1. Introduction

Surveys carried out by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki during the last decades on the Island of Lemnos have led to the discovery of a few Epipalaeolithic open-air sites, most of which are located along the eastern coast of the island [

1]. Moreover, the presence of knappable stone outcrops has yielded evidence of local raw material availability and their exploitation during different periods of prehistory [

2].

The Island of Lemnos (presently 475.6 km2) is located in the northeast Aegean Sea, very close to the Anatolian coastline, from which is separated by a sea stretch, maximum 100 m deep and 62 km wide as the crow flies. The most recent reconstruction of the Holocene relative sea-level (RSL) in this Aegean coastal sector located within the South Marmara microplate, are consistent with a continuous RSL rise in the last 6.0 ka BP in the whole NE Aegean Sea [

3]. This agrees with the glacio-hydro-isostatic curves available for the area [

4,

5,

6]. The continuous sea level rise after the Younger Dryas separated Lemnos from the Anatolian mainland, but during the Last Glacial Maximum the island was connected to the western coast of Anatolia [

7,

8], easy to access for to Upper Palaeolithic hunters.

The scope of this paper is to present and discuss an early Upper Palaeolithic Aurignacian knapped stone assemblage [

9] discovered during the surveys carried out in the summers of 2020 and 2021 along the northern coast of the island, some 2 km west of the Bay of Pournias (

Figure 1).

So far, a few Aegean islands have yielded lithic assemblages attributed to different Palaeolithic periods [

10] shedding some light on the Pleistocene peopling of the Aegean [

11,

12]. According to some authors, these finds show that seafaring was practiced during some Palaeolithic periods [

13,

14]. This issue has been widely debated although the Palaeolithic sites are few and mostly undated. In contrast, information regarding sea-level changes is detailed at least for the entire Upper Palaeolithic ([

6] (Fig. 4)). The discovery of an Aurignacian assemblage in Lemnos is intriguing. This cultural aspect, which is related with the spread of the first modern humans towards Europe [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], is badly known in Anatolia [

20,

21] and Greece [

22,

23], as it is in the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula [

24]. This is why the site of Pournias plays an important role in the Pleistocene archaeology of the Aegean and south Europe in general.

2. The Pournias Site

The Palaeolithic open-air site of Pournias is located ca 93 m from the present shoreline. It lies in an area of Holocene sand dunes ([

25] (XII fig. 1)) which are partly fixed by a sparse vegetation (

Figure 2 top). Pournias is one of the several sites and scatters of lithic materials of different ages discovered along the northern coast of Lemnos during the 2020-2022 surveys conducted by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, whose purpose was to discover new traces of prehistoric peopling on the island.

The site was exposed during the construction of a parking place and an earth road that from the interior takes to the beach. On this occasion the topmost part of the sand dune was partly removed with a bulldozer revealing the presence of a reddish-brown paleosol with a cluster of knapped stone artefacts which was discovered during the June 2020 surveys. The coordinates of the central point of the concentration of artefacts, which extends in southwest-northeast direction over a surface of ca 25x10 m, are 39°57'31.40"N, 25°16'11.97"E, the altitude is 6 m a.s.l.

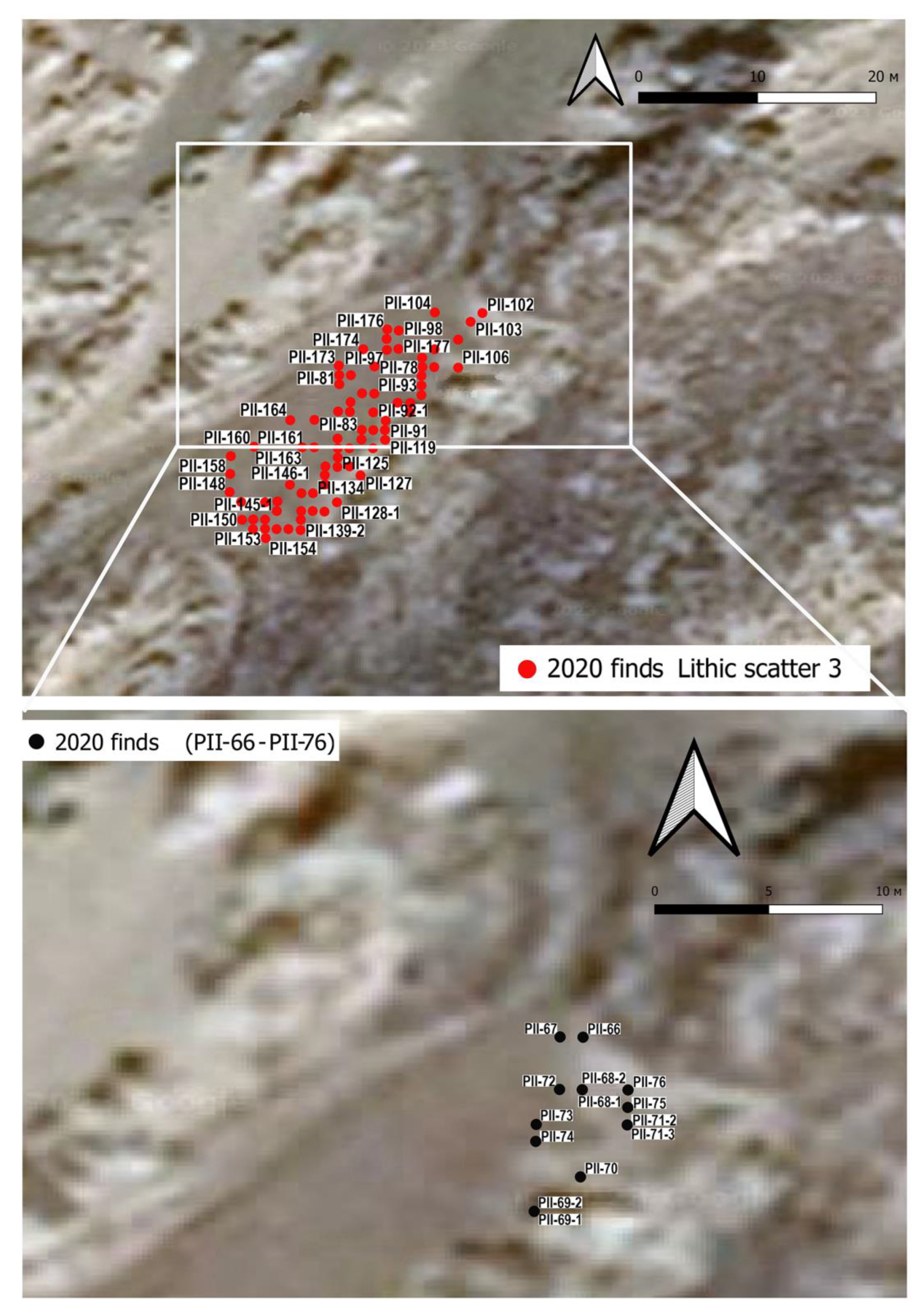

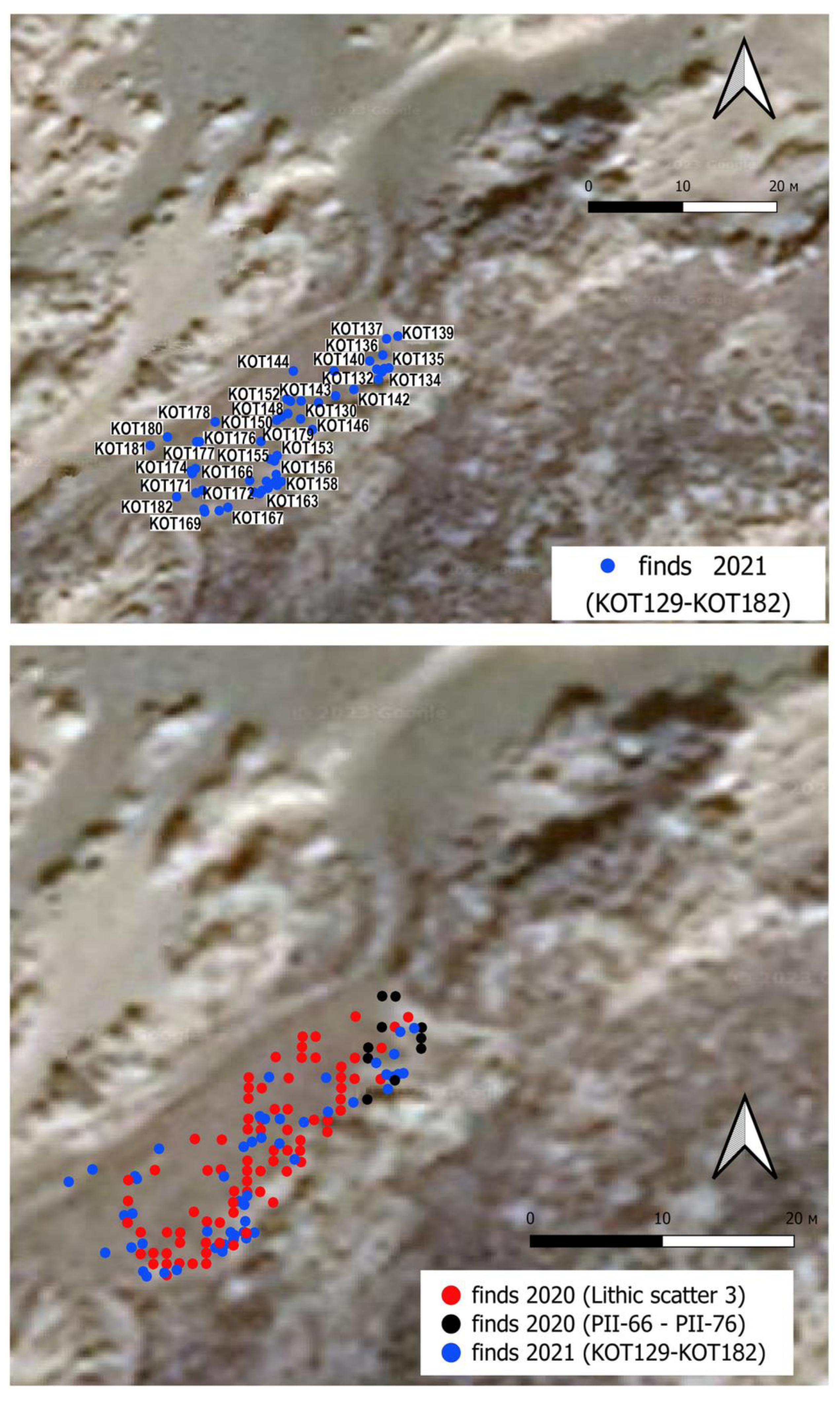

Two seasons of surface collection were carried out in 2020 and 2021 (

Figure 3). Each artefact has been precisely positioned with the aid of a GPS and numbered in sequence (see Supplementary Material,

Table S1). Data were then incorporated into a QGIS software for spatial analysis. It was thus possible to build high resolution distribution maps (

Figure 4 and 5) which suggest the presence of a dense lithic cluster and a potential site [

26,

27].

Most lithics were recovered lying flat on the exposed east-west inclined surface of the sandy soil (

Figure 2 bottom). The distribution maps show the concentration of all knapped stones collected in the two fieldwork seasons (

Figure 5 bottom). Unfortunately, no other artefacts such as bone tools or organic material like faunal remains, mollusks or charcoals have been found in association to lithics. Some artefacts were probably slightly moved when the surface of the dune was removed. However, it seems that they have only recently been exposed due to the erosion of the soil covering them caused by the rain. The site has never been test-trenched or excavated so far. Besides the concentration of lithic artefacts, one isolated end scraper (KOT000:

Figure 9) was collected during a visit paid in September 2022 a few meters north of the site. Its coordinates were taken with a Garmin GPS (39°57'33.5"N - 25°16'14.0"E: Supplementary materials

Table S1). This find shows that the site most probably originally extended beyond the present exposed surface and part of it may be still buried beneath the sand dunes. Considering the scarcity of information regarding the Upper Palaeolithic peopling of this part of the Aegean, we believe that it is important to report the discovery of this assemblage to the scientific community.

The collected artefacts were later stored and studied at the Myrina Archaeological Museum.

3. Materials and Methods

During the different fieldwork years, the lithic finds were labelled respectively with the prefixes PII (i.e. Pournias II, site 3, 2020 season) and KOT (i.e. Kotsinas, 2021 season). The PII collection covers artefacts from #65 to #177 and KOT from #129 to #182 for a total of 185 pieces weighing 825.27 gr.

A preliminary analysis of the knapped stone artefacts suggests that Pournias is a homogeneous complex. The artefacts have been classified according to the typological lists available for the European Upper Palaeolithic [

28,

29,

30].

The assemblage consists of 185 artefacts which, in quantitative descending order, are made of chalcedony, a hydrothermal siliceous rock (175: 94.6%), radiolarite (6: 3.3%), radiolarian chert (2: 1.1%), chert (1: 0.5%), and limestone (1: 0.5%) (Supplementary materials:

Table S1).

All these raw materials are available within a radius of ca 15 km from the site [

1]. Chalcedony, which represents the most employed raw material for making artefacts in this complex can be found in the volcanic formations of the island, while radiolarites and radiolarian cherts pebbles are common in the coarser sedimentary formations, among which are the Ifestia Unit Conglomerates [

1,

31].

The occurrence of chalcedony was confirmed by combining optical observations at the stereomicroscope and Raman spectroscopy (see Supplementary material/Appendix 1 and

Figures S1 and S2).

At present, hydrothermal alteration areas in Lemnos are located in the western part of the island, the Fakos Peninsula, Sardes, Roussopouli and Paradeisi Hill [

32]. In the latter locality, the outcropping raw material is well visible at the top of the small valley upstream from the Havouli beach. It was employed for the manufacture of threshing sledge inserts by local farmers until the 1960s ([

1], (Fig. 2)), ([

2], (Fig. 10)).

3. Results

Only 47 (25.40%) artefacts are complete, 138 (74.60%) are heavily weathered, damaged or fragmented. As reported above, most of the surface weathering is due to the salty environment. In some cases, salt needle crystals are forming on the artefact surface after collection (see KOT163,

Figure 9).

The retouched pieces are represented by 39 (21.08%) end scrapers (1 long, 11 short, 3 semi-circular and 24 carinated, 1 of which is nosed, 2 are on tablets:

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), 5 side or transversal scrapers and 1 bilateral backed bladelet (or point?) obtained with abrupt, deep, direct, continuous retouch on both sides (PII-165-1:

Figure 6) and 1 bladelet with straight sides and trapezoidal cross-section (PII-136-1:

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: bladelet (PII-136-1), bilateral backed bladelet (PII-165-1), proximal blade fragments (PII-159 and KOT181), twisted bladelet (KOT1325) and carinated end scrapers (PII-128-1, KOT136 and KOT156). For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 6.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: bladelet (PII-136-1), bilateral backed bladelet (PII-165-1), proximal blade fragments (PII-159 and KOT181), twisted bladelet (KOT1325) and carinated end scrapers (PII-128-1, KOT136 and KOT156). For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 7.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: different types of carinated end scrapers. For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 7.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: different types of carinated end scrapers. For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 8.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: different types of end scrapers. For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 8.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: different types of end scrapers. For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 9.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: carinated end scrapers (PII-146-1 and KOT000), carinated end scrapers on

tablette (PII-139-1 and PII-140-1),

tablette (PII-173),

cornice (KOT182) and microflakelet with salt needle crystals (KOT163). For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

Figure 9.

Pournias: knapped stone artefacts: carinated end scrapers (PII-146-1 and KOT000), carinated end scrapers on

tablette (PII-139-1 and PII-140-1),

tablette (PII-173),

cornice (KOT182) and microflakelet with salt needle crystals (KOT163). For details see

Table S1 (Photographs by E. Starnini).

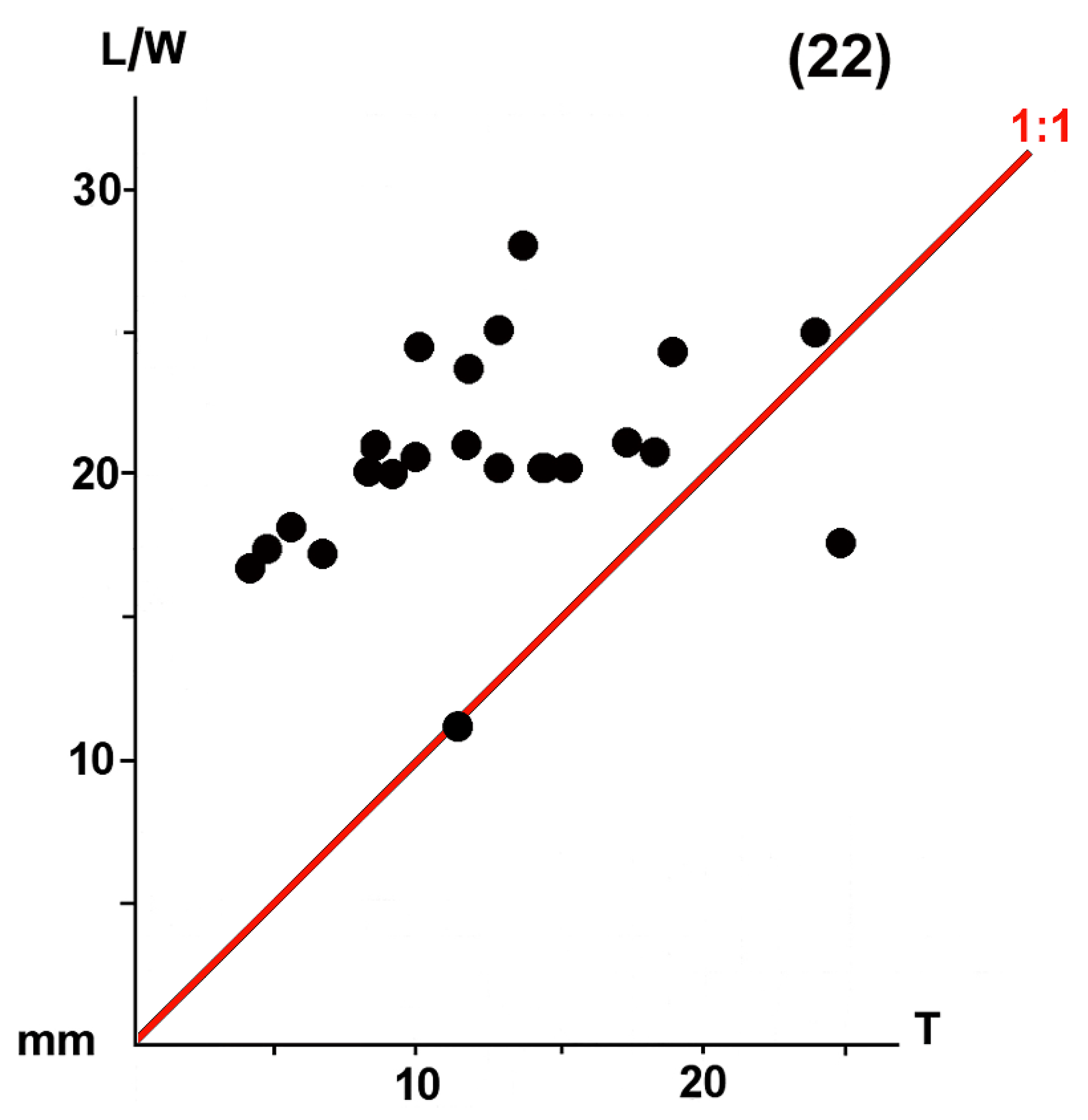

The length/width-thickness diagram of the complete end scrapers shows the high percentage of carinated specimens (

Figure 10).

The technical pieces consist of 1 core rejuvenation flakelet (PII-135), 2 tablets (PII-146 and PII-173), 2 carinated end scrapers on tablets (PII-139-1 and PII-140-1) and 1 cornice (KOT182) (

Figure 9). There are 8 cores (1 remnant piece: KOT136) and 1 raw material chunk (PII-137). Most probably 3 carinated end scrapers were first exploited as cores to detach microbladelets (see [

33]). One complete, unretouched red radiolarite bladelet 1 is twisted (KOT135:

Figure 6), as is 1 twisted microflakelet (KOT134), which are characteristic of the Aurignacian debitage [

34] (p. 14). Most unretouched artefacts are fragmented. They consist of microflakelets (71: 66.89%), flakelets (30: 28.30%), microbladelets (3: 2.84%) and bladelets (2: 1.88%), following the nomenclature proposed by G. Laplace [

28]. The presence of cores, 1 raw material chunk, and technical pieces suggests that the artefacts were manufactured within or very close to the site exploiting raw material collected from sources available within one day’s walk [

1] (pp. 26–27). Most probably, one of the possible collection areas were beaches, since a few pieces show a neocortical part with characteristic beach pebble scars [2 (Fig. 2, d)]. A few artefacts show a flat, inclined butt, a characteristic that fits into the general picture of the early Upper Palaeolithic knapping technology [

35].

According to the categories proposed by F. Martini [

29], the Pournias end scrapers can be classified as hyper-carinated (3: 13.63%), carinated (9: 40.90%), sub-carinated (4: 18.18%), flat (4: 18.18%) and very flat (2: 9.09%). The three classes of more or less carinated specimens (16 out of 22 complete pieces) predominate.

The techno-typological characteristics of the knapped stone artefacts, which are represented by a high percentage of carinated end scrapers [

36] (p. 55), some of which were primarily exploited as cores for the production of microbladelets, a few fragments of twisted bladelet and microbladelets, flat, oblique butts, the employment of the percussion technique, homogeneous state of preservation, weathering and white patina, suggest that they form a coherent cluster. Furthermore, given the impossibility of obtaining radiocarbon dates, the chronology of the lithic assemblage can be suggested only comparing its techno-typological characteristics. For example, some carinated end scrapers (PII-81, PII-104, PII-91:

Figure 7) resemble the so-called

nucleus-burin caréné or

nucleus-grattoir ([

30] (Fig. 15)) which are typical of many European Aurignacian complexes. The characteristic

débitage bladelet products detached from 2-to-3 cm wide carinated “end scrapers” is not represented in the Pournias assemblage [

37]. In contrast, several end scrapers on core

tablette (KOT178, KOT160, KOT172, KOT171:

Figure 8) reproduce the

semi-tournant laminar operating scheme of the early Aurignacian ([

37] (Fig. 17)). Therefore, based on these common typo-technological characteristics shared with other Aurignacian assemblages in Europe, the site of Pournias can be attributed with good confidence to a period of development of the Aurignacian culture, an aspect that is poorly represented in the Aegean in general [

23] and so far, unknown in the Aegean islands [

38].

4. Discussion

The Aurignacian is the first techno-complex related to Anatomically Modern Humans, which “is not a pan-European cultural event with a single point of origin” [

39] (p. 252). Studies show that Aurignacian groups made their appearance around 43-42 kyr cal BP and dispersed rapidly in Europe during the Upper Palaeolithic. It is becoming increasingly clear that the events that took place between 45,000 and 35,000 BP are very difficult to interpret due to the scarcity of dated human remains and the complexity of the so-called “transitional period” [

9,

40]. Recent studies show that Aurignacian techno-complexes made their appearance roughly around 41-40,000 BP in the Balkans [

41] and that they dispersed rapidly during the Upper Palaeolithic, although the entire process is not yet well understood [

18,

37]. Conventionally, the Aurignacian is divided into the Proto, Early, Evolved and Late, though the techno-typological and chronological differences between the first two periods are difficult to distinguish and far from being fully understood [

18,

42,

43].

In Greece, Aurignacian and early Upper Palaeolithic sites are few [

44] (p. 13). Some are cave sequences (Franchthi, Klisoura and Kolominitsa). Open-air sites are known in Epirus at Megalo Karvounari and Spilaion. From the first Ligkovanlis [

45] has reported an Aurignacian component, while the assemblage from the second is represented by carinated end scrapers and burins, though Dufour bladelets are absent [

46] (pp. 138-146). Another open-air surface site is Eleochori, in Achaïa, extending over a surface of ca 6-7000 sq meters. The site, disturbed by farming, yielded characteristic Aurignacian artefacts among which are carinated end scrapers, dihedral burins and Mousterian Levallois pieces too [

47].

The discovery of a concentration of knapped stone artefacts at Pournias contributes to the knowledge of the Aurignacian in southeast Europe and the Aegean in particular. We know that in an advanced period of the last glacial maximum (LGM), during the first half of the MIS-3, the sea was ca -60 m below that of the present and it dropped to ca -80 m during the second half [

48] (p. 23), [

8,

49], which is the period of our interest when the Aurignacian culture developed. The Pournias assemblage is not radiocarbon dated, due to the absence of organic material. However, the techno-typological characteristics of the lithic assemblage suggest that the site was settled roughly during this period when the island was part of the Anatolian Peninsula ([

50] (Fig. 3)).

According to the available radiocarbon chronology, the Aurignacian period in Greece covers a long time span. This is suggested by the dates available from Klisoura (Klissoura) [

22] and Franchthi [

23], two caves which open in different regions of Argolis (Peloponnese). The Early and Middle Aurignacian sequence of Klisoura has been radiocarbon dated between ca 33,000 and 31,000 BP [

51]. Considering the full picture of the Aurignacian radiocarbon chronology of the two caves, the entire cultural aspect developed roughly between 41,080±390 BP (OxA-21070 from marine shell at Franchthi) and 15,490±410 BP (Gd-10701 from charcoal at Klisoura), even though the latter result seems too recent. Another site is the Kolominitsa Cave, which opens in the Mani Peninsula (south Peloponnese) where a probable Aurignacian occupation has been dated between 34,150±280 BP (Beta-333516) and 33,870±550 BP (Beta-193416) from charcoal ([

52] (Table 7.5)).

The situation is quite similar in neighboring Albania where a few open-air and cave sites have been discovered and partly excavated. Only one radiocarbon date is available from the Blazi Cave (COL1958.1.1: 40,713±827 BP: [

53] (Table 1)). The lithic assemblage from the open-air site of Shën Mitri consists of carinated end scrapers and microbladelets, but simple burins and Dufour bladelets are absent. According to the excavators, the knapped stone assemblage from Shën Mitri can be chrono-typologically compared with that recovered from the early Aurignacian horizons of the Klisoura cave [

53] (p. 158).

Moving east, our knowledge of the early Upper Palaeolithic along the Mediterranean coastline is limited to the Karain cave sequence in the interior of the Gulf of Antalya [

21].

5. Conclusions

Lemnos is one of the few north Aegean islands to have yielded an impressive number of prehistoric sites and artefacts covering a wide cultural and chronological spectrum from the Middle Palaeolithic [

1] to the end of the Bronze Age [

54,

55,

56]. Thanks to the results of research carried out over the last three decades, the island has shown considerable potential also for the study of the events that took place around the beginning and the end of the LGM and its connections with the Anatolian Peninsula and the Balkans during this period.

Following the techno-typological characteristics of the Pournias assemblage, and its location in south Europe, we can suggest that the site can be attributed either to the Early or Middle Aurignacian, according to the subdivision proposed by J.A. Svoboda for the Danube region [

57]. The presence of the Pournias concentration of lithics poses a few important questions to solve, among which are: 1) the itineraries followed by Aurignacian hunters moving northwest, 2) the presence of other Palaeolithic sites in this part of the Aegean, and 3) the reason why an early Upper Palaeolithic community settled in the present Pournias region. To answer the first question, we must consider that we still know very little about this problem. This is made evident by the scarcity of data, which has only slightly improved during the last decades [

58], and the absence of early Upper Palaeolithic sites in the entire Anatolian Peninsula [

59]. This fact makes the discovery of the Pournias site very important. The waters of this part of the Aegean, where Lemnos is located, are low. For sure a wide territory was exposed during the MIS-3 around the island. Consequently, we can suggest that many Palaeolithic sites are now underwater, difficult though not impossible to detect [

60,

61]. Moreover, we know very little about the presence and circulation of knappable raw material along the western coast of Anatolia [

62,

63]. We can suggest that Aurignacian hunters were attracted to the Pournias territory due to the presence of rich hydrothermal siliceous rocks and radiolarite outcrops available in its surroundings.

To conclude, the discovery of an Aurignacian assemblage on the island of Lemnos is an important event that may contribute to the improvement of knowledge of the distribution and movement of Aurignacian hunters during the early Upper Palaeolithic in southern Europe.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Pournias: list and description of the lithic artefacts studied; Figure S1: stereomicroscope view of the chalcedony sample; Figure S2: Compared chalcedony and quartz Raman spectra; Appendix S1: Raman measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B., E.S., Y.A. and N.E.; methodology, P.B., E.S.; formal analysis, P.B., E.S. Y.A., N.C., R.C.; investigation, N.C., R.C.; resources, N.E.; data curation, Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., E.S.; writing—review and editing, P.B., E.S., Y.A., N.E., N.C., R.C.; supervision, N.E.; project administration, N.E.; funding acquisition, N.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Secretariat General of the Aegean and Island Policy of the Greek Ministry of Maritime Affairs, Islands and Fisheries, granted to N.E.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results and dataset generated during the study can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The Authors are grateful to Dr Pavlos Triantafyllidis Director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lesbos and Lemnos (Greece) for the permissions and support offered to our research. Thanks are due also to the staff of the Archaeological Museum of Lemnos in Myrina which hosted us during the study of the lithic artefacts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Efstratiou, N.; Biagi, P.; Starnini, E.; Kyriakou, D.; Eleftheriadou, A. Agia Marina and Peristereònas: Two Epipalaeolithic sites in the Island of Lemnos (Greece). Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 2022, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstratiou, N.; Biagi, P.; Starnini, E. The Epipalaeolithic Site of Ouriakos on the Island of Lemnos and its Place in the Late Pleistocene Peopling of the East Mediterranean Region. Adalya 2014, XVII, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vacchi, M.; Rovere, A.; Chatzipetros, A.; Zouros, N.; Firpo, M. (). An updated database of Holocene relative sea level changes in NE Aegean Sea. Quaternary International 2014, 328-329, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Purcell, A. Sea-level change in the Mediterranean Sea since the LGM: model predictions for tectonically stable areas. Quaternary Science Reviews 2005, 24, 1969–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K. Sea-level change and shore-line evolution in Aegean Greece since Upper Palaeolithic time. Antiquity 1996, 70, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Rouby, H.; Purcell, A.; Sun, Y.; Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. PNAS 2014, 111, 15296–15303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykoussis, V. Sea-level changes and shelf break prograding sequences during the last 400ka in the Aegean margins: Subsidence rates and palaeogeographic implications. Continental Shelf Research 2009, 29, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukousioura, O.; Kouli, K.; Gkouma, M.; Theocharidis, N.; Ntinou, M.; Chalkioti, A.; Dimou, V.-G.; Fatourou, E.; Navrozidou, V.; Kafetzidou, A.; Tsourlos, P.; Elina Aidona, E.; Avramidis, P.; Vouvalidis, K.; Syrides, G.; Efstratiou, N. Reconstructing the Environmental Conditions in the Prehistoric Coastal Landscape of SE Lemnos Island (Greece) Since the Late Glacial. Water 2025, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yosef, O. Defining the Aurignacian. In Towards a definition of the Aurignacian, Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25-30, 2002, Bar-Yosef, O., Zilhão, J., Eds., Trabalhos de Arqueologia 2006, 45, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Galanidou, N. Advances in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic archaeology of Greece for the new millennium. Pharos 2014, XX, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanidou, N.; Cole, J.; Iliopoulos, G.; McNabb, J. East meets West: the Middle Pleistocene site of Rodafnidia on Lesvos, Greece. Antiquity Project Gallery 2013, 087, http. [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariou, D.; Galanidou, N. Aegean Pleistocene Landscapes Above and Below Sea-Level: Palaeogeographic Reconstruction and Hominin Dispersals. In Under the Sea: Archaeology and Palaeolandscapes of the Continental Shelf; Bailey, G., Harff, J., Sakellariou, D., Eds.; Springer Cham. 2017; pp. 335–359. [CrossRef]

- Howitt-Marshall, D.; Runnels, C. Middle Pleistocene sea-crossings in the eastern Mediterranean? Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 2016, 42, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A.H. Stone Age Sailors. Paleolithic Seafaring in the Mediterranean. Routledge, New York, 2016.

- Hoffecker, J.F. The Spread on Modern Humans in Europe. PNAS 2009, 106, 16040–16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, J.A.; Benedetti, M.B.; Talamo, S.; Bicho, N.; Cascalheira, J.; Ellis, M.G.; Carvalho, M.M.; Fried, L.; Pereirai, T.; Zinsious, B.K. The early Aurignacian dispersal of modern humans into westernmost Eurasia. PNAS 2020, 117, 25414–25422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Limberg, H.; Klein, K.; Wegener, C.; Schmidt, I.; Weniger, G-C. ; Hense, A.; Rostami, M. Human-existence probability of the Aurignacian techno-complex under extreme climate conditions. Quaternary Science Reviews 2021, 263, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wegener, C.; Klein, K.; Schmidt, I.; Weniger, G-C. Reconstruction of human dispersal during Aurignacian on pan-European scale. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; McLin, S.; Wöstehoff, L.; Ciornei, A.; Gennai, J.; Marreiros, J.; Doboş, A. Aurignacian dynamics in Southeastern Europe based on spatial analysis, sediment geochemistry, raw materials, lithic analysis, and use-wear from Românești-Dumbrăvița. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 14152. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, J.K.; Otte, M. The Formation of the Aurignacian in Europe. Journal of Anthropological Research 2000, 56, 513–534. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçinkaya, I.; Otte, M. Début du Paléolithique supérieur à Karain (Turquie). L'Anthropologie 2000, 104, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Koumouzelis, M.; Ginter, B.; Kozłowski, J.; Pawlinowski, M.; Bar-Yosef, O.; Albert, R.-M.; Litynska-Zajac, M.; Stworzewicz, E.; Wojtal, P.; Lipecki, G.; Tomek, T.; Bochenski, Z.; Pazdur, A. The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Greece: The Excavations in Klisoura Cave. Journal of Archaeological Science 2001, 28, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douka, K.; Perlès, C.; Valladas, H.; Vanhaeren, M.; Hedges, R.E.M. Franchthi Cave revisited: the age of the Aurignacian in south-eastern Europe. Antiquity 2011, 85, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, J.K. The Problem of Cultural Continuity between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic in Central and Eastern Europe. In The Geography of Neandertals and Modern Humans in Europe and the Greater Mediterranean; Bar-Yosef, O., Pilbeam, D., Eds.; Peabody Museum Bulletin 2000, 8, Harvard University; pp. 77-108.

- Sidiropoulou, M.; Fouache, E.; Pavlopoulos, K.; Triantaphyllou, M.; Vouvalidis, K.; Syrides, G.; Greco, E. Geomorphological Evolution and Paleoenvironment Reconstruction in the Northeastern Part of Lemnos Island (North Aegean Sea). Aegaeum 2014, 37, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, C. J. The value, meaning and protection of lithic scatters. Lithics 2011, 32, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Runnels, C.; Karimali, E.; Cullen, B. Early upper Palaeolithic Spilaion: an artifact-rich surface site. In Landscape Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece I; Wiseman, J., Zachos, K., Eds., Hesperia Supplement 32, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Athens, 2003, 135–156.

- Laplace, G. Essai de typologie systématique. Annali dell’Università di Ferrara 1964, new series XV, supplement II to volume I, 1–85.

- Martini, F. L’Epigravettiano di Poggio alla Malva (Firenze). Atti della Società Toscana di Scienze Naturali, Memorie 1981, 88, 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bruns-Ricalens, F. Chronique d’une reconnaissance attendue. Outils “carénés”, outils “nucléiformes” : nucléus à lamelles. Bilan après un siècle de recherches typologiques, technologiques et tracéologiques. Productions lamellaires attribuées à l’Aurignacien : Chaînes opératoires et perspectives technoculturelles. In XIVe congrès de l‘UISPP, Liège 2-8 Septembre 2001. ArchéoLogiques 2005, 1, 23–72. [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti, F.; Manetti, P.; Mazzuoli, R.; Pertusati, P.; Fytikas, M.; Kolios, N.; Vougioukalakis, G.E.; Androulakakis, N.; Critelli, S.; Caracciolo, L. Geological map (scale 1: 50,000) of Limnos Island (Greece): Explanatory notes. Acta Vulcanologica 2009, 21, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Anifadi, A.; Parcharidis, Is.; Sykioti, O. Hydrothermal alteration zones detection in Limnos Island, through the application of Remote Sensing, Proceedings of the 14th International Congress, Thessaloniki, May 2016. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece 2016, L, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, G. Extracting the “Proto” from the Aurignacian. Distinct Production Sequences of Blades and Bladelets in the Lower Aurignacian Phase of Siuren I, Units H and G (Crimea). Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 2016, 25, 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, O. Defining the Aurignacian. In Towards a definition of the Aurignacian; Bar-Yosef, O., Zilhão, J., Eds.; Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25-30, 2002. Trabalhos de Arqueologia 2006, 45, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gennai, J.; Peresani, M.; Richter, J. Blades, bladelets or blade(let)s? Investigating early Upper Palaeolithic technology and taxonomical considerations. Quartär 2021, 68, 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Laplace, G. Recherches sur l'origine et l'évolution des complexes leptolithiques. Publications de l'École française de Rome 1966, 4(1), https://www.persee.fr/doc/efr_0000-0000_1966_mon_4_1.

- Teyssandier, N. Les débuts de l’Aurignacien dans leur cadre européen : où en est-on ? [The beginnings of the Aurignacian in a European framework: where do we stand? Gallia Préhistoire 2023, 63, Varia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.; Daniel, A.; Contreras, D.A.; Holcomb, J.; Mihailović, D.A.; Karkanas, P.; Guérin, G.; Taffin, N.; Athanasoulis, D.; Lahaye, C. Earliest occupation of the Central Aegean (Naxos), Greece: Implications for hominin and Homo sapiens’ behavior and dispersals. Science Advances 2019, 5, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Teyssandier, N.; Bolus, M.; Conard, N. The Early Aurignacian in central Europe and its place in a European perspective. In Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Bar-Yosef, O., Zilhão, J., Eds.; Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25-30, 2002. Trabalhos de Arquelogia 2006, 45, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, S.L.; Brantingham, P.J.; Kerry, K.W. The Early Upper Palaeolithic and the Origin of Modern Humans. In The Early Upper Palaeolithic beyond Western Europe. Brantingham, P.J., Kuhn, S.L., Kerry, K.W., Eds., 2004, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: pp. 242–248.

- Kozłowski, J.K. A dynamic view of Aurignacian technology. In Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Bar-Yosef, O., Zilhão, J., Eds.; Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25-30, 2002. Trabalhos de Arquelogia 2006, 45, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, T.; Wood, R.; Moreau, L.; Conard, N.; Ramsey, C.B. Comments on ’Human-climate interaction during the early Upper Paleolithic: testing the hypothesis of an adaptive shift between the Proto-Aurignacian and the early Aurignacian’ by Banks et al. Journal of Human Evolution 2013, 65, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssandier, N.; Zilhão, J. On the entity and antiquity of the Aurignacian at Willendorf (Austria): implications for modern human emergence in Europe. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 2018, 1, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourloukis, V.; Harvati, K. The Palaeolithic record of Greece: A synthesis of the evidence and a research agenda for the future. Quaternary International 2017, 446, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligkovanlis, S. Megalo Karvounari Revisited. In Thesprotia Expedition II. Environment and Settlement Patterns; Forsén B., Tikkala, E., Eds.; Papers and Monographs of the Finnish Institute at Athens 2011, XVI, 159–180.

- Runnels, C.; Karimali, E.; Cullen, B. Early upper Palaeolithic Spilaion: an artifact-rich surface site. In Landscape Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece I; Wiseman, J., Zachos, K., Eds.; Hesperia Supplement 32, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Athens, 2003, 135–156.

- Darlas, A. Palaeolithic Research in Western Achaïa. In The Palaeolithic Archaeology of Greece and Adjacent Areas. Bailey, G., Adam, E., Panagopoulou, E., Perlès, C., Zagros, C., Eds.; Proceedings of the ICOPAG Conference, Ioannina. British School at Athens Studies 3, 1999, 303-310.

- Siddall, M. , Rohling, E.J., Thompson, W.G. & Waelbroeck, C. Marine isotope stage 3 sea level fluctuations: Data synthesis and new outlook. Reviews of Geophysics 2008, 46, RG4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.; Rovere, A.; Fontana, A.; S. Furlani, S.; Vacchi, M.; Inglis, R.H.; Galili, E.; Antonioli, F.; Sivan, D.; Miko, S.; Mourtzas, N.; Felja, I.; Meredith-Williams, M.; Goodman-Tchernov, M.; Kolaiti, E.; Anzidei, M.; Gehrels, R. Late Quaternary sea-level changes and early human societies in the central and eastern Mediterranean Basin: An interdisciplinary review. Quaternary International 2017, 449, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkioti, A. Reconstructing the Coastal Configuration of Lemnos Island (Northeast Aegean Sea, Greece). In Géoarchéologie Des îles De La Méditerranée; Ghilardi, M., Ed.; CNRS Éditions, Paris, 2016, pp. 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, S.L.; Pigati, J.; Karkanas, P.; Koumouzelis, M.; Kozłowski, J.K.; Ntinou, M.; Stiner, M.C. Radiocarbon dating results for the early Paleolithic of Klissoura Cave. Eurasian Prehistory 2010, 7, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Darlas, A.; Psathi, E. The Middle and Upper Paleolithic on the Western Coast of the Mani Peninsula (Southern Greece). In Harvati, K., Roksandic, M., Eds.; Paleoanthropology of the Balkans and Anatolia Human Evolution and its Context. Springer Science+Business Media, Dordrecht, 2016, pp. 95–117.

- Hauck, T.C.; Ruka, R.; Gjipali, I.; Richter, J.; Vogels, O. Recent discoveries of Aurignacian and Epigravettian sites in Albania. Journal of Field Archaeology 2016, 41, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabò Brea, L. Poliochni II.1, II.2. Città preistorica nell'isola di Lemnos. Monografie della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente, 2; Bretschneider: Rome, 1976.

- Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Firkasis, N.; Tsourou, T.; Vassilakis, E.; Spyrou, E.; Koukousioura, O.; Oikonomou, A.; Skentos, A. “Geo-Archaeo-Routes” on the Island of Lemnos: The “Nalture” Experience as a Holistic Geotouristic Approach within the Geoethical Perspective. Geosciences 2023, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menelaou, S.; Kouka, O.; Müller, N.S.; Kiriatzi, E. Longevity, creativity, and mobility at the “oldest city in Europe”: ceramic traditions and cultural interactions at Poliochni Lemnos, northeast Aegean. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 2024, 16, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J.A. The Aurignacian and after: chronology, geography and cultural taxonomy in the Middle Danube region. In Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25-30, 2002; Bar-Yosef, O., Zilhão, J., Eds. Trabalhos de Arquelogia 2006, 45, 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, O.; Pilbeam, D. Afterword. In The Geography of Neandertals and Modern Humans in Europe and the Greater Mediterranean; Bar-Yosef, O., Pilbeam, D., Eds.; Harvard University, Peabody Museum Bulletin 2000, 8, 183–187.

- Kuhn, S.L.; Stiner, M.C.; Güleç, E. Initial Upper Palaeolithic in south-central Turkey and its regional context: A preliminary report. Antiquity 1999, 73, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøn, O. Hermand, J-P. Settlement archaeology under water. Practical, strategic and research perspective. IEEE/OES Acoustics in Underwater Geosciences Symposium (RIO Acoustics), 2015. [CrossRef]

- Grøn, O.; Boldreel, L.O.; Smith, M.F.; Joy, S.; Tayong Boumda, R.; Mäder, A.; Bleicher, N.; Madsen, B.; Cvikel, D.; Nilsson, B.; Sjöström, A.; Galili, E.; Nørmark, E.; Hu, C.; Ren, Q.; Blondel, P.; Gao, X.; Stråkendal, P.; Dell’Anno, A. Acoustic Mapping of Submerged Stone Age Sites—A HALD Approach. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, S. The Chipped Stone Industry of Aktopraklık C (Bursa). Preliminary Results. Anatolia antiqua. Eski Anadolu 2011, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Atakuman, C.; Erdoğu, B.; Gemici, H.C.; Baykara, I.; Karakoç, M.; Biagi, P.; Starnini, E.; Guilbeau, D.; Yücel, N.; Turan, D.; Dirican, M. Before the Neolithic in the Aegean: The Pleistocene and the Early Holocene record of Bozburun - Southwest Turkey. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 2022, 17, 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).