Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

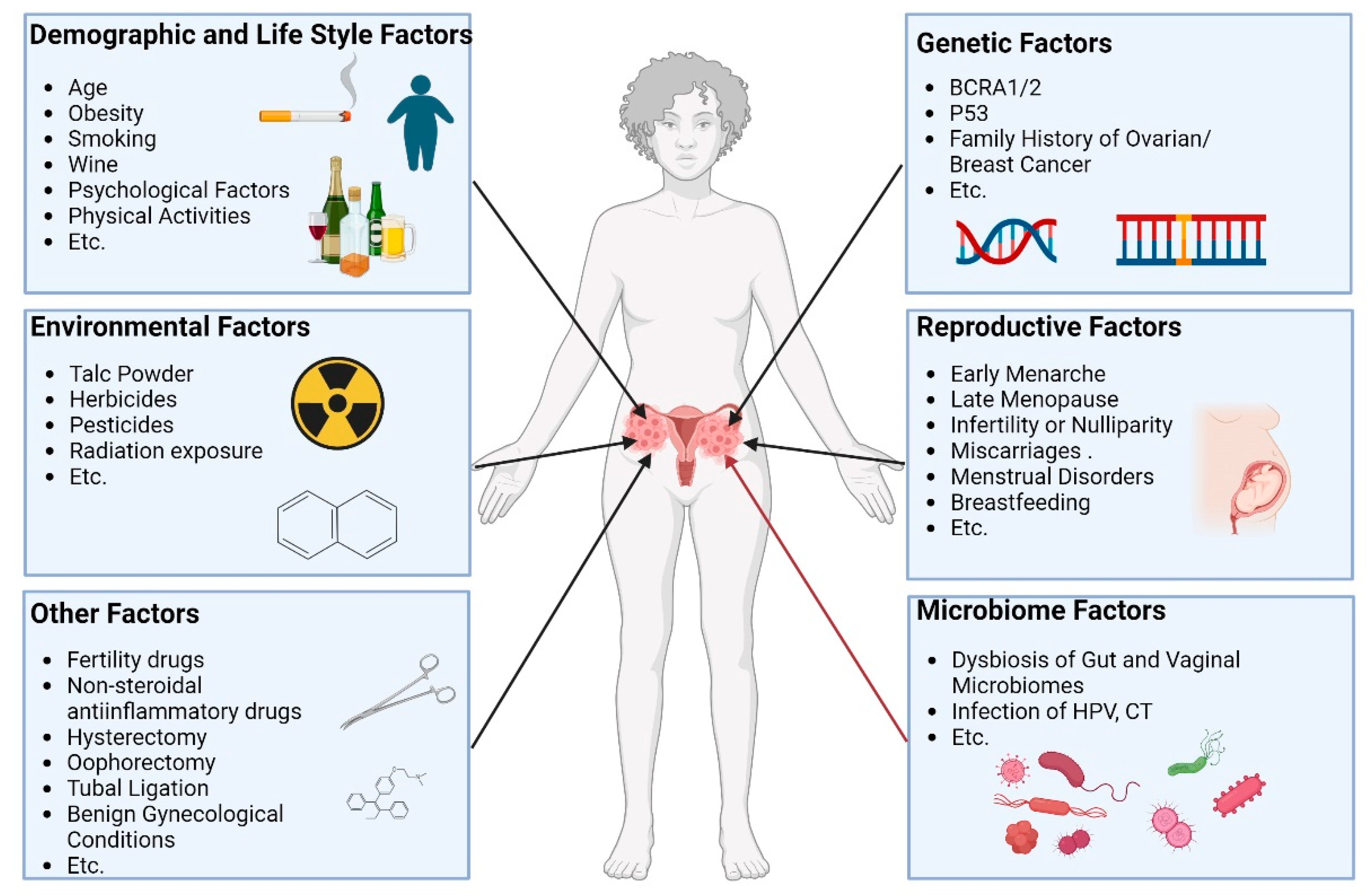

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Gut and Vaginal Microbiota in Ovarian Cancer

2.1. Characteristics of Gut and Vaginal Microbiota in Health Women

2.2. Characteristics of Gut and Vaginal Microbiota in Patients with Ovarian Cancer

3. Interaction of Gut and Vaginal Microbiome

3.1. Evidences of the Interaction of Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes

3.2. Possible Mechanisms of the Interaction of Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes

4. Potential Mechanisms of Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes in Ovarian Cancer

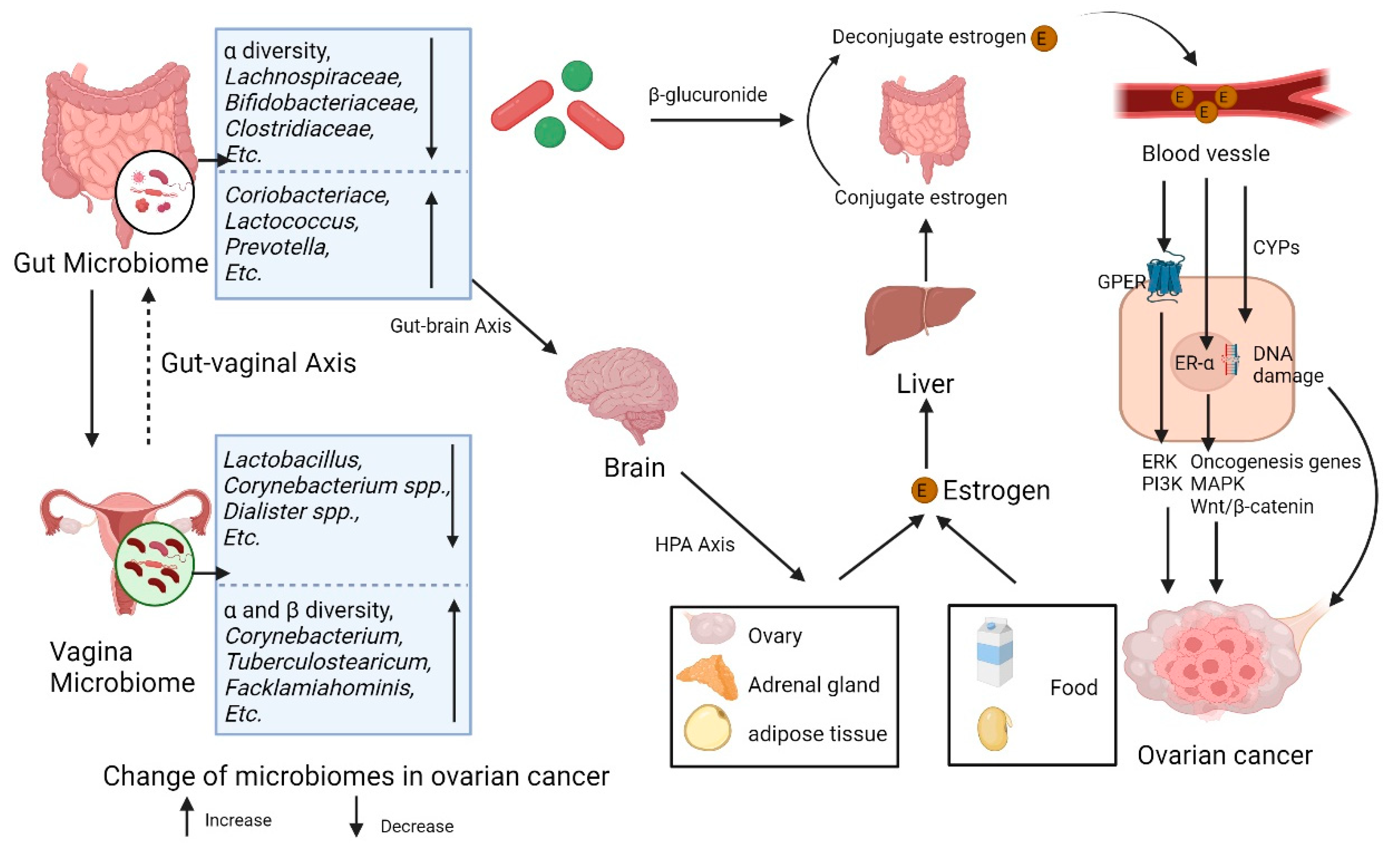

4.1. Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes and Estrogen in Ovarian Cancer

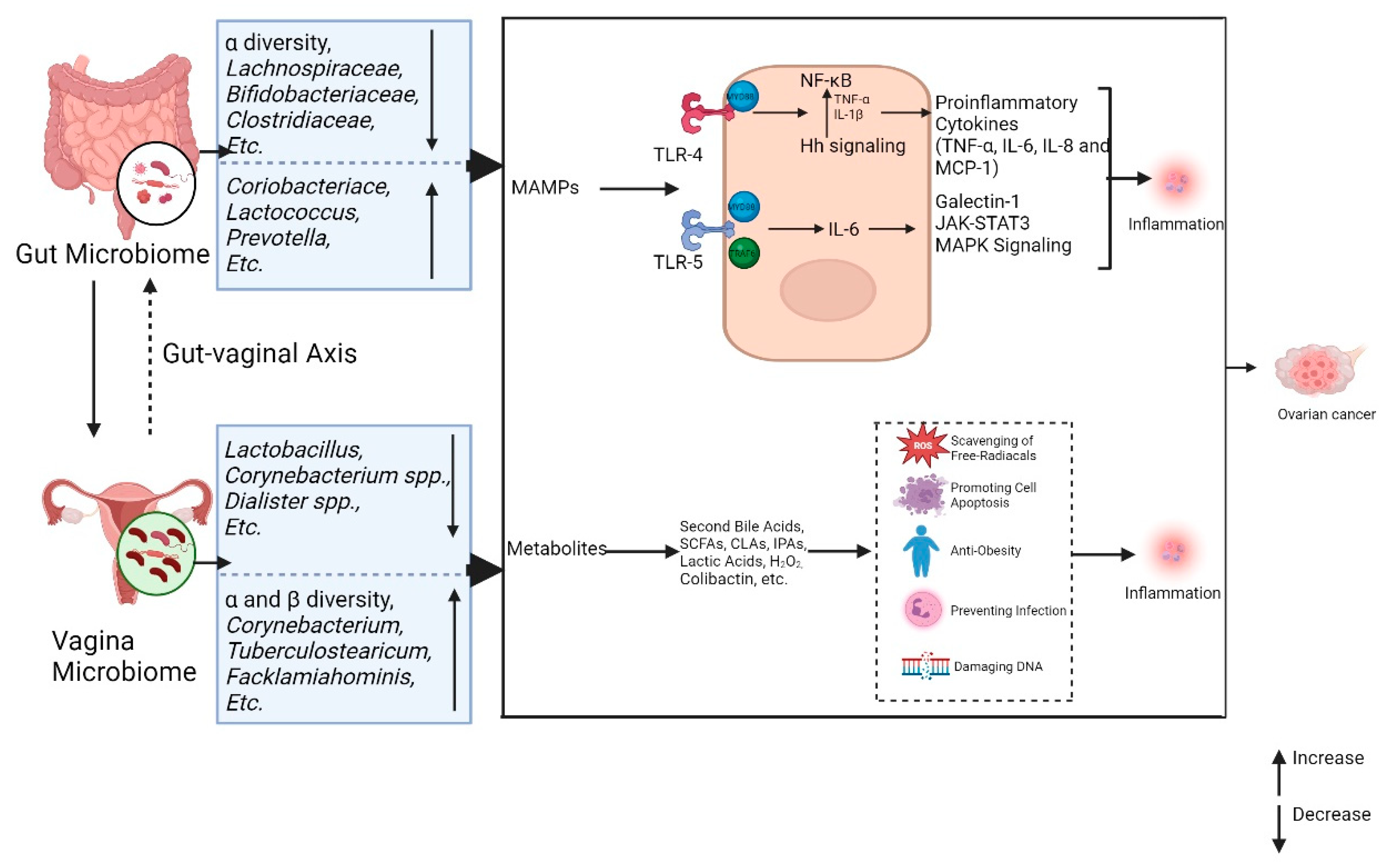

4.2. Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes and Inflammation in Ovarian Cancer

4.3. Gut and Vaginal Microbiomes and Inflammation in Ovarian Cancer

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BRAY F, LAVERSANNE M, SUNG H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–63. [CrossRef]

- SIEGEL R L, MILLER K D, WAGLE N S, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023 [J]. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73, 17–48. [CrossRef]

- TORRE L A, TRABERT B, DESANTIS C E, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018 [J]. CA Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 284–96. [CrossRef]

- HUANG J, CHAN W C, NGAI C H, et al. Worldwide Burden, Risk Factors, and Temporal Trends of Ovarian Cancer: A Global Study [J]. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- RICHARDSON D L, ESKANDER R N, O'MALLEY D M. Advances in Ovarian Cancer Care and Unmet Treatment Needs for Patients With Platinum Resistance: A Narrative Review [J]. JAMA Oncol 2023, 9, 851–9. [CrossRef]

- CHIONH F, MITCHELL G, LINDEMAN G J, et al. The role of poly adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase inhibitors in breast and ovarian cancer: current status and future directions [J]. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2011, 7, 197–211. [CrossRef]

- ITAMOCHI H, KIGAWA J. Clinical trials and future potential of targeted therapy for ovarian cancer [J]. Int J Clin Oncol 2012, 17, 430–40. [CrossRef]

- ZHOU P, WANG J, MISHAIL D, et al. Recent advancements in PARP inhibitors-based targeted cancer therapy [J]. Precis Clin Med 2020, 3, 187–201. [CrossRef]

- GONZáLEZ-MARTíN A, POTHURI B, VERGOTE I, et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer [J]. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 2391–402. [CrossRef]

- KöBEL M, KANG E Y. The Evolution of Ovarian Carcinoma Subclassification [J]. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- SCHOUTROP E, MOYANO-GALCERAN L, LHEUREUX S, et al. Molecular, cellular and systemic aspects of epithelial ovarian cancer and its tumor microenvironment [J]. Seminars In Cancer Biology 2022,86(Pt 3): 207-23. [CrossRef]

- MA R, TANG Z, WANG J. NLRP12 is a prognostic biomarker and correlated with immune infiltrates in epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. J Gene Med 2023, e3585. [CrossRef]

- WEBB P M, JORDAN S J. Epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2017, 41. [CrossRef]

- BIEGING K T, MELLO S S, ATTARDI L D. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression [J]. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 359–70. [CrossRef]

- GENG S, ZHANG X, ZHU X, et al. Psychological factors increase the risk of ovarian cancer [J]. J Obstet Gynaecol 2023, 43, 2187573. [CrossRef]

- ALI A T, AL-ANI O, AL-ANI F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer [J]. Prz Menopauzalny 2023,22(2). [CrossRef]

- LA VECCHIA, C. Ovarian cancer: epidemiology and risk factors [J]. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017, 26, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- WISHART D S, OLER E, PETERS H, et al. MiMeDB: the Human Microbial Metabolome Database [J]. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D611–D20. [CrossRef]

- BELKAID Y, HAND T W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation [J]. Cell 2014, 157, 121–41. [CrossRef]

- POSTLER T S, GHOSH S. Understanding the Holobiont: How Microbial Metabolites Affect Human Health and Shape the Immune System [J]. Cell Metab 2017, 26, 110–30. [CrossRef]

- CHEN Y, XIAO L, ZHOU M, et al. The microbiota: a crucial mediator in gut homeostasis and colonization resistance [J]. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1417864. [CrossRef]

- MA C, JIANG M, LI J, et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus DNA load for diagnostic and prognostic assessment in intestinal Epstein-Barr Virus infection [J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1526633. [CrossRef]

- YOU L, ZHOU J, XIN Z, et al. Novel directions of precision oncology: circulating microbial DNA emerging in cancer-microbiome areas [J]. Precis Clin Med 2022, 5, pbac005. [CrossRef]

- RUTKOWSKI M R, STEPHEN T L, SVORONOS N, et al. Microbially driven TLR5-dependent signaling governs distal malignant progression through tumor-promoting inflammation [J]. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 27–40. [CrossRef]

- NENé N R, REISEL D, LEIMBACH A, et al. Association between the cervicovaginal microbiome, BRCA1 mutation status, and risk of ovarian cancer: a case-control study [J]. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 1171–82. [CrossRef]

- JACOBSON D, MOORE K, GUNDERSON C, et al. Shifts in gut and vaginal microbiomes are associated with cancer recurrence time in women with ovarian cancer [J]. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11574. [CrossRef]

- MUNGENAST F, THALHAMMER T. Estrogen biosynthesis and action in ovarian cancer [J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014, 5, 192. [CrossRef]

- BORELLA F, CAROSSO A R, COSMA S, et al. Gut Microbiota and Gynecological Cancers: A Summary of Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Future Directions [J]. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 987–1009. [CrossRef]

- MATEI D, NEPHEW K P. Epigenetic Attire in Ovarian Cancer: The Emperor's New Clothes [J]. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 3775–85. [CrossRef]

- BäCKHED F, LEY R E, SONNENBURG J L, et al. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine [J]. Science 2005, 307, 1915–20.

- LOZUPONE C A, STOMBAUGH J I, GORDON J I, et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota [J]. Nature 2012, 489, 220–30. [CrossRef]

- RINNINELLA E, RAOUL P, CINTONI M, et al. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases [J]. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- YOON K, KIM N. Roles of Sex Hormones and Gender in the Gut Microbiota [J]. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021, 27, 314–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PUGH J N, LYDON K M, O'DONOVAN C M, et al. More than a gut feeling: What is the role of the gastrointestinal tract in female athlete health? [J]. Eur J Sport Sci 2022, 22, 755–64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIDDIQUI R, MAKHLOUF Z, ALHARBI A M, et al. The Gut Microbiome and Female Health [J]. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- KOLIADA A, MOSEIKO V, ROMANENKO M, et al. Sex differences in the phylum-level human gut microbiota composition [J]. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 131. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG D, XI Y, FENG Y. Ovarian cancer risk in relation to blood lipid levels and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational epidemiologic studies [J]. Eur J Cancer Prev 2021, 30, 161–70. [CrossRef]

- NEUMAN H, DEBELIUS J W, KNIGHT R, et al. Microbial endocrinology: the interplay between the microbiota and the endocrine system [J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2015, 39, 509–21. [CrossRef]

- SANTOS-MARCOS J A, RANGEL-ZUñIGA O A, JIMENEZ-LUCENA R, et al. Influence of gender and menopausal status on gut microbiota [J]. Maturitas 2018, 116, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- ANAHTAR M N, GOOTENBERG D B, MITCHELL C M, et al. Cervicovaginal Microbiota and Reproductive Health: The Virtue of Simplicity [J]. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 159–68. [CrossRef]

- SMITH S B, RAVEL J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology [J]. J Physiol 2017, 595, 451–63. [CrossRef]

- GAJER P, BROTMAN R M, BAI G, et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota [J]. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 132ra52. [CrossRef]

- RAVEL J, GAJER P, ABDO Z, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 (Suppl 1), 4680–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FRANCE M, ALIZADEH M, BROWN S, et al. Towards a deeper understanding of the vaginal microbiota [J]. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 367–78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MANCABELLI L, TARRACCHINI C, MILANI C, et al. Vaginotypes of the human vaginal microbiome [J]. Environ Microbiol 2021, 23, 1780–92. [CrossRef]

- GREENBAUM S, GREENBAUM G, MORAN-GILAD J, et al. Ecological dynamics of the vaginal microbiome in relation to health and disease [J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019, 220, 324–35. [CrossRef]

- CHAMPER M, WONG A M, CHAMPER J, et al. The role of the vaginal microbiome in gynaecological cancer [J]. BJOG 2018, 125, 309–15. [CrossRef]

- ASANGBA A E, CHEN J, GOERGEN K M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of the microbiome in ovarian cancer treatment response [J]. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 730. [CrossRef]

- EL BAIRI K, KANDHRO A H, GOURI A, et al. Emerging diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers for ovarian cancer [J]. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2017, 40, 105–18. [CrossRef]

- HU X, XU X, ZENG X, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis promotes the development of epithelial ovarian cancer via regulating Hedgehog signaling pathway [J]. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2221093. [CrossRef]

- D'AMICO F, PERRONE A M, RAMPELLI S, et al. Gut Microbiota Dynamics during Chemotherapy in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients Are Related to Therapeutic Outcome [J]. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- CHAMBERS L M, ESAKOV RHOADES E L, BHARTI R, et al. Disruption of the Gut Microbiota Confers Cisplatin Resistance in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer [J]. Cancer Research 2022, 82, 4654–69. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Y, ZHANG X-R, PARK J-L, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles altered by Helicobacter pylori in gastric mucosa and blood leukocyte DNA [J]. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 37132–44. [CrossRef]

- TRABERT B, WATERBOER T, IDAHL A, et al. Antibodies Against Chlamydia trachomatis and Ovarian Cancer Risk in Two Independent Populations [J]. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019, 111, 129–36. [CrossRef]

- SHARMA H, TAL R, CLARK N A, et al. Microbiota and pelvic inflammatory disease [J]. Semin Reprod Med 2014, 32, 43–9. [CrossRef]

- ANTONIO M A D, RABE L K, HILLIER S L. Colonization of the rectum by Lactobacillus species and decreased risk of bacterial vaginosis [J]. J Infect Dis 2005, 192, 394–8.

- EL AILA N A, TENCY I, CLAEYS G, et al. Identification and genotyping of bacteria from paired vaginal and rectal samples from pregnant women indicates similarity between vaginal and rectal microflora [J]. BMC Infect Dis 2009, 9, 167. [CrossRef]

- SHIN H, MARTINEZ K A, HENDERSON N, et al. Partial convergence of the human vaginal and rectal maternal microbiota in late gestation and early post-partum [J]. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 37. [CrossRef]

- FUDABA M, KAMIYA T, TACHIBANA D, et al. Bioinformatics Analysis of Oral, Vaginal, and Rectal Microbial Profiles during Pregnancy: A Pilot Study on the Bacterial Co-Residence in Pregnant Women [J]. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- DI PIERRO F, CRISCUOLO A A, DEI GIUDICI A, et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus crispatus M247 to papillomavirus-infected women: results of a preliminary, uncontrolled, open trial [J]. Minerva Obstet Gynecol 2021, 73, 621–31. [CrossRef]

- JANG S-E, JEONG J-J, CHOI S-Y, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14 Attenuate Gardnerella vaginalis-Infected Bacterial Vaginosis in Mice [J]. Nutrients 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- LIU Y, LI H-T, ZHOU S-J, et al. Effects of vaginal seeding on gut microbiota, body mass index, and allergy risks in infants born through cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial [J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 100793. [CrossRef]

- YUAN C, GASKINS A J, BLAINE A I, et al. Association Between Cesarean Birth and Risk of Obesity in Offspring in Childhood, Adolescence, and Early Adulthood [J]. JAMA Pediatr 2016, 170, e162385. [CrossRef]

- KRISTENSEN K, HENRIKSEN L. Cesarean section and disease associated with immune function [J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 137, 587–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PLOTTEL C S, BLASER M J. Microbiome and malignancy [J]. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 324–35. [CrossRef]

- KWA M, PLOTTEL C S, BLASER M J, et al. The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer [J]. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016, 108. [CrossRef]

- ERVIN S M, LI H, LIM L, et al. Gut microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate estrogens as components of the estrobolome that reactivate estrogens [J]. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 18586–99. [CrossRef]

- BUCHTA, V. Vaginal microbiome [J]. Ceska Gynekol 2018, 83, 371–9. [Google Scholar]

- CLAES I J, VARGAS GARCíA C E, LEBEER S. Novel opportunities for the exploitation of host-microbiome interactions in the intestine [J]. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2015, 32, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- LEBEER S, VANDERLEYDEN J, DE KEERSMAECKER S C J. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens [J]. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 171–84. [CrossRef]

- ILHAN Z E, ŁANIEWSKI P, THOMAS N, et al. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling [J]. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 675–90. [CrossRef]

- SCOTT A J, ALEXANDER J L, MERRIFIELD C A, et al. International Cancer Microbiome Consortium consensus statement on the role of the human microbiome in carcinogenesis [J]. Gut 2019, 68, 1624–32. [CrossRef]

- RAFTOGIANIS R, CREVELING C, WEINSHILBOUM R, et al. Estrogen metabolism by conjugation [J]. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2000, 113–24.

- RUGGIERO R J, LIKIS F E. Estrogen: physiology, pharmacology, and formulations for replacement therapy [J]. J Midwifery Womens Health 2002, 47, 130–8. [CrossRef]

- CUI J, SHEN Y, LI R. Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during aging: from periphery to brain [J]. Trends Mol Med 2013, 19, 197–209. [CrossRef]

- PROSSNITZ E R, BARTON M. The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in health and disease [J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011, 7, 715–26. [CrossRef]

- SEYED HAMEED A S, RAWAT P S, MENG X, et al. Biotransformation of dietary phytoestrogens by gut microbes: A review on bidirectional interaction between phytoestrogen metabolism and gut microbiota [J]. Biotechnol Adv 2020, 43, 107576. [CrossRef]

- TKALIA I G, VOROBYOVA L I, SVINTSITSKY V S, et al. Clinical significance of hormonal receptor status of malignant ovarian tumors [J]. Exp Oncol 2014, 36, 125–33.

- CHOI J-H, WONG A S T, HUANG H-F, et al. Gonadotropins and ovarian cancer [J]. Endocr Rev 2007, 28, 440–61.

- BAKER J M, AL-NAKKASH L, HERBST-KRALOVETZ M M. Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications [J]. Maturitas 2017, 103, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- POLLET R M, D'AGOSTINO E H, WALTON W G, et al. An Atlas of β-Glucuronidases in the Human Intestinal Microbiome [J]. Structure 2017, 25. [CrossRef]

- TETEL M J, DE VRIES G J, MELCANGI R C, et al. Steroids, stress and the gut microbiome-brain axis [J]. J Neuroendocrinol 2018, 30. [CrossRef]

- MAENG L Y, BEUMER A. Never fear, the gut bacteria are here: Estrogen and gut microbiome-brain axis interactions in fear extinction [J]. Int J Psychophysiol 2023, 189, 66–75. [CrossRef]

- DINAN T G, SCOTT L V. Anatomy of melancholia: focus on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis overactivity and the role of vasopressin [J]. J Anat 2005, 207, 259–64.

- OYOLA M G, HANDA R J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes: sex differences in regulation of stress responsivity [J]. Stress 2017, 20, 476–94. [CrossRef]

- TRABERT B, COBURN S B, FALK R T, et al. Circulating estrogens and postmenopausal ovarian and endometrial cancer risk among current hormone users in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study [J]. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 1201–11. [CrossRef]

- SHI L-F, WU Y, LI C-Y. Hormone therapy and risk of ovarian cancer in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Menopause 2016, 23, 417–24. [CrossRef]

- CUNAT S, HOFFMANN P, PUJOL P. Estrogens and epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Gynecologic Oncology 2004, 94, 25–32.

- LIU A, ZHANG D, YANG X, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha activates MAPK signaling pathway to promote the development of endometrial cancer [J]. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 17593–601. [CrossRef]

- GOAD J, KO Y-A, KUMAR M, et al. Oestrogen fuels the growth of endometrial hyperplastic lesions initiated by overactive Wnt/β-catenin signalling [J]. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1105–16. [CrossRef]

- LIU X, ZHAN T, GAO Y, et al. Benzophenone-1 induced aberrant proliferation and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells via activated ERα and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways [J]. Environ Pollut 2022, 292, 118370. [CrossRef]

- SIMPKINS F, JANG K, YOON H, et al. Dual Src and MEK Inhibition Decreases Ovarian Cancer Growth and Targets Tumor Initiating Stem-Like Cells [J]. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 4874–86. [CrossRef]

- PETRIE W K, DENNIS M K, HU C, et al. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-selective ligands modulate endometrial tumor growth [J]. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013, 2013, 472720. [CrossRef]

- DE VISSER K E, JOYCE J A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth [J]. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHAO H, WU L, YAN G, et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention [J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VAN TUIJL L A, VOOGD A C, DE GRAEFF A, et al. Psychosocial factors and cancer incidence (PSY-CA): Protocol for individual participant data meta-analyses [J]. Brain Behav 2021, 11, e2340. [CrossRef]

- ARDEN-CLOSE E, GIDRON Y, MOSS-MORRIS R. Psychological distress and its correlates in ovarian cancer: a systematic review [J]. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 1061–72. [CrossRef]

- HOTAMISLIGIL G, S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders [J]. Nature 2006, 444, 860–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HULDANI H, ABDUL-JABBAR ALI S, AL-DOLAIMY F, et al. The potential role of interleukins and interferons in ovarian cancer [J]. Cytokine 2023, 171, 156379. [CrossRef]

- GAO J, XU K, LIU H, et al. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Intestinal Immunity Mediated by Tryptophan Metabolism [J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 13. [CrossRef]

- FACHI J L, SéCCA C, RODRIGUES P B, et al. Acetate coordinates neutrophil and ILC3 responses against C. difficile through FFAR2 [J]. J Exp Med 2020, 217. [CrossRef]

- WOODS D C, WHITE Y A, DAU C, et al. TLR4 activates NF-κB in human ovarian granulosa tumor cells [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 409, 675–80. [CrossRef]

- KELLY M G, ALVERO A B, CHEN R, et al. TLR-4 signaling promotes tumor growth and paclitaxel chemoresistance in ovarian cancer [J]. Cancer Research 2006, 66, 3859–68.

- LUPI L A, CUCIELO M S, SILVEIRA H S, et al. The role of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway in ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers [J]. Life Sci 2020, 247, 117435. [CrossRef]

- KASPERCZYK H, BAUMANN B, DEBATIN K-M, et al. Characterization of sonic hedgehog as a novel NF-kappaB target gene that promotes NF-kappaB-mediated apoptosis resistance and tumor growth in vivo [J]. FASEB J 2009, 23, 21–33. [CrossRef]

- WANG Y, JIN G, LI Q, et al. Hedgehog Signaling Non-Canonical Activated by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma [J]. Journal of Cancer 2016, 7, 2067–76. [CrossRef]

- VLAD C, DINA C, KUBELAC P, et al. Expression of toll-like receptors in ovarian cancer [J]. J BUON 2018, 23, 1725–31.

- XU S, LIU Z, LV M, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by activating tumor-associated macrophages in ovarian cancer [J]. Pathogens and Disease 2019, 77. [CrossRef]

- BROWNING L, PATEL M R, HORVATH E B, et al. IL-6 and ovarian cancer: inflammatory cytokines in promotion of metastasis [J]. Cancer Manag Res 2018, 10, 6685–93. [CrossRef]

- SIPOS A, UJLAKI G, MIKó E, et al. The role of the microbiome in ovarian cancer: mechanistic insights into oncobiosis and to bacterial metabolite signaling [J]. Mol Med 2021, 27, 33. [CrossRef]

- BEGLEY M, GAHAN C G M, HILL C. The interaction between bacteria and bile [J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2005, 29, 625–51.

- HOROWITZ N S, HUA J, POWELL M A, et al. Novel cytotoxic agents from an unexpected source: bile acids and ovarian tumor apoptosis [J]. Gynecologic Oncology 2007, 107, 344–9.

- SUN M, WU W, LIU Z, et al. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases [J]. J Gastroenterol 2017, 52, 1–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHAO L-Y, MEI J-X, YU G, et al. Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications [J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 201. [CrossRef]

- WIKOFF W R, ANFORA A T, LIU J, et al. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 3698–703. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KE C, HOU Y, ZHANG H, et al. Large-scale profiling of metabolic dysregulation in ovarian cancer [J]. Int J Cancer 2015, 136, 516–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BOSSUET-GREIF N, VIGNARD J, TAIEB F, et al. The Colibactin Genotoxin Generates DNA Interstrand Cross-Links in Infected Cells [J]. mBio 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- CHáVEZ-TALAVERA O, TAILLEUX A, LEFEBVRE P, et al. Bile Acid Control of Metabolism and Inflammation in Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Dyslipidemia, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease [J]. Gastroenterology 2017, 152. [CrossRef]

- POLS T W H, NOMURA M, HARACH T, et al. TGR5 activation inhibits atherosclerosis by reducing macrophage inflammation and lipid loading [J]. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 747–57. [CrossRef]

- GOMES A C, HOFFMANN C, MOTA J F. The human gut microbiota: Metabolism and perspective in obesity [J]. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 308–25. [CrossRef]

- OUCHI N, WALSH K. Adiponectin as an anti-inflammatory factor [J]. Clin Chim Acta 2007, 380, 24–30. [CrossRef]

- CANFORA E E, JOCKEN J W, BLAAK E E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity [J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015, 11, 577–91. [CrossRef]

- YOU H, TAN Y, YU D, et al. The Therapeutic Effect of SCFA-Mediated Regulation of the Intestinal Environment on Obesity [J]. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 886902. [CrossRef]

- SHANMUGHAPRIYA S, SENTHILKUMAR G, VINODHINI K, et al. Viral and bacterial aetiologies of epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 31, 2311–7. [CrossRef]

- PATHAK S, WILCZYŃSKI J R, PARADOWSKA E. Factors in Oncogenesis: Viral Infections in Ovarian Cancer [J]. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- RAHBAR SAADAT Y, POURSEIF M M, ZUNUNI VAHED S, et al. Modulatory Role of Vaginal-Isolated Lactococcus lactis on the Expression of miR-21, miR-200b, and TLR-4 in CAOV-4 Cells and In Silico Revalidation [J]. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2020, 12, 1083–96. [CrossRef]

- XIE X, YANG M, DING Y, et al. Microbial infection, inflammation and epithelial ovarian cancer [J]. Oncology Letters 2017, 14, 1911–9. [CrossRef]

- MOUFARRIJ S, DANDAPANI M, ARTHOFER E, et al. Epigenetic therapy for ovarian cancer: promise and progress [J]. Clin Epigenetics 2019, 11, 7. [CrossRef]

- SCHöNDORF T, EBERT M P, HOFFMANN J, et al. Hypermethylation of the PTEN gene in ovarian cancer cell lines [J]. Cancer Lett 2004, 207, 215–20.

- YANG Q, YANG Y, ZHOU N, et al. Epigenetics in ovarian cancer: premise, properties, and perspectives [J]. Mol Cancer 2018, 17, 109. [CrossRef]

- CAI M, HU Z, LIU J, et al. Expression of hMOF in different ovarian tissues and its effects on ovarian cancer prognosis [J]. Oncol Rep 2015, 33, 685–92. [CrossRef]

- SANTOS J C, RIBEIRO M L. Epigenetic regulation of DNA repair machinery in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis [J]. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 9021–37. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG P-P, ZHOU L, CAO J-S, et al. Possible Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Association with HPV18 or HPV33 Infection [J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016, 17, 2959–64.

- PAPASTERGIOU V, KARATAPANIS S, GEORGOPOULOS S D. Helicobacter pylori and colorectal neoplasia: Is there a causal link? [J]. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 649–58. [CrossRef]

- TAHARA T, HIRATA I, NAKANO N, et al. Potential link between Fusobacterium enrichment and DNA methylation accumulation in the inflammatory colonic mucosa in ulcerative colitis [J]. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 61917–26. [CrossRef]

- JEFFERY I B, O'TOOLE P W. Diet-microbiota interactions and their implications for healthy living [J]. Nutrients 2013, 5, 234–52. [CrossRef]

- HAQUE S, RAINA R, AFROZE N, et al. Microbial dysbiosis and epigenetics modulation in cancer development - A chemopreventive approach [J]. Seminars In Cancer Biology 2022, 86 (Pt 3), 666–81. [CrossRef]

- WOO V, ALENGHAT T. Epigenetic regulation by gut microbiota [J]. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2022407. [CrossRef]

- RAJIĆ J, INIC-KANADA A, STEIN E, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis Infection Is Associated with E-Cadherin Promoter Methylation, Downregulation of E-Cadherin Expression, and Increased Expression of Fibronectin and α-SMA-Implications for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition [J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 253. [CrossRef]

- KUMAR H, LUND R, LAIHO A, et al. Gut microbiota as an epigenetic regulator: pilot study based on whole-genome methylation analysis [J]. mBio 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- LI L, CHENG R, WU Y, et al. Diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease [J]. J Evid Based Med 2024, 17, 409–33. [CrossRef]

- ZENG Z, JIANG M, LI X, et al. Precision medicine in inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Precis Clin Med 2023, 6, pbad033. [CrossRef]

- MA C, CHEN K, LI L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus Infection Exacerbates Ulcerative Colitis by Driving Macrophage Pyroptosis via the Upregulation of Glycolysis [J]. Precis Clin Med 2025. [CrossRef]

- MADDAMS J, PARKIN D M, DARBY S C. The cancer burden in the United Kingdom in 2007 due to radiotherapy [J]. Int J Cancer 2011, 129, 2885–93. [CrossRef]

- ZAMWAR U M, ANJANKAR A P. Aetiology, Epidemiology, Histopathology, Classification, Detailed Evaluation, and Treatment of Ovarian Cancer [J]. Cureus 2022, 14, e30561. [CrossRef]

- STRATTON J F, PHAROAH P, SMITH S K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of family history and risk of ovarian cancer [J]. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998, 105, 493–9.

- YANG-HARTWICH Y, SOTERAS M G, LIN Z P, et al. p53 protein aggregation promotes platinum resistance in ovarian cancer [J]. Oncogene 2015, 34, 3605–16. [CrossRef]

- BEWTRA C, WATSON P, CONWAY T, et al. Hereditary ovarian cancer: a clinicopathological study [J]. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1992, 11, 180–7.

- BANDERA E V, LEE V S, RODRIGUEZ-RODRIGUEZ L, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Ovarian Cancer Treatment and Survival [J]. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 5909–14.

- FABER M T, KJæR S K, DEHLENDORFF C, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of 21 case-control studies [J]. Cancer Causes Control 2013,24(5). [CrossRef]

- GAITSKELL K, GREEN J, PIRIE K, et al. Histological subtypes of ovarian cancer associated with parity and breastfeeding in the prospective Million Women Study [J]. Int J Cancer 2018, 142, 281–9. [CrossRef]

- GREISER C M, GREISER E M, DöREN M. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of ovarian cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Hum Reprod Update 2007, 13, 453–63.

- ROTHMAN K, GREENLAND S, LASH T. Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition [J]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008,P2272.

- JU L, SUO Z, LIN J, et al. Fecal microbiota and metabolites in the pathogenesis and precision medicine for inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Precis Clin Med 2024, 7, pbae023. [CrossRef]

- ANDRYKOWSKI M, A. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Participation in Ovarian Cancer Screening [J]. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MENON U, GRIFFIN M, GENTRY-MAHARAJ A. Ovarian cancer screening--current status, future directions [J]. Gynecologic Oncology 2014, 132, 490–5. [CrossRef]

| Study | Study design | Participants | Associated outcomes |

| D'Amico 2021[47] | Cohort study |

|

Gut microbiota:

|

| Hu 2023[46] | Case-control study |

|

Gut microbiota:

|

| Asangba 2023[44] | Cohort study |

|

Vaginal microbiota:

|

| Nené 2019[21] | Case-control study |

|

Vaginal microbiota:

|

| Jacobson 2021[22] | Cohort Study |

|

Gut microbiota:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).