1. Introduction

Healthcare is currently witnessing a rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) applications, motivated by rising clinical demands, staff shortages, and the need to harness ever-growing volumes of patient data. The global AI-in-healthcare market, valued at approximately USD 19.27 billion in 2023, is forecasted to grow at an annual rate of more than 38% through 2030 [1]. This growth is driven by a variety of promising successes, including improvements in diagnostic imaging, automated patient monitoring, and the design of personalized treatment pathways, all of which demonstrate measurable gains in diagnostic accuracy and operational efficiency [2–4]. While early AI systems focused on discrete tasks such as rule-based expert systems for drug dosage calculations modern healthcare AI agents have evolved to incorporate large language models (LLMs), advanced machine learning, and generative AI. Instead of aiming to replace clinicians, these new-generation agents function as synergistic partners, providing real-time analysis of complex multimodal patient data. Their goal is to enhance clinical workflows, guide better therapeutic decisions, and personalize patient care [5–7]. Recent work has shown that, for certain clinical tasks, LLM performance remains relatively stable across different temperature settings challenging the assumption that lower temperature always improves clinical accuracy [8]. Simpler machine learning models, such as bag-of-words logistic regression, have also been shown to achieve competitive results for hospital resource management, especially in settings with limited computational infrastructure [9]. For instance, AI-enabled diagnostic systems have exhibited near-human or even above-human performance in detecting diseases like diabetic retinopathy and melanoma [10,11].

Despite these advances, implementing AI agents in healthcare still faces significant barriers. Data privacy and security regulations such as HIPAA in the United States and GDPR in Europe enforce rigorous standards for data governance, which can complicate integration with legacy electronic health record (EHR) systems. Many AI models also operate as “black boxes,” creating interpretability challenges that raise clinician skepticism and liability concerns particularly in high-stakes areas like oncology or intensive care [12]. Seamless EHR interoperability remains a pressing issue; systems must be designed to merge, store, and process heterogeneous clinical data without disrupting existing workflows [13]. To address these gaps, researchers and developers are advancing modular architectures that segment AI agents into specialized subsystems covering perception, reasoning, memory, and interaction. These modules align well with a continuum of autonomy that ranges from “Foundation Agents” providing basic automation to “Assistant Agents” offering guideline-based decision support, and finally to “Partner” and “Pioneer” agents capable of adaptive, evidence-driven strategy shifts or even novel treatment discovery [14,15]. Each level brings additional demands for trust, transparency, and regulatory assurance [16].

In this paper, we provide a comprehensive overview of AI agents in healthcare, examining how they can be systematically classified, deployed, and validated. We first review existing literature and describe four major categories of AI agents Foundation, Assistant, Partner, and Pioneer illustrating each with real-world applications. We then propose a roadmap and an integrated architecture that clarify how these agents can evolve from narrowly specialized systems to sophisticated tools that proactively support clinicians and researchers. Finally, we discuss the multifaceted challenges technical, organizational, and ethical that must be addressed for AI agents to fulfill their transformative potential in clinical settings. By unifying emerging trends and best practices, this paper aims to guide healthcare stakeholders practitioners, technologists, hospital administrators, and policymakers in planning and implementing AI agents that truly augment human expertise, improve patient outcomes, and align with the broader mission of ethical and efficient healthcare delivery.

2. Methods

To inform our analysis of AI agents in healthcare, we conducted a systematic review of literature published between 2020 and 2024. Our search encompassed major databases including IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, PubMed, and MEDLINE using key terms such as “AI agents,” “Artificial Intelligence,” “Machine Learning in healthcare,” “healthcare,” and “clinical decision support.” Studies were selected based on their emphasis on clinical applications, technical implementations, and real-world outcomes, with priority given to peer-reviewed publications and high-quality technical reports. We followed the PRISMA framework to ensure a transparent and reproducible selection process. Although no visual diagram is provided, our systematic approach is thoroughly documented in the text.

Insights from the review were synthesized into four primary themes: agent architectures, clinical applications, implementation challenges, and outcomes. These themes directly guided the development of our four-tier classification framework comprising Foundation, Assistant, Partner, and Pioneer agents and informed the modular roadmap for AI integration in healthcare detailed in subsequent sections. This systematic approach not only grounds our conceptual models in current research but also ensures that our practical guidelines reflect both technical innovations and clinical realities.

3. Types of AI Agents in Healthcare

Healthcare institutions worldwide are adopting a range of AI-driven systems that vary in how independently they carry out tasks, propose solutions, and adapt to new information.

Table 1 summarizes four major categories

Foundation,

Assistant,

Partner, and

Pioneer based on their autonomy and the complexity of their functions [17, 18]. Following the table, each subsection discusses these categories in greater detail, illustrating how AI solutions can progress from simple workflow aids to sophisticated, creative partners in patient care and medical discovery.

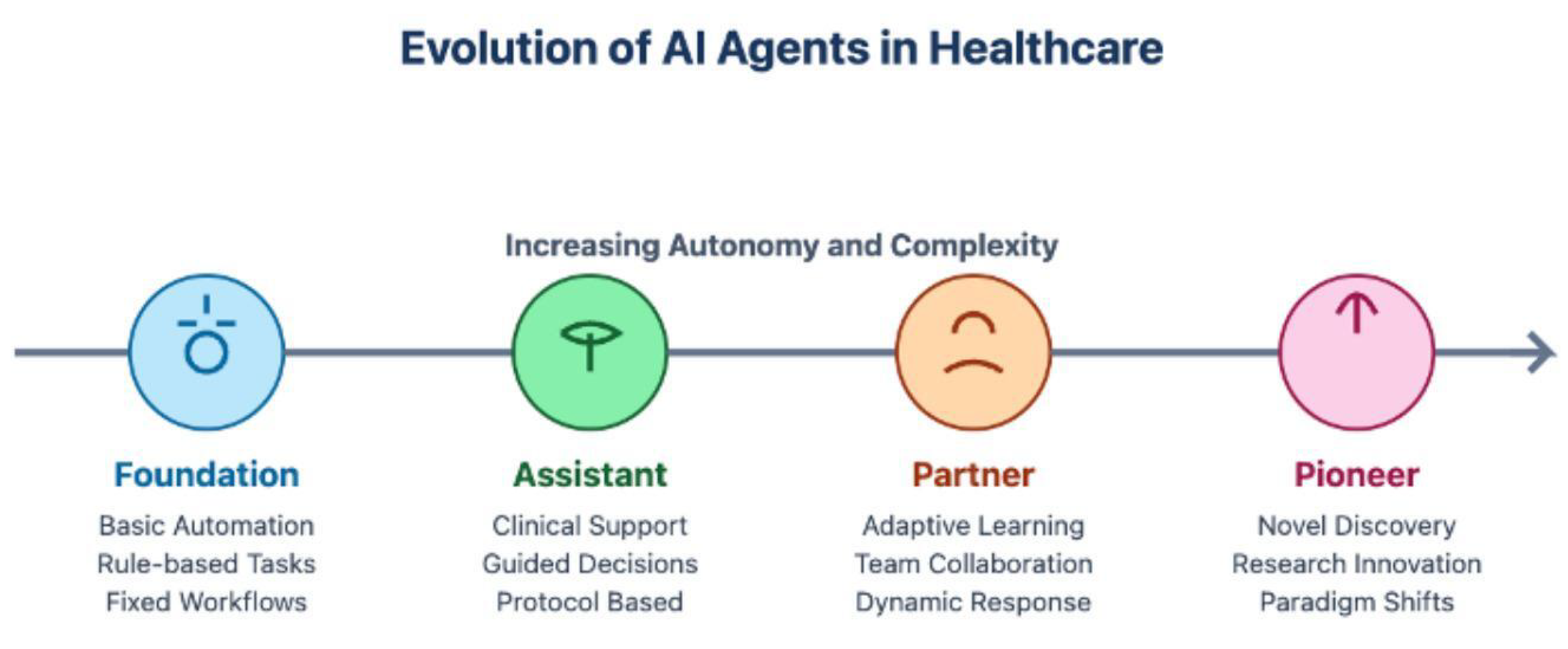

Figure 1 presents a temporal evolution framework that maps the progression of AI agents in healthcare, illustrating the interdependencies between successive development stages. This visualization extends beyond simple categorization by demonstrating how each advancement builds upon previous capabilities while introducing new dimensions of autonomy. The linear progression emphasizes an important architectural principle: more advanced agents do not replace their predecessors but rather augment them through sophisticated capabilities. For instance, while Pioneer agents introduce paradigm-shifting capabilities in research innovation, they inherently incorporate the rule-based reliability of Foundation agents and the protocol adherence of Assistant agents. This evolutionary model has significant implications for healthcare institutions’ AI implementation strategies, suggesting that robust foundation-level implementations are prerequisites for successful deployment of more advanced agents. The framework particularly highlights how

Dynamic Response capabilities emerge at the Partner level as a crucial steppingstone between protocol-based operations and novel discovery mechanisms, representing a critical transition in healthcare AI development.

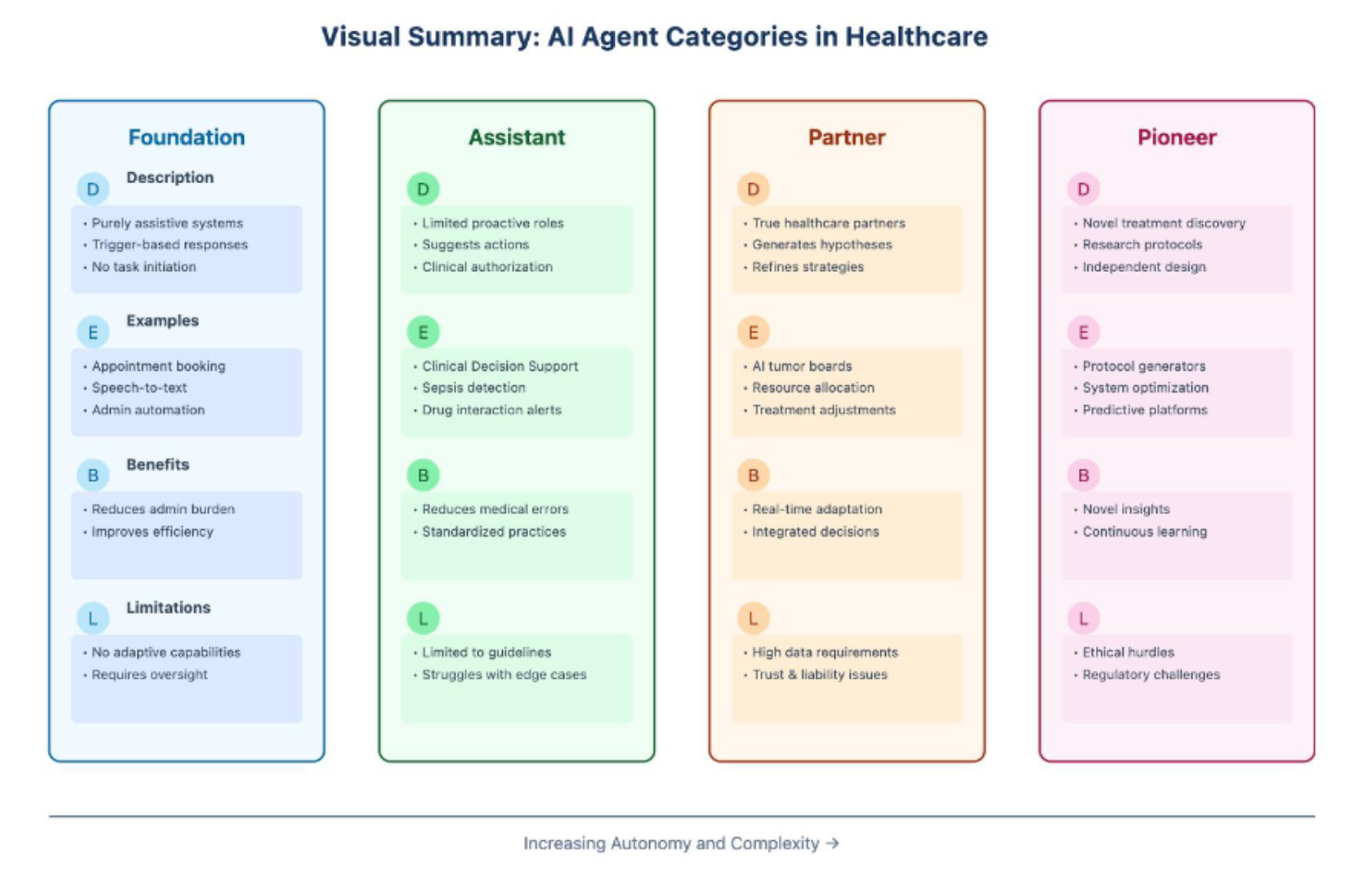

The classification framework presented in

Table 1 reveals a clear progression in AI agent capabilities, from basic task automation to sophisticated clinical decision support. This progression is further illustrated in fig:figure1,fig:figure2,fig:figure3, which provide visual representations of the relationships and characteristics outlined in the table. Each category in this framework represents a distinct evolutionary stage in healthcare AI, with specific technical requirements, operational considerations, and implementation challenges that warrant detailed examination. The following subsections explore each category in depth, beginning with Foundation Agents, which form the basis of healthcare AI implementations.

Figure 2.

DEBL (Description-Examples-Benefits-Limitations) Framework for Healthcare AI Agent Classification: A Comparative Analysis of System Capabilities and Constraints

Figure 2.

DEBL (Description-Examples-Benefits-Limitations) Framework for Healthcare AI Agent Classification: A Comparative Analysis of System Capabilities and Constraints

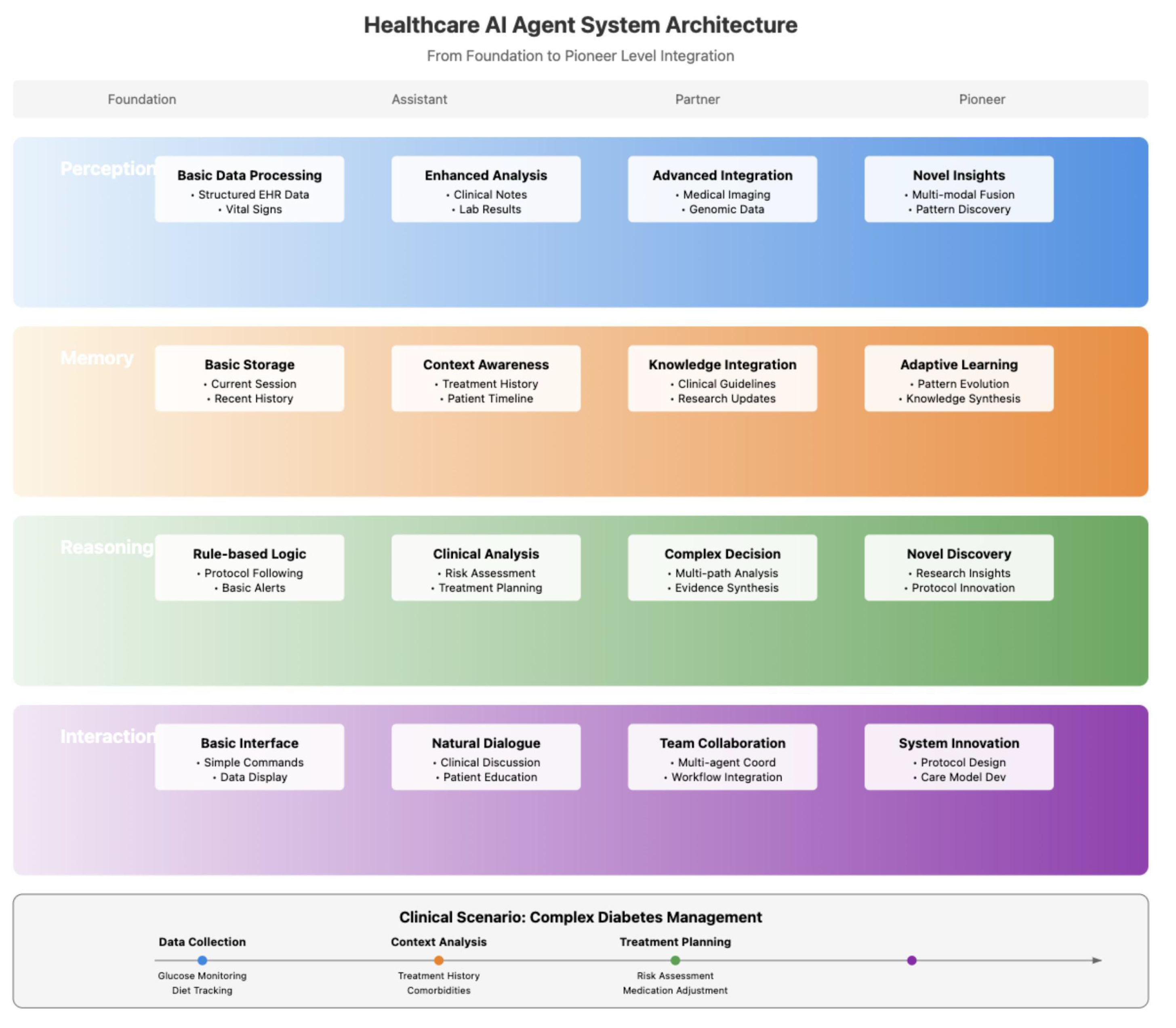

Figure 3.

Healthcare AI Agent System Architecture showing the progression from Foundation to Pioneer Level Integration. The architecture demonstrates how perception, memory, reasoning, and interaction modules evolve in sophistication across autonomy levels, illustrated through a complex diabetes management scenario.

Figure 3.

Healthcare AI Agent System Architecture showing the progression from Foundation to Pioneer Level Integration. The architecture demonstrates how perception, memory, reasoning, and interaction modules evolve in sophistication across autonomy levels, illustrated through a complex diabetes management scenario.

3.1. Foundation Agents

As outlined in

Table 1, Foundation Agents represent the entry point for healthcare AI implementation, characterized by their focus on discrete services and trigger-based tasks. Foundation agents are designed to perform basic, trigger-based tasks in healthcare, often operating in the background to minimize manual effort and streamline workflows. These agents respond to explicit user inputs, such as a clinician’s command to schedule a patient follow-up or transcribe dictated notes into an electronic health record (EHR). A prominent example of this category is commercial speech-to-text software, such as Nuance’s Dragon Medical One, which automates clinical documentation without offering diagnostic or therapeutic recommendations. Similarly, chatbots designed for appointment scheduling or handling front-desk inquiries fall under this foundational tier.

These agents excel at performing a single set of tasks with high reliability and minimal autonomy, thereby reducing repetitive workloads for clinicians and improving operational efficiency. However, their functionality is limited to predefined protocols, and they lack the ability to adapt spontaneously or operate beyond their initial programming. As a result, human oversight remains critical to ensure their safe and effective use. Foundation-level agents are often favored by healthcare organizations due to their low implementation risks, minimal data integration requirements, and limited need for clinical validation. Recent advancements in natural language processing (NLP) have further enhanced the capabilities of such agents, enabling more accurate and context-aware transcription services [16]. For instance, OpenAI’s Whisper, a state-of-the-art speech recognition model, has demonstrated significant improvements in medical transcription accuracy, making it a promising tool for healthcare documentation [18].

3.2. Assistant Agents

Building upon the foundation tier described in

Table 1, Assistant Agents introduce limited proactive capabilities while operating within clearly defined parameters. Assistant agents represent a more advanced category of AI systems, capable of proactively recommending actions based on patient-specific data, such as lab results, reported symptoms, or medication profiles. These agents operate within a constrained scope, analyzing multifactorial clinical data to support decision-making without venturing into uncharted territory. A well-known example of assistant agents is AI-driven sepsis detection systems integrated into major EHR platforms like Epic and Cerner. These systems continuously monitor patient vitals for patterns indicative of early sepsis and alert clinicians when predefined thresholds are met, suggesting potential investigations or interventions [21].

Similarly, medication reconciliation tools leverage AI to flag harmful drug interactions, while advanced triage modules route complex cases to the appropriate specialists. Despite their ability to handle intricate reasoning tasks, assistant agents remain bound by established clinical guidelines and protocols. They cannot independently create new care pathways or radically alter treatment plans. Nevertheless, their ability to analyze complex datasets and provide actionable recommendations significantly reduces human effort, minimizes error rates, and enhances consistency in routine clinical decisions. Recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of AI-driven clinical decision support (CDS) systems in improving patient outcomes. For example, a 2023 study published in Nature Digital Medicine demonstrated that an AI-based CDS tool reduced sepsis mortality rates by 20% through early detection and intervention [21]. Additionally, AI-powered medication reconciliation tools have been shown to reduce adverse drug events by up to 30%, underscoring their value in enhancing patient safety [19]. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into healthcare workflows is expected to deepen, further augmenting the capabilities of clinicians and improving the quality of care.

3.3. Partner Agents

Partner Agents, as categorized in

Table 1, represent a significant advancement in healthcare AI capability, functioning as true team members in clinical settings. Partner agents represent a transformative tier of AI systems that integrate dynamically into clinical workflows, co-managing patient care and research protocols through adaptive reasoning. These agents move beyond passive anomaly detection to propose evolving, context-aware strategies. For example, AI-driven “virtual tumor boards” synthesize multimodal data including genomic profiles, imaging reports, and historical treatment outcomes to recommend personalized oncology regimens. A 2024 study demonstrated an autonomous AI agent for clinical decision-making in oncology, which achieved 93.6% accuracy in drawing conclusions and 94% completeness in recommendations by coordinating specialized tools for genomic analysis and guideline adherence [19]. Such systems may adjust dosing schedules, suggest combination therapies, or identify clinical trial eligibility in response to drug resistance, thereby addressing complex, longitudinal care challenges [20].

In emergency medicine, adaptive triage systems exemplify partner agents by dynamically reprioritizing diagnostic tests and staff assignments as real-time patient data arrives. Oracle Health’s Clinical AI Agent, for instance, automates documentation while proposing clinical follow-ups and synchronizing data across workflows, reducing clinician documentation time by 41% [21]. However, the increased autonomy of partner agents necessitates robust transparency mechanisms and stringent data security protocols. Healthcare professionals emphasize the need for interpretable AI models and ethical frameworks to mitigate risks of bias or inequitable resource allocation [22]. Continuous human feedback loops and compliance with standards like HIPAA are critical to maintaining trust in these systems [23].

3.4. Pioneer Agents

At the apex of the classification framework presented in

Table 1, Pioneer Agents embody the most advanced implementation of healthcare AI. Pioneer agents push the boundaries of clinical innovation, operating beyond established guidelines to uncover novel therapeutic pathways or operational strategies. These systems leverage generative AI and large language models (LLMs) to identify unrecognized patient subgroups or propose experimental interventions. For instance, autonomous AI platforms in oncology have demonstrated the ability to synthesize genomic data and clinical trial outcomes to suggest molecular targets for drug development [25]. Similarly, initiatives like Microsoft’s Azure Health Bot integrate predictive analytics to optimize resource allocation during pandemics, autonomously adjusting infection-control protocols based on emerging data [24].

Such systems raise profound ethical and regulatory questions. A 2024 qualitative study found that 33% of healthcare professionals prioritize data privacy and algorithmic transparency when deploying AI for resource allocation, underscoring concerns about equity and patient autonomy [26]. For example, AI-driven drug discovery platforms, while accelerating timelines by 30–50%, must navigate stringent validation processes to avoid unapproved or unsafe protocols [27]. Regulatory frameworks like the EU’s AI Act and FDA guidelines emphasize the need for “human-in-the-loop” oversight, particularly for pioneer agents operating in research pilots [28]. Despite these challenges, pioneer systems hold promise for breakthroughs in precision medicine, such as Tempus’s AI-driven cancer therapies, which tailor treatments using genetic and clinical profiles [29].

3.5. Practical Implications for Healthcare

The categorization of AI agents into foundation, assistant, partner, and pioneer tiers clarifies their roles and implementation challenges. Foundation agents, such as Nuance’s speech-to-text software, optimize administrative tasks but lack clinical autonomy. Assistant agents, like Epic’s sepsis alerts, enhance decision-making within predefined guidelines but require human validation. Partner agents, exemplified by Oracle’s Clinical AI Agent, demand rigorous transparency and interoperability with EHRs to co-manage care [31]. Pioneer agents, while transformative, necessitate ethical governance to balance innovation with safety [32].

Institutions often adopt a phased approach: 32% of healthcare professionals prioritize seamless AI integration into existing workflows before advancing to partner-level systems [33]. For example, AtlantiCare’s collaboration with Oracle improved workflow efficiency by 66 minutes daily, demonstrating the value of incremental adoption. Long-term success hinges on addressing ethical concerns such as data privacy (cited by 33% of clinicians) and algorithmic bias through interdisciplinary collaboration and regulatory alignment [34]. As governance matures, pioneer agents may unlock personalized medicine paradigms, though their deployment remains contingent on public trust and robust validation frameworks [35].

Figure 2 employs the DEBL framework to highlight how each tier of AI agents builds upon the constraints of the previous one. For instance, the oversight required by foundation agents becomes a need for strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines in assistant agents, which then reveals deeper ethical and governance hurdles at the pioneer level. By mapping these evolving interdependencies, the DEBL framework underscores the importance of organizational readiness and transparent oversight throughout the adoption process. Ultimately, it provides a structured roadmap for healthcare systems seeking to balance innovation with patient safety, regulatory requirements, and clinician trust.

4. Roadmap For Building AI Agents In Healthcare

AI agents in healthcare are best conceived as compound systems composed of specialized modules commonly perception, interaction, memory, and reasoning—each targeting a distinct aspect of clinical operations (see

Figure 1) [25,26]. In light of the autonomy categories discussed in

Section 3, these modules can be combined to produce agents ranging from foundation-type solutions that simply parse and store clinical data, all the way up to pioneer-level systems capable of uncovering novel treatment paradigms [17,27]. The perception module enables an agent to acquire and interpret data from various clinical sources (e.g., EHR text, radiology images, biosensor streams), while memory and learning functions allow it to retain key medical information over time and adapt to new evidence or user needs [28]. Interaction with clinicians, patients, and other systems remains critical, especially when assisting in real-time decision-making [29]. The reasoning module then synthesizes this information to form data-driven plans or recommendations, ultimately executing tasks such as personalized treatment suggestions or automated alerts [30].

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive architectural framework that illustrates how these core modules evolve across different autonomy levels. In the perception layer, capabilities progress from basic data processing of structured EHR data and vital signs at the foundation level to sophisticated multi-modal fusion and pattern discovery at the pioneer level [31]. The memory module advances from simple session storage to adaptive learning with knowledge synthesis[21], while reasoning capabilities expand from rule-based logic to novel discovery and protocol innovation. The interaction layer evolves from basic interfaces to system-level innovations in care model development. This progression is exemplified in the figure’s clinical scenario of complex diabetes management, where the system integrates data collection, context analysis, and treatment planning in a coordinated workflow[32].

Beyond isolated proof-of-concept models, modular design offers a scalable path for deploying these AI agents in dynamic healthcare settings. Traditional workflow systems, resembling container-based or sequential tools used in biomedical research, can be relatively static: once configured, they often require manual updates to support new data modalities or additional tasks[33]. By contrast, an assistant agent or partner agent can learn on the fly: it might discover and integrate new resources or modify its analytical pipelines to reflect evolving clinical protocols[34]. As shown in

Figure 1, foundation-level agents typically handle basic data processing and rule-based logic, focusing on structured data and simple command interfaces. For instance, a foundation-level system might only rely on vitals and lab results to handle triage, whereas a more advanced partner-level agent could later incorporate radiology data or genetic testing to better assess patient status[35].

Modern hospitals already generate a variety of multimodal data—lab tests, EHR notes, imaging, and wearable ECG signals making them ideal for the flexible pipelines used by higher-autonomy agents [36]. At the pioneer tier, as shown in

Figure 3, agents can achieve novel insights through multi-modal fusion and pattern discovery, enabling innovative protocol design and advanced care models [37]. They might even integrate telehealth data with historical patient trajectories to refine risk predictions and deliver truly personalized care. However, as noted in

Section 3.4, such high-autonomy systems also demand rigorous oversight to ensure safety and compliance.

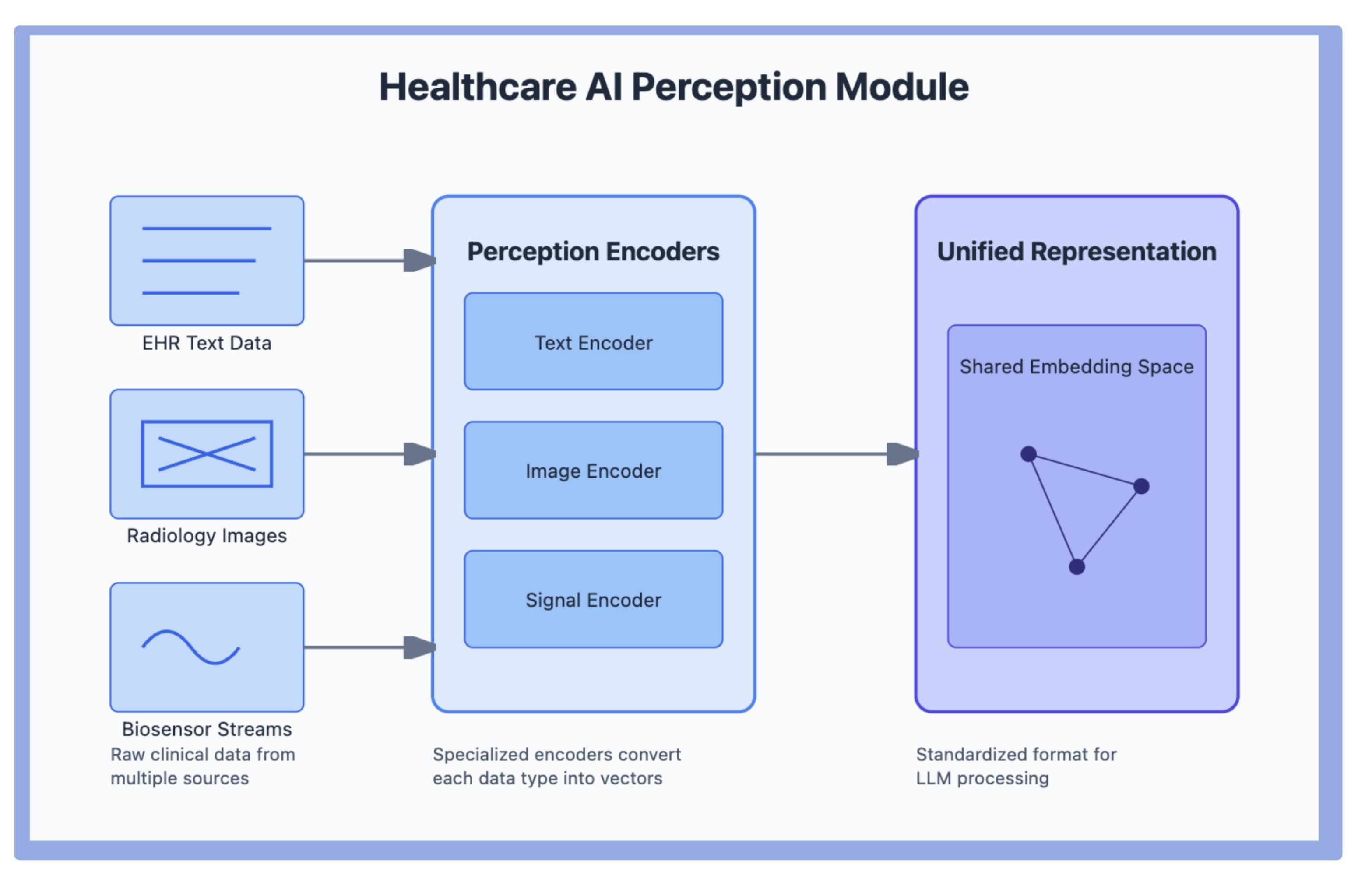

4.1. Perception Modules

Perception modules enable large language model (LLM)-based AI agents to interpret and interact with the extensive data landscape found in healthcare environments. Rather than focusing solely on research settings (e.g., microscopy or biochemical assays), healthcare-centric perception modules gather inputs from clinical workflows, hospital staff, and potentially other AI agents. These inputs can span EHR text, diagnostic images, continuous patient-monitoring data, and patient-generated information (e.g., from wearables or apps) [38]. The more sophisticated the agent, the more it aligns with the higher-autonomy categories discussed earlier, as it not only collects data but also integrates contextual cues from clinicians or from assistant-level or partner-level solutions in the hospital [39].

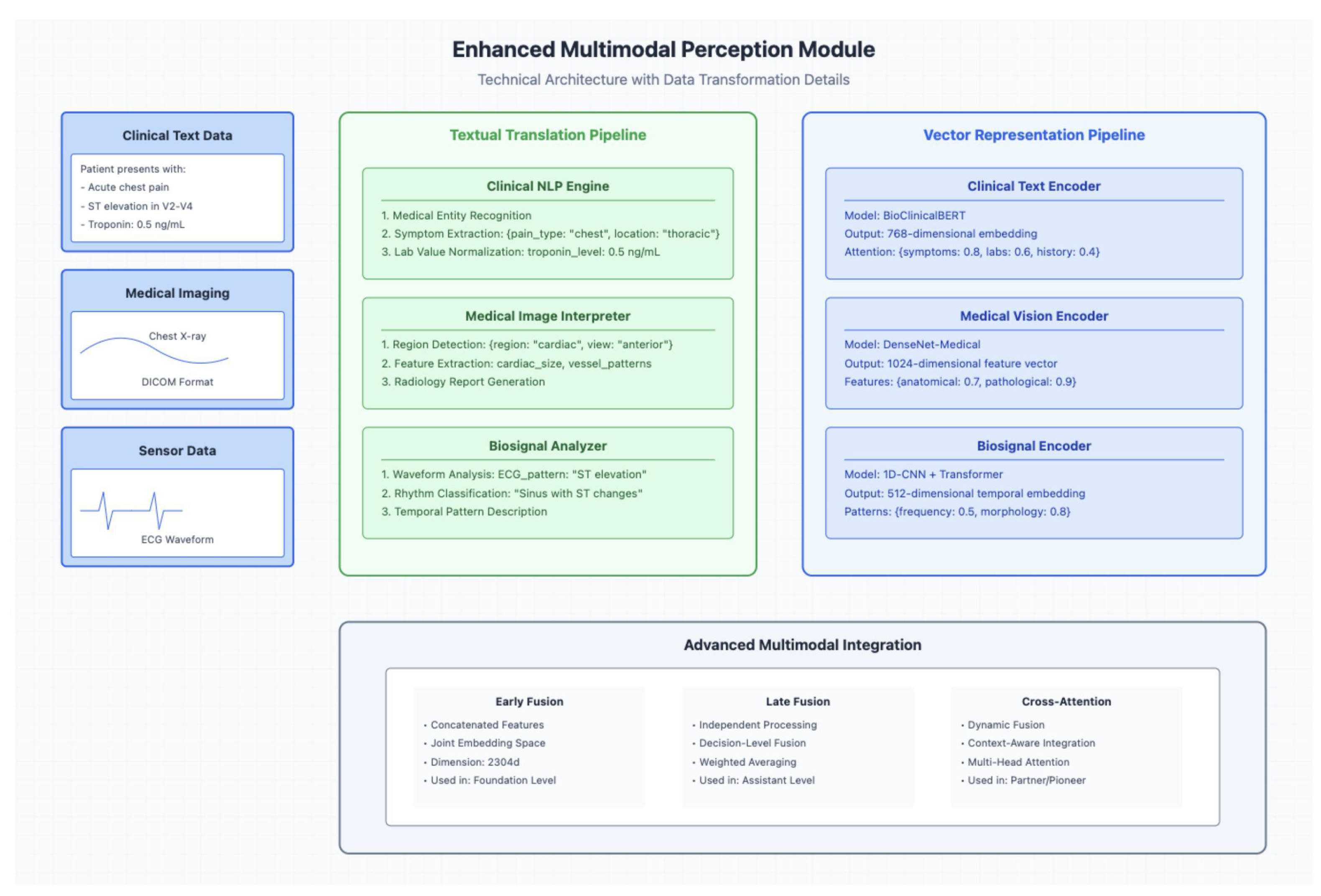

In

Figure 4, it shows how different data streams—EHR text, radiology images, and biosensor outputs—are transformed into a unified representation for LLM processing [40]. By encoding each input type (e.g., text, images, signals) into a shared embedding space, the system enables the agent to correlate and interpret heterogeneous clinical data. A foundation-level agent might only handle structured text or vitals, while advanced assistant or partner agents can integrate additional signals as they become available, enabling real-time adaptation.

The most straightforward way for an LLM-based agent to “perceive” its environment is through natural language—for instance, by interpreting clinician queries or summarizing patient records. Yet, effective patient care often requires a multimodal approach: combining textual notes with radiological images or attaching continuous monitoring data to a patient’s profile. As illustrated in

Figure 4 (

Section 4), specialized encoders for text, images, and sensor outputs facilitate this broader perspective [41]. The result is a cohesive, flexible system that can scale from foundation-level tasks to more complex analyses, in line with the agent categories introduced earlier.

4.1.1. Multimodal Perception Modules

Many healthcare AI agents—especially those aiming for partner or pioneer-level functionality must handle multiple data types simultaneously, such as clinical text, medical images, and sensor-based signals. Designing these multimodal perception modules generally involves aligning an LLM with specialized pipelines for each input type, ensuring coherent interpretations of patient conditions and the ability to adapt to evolving contexts.

In

Figure 5, three key pipelines: one for text (clinical NLP), one for imaging, and one for sensor data (e.g., ECG). In a suspected acute cardiac event, for example, the system processes clinician notes documenting chest pain and ST elevation, chest X-ray images in DICOM format, and real-time ECG signals indicating ST changes. Each pipeline employs specialized encoders—such as region detection for imaging or pattern recognition for ECG—to extract salient features.

Next block in

Figure 5, the multimodal perception system processes three distinct data streams through specialized pipelines. The Clinical NLP Engine handles text data, performing medical entity recognition, symptom extraction, and lab value normalization as demonstrated in the example of processing acute chest pain symptoms and troponin levels. Simultaneously, the Medical Image Interpreter processes imaging data through region detection and feature extraction, while the Bio signal Analyzer processes sensor data like ECG waveforms through specific pattern recognition steps.

By employing a unified representation, this architecture becomes a foundational element for both individual AI agents and multi-agent systems. Multiple specialized agents in a hospital can share the same perception framework, maintaining domain-specific expertise while benefiting from a common data format. This not only promotes collaborative decision-making but also preserves the clinical nuance of the original data. Building on the perception and interaction methods described in earlier sections, these multimodal modules facilitate increasingly advanced levels of autonomous operation in complex healthcare settings.

4.2. Conversational Modules

Large language models (LLMs) have reached a point where AI agents can reliably interpret natural language inputs, paving the way for chat-based interfaces that resemble human-to-human dialogues [38]. In healthcare, these conversational modules allow clinicians, nurses, or even patients to interact with the agent using straightforward text or voice messages rather than navigating complex dashboards. As the system evolves from foundation toward partner-level autonomy, conversational modules maintain a rolling history of each interaction, providing context and enabling nuanced, context-aware responses [38,42].

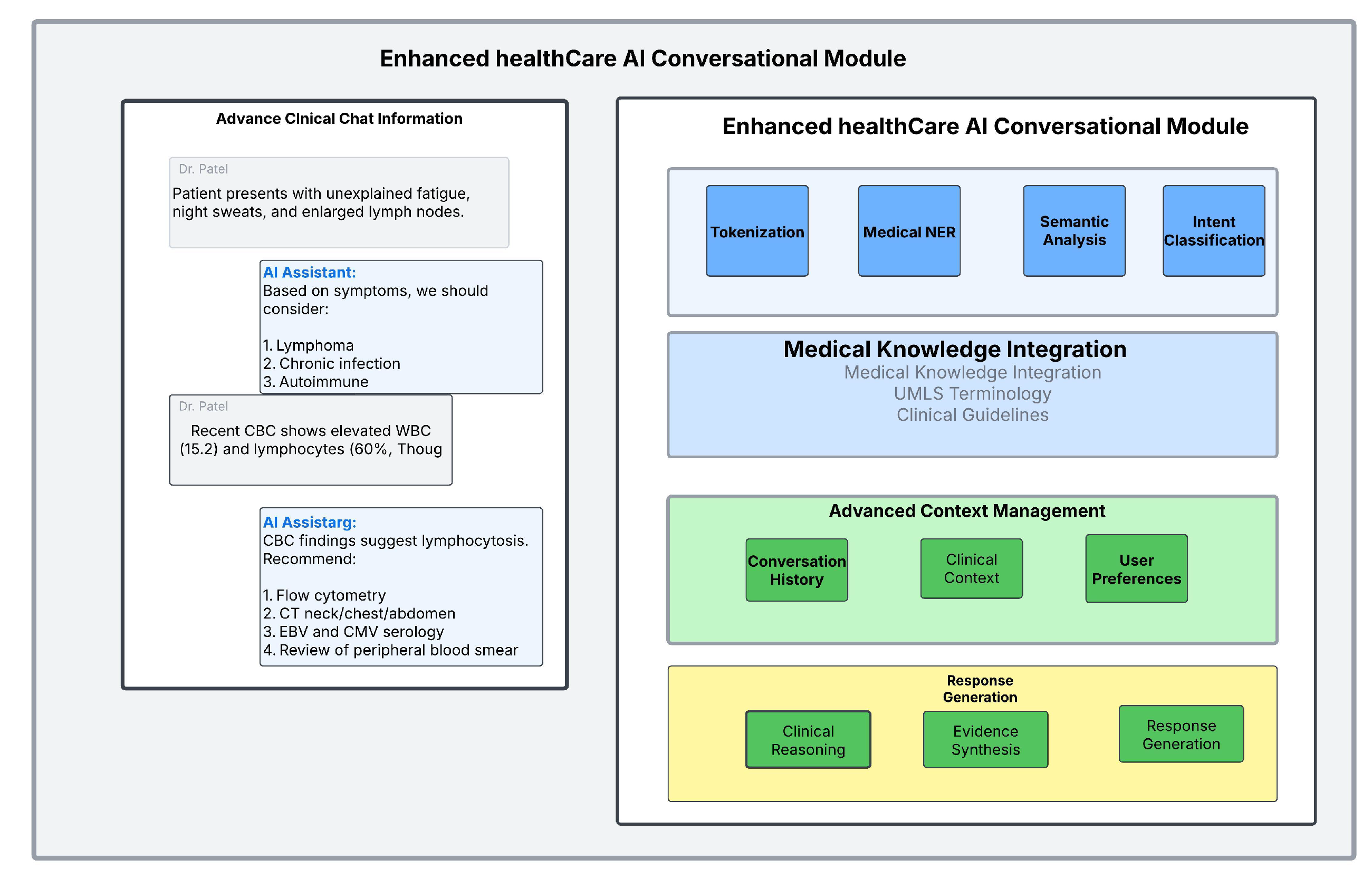

In

Figure 6, it demonstrates both the practical interface (left panel) and the underlying NLP architecture (right panel). A clinical chat interface allows an AI Assistant to discuss a patient case with a physician, while a sophisticated language processing pipeline handles tokenization, medical named entity recognition (NER), semantic analysis, and intent classification [42,43]. The example shown in the figure highlights how the system processes symptoms (e.g., fatigue, night sweats, enlarged lymph nodes) and lab findings (e.g., CBC results) to generate differential diagnoses and recommend follow-up tests [38].

By leveraging retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) or similar retrieval methods, the agent can incorporate historical chat logs and patient records into adaptive workflows [43]. An advanced context management layer tracks conversation history, clinical context, and user preferences, enabling coherent, contextually appropriate answers. For example, if a clinician references a patient’s recent lab results, the agent can retrieve and interpret that information before suggesting next steps. The response generation component, supported by evidence synthesis and clinical reasoning, ensures that recommendations are both clinically sound and well-substantiated [42,43].

Conversational logs can also be audited for quality assurance, which is vital in regulated healthcare environments. Such chat interfaces not only improve the user experience but also encourage clinical initiative in exploring AI-driven insights. As these modules scale up, they become especially relevant in collaborative or pioneer-level agents that adapt dynamically to changing patient conditions or hospital protocols [43].

4.3. Interaction Modules

Although chat-based interfaces are key for human-to-AI conversations, healthcare professionals also rely on analytics tools and specialized software. AI agents thus need robust interaction modules that let them integrate into these diverse systems. Concretely, the modules support agent-human interaction for requests such as “Schedule a follow-up,” multi-agent collaboration for interdepartmental tasks like ordering labs, and tool/platform integration for tasks ranging from bed management to data visualization. An agent trained only on broad, non-healthcare corpora might struggle with domain-specific nuance, underscoring the importance of specialized fine-tuning—particularly for more advanced assistant or partner agents. Through careful design of these modules, the agent can operate within the day-to-day clinical workflow, reduce manual overhead, and deliver precise, context-aware insights. Ultimately, the difference among foundation, assistant, or partner systems can hinge on how fluently they interact with existing tools and how effectively they align with healthcare-specific protocols [39].

4.3.1. Agent–Human Interaction Modules

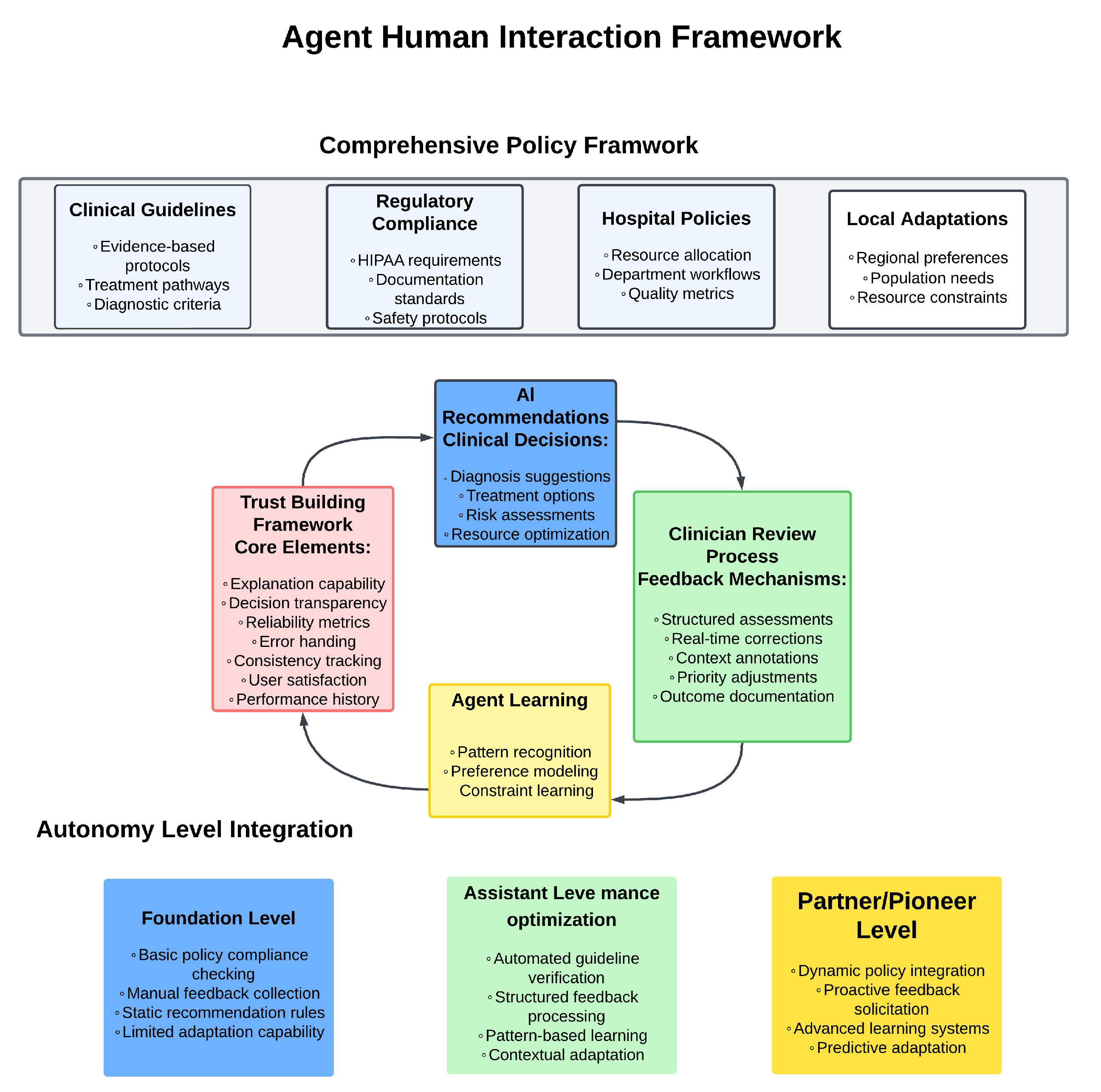

Agent–human interaction modules ensure that the AI’s outputs remain aligned with the real-world needs and institutional guidelines of clinicians and administrative staff. As shown in

Figure 7, this alignment is achieved through a comprehensive policy framework that encompasses clinical guidelines, regulatory compliance, hospital policies, and local adaptations [39]. The framework ensures that AI recommendations whether for diagnosis, treatment options, or resource optimization are consistently governed by evidence-based protocols while adhering to HIPAA requirements and facility-specific workflows [39].

At the core of these interactions is a trust-building framework that incorporates explanation capability, decision transparency, and reliability metrics [44]. These elements enable clinicians to understand and verify AI recommendations through structured assessments and real-time corrections. For instance, if a pediatrician clarifies that a certain medication is off-limits for young patients, an assistant-level or partner-level agent can factor that constraint into subsequent recommendations through its constraint learning mechanism [45]. The clinician review process provides systematic feedback through structured assessments, context annotations, and outcome documentation, creating a continuous improvement loop [44].

The framework’s effectiveness scales across different autonomy levels, from foundation-level systems with basic policy compliance checking and manual feedback collection, to assistant-level implementations featuring automated guideline verification and pattern-based learning. At the partner/pioneer level, the system achieves dynamic policy integration and proactive feedback solicitation, enabling more sophisticated adaptations to clinical needs while maintaining rigorous ethical and clinical review standards. This graduated approach to autonomy ensures that as AI systems become more capable, their interactions with healthcare professionals remain transparent, trustworthy, and aligned with institutional requirements [44].

4.3.2. Multi-Agent Interaction

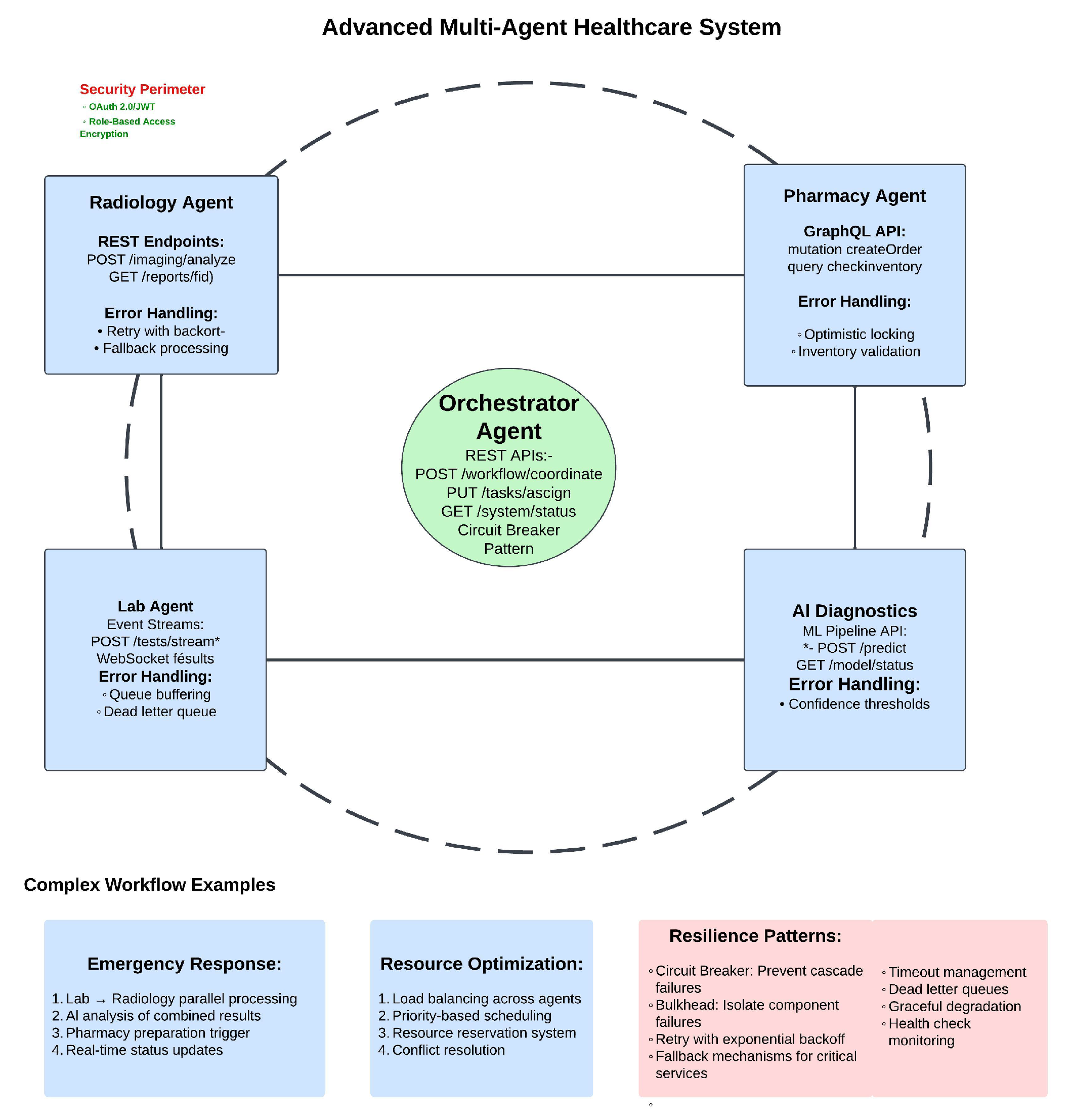

Complex tasks such as managing patient flow across different specialties or coordinating large hospital resources—often exceed the capability of a single agent. Multi-agent frameworks address this gap by allowing specialized agents in pharmacy, radiology, or operating-room logistics to cooperate. As shown in

Figure 8, this cooperation is achieved through a centralized Orchestrator Agent that coordinates interactions between specialized components: Radiology Agent handling imaging analysis, Lab Agent managing test streams, AI Diagnostics processing predictions, and Pharmacy Agent controlling medication orders [46].

The system’s architecture implements secure and resilient communication patterns. Each specialized agent exposes specific APIs—REST endpoints for radiology, GraphQL for pharmacy, WebSocket streams for lab results—all protected within a security perimeter using OAuth and role-based access control. Error handling mechanisms are tailored to each agent’s function, from retry-with-backoff in radiology to optimistic locking in pharmacy, ensuring robust operation during system stress.

Complex workflows, as illustrated in the figure’s examples, demonstrate how these agents collaborate in real-world scenarios. During emergency response, parallel processing of lab and radiology results feeds into AI analysis, triggering pharmacy preparations while maintaining real-time status updates. Resource optimization is achieved through load balancing, priority-based scheduling, and conflict resolution mechanisms [46]. The system’s resilience patterns—including circuit breakers, bulkhead isolation, and graceful degradation—ensure reliable operation even when individual components fail [46].

This sophisticated multi-agent architecture enables not just foundation or assistant agents, but also partner systems that orchestrate tasks at scale. Though pioneer-level agents might propose novel hospital management strategies through collective feedback, the built-in oversight mechanisms and security controls ensure safe and accountable operation.

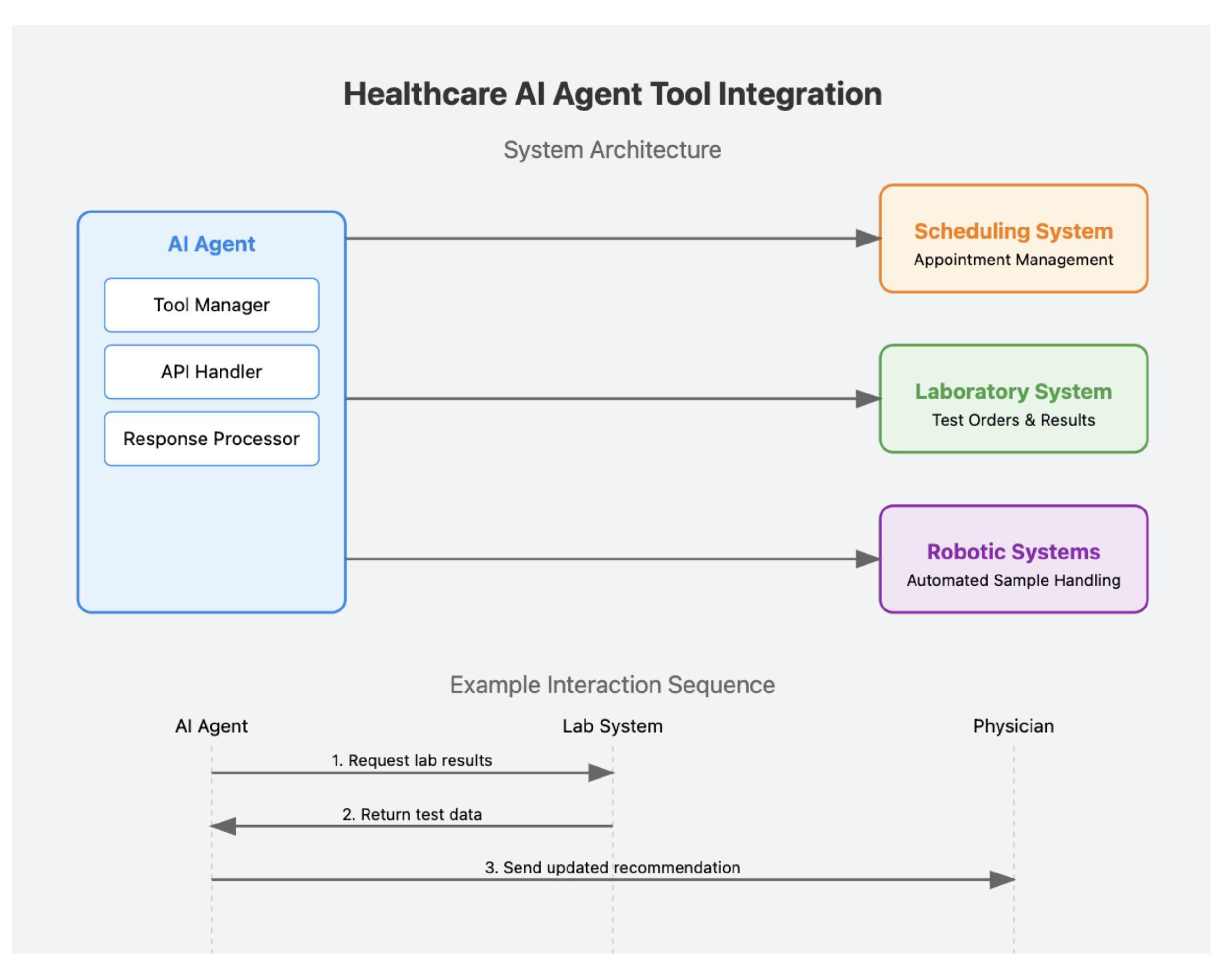

4.4. Tool Use

Healthcare AI agents frequently rely on external tools, from hospital information system APIs to robotic devices handling lab workflows. By invoking structured commands, an agent can automate scheduling or glean updated lab results without forcing clinicians to navigate multiple platforms[47]. As shown in

Figure 9, this integration is achieved through a structured system architecture where the AI agent interfaces with multiple healthcare systems from appointment management to automated sample handling through specialized components that manage tools, handle APIs, and process responses[48–50].

Examples from outside healthcare such as ChemCrow [51] or WebGPT [52] demonstrate how bridging third-party tools extends functionality. In a hospital context, this is illustrated by the figure’s interaction sequence, where the AI agent seamlessly coordinates with laboratory systems to request results and provide physician recommendations. More advanced assistant or partner agents might adaptively pick the best drug-interaction resource depending on a patient’s evolving prescription list. This ability to learn which tools to deploy under varied conditions can begin to approximate pioneer-level autonomy, although the agent must remain compliant with privacy regulations and validated for each tool it uses.

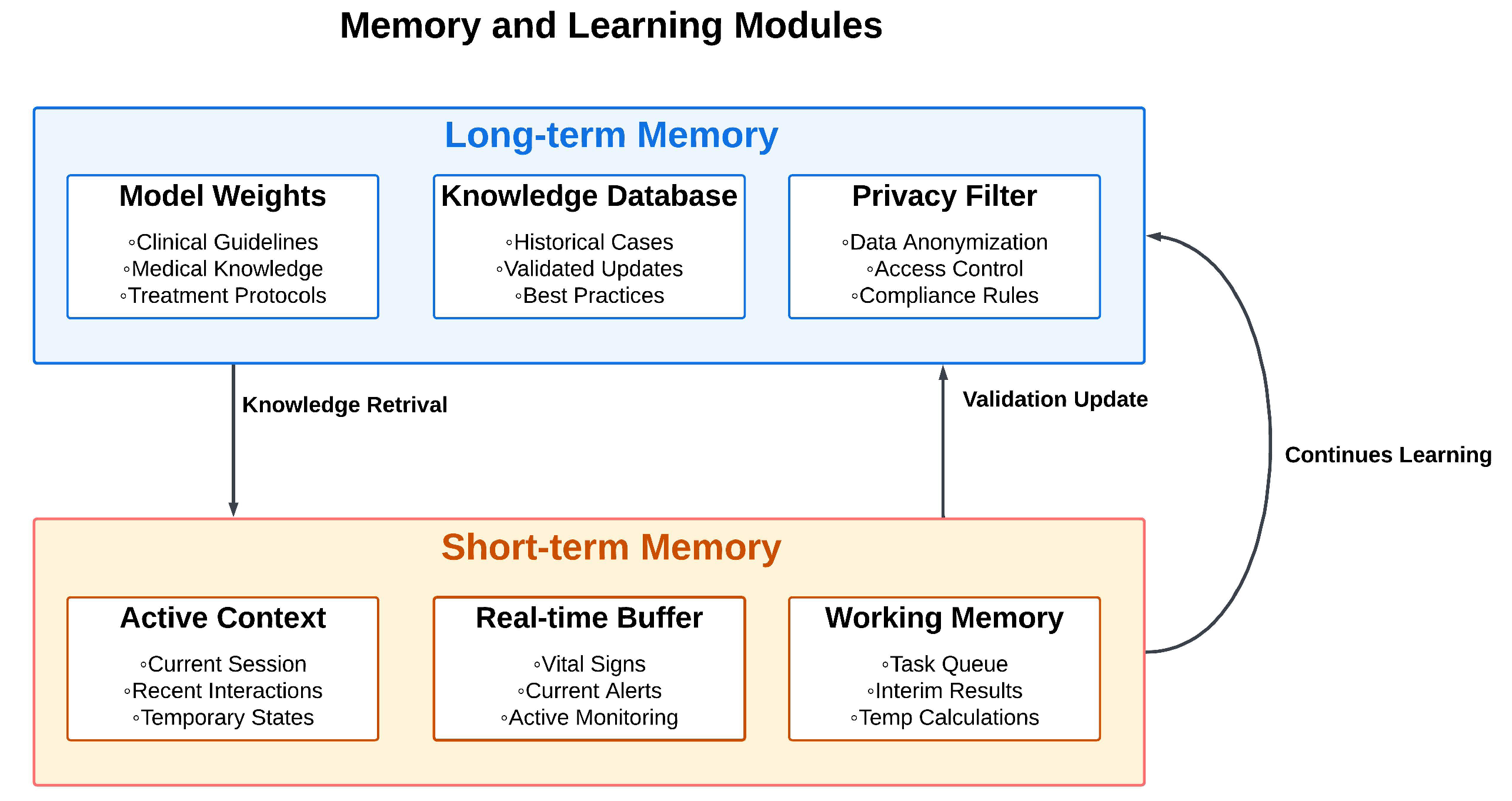

4.5. Memory and Learning Modules

In healthcare, an agent’s memory modules are pivotal for tracking patient encounters, clinical data, and institutional policies. As shown in

Figure 10, long-term memory is structured into three key components: Model Weights storing clinical guidelines and treatment protocols, Knowledge Database maintaining historical cases and validated updates, and Privacy Filter ensuring data anonymization and compliance. This memory can be embedded in the model’s weights or stored externally in curated databases, ensuring the agent remains updated on guidelines or drug formularies without overwriting previously learned knowledge [53,54].

Short-term memory, represented in the lower portion of the figure, holds contextual details relevant to a single patient interaction or a specific episode of care, discarding them afterward if needed. The continuous learning cycle shown by the feedback arrow demonstrates how partner agents might recall a patient’s early response to a drug and refine a second-line therapy, while a pioneer agent might accumulate insights across multiple patients to hypothesize novel care pathways. The key is continuous improvement without succumbing to catastrophic forgetting or data-security lapses [55].

Active Context for managing current sessions and recent interactions, Real-time Buffer for handling vital signs and current alerts, and Working Memory for task queues and interim calculations. This structure is particularly valuable for real-time interactions. An AI chatbot may store the preceding lines of dialogue to maintain continuity when recommending next steps. In more sophisticated scenarios, such as medical robotics, continuous environmental feedback (telemetry, vitals, staff inputs) informs immediate decision-making.

The figure shows how knowledge retrieval flows from long-term to short-term memory, while validation updates flow back, creating a dynamic learning system. As soon as the encounter concludes, these ephemeral details can be archived or wiped, dependent on privacy policies. An assistant-level chatbot may only need short-term memory for a routine consultation, whereas a partner-level system might track multiple care episodes or orchestrate collaborative tasks across an entire ward.

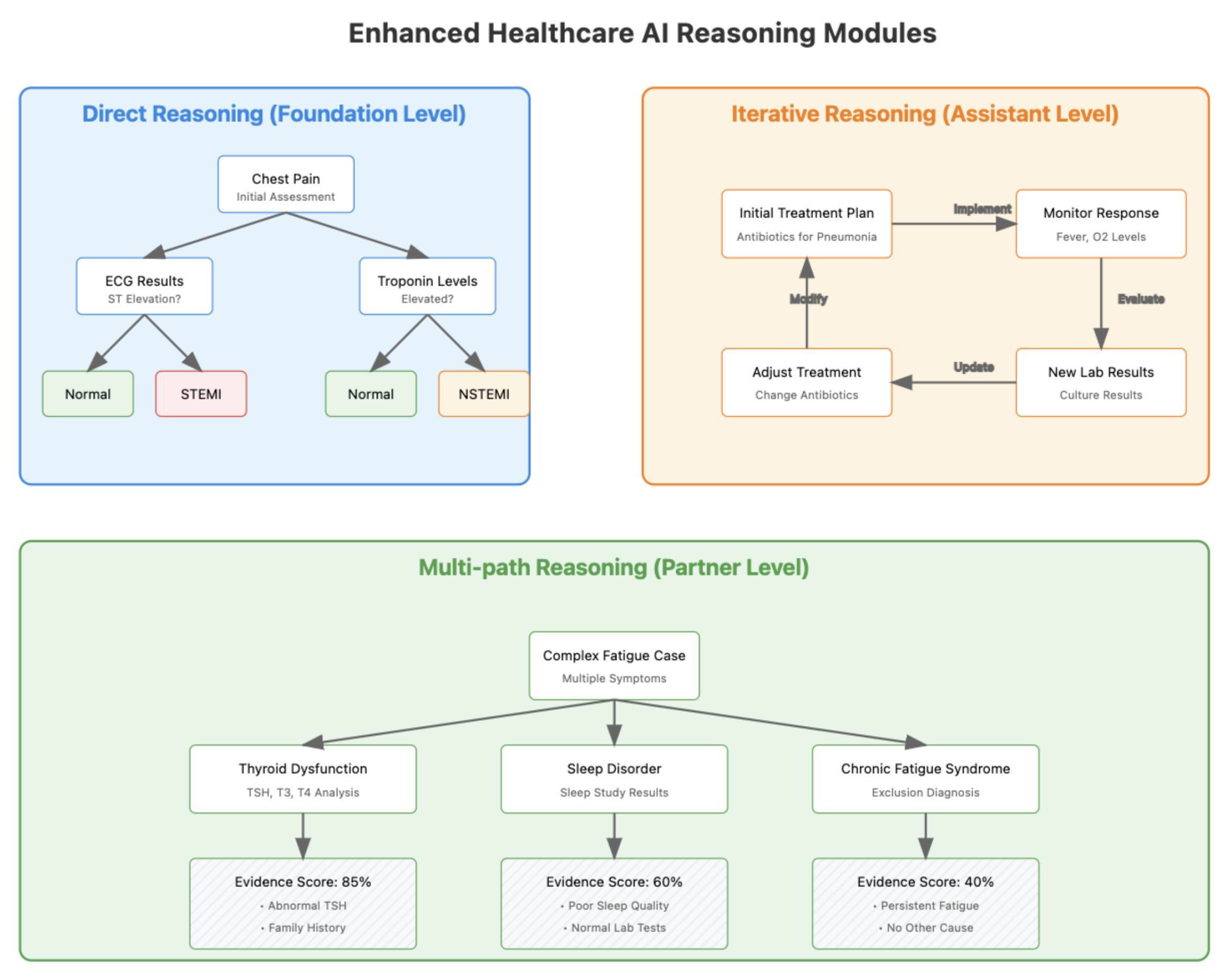

Healthcare teams continually form and test hypotheses, interpret clinical data, and revise management plans. Reasoning modules in AI agents can replicate these processes by structuring logical steps, analyzing potential treatments, and adapting decisions as new data streams in. As illustrated in

Figure 11, this progression spans from direct reasoning at the foundation level through iterative reasoning at the assistant level, to sophisticated multi-path reasoning at the partner level. An assistant-level agent might focus on routine cases, while a partner-level system handles more uncertain, multi-layered scenarios requiring iterative reevaluation [56,57].

4.6. Reasoning Modules

4.6.1. Direct Reasoning Modules

The foundation-level direct reasoning shown in

Figure 11’s first panel demonstrates how an AI agent evaluates available data to arrive at a recommendation without seeking immediate feedback[58]. Using the chest pain example, the system methodically processes ECG results and troponin levels through a clear decision tree to identify STEMI or NSTEMI conditions. This single-path reasoning approach is effective for well-defined cases with clear diagnostic criteria. Although direct reasoning streamlines processes, it also calls for careful safeguards in critical settings. Foundation-level agents might lack such complexity, while assistant-level agents typically display basic direct reasoning, and partner systems can implement multi-path logic for more advanced tasks [56].

4.6.2. Reasoning with Feedback

The

Figure 11’s second and third panels illustrate how clinical decisions become increasingly iterative and complex at higher autonomy levels. The assistant-level iterative reasoning shows a continuous feedback loop for pneumonia treatment, where initial antibiotic choices are monitored and adjusted based on patient response and culture results. At the partner level, as shown in the bottom panel, the system employs multi-path reasoning to evaluate complex fatigue cases, simultaneously considering multiple hypotheses (thyroid dysfunction, sleep disorder, chronic fatigue syndrome) with evidence scores and supporting data for each pathway. These dynamic loops enable the agent to adapt its recommendations over time, which is especially valuable for advanced care scenarios. While such capabilities can be transformative, robust governance is essential to keep them consistent with safety standards. A pioneer-level agent might even propose entirely novel treatment schedules or advanced trial designs but must still incorporate professional oversight to ensure safe translation into practice [59,60].

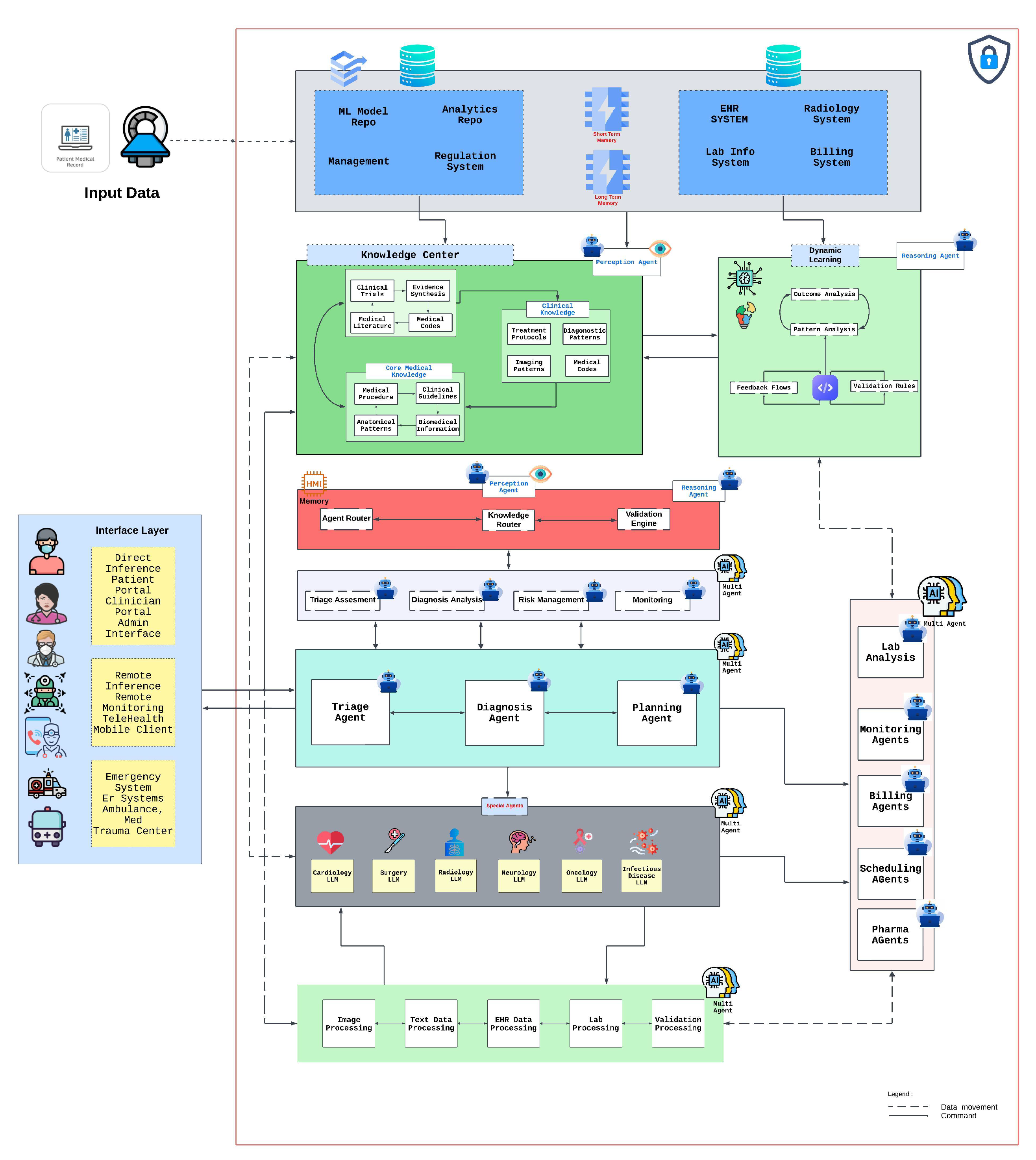

5. Integrated AI Healthcare Architecture

The evolution of AI agents in healthcare necessitates a comprehensive architectural framework that enables seamless integration while maintaining robust security protocols and clinical efficacy. Recent studies have demonstrated that successful deployment of healthcare AI systems requires careful consideration of both technical infrastructure and clinical workflows [61].

Figure 12 presents an architectural framework that illustrates the integration of various AI agents within a modern healthcare setting, expanding upon the agent categories discussed in previous sections. This architecture demonstrates the practical implementation of foundation, assistant, partner, and pioneer agents within a unified healthcare ecosystem.

5.1. System Architecture and Knowledge Integration

The proposed architecture implements a three-layer approach that facilitates the progression from basic AI capabilities to advanced clinical decision support. The infrastructure layer incorporates ML model repositories, analytics frameworks, and regulatory compliance systems, aligning with recent findings on successful healthcare AI implementations. This foundation enables secure data flow while maintaining strict regulatory compliance, particularly crucial in healthcare settings where data privacy and security are paramount [62].

The knowledge center serves as the system’s cognitive core, housing clinical knowledge bases, evidence synthesis mechanisms, and dynamic learning systems. This approach builds upon recent work demonstrating that centralized knowledge management significantly improves AI agent performance in clinical settings. By integrating clinical trials, medical literature, treatment protocols, and core medical knowledge, the system creates a comprehensive resource supporting AI agents across all autonomy levels. The knowledge center implements advanced natural language processing and semantic reasoning capabilities to maintain relationships between different knowledge domains, enabling sophisticated clinical reasoning and decision support [63].

5.2. Multi-Agent Integration and Clinical Workflow

The architecture demonstrates sophisticated integration mechanisms through a multi-tiered agent communication framework. Foundation agents operate within the basic service layer, handling discrete tasks such as data processing and initial triage. Assistant and partner agents leverage the knowledge center for more sophisticated operations, while pioneer agents utilize the full stack for complex decision-making and novel protocol development. Recent research has shown that multi-agent healthcare systems achieve optimal performance through structured communication protocols and validated decision pathways. The system implements this through a centralized agent routing mechanism that manages inter-agent communication while maintaining clinical safety and decision validation [64].

Clinical workflow integration represents a crucial aspect of the architectural framework, achieved through modular agent design that adapts to specialty-specific requirements. The architecture supports various clinical scenarios through specialized agents, including cardiology, surgery, radiology, and oncology LLMs. These domain-specific agents interact through a sophisticated routing system that enables real-time consultation and knowledge sharing. Performance analysis of similar architectures has demonstrated significant improvements in diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning when compared to traditional clinical decision support systems [64].

5.3. Implementation Framework and Validation

Implementation success depends heavily on addressing key technical and clinical requirements within the healthcare environment. Recent literature emphasizes the importance of robust security measures and scalable architecture in healthcare AI systems [65]. The architecture implements comprehensive security protocols, including end-to-end encryption, role-based access control, and detailed audit trails. Clinical validation is ensured through continuous performance monitoring and evidence-based validation frameworks that track decision quality and patient outcomes.

The system’s scalability is achieved through distributed computing capabilities and sophisticated load balancing mechanisms. Performance testing has demonstrated the architecture’s ability to handle increasing data volumes and user demands while maintaining response times within clinically acceptable thresholds. The modular design enables healthcare institutions to implement AI capabilities progressively, starting with foundation agents and gradually incorporating more sophisticated capabilities as organizational readiness evolves.

This architectural framework represents a significant advance in healthcare AI integration, demonstrating how different categories of AI agents can effectively coexist within clinical environments while maintaining necessary security, compliance, and clinical standards. As healthcare AI continues to evolve, this architecture provides a robust foundation for future developments while addressing current implementation challenges. The framework’s flexibility enables adaptation to emerging technologies and changing healthcare needs while maintaining the rigorous standards required in clinical settings.

6. Healthcare-Specific Requirements

Healthcare AI systems operate on diverse data types, including structured data (e.g., EHR entries), unstructured data (e.g., clinical notes), and imaging data (e.g., CT scans). They also engage with stakeholders who demand reliability, safety, and compliance. The adoption of foundation-level or assistant-level agents often presents fewer integration hurdles because their scope is tightly controlled, whereas advanced partner or pioneer agents require more robust data handling and thorough validation.

6.1. Data Considerations

Systems must accommodate format and exchange standards such as DICOM for imaging and HL7/FHIR for clinical data. Data privacy remains paramount, with legal frameworks like HIPAA in the U.S. and GDPR in Europe governing how patient information is stored and accessed. Ensuring data integrity through de-identification and regular validation helps maintain system reliability. Higher-autonomy agents, especially if they approach pioneer capabilities, necessitate broader and more diverse datasets to avoid biases and to handle complex, context-dependent decisions [66].

6.2. System Requirements

Real-time data processing can be crucial in critical environments like emergency care, demanding both reliability and fault tolerance. Automated alert systems for adverse events exemplify how an assistant agent might function in a fast-paced setting, continuously scanning vitals and responding with minimal latency. As an agent’s responsibilities expand, scalability becomes non-negotiable. A partner-level agent coordinating tasks across a large hospital must support increasing data volumes and user demands without compromising performance [67].

6.3. Integration Frameworks

6.3.1. Healthcare Systems

Incorporating AI agents into clinical infrastructures calls for compatibility with electronic medical records (EMR/EHR) and picture archiving and communication systems (PACS). For instance, an agent might access PACS data to refine imaging-based diagnoses, but it must also transmit its recommendations back to the EMR workflow for clinician review. Adequate security measures, including encryption and role-based access, are vital for maintaining trust in any AI system, whether it is a foundation-level tool or a partner-level solution.

6.3.2. Technical Infrastructure

AI agents often rely on -based architectures [47] for ease of scaling and data storage. Edge computing can also be adopted to minimize latency, particularly in real-time monitoring scenarios. Well-structured APIs permit seamless communication between AI agents and healthcare systems, supporting interoperability across diverse hospital platforms. These considerations matter even at the level of foundation agents but become increasingly critical as systems move toward partner or pioneer capabilities that require comprehensive data pipelines [65].

6.4. Performance Metrics

6.4.1. Technical Metrics

Performance evaluation encompasses metrics such as processing speed, accuracy, and system reliability. Diagnostic tools, for instance, are evaluated by sensitivity and specificity, where top-tier models may exceed 90% accuracy for certain diseases. Scalability testing is important to verify that the agent can manage surging user loads without significant slowdowns. As an agent scales up from foundation-level tasks to more complex roles, consistently high performance in these areas becomes integral to widespread adoption.

6.4.2. Healthcare Metrics

Clinically oriented metrics such as diagnostic precision, treatment efficacy, and user satisfaction carry significant weight. Timely responses are especially vital in areas like emergency triage, where even short delays might lead to adverse outcomes. Reliability, measured through system uptime and error rates, further indicates whether the agent can handle critical decision points without frequent breakdowns. Regardless of the autonomy level, user feedback remains essential for refining the agent’s interface, interpretability, and overall effectiveness [68].

7. Challenges and Limitations

AI agents hold considerable promise for enhancing healthcare delivery by improving patient outcomes, operational efficiency, and clinical decision support. Yet, their successful implementation faces persistent hurdles that vary with the agent’s autonomy level. At the foundation or assistant level, data availability and system interoperability often represent the biggest bottlenecks. By contrast, partner- or pioneer-level systems must also contend with heightened liability, clinical acceptance, and regulatory complexity [66].

Broadly, these obstacles can be grouped into three main categories technical, healthcare-specific, and ethical regulatory each with cross-cutting implications for robustness, evaluation, and risk management.

Section 7.1 through 7.6 examine these challenges in detail, and

Table 2 provides a consolidated view of the most critical hurdles, proposed solutions, and associated implementation concerns. Together, they underscore the need for multi-faceted strategies that balance innovation against the imperatives of safety, reliability, and ethical healthcare practice.

7.1. Robustness and Reliability Challenges

Agents depend on well-labeled, reliable data and carefully engineered workflows to achieve consistent performance. This issue is particularly acute in specialized or rare medical conditions where data can be scarce. For example, an oncology-focused AI agent may struggle with rare cancer subtypes due to insufficient training examples [69].

System integration further complicates reliability: a radiology department’s AI model may need to interoperate seamlessly with both a PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) and a main EHR platform, each with its own data formats and update cycles. Deep learning systems, though powerful, frequently require substantial computational resources, limiting feasibility in remote or edge-deployment settings. In intensive care units, where continuous monitoring is essential, any latency or misclassification can threaten patient safety; an AI agent that processes real-time vitals must simultaneously ensure low latency and high accuracy [69].

7.2. Healthcare-Specific Barriers

Where lives are at stake, reliability and safety must be demonstrably high. This is especially clear in surgical or emergency medicine contexts, where an error can produce catastrophic outcomes. Many AI agents, however, are still in early developmental stages and lack thorough real-world clinical validation. The gap is especially notable in personalized medicine, where success demands modeling of genetic, environmental, and clinical factors over time.

Even once technical performance is strong, clinical acceptance is far from guaranteed. An assistant-level solution that flags potential drug interactions is typically easier to adopt than a more autonomous, partner-level system suggesting unorthodox therapy protocols particularly if it disrupts existing workflows or raises concerns about loss of physician autonomy. Moreover, staff need training to interpret AI outputs effectively and to trust the system’s recommendations [70].

7.3. Ethical and Regulatory Challenges

Data privacy requirements such as HIPAA (in the United States) or GDPR (in Europe) are especially consequential for AI agents, which often ingest sensitive personal health information in real time. This not only affects where and how data are stored but also shapes the algorithmic design for instance, requiring homomorphic encryption or differential privacy techniques to ensure secure processing.

Bias in training data is another critical concern. If demographic or geographic groups are underrepresented in historical medical records, the resulting models may systematically under-serve those populations. Further, black-box reasoning can hamper trust if physicians cannot understand how a recommendation was generated. From a regulatory perspective, continuous-learning AI that updates its models dynamically may require new FDA or EMA approval pathways, as re-training constitutes a “moving target” that complicates standard device regulations [71].

7.4. Evaluation Protocols and Dataset Generation

Evaluations of AI agents must go beyond accuracy to include practical metrics such as clinical utility, cost-effectiveness, and user satisfaction. In fields like infectious disease, non-stationary distributions where pathogens evolve or treatment guidelines shift further complicate model validation over time. Curating large, representative datasets remains difficult due to privacy restrictions, lack of standardization, and historically fragmented hospital IT environments.

Federated learning or multi-site collaborations may help address these issues, although building consensus on data-sharing protocols remains an ongoing challenge. Rare-disease registries and synthetic data generation can be instrumental in bridging knowledge gaps, provided they meet rigorous quality standards [68].

7.5. Robustness and Reliability Concerns

Although advanced models like GPT-4 are increasingly proficient, they can still produce hallucinated facts or incorrect reasoning, particularly in response to unusual prompts or edge-case scenarios. In healthcare, a spurious dosage recommendation can have grave consequences. Multi-agent networks heighten the stakes, since errors in one subsystem (e.g., pharmacy ordering) can cascade into others (lab scheduling, medication administration, etc.).

Mitigation strategies range from ensemble verification (combining multiple model outputs) to explicit confidence scoring or fallback protocols that trigger human in the loop reviews. Despite these measures, the complexity of healthcare workflows means no single fail-safe can cover every scenario culture and training around AI use are as important as the technology itself [72].

7.6. Governance and Risk Management

As AI agents advance toward greater autonomy, governance structures must evolve to ensure accountability, safety, and ethical oversight. Hospitals increasingly implement human-in-the-loop checkpoints for high-impact decisions, like chemotherapy orders or surgical plans. Institutional review boards and ethics committees should periodically audit model updates, especially for systems that adapt to new data in real time.

Cybersecurity remains pivotal: in multi-agent frameworks, a breach in one node can rapidly propagate incorrect or malicious directives across an entire hospital network. Transparent logging, real-time monitoring, and comprehensive staff training are essential to prevent and mitigate such events. Ultimately, the integration of partner- or pioneer-level agents necessitates robust risk-mitigation strategies and ongoing collaboration among clinicians, data scientists, administrators, and regulators [73].

These technical, healthcare-specific, and ethical/regulatory challenges must be tackled in tandem to foster safe, effective AI agents. Foundation-level systems can sometimes circumvent data or integration hurdles by focusing narrowly, but higher-autonomy agents confront far more complex issues of reliability, liability, and acceptance. Their continued adoption will likely hinge on transparent governance, robust data generation strategies, and sound risk management.

The path forward includes federated data collaborations, explainable AI frameworks, and human-in-the-loop checkpoints tailored to each autonomy level. By uniting clinical stakeholders, technology experts, and regulators, the field can evolve from simple assistant-level systems toward truly pioneer-level agents that deliver transformative results without compromising patient safety or trust.

8. Future Directions

The field of AI agents in healthcare is advancing rapidly, driven by innovations in technology and evolving clinical needs. The current trajectory indicates a shift toward more integrated, efficient, and patient-centered systems. By addressing existing challenges and leveraging new opportunities, AI agents have the potential to revolutionize care delivery and operational efficiency in the coming decades.

8.1. Emerging Technologies

8.1.1. Technical Advancements

Next-generation AI agents will harness cutting-edge architectures such as transformers and generative AI models to achieve unprecedented levels of accuracy and efficiency. For example, hybrid models combining reinforcement learning and supervised learning are anticipated to excel in real-time decision-making scenarios, such as emergency care and surgical assistance. Integration innovations, including edge computing and federated learning [47], will enable AI systems to process data locally, enhancing privacy and reducing latency. Performance improvements in GPUs and TPUs will further accelerate AI training and inference capabilities [47], allowing for faster and more scalable deployments.

8.1.2. Healthcare Applications

Emerging technologies will introduce novel clinical applications, such as AI-driven molecular diagnostics, enabling precise detection of rare genetic disorders. Workflow evolution will focus on automating complex processes like multidisciplinary treatment planning, reducing clinician workload. Advances in patient care are expected through personalized medicine, powered by AI agents capable of tailoring therapies based on genetic and lifestyle data.

8.2. Research Directions

8.2.1. Technical Research

Future research will prioritize the development of more robust and interpretable algorithms. Explainable AI (XAI) models will address the black-box nature of current systems, increasing clinician trust and facilitating regulatory approval. Advances in system architecture will focus on modular, plug-and-play designs to simplify integration with existing healthcare IT systems. Research into integration methods will emphasize standardized APIs and interoperability frameworks to enhance data flow between disparate systems.

8.2.2. Healthcare Research

Clinical validation will remain a critical focus, with large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy and safety of AI interventions. Implementation studies will investigate the best practices for deploying AI agents in diverse healthcare environments, from rural clinics to urban hospitals. Outcome research will explore long-term impacts on patient health, provider efficiency, and healthcare costs.

8.3. Implementation Roadmap

8.3.1. Development Path

Short-term goals (1–2 years) include refinement of existing models for improved accuracy and reliability. Key initiatives will focus on integrating AI into high-impact areas such as radiology and pathology. Medium-term objectives (3–5 years) emphasize expanding AI applications into complex domains like personalized medicine and predictive analytics. Long-term vision (5+ years) aims to create next-generation AI agents that seamlessly integrate into all facets of healthcare.

8.3.2. Success Indicators

Success will be measured by clinical outcomes, such as reductions in diagnostic errors and treatment delays. Operational metrics, including workflow efficiency and cost savings, will also serve as critical benchmarks. User satisfaction among healthcare providers and patients will be key to assessing the real-world impact of AI agents.

9. Conclusion

This review paper has examined the current state, applications, challenges, and future directions of AI agents in healthcare. The scope covered AI agent architectures, clinical and operational applications, technical foundations, and challenges such as ethical, technical, and healthcare-specific barriers. Major findings reveal the transformative potential of AI in diagnostics, treatment planning, and workflow optimization, with critical insights into the integration complexities and the need for robust data governance.

AI agents have demonstrated advanced capabilities in automating complex tasks like medical image analysis, clinical decision-making, and administrative workflow management. Implementation success has been observed in high-impact areas such as radiology and oncology, with performance metrics indicating substantial accuracy improvements. However, technical challenges persist, including data standardization issues, integration difficulties with legacy systems, and the computational cost of deploying real-time AI agents at scale.

AI agents have positively influenced clinical outcomes by improving diagnostic accuracy and treatment personalization. For instance, predictive models have shown efficacy in early disease detection, reducing mortality rates in critical conditions such as sepsis. System efficiency has also seen notable enhancements through resource optimization and reduced administrative burden. These advancements indicate a significant transformation in healthcare practices, with AI agents creating value by enabling data-driven, patient-centered care.

The future of AI agents in healthcare holds tremendous promise yet requires careful consideration of implementation challenges and ethical implications. Success will depend on continued technological innovation, robust validation frameworks, and effective collaboration between technical and healthcare stakeholders. As the field evolves, maintaining focus on patient outcomes while addressing privacy, security, and accessibility concerns will be paramount for sustainable adoption and meaningful impact in healthcare delivery.

References

- R. Grand View, "Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-healthcare-market.

- T. Panch, H. Mattie, and L. A. Celi, "The “inconvenient truth” about AI in healthcare," npj Digital Medicine, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 77, 2019/08/16 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Davenport and R. Kalakota, "The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare," (in eng), Future Healthc J, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 94-98. [CrossRef]

- J. Bajwa, U. Munir, A. Nori, and B. Williams, "Artificial intelligence in healthcare: transforming the practice of medicine," Future healthcare journal, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. e188-e194, 2021.

- S. Cohen, "Chapter 1 - The evolution of machine learning: Past, present, and future," in Artificial Intelligence in Pathology (Second Edition), C. Chauhan and S. Cohen, Eds.: Elsevier, 2025, pp. 3-14.

- E. J. Topol, "High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence," Nature Medicine, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 44-56, 2019/01/01 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. He, S. L. Baxter, J. Xu, J. Xu, X. Zhou, and K. Zhang, "The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine," (in eng), Nat Med, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 30-36, Jan 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Patel et al., "Exploring temperature effects on large language models across various clinical tasks," medRxiv, p. 2024.07. 22.24310824, 2024.

- D. Patel et al., "Traditional Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and BERT (Large Language Model) Approaches for Predicting Hospitalizations From Nurse Triage Notes: Comparative Evaluation of Resource Management," JMIR AI, vol. 3, p. e52190, Aug 27 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Gulshan et al., "Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs," (in eng), Jama, vol. 316, no. 22, pp. 2402-2410, Dec 13 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Esteva et al., "Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks," Nature, vol. 542, no. 7639, pp. 115-118, 2017/02/01 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. C. Lipton, "The Mythos of Model Interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery," Queue, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 31–57, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Yan et al., "A roadmap to implementing machine learning in healthcare: from concept to practice," (in eng), Front Digit Health, vol. 7, p. 1462751, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Paproki, O. Salvado, and C. Fookes, "Synthetic Data for Deep Learning in Computer Vision & Medical Imaging: A Means to Reduce Data Bias," ACM Computing Surveys, 2024.

- A. Bohr and K. Memarzadeh, "The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications," in Artificial Intelligence in healthcare: Elsevier, 2020, pp. 25-60.

- B. D. Mittelstadt, P. Allo, M. Taddeo, S. Wachter, and L. Floridi, "The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate," Big Data & Society, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 2053951716679679, 2016.

- K. A. Huang, H. K. Choudhary, and P. C. Kuo, "Artificial Intelligent Agent Architecture and Clinical Decision-Making in the Healthcare Sector," Cureus, vol. 16, no. 7, p. e64115, 2024.

- D. S. Bitterman, H. J. W. L. Aerts, and R. H. Mak, "Approaching autonomy in medical artificial intelligence," The Lancet Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. e447-e449, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Martinengo et al., "Conversational agents in health care: expert interviews to inform the definition, classification, and conceptual framework," Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 25, p. e50767, 2023.

- T. Schachner, R. Keller, and F. v Wangenheim, "Artificial Intelligence-Based Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions: Systematic Literature Review," (in English), J Med Internet Res, Review vol. 22, no. 9, p. e20701, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Laitinen and O. Sahlgren, "AI systems and respect for human autonomy," Frontiers in artificial intelligence, vol. 4, p. 705164, 2021.

- E. Royal Academy of, "Towards Autonomous Systems in Healthcare - July 2023 Update," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://nepc.raeng.org.uk/media/mmfbmnp0/towards-autonomous-systems-in-healthcare_-jul-2023-update.pdf.

- A. Bin Sawad et al., "A systematic review on healthcare artificial intelligent conversational agents for chronic conditions," Sensors, vol. 22, no. 7, p. 2625, 2022.

- N. Mexico Business, "Beyond GenAI: The Rise of Autonomous AI Agents in Healthcare," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://mexicobusiness.news/health/news/beyond-genai-rise-autonomous-ai-agents-healthcare.

- J. Liu et al., "Medchain: Bridging the Gap Between LLM Agents and Clinical Practice through Interactive Sequential Benchmarking," arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.01605, 2024.

- A. Dutta and Y.-C. Hsiao, "Adaptive Reasoning and Acting in Medical Language Agents," arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.10020, 2024.

- D. Ferber et al., "Autonomous artificial intelligence agents for clinical decision making in oncology," arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.04667, 2024.

- M. Abbasian, I. Azimi, A. M. Rahmani, and R. Jain, "Conversational health agents: A personalized llm-powered agent framework," arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02374, 2023.

- D. Schouten et al., "Navigating the landscape of multimodal AI in medicine: a scoping review on technical challenges and clinical applications," arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.03782, 2024.

- M. Hewett, "The impact of perception on agent architectures," in Proceedings of the AAAI-98 Workshop on Software Tools for Developing Agents, 1998.

- B. D. Simon, K. B. Ozyoruk, D. G. Gelikman, S. A. Harmon, and B. Türkbey, "The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: a narrative review," Diagnostic and interventional radiology (Ankara, Turkey).

- F. Bousetouane, "Physical AI Agents: Integrating Cognitive Intelligence with Real-World Action," arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.08944, 2025.

- A. Al Kuwaiti et al., "A review of the role of artificial intelligence in healthcare," Journal of personalized medicine, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 951, 2023.

- M. Grüning et al., "The Influence of Artificial Intelligence Autonomy on Physicians Work Outcomes in Healthcare: A Lab-in-the-Field Experiment," 2025.

- D. Restrepo, C. Wu, C. Vásquez-Venegas, L. F. Nakayama, L. A. Celi, and D. M. López, "DF-DM: A foundational process model for multimodal data fusion in the artificial intelligence era," Research Square, 2024.

- P. Festor, I. Habli, Y. Jia, A. Gordon, A. A. Faisal, and M. Komorowski, "Levels of autonomy and safety assurance for AI-Based clinical decision systems," in Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security. SAFECOMP 2021 Workshops: DECSoS, MAPSOD, DepDevOps, USDAI, and WAISE, York, UK, September 7, 2021, Proceedings 40, 2021: Springer, pp. 291-296.

- J. N. Acosta, G. J. Falcone, P. Rajpurkar, and E. J. Topol, "Multimodal biomedical AI," Nature Medicine, vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 1773-1784, 2022.

- K. Singhal et al., "Large language models encode clinical knowledge," arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.13138, 2022.

- L. Wang et al., "A survey on large language model based autonomous agents," Frontiers of Computer Science, vol. 18, no. 6, p. 186345, 2024.

- G. Team et al., "Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models," p. arXiv:2312.11805. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, F. Bianchi, M. Yuksekgonul, T. J. Montine, and J. Zou, "A visual–language foundation model for pathology image analysis using medical twitter," Nature medicine, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 2307-2316, 2023.

- L. Ouyang et al., "Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback," Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 35, pp. 27730-27744, 2022.

- T. B. Brown et al., "Language Models are Few-Shot Learners," p. arXiv:2005.14165. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., "Building cooperative embodied agents modularly with large language models," arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.02485, 2023.

- Z. Yang, S. S. Z. Yang, S. S. Raman, A. Shah, and S. Tellex, "Plug in the safety chip: Enforcing constraints for llm-driven robot agents," in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2024: IEEE, pp. 14435-14442.

- T. Guo et al., "Large language model based multi-agents: A survey of progress and challenges," arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01680, 2024.

- D. Patel et al., "Cloud Platforms for Developing Generative AI Solutions: A Scoping Review of Tools and Services," arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.06044, 2024.

- Y. Qin et al., "Toolllm: Facilitating large language models to master 16000+ real-world apis," arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.16789, 2023.

- T. Schick et al., "Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, pp. 68539-68551, 2023.

- Y. Song et al., "RestGPT: Connecting Large Language Models with Real-World RESTful APIs," arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.06624, 2023.

- A. M. Bran, S. Cox, O. Schilter, C. Baldassari, A. D. White, and P. Schwaller, "ChemCrow: Augmenting large-language models with chemistry tools," arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.05376, 2023.

- R. Nakano et al., "WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback," p. arXiv:2112.09332. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhong, L. W. Zhong, L. Guo, Q. Gao, H. Ye, and Y. Wang, "Memorybank: Enhancing large language models with long-term memory," in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, vol. 38, no. 17, pp. 19724-19731.

- C. Hu, J. Fu, C. Du, S. Luo, J. Zhao, and H. Zhao, "Chatdb: Augmenting llms with databases as their symbolic memory," arXiv preprint, 2023. arXiv:2306.03901.

- A. Madaan et al., "Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, 2024.

- T. Kojima, S. S. Gu, M. Reid, Y. Matsuo, and Y. Iwasawa, "Large language models are zero-shot reasoners," Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 35, pp. 22199-22213, 2022.

- S. Yao et al., "Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 36, 2024.

- D. Patel et al., "Evaluating prompt engineering on GPT-3.5’s performance in USMLE-style medical calculations and clinical scenarios generated by GPT-4," Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 17341, 2024.

- X. Wang et al., "Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models," arXiv preprint, 2022. arXiv:2203.11171.

- S. Yao et al., "React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models," arXiv preprint, 2022. arXiv:2210.03629.

- J. Yang et al., "Harnessing the power of llms in practice: A survey on chatgpt and beyond," ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 1-32, 2024.

- Y. Liang et al., "Taskmatrix. ai: Completing tasks by connecting foundation models with millions of apis," Intelligent Computing, vol. 3, p. 0063, 2024.

- Y. Qin et al., "Tool learning with foundation models," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 1-40, 2024.

- C. Zhang et al., "ProAgent: building proactive cooperative agents with large language models," in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, vol. 38, no. 16, pp. 17591-17599.

- E. Karpas et al., "MRKL Systems: A modular, neuro-symbolic architecture that combines large language models, external knowledge sources and discrete reasoning," arXiv preprint, 2022. arXiv:2205.00445,.

- Y. Wang et al., "Aligning Large Language Models with Human: A Survey," p. arXiv:2307.12966. [CrossRef]

- J. Ruan et al., "TPTU: Large Language Model-based AI Agents for Task Planning and Tool Usage. arXiv 2308.03427 (2023)," ed, 2023.

- D. Banerjee, P. Singh, A. Avadhanam, and S. Srivastava, "Benchmarking LLM powered Chatbots: Methods and Metrics," p. arXiv:2308.04624. [CrossRef]

- G. Mialon et al., "Augmented Language Models: a Survey," p. arXiv:2302.07842. [CrossRef]

- M. Lee et al., "Evaluating Human-Language Model Interaction," p. arXiv:2212.09746. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Chang and B. K. Bergen, "Language Model Behavior: A Comprehensive Survey," Computational Linguistics, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 293-350, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ji et al., "Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation," ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 55, no. 12, p. Article 248, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Kojs, "A Survey of Serverless Machine Learning Model Inference," p. arXiv:2311.13587. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).