Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction: OCT in Home and Intraoperative Settings

II. Home OCT

A. Home OCT for Early Detection

Type of Home OCT Used, Resolution, and Image Quality

|

| Device Name | FDA Approved | Commercialized | System Type | Purpose | Biggest Publication |

| ForeseeHome OCT by Notal Vision | Yes | Yes | Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry (PHP) | To detect Wet AMD earlier notified physician | Chew EY et al. 2014 [56] |

| Scanly by Notal Vision | Yes | No | SD OCT with AI integrated with Notal OCT Analyzer (NOA) an AI analyzer | Self-operated tele-connected device for daily imaging between office visits | Mathai et al. 2022 [46] . |

| Sparse OCT | No | No | Compressed sensing (CS) in spectral domain optical coherence tomography [54] | Elderly and cost friendly self OCT | Maloca et al. 2018 |

| SELFF OCT | No | No | off-axis, full-field, time-domain OCT | Reduce device complexity and cost | Burchard et al. 2022 |

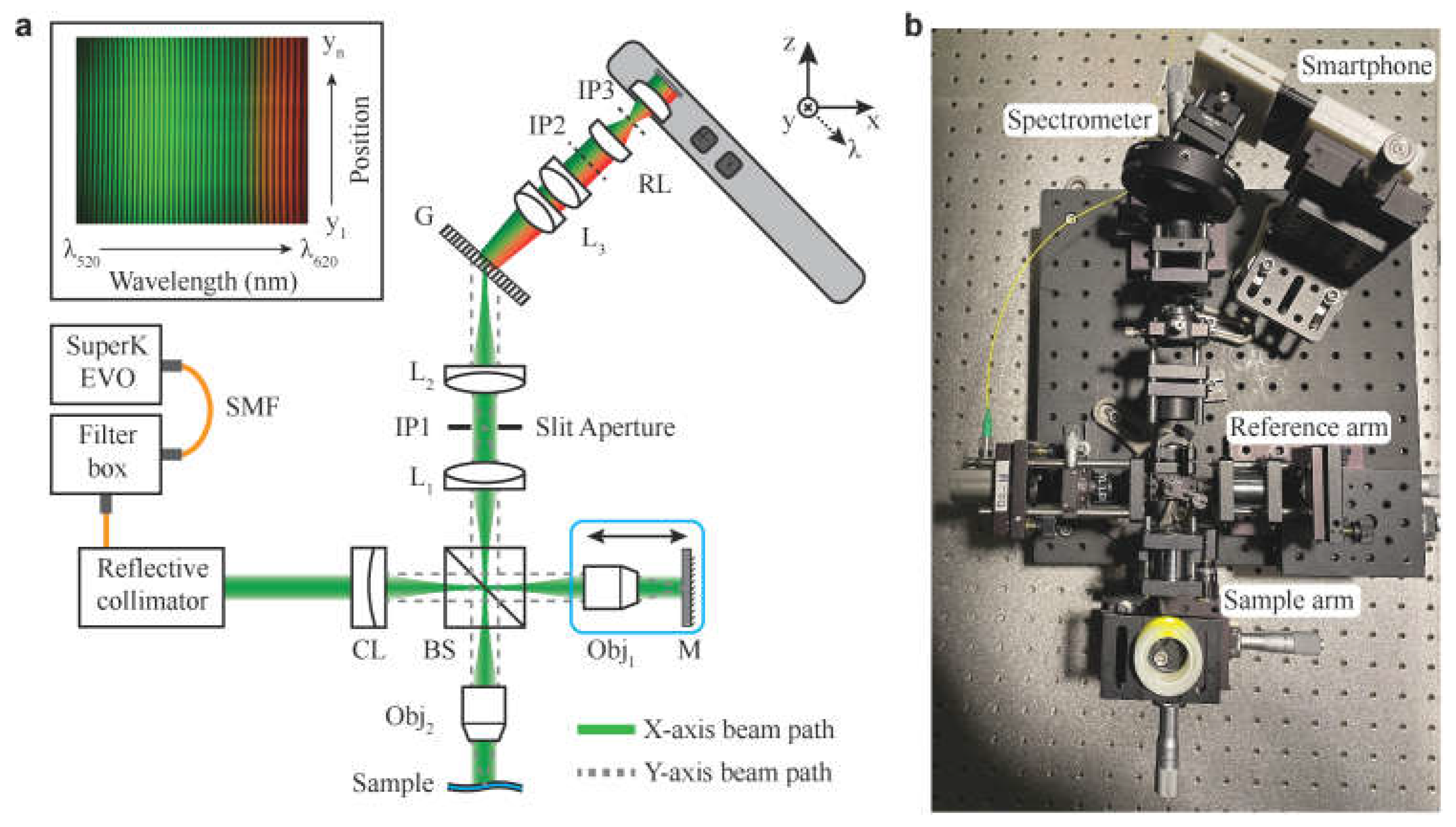

| SmartOCT | No | No | line-field OCT (LF-OCT) [55] | Real time OCT imaging integrated to smartphone | Malone JD, Hussain et al. |

B. Home OCT of Fluid Monitoring Changes

Device Variations for Fluid Monitoring

Portable OCT Advancement

Impact on Treatment Paradigms and Clinical Implications

Regulatory, Compliance and Responsibility

Medicolegal Aspect

Pitfalls and Challenges

III. Intraoperative OCT in Vitreoretinal Surgery

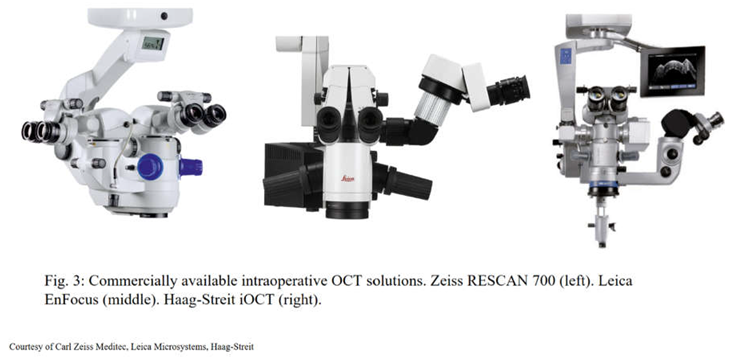

A. Instrumentation and Background

|

B. Anterior Segment OCT Use in the OR

C. Posterior Segment OCT Use

D. Challenges

Does Intraoperative OCT Change Decision-Making?

IV. Conclusion and Future Directions

References

- Huang, D.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Stinson, W.G.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography HHS Public Access. 1991, 254, 1178–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, J.; Swanson, E. The development, commercialization, and impact of optical coherence tomography. 2016, 57, OCT1–OCT13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, J.G.; Brezinski, M.E.; Tearney, G.J.; Boppart, S.A.; Bouma, B.; et al. Optical biopsy and imaging using optical coherence tomography. 1995, 1, 970–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, M.L.; Wollstein, G.; Ishikawa, H.; Kagemann, L.; Xu, J.; et al. Optical coherence tomography: History, current status, and laboratory work. 2011, 52, 2425–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, M.; Duker, J.S. Optical coherence tomography-current and future applications. 2013, 24, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Khanna, A.; Palmer, E.; Wilde, C.; Zaman, A.; et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography: a review of the current literature. 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsaid, B.; Baumann, B.; Huang, D.; Barry, S.; Cable, A.E.; et al. Ultrahigh speed 1050nm swept source / Fourier domain OCT retinal and anterior segment imaging at 100,000 to 400,000 axial scans per second. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, C.G.; Witkin, A.J.; Ko, T.H.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Chan, A.; et al. Ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography in non-exudative age related macular degeneration. 2006, 90, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehoshua, Z.; Wang, F.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Penha, F.M.; Feuer, W.J.; et al. Natural history of drusen morphology in age-related macular degeneration using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. 2011, 118, 2434–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F. Age-related choroidal atrophy. 2009, 147, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, R.; Wagner, S.K.; Keane, P.A. Optical coherence tomography in the 2020s—outside the eye clinic. 2021, 35, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Holekamp, N.M.; Heier, J.S. Prospective, Longitudinal Study: Daily Self-Imaging with Home OCT for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2022, 6, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolar-Szczasny, J.; Drab, A.; Rejdak, R. Home-monitoring/remote optical coherence tomography in teleophthalmology in patients with eye disorders-a systematic review. 2024, 11, 1442758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, B.E.; Klein, R. Cataracts and macular degeneration in older Americans. 1982, 100, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.; Linton, K.L. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. 1992, 99, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congdon, N.; O'Colmain, B.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Klein, R.; Muñoz, B.; et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. 2004, 122, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascolini, D.; Mariotti, S.P.; Pokharel, G.P.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Etya'ale, D.; et al. 2002 global update of available data on visual impairment: a compilation of population-based prevalence studies. 2004, 11, 67–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Kawasaki, R.; Yanagi, Y. Early Stages of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Racial/Ethnic Differences and Proposal of a New Classification Incorporating Emerging Concept of Choroidal Pathology. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, F.L.; Wilkinson, C.P.; Bird, A.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.; et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. 2013, 120, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambati, J.; Fowler, B.J. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. 2012, 75, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.C. Therapeutic targets in age-related macular disease. 2010, 120, 3033–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Harrington, M.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; et al. Effectiveness Of Different Monitoring Modalities In The Detection Of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The Home Study, Report Number 3. 2016, 36, 1542–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AMSLER, M. Earliest symptoms of diseases of the macula. 1953, 37, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino, R.; Kynn, M.G. Macular function surveillance revisited. 2008, 79, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchard, R.A. Validity and interpretation of Amsler grid reports. 1993, 111, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.L.; Ferris, F.L.; Armstrong, J.; Hwang, T.S.; Chew, E.Y.; et al. Retinal precursors and the development of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. 2008, 115, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichi, F.; Abboud, E.B.; Ghazi, N.G.; Khan, A.O. Fundus autofluorescence imaging in hereditary retinal diseases. 2018, 96, e549–e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Mallus, M.T.; Imola, F.; Albertucci, M. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT). 2013, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, A.; Nivison-Smith, L.; Assaad, N.; Kalloniatis, M. Infrared reflectance imaging in age-related macular degeneration. 2016, 36, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, N.; Colijn, J.M.; Kifley, A.; Lee, K.E.; Buitendijk, G.H.S.; et al. Five-year progression of unilateral age-related macular degeneration to bilateral involvement: the Three Continent AMD Consortium report. 2017, 101, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.S.; Mitchell, P.; Seddon, J.M.; Holz, F.G.; Wong, T.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. 2012, 379, 1728–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study design and baseline patient characteristics. ETDRS report number 7. 1991, 98, 741–756. [CrossRef]

- Lad, E.M.; Finger, R.P.; Guymer, R. Biomarkers for the Progression of Intermediate Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2023, 12, 2917–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, A.; Wong, T.Y.; Ting, D.S.W.; Govindaiah, A.; Souied, E.H.; et al. Artificial Intelligence to Stratify Severity of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) and Predict Risk of Progression to Late AMD. 2020, 9, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, E.R.; Jeong, H.K.; Katz, E.A.; Toth, C.A.; Wang, D.; et al. A Deep-Learning Algorithm to Predict Short-Term Progression to Geographic Atrophy on Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. 2023, 141, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Sun, J.; Kawasaki, R.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Gupta, N.; et al. Guidelines on Diabetic Eye Care: The International Council of Ophthalmology Recommendations for Screening, Follow-up, Referral, and Treatment Based on Resource Settings. 2018, 125, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydinger, C.D.; Ferreira, L.B.; Williams, K.A.; Smith, J.R. Mechanisms of macular edema. 2023, 10, 1128811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.B.; Silva, P.S.; Cavallerano, J.D.; Aiello, L.P. Clinical Components of Telemedicine Programs for Diabetic Retinopathy. 2016, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.B.; Silva, P.S.; Cavallerano, J.D.; Aiello, L.P. Operational Components of Telemedicine Programs for Diabetic Retinopathy. 2016, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxel, C.J.; Adelman, R.A.; Bailey, S.T.; Fawzi, A.; Lim, J.I.; et al. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern®. 2020, 127, P66–P145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Terheyden, J.H.; Welchowski, T.; Schmid, M.; Letow, J.; et al. Prevalence of Retinal Vein Occlusion in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2019, 241, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayreh, S.S.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Podhajsky, P. Incidence of various types of retinal vein occlusion and their recurrence and demographic characteristics. 1994, 117, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Gerendas, B.S.; Midena, E.; Sivaprasad, S.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Retinal Vein Occlusion by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). 2019, 242, 123–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Chong, V.; Loewenstein, A.; Larsen, M.; Souied, E.; et al. Guidelines for the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). 2014, 98, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ForeseeHome® | Notal Vision.

- Mathai, M.; Reddy, S.; Elman, M.J.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Ladd, B.; et al. Analysis of the Long-term Visual Outcomes of ForeseeHome Remote Telemonitoring: The ALOFT Study. 2022, 6, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, A.; Ferencz, J.R.; Lang, Y.; Yeshurun, I.; Pollack, A.; et al. Toward earlier detection of choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration: multicenter evaluation of a preferential hyperacuity perimeter designed as a home device. 2010, 30, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, A.-H.S.R.; Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; et al. Randomized trial of a home monitoring system for early detection of choroidal neovascularization home monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study. 2014, 121, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahen, K.; Benyamini, G.; Loewenstein, A. Evaluation of a Self-Imaging SD-OCT System for Remote Monitoring of Patients with Neovascular Age Related Macular Degeneration. 2020, 237, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.D.L.; Goldstein, M.; Goldenberg, D.; Zur, D.; Shulman, S.; et al. Prospective, Longitudinal Pilot Study: Daily Self-Imaging with Patient-Operated Home OCT in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2021, 1, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloca, P.; Hasler, P.W.; Barthelmes, D.; Arnold, P.; Matthias, M.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of a Novel Sparse Optical Coherence Tomography Device for Patient-Delivered Retina Home Monitoring. 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Burchard, C.; Sudkamp, H.; Tode, J.; Ehlken, C.; Purtskhvanidze, K.; et al. Self-Examination Low-Cost Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (SELFF-OCT) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a cross-sectional diagnostic accuracy study. 2022, 12, e055082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshausen, B.A.; Field, D.J. Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural images. 1996, 381, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Kang, J.U. Sparse OCT: Optimizing compressed sensing in spectral domain optical coherence tomography. 2011, 7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.D.; Hussain, I.; Bowden, A.K. SmartOCT: smartphone-integrated optical coherence tomography. 2023, 14, 3138–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; Danis, R.P.; et al. Randomized trial of the ForeseeHome monitoring device for early detection of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. The HOme Monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study design - HOME Study report number 1. 2014, 37, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, K.T.; Seal, J.; Green, M.; Winskill, C.; Attar, M. Effect of Anti-VEGF Therapy on the Disease Progression of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review and Model-Based Meta-Analysis. 2022, 62, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, S.J.; Thorne, J.E.; Ho, A.C.; Ehlers, J.P.; Schoenberger, S.D.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapies for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2019, 126, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykoff, C.C.; Clark, W.L.; Nielsen, J.S.; Brill, J.V.; Greene, L.S.; et al. Optimizing Anti-VEGF Treatment Outcomes for Patients with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2018, 24, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almony, A.; Keyloun, K.R.; Shah-Manek, B.; Multani, J.K.; McGuiness, C.B.; et al. Clinical and economic burden of neovascular age-related macular degeneration by disease status: a US claims-based analysis. 2021, 27, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, N.M.; De Beus, A.M.; Clark, W.L.; Heier, J.S. Prospective Trial Of Home Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided Management Of Treatment Experienced Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients. 2024, 44, 1714–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCANLY® Home OCT | Notal Vision.

- NASA TechPort - Project.

- Seong, D.; Han, S.; Kang, D.; Najnin, T.; Saleah, S.A.; et al. Development of Single-Board Computer-Based Temperature-Insensitive Compact Optical Coherence Tomography for Versatile Applications. 2024, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, E.A.; Agneter, A.; Schmoll, T.; Leitgeb, R.A.; Drexler, W. Miniaturizing optical coherence tomography. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Huang, K.; Luo, Z.; Ma, K.; Wang, G.; et al. Portable boom-type ultrahigh-resolution OCT with an integrated imaging probe for supine position retinal imaging. 2022, 13, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Hirano, T.; Chiku, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Miyasaka, H.; et al. Reproducibility of Portable OCT and Comparison with Conventional OCT. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grulkowski, I.; Liu, J.J.; Potsaid, B.; Jayaraman, V.; Lu, C.D.; et al. Retinal, anterior segment and full eye imaging using ultrahigh speed swept source OCT with vertical-cavity surface emitting lasers. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamari, R.N.; Keenan, J.D.; Fletcher, D.A.; Margolis, T.P. A mobile phone-based retinal camera for portable wide field imaging. 2014, 98, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-S.; Bai, C.-H.; Cheng, C.-K. Strict Pro Re Nata Versus Treat-And-Extend Regimens In Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. 2023, 43, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.E.; Lalwani, G.A.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Dubovy, S.R.; Michels, S.; et al. An optical coherence tomography-guided, variable dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. 2007, 143, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Liu, Y.; Holekamp, N.M.; Ali, M.H.; Astafurov, K.; et al. Clinical Use of Home OCT Data to Manage Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. 2024, 24741264241302858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DE Novo CLASSIFICATION REQUEST FOR.

- Hassan, J.; Shehzad, D.; Habib, U.; Aftab, M.U.; Ahmad, M.; et al. The Rise of Cloud Computing: Data Protection, Privacy, and Open Research Challenges-A Systematic Literature Review (SLR). 2022, 2022, 8303504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Tomkins-Netzer, O.; Elman, M.J.; Lally, D.R.; Goldstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of a self-imaging SD-OCT system designed for remote home monitoring. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.J.; Kiernan, D.F.; Eichenbaum, D.; Sheth, V.S.; Wykoff, C.C. Home Monitoring of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Utility of the ForeseeHome Device for Detection of Neovascularization. 2021, 5, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.A.; Ple-Plakon, P.; Blachley, T.; Musch, D.C.; Newman-Casey, P.A.; et al. Eye care providers' attitudes towards tele-ophthalmology. 2015, 21, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajra, R.; Srinivasan, M.; Torres, E.C.; Rydel, T.; Schillinger, E. Training future clinicians in telehealth competencies: outcomes of a telehealth curriculum and teleOSCEs at an academic medical center. 2023, 10, 1222181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rebah, H.; Ben Sta, H. Cloud Computing: Potential Risks and Security Approaches. 2018, 208, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, D.; Luna Marti, X.; Feuerstein-Simon, R.; Merchant, R.M.; Asch, D.A.; et al. Health Policy and Privacy Challenges Associated With Digital Technology. 2020, 3, e208285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Security Architectures for Cloud Computing.

- Mansberger, S.L.; Sheppler, C.; Barker, G.; Gardiner, S.K.; Demirel, S.; et al. Long-term Comparative Effectiveness of Telemedicine in Providing Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Examinations: A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2015, 133, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasongko, M.B.; Indrayanti, S.R.; Wardhana, F.S.; Widhasari, I.A.; Widyaputri, F.; et al. Low utility of diabetic eye care services and perceived barriers to optimal diabetic retinopathy management in Indonesian adults with vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy. 2021, 171, 108540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, Y.D.; Adriono, G.A.; Ratmilia, R.; Magdalena, C.; Sitompul, R. Knowledge, attitude, and practice pattern towards diabetic retinopathy screening among general practitioners in primary health centres in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. 2023, 24, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Lieng, M.K.; Alber, S.; Mehta, N.; Emami-Naeini, P.; et al. Trends in Remote Retinal Imaging Utilization and Payments in the United States. 2022, 129, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Kennedy, C.; Banister, K.; Goulao, B.; Cook, J.; et al. Early detection of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: an economic evaluation based on data from the EDNA study. 2022, 106, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ForeseeHome.

- Ecsedy, M.; Szamosi, A.; Karko´, C.; Zubovics, L.; Varsa´nyi, B.; et al. A Comparison of Macular Structure Imaged by Optical Coherence Tomography in Preterm and Full-Term Children. 2007, 48, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarmoutsos, F.; Sandhu, S.S.; Voros, G.M.; Shafiq, A. The Use Of Optical Coherence Tomography in the Management of Cystoid Macular Edema in Pediatric Uveitis. 2006, 10, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.K. Optical Coherence Tomography in the Management of Acute Retinopathy of Prematurity. 2006, 141, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography: past, present, and future. 2016, 30, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Traditional 510(k) Envisu SDOIS.

- Defining the OCT Revolution.

- Ehlers, J.P.; Dupps, W.J.; Kaiser, P.K.; Goshe, J.; Singh, R.P.; et al. The Prospective Intraoperative and Perioperative Ophthalmic ImagiNg With Optical CoherEncE TomogRaphy (PIONEER) Study: 2-Year Results. 2014, 158, 999–1007.e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Kaiser, P.K.; Srivastava, S.K. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography using the RESCAN 700: preliminary results from the DISCOVER study. 2014, 98, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Srivastava, S.K.; Feiler, D.; Noonan, A.I.; Rollins, A.M.; et al. Integrative Advances for OCT-Guided Ophthalmic Surgery and Intraoperative OCT: Microscope Integration, Surgical Instrumentation, and Heads-Up Display Surgeon Feedback. 2014, 9, e105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZEISS OPMI LUMERA 700 Seeing to succeed.

- Dornelles;. "With the Proveo 8 I am less distracted during surgery. The FusionOptics technology provides me a greater depth of field, and I don't have to refocus the microscope so frequently".

- iOCT Discover a new dimension with intraoperative OCT.

- Ehlers, J.P.; Goshe, J.; Dupps, W.J.; Kaiser, P.K.; Singh, R.P.; et al. Determination of feasibility and utility of microscope-integrated optical coherence tomography during ophthalmic surgery: the DISCOVER Study RESCAN Results. 2015, 133, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Modi, Y.S.; Pecen, P.E.; Goshe, J.; Dupps, W.J.; et al. The DISCOVER Study 3-Year Results. 2018, 125, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.W.; Ehlers, J.P.; Sharma, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography–Assisted Chorioretinal Biopsy in the DISCOVER Study. 2017, 37, 2183–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Uchida, A.; Srivastava, S.K. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography-compatible surgical instruments for real-time image-guided ophthalmic surgery. 2017, 101, 1306–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.D.; Waheed, N.K.; Witkin, A.; Baumal, C.R.; Liu, J.J.; et al. Microscope-Integrated Intraoperative Ultrahigh-Speed Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography for Widefield Retinal and Anterior Segment Imaging. 2018, 49, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabr, H.; Chen, X.; Zevallos-Carrasco, O.M.; Viehland, C.; Dandrige, A.; et al. Visualization From Intraoperative Swept-Source Microscope-Integrated Optical Coherence Tomography In Vitrectomy For Complications Of Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. 2018, 38, S110–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.S.; Carrasco-Zevallos, O.M.; Gunther, R.; Izatt, J.A.; Toth, C.A.; et al. Intra-operative microscope-integrated swept-source optical coherence tomography guided placement of Argus <scp>II</scp> retinal prosthesis. 2017, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, C.; Carrasco-Zevallos, O.; Keller, B.; Shen, L.; Viehland, C.; et al. Surgically integrated swept source optical coherence tomography (SSOCT) to guide vitreoretinal (VR) surgery. 2015, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, M.; Barca, F. Intraocular Optical Coherence Tomography. 2014, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Gehlbach, P.L.; Kang, J.U. Active tremor cancellation by a “Smart” handheld vitreoretinal microsurgical tool using swept source optical coherence tomography. 2012, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-P.; Wierwille, J.; Moreira, T.; Schwartzbauer, G.; Jafri, M.S.; et al. A forward-imaging needle-type OCT probe for image guided stereotactic procedures. 2011, 19, 26283–26294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenerel, N.M.; Kucumen, R.B.; Gorgun, E. The complementary benefit of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in penetrating keratoplasty. 2013, 7, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, M.; Kronschläger, M.; Ruiss, M.; Findl, O. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography guided corneal sweeping for removal of remnant Interface fluid during ultra-thin Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steverink, J.G.; Wisse, R.P.L. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography in descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty: pilot experiences. 2017, 37, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijzer, M.B.; Schellekens, P.A.W.J.; Beckers, H.J.M.; de Boer, J.H.; Imhof, S.M.; et al. Clinical applications for intraoperative optical coherence tomography: a systematic review. 2022, 36, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebelmann, S.; Horstmann, J.; Scholz, P.; Bachmann, B.; Matthaei, M.; et al. Intraoperative changes in corneal structure during excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) assessed by intraoperative optical coherence tomography. 2018, 256, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozawa, M.; Takamura, Y.; Miyake, S.; Yokota, S.; Sakashita, M.; et al. Prospective observational study of conjunctival scarring after phacoemulsification. 2016, 94, e541–e549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banayan, N.; Georgeon, C.; Grieve, K.; Borderie, V.M. Spectral-domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. A Case-Control Study. 2018, 190, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijzer, M.B.; Soeters, N.; Godefrooij, D.A.; van Luijk, C.M.; Wisse, R.P.L. Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography-Assisted Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Toward More Efficient, Safer Surgery. 2020, 39, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Singhal, D.; Maharana, P.K.; Jain, R.; Sahay, P.; et al. Continuous intraoperative optical coherence tomography-guided shield ulcer debridement with tuck in multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation. 2018, 66, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titiyal, J.S.; Kaur, M.; Falera, R. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography in anterior segment surgeries. 2017, 65, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanker, D.V.; Blumenkranz, M.S.; Andersen, D.; Wiltberger, M.; Marcellino, G.; et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery with integrated optical coherence tomography. 2010, 2, 58ra85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.M.P.C.; Torres, P.F.A.A.S.; Marinho, A.A.P. Update on Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery: A Review. 2024, 18, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titiyal, J.S. Imaging in cataract surgery. 2024, 72, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoramnia, R.; Auffarth, G.; Łabuz, G.; Pettit, G.; Suryakumar, R. Refractive Outcomes after Cataract Surgery. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, J.T.-C.; Betzler, B.K.; Lim, S.Y.; Ang, B.C.H. Anterior segment imaging in minimally invasive glaucoma surgery - A systematic review. 2022, 100, e617–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudsieh, B.; Fernández-Vigo, J.I.; Canut Jordana, M.I.; Vila-Arteaga, J.; Urcola, J.A.; et al. Updates on the utility of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the assessment of filtration blebs after glaucoma surgery. 2022, 100, e29–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.I.; Lim, S.A.; Park, H.-Y.L.; Park, C.K. Visualization of Blebs Using Anterior-Segment Optical Coherence Tomography after Glaucoma Drainage Implant Surgery. 2013, 120, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.K.; Roney, M.; Choudhary, A.; Batterbury, M.; Vallabh, N.A. Visualization of Scleral Flap Patency in Glaucoma Filtering Blebs Using OCT. 2025, 5, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua, R.; Fasanella, V.; Agnifili, L.; Curcio, C.; Ciancaglini, M.; et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography imaging of conjunctival filtering blebs after glaucoma surgery. 2014, 2014, 610623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoti, P.A.; Panarelli, J. 30 February 2021.

- Kaur, S.; Bradfield, Y.; AS, V.; Gupta, K.; Gupta, P.; et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) in strabismus following trauma. 2024, 28, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Varshney, A.; Ramappa, M.; Basu, S.; Romano, V.; et al. Role of AS-OCT in Managing Corneal Disorders. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naujokaitis, T.; Auffarth, G.U.; Łabuz, G.; Kessler, L.J.; Khoramnia, R. Diagnostic Techniques to Increase the Safety of Phakic Intraocular Lenses. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urkude, J.; Titiyal, J.S.; Sharma, N. Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided Management of Cap-Lenticule Adhesion During SMILE. 2017, 33, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iovieno, A.; Sharma, D.P.; Wilkins, M.R. OCT visualization of corneal structural changes in traumatic dislocation of LASIK flap. 2012, 32, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaini, A.R.; Abdul Fattah, M.; El-Oud, S.M.; Awwad, S.T. Automated Detection and Classification of Corneal Haze Using Optical Coherence Tomography in Patients With Keratoconus After Cross-Linking. 2018, 37, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi, F.; Lu, N.-J.; Assaf, J.F.; Hafezi, N.L.; Koppen, C.; et al. Demarcation Line Depth in Epithelium-Off Corneal Cross-Linking Performed at the Slit Lamp. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.T.; Galvin, J.; Tran, T. Epiretinal membrane: A review. 2021, 49, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P. Analysis of Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Optic Pit–Related Maculopathy With Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography. 2011, 129, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; McNutt, S.; Dar, S.; Tao, Y.K.; Srivastava, S.K. Visualisation of contrast-enhanced intraoperative optical coherence tomography with indocyanine green. 2014, 98, 1588–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Xie, H.; Luo, D.; Zhang, J. Intravitreal indocyanine green is toxic to the retinal cells. 2024, 736, 150872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, F.; Yasui, O.; Hirose, H.; Ohba, N. Optic nerve atrophy after vitrectomy with indocyanine green-assisted internal limiting membrane peeling in diffuse diabetic macular edema. 2004, 242, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandorfer, A.; Haritoglou, C.; Kampik, A. Toxicity of indocyanine green in vitreoretinal surgery. 2008, 42, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkner-Radler, C.I.; Glittenberg, C.; Gabriel, M.; Binder, S. Intrasurgical Microscope-Integrated Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography–Assisted Membrane Peeling. 2015, 35, 2100–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leisser, C.; Hackl, C.; Hirnschall, N.; Luft, N.; Döller, B.; et al. Visualizing Macular Structures During Membrane Peeling Surgery With an Intraoperative Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Device. 2016, 47, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikbova, G.; Oshitari, T.; Baba, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Mori, K. Pathogenesis and Management of Macular Hole: Review of Current Advances. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudric, A.; Haouchine, B.; Massin, P.; Paques, M.; Blain, P.; et al. Macular hole formation: new data provided by optical coherence tomography. 1999, 117, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Kadir, M.-A.; Lim, L.T. Update on surgical management of complex macular holes: a review. 2021, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Xu, D.; Kaiser, P.K.; Singh, R.P.; Srivastava, S.K. Intrasurgical dynamics of macular hole surgery: an assessment of surgery-induced ultrastructural alterations with intraoperative optical coherence tomography. 2014, 34, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Uchida, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Hu, M. Predictive Model for Macular Hole Closure Speed: Insights From Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography. 2019, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Yadav, B. HOLE-DOOR SIGN: A Novel Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography Feature Predicting Macular Hole Closure. 2018, 38, 2045–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, M.; Micelli Ferrari, L.; Cicinelli, Maria V.; Nikolopoulou, E.; Zito, R.; et al. Feasibility and Safety of Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided Short-Term Posturing Prescription after Macular Hole Surgery. 2020, 63, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.; Zheng, Y.; Lee, T.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H.; Fekrat, S. Macular Hole in One Eye Predicts Progression of Vitreomacular Traction to Macular Hole in Fellow Eye. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2023, 64, 5260–5260. [Google Scholar]

- Morescalchi, F.; Russo, A.; Semeraro, F. Surgical Outcomes Of Vitreomacular Traction Treated With Foveal-Sparing Peeling Of The Internal Limiting Membrane. RETINA 2021, 41, 2026–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

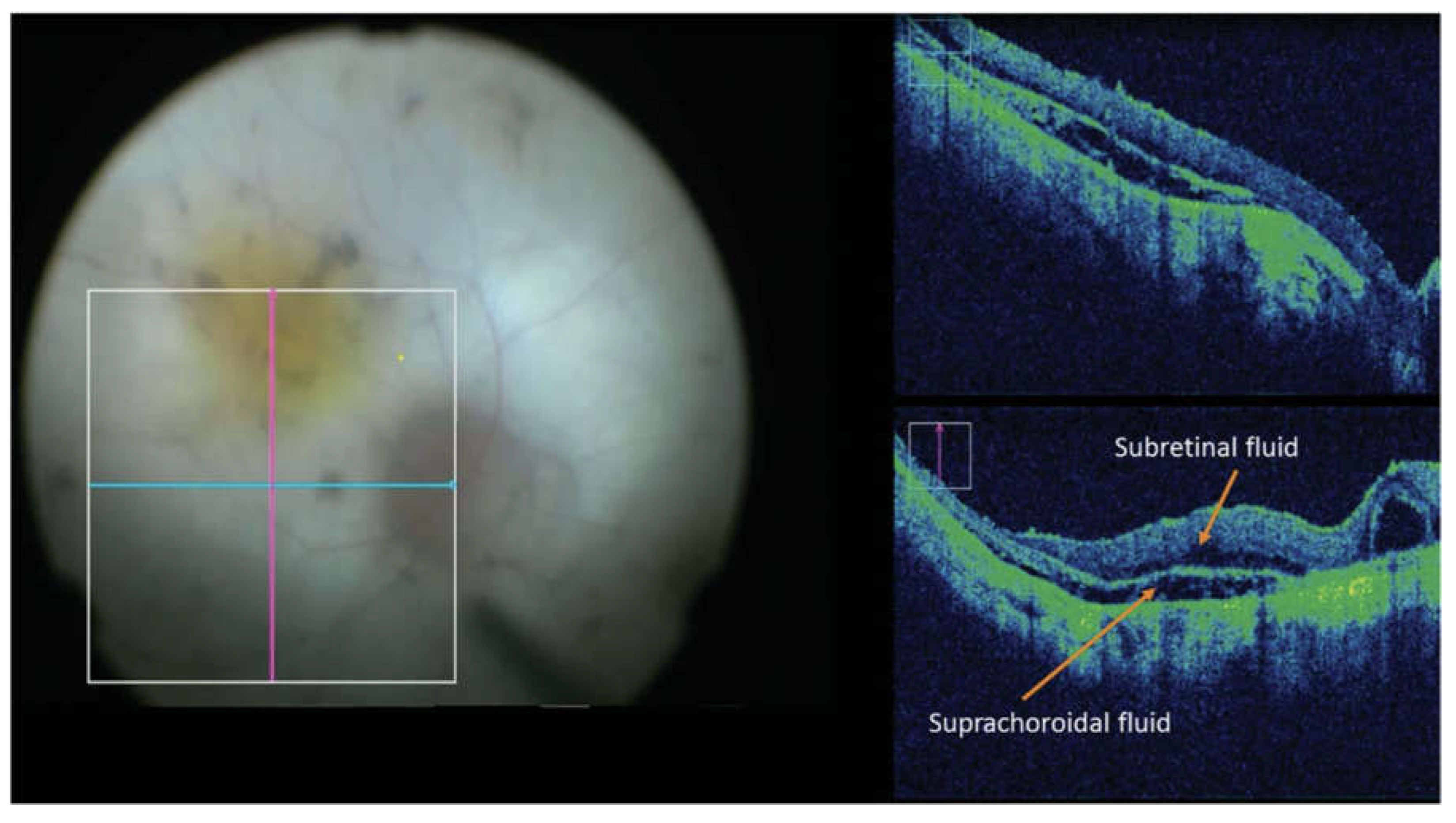

- Abraham, J.R.; Srivastava, S.K.; K Le, T.; Sharma, S.; Rachitskaya, A.; et al. Intraoperative OCT-Assisted Retinal Detachment Repair in the DISCOVER Study: Impact and Outcomes. 2020, 4, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydinger, S.; Ufret-Vincenty, R.; Robertson, Z.M.; He, Y.-G.; Wang, A.L. Comparison of Surgical Outcomes for Uncomplicated Primary Retinal Detachment Repair. 2023, 17, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.B.; Srivastava, S.K. Intraoperative Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography During Complex Retinal Detachment Repair. 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toygar, O.; Riemann, C.D. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography in macula involving rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair with pars plana vitrectomy and perfluoron. 2016, 30, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Ohr, M.P.; Kaiser, P.K.; Srivastava, S.K. Novel Microarchitectural Dynamics In Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachments Identified With Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography. 2013, 33, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, F.; Klaas, J.; Siedlecki, J.; Schworm, B.; Keidel, L.F.; et al. Internal Limiting Membrane Peeling in Primary Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: Functional and Morphologic Results. 2025, 242, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, N.Z.; Lam, B.L.; Davis, J.L. Intraoperative Use of Microscope-Integrated Optical Coherence Tomography for Subretinal Gene Therapy Delivery. 2019, 39, S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajzovic, L.; Sleiman, K.; Viehland, C.; Carrasco-Zevallos, O.M.; Klingeborn, M.; et al. Four-Dimensional Microscope-Integrated Optical Coherence Tomography Guidance in a Model Eye Subretinal Surgery. 2019, 39, S194–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.M.; Tran, K.D.; Berrocal, A.M.; Maguire, A.M. Subretinal Injection of Voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl in a Patient With <i>RPE65</i> -Associated Leber's Congenital Amaurosis. 2019, 50, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, H.M.; Lujan, B.J.; Pennesi, M.E.; Yang, P.; Lauer, A.K. Intraoperative optical coherence tomographic findings in patients undergoing subretinal gene therapy surgery. 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.P.; Petkovsek, D.S.; Yuan, A.; Singh, R.P.; Srivastava, S.K. Intrasurgical assessment of subretinal tPA injection for submacular hemorrhage in the PIONEER study utilizing intraoperative OCT. 2015, 46, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.G.; Cost, B.M.; Ehlers, J.P. Intraoperative OCT-Assisted Subretinal Perfluorocarbon Liquid Removal in the DISCOVER Study. 2015, 46, 964–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valikodath, N.G.; Li, J.D.; Raynor, W.; Izatt, J.A.; Toth, C.A.; et al. Intraoperative OCT-Guided Volumetric Measurements of Subretinal Therapy Delivery in Humans. 2024, 8, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavala, S.H.; Farsiu, S.; Maldonado, R.; Wallace, D.K.; Freedman, S.F.; et al. Insights into Advanced Retinopathy of Prematurity Using Handheld Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging. 2009, 116, 2448–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Markovitz, M.; Ferenczy, S.; Shields, C.L. Hand-held Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography of Small Macular Retinoblastoma in Infants Before and After Chemotherapy. 2014, 51, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seider, M.I.; Tran-Viet, D.; Toth, C.A. Macular Pseudo-Hole In Shaken Baby Syndrome. 2016, 10, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.L.; Folgar, F.A.; Tong, A.Y.; Toth, C.A. Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Characterization Of Pediatric Epiretinal Membranes. 2014, 34, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Viehland, C.; Carrasco-Zevallos, O.M.; Keller, B.; Vajzovic, L.; et al. Microscope-Integrated Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in the Operating Room in Young Children With Retinal Vascular Disease. 2017, 135, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, N.F.S.; Sengillo, J.D.; Hudson, J.L.; Carletti, P.; de Oliveira, G.; et al. Intraoperative OCT Angiography in Pediatric Patients with Persistent Fetal Vasculature. 2023, 7, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens, L.; Michiels, S.; Borrelli, M.; Spaniol, K.; Guthoff, R.; et al. Intraoperative OCT – Real-World User Evaluation in Routine Surgery. 2021, 238, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zee, C.; Muijzer, M.B.; van den Biggelaar, F.J.H.M.; Nuijts, R.M.M.A.; Delbeke, H.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of the ADVISE trial: An intraoperative OCT protocol in DMEK surgery. 2024, 102, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anterior Segment Scanning Computerized Ophthalmic Diagnostic Imaging - Medical Clinical Policy Bulletins | Aetna.

- Medical Policy Optical Coherence Tomography of the Anterior Eye Segment Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity.

- Ophthalmic OCT Reaches $1 Billion Per Year | Retinal Physician.

- Zakir, R.; Iqbal, K.; Hassaan Ali, M.; Tariq Mirza, U.; Mahmood, K.; et al. The outcomes and usefulness of Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography in vitreoretinal surgery and its impact on surgical decision making. 2022, 66, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intraoperative OCT: An Emerging Technology - American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).