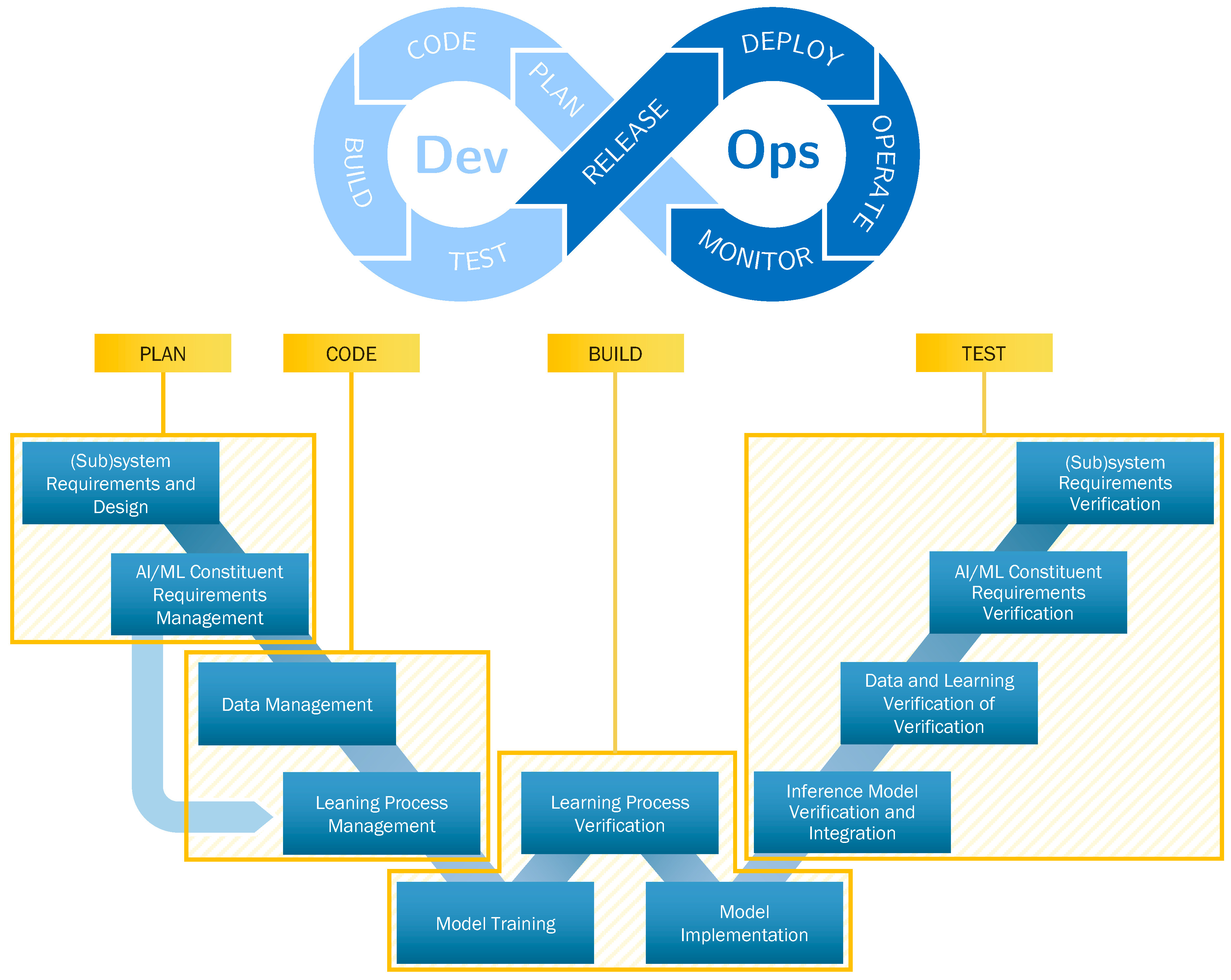

Compared to both the V- and W-shaped process, DevOps is characterized by a strong connection between development and operations. This effective collaboration enhances the agility of the software development process. Moreover, DevOps is separated into two phases; the development phase consists of

planning,

coding,

building, and

testing, whereas the operations phase consists of

releasing,

deploying,

operating, and

monitoring, as illustrated in

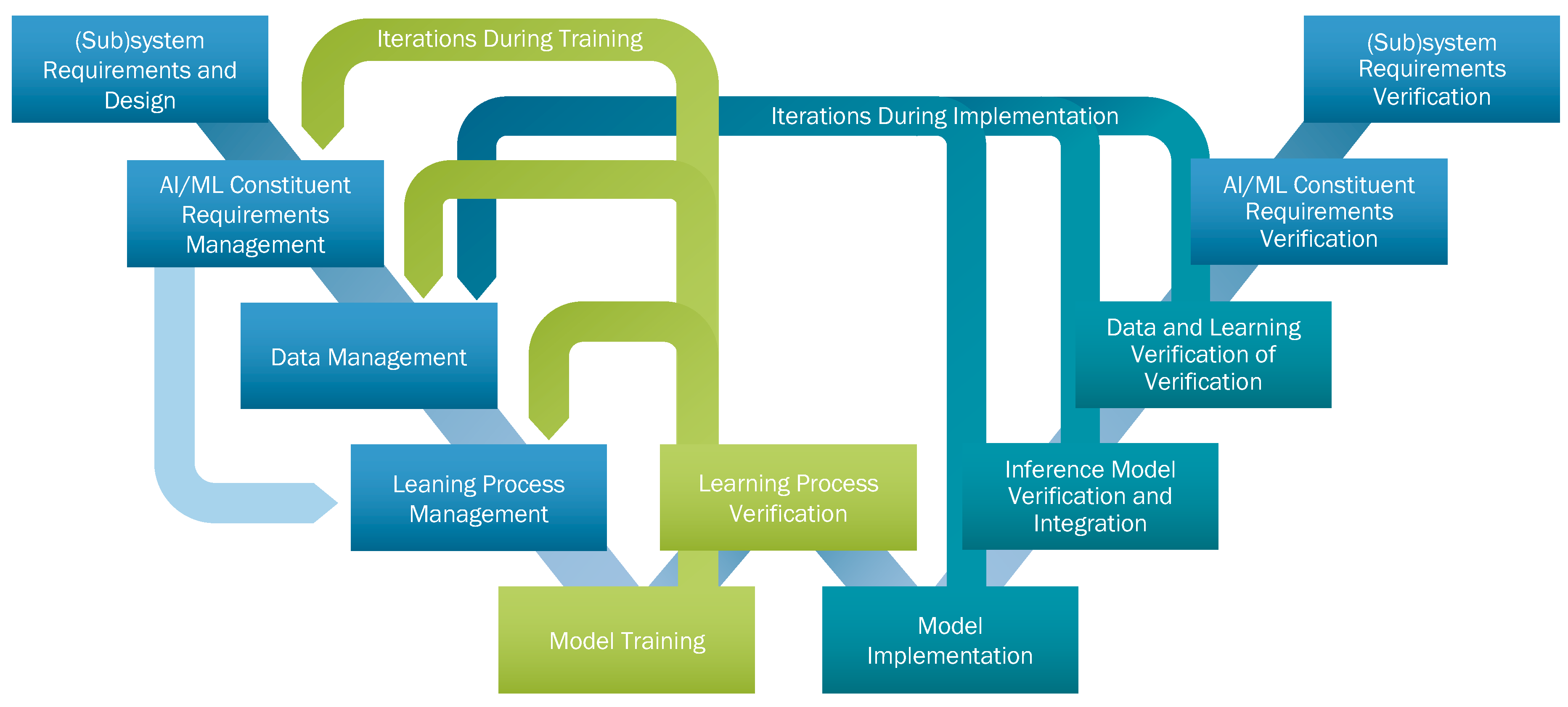

Figure 2.

As both the W-shaped process and DevOps have a similar goal in mind, streamlining a development process, a comparison is helpful to understand their differences and similarities, see

Figure 2 for a graphical representation of the following paragraph. During the planning step of the DevOps cycle, stakeholders and developers identify new features and fixes for the system but also quality criteria for each step [

11,

61]. Similarly, in the W-shaped process, the planning step involves establishing system and subsystem requirements and design, leading to the extraction of AI/ML-specific requirements [

6]. These requirements are essential for understanding the necessary data and models for specific applications, dividing them into AI/ML data and model requirements. In the DevOps cycle, after planning, developers proceed to the coding step, writing code for each feature or fix of the software. In contrast, the W-shaped process involves collecting, preparing, and organizing data based on the requirements for training, testing, and V&V. This stage also requires some coding activities, particularly for data generation, preprocessing, labeling, and splitting the dataset. Apart from defining the ML model’s architecture, including but not limited to the learning algorithms, activation functions, and hyperparameters, the learning process management includes generating the training pipeline for the model training. It also involves the verification of the learning process. During the building step of DevOps, developers use special automated tools to ensure the code builds correctly for the desired target platform, thus, preparing it for testing. In the W-shaped process, the model is trained based on the preceding steps, especially the data management and the learning process management, after which the learning process is verified. Afterward, the learning process is verified, allowing a loop back to earlier steps in case of failure. Next, in the model implementation step, the trained ML model can be implemented on the target platform for further V&V, analogous to the build step in DevOps. In the testing step of DevOps, all software components undergo continuous testing using automated tools. Here, the W-shaped process is more expressive as it clearly defines multiple levels of testing, one for every abstraction layer in the scope of the full product, ensuring that all AI assurance objectives are met at every layer.

Figure 2.

Matching the steps from DevOps to the W-shaped process. Here, the mapping from DevOps to the W-shaped process is straightforward to see. Moreover, the missing Ops phase is also apparent.

Figure 2.

Matching the steps from DevOps to the W-shaped process. Here, the mapping from DevOps to the W-shaped process is straightforward to see. Moreover, the missing Ops phase is also apparent.

The operations process in DevOps extends beyond the current scope W-shaped process process. In DevOps, the operations step takes over after the development step to initiate the release of the software. The deployment process is designed to be continuous, utilizing deployment tools to facilitate easy software deployment for all stakeholders. This approach increases productivity and accelerates the delivery of new software builds and versions. The operations phase involves managing software in production, including installation, configuration, and resource management. Finally, during the monitoring phase, the operations continuously monitor the software to ensure proper functionality [

6,

11,

61].

While the W-shaped process offers several advantages during the system development process, for example, the more expressive description of required tests, it lacks certain elements crucial for the continuous development of an AI-based system. Specifically, the W-shaped process ends after the testing phase of the AI-based system. It does not extend into the operational phase, as depicted in the DevOps cycle [

6,

11], see

Figure 2. In real-world applications, especially for safety-critical systems, it is essential to have mechanisms for post-deployment monitoring and continuous evaluation of the deployed AI-based system to ensure both the safety and security of a system even after the certification and release. Moreover, ongoing supervision in the form of monitoring also ensures the system’s reliability and performance throughout its operational lifecycle, detecting failures of the AI-based system as soon as they occur [

62].

5. Improving upon the W-Shaped Process

As seen in the previous chapter, the W-shaped process lacks some features required for a continuous development process often used for AI-based systems in other domains. Most noteworthy is the missing operations phase, which is crucial for the continuous improvement of AI-based systems. As such, a new framework is proposed that combines the strengths of the W-shaped process with those of the DevOps method. Furthermore, the proposed framework also starts earlier than the W-shaped process in the development process, with the creation of a ConOps document [

5,

6,

12]. The ConOps document is crucial to capture the requirements, based on the qualitative and quantitative system characteristics, of all stakeholders and define a common ground from which further work can be derived [

12,

63,

64]. From this ConOps document, the OD of the AI-based system can be derived [

12]. This OD captures the intended working environment of the AI-based system, allowing for an ordered description effortlessly readable for humans but also machine parsable. Later, the ODD can be derived from the previous steps, guiding the development of the AI/ML constituent. Similar to the OD, the ODD is also a well-structured document that helps to create a better understanding of the desired environment the (sub)system is expected to handle.

The proposed changes are discussed in the following section, starting with the ConOps, OD, and ODD in

Section 5.1 and afterward the addition of the operations phase in

Section 5.2. Lastly, the combined framework is introduced in

Section 5.3 and visualized in

Figure 3.

5.1. Concept of Operations, Operational Domain, and Operational Design Domain

A Concept of Operations is a concise user-oriented document agreed upon by all stakeholders outlining the high-level system characteristics for a proposed system. It describes the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of the system for all stakeholders [

12,

63,

64]. As such, it is the primary interface between the customer and the developers. However, although ConOps is defined at the beginning of a project and meant as a fixed baseline for all stakeholders, it is not immutable but subject to change requests. Utilizing the ConOps, all stakeholders can establish a common understanding of the system from which the Operational Domain can be derived [

12]. Here, it is important to clarify the distinct definitions of the terms Operational Domain and Operational Design Domain. As already stated in the introduction, see

Section 1, the definition of EASA differs from the commonly accepted definitions proposed by the SAE and ISO [

6,

15,

16]. The SAE and ISO define the Operational Domain as “set of operating conditions, including, but not limited to, environmental, geographical, and time-of-day restrictions, and/or the requisite presence or absence of certain traffic or roadway characteristics” and the Operational Design Domain as “the operating conditions under which an ADS is designed to operate safely” [

16]. In comparison, EASA defines the OD as the “operating conditions under which a given AI-based system is specifically designed to function as intended, in line with the defined ConOps” and the ODD as the “[o]perating conditions under which a given AI/ML constituent is specifically designed to function as intended, including but not limited to environmental, geographical, and/or time-of-day restrictions” [

6]. From these definitions alone, it is apparent that EASA defines the OD as equivalent to SAE’s definition of the ODD. Both are the operating conditions to be considered for the safe design of an autonomous system, regardless of whether it is an ADS or AI-based system. What EASA defines as the ODD, however, is similar to SAE’s definition of the OD only that the scope is not the full AI-based system but the part of the environment relevant to the AI/ML constituent. This can be both, a subset and a superset of the OD.

Based on the definitions from EASA, the OD, as derived from the ConOps, describes the exact operating conditions under which a system is designed to function [

6,

65,

66]. It is already extensively used for autonomous vehicles in the automotive domain [

66,

67] and the transfer to aviation is the subject of current research [

13]. In the automotive domain, the correspondence to the OD has been used for multiple years already, therefore, its content and structure are well-defined. For the aviation domain, however, although required by EASA for future AI-based systems [

5,

6], the structure of the OD is yet to be clarified [

13]. Nevertheless, defining the OD first and only afterward the AI/ML constituent requirements together with the ODD is crucial for the development of AI-based systems in aviation. As the ODD depends on the OD which in turn depends on the ConOps, any change request of the ConOps most likely also influences both the OD and ODD, even if only to verify that the previous OD and ODD are still valid.

Based on the previous discussion, the ConOps and OD are crucial for the development of AI-based systems and the ODD for their corresponding AI/ML constituent. As such, the definition of the ConOps and OD are part of the proposed framework, preceding the

Requirements Allocated to AI/ML Constituent step in the W-shaped process [

6]. However, as the (sub)system requirements will contain non-AI-related requirements, they will need to be defined first, before the ODD can be derived and defined. Accordingly, three new test steps will also be added, for the ODD, OD, and finally the ConOps. Those steps are required to verify and validate the ODD, OD, and finally the ConOps. All those newly proposed steps for the ConOps, OD, and ODD are visualized in

Figure 3, and the individual parts will be discussed in their corresponding subsections.

It is worth noting, however, that both the ConOps and the OD are mentioned as the input for the

Requirements Allocated to AI/ML Constituent step in the W-shaped process [

6]. Nevertheless, as they are mutable, the proposed framework explicitly includes these two as they are part of the DevOps cycle.

5.2. Operations Phase

In the DevOps framework, releasing is often as easy as moving changes from the development environment to the production environment. This is not possible in aviation as the production environment oftentimes is the aircraft itself. In aviation, releasing an AI-based system almost always requires a certification process. In general, for aviation, systems are categorized into different Development Assurance Levels (DALs) based on their safety impact on the aircraft [

68,

69]. Here, the higher the DAL of a system, the more stringent the certification process. The highest DAL, DAL A, is reserved for systems with a catastrophic failure condition, while DAL E is reserved for systems with no safety effect on the aircraft [

69,

70]. The different DALs are listed in

Table 1, which also lists some more information for each DAL, including but not limited to the accepted failure rate and the effect on the aircraft and the passengers. In

Table 1, however, the effect on the crew is not explicitly listed, although relevant. Only for DAL E systems certification is not required as those systems have no impact on the safety of the aircraft [

69,

70].

Table 1.

Relationship between failure probability and severity of failure condition, based on [

69,

70].

Table 1.

Relationship between failure probability and severity of failure condition, based on [

69,

70].

| DAL |

Failure Condition |

Failure Rate |

Effect on Aircraft |

Effect on Passengers |

| A |

Catastrophic |

<10−9 h−1

|

Normally hull loss |

Multiple fatalities |

| B |

Hazardous |

<10−7 h−1

|

Large reduction in capabilities |

Some fatalities |

| C |

Major |

<10−5 h−1

|

Significant reduction in capabilities |

Possibly injuries |

| D |

Minor |

<10−3 h−1

|

Slight reduction in capabilities |

Physical discomfort |

| E |

No Safety Effect |

N/A |

No effect |

Inconvenience |

However, DAL was never designed for AI-based systems and is thus not always applicable or sufficient for AI-based systems. Out of the necessity to have a similar rating for AI-based systems, EASA distinguishes between three levels for AI [

5,

9], see

Table 2. The three levels are based on the intended purpose of an AI-based system whether it is used for assistance only (level 1), for supporting a human in a human-AI teaming situation (level 2), or for advanced automation up to non-overridable decisions (level 3) [

5]. Future AI-based systems will most likely be categorized in both ratings as an AI-based system always requires traditional software components for interfacing with other components. Thus, systems with a high DAL rating but low AI level or vice-versa can be thought of. For example, an AI-based movie recommendation system for the In-Flight Entertainment (IFE) system will be a DAL E system as it does not affect the safety and a level 1 application since it is only assisting the passengers [

69,

70]. If the same system now includes a chatbot that interactively chats with the passengers and they together find a fitting next movie or TV show, this system is now a level 2 application. Still, such a system would most likely have no certification requirements. Other AI-based systems in aviation already being researched are vision-based landing systems [

71,

72]. While of clearly higher DAL ratings due to the inherent safety implications, as long as such a system only assists the pilots and does not make a decision, it will most likely be a level 1 application. However, due to the common problem of adversarial attacks, even this supposedly level 1 application will have stronger safety and security regulations than the aforementioned IFE recommendation system [

73,

74]. Finally, as a third example, the next generation of collision avoidance, ACAS X, is currently under development and part of current research [

75,

76,

77]. For this system, although no official AI level rating is available, first certification activities are already part of ongoing research [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

Table 2.

Classification of AI applications, based on [

5].

Table 2.

Classification of AI applications, based on [

5].

| Level |

Scope |

Sublevel |

Description |

| 1 |

Assistance to Human |

A |

Human Augmentation |

| |

|

B |

Human Cognitive Assistance in Decision and Action Selection |

| 2 |

Human-AI Teaming |

A |

Human and AI-based System Cooperation |

| |

|

B |

Human and AI-based System Collaboration |

| 3 |

Advanced Automation |

A |

The AI-based system makes decisions and performs actions, safeguarded by the human. |

| |

|

B |

The AI-based system makes non-supervised decisions and performs non-supervised actions. |

While there are no official guidelines on how to design and certify an AI-based system, special care has to be taken for current developments. For now, only the DAL rating can be used for the certification process of new AI-based systems. Nevertheless, the three levels for AI applications will be important for future regulations. As such, for AI-based systems that can be classified as DAL A to DAL D, more care has to be taken in the development process to reduce the risk of failing the certification process. Accordingly, the higher the classification level of an AI-based system is, the more future requirements such a system will face for certification. Thus, as a compromise, the operations phase can be executed multiple times before the final deployment, prior to starting with the certification of the AI-based system. For example, the operations phase could be executed in a flight simulator, where the AI-based system is tested in a controlled environment. After multiple rounds of testing, the AI-based system can be deployed in the actual aircraft, where the operations phase is executed again, now in the actual production environment. This way, the development of AI-based systems can profit from the more dynamic and iterative way of developing systems while still achieving the same standards as classical components ensuring the safety and security of the whole airplane. Exact numbers on the required amount of iterations cannot be given as this is highly dependent on the system and consequently hard to estimate beforehand.

Next, the deployment step of the operations phase has to be executed. Again, given the vastly different AI-based systems for aviation one can imagine, it is not possible to define a general process for the deployment step. Some systems might be able to be deployed in a secure over-the-air-like process, where a fleet of aircraft automatically downloads the new software, similar to other domains [

84]. This could be possible for systems with a DAL E classification as the aforementioned AI-based IFE recommendation system [

69,

70]. Other AI-based systems, however, might also need a hardware update which would require grounding the aircraft and most likely many man-hours. These updates could happen during the maintenance checks any aircraft has to undergo.

After deploying the AI-based system, the operating phase starts. For a successful operation, it is crucial, that the previous steps have been conducted diligently. Furthermore, a general recommendation is that neural networks should be static, often referred to as

frozen, during operations, as learning dynamically adds significant complexity not only to the system design but also to certification [

31,

62]. Moreover, as AI-based systems often exhibit a black-box-like behavior, explainability is crucial for systems to be accepted by human operators [

85]. For example, for the aforementioned next-generation collision avoidance system it might not be enough to issue the correct advisory to the pilots, the AI-based system should also briefly explain how it came to the advisory. Fortunately, this is a field of active and ongoing research in which guidelines for explainable AI have already been developed [

86].

Once an AI-based system is certified and deployed, monitoring it and its environment is crucial for future improvement. Although monitoring a system and receiving feedback from it in operation is often not part of aviation operations, it is decisive for the Safety-by-Design development and operations of AI-based systems. Thus, it shall be adopted for future AI-based systems in aviation. Monitoring also does not necessarily mean an invasion of privacy of either the passengers or the operating company. Here, developers and operators have to work together to ensure the safety and security of the system while also respecting the privacy of all stakeholders. However, only continuous monitoring can ensure future improvements as without monitoring, no data from operations is available for the developer to improve the system. One of the more important aspects to monitor for all AI-based systems are the OD and ODD. Both the OD and the ODD are essential for ensuring the safe and reliable operation of an AI-based system [

13]. Runtime monitoring confirms that the system stays within its predefined environmental boundaries. For automated systems, adhering to safety standards and regulations is essential, and one of the fundamental principles is closely monitoring the OD to guarantee overall system safety. Thus, continuous monitoring during the operational phase of DevOps plays a vital role in maintaining safety by ensuring that the AI-based system operates only within its safe operational parameters and can thus be trusted to provide accurate guidance. Approaches like predictive OD monitoring, which can utilize tools such as temporal scene analysis, can issue early warnings if the system is approaching the boundaries of its corresponding OD [

87,

88].

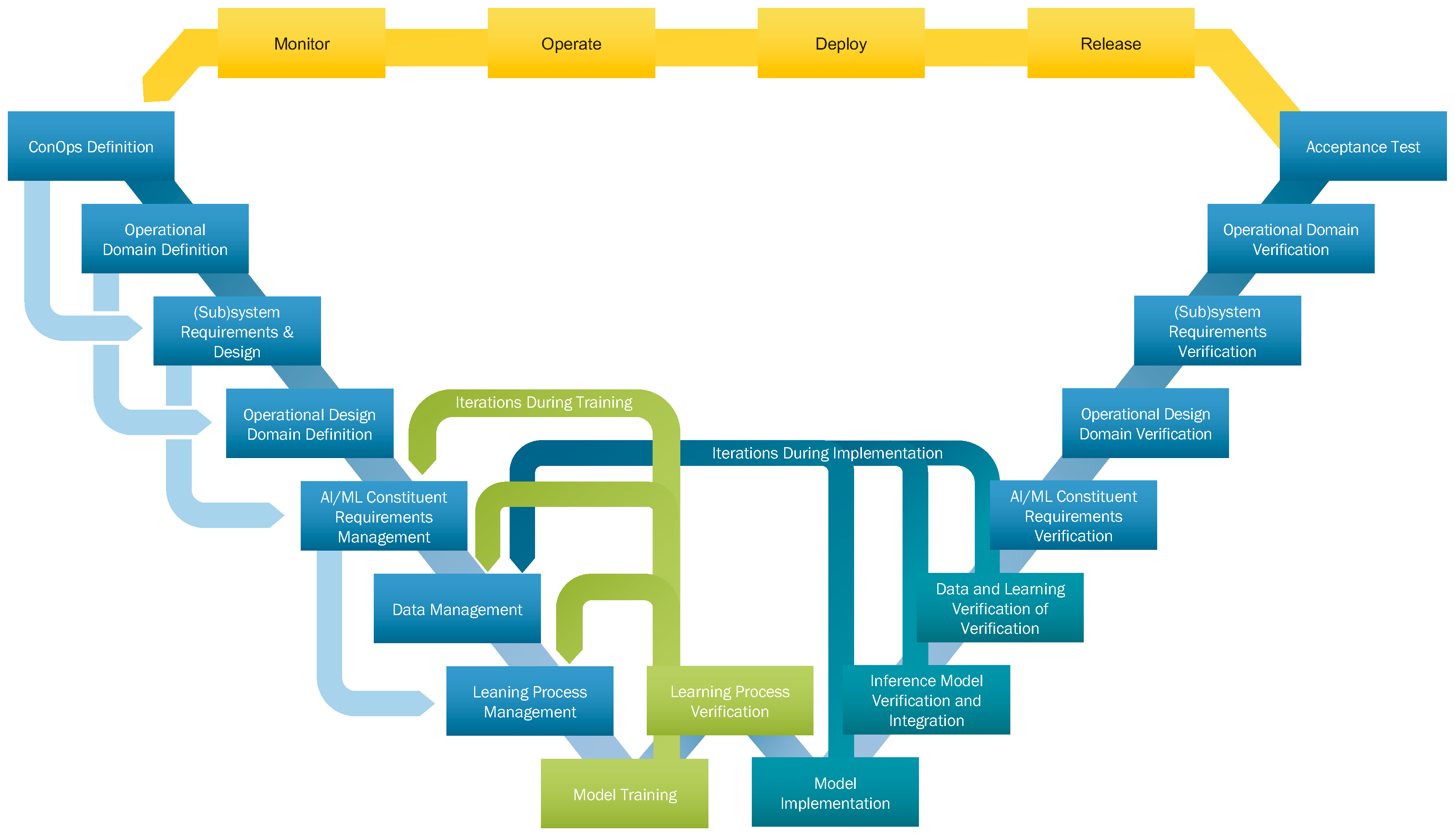

5.3. Proposition of the Novel Framework

Finally, bringing everything together, the proposed new framework is visualized in

Figure 3. The new framework is based on the W-shaped process by EASA [

6] but includes the ConOps and the OD early on in the development process, followed by the W-shaped process augmented by a dedicated step for the ODD definition. Corresponding test steps are also added to ensure correct V&V. After the test phase of the W-shaped process, elements from the operations phase of the DevOps method are introduced, namely the release, deploy, operate, and monitor steps. As explained earlier in

Section 5.2, the operations phase is crucial for the continuous improvement of AI-based systems, especially in aviation. Only a continuously developed system can overcome current problems with AI-based systems, such as their black-box nature and the lack of transparency. However, with an operations phase, and its corresponding steps, an AI-based system can be continuously improved, leading to a more transparent and trustworthy system. In addition, through iterative testing and feedback, the proposed frameworks’ structure supports investigating the explainability of AI algorithms, crucial for any safety-related AI-based application. By incorporating continuous testing and validation into the development workflow through several feedback loops, input from end-users or domain experts can be used to identify areas of insufficiencies or unexpected decisions. Also, this feedback structure supports the development of resilient systems in terms of error detection, error correction, monitoring, and logging. As with all AI-based systems, resilience, “the ability to recover quickly after an upset” [

89], is one of the main goals of the Safety-by-Design development process. The new framework, combining the W-shaped process with ideas from DevOps, is a promising approach for the development of AI-based systems in aviation. Its representation is visualized in

Figure 3. Here, the development process starts in the top-left corner with a classical V-model in parallel for non-AI-based systems. Important to note, and already part of the proposed W-shaped process by EASA [

6], is the iterative approach in the development process allowing for faster feedback and an easier improvement of the system. These iterative steps allow for a more flexible development process and thus more ways to react fast to later findings in the development of an AI-based system.

Figure 3.

The proposed new framework, based upon the W-shaped process by [

6]. It extends the W-shaped process by the

ConOps Definition,

Operational Domain Definition and

Operational Design Domain Definition steps and their corresponding tests,

Acceptance Test,

Operational Domain Verification and

Operational Design Domain Verification. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of the

Operations Phase from the DevOps cycle for a holistic design process.

Figure 3.

The proposed new framework, based upon the W-shaped process by [

6]. It extends the W-shaped process by the

ConOps Definition,

Operational Domain Definition and

Operational Design Domain Definition steps and their corresponding tests,

Acceptance Test,

Operational Domain Verification and

Operational Design Domain Verification. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of the

Operations Phase from the DevOps cycle for a holistic design process.

Developing a new AI-based system using the proposed framework would thus first require the definition of the ConOps. For an exemplary use case of the next-generation in collision avoidance for aircraft, ACAS X, the ConOps might contain high-level requirements such as the desired behavior, i.e., avoid near mid-air collisions, but also more specific performance metrics, for example updating the advisory once per second [

82,

83,

90,

91,

92,

93]. Based on the ConOps and the OD, and according to the W-shaped process, the (sub)system requirements can be derived. Both are important to better guide the development of an actual AI-based system in a safety-critical environment. The OD will contain information about the scenery, e.g., airspace information, but also more general environmental information like weather conditions [

83,

87]. Of utmost importance, at least in the aforementioned use case, however, are dynamic elements, i.e., the intruders invading the airspace. As the OD also contains parameter ranges for every element, later on, automated tests can be directly derived from the ODD [

57,

94]. Based on the ConOps, the OD, and the (sub)system requirements of the step before, an ODD can be derived, finally leading to the actual requirements for the AI/ML constituent. From here follows the W-shaped process as defined by EASA [

6].

As every step on the left-hand side of a V-model-inspired process requires corresponding tests on the right-hand side, so do the proposed steps for the ODD, OD and ConOps,

ConOps Definition and

Acceptance Test,

Operational Domain Definition and

Operational Domain Verification, and

Operational Design Domain Definition and

Operational Design Domain Verification. The

Operational Design Domain Verification step, verifying the ODD, requires that the system is shown to cover all aspects and areas of the hyper-dimensional parameter space of the ODD. As all elements in the ODD have a corresponding parameter range, the creation of automated tests is straightforward [

94]. However, determining the actual coverage of the ODD, especially for continuous parameter ranges, like altitude, is a complex problem. Still, current research is looking into exactly this topic [

95,

96]. Once the system is shown to cover the target ODD fully, testing can continue on the (sub)system level. Afterward, the tests for the ODD have to be repeated, now with the system-level OD in the

Operational Domain Verification and Validation step. The final test, in line with most V-model representations, is the acceptance test. On the one hand, it marks the final step in the certification of a system, on the other hand, it is the first interface to the customer since all stakeholders defined the ConOps.

After the W-shaped process is successfully passed, a system can go into certification and then be deployed. However, in many cases, a single pass through the W-shaped process might not be enough to develop a system that meets all certification requirements given its designated DAL. The collision avoidance system, for example, with its DAL B rating has way more certification requirements than a DAL E system, for example, an AI-based movie recommendation system for the IFE system. As the IFE is generally categorized as DAL E, compared to

Table 1, an AI-based system purely for the IFE will also be a DAL E system. As such, it has no certification requirements. Such a system could, in theory, be deployed regularly via an over-the-air update, similar to how most software updates for smartphones and personal computers are rolled out. The aforementioned ACAS X, with its higher DAL rating, cannot be rolled out and improved in multiple iterations in the actual aircraft in operations. As errors in the collision avoidance system can easily lead to tragic catastrophes, every new version of such an AI-based system has to go through extensive certification efforts to ensure the safety of all lives on board an aircraft [

82,

97,

98]. Thus, it might be desired, to split the operations phase into two different cycles. First, a faster cycle can be implemented only on the developer’s side to more quickly develop improvements. And only once a certain maturity has been reached, the system can go into certification and be deployed to the customers, in this case to actual aircraft. Still, even such a system might require later updates to the underlying AI model. For that reason, continuous improvement is still important, even for DAL B or higher systems. Therefore, in the operations phase of the proposed framework, steps similar to DevOps have to be undertaken. First, the developed AI-based system has to be released. In the case of aviation, and for systems of DAL D or higher, this requires a certification process as described earlier. Once this release process is finished, the developed system can be deployed to the target platform. Depending on the target platform, this can be more or less complicated. For some updates, especially those that might also require a new generation of hardware, grounding of the aircraft will be necessary. Those deployment steps can take weeks to years as it might be more efficient to deploy the changes when maintenance checks are planned anyway. Other deployment steps, however, might be, as discussed earlier, a simple over-the-air update, one that aircraft can automatically search for on a specific schedule, for example once a week. Once the system is deployed, operations can begin. This step is again strongly dependent on the developed AI-based system, but in general, this step should be part of the normal operations. The last important step of the framework, also derived from DevOps and somewhat parallel to the operating step, is the monitor step. As many AI-based systems lack realistic data or the abundance thereof, constant monitoring of the real operating conditions is required to continuously improve an AI-based system. Only with feedback from the real system and real data, a realistic dataset for training can be built. As such, this step is one of the most crucial steps in the proposed framework and might take the most effort to implement. The monitoring step requires the data from the actual system in operations to flow back to the developers, something not yet seen often in aviation. However, only with an evergrowing dataset that is moreover also built on real data, a continuous improvement and thus a safe AI-based system for aviation can be developed. It is the basis for a new iteration of the proposed framework leading towards safe and secure AI-based systems in aviation.

6. Compatibility to the Machine Learning Development Lifecycle

Besides EASA, other groups also work on similar standards for the development of AI-based systems in aviation. One of these important standards is being developed by the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group, a joint effort between EUROCAE and SAE. Their standard, currently only published as a draft of chapter 6 of AS6983/ED-XXX, focuses on the development of AI-based systems in aviation, specifically the Machine Learning Development Lifecycle, currently only designed for offline applications [

10]. As it is still a draft, all the following results are preliminary only. Still, the goal of the MLDL, as described in the draft, is to establish support for the certification and approval process of AI-based systems in aviation. To achieve this, the MLDL aims to define and organize the objectives and outputs of the systems in an easy to comprehend manner, suitable also for non-experts in the field of AI and ML. These objectives are closely aligned with the DAL as well as the Software Assurance Level [

10]. However, compared to the W-shaped process developed by EASA [

6], the MLDL does not require a specific development process but rather provides a framework to support the development of AI-based systems in aviation in general. Nevertheless, there are many similarities but also some differences between the two frameworks worth exploring.

The MLDL is divided into development activities for both AI-based and traditional (sub)systems and V&V activities for those (sub)systems. The architecture of a system in the MLDL is segmented into two main parts, the System/subsystem Architecture and the Item Architecture. The MLDL process starts with the execution of the requirements phase, called System/Subsystem Requirements Process. This is similar to the proposed framework with the primary difference that in the proposed framework requirements can be directly derived from the ConOps, creating a continuous chain of trust. This chain of trust is essential for clearly defining all requirements and their corresponding rationales. Thus, ensuring that all relevant requirements of the system, its surrounding environment, and operational conditions are captured. Since the ConOps serves as the primary interface with the customer, all developments are based upon the requirements defined in it. Thus, it plays a crucial role in the proposed framework, while not present in the MLDL. Based on the results of this phase, the System/Subsystem Requirements Process, a set of (sub)system requirements, including the OD and ODD, can be derived.

Following, the results from the System/subsystem Architecture phase are utilized to define the ML Model Architecture in the MLDL, and correspondingly, in the proposed framework, the Requirements Allocated to AI/ML Constituent are derived. At this stage, the ML Requirements Process is divided into ML Data Requirements and ML Model Requirements. The ML Data Requirements guide the ML data management, while the ML Model Requirements guide the ML Model Design Process. In the W-shaped process, and thus also proposed framework, these processes are referred to as Data Management and Learning Process Management, leading to a similar output. This sets the stage for training and verifying the ML model, the ML Model Design Process, and subsequently implementing the ML model on the designated target platform, the ML Inference Model Design and Implementation Process and the Item Integration Process. Both approaches include feedback loops from model training back to learning process management, data management, and AI/ML requirements, allowing for iterative improvements during training and the learning assurance of the AI-based system. However, only the proposed framework integrates continuous improvement of the trained ML model, even after deployment.

Moving from implementation to testing, the AI-based system will be verified and validated against the different levels of requirements as defined previously. This process takes place on the right-hand side of the proposed framework and accordingly in the second half of the MLDL. While for the proposed framework, and also the W-shaped process it is based upon, this will again lead to a split after which traditional soft- and hardware items will be tested against the V-model. The MLDL, however, incorporates both the traditional and the AI-based (sub)system in one holistic process, allowing for a better overview of the whole development process. Nevertheless, while the MLDL, similar to the W-shaped process, stops at the System/Subsystem Requirements, the proposed framework follows through until the Acceptance Test phase, serving as the interface to all stakeholders, especially the customer, by verifying the ConOps. Moreover, the proposed framework is designed for the continuous development of the AI-based system by integrating ideas from DevOps. As such, compared to the MLDL, the development does not end with the release of the AI-based system, but focuses also on the operations, ensuring continuous improvement by utilizing feedback from the deployed system and real data.

The comparison between the W-shaped process from EASA [

6], see

Figure 1, the MLDL process from the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group [

10] and the newly introduced framework, see

Figure 3, enhances the understanding of safe AI system development. Comparing this framework to the MLDL creates a common understanding for the development of safe and secure AI-based systems. It emphasizes the high-level requirements derived from the ConOps, while the MLDL starts at a lower level of abstraction and thus later in the development of the full system. Additionally, the proposed framework integrates the operations cycle to utilize feedback from operations, which is crucial to evaluating and improving the system’s performance ensuring a safe and secure AI-based system. Ultimately, it appears to be compatible with the MLDL although the latter is more expressive at lower levels while the new framework is more oriented towards continuous development of AI-based systems.

7. Discussion

This work showed that future AI-based systems need a rigorous development process based on novel AI Engineering methodologies to ensure both the safety and security of such systems. To combat this problem, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has already provided the so-called W-shaped process, an advancement of the V-model, meant for AI-based systems. It is intended to be used in parallel to the V-model-based development of traditional soft- and hardware items in the development process of a complete system. However, the EASA learning assurance process has received criticism for its potential limitations as some of its objectives might be inherently unverifiable. Thus, the W-shaped process still lacks important features to ensure the safety and security of an AI-based system throughout its operational lifecycle. Moreover, the W-shaped process lacks continuous verification and validation due to its sequential design. For AI-based systems, this is, however, crucial to adhere to the dynamic nature of AI-driven requirements. The processes required to achieve not only continuous updates but also continuous verification and validation have already been manifested in other development processes, namely the established DevOps process. A naive implementation of the DevOps cycle is, however, also not suitable as it is not compatible with current aviation processes and certification standards. As the DevOps process also sees a rise in adoption in other safety-critical domains, such as automotive, the framework proposed in this work builds upon the W-shaped process by integrating aspects from DevOps to further improve and extend the W-shaped process.

The proposed novel process, an extension of the W-shaped process, aims to enforce more feedback loops through its more holistic approach by starting at the initial definition phase in which the Concept of Operations document is defined. Furthermore, the proposed process adds dedicated steps for the creation of both the Operational Domain as well as the Operational Design Domain and their corresponding verification steps, thus creating a more accountable process. Finally, the novel process integrates even more ideas and processes from DevOps into the W-shaped process by incorporating the operations phase firmly into the process. Including the operations phase in the process ensures that information from the operations of the developed AI-based system can flow back into the update of said system. This is the fundamental idea of continuous development and is required for the continuous verification and validation of any AI-based system, not only in aviation. It is essential for the Safety-by-Design-process in the field of AI Engineering. Furthermore, this work discusses how different Development Assurance Levels (DALs) lead to different requirements for the operations phase of the DevOps. Given the stringent certification requirements of systems with a high DAL, for these systems, it is recommended to go through multiple rounds of the process before submitting a system to certification with the subsequent release and deployment of updates to the AI/ML constituent of the AI-based system.

Nevertheless, even the proposed framework is not yet fully suitable for widespread adoption in aviation. Similar to the W-shaped process, as it is built upon it, it lacks compatibility with both unsupervised learning and reinforcement learning methods. Moreover, clear guidance on how the operations phase should be executed is still under investigation, and how this phase can be integrated into the current aviation processes, especially the certification process. Furthermore, some questions on the interaction of traditional soft- and hardware with AI-based systems are still open. For example, how to handle the integration and deployment of an updated AI-based system if this would require new hardware to also be deployed. Next, guidelines on the required amount of feedback from the operations phase to the development phase are missing. As well as guidelines on how exactly this data can be safely and securely transferred from the aircraft to the developers. Nevertheless, the proposed framework was shown to be compatible with the Machine Learning Development Lifecycle (MLDL) developed by the G34/WG-114 Standardization Working Group, a joint effort between EUROCAE and SAE. It is the overall goal of this work to enhance the field of AI Engineering for aviation leading to a safe and secure application of AI-based systems, whether they were developed with the here proposed framework or any other framework, as long as the focus shifts towards continuous development and integration to continuously improve any AI-based system deployed.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, a more accountable and holistic development process for the Safety-by-Design development of AI-based systems in safety-critical environments has been proposed. It extends the W-shaped process introduced by EASA, incorporating ideas from the DevOps approach. This novel process intends to ensure that the development follows a Safety-by-Design approach from the high-level system down to the AI/ML constituent. By following proven ideas from the field of AI Engineering, the proposed process allows for a continuous improvement of the AI-based system and, thus, a continuous verification and validation leading to a potentially certifiable AI-based system.

Future research will focus on the enhancement of the Safety- and Security-by-Design methodology for safety-critical AI-based systems considering measurable quality criteria, such as explainability, traceability, and robustness. Automating the methodology will ensure the systematic and strategic development and improvement of the AI-based system throughout the entire MLDL. Moreover, investigations on how the methodology can be further enhanced through AI-driven feature engineering will be conducted. Ultimately, the methodology will be applicable across different domains, such as space, transportation, and robotics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C., T.S., and A.A.; methodology, J.C., T.S., and A.A.; validation, J.C., A.A., and T.S.; investigation, J.C., A.A., and T.S.; resources, J.C.; visualization, V.W., J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., T.S., A.A., E.H., A.V., and S.H.; writing—review and editing, J.C., E.H., A.V., S.H., and U.D.; supervision, S.H., T.K., U.D., and F.K.; project administration, J.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACAS |

Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

| ADS |

Automated Driving System |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CI/CD |

Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment |

| ConOps |

Concept of Operations |

| DAL |

Development Assurance Level |

| DevOps |

Development Operations |

| DevSecOps |

Development Security Operations |

| EASA |

European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

| EUROCAE |

European Organization for Civil Aviation Equipment |

| HTL |

Human-in-the-Loop |

| IFE |

In-Flight Entertainment |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MLDL |

Machine Learning Development Lifecycle |

| MLOps |

Machine Learning Operations |

| OD |

Operational Domain |

| ODD |

Operational Design Domain |

| SAE |

Society of Automobile Engineers |

| SafeOps |

Safety Operations |

| V&V |

Verification and Validation |

References

- Bello, H.; Geißler, D.; Ray, L.; Müller-Divéky, S.; Müller, P.; Kittrell, S.; Liu, M.; Zhou, B.; Lukowicz, P. Towards certifiable AI in aviation: landscape, challenges, and opportunities. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C. The V-Model. Technical report, University of Karlskrona/Ronneby, 1999.

- Namiot, D.; Sneps-Sneppe, M. On Audit and Certification of Machine Learning Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 34th Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), Riga, Latvia; 11 2023; pp. 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiot, D.; Ilyushin, E. On Certification of Artificial Intelligence Systems. Physics of Particles and Nuclei 2024, 55, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Artificial Intelligence Roadmap 2.0. techreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), Postfach 10 12 53, 50452 Cologne, Germany, 2023.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). EASA Concept Paper: Guidance for Level 1 & 2 Machine Learning Applications. techreport, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), Postfach 10 12 53, 50452 Cologne, Germany, 2024.

- Vairo, T.; Pettinato, M.; Reverberi, A.P.; Milazzo, M.F.; Fabiano, B. An approach towards the implementation of a reliable resilience model based on machine learning. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2023, 172, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]