Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

Review of the dPDT Procedure

Review of Current Evidence

Comparison of dPDT with cPDT

Comparison of dPDT with Other Treatments Modalities and Combinations of Treatments

Significance of Field Cancerization Treatment

Discussion

Limitations of the Review

Suggestions for Future Research

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Figueras Nart I, Cerio R, Dirschka T, Dréno B, Lear JT, Pellacani G, et al. Defining the actinic keratosis field: a literature review and discussion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, 544–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner RN, Sammain A, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, Stockfleth E, Nast A. The natural history of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013, 169, 502–18. [Google Scholar]

- Malvehy J, Stratigos AJ, Bagot M, Stockfleth E, Ezzedine K, Delarue A. Actinic keratosis: Current challenges and unanswered questions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024, 38 (Suppl. S5), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kandolf L, Peris K, Malvehy J, Mosterd K, Heppt M V, Fargnoli MC, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, epithelial UV-induced dysplasia and field cancerization on behalf of European Association of Dermato-Oncology, European Dermatology Forum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024, 38, 1024–47.

- Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, Luque C, Eide MJ, Bingham SF. Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer 2009, 115, 2523–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks R, Rennie G, Selwood TS. Malignant transformation of solar keratoses to squamous cell carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 1988, 1, 795–7.

- Gupta AK, Paquet M, Villanueva E, Brintnell W. Interventions for actinic keratoses. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2012, 12, CD004415. [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri D, Ramchatesingh B, Lagacé F, Iannattone L, Netchiporouk E, Lefrançois P, et al. Pharmacological Agents Used in the Prevention and Treatment of Actinic Keratosis: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Masferrer L, Gracia Cazaña T, Bernad Alonso I, Álvarez-Salafranca M, Almenara Blasco M, Gallego Rentero M, et al. Topical Immunotherapy for Actinic Keratosis and Field Cancerization. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Shah MA, Feldman SR. Reasons for Patient Call-backs while being Treated with Topical 5-fluorouracil: A Retrospective Chart Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2023, 16, 53–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegell SR, Fredman G, Andersen F, Bjerring P, Paasch U, Hædersdal M. Pre-treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil increases the efficacy of daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses - A randomized controlled trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2024, 46, 104069. [Google Scholar]

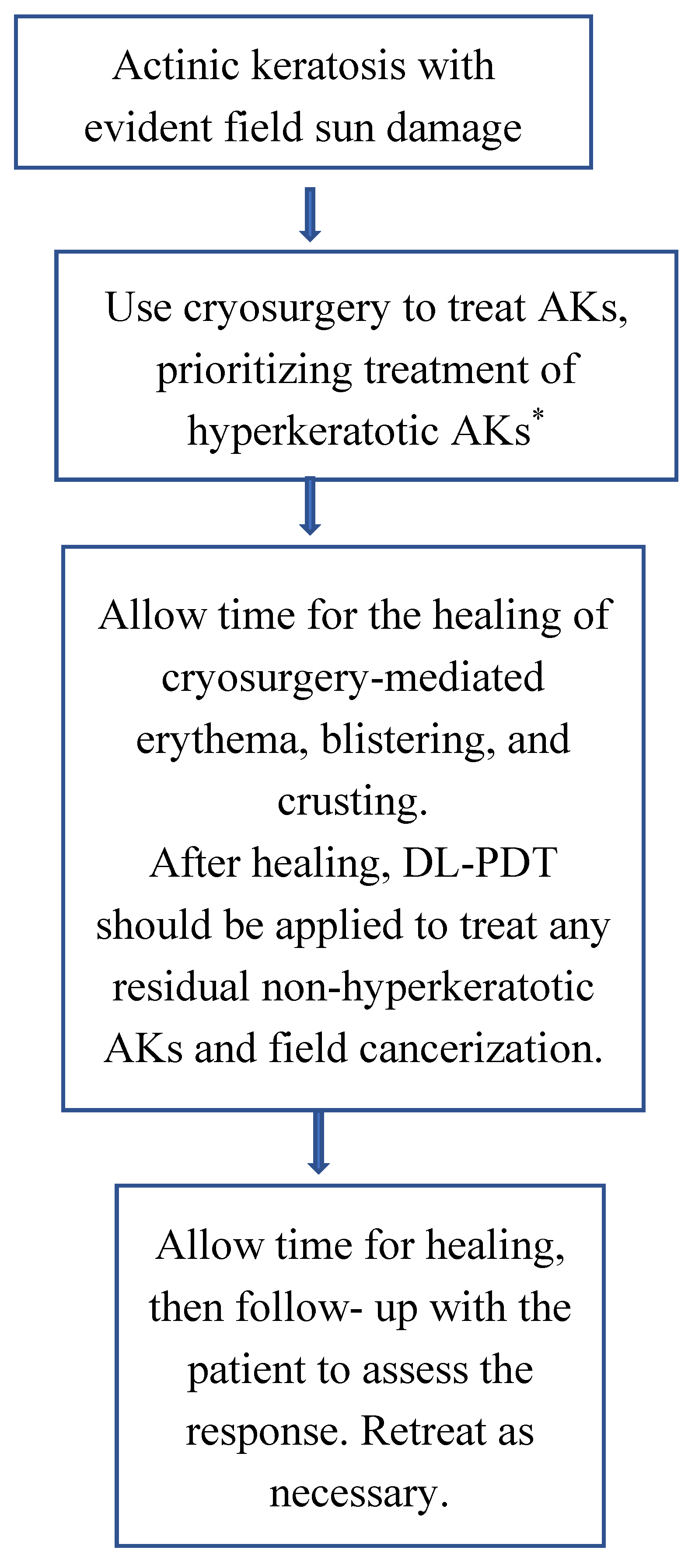

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Hædersdal M, Barber K, Basset-Seguin N, Del Pino Flores ME, Foley P, et al. Structured Expert Consensus on Actinic Keratosis: Treatment Algorithm Focusing on Daylight PDT. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017, 21, 3S–16S. [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu A-G, Grumezescu AM. Photodynamic Therapy—An Up-to-Date Review. Appl Sci [Internet]. 2021, 11. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/8/3626.

- Sotiriou E, Apalla Z, Vrani F, Lazaridou E, Vakirlis E, Lallas A, et al. Daylight photodynamic therapy vs. Conventional photodynamic therapy as skin cancer preventive treatment in patients with face and scalp cancerization: an intra-individual comparison study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017, 31, 1303–7. [Google Scholar]

- Morton CA, Wulf HC, Szeimies RM, Gilaberte Y, Basset-Seguin N, Sotiriou E, et al. Practical approach to the use of daylight photodynamic therapy with topical methyl aminolevulinate for actinic keratosis: a European consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015, 29, 1718–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar]

- Caccavale S, Boccellino MP, Brancaccio G, Alfano R, Argenziano G. Keratolytics can replace curettage in daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis on the face/scalp: A randomized clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024, 38, 594–601. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm V, Salmivuori M, Hahtola S, Mäkelä K, Pitkänen S, Isoherranen K. Ablative Fractional Laser Enhances Artificial or Natural Daylight Photodynamic Therapy of Actinic Field Cancerization: A Randomized and Investigator-initiated Half-side Comparative Study. Acta Derm Venereol 2023, 103, adv6579. [Google Scholar]

- Trave I, Salvi I, Serazzi FA, Schiavetti I, Luca L, Parodi A, et al. The impact of occlusive vs non-occlusive application of methyl aminolevulinate on the efficacy and tolerability of daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2024, 46, 104049. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Berg K, Moan J, Kongshaug M, Nesland JM. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy: principles and experimental research. Photochem Photobiol 1997, 65, 235–51. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, Zeitouni N, Lim HW, Jagdeo J. Photodynamic Therapy: Overview and Mechanism of Action. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet]. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Allison RR, Sibata CH. Photodynamic therapy: mechanism of action and role in the treatment of skin disease. G Ital Dermatol Venereol [Internet]. 2010, 145, 491–507, http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20823792. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski S, Knap B, Przystupski D, Saczko J, Kędzierska E, Knap-Czop K, et al. Photodynamic therapy – mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed Pharmacother [Internet]. 2018, 106, 1098–107, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0753332218341611. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelou G, Farrar MD, Cotterell L, Andrew S, Tosca AD, Watson REB, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy significantly reduces epidermal Langerhans cells during clinical treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol 2012, 166, 1112–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegell SR, Haedersdal M, Philipsen PA, Eriksen P, Enk CD, Wulf HC. Continuous activation of PpIX by daylight is as effective as and less painful than conventional photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses; a randomized, controlled, single-blinded study. Br J Dermatol 2008, 158, 740–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell J, Paterson C, Curnow A. Regression Analysis of Protoporphyrin IX Measurements Obtained During Dermatological Photodynamic Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz AJ, LaRochelle EPM, Gunn JR, Hull SM, Hasan T, Chapman MS, et al. Smartphone fluorescence imager for quantitative dosimetry of protoporphyrin-IX-based photodynamic therapy in skin. J Biomed Opt 2019, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Karrer S, Szeimies R-M, Philipp-Dormston WG, Gerber PA, Prager W, Datz E, et al. Repetitive Daylight Photodynamic Therapy versus Cryosurgery for Prevention of Actinic Keratoses in Photodamaged Facial Skin: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Multicentre Two-armed Study. Acta Derm Venereol 2021, 101, adv00355. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman G, Jacobsen K, Philipsen PA, Wiegell SR, Haedersdal M. Prebiotic and panthenol-containing dermocosmetic improves tolerance from daylight photodynamic therapy: A randomized controlled trial in patients with actinic keratosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2024, 104394.

- Lacour J-P, Ulrich C, Gilaberte Y, Von Felbert V, Basset-Seguin N, Dreno B, et al. Daylight photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate cream is effective and nearly painless in treating actinic keratoses: a randomised, investigator-blinded, controlled, phase III study throughout Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015, 29, 2342–8. [Google Scholar]

- Assikar S, Labrunie A, Kerob D, Couraud A, Bédane C. Daylight photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate cream is as effective as conventional photodynamic therapy with blue light in the treatment of actinic keratosis: a controlled randomized intra-individual study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, 1730–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fargnoli MC, Piccioni A, Neri L, Tambone S, Pellegrini C, Peris K. Conventional vs. daylight methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis of the face and scalp: an intra-patient, prospective, comparison study in Italy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015, 29, 1926–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fargnoli MC, Piccioni A, Neri L, Tambone S, Pellegrini C, Peris K. Long-term efficacy and safety of daylight photodynamic therapy with methyl amninolevulinate for actinic keratosis of the face and scalp. European journal of dermatology 2017, 27, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, Zhang L, Liu X, Hu C, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: A randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2018, 24, 366–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubel DM, Spelman L, Murrell DF, See J-A, Hewitt D, Foley P, et al. Daylight photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate cream as a convenient, similarly effective, nearly painless alternative to conventional photodynamic therapy in actinic keratosis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2014, 171, 1164–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz AJ, LaRochelle EPM, Fahrner M-CP, Emond JA, Samkoe KS, Pogue BW, et al. Equivalent efficacy of indoor daylight and lamp-based 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for treatment of actinic keratosis. Ski Heal Dis 2023, 3, e226. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriou E, Evangelou G, Papadavid E, Apalla Z, Vrani F, Vakirlis E, et al. Conventional vs. daylight photodynamic therapy for patients with actinic keratosis on face and scalp: 12-month follow-up results of a randomized, intra-individual comparative analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Togsverd-Bo K, Lei U, Erlendsson AM, Taudorf EH, Philipsen PA, Wulf HC, et al. Combination of ablative fractional laser and daylight-mediated photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis in organ transplant recipients - a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2015, 172, 467–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegell SR, Heydenreich J, Fabricius S, Wulf HC. Continuous ultra-low-intensity artificial daylight is not as effective as red LED light in photodynamic therapy of multiple actinic keratoses. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2011, 27, 280–5. [Google Scholar]

- Arisi M, Rossi MT, Spiazzi L, Guasco Pisani E, Venturuzzo A, Rovati C, et al. A randomized split-face clinical trial of conventional vs indoor-daylight photodynamic therapy for the treatment of multiple actinic keratosis of the face and scalp and photoaging. J Dermatolog Treat 2022, 33, 2250–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimberti, GN. Daylight Photodynamic Therapy Versus 5-Fluorouracil for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis: A Case Series. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2018, 8, 137–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegell SR, Fredman G, Andersen F, Bjerring P, Paasch U, Haedersdal M. Is the benefit of sequential 5-fluorouracil and daylight photodynamic therapy versus daylight photodynamic therapy alone sustained over time? - 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2025, 51, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen C V, Heerfordt IM, Wiegell SR, Mikkelsen CS, Wulf HC. Pretreatment with 5-Fluorouracil Cream Enhances the Efficacy of Daylight-mediated Photodynamic Therapy for Actinic Keratosis. Acta Derm Venereol 2017, 97, 617–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaserico S, Piccioni A, Gutiérrez Garcìa-Rodrigo C, Sacco G, Pellegrini C, Fargnoli MC. Sequential treatment with calcitriol and methyl aminolevulinate-daylight photodynamic therapy for patients with multiple actinic keratoses of the upper extremities. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2021, 34, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter N, Chandan N, Wang S, Tsoukas M. Field Cancerization Therapies for Management of Actinic Keratosis: A Narrative Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018, 19, 543–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh R, McCain S, Feldman SR. Refusal of Retreatment With Topical 5-Fluorouracil Among Patients With Actinic Keratosis: Qualitative Analysis. JMIR dermatology 2023, 6, e39988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich VK, Cull D, Kelly KA, Feldman SR. Patient assessment of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod for the treatment of actinic keratoses: a retrospective study of real-world effectiveness. J Dermatolog Treat 2022, 33, 2075–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale SM, Hill D, Feldman SR. Pharmacoeconomic Considerations in Treating Actinic Keratosis: An Update. Pharmacoeconomics 2017, 35, 177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, Connolly SM, Dellavalle RP, Freeman EE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis: Executive summary. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021, 85, 945–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtzi K, Papadimitriou I, Vakirlis E, Lallas A, Sotiriou E. Photodynamic Therapy for Field Cancerization in the Skin: Where Do We Stand? Dermatol Pract Concept 2023, 13.

- Steeb T, Wessely A, Schmitz L, Heppt F, Kirchberger MC, Berking C, et al. Interventions for Actinic Keratosis in Nonscalp and Nonface Localizations: Results from a Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2021, 141, 345–354.e8. [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of daylight photodynamic therapy for treatment of actinic keratoses in an Irish population. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet] 2016, 74, AB223. [CrossRef]

- Dirschka T, Ekanayake-Bohlig S, Dominicus R, Aschoff R, Herrera-Ceballos E, Botella-Estrada R, et al. A randomized, intraindividual, non-inferiority, Phase III study comparing daylight photodynamic therapy with BF-200 ALA gel and MAL cream for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019, 33, 288–97. [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, Ibbotson SH. Parameters associated with severe pain during photodynamic therapy: results of a large Scottish series. Br J Dermatol [Internet] 2011, 165, 696–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibbotson SH, Wong TH, Morton CA, Collier NJ, Haylett A, McKenna KE, et al. Adverse effects of topical photodynamic therapy: a consensus review and approach to management. Br J Dermatol 2019, 180, 715–29. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp-Dormston WG, Brückner M, Hoffmann M, Baé M, Fränken J, Großmann B, et al. Artificial daylight photodynamic therapy using methyl aminolevulinate in a real-world setting in Germany - Results from the non-interventional study ArtLight. Br J Dermatol. 2024.

- See J-A, Gebauer K, Wu JK, Manoharan S, Kerrouche N, Sullivan J. High Patient Satisfaction with Daylight-Activated Methyl Aminolevulinate Cream in the Treatment of Multiple Actinic Keratoses: Results of an Observational Study in Australia. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2017, 7, 525–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lang BM, Zielbauer S, Stege H, Grabbe S, Staubach P. If patients had a choice - Treatment satisfaction and patients’ preference in therapy of actinic keratoses. J der Dtsch Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = J Ger Soc Dermatology JDDG 2024, 22, 1362–8. [Google Scholar]

- Neittaanmäki-Perttu N, Grönroos M, Karppinen T, Snellman E, Rissanen P. Photodynamic Therapy for Actinic Keratoses: A Randomized Prospective Non-sponsored Cost-effectiveness Study of Daylight-mediated Treatment Compared with Light-emitting Diode Treatment. Acta Derm Venereol 2016, 96, 241–4. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment Type | Treatment Modality | Mechanism of Action | Application | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion-Directed Treatments | Cryotherapy | Induces cellular necrosis through rapid freezing of the lesion | Liquid nitrogen applied directly to lesion | Isolated, well-demarcated AK lesions |

| Surgical Excision | Complete excision of the lesion with scalpel or surgical instrument | Direct surgical removal of lesion | Thick, hypertrophic, or clinically suspicious AK | |

| Curettage and Electrodessication | Physical scraping followed by electrocautery to eliminate abnormal keratinocytes | Curette scraping followed by electrocautery | Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic AK lesions | |

| Ablative Laser Therapy | Utilizes ablative laser to vaporize and remove AK lesions | CO₂ or Er:YAG laser applied directly | Localized AK lesions or cosmetic concerns | |

| Field-Directed Treatments | 5-FU | Inhibits DNA synthesis and induces apoptosis in abnormal keratinocytes | Topical cream applied to affected areas | Multiple AK lesions or areas with field cancerization |

| Imiquimod | Modulates the immune system to enhance the immune-mediated clearance of AK lesions | Topical cream applied 2–3 times per week | Multiple AK lesions or field cancerization | |

| Diclofenac (NSAID Gel) | Inhibits COX-2, leading to apoptosis of AK cells | Topical gel applied twice daily | Mild to moderate AK lesions | |

| Tirbanibulin | Inhibits microtubule polymerization, inducing selective apoptosis of AK cells | Topical ointment applied once daily for 5 consecutive days | Mild AK lesions on the face and scalp | |

| cPDT | Photosensitization of keratinocytes through a photosensitizing agent, followed by light exposure to generate ROS. | Topical application of MAL or ALA followed by light activation | Multiple AK lesions and field cancerization | |

| dPDT | Utilizes natural sunlight to activate the photosensitizing agent, inducing apoptosis through ROS generation | Topical application of MAL or ALA followed by 1–2 hours of sun exposure | Extensive AK lesions or field cancerization with reduced pain |

| Aspect | Daylight PDT (dPDT) | Conventional PDT (cPDT) |

|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | Effective for non-hyperkeratotic AK and field cancerization. | Effective for non-hyperkeratotic AK and field cancerization. |

| Pain & Tolerability | Much less painful due to gradual activation of photosensitizer. | Often painful due to rapid activation with intense light. |

| Cosmetic Outcome | Excellent, with minimal inflammation and scarring. | Also good, but potential for more post-treatment erythema and irritation. |

| Convenience | No need for artificial light sources; can be done outdoors. | Requires a specialized light source and clinical setup. |

| Treatment Setting | Can be performed outside or indoors near windows. | Requires a clinical setting with trained personnel. |

| Weather Dependence | Dependent on sufficient daylight (not ideal for cloudy/rainy days). | Independent of weather conditions. |

| Cost & Equipment | More cost-effective (no expensive light source required). | Higher costs due to specialized light equipment and clinical visits. |

| Treatment Time | Longer exposure (2 hours outdoors), but shorter clinic time. | Shorter exposure (7–10 min per lesion) but longer clinic visits. |

| Patient Compliance | Easier for patients due to minimal pain and fewer clinic visits. | Compliance may be lower due to pain and frequent clinic visits. |

| Adverse Effects | Milder side effects (low pain, mild erythema, some scaling). | More erythema, swelling, crusting, and pain post-treatment. |

| Recurrences | Comparable efficacy in mild-to-moderate AK, good for field cancerization. | Potentially better for thicker AKs but with higher local inflammation. |

| Adverse Events | Description | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Pain, erythema, pruritus, crusting/scaling | Mild to moderate burning or itching, redness, scabbing | Common |

| Dyschromia, photosensitivity reaction[14,31,33,35,40,41,53,54,55,56] | Skin darkening or lightening, delayed sunburn-like reaction | Uncommon |

| Infection, erosion, ulceration, | Secondary bacterial infection, skin breakdown | Rare |

| Adverse Events | Description | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Pain, erythema, pruritus, crusting/scaling | Severe pain may occur in a significant proportion of patients, redness, scabbing | Common |

| Dyschromia, photosensitivity reaction | Skin darkening or lightening, delayed sunburn-like reaction | Uncommon |

| Infection, erosion, ulceration, edema | Secondary bacterial infection, skin breakdown, swelling | Rare |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).