1. Introduction

The proliferation of Information Technology (IT) in educational curricula has intensified the demand for efficient and effective assessment methodologies. Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQs) have long been a cornerstone of educational evaluation, particularly crucial in IT education where systematic evaluation of both technical knowledge and problem-solving abilities is essential [

22]. While MCQs offer significant advantages in terms of standardization and automated scoring, the manual creation of high-quality questions remains a resource-intensive process, requiring substantial expertise in both subject matter and assessment design [

49]. This challenge has prompted the development of automated Question Generation Systems (QGS) [

31].

Bloom’s Taxonomy provides a fundamental framework for educational assessment, particularly in technical subjects like IT. This taxonomy categorizes cognitive processes from basic recall to complex evaluation, establishing essential criteria for comprehensive assessment [

30]. Recent research has emphasized that effective IT education assessment must progress through these cognitive levels to develop students’ critical thinking and problem-solving abilities [

11]. This theoretical foundation underscores the importance of generating questions that not only test factual knowledge but also promote higher-order cognitive skills [

57].

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs) and Knowledge Graphs (KGs) [

9], have shown promise in automated question generation [

42]. However, existing research primarily focuses on technical capabilities rather than pedagogical alignment with frameworks like Bloom’s Taxonomy [

13]. Moreover, while these technologies demonstrate potential in generating basic questions, their effectiveness in supporting higher-order cognitive assessment remains largely unexplored. Our preliminary survey of 30 IT educators reveals that current QGS face three critical challenges that impede their widespread adoption and effectiveness in educational practice.

Foremost among these challenges is the generation of contextually relevant and accurate distractors. These incorrect options in MCQs play a pivotal role in discriminating between varying levels of student understanding. The intricacy of IT concepts magnifies this challenge, necessitating distractors that are plausible yet distinctly incorrect within specific technological contexts. Poorly designed distractors can lead to misinterpretation of a student’s knowledge and skills, ultimately undermining the validity of the assessment [

19].

Equally significant is the need to enhance the diversity of generated questions. A comprehensive assessment demands a varied question set that spans different cognitive levels and content areas, aligned with the hierarchical structure of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Current systems often produce homogeneous questions, thereby limiting their ability to evaluate a broad spectrum of knowledge and skills [

2]. This lack of diversity not only results in incomplete assessments but also fails to engage students effectively across different learning styles and abilities.

Perhaps the most formidable challenge lies in generating questions that promote higher-order thinking skills, particularly those aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy. While lower-order questions assessing recall and understanding are relatively straightforward to generate, creating questions that evaluate analysis, synthesis, and evaluation proves considerably more complex [

30]. The consistent production of such higher-order questions is crucial for developing the critical thinking and problem-solving skills essential in the rapidly evolving IT field.

These challenges highlight the need for a comprehensive solution that integrates advanced AI technologies with established educational principles. To address these multifaceted challenges, we propose Multi-Examiner, an innovative multi-agent system that integrates knowledge graphs (KGs), domain-specific search tools, and large language models (LLMs). This integration aims to enhance the contextual relevance, diversity, and cognitive depth of automatically generated IT MCQs. Our approach builds upon recent advancements in artificial intelligence and cognitive science, systematically integrating Bloom’s Taxonomy principles into each component of the system design, while maintaining alignment with established educational principles and assessment frameworks. The system design was further informed by extensive consultation with IT educators, ensuring its practical value in real educational settings.

The primary contributions of this study are fourfold. First, we develop a comprehensive knowledge graph and knowledge base for IT education, meticulously categorized according to Bloom’s taxonomy, enhancing the system’s capacity to generate contextually rich questions while maintaining pedagogical alignment. Second, we design and implement Multi-Examiner, a novel multi-agent system that synergistically combines KGs, domain-specific search tools, and LLMs to improve the quality, diversity, and cognitive depth of generated questions. Third, we introduce a multidimensional evaluation rubric that assesses both technical and pedagogical aspects of generated questions, facilitating continuous improvement of the QGS. Fourth, we conduct extensive empirical evaluation through rigorous testing with 30 experienced IT teachers, benchmarking the system’s effectiveness against both GPT-4 and human-crafted questions.

This research addresses the following questions (RQs):

RQ1: How effectively does Multi-Examiner enhance the generation of contextually relevant and accurate distractors to support meaningful assessment in IT education?

RQ2: To what extent does Multi-Examiner improve question diversity across different cognitive levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy to facilitate comprehensive learning evaluation?

RQ3: How effectively does Multi-Examiner generate and support higher-order thinking questions to promote critical thinking in IT education?

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of related work in QGS, with a focus on approaches utilizing KGs, LLMs, and educational taxonomies.

Section 3 details the methodology, including the architecture of Multi-Examiner and the evaluation process.

Section 4 presents the results of our comparative study, while

Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings for both educational technology and assessment practices. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of contributions and directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Building upon the challenges identified in automated question generation for IT education, this section examines recent technological advances and methodological developments in addressing these challenges. Question Generation Systems (QGS) face three major challenges in educational applications: ensuring contextual relevance and accuracy of distractors [

47], enhancing question diversity [

23], and incorporating higher-order thinking skills aligned with various learning levels [

2]. Recent technological advances have enabled new approaches to address these challenges through Knowledge Graphs (KGs), Knowledge Bases (KBs), Large Language Models (LLMs), and intelligent agents [

35,

55]. This section systematically examines these developments across four interconnected areas: KG/KB-based generation systems that provide structured knowledge representation, LLM and agent-based approaches that enable natural language understanding, applications of educational taxonomies that ensure pedagogical alignment, and evaluation frameworks that assess system effectiveness.

2.1. QGS Based on Knowledge Graphs and Knowledge Bases

Structured knowledge representation in education has progressed from basic taxonomies to advanced semantic networks [

37,

44], giving rise to Knowledge Graphs (KGs) and Knowledge Bases (KBs), each with unique benefits for educational QGS. KGs create flexible, dynamic networks of interconnected entities, enabling contextually relevant assessments [

36]. In contrast, KBs use structured schemas for precise content retrieval, ensuring consistency in assessment accuracy [

45,

52].

Three development phases have marked QGS evolution: template-based systems with static KBs, graph-based representations enabling advanced question generation, and the current convergence of KGs with Large Language Models (LLMs), significantly enhancing linguistic naturalness and factual accuracy [

34,

36]. KG-based QGS applications have expanded across narrative learning, achieving notable accuracy improvements [

33] and enhancing MOOC content evaluations [

27]. Advances in graph convolutional networks have further improved temporal reasoning tasks in QGS, achieving 70-80% accuracy in generating questions about sequential and causal relationships [

21]. Meta-analyses show these architectures boost question generation by 35-45% over traditional methods [

15]. KB technology has similarly evolved, showing promise in educational customization. Recent KB systems achieve 75-85% accuracy in creating multiple-choice questions aligned with learning objectives, thanks to advancements in semantic parsing [

24]. Integrating KBs with LLMs has enhanced domain-specific processing by 40-50% compared to conventional approaches, particularly for interdisciplinary questions [

43].

However, challenges remain in QGS, including limitations in synonym recognition and generating questions that engage higher-order thinking, with current systems achieving only 30-40% effectiveness in promoting complex cognitive skills [

49]. Redundancy in question format and cognitive demand also limits QGS diversity, particularly for advanced objectives.

2.2. QGS Based on LLMs and Intelligent Agents

Building on knowledge representation technologies, integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) and intelligent agents has transformed question generation capabilities [

17,

64]. This progress has evolved through three phases: initial transformer-based architectures, specialized agent integration, and hybrid systems. LLM-based systems now achieve 85-90% accuracy in generating contextually relevant questions, a notable improvement over traditional method [

18].

Advances in LLM architecture have enhanced contextual awareness and semantic understanding, achieving 40-50% higher educational relevance compared to prior systems [

12]. Improved attention mechanisms enable these models to better align questions with learning objectives, with 65-75% accuracy [

59]. Multi-agent architectures bring further improvements by decomposing question generation into specialized tasks, enhancing question diversity by 30-35% and alignment with learning outcomes by 25-30% [

2,

40]. Domain-specific knowledge integration has also improved precision, with 60-70% accuracy gains in specialized subjects [

60]. Research continues to optimize the synergy between LLMs and reasoning components, achieving 40-45% improvement in generating higher-order cognitive questions [

40]. Neural reasoning integration enables enhanced causal reasoning and conceptual understanding [

51].

Despite advancements, challenges persist. Performance variability remains across question types and difficulty levels, with a 15-25% accuracy fluctuation [

56]. Complex reasoning tasks face a 30-40% decrease in performance, and factual accuracy remains a challenge in specialized educational domains [

2]. Meta-analyses show significant benefits in educational assessment from integrated LLM and agent systems, with a 50-60% improvement in pedagogical alignment and content diversity [

41]. Hybrid systems combining LLMs with specialized agents achieve a 55-65% alignment with learning outcomes, and a 40-45% improvement in personalized learning contexts [

58]. Future research should focus on enhancing reasoning capabilities in LLMs to improve complex question generation by 35-40% and achieving a balance between linguistic fluency and factual accuracy, advancing the educational value of automatically generated questions [

39].

2.3. Application of Educational Objective Taxonomies in QGS

Educational taxonomies, evolving from simple classifications to advanced frameworks, play a crucial role in shaping automated question generation [

2,

30]. These frameworks help categorize cognitive levels, from basic recall to complex analysis, providing a foundation for creating diverse assessment tools [

62].

Applying Bloom’s Taxonomy in automated question generation has enhanced the cognitive calibration of assessments, achieving 70-80% success in matching questions to cognitive levels [

16,

25]. Incorporating knowledge dimensions with cognitive processes further advances question generation, improving the assessment of both factual knowledge and cognitive processing by 35-45% [

46]. Technological advancements have enabled taxonomic alignment in automated QGS, progressing from initial rule-based models with 30-40% accuracy to machine learning systems achieving 75-85% alignment accuracy [

20]. Neural architectures integrating taxonomies achieve balanced performance, maintaining 70-75% accuracy across all cognitive levels [

26].

Using multiple taxonomic dimensions enhances question quality by 40-45% for complex learning goals [

29], but challenges remain in generating questions for higher-order skills, with accuracy dropping to 45-50% for complex tasks [

49]. Additionally, maintaining consistent taxonomic alignment across subjects remains difficult, with systems achieving only 55-65% accuracy [

38]. Future research should focus on algorithms that maintain both cognitive complexity and content accuracy, integrating machine learning with taxonomic frameworks to enhance question quality across all levels. Hybrid approaches that combine traditional frameworks with neural architectures show promise for improving higher-order question generation [

50].

2.4. Exam Question Evaluation Scale

The development of evaluation frameworks for automated question generation has evolved significantly, reflecting advancements in educational assessment methodologies [

2,

10]. Early frameworks focused on linguistic accuracy, but modern frameworks integrate both technical and pedagogical metrics to better assess question quality [

2].

Modern evaluation frameworks are founded on three principles: content validity, cognitive alignment, and pedagogical effectiveness, with studies showing 40-50% improvement in assessing question quality when incorporating these dimensions [

14]. Machine learning systems have enhanced the evaluation of question difficulty and discrimination power, achieving 80-85% accuracy in predicting performance [

28]. Advanced NLP techniques further improve the evaluation of linguistic clarity and semantic coherence, achieving 85-90% accuracy [

32].

Integrated frameworks now simultaneously assess content accuracy, cognitive engagement, and pedagogical alignment, showing a 60-70% improvement in identifying relevant quality issues [

2]. Research on cognitive complexity reveals 45-55% improvement in evaluating higher-order thinking skills [

48]. However, current systems struggle with accuracy consistency across domains and predicting student performance, explaining only 40-45% of performance variance [

2]. Future research should focus on refining metrics for complex cognitive assessments, particularly higher-order skills, and on hybrid frameworks combining educational metrics with AI to enhance adaptability across diverse learning contexts [

54]. The integration of real-time feedback and adaptive criteria based on specific student and contextual needs offers potential for responsive and effective evaluation systems.

2.5. Synthesis and Research Gaps

The review of question generation systems reveals an evolution from rule-based methods to sophisticated integrations of knowledge graphs, machine learning, and large language models (LLMs). While initial systems achieved moderate success, contemporary models that integrate LLMs and intelligent agents show promise for complex question generation but still face technical integration challenges. Cognitive complexity remains a barrier, with current systems maintaining high accuracy for knowledge-level questions (80-85%) but struggling with higher-order questions, where accuracy drops to 30-40% [

61]. Domain-specific adaptability, particularly in technical education, also shows performance declines as complexity and specialization increase, with accuracy rates dropping to 45-55% for diverse and technically accurate question sets [

2].

Significant research gaps include limited multi-dimensional assessment frameworks, algorithmic bias, and adaptability for diverse educational needs. Current evaluation frameworks capture only 50-60% of essential quality metrics, and bias impacts performance by 15-25% across different contexts [

53]. Future directions include developing hybrid architectures that integrate knowledge graphs, LLMs, and specialized agents, projected to improve complex question generation by 30-40% [

63]. The proposed Multi-Examiner system addresses these gaps by combining advanced models and enhanced evaluation capabilities, potentially improving question accuracy by 25-30% and cognitive alignment by 35-40%. This system represents a meaningful step forward in generating technically precise, pedagogically sound questions, particularly for IT education.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

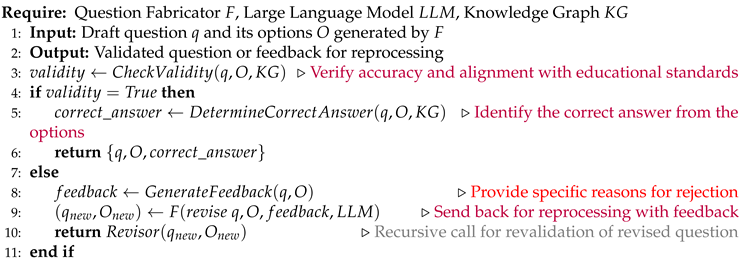

This study utilized a mixed-methods approach combining system development and experimental validation to improve the quality of automatically generated multiple-choice questions in IT education. The research framework, shown in

Figure 1, consisted of three phases: system development, experimental evaluation, and data analysis, progressively addressing research questions from foundational elements to advanced cognitive objectives. The study’s research questions (

RQ1, RQ2, RQ3) covered distractor quality, question diversity, and higher-order thinking skills, creating a structured pathway from micro-level elements to comprehensive cognitive assessment.

The Multi-Examiner system was designed based on Bloom’s Taxonomy with a modular architecture of knowledge graphs, knowledge bases, and multi-agent collaboration to ensure question quality. In the experimental phase, 30 experienced IT teachers evaluated questions generated by the Multi-Examiner system, GPT-4, and human experts. These questions covered core IT curriculum topics, aligned with Bloom’s cognitive levels. Data analysis utilized multivariate statistical methods to assess distractor relevance, question diversity, and higher-order thinking, using effect sizes and confidence intervals to establish significance.

3.2. System Development

The Multi-Examiner system employs a modular design with three core modules: knowledge graph, knowledge base, and multi-examiner system. This design is based on two principles: (1) improving question quality by integrating knowledge representation and intelligent agents, and (2) aligning questions with educational objectives through hierarchical cognitive design. The system innovatively combines knowledge engineering and AI, incorporating Bloom’s Taxonomy.

These modules operate collaboratively through structured data and control flows (

Figure 2). The knowledge graph provides semantic structures for the knowledge base, supporting organized retrieval. The knowledge base enables efficient access, while the multi-examiner system utilizes agents to interact with both modules for knowledge reasoning and expansion. This bidirectional interaction allows for rich, objective-aligned question generation and continual knowledge optimization.

3.2.1. Knowledge Graph Construction

The knowledge graph construction in the Multi-Examiner system takes Bloom’s Taxonomy as its theoretical foundation, achieving deep integration of educational theory and technical architecture through systematic knowledge representation structures. At the knowledge representation level, the research develops based on two dimensions of Bloom’s Taxonomy: the knowledge dimension and the cognitive process dimension. The knowledge dimension is reflected through core attributes of entities, with each knowledge point entity containing detailed knowledge descriptions and cognitive type annotations. The knowledge description attribute not only provides basic definitions and application scopes of entities but, more importantly, structures knowledge content based on Bloom’s Taxonomy framework. The cognitive type attribute strictly follows Bloom’s four-level knowledge classification: factual knowledge (e.g., professional terminology, technical details), conceptual knowledge (e.g., principles, method classifications), procedural knowledge (e.g., operational procedures, problem-solving), and metacognitive knowledge (e.g., learning strategies, cognitive monitoring).

In the cognitive process dimension, the knowledge graph implements support for different cognitive levels through relationship type design. For example, the Contains relationship primarily serves knowledge expression at the remembering and understanding levels, supporting the cultivation of basic cognitive abilities through explicit concept hierarchies. The Belongs to relationship focuses on supporting cognitive processes at the application and analysis levels, helping learners construct knowledge classification systems. The Prerequisite relationship plays an important role at the evaluation level, promoting critical thinking development by revealing knowledge dependencies. The Related relationship mainly serves the creation level, supporting innovative thinking through knowledge associations. This relationship design based on cognitive theory ensures that the knowledge graph can provide theoretical guidance and knowledge support for generating questions at different cognitive levels.

Through this systematic theoretical integration, the knowledge graph not only achieves structured knowledge representation but, more importantly, constructs a knowledge framework supporting cognitive development. When the system needs to generate questions at specific cognitive levels, it can conduct knowledge retrieval and reasoning based on corresponding entity attributes and relationship types, thereby ensuring that generated questions both meet knowledge content requirements and accurately match target cognitive levels.

3.2.2. Knowledge Base Construction

The knowledge base module adopts a layered processing design philosophy, establishing a systematic knowledge processing and organization architecture to provide foundational support for diverse question generation. This study innovatively designed a three-layer processing architecture encompassing knowledge formatting, knowledge vectorization, and retrieval segmentation, achieving systematic transformation from raw educational resources to structured knowledge. This layered architectural design not only enhances the efficiency and accuracy of knowledge retrieval but also provides a solid data foundation for generating differentiated questions.

At the knowledge formatting level, the system employs Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology to convert various educational materials into standardized digital text. The knowledge formatting process is formally defined as:

where

represents raw educational materials, including textbooks, teaching syllabi, and professional literature. This standardization process ensures content consistency and lays the foundation for subsequent vectorization processing. The system optimizes recognition results through multiple preprocessing mechanisms, including text segmentation, key information extraction, and format standardization, to enhance knowledge representation quality.

At the knowledge vectorization stage, a hybrid vectorization strategy is employed to transform standardized text into high-dimensional vector representations. This transformation process is formally defined as:

where

k is a snippet of formatted knowledge from

, and

represents the vectorized form of

k, utilizing models such as TF-IDF, Word2Vec or advanced techniques like BERT embeddings. The system innovatively designs a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, adaptively adjusting weights of various vectorization techniques based on different knowledge types and application scenarios, enhancing knowledge representation accuracy. This vectorization method ensures that semantically similar knowledge points maintain proximity in vector space, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent similarity calculations and association analyses.

At the retrieval segmentation level, the system systematically organizes vectorized knowledge based on predefined domain tags. The formal expression for retrieval segmentation is:

where

represents the segmented KB,

are individual pieces of vectorized knowledge,

denotes the domain or knowledge point tags associated with each

and

is the function that assigns each vectorized knowledge piece to its corresponding segment in the KB. The system designs a multi-level index structure, supporting rapid location and extraction of knowledge content from different dimensions while enabling knowledge recombination mechanisms to support diverse question generation requirements. This layered organization structure not only enhances knowledge retrieval efficiency but also provides flexible knowledge support for generating questions at different cognitive levels.

This study constructed a comprehensive knowledge base system around core IT curriculum knowledge. Through systematic layered processing architecture, this knowledge base achieves efficient transformation from raw educational resources to structured knowledge. The knowledge base not only supports precise retrieval based on semantics but can also provide differentiated knowledge support according to different cognitive levels and knowledge types, laying the foundation for generating diverse and high-quality questions. This layered knowledge processing architecture significantly enhances the system’s flexibility and adaptability in question generation, better meeting assessment needs across different teaching scenarios.

3.2.3. Multi-Examiner System Design

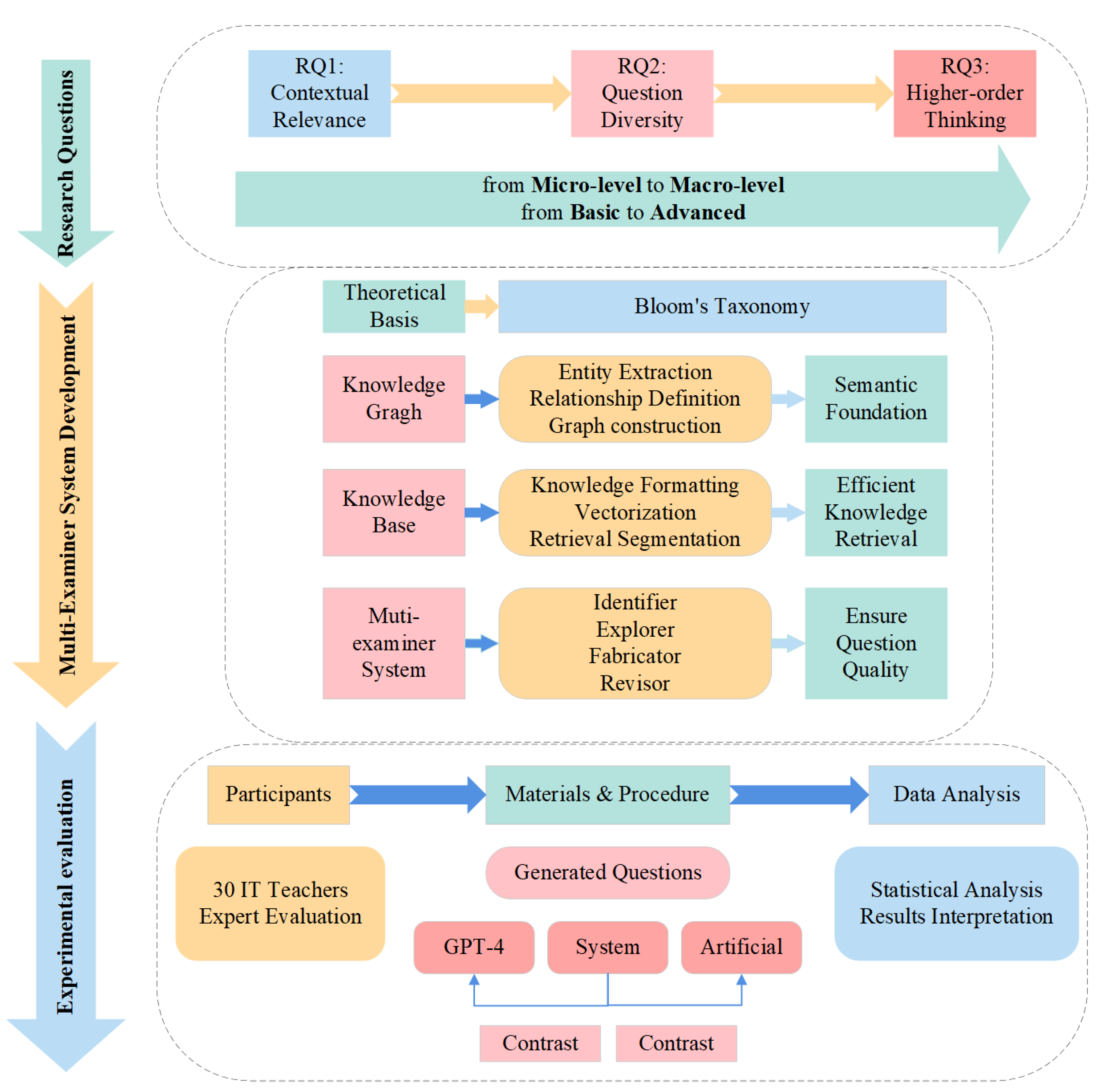

The Multi-Examiner module is grounded in modern educational assessment theory, integrating cognitive diagnostic theory, item generation theory, and formative assessment theory to construct a theory-driven intelligent agent collaborative assessment framework. This framework innovatively designs four types of intelligent agents: Identificador, Explorador, Fabricator, and Revisor, forming a complete question generation pipeline. Through four specialized intelligent agents, the system achieves precise control over the question generation process, with each agent designed based on specific educational theories, collectively constituting a comprehensive intelligent educational test item generation system (

Figure 3). This theory-based multi-agent system framework design not only ensures the educational value of generated questions but also provides a new technical paradigm for educational measurement and evaluation.

The Identificador, designed based on schema theory, is responsible for deep semantic understanding and cognitive feature analysis of knowledge points. This agent implements knowledge retrieval through the function:

where

represents the set of synonyms and related terms,

k is the original knowledge point input by the user, and

denotes the Large Language Model’s operation to fetch and generate synonymous and related terms using its trained capabilities on vast corpora and search engine integration. The Identificador not only identifies surface features of knowledge points but, more importantly, analyzes cognitive structures and semantic networks based on schema theory. For example, when processing the knowledge point "Operating System," the Identificador first constructs its cognitive schema, including core attributes (such as system software characteristics), process features (such as resource management mechanisms), and relational features (such as interactions with hardware and application software), thereby providing a complete cognitive framework for subsequent question generation.

The Explorador adopts constructivist learning theory to guide knowledge association exploration, implementing multi-dimensional semantic connections in the knowledge graph through the function:

where

represents the detailed knowledge entries,

is the set of input terms from the Identificador,

is the knowledge graph. This agent innovatively implements directed retrieval strategies based on cognitive levels, capable of selecting corresponding knowledge nodes according to different cognitive levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. For example, when generating higher-order thinking questions, the Explorador prioritizes knowledge nodes related to advanced cognitive processes such as analysis, evaluation, and creation, establishing logical connections between these nodes to provide knowledge support for generating complex assessment tasks.

The Fabricator integrates cognitive load theory and question type design theory, implementing dynamic question generation through the function:

where

represents the question generated,

t is the type of knowledge (factual, conceptual, procedural, metacognitive),

k is the knowledge point,

is the tailored prompt for type

t. The Fabricator’s innovation is reflected in its ability to dynamically adjust question complexity according to learning objectives. This agent adopts specific generation strategies (

) for different cognitive objectives (

t), ensuring assessment validity while controlling question cognitive load levels. The Fabricator’s innovation is reflected in its ability to dynamically adjust question complexity according to learning objectives. For example, when generating conceptual understanding questions, the system controls information quantity and problem context complexity to ensure optimal cognitive load levels.

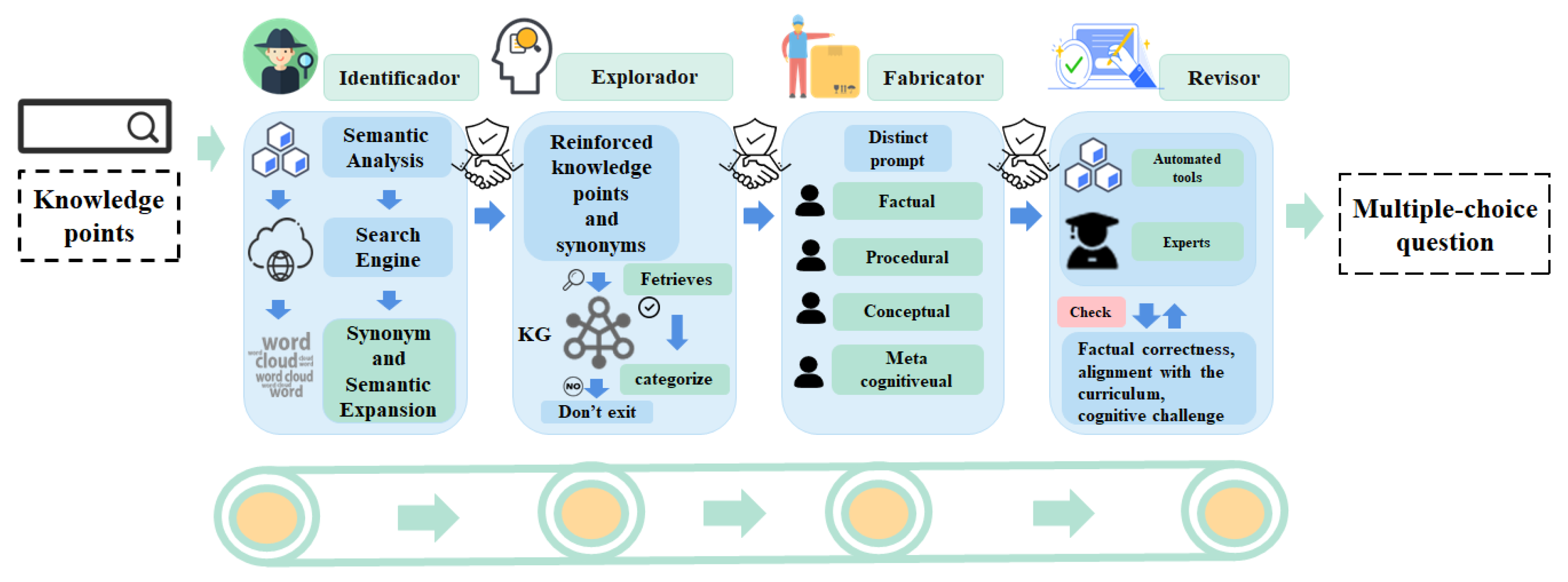

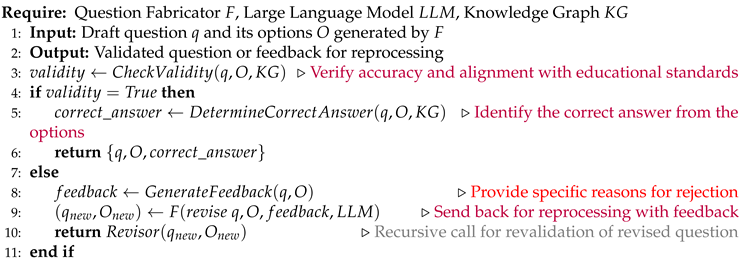

The Revisor constructs a systematic quality control mechanism based on educational measurement theory. As shown in Algorithm 1, the Revisor ensures question quality through multi-dimensional evaluation criteria. The

function not only verifies technical correctness but, more importantly, evaluates consistency between questions and educational objectives. When quality issues are detected, the system generates specific modification suggestions through the

function and triggers optimization processes. This closed-loop quality control mechanism ensures the system can continuously produce high-quality assessment questions.

|

Algorithm 1 Question Validation and Finalization Process by Revisor |

|

At the agent collaboration level, the system uses an event-driven mechanism grounded in educational assessment theory, forming a complete question generation and evaluation chain. Based on Cognitive Development and Adaptive Assessment theories, this design ensures continuity and adaptability. The Identificador assesses cognitive features, triggering the Explorador to construct knowledge networks, which the Fabricator uses to dynamically adjust question strategies, with the Revisor providing final evaluation.

To enhance scalability, the Multi-Examiner system employs a microservice modular design, enabling each agent to function independently through standardized APIs. The system’s innovation spans three theoretical levels: (1) systematic application of educational theories, (2) precise cognitive mapping in question design, and (3) formative assessment implementation. This framework integrates educational integrity with AI-driven automation, advancing adaptability in question generation.

The design prioritizes educational purpose alongside technical innovation, ensuring generated questions serve meaningful educational needs. The modular architecture allows for continuous adaptation, supporting the integration of new theories and technologies to maintain relevance in educational technology.

3.3. Experimental Design

To ensure rigorous evaluation of the Multi-Examiner system’s effectiveness, we designed a systematic experimental protocol encompassing three main components: participant selection, experimental materials and procedures, and evaluation metrics. The research employed expert evaluation methodology to comparatively analyze the quality differences between system-generated questions and other generation methods.

3.3.1. Participants

Purposive sampling was used to form an expert evaluation team for assessing the quality of automatically generated multiple-choice questions. Statistical power analysis ( = .05, power = .80, partial = .06) determined a minimum sample size of 28, leading to the recruitment of 30 experts to account for potential attrition. Selection focused on professional background, teaching experience, and technological literacy, with all experts having at least five years of high school IT teaching experience, training in Bloom’s Taxonomy, and educational technology experience. The panel consisted of 18 females (60%) and 12 males (40%), averaging 8.3 years of teaching experience (SD = 2.7); 73% had experience with AI-assisted tools, providing diverse perspectives.

A standardized two-day training ensured evaluation reliability, combining theory with practical application of evaluation criteria. Pre-assessment on 10 test questions showed high inter-rater consistency (Krippendorff’s = .83). For significant scoring discrepancies, consensus was achieved through discussion. Systematic validity and reliability testing confirmed scoring stability, with test-retest reliability after two weeks achieving a correlation coefficient of .85, indicating strong scoring consistency among experts.

3.3.2. Experimental Materials and Procedures

This study used a systematic experimental design to ensure rigor, involving multiple-choice questions from three sources: Multi-Examiner, GPT-4, and human-created questions. These questions were generated using identical knowledge points and assessment criteria for comparability. Six core knowledge points from the high school IT curriculum unit "Information Systems and Society" were selected, reviewed by three senior IT education experts, and covered four types defined by Bloom’s Taxonomy (factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive), resulting in 72 questions. Chi-square testing confirmed a balanced distribution across sources ( = 1.86, p > .05).

A triple-blind review design kept evaluators unaware of question sources, with uniform formatting and a Latin square arrangement to minimize sequence and fatigue effects (ANOVA: F = 1.24, p > .05). Standardized evaluation processes were used, with questions independently scored by two experts and a third reviewer in cases of large scoring discrepancies (≥ 2 points). No significant differences were found among groups in text length (F = 0.78, p > .05) or language complexity (F = 0.92, p > .05). Semi-structured interviews (n = 10) indicated high alignment with real teaching practices (mean = 4.2/5), and qualitative data coding achieved high inter-coder reliability (Cohen’s = .85).

3.3.3. Measures and Instruments

This study constructed an evaluation framework based on Bloom’s Taxonomy, focusing on three dimensions: distractor relevance, question diversity, and higher-order thinking. Distractor relevance evaluated conceptual relevance, logical rationality, and clarity, each rated on a five-point scale. Question diversity assessed cognitive level coverage, domain distribution, and form variation to ensure a balanced assessment across Bloom’s levels. Higher-order thinking measured cognitive depth, challenge level, and application authenticity, with criteria verified through expert consultation and pilot testing.

To ensure rigor, the framework’s content validity achieved a Content Validity Ratio of 0.78, while construct validity was confirmed through factor analysis (/df = 2.34, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.076). Reliability testing included inter-rater reliability (Krippendorff’s > 0.83), test-retest reliability (r = 0.85), and internal consistency (Cronbach’s > 0.83) across dimensions, all demonstrating high reliability.

3.3.4. Data Analysis

This study applied a systematic data analysis framework for three research questions. Descriptive statistics provided an overview of data, followed by inferential analyses tailored to each question, with effect sizes calculated for reliability. Data preprocessing included cleaning, normality checks (Shapiro-Wilk test), and variance homogeneity tests (Levene’s test). Missing values were addressed through multiple imputation.

For RQ1 (distractor relevance), two-way ANOVA assessed effects of generation methods and knowledge types, with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests for significant interactions. RQ2 (question diversity) employed MANOVA, with follow-up ANOVAs and Pearson correlations between dimensions. For RQ3 (higher-order thinking), mixed-design ANOVA examined cognitive level differences, using Games-Howell post-hoc tests for robustness. Effect sizes (partial , Cohen’s d, and r) were reported with confidence intervals, focusing on practical significance.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB-2024-ED-0127). All participating teachers were informed of the research purpose, procedures, and data usage, and provided written informed consent. Research data were anonymized, with all personally identifiable information removed from research reports. Data collection and storage followed strict confidentiality protocols, with access restricted to core research personnel. Participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences.

4. Results

In this section, we present our research findings aimed at enhancing the generation of MCQs in IT education using the Multi-Examiner system. We discussed three main RQs. Our analysis includes descriptive statistics, variance analyses (ANOVA and MANOVA), and post-hoc tests to compare the performance of the Multi-Examiner system against GPT-4 and human-generated questions. The results highlight the system’s effectiveness in generating contextually relevant distractors, enhancing question diversity, and producing high-quality questions that assess higher-order thinking skills. The detailed findings are organized into subsections corresponding to each research question.

4.1. Analysis of the Contextual Relevance of Distractors (RQ1)

To address RQ1, we conducted an in-depth analysis of distractors generated by different methods—GPT-4 and human-generated questions—across four types of knowledge: factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive.

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of distractor relevance scores for each group. From this data, we observe the following trends: (1) Multi-Examiner achieved higher average scores than both GPT-4 and human-generated methods across most knowledge types. (2) Multi-Examiner performed exceptionally well in the relevance of distractors for factual and metacognitive knowledge. (3) The scores for distractors generated by Multi-Examiner and human methods were relatively close across all knowledge types, while GPT-4’s scores were comparatively lower.

4.1.2. Two-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

To further analyze the contextual relevance of distractors, we conducted a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Before performing the analysis, we checked the assumptions of ANOVA, including normality (using the Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (using Levene’s test). The results indicated that the data generally met these assumptions (p > .05).

Table 2 presents the results of the ANOVA, where the dependent variable is the distractor relevance score, and the independent variables are the generation method and knowledge type. The analysis revealed: (1) Significant Main Effect of Generation Method: F(2, 348) = 19.85, p < .001, partial

= 0.08. According to Cohen (1988), this is considered a medium effect size, indicating substantial differences in distractor relevance across different generation methods. (2) Significant Main Effect of Knowledge Type: F(3, 348) = 4.34, p = .005, partial

= 0.03. This is a small effect size, suggesting that the type of knowledge significantly affects the relevance scores of the distractors. (3) Significant Interaction Between Generation Method and Knowledge Type: F(6, 348) = 5.79, p < .001, partial

= 0.07. This medium effect size indicates that the combination of generation method and knowledge type significantly influences distractor relevance scores, showing distinct performance patterns.

To further explore the differences between the two groups, we conducted Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test. Considering the potential inflation of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, we applied Bonferroni correction to adjust the p-values.

Table 3 presents the adjusted results. The post-hoc test results indicate that: (1) The distractor relevance of questions generated by the Multi-Examiner is significantly higher than that of GPT-4 (p < .001), but there is no significant difference compared to human-generated questions (p = 1.000). (2) Among the knowledge types, the score for factual knowledge is significantly lower than that for conceptual knowledge but does not differ significantly from procedural and metacognitive knowledge.

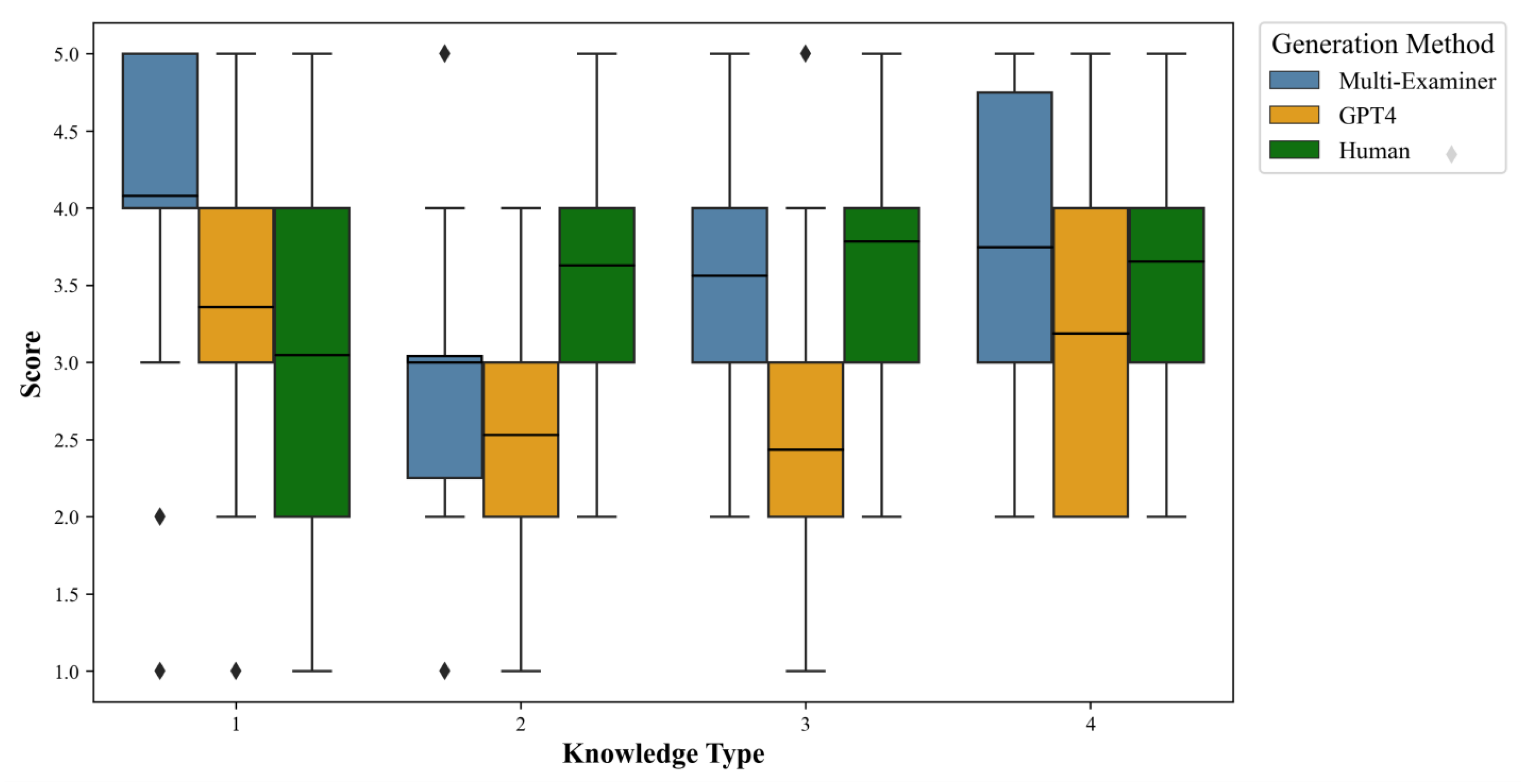

4.1.3. Performance Differences by Generation Method Across Different Knowledge Types

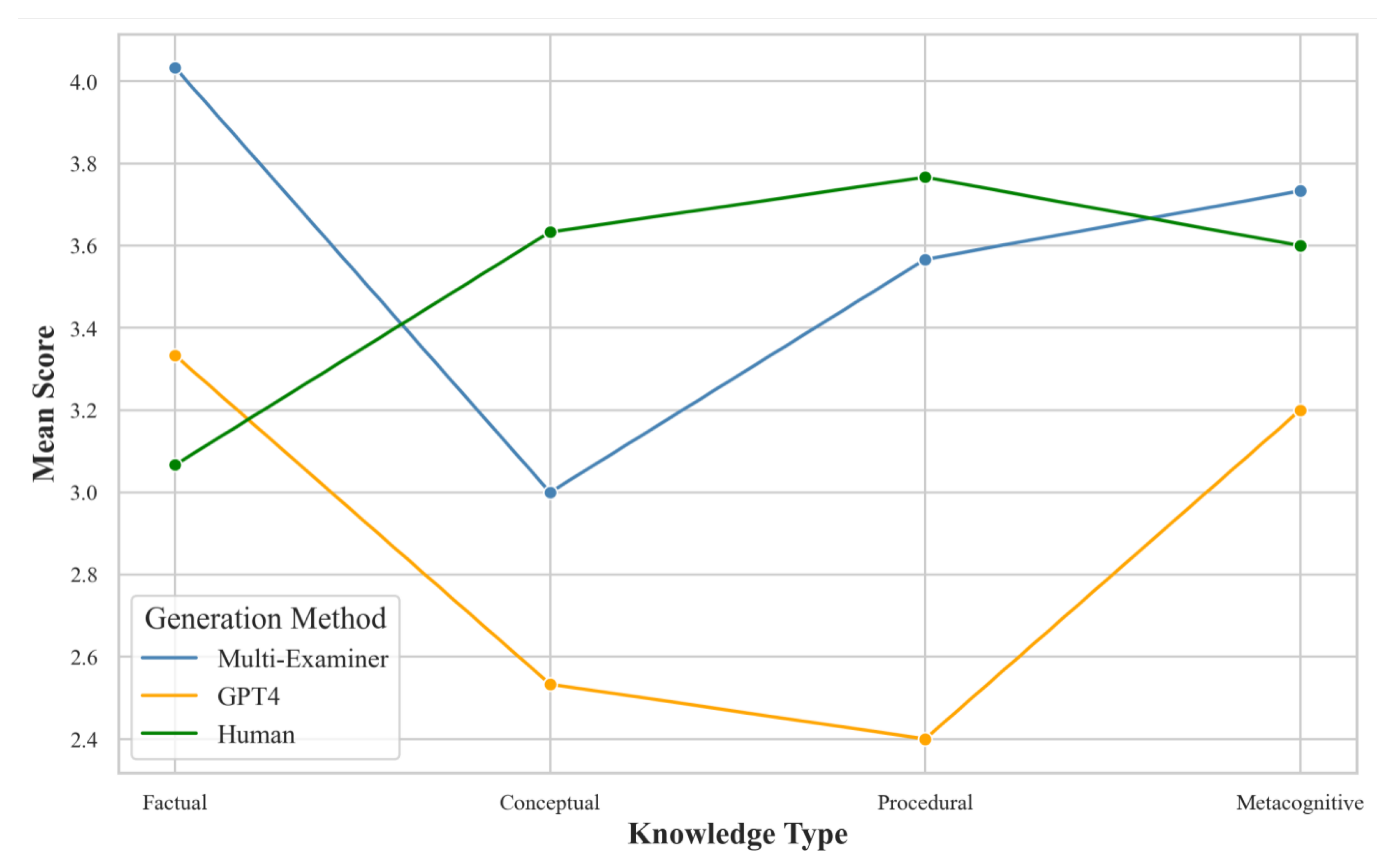

Figure 4 visually displays the performance differences among the generation methods across different knowledge types. From

Figure 4, we can observe the following: (1) The Multi-Examiner has a more concentrated score distribution across all knowledge types, with median scores generally higher than the other two methods, especially pronounced in factual and conceptual knowledge. (2) GPT-4 shows a more dispersed score distribution, particularly in factual and conceptual knowledge, where its performance is relatively poorer. (3) The score distribution for human-generated distractors is close to that of the Multi-Examiner, performing well especially in procedural and metacognitive knowledge.

Figure 5 further illustrates the relationship between generation methods and knowledge types. From

Figure 5, we can make the following observations: (1) The Multi-Examiner outperforms both GPT-4 and human-generated methods across most knowledge types, with a particularly strong advantage in factual knowledge. (2) GPT-4 generally performs poorly across all knowledge types, especially in procedural knowledge. (3) The performance differences among the three generation methods are relatively small in metacognitive knowledge, suggesting that the impact of the generation method might be less significant for these higher-order cognitive tasks.

4.2. Analysis of Enhancing Question Diversity (RQ2)

To address RQ2, we evaluated the diversity of question sets generated by three methods: Multi-Examiner, GPT-4, and human-generated. Thirty high school IT teachers, serving as expert evaluators, rated the question sets across three dimensions: diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking.

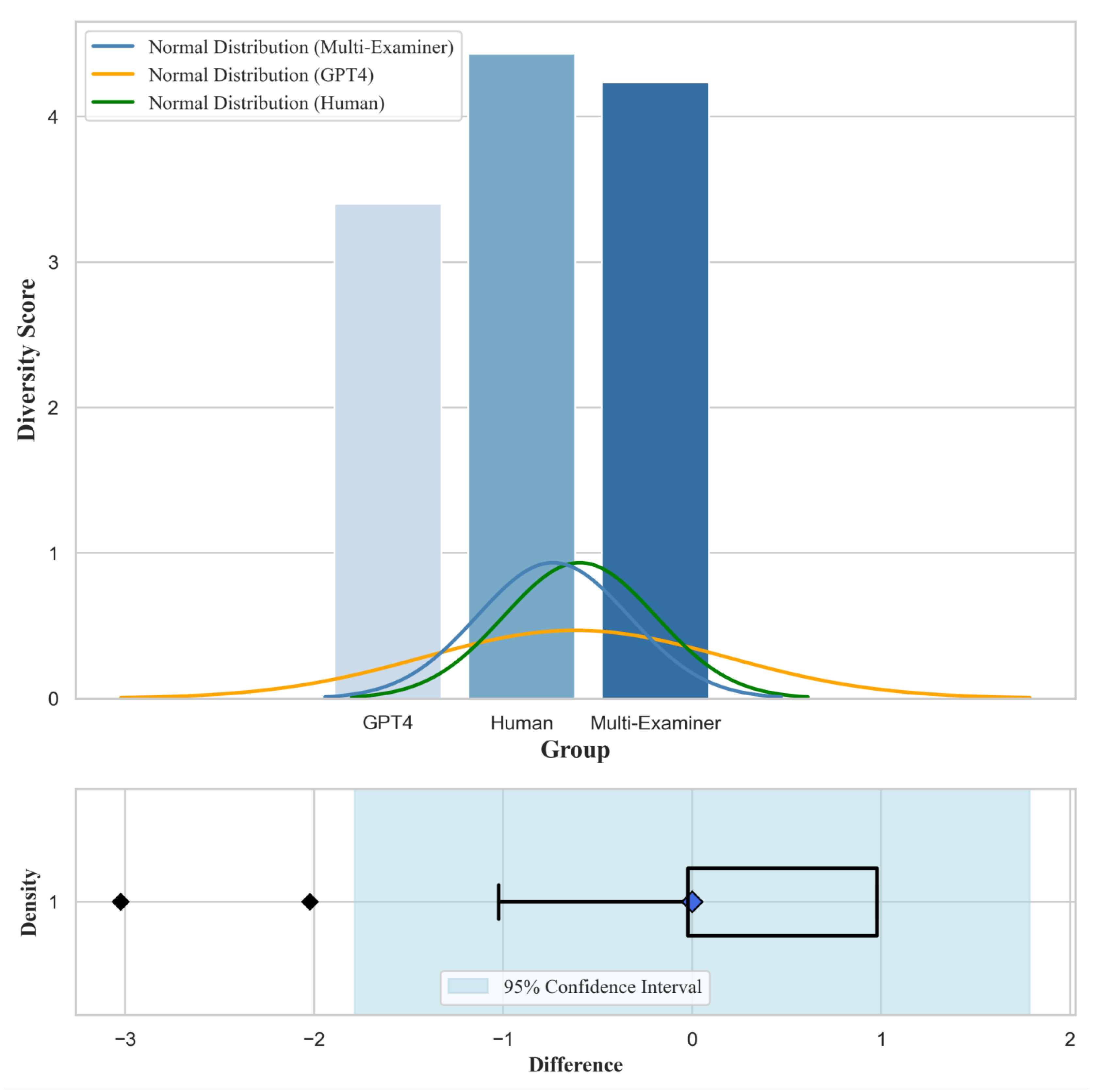

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the three methods across the diversity dimension. From

Table 4, we observe the following trends: (1) The Multi-Examiner achieved a significantly higher average score in the diversity dimension compared to GPT-4, and its score is very close to that of the human-generated method. (2) GPT-4 scored lower in diversity than the other two methods. (3) Human-generated question sets scored slightly higher in diversity than the Multi-Examiner, although the difference is minimal.

4.2.2. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA)

To analyze in depth the impact of generation methods on the diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking of the question sets, we conducted a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). Before performing the analysis, we checked the assumptions of MANOVA, including multivariate normality (using Mardia’s test) and homogeneity of covariance matrices (using Box’s M test). The results indicated that the data generally met these assumptions (p > .05).

Table 5 presents the results of the MANOVA, with the independent variable being the generation method and the dependent variables being the scores for diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking. The MANOVA results showed that the generation method has a significant overall effect on the diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking of the question sets (Wilks’

= 0.523, F(6, 170) = 11.258, p < .001, partial

= 0.284). According to Cohen (1988), this represents a large effect size, indicating that the generation method has a substantial impact on the overall quality of the question sets.

4.2.3. Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Follow-up Tests

To further explore the specific differences in generation methods across various dimensions, we conducted separate univariate ANOVAs for each dependent variable and applied Bonferroni corrections to control the Type I error rate.

Table 6 presents the results of these ANOVAs. The results indicate that the generation method significantly affects all three dimensions: diversity (F(2, 87) = 13.002, p < .001, partial

= 0.309), challenge (F(2, 87) = 12.530, p < .001, partial

= 0.301), and higher-order thinking (F(2, 87) = 17.724, p < .001, partial

= 0.379).

We further conducted Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests, the results of which are shown in

Table 7. The post-hoc test results indicate: (1) Multi-Examiner significantly outperforms GPT-4 across all dimensions (p < .001). (2) There are no significant differences between Multi-Examiner and human-generated question sets across all dimensions (p > .05). (3) Human-generated question sets significantly outperform GPT-4 across all dimensions (p < .001).

4.2.4. Performance Differences by Generation Method Across Evaluation Dimensions

To provide a more visual representation of the performance differences across various evaluation dimensions for different generation methods, I used parallel coordinate plots. These plots display the performance differences among the three generation methods (Multi-Examiner, GPT-4, and human-generated) across three dimensions: diversity (0), challenge (1), and higher-order thinking (2). This visualization helps us comprehensively compare the strengths and weaknesses of each generation method.

From

Figure 6, we can observe the following: (1) The performance of the Multi-Examiner and human-generated methods are very close across the dimensions of diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking, with slight differences, but both generally maintain a high level. (2) GPT-4 shows a clear disadvantage in all dimensions, especially in terms of challenge and higher-order thinking, where its performance is relatively weaker.

4.3. Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Assessment System in Generating Higher-Order Thinking Questions (RQ3)

To address RQ3, we conducted a thorough analysis of higher-order thinking questions generated by the Multi-Examiner system, GPT-4, and human methods.

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 8 presents the descriptive statistics for questions generated by the three methods across the six cognitive levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Scoring was done using a 1-5 Likert scale, where 1 represents "very poor" and 5 represents "excellent." Each generation method had 30 samples (N=30) at each cognitive level.

From

Table 8, we can observe the following preliminary trends: (1) All generation methods generally perform better on lower-order thinking skills (Memory, Understanding) than on higher-order thinking skills (Analysis, Evaluation, Creation). (2) Multi-Examiner scores higher on average in higher-order thinking skills (especially in Evaluation and Creation levels) compared to GPT-4, but slightly lower than human-generated questions. (3) GPT-4’s performance on higher-order thinking skills is notably lower than the other two methods, particularly in the Evaluation and Creation levels. (4) Human-generated questions show the most stable performance across all cognitive levels, with relatively small standard deviations. (5) At the Creation level, Multi-Examiner (M = 3.73, SD = 0.91) significantly outperforms GPT-4 (M = 3.00, SD = 1.08), and is close to the human-generated level (M = 3.80, SD = 0.89). (6) As the cognitive levels increase, the differences in scores among the three generation methods grow, especially in the Evaluation and Creation levels.

4.3.2. Two-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

To deeply analyze the impact of generation methods and cognitive levels on question quality, we conducted a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Before performing the analysis, we verified the prerequisites for ANOVA, including normality (using the Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (using Levene’s test). The results showed that the data generally met these assumptions (p > .05).

Table 9 presents the results of the ANOVA, where the dependent variable is the question quality score, and the independent variables are the generation method and cognitive level. The analysis revealed: (1) Significant main effect of generation method: F(2, 530) = 13.76, p < .001, partial

= 0.05. According to Cohen (1988), this is considered a medium effect size, indicating significant differences in question quality across different generation methods. (2) Significant main effect of cognitive level: F(5, 530) = 26.37, p < .001, partial

= 0.20. This represents a large effect size, suggesting that cognitive level has a significant impact on question quality. (3) Significant interaction effect between generation method and cognitive level: F(10, 530) = 2.27, p = .013, partial

= 0.04. Although the effect size is small, it indicates that the combination of generation method and cognitive level has a noticeable impact on question quality.

4.3.3. Post-Hoc Test Analysis

To further explore differences between groups, we conducted Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests. Considering the potential for Type I errors due to multiple comparisons, we applied Bonferroni corrections to adjust the p-values.

As shown in the

Table 10, The post-hoc test results reveal: (1) The quality of questions generated by Multi-Examiner is significantly better than those generated by GPT4 (p < .001), but there is no significant difference compared to human-generated questions (p = .267). (2) Human-generated questions are significantly better in quality compared to those generated by GPT4 (p < .001). (3) There are no significant differences between higher-order thinking skills (Analysis, Evaluation, Creation), indicating that the difficulty level of questions across these cognitive skills is similar.

4.3.4. Differences in Performance Across Cognitive Levels by Generation Method

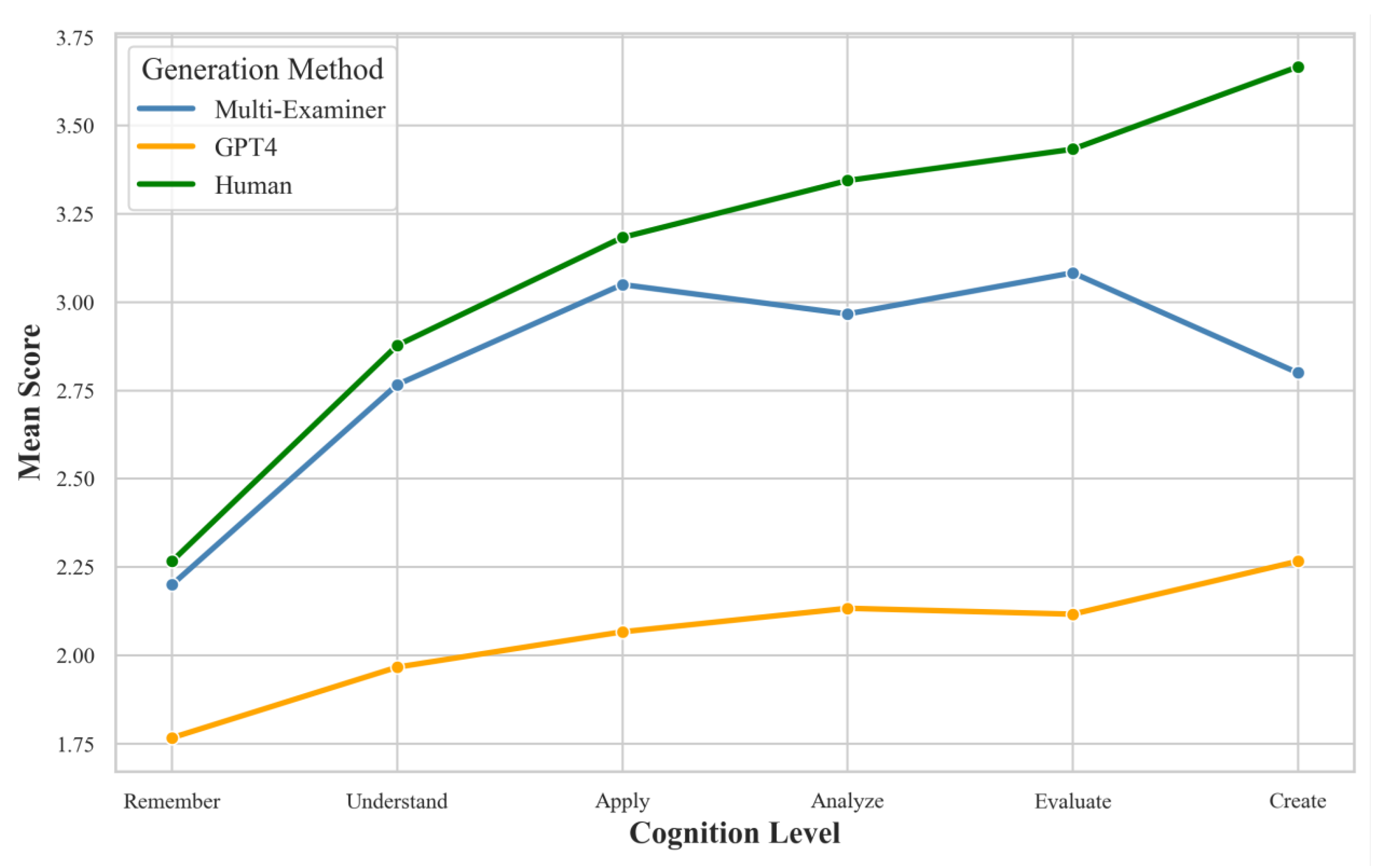

To visually demonstrate the performance differences across cognitive levels for different generation methods, we created an interaction effect

Figure 7.

From

Figure 7, we can observe the following trends: (1) Multi-Examiner significantly outperforms GPT-4 in higher-order thinking skills (particularly in the Evaluation and Creation levels) and is close to the level of human-generated questions. (2) GPT-4 performs well in lower-order thinking skills (Memory, Understanding) but shows a marked decline in higher-order thinking skills. (3) Human-generated questions exhibit the most stable performance across all cognitive levels, especially maintaining a high level in higher-order thinking skills. (4) The performance gap between Multi-Examiner and human-generated questions is small in the Evaluation and Creation levels, indicating that Multi-Examiner has good potential in generating questions that require higher-order thinking.

4.3.5. Quality Analysis of Higher-Order Thinking Questions

To better address RQ3, we specifically focused on the three higher-order thinking levels: Analysis, Evaluation, and Creation.

Table 11 presents the mean scores and standard deviations for these three levels across the different generation methods.

We conducted univariate ANOVAs for the Analysis, Evaluation, and Creation levels separately, with results shown in

Table 12. The findings are as follows: (1) At the Analysis level, there is no significant difference between the three generation methods (F(2, 87) = 2.14, p = .123, partial

= 0.04). This indicates that Multi-Examiner performs similarly to GPT-4 and human-generated methods when generating questions at the analysis level. (2) At the Evaluation level, the generation method has a significant impact on question quality (F(2, 87) = 4.27, p = .017, partial

= 0.07). The effect size is medium, suggesting that there are substantial differences in the quality of questions generated by different methods at this level. (3) At the Creation level, the impact of the generation method is most significant (F(2, 87) = 6.89, p = .002, partial

= 0.10). This is a medium-to-large effect size, indicating that at the highest cognitive level, the generation method has the greatest influence on question quality.

To further explore the differences between groups, we conducted Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests for the Evaluation and Creation levels, with the results shown in

Table 13. From these analyses, we can draw the following conclusions: (1) Multi-Examiner performs exceptionally well in generating higher-order thinking questions, particularly at the Evaluation and Creation levels. Its performance is significantly better than GPT-4 and close to the level of human-generated questions. (2) At the Analysis level, there are no significant differences between the three methods, which may indicate that automated methods have reached a level comparable to human performance at this stage. (3) As the cognitive levels increase (from Analysis to Evaluation and then to Creation), the differences between generation methods grow, reflecting the challenge of generating questions that require higher-order thinking skills. (4) GPT-4 shows clear limitations in generating higher-order thinking questions, particularly at the Creation level, highlighting the importance of incorporating additional structured information, such as knowledge graphs. (5) The performance of Multi-Examiner at the Evaluation and Creation levels shows no significant difference from that of human-generated questions, indicating that the system has strong potential in generating high-quality, higher-order thinking questions.

5. Discussions

5.1. Discussion of Distractor Contextual Relevance and Generation Method Effectiveness (RQ1)

Based on the above analysis, we conclude that Multi-Examiner demonstrates a significant advantage in generating contextually relevant distractors, especially for factual and procedural knowledge types. These findings align with previous research, such as Smith et al. (2022), which emphasizes the potential of combining knowledge graphs and LLMs to improve question quality. The effectiveness of Multi-Examiner suggests that leveraging structured domain-specific information enhances the generation of distractors, achieving a quality level comparable to that of human-generated questions across multiple knowledge types. The higher scores observed for conceptual and metacognitive knowledge types indicate that these areas may be less challenging for automated systems, likely due to the more flexible nature of the knowledge involved, which allows for more variance in distractor generation.

The limitations of GPT-4 in generating high-quality distractors, particularly for factual knowledge, suggest a need for further development of LLMs tailored to educational assessment tasks. This performance gap may stem from GPT-4’s lack of structured, domain-specific knowledge, affecting its ability to generate distractors that are closely related to specific knowledge points. Additionally, the lower performance in factual knowledge highlights the inherent difficulty in generating distractors for this knowledge type, as it often has clear right and wrong distinctions, making it challenging to create distractors that are both relevant and misleading. These findings have practical implications, indicating that while automated systems like Multi-Examiner show great potential, further optimization, particularly in factual knowledge areas, is needed to enhance the system’s application in educational settings.

5.2. Discussion on Enhancing Question Diversity and Cognitive Challenge through Automated Generation Methods (RQ2)

The analysis indicates that Multi-Examiner has a clear advantage in enhancing the diversity, challenge, and higher-order thinking of generated question sets, particularly when compared to GPT-4. This finding highlights the potential of integrating knowledge graphs and domain-specific search tools with large language models (LLMs) to improve the quality and diversity of automatically generated questions. The performance of Multi-Examiner is not significantly different from human-generated question sets, suggesting that it has the potential to be an effective support tool for educators, capable of producing question sets that closely match human standards in diversity and cognitive complexity. On the other hand, GPT-4’s limitations are apparent, as it consistently underperforms across all dimensions, particularly in higher-order thinking. This may be due to its lack of specialized knowledge structures and educational evaluation frameworks, which are crucial for generating varied and challenging questions suitable for educational assessments.

These results have important implications for educational practice, demonstrating that tools like Multi-Examiner can significantly enhance the efficiency and quality of question generation, particularly in scenarios where a diverse and comprehensive set of questions is needed. The strong alignment of Multi-Examiner’s performance with that of human-generated methods also suggests its applicability in real-world educational settings, potentially easing the burden on educators. However, the limitations of GPT-4 highlight the need for further development and customization of LLMs tailored to the educational domain to better support diverse question generation. Future research could explore optimizing these AI models to achieve even greater diversity and quality in question generation across various subject areas, ensuring these tools effectively contribute to educational assessment practices.

5.3. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Automated Systems in Generating Higher-Order Thinking Questions in K-12 IT Education (RQ3)

The analysis of the effectiveness of Multi-Examiner in generating higher-order thinking questions shows that it outperforms GPT-4, particularly at the evaluation and creation levels. These results align with prior findings, emphasizing the advantage of integrating knowledge graphs and large language models in improving the quality of complex question generation. The performance gap between Multi-Examiner and human-generated questions is minimal, suggesting the system’s potential as an effective tool for educators, providing support close to human capabilities. In contrast, GPT-4’s limitations are evident, especially in generating questions requiring deep thinking and creativity, highlighting the need for specialized educational frameworks and domain-specific knowledge to enhance its application in educational assessments.

The interaction effect between generation methods and cognitive levels indicates that different methods exhibit varying performance patterns across cognitive levels, reinforcing the importance of tailoring AI models for specific educational contexts. As cognitive levels increase from analysis to evaluation and creation, performance differences become more pronounced, reflecting the challenge of generating higher-order thinking questions. These findings suggest the need for further refinement of AI-based systems, such as Multi-Examiner, to better support K-12 education by effectively generating questions that assess critical and creative thinking skills.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the Multi-Examiner system effectively generates high-quality, higher-order thinking questions for K-12 IT education, outperforming GPT-4 across cognitive levels, especially in evaluation and creation. This highlights the value of integrating knowledge graphs and domain-specific tools to enhance question diversity and complexity, aligning closely with human-crafted quality.

However, limitations like sample size and subjective scoring suggest further research. Expanding to diverse subjects and using objective metrics could strengthen findings. Future studies could also integrate Multi-Examiner with other AI technologies to optimize its educational applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and Z.Y.; methodology, Y.W. and Z.Y.; software, Y.W. and Z.Y.; validation, Z.Y. and Z.W.; formal analysis, Y.W. and Z.Y.; investigation, Y.W., Z.Y. and Z.W.; resources, Z.Y. and Z.W.; data curation, Z.Y. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W., Z.Y. and Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.W., Z.Y. and J.W.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.6217021982).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Applied Psychology at Zhejiang University of Technology (No. 2024D024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; AlSaad, R.; Alhuwail, D.; Ahmed, A.; Healy, P. M.; Latifi, S.; Aziz, S.; Damseh, R.; Alabed, A. S.; Sheikh, J. Large language models in medical education: opportunities, challenges, and future directions; JMIR Medical Education, 2023, 9, 1.

- Shoufan, A. Can students without prior knowledge use ChatGPT to answer test questions? An empirical study; ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abulibdeh, A.; Zaidan, E.; Abulibdeh, R. Navigating the confluence of artificial intelligence and education for sustainable development in the era of industry 4.0: Challenges, opportunities, and ethical dimensions; Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024, 140527.

- Almufarreh, A.; Mohammed, N. K.; Saeed, M. N. Academic teaching quality framework and performance evaluation using machine learning; Applied Sciences, 2023, 13, 5.

- Anderson, L. W.; Krathwohl, D. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s; Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.: USA, 2001.

- Bahroun, Z.; Anane, C.; Ahmed, V.; Zacca, A. Transforming education: A comprehensive review of generative artificial intelligence in educational settings through bibliometric and content analysis; Sustainability, 2023, 15, 17.

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. A survey on evaluation of large language models; ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2024, 15, 3.

- Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Hauff, C.; Houben, G. LearningQ: A LargeScale Dataset for Educational Question Generation; ICWSM, 2018, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Pu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities; World Wide Web, 2024, 27, 4.

- Conklin, J.; Anderson, L. W.; Krathwohl, D.; Airasian, P.; Cruikshank, K. A.; Mayer, R. E.; Pintrich, P.; Raths, J.; Wittrock, M. C. Educational Horizons, 2005, 83(3), 154–159. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42926529.

- Dienichieva, O. I.; Komogorova, M. I.; Lukianchuk, S. F.; Teletska, L. I.; Yankovska, I. M. From reflection to self-assessment: Methods of developing critical thinking in students; International Journal of Computer Science & Network Security, 2024, 24, 7.

- Espartinez, A. S. Exploring student and teacher perceptions of ChatGPT use in higher education: A Q-Methodology study; Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2024, 7, 100264.

- Folk, A.; Blocksidge, K.; Hammons, J.; Primeau, H. Building a bridge between skills and thresholds: Using Bloom’s to develop an information literacy taxonomy; Journal of Information Literacy, 2024, 18, 1.

- Gezer, M.; Oner Sunkur, M.; Sahin, I. F. An evaluation of the exam questions of social studies course according to revised Bloom’s taxonomy; Education Sciences & Psychology, 2014, 28(2).

- Goyal, M.; Mahmoud, Q. H. A systematic review of synthetic data generation techniques using generative AI; Electronics, 2024, 13, 17.

- Graesser, A. C.; Lu, S.; Jackson, G. T.; Mitchell, H. H.; Ventura, M.; Olney, A.; Louwerse, M. M. AutoTutor: A tutor with dialogue in natural language; Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 2004, 36(2), 180–192. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, R.; Pei, S.; Chawla, N. V.; Wiest, O.; Zhang, X. Large language model based multi-agents: A survey of progress and challenges; ArXiv.org, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M. U.; Tashi, A.; Shah, A.; Qureshi, R.; Muneer, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M. B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J. Large language models: A comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects; Authorea Preprints, 2024.

- Haladyna, T. M.; Downing, S. M. Validity of a taxonomy of multiple-choice item-writing rules; Applied Measurement in Education, 1989, 2(1), 51–78. [CrossRef]

- Halkiopoulos, C.; Gkintoni, E. Leveraging AI in e-learning: Personalized learning and adaptive assessment through cognitive neuropsychology—A systematic analysis; Electronics, 2024, 13, 18.

- Han, K.; Gardent, C. Generating and Answering Simple and Complex Questions from Text and from Knowledge Graphs; Hal.science, 2023. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04369868.

- Hang, C. N.; Tan, C. W.; Yu, P.-D. Mcqgen: A large language model-driven mcq generator for personalized learning; IEEE Access, 2024; IEEE.

- Heilman, M.; Smith, N. A. Good Question! Statistical Ranking for Question Generation; In Proceedings of Human Language Technologies: The 2010 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2010, pp. 609–617.

- Hofer, M.; Obraczka, D.; Saeedi, A.; Köpcke, H.; Rahm, E. Construction of knowledge graphs: Current state and challenges; Information, 2024, 15, 8.

- Hwang, K.; Challagundla, S.; Alomair, M.; Chen, L. K.; Choa, F. S. Towards AI-assisted multiple choice question generation and quality evaluation at scale: Aligning with Bloom’s Taxonomy; Workshop on Generative AI for Education, 2023.

- Hwang, K.; Wang, K.; Alomair, M.; Choa, F.; Chen, L. K. Towards Automated Multiple Choice Question Generation and Evaluation: Aligning with Bloom’s Taxonomy; In A. M. Olney, I. Chounta, Z. Liu, O. C. Santos, B. I. Ibert (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Education, Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 389–396.

- Jia, Z.; Pramanik, S.; Saha Roy, R.; Weikum, G. Complex Temporal Question Answering on Knowledge Graphs; In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2021, pp. 792–802. [CrossRef]

- Koenig, N.; Tonidandel, S.; Thompson, I.; Albritton, B.; Koohifar, F.; Yankov, G.; Speer, A.; Jay, Gibson, C.; Frost, C. Improving measurement and prediction in personnel selection through the application of machine learning; Personnel Psychology, 2023, 76, 4.

- Kong, S.-C.; Yang, Y. A human-centred learning and teaching framework using generative artificial intelligence for self-regulated learning development through domain knowledge learning in K–12 settings; IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2024; IEEE.

- Krathwohl, D. R. A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview; Theory into Practice, 2002, 41(4), 212–218. [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, G.; Leo, J.; Parsia, B.; Sattler, U.; AlEmari, S. A Systematic Review of Automatic Question Generation for Educational Purposes; International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 2020, 30(1), 121–204. [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Nissim, M. A survey on automatic generation of figurative language: From rule-based systems to large language models; ACM Computing Surveys, 2024, 56, 10.

- Leite, B.; Cardoso, H. L. Do rules still rule? Comprehensive evaluation of a rule-based question generation system; 2023, pp. 27–38.

- Li, W.; Li, L.; Xiang, T.; Liu, X.; Deng, W.; Garcia, N. Can multiple-choice questions really be useful in detecting the abilities of LLMs?; ArXiv (Cornell University), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Meng, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Tu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Sun, F.; He, K. A survey of knowledge graph reasoning on graph types: Static, dynamic, and multi-modal; IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024; IEEE.

- Liang, W.; Meo, P. D.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, J. A survey of multi-modal knowledge graphs: Technologies and trends; ACM Computing Surveys, 2024, 56, 11.

- Liu, Q.; Han, S.; Cambria, E.; Li, Y.; Kwok, K. PrimeNet: A framework for commonsense knowledge representation and reasoning based on conceptual primitives; In Cognitive Computation, Springer, 2024, pp. 1–28.

- Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ton, J.-F.; Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Cheng, H.; Klochkov, Y.; Taufiq, M. F.; Li, H. Trustworthy LLMs: A survey and guideline for evaluating large language models’ alignment; ArXiv, 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.05374.

- Moore, S.; Schmucker, R.; Mitchell, T.; Stamper, J. Automated generation and tagging of knowledge components from multiple-choice questions; 2024, pp. 122–133.

- Mulla, N.; Gharpure, P. Automatic question generation: A review of methodologies, datasets, evaluation metrics, and applications; Progress in Artificial Intelligence, 2023, 12(1), 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F.; Khalid, M. U.; Ayub, N.; Rasool, A.; Abbas, T.; Afzal, M. W. Automated assessment and feedback in higher education using generative AI; IGI Global, 2024, pp. 433–461.

- Pan, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Unifying large language models and knowledge graphs: A roadmap; IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 2024; IEEE.

- Pan, X.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Hu, Z.; Bao, J. Evolving to multi-modal knowledge graphs for engineering design: State-of-the-art and future challenges; Journal of Engineering Design, 2024, pp. 1–40; Taylor & Francis.

- Paulheim, H. Knowledge Graph Refinement: A Survey of Approaches and Evaluation Methods; Semantic Web, 2016, 8(3), 489–508. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Torchiano, M.; Rizzo, G.; Mihindukulasooriya, N.; Corcho, O. A quality assessment approach for evolving knowledge bases; Semantic Web, 2019, 10, 2.

- Rodrigues, L.; Pereira, F. D.; Cabral, L.; Gašević, D.; Ramalho, G.; Mello, R. F. Assessing the quality of automatic-generated short answers using GPT-4; Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2024, 7, 100248.

- Rodriguez, M. C. Three Options Are Optimal for Multiple-Choice Items: A Meta-Analysis of 80 Years of Research; Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 2005, 24(2), 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Lund, B. D.; Reddy, M. N.; Arshad, M. A.; Hayawi, K.; Ravi, B.; Mannuru, A.; Batool, L. Putting GPT-4o to the sword: A comprehensive evaluation of language, vision, speech, and multimodal proficiency; Applied Sciences, 2024, 14, 17.

- Shuraiqi, A.; Abdulrahman, A. A.; Masters, K.; Zidoum, H.; AlZaabi, A. Automatic generation of medical case-based multiple-choice questions (MCQs): A review of methodologies, applications, evaluation, and future directions; Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 2024, 8, 10.

- Singh, M.; Patvardhan, C.; Vasantha, L. C. Does ChatGPT spell the end of automatic question generation research?; IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fu, W. Exploring synergies between causal models and Large-Language models for enhanced understanding and inference; 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Tahri, C. Leveraging modern information seeking on research papers for real-world knowledge integration applications: An empirical study; 2023.

- Tao, Y.; Viberg, O.; Baker, R. S.; Kizilcec, R. F. Cultural bias and cultural alignment of large language models; PNAS Nexus, 2024, 3, 9.

- Vistorte, A. O. R.; Deroncele-Acosta, A.; Ayala, J. L. M.; Barrasa, A.; López-Granero, C.; Martí-González, M. Integrating artificial intelligence to assess emotions in learning environments: A systematic literature review; Frontiers in Psychology, 2024, 15, 1387089.

- Wang, X.; Yang, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Liang, J.; He, Q.; Gu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W. Knowledgpt: Enhancing large language models with retrieval and storage access on knowledge bases; ArXiv, 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.11761.

- Wei, X. Evaluating ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-4o: Performance insights from NAEP mathematics problem solving; Frontiers Media SA, 2024, 9, 1452570.

- Wong, J. T.; Richland, L. E.; Hughes, B. S. Immediate versus delayed low-stakes questioning: Encouraging the testing effect through embedded video questions to support students’ knowledge outcomes, self-regulation, and critical thinking; Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 2024, pp. 1–36; Springer.

- Wu, S.; Cao, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, R.; Qian, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, W. A comprehensive exploration of personalized learning in smart education: From student modeling to personalized recommendations; ArXiv, 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01666.

- Yenduri, G.; Ramalingam, M.; Chemmalar, S. G.; Supriya, Y.; Srivastava, G.; Kumar, P.; Deepti, R. G.; Jhaveri, R. H.; Prabadevi, B.; Wang, W. GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer)–A comprehensive review on enabling technologies, potential applications, emerging challenges, and future directions; IEEE Access, 2024; IEEE.

- Yu, F.-Y.; Kuo, C.-W. A systematic review of published student question-generation systems: Supporting functionalities and design features; Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 2024, 56, 2.

- Yu, T.; Fu, K.; Wang, S.; Huang, Q.; Yu, J. Prompting video-language foundation models with domain-specific fine-grained heuristics for video question answering; IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, 2024; IEEE.

- Zhang, L.; Jr, C.; Greene, J. A.; Bernacki, M. L. Unraveling challenges with the implementation of universal design for learning: A systematic literature review; Educational Psychology Review, 2024, 36, 1.

- Zhao, R.; Tang, J.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, X. Zero-shot knowledge graph question generation via multi-agent LLMs and small models synthesis; 2024, pp. 3341–3351.

- Zong, C.; Yan, Y.; Lu, W.; Huang, E.; Shao, J.; Zhuang, Y. Triad: A Framework Leveraging a Multi-Role LLM-based Agent to Solve Knowledge Base Question Answering; ArXiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Research Framework of Multi-Examiner Study.

Figure 1.

Research Framework of Multi-Examiner Study.

Figure 2.

System Architecture Processes.

Figure 2.

System Architecture Processes.

Figure 3.

Architecture of Multi-Examiner.

Figure 3.

Architecture of Multi-Examiner.

Figure 4.

Distractor Relevance Scores by Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

Figure 4.

Distractor Relevance Scores by Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

Figure 5.

Interaction Effect Plot of Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

Figure 5.

Interaction Effect Plot of Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

Figure 6.

Parallel Coordinate Plot of Differences in Generation Methods Across Evaluation Dimensions.

Figure 6.

Parallel Coordinate Plot of Differences in Generation Methods Across Evaluation Dimensions.

Figure 7.

Interaction Effect Graph of Generation Methods and Cognitive Levels.

Figure 7.

Interaction Effect Graph of Generation Methods and Cognitive Levels.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Distractor Relevance Scores by Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Distractor Relevance Scores by Generation Method and Knowledge Type.

| Generation Method |

Knowledge Type |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

N |

| Multi-Examiner |

Factual |

4.03 |

1.00 |

30 |

| |

Conceptual |

3.00 |

0.91 |

30 |

| |

Procedural |

3.57 |

0.94 |

30 |

| |

Metacognitive |

3.73 |

0.94 |

30 |

| GPT-4 |

Factual |

3.33 |

0.99 |

30 |

| |

Conceptual |

2.53 |

0.97 |

30 |

| |

Procedural |

2.40 |

1.10 |

30 |

| |

Metacognitive |

3.20 |

0.99 |

30 |

| Human |

Factual |

3.07 |

1.14 |

30 |

| |

Conceptual |

3.63 |

0.81 |

30 |

| |

Procedural |

3.77 |

0.82 |

30 |

| |

Metacognitive |

3.60 |

1.00 |

30 |

Table 2.

Results of Two-Way ANOVA on Distractor Relevance Scores.

Table 2.

Results of Two-Way ANOVA on Distractor Relevance Scores.

Source of

Variation |

Sum of

Squares |

Degrees of

Freedom (DF) |

Mean Square |

F-value |