1. Introduction

The feminism movement has profoundly changed the world, and commercial advertisements also play an important role in it [

1,

2]. In the era of e-commerce, brands are shifting from product centered marketing strategies towards consumer centered marketing strategies, and femvertising is one of the most popular tactics [

3,

4]. Femvertising, as an emerging form of advertising, aims to empower women by revealing the difficulties faced by women, challenging traditional gender stereotypes, and advocating for women’s rights [

5,

6]. Brands wish to improve their brand image and promote sales performance through femvertising. As feminism is a hot topic of public concern, especially on social medias, femvertising is highly likely to spark widespread discussion and attract large amount of attention. It has been found by many studies that femvertising enhance brand awareness, social reputation, consumer loyalty and ultimately purchase intention towards the brand [

7,

8,

9]. However, it is also questioned as femwashing, which use feminism as a commercial tool to trap consumers, lacking in-depth exploration of substantive issues of women’s empowerment [

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, it is crucial for brands to carefully assess consumers’ potential attitudes and reactions before using femvertising, to avoid being criticized or boycotted.

Previous studies on femvertising are mostly focused on female consumers [

13,

14], while the perceptions, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors of male consumers are usually neglected [

15,

16]. Internet advertisements are usually public to everyone, even if they are not targeting consumers of both genders. Different from female consumers, male consumers’ attitude towards femvertising is more complicated and influenced by various factors such as gender identity, social expectations, and personal emotions [

17]. They may even view femvertising as an attack on men, leading to a defensive mentality [

15]. Even if the products in the advertisement are not meant for men, they may also make negative comments online and even engage in heated debates with women. These online disputes are widely spread and may damage the brand’s social image and reputation. Besides, a large portion of fashion products designed for women are also purchased by male consumers as gifts to women. Therefore, male consumers are never bystanders or outsiders in the field of femvertising [

16,

18]. Exploring the unique perceptions and socio-cultural contexts of male consumers is of great significance, while neglecting male consumers’ reactions hinders the effectiveness of femvertising and exacerbates conflicts between men and women.

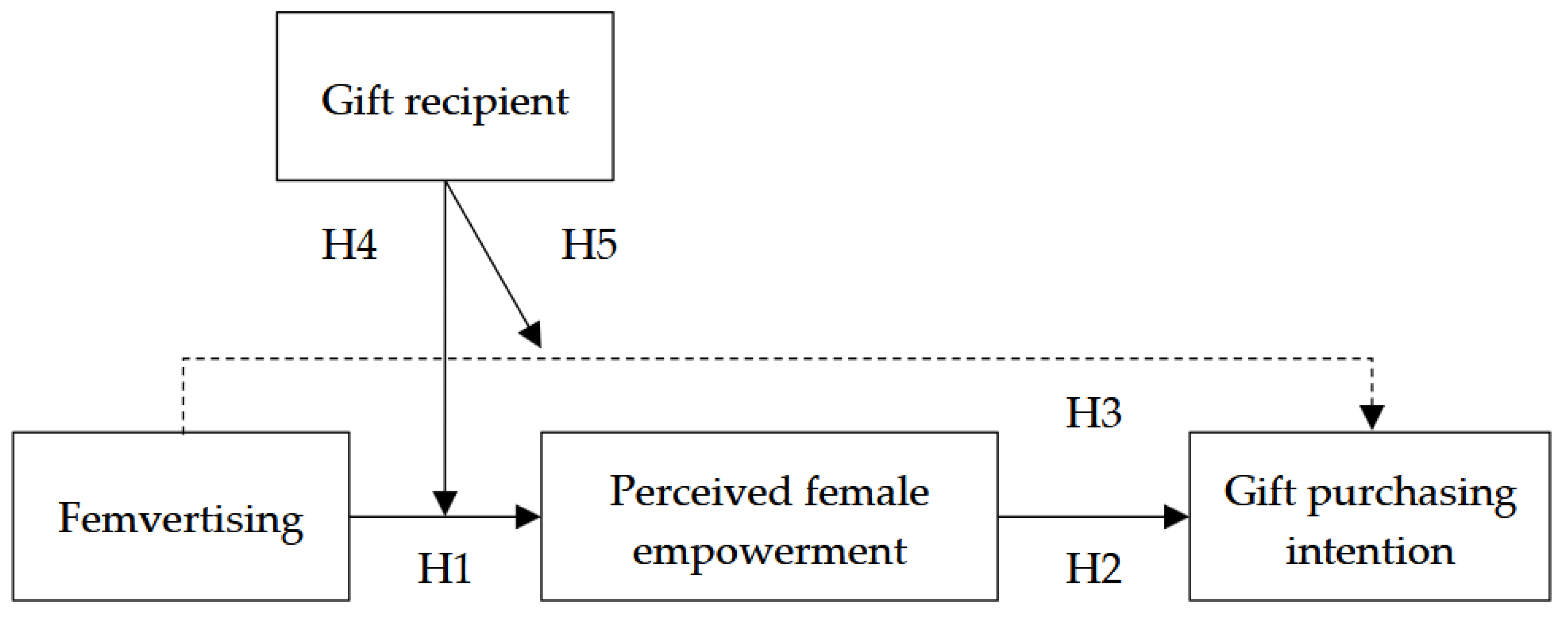

This study focused on the context of men purchasing women’s clothing as gifts on line, and explored the impact of femvertising on male consumers' gift purchasing intention. It also examined the mediating role of male consumers’ perceived female empowerment and the moderating role of gift recipient. It contributes to the theory in the following three aspects. First, it has demonstrated the positive mediating effect of perceived female empowerment in the relationship between femvertising and male consumers' gift purchasing intention, and provided a new theoretical perspective for a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of femvertising. Second, it has also found the moderating effect of gift recipient, and helped to clarify the contextual differences in the consequences of femvertising. Third, it has conducted a situational experiment to strengthen the causality in the conclusions, and might inspire experimental designs in future studies. By exploring the impact of femvertising on male consumers, this study wishes to inspire brands to better use femvertising to promote their brand image and sales performance. It also wishes to guide male consumers to participate more actively in gender equality movements, eliminate gender bias, cultivate social respect for individual autonomy, and promote social harmony on the Internet.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Femvertising on Perceived Female Empowerment

Brands are now increasingly using online advertisements to articulate their attitudes on social issues, especially gender equality [

2,

16]. Advertisements convey not only specific information such as brand names and product features, but also abstract information such as the brand’s values and missions. Femvertising is a type of advertising that breaks traditional gender stereotypes and aims to empower women through positive and inclusive communication [

3,

19]. There are various ways of femvertising. In addition to directly advocating for women rights, brands can showcase diverse, including imperfect, female images in their advertisements and encourages women to accept their true selves [

20,

21,

22]. For example, Dove’s “Real Beauty Campaign” challenges traditional body standards by showcasing women of different ages, body types, and races. Brands also resonates with consumers by depicting the challenges and difficulties faced by women, prompting audiences, including male audiences, to think from a female perspective [

23,

24]. For example, Procter & Gamble’s “Like a Girl” advertisement reflects on gender stereotypes by showcasing the stigmatization of behaviors such as running and fighting of girls. Brands can also depict confident and independent women participating in activities that are considered male privilege, setting positive examples, encouraging women to pursue their dreams, and supporting each other [

3,

25]. For example, Nike's "Dream Crazier" advertisement inspires women to be brave and independent by showcasing stories of female athletes overcoming difficulties and pursuing their dreams. In doing so, brands can break the stereotypes of gender norms and encourage women/girls to achieve self-acceptance, self-respect, self-actualization, and self-empowerment.

Feminist empowerment is the idea of inspiring women to control and take responsibility for their own identity and choices [

26]. It concerns not only high access to resources, but also strong mentality to pursue their goals [

27]. Individuals with low psychological empowerment may fail due to a lack of goals, self-efficacy, and motivation [

28]. Because of the gender inequality and stereotypes, many women are not brave enough to be independent and pursue a successful career. Some of them are even dissatisfied with their own body and become depress when others criticize about their appearances and weights. Femvertising links female empowerment with their products, transforming feminism into brand behaviors [

2,

29]. It tells women that they can achieve everything and anything if they set their mind to, by showcasing successful examples in advertisements. Although male consumers are more likely to be skeptical of femvertising, they respond positively to brands they believe truly support gender equality [

16]. When femvertising advertisements showcase the positive social impact of gender equality, men may be more inclined to view supporting gender equality as a way to promote social progress [

15,

16]. They will also realize the gender inequality issues by seeing the challenges and difficulties faced by women [

24,

30,

31], and start to reflect on their potential gender biases and gain a better understanding of female empowerment and support it. They will also see what women can achieve when given the opportunity, and believe in the potential of liberating women [

25]. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed.

H1. Femvertising (versus traditional advertising) has a positive impact on male consumers’ perceived female empowerment.

2.2. The Impact of Perceived Female Empowerment on Gift Purchasing Intention

It has been found by many studies that perceived female empowerment stimulates positive emotional feedbacks from female audiences and strengthen the psychological bond with their consumers [

32,

33,

34]. Furthermore, exposure to empowering media promotes self-efficacy, and encourages female to take actions to achieve their goals [

35,

36]. Besides, general felt empowerment is also beneficial to female’s subjective well-being [

27]. However, it is still unclear how male consumers will respond to perceived female empowerment.

Interpersonal relationships are essential and gifts are often given to cultivate these relationships, especially in China, where individual interactions are influenced by unique local culture such as “guanxi”, “face”, and “favors” [

37]. Gift giving has significant social, well-being, and economic consequences [

38], while inappropriate gifts can lead to negative outcomes [

39,

40]. Choosing gifts is subjected to various factors, including the givers’ motives, receivers’ preferences, and social norms [

41]. Gifts not only provides functional values for the receivers, but also carry the intention of the givers to showcase their own values, strengthen social connections, and promote interpersonal relationships [

39]. In comparison, inappropriate gifts may embarrass the receiver, create identity threat, and even damage the relationships [

40,

42]. Many gift givers are extremely cautious and even anxious when choosing a gift, let along that men are usually not very familiar with fashion products for female [

38]. They are more concerned with the symbolic meaning of the brand rather than the functionality and cost-effectiveness of the products. Supporting female empowerment may be viewed as a symbol of progressive social identity, and male consumers can embellish their image by endorsing femvertising. They wish that giving the gift will help them gain face or make the relationship closer [

43]. For male consumers who sincerely endorse feminism, perceived female empowerment is likely to promote favorable attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand [

33,

44]. For those who are not so passionate about feminism, choosing a gift that empowers women also helps them convey a good impression, as well as serve as an opportunity to better express respect and care for the female receiver. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed.

H2. Perceived female empowerment has a positive impact on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

Considering femvertising facilitates perceived female empowerment and perceived female empowerment promotes male consumers’ gift purchasing intention, it is reasonable to propose that there is a positive mediating effect of perceived female empowerment in the relationship between femvertising and gift purchasing intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed.

H3. Through the mediating effect of perceived female empowerment, femvertising (versus traditional advertising) has a positive impact on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Gift Recipients

Gift choices are not only affected by characteristics of the gifts and occasions, but also by the nature of relationship between the giver and the receiver [

45,

46]. Two types of relationship have been identified, namely communal relationship and exchange relationship [

47,

48]. In communal relationships, people look after each other’s needs and show genuine concern for each other’s welfare [

49,

50]. Such relationships are usually built on long-term interactions and deep emotional connections. In exchange relationships, people emphasize more on the equivalence of paying and receiving instead of each other’s welfare [

49,

50]. Such relationships are usually established on cooperation in work and common interests. People in a communal relationship are usually more intimate than people in an exchange relationship [

37]. When selecting gifts, givers adjust their focus based on the closeness of their relationship with the recipient [

37,

51](Morgan et al., 2011). The closer the relationship, the more the giver values the experiential benefits; the more distant the relationship, the more the gift giver values the functional benefits [

52]. Femvertising provides rich experiential benefits through emotional resonance, uniqueness, self-identity, and social influence [

1,

8]. When consumers are picking a gift for someone in a communal relationship, they concern more about the recipients’ personal growth and control over their identity [

25,

39,

48]. In this case, male consumers may be more positive towards femvertising and perceive stronger female empowerment [

16,

26]. In contrast, when consumers are picking a gift for someone in an exchange relationship, they concern more about whether the value of the gift can be recognized and repaid in a comparable manner [

47]. Givers may rely more on superficial cues, such as product functionality and price, overlooking the deeper messages of female empowerment conveyed in the advertisements. In this case, male consumers may emphasize more on the functionality of the gift and prefer traditional advertisements focusing on the product. Therefore, the following two hypotheses were proposed.

Hypothesis H4: When the gift recipient is in a communal relationship (versus exchange relationship), the impact of femvertising on perceived female empowerment is stronger.

Hypothesis H5: When the gift recipient is in a communal relationship (versus exchange relationship), the mediating effect of perceived female empowerment between femvertising and gift purchasing intention is stronger.

The theoretical framework and hypotheses are shown in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Materials

A situational experiment was conducted in China to acquire data for testing the hypotheses. Femvertising and gift recipient were manipulated in the materials with images and texts. In addition, two sets of clothes were used to enrich the diversity of materials. Therefore, following the idea of orthogonal experiment, 8 sets of experimental materials were designed: 2 (traditional advertising vs. femvertising) × 2 (exchange relationship vs. communal relationship) × 2 (clothing A vs. clothing B). The materials were coded with 3 digits: traditional advertising was coded as 0, femvertising was coded as 1; exchange relationship was coded as 0, communal relationship was coded as 1; clothing A was coded as 0, clothing B was coded as 1. Advertisement was manipulated with the text that traditional advertising emphasized on product features while femvertising emphasized on social norms of female. Gift recipient was manipulated by asking the participants to think of a female friend of certain kind and answer the questionnaire accordingly. The experimental materials are displayed in

Table 1.

3.2. Measurement Scales

Apart from the variables manipulated by experimental materials, the mediating variable and the dependent variable were measured with Linkert scales ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree.

Perceived female empowerment. Perceived female empowerment was measured with the scale from Teng et al. [

17]. The three items are: “Women in the advertisement are powerful”, “Women in advertising are independent”, and “Women in advertising have a lot of control”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.64.

Gift purchasing intention. Gift purchasing intention was measured with a scale adapted from Barta et al. [

53]. The three items are: “I am very likely to purchase the clothing as a gift”, “I intend to purchase the clothing as a gift”, and “I will purchase the clothing as a gift”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Control variables. Age, education, income, and clothing were chosen as control variables to control their interferences to the results.

3.3. Participants and Procedure

A total of 364 participants were recruited and assigned to the 8 experimental groups randomly. The participants read the experimental materials and answered the questionnaire independently. After deleting 38 unqualified samples (those with most items rated at the same scores or rated in a clear pattern), 326 valid samples were obtained (effective response rate was 89.6%). The demographic descriptions of the samples are reported in

Table 2. Most of the samples aged from 18 to 25 (50.3%), had a bachelor degree (84.7%), and had a monthly income between ¥5001-10000 (44.5%). Besides, based on the sample distribution of the 8 experimental groups, the sample sizes of traditional advertising and femvertising were 161 and 165, the sample sizes of exchange relationship and communal relationship were 156 and 170, the sample sizes of clothing A and clothing B were 160 and 166, which were relatively even and acceptable.

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

The results of correlation analysis are reported in

Table 3. Among them, femvertising positively correlated with perceived female empowerment (r = 0.358, p < 0.01), and perceived female empowerment positively correlated with gift purchasing intention (r = 0.429, p < 0.01), while femvertising was not significantly correlated with gift purchasing intention (r = 0.011, p > 0.05).

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses were tested with regression analysis and bootstrapping method using the PROCESS v4.3 in SPSS 26.0. The bootstrapping sample size was set as 5000 to calculated the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The results were summarized in

Table 4,

Table 5, and

Table 6.

As reported in

Table 4, femvertising positively affects perceived female empowerment (Model 1, b = 0.449, p<0.001), which supported hypothesis H1. Further, perceived female empowerment positively affects gift purchasing intention (Model 4, b = 0.639, p<0.001), which supported hypothesis H2.

As reported in

Table 5, the indirect effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention through perceived female empowerment was significant (b = 0.286, 95% CI [0.185, 0.405] excluded zero), which supported hypothesis H3. However, the total effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention was not significant (b = 0.018, 95% CI [-0.171, 0.206] included zero), while the direct effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention was significant and negative (b = -0.269, 95% CI [-0.447, -0.091] excluded zero). These results indicated that there may be another unknown negative mediating mechanism in the relationship between femvertising and gift purchasing intention.

As reported in

Table 6, when the gift recipient was in an exchange relationship, the effect of femvertising on perceived female empowerment was 0.250. When the gift recipient was in a communal relationship, the effect of femvertising on perceived female empowerment was 0.650. The intergroup difference was 0.400, and the 95% CI [0.131, 0.668] excluded zero. Therefore, the intergroup difference was significant and hypothesis H4 was supported. When the gift recipient was in an exchange relationship, the mediating effect of perceived female empowerment was 0.158. When the gift recipient was in a communal relationship, the mediating effect of perceived female empowerment was 0.411. The intergroup difference was 0.253, and the 95% CI [0.072, 0.464] excluded zero. Therefore, the intergroup difference was significant and hypothesis H5 was also supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study aimed to explore the impact and mechanism of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention. The results demonstrated that femvertising has a positive impact on male consumers' perceived female empowerment, and perceived female empowerment has a positive impact on their gift purchasing intention. Through the mediating effect of perceived female empowerment, femvertising promotes male consumers’ gift purchasing intention. In addition, the mediating effect is stronger when the gift recipient is in a communal relationship (versus exchange relationship). However, the total effect of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention is not significant, which indicated that there might be another negative mediating mechanism in it. Men are in an advantageous position in gender relations and are more inclined to stick to traditional gender norms, and even view femvertising as an attract on men [

15]. They may criticize that femvertising is just vague claims, lacking in-depth exploration of substantive issues that promote actual women development [

14,

17]. Although they recognize the empowerment of women in femvertising, the other negative perception may hinder them from purchasing the brand.

This study has made three theoretical contributions. First, previous studies mainly focused on the impact of femvertising on female consumers [

15,

16], while this study explored the perceptions and responses of male consumers, and demonstrated the positive mediating effect of perceived female empowerment, which provided a new theoretical perspective for a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of femvertising. Second, previous studies are mostly limited to the context of women’s self-shopping [

10,

13], while this study extend to the context to men purchasing women’s clothing as gifts, which may help to expand the scope of the theories on femvertising. Besides, this study has demonstrated the moderating effect of gift recipients, which helps to clarify the contextual differences in the impact of femvertising. Third, previous studies mostly relied on qualitative and inductive methods to analyze the impact of femvertising [

31], with only a few studies using quantitative methods such as questionnaire survey [

5,

28], while this study has conducted a situational experiment to test the hypotheses. It may strengthen the causality of conclusions and made a methodological contribution in inspiring future studies in designing their own situational experiments.

5.2. Practical Implications

Several practical inspirations can be derived from these findings. First, brands should actively explore femvertising, depicting women in an equal, independent, strong, and diverse way to convey female empowerment. Second, femvertising should stimulate a better dialogue between man and women, instead of triggering fierce criticism and resistance from male consumers. Brands should adhere to the concept of gender equality rather than being too radical or biased. They should also carefully evaluate the potential responses of the public, including male and female, before releasing the femvertising advertisements. Third, brands can contingently choose femvertising or not, based on their products and targeted market. For example, femvertising is more effective for products that are meant for gift recipients of communal relationships, and products specially designed for certain festivals such as Valentine’s Day or Mother’s Day.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

There are still some limitations in the methodology. First, in the situational experiment, only the submachine jacket was used as the advertising product, without covering other clothing categories or more diverse gifts, which limited the generalizability of the conclusions. Second, in the advertising copies of femvertising, only individual autonomy was involved, without considering other feminism issues, which may not fully represent the effectiveness of femvertising. Third, only Chinese male consumers were surveyed, and the sample is relatively young and has a high level of education, which may not represent male consumers of other age groups, socio-economic status, and nationalities.

It has also inspired some further research directions. First, this study has found a positive mediating effect of perceived female empowerment, but the overall effect of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention was not significant, indicating that there may be another negative mediating mechanism. Further explore on the reasons that hinder male consumers’ gift purchasing intention will provide a more comprehensive understanding on femvertising. Second, there are tremendous differences in gender attitudes in different countries and ethnic groups. This study only investigated male consumers in China, further studies on the perception and reactions of male consumers in other cultural backgrounds will be beneficial to deepen our understanding of the effectiveness of femvertising. Third, femvertising research can be extended to other gender-neutral industries such as automotive, electronics, and food. It will help to clarify the theoretical boundaries of femvertising theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., Z.X. and D.Q.; methodology, Z.X.; software, S.Y.; validation, S.Y.; formal analysis, S.Y. and Z.X.; investigation, S.Y.; resources, Z.X. and D.Q.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.X.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, Z.X. and D.Q.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and D.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Project of Zhejiang Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences (2023N022), Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Hangzhou (Z23JC064), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72101233), and Fundamental Research Funds of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (24196121-Y).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since the situational experiment was anonymous and does not involve personal privacy or commercial interests, according to “Ethical Review Methods for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans” issued by the People’s Republic of China in February 2023, specifically Article 32 of Chapter 3, regarding the exemption from ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adalı, G.; Yardibi, F.; Aydın, Ş.; Güdekli, A.; Aksoy, E.; Hoştut, S. Gender and Advertising: A 50-Year Bibliometric Analysis. J. Advert. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Borquez, C. L.; Török, A.; Centeno-Velázquez, E.; Malota, E. Female stereotypes and female empowerment in advertising: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, W. The impact of advertising on women’s self-perception: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1430079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Koo, J.; Kim, D. Y. Femvertising of luxury brands: Message concreteness, authenticity, and involvement. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2023, 14, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Jamil, M.; AL-Hazmi, N. M.; Amir, A. Unveiling femvertising: examining gratitude, consumers attitude towards femvertising and personality traits. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2297448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windels, K.; Champlin, S.; Shelton, S.; Sterbenk, Y.; Poteet, M. Selling feminism: How female empowerment campaigns employ postfeminist discourses. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, A.; Sternadori, M. Championing women’s empowerment as a catalyst for purchase intentions: Testing the mediating roles of OPRs and brand loyalty in the context of femvertising. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2019, 13, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A. Mapping Femvertising Research: A PRISMA Driven Systematic Review of Literature. Bull. Bus. Econ. 2024, 13, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiw, S. A.; Phillips, B. J.; Williams, D. E. Luxury brands’ use of CSR and femvertising: the case of jewelry advertising. Qual. Mark. Res. 2021, 24, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainneville, V.; Guèvremont, A.; Robinot, É. Femvertising or femwashing? Women's perceptions of authenticity. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobande, F. Femvertising and fast fashion: Feminist advertising or fauxminist marketing messages? Int. J. Fash. Stud. 2019, 6, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterbenk, Y.; Champlin, S.; Windels, K.; Shelton, S. Is femvertising the new greenwashing? Examining corporate commitment to gender equality. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 177, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Munjal, A. Self-consciousness and emotions driving femvertising: A path analysis of women’s attitude towards femvertising, forwarding intention and purchase intention. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A. M.; Casais, B. Consumer reactions towards femvertising: A netnographic study. Corp. Commun. 2021, 26, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; Roca, D.; Sadaf, L.; Obaid, A. How does femvertising work in a patriarchal context? An unwavering consumer perspective. Corp. Commun. 2024, 29, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, L. K.; Jacobson, C.; Liasse, D.; Lund, E. Femvertising and its effects on brand image: A study of men’s attitude towards brands pursuing brand activism in their advertising. In LBMG Strategic Brand Management: Masters Papers Series; Strategic Brand Management (SBM): Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Poon, K. T.; Bai, Y. Sexism and the effectiveness of femvertising in China: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Sex Roles 2021, 84, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, E. Investigating consumers’ reactions towards female-empowerment advertising (femvertising) and female-stereotypical representations advertising (sex-appeal). J. Islamic Mark. 2024, 15, 1078–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champlin, S.; Sterbenk, Y.; Windels, K.; Poteet, M. How brand-cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: A qualitative exploration of ‘femvertising’. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 1240–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M.; Muldrow, A.; Rosengren, S. Diversity and inclusion in advertising research. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; He, L. Consumer responses to femvertising: A data-mining case of Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty” on YouTube. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayer, L. T.; Coleman, C. A.; Gurrieri, L. Driving impact through inclusive advertising: An examination of award-winning gender-inclusive advertising. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkestam, N.; Rosengren, S.; Dahlen, M. Advertising “like a Girl”: Toward a Better Understanding of “Femvertising” and Its Effects. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. J.; Lee, M. A femvertising campaign always# Like A Girl: Video responses and audience interactions on YouTube. J. Gend. Stud. 2021, 32, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkepatt, G.; Bryant, A.; Hill, R. P.; Nunziato, J. Can advertising benefit women’s development? Preliminary insights from a multi-method investigation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, V. E. The impact of female empowerment in advertising (femvertising). J. Res. Mark. 2017, 7, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture Bue, A. C.; Harrison, K. Empowerment sold separately: Two experiments examine the effects of ostensibly empowering beauty advertisements on women’s empowerment and self-objectification. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. R.; Shanthi, R. The Role of Femvertising in Women’s Empowerment: A Focus on FMCG Brand Campaigns in India ASR Chiang Mai Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Humanities 2025, 12, e2025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordrostami, M.; Laczniak, R. N. Female power portrayals in advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 1181–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A. C.; Yannopoulou, N.; Gorton, M.; Lie, S. Guilty displeasures? How Gen-Z women perceive (in) authentic femvertising messages. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2024, 45, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, N.; Kumar, N. Feminism in advertising: irony or revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Fem. Media Stud. 2022, 22, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X. “The Big Women”: A textual analysis of Chinese viewers’ perception toward femvertising vlogs. Glob. Media China 2020, 5, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Phua, J. Effects of brand name versus empowerment advertising campaign hashtags in branded Instagram posts of luxury versus mass-market brands. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, N. T.; Hatzithomas, L.; Chaput, L. Femvertising practices on social media: A comparison of luxury and non-luxury brands. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 1285–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeloff, C.; Bruns, J. Effectiveness of femvertising communications on social media: How brand promises and motive attributions impact brand equity and endorsement outcomes. Corp. Commun. 2024, 29, 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bumb, A. Femluencing: Integration of femvertising and influencer marketing on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Mogilner, C. Experiential gifts foster stronger social relationships than material gifts. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 43, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Parvathy; Givi, J. ; Dey, M.; Kent Baker, H.; Das, G. A bibliometric analysis on gift giving. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco-Illodo, I.; Heath, T. The ‘perfect gift’ and the ‘best gift ever’: An integrative framework for truly special gifts. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galak, J.; Givi, J.; Williams, E. F. Why certain gifts are great to give but not to get: A framework for understanding errors in gift giving. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, J.; Das, G. To earmark or not to earmark when gift-giving: Gift-givers' and gift-recipients' diverging preferences for earmarked cash gifts. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.K.; Broniarczyk, S.M. It’s not me, it’s you: How gift giving creates giver identity threat as a function of social closeness. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Teng, L.; Huang, X.; Foti, L.; Sun, C.; Yang, X. Face consciousness: the impact of gift packaging shape on consumer perception. Eur. J. Market. 2025, 59, 241–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternadori, M.; Abitbol, A. Support for women’s rights and feminist self-identification as antecedents of attitude toward femvertising. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freling, R. E.; Moore Koskie, M.; Freling, T. H.; Moulard, J. G.; Crosno, J. L. Exploring gift gaps: A meta-analysis of giver–recipient asymmetries. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, J.; Birg, L.; Lowrey, T. M.; Galak, J. An integrative review of gift-giving research in consumer behavior and marketing. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Mills, J.R. A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 232–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C. C.; Yang, Y. K.; Cheng, Y. C. Does relationship matter?–Customers’ response to service failure. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. H. The role of relationship on time and monetary compensation. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Kim, K. K. Appropriate service robots in exchange and communal relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C.; Kamvar, S.D.; Aaker, J. The shifting meaning of happiness. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 2, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Gallo, I. Consumers’ pursuit of material and experiential purchases: A review. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Gurrea, R.; Flavián, C. Using augmented reality to reduce cognitive dissonance and increase purchase intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).