1. Introduction

Since the implementation of the economic reform and opening-up policy in 1978, China has attracted significant foreign direct investment (FDI), which has played a transformative role in addressing capital shortages, enhancing technological capabilities, and accelerating economic modernization and internationalization. According to the World Investment Report 2023, China remains the world's second largest recipient of FDI, continuing to see growth in its inflows. While the direct economic impact of inward foreign direct investment (IFDI), such as export growth and job creation, are well-documented (Chen & Zhou, 2023), its indirect effects — particularly on host countries’ innovative entrepreneurship — remain contested (Sun et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024).

According to Blomstrom (1983), the indirect effects resulting from IFDI are referred to as externalities or spillovers. When focusing specifically on the spillover effects of IFDI on domestic firms’ innovative entrepreneurial activities, the results are often inconsistent. Existing studies present mixed evidence, with some scholars reveal positive spillover effects of IFDI in stimulating innovative entrepreneurial activities in host countries (Prelipcean,2023), others argue that the impacts are negative (Qamruzzaman et al., 2021), and some suggesting no significant effects (Albulescu & Tămăşilă, 2014). Scholars such as Lipsey (2013) and Javorcik (2004) express skepticism about the existence of FDI spillovers, noting that their presence depends on specific conditions such as the characteristics of individual firms, industry sectors, and national regulations. This divergence underscores the need to examine the contextual factors that shape FDI spillovers, particularly in developing countries like China, where institutional environments and economic conditions differ significantly from those in developed economies (Nam et al., 2023).

Numerous studies underscore the importance of institutional development in host countries as a prerequisite for attracting IFDI (Khan et al., 2022; Saha et al., 2022). These studies posit that a robust effective institutional framework mitigates major hurdles such as political instability, bureaucratic inefficiencies, corruption, and criminality, thereby fostering an economic environment conducive to foreign investment inflows (Nam et al., 2023). Munemo (2017) notes that the extent of the spillover effects of IFDI on entrepreneurial activities in host countries is contingent upon the development level of a country's financial institutions, highlighting that significant financial deepening is essential for absorbing the positive spillovers of IFDI. While Slesman et al. (2021) indicate that not all countries benefit equally from IFDI, it is primarily those with advanced institutional development that can effectively absorb positive spillovers, which otherwise might adversely impact the relationship between IFDI and entrepreneurship in host countries. The institutional environment of a country is considered to be one of the most important local conditions and a key factor linking IFID to the development of innovative entrepreneurship (Urbano et al., 2019). However, developing countries typically feature weak economic and governmental institutional structures, ongoing development, continuously evolving institutions, and higher receptiveness to change (Fon et al., 2021). Furthermore, IFDI can generate positive spillovers even within imperfect systems characterized by corruption, as corruption may sometimes act as a lubricant to facilitate the spillover effects of IFDI (Barassi & Zhou, 2012). Therefore, we contend that unlike in developed countries, FDI may produce heterogeneous outcomes in developing countries such as China, influenced by macro-level factors such as the degree of marketization.

This study addresses two critical research gaps. First, there is a notable scarcity of research on developing countries, in contrast to the extensive body of studies on developed countries (Nam & Ryu, 2023; Nam et al., 2023). As a developing country still deepening its economic institutional development, China offers a unique context to explore FDI spillover paths through institutional environments, moving beyond universal perspectives. This focus is crucial for understanding how developing countries can leverage foreign investment to foster sustainable institution and entrepreneurship development and reduce regional inequalities. Second, the role of macro-level institutional factors, such as marketization, in mediating the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship remains underexplored. By focusing on China—a developing country characterized by significant regional disparities in IFDI, institutional environment, and entrepreneurship—a detailed analysis of regional differences can elucidate the pivotal role of economic institutions in shaping FDI spillovers to innovative entrepreneurship.

The primary objective of this study is to demonstrate whether IFDI can facilitate or inhibit the absorptive capacity of institutions. This, in turn, generates either positive or negative spillover effects on innovative entrepreneurship. To achieve this, we first identify marketization as a proxy for economic institutions and conceptualize the absorptive capacity of institutions as the principal path of spillovers from IFDI. Finally, we assess whether IFDI affects the absorptive capacity of economic institutions, which in turn transmits spillover effects on innovative entrepreneurship in various regions of China. Our findings show that IFDI has a positive and significant spillover effect on innovative entrepreneurship in China, but no significant mediating effect of marketization. Regional heterogeneity analyses further reveal that IFDI has positive and significant spillover effect on innovative entrepreneurship and marketization in the eastern regions, with marketization playing a partially mediating role. However, in the central region, IFDI has a positive and significant spillover effect on innovative entrepreneurship, with no significant effect on marketization, and no mediating role. Finally, in the western region, IFDI has no significant spillover effect on either innovative entrepreneurship or marketization, and there is no significant mediating effect of marketization. Our results are robust and credible, as confirmed by the robustness tests.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 delineates the theoretical framework of this study.

Section 3 reviews prior studies, proposes the research hypotheses, outlines the research model, and

Section 4 describes the sample data and research methodology.

Section 5, presents our empirical results.

Section 6 discusses the empirical results, and concludes the paper.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Absorptive Capability of Institutions

A key component of a country's innovative entrepreneurial activity is the sourcing of external knowledge, technology, and information. The capability to utilize and assimilate this external knowledge is absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Absorptive capacity can manifest at the individual level (Enkel et al., 2017), enterprise or organizational level (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Zahra & George,2002), and national level (Criscuolo & Narula, 2008). At the national level, absorptive capacity pertains to a country's ability to learn and implement technologies and related practices from developed countries (Dahlman & Nelson, 1995), as well as socio-institutional conditions (social capabilities), namely, the country's education, trade, market, government, and financial institutions, which bear the ability to finance, innovate, and operate domestic enterprises, as well as the political and social capacity to influence economic activity risks, incentives, and individual returns (Castellacci & Natera, 2013).

The IFDI brings new external knowledge and key technologies, thereby enhancing the learning and absorptive capacity of domestic institutions and subsequently facilitating knowledge spillovers at the societal level. This generally exerts a positive influence on domestic innovative entrepreneurial activities (Nam et al., 2023). However, developing countries continue to suffer from low institutional quality (Huynh, 2020). Low institutional quality may hamper developing countries’ ability to absorb external knowledge from IFDI, thus failing to transmit positive spillovers to domestic innovative entrepreneurship activities (Criscuolo & Narula, 2008). Theoretically, as a conduit influencing the absorptive capacity of host country institutions, IFDI directly impacts individuals, enterprises, and economic and governmental institutions, as they can indirectly increase efficiency by accelerating knowledge learning and the uptake of technological changes (Nam et al., 2023). Second, IFDI can create employment opportunities for host countries, promote human capital flow, improve the business environment, and enhance absorptive capacity (Huynh, 2020). Third, IFDI can stimulate competition, compel host countries to reduce corruption, develop democratic policies and regulations, ensure diversified market transactions, and enhance the institutional quality and absorptive capacity of host countries (Dang, 2013). In brief, the impact of IFDI on the absorptive capacity of institutions can be aggregated upward from a range of entities, from institutions to individuals, ultimately contributing to the overall absorptive capacity of a country (Criscuolo & Narula, 2008).

Therefore, in this paper, we focus on China's economic institutions to study the spillover path of IFDI, arguing that the absorptive capacity of marketization plays a mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. Concurrently, the level of institutional absorptive capacity dictates whether the impact of IFDI on societal-level spillovers is positive or negative (Slesman et al., 2021). To this end, we conducted a differentiated study of three regions in China, each with varying levels of marketization development, to more clearly delineate the impact of IFDI on innovative entrepreneurship through societal spillovers.

2.2. Spillover Effects of IFDI

FDI flowing into host countries usually has both direct and indirect effects (Blomström & Persson, 1983). These direct impacts improve the host country's economy in the form of increased export revenues, job creation, and higher labor wages (Chen & Zhou, 2023). Indirect impacts, on the other hand, refer to externalities or spillover effects.

Arguably, one of the most significant contributions of IFDI is spillover effects, which can be of different types (Blomström & Persson, 1983). These effects influence not only the macro-environment of the host country but also the behavior of entities within that environment (Tian & Chen, 2016). At the macro level, foreign capital flowing into host countries with higher education levels can create more job opportunities for the wage sector because higher education levels reflect the host country's stronger absorptive capacity at the macro level, making it easier for multinational firms to outsource local economic activities (Berrill et al., 2020). In addition, IFDI can improve the macro environment of the host country to enhance absorptive capacity by promoting government optimization of resource allocation, promoting infrastructure construction, stabilizing the market trading environment, and improving the construction of the legal system, so that spillover effects can be disseminated to the social level over time to promote the development of economic activities (Christopoulou et al., 2021; Jahanger, 2021; Liu et al., 2024).

When spillovers spread from the societal level to industries, firms and individuals, horizontal knowledge spillovers are generated, allowing industries to enhance performance and productivity (Javorcik & Spatareanu, 2008); for domestic firms, enabling the emulation of new technologies, knowledge, and best practices to improve productivity, stimulate innovative research and development activities, and enhance their ability to absorb and reconfigure advanced knowledge and specialized skills by increasing competition with foreign investment (Christopoulou et al., 2021); For individuals, foreign investment spillovers can improve the quality of human capital, increase opportunities to cultivate skilled labor, facilitate the mobility of skilled labor from foreign firms to local firms, and create more opportunities for individuals to engage in innovative entrepreneurship (Berry, 2017; Yang, 2019).

To summarize, spillovers from the IFDI affect the institutional environment of the host country and enhance the absorptive capacity of institutions. In turn, institutions, as a pathway for spillover effects, diffuse spillover effects at the social level, stimulate innovation and R&D by individuals or firms, and promote innovative entrepreneurial activities. During this process, the IFDI spillover effect strengthens or diminishes the absorptive capacity of institutions, leading to the diffusion of institutions to the social layer or hindering the spillover effect. This allows us to explore the mediating role of institutions to capture whether they ultimately foster innovative entrepreneurship in each region of China.

3. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

3.1. IFDI and Economic Institution

North (1990) defines institutions as human-invented constraints that structure political, economic, and social interactions, often conceptualized as the "rules of the game." Economic institutions, on the other hand, specifically aim to reduce uncertainty by creating a stable framework governed by the rules of human interaction (Kaushal, 2021). Most literature explores the quality of the host country's institutions as a critical variable in the host country's ability to attract IFDI (Julio & Yook, 2016; Sabir et al., 2019; Huynh, 2020; Kapas, 2020). IFDI can indirectly or directly influence these "rules of the game," thereby shaping the institution environment in host country (Fon et al., 2021).

Scholars have extensively researched the impact of IFDI on a host country's economic institutional environment. Guo et al. (2020)pointed out that the entry of FDI into China accelerates the improvement of economic institutions and contributes to the enhancement of the absorptive capacity of marketization, because the IFDI imposes higher demands on fairness, efficiency, and transparency in market competition. Meanwhile, the entry of FDI also promotes changes in the market distribution and labor and personnel systems, facilitates resource allocation, and optimizes the absorptive capacity of the economic institution. Furthermore, FDI increases opportunities for a variety of transactions, stimulates institutional learning activities, and deepens the development of economic institutions (Islam et al., 2021). Long et al. (2015) note that the greater the scale of the IFDI, the more favorable the tax policies of the host country, resulting in a decrease in the arbitrariness of the foreign investment burden. Domestic firms can also receive higher levels of legal protection, and IFDI improves tax and legal systems. Nevertheless, studies have also identified that in African countries, despite the growing interest in IFDI for institutional reforms, considering the mixed nature of IFDI, the overall impact on the institutional environment of African countries has not been positively significant (Fon et al., 2021). Furthermore, excessive capital inflows and the emergence of oligopolistic industries can lead to liquidity challenges for domestic firms (Nam et al., 2023), thus negatively affecting the volatile institutional environment of the host country. In addition, FDI can directly influence the level of trade barriers through lobbying, acquisition of domestic firms, and other behaviors (Kokko & Blomström, 1996), deteriorating the host country's institutional environment and reducing the absorptive capacity of institutions.

Overall, a large amount of IFDI may contribute to the improvement of economic institutions, by enhancing competitive fairness and market efficiency, optimizing resource allocation, and improving the business environment to enhance the absorptive capacity of institutions. However, if IFDI disrupts the operational mechanism of the domestic market through malicious lobbying and acquisitions of domestic firms, it can lead to oligopolistic practices. This intensifies competition among domestic firms and may hinder the deepening of marketization, ultimately reducing institutions’ absorptive capacity. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of China's overall economic institution (marketization).

Although IFDI has played a proactive role in stimulating the process of China's marketization system by promoting systematic marketization reforms and innovations, it is also a classical truth that IFDI is mainly clustered in the eastern coastal regions and some central regions (W. S. Liu & Agbola, 2014). A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that the infrastructure in the eastern and central regions is more developed, and the Chinese government has provided more favorable policies for these areas (Liu et al., 2024). Additionally, the eastern and central regions have a higher concentration of highly qualified labor and skilled personnel than the western regions. According to previous studies, the host country's institutional environment has a threshold for absorbing potential spillovers from IFDI (Munemo, 2017). Weak economic institutions can limit the host country's ability to utilize and absorb potential spillovers from IFDI. As Hermes and Lensink (2003), Alfaro et al. (2004) and Durham (2004) clarify, host countries with poorly developed economic institutions fail to fully capitalize on the potential growth benefits of IFDI. Huynh (2020) also states that a significant amount of underground economic activity exists in developing countries as it bypasses the cumbersome controls and procedures of formal state institutions. This prevalence of informal economic activities reflects the weakness of economic institutions, which in turn hampers the ability of state institutions to absorb the spillover effects of IFDI.

Accordingly, we assume that due to the varying levels of economic development in the eastern, central, and western regions, the process of institutional development also differs, resulting in varying levels of marketization. The eastern and central regions have more advanced marketization compared to the western region. Consequently, IFDI will have a positive or negative impact on the absorption capacity of marketization in each region, and we propose the following hypotheses:

H1b: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the eastern region.

H1c: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the central region.

H1d: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the western region.

3.2. Economic Institution and Innovative Entrepreneurship

Innovation is not only an imperative part of a country's economic growth but, also a distinct component of entrepreneurship (Prelipcean, 2023). It must be acknowledged that the expected benefits of entrepreneurship primarily stem from a few innovative, high-growth firms rather than the moderate growth in employment and revenue of newly established enterprises after overcoming survival difficulties (Block et al., 2017). While factors affecting domestic innovative entrepreneurship can be attributed to various firm-specific or entrepreneur-specific aspects, but how macro approaches, such as institutional development, support or suppress innovative entrepreneurial behavior is also a hotly debated area of academic research.

The macro approach seeks to establish and maintain an institutional environment in which innovative entrepreneurship can flourish (Bradley et al., 2021). An effective economic institution that encourages capital formation, attracts international capital, allows for broad freedom of experimentation and creativity, and ensures that new firms have the opportunity to compete in the marketplace can promote the positive development of innovative entrepreneurial activities in the country (Acemoglu et al., 2018; Z. J. Acs et al., 2018; Bradley et al., 2021). In particular, an economic institution with secure property rights, well-functioning laws, free and open markets and stable monetary arrangements facilitates savings, capital formation and international investment, including R&D. At a more targeted level, laws and regulations that make entrepreneurship easy, protect innovation, allow for skilled labor mobility, encourage FDI in high-potential early stage firms, and allow for the reallocation of inefficiently used resources through bankruptcy are particularly conducive to innovative entrepreneurship (Carnahan et al., 2010; Acs et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2020). However, countries with low institutional quality have failed to encourage entrepreneurship. For example, when regulatory institutions are bureaucratic and complex, corruption is prevalent in government agencies, and excessive informal economic institutions replace formal institutions (Burns & Fuller, 2020). They encourage rent-seeking behaviors that divert resources away from productive activities, increase the cost of doing business, and are not conducive to innovative entrepreneurship (Chambers & Munemo, 2019). In addition, poor economic institutions do not provide adequate stimulus systems, thus blocking the ability of firms to innovate and reduce innovative entrepreneurial (Kumar & Borbora, 2016; Sendra-Pons et al., 2022).

Economic institutions play an essential role in boosting domestic innovative entrepreneurship. A well-established economic institution increases productivity, stimulates innovation and promotes domestic innovative entrepreneurship. Conversely, poor economic institutions lead to a turbulent market environment and increase the cost of entrepreneurship, impeding domestic innovative entrepreneurship. Therefore, we rationalize the following hypothesis:

H2a: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects China’s overall domestic innovative entrepreneurship.

In a study consisting of a group of 48 countries, Sendra-Pons et al. (2022) demonstrate that different social conditions (institutional development) between countries lead to variations in the development of entrepreneurial activities, emphasizing the potential impact of regional heterogeneity of institutions on innovative entrepreneurship. While sound economic institutions dominate in developed countries, developing countries tend to exhibit underdeveloped economic institutions, and such institutional gaps usually limit further economic development (Cao & Shi, 2021; Ramamurti & Hillemann, 2018) and hinder the development of domestic innovative entrepreneurial activities. Manimala and Wasdani (2015) also identify the prevalence of weak institutions such as underdeveloped institutions, unclear policies, insufficient governance and inhibitory cultures in emerging economies, which adversely affect the innovative entrepreneurship process. Beyond that, as we mentioned earlier, institutions in developing countries are still evolving and undergoing change. Internal frictions and contradictions arising from institutional change also negatively impact domestic innovative entrepreneurial activities (R. Wang & Zhou, 2020).

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the development of economic institutions is characterized by regional heterogeneity. Countries with better economic development tend to have well-developed institutional environments that positively stimulates domestic innovative entrepreneurship. While countries with less advanced economic development are still in the process of deepening their economic institutions and are in no position to bring favorable assistance to domestic innovative entrepreneurship. When examining the impact of the marketization process on innovative entrepreneurship in different regions of China, it is necessary to consider the impact of regional differences in the development of economic institution. We propose the following hypothesis:

H2b: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the eastern region.

H2c: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the central region.

H2d: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the western region.

3.3. Mediating Role of Economic Institution in the Relationship Between IFDI and Innovative Entrepreneurship

IFDI can foster the absorptive capacity of institutions and catalyze the development of innovative entrepreneurship. The channels through which the IFDI can boost the absorptive capacity of the institution include the acceleration of knowledge learning, technological change, the adoption of best practices, and the deepening of the marketization process. Simultaneously, IFDI creates jobs in the host country, facilitates human capital flow, and prompts improvements in the business environment. Additionally, by contributing to fairness, efficiency, and transparent competition in host country markets, IFDI forces host countries to reduce corruption and formulate democratic policies and regulations to ensure multiple transactions in the market (Dang, 2013; Huynh, 2020; Wang & Zhou, 2020; Nam et al., 2023).

In these processes, IFDI has contributed to the deepening of China's marketization process through the provision of capital, technology, and advanced concepts of institutional development. This has enabled economic institutions to learn and assimilate best practices, directly contributing to the further development of marketization and institutions' absorptive capacity. In addition, a well-developed economic institution (i.e., a more mature level of marketization) encourages international capital formation, allows for broad freedom of experimentation and creativity, and protects innovation, enabling easy innovative entrepreneurship (Acemoglu et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2020; Bradley et al., 2021). Conversely, a weaker level of marketization does not provide an adequate incentive. Foreign capital is prone to monopolistic tendencies, and corruption in domestic institutions is prevalent, encouraging rent-seeking behaviors that increase the cost of doing business and deter innovation (Chambers & Munemo, 2019; Sendra-Pons et al., 2022; Nam et al., 2023). At this point, marketization prevents the adequate and rational allocation of resources and factors, leading to a decline in absorptive capacity. This, in turn, presents extreme challenges to domestic firms that are unable to pursue innovative research and development activities in a troubled market environment, thus hampering the expansion of innovative entrepreneurship.

As a result, IFDI can either enhance or reduce an economic institution’s absorptive capacity, leading to a corresponding impact on domestic innovative entrepreneurship. When the absorptive capacity of marketization increases, innovative entrepreneurship is stimulated. When the absorptive capacity of marketization decreases, it hinders innovative entrepreneurship owing to negative indirect effects through the reduction of institutional absorptive capacity. Concurrently, the mechanism by which IFDI affects innovative entrepreneurship by enhancing or weakening the absorptive capacity of institutions also shows heterogeneous results across the three major regions of China where both IFDI and institutional development are unbalanced. Therefore, economic institutions (marketization) play a mediating role between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between overall IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in China.

H3b: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in the eastern China.

H3c: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in the central China.

H3d: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in the western China.

3.4. Research Model

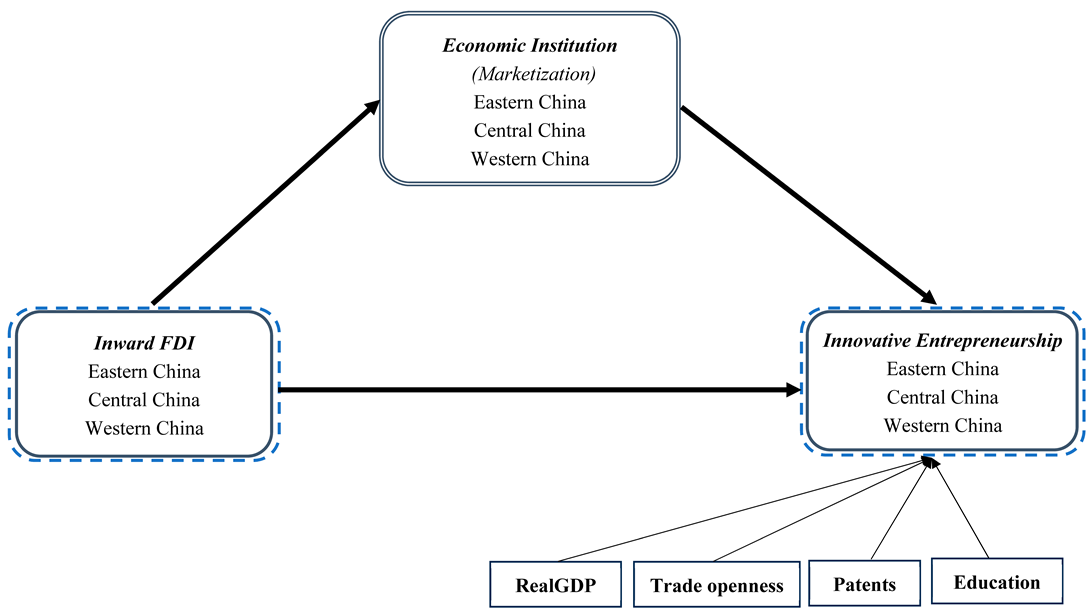

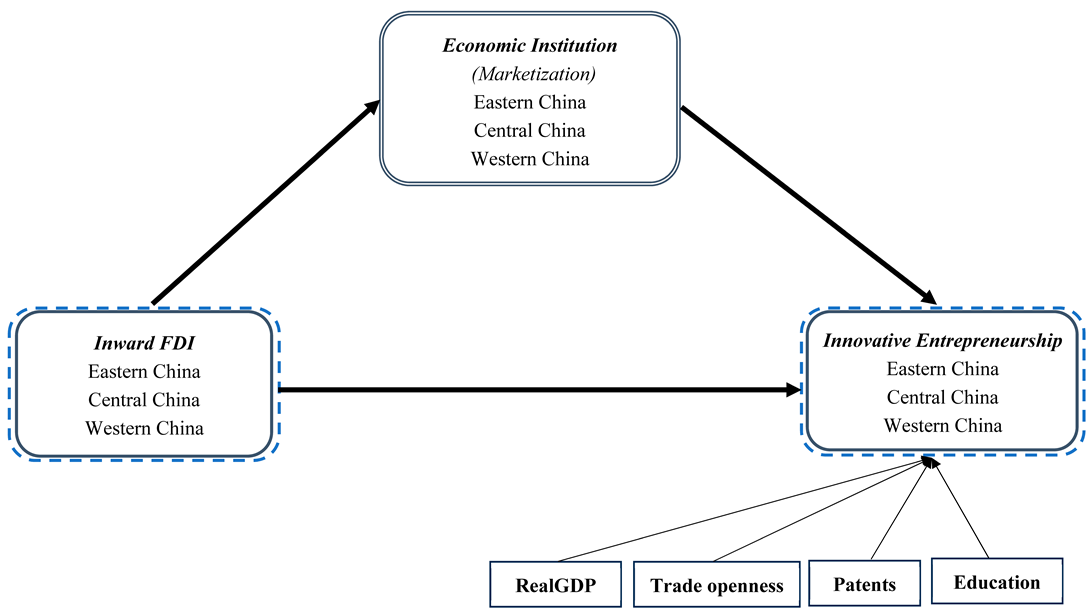

This study investigates the spillover effects of IFDI and the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in China. Figure 1 illustrates the research model used in this study. To achieve our research objectives, we first have to prove the direct relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship to demonstrate the spillover effect. Second, we must verify whether IFDI influences the development of marketization, thus upgrading or diminishing the absorptive capacity of the institution. Third, we test whether marketization affects the development of innovative entrepreneurship. Finally, we identify the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. We also include the following control variables in our research model: real GDP, trade openness, patents rate, and education rate.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data and Variables

Our study covers 30 provinces in China spanning 2010 to 2018 (excluding Tibet), encompassing 270 province-year observations. The key variables are: IFDI, marketization, innovative entrepreneurship, real GDP, trade openness, patents and education. Our data collection comes from reliable government databases established by Chinese officials. Specially, data on IFDI, real GDP, trade openness, and education come from the statistical yearbooks published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (CNBS). Marketization data are from the China Market Index Database (CMID), innovative entrepreneurship data are from the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC), and patent data are from China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Furthermore, we believe that 2010-2018 is an ideal window of time, as it lies between the global financial crisis of 2008 and the global COVID-19 pandemic of 2019. This period represents nine critical years of China's economic ascendancy without the distraction of huge international shocks. During this period, China became the world's second-ranked country in terms of GDP and IFDI.

The dependent variable is innovative entrepreneurship (IE). We measure innovative entrepreneurship in Chinese provinces by the number of private firms that have registered new patents or inventions, new products, or new services. In previous studies, Chen and Zhou (2023) used the number of firms that registered the licensing of invention patents to measure innovation entrepreneurship activities. In addition, according to Block et al. (2017) and Li et al. (2020), entrepreneurial activity in a region can be measured by the frequency of private firms’ creation, while innovative entrepreneurial activity can be measured by a private firm generating new products, inventions, services, or business portfolios. Thus, we suggest that private firms are motivated to undertake R&D and innovation activities when the spillover effects of IFDI reach at social level. Recording the number of private firms that engage in various innovative activities can be a useful indicator of innovative entrepreneurship. The independent variable is IFDI. Based on Guo et al. (2020), Qamruzzaman et al. (2021), Saha et al. (2022) and Nam et al. (2023), we use IFDI, an indicator that covers the inflow of foreign firms, economic organizations, and individuals investing in mainland China.

As mentioned earlier, we selected marketization, one of China's economic institutions, as the mediating variable in this study. According to Wang et al., (2007) and Li and Lu (2021), the market index (MI) includes five subordinate dimensions: government-market relationship, non-state economy, product market, factor market, and market intermediary organization, which is a representative metric for thoroughly measuring the level of marketization in Chinese provinces. We contend that IFDI is helpful in the development of marketization in each region to reinforce the ability to absorb spillovers. However, there is a substantial disparity in IFDI between the eastern, central and western regions (W. S. Liu & Agbola, 2014). This results in varying abilities of marketization to absorb spillovers, reflected in whether the diffusion of spillovers from marketization fosters innovative entrepreneurship in each region. Therefore, through this indicator, we are better able to capture the occurrence of mediation effects.

This study also includes a set of control variables: real GDP, trade openness, education, and patents rate. Real GDP excludes the influence of price changes, thus providing a more accurate reflection of a country's real economic growth. Trade openness represents the degree of freedom in a country's trade situation. If a country's policy is committed to increasing its trade openness, it will not only improve a country's standard of living and the overall economic situation, but will also have a positive impact on innovation activities (Dotta & Munyo, 2019; Saha et al., 2022). Higher education levels in host countries can potentiate the spillover effects of IFDI, as countries with higher education level are more likely to aggregate and incorporate new knowledge (Berrill, 2021), leading to the development of innovative entrepreneurship. The patent rate reflects a region's stock of knowledge, level of human capital devoted to innovative activities, and other resource commitments to support innovation (Liu et al., 2024). Patents rate plays an important role in influencing innovative entrepreneurship within a region.

Table 1 summarizes the definitions and sources of all the variables.

4.2. Research Methodology

To examine the relationship between marketization, IFDI, and innovative entrepreneurship, we use a panel data set. Among the methods of estimating regression models using panel data, it can generally be performed using pooled least squares, fixed effects, and random effects model (Zulfikar, 2018). In line with the vast literature on FDI, institutions, and innovative entrepreneurship, both fixed-effects and random-effects models are widely used (Albulescu & Tămăşilă, 2014; Junaid et al., 2022; Alomari & Ngo, 2023). Therefore, a Hausman test was conducted to determine which model is the most applicable to our study. The result of the Hausman test showed acceptance of the null hypothesis (p=0.000), indicating that our data are more suitable for the fixed-effect model. Fixed-effects models assume that differences between individuals (cross section) can be accommodated from different intercepts, using the least squares principle (Zulfikar, 2018). In addition, compared to pooled regression, fixed-effects models can be highly effective in eliminating correlated omitted variables that are constant within each firm or within each year (DeHaan, 2020).

To examine the spillover effects of IFDI and the mediating role of marketization in China's 30 provinces, as well as in three regions from 2010 to 2018, we first develop the baseline model Eqs. (1) This model assesses the direct effect of IFDI on innovative entrepreneurship:

where i denotes the province and t denotes the year. lnIE is the natural logarithmic form of the number of private firms that have registered new patents or inventions, new products, or services sourced from the CAIC. lnIFDI is the natural logarithmic form of inward foreign direct investment as recorded by the CNBS. To avoid the potential impact of omitted variables, we also set up a series of control variables (real GDP, patents rate, education rate, and trade openness) sourced from the CNBS and CNIPA. In addition, we set up regional dummy variables to account for the situations in the eastern, central, and western regions. Finally, μ represents individual effects, and ε represents idiosyncratic errors.

Subsequently, based on the three-step approach of mediation analysis proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), we develop the three-step regression model in Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively. First, we evaluate marketization as a function of IFDI in Eqs. (2). Next, we include IFDI and marketization in the same Eqs. (3) to examine the mediating role. In the hierarchical mediation analysis regression model, IFDI, as the independent variable, must be significant in Eqs. (1) and Eqs. (2), while the mediating variable marketization should be significant in Eqs. (3). Finally, if the IFDI is not significant in Eqs. (3), marketization plays a full mediating role; if the IFDI remains significant, marketization plays a partial mediating role.

5. Emprical Results

Table 2 lists the descriptive statistical information for all variables in this study. The data for the three main variables show considerable regional differences. For example, innovative entrepreneurship ranges from a minimum level of 0.693 (Hainan Province in 2017) to a maximum level of 8.997 (Zhejiang Province in 2014), IFDI ranges from a minimum of 6.100 (Qinghai Province in 2018) to a maximum of 15.090 (Jiangsu Province in 2012), and the level of marketization ranges from a minimum of 3.360 (Xinjiang in 2012) to a high of 11.380 (Shanghai in 2018). Overall, the data show a decreasing pattern from eastern, to the central and western. The eastern region has more IFDI, a higher level of marketization and more vigorous innovative entrepreneurial activities, while the western region has the least IFDI and a low level of marketization.

Table 3 summarizes the pairwise correlation matrix for all variables and the results of the multicollinearity test. The highly significant correlation of all variables at the 1% level suggests that there might be a problem of multicollinearity between the variables. However, our examination of multicollinearity indicates no such problem, as the range of VIF values from 1.92 to 6.28 does not exceed the generally accepted threshold of 10 (Hair et al., 1998).

A three-step hierarchical regression analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986) was used to test the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. Tables 4 to 5 conclude the fixed-effects regression results of the mediating effect for China as a whole and for the subregions, respectively. Tables 6 to 7 depict the fixed effects regression results with a one-year lag in IFDI as a robustness check.

In

Table 4, model (1) demonstrates that China's overall IFDI positively and significantly affects innovative entrepreneurship at the 1% level, while model (2) shows that China's overall IFDI does not have a significant spillover effect on the absorptive capacity of marketization.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the hierarchical regression of the mediating effects. Models (1) and (2) provide the necessary conditions to test the mediating role of marketization in model (3), however, the second step of the empirical results is not significant. Theoretically, in a three-step mediation analysis, the independent variable must significantly explain the change in the mediating variable (Baron & Kenny, 1986). In our study, this step is not verified. In model (3), marketization has no significant effect on the development of innovative entrepreneurship, so it does not satisfy the mediation test. This means that marketization does not play a mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship development in China.

Models (4) to (6) in

Table 5 summarize the mediating regression results of marketization in the eastern region, where IFDI positively and significantly spillover both innovative entrepreneurship and marketization at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Second, in mediation regression model (6), both IFDI and marketization positively affect innovative entrepreneurship at the 10% and 5% levels, indicating that marketization plays a partially mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship, with a mediation effect size of 0.053. Models (7) to (9) show the regression results for the mediating effect of marketization in the central region. IFDI only positively affects innovative entrepreneurship at the 1% significance level, but there is no significant spillover effect on the marketization. In the third step of the mediation regression in model (9), marketization does not significantly promote innovative entrepreneurship, indicating that marketization has no mediating role in the central region. Models (10) to (12) list the results of the mediation regression of marketization in the western region. Unfortunately, we find that neither IFDI nor marketization have a positive and significant impact on the development of innovative entrepreneurship activities in the western region.

The use of a one-period lagged independent variable is a common and effective approach for robustness testing. This method addresses potential endogeneity issues, determines whether reverse causality exists, and captures the dynamic effects of economic development (Bellemare et al., 2017). Hence, in

Table 6 and

Table 7, we re-analyze the mediating role of marketization between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship using IFDI lagged by one-period.

Table 6 reflects the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship for China as a whole. The results are consistent with those in

Table 4, confirming that marketization doesn’t play a mediating role in this relationship.

Table 7 displays the mediating role of marketization between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship by subregion. The results are consistent with those in

Table 5, showing that in the eastern region, marketization plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. However, in the central and western regions, there is still no theoretical mediating effect between this relationship.

Table 6 and

Table 7 confirm the robustness and validity of the results, respectively.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Results Discussion

A mediation analysis based on marketization in 30 provinces and the eastern, central, and western regions yields important insights. That is, the absorptive capacity of institutions is a crucial social channel that catalyzes the spillover effects of IFDI, significantly contributing to the development of innovative entrepreneurship in eastern China. Contrary to the prevalent opinion that many previous studies consider institutions as key determinants in attracting large inflows of FDI (Julio & Yook, 2016; Sabir et al., 2019; Huynh, 2020; Kapas, 2020), our study reveals that IFDI can actually enhance the host country's institutional environment, influence domestic "rules of the game", and upgrade the absorptive capacity of institutions. The substantial IFDI in eastern China has strengthened its economic institution’s absorptive capacity by introducing greater competitive equity and market efficiency, optimizing resource allocation, and refining the business environment. Favorable institutional absorptive capacity facilitates the diffusion of spillover effects from foreign investment at the social level, which leads to higher productivity, stimulates innovation, and spurs innovative entrepreneurship development in the eastern region.

However, the results for China as a whole and the central region show that IFDI only significantly influences innovative entrepreneurship, with no significant spillover effect on the absorptive capacity of marketization. Additionally, marketization does not significantly affect innovative entrepreneurship and its mediating role as a social channel for absorbing and diffusing FDI spillovers is absent. Previous studies have argued that the institutional environment has a threshold limitation on the ability to absorb potential spillovers from IFDI (Munemo, 2017). When institutional development is weak or in a stage of deepening development and evolving changes, it cannot fully capitalize on the potential benefits of spillovers from IFDI (Hermes & Lensink, 2003), which slows down the growth of the absorptive capacity of institutions. In our cases, the results confirmed previous studies. Due to the uneven progress of marketization in China, where regional and institutional deficiencies still exist, constraining the role of IFDI spillovers in enhancing the absorptive capacity of marketization despite the fact that the overall degree of marketization is increasing. Although the central region has a certain level of marketization, it has not yet been fully developed. The spillover effect fails to promote the improvement of the macro-institutional environment in central China, making it difficult for institutions to fully utilize the resources and opportunities brought about by foreign capital. While marketization does not act as a social channel for diffusing IFDI spillovers, these spillovers can stimulate the development of innovative entrepreneurship at the individual level through industries, enterprises, and individuals, which is consistent with the theory of FDI spillovers.

With regard to western China, however, the spillovers of IFDI on both innovative entrepreneurship and marketization remain insignificant, and marketization fails to play a mediating role. We contend that the western region still faces many challenges in attracting foreign investment and in utilizing it for sustainable economic development. The immaturity or imperfection of such institutions can slow down the absorption and localization of the technological and managerial knowledge brought about by IFDI. Additionally, the western region may not be conducive to efficient absorption and utilization of IFDI because of its geographically remote location, relative lack of infrastructure, and human resource constraints. These regional characteristics lead to higher operating costs for foreign firms, and relatively weaker spillover effects affect the effective absorption of external resources through marketization.

The empirical results of this study reveal a complex scenario characterized by heterogeneity in the absorptive capacity of economic institutions as a vital conduit for diffusing the spillover effects of IFDI. In host countries or regions where the institutional environment is more developed, IFDI spillovers can positively raise the absorptive capacity of institutions, fully diffusing the potential benefits of IFDI and stimulating the development of innovative entrepreneurship. However, in host countries or regions with a less developed institutional environment, such as central and western China, the potential spillover effects of IFID cannot influence the absorptive capacity of institutions, thus failing to effectively diffuse spillovers to promote innovative entrepreneurship.

Accordingly, the study recommends that although IFDI can help host countries improve their institutions and upgrade their absorptive capacity, it can utilize the potential benefits of stimulating domestic innovative entrepreneurship and improving returns to innovative entrepreneurship. However, developing countries should focus on deepening the development of their domestic institutional environment. Weak economic institutions slow down the ability to absorb the spillover effects of IFDI and impede the diffusion of capital bonuses, human benefits and sophisticated managerial experience brought about by the IFDI at the social level. This failure hinders the development of innovative entrepreneurship in the country.

Our study provides new and insightful ways of understanding the relationship between IFDI, economic institutions, and innovative entrepreneurship. This study indicates the heterogeneous effects of IFDI in enhancing the absorptive capacity of institutions and acting as a pathway for diffusing spillovers to innovative entrepreneurship in China and across different regions. These findings add crucial nuanced evidence not only to the absorptive capacity theory of institutions, but also to the spillover effect theory of FDI. To wit, the absorptive capacity of institutions plays an important mediating role between FDI in innovation and entrepreneurship, serving as a vital conduit for the diffusion of spillovers. Although developing countries or regions with weak institutions may not fully utilize this crucial channel to energize innovative entrepreneurship for the time being, it provides an important reference for developing countries and regions.

To conclude, our study expands prior knowledge in the framework of institutional absorptive capacity and spillover effects, providing practical implications for governments and firms. Drawing on these insights, this study highlights the need for strategies to promote and enhance the institutional absorptive capacity of developing countries to fully utilize IFDI and diffuse its spillover effects, so that innovative entrepreneurship can flourish.

6.2. Policy Implication

The Chinese Government should consider formulating a differentiated regional development strategy, particularly to strengthen support for the marketization process in the central and western regions. Moreover, there is a need to alleviate the imbalance in IFDI by expanding FDI inflows in the central and western regions through more FDI-attracting policies, thereby increasing the absorptive capacity of these regions for FDI spillovers. Meanwhile, the eastern regions should continue optimizing the market environment to attract more FDI and promote its positive impact on local innovative entrepreneurship through institutional innovation. Policymakers should also focus on upgrading human capital and technological foundations through education, training and infrastructure development to further stimulate the positive interaction between the marketization process and IFDI.

6.3. Managerial Implication

For enterprise managers, understanding regional differences in the institutional environment is crucial for setting effective innovative entrepreneurship strategies. In regions with more favorable economic institutions, firms should take advantage of the favorable institutional environment and policy support to strengthen cooperation with foreign firms and acquire more technological and managerial knowledge. In regions with less favorable economic institutions, firms need to pay more attention to internal capacity building to compensate for the lack of external support. Furthermore, enterprises should actively participate in the discussion and formulation of local policies and seek more support to optimize their operating environments.

6.4. Limitations

Admittedly, there are some limitations in our study. For example, future research could determine where the threshold value of institutional absorptive capacity lies. Second, how do government institutions affect IFDI and the development of innovative entrepreneurship in a country given that government institutions also play a significant role in the macro-level environment. Finally, spillover effects may occur at the social, industrial or individual level, so it is worthwhile to investigate whether research on other two channels would yield different results. We hope that future studies can test and develop our theory on this basis to improve the generalizability of our findings.

6.5. Conclusions

This study investigates the mediating role of economic institutions (marketization) in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in 30 provinces as well as three regions (eastern, central, and western) from 2010 to 2018. Previous studies present conflict view on the impact of FDI and innovative entrepreneurship, ranging from positive to negative. This study introduces economic institution as a critical mediator to reconcile these differences. We argue that spillovers from IFDI are the impetus for innovative entrepreneurship development in China, while the absorptive capacity of the economic institution is a pivotal bridge determining whether these spillovers are effectively released into domestic innovative entrepreneurship. IFDI facilitate the acquisition of knowledge, technology and best practices by institution at an accelerated pace, foster healthy competition, enhance institutional quality, and increase absorptive capacity. These improvements enable institutions to channel spillover effects smoothly at the social level, encouraging firms and individuals to utilize external resources for innovative entrepreneurship. This study makes two key contributions. First, it advances the literature on FDI spillovers by highlighting the mediating role of economic institutions, particularly in the context of developing countries, where institutional development is ongoing and uneven. Second, this study constructs a bridge linking foreign capital inflows to innovative entrepreneurship, emphasizing the heterogeneous nature of this bridge across regions. Our analysis reveals that the mediating effects of economic institutions vary significantly between the eastern, central, and western regions of China, reflecting differences in institutional development and marketization levels. This regional heterogeneity underscores the need for tailored policies that account for local institutional contexts to maximize the spillover effects of IFDI.