Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Multi-Source Data Fusion Processing Method

2.1. Optimal Estimation Method

2.1.1. General LSE and Weighted LSE (WLSE)

2.1.2. MLE

2.1.3. MAPE

2.1.4. MVE

2.1.5. LMVE

2.1.6. Comparison of Several Different Optimal Estimation Methods

2.2. Filtering Algorithm

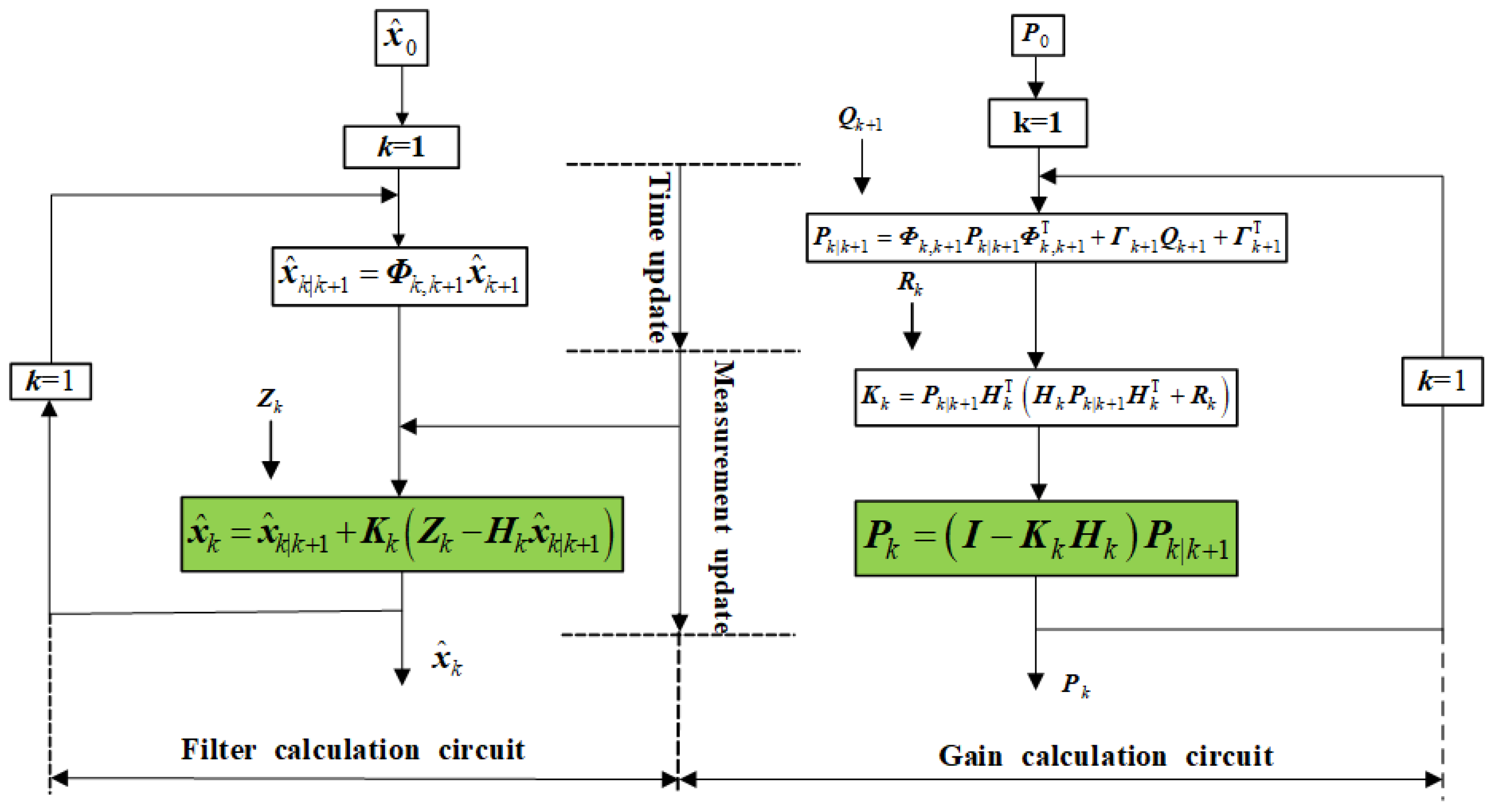

2.2.1. Standard KF

2.2.2. Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)

2.2.3. Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF)

2.2.4. Particle Filter (PF)

2.2.5. UKF-Based Particle Filter (UPF)

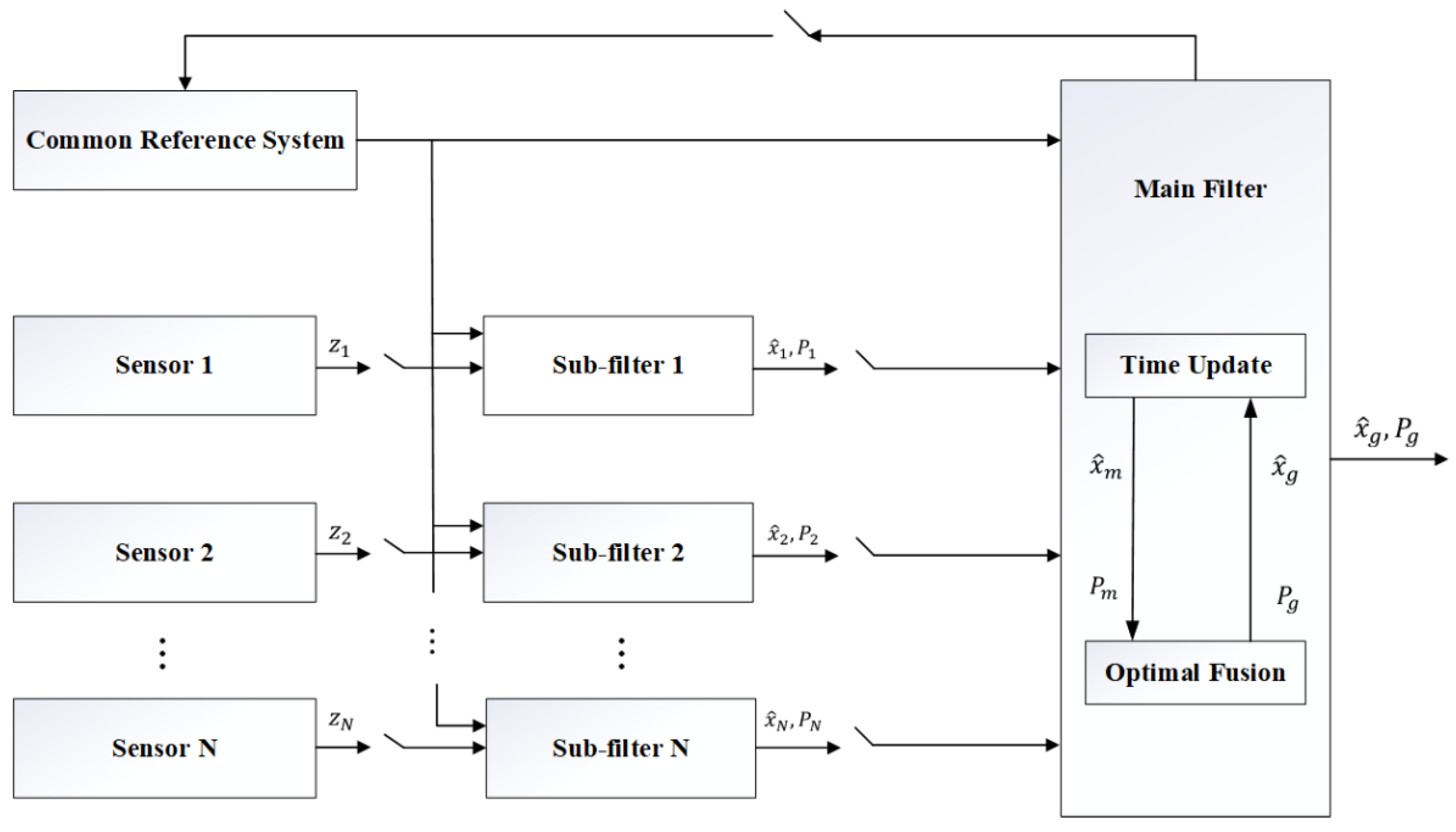

2.2.6. Federated Filtering (FF)

2.2.7. Comparison of Different Filtering Method

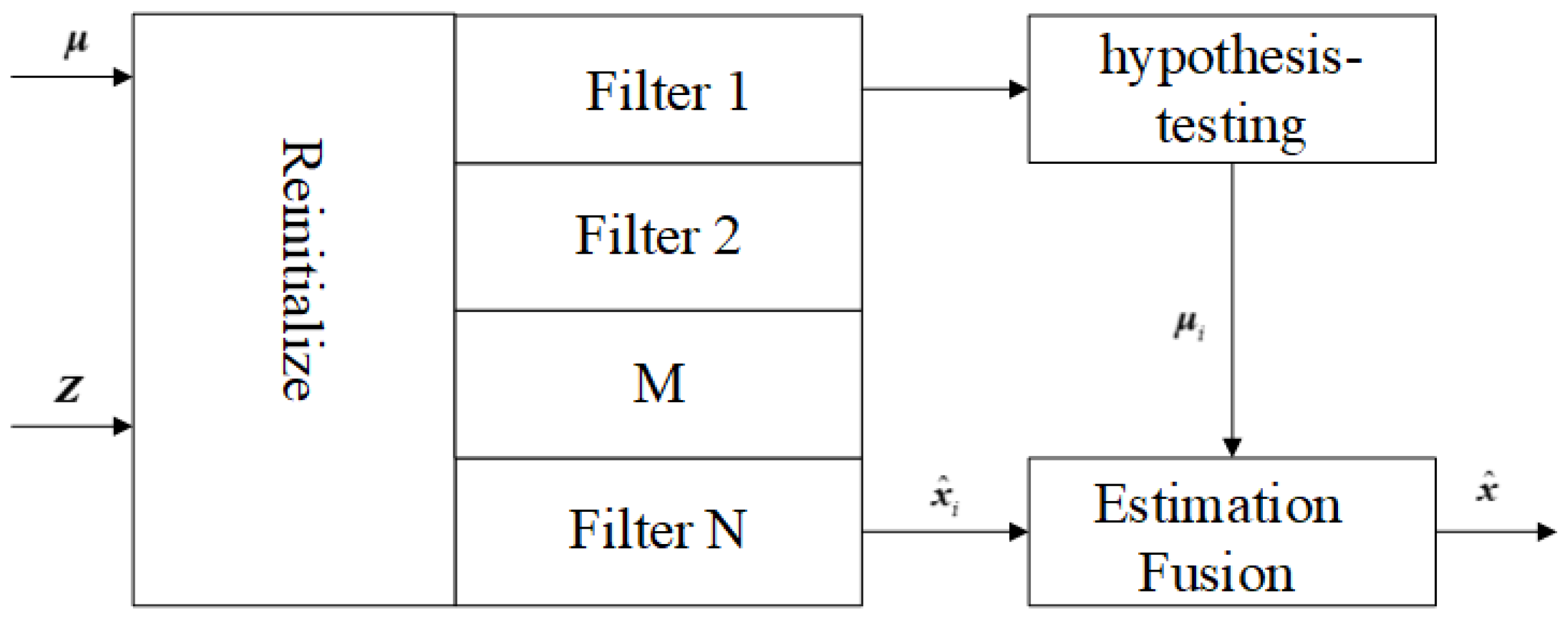

2.3. Multiple Model Estimation (MME)

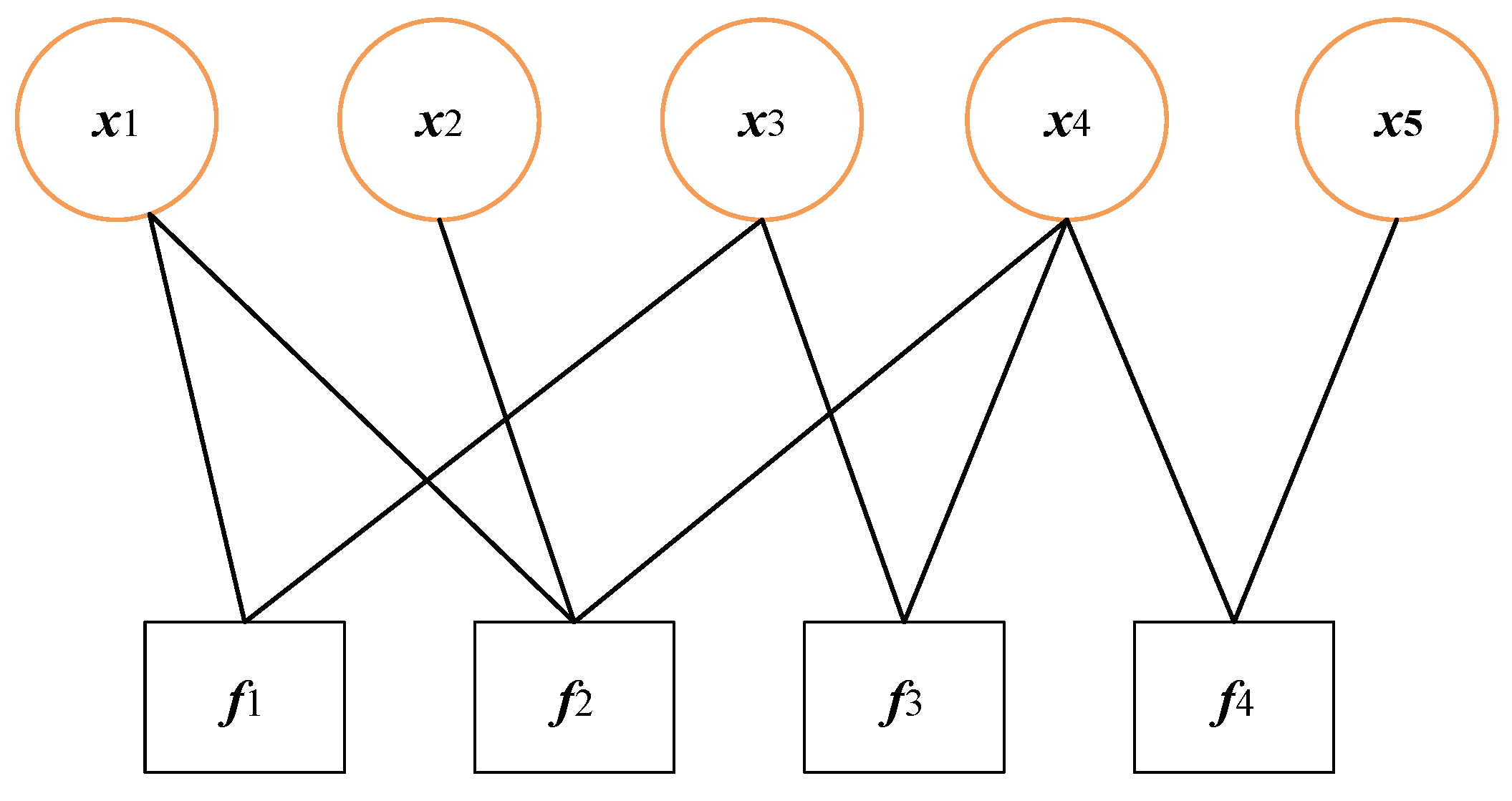

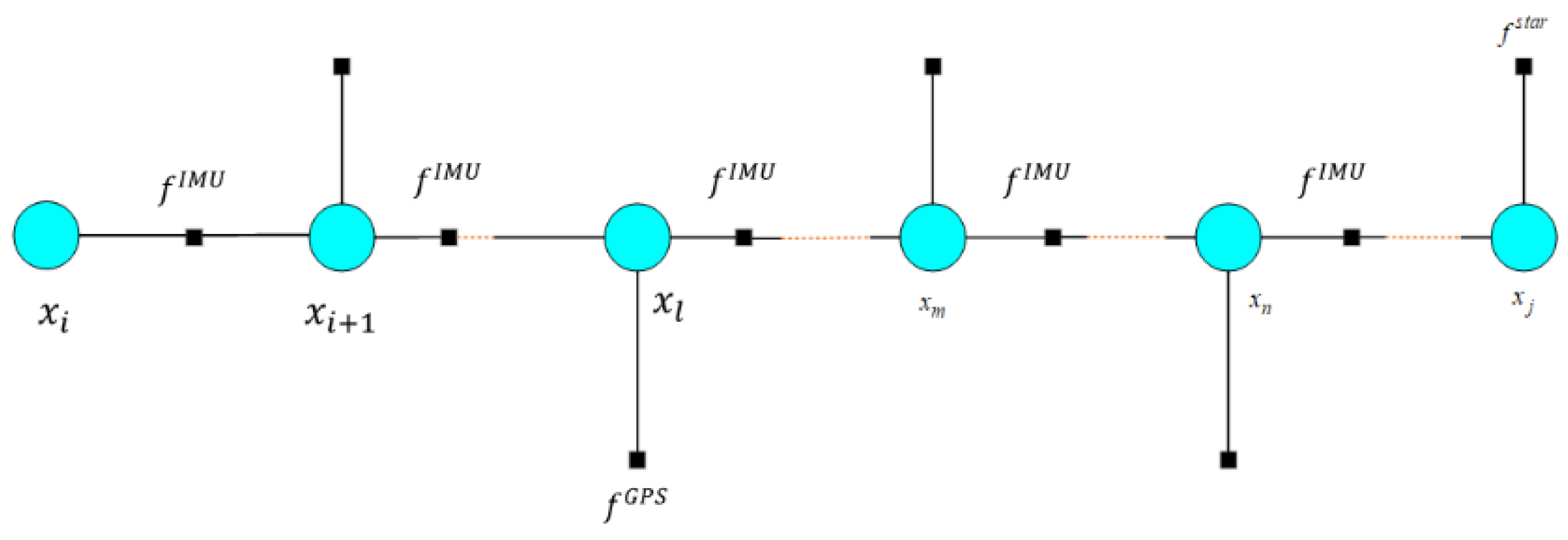

2.4. Factor Graph (FG) Methods

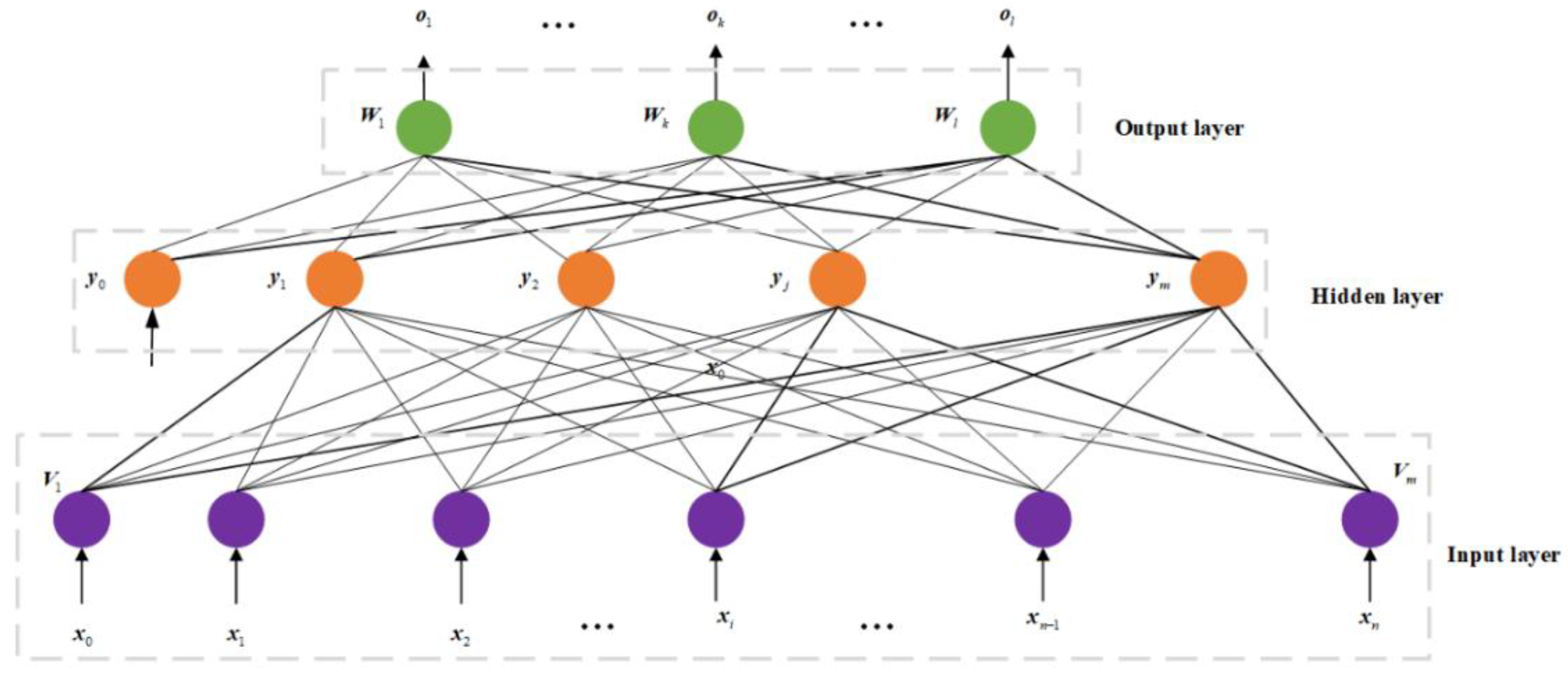

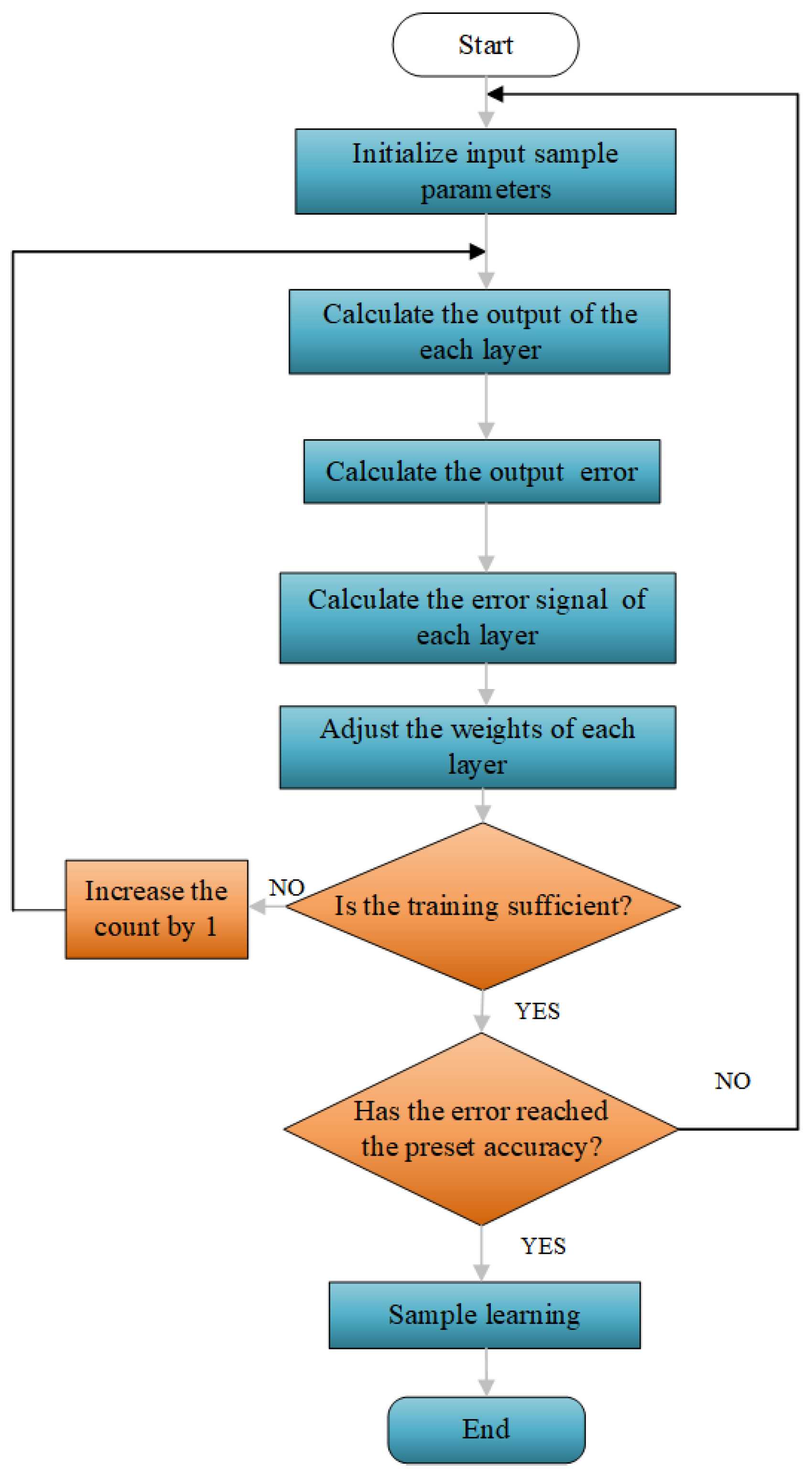

2.5. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Method

2.6. Methods Based on Uncertain Reasoning

3. Representative Applications of Partial Fusion Methodology in Navigation and Positioning

4. Summary of Features and Application Scenarios for Multi-Source Fusion Methods

5. Conclusions

6. Acknowledgment

References

- Ackerson G, Fu K. On-state estimation in switching environments. IEEE Trans. AC, 1970,15(1): 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Alsamhi, Saeed Hamood, et al. Survey on Federated Learning enabling indoor navigation for industry 4.0 in B5G. Future Generation Computer Systems, 2023,148: 250-265. [CrossRef]

- Andrieu C, Doucet A, Singh S, Tadic V. Particle methods for change detection, system identification and control. Proceedings of the IEEE, 2004, 92(3): 428-438. [CrossRef]

- Athans M, Wisher R, Bertolini A. Suboptimal state estimation algorithm for continuous-time nonlinear systems from discrete measurements. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 1968, AC-13(5): 504-515. [CrossRef]

- Bi X, HU S. Firefly Algorithm with high Precision Mixed Strategy optimized particle Filter. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University, 2019, 53(2): 232-238.

- Athans M, Wisher R, Bertolini A. Suboptimal state estimation algorithm for continuous-time nonlinear systems from discrete measurements. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 1968, AC-13(5): 504-515. [CrossRef]

- Bi X, HU S. Firefly Algorithm with high Precision Mixed Strategy optimized particle Filter. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University, 2019, 53(2): 232-238.

- Bian H, Jin Z, Tian W. Analysis of adaptive Kalman filter based on intelligent information fusion techniques in integrated navigation system. 2004(10): 1449-1452.

- Bierman G, Belzer M. A decentralized square root information filter/Smoother. Proc. NAECON, Dayton, OH, 1987. 1448-1456. [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi N, Asfihani T, Suhandri F, et al. Unscented Kalman filter for a low-cost GNSS/IMU-based mobile mapping application under demanding conditions. Geodesy and Geodynamics, 2024, 15(02): 166-176. [CrossRef]

- Carlson N A. Federated filter for fault-tolerant integrated navigation systems. Proc. Of IEEE PLANS 88, Orlando, FL 1988, 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Cao Z. Indoor and outdoor seamless positioning based on the Integration of GNSS/INS/UWB. Master's Thesis from Beijing Jiaotong University, 2021.

- Chen K, Chang G. & Chen C. GINav: a MATLAB-based software for the data processing and analysis of a GNSS/INS integrated navigation system. 2021, GPS Solut 25, 108. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Q, Liu H, Shen H, et al. A spatial and temporal nonlocal filter-based data fusion method. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2017, 55(8): 4476-4488. [CrossRef]

- Chi C, Zhang X, Liu J, Sun Y, Zhang Z, and Zhan X. GICI-LIB: A GNSS/INS/Camera Integrated Navigation Library. arXiv preprint, arXiv: 2306.13268. [CrossRef]

- Chiu H, Zhou X, Carlone L, et al. Constrained optimal selection for multi-sensor robot navigation using plug-and-play factor graphs. Proceedings of the IEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2014: 663-670. [CrossRef]

- Crisan D, Ducet A. A survey of convergence results on particle filtering methods for practitioners. IEEE Trans. on signal processing, 2002, 50 (3): 736-746. [CrossRef]

- Cui X, Yu Z, Tao B, et al. Generalized surveying adjustment. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press, 2001.

- Dan Simon. Optimal state estimation-Kalman, H∞ and nonlinear Approaches. John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- Dellaert F, Kaess M. Square root SAM: simultaneous localization and mapping via square root information smoothing. International Journal of Robotics Research,2006, 25(12): 1181-1203. [CrossRef]

- Doucet A, De Freitas N, Gordon N. Sequential Monte Carlo Methods in practice. Springer- Verlag, New York, 2001.

- Gao H, Li H, Huo H, et al. Robust GNSS real-time kinematic with ambiguity resolution in factor graph optimization//Proceedings of the 2022 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation. 2022: 835-843.

- Gao Z. Research on the methodology and application of the integration between the multi-constellation GNSS PPP and inertial navigation system. Wuhan University Doctoral Dissertation, 2016.

- Gray J, Muray W. A derivation of an analytical expression for the tracking index for the alpha-beta-gamma filtering. IEEE Trans. on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1993, 29(3): 1064-1065. [CrossRef]

- Indelman V, Williams S, Kaess M, et al. Factor graph-based incremental smoothing in inertial navigation systems. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Information Fusion, 2012:2154-2161.

- Isaard M, Blake A. Contour tracking by stochastic propagation of conditional density. European Conference on Computer Vision, 1996, 343-356.

- Jazwinski A. Stochastic processes and filtering theory. New York, Academic Press, 1970.

- Kerr T. Decentralized filtering and redundancy management for multisensor navigation. IEEE Trans. on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1987, AES-23(1): 83-119. [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa G. Monte Carlo filter and smother for non-Gaussian nonlinear state space models. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 1996, 5(1): 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Koch K. Least Squares Adjustment and Collocation. Bulletin Geodesique, 1977, 51(2). [CrossRef]

- Lange S, Sünderhauf N, Protzel P. Incremental smoothing vs. filtering for sensor fusion on an indoor UAV. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2013: 1773-1778. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hao S, Huang G. Modified strong tracking filter based on UD decomposition. Systems Engineering and Electronics, 2009, 31(8): 1953-1957.

- Li P, Xu X, Zhang X. Application of intelligent Kalman filter to underwater terrain integrated navigation system. Journal of Chinese Inertial Technology, 2011,19(5): 579-589.

- Li W, Li W, Cui X, et al. A tightly coupled RTK/INS algorithm with ambiguity resolution in the position domain for ground vehicles in harsh urban environments. Sensors, 2018, 18, 2160. [CrossRef]

- Li X. Hybrid estimation techniques in control and dynamic systems: Advances In Theory And Applications. New York: Academic Press, 1996, 76: 213-287.

- Li X, Li J, Wang A, et al. A review of integrated navigation technology based on visual/inertial/UWB fusion. Science of Surveying and Mapping, 2023, 48(6): 49-58.

- Li Y, Yang Y, He H. Effects analysis of constraints on GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation. Geomatics And Information Science of Wuhan University, 2017, 42(9): 1249-1255. [CrossRef]

- Liao J, Li X, Feng S. GVIL: Tightly-Coupled GNSS PPP/Visual/INS/LiDAR SLAM Based on Graph Optimization. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University, 2023, 48(7):1204-1215. [CrossRef]

- Liu F. Research on high-precision seamless positioning model and method based on multi-sensor fusion. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica, 2021, 50(12): 1780.

- Liu Y, Yu A, Zhu J, et al. Unscented Kalman filtering in the additive noise case. Sci China Tech Sci, 2010, 53: 929-941. [CrossRef]

- Loomis P, Carlson N, Berarducci M. Common Kalman filter: fault-tolerant navigation for next generation aircraft. Proc. Of the Inst. Of navigation Conf, Santa Barbara, CA, 1988, 38-45.

- Luan Z, Yu C, Gu B, Zhao X. A time-varying IMM fusion target tracking method. Radar and Navigation, 2021, 47(9): 111-116.

- MacCormick J, Blake A. A probabilistic exclusion principle for tracking multiple objects. International Conference on Computer Vision, 1999, 572-578. [CrossRef]

- Magill D. Optimal Adaptive estimation of sampled stochastic processes. IEEE Trans. AC, 1965,10(10): 434-439. [CrossRef]

- Mcclelland J, Rumelhart D, PDP research group. Parallel distributed processing. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987.

- Mehra R K. Approaches to adaptive filtering. IEEE Trans. On Automatic Control, 1972, AC-17(5): 693-698. [CrossRef]

- Moral P. Measure valued process and interacting particle systems: Application to non-linear filtering problems. Annals of Applied Probability, 1998, 8(2): 438-495.

- Pearson J. Dynamic decomposition techniques in optimization methods for large-scale system. McGraw-Hill, 1971.

- Shi C, Teng W, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Chen L, Chen R, Li Q. Autonomous Multi-Floor Localization Based on Smartphone-Integrated Sensors and Pedestrian Indoor Network. Remote Sensing. 2023, 15(11): 2933. [CrossRef]

- Speyer J L. Computation and transmission requirements for a decentralized linear-quadratic-Gaussian control problem. IEEE Trans. On Automatic Control, 1979, AC-24(2): 266-269. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Yan Y, Zhong Y, Li J, Meng Z. Data fusion method based on IMM-Kalman for an integrated navigation system. Journal of Harbin Engineering University, 2022, 43(7): 973-978.

- Vapnik V. An overview of statistical learning theory. IEEE transactions on neural networks, 1999, 10(5): 988-999. [CrossRef]

- Wang E, Pang T, Qu P, et al.GPS receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring Algorithm Based on Improved Particle Filter. Tele-communication Engineering, 2014, 54(4): 437-441.

- Wang E, Qu P, Pang T, et al. Receiver autonomous integrity monitoring based on particle swarm optimization particle filter. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2016, 42(12): 2572-2578. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Ling H, Jiang W, Cai B. Integrated Train Navigation system based on Full state fusion of Multi-constellation satellite positioning and inertial navigation. Journal of the China Railway Society, 2022, 44(11): 45-52.

- Wang X, Li X, Liao J, et al. Tightly coupled stereo visual-inertial-LiDAR SLAM based on graph optimization. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica, 2022, 51(8): 1744-1756.

- Watson R, Gross J. Robust navigation in GNSS degraded environment using graph optimization//Proceedings of the 30th international technical meeting of the satellite division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2017). 2017: 2906-2918.

- Wen W, Pfeifer T, Bai X, et al. It is time for Factor Graph Optimization for GNSS/INS Integration: Comparison between FGO and EKF. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2004.10572, 2020.

- Willsky A S, Bello M G, Castanon D A, Levy B C, Verghese G C. Combining and updating of local estimates and regional maps along sets of one-dimensional tracks. IEEE Trans. On Automatic Control, 1982, AC-27(4): 799-813. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Wang M, Wang Y, Wu Y. Multiple-mode self-calibration unscented Kalman filter method. Journal of Aerospace Power, 2024: 1-7.

- Yu H, Li Z, Wang J, Han H. Data fusion for GPS/INS tightly-coupled positioning system with equality and inequality constraints using an aggregate constraint unscented Kalman filter. Journal of Spatial Science, 2020, 65(3): 377-399. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Lu W, Zeng M, Zhao S. Low-cost agricultural machinery intelligent navigation method based on multi-sensor information fusion. China Measurement & Test, 2021, 47(12): 106-119.

- Yuan L, Zhang S, Wang J, et al. GNSS/INS integrated navigation aided by sky images in urban occlusion environment. Science of Surveying and Mapping, 2023, 48(9): 1-8.

- Yun L, Shu S, Gang H. A Weighted Measurement Fusion Particle Filter for Nonlinear Multisensory Systems Based on Gauss–Hermite Approximation. Sensors, 2017, 17(10): 2222. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Wang G, Chen Q, Tang H, Wang L, Niu X. Influence Analysis of IMU Scale Factor Error in GNSS/MEMS IMU vehicle integrated navigation. Journal of Geodesy and Geodynamics, 2024, 44(2): 134-137.

- Zhang X, Lu X. Recursive estimation of the stochastic model based on the Kalman filter formulation. GPS Solutions, 2021, 25(1): 24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhu F. Factor Graph Optimization for Urban Environment GNSS Positioning and Robust Performance Analysis. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University, 2023, 48(7): 1050-1057.

- Zhou Zhihua. Machine Learning. Tsinghua University Press, 2016.

- Zhu H, Wang F, Zhang W, et al. Real-Time Precise Positioning Method for Vehicle-Borne GNSS/MEMS IMU Integration in Urban Environment. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University, 2023, 48(7): 1232-1240. [CrossRef]

| Type | Estimation method | ||||

| LS | MLE | MAP | MVE | LMVE | |

| Estimation criterion | Formula(2) | Formula(4) | Formula(8) | Formula(12) | Formula(17) |

| Estimation formula | The first formula in formula (3) | The first formula in formula (7) | See formulas (10), (13) and (18) | ||

| Estimation error variance | The second formula in formula (3) | The second formula in formula (7) | |||

| Unbiasing | Unbiasedness | ||||

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| LSE | Simple and easy to use, no distribution assumptions, geometrically intuitive, and not dependent on the specific distribution of the data. | Sensitive to outliers, lacks statistical features, and is limited to linear models. |

| MLE | Gradual progression is beneficial, with strong versatility and clear statistical properties. | Computationally complex, sensitive to initial values, and dependent on distribution assumptions. |

| MAPE | Utilizing the prior distribution. Suitable for situations with small sample sizes or insufficient data and provides a complete posterior distribution for further analysis. | Relies on prior selection, with high computational complexity requiring integral computation. Sensitive to prior selection, where different prior choices may lead to distinct results. |

| MVE | The optimal unbiased estimator possesses well-defined statistical properties, achieves the minimum mean squared error among all estimators, and exhibits the best performance across all estimation methods. When both the estimated quantity and the measurements follow a normal distribution, the LMVE becomes equivalent to the MVE. | Dependent on model assumptions, computationally complex, and limited to unbiased estimation. Requires determining the conditional mean of measurements and estimated values under measurement conditions, which is computationally intensive. For non-stationary processes, it necessitates knowledge of first and second-order moments at each time instant, resulting in high computational demands. |

| LMVE | Best Linear Unbiased Estimator, simple to compute with clear statistical properties. | Limited to linear models. Dependent on model construction. Sensitive to outliers. |

| Method | Filter Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| KF | Centralized KF | (1) Low computational load and strong real-time performance. (2) it can provide optimal state estimation under linear Gaussian systems. (3) the algorithm is relatively simple and easy to implement. |

(1) It can only handle linear systems and is not capable of dealing with nonlinear systems. (2) it has strict requirements for noise distribution, which must be Gaussian. (3) it is sensitive to model errors, and inaccurate initial state estimation may lead to a slower convergence rate of the filter. |

| EKF | Centralized KF | (1) The EKF approximates the state and measurement equations of the real system by linearizing the nonlinear functions, retaining only the first-order terms and discarding the second-order and higher-order terms. (2) In systems with low nonlinearity, the EKF can maintain a high estimation accuracy. (3) Compared with other nonlinear filtering methods (such as the UKF), the EKF has a lower computational complexity and is more suitable for real-time applications. |

The EKF approximates the state and measurement equations of the real system by linearizing the nonlinear functions, thereby enabling it to handle nonlinear systems. In systems with low nonlinearity, the EKF can maintain a high estimation accuracy. Compared with other nonlinear filtering methods (such as the UKF), the EKF has a lower computational complexity and is more suitable for real-time applications. |

| UKF | Centralized KF | (1) It is capable of better handling non-Gaussian noise and nonlinear systems. (2) Compared to the EKF, it retains terms up to the second order in the linearization process, and it performs better in high-dimensional state spaces. |

(1) High computational complexity, as it requires the calculation of a large number of sigma points. (2) Sensitivity to noise, which may introduce additional noise. (3) Manual parameter tuning is required, such as the number and weights of sigma points. |

| PF | Centralized KF | (1) It can handle nonlinear systems and non-Gaussian noise. (2) There are no strict requirements for the noise distribution. (3) The algorithm can be computed in parallel, improving computational efficiency. |

(1) It has a large computational load, especially in high-dimensional state spaces. (2) The choice of particle number can affect the filtering performance, and particle degeneracy may occur |

| UPF | Centralized KF | (1) More accurate than particle filters, especially in high-dimensional state spaces. (2) It can effectively reduce the phenomenon of particle degeneracy. |

(1) Slightly higher computational load compared to particle filters. (2) Somewhat dependent on the choice of the UT. |

| FF | Decentralized KF | (1) It reduces the communication burden of centralized filtering and decreases the dependence on the central processor. (2) Compared with Decentralized filtering, it improves the estimation accuracy by adding some central coordination. |

(1) The implementation complexity is relatively high, and an effective information exchange mechanism needs to be designed. (2) There may be data imbalance issues that can affect the accuracy and stability of the model. |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| MME | (1) The MME method describes different states or behaviors of a system by combining multiple models, enabling more comprehensive coverage of complex system characteristics. (2) Through the integration of multiple models, the system can better address model errors, noise, and uncertainties. Even if one model deviates, others can still provide reliable estimates, thereby enhancing the overall robustness of the system. (3) MME dynamically adjust model weights or switch between models based on real-time data, allowing better adaptation to changes in system states. This adaptive capability makes them particularly effective in dynamic environments. |

(1) The MME method requires simultaneous computation and updating of multiple models, resulting in significantly higher computational complexity compared to single-model approaches. This may impose demanding requirements on computational resources for real-time applications. (2) The MME necessitates careful design and management of parameters, weights, and switching logic across multiple models. Coordinating and optimizing interactions between models constitutes a complex process requiring meticulous design and debugging. (3) Accurate parameter estimation for multiple models and effective model switching typically require substantial data support. In scenarios with data scarcity, the performance of multi-model methods may be constrained. |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| FG |

(1) High Flexibility: FG can more generally represent the decomposition of probability distributions and apply to a variety of complex probabilistic models. It can flexibly integrate data from different types of sensors (such as IMU, GPS, LiDAR, etc.) and introduce multiple constraints. (2) Effective Optimization: FG is suitable for large-scale sparse structure optimization and offers better numerical stability, especially in SLAM problems. It optimizes through Bayesian inference and can effectively handle multi-source heterogeneous data. (3) Strong Dynamic Adaptability: FG can dynamically adjust optimization strategies to adapt to dynamic changes in data, especially when dealing with inconsistent sensor information frequencies and dynamically changing validity. (4) Plug-and-Play: FG has a plug-and-play feature, allowing easy integration of new sensor data and strong scalability. |

(1) High computational complexity: FG has high computational complexity when dealing with large-scale data, which may limit its real-time applications. (2) High data preprocessing requirements: Multisource data usually needs to be preprocessed, such as data cleaning and normalization, to ensure the quality and consistency of the data. (3) Difficulty in model construction: Constructing an effective FG model requires a deep understanding of the uncertainty and correlation of the data, which increases the difficulty of model construction. (4) Real-time challenges: In some scenarios that require real-time decision-making, the computational complexity may limit its application. |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| AI |

(1) Strong Dynamic Adaptability: AI methods (such as machine learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning) can dynamically learn and adapt to environmental changes, automatically adjust fusion strategies, and overcome the limitations of traditional methods in handling nonlinearity, time-varying characteristics, and uncertainties. (2) Enhanced Capability in Handling Complex Data Relationships: Through model training, AI algorithms can process complex multi-source heterogeneous data relationships, improving fusion accuracy and system robustness. (3) Automatic Feature Extraction: Neural networks and similar algorithms can automatically learn data features, reducing the need for manual feature engineering, especially for large-scale, high-dimensional data. (4) Improved Decision-Making Efficiency: AI algorithms can rapidly integrate information from diverse sensors or data sources, providing support for real-time decision-making. |

(1) High computational costs: Multimodal data fusion models require processing information from multiple data streams, demanding significant computational resources (e.g., GPUs) and energy consumption, which may constrain real-time applications. (2) Demanding data preprocessing requirements: Multi-source data often exhibit discrepancies in formats, scales, semantics, and quality, necessitating preprocessing steps such as data cleaning and standardization, thereby increasing implementation complexity. (3) High model complexity: AI models (e.g., deep learning models) are typically intricate, requiring substantial time for training and optimization, while also demanding high data volume and quality. (4) Data privacy and security concerns: Data sources are diverse and may contain sensitive information, making privacy protection and security safeguarding critical challenges. |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Uncertainty reasoning |

(1) Strong capability in handling uncertainty: Uncertainty reasoning methods (such as Dempster-Shafer theory of evidence) can effectively deal with uncertainty in data, including imprecision, inconsistency of data, and sensor errors. (2) High flexibility: These methods can flexibly handle different types of data sources and meet the needs of fusing multi-source heterogeneous data. (3) Enhanced decision-making reliability: By properly dealing with uncertainty, the reliability of the fusion results can be improved, providing support for decision-making in complex environments. (4) Support for dynamic updates: In scenarios where data is constantly changing, uncertainty reasoning methods can dynamically adjust the fusion strategy to adapt to new data inputs. |

(1) High computational complexity: Uncertainty reasoning methods typically require complex computational processes, especially when dealing with large-scale data, resulting in high computational costs. (2) High requirements for data preprocessing: Multi-source data often needs to be preprocessed, such as data cleaning and normalization, to ensure the quality and consistency of the data. (3) Difficulty in model construction: Building effective uncertainty models requires a deep understanding of the uncertainty and correlation of the data, which increases the difficulty of model construction. (4) Real-time challenges: In scenarios that require real-time decision-making, the computational complexity may limit their application. |

| Type | Method | Main Characteristics | Applicable Scenarios |

| Optimal estimation | LSE, WLSE |

(1) Parameters are estimated by minimizing the sum of squared errors. (2) In linear regression models, the LSE is unbiased and achieves the minimum variance among all linear unbiased estimators (i.e., it is BLUE, the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator). (3) It is sensitive to outliers because its optimization relies on minimizing the sum of squared errors. (4) It is suitable for data with linear relationships, offering computational simplicity and ease of implementation. |

Linear regression and curve fitting. If the data distribution is unknown and the model is simple, it is preferable to prioritize LSE. |

| MLE | (1) Parameters are estimated by maximizing the likelihood function, relying solely on observed data without considering prior information. (2) For large sample sizes, MLE typically exhibits consistency (estimates converge to the true values as the sample size increases). (3) The computational complexity is low, and solutions can generally be obtained through analytical methods or numerical optimization. (4) MLE is asymptotically efficient when model assumptions hold but may fail when these assumptions are violated. |

Highly versatile and suitable for large samples, but computationally intensive. If the dataset is large and the distribution is known, MLE should be prioritized. | |

| MAPE | (1) Combines the likelihood of observed data with prior information about parameters, representing a Bayesian estimation method. (2) MAPE generally outperforms MLE when prior information is reliable and sample sizes are small. (3) MAPE Can be interpreted as a regularized version of MLE, where the prior distribution acts as a regularization term. (4) Computational complexity may be high, particularly with complex prior distributions or when numerical optimization is required. |

Combines prior information, suitable for small samples, but relies on prior selection. If the sample size is small and there is a need to incorporate prior information, the MAPE is chosen. | |

| MVE | (1) Among all unbiased estimators, it has the minimum variance, making it the optimal unbiased estimator. (2) It typically requires assumptions about the data distribution (e.g., normal distribution), and its optimality is guaranteed under these assumptions. (3) It exhibits higher computational complexity, particularly with high-dimensional data. |

In the case where the model is known and unbiased estimation is required, select either theMVE or the LMVE. | |

| LMVE | (1) It is the estimation method with the minimum variance among all linear estimators. (2) It only requires knowledge of the first and second-order moments of the estimated quantity and measured quantity, making it suitable for stationary processes. (3) For non-stationary processes, precise knowledge of the first and second-order moments at each time instant is required, which significantly constrains its applicability. (4) The computational complexity is moderate, but the estimation accuracy critically depends on the accuracy of the assumed moments |

||

| Filtering methods | KF |

(1) Linear System Assumption: The KF assumes both the system model and observation model are linear, with additive Gaussian noise. This linear-Gaussian assumption theoretically guarantees a globally optimal solution. (2) High Computational Efficiency: The KF exhibits low computational complexity (O(n²) for state dimension n), making it well-suited for real-time applications with stringent timing requirements. (3) Optimal Estimation Accuracy: Under strict adherence to linear-Gaussian assumptions, the KF provides statistically optimal estimates in the minimum mean-square error sense. (4) Limited Applicability: The KF's strict linearity assumptions lead to significant estimation errors when applied to nonlinear systems, severely constraining its practical application scope. |

It is suitable for scenarios where the system is linear and the noise follows a Gaussian distribution, such as in simple navigation and signal processing. |

| EKF |

(1) Nonlinear system processing: The EKF approximates nonlinear problems by linearizing the nonlinear system model. (2) Moderate computational complexity: The computational complexity of the EKF is higher than the KF but lower than the UKF. (3) Limited accuracy: Due to the linearization process, the EKF may experience larger estimation errors in strongly nonlinear systems. (4) Jacobian matrix calculation: The EKF requires computing the Jacobian matrices of the system model and observation model, which increases the algorithm complexity. (5) Broad applicability: The EKF is a widely used method for handling nonlinear systems and is suitable for moderate nonlinearity. |

It is suitable for scenarios where the nonlinearity is not high and fast real-time processing is required. Due to its lower computational complexity, the EKF is well-suited for use in embedded systems with limited computational resources. When the initial state estimation is relatively accurate, the EKF can converge quickly and provide better estimation results. |

|

| UKF | (1) Strong nonlinear system processing capability: The UKF selects a set of deterministic sampling points (Sigma points) through the UT, enabling a more accurate approximation of the statistical properties of nonlinear systems. (2) No Jacobian matrices required: The UKF avoids the complex Jacobian matrix calculations required in the EKF, enhancing the algorithm stability and precision. (3) Higher computational complexity: The computational complexity of the UKF is higher than that of the EKF, but it generally remains within acceptable limits. (4) High accuracy: The UKF outperforms the EKF in strongly nonlinear systems, providing more accurate estimation results. |

Suitable for scenarios involving nonlinear systems with Gaussian noise, such as complex target tracking and robotic navigation | |

| PF |

(1) Strong nonlinear and non-Gaussian adaptability: PF is a recursive Bayesian estimation technique based on Monte Carlo methods, capable of handling complex nonlinear systems and non-Gaussian noise environments. It approximates the posterior probability distribution through a large number of random samples (particles), thus avoiding the linearity and Gaussian assumptions required by traditional filtering methods (e.g., KF). (2) Flexibility and robustness: PF exhibits high flexibility, adapting to diverse systems and observation models. It demonstrates strong robustness against noise and outliers, making it particularly suitable for dynamic systems in complex environments. (3) Parallel computing capability: The computational process of PF can be parallelized, as the prediction and update operations for each particle are executed independently, significantly improving computational efficiency. (4) Handling complex probability distributions: PF can manage multimodal probability distributions, making it ideal for state estimation in complex scenarios. Through its particle weight updating mechanism, it effectively integrates information from multiple sensors. (5) Challenges and optimizations: Despite its adaptability, PF faces challenges such as particle degeneracy and high computational complexity. To address these issues, researchers have proposed improvements like adaptive PF, combining the UKF to generate proposal distributions, and optimizing resampling strategies. |

Suitable for nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems, such as target tracking, robotic navigation, and signal processing. |

|

| UPF |

(1) Adaptability to non-Gaussian noise: When combined with PF, the UKF further enhances its adaptability to non-Gaussian and multimodal probability distributions. (2) Balanced computational efficiency and accuracy: The UKF achieves a good balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. While its computational complexity is higher than that of the traditional KF, the UKF outperforms the EKF in handling high-dimensional state spaces and has lower computational complexity compared to PF. By integrating PF, particles are generated and updated via the UT, further improving particle effectiveness and sampling efficiency. (3) Mitigation of particle degeneracy: In PF, particle degeneracy—a common issue where most particle weights approach zero, reducing the number of effective particles—is alleviated when combined with the UKF. Sigma points generated through the UT provide a more accurate description of the state distribution, thereby reducing particle degeneracy. (4) Further optimization via PF integration: The UPF combines the strengths of the UKF and PF. By generating and updating particles through the UKF UT, UPF retains PF strong adaptability to nonlinear and non-Gaussian problems while improving sampling efficiency. |

Suitable for nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems where high estimation accuracy is required. | |

| FF |

(1) Distributed Structure and Flexibility: FF adopts a distributed architecture, decomposing data fusion tasks into multiple sub-filters and a master filter. This structural design offers flexibility, allowing the selection of appropriate filtering algorithms (e.g., EKF, UKF) based on the characteristics of different sensors. It also supports dynamic adaptation to sensors joining or leaving the network. (2) Fault Tolerance and Fault Isolation Capability: FF can detect and isolate faulty sensors in real time, preventing erroneous data from degrading global estimation accuracy. This ensures high precision and reliability even when partial sensor failures occur. (3) Diversity of Information Allocation Strategies: FF supports multiple information allocation strategies, including zero-reset mode, variable proportion mode, feedback-free mode, and fusion-feedback mode. These strategies exhibit trade-offs in computational complexity, fusion accuracy, and fault tolerance, enabling flexible selection tailored to specific application scenarios. (4) High Computational Efficiency: By distributing data processing among multiple sub-filters, each of which handles only local data, FF reduces the computational load. This distributed computing approach not only enhances the system real-time performance but also lowers the demand for hardware resources. (5) Adaptive and Dynamic Adjustment Capability: Integrated with adaptive filtering theory, FF dynamically adjusts information allocation coefficients based on sensor performance and environmental changes. (6) Plug-and-Play Functionality: FF supports plug-and-play operation for sensors, enabling rapid adaptation to dynamic sensor addition or removal. This feature enhances flexibility and adaptability in complex environments or evolving mission requirements. (7) Globally Optimal Estimation: The master filter synthesizes local estimates from sub-filters to achieve a globally optimal estimate. This two-tier architecture preserves local filtering precision while improving overall system performance through global fusion. (8) Suitability for Complex Environments: FF excels in multi-source heterogeneous data fusion scenarios, such as integrating satellite navigation, inertial navigation, and visual navigation in navigation systems. It effectively addresses sensor noise, model biases, and environmental interference challenges. |

Suitable for multi-sensor networks, especially in scenarios where sensors are widely distributed and communication resources are limited. | |

| MME |

(1) Multimodal Data Processing Capability: MME methods can handle data from different modalities, such as images, text, audio, and video. By mapping multimodal data into a unified feature space or integrating information through fusion techniques, these methods leverage the complementary nature of different modalities to enhance model performance. (2) Diversity of Fusion Strategies: MME methods support various fusion strategies, including early fusion (integration at the data level), mid-level fusion (integration at the feature level), late fusion (integration at the decision level), and hybrid fusion (combining multiple strategies). Different strategies are suited to different application scenarios, enabling flexible adaptation to complex data fusion requirements. (3) Enhanced Model Robustness: By incorporating multimodal data and multi-model estimation, uncertainties arising from single-modality data can be effectively reduced, improving the model's robustness against noise and outliers. (4) Improved Performance and Generalization Capability: MME methods comprehensively capture target information by fusing multimodal data, thereby boosting both model performance and generalization ability. (5) Flexibility in Model Architecture: MME methods typically offer high flexibility, allowing the selection of appropriate model architectures based on specific task requirements. For example, unified embedding-decoder architectures and cross-modal attention architectures can be combined to fully exploit the advantages of different structural designs. |

(1) In scenarios such as multi-object tracking and complex trajectory prediction, multi-model estimation methods can effectively deal with the various motion patterns and uncertainties of targets. (2)Suitable for integrated navigation systems, such as the fusion of inertial navigation and satellite navigation, multi-model estimation can improve positioning accuracy and reliability. (3) In complex industrial scenarios such as power systems and chemical processes, MME methods can be used for modeling and control to address the dynamic changes in system parameters. |

|

| FG | (1) Intuitiveness and Flexibility: FG visually represents the relationships between variables and factors, making complex probabilistic models more intuitive and easier to understand. Compared to Bayesian networks, FG can more generally express the decomposition of probability distributions, making them suitable for a wide range of complex probabilistic models. (2) Efficient Inference and Optimization Capabilities: FGs excel in algorithms such as variable elimination and message passing, significantly improving inference efficiency. By jointly optimizing the relationships between data from different sensors, FG can efficiently fuse multi-sensor data. (3) Strong Multi-Source Data Fusion Capability: FG can effectively integrate data from various sensors (such as cameras, radars, and IMUs). By constructing an FG model, they can jointly optimize heterogeneous multi-source data, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of data fusion. (4) Support for Dynamic Data Processing: FG algorithms support techniques such as sliding-window optimization (Sliding-Window FGO), enabling dynamic processing of real-time data streams. This makes them suitable for scenarios with high computational complexity and stringent real-time requirements. (5) Robustness and Outlier Resistance: In complex environments (such as urban canyons), FGO demonstrates better robustness and positioning accuracy compared to traditional methods like the EKF. |

(1) Autonomous Driving and Robot Navigation: FG methods are widely used in autonomous driving and robot navigation to integrate data from multiple sources such as cameras, radar, LiDAR, and IMU, thereby enhancing the accuracy of localization and mapping. (2) Underwater Robot Localization: In complex underwater environments, FG methods can effectively handle abnormal sensor observations, thereby improving the positioning accuracy of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. (3) Industrial Fault Detection and Diagnosis: FG methods can be used to integrate monitoring data from different sensors to achieve early warning and diagnosis of equipment faults. (4) Medical Diagnosis: In the medical field, FG methods can integrate patients' medical records, imaging data, and laboratory test results to improve the accuracy of disease diagnosis. (5) Environmental Monitoring: FG methods can integrate data from satellites, ground sensors, and meteorological data to monitor environmental changes in real time, supporting environmental management and decision-making. |

|

| AI | (1) Heterogeneous Data Processing Capability: The AI method can handle data from diverse sources, formats, and structures (such as text, images, and sensor data) through multimodal models (e.g., Transformers, hybrid neural networks) to achieve unified processing. (2) Automatic Feature Extraction and Representation Learning: Deep learning models (e.g., autoencoders, BERT) autonomously learn high-level abstract features without manual feature engineering, adapting to the complexity of multi-source data. This reduces reliance on domain-specific knowledge while improving feature expression efficiency and generalization. (3) Robustness and Fault Tolerance: AI maintains stability amid data noise, missing values, or conflicts by leveraging adversarial training, data augmentation, and attention mechanisms to filter redundant information. (4) Additional capabilities include cross-modal association and reasoning, real-time performance and scalability, and adaptability and dynamic updating. |

(1)Autonomous Driving: Integrating data from cameras, radar, and LiDAR helps vehicles understand their surroundings from multiple perspectives, enabling safe navigation. (2)Medical Diagnosis: Fusing patient medical records with medical imaging data allows for the rapid and accurate identification of diseases, thereby improving diagnostic efficiency. (3) Smart Cities: In real estate management, combining sensor data, social media feedback, and Geographic Information System (GIS) data optimizes urban spatial layout and resource allocation. (4)Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT): Analyzing sensor data enables predictive maintenance and optimization of equipment, thereby increasing production efficiency. (5) Environmental Monitoring: Integrating satellite data, ground sensor data, and meteorological data allows for real-time monitoring of environmental changes, supporting environmental management and decision-making. |

|

| Uncertain reasoning |

(1) Strong capability in handling uncertainty: Uncertainty reasoning methods can effectively deal with uncertainty in data, including imprecision, inconsistency, and sensor errors. For example, Dempster-Shafer theory of evidence can model and fuse uncertain information, while Bayesian methods handle uncertainty through probabilistic updates. (2) High flexibility: Uncertainty reasoning methods can flexibly handle different types of data sources and meet the needs of fusing multi-source heterogeneous data. They are capable of integrating symbolic reasoning and numerical reasoning to process various types of information, ranging from qualitative to quantitative. (3) Enhanced decision-making reliability: By properly handling uncertainty, uncertainty reasoning methods can improve the reliability of the fusion results and provide support for decision-making in complex environments. (4) High computational complexity, high requirements for data preprocessing, difficulty in model construction, and challenges in real-time performance. |

(1) Target Recognition and Tracking in Complex Environments: In target recognition and tracking tasks, uncertainty reasoning methods can effectively handle uncertain data from multiple sensors (such as cameras and radars), thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of target detection. (2) Medical Diagnosis: In the medical field, by integrating patients' medical records, imaging data, and laboratory test results, uncertainty reasoning methods can more accurately identify diseases and enhance the accuracy of diagnosis. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).